Abstract

The emergence of drug resistance against the frontline antimalarials is a major challenge in the treatment of malaria. In view of emerging reports on drug-resistant strains of Plasmodium against artemisinin combination therapy, a dire need is felt for the discovery of novel compounds acting against novel targets in the parasite. In this study, we identified a novel series of quinolinepiperazinyl-aryltetrazoles (QPTs) targeting the blood stage of Plasmodium. In vitro anti-plasmodial activity screening revealed that most of the compounds showed IC50 < 10 μM against chloroquine-resistant PfINDO strain, with the most promising lead compounds 66 and 75 showing IC50 values of 2.25 and 1.79 μM, respectively. Further, compounds 64–66, 68, 75–77 and 84 were found to be selective (selectivity index >50) in their action against Pf over a mammalian cell line, with compounds 66 and 75 offering the highest selectivity indexes of 178 and 223, respectively. Explorations into the action of lead compounds 66 and 75 revealed their selective cidal activity towards trophozoites and schizonts. In a ring-stage survival assay, 75 showed cidal activity against the early rings of artemisinin-resistant PfCam3.1R539T. Further, 66 and 75 in combination with artemisinin and pyrimethamine showed additive to weak synergistic interactions. Of these two in vitro lead molecules, only 66 restricted rise in the percentage of parasitemia to about 10% in P. berghei-infected mice with a median survival time of 28 days as compared to the untreated control, which showed the percentage of parasitemia >30%, and a median survival of 20 days. Promising antimalarial activity, high selectivity, and additive interaction with artemisinin and pyrimethamine indicate the potential of these compounds to be further optimized chemically as future drug candidates against malaria.

This study offers compounds (66 and 75) as a new class of antimalarials, which are active against ACT-resistant strains of the Plasmodium and target several proteins of malaria parasite including the PfGAP50 protein.

Introduction

Malaria is one of the most deadly forms of parasitic diseases, severely affecting people's health and the socioeconomic growth of several developing countries having a large mass of population. Five species of Plasmodium (P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. ovale, P. malariae and P. knowlesi) are known to cause malaria in humans; of which P. falciparum (Pf) is the deadliest and is responsible for 80% of worldwide infections with the distribution ranging from tropics to temperate zones.1 Malaria infection is spread amongst humans through the bite of the infected female Anopheles mosquito. According to the World Health Organization (WHO)'s World Malaria Report 2022,2 about 247 million malaria infection cases were reported in 2021 with 619 000 deaths globally. The number of malaria cases increased between 2020 and 2021, but at a slower rate than in the period from 2019 to 2020 (WHO, 2022).2 Despite the concerted efforts by health authorities to confront the onset of infection and enhanced mortality rate, malaria still ranks the topmost widespread life-threatening disease in the world along with tuberculosis and HIV.3

Currently, almost all antimalarial drugs face the problem of resistance, causing a massive financial and emotional burden on public health of all developing countries.2–5 Though artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) is still one of the first-line treatments for the management of malaria, the development of resistance against ACT, which first sprang in the greater Mekong sub-region and is now rising in Africa, is a major cause of concern in malaria therapeutics.5 Therefore, there is an urgent need for identifying novel antimalarial drugs acting through novel mode(s) of action against the drug-resistant strains of malaria parasite.

The basic idea behind the ACT administration is that combination of two different drugs/pharmacophores would overcome the drug resistance phenomenon, and the combination drug prolongs the half-life of artemisinin. In the past decade, the hybrid drug approach has evolved as an emerging concept in drug discovery, specifically to overcome the drug resistance phenomenon.6 The hybrid approach involves mainly three modes of interactions (of the drug molecule) with the target: first, both pharmacophores will act on a single target; second, both pharmacophores act independently on two different targets; and third, these pharmacophores act on two related targets simultaneously.7 A combination of two drugs/active pharmacophores of two different drugs in a single moiety acting on the same or different targets would result in synergistic effects, i.e. acting more efficiently over the combination therapy. Hybrid drugs would also have a single PK profile, a single rate of ADME fate and reduced risk of drug interactions by lowering the competition for plasma protein binding.8

Although a number of drug targets against malaria have been explored for the development of potential drugs against the parasite, developing a drug targeting heme is still considered a viable option.9 Second, the merit of developing hybrid drugs containing diverse biologically active pharmacophores is being increasingly recognized.10,11 In the present study, we designed and synthesized hybrid molecules harbouring quinoline–piperazine as one composite partner linked to aryl tetrazoles as the second partner. It is important to note that quinolines, which were the first successful antimalarials in the form of quinine and chloroquine, exhibit their antimalarial action by virtue of their ability to bind to heme and inhibit the vital process of heme detoxification via the formation of hemozoin or the malaria pigment. In the same tone, it can be said that tetrazole ring-bearing compounds are endowed with a promising antimalarial activity12 due to the exceptional binding affinity of the tetrazole ring for heme, which halts the bio-crystallization of toxic α-hematin to nontoxic β-hematin.13–15 Till date, only a limited number of reports are available regarding the use of tetrazole scaffolds for the antimalarial activity.16

Although piperaquine had no major advantages over chloroquine, the drug got approved in China in early 1978 considering its efficacy against CQ-resistant strains of plasmodium. However, soon after its approval, piperaquine encountered a drug resistance sequel, and its use as monotherapy in Africa was not recommended. Further, in the search for the development of new therapeutics which could halt the drug resistance phenomenon, dihydroartemisinin has been chosen as a piperaquine's partner drug for combination therapy.17 Despite all the efforts to circumvent the drug resistance phenomenon, drug resistance against the clinically used drugs remains a major stumbling block in antimalarial drug development.18

Tetrazole scaffold is known to possess a broad spectrum of biological activities, and proven ADME and pharmacokinetics profile, as reflected in in vitro and in vivo studies.19,20 The outcome of these studies is based on the design of heme oxygenase inhibitors and studies on tetrazole-myoglobin complexes, clearly justifying the high affinity of the tetrazole moiety for the iron of heme.21,22 The key role played by heme as a promising target in antimalarial drug therapeutics and the results of the above-mentioned study prompted us to incorporate a tetrazole ring as a coupling partner with a chloroquine–piperazine scaffold, which could result in improved antimalarial activity and efficacy against the drug resistance phenomenon in Plasmodium.

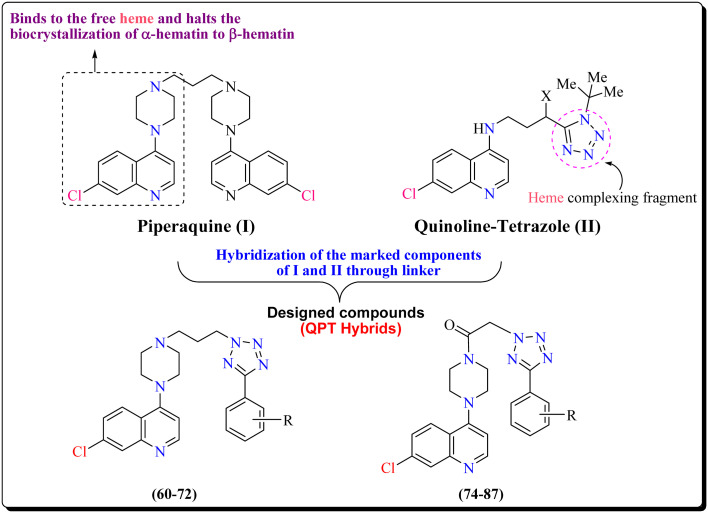

In continuation of our efforts23–28 for the development of novel heterocyclic compounds effective against the malaria parasite, we herein disclose a novel series of quinolinepiperazinyl-aryltetrazole (QPT) hybrids effective against the asexual blood stage of the parasite. Our design strategy includes the integration of the active pharmacophore 7-chloro-4-piperazinylquinoline, with the aryltetrazole scaffold through a linker to offer hybrid molecules (60–72 and 74–87; Fig. 1). We have varied the chemical space in between the two moieties of the designed molecules by choosing either propane or ketoethane linkers. It has been tried to change the electron density in the tetrazole ring by varying the substituents at different positions in the phenyl ring attached to the tetrazole ring. Herein, we report some interesting findings showing the effect of these substituents and the linker on the anti-plasmodial activity and resistance indices of the designed hybrid molecules.

Fig. 1. Designing strategy used for the development of novel hybrid molecules targeting the asexual blood stage of P. falciparum.

Our study offers a new set of drug-like molecules targeting the asexual blood stages of the malaria parasite that could have bright prospects against other parasitic apicomplexans. This study presents a novel series of hybrid molecules active against Plasmodium, which could prove to be promising leads for future molecular optimizations to obtain novel drugs against resistant strains of malaria parasite.

Results and discussion

Chemistry

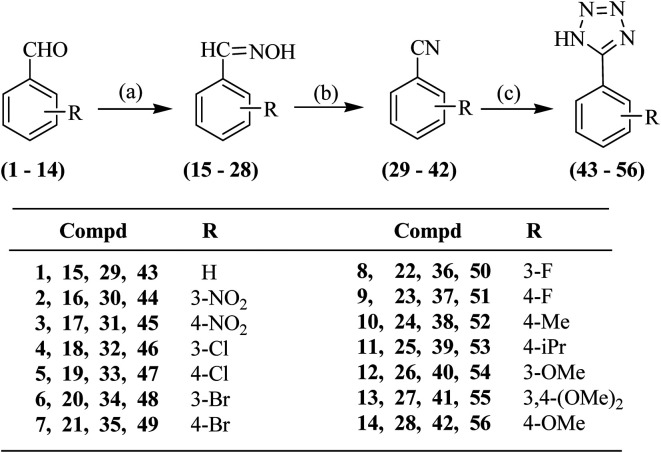

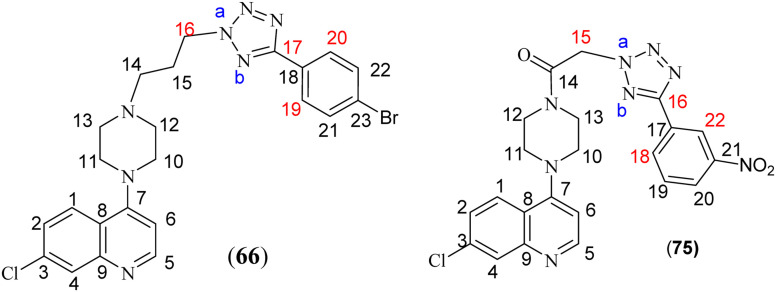

The synthesis of the proposed compounds was achieved as per Schemes 1–3. For the preparation of aryl-substituted tetrazoles, Scheme 1 was followed wherein commercially available substituted benzaldehydes (1–14) were reacted with hydroxylamine hydrochloride offering the oximes (15–28). The substituted aldoximes (15–28) were dehydrated using thionyl chloride yielding nitriles (29–42). 1,3-Dipolar cycloaddition of the benzonitriles (29–42) to sodium azide in the presence of ammonium chloride offered the desired 5-substituted 1H-tetrazoles (43–56) (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1. Synthesis of 5-(substituted phenyl)-1H-tetrazoles (43–56). Reagents and conditions: a) sodium acetate trihydrate, NH2OH·HCl, MeOH, reflux; b) SOCl2, dioxane, RT; and c) NaN3, NH4Cl, dry DMF, 120 °C.

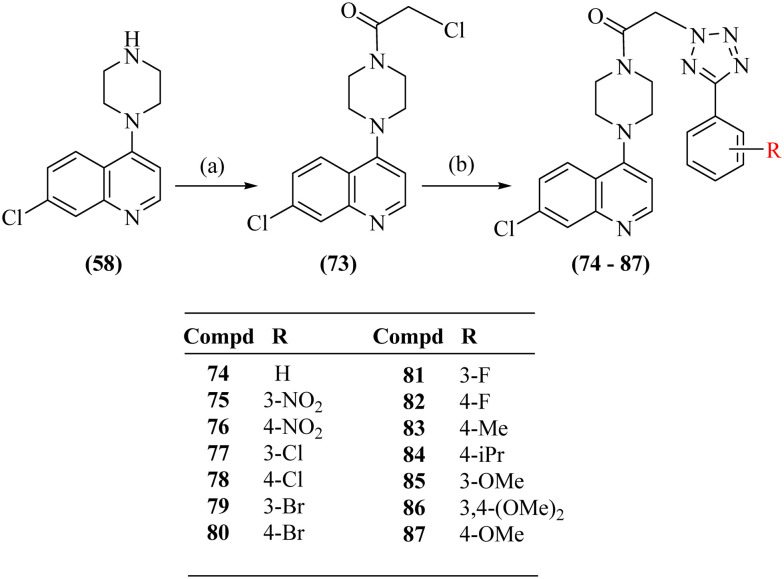

Scheme 3. Synthesis of 1-(4-(7-chloroquinolin-4-yl)piperazin-1-yl)-2-(5-(substituted phenyl-2H-tetrazol-1-yl)ethanones (74–87). Reagents and conditions: a) chloroacetyl chloride, triethylamine, dry DCM, RT and b) tetrazoles (43–56), K2CO3, dry DMF, 80 °C.

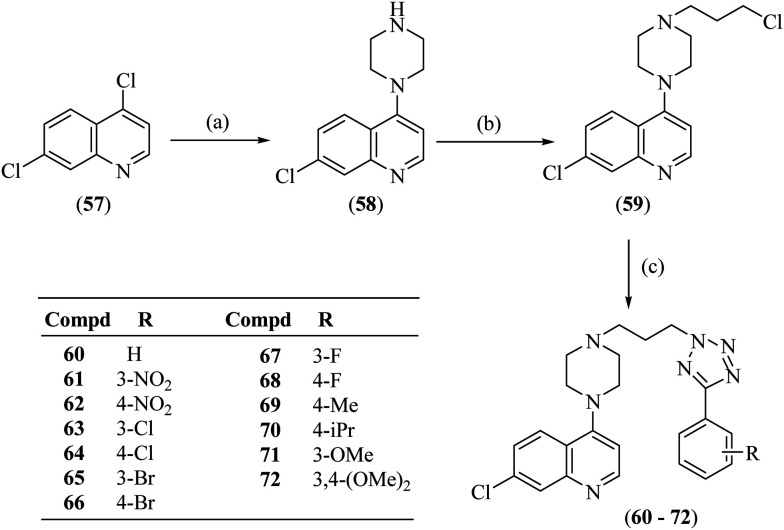

4,7-Dichloroquinoline (57) on reaction with anhydrous piperazine using triethylamine gave 7-chloro-4-(piperazin-1-yl)quinoline (58), which on alkylation with 1-bromo-3-chloropropane using sodium hydride in DMSO offered 7-chloro-4-(4-(3-chloropropyl)piperazin-1-yl)quinoline (59). The synthesis of the titled compounds (60–72) was achieved by reacting compound 59 with 5-substituted 1H-tetrazoles (43–55) in the presence of potassium carbonate in dry DMF, as shown in Scheme 2.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of 7-chloro-4-(4-(3-(5-(substituted phenyl)-2H-tetrazol-2-yl)propyl) piperazin-1-yl)quinolines (60–72). Reagents and conditions: a) anhydrous piperazine, triethyl amine, 110 °C; b) 1-bromo-3-chloropropane, NaH, DMSO, RT; and c) tetrazoles (43–55), K2CO3, dry DMF, 80 °C.

It is interesting to note that alkylation in the tetrazole ring in compounds 60–72 takes place at position-2 rather than position-1. This could be because of the steric hindrance at position-1 put forward by the presence of the attached aryl moiety at position-5. The substitution of the alkyl chain at position-2 of tetrazole was ascertained by ‘selective gradient NOESY’ and HMBC spectra of compound 66. In the ‘selective gradient NOESY’ spectrum of compound 66, NOESY interaction was not observed between the triplet of NCH2 protons [16-2H, δ 4.83–4.79] and the p-bromobenzene ring protons [19-H and 20-H]. In the HMBC spectrum, the tetrazole ring quaternary carbon [17-C, δ 163.20] showed no correlation with the triplet of N–CH2 protons [16-2H, δ 4.83–4.79] (ESI,† S4). This means the alkyl chain is attached to nitrogen Na and not to Nb, confirming substitution at position-2 of the 5-aryltetrazole ring system in compound 66. This was further confirmed by X-ray crystallography of a similar compound formed under the same reaction conditions.29

In the second series, 7-chloro-4-(piperazin-1-yl)quinoline (58) on acylation with chloroacetyl chloride in the presence of triethylamine in dry DCM offered 2-chloro-1-(4-(7-chloroquinolin-4-yl)piperazin-1-yl)ethanone (73) (Scheme 3). The synthesis of the targeted compounds 74–87 was achieved by reacting compound 73 with 5-substituted 1H-tetrazoles (43–56) using potassium carbonate in dry DMF. The substitution of CH2 of the acetyl group at position-2 of the tetrazole ring was also confirmed by the ‘selective gradient’ NOESY and HMBC spectra of compound 75. In the ‘selective gradient NOESY’ spectrum of compound 75, the singlet of NCH2 protons [15-2H, δ 6.16] did not show any NOESY interaction with the m-nitrobenzene protons [18-H and 22-H, δ 8.78–8.77 & δ 8.51–8.49 respectively]. In its HMBC spectrum, the tetrazole ring quaternary carbon [16-C, δ 162.45] showed no correlation with the singlet of NCH2 protons [15-2H, δ 6.16], indicating the attachment of the side chain to Na of the tetrazole ring and not to Nb in compound 75, as seen in compound 66 (ESI† S11 and S12).

Biological evaluation and molecular modelling studies

Determination of the anti-plasmodial activity and mammalian cell cytotoxicity

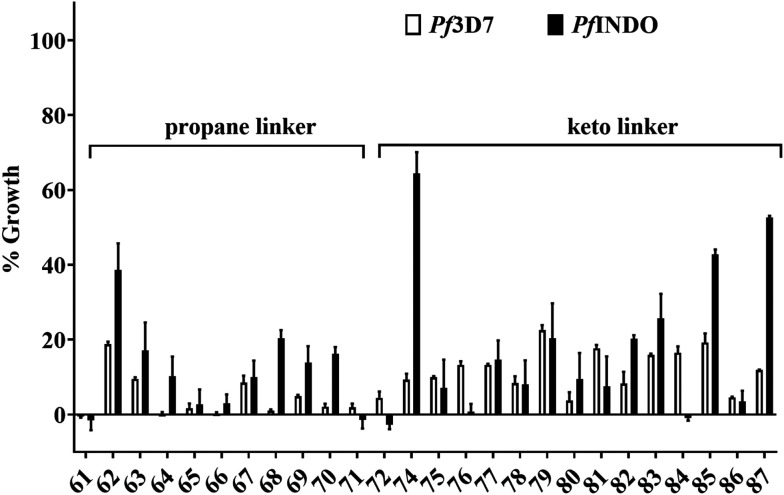

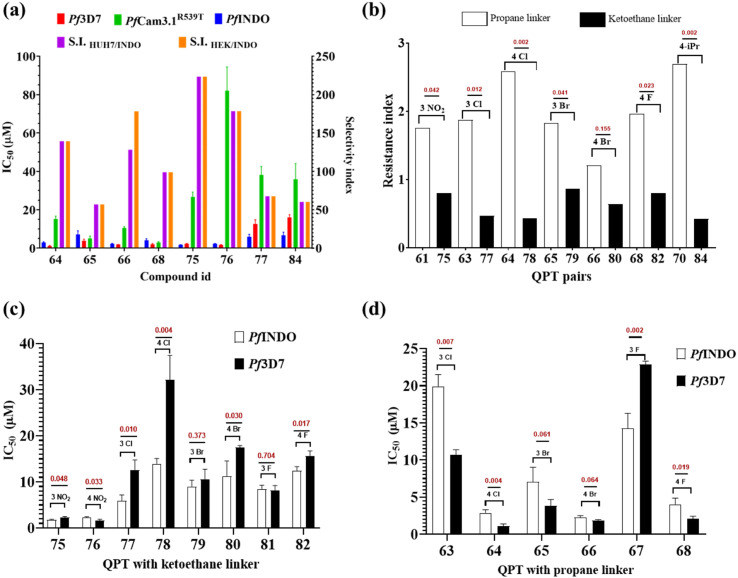

For preliminary investigation, the molecules were first screened at 100 μM concentration against chloroquine-sensitive 3D7 (Pf3D7) and resistant INDO (PfINDO) strains of P. falciparum. The molecules that showed growth inhibition of more than 50% were selected for further studies (Fig. 2). Based on this criterion, 21 molecules were selected for the determination of their IC50 and resistance index (R.I.) values against the CQ sensitive and CQ-resistant strains of P. falciparum. Among these 21 molecules, only eight compounds showed promising activity against the CQ-resistant strain of P. falciparum (Table 1). The selected eight molecules were further evaluated for their activity against multi-drug-resistant strain (PfCam3.1R539T). It was seen that these molecules offered higher IC50 values against PfCam3.1R539T strain in comparison to the PfINDO strain (Fig. 3a). Since the PfCam3.1R539T strain is sensitive to piperaquine and chloroquine30 but shows high IC50 values for pyrimethamine and sulfadoxine, the high IC50 values observed for these eight test compounds could be attributed to the similarity in molecular target(s) of these compounds and of pyrimethamine and sulfadoxine. Since chemical modifications of only two types were carried out, i.e., change in the linker, and the substituents in the phenyl ring, the scope of SAR was restricted to only these two points. The 2-carbon acyl linker has offered more potent compounds against the CQ resistance strain of the parasite than the 3-carbon alkyl linker (Fig. 3b). Among the compounds having a 2-carbon acyl linker, substitution at 3-position of the phenyl ring offered more potent compounds than substitution of the same groups on position-4. Contrary to this, 4-position substituents offered more potent compounds than the 3-substituted derivatives in the series having a 3-carbon alkyl linker (Fig. 3c and d).

Fig. 2. Histogram showing the results of primary screening of quinolinepiperazinyl-aryltetrazoles (QPTs) tested at 100 μM against chloroquine-resistant (PfINDO) and chloroquine-sensitive (Pf3D7) strains using the SYBR Green I lysis method. Percent growth has been shown with reference to 100% growth for the untreated culture of malaria parasite. Bars represent mean ± standard deviation of the observed growth inhibition in triplicate samples.

Anti-plasmodial activity, cytotoxicity, resistance and selectivity indices of molecules selected from preliminary screening.

| Compd | IC50 (μM) | Resistance indexa | CC50 (μM) | Selectivity indexb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pf strains used | Mammalian cell lines used | ||||||

| INDO | 3D7 | INDO/3D7 | HUH7 | HEK293 | HUH7/INDO | HEK293/INDO | |

| 61 | 16.17 | 9.17 | 1.76 | 71.96 | >400 | 4.45 | 24.74 |

| 63 | 19.93 | 10.68 | 1.87 | >400 | >400 | 20.07 | 20.07 |

| 64 | 2.87 | 1.11 | 2.58 | >400 | >400 | 139.37 | 139.37 |

| 65 | 7.05 | 3.84 | 1.83 | >400 | >400 | 56.75 | 56.75 |

| 66 | 2.25 | 1.85 | 1.21 | 288.3 | 400 | 128.3 | 178.02 |

| 67 | 14.24 | 22.87 | 0.62 | >400 | >400 | 28.09 | 28.09 |

| 68 | 4.04 | 2.07 | 1.96 | >400 | >400 | 99.01 | 99.01 |

| 69 | 6.35 | 8 | 0.79 | 309.7 | >400 | 48.8 | 63.03 |

| 70 | 8.37 | 3.12 | 2.69 | >400 | >400 | 47.79 | 47.79 |

| 71 | 7.66 | 9.9 | 0.77 | >400 | 341.5 | 52.25 | 44.61 |

| 72 | 5.97 | 4.84 | 1.23 | 129.4 | >400 | 21.66 | 66.97 |

| 75 | 1.79 | 2.23 | 0.8 | 400 | >400 | 223.46 | 223.46 |

| 76 | 2.24 | 1.65 | 1.36 | >400 | >400 | 178.57 | 178.57 |

| 77 | 5.91 | 12.61 | 0.47 | >400 | >400 | 67.74 | 67.74 |

| 78 | 13.95 | 32.12 | 0.43 | >400 | >400 | 28.67 | 28.67 |

| 79 | 8.99 | 10.51 | 0.86 | >400 | >400 | 44.49 | 44.49 |

| 80 | 11.23 | 17.5 | 0.64 | >400 | >400 | 35.62 | 35.62 |

| 81 | 8.46 | 8.14 | 1.04 | >400 | >400 | 47.29 | 47.29 |

| 82 | 12.41 | 15.61 | 0.8 | 24.24 | >400 | 1.95 | 32.23 |

| 84 | 6.66 | 15.93 | 0.42 | >400 | >400 | 60.08 | 60.08 |

Resistance index: IC50 against resistant strain (PfINDO)/IC50 against sensitive strain (Pf3D7).

Selectivity index: CC50 against mammalian cell/IC50 against Plasmodial strain (chloroquine-resistant).

Fig. 3. Activity of selected hybrids against P. falciparum: (a) IC50 as observed in different strains of P. falciparum; (b) comparison of difference in resistance index observed among compounds with propane and ketoethane linkers. Compounds with propane linkers are showing a higher resistance index as compared to compounds with ketoethane linkers; (c) and (d) compares difference in IC50 observed with respect to meta and para substitution at the phenyl ring in QPT with ketoethane and propane linkers respectively. Note: the QPT with ketoethane linkers demonstrate low IC50 with meta substitution, whereas para substitution favors low IC50 in QPT with a propane inker. Note: the P value is shown in maroon in the graph above the bar (n = 3).

The selected compounds were also evaluated for their safety aspect (in terms of selectivity index) on kidney (HEK293) and liver (HUH7) cell lines. Among the selected molecules, eight compounds showed more than 50-fold selectivity for the parasite over the kidney and liver cells (Table 1). Amongst these, two compounds (66 and 75) showed an IC50 (PfINDO) value of <3 μM with a resistance index (RI) <1.5. Based on the selectivity index (SI), compound 75 (SI: 223) was the top hit molecule.

Effect of test compounds on different stages of cell cycle of chloroquine-resistant PfINDO strain of the parasite

Looking at the data of IC50 values against different cell cycle stages (Table 2), it seems that the preferential cell cycle stage targeted is Schizonts by 65, 66 and 75, trophozoites by 76 and 77, Rings by 68 and 84, and early schizonts and rings by 64. On the basis of these observations, one can hypothesize that the target protein(s) of these QPTs may be expressed at different stages of cell cycle of the malaria parasite life cycle.

Activity of the selected molecules against different cell cycle stages of PfINDO.

| Compound | IC50 (μM) against various stages of the parasite | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rings | Trophozoites | Schizonts (early) | Schizonts (late) | |

| 64 | 4.07 | 12.2 | 3.93 | 7.64 |

| 65 | 8.67 | 7.31 | 8.24 | 4.62 |

| 66 | 2.27 | 2.16 | 2.81 | 1.50 |

| 68 | 1.72 | 2.8 | 1.68 | 1.85 |

| 75 | 7.51 | 2.72 | 2.15 | 7.10 |

| 76 | 10.3 | 4.72 | 5.46 | 6.29 |

| 77 | 19.6 | 5.39 | 15.9 | 24.8 |

| 84 | 18.5 | 24.9 | 21.5 | 26.7 |

Stage-specific action of compounds 66 and 75 against P. falciparum

Considering the dual criteria of low anti-plasmodial IC50 and high selectivity index, compounds 66 (IC50 1.2 μM, SI 178) and 75 (IC50 0.8 μM, SI 223.4) were considered for further studies. These two molecules were taken as representatives of 2-carbon acyl and 3-carbon alkyl linkers to understand their effect on the parasite growth and development along with the in silico study to shed light on their binding interactions with Plasmodial proteins.

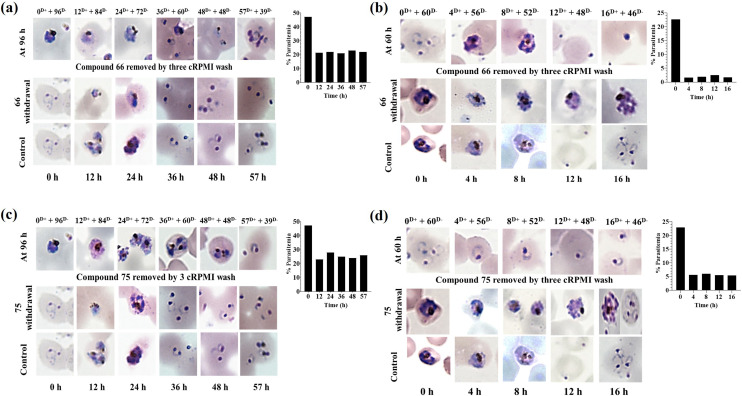

Kill kinetics of 66 and 75 against PfINDO rings and schizonts

To know about the time requirement for these two compounds to act on particular stage(s) of - Plasmodium, a study of time-dependent treatment of the rings and schizonts was done using 66 and 75. Briefly, rings (6 to 12 h, p.i.), early schizonts (32 to 36 h, p.i.) and late schizonts (42 to 45 h, p.i.) were treated with the test molecules for different time intervals followed by the centrifugal removal of the test molecules and washing with 1× PBS followed by incubation in drug-free media for the next one cycle of Plasmodium. The treatment of rings with 66 and 75 at 2.25 and 1.79 μM respectively displayed their activity in the initial 12 h treatment (Fig. 4a and c), leading to a decrease in the % parasitemia from ∼48 to ∼22. Following this 12 h treatment of the rings with the test compounds, further development of the surviving parasites got slowed down, but they were able to develop into mature schizonts and then ultimately to rings of the next cycle. Treatment of the schizonts with 5.62 and 4.30 μM of compounds (66 and 75) led to a decrease in the % parasitemia in initial 4 h treatment (Fig. 4b and d). Percent decrease was higher in case of 66 in comparison to 75. Post 4 h treatment, the surviving schizonts were unable to rupture in case of treatment with 66 (Fig. 4b). However, in case of 75, there was a successful rupture leading to the formation of rings (Fig. 4d). Therefore, it is clear from this study that 66 was capable of preventing schizont rupture, while 75 failed to stop rupture and subsequent invasion.

Fig. 4. Time kinetics of the effects of compounds 66 and 75 on the growth of PfINDO rings and schizonts. D+ and D− represent duration (h) of exposure (D+) with test molecules followed by culture in a test molecule-free medium (D−). (a) and (b) Effect of compound 66 on erythrocytic cycle (2.25 μM) and schizonts (5.62 μM) respectively. (c) and (d) Effects of compound 75 on erythrocytic cycle (1.79 μM) and schizonts (4.30 μM) respectively. Note: as shown in panels (b) and (d), 16 h treatment with 66 prevents schizont rupture, while 75 fails to do the same.

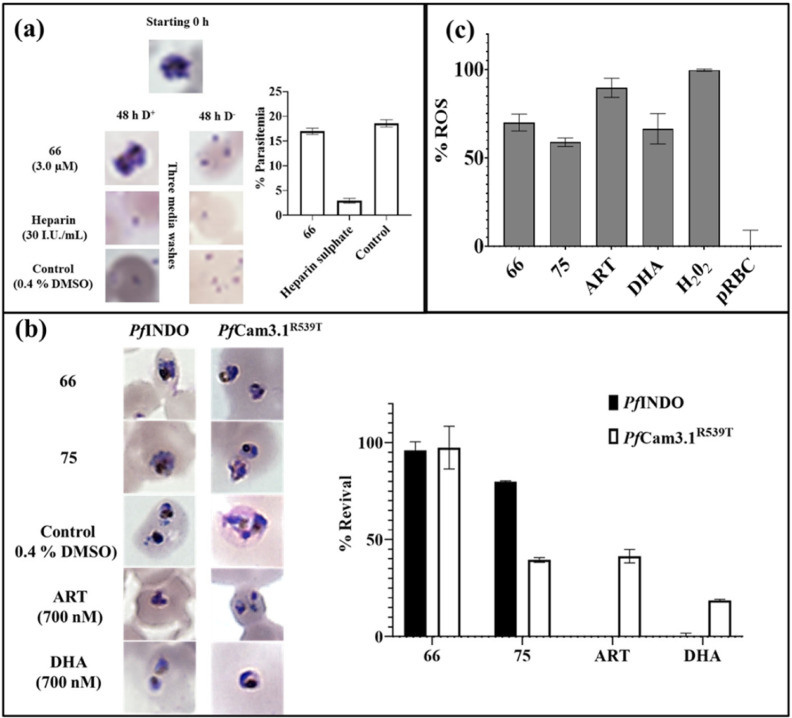

Schizonts rupture inhibition by compound (66)

Since post 16 h treatment with 66, the surviving schizonts were seen microscopically stuck and unable to rupture (Fig. 5b); therefore, schizont rupture inhibition by compound 66 was further confirmed by treatment of segmental stage schizonts (42 to 45 h, p.i.) with 2× IC50 [LS → ER] for 8 h, followed by the removal of the test compound from the media and growing the parasite in drug-free media for next 48 h. As shown in Fig. 5a, there is no rupture of schizonts when treated with 5.62 μM of 66; however, on removal of the test compound, although there is rupture the % parasitemia is no higher than that of the untreated control (DMSO, 0.4%).

Fig. 5. Difference and similarity in the mode of activity of compounds 66 and 75: (a) Schizont static activity of 66 at 3 μM; (b) use of 10× IC50 of 66 and 75 to check their efficacy against early rings in ART-sensitive PfINDO and ART-resistant PfCam3.1R539T strains using the standard ring-stage survival assay; (c) effect of 2× IC50 of 66 and 75 on the intracellular ROS levels in trophozoites [ET → LT] with ART and DHA as control. Data represent mean with SD of triplicate biological samples.

Ring-stage survival assay of ART-resistant strain in the presence of compounds (66 and 75)

In order to assess the activity of 66 and 75 against the ART-resistant strain (PfCam3.1R539T), a ring-stage survival assay was performed taking the artemisinin-sensitive chloroquine-resistant strain (PfINDO) as control. At 10× IC50 of these two molecules, compound 66 displayed no activity against early rings in CQ and ART-resistant strains (Fig. 5b), while 75 showed cidal activity against the early rings of artemisinin-resistant PfCam3.1R539T even as it did not kill the early rings of chloroquine-resistant PfINDO.

Evaluation of ROS production in the presence of compounds 66 and 75

Increase in ROS inside the cell is detrimental to the cellular organelles inhibiting the functioning of vital enzymes responsible for maintaining various cellular processes. PfINDO trophozoites (24 to 28 h, p.i.) [ET → LT] were treated with 2× IC50 of the compounds for 8 h, followed by measurement of oxidized DCF. Rise in ROS levels in the presence of 75 and 66 was somewhat comparable to that obtained in the presence of DHA/ART as control (Fig. 5c).

In vitro activity of the combination of compounds 75 and 66 with standard antimalarials

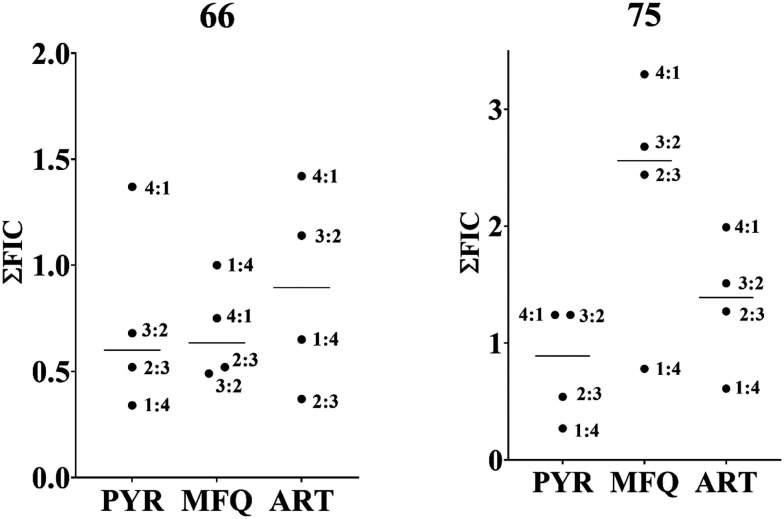

Using a fixed ratio method, it was seen that 75 and 66 were showing synergistic to additive activity when combined individually with pyrimethamine (PYR), mefloquine (MFQ) and artemisinin (ART) at all ratios against multi-drug-resistant PfCam3.1R539T strains. On comparing the average ∑FIC (Fig. 6), compound 66 showed synergistic activity with PYR and MFQ and additive activity with ART. Compound 75, however, showed strong antagonistic activity with MFQ and additive interaction with PYR and ART.

Fig. 6. Graphical representation of ∑FIC values of 66 and 75 against PYR and ART-resistant PfCam3.1R539T. Compound 66 synergizes with PYR and MFQ (∑FIC ≈ 0.5) and is additive with ART. Compound 75 shows additive interaction with PYR and ART but is antagonistic with MFQ. The synergistic activity of 66 with PYR and MFQ is of great significance in view of drug resistance observed against these three standard antimalarials (PYR, MFQ and ART).

Acute toxicity and antimalarial activity of compounds 66 and 75 in a mouse model of malaria

Acute toxicity in mice was performed as per OECD 423 guideline.31 Mice were fasted for 4 h prior to oral dosing of the test compounds at 100 mg kg−1 b. wt followed by observation of the mice for next 45 minutes to see any symptoms relating to acute toxicity (Table 3). As observed in the table, 66 and 75 did not exhibit any toxicity at 100 mg kg−1 b. wt. Hence, this dose was taken for their curative antimalarial activity.

Effect of the orally fed test compounds (100 mg kg−1 body wt) on body/physiological parameters in healthy test animals.

| Parameter | Compound | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 66 | 75 | Control | |

| Body weight | No change | No change | No change |

| Temperature | No change | No change | No change |

| Appetite loss | No loss | No loss | No loss |

| Water intake | Normal | Normal | Normal |

| Urination | Normal | Normal | Normal |

| Rate of respiration | Normal | Normal | Normal |

| Changes in skin | No change | No change | No change |

| Drowsiness | No | No | No |

| Sedation | No | No | No |

| Eye color | No change | No change | No change |

| Diarrhea | No | No | No |

| Lacrimation | No | No | No |

| Coma | No | No | No |

| Death | No | No | No |

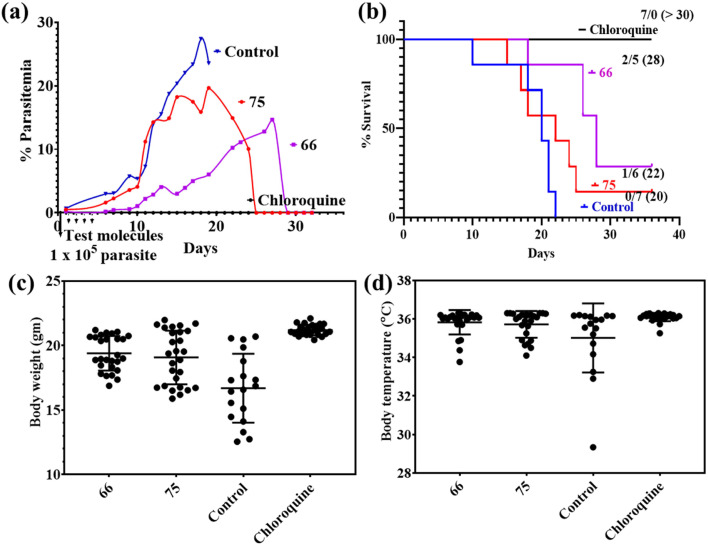

As shown in Fig. 7a and b, chloroquine was able to clear the malaria infection in all the animals with a median survival >30 days. Compound 66 was able to suppress the initial increase in the % parasitemia till day 27, after which there was an exponential rise in the % parasitemia with the death of 5 mice (median survival = 28 days). Compound 75 treatment led to complete clearance of infection in only one mouse with a median survival period of 22 days. Percent rise in parasitemia in fed mice (compound 75) was similar to untreated control. The inability of 66 and 75 to completely cure all mice of malaria was also correlated to some extent with fluctuations in body weight and temperature (Fig. 7c and d).

Fig. 7. Antimalarial efficacy of 66 and 75 given orally to P. berghei ANKA-infected mice. Panels (a–d) show the % parasitemia, percentage of survival, body weight and body temperature. Note the ability of 66 to suppress parasitemia and the consequent effect on increase in the mean survival time.

Putative target prediction for compounds 66 and 75

Encouraged by the results obtained in different studies performed for 66 and 75, it was planned to identify the putative targets in malaria proteome for these two compounds. Therefore, these two molecules were docked into 15 different proteins (Table 4) present in the parasite. The highest docking scores (−6.07 and 7.07 kcal mol−1) for both the molecules were seen in case of histo-aspartic protease (Hap) protein. Docking score comparison of 66 and 75 against different proteins highlights their probable targets to be proteases, HSPs and kinases.

Docking scores of compounds 66 and 75 against different proteins of malaria parasite. Proteins marked in bold are essential for the growth of the parasite.

| S. no. | Protein | PDB id | Docking score (kcal mol−1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 66 | 75 | |||

| 1. | Plasmepsin IV | 1LS5 | −5.796 | −5.341 |

| 2. | Cyclophilin | 1QNG | −3.371 | −2.813 |

| 3. | Peptide deformylase | 1RL4 | −4.337 | −4.105 |

| 4. | Pyruvoyl tetrahydropterin synthase (PTPS) | 1Y13 | −3.541 | −4.028 |

| 5. | Guanylate kinase | 1Z6G | −4.535 | −1.941 |

| 6. | Ser/Thr protein kinase | 2PMO | −5.782 | −5.102 |

| 7. | Malaria sporozoite protein UIS3 | 2VWA | −1.908 | −3.498 |

| 8. | Thymidylate kinase | 2YOG | −5.459 | −3.191 |

| 9. | β-Hydroxyacyl-acyl carrier protein dehydratase | 3AZB | −3.325 | −4.19 |

| 10. | Aquaglyceroporin | 3CO2 | −3.058 | −2.733 |

| 11. | GAP50 | 3TGH | −4.58 | −3.52 |

| 12. | HSP90 | 3PEH | −5.932 | −6.263 |

| 13. | Actin depolymerizing factor | 3Q2B | −1.697 | −3.636 |

| 14. | Histo-aspartic protease (hap) | 3QVI | −6.07 | −7.072 |

| 15. | PfGrx1 | 4MZB | −1.22 | −0.45 |

Among these proteins, peptide deformylase, Ser/Thr protein kinase, GAP50, HSP90, and actin depolymerizing factor are known to be the essential proteins involved in different cellular processes of Plasmodium.32–35 Among these five essential proteins, GAP50 was selected for an in vitro protein-based binding assay. The selection of this protein was based on its role in the formation of a glideosomal complex, which plays an important role in parasite invasion.36,37 Additionally, an extensive number of compounds are available for the targeting metabolic pathway of Plasmodium, but reports on a compound targeting the glideosomal complex,38,39 especially GAP50, are rare in the literature.

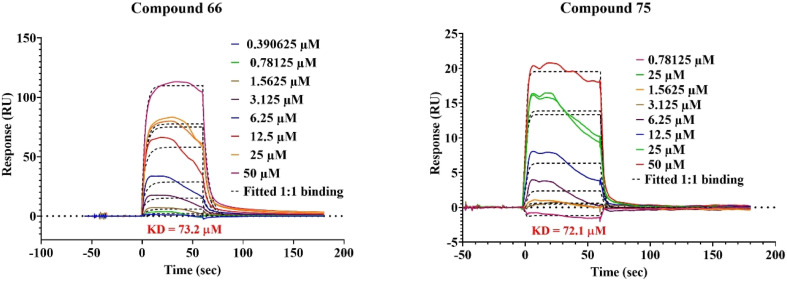

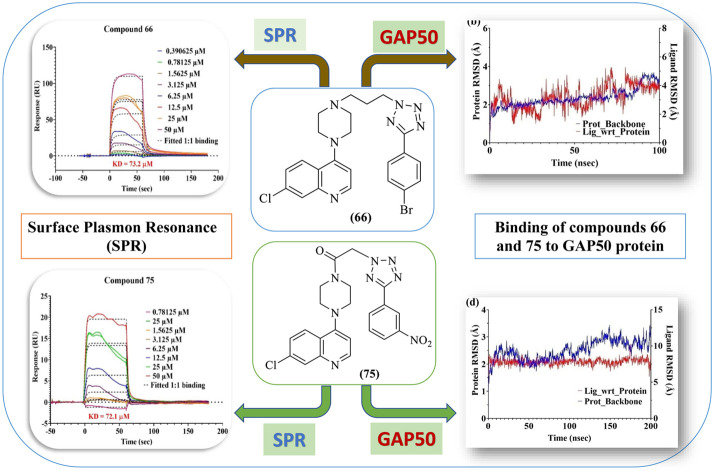

Binding of 66 and 75 with GAP50 as seen through surface plasmon resonance (SPR)

Binding of 66 and 75 with GAP50 on equimolar (1 : 1) basis studied by surface plasmon resonance indicated equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) values below 100 μM (Fig. 8). Further, the comparison of association and dissociation constants indicates that 66 is a fast associator, but dissociates slowly (Ka 2613 M−1 s−1; Kd 0.1913 s1) in comparison to 75, which is a slow associator and also a more slow dissociator (Ka 1922 M−1 s−1; Kd 0.0064 s1). This results in a similar equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) indicating similar affinities of 66 and 75 for GAP50.

Fig. 8. SPR sensorgram of 66 and 75 fitted using the 1 : 1 Langmuir binding model.

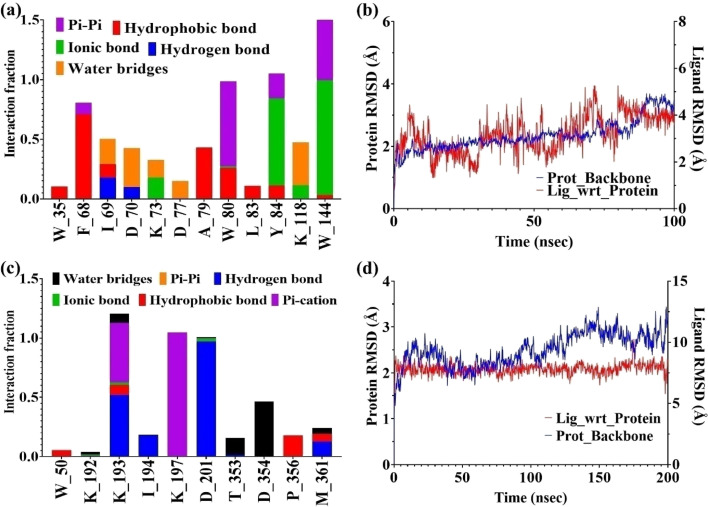

In silico binding studies of compounds (75 and 66) with GAP50

Using SPR (Fig. 8), it became clear that both 66 and 75 are binding with GAP50 (KD ~ 72 μM) in 1 : 1 binding interaction. Following this observation, their interaction with GAP50 was looked into in detail using in silico molecular dynamics keeping 0.15 M NaCl in water to maintain the physiological ionic strength. Post simulation, it was seen that binding of 66 with GAP50 is mediated by non-polar amino acids. Thus, molecule 66 establishes hydrophobic interactions with W35, F68, A79 and W80. Its binding is further strengthened by pi–pi interactions with W80 Y84 and W144. These interactions led to low-ligand RMSD with respect to the protein (Fig. 9a and b). In case of 75, protein residues specifically K193 (hydrogen bond and pi–cation), K197 (pi–cation) and D201 (hydrogen bond) were seen binding with the ligand throughout the simulation time and prevented it from moving away from the binding site (Fig. 9c and d).

Fig. 9. In silico determination of types of interactions and stability of 66 and 75 with GAP50: (a) and (c) different types of interactions shown between the amino acid residues of GAP50 and compounds (66 and 75) respectively; (b)and (d) RMSD deviation of 66 and 75 respectively in bound form with GAP50.

In silico binding of compounds 75 and 66 with PfCRT

Piperaquine resistance is implicated with mutations in PfCRT.40,41 Since the molecules reported in this work have a part of piperaquine core attached to the tetrazole moiety, we checked their binding with wild (PDB 6UKJ) and mutant drug-resistant PfCRT protein. Mutations in CRT residues42,43 such as M74I, N75E, K76Y, T93S, H97Y, F145I, I218F, A220S, N326S, M343L, G353V, I356T and R371I were used to differentiate the wild-type (CRTWT) and the mutant-type (CRTMT) CRT proteins. In silico docking scores of piperaquine, verapamil, and compounds 66 and 75 with wild-type and mutant PfCRT (Table 5) highlight lower docking scores towards PfCRTMT and higher docking scores against PfCRTWT. On comparing the docking scores of compounds 66 and 75 with that of piperaquine and verapamil against PfCRTMT and PfCRTWT, similar docking scores indicate the same level of interactions between these molecules and the PfCRT.

Comparison of docking scores (kcal mol−1) of piperaquine, verapamil and compounds (66 & 75) against the wild-type and mutant PfCRT proteins.

| PfCRT | Piperaquine | Verapamil | Comp (66) | Comp (75) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild | −2.69 | −2.67 | −3.29 | −2.00 |

| Mutant | −4.87 | −4.41 | −6.53 | −4.89 |

Further, in order to characterize the predicted binding, molecular dynamics simulation in the presence of 0.15 M NaCl was carried out for 100 ns. Since verapamil is known to induce the reversibility of chloroquine resistance,42 looking at the simulation interaction diagrams, we decided to check interaction of compounds 66 and 75 and the standard drugs verapamil and piperaquine with wild-type and mutant PfCRT also (Fig. S1 and S2†). Both compounds 66 and 75 exhibited stable interactions with PfCRT and were not getting diffused away from their docking sites in both wild-type and mutant PfCRT (Fig. S1c and d†).

Further discussion

Being one of the deadliest diseases,2 malaria killed 411 000 people in Africa in 2020 as compared to 409 000 in 2019.2 With no reduction in malaria-associated morbidity, and with the spread of artemisinin resistance in Africa,44 there is a dire need for a new molecule with a novel scaffold that can be included in ACTs. In this report, we combined the pharmacophores present in piperaquine with a heme-binding tetrazole moiety to create a heterocyclic molecular scaffold referred to as quinoline-piperazinyl-aryltetrazole. The in vitro MTT assay showed that these compounds possessed no toxicity at 400 μM against kidney and liver cell lines, signifying that the hybridized pharmacophore quinoline-piperazinyl-aryltetrazole can be safely used for developing novel drugs against malaria. Further, on studying their potencies against the CQ-resistant PfINDO strain, the IC50 values ranging from 19.93 μM (compound 63) to 1.79 μM (compound 75) were obtained. Since these derivatives were made by combining part of the piperaquine molecule, whose anti-plasmodial activity is similar to that of chloroquine,45–47 and tetrazole, their IC50 values against Pf3D7 and PfINDO were compared. Interestingly, ten molecules of the series were found to be more active against PfINDO strain leading to RI < 1, while the others had RI between 1 and 2.19. Since the % parasitemia rises exponentially at the end of every replicative cycle in the malaria infection, we aimed to understand the inhibitory activity of these compounds against the metabolically active stages of Plasmodium in comparison to the ring stage of P. falciparum. The determination of IC50 against different cell cycle stages of PfINDO highlighted compounds 64 to 68, 75 and 76 with IC50 < 10 μM against all the stages of the parasite. Based on SI, compounds 66 (Scheme 2) and 75 (Scheme 3) were selected for further evaluation of their anti-plasmodial activity. These two molecules elicited enhanced ROS in the parasite comparable to ROS levels seen with ART/DHA treatment. Piperazine and quinoline–tetrazole molecules are known to accumulate in food vacuoles and prevent conversion of free heme to hemozoin.15 Increased ROS levels by the test compounds can be attributed to the presence of piperazine, quinoline and tetrazole moieties present in these molecules. As these molecules have a tetrazole group, which is known to bind with free heme, the inhibition of detoxification mechanism of the heme might be the reason for increased ROS levels. Considering the fact that the ART resistance is on the rise, it is interesting to note that 75 was able to show activity comparable with ART (% inhibition ∼60) against ART-resistant strain PfCam3.1R539T. Contrary to 75 which showed no inhibition of schizont rupture, 66 was capable of preventing schizont rupture. Among a variety of proteins used for docking studies, PfGAP50 was selected for expression and purification, as this is an essential protein involved in the formation of an inner membrane complex in apicomplexan parasites.48 Further, as this protein is involved in merozoite invasion,38,49 targeting this protein might lead to halting of merozoite invasion with retardation of the exponential rise in the percentage of parasitemia. Using in silico and SPR-based methods, it was seen that 66 and 75 were interacting with this protein with similar docking scores and KD values, indicating that this quinoline-piperazinyl-aryltetrazole class of compounds are targeting glideosomal protein 50 (GAP50). Further structural modifications might be needed for increasing their affinities towards GAP50.

The in silico binding of these molecules with PfCRT protein was also explored, as they possess the quinoline moiety present in piperaquine, a drug known to interact with the PfCRT protein.41–43 Piperaquine resistance is mediated by mutations in the PfCRT protein, leading to a decrease in PfCRT protein binding to the aminoquinoline class of molecules, which subsequently leads to their exit from the food vacuole.43 From the molecular dynamics simulation, it became evident that interaction of 66 and 75 with mutant PfCRT protein is similar to verapamil, a molecule known to bind to PfCRT protein that prevents outward movement of the aminoquinolines. While interacting with the mutant PfCRT protein, piperaquine shows high fluctuations in the ligand RMSD, signifying its non-stable interaction with the PfCRT protein, which leads to its expulsion from the food vacuole. In short, the difference in interaction profile of the studied QPTs in comparison to piperaquine suggests that 66 and 75 should have similar IC50 values in CQ-sensitive as well as-resistant strains of the parasite. This was further confirmed by their in vitro anti-plasmodial RI which was found to be <2 for 66 and 75. The strong in vitro anti-plasmodial activity of 66 was also reflected in the mouse model of malaria, where this compound was found to suppress parasitemia to <10% till day 22.

To summarize, we have a unique group of heterocyclic molecules, which are active towards CQ-resistant parasites that are capable of targeting different blood stages of Pf. Further modifications of these molecules could increase their potency as well as their binding affinity towards the putative target proteins.

Conclusion

In this paper, we have reported some novel molecules designated as quinolinepiperazinyl-aryltetrazoles (QPTs) in which the active pharmacophore of piperaquine, a clinically used antimalarial drug, has been combined with tetrazole, a heme-binding moiety. The synthesized compounds (60–72 and 74–87) were evaluated for their anti-plasmodial activity against chloroquine-sensitive (Pf3D7) and chloroquine-resistant (PfINDO) strains of Plasmodium as also for cytotoxicity against mammalian cell lines. Using the obtained data, resistance index (RI) and selectivity index (SI) of the synthesized compounds were calculated. With promising SI as the selection criterion, 8 molecules were picked up for assessing their effect on multidrug-resistant PfCam3.1R539T strain, and on the different cell cycle stages of chloroquine-resistant PfINDO strain of the parasite. On the basis of this study, two compounds (66 and 75) were chosen for determining their kill kinetics against the schizont and rings of PfINDO. Compound 66 showed faster kill kinetics over compound 75. More specifically, 66 at 4 h of treatment was able to prevent schizont egress and subsequent invasion, while 75 had no effect. However, while 66 turned out to be inert against early rings in CQ- and ART-resistant strains, 75 exhibited cidal activity against the early rings of PfCam3.1R539T strain. Interestingly both 66 and 75 caused increase in oxidant levels in the parasite comparable to the levels obtained in ART-treated groups. In combination studies of 66 and 75 with the standard antimalarial drugs, 66 showed synergy with PYR and MFQ and additive effect with ART, while 75 exhibited additive effect with ART and strong antagonistic effect with MFQ. To assess their safety profile, the cytotoxicity of the synthesized compounds against kidney (HEK293) and liver (HUH7) cell lines was also determined. Both 66 and 75 were safe at a dose of 100 mg kg−1 b. wt, at which only 66 was able to suppress the increase in the % parasitemia till day 22 in an in vivo mouse model of malaria. Binding of 66 and 75 with the PfGAP50 protein studied through SPR showed 66 to be a fast associator with a slow rate of dissociation, while reverse was the case with 75. In summary, these studies suggest QPTs (66 and 75) to be interesting from the point of view of their mechanism of action, and as promising leads to offer a new class of antimalarials, which are active against ACT-resistant strains of the Plasmodium and target several proteins of malaria parasite including the PfGAP50 protein.

Experimental section

Chemical work

All the reagents and solvents used for the synthesis of the proposed compounds were purified using standard laboratory techniques. The completion of reactions was monitored by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) on aluminium-supported silica gel 60 GF plates using ultraviolet light (254 nm, short wavelength), iodine vapours or ninhydrin reagent as visualizing media. Uncorrected melting points were determined using a Veego make oil bath-type melting point apparatus by an open glass capillary method and were uncorrected. The purification of compounds was carried out by column chromatography with silica gel (100–200 mesh) or neutral alumina as the stationary phases. A Bruker FT-IR, model ALPHA-T (Germany) spectrophotometer was used for recording the IR spectra by a KBr disc method. 1H-NMR and 13C-NMR spectra were recorded using a Bruker Advance-II 400 MHz spectrometer in CDCl3 or DMSO-d6 with TMS as the internal standard. Multiplicities of the protons are given as singlet (s), doublet (d), doublet of doublet (dd), triplet (t), multiplet (m) and broad singlet (bs), the chemical shift values are indicated in δ ppm and coupling constant (J) in Hz. The purity and composition of the compounds were confirmed by elemental analysis using a Thermo Fisher FLASH 2000 organic elemental analyser and also by HPLC for the two most active compounds (66 and 75). The analysed compounds offered results within ±0.4% of the theoretical values of carbon, hydrogen and nitrogen. Mass spectra were recorded using an ABI MSD Sciex, model API-3000 spectrometer with ESI as an ion source. The HR-MS spectra were recorded using either a TSQ-Altis plus triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher model: Orbitrap) or an Acquity UPLC with a PDA detector + Acquity RDa (Waters).

General procedure for the synthesis of starting materials

The synthesis of 3-/4-substituted/disubstituted aldoximes (15–28) from their respective substituted benzaldehydes (1–14) was carried out using hydroxylamine hydrochloride and sodium acetate trihydrate in methanol under reflux conditions as per the reported procedure.50,51 3-/4-Substituted/disubstituted aldoximes (15–28) were dehydrated using thionyl chloride in dioxane at room temp to afford 3-/4-substituted/disubstituted benzonitriles (29–42), which were confirmed by their respective melting points and IR spectra.52–54

General procedure A: synthesis of 5-(substituted phenyl)-1H-tetrazoles (43–56)

In a 50 ml RBF, 3-/4-substituted/disubstituted benzonitriles (0.5 ml, 0.0048 M), sodium azide (0.93 g, 0.014 M) and ammonium chloride (0.77 g, 0.014 M) were dissolved in dry DMF (5–7 ml). The reaction mixture was heated in an oil bath at 120 °C for 6–8 h. Upon completion of the reaction monitored by TLC, crushed ice was added into the reaction mixture and the medium acidified (pH 2) with dilute HCl. The obtained precipitate was filtered under suction and vacuum-dried offering pure compounds 43–56 as solid crystals.

5-Phenyl-1H-tetrazole (43)

Following general procedure A using benzonitrile (29, 0.5 ml, 0.0048 M), compound 43 was obtained as a white crystal (0.47 g, 95%); m.p. 216–218 °C (215–217 °C);55–58 IR (KBr, cm−1): 3408, 2981, 1652, 1606, 1561, 1484, 1255, 1160, 1055.

5-(3-Nitrophenyl)-1H-tetrazole (44)

Following general procedure A using 3-nitrobenzonitrile compound (30, 0.5 g, 0.0033 M), compound 44 was obtained as a light yellow solid (0.46 g, 92%); m.p. 108–109 °C (lit.55–58 109–110 °C); IR (KBr, cm−1): 3393, 3078, 1626, 1569, 1463, 1349, 1251, 1160, 1086.

5-(4-Nitrophenyl)-1H-tetrazole (45)

Following general procedure A using 4-nitrobenzonitrile compound (31, 0.5 g, 0.0033 M), compound 45 was obtained as a yellow solid (0.46 g, 93%); m.p. 219–221 °C (218–219 °C);55–58 IR (KBr, cm−1): 3445, 1607, 1561, 1531, 1561, 1339, 1285, 1133, 1086, 850.

5-(3-Chlorophenyl)-1H-tetrazole (46)

Following general procedure A using 3-chlorobenzonitrile (32, 0.5 g, 0.0036 M), compound 46 was obtained as an off-white solid (0.43 g, 87%); m.p. 132–135 °C (134.5 °C);55–58 IR (KBr, cm−1): 3444, 2969, 1649, 1559, 1472, 1243, 1157, 1098, 1005.

5-(4-Chlorophenyl)-1H-tetrazole (47)

Following general procedure A using 4-chlorobenzonitrile (33, 0.5 g, 0.0036 M), compound 47 was obtained as an off-white solid (0.44 g, 89%); m.p. 158–160 °C (159.5 °C);55–58 IR (KBr, cm−1): 3431, 3003, 1609, 1566, 1487, 1276, 1161, 1120, 1095.

5-(3-Bromophenyl)-1H-tetrazole (48)

Following general procedure A using 3-bromobenzonitrile (34, 0.5 g, 0.0027 M), compound 48 was obtained as a white solid (0.45 g, 90%); m.p. 144–146 °C (145–146 °C);55–58 IR (KBr, cm−1): 3461, 3065, 1649, 1556, 1471, 1354, 1244, 1156, 1092.

5-(4-Bromophenyl)-1H-tetrazole (49)

Following general procedure A using 4-bromobenzonitrile (35, 0.5 g, 0.0027 M), compound 49 was obtained as an off-white solid (0.44 g, 88%); m.p. >250 °C (260–261 °C);55–58 IR (KBr, cm−1): 3120, 3063, 1605, 1560, 1483, 1276, 1156, 1075, 1014.

5-(3-Fluorophenyl)-1H-tetrazole (50)

Following general procedure A using 3-fluorobenzonitrile (36, 0.5 g, 0.0041 M), compound 50 was obtained as a white solid (0.44 g, 86%); m.p. 137–140 °C (142–144 °C);55–58 IR (KBr, cm−1): 3136, 3058, 1567, 1487, 1311, 1226, 1136, 1081, 948.

5-(4-Fluorophenyl)-1H-tetrazole (51)

Following general procedure A using 4-fluorobenzonitrile (37, 0.5 g, 0.0041 M), compound 51 was obtained as a white solid (0.40 g, 81%); m.p. 182–184 °C (180 °C);55–58 IR (KBr, cm−1): 3148, 3075, 1612, 1504, 1412, 1248, 1164, 1052, 986.

5-(4-Methylphenyl)-1H-tetrazole (52)

Following general procedure A using 4-methylbenzonitrile (38, 0.5 g, 0.0042 M), compound 52 was obtained as a light brown solid (0.43 g, 86%); m.p. 246–248 °C (248 °C);55–58 IR (KBr, cm−1): 3437, 2981, 1615, 1573, 1502, 1436, 1256, 1162, 1053.

5-(4-Isopropylphenyl)-1H-tetrazole (53)

Following general procedure A using 4-isopropylbenzonitrile (39, 0.5 g, 0.0034 M), compound 53 was obtained as a white solid (0.39 g, 79%); m.p. 188-190 °C (191–192 °C);55–58 IR (KBr, cm−1): 3137, 3059, 1614, 1569, 1436, 1252, 1160, 1052, 937, 837.

5-(3-Methoxyphenyl)-1H-tetrazole (54)

Following general procedure A using 3-methoxybenzonitrile (40, 0.5 g, 0.0037 M), compound 54 as a white solid (0.41 g, 83%); m.p. 155–157 °C (156–158 °C);55–58 IR (KBr, cm−1): 3063, 2983, 1564, 1488, 1324, 1250, 1170, 1089, 1049.

5-(3,4-Dimethoxyphenyl)-1H-tetrazole (55)

Following general procedure A using 3,4-dimethoxybenzonitrile (41, 0.5 g, 0.0042 M), compound (55) was obtained as a light brown solid (0.41 g, 82%); m.p. 203–206 °C (206–209 °C);55–58 IR (KBr, cm−1): 3420, 3083, 1610, 1510, 1462, 1274, 1234, 1144, 1022.

5-(4-Methoxyphenyl)-1H-tetrazole (56)

Following general procedure A using 4-methoxybenzonitrile (42, 0.5 g, 0.0037 M), compound (56) was obtained as an off-white solid (0.44 g, 89%); m.p. 228–230 °C (231–232 °C);55–58 IR (KBr, cm−1): 3431, 3078, 1616, 1506, 1445, 1406, 1264, 1182, 1058.

General procedure B. Synthesis of 7-chloro-4-(piperazin-1-yl)quinoline (58)

In a 50 ml RBF, 4,7-dichloroquinoline (57, 1 g, 0.0050 M), anhy. piperazine (1.73 g, 0.020 M) and triethylamine (1.38 ml, 0.013 M) were heated in an oil bath at 110 °C for 11–12 h. Progress of the reaction was monitored by TLC, and after completion, crushed ice and 10% sodium bicarbonate solution were added. The mixture was extracted with ethyl acetate and dried over Na2SO4, and the solvent evaporated using a rotary evaporator offered compound 58 as a yellow solid (0.73 g, 73%); m.p. 119–122 °C (118–120 °C);59 IR (KBr, cm−1): 3254, 2940, 2826, 1568, 1494, 1422, 1372, 1289, 1132, 1069, 1014, 916, 865.

General procedure C. Synthesis of 7-chloro-4-(4-(3-chloropropyl)piperazin-1-yl)-quinoline (59)

In a 25 ml two-necked RBF, sodium hydride (0.072 g, 0.0060 M) washed with dry pet ether and anhydrous DMSO (3 ml) were added followed by the addition of compound 58 (0.5 g, 0.0020 M) and the mixture was stirred for 10 min under a stream of nitrogen. 1-Bromo-3-chloropropane (0.95 g or 0.59 ml, 0.0060 M) was added drop-wise and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight. After completion of the reaction as indicated on TLC, crushed ice was slowly added and the slurry was extracted with ethyl acetate and dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. The solvent was evaporated using a rotary evaporator offering a brown liquid, which on recrystallization using n-hexane and chloroform offered compound (59) as a brown solid (0.34 g, 68%); m.p. 84–86 °C (84 °C);60 IR (KBr, cm−1): 2999, 2917, 1610, 1573, 1497, 1431, 1380, 1305, 1260, 1124, 1024, 953 and 828.

General procedure D. Synthesis of 7-chloro-4-(4-(3-(5-(substituted phenyl)-2H-tetrazol-1-yl)propyl)piperazin-1-yl)quinolines (60–72)

In a 25 ml 2-necked RBF, 5-(substituted phenyl)-1H-tetrazole (43–56; 0.0018 M) was dissolved in dry DMF (3 ml) and K2CO3 (0.24 g, 0.2448 M) was suspended into this solution. After stirring at room temperature for 5–10 min under a stream of nitrogen, compound 59 (0.30 g, 0.0009 M) was added and the reaction mixture was heated on an oil bath at 80 °C for 7–8 h. Progress of the reaction was monitored by TLC and after completion of the reaction, crushed ice was added to it and extracted with ethyl acetate and dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. The solvent was evaporated with the aid of rotary evaporator and the obtained sticky material was purified by column chromatography using pet ether and ethyl acetate (70%) as eluents to offer the desired compounds (60–72) as semisolid masses.

7-Chloro-4-(4-(3-((5-phenyl)-2H-tetrazol-2-yl)propyl)piperazin-1-yl)quinoline (60)

Following general procedure D, by reacting 5-phenyl-1H-tetrazole (43, 0.0009 M) with compound 59 (0.30 g, 0.0009 M), compound 60 was obtained as a semisolid material (0.18 g, 62%); IR (KBr, cm−1): 3043, 2948, 1675, 1571, 1496, 1456, 1379, 1259, 1138, 1016, 926, 873 and 826; 1H-NMR (CDCl3): δ 8.70–8.69 (d, 1H, J = 4 Hz), 8.16–8.14 (m, 2H), 8.04–803 (d, 1H, J = 1.8 Hz), 7.92–7.90 (d, 1H, J = 6.8 Hz), 7.51–7.45 (m, 3H), 7.41–7.39 (dd, 1Hb, J = 6.8 & 1.8 Hz), 6.79–6.78 (d, 1H), 4.80–4.78 (t, 2H, J = 5.6 Hz), 3.21–3.19 (bs, 4H), 2.73–2.71 (bs, 4H), 2.59–2.56 (t, 2H, J = 5.4 Hz) and 2.32–2.27 (m, 2H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3): δ 162.5, 158.7, 152.1, 149.6, 135.2, 130.8, 129.5, 128.6, 127.9, 126.9, 126.5, 125.8, 125.1, 118.2, 52.4, 51.1, 50.2, 50.9 and 24.9; anal. calculated for C23H24N7Cl: C, 63.66; H, 5.57; N, 22.59. Found: C, 63.31; H, 5.89; N, 22.21%; MS (m/z): 434.40 (M+) and 436.20 (M + 2)+.

7-Chloro-4-(4-(3-(5-(3-nitrophenyl)-2H-tetrazol-2-yl)propyl)piperazin-1-yl)quinoline (61)

Following general procedure D, by reacting 5-(3-nitrophenyl)-1H-tetrazole (44, 0.34 g, 0.0018 M) with compound 59 (0.30 g, 0.0009 M), compound 61 was obtained as a semisolid (0.19 g, 61%); IR (KBr, cm−1): 3079, 2947, 2826, 1675, 1573, 1514, 1454, 1428, 1351, 1263, 1142, 1015, 924, 874, 821, and 724; 1H-NMR (CDCl3): δ 9.03–9.02 (t, 1H, J = 2.0 Hz), 8.74–8.72 (d, 1H, J = 5.2 Hz), 8.54–8.52 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz), 8.36–8.34 (d, 1H, J = 8.1 Hz), 8.08–8.07 (d, 1H, J = 2.4 Hz), 7.95–7.93 (d, 1H, J = 9.2 Hz), 7.74–7.70 (t, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.45–7.42 (dd, 1H, J = 2.2 Hz, 9.0 Hz), 6.84–6.83 (d, 1H, J = 5.2 Hz), 4.87–4.84 (t, 2H, J = 7.0 Hz), 3.27–3.24 (bs, 4H, J = 5.0 Hz), 2.78–2.76 (bs, 4H, J = 4.8 Hz), 2.64–2.61 (t, 2H, J = 6.6 Hz), and 2.39–2.32 (m, 2H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3): δ 162.9, 159.1, 152.6, 149.6, 148.5, 135.3, 130.8, 130.5, 129.2, 127.9, 126.9, 126.5, 125.7, 122.3, 118.2, 52.6, 52.1, 51.2, 50.9 and 24.3; HR-MS (ESI) (m/z): calcd for C23H24ClN8O2, 479.1710; found, 479.1699 [M + H]+; anal. calculated for C23H23N8O2Cl: C, 57.68; H, 4.84; N, 23.40. Found: C, 57.32; H, 5.17; N, 23.16%.

7-Chloro-4-(4-(3-(5-(4-nitrophenyl)-2H-tetrazol-2-yl)propyl)piperazin-1-yl)quinoline (62)

Following general procedure D, by reacting 5-(4-nitrophenyl)-1H-tetrazole (45, 0.34 g, 0.0018 M) with compound 59 (0.30 g, 0.0009 M), compound (62) was obtained as a semisolid (0.19 g, 65%); IR (KBr, cm−1): 3053, 2932, 1677, 1573, 1525, 1457, 1346, 1262, 1139, 1072, 1014, 928, 869 and 737; 1H-NMR (CDCl3): δ 8.75–8.74 (d, 1H, J = 5.2 Hz), 8.43–8.37 (m, 4H), 8.14–8.13 (d, 1H, J = 2.3 Hz), 7.97–7.95 (d, 1H, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.48–7.45 (dd, 1H, J = 8.8 & 2.3 Hz), 6.87–6.86 (d, 1H), 4.90–4.87 (t, 2H, J = 6.8 Hz), 3.33–3.30 (bs, 4H), 2.82–2.80 (bs, 4H), 2.68–2.66 (t, 2H, J = 6.8 Hz) and 2.42–2.35 (m, 2H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3): δ 162.3, 159.6, 152.3, 149.2, 148.2, 135.0, 130.1, 130.6, 129.8, 127.9, 126.1, 125.2, 121.3, 118.2, 52.5, 51.6, 51.2, 50.7 and 24.8; anal. calculated for C23H23N8O2Cl: C, 57.68; H, 4.84; N, 23.40. Found: C, 57.33; H, 5.24; N, 23.32%; MS (m/z): 479.10 (M+) and 481.20 (M + 2)+.

7-Chloro-4-(4-(3-(5-(3-chlorophenyl)-2H-tetrazol-2-yl)propyl)piperazin-1-yl)quinoline (63)

Following general procedure D, by reacting 5-(3-chlorophenyl)-1H-tetrazole (46, 0.32 g, 0.0018 M) with compound 59 (0.30 g, 0.0009 M), compound 63 was obtained as a semisolid (0.18 g, 67%); IR (KBr, cm−1): 2951, 2828, 1674, 1573, 1497, 1429, 1381, 1265, 1139, 1016, 875, 826 793 and 741; 1H-NMR: δ 8.75–8.72 (d, 1H, J = 4.8 Hz), 8.20–8.17 (m, 1H), 8.08–8.05 (m, 2H), 7.95–7.93 (d, 1H, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.48–7.42 (m, 3H), 6.82–6.81 (d, 1H, J = 5.2 Hz), 4.84–4.80(t, 2H, J = 7.2 Hz), 3.24–3.22 (bs, 4H, J = 4.8 Hz), 2.76–2.74 (bs, 4H, J = 4.8 Hz), 2.62–2.58 (t, 2H, J = 6.6 Hz), and 2.35–2.29 (m, 2H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3): δ 163.3, 159.2, 151.9, 149.5, 135.2, 134.8, 134.2, 133.1, 130.3, 129.8, 127.9, 127.2, 126.2, 125.5, 121.1, 118.5, 52.2, 51.5, 51.3, 50.3 and 24.2; anal. calculated for C23H23N7Cl: C, 58.98; H, 4.95; N, 20.93. Found: C, 58.65; H, 5.34; N, 20.68%.

7-Chloro-4-(4-(3-(5-(4-chlorophenyl)-2H-tetrazol-2-yl)propyl)piperazin-1-yl)quinoline (64)

Following general procedure D, by reacting 5-(4-chlorophenyl)-1H-tetrazole (47, 0.32 g, 0.0018 M) with compound 59 (0.30 g, 0.0009 M), compound 64 was obtained as a semisolid (0.18 g, 67%); IR (KBr, cm−1): 2951, 1667, 1611, 1564, 1454, 1384, 1253, 1222, 1095, 1060, 1010, 867, 840 and 757; 1H-NMR (CDCl3): δ 9.01–8.99 (d, 1H, J = 7.2 Hz), 8.11–8.09 (d, 2H, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.99–7.97 (d, 1H, J = 9.2 Hz),7.90–7.89 (d, 1H, J = 2.0 Hz), 7.50–7.48 (d, 2H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.39–7.37 (dd, 1H, J = 2.8 Hz, 7.6 Hz), 6.86–6.85 (d, 1H, J = 5.2 Hz), 4.82–4.79 (t, 2H, J = 6.6 Hz), 3.35–3.34 (bs, 4H, J = 4.4 Hz), 2.81–2.78 (bs, 4H, J = 5.8 Hz), 2.62–2.59 (t, 2H, J = 6.6 Hz), and 2.35–2.29 (m, 2H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3): δ 163.5, 159.3, 152.1, 149.5, 135.6, 134.5, 132.9, 131.2, 129.1, 128.9, 127.8, 126.9, 125.9, 118.3, 52.1, 51.6, 51.2, 50.3 and 24.6; anal. calculated for C23H23N7Cl: C, 58.98; H, 4.95; N, 20.93. Found: C, 58.73; H, 5.27; N, 20.62%.

7-Chloro-4-(4-(3-(5-(3-bromophenyl)-2H-tetrazol-2-yl)propyl)piperazin-1-yl)quinoline (65)

Following general procedure D, by reacting 5-(3-bromophenyl)-1H-tetrazole (48, 0.40 g, 0.0018 M) with compound 59 (0.30 g, 0.0009 M), compound 65 was obtained as a semisolid (0.18 g, 65%); IR (KBr, cm−1): 3053, 2951, 2825, 1677, 1572, 1496, 1457, 1428, 1378, 1264, 1139, 1071, 1016, 926, 874, 825 and 741; 1H-NMR (CDCl3): δ 8.74–8.73 (d, 1H, J = 4.8 Hz), 8.34–8.33 (t, 1H, J = 1.8 Hz), 8.13–8.06 (m, 2H), 7.95–7.93 (d, 1H, J = 9.2 Hz), 7.64–7.60 (m, 1H), 7.45–7.37 (m, 2H),6.83–6.81 (d, 1H, J = 4.8 Hz), 4.83–4.80 (t, 2H, J = 6.8 Hz), 3.24–3.22 (bs,4H, J = 4.8 Hz), 2.76–2.74 (bs, 4H, J = 4.6 Hz), 2.62–2.59 (t, 3H, J = 6.6 Hz), and 2.36–2.29 (m, 2H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3): δ 163.4, 159.1, 149.5, 136.1, 135.8, 135.2, 134.9, 133.1, 132.8, 130.1, 128.2, 127.1, 126.5, 125.1, 118.4, 52.3, 51.1, 51.0, 50.1 and 24.4; anal. calculated for C23H23N7BrCl: C, 53.87; H, 4.52; N, 19.12. Found: C, 53.56; H, 4.86; N, 18.78%.

7-Chloro-4-(4-(3-(5-(4-bromophenyl)-2H-tetrazol-2-yl)propyl)piperazin-1-yl)quinoline (66)

Following general procedure D, by reacting 5-(4-bromophenyl)-1H-tetrazole (49, 0.40 g, 0.0018 M) with compound 59 (0.30 g, 0.0009 M), compound 66 was obtained as a semisolid (0.18 g, 60%); IR (KBr, cm−1): 3055, 2949, 2828, 1680, 1573, 1456, 1424, 1377, 1264, 1137, 1071, 1011, 930, 873 and 830; 1H-NMR (CDCl3): δ 8.69–8.68 (d, 1H), 8.02–7.97 (m, 4H), 7.79–7.76 (d, 2H), 7.56–7.53 9dd, 1H), 6.94–6.93 (d, 1H), 4.83 (t, 2H), 3.15 (bs, 4H), 2.63 (bs, 4H), 2.47 (bs, 2H), and 2.23–2.17 (m, 2H); 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 163.20, 156.25, 152.15, 149.61, 133.54, 132.35, 128.28, 128.06, 126.27, 126.01, 125.74, 123.89, 121.37, 54.35, 52.43, 51.72, 51.36, 25.87. RP-HPLC: purity = 99.47%, tR = 13.48; HR-MS (ESI) (m/z): calcd for C23H24BrClN7, 512.0965; found, 512.0940 [M + H]+; UPLC-MS: m/z 512.30 (M+) and 514.30 (M + 2)+. Anal. calculated for C23H23N7BrCl: C, 53.87; H, 4.52; N, 19.12. Found: C, 53.53; H, 4.91; N, 18.93%.

7-Chloro-4-(4-(3-(5-(3-fluorophenyl)-2H-tetrazol-2-yl)propyl)piperazin-1-yl)quinoline (67)

Following general procedure D, by reacting 5-(3-fluorophenyl)-1H-tetrazole (50, 0.29 g, 0.0018 M) with compound 59 (0.30 g, 0.0009 M), compound 67 was obtained as a semisolid mass (0.18 g, 62%); IR (KBr, cm−1): 3068, 2929, 1672, 1593, 1460, 1382, 1262, 1224, 1094, 875, 820, 801, 755 and 684; 1H-NMR(CDCl3): δ 8.45–8.43 (d, 1H, J = 8.4 Hz), 8.04–7.90 (m, 3H), 7.67–7.65 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.52–7.49 (m, 1H), 7.42–7.37 (m, 1H), 7.23–7.20 (m, 1H), 6.38–6.36 (d, 1H, J = 7.6 Hz), 4.82–4.79 (t, 2H, J = 6.0 Hz), 3.32–3.29 (bs, 4H, J = 5.0 Hz), 2.81–2.77 (bs, 4H, J = 5.2 Hz), 2.69–2.66 (t, 2H), and 2.36–2.25 (m, 2H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3): δ 163.7, 163.4, 159.2, 149.5, 135.4, 133.0, 131.8, 130.6, 129.8, 129.5, 128.5, 127.6, 127.4, 126.2, 125.3, 118.1, 52.5, 51.3, 51.0, 50.5 and 24.5; HR-MS (ESI) (m/z): calcd for C23H24ClFN7, 452.1765; found, 452.1751 [M + H]+; anal. calculated for C23H23N7ClF: C, 61.13; H, 5.13; N, 21.70. Found: C, 60.82; H, 5.37; N, 21.45%.

7-Chloro-4-(4-(3-(5-(4-fluorophenyl)-2H-tetrazol-2-yl)propyl)piperazin-1-yl)quinoline (68)

Following general procedure D, by reacting 5-(4-fluorophenyl)-1H-tetrazole (51, 0.29 g, 0.0018 M) with compound 59 (0.30 g, 0.0009 M), compound (68) was obtained as a semisolid mass (0.18 g, 62%); IR (KBr, cm−1): 2946, 2827, 1607, 1573, 1460, 1427, 1379, 1298, 1230, 1136, 1013, 928 and 872; 1H-NMR (CDCl3): δ 8.75–8.73 (d, 1H, J = 5.2 Hz), 8.24–8.16 (m, 2H), 8.10–8.09 (d, 1H, J = 2.4 Hz), 7.97–7.94 (d, 1H, J = 9 Hz), 7.47–7.44 (dd, 1H, J = 9 and 2.4 Hz), 7.24–7.18 (m, 2H), 6.85–6.84 (d, 1H, J = 5.2 Hz), 4.84–4.81 (t, 2H, J = 6.8 Hz), 3.28–3.26 (bs, 4H), 2.79–2.76 (bs, 4H), 2.64–2.61 (t, 2H, J = 6.8 Hz) and 2.37–2.31 (m, 2H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3): δ 163.4, 163.0, 159.3, 149.7, 135.3, 133.2, 130.4, 129.6, 129.4, 128.9, 127.4, 118.2, 117.6, 117.2, 52.4, 51.1, 49.9, 49.1 and 24.3; anal. calculated for C23H23N7ClF: C, 61.13; H, 5.13; N, 21.70. Found: C, 60.83; H, 5.48; N, 21.33%; MS (m/z): 452.00 (M+) and 454.10 (M + 2)+.

7-Chloro-4-(4-(3-(5-(4-methylphenyl)-2H-tetrazol-2-yl)propyl)piperazin-1-yl)quinoline (69)

Following general procedure D, by reacting 5-(4-methylphenyl)-1H-tetrazole (52, 0.28 g, 0.0018 M) with compound 59 (0.30 g, 0.0009 M), compound 69 was obtained as a semisolid mass (0.18 g, 63%); IR (KBr, cm−1): 3046, 2949, 1675, 1573, 1460, 1379, 1264, 1138, 1015, 928, 873 and 827; 1H-NMR (CDCl3): δ 8.74–8.73 (d, 1H, J = 5 Hz), 8.13–8.06 (m, 3H), 7.97–7.94 (d, 1H, J = 9 Hz), 7.48–7.45 (dd, 1H, J = 9 & 2 Hz), 7.35–7.33 (d, 2H), 6.85–6.84 (d, 1H, J = 5 Hz), 4.84–4.81 (t, 2H, J = 6.8 Hz), 3.35–3.29 (bs, 4H), 2.80–2.78 (bs, 4H), 2.66–2.63 (t, 2H, J = 6.8 Hz), 2.46 (s, 3H) and 2.39–2.32 (m, 2H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3): δ 157.21, 151.20, 140.54, 135.38, 129.66, 128.31, 126.74, 126.37, 126.20, 125.25, 124.69, 121.80, 121.78, 108.84, 54.87, 52.93, 52.05, 51.30, 26.46 and 21.51; anal. calculated for C24H26N7Cl: C, 64.35; H, 5.85; N, 21.89. Found: C, 63.96; H, 6.23; N, 21.62%; MS (m/z): 448.20 (M+) and 450.20 (M + 2)+.

7-Chloro-4-(4-(3-(5-(4-isopropylphenyl)-2H-tetrazol-2-yl)propyl)piperazin-1-yl)quinoline (70)

Following general procedure D, by reacting 5-(4-isopropylphenyl)-1H-tetrazole (53, 0.33 gm, 0.0018 M) with compound 59 (0.30 g, 0.0009 M), compound 70 was obtained as a semisolid mass (0.19 g, 64%); IR (KBr, cm−1): 3050, 2959, 1631, 1580, 1462, 1427, 1379, 1265, 1227, 1140, 1017, 929, 872 and 789; 1H-NMR (CDCl3): δ 8.70–8.68 (d, 1H, J = 5.2 Hz), 8.09–8.07 (d, 2H), 7.93–7.92 (d, 1H), 7.64–7.62 (d, 1H), 7.40–7.33 (m, 3H), 6.80–6.78 (d, 1H, J = 5.2 Hz), 4.78–4.75 (t, 2H), 3.22–3.20 (bs, 4H), 3.02–2.94 (m, 1H), 2.74–2.71 (d, 4H), 2.59–2.55 (t, 2H), 2.33–2.26 (m, 2H) and 1.30–1.29 (d, 6H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3): δ 149.35, 141.05, 126.83, 126.29, 124.70, 124.58, 124.56, 124.40, 123.75, 122.76, 122.16, 112.32, 108.74, 106.54, 52.40, 50.53, 49.68, 48.86, 47.19, 31.69, 25.56 and 21.39; anal. calculated for C26H30N7Cl: C, 65.60; H, 6.35; N, 20.60. Found: C, 65.35; H, 6.59; N, 20.29%; MS (m/z): 476.20 (M+) and 478.20 (M + 2)+.

7-Chloro-4-(4-(3-(5-(3-methoxyphenyl)-2H-tetrazol-2-yl)propyl)piperazin-1-yl)quinoline (71)

Following General procedure D, by reacting 5-(3-methoxyphenyl)-1H-tetrazole (54, 0.32 g, 0.0018 M) with compound 59 (0.30 g, 0.0009 M), compound 71 was obtained as a semisolid (0.19 g, 65%); IR (KBr, cm−1): 3054, 2959, 2834, 1581, 1466, 1429, 1379, 1265, 1136, 1040, 869, 822, and 740; 1H-NMR (CDCl3): δ 8.73–8.72 (d, 1H, J = 5.2 Hz), 8.08–8.07 (d, 1H, J = 2 Hz), 7.95–7.93 (d, 1H, J = 7.2 Hz), 7.72–7.71 (d, 2H, J = 1.6 Hz), 7.40–7.37 (dd, 1H, J = 3.4 Hz, 7 Hz), 7.04–7.02 (m, 2H), 6.83–6.82 (d, 1H, J = 4.8 Hz), 4.83–4.80 (t, 2H, J = 6.6 Hz), 3.91 (s, 3H), 3.26–3.24 (bs, 4H, J = 5 Hz), 2.76–2.74 (bs, 4H, J = 4.8 Hz), 2.62–2.59 (t, 2H, J = 6.6 Hz), and 2.36–2.29 (m, 2H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3): δ 163.5, 161.1, 159.6, 149.5, 135.4, 132.5, 130.4, 130.6, 130.1, 129.4, 128.7, 127.6, 119.2, 118.4, 115.6, 112.0, 55.7, 52.3, 51.0, 49.8, 49.5 and 24.5; HR-MS (ESI) (m/z): calcd for C24H27ClN7O, 464.1965; found, 464.1964 [M + H]+; anal. calculated for C24H26N7OCl: C, 62.13; H, 5.65; N, 21.13. Found: C, 61.84; H, 6.01; N, 20.84%.

7-Chloro-4-(4-(3-(5-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-2H-tetrazol-2-yl)propyl)piperazin-1-yl)quinoline (72)

Following General procedure D, by reacting 5-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-1H-tetrazole (55, 0.37 g, 0.0018 M) with compound 59 (0.30 g, 0.0009 M), compound 72 was obtained as a semisolid mass (0.17 g, 59%); IR (KBr, cm−1): 2929, 2833, 1604, 1573, 1487, 1430, 1300, 1262, 1234, 1186, 1137, 1073, 1023, 928, 873 and 789; 1H-NMR (CDCl3): δ 8.75–8.74 (d, 1H, J = 5.2 Hz), 8.10–8.10 (d, 1H, J = 2.2 Hz), 7.98–7.95 (d, 1H, J = 8.6 Hz), 7.80–7.77 (dd, 1H, J = 8.6 & 2.2 Hz), 7.71–7.71 (d, 1H, J = 2 Hz), 7.47–7.44 (dd, 1H, J = 8.8 and 2 Hz), 7.03–7.08 (d, 1H, J = 8.8 Hz), 6.86–6.84 (d, 1H, J = 5.2 Hz), 4.83–4.80 (t, 2H, J = 7 Hz), 4.02 (s, 3H), 3.99 (s, 3H), 3.31–3.25 (bs, 4H), 2.80–2.77 (bs, 4H), 2.65–2.61 (t, 2H, J = 6.8 Hz) and 2.39–2.32 (m, 2H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3): δ 157.13, 151.56, 150.86, 149.75, 135.19, 129.33, 128.56, 126.28, 125.22, 121.82, 120.23, 117.36, 112.76, 111.33, 109.66, 108.93, 56.11, 54.86, 53.03, 52.97, 52.10, 51.78, 51.32, 29.72 and 26.55; anal. calculated for C25H28N7O2Cl: C, 60.78; H, 5.71; N, 19.85. Found: C, 60.57; H, 6.04; N, 19.66%; MS (m/z): 494.20 (M+) and 496.00 (M + 2)+.

General procedure E. Synthesis of 2-chloro-1-(4-(7-chloroquinolin-4-yl)piperazin-1-yl) ethanone (73)

In a 100 ml single-necked RBF, compound 58 (1 g, 0.004 M) was dissolved in 3 ml of dry DCM followed by the addition of anhydrous triethyl amine (0.8 ml, 0.008 M). After stirring the reaction mixture at 0 °C, chloroacetyl chloride (0.8 ml, 0.008 M) in 3 ml dry DCM was added drop-wise into the reaction mixture using a dropping funnel. After the addition, the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 3–4 h. After completion of the reaction, crushed ice was added, and the mixture was extracted with chloroform and dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. The solvent was removed using a rotary evaporator and the obtained sticky material was purified by column chromatography using pet ether and ethyl acetate (60%) as eluents to offer the desired yellow colored liquid compound (90%); IR:3437, 3053, 2924, 1659, 1430, 1383, 1270, 1015, 869, 830, 741; anal. calculated for C15H15N3OCl2: C, 55.57; H, 4.66; N, 12.96; found: C, 55.18; H, 5. 02; N, 12.78%.

General procedure F. Synthesis of 1-(4-(7-chloroquinolin-4-yl)piperazin-1-yl)-2-(5-(substituted phenyl)-2H-tetrazol-2-yl)ethanones (74–87)

In a 25 ml 2-necked RBF, 5-(substituted phenyl)-1H-tetrazole (43–56; 0.27 g, 0.0018 M) was dissolved in dry DMF and K2CO3 (0.24 g, 0.0017 M) was added. After stirring at room temperature for 5–10 min under the stream of nitrogen, compound 73 (0.30 g, 0.0009 M) was added and the reaction mixture was stirred in an oil bath at 80 °C for 7–8 h. The progress of the reaction was monitored by TLC. After completion of the reaction, crushed ice was added, and the mixture was extracted with ethyl acetate and dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. The solvent was evaporated using a rotary evaporator and the obtained sticky material was purified by column chromatography using 60% pet ether in ethyl acetate as the eluent to offer the desired compounds (74–87).

1-(4-(7-Chloroquinolin-4-yl)piperazin-1-yl)-2-(5-phenyl-2H-tetrazol-2-yl)ethanone (74)

Following general procedure F, by reacting 5-phenyl-1H-tetrazole (43, 0.32 g, 0.0018 M) with compound 73 (0.30 g, 0.0009 M), compound (74) was obtained as a semisolid mass (62%); IR (KBr, cm−1): 2925, 2856, 1676, 1606, 1572, 1460, 1382, 1239, 1094, 1016, 872, 828, 734, 695; 1H-NMR (CDCl3): δ 8.80–8.78 (d, 1H, J = 5.2 Hz), 8.20–8.17 (, 2H), 8.13–8.12 (d, 1H, J = 2.4 Hz, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.98–7.96 (d, 1H, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.52–7.49 (m, 4H), 6.90–6.88 (d, 1H, J = 5.2 Hz), 5.66 (s, 2H), 3.33–3.27 (d, 4H), and 2.97–2.90 (d, 4H); 13C-NMR (CDCl3): δ 168.9, 163.4, 159.1, 151.5, 150.2, 135.6, 131.2, 130.5, 129.2, 127.1, 126.8, 126.5, 126.1, 125.2, 118.5, 51.0, 49.8 and 46.5; anal. calculated for C22H20N7OCl: C, 60.90; H, 4.65; N, 22.60. Found: C, 60.57; H, 5.03; N, 22. 42%; MS (m/z):434.36 (M + 1)+.

1-(4-(7-Chloroquinolin-4-yl)piperazin-1-yl)-2-(5-(3-nitrophenyl)-2H-tetrazol-2-yl)ethanone (75)

Following General procedure F, by reacting 5-(3-nitrophenyl)-1H-tetrazole (44, 0.37 g, 0.0018 M) with compound 73 (0.30 g, 0.0009 M), compound 75 was obtained as a semisolid (61%); IR (KBr, cm−1): 2925, 2857, 1670, 1610, 1574, 1542, 1515, 1453, 1423, 1382, 1351, 1270, 1239, 1130, 1093, 1045, 1015, 871, 826, and 736; 1H-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 8.78–8.77 (s, 1H,), 8.76–8.75 (d, 1H, J = 5.2 Hz), 8.51–8.49 (d, 1H, J = 7.6 Hz), 8.42–8.8.39 (dd, 1H, J = 2 Hz & 8.4 Hz), 8.14–8.12 (d, 1H, J = 8.8 Hz), 8.01 (d, 1H, J = 2 Hz), 7.92–7.88 (m, 1H), 7.60–7.58 (dd, 1H, J = 2 Hz & 8.8 Hz), 7.07–7.06 (d, 1H, 5.2 Hz), 6.16 (s, 2H), 3.85–3.83 (bs, 2H), 3.80–3.78 (bs, 2H), 3.33–3.31 (bs, 2H), 3.23–3.20 (bs, 2H); 13C-NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 163.29, 162.45, 155.94, 152.29, 149.65, 148.37, 133.72, 132.40, 131.34, 128.25, 128.14, 126.10, 126.01, 125.22, 109.85, 54.40, 51.46, 44.38 and 41.68. RP-HPLC: purity = 99.31%, tR = 8.80; HR-MS (ESI) (m/z): calcd for C22H20ClN8O3, 479.1346; found, 479.1327 [M + H]+; UPLC-MS: m/z 479.30 (M + 1); anal. calculated for C22H19N8O3Cl: C, 55.18; H, 4.00; N, 23.40. Found: C, 54.89; H, 4.36; N, 23.27%.

1-(4-(7-Chloroquinolin-4-yl)piperazin-1-yl)-2-(5-(4-nitrophenyl)-2H-tetrazol-2-yl)ethanone (76)

Following general procedure F, by reacting 5-(4-nitrophenyl)-1H-tetrazole (45, 0.37 g, 0.0018 M) with compound 73 (0.30 g, 0.0009 M), compound (76) was obtained as a semisolid (65%); IR (KBr, cm−1): 3056, 2923, 2849, 1671, 1607, 1574, 1523, 1457, 1422, 1379, 1341, 1267, 1238, 1158, 1042, 1013, 862, 827, and 738; 1H-NMR: δ 8.78–8.76 (d, 1H, J = 5.2 Hz), 8.46–8.44 (dd, 2H, J = 2.2 Hz, 7.0 Hz), 8.38–8.34 (d, 2H, J = 8.9 Hz), 8.16–8.14 (d, 1H, 8.8 Hz), 8.04–8.03 (d, 1H, J = 2.0 Hz), 7.62–7.60 (dd, 1H, J = 2.2 Hz, 9.0 Hz), 7.09–7.08 (d, 1H, J = 5.2 Hz), 6.17 (s, 2H), 3.37–3.34 (d, 4H), and 3.27–3.24 (s, 4H, J = 5.2 Hz); anal. calculated for C22H19N8O3Cl: C, 55.18; H, 4.00; N, 23.40. Found: C, 54.82; H, 4.37; N, 23.13%.

1-(4-(7-Chloroquinolin-4-yl)piperazin-1-yl)-2-(5-(3-chlorophenyl)-2H-tetrazol-2-yl)ethanone (77)

Following general procedure F, by reacting 5-(3-chlorophenyl)-1H-tetrazole (46, 0.33 g, 0.0018 M) with compound 73 (0.30 g, 0.0009 M), compound 77 was obtained as a semisolid (59%); IR (KBr, cm−1): 3058, 2925, 2856, 1669, 1605, 1512, 1445, 1379, 1266, 1236, 1080, 1045, 1016, and 742; 1H-NMR: δ 8.73–8.72 (d, 1H, J = 4.0, Hz), 8.13–8.11 (d, 1H J = 7.2 Hz), 8.02–7.97 (m, 3H), 7.63–7.57 (m, 3H), 7.06–7.05 (d, 1H, J = 4.0 Hz), 6.08 (s, 2H), 3.83–3.73 (m, 4H), and 3.51–3.42 (t, 4H); anal. calculated for C22H19N7OCl2: C, 56.42; H, 4.09; N, 20.94. Found: C, 56.15; H, 4.47; N, 20.63%.

1-(4-(7-Chloroquinolin-4-yl)piperazin-1-yl)-2-(5-(4-chlorophenyl)-2H-tetrazol-2-yl)ethanone (78)

Following general procedure F, by reacting 5-(4-chlorophenyl)-1H-tetrazole (47, 0.33 g, 0.0018 M) with compound 73 (0.30 g, 0.0009 M), compound (78) was obtained as a semisolid (65%); IR (KBr, cm−1): 2925, 2854, 1672, 1609, 1579, 1450, 1384, 1268, 1151, 1094, 1041, 1014, 871, 835, and 739; 1H-NMR: δ 8.77–8.76 (s, 1H, J = 5.2 Hz), 8.06–8.02 (d, 3H, J = 2 Hz, 12.4 Hz), 7.72–7.71 (s, 3H, J = 2.2 Hz), 7.64–7.61 (dd, 1H, J = 2.2 Hz, 9.0 Hz), 7.11–7.10 (d, 1H, J = 5.6 Hz), 6.10 (s, 2H), 3.45 (s, 4H), and 3.35 (s, 4H); anal. calculated for C22H19N7OCl2: C, 56.42; H, 4.09; N, 20.94. Found: C, 56.25; H, 4.38; N, 20.71%; MS (m/z): 468.60 (M)+.

1-(4-(7-Chloroquinolin-4-yl)piperazin-1-yl)-2-(5-(3-bromophenyl)-2H-tetrazol-2-yl)ethanone (79)

Following general procedure F, by reacting 5-(3-bromophenyl)-1H-tetrazole (48, 0.41 g, 0.0018 M) with compound 73 (0.30 g, 0.0009 M), compound 79 was obtained as a semisolid (59%); IR (KBr, cm−1): 3057, 2924, 2854, 1672, 1608, 1574, 1503, 1454, 1382, 1266, 1238, 1127, 1093, 1044, 1014, 871, 829, and 740; 1H-NMR (CDCl3): δ 8.84–8.82 (d, 1H, J = 4.8 Hz), 8.37–8.33 (d, 1H, J = 12.4 Hz), 8.18–8.10 (m, 2H), 8.01–7.99 (d, 1H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.67–7.64 (m, 1H), 7.57–7.54 (dd, 1H, J = 2 Hz, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.44–7.39 (t, 1H, J = 11.4 Hz), 6.96–6.95 (d, 1H, J = 5.2 Hz), 5.70 (s, 2H), 3.42–3.37 (d, 4H), and 3.03–2.96 (d, 4H, J = 1 Hz); anal. calculated for C22H19N7OBrCl: C, 51.53; H, 3.73; N, 19.12. Found: C, 51.26; H, 4.06; N, 18.85%; MS (m/z): 512.60 (M)+ and 514.60 (M + 2)+.

1-(4-(7-Chloroquinolin-4-yl)piperazin-1-yl)-2-(5-(4-bromophenyl)-2H-tetrazol-2-yl)ethanone (80)

Following general procedure F, by reacting 5-(4-bromophenyl)-1H-tetrazole (49, 0.41 g, 0.0018 M) with compound 73 (0.30 g, 0.0009 M), compound (80) was obtained as a semisolid (60%); IR (KBr, cm−1): 2925, 2855, 1670, 1505, 1450, 1384, 1266, 1204, 1140, 1014, 833, 804, and 742; 1H-NMR: δ 8.77–8.76 (d, 1H, J = 4.8 Hz), 8.16–8.14 (d, 1H, J = 9.2 Hz), 8.04–8.02 (d, 2H, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.96 (s, 1H), 7.82–7.80 (d, 2H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.62–7.60 (dd, 1H, J = 2.2 Hz, 9.0 Hz), 7.09–7.07 (d, 1H, J = 5.2 Hz), 6.10 (s, 2H), 3.25 (s, 4H), and 2.90 (s, 4H); anal. calculated for C22H19N7OBrCl: C, 51.53; H, 3.73; N, 19.12. Found: C, 51.27; H, 4.06; N, 18.84%.

1-(4-(7-Chloroquinolin-4-yl)piperazin-1-yl)-2-(5-(3-fluorophenyl)-2H-tetrazol-2-yl)ethanone (81)

Following general procedure F, by reacting 5-(4-fluorophenyl)-1H-tetrazole (50, 0.30 g, 0.0018 M) with compound 73 (0.30 g, 0.0009 M), compound 81 was obtained as a semisolid mass (67%); IR (KBr, cm−1): 3064, 2924, 2851, 1671, 1576, 1529, 1462, 1422, 1382, 1271, 1237, 1125, 1094, 1043, 1014, 875, 827, and 737; 1H-NMR: δ 8.73 (s, 1H), 8.12–8.10 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz), 8.00–7.99 (d, 1H, J = 4.0 Hz), 7.93–7.90 (t, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.80–7.79 (d, 1H, J = 4.0 Hz), 7.65–7.56 (m, 2H), 7.42–7.38 (m, 1H), and 7.05–7.04 (d, 1H, J = 4.0 Hz) 6.09 (s, 2H), 3.82–3.75 (m, 4H), and 3.35 (s, 4H); anal. calculated for C22H19N7OClF: C, 58.47; H, 4.24; N, 21.70. Found: C, 58.16; H, 4.53; N, 21.44%.

1-(4-(7-Chloroquinolin-4-yl)piperazin-1-yl)-2-(5-(4-fluorophenyl)-2H-tetrazol-2-yl)ethanone (82)

Following general procedure F, by reacting 5-(4-fluorophenyl)-1H-tetrazole (51, 0.30 g, 0.0018 M) with compound 73 (0.30 g, 0.0009 M), compound 82 was obtained as a semisolid mass (66%); IR (KBr, cm−1): 3061, 2927, 1670, 1608, 1503, 1458, 1382, 1327, 1268, 1235, 1156, 1098, 1042, 1015, 844, 822, 739, and 703; 1H-NMR: 8.73 (s, 1H), 8.12–8.08 (m, 3H), 8.00–7.99 (d, 1H, J = 4.0 Hz), 7.58–7.56 (d, 1H, J = 6.0 Hz), 7.42–7.38 (m, 2H), 7.05–7.04 (d, 1H, J = 4.0 Hz), 6.06 (s, 2H), 3.82–3.75 (m, 4H), and 3.21–3.19 (t, 4H); anal. calculated for C22H19N7OClF: C, 58.47; H, 4.24; N, 21.70. Found: C, 58.29; H, 4.51; N, 21.55%; MS (m/z): 452.60 (M + 1)+ and 453.70 (M + 2)+.

1-(4-(7-Chloroquinolin-4-yl)piperazin-1-yl)-2-(5-(4-methylphenyl)-2H-tetrazol-2-yl)ethanone (83)

Following general procedure F, by reacting 5-(4-methylphenyl)-1H-tetrazole (52, 0.29 g, 0.0018 M) with compound 73 (0.30 g, 0.0009 M), compound 83 was obtained as a semisolid mass (63%); IR (KBr, cm−1): 3046, 2923, 2850, 1668, 1609, 1572, 1499, 1460, 1422, 1380, 1268, 1238, 1206, 1149, 1078, 1040, 1015, 827, and 741; 1H-NMR: δ 8.73–8.72 (d, 1H, J = 2.8 Hz), 8.12–8.10 (d, 1H, J = 7.2 Hz), 7.99–7.89 (m, 3H), 7.58–7.56 (dd, 1H, J = 2.0 Hz, 7.2 Hz), 7.39–7.35 (m, 2H), 7.05–7.04 (d, 1H, J = 2.0 Hz), 6.04 (s, 2H), 3.82–3.75 (d, 4H), 3.20–3.19 (s, 4H), and 2.36 (s, 3H); HR-MS (ESI) (m/z): calcd for C23H23ClN7O, 448.1652; found, 448.1630 [M + H]+; anal. calculated for C23H22N7OCl: C, 61.67; H, 4.95; N, 21.89. Found: C, 61.48; H, 5.27; N, 21.77%.

1-(4-(7-Chloroquinolin-4-yl)piperazin-1-yl)-2-(5-(4-isopropylphenyl)-2H-tetrazol-2-yl)ethanone (84)

Following general procedure F, by reacting 5-(4-isopropylphenyl)-1H-tetrazole (53, 0.33 g, 0.0018 M) with compound 73 (0.30 g, 0.0009 M), compound 84 was obtained as a semisolid mass (70%); IR (KBr, cm−1): 2959, 2924, 1671, 1615, 1574, 1498, 1463, 1424, 1381, 1267, 1238, 1151, 1046, 1016, 832, and 740; 1H-NMR: 8.73 (s, 1H), 8.12–8.11 (d, 1H, J = 4.0 Hz), 7.99–7.93 (m, 3H), 7.59–7.57 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.46–7.42 (m, 2H), 7.05–7.04 (d, 1H, J = 4.0 Hz), 6.05 (s, 2H), 3.82–3.75 (m, 4H), 3.21 (s, 4H), 2.96–2.92 (m, 1H), and 1.23–1.20 (m, 6H); anal. calculated for C25H26N7OCl: C, 63.08; H, 5.51; N, 20.60. Found: C, 62.81; H, 5.83; N, 20.43%; MS (m/z): 476.70 (M + 1)+ and 477.70 (M + 2)+.

1-(4-(7-Chloroquinolin-4-yl)piperazin-1-yl)-2-(5-(3-methoxyphenyl)-2H-tetrazol-2-yl)ethanone (85)

Following general procedure F, by reacting 5-(3-methoxyphenyl)-1H-tetrazole (54, 0.32 g, 0.0018 M) with compound 73 (0.30 g, 0.0009 M), compound (85) was obtained as a semisolid mass (69%); IR (KBr, cm−1): 3056, 2927, 2842, 1670, 1609, 1577, 1524, 1466, 1424, 1380, 1324, 1270, 1240, 1125, 1040, 1014, 867, 826 738, and 699; 1H-NMR (CDCl3): δ 8.80–8.79 (d, 1H, J = 5.2 Hz), 8.18–8.15 (d, 1H, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.99–7.97 (d, 1H, J = 2.2 Hz, 9.0 Hz), 7.81–7.74 (m, 2H), 7.54–7.52 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.46–7.41 (t, 1H), 7.08–7.05 (d, 1H), 6.92–6.90 (d, 1H, J = 5.2 Hz), 5.69 (s, 2H), 3.99–3.89 (d, 7H), and 3.37–3.32 (d, 4H, J = 9.9 Hz); anal. calculated for C23H22N7O2Cl: C, 59.55; H, 4.78; N, 21.13. Found: C, 59.28; H, 5.01; N, 20.86%.

1-(4-(7-Chloroquinolin-4-yl)piperazin-1-yl)-2-(5-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-2H-tetrazol-2-yl)-ethanone (86)

Following general procedure F, by reacting 5-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-1H-tetrazole (55, 0.37 g, 0.0018 M) with compound 73 (0.30 g, 0.0009 M), compound 86 was obtained as a semisolid mass (70%); IR (KBr, cm−1): 2930, 2851, 1672, 1613, 1579, 1443, 1379, 1264, 1235, 1134, 1021, 872, 822, and 741; 1H-NMR (CDCl3): δ 8.82–8.81 (d, 1H, J = 4.8 Hz), 8.18–8.17 (d, 1H, J = 2.0 Hz), 8.00–7.98 (d, 1H, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.82–7.79 (d, 1H, J = 2.0 Hz, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.73–7.70 (m, 1H), 7.55–7.53 (dd, 1H, J = 2.2 Hz, 9.0 Hz), 7.02–7.00 (d, 1H, J = 8.4 Hz), 6.93–6.92 (d, 1H, J = 5.2 Hz), 5.67 (s, 2H), 4.02–3.98 (t, 3H), and 3.38–3.34 (d, 8H); anal. calculated for C24H24N7O3Cl: C, 58.36; H, 4.90; N, 19.85. Found: C, 58.17; H, 5.23; N, 19.57%; MS (m/z): 494.70 (M + 1)+ and 495.70 (M + 2)+.

1-(4-(7-Chloroquinolin-4-yl)piperazin-1-yl)-2-(5-(4-methoxyphenyl)-2H-tetrazol-2-yl)ethanone (87)