Abstract

Comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) has been shown to have a wide range of positive impacts for K-12 students. Despite its demonstrated benefits, many K-12 students in the USA do not receive CSE. Because of this, college may be an opportune time to teach this information. However, little is known about the impact of CSE at institutions of higher education. To synthesise knowledge about the impacts of college-level sexual health courses in the USA, a review of the topic was conducted. A review searching Ebscohost, ProQuest, PubMed, and Google Scholar was undertaken. Following the search, a second coder reviewed the articles to confirm eligibility. 13 articles, published between 2001 and 2020, met the inclusion criteria and were included in the review. A wide range of outcomes were reported. These included increased health promoting behaviours, less homophobic and judgemental attitudes around sexuality, improved communication and relationships, and increased understanding of sexual violence. College sexual health courses have high potential efficacy to provide CSE and fill gaps in US students’ sexual health knowledge. Future research should corroborate the existing outcomes using randomisation and more diverse samples and examine whether these courses are effective in preventing sexual assault.

Keywords: Comprehensive sexuality education, college, review, qualitative, quantitative

Introduction

Comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) plays an important role in preparing young people to lead sexually healthy lives (UNESCO 2018). The importance and efficacy of CSE has been well-documented, with a wide range of impacts observed. For example, CSE has been found to reduce rates of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) (Chin et al. 2012), as well as to increase the use of condoms and contraception (CDC 2020). Globally, the landscape regarding CSE is highly variable (UNESCO 2021). This article focuses specifically on the USA where provision of CSE varies widely depending on context (Guttmacher 2022a), and where more widespread provision of CSE might ameliorate the high rates of STIs (CDC 2021) and unplanned pregnancy (Guttmacher 2022b) documented in the USA.

A recent review of the literature presented evidence for even broader-ranging benefits of CSE, including promotion of healthy relationships, appreciation of sexual diversity, and reductions in dating and intimate partner violence (Goldfarb and Lieberman 2021). Additionally, recent research has suggested that CSE may be protective against sexual assault victimisation (Santelli et al. 2018), and it has been theorised that CSE could prevent the perpetration of sexual violence as well (Schneider and Hirsch 2018). Persistently high rates of sexual assault have been documented in the USA (Potter 2019), as well as in other locations where data are available (WHO 2021), and thus CSE may be one strategy to reduce those rates.

Despite evidence of its efficacy, provision of sexuality education is uneven in K-12 settings in the USA (Lindberg and Kantor 2022), with only 38 states and the District of Columbia (DC) mandating sex education and/or HIV education (Guttmacher 2022). Amongst these, only 25 states and DC mandate both; and only 17 states require content to be medically accurate (Guttmacher 2022). Additionally, many young people are not given information about how to engage in safer sex, or how to say no to sex (Lindberg, Maddow-Zimet, and Boonstra 2016), and only 11 states mandate that the importance of consent in sexual activity be covered (Guttmacher 2022). In this way, the USA is an outlier compared to both wealthy and low- and middle-income countries, many of which mandate the provision of sexuality education to students (UNESCO 2021).

Unsurprisingly, multiple studies have found that undergraduates in the USA have limited sexual health knowledge, including substantial gaps in their knowledge and understanding of safer sex (Feigenbaum and Weinstein 1995; Synovitz et al. 2002; Toews and Yazedjian 2012). Perhaps in part to address those gaps, some colleges and universities offer human sexuality courses. These courses are similar to CSE in that they focus on knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours, although not all include skills components (Oswalt et al. 2015). Additionally, many courses include key concepts as defined by SIECUS’ guidelines for comprehensive sexuality education (Oswalt et al. 2015). As well as providing information about contraception and STIs, some university courses include information about healthy sexuality and relationships (Goldfarb 2005), which can fill remaining gaps students may have even after previous school-based sexuality education. Individual studies have shown that sexual health courses on college campuses can, amongst other outcomes, increase rates of contraception use (Feigenbaum and Weinstein 1995), increase understanding of sexual assault (Olmstead, Conrad, and Davis 2020), and enhance romantic relationships (Pettijohn and Dunlap 2010). However, a brief search of the literature did not locate any published work that synthesised the overall state of existing knowledge. Additionally, many curricula have not been thoroughly evaluated; therefore, there is a need to examine the effectiveness of the implemented programmes (DeGue 2014). In 2022, a review on this topic was published that summarised existing work describing the kinds of sexuality education courses offered in higher education in the USA, providing a valuable taxonomy and pointing to some key silences (Manning-Ouellette and Shikongo-Asino 2022). While this review discussed the impact of these courses on perceived sexual health knowledge, it did not focus on research on other impacts of these courses (Manning-Ouellette and Shikongo-Asino 2022). This review therefore builds on that previous work by reviewing the existing literature on more, and broader, outcomes of college-level sexual health curricula. This paper summarises main findings, discusses the strengths and limitations of the existing literature, and provides suggestions for future research. If found to be effective, promoting these types of courses in college may be one component of a national strategy to address the USA’s dismal outcomes in sexual health, as well as a tool to prevent sexual assault.

Methods

Search Strategy

This review utilised methodology from the systematic review methods described by Khan and colleagues (2003). In September 2020, a systematic search of the literature was conducted, with a brief follow-up review taking place in October 2022, with no new studies identified. The databases Ebscohost, ProQuest, PubMed, and Google Scholar were utilised. Key words, including, and related to, ‘college,’ ‘human sexuality,’ ‘sexuality education,’ and ‘course’ were searched in various combinations. Additionally, reference-chaining was used to find additional research. After articles had been identified by the first author, a second coder reviewed them to ensure they met inclusion criteria.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they were published between the years 2000 and 2022, took place in the USA, were published in English, evaluated a college-level academic CSE course, such as a human sexuality or similar course, and assessed the impacts or outcomes of the course. CSE was defined as education that covered information included in SIECUS’s Key Concepts, such as information on human sexuality, healthy relationships, human development, and STIs (SIECUS 2004). The inclusion criteria draw upon previously published reviews defining human sexuality courses as CSE (Manning-Ouellette and Shikongo-Asino 2022; Oswalt et al. 2015). Additionally, some courses explicitly identified course content as ‘sexuality education.’

Studies were excluded if they assessed a bystander or consent education course, if the course was not taught by the college or university (e.g. took the form of a workshop led by an outside organisation), or if the course assessed was taught by someone other than a college instructor (e.g. was peer-led). Peer-led and workshop- type courses were excluded in order to focus on the impacts of comprehensive academic courses that colleges offer for credit as part of a student’s education; the possibility of having coursework be part of a multi-level comprehensive approach to promoting sexual health and preventing sexual violence merits specifically evaluating the impact of those classes. These criteria are consistent with other studies that have focused solely on academic instructor-led courses (Oswalt et al. 2015). Future research might usefully evaluate the impact of peer-led or workshop-type programming at the college level. Additionally, literature that did not assess impacts or outcomes was excluded from the review.

Results

Thirteen articles fitted the inclusion criteria, and no new studies were identified in a follow-up review covering the period September 2020 and October 2022. Published between 2001 and 2020, the articles reviewed here examined a range of outcomes using both qualitative and quantitative methods (Table 1). The quality and methodology of the studies varied widely, with some using pre-tests or controls, and others only assessing participants following the courses. Sample sizes ranged from under 10 participants to over 200. Due to the limited number of articles identified in the search, the authors decided to include all studies in order to get as full a picture of the literature as possible.

Table 1.

Design and Characteristics of Studies Assessing Impacts of College Sexuality Education Courses

| Study | Study Design | Sample Size | Reported Demographics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Askew 2007 | Qualitative interviews, post | N=9 | Female: 100%; White: n=8, White Hispanic: n=1; Christian or Catholic: 100%; Heterosexual: 100% |

| Chonody, Siebert, and Rutledge 2009 | Pre/post-test | N=210 | Undergrad: 53%; Female: 89%; No religious affiliation: 23%, Do not attend religious services: 52% |

| Finken 2002 | Pre/post-test (after a lecture on homosexuality and at the end of the semester); comparison with a child development course | N=280 | Female: 74%; European American: 72%, Asian American: 18% |

| Goldfarb 2005 | Qualitative questionnaire, pre/post | N=148 | Not reported |

| Henry 2013 | Questionnaire and qualitative interviews (couple and individual) | N=16 | Female: 50% (all couples were heterosexual); White: 75%; Christian: 50% |

| Noland et al. 2009 | Pre/post-test; comparison with psychology students in several different classes | N=653 | Female: 75%; European American: 66%, African American: 19%, Hispanic: 11%; Protestant affiliation: 66%, Catholic: 23% |

| Olmstead, Conrad, and Davis 2020 | Qualitative interviews, towards the end of the semester | N=46 | Female: 67.4%; White: 50%, African American: 45.7%; Heterosexual: 89.1%; Christian: 71.7% |

| Pettijohn and Dunlap 2010 | Pre/post-test | N=85 | Female: 87.1%; Heterosexual: 95.2% |

| Rogers, McRee, and Arntz 2009 | Pre/post-test; comparison with students in professional and social science courses | N=128 | Female: 86.2% in sexuality class, 58.7% in comparison group |

| Rutledge et al. 2011 | Pre/post-test | N=254 | Female: 84.8%; White: 74.7%, African American or Black: 18.7% |

| Voss and Kogan 2001 | Pre/post-test for Fall students; comparison with pre-test for Winter cohort | Pre-test experimental: n=170, Post-test experimental n=184; Comparison cohort: n=341 | Female: 61% in Fall, 66% in Winter; White: 88%; Heterosexual: >98% |

| Warshowsky et al. 2020 | Pre/post-test; comparison with Human Sexuality and Culture, and Psychology of Personality courses | N=271 | Female: 97.6%, Trans/other: 2.2%; European American: 59.7%, Latin American: 16.5%, Asia American: 10.4%, African American: 5.1%; Christian: 59%; Exclusively heterosexual: 75.1% |

| Wright and Cullen 2001 | Pre/post-test | N=97 | Female: 62.9%; Caucasian: 83%, African American: 7%, Hispanic: 7% |

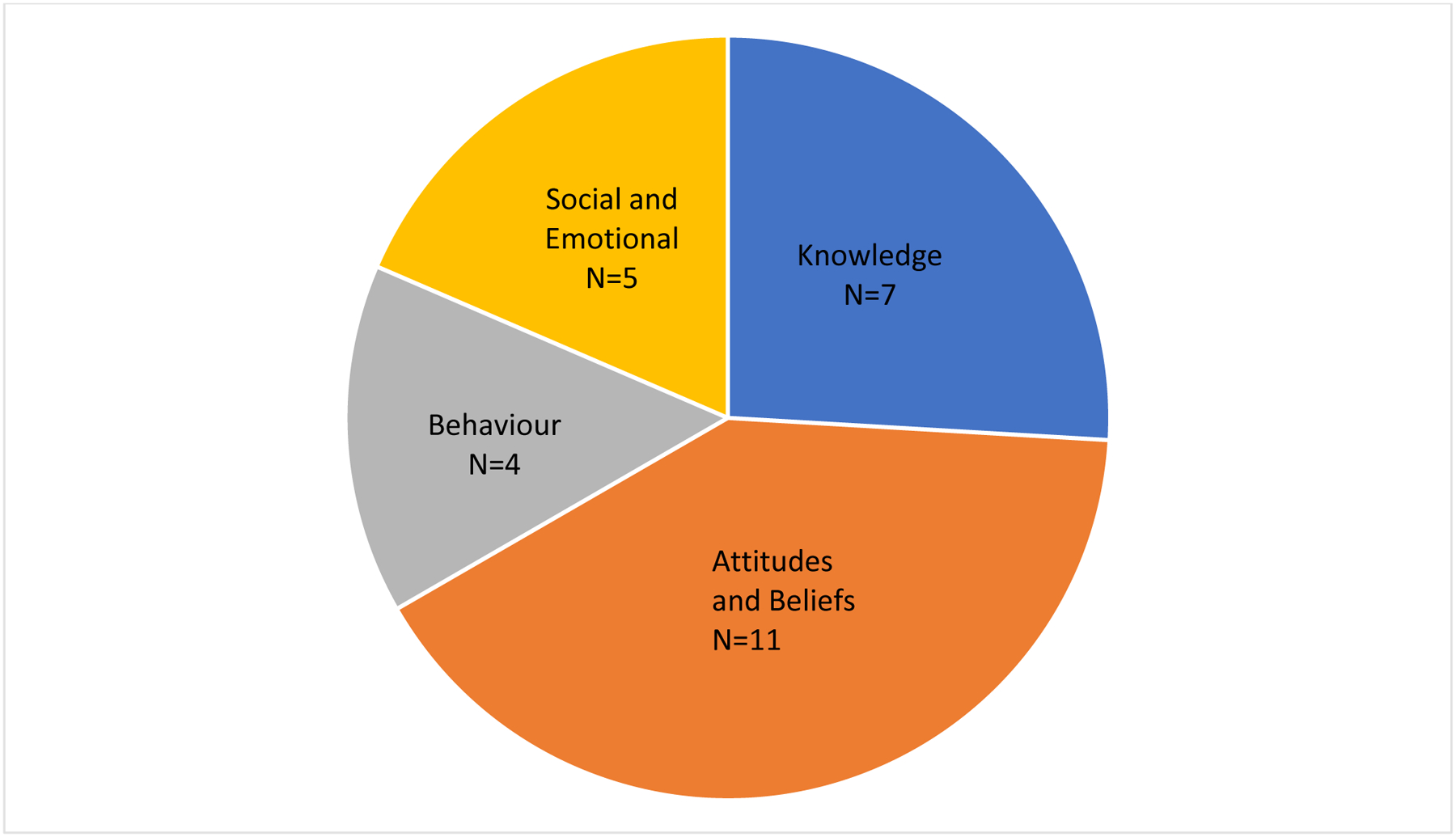

Studies examined the impact of courses taught at institutions of higher education in a variety of regions of the USA, including a state university in the Rocky Mountains, a public university in the Southeast, a ‘Catholic leaning’ college in the Pacific Northwest, and colleges in the Midwest and Northeast. The classes ranged in size from a small seminar with fewer than 20 students, to a large lecture of over 100 students (Table 2). Research assessed knowledge, attitudes and beliefs, behaviour, and social and emotional impacts of participation in college sexual health courses.

Table 2.

Content and Size of Courses Evaluated

| Study | Class: Size | Course Content |

|---|---|---|

| Askew 2007 | Feminist‐informed human sexuality course: 53 students | Topics found in comprehensive sex education courses, as well as desire, arousal, and masturbation. Messages of empowerment and critiques of current sexual discourses. Lectures, discussion groups, debates, student presentations. Students examined reactions to class content through personal journals. Course text: Westheimer, R. K., & Lopater, S. (2002). Human Sexuality: A psychosocial perspective. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. |

| Chonody, Siebert, and Rutledge 2009 | Undergrad and grad human sexuality course: Averaged 20–30 students | Topics included knowledge about sex and sexuality, including sexual identity, reproduction, and STIs. Used a ‘bio-psycho-social approach to understanding sexuality’ across the life course. Included content on romantic and sexual relationships, sexual dysfunction, and diversity. Space to explore attitudes and beliefs about sexuality and related topics (ex: sex work, sexual orientation) through student presentations. Highly interactive lectures and discussions. Course text: Crooks, R., & Baur, K. (2004). Our sexuality (9th ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth |

| Finken 2002 | Human sexuality course: 147 students | Included a unit on homosexuality: readings, lectures, and debates/discussions about sexual orientation. |

| Goldfarb 2005 | Human sexuality course: Multiple sections, approximately 35 students each | Included information on pregnancy and STI prevention. Also touched upon other, and more positive aspects of sexuality, such as healthy relationships and how to appreciate their own sexuality. ‘CSE’. |

| Henry 2013 | Human sexuality course: Several course sections, unknown size | ‘Sexuality education’. |

| Noland et al. 2009 | Human sexuality course: Sections of 50–160 students and ‘Family Life and Sex Education’ class: required for Health majors, sections capped at 50 students | Human Sexuality: Focus on providing factual knowledge, not changing attitudes. Large lecture with small group discussion, guest lecturers, videos, and a panel discussion with students from the university’s LGBT student association. Course text: Rathus, S. A., Nevid, J. S., & Fichner-Rathus, L. (2005). Human sexuality in a world of diversity (6th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon. Family Life and Sex Education: Factual information to help students make healthy sexual decisions and develop healthy attitudes around sexual diversity. Discussions about attitudes and beliefs around gender and sexuality. Focus on how the media influences perceptions of these topics and attitudes/beliefs. Lectures with small group discussions, guest lecture from a metropolitan gay and lesbian association. Course text: DeGenova, M. K., & Rice, F. P. (2005). Intimate Relationships, Marriages, and Families (5th ed.). Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill. |

| Olmstead, Conrad, and Davis 2020 | Sexual health seminar ‘Sex on Campus’: Three sections, enrolment capped at 18 students per section | Covered majority of the 19 CDC recommended topics, plus alcohol use, consent, and relationship violence. Brief lecture followed by discussion, occasional guest lectures. |

| Pettijohn and Dunlap 2010 | Human sexual behaviour course: 85 students across two sections | Factual information about various sexual health topics including pregnancy, STIs, sexual anatomy, and sexual dysfunction. Topics included gender roles and stereotypes, sex in the media, sexual abuse, and sexual variations. Primarily lecture, with discussions and anonymous student questions. Course text: Strong, B., Yarber, W. L., Sayad, B. W., & DeVault, C. (2008). Human sexuality: Diversity in contemporary America (6th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. Assignments from: Taverner, W. J. (2008). Taking sides: Clashing views in human sexuality (10th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. |

| Rogers, McRee, and Arntz 2009 | Human sexuality course: 56 students | Topics included factual information about sexual anatomy and reproduction, as well as information about healthy sexuality, body image, and sexual diversity. Lectures (including guest lectures), panel with LGBT elders, videos, class discussion. |

| Rutledge et al. 2011 | Human sexuality course: Averaged 20–30 students | Course designed primarily for social work and allied health and education students. Focused on issues and attitudes about sexuality, using a biopsychosocial perspective. Discussed how sexual and reproductive attitudes, values, and behaviours vary. Topics included information about anatomy, contraception, pregnancy, gender roles, sexual orientation, and communication. Graduate students received additional, clinical information. Lectures, discussion, presentations, and documentaries. Course text: Crooks, R.L., and K. Baur. 2004. Our sexuality. 8th ed. Belmont, CA: Thomson. |

| Voss and Kogan 2001 | Human sexuality course: Approximately 210 students | Information on biological, sociological, and psychological aspects of sexuality. Focused on health promotion and risk reduction, including information on cancers, sexual risk behaviours, and identifying sexual values. Practiced communicating about sex. Lectures, guest speakers, video presentations, and classroom exercises. |

| Warshowsky et al. 2020 | Psychology of human sexuality course: Approximately 140 students | Taught from an applied psychology perspective, focused on research about the ‘orgasm gap’ and its underlying factors, such as body-image, communication, and genital self-image. Sex-positive approach. Lecture and class discussions. |

| Wright and Cullen 2001 | Human sexuality course: 2 sections, each capped at 60 students | Information about sexuality and sexual minorities, including myth-dispelling. Lectures, guest panel from the university’s sexual minority student group. Course text: Hyde, J. S., & DeLamater, J. D. (1997). Understanding human sexuality. New York: McGraw-Hill. |

Outcome: Knowledge

Seven articles assessed changes in knowledge for students who took sexual health courses (Tables 3 and 4, Figure 1). Interestingly, six studies did not measure actual sexual health knowledge, but rather focused on perceived knowledge (Tables 3 and 4). Only one study that examined the impact of a sexual health course on knowledge relied upon a test of sexual topics to assess changes. This research found modest, though significant, increases in knowledge (Noland et al. 2009).

Table 3.

Outcomes Examined, Findings, and Limitations of Studies Assessing College Sexuality Education Courses

| Study | Outcome Examined | Relevant Findings | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Askew 2007 | Attitudes around sex, sexuality, gender stereotypes, and other topics that may arise in the interview process. | Increased ‘comfort’ with sexuality (n=7); changed attitudes regarding sexual desire and pleasure (n=6). Changed dynamics in sexual encounters—women can be dominant (n=1). Reduced feelings of guilt and seeing sex as something negative (n=6); Improved body image (n=3). Improved confidence as a woman, in sex and generally (n=3). |

Only 9 students interviewed (all white, heterosexual women). All raised as Christian. Interviews occurred towards the end of the course—no baseline, though participants provided information about their experiences and beliefs from before having taken the class; No control group. |

| Chonody, Siebert, and Rutledge 2009 | Score on the Index of Attitudes Towards Homosexuality. | Reduced scores on the Index of Attitudes Toward Homosexuality. | Majority female students. Potential bias in who took the course; Majority reported a ‘helping profession’ (e.g., social work, psychology) or an education programme; No control group. |

| Finken 2002 | Scores on Index of Homophobia. | Decrease in female students’ negative attitudes towards sexual minorities (Index of Homophobia scores) by the end of the course (not right after the lecture on homosexuality). | Majority white and female. Potential bias in who took the course. |

| Goldfarb 2005 | Impact of the course. | Increased knowledge about STIs, contraception, sexual orientation, sexual identity, abortion, and abuse. Applying new knowledge, skills to real life; Improved attitude and comfort with discussing sex and sexuality; Intention to get STI-tested; Less judgmental attitudes about sexuality; Improved sex life and relationships; Improved communication; Better understanding of their bodies’ and sexualities’. |

Self-reported change. Unclear what proportion of the class experienced these results; Potential bias in who took the course; No control group. |

| Henry 2013 | Impact of course on relationship. | Increased comfort and less secretive about sex and sexuality; Reduced fear and guilt around sex; Increased confidence and self-esteem; Improved sex lives and relationships; Improved communication and openness about sex; Increased knowledge about un/healthy relationships; Increased self-understanding, and understanding of partners; Improved body-image; Feelings of empowerment, women felt more able to direct sexual activity; New sexual behaviours (positions, toys etc.); Increased knowledge about STIs, contraception, anatomy (breast health); Started using contraception discussed in class. Began looking for STI symptoms. Increased knowledge about women’s bodies and sexual response; Increased refusal skills. Both members of the couple benefited from the class. |

Self-reported changes. Unclear what proportion of interviewees experienced these results. No baseline. Potentially biased sample in those who took the class and/or agreed to be interviewed; Only students in relationships were interviewed and may have experienced different outcome than single students; No control group. |

| Noland et al. 2009 | Sexual health knowledge measured using an instrument developed for the study. Included 23 short-answer, 5 true/false, and 16 matching questions. Questions about sexual anatomy, sexual health, sexual behaviour, and legal issues (e.g. is prostitution legal in USA?). Attitudes towards sexual orientation and gender-reassignment surgery. |

Modest increases in sexual health knowledge (sexual anatomy, sexual health, sexual behaviour) compared with control group; No change in attitudes towards sexual orientation and gender-reassignment surgery. | Potential bias in who took the course; Mostly white women. |

| Olmstead, Conrad, and Davis 2020 | Impact of the course. | Increased perceived knowledge about STIs and contraception (n=28); Increased knowledge of alcohol (n=6); Increased knowledge of sexual health resources (n=5). Increased knowledge of rape (n=11), one student listed his intention to help those in ‘distress or trouble’; Impacted beliefs about finding a suitable partner and creating healthy sexual relationships with future partners (n=11). Disseminated course content to friends and partners (n=43). |

Potential bias in who took the course; Self-reported changes; Short interviews; No baseline; No control group. |

| Pettijohn and Dunlap 2010 | Brief Sexual Attitudes Scale. Trueblood Sexual Attitudes Questionnaire. Impact of the course. |

Attitude change: greater tolerance for sexual practices of others. More liberal and positive sexual attitudes; Increased acceptance of sexual variations; Improved sexual self-image and relationships; Increased comfort with their sexuality; Increased perceived sexual knowledge. |

Selection bias in who took the class; Mostly straight white women; No control group. |

| Rogers, McRee, and Arntz 2009 | Self-perceived knowledge; Sexual Opinion Survey; Bem Sex-Role Inventory; Homophobia Scale. | Increase in self-reported sexual knowledge; Decreased homophobic attitudes. | Self-reported ‘knowledge about sex’; demographic differences with the comparison group. |

| Rutledge et al. 2011 | Self-perceived knowledge. | Increase in self-perceived sexual knowledge; Anecdotal evidence of increased communication about sex with partners and parents. | Self-reported sexual knowledge; Unclear how anecdotal evidence was gathered, and to what extent it was true for all participants; Potentially biased sample in who took the course; No control group. |

| Voss and Kogan 2001 | Risk behaviours; health promoting behaviours; condom use; communication about sexual history. | Increased rates of self-breast or testicular exam; Female students increased asking partners about HIV testing and injection drug use. | Potentially biased sample in who took the course. Potentially low levels of class attendance (reduced dose). |

| Warshowsky et al. 2020 | Attitudes Towards Women’s Genitals Scale; Cognitive Distraction During Sexual Activity Scale; Female Sexual Subjectivity Inventory; Female Orgasm Scale; Female Partner Communication During Sexual Activity Scale. | Improved sexual functioning. Increased scores on Attitudes Towards Women’s Genitals Scale. Increased scores (less distraction) on Cognitive Distraction During Sexual Activity Scale; Improvements on the Female Orgasm Scale; Improvements on Female Partner Communication During Sexual Activity Scale. |

Variation in demographics between the control courses; Potentially biased sample in who took the course. |

| Wright and Cullen 2001 | Bem Sex-Role Inventory. Sexual Opinion Survey. Homophobia Scale - Derogatis Attitude subscale—section IV; Derogative Information subscale—section I. |

Reductions in levels of homophobia; Reductions in levels of erotophobia; Less adherence to sexually conservative attitudes. | Potentially biased sample in who took the course; No control group. |

Table 4.

Summary of Outcomes and Key Findings

| Outcome | Studies | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge of sexual health topics | Noland et al. 2009 | Modest increases in sexual health knowledge (sexual anatomy, sexual health, sexual behaviour) compared with control group |

| Self-perceived knowledge of sexual health topics |

Goldfarb 2005

Henry 2013 Olmstead, Conrad, and Davis 2020 Pettijohn and Dunlap 2010 Rogers, McRee, and Arntz 2009 Rutledge et al. 2011 |

Self-perceived increases in knowledge about sexual health generally; some student reported increases in knowledge about STIs, contraception, anatomy, and sexual orientation and identity |

| Attitudes around sexual orientation |

Chonody, Siebert, and Rutledge 2009

Goldfarb 2005 Finken 2002 Pettijohn and Dunlap 2010 Rogers, McRee, and Arntz 2009 Wright and Cullen 2001 |

Decrease in homophobic attitudes; greater acceptance of sexual variation |

| Comfort with sex and sexuality |

Askew 2007

Goldfarb 2005 Henry 2013 Pettijohn and Dunlap 2010 Wright and Cullen 2001 |

Greater comfort with sex and sexuality; reduction in erotophobia |

| Guilt about sex |

Askew 2007

Henry 2013 |

Reduced feelings of guilt about sex |

| Confidence |

Askew 2007

Henry 2013 |

Increased confidence and self-esteem |

| Body image |

Askew 2007

Henry 2013 |

Improved body image |

| Relationships |

Goldfarb 2005

Henry 2013 Pettijohn and Dunlap 2010 |

Improved romantic and sexual relationships |

| Communication |

Goldfarb 2005

Henry 2013 Rutledge et al. 2011 Voss and Kogan 2001 Warshowsky et al. 2020 |

Improved communication with partners and others about sex and sexual topics |

| Quality of sex/sex lives |

Goldfarb 2005

Henry 2013 Warshowsky et al. 2020 |

Improved sexual experiences |

| Health behaviours | Voss and Kogan 2001 | Increased rates of self-breast or testicular exam; female students increased asking partners about HIV testing and intravenous drug use |

Figure 1.

Number of Studies Assessing Major Outcomes

Note: Total N > the number of studies, as some studies assessed multiple outcomes

Both qualitative and quantitative studies reported perceived knowledge increases in a variety of sexual health topics including STIs and contraception (Goldfarb 2005; Henry 2013; Olmstead, Conrad, and Davis 2020; Rogers, McRee, and Arntz 2009), sexual violence and abuse (Goldfarb 2005; Olmstead, Conrad, and Davis 2020), women’s sexual response and healthy relationships, and refusal skills (Henry 2013). Two studies asked students to rank their sexual knowledge using Likert scales, which increased following the course (Pettijohn and Dunlap 2010; Rutledge et al. 2011).

Outcome: Attitudes and Beliefs

Eleven studies assessed students’ attitudes and beliefs about a range of sexuality-related topics (Tables 3 and 4, Figure 1). Seven articles quantitatively assessed the impact of sexuality courses on homophobic attitudes and attitudes towards sexual minorities (Chonody, Siebert, and Rutledge 2009; Finken 2002; Goldfarb 2005; Noland et al. 2009; Pettijohn and Dunlap 2010; Rogers, McRee, and Arntz 2009; Wright and Cullen 2001). Six of those seven articles found decreases in participants’ scores on various measures of homophobia (Chonody, Siebert, and Rutledge 2009; Finken 2002; Goldfarb 2005; Pettijohn and Dunlap 2010; Rogers, McRee, and Arntz 2009; Wright and Cullen 2001). However, Finken found that only female students’ Index of Homophobia scores decreased following completion of the course (2002), and Noland and colleagues reported no change in participants’ initial, neutral, attitudes towards sexual orientation (2009).

Seven articles measured the impact of sexual health courses on students’ overall attitudes towards sexuality, using both qualitative and quantitative methods. Four studies saw increases in comfort with sexuality and sex (Askew 2007; Henry 2013; Pettijohn and Dunlap 2010), as well as discussing sex (Goldfarb 2005). Two studies reported more positive attitudes around sexuality following the courses (Askew 2007; Pettijohn and Dunlap 2010). One study found reductions in erotophobia and reduced adherence to sexually conservative attitudes (Wright and Cullen 2001), and two others showed increased tolerance towards the sexual practices of others (Goldfarb 2005; Pettijohn and Dunlap 2010). Through qualitative interviews, both Askew and Henry found reduced fear about having sex, and Askew further reported reduced guilt around sex (2007; 20013). Using quantitative measures, one study found that participants experienced less distraction during sex, changed attitudes about women’s desire and pleasure, and improved attitudes towards women’s genitals (Warshowsky et al. 2020). In another study, students who took a sexual health seminar reported that the course helped to shape their beliefs about the importance of creating healthy sexual relationships (Olmstead, Conrad, and Davis 2020).

Outcome: Behaviour

Five studies assessed student behaviour after participating in the course, some using qualitative and others using quantitative information. These included changes in health behaviours, like using contraception, looking for STI symptoms (Henry 2013), and performing self-breast or testicular examinations (Voss and Kogan 2001). Four studies found improved communication, both with partners, and about sexual topics in general (Goldfarb 2005; Henry 2013; Rutledge et al. 2011; Warshowsky et al. 2020). Quantitatively, Voss & Kogan found that female students were more likely to ask partners about HIV testing and injection drug use after taking the sexual health course (2001).

Outcome: Social and Emotional

Students who took sexual health courses described a wide range of impacts, both on interpersonal relationships and themselves. Two articles found that participants who took a sexual health course reported improved relationships (Goldfarb 2005; Pettijohn and Dunlap 2010). Both Goldfarb and Henry found self-reported improved sex-lives, and using a quantitative measure, Warshowsky et al. found improved orgasms and sexual functioning (2005; 2013; 2020). Female participants reported feeling equal to, and less reliant upon, the opposite sex, and that they could be in charge during sexual encounters (Askew 2007). Three articles reported improved body image (Askew 2007; Henry 2013), and sexual self-image (Pettijohn and Dunlap 2010). Similarly, Askew and Henry both qualitatively found improved confidence and self-esteem (2007; 2013), and Goldfarb reported that participants described having a better understanding of their bodies and sexualities (2005).

Discussion

This paper reviewed the existing literature on the impacts of college-level sexual health curricula in the USA. Included studies assessed outcomes ranging from use of contraception and STI testing, to impacts on sexual and romantic relationships and comfort with sexuality. No study that measured condom use found any impact, but those that assessed a broader range of impacts using both qualitative and quantitative study designs found many positive changes in both attitudes and health behaviours. In one study, for example, one student reported that she began using a specific form of contraception after it was covered in class (Henry 2013). Additionally, Voss & Kogan (2001) found that students performed self-breast and testicular exams following the course.

Studies also found reduced homophobic attitudes following sexual health courses (Chonody, Siebert, and Rutledge 2009; Finken 2002; Goldfarb 2005; Pettijohn and Dunlap 2010; Rogers, McRee, and Arntz 2009; Wright and Cullen 2001). Research has shown that experiencing homophobia can negatively impact college students’ mental health (Yamakawa and Williams 2001), prevent students from reaching their full academic potential, and keep students from fully participating in college life (Rankin 2005). Therefore, human sexuality classes may not only be able to build a safer environment, but also a more inclusive one.

In addition to changing attitudes and beliefs, some of these sexual health courses improved students’ relationships (Goldfarb 2005; Henry 2013; Pettijohn and Dunlap 2010). This is critical, as students may be able to utilise what they have learned in class for the rest of their lives. Beyond the general importance and benefits of being in a healthy relationship, research has shown that improving relationships can improve individuals’ mental health (Braithwaite and Holt-Lunstad 2017). According to the World Health Organization, ‘health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’ (WHO 2002). Therefore, sexual health concerns not only the absence of STIs or unwanted pregnancy, but having positive and fulfilling relationships as well.

While both female and male identifying students reported positive changes, this was especially true for female students. However, most course and resulting study participants were majority, or all women, which could bias results. While this may be partially due to the fact that many of these courses were housed in social science departments, or were required or elective courses for ‘helping professions’ majors, both of which tend to attract female students, research has shown that gender ratio differences in human sexuality courses cannot be completely explained by major or institutional gender ratios (King, Burke, and Gates 2020); and Rogers and colleagues (2009) found that there were significantly more women on human sexuality course than on comparison courses, which comprised both professional and social science courses. Instructors in the field of sexuality education have posited that men feel that they already know enough about sex and sexuality from pornography, or feel that stereotypes of masculinity prevent male students from enrolling in sexual health courses (King, Burke, and Gates 2020). Making these courses more commonplace in college may increase their normalisation, and potentially affect both levels of participation, and gender ratios.

As attention is increasingly given to the potential of CSE to prevent sexual assault (Schneider and Hirsch 2018), results from some of the studies reviewed lend credence to this idea. The research reviewed here suggests that in the context of higher education, sexuality education may prevent sexual assault by both improving people’s ability to protect themselves against assault, and prevent people from committing assaults in the first place. While none of the studies reviewed examined the prevention of sexual assault as an outcome, several did find improved communication (Chonody, Siebert, and Rutledge 2009; Goldfarb 2005; Warshowsky et al. 2020), increased knowledge about healthy relationships, and women feeling more able to direct sexual activity (Henry 2013) and be less reliant on the opposite sex (Askew 2007). Along with improved refusal skills (Henry 2013), these outcomes could help protect people from assault. Additionally, those who participated in a sexual health course in one study showed a desire and intention to create healthy relationships with future partners (Olmstead, Conrad, and Davis 2020). From a prevention point of view, one male student indicated an increased understanding of rape and future willingness to step in to help those who may be in an unsafe situation (Olmstead, Conrad, and Davis 2020). These results indicate that college sexual health curricula may hold some potential to prevent sexual assault.

The studies reviewed here align with existing syntheses of research on CSE at the pre-college level, and suggest that even at the higher education level, sexuality education may have a wide array of benefits for young people. In order to improve sexual health outcomes, help students live healthy and positive sexual lives, and reduce sexual violence, it is critical for CSE to be available to students at every educational level, including at university and college.

Limitations

There are many methodological limitations to the research reviewed. There are few comparative investigations in which data have been collected from carefully constructed experimental and control groups. Instead, the majority of the published studies report on data generated from one group of students studying an elective course, which could introduce bias into the results. Importantly, the students who take elective sexual health courses may differ from those who would not. Additionally, for studies that did not survey all the students attending a class, there may have been bias in who agreed to be interviewed.

The make-up of the samples, which comprise mostly white, heterosexual women, could also detract from the generalisability of findings. Many studies measured self-reported changes, introducing the possibility of social desirability bias. In qualitative studies, some outcomes were reported by only a few of the students who participated, which may reduce the findings’ level of credibility. None of the studies reviewed examined the long-term effects of the courses, which may have attenuated over time.

In addition to limitations to the work reviewed, there are limitations to the review itself. Papers from a twenty-year period (2000–2020) were included in the review, and it is important to note the significant political and cultural changes that the USA has undergone over this period. Finally, this review focused exclusively on research in the USA, which is near unique amongst wealthy nations for its poor sexual health outcomes, limiting the generalisability of findings beyond this context.

Strengths

Despite these limitations, the reviewed literature contained several strengths. Many of the studies employed pre and post-tests, and some included control groups. A wide range of impacts, including knowledge, attitudes and beliefs, and behaviour, were assessed. Impacts were demonstrated using both qualitative and quantitative data. Additionally, multiple studies found similar outcomes, further strengthening the validity of the results.

Future research

Several areas of future research are highlighted. While randomisation may be difficult, future research should utilise randomised controlled trials. As some colleges and universities in states that do not require K-12 sexuality education in schools consider requiring sex education (Seaver 2021), it is even more urgent to understand the impact of these courses. Further, more diverse samples are needed in order to better understand the impacts of college sexual health curricula, and longitudinal follow-up could improve understanding about the medium to longer effects of these courses.

The courses assessed in the studies included both large lectures and small seminars; no discernible patterns emerged from the small number of articles identified and examined for this review, so future research should examine how course characteristics, such as class type and size, impact outcomes.

Although the focus of this review was on the USA, examining other countries’ provision of CSE and sexual health outcomes could help to further illuminate the larger-scale impacts of CSE. For example, the Netherlands, which mandates CSE for students in primary school (de Melker 2015), has both lower rates of unintended pregnancy (Guttmacher 2022b,c) and sexual assault (Knoema 2022a,b) than the USA.

Acknowledgements

We thank Alex Junker (Institute of Human Nutrition, Columbia University Irving Medical Center) for their conceptual and editorial review of the manuscript.

Funding

At the time of writing, JSH was supported in part by funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development under grant number P2CHD058486, awarded to the Columbia Population Research Center. SNB and ALC did not receive grant funding to support this work. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the US National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement: The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

References

- Askew Julie. 2007. “Breaking the Taboo: An Exploration of Female University Students’ Experiences of Attending a Feminist‐informed Sex Education Course.” Sex Education 7 (3): 251–264. [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite Scott, and Holt-Lunstad Julianne. 2017. “Romantic Relationships and Mental Health.” Current Opinion in Psychology 13: 120–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2020. “What Works: Sexual Health Education.” https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/whatworks/what-works-sexual-health-education.htm

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2021. “Reported STDs Reach All-Time High for 6th Consecutive Year.” Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/2021/2019-STD-surveillance-report.html

- Chin Helen B., Sipe Theresa Ann, Elder Randy, Mercer Shawna L., Chattopadhyay Sajal K., Jacob Verughese, Wethington Holly R., et al. 2012. “The Effectiveness of Group-Based Comprehensive Risk-Reduction and Abstinence Education Interventions to Prevent or Reduce the Risk of Adolescent Pregnancy, Human Immunodeficiency Virus, and Sexually Transmitted Infections: Two Systematic Reviews for the Guide to Community Preventive Services.” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 42 (3): 272–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chonody Jill M., Siebert Darcy Clay, and Rutledge Scott Edward. 2009. “College Students’ Attitudes Toward Gays and Lesbians.” Journal of Social Work Education 45 (3): 499–512. [Google Scholar]

- de Melker Saskia. 2015. “The Case for Starting Sex Education in Kindergarten.” PBS NewsHour, May 27, sec. Health. Available at: https://www.pbs.org/newshour/health/spring-fever [Google Scholar]

- DeGue Sarah. 2014. “Preventing Sexual Violence on College Campuses: Lessons from Research and Practice.” Available at: https://www.justice.gov/archives/ovw/page/file/909811/download

- Feigenbaum Rhona, and Weinstein Estelle. 1995. “College Students’ Sexual Attitudes and Behaviors: Implications for Sexuality Education.” Journal of American College Health 44 (3): 112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finken Laura L. 2002. “The Impact of a Human Sexuality Course on Anti-Gay Prejudice.” Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality 14 (1): 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Goldfarb Eva S. 2005. “What Is Comprehensive Sexuality Education Really All About? Perceptions of Students Enrolled in an Undergraduate Human Sexuality Course.” American Journal of Sexuality Education 1 (1). Taylor & Francis Ltd: 85–102. [Google Scholar]

- Goldfarb Eva S., and Lieberman Lisa D.. 2021. “Three Decades of Research: The Case for Comprehensive Sex Education.” Journal of Adolescent Health 68 (1): 13–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttmacher Institute. 2022a. Sex and HIV Education. Available at: https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/sex-and-hiv-education

- Guttmacher Institute. 2022b. Unintended Pregnancy and Abortion in Northern America. Available at: https://www.guttmacher.org/fact-sheet/unintended-pregnancy-and-abortion-northern-america

- Guttmacher Institute. 2022c. Unintended Pregnancy and Abortion. Available at: https://www.guttmacher.org/regions/europe/netherlands#:~:text=In%20the%20Netherlands%20in%202015,Netherlands%20is%20legal%20on%20request

- Henry Dayna S. 2013. “Couple Reports of the Perceived Influences of a College Human Sexuality Course: An Exploratory Study.” Sex Education 13 (5): 509–521. [Google Scholar]

- Khan Khalid S, Kunz Regina, Kleijnen Jos, and Antes Gerd. 2003. “Five Steps to Conducting a Systematic Review.” Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 96 (3): 118–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King Bruce M., Burke Savannah R., and Gates Taylor M.. 2020. “Is There a Gender Difference in US College Students’ Desire for School-Based Sexuality Education?” Sex Education 20 (3): 350–359. [Google Scholar]

- Knoema. 2022. “Netherlands Rape Rate, 2003–2021.” Available at https://knoema.com//atlas/Netherlands/Rape-rate

- Knoema. 2022. “United States of America Rape Rate.” Available at: https://knoema.com//atlas/United-States-of-America/topics/Crime-Statistics/Assaults-Kidnapping-Robbery-Sexual-Rape/Rape-rate

- Lindberg Laura D, and Kantor Leslie M. 2022. “Adolescents’ Receipt of Sex Education in a Nationally Representative Sample, 2011–2019.” Journal of Adolescent Health 70 (2): 290–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg Laura Duberstein, Maddow-Zimet Isaac, and Boonstra Heather. 2016. “Changes in Adolescents’ Receipt of Sex Education, 2006–2013.” Journal of Adolescent Health 58 (6): 621–627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning-Ouellette Amber, and Shikongo-Asino Josephine. 2022. “College-Level Sex Education Courses: A Systematic Literature Review.” American Journal of Sexuality Education. 17(2)2: 176:201. [Google Scholar]

- Noland Ramona M., Bass Martha A., Keathley Rosanne S., and Miller Rowland. 2009. “Is a Little Knowledge a Good Thing? College Students Gain Knowledge, but Knowledge Increase Does Not Equal Attitude Change Regarding Same-Sex Sexual Orientation and Gender Reassignment Surgery in Sexuality Courses.” American Journal of Sexuality Education 4 (2): 139–157. [Google Scholar]

- Olmstead Spencer B., Conrad Kathryn A., and Davis Kayley N.. 2020. “First-Year College Students’ Experiences of a Brief Sexual Health Seminar.” Sex Education 20 (3): 300–315. [Google Scholar]

- Oswalt Sara B., Wagner Laurie M., Eastman-Mueller Heather P., and Nevers Joleen M.. 2015. “Pedagogy and Content in Sexuality Education Courses in US Colleges and Universities.” Sex Education 15 (2): 172–187. [Google Scholar]

- Pettijohn Terry, and Dunlap AV. 2010. “The Effects of a Human Sexuality Course on College Students’ Sexual Attitudes and Perceived Course Outcomes.” Electronic Journal of Human Sexuality 13. Online available at: http://www.ejhs.org/volume13/sexclass.htm [Google Scholar]

- Potter Sharyn J. 2019. “Using Lemon Laws to Curb the Campus Sexual Assault Epidemic.” Contexts 18 (3): 66–67. [Google Scholar]

- Rankin Susan R. 2005. “Campus Climates for Sexual Minorities.” New Directions for Student Services 2005 (111): 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers Anissa, McRee Nick, and Arntz Diana L.. 2009. “Using a College Human Sexuality Course to Combat Homophobia.” Sex Education 9 (3): 211–225. [Google Scholar]

- Rutledge Scott Edward, Siebert Darcy Clay, Chonody Jill, and Killian Michael. 2011. “Information about Human Sexuality: Sources, Satisfaction, and Perceived Knowledge among College Students.” Sex Education 11 (4): 471–487. [Google Scholar]

- Santelli John S., Grilo Stephanie A., Choo Tse-Hwei, Diaz Gloria, Walsh Kate, Wall Melanie, Hirsch Jennifer S., et al. 2018. “Does Sex Education before College Protect Students from Sexual Assault in College?” PLoS ONE 13 (11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0205951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider Madeline, and Hirsch Jennifer S.. 2018. “Comprehensive Sexuality Education as a Primary Prevention Strategy for Sexual Violence Perpetration.” Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 21 (3): 439–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaver Ansleigh. 2021. “Sex Ed 101: A Case for Sex Education as Part of the First-Year Student Experience” BU Well 6 (1): 3. [Google Scholar]

- SIECUS. 2004. “The Guidelines for Comprehensive Sexuality Education.” Available at: https://siecus.org/resources/the-guidelines/. [Google Scholar]

- Synovitz Linda, Herbert Eddie, Kelley R Mark, and Carlson Gerald. 2002. “Sexual Knowledge of College Students in a Southern State: Relationship to Sexuality Education.” American Journal of Health Studies 17 (4): 163–172. [Google Scholar]

- Toews Michelle L., and Yazedjian Ani. 2012. “College Students’ Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behaviors Regarding Sex and Contraceptives.” Journal of Family & Consumer Sciences 104 (3): 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. 2018. “International Technical Guidance on Sexuality Education.” Available at: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/ITGSE_en.pdf

- UNESCO. 2021. “The Journey Towards Comprehensive Sexuality Education: Global Status Report.” Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/in/documentViewer.xhtml?v=2.1.196&id=p::usmarcdef_0000379607&file=/in/rest/annotationSVC/DownloadWatermarkedAttachment/attach_import_821b5e93-a17f-4d08-9cfa-9b2364bce585%3F_%3D379607eng.pdf&locale=en&multi=true&ark=/ark:/48223/pf0000379607/PDF/379607eng.pdf#460_21_CSE_Report.indd%3A.101679%3A220

- Voss Jacqueline, and Kogan Lori. 2001. “Behavioral Impact of a Human Sexuality Course.” Journal of Sex Education and Therapy 26 (2): 122–132. [Google Scholar]

- Warshowsky Hannah, Mosley Della V., Mahar Elizabeth A., and Mintz Laurie. 2020. “Effectiveness of Undergraduate Human Sexuality Courses in Enhancing Women’s Sexual Functioning.” Sex Education 20 (1): 1–16. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2019.1598858 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). 2021. “Violence Against Women.” Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women.

- World Health Organization (WHO). 2002. “Constitution of the World Health Organization. 1946.” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 80 (12): 983. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright Lester W., and Cullen Jenifer M.. 2001. “Reducing College Students’ Homophobia, Erotophobia, and Conservatism Levels Through a Human Sexuality Course.” Journal of Sex Education and Therapy 26 (4): 328–333. [Google Scholar]

- Yamakawa Katherine M., and Williams Elizabeth Nutt. 2001. “Effects of Campus Climate and Attitudes on the Identity Development of Gay, Lesbian and Bisexual College Students.” Modern Psychological Studies 8 (1): 12. [Google Scholar]