Abstract

Background

A range of strategies are used to communicate with parents, caregivers and communities regarding child vaccination in order to inform decisions and improve vaccination uptake. These strategies include interventions in which information is aimed at larger groups in the community, for instance at public meetings, through radio or through leaflets. This is one of two reviews on communication interventions for childhood vaccination. The companion review focuses on face‐to‐face interventions for informing or educating parents.

Objectives

To assess the effects of interventions aimed at communities to inform and/or educate people about vaccination in children six years and younger.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, EMBASE and five other databases up to July 2012. We searched for grey literature in the Grey Literature Report and OpenGrey. We also contacted authors of included studies and experts in the field. There were no language, date or settings restrictions.

Selection criteria

Individual or cluster‐randomised and quasi‐randomised controlled trials, interrupted time series (ITS) and repeated measures studies, and controlled before‐and‐after (CBA) studies. We included interventions aimed at communities and intended to inform and/or educate about vaccination in children six years and younger, conducted in any setting. We defined interventions aimed at communities as those directed at a geographic area, and/or interventions directed to groups of people who share at least one common social or cultural characteristic. Primary outcomes were: knowledge among participants of vaccines or vaccine‐preventable diseases and of vaccine service delivery; child immunisation status; and unintended adverse effects. Secondary outcomes were: participants' attitudes towards vaccination; involvement in decision‐making regarding vaccination; confidence in the decision made; and resource use or cost of intervention.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently reviewed the references to identify studies for inclusion. We extracted data and assessed risk of bias in all included studies.

Main results

We included two cluster‐randomised trials that compared interventions aimed at communities to routine immunisation practices. In one study from India, families, teachers, children and village leaders were encouraged to attend information meetings where they received information about childhood vaccination and could ask questions. In the second study from Pakistan, people who were considered to be trusted in the community were invited to meetings to discuss vaccine coverage rates in their community and the costs and benefits of childhood vaccination. They were asked to develop local action plans and to share the information they had been given and continue the discussions in their communities.

The trials show low certainty evidence that interventions aimed at communities to inform and educate about childhood vaccination may improve knowledge of vaccines or vaccine‐preventable diseases among intervention participants (adjusted mean difference 0.121, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.055 to 0.189). These interventions probably increase the number of children who are vaccinated. The study from India showed that the intervention probably increased the number of children who received vaccinations (risk ratio (RR) 1.67, 95% CI 1.21 to 2.31; moderate certainty evidence). The study from Pakistan showed that there is probably an increase in the uptake of both measles (RR 1.63, 95% CI 1.03 to 2.58) and DPT (diptheria, pertussis and tetanus) (RR 2.17, 95% CI 1.43 to 3.29) vaccines (both moderate certainty evidence), but there may be little or no difference in the number of children who received polio vaccine (RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.97 to 1.05; low certainty evidence). There is also low certainty evidence that these interventions may change attitudes in favour of vaccination among parents with young children (adjusted mean difference 0.054, 95% CI 0.013 to 0.105), but they may make little or no difference to the involvement of mothers in decision‐making regarding childhood vaccination (adjusted mean difference 0.043, 95% CI ‐0.009 to 0.097).

The studies did not assess knowledge among participants of vaccine service delivery; participant confidence in the vaccination decision; intervention costs; or any unintended harms as a consequence of the intervention. We did not identify any studies that compared interventions aimed at communities to inform and/or educate with interventions directed to individual parents or caregivers, or studies that compared two interventions aimed at communities to inform and/or educate about childhood vaccination.

Authors' conclusions

This review provides limited evidence that interventions aimed at communities to inform and educate about early childhood vaccination may improve attitudes towards vaccination and probably increase vaccination uptake under some circumstances. However, some of these interventions may be resource intensive when implemented on a large scale and further rigorous evaluations are needed. These interventions may achieve most benefit when targeted to areas or groups that have low childhood vaccination rates.’

Keywords: Child; Child, Preschool; Humans; Infant; Health Knowledge, Attitudes, Practice; Health Education; Health Education/methods; India; Information Dissemination; Information Dissemination/methods; Pakistan; Parents; Parents/education; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Vaccination; Vaccination/statistics & numerical data

Plain language summary

Interventions aimed at communities for informing and/or educating about early childhood vaccination

Researchers in The Cochrane Collaboration conducted a review of the effect of informing or educating members of the community about early childhood vaccination. After searching for all relevant studies, they found two studies, published in 2007 and 2009. Their findings are summarised below.

What are interventions aimed at communities for childhood immunisation?

Childhood vaccinations can prevent illness and death, but many children do not get vaccinated. There are a number of reasons for this. One reason may be that families lack knowledge about the diseases that vaccines can prevent, how vaccinations work, or how, where or when to get their children vaccinated. People may also have concerns (or may be misinformed) about the benefits and harms of different vaccines.

Giving people information or education so that they can make informed decisions about their health is an important part of all health systems. Vaccine information and education aims to increase people's knowledge of and change their attitudes to vaccines and the diseases that these vaccines can prevent. Vaccine information or education is often given face‐to‐face to individual parents, for instance during home visits or at the clinic. Another Cochrane Review assessed the impact of this sort of information. But this information can also be given to larger groups in the community, for instance at public meetings and women's clubs, through television or radio programmes, or through posters and leaflets. In this review, we have looked at information or education that targeted whole communities rather than individual parents or caregivers.

The review found two studies. The first study took place in India. Here, families, teachers, children and village leaders were encouraged to attend information meetings where they were given information about childhood vaccination and could ask questions. Posters and leaflets were also distributed in the community. The second study was from Pakistan. Here, people who were considered to be trusted in the community were invited to meetings where they discussed the current rates of vaccine coverage in their community and the costs and benefits of childhood vaccination. They were also asked to develop local action plans, to share the information they had been given and continue the discussions with households in their communities.

What happens when members of the community are informed or educated about vaccines?

The studies showed that community‐based information or education:

‐ may improve knowledge of vaccines or vaccine‐preventable diseases;

‐ probably increases the number of children who get vaccinated (both the study in India and the study in Pakistan showed that there is probably an increase in the number of vaccinated children);

‐ may make little or no difference to the involvement of mothers in decision‐making about vaccination;

‐ may change attitudes in favour of vaccination among parents with young children;

We assessed all of this evidence to be of low or moderate certainty.

The studies did not assess whether this type of information or education led to better knowledge among participants about vaccine service delivery or increased their confidence in the decision made. Nor did the studies assess how much this information and education cost or whether it led to any unintended harms.

Summary of findings

for the main comparison.

| Interventions aimed at communities to inform and/or educate about early childhood vaccination versus routine immunisation practices in primary and community care | ||||||

|

People: community members Settings: primary and community care Intervention: interventions to inform and/or educate members of the community about early childhood vaccination Comparison: routine immunisation practices | ||||||

| Outcomes | Impact | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE)† | |||

| Absolute effect* | Estimated effects | Results in words | ||||

|

Without interventions aimed at communities |

With interventions aimed at communities |

|||||

| Knowledge among participants of vaccine or vaccine‐preventable disease (number of people whose vaccine knowledge had increased; follow‐up: mean = 2 years; assessed through household survey using a questionnaire) | 59 per 100 people | 71 per 100 people (from 65 to 78) | Adjusted mean difference 0.121 (95% CI 0.06 to 0.19) | The intervention may improve knowledge of vaccine‐preventable diseases among intervention participants | 55821 | ⊕⊕⊖⊖ Low2 |

| Knowledge among participants of vaccine service delivery | The included studies did not assess this outcome | |||||

| Immunisation status of child (follow‐up: mean = 2 years; assessed through household survey using a questionnaire) | Pooling of the data from these studies was not possible |

|

One study showed that the intervention probably increases the number of children who received one or more vaccinations. A second study showed that the intervention probably increases the uptake of both measles and DPT vaccines but makes little or no difference to the number of children who received polio vaccine |

3 |

⊕⊕⊕⊖ Moderate4 | |

| Participants' attitudes towards vaccination (number of parents who think it is worthwhile to vaccinate children; follow‐up: mean = 2 years; assessed through household survey using a questionnaire) | 86 per 100 parents | 91 per 100 parents (from 87 to 96) | Adjusted mean difference 0.054 (95% CI 0.01 to 0.11) | The intervention may improve attitudes towards vaccination among intervention participants | 56361 | ⊕⊕⊖⊖ Low5 |

| Participants' involvement in decision‐making regarding vaccination (number of mothers included in decisions about vaccination; follow‐up: mean = 2 years; assessed through household survey using a questionnaire) | 55 per 100 mothers | 60 per 100 mothers (from 54 to 65) | Adjusted mean difference 0.043 (95% CI ‐0.01 to 0.1) | The intervention may make little or no difference to the involvement of mothers in decision‐making regarding vaccination | 55651 | ⊕⊕⊖⊖ Low6 |

| Participant confidence in the decision made regarding vaccination | The included studies did not assess this outcome | |||||

| Unintended or adverse effects | The included studies did not assess this outcome | |||||

| Resource use or cost of the intervention | The included studies did not assess this outcome | |||||

| *The absolute effect WITHOUT the intervention is based on data from the trial control group. The corresponding absolute effect WITH the intervention is based on the estimated effect of the intervention relative to the control group. CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; DPT: diphtheria, pertussis and tetanus vaccine | ||||||

|

†GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: This research provides a very good indication of the likely effect. The likelihood that the effect will be substantially different^ is low. Moderate certainty: This research provides a good indication of the likely effect. The likelihood that the effect will be substantially different^ is moderate. Low certainty: This research provides some indication of the likely effect. However, the likelihood that it will be substantially different^ is high. Very low certainty: This research does not provide a reliable indication of the likely effect. The likelihood that the effect will be substantially different^ is very high. ^Substantially different = a large enough difference that it might affect a decision | ||||||

1Andersson 2009. 2Downgraded due to risk of bias, as the outcome is based on self report; indirectness as the outcome assessed in the trial is not identical to that specified in the review; and sparse data drawn from a single study. 3Andersson 2009 (study 2), Pandey 2007 (study 1 ‐ unpublished data). 4Downgraded due to some imprecision (wide confidence intervals that include both little effect and a substantial effect) and some inconsistency across the findings from the two studies. 5Downgraded due to risk of bias, as the outcome is based on self report; indirectness as the outcome assessed in the trial is not identical to that specified in the review; and sparse data drawn from a single study. 6Downgraded due to risk of bias, as the outcome is based on self report; indirectness as the outcome assessed in the trial is not identical to that specified in the review; and sparse data drawn from a single study.

Background

This Cochrane Review was undertaken as part of a two‐year, multi‐stage research project called 'Communicate to Vaccinate 1' (COMMVAC 1) (Lewin 2011). The COMMVAC project focuses on building research knowledge and capacity to use evidence‐based strategies for improving communication about childhood vaccinations with parents and communities in low‐ and middle‐income countries (LMICs). This review is one of two reviews focusing on communication interventions to inform and/or educate about childhood vaccination. A series of deliberative forums identified the topics of both reviews as highly relevant to vaccine programme managers, policy‐makers and other key stakeholders in LMICs. The companion review focuses on face‐to‐face interventions for informing or educating parents (Kaufman 2013), while this review excludes interventions that target only individual parents or caregivers and focuses on interventions aimed at communities. The two reviews were developed in close collaboration, and our review uses some of the same text as Kaufman 2013 in the Background and Methods sections, with their permission.

Description of the condition

Vaccination has been described as one of the greatest public health achievements of the 20th century (CDC 1999), and is seen widely as a worthwhile and cost‐effective public health measure. Vaccination programmes have led to the global eradication of smallpox, and large reductions in disability and death from polio, measles, tetanus, rubella, diphtheria and Haemophilus influenzae type b (CDC 1999). However, over 24 million children are still without access to this important health intervention (Jheeta 2008; Wiysonge 2009), contributing to millions of preventable child deaths in LMICs (GAVI 2012). Efforts to improve vaccination coverage in LMICs are central to meeting the Millennium Development Goal (MDG) of reducing child mortality (United Nations 2011).

Routine vaccination is also an important issue in high‐income countries (HICs), many of which experience equity‐related challenges to achieving high vaccination coverage rates. A number of socio‐economic factors can affect coverage, including indigenous or ethnic status, poverty, large family size and low educational attainment. Consequently, certain population groups in HICs may have coverage rates below the national average, in some cases as low as those in some LMICs (Thomson 2012). For example, in Australia the 'fully immunised' vaccination coverage estimate in 2009 for Indigenous children aged 12 months was 85%, compared to 92.2% for non‐Indigenous children. However, this disparity was greatly reduced at 24 months, with 90.6% and 92.2% fully vaccinated for Indigenous and non‐Indigenous children respectively (Hull 2011). In the USA, there are still disparities in coverage rates based on socio‐economic status (Wooten 2010). A study from Austria has also shown that low educational attainment and high numbers of children in one family are associated with lower levels of vaccination coverage (Stronegger 2010).

Another cause of regional vaccination coverage variation in HICs is individuals who refuse some or all vaccination of their children. Vaccination objectors are probably more common in HICs and also tend to be grouped in particular regions. While they constitute a small proportion of the country's population overall, they may significantly lower coverage in certain areas (Diekema 2012; Hull 2010).

The term 'vaccine hesitancy' has been used in recent years to help understand behaviour in relation to vaccination. The WHO has defined vaccine hesitancy as "A behaviour, influenced by a number of factors including issues of confidence (do not trust vaccine or provider), complacency (do not perceive a need for a vaccine, do not value the vaccine), and convenience (access). Vaccine‐hesitant individuals are a heterogeneous group who hold varying degrees of indecision about specific vaccines or vaccination in general. Vaccine‐hesitant individuals may accept all vaccines but remain concerned about vaccines, some may refuse or delay some vaccines, but accept others; some individuals may refuse all vaccines" (WHO 2013). Determinants of vaccine hesitancy have been conceptualised as falling into three domains: contextual influences, including socio‐cultural and health systems factors; individual and group influences, including those rising from personal perceptions of a vaccine; and vaccine or vaccination‐specific issues, including individual assessments of risks and benefits and the effects of the mode of administration (WHO 2013).

Large numbers of qualitative and quantitative studies, as well as some reviews, have explored the reasons for vaccine hesitancy and the non‐vaccination of children (Dubé 2013; Larson 2014). Overall, the reviews highlight that vaccination decision‐making is a complex process, influenced by many factors. An important barrier in many settings is not being appropriately informed and, consequently, being in doubt about the trade‐offs between the benefits and harms of vaccination and having fears about side effects (Casiday 2006; Hadjikoumi 2006; Mills 2005; Pearce 2008; Taylor 2002). People may lack knowledge about how vaccinations and the process of immunisation 'works', but also about the diseases which vaccines may help prevent (Casiday 2006; Mills 2005; Woo 2004).

A key barrier to obtaining and using information on vaccination is people's poor understanding of medical and health‐related scientific concepts that are important for decision‐making, such as risk, uncertainty and causality (Casiday 2006; Tickner 2006; Woo 2004). Furthermore, people may not base their decision on evidence‐based information (Paulussen 2006; Tickner 2006). Studies have found that decision‐making about childhood vaccinations is often based on trust and personal experiences (Tickner 2006). For both vaccinators and non‐vaccinators, the decision is based on the intention to minimise the child's exposure to harm (Paulussen 2006; Tickner 2006). However, what people trust and who they trust have been found to differ somewhat between those deciding to vaccinate and those who decline. Vaccinators are generally more positive with regard to conventional sources of information, such as national health institutions and health personnel, while non‐vaccinators have been found to rely more on alternative sources of health information (Casiday 2006; Pearce 2008). The recent attacks on vaccination teams in Pakistan, with almost 30 vaccinators killed in the last two years, illustrate the extent to which suspicions about vaccination, linked to misinformation about the purpose and effects of vaccination, may have significant impacts on both vaccination programme staff and the communities in which they work (Boone 2014).

The perceived dangers of vaccination and the likelihood of vaccine side effects are also important influences on whether parents will allow their children to be vaccinated. Studies have shown that caregivers who do not vaccinate have very different views about the likelihood of a serious side effect than caregivers who take their children for vaccination (Meszaros 1996). Fear associated with vaccination has also been attributed to mass media reports about serious harms associated with vaccination (Woo 2004). Further, evidence suggests that there is more public controversy associated with new vaccines than with the more established vaccines, often based on a perception that new vaccines have not been tested adequately (Tickner 2006). A recent example of such a controversy is the debate about vaccination against swine flu (H1N1 influenza virus) (Teasdale 2011).

The extent to which socio‐demographic variables predict vaccination uptake varies somewhat across study populations. However, studies exploring uptake of, for example, the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine have suggested that the number of children in a family, being a single parent and the mother's age may be related to vaccination status (Casiday 2006; Pearce 2008; Wright 2006). Vaccination coverage has also been found to be less optimal in areas with high population density and deprived populations (Wright 2006). Also, populations with higher education levels have been found to have a more rapid decline in coverage (Wright 2006) and to be more sceptical towards vaccination than populations with lower education levels. However, this may be explained by a differential response to health messages across these groups (Pearce 2008).

Other barriers to vaccination uptake include religious or philosophical beliefs (Mills 2005; Taylor 2002); practical issues such as costs, accessibility, forgetting appointments, lack of time and other commitments (Mills 2005; Tickner 2006); or medical issues including having allergies or an illness (Hadjikoumi 2006; Pearce 2008). Studies also indicate that communication between parents and health professionals may not be optimal as a consequence of time constraints during consultations; health professionals delivering information framed as recommendations instead of in ways that would facilitate a decision based on weighing the benefits and risks; and parents perceiving health professionals as biased or unwilling to discuss their concerns (Hobson‐West 2007; Mills 2005; Tickner 2006).

Description of the intervention

The exchange or delivery of information or education is a feature in all contexts of the health system, as people must decide whether or not to participate in health programmes or take particular actions. Such decisions are based on the information and knowledge that people have or acquire (Zyngier 2011). Successful vaccination programmes rely on people having sufficient knowledge to make an informed decision to participate (Shahrabani 2009).

Information provision and education may be undertaken in various ways. This review will focus on interventions aimed at communities to inform or educate about vaccination in children aged six years and younger. The interventions may include: printed materials such as brochures, pamphlets, posters or fact sheets; electronic media such as videos, slide shows, web‐based programmes or audio recordings; and large‐scale media such as billboards, newspaper, television and radio.

Information versus education

We have chosen to examine interventions whose purpose is to inform as well as those whose purpose is to educate. Most texts use the words 'inform' or 'educate' in tandem or interchangeably, and there is no consistent differentiation between these purposes. Kaufman 2012 conducted a content analysis to see how these terms were used, described and defined in practice. They found some consistencies in the ways that agencies and publications describe interventions to 'inform and educate'. Interventions to inform often: are utilised for the provision and dissemination of up‐to‐date, tailored and accurate information; involve limited interaction, as they are mainly targeted to many people at one time; and are recognised as being insufficient to lead to behaviour change (Hollands 2011). Interventions to educate were found to involve verbal communication and some level of interaction; can be supplemented with educational tools, educational materials and written information; and facilitate learning and greater comprehension.

In this review, we looked at interventions to inform and/or educate without distinguishing between them (see below for a definition of these interventions). The goal of these interventions is to achieve outcomes such as knowledge of vaccines, vaccine‐preventable diseases or service delivery; increased involvement in decision‐making; better informed decisions and more confidence in the decision made regarding vaccination; and improved vaccination coverage. Interventions to inform or educate may be tailored to address low literacy levels and can also serve to address misinformation. To better understand the content of these interventions, we recorded all information related to the nature of the intervention for each included study at the data extraction stage.

Delivery mechanisms

Interventions to inform and/or educate that are aimed at communities or groups of community members may be a cost‐effective method of reaching many people. The interventions can be delivered by a range of mechanisms, including face‐to‐face interactions (e.g. vaccination education sessions held at an immunisation carnival; vaccine information disseminated at public meetings or woman's clubs), mass‐media campaigns (e.g. vaccine information disseminated via television, radio, Internet, newspapers, billboards) or mail (e.g. postcards, letter or emails). The audience or target group for these interventions may include all people living in the communities in which the intervention takes place; groups with particular characteristics (e.g. young mothers); or virtual communities (e.g. online parents' forums).

Examples of interventions to inform and/or educate communities or community members about childhood vaccination include:

USA: a media‐based education and outreach campaign to improve knowledge and awareness of hepatitis B and children's receipt of hepatitis B vaccination (McPhee 2003a);

India: an information campaign focusing on services to which people were entitled, and consisting of meetings and the distribution of posters and leaflets directed towards resource‐poor rural populations; vaccinations received by infants was one of the outcomes assessed (Pandey 2007); and

Pakistan: evidence‐based, structured, group discussions in the community on the prevalence of measles among children and the importance of childhood immunisation (Andersson 2009).

This review aimed to assemble the global evidence on interventions to inform and/or educate communities or community members about childhood vaccination. We were interested in whether the effects of these interventions varied by type of delivery mechanism, and planned subgroup analyses to explore this (see Appendix 1).

How the intervention might work

The interventions aim to increase participants' levels of knowledge and/or change their attitudes regarding vaccination. Changes in knowledge and/or attitudes can be regarded as intermediate outcomes, and may lead to at least two more distal outcomes:

a change in the number of participants who make informed decisions regarding childhood vaccination (which may include the decision not to vaccinate); and

a change in childhood vaccination rates.

It is important to note that the pathway from improved knowledge and information to changes in attitudes towards vaccination and, finally, to improved uptake of vaccination is not necessarily linear or simple. Increased knowledge may, for example, result in more informed decision‐making among caregivers, but not in increased childhood vaccination uptake.

As noted above, interventions aimed at communities may be a cost‐effective method of reaching many people. In addition, the sharing and discussion of information within groups, such as women's groups, may enhance the uptake of this information, raise awareness of childhood vaccination issues and facilitate informed decision‐making regarding vaccination.

Why it is important to do this review

The COMMVAC project held a series of deliberative forums (both face‐to‐face and online) in June and July 2011 to discuss the project's taxonomy of communication interventions and to determine priority topics for systematic reviews of effects. Those invited to participate included vaccination programme managers, policy‐makers, researchers and other vaccination stakeholders. The forums included representatives from HICs and LMICs, but focused on the needs of LMICs in particular. The participants identified interventions aimed at communities or community members as a strategy that is used widely and is highly relevant (Willis 2013). However, the implementation of these interventions requires resources including money, time and trained personnel (UNICEF 2000). It is therefore critical to determine whether interventions aimed at communities to inform and/or educate are effective, so as to inform decisions about the use of resources on these strategies.

Overlap with other reviews

Our review is closely related to two other reviews: 'Interventions for improving coverage of child immunisation in low‐ and middle‐income countries' by Angela Oyo‐Ita and colleagues (Oyo‐Ita 2011) and 'Face‐to‐face interventions for informing or educating parents about early childhood vaccination' by Jessica Kaufman and colleagues (Kaufman 2013). It also has some overlap with other reviews. Table 2 describes the differences between our review and these other reviews. This review and the Kaufman review ('the COMMVAC reviews') consider specific sets of 'communicate to vaccinate' interventions, but with a global rather than a LMIC focus. We know from the COMMVAC mapping process that a significant proportion of these communication interventions have not been evaluated in LMICs. Although there is some overlap between Oyo‐Ita 2011 and the COMMVAC reviews, these global reviews will provide a more complete picture of the effects of these specific communication interventions (while the Oyo‐Ita review considers all interventions to increase vaccination coverage, but is restricted to studies conducted in LMICs). The review author teams for these three reviews were in close contact and addressed any overlap by:

1. Comparison between this review and other reviews on related topics.

| Review citation | Focus of cited review | Comparison with our review |

| Briss 2000 | This review considers the effects of population‐based interventions to improve vaccination coverage in children, adolescents and adults | Briss 2000 only includes studies from industrialised settings and studies published up to 1997, although it includes a wider scope of interventions than our review. Our review includes studies conducted in any setting and focusing on children, and updates findings from the Briss review for this range of interventions |

| Grilli 2002 | This review assesses the effect of mass media intervention on the utilisation of health services. 20 studies were included in the review; 2 were relevant to vaccination | Our review only includes mass media interventions focused on vaccination and not those focusing on other health services or issues Grilli 2002 has not been updated since 2001 |

| Stone 2002 | This review assesses the effects of interventions to increase the use of adult immunisation | Our review focuses on immunisation in children only |

| Maglione 2002 | This reviews assesses the effects of mass mailings designed to increase utilisation of influenza vaccine among Medicare beneficiaries in the USA | Our review focuses on immunisation in children only |

| Jacobson 2005 | This review assesses the effectiveness of patient reminder and recall systems to improve immunisation rates, and compares the effects of various types of reminders in different settings or patient populations | Our review excludes reminder and recall systems where there is no information and/or education component or purpose |

| Lewin 2010 | This review assesses the effects of lay health worker interventions on maternal and child health and the management of infectious diseases. 82 trials are included in the review; 8 are potentially relevant to vaccination. 7 of these deal with childhood vaccination | Our review is not limited to interventions delivered by lay health workers. Any childhood immunisation interventions included in the Lewin 2010 review and that were also aimed at communities were considered for inclusion in this review |

| Glenton 2011 | This review assesses the effects of lay health worker interventions on the uptake of childhood immunisation and develops a typology of intervention models | Our review is not limited to lay health worker interventions |

| Oyo‐Ita 2011 | This review evaluates the effectiveness of strategies to increase childhood vaccination rates in low‐ and middle‐income countries. 6 studies are included in the review. 4 involve some form of communication with parents or communities | This review only includes studies conducted in low‐ and middle‐income countries. Our review includes studies conducted in any location |

|

Williams 2011 |

This review assesses the effectiveness of strategies to improve childhood immunisation uptake in primary care settings in developed countries. Strategies may be directed to consumers or practitioners and include remind or recall interventions, education, parent‐held records and feedback | The studies included in this review were conducted in high‐income countries only and in primary care settings, while the scope of our review includes all locations and settings |

| Cairns 2012 | This review examined evidence on the effectiveness of European promotional communications for national immunisation schedule vaccinations. The review aimed to: describe the types of promotional communication that have been used; assess the quality of the evaluations these promotional communication interventions; and assess the applicability of this evidence to immunisation policy, strategy and practice priorities in Europe | Cairns 2012 considered immunisation in adults, adolescents and children and included studies conducted in a European country and evaluating a promotional communication intervention. Our review focuses on community‐directed interventions to inform or educate about childhood vaccination only and also includes studies from any setting. None of the studies in Cairns 2012 that focused on childhood vaccination and evaluated interventions aimed at communities were eligible for inclusion in our review |

| Kaufman 2013 | A companion COMMVAC review focused on face‐to‐face interventions directed at parents | Our review includes interventions which target community members (the general public), including, for example, parents and other caregivers and family members of young children, community leaders, teachers, health personnel (as part of a wider community intervention), and other influential community members We excluded interventions that targeted individuals directly and were not aimed at communities ‐ these interventions are considered in the Kaufman review |

| Sadaf 2013 | This review assessed the evidence on interventions to decrease parental vaccine refusal and hesitancy toward recommended childhood and adolescent vaccines | Sadaf 2013 includes a wider scope of interventions and study designs than our review and also included interventions focused on adolescents and young adults. The review does not specifically address the effects of interventions aimed at communities and does not include any studies that were eligible for inclusion in our review |

| Dubé 2013 | This review considers the possible causes of vaccine hesitancy in low‐ and middle‐income countries and the determinants of individual decision‐making about vaccination | This review did not focus on the effects of interventions to inform or educate about early childhood vaccination |

| Larson 2014 | This review aimed to: 1) identify research on vaccine hesitancy; 2) identify determinants of vaccine hesitancy in different settings; and 3) inform the development of a model for assessing determinants of vaccine hesitancy in different settings | This review did not focus on the effects of interventions to inform or educate about early childhood vaccination |

outlining clearly in each review the scope of the related reviews;

discussing studies identified from LMIC and HIC settings, and any differences and similarities between these;

discussing the effects of communication interventions in relation to other interventions to improve immunisation coverage, as identified in Oyo‐Ita 2011.

Objectives

To assess the effects of interventions aimed at communities to inform and/or educate people about vaccination in children six years and younger.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Interventions to 'inform and educate' that aim to reach communities, or groups of community members, are likely to have been evaluated using a wide variety of approaches and designs. For some of these interventions, for example those delivered through mass media such as newspapers or radio, randomisation may not be feasible and other evaluation designs may be needed.

We therefore included the following types of studies.

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs), with randomisation at either individual or cluster level. For cluster‐RCTs, we only included those with at least two intervention and two control clusters.

Quasi‐randomised controlled trials, with allocation at either individual or cluster level. We included studies that allocated by alternation between groups, by the use of birth dates or weekdays or by other quasi‐random methods. For cluster trials, we only included those with at least two intervention and two control clusters.

Interrupted time series (ITS) and repeated measures studies with a clearly defined point in time when the intervention occurred and at least three data points both before and after the intervention.

Controlled before‐and‐after (CBA) studies with a minimum of two intervention and two control sites; comparable timing of the periods of study for the control and intervention groups; and comparability of the intervention and control groups on key characteristics.

Types of participants

We included interventions which targeted groups of people (the general public), including, for example, parents and other caregivers and family members of young children, community leaders, teachers, health personnel (as part of a wider community intervention) and other influential community members. Some of these groups are the 'end' target group for vaccination communication interventions (such as parents and other caregivers) while other groups are 'intermediaries' who are targeted because of their ability to convey information to or educate the end target group. Such intermediaries include community leaders, teachers and other influential community members, such as religious leaders.

We excluded interventions that targeted individuals directly and were not aimed at communities. Hence we excluded studies in which the interventions targeted individual parents or caregivers directly, except where these individuals functioned as the control group for an eligible intervention.

Some studies examined interventions aimed at a group (such as mothers of children attending a paediatric clinic) that comprised individual people attending a health facility for a health issue related to the intervention (i.e. they had no pre‐existing group relationship to one another, and were selected to participate as individuals). In such cases, we excluded the study if the group was constituted for the purposes of the trial, but included it if the group constituted a social or natural group prior to the trial.

Types of interventions

We included interventions aimed at communities, with a broad audience and purpose (see definition below) and that were intended to inform and/or educate about vaccination in children six years and younger. We defined 'inform and/or educate' interventions as those that enabled consumers to understand the meaning and relevance of vaccination to their health and the health of their family or community, and/or made them aware of the practical and logistical factors associated with vaccination. Interventions to inform and/or educate may be tailored to address issues such as low literacy levels or misinformation.

We defined interventions aimed at communities as those directed at a geographic area and/or interventions directed to groups of people who share at least one common social or cultural characteristic. This definition of interventions aimed at communities is based on definitions developed for other reviews, including Baker 2011. These interventions can be delivered by a broad range of people such as health personnel, lay people, governmental institutions, civil society organisations and other non‐governmental organisations. Delivery mechanisms may include: printed materials such as brochures, pamphlets, posters or fact sheets; electronic media such as videos, slide shows, web‐based programmes, virtual online communities or audio recordings; large‐scale media such as billboards, newspaper, television and radio; and face‐to‐face communication with groups of people.

Participants' involvement in these interventions may vary from passive to active. For example, people may be fairly passive recipients of mass media interventions, such as information provided on billboards, or more active participants in community meetings on child health.

We included interventions that aimed to inform and/or educate about vaccination in children six years and younger as well as in older children or others, provided that the main focus of the intervention was on children six years and younger, or that relevant outcomes for children aged six years and younger were reported separately.

We included multi‐faceted interventions if it was possible to separate out the effects of the communication component aimed at communities and that concerned childhood vaccination, i.e. the results for the interventions aimed at communities to inform and/or educate regarding vaccination needed to be reported separately.

We excluded interventions focused on reminding or recalling recipients regarding vaccination if they did not include an information and/or education component or purpose.

We included relevant studies conducted in any setting (including LMICs and HICs).

Comparisons:

-

Interventions aimed at communities to inform and/or educate versus:

routine immunisation practices in the study setting (i.e. the activities undertaken on a day‐to‐day basis in the study setting to promote immunisation uptake and deliver immunisation services, such as sending reminders to caregivers or writing the next immunisation date on the child's health card);

other interventions to promote immunisation uptake; or

no intervention.

Interventions aimed at communities to inform and/or educate versus interventions directed specifically to individual parents or caregivers of children.

One community‐aimed intervention to inform and/or educate versus another community‐aimed intervention to inform and/or educate.

Types of outcome measures

We only included studies if they assessed any of the following primary or secondary outcomes:

Primary outcomes

Knowledge among participants of vaccines or vaccine‐preventable diseases.

Knowledge among participants of vaccine service delivery.

Immunisation status of child (e.g. immunisation status up‐to‐date as defined by the author of the included study: receipt of one or more vaccines).

Any other measures of vaccination status in children (e.g. immunisation status for a specific vaccine, number of vaccine doses received).

Unintended adverse effects due to the intervention.

Immunisation status may be defined slightly differently across studies (e.g. receipt of a single or multiple vaccines; timeliness of vaccination). We have accepted the definition of immunisation status used by study authors.

Secondary outcomes

Participants' attitudes towards vaccination (the term 'attitudes' covers beliefs about vaccination, and may include intention to vaccinate).

Participant involvement in decision‐making regarding vaccination.

Participant confidence in the decision made regarding vaccination.

Resource use or cost of intervention.

We included the first three of the secondary outcomes listed above in this review as they relate to the pathway from improved knowledge and information to changes in attitudes towards vaccination and, finally, to improved uptake of vaccination (see Background).

The occurrence of vaccine‐preventable diseases is an outcome of immunisation, rather than of an intervention to inform and/or educate, and is affected by many other factors. We therefore have not reported this outcome.

To accommodate multiple or varying outcome assessment time points, we have recorded outcomes in the following categories:

Immediate: up to one month following completion of the intervention.

Short‐term: between one and six months following the completion of the intervention.

Long‐term: more than six months following the completion of the intervention.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following international and regional sources:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (11 July 2012);

MEDLINE (OvidSP) MEDLINE In‐Process & Other Non‐Index Citations (OvidSP) (1946 to June 2012);

EMBASE (OvidSP) (1947 to July 2012);

CINAHL (EbscoHOST) (date of search: 19 July 2012);

PsycINFO (OvidSP) (1806 to July 2012);

ERIC (ProQuest) (1966 to July 2012);

Global Health (CAB) (1910 to June 2012);

WHO Global Health Library (including WHOLIS, LILACS and other regional databases) (date of search: 26 July 2012).

We also searched the following grey literature databases:

The Grey Literature Report: http://www.nyam.org/library/online‐resources/grey‐literature‐report/;

OpenGrey: http://www.opengrey.eu/.

All the strategies are presented in Appendix 2. Strategies have been tailored to the other databases and are reported in the Appendix. There were no date restrictions in the searches.

We conducted the searches in English. We assessed titles and abstracts published in any language, and obtained translation of potentially eligible studies where needed.

Searching other resources

We contacted the authors of included studies and the members of the COMMVAC project (www.commvac.com) advisory group for additional references.

Data collection and analysis

The data collection and analysis methods were described in the review protocol (Saeterdal 2012). We used Reference Manager software version 12 to store the records retrieved from the search (Reference Manager 12). We then used the Early Review Organizing Software version 2.0 to manage the records retrieved from the search following initial eligibility assessment and to facilitate full‐text screening of papers (EROS 2012).

Selection of studies

The review authors worked in pairs to independently screen all titles and abstracts identified in the search, and assess eligibility based on the Criteria for considering studies for this review. We retrieved all potentially eligible references in full text and the review authors then worked in pairs and independently assessed these references for inclusion against the Criteria for considering studies for this review. We resolved any disagreements through discussion and consulted one of the other review authors when required.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors working in pairs extracted data independently from all included studies. Data extraction was informed by lessons learned in the earlier evidence mapping stages of the COMMVAC project (Willis 2013). We used a data extraction form that combined features of the template developed by the Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group (CC & CRG 2011), the Cochrane equity checklist (Ueffing 2011), and the COMMVAC data extraction template. The form included questions to capture the following data:

Identification details of the study: authors, year of publication, the country and setting in which it was conducted, language and study design.

Participant characteristics: type of participant (type of community member), numbers, gender, age, ethnicity, religion, socio‐economic status, level of education, etc. We also recorded type and characteristics of the community (geographic area, social or cultural characteristics, local vaccination policy).

Intervention characteristics: type of intervention, intervention purpose, content of communication, intervention delivery mechanism. We also recorded information about the vaccine that was the focus of the intervention. We recorded similar characteristics for the comparator.

Outcomes: outcome data (results), methods for assessing/measuring the outcome data, length of follow‐up, loss to follow‐up data. We noted additional outcomes in the data extraction template.

One of the authors (IS) entered the data into the Review Manager software (RevMan 2012) and second author (AAD or SMB) then checked the data. We resolved disagreements regarding the data extracted by discussion and, when necessary, by consulting a third review author (CG or SL).

For studies published only as abstracts, we planned to contact the study authors for further information and to list these studies under 'Studies awaiting classification' until further information was obtained. For study reports that contained little information about methods and results, we contacted the authors to obtain further details on these elements.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed and reported on the methodological risk of bias of included studies in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), and the guidelines of the Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group (Ryan 2011), which recommends the explicit reporting of the following individual elements for RCTs: random sequence generation; allocation sequence concealment; blinding (participants, personnel); blinding (outcome assessment); completeness of outcome data; selective outcome reporting; and any other sources of bias such as contamination. For each domain we have described the relevant information provided by the authors and judged each item as being at high, low or unclear risk of bias as set out in the criteria provided by Higgins 2011.

For cluster‐RCTs we also assessed the risk of bias associated with an additional domain: selective recruitment of participants (Ryan 2011). Two authors assessed the risk of bias of included studies independently. We resolved disagreements between review authors regarding 'Risk of bias' assessment by discussion and, when necessary, by consulting a third review author (CG or SL).

We did not include any ITS or CBA studies. For a description of the methods we intended to use, see Appendix 1.

Overall risk of bias

We summarised the risk of bias on two levels: within studies (across domains) and across studies (for each primary outcome). Judgement on the overall risk of bias took into account the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered the bias to impact on the findings.

We deemed studies to be at highest risk of bias if they scored 'high risk' in one or more of the following domains: sequence generation; allocation concealment; or selective outcome reporting (based on growing empirical evidence that these three factors are the most important in influencing risk of bias) (Higgins 2011). We judged the overall risk of bias as low if we assessed these key domains as low risk of bias, unclear if we assessed one or more key domains as unclear risk of bias, and high if we assessed one or more key domains as high risk of bias.

For the assessment across studies, the main findings of the review have been set out in 'Summary of findings' (SoF) tables prepared using GRADE profiler software (GRADEpro 2008). We have listed the primary review outcomes for each comparison with estimates of relative effects, along with the number of participants and studies contributing data for those outcomes. For each individual outcome, we have assessed the certainty of the evidence using the GRADE approach (Balshem 2011), which involves consideration of limitations in design, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, publication bias, magnitude of the effect, dose‐response effect and other plausible confounders. We have expressed the results as one of four levels of certainty (high, moderate, low or very low).

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous outcomes

For the included RCTs, we have recorded outcomes in each comparison group. Where possible we recorded or calculated risk ratios (RRs) for dichotomous outcomes. Where adjusted analyses were reported, we used estimates of effect from the primary analysis reported by the investigators and converted these to RRs, if possible.

Interrupted time series

We did not include any ITS studies. For a description of the methods we intended to use, see Appendix 1.

Continuous outcomes

For continuous outcomes, we have reported adjusted mean differences with 95% confidence intervals. We did not combine data from continuous outcomes. For a description of the methods we intended to use, see Appendix 1.

Studies reporting multiple measures of the same outcome

This issue did not arise for the studies included in this review. The methods we intended to use to manage this are described in Appendix 1.

Unit of analysis issues

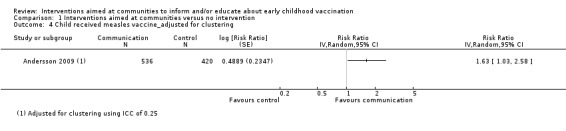

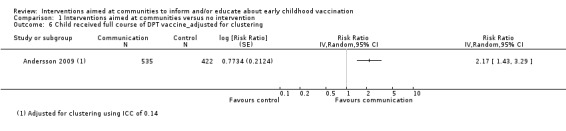

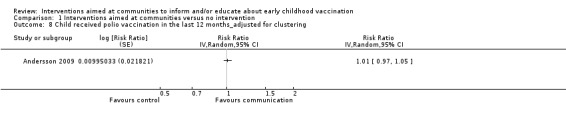

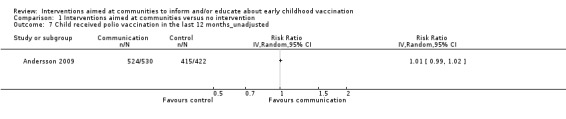

Both included trials were cluster‐randomised. Although the results of these studies were adjusted for clustering, Andersson 2009 did not report risk ratios or intracluster correlation coefficients (ICCs) and further analysis was therefore required to calculate these. As this trial provided data on the cluster level, a formal re‐analysis was possible. For the outcome 'Proportion of children (12 to 23 months) reported to have received measles vaccine', we estimated the ICC as 0.25, and for the 'Proportion of children (12 to 23 months) reported to have received a full course of DPT (diphtheria, pertussis and tetanus) vaccine', we estimated the ICC as 0.14. We then used the more conservative ICC of 0.25 for re‐analysis of the polio data from Andersson 2009 (for which insufficient information was available to calculate an ICC).

Dealing with missing data

We contacted the study authors where outcome data were unclear or not reported fully.

For all outcomes, we planned to carry out analysis, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat basis. That is, we planned to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses, and to analyse data according to initial group allocation irrespective of whether or not participants received, or complied with, the planned intervention. For the two studies included in the review, intention‐to‐treat analysis was not applicable as these were cluster‐RCTs and the individual patient data were drawn from cross‐sectional surveys of children's immunisation status.

When assessing adverse events, adhering to the principle of 'intention‐to‐treat' may be misleading. We therefore planned to relate the results to the treatment received. This means that for side effects, we planned to base the analyses on the participants who actually received treatment and the number of adverse events that were reported in the studies. We did not undertake analysis of adverse events as neither of the included studies reported such data.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Since we did not combine data for any of the outcomes, assessment of heterogeneity is not possible. The method for how we intended to do this is described in Appendix 1.

Assessment of reporting biases

We had planned to generate funnel plots if more than 10 studies reported the same outcome of interest ‐ see Appendix 1.

Data synthesis

We have presented the results from the included studies in 'Summary of findings' tables (see Higgins 2011, chapter 11), prepared using the GRADE profiler software (GRADEpro 2008). Since the review included study results that could not be pooled because the settings and/or interventions were too heterogeneous, we have described the results in a narrative form. We have included the narrative information in the 'Summary of findings' table.

For a description of how we had planned to combine and present an overall estimate of treatment effect if more than one study had examined similar interventions, see Appendix 1.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Subgroup analyses were not possible due to the small number of studies included in this review. The planned methods for subgroup analysis are described in Appendix 1.

Sensitivity analysis

As there was a small number of included studies and because meta‐analysis was not conducted, it was not possible to carry out a sensitivity analysis to examine the effects of removing studies at overall high risk of bias across domains (based on 'Risk of bias' assessment within studies). As no individually randomised trials were included, we did not carry out a sensitivity analysis to examine the effects of removing data obtained from cluster‐randomised trials from meta‐analyses combining data from both individually and cluster‐randomised trials.

Consumer participation

Those with an interest in this review include vaccine programme managers, policy‐makers, practitioners and other community members (for example, parent interest groups, caregivers and family members of young children, teachers). The topic of this review was identified through a series of deliberative forums with stakeholders, as part of the 'Communicate to vaccinate 1' (COMMVAC 1) project (www.commvac.com). Reports of two of these deliberative forums are available on the COMMVAC website (see: http://www.commvac.com/publications.html#deliberative). In addition, in the peer review process we have liaised with the Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group to seek external referees reflecting the interests of relevant stakeholder groups.

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies.

Results of the search

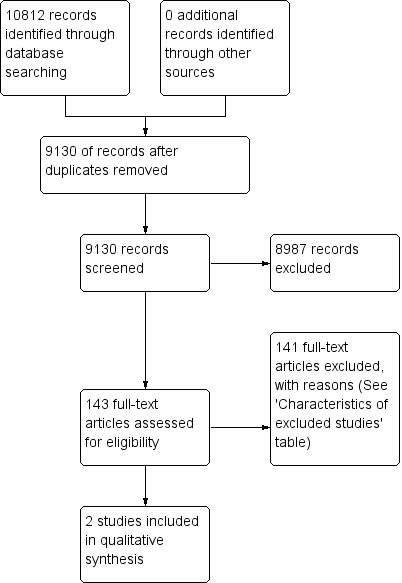

We identified a total of 9130 records from the electronic databases (see flow chart of study selection in Figure 1). Of these, we excluded 8987 references based on titles and abstracts and retrieved 143 references in full text and assessed them for eligibility. We included two studies.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Two cluster‐randomised studies were included in this review (Andersson 2009; Pandey 2007): see Characteristics of included studies, which reports the numbers of participants who were assessed for the various outcomes and the details of the interventions delivered. Both studies compared interventions aimed at communities to inform and/or educate about early childhood vaccination with routine immunisation practices. We obtained additional data from the study authors for Pandey 2007.

Pandey 2007 involved 1050 households selected from 21 districts in the northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. At baseline, 46% of children in the control and intervention sites were immunised. Both low‐, middle‐ and high‐income households were included. Andersson 2009 involved 32 enumeration areas (including 5641 children) from a lower‐middle‐income district in Pakistan's Balochistan province. Each enumeration area included four or five villages. At baseline, measles vaccination rates among children (12 to 23 months) were 49% and 47% in the trial control and intervention clusters, respectively. For DPT (full schedule), they were 45% and 51%, respectively; and for polio vaccine in the last 12 months they were 100% and 99%, respectively.

In the Pandey 2007 study, the intervention consisted of information campaigns in each intervention cluster, conducted in two rounds separated by two weeks. Each round consisted of two to three meetings with each meeting lasting about one hour and consisting of a 15‐minute audiotape presentation that was played twice and opportunities to ask questions. Posters and leaflets were also distributed in the intervention villages (Pandey 2007). The intervention in the Andersson 2009 study comprised three phases of discussions in each community with small community groups of 8 to 10 people. In the first phase, the community groups considered information about child vaccination in their area and why vaccination might be important. In the second phase, the groups discussed the costs and benefits of vaccination, including the complications related to vaccine‐preventable illnesses and the adverse effects of vaccination. In the third phase, the groups considered the challenges to child vaccination in their settings and developed local action plans to address these, including ways to extend the discussions about vaccination to others in their community and ways to improve vaccination service access. Group participants were encouraged to share the information and continue the dialogue with households in their communities. The interventions were aimed at parents, other family members, village leaders, children and sometimes teachers (Pandey 2007) and, for Andersson 2009, at people selected because they were perceived to be trusted within their community and able to convince others.

We did not identify any studies that compared interventions aimed at communities to inform and/or educate and other interventions to promote immunisation uptake; or studies that compared these interventions with no intervention.

Excluded studies

We excluded 141 studies after screening the full texts (see Characteristics of excluded studies). The main reasons for exclusions were that the intervention or study design used did not meet our inclusion criteria.

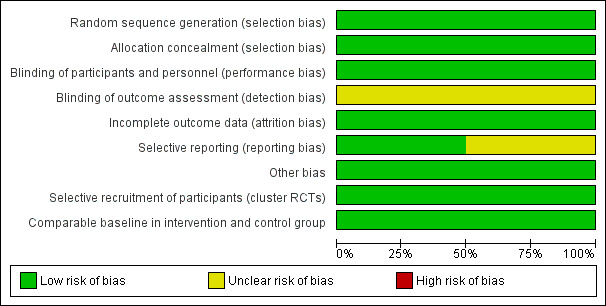

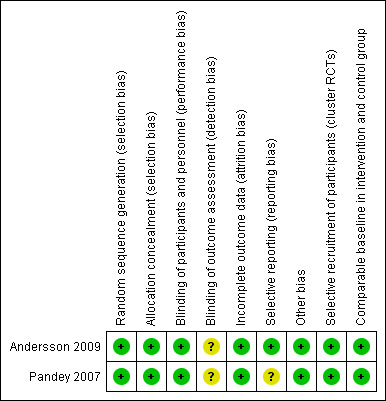

Risk of bias in included studies

Assessments of risk of bias for the included studies are shown in the Characteristics of included studies table and are summarised in Figure 2 and Figure 3. We have reported risk of bias across all outcomes for each study as we assessed that the risk of bias did not differ significantly across outcomes within the studies. We judged both the included studies to be of unclear to low risk of bias, since they had low risk of bias for sequence generation; low risk of bias for allocation concealment; and low (Andersson 2009) or unclear (Pandey 2007) risk of bias for selective outcome reporting. These were the factors that we had determined a priori to be the most important in influencing overall risk of bias.

2.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Both studies were at low risk of bias for random sequence generation. A random number generator was used to select communities for assignment to intervention and control groups. Allocation concealment was adequately described in one of the studies (Andersson 2009), but not mentioned in Pandey 2007.

Blinding

For these interventions, it was not possible to blind participants in the intervention clusters to receipt of the intervention. However, the clusters were spread geographically, so the risk of contamination between the clusters was probably low. In both of the included studies the field co‐ordinator for the surveys knew which clusters had received the intervention but the interviewers did not. The follow‐up interviews were performed by a research assistant who had no knowledge of the intervention. We assessed the studies to be at low risk of bias for performance bias, but unclear risk of bias for detection bias. We assess it as unlikely that it was possible to maintain the blinding of the people who performed the analysis.

Incomplete outcome data

We assessed the included studies to be at low risk for attrition bias. There was no loss of clusters in the Andersson 2009 trial and all loss of households in Pandey 2007 was accounted for by households having moved to another area prior to the final survey.

Selective reporting

We assessed Andersson 2009 as low risk as the published study protocol does not include any outcomes that were not assessed in the published trial report. For Pandey 2007, we were not able to identify a published protocol and were therefore not able to assess if all outcomes were reported. This domain was therefore assessed to be at unclear risk of bias.

Other potential sources of bias

We assessed that the trials were at low risk for other sources of bias.

Recall bias: information regarding the vaccination was obtained by interview. However, since any recall bias should have influenced both arms of the trial, we assessed the risk of bias to be low.

Selective recruitment of participants: as the study clusters were scattered geographically, it is unlikely that the participants knew which villages were control or intervention clusters. We therefore assessed this risk of bias to be low.

Groups comparable at baseline: there was a slightly uneven distribution of low‐caste versus mid‐to‐high‐caste households in one of the studies (Pandey 2007). However, we assessed the risk of bias to be low because the baseline differences were small. Willingness to travel to vaccinate was higher in intervention than control cluster (P value = 0.009) in the other study (Andersson 2009), but this was adjusted for in the analysis and we assessed the risk of bias to be low.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Comparison 1: Interventions aimed at communities to inform and/or educate about early childhood vaccination versus routine immunisation practices in the study setting

Two studies assessed interventions aimed at communities to inform and/or educate about early childhood vaccination, versus routine immunisation practices in the study setting (Andersson 2009; Pandey 2007).

Primary outcomes

Knowledge among participants of vaccines or vaccine‐preventable diseases

One study reported results that we assessed as addressing knowledge among participants of vaccine or vaccine‐preventable diseases (Andersson 2009). The outcome was measured by surveying whether respondents were aware of an illness preventable by vaccination. The trial suggested that the intervention may improve knowledge of vaccine‐preventable diseases among intervention participants (adjusted mean difference 0.121, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.055 to 0.189, low certainty evidence) at two years following the intervention. (Also see Table 3).

2. Data table for knowledge among participants of vaccine or vaccine‐preventable diseases, participants' attitudes towards vaccination and participant involvement in decision‐making regarding vaccination1.

| Outcome | Intervention clusters: number of parents (mean) | Control clusters: number of parents (mean) | Adjusted mean difference2 |

| Respondents were aware of an illness preventable by vaccination (knowledge) | 2368/3153 (mean 0.74) | 1437/2431 (mean 0.58) | 0.121 (95% CI 0.06 to 0.19) |

| Respondents thought it was worthwhile to vaccinate children (attitudes) | 3006/3161 (mean 0.95) | 2116/2475 (mean 0.84) | 0.054 (95% CI 0.01 to 0.11) |

| Mothers included in decisions about vaccination (involvement) | 1834/3131 (mean 0.59) | 1345/2434 (mean 0.54) | 0.043 (95% CI ‐0.01 to 0.1) |

Knowledge among participants of vaccine service delivery

The included studies did not assess this outcome.

Immunisation status of child

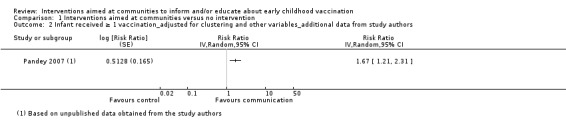

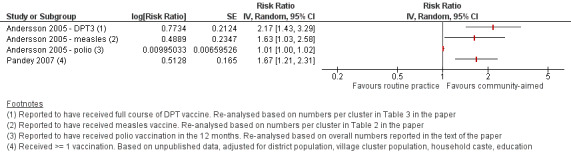

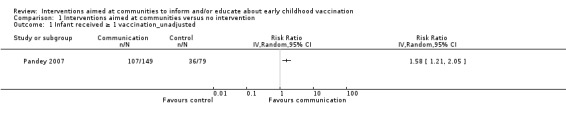

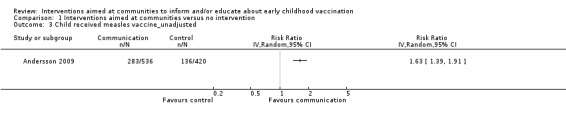

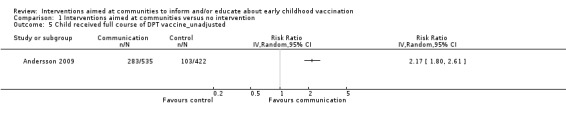

Children's immunisation status was measured in both of the included studies. However, it was not possible to pool these results as the interventions were too different. Pandey 2007 found that the intervention probably increases the number of children who received one or more vaccinations, compared to the control group (risk ratio (RR) 1.67, 95% CI 1.21 to 2.31, moderate certainty evidence, Analysis 1.2). For Andersson 2009, the results indicate that the intervention probably increase the uptake of both measles and the full course of diptheria, pertussis and tetanus (DPT) vaccines (RR 1.63, 95% CI 1.03 to 2.58 for measles, Analysis 1.4; RR 2.17, 95% CI 1.43 to 3.29 for DPT, Analysis 1.6). For both, the evidence was of moderate certainty. The intervention may make little or no difference to the number of children who received polio vaccination in the last 12 months (RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.97 to 1.05, low certainty evidence, Analysis 1.8). For polio, this may be because vaccination rates for both intervention and control sites were very high at baseline (see Analysis 1.7). Figure 4 summarises these findings.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Interventions aimed at communities versus no intervention, Outcome 2 Infant received ≥ 1 vaccination_adjusted for clustering and other variables_additional data from study authors.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Interventions aimed at communities versus no intervention, Outcome 4 Child received measles vaccine_adjusted for clustering.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Interventions aimed at communities versus no intervention, Outcome 6 Child received full course of DPT vaccine_adjusted for clustering.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Interventions aimed at communities versus no intervention, Outcome 8 Child received polio vaccination in the last 12 months_adjusted for clustering.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Interventions aimed at communities versus no intervention, Outcome 7 Child received polio vaccination in the last 12 months_unadjusted.

4.

Forest plot of comparison: Interventions aimed at communities versus routine immunisation practices, outcome: Immunisation status of child.

Any other measures of vaccination status in children

The included studies did not assess any other measures of vaccination status in children.

Unintended or adverse effects due to the intervention

None of the included studies reported any unintended or adverse effects due to the intervention.

Secondary outcomes

Participants' attitudes towards vaccination

One study reported results that we assessed to address participants' attitudes towards vaccination (Andersson 2009). The outcome was measured by surveying whether parents of children aged 9 to 60 months thought it was worthwhile to vaccinate children. The trial suggested that the intervention may change attitudes ‐ in this group in favour of vaccination (adjusted mean difference 0.054, 95% CI 0.013 to 0.105, low certainty evidence), at two years following the intervention. (Also see Table 3).

Participant involvement in decision‐making regarding vaccination

One study reported results that we assessed to address participant involvement in decision‐making regarding vaccination (Andersson 2009). The outcome was measured by surveying whether mothers in the study sites in Pakistan were included in household decisions about childhood vaccination. The trial suggested that the intervention may make little or no difference to mothers' involvement in decision‐making regarding vaccination (adjusted mean difference: 0.043 (95% CI ‐0.009 to 0.097), low certainty evidence), at two years following the intervention. (Also see Table 3).

Participant confidence in the decision made regarding vaccination

The included studies did not assess this outcome.

Resource use or cost of the intervention

The included studies did not assess this outcome. Some uncontrolled data on the costs of the interventions are reported in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Comparison 2: Interventions aimed at communities to inform and/or educate about early childhood vaccination versus interventions directed specifically to individual parents or caregivers of children

We did not identify any eligible studies that compared interventions aimed at communities to inform and/or educate about early childhood vaccination with interventions directed specifically to individual parents or caregivers of children.

Comparison 3: One community‐aimed intervention to inform and/or educate about early childhood vaccination versus another community‐aimed intervention to inform and/or educate

We did not identify any eligible studies that compared one community‐aimed intervention to inform and/or educate about early childhood vaccination with another community‐aimed intervention to inform and/or educate.

Discussion

Summary of main results

The two randomised controlled trials (RCTs) identified by this review show low certainty evidence that interventions aimed at communities to inform and educate about childhood vaccination may improve knowledge of vaccine‐preventable diseases and probably improve the immunisation status of children. The study in India showed that these interventions probably increase the number of children who received one or more vaccinations. The study in Pakistan showed that there is probably an increase in the uptake of both measles and diptheria, pertussis and tetanus (DPT) vaccines, and that there may be little or no difference in the number of children who received polio vaccine. There is also low certainty evidence that these interventions may change attitudes in favour of vaccination among parents with young children, but may make little or no difference to the involvement of mothers in household decision‐making regarding childhood vaccination. The included studies did not assess the other review outcomes including knowledge among participants of vaccine service delivery; participant confidence in the decision made regarding vaccination; or any unintended adverse effects as a consequence of the intervention (see Table 1). The sparse data available for several outcomes indicate that further trials are needed.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

This review considered studies with a wide range of designs and is based on comprehensive searches, following the methods recommended by The Cochrane Collaboration and the Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group and without language or publication status restrictions. However, searches in this area are challenging for several reasons: firstly, there is no single term used in the literature to describe interventions aimed at communities to inform and educate about early childhood vaccination. These interventions encompass a wide range of different approaches and strategies, each of which may be indexed differently within the major medical databases. Secondly, studies are generally not indexed on the basis of the purpose of the intervention, i.e. to inform and educate. Thirdly, although filters have been developed to identify the range of study designs included in this review, these filters may not identify all relevant published studies. It is therefore possible that eligible studies were missed despite our efforts. Finally, it is also possible that we missed eligible non‐randomised studies, published in the grey literature, of interventions aimed at communities. However, we undertook searches of the Grey Literature Report and Open Grey to attempt to identify such studies.

The review searched for RCTs, quasi‐RCTs, controlled before‐and‐after (CBA) studies and interrupted time series (ITS) studies. We included this range of designs as randomisation may not be feasible for some interventions aimed at communities, such as those delivered through mass media. Such interventions may be best assessed using ITS studies. For interventions aimed at specific small groups in communities, such as women's groups, randomised approaches may be both feasible and desirable. Given the focus of this review on interventions aimed at communities, it is perhaps surprising that the two included studies were RCTs. Methodological work on the extent to which reviews on health systems questions identify non‐randomised studies when their selection criteria include these suggests that this is variable, and may depend on whether the intervention addresses governance, financial or delivery arrangements (Glenton 2013). As non‐randomised studies are believed to be at higher risk of bias and their inclusion entails a considerable effort, further work is needed on the types of questions for which these designs are likely to be used, including within the field of vaccination communication, and where they may add value to the evidence obtained from RCTs.