Key Points

Question

Is ciprofloxacin, 0.3%, plus fluocinolone acetonide, 0.025%, superior to ciprofloxacin or fluocinolone acetonide alone in treating acute otitis externa?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial including 493 patients, ciprofloxacin plus fluocinolone was not superior to either agent alone for the primary outcome of therapeutic cure. A faster resolution of otalgia, superiority in sustained microbiological response, and superiority in the microbiological outcome were noted with ciprofloxacin plus fluocinolone compared with fluocinolone or ciprofloxacin alone.

Meaning

Ciprofloxacin plus fluocinolone otic solution did not show statistical superiority compared with ciprofloxacin or fluocinolone alone for the primary end point, although the combination showed statistical superiority in many secondary efficacy end points and a good safety profile.

Abstract

Importance

Ciprofloxacin, 0.3%, plus fluocinolone acetonide, 0.025%, otic solution seems to be efficacious and safe in treating acute otitis externa (AOE) compared with ciprofloxacin, 0.3%, or fluocinolone acetonide, 0.025%, otic solution alone.

Objective

To evaluate the superiority of ciprofloxacin, 0.3%, plus fluocinolone acetonide, 0.025%, otic solution compared with ciprofloxacin, 0.3%, or fluocinolone acetonide, 0.025%, otic solution alone in treating AOE.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A phase 3 randomized, double-blind, active-controlled clinical trial was conducted between August 1, 2017, and September 14, 2018, at 36 centers in the US. The study population comprised 493 patients aged 6 months or older with AOE of less than 21 days’ duration with otorrhea, moderate or severe otalgia, and edema, as well as a Brighton grading of II or III (tympanic membrane obscure but without systemic illness). Statistical analysis was performed from November 14, 2018, to February 14, 2019.

Interventions

Participants were randomly assigned to receive ciprofloxacin plus fluocinolone, ciprofloxacin, or fluocinolone twice daily for 7 days and were evaluated on day 1 (visit 1; baseline), days 3 to 4 (visit 2; conducted via telephone), days 8 to 10 (visit 3; end of treatment), and days 15 to 17 (visit 4; test of cure).

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was therapeutic cure (clinical and microbiological) at the end of the treatment period. The principal secondary end point was the time to end of ear pain. Efficacy analyses were conducted in the microbiological intent-to-treat population, clinical intent-to-treat population, and microbiological intent-to-treat population with Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus.

Results

A total of 493 patients (254 female patients [51.5%]; mean [SD] age, 38.2 [23.1] years) were randomized (197 to receive ciprofloxacin plus fluocinolone, 196 to receive ciprofloxacin, and 100 to receive fluocinolone). Therapeutic cure in the modified intent-to-treat population with ciprofloxacin plus fluocinolone (63 of 103 [61.2%]) was statistically comparable to that of ciprofloxacin (49 of 91 [53.8%]; difference in response rate, 7.3%; 95% CI, –6.6% to 21.2%; P = .30) and fluocinolone (20 of 45 [44.4%]; difference in response rate, 16.7%; 95% CI, –0.6% to 34.0%; P = .06) at visit 3 and significantly superior to ciprofloxacin at visit 4 (90 of 103 [87.4%] vs 69 of 91 [75.8%]; difference in response rate, 11.6%; 95% CI, 0.7%-22.4%; P = .04). A statistically faster resolution of otalgia was achieved among patients treated with ciprofloxacin plus fluocinolone (median, 5.0 days [range, 4.2-6.3 days]) vs ciprofloxacin (median, 5.9 days [range, 4.3-7.3 days]; 95% CI, 4.3-7.3 days; P = .002) or fluocinolone (median, 7.7 days [range, 6.7-9.0 days]; 95% CI, 6.7-9.0 days; P < .001). Ciprofloxacin plus fluocinolone demonstrated statistical superiority in sustained microbiological response vs ciprofloxacin (94 of 103 [91.3%] vs 74 of 91 [81.3%]; difference in response rate, 9.9%; 95% CI, 0.3%-19.6%; P = .04) and fluocinolone (34 of 45 [75.6%]; difference in response rate, 15.7%; 95% CI, 2.0%-29.4%; P = .01) and in the microbiological outcome vs fluocinolone by visit 3 (99 of 103 [96.1%] vs 37 of 45 [82.2%]; difference in response rate, 13.9%; 95% CI, 2.1%-25.7%; P = .01) and ciprofloxacin by visit 4 (97 of 103 [94.2%] vs 77 of 91 [84.6%]; difference in response rate, 9.6%; 95% CI, 0.9%-18.2%; P = .02). Fifteen adverse events related to study medications were registered, all of which were mild or moderate.

Conclusions and Relevance

Ciprofloxacin, 0.3%, plus fluocinolone acetonide, 0.025%, otic solution was efficacious and safe in treating AOE but did not demonstrate superiority vs ciprofloxacin, 0.3%, or fluocinolone acetonide, 0.025%, otic solutions alone in the main study end point of therapeutic cure.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03196973

This randomized clinical trial evaluates the superiority of ciprofloxacin, 0.3%, plus fluocinolone acetonide, 0.025%, otic solution compared with ciprofloxacin, 0.3%, or fluocinolone acetonide, 0.025%, otic solution alone in treating acute otitis externa.

Introduction

Otitis externa is an inflammatory condition of the external auditory canal1 that can be acute (most common) or chronic. The estimated incidence of acute otitis externa (AOE) is between 1 in 100 and 1 in 250 of the general population,2,3 and it is a common infection treated by health care professionals.4

Historically, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus were identified as common causative pathogens.5,6 The pathogenesis is multifactorial, with water exposure in the ear canal commonly noted.7 Patients with AOE present with otalgia, tenderness, diffuse ear canal edema, and otorrhea.8 In severe cases, symptoms may result in sleep disturbance and severe discomfort, leading to many health care visits.9,10

In uncomplicated AOE, current guidelines recommend treatment with topical antimicrobial agents with or without anti-inflammatory drugs, risk factor avoidance, and pain management, when required.3,11 Topical antibiotics are the preferred first-line treatment because they can reach high local concentrations in the infected area,1,5 demonstrate a low risk of adverse events (AEs), and minimize the development of antibiotic resistance.12

Topical antibiotics include aminoglycosides (neomycin and gentamicin) or fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin and ofloxacin), with cure rates ranging from 65% to 90%.13 Topical fluoroquinolones are not associated with ototoxic effects and are effective in the presence of a tympanic membrane perforation.12,14 Ciprofloxacin is a second-generation fluoroquinolone antibiotic particularly effective against gram-negative bacteria (including P aeruginosa).5,15

In AOE, the addition of corticosteroids to ototopical antibiotic treatment is believed to enhance the resolution of the inflammatory response and improve associated symptoms.16 Fluocinolone acetonide is a corticosteroid with anti-inflammatory, antipruritic, and vasoconstrictive properties.17 The combination of ciprofloxacin, 0.3%, plus fluocinolone acetonide, 0.025%, has already shown superiority vs ciprofloxacin alone for the treatment of diffuse otitis externa18 and vs ciprofloxacin or fluocinolone acetonide alone for children with acute otitis media with tympanostomy tubes (AOMTs).19 This combination is currently approved to treat AOE and AOMTs in more than 50 countries outside the US and for AOMTs in the US and Canada. The present study was conducted to evaluate the superiority of the combination of ciprofloxacin, 0.3%, plus fluocinolone acetonide, 0.025%, vs ciprofloxacin and fluocinolone acetonide alone to treat AOE.

Methods

Study Design

This phase 3, randomized, double-blind clinical trial was conducted at 36 centers in the US between August 1, 2017, and September 14, 2018. The protocol and informed consent form were reviewed and approved by the Advarra institutional review board. The study was conducted in accordance with the International Council for Harmonization Good Clinical Practice guidance and the Declaration of Helsinki.20 The study results followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline. The trial protocol and statistical analysis plan are available in Supplement 1. Each patient (or patient’s legally authorized representative) provided written informed consent before study initiation.

The study was scheduled across 4 visits: visit 1 (baseline; day 1), visit 2 (telephone visit; days 3-4), visit 3 (end of treatment; days 8-10 or within 2 days of early termination), and visit 4 (test of cure; days 15-17). At visit 1, eligible patients who signed the informed consent form were randomly assigned to the investigational or comparator treatment groups. Demographic information was collected in the case report form at visit 1 for each patient. Medical history, concurrent symptoms and conditions, and concomitant medications were recorded; vital signs were assessed; a sample of ear discharge was collected for microbiological culture; and signs and symptoms of AOE were evaluated. The study medication was supplied, and a staff member instructed patients or caregivers on how to administer it. A diary was provided to the patient or caregiver to record concomitant medications, compliance, and pain severity twice daily (prior to dosing). At visit 2, patients were inquired by telephone about AOE symptoms and, if no improvement was reported, were asked for an onsite visit. At visits 3 and 4, vital signs were assessed, clinical response was evaluated, and, if ear discharge was present, a sample was collected for microbiological evaluation. Used and unused medication was collected at visit 3, and patient diaries were collected at visit 4.

Study Population

Included in the study were patients older than 6 months with AOE of less than 21 days’ duration in at least 1 ear, who presented with otorrhea, moderate or severe otalgia, and edema with a Brighton grading of II or III.21 The Brighton grading system is an algorithm to grade the severity of otitis externa, in which grade II corresponds to the presence of debris in the ear canal and tympanic membrane often obscured by debris and grade III corresponds to a tympanic membrane obscured by edematous ear canal but without systemic illness.

Exclusion criteria included a previous episode of AOE within 4 weeks or more than 1 episode of AOE within 6 months prior to enrollment; existing tympanic membrane perforation; current diagnosis of diabetes, otitis media, or malignant otitis externa; suspected viral or fungal ear infection; unknown or suspected fluoroquinolone and/or corticosteroid hypersensitivity; use of topical or systemic antimicrobial, antifungal, or corticosteroid agents within 1 week preceding study entry; and concurrent use of anti-inflammatory agents.

Treatments

The investigational product was ciprofloxacin, 0.3%, plus fluocinolone acetonide, 0.025%. Comparator drugs were ciprofloxacin, 0.3%, and fluocinolone acetonide, 0.025%. All treatments were sterile otic solutions supplied in blue translucent single-use vials (0.25 mL) with the same characteristics.

Patients were randomized via an interactive web response system to one of the following treatment groups: ciprofloxacin plus fluocinolone, ciprofloxacin, or fluocinolone, in a 2:2:1 ratio. A block randomization algorithm was used.22 To ensure homogeneous representation of age groups, patients were stratified by age at enrollment (<18 or ≥18 years).

Study Outcomes

The primary objective of the study was to demonstrate the superiority of ciprofloxacin plus fluocinolone relative to ciprofloxacin alone and fluocinolone alone by means of the therapeutic cure rate (clinical and microbiological cure) at the end of treatment. Clinical cure was considered achieved if edema, otalgia, and otorrhea were fully resolved (with total signs and symptoms score of 0), with no further requirement of antimicrobial therapy. The total signs and symptoms score is the sum of otalgia, edema, and otorrhea scores, with each of them rated on a scale of 0 to 3 (where 0 indicates absent; 1, mild; 2, moderate; and 3, severe). Patients reported their level of pain before the ear was examined and recorded the intensity of pain twice daily in their diary. Edema and otorrhea were assessed by the investigator through otoscopic examination. Microbiological cure was established when the bacteriologic response was eradication (ie, repeated culture did not show growth of any pathogen) or presumed eradication (ie, no material to culture and an overall clinical outcome of clinical cure or clinical improvement). Microbiological samples were submitted to a central laboratory for analysis. Patients who received rescue medication during the study were considered to have experienced a lack of efficacy.

The principal secondary objective was to show the superiority of ciprofloxacin plus fluocinolone relative to ciprofloxacin alone and fluocinolone alone with respect to the time to end of ear pain, defined as the interval (in days) between the first dose of study medication and the first day (morning or evening) on which the ear pain in the evaluable ear was absent and remained absent until the end of the study without use of analgesics. This time was calculated on the basis of the patient’s diary entries using an age-adjusted pain scale (Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability scale23 for patients younger than 7 years, Wong-Baker FACES Pain Scale24 for patients aged 7-13 years, and visual analogue scale for patients aged ≥13 years) and the investigator’s assessment of otalgia at each visit.

Other secondary end points included (1) sustained microbiological cure; (2) clinical cure at visit 3 and visit 4; (3) microbiological cure at visit 3 and visit 4; (4) therapeutic cure at visit 4; (5) changes in otorrhea, edema, and otalgia at visit 3 and visit 4; and (6) AEs throughout the study. Compliance was assessed by dividing the number of doses the patient took by the number of prescribed doses. Patients were considered compliant if their percentage compliance was between 80% and 120%. Safety was evaluated by recording AEs reported by the patient or the investigator and by the assessment of vital signs.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed from November 14, 2018, to February 14, 2019. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.3 or later (SAS Institute Inc). All P values were from 2-sided tests, and results were deemed statistically significant at P < .05. Efficacy analyses were conducted in the microbiological intent-to-treat (MITT) population, the clinical intent-to-treat (CITT) population, and the MITT population with P aeruginosa and S aureus-(PA/SA) (as per the US Food and Drug Administration’s specific requirement). Safety summaries were based on the safety population. The CITT population included all patients who were randomized. The MITT population included all patients in the CITT population with a positive pathogen microbiological culture at baseline. The MITT-PA/SA population included the MITT subset of patients with Pseudomonas aeruginosa and/or Staphylococcus aureus as pathogens. The safety population included all patients who received at least 1 dose of study medication. Patients with missing efficacy data or indeterminate outcomes were considered to have experienced treatment failure for efficacy analyses.

To test for superiority in the primary efficacy variable (therapeutic cure rate), a 2-sided χ2 test was used. The principal secondary outcome was analyzed using the log-rank test stratified by age. A 2-sided χ2 test was used to analyze secondary efficacy end points.

The rates of patients cured in previous trials ranged between 60% and 70%, and in 2 AOMT comparative studies that tested ciprofloxacin plus fluocinolone, the percentage of patients with P aeruginosa and S aureus who were cured was approximately 50%.19 A therapeutic cure rate of 62% in the ciprofloxacin group was assumed, and a relative increase of 25% in the ciprofloxacin plus fluocinolone group (78%) was considered to demonstrate superiority. Therefore, the required number of patients would be 150 in the ciprofloxacin plus fluocinolone group and in the ciprofloxacin group and 75 in the fluocinolone group. Assuming that 25% of patients would have a negative culture at baseline and a withdrawal rate of 20%, 500 patients were required.

Results

Study Population

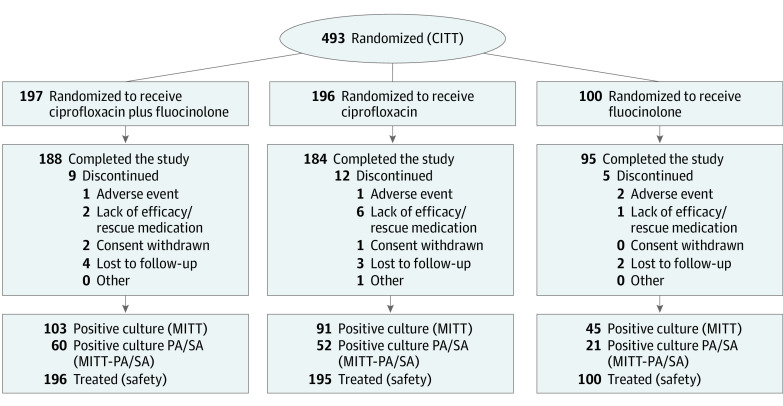

A total of 493 patients were randomized (CITT population); the mean (SD) age in the overall population was 38.2 (23.1) years, 254 (51.5%) were female, and 239 (48.5%) were male. Of these patients, 239 (48.5%) had a positive baseline microbiological culture (MITT population), of whom 133 (27.0%) had a positive culture for P aeruginosa and/or S aureus (MITT-PA/SA population) and 141 (28.6%) had a positive culture for other pathogens (Figure 1; Table 1). Demographic characteristics were similarly distributed among study groups (Table 1).

Figure 1. Participant Flowchart.

CITT indicates clinical intent-to-treat population; MITT, microbiological intent-to-treat population; and MITT-PA/SA, microbiological intent-to-treat population with Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus.

Table 1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Patients in the Clinical Intent-to-Treat Population.

| Characteristic | Patients, No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| CIPRO+FLUO (n = 197) | CIPRO (n = 196) | FLUO (n = 100) | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 37.8 (23.8) | 38.4 (22.6) | 38.7 (22.8) |

| <18 | 56 (28.4) | 57 (29.1) | 29 (29.0) |

| ≥18 | 141 (71.6) | 139 (70.9) | 71 (71.0) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 97 (49.2) | 101 (51.5) | 56 (56.0) |

| Male | 100 (50.8) | 95 (48.5) | 44 (44.0) |

| Race and ethnicity | |||

| African American | 29 (14.7) | 30 (15.3) | 15 (15.0) |

| American Indian or Alaska native | 1 (0.5) | 2 (1.0) | 0 |

| Asian | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 2 (2.0) |

| White | 162 (82.2) | 161 (82.1) | 82 (82.0) |

| Othera | 5 (2.5) | 2 (1.0) | 1 (1.0) |

| Baseline pathogenb | 103 (52.3) | 91 (46.4) | 45 (45.0) |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 37 (18.8) | 33 (16.8) | 16 (16.0) |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 26 (13.2) | 24 (12.2) | 8 (8.0) |

| Other pathogen | 64 (32.5) | 47 (24.0) | 30 (30.0) |

Abbreviations: CIPRO, ciprofloxacin alone; CIPRO+FLUO, ciprofloxacin plus fluocinolone acetonide; FLUO, fluocinolone acetonide alone.

In the CIPRO+FLUO group: 1 Central American patient, 2 Hispanic patients, 1 patient with race and ethnicity not known, and 1 biracial patient; in the CIPRO group: 2 Hispanic patients; in the FLUO group: 1 African American and White patient.

Each patient could have more than 1 pathogen.

Twenty-six patients discontinued the study: 9 of 197 (4.6%) in the ciprofloxacin plus fluocinolone group, 12 of 196 (6.1%) in the ciprofloxacin group, and 5 of 100 (5.0%) in the fluocinolone group (Figure 1). Compliance rates in the CITT population were 96.4% (190 of 197) in the ciprofloxacin plus fluocinolone group, 95.9% (188 of 196) in the ciprofloxacin group, and 97.0% (97 of 100) in the fluocinolone group. Rescue medication was required during the study for 1.5% of patients (3 of 197) in the ciprofloxacin plus fluocinolone group, 8.2% (16 of 196) in the ciprofloxacin group and 4.0% (4 of 100) in the fluocinolone group.

Efficacy Assessments

The therapeutic response at visit 3 in the MITT population was statistically comparable in the ciprofloxacin plus fluocinolone group vs the ciprofloxacin (63 of 103 [61.2%] vs 49 of 91 [53.8%]; difference in response rate, 7.3%; 95% CI, –6.6% to 21.2%; P = .30) and fluocinolone (20 of 45 [44.4%]; difference in response rate, 16.7%; 95% CI, –0.6% to 34.0%; P = .06) groups (Table 2). Results were similar in the MITT-PA/SA and CITT populations.

Table 2. Efficacy Assessments by Therapeutic Response of Patients.

| Population | Patients, No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| CIPRO+FLUO | CIPRO | FLUO | |

| Microbiological intent-to-treat population | |||

| Total No. | 103 | 91 | 45 |

| Visit 3 (primary end point) | |||

| Therapeutic cure | 63 (61.2) | 49 (53.8) | 20 (44.4) |

| Therapeutic failure | 40 (38.8) | 42 (46.2) | 25 (55.6) |

| Difference in response rate (95% CI)a | NA | 7.3 (–6.6 to 21.2) | 16.7 (–0.6 to 34.0) |

| P valueb | NA | .30 | .06 |

| Visit 4 | |||

| Therapeutic cure | 90 (87.4) | 69 (75.8) | 36 (80.0) |

| Therapeutic failure | 13 (12.6) | 22 (24.2) | 9 (20.0) |

| Difference in response rate (95% CI)a | NA | 11.6 (0.7 to 22.4) | 7.4 (–6.0 to 20.7) |

| P valueb | NA | .04 | .25 |

| Clinical intent-to-treat population | |||

| Total No. | 196 | 196 | 100 |

| Visit 3 | |||

| Therapeutic cure | 107 (54.3) | 94 (48.0) | 45 (45.0) |

| Therapeutic failure | 90 (45.7) | 102 (52.0) | 55 (55.0) |

| Difference in response rate (95% CI)a | NA | 6.4 (–3.5 to 16.2) | 9.3 (–2.7 to 21.3) |

| P valueb | NA | .21 | .13 |

| Visit 4 | |||

| Therapeutic cure | 175 (88.8) | 152 (77.6) | 82 (82.0) |

| Therapeutic failure | 22 (11.2) | 44 (22.4) | 18 (18.0) |

| Difference in response rate (95% CI)a | NA | 11.3 (4.0 to 18.6) | 6.8 (–1.9 to 16.6) |

| P valueb | NA | .003 | .10 |

| Sustained microbiological outcome in microbiological intent-to-treat populationc | |||

| Total No. | 103 | 91 | 45 |

| Therapeutic cure | 94 (91.3) | 74 (81.3) | 34 (75.6) |

| Therapeutic failure | 9 (8.7) | 17 (18.7) | 11 (24.4) |

| Difference in response rate (95% CI)a | NA | 9.9 (0.3 to 19.6) | 15.7 (2.0 to 29.4) |

| P valueb | NA | .04 | .01 |

Abbreviations: CIPRO, ciprofloxacin alone; CIPRO+FLUO, ciprofloxacin plus fluocinolone acetonide; FLUO, fluocinolone acetonide alone; NA, not applicable.

Calculated as response rate for combined treatment–response rate for individual component.

Calculated using the Pearson χ2 test for independence between the combined treatment and each individual component. If the assumptions of the χ2 test were not met, the P value was calculated using the Fisher exact test.

Sustained microbiological cure is achieved when there is a response of eradication or presumed eradication at both visits 3 and 4. Patients who discontinued because of lack of efficacy or rescue medication use were considered to have experienced treatment failure.

At visit 4, the therapeutic response was significantly superior in the ciprofloxacin plus fluocinolone group compared with the ciprofloxacin group (90 of 103 [87.4%] vs 69 of 91 [75.8%]; difference in response rate, 11.6%; 95% CI, 0.7%-22.4%; P = .04) but not with the fluocinolone group (36 of 45 [80.0%]; difference in response rate, 7.4%; 95% CI, –6.0% to 20.7%; P = .25) (Table 2). Similar results were observed in the CITT population, and no statistically significant difference was reached in the MITT-PA/SA population.

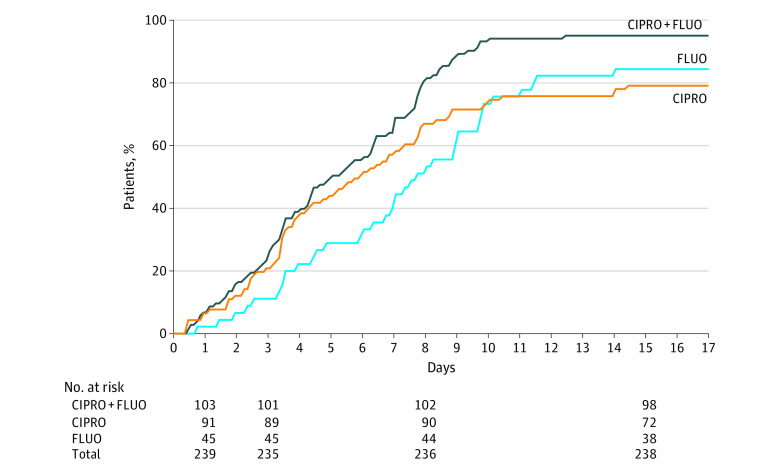

Otalgia disappeared significantly faster in patients treated with ciprofloxacin plus fluocinolone (median, 5.0 days [range, 4.2-6.3 days]) compared with those treated with ciprofloxacin (median, 5.9 days [range, 4.3-7.3 days]; 95% CI, 4.3-7.3 days; P = .002) or fluocinolone (median, 7.7 days [range, 6.7-9.0 days]; 95% CI, 6.7-9.0 days; P < .001) in the MITT population (Figure 2). The median time to end of ear pain was 5.0 days (range, 4.2-6.3 days) in the ciprofloxacin plus fluocinolone group, 5.9 days (range, 4.3-7.3 days) in the ciprofloxacin group, and 7.7 days (range, 6.7-9.0 days) in the fluocinolone group (Figure 2). A significantly lower median time to end of ear pain was also observed in the ciprofloxacin plus fluocinolone group (5.9 days; range, 4.9-6.4 days) vs the ciprofloxacin (6.9 days; range, 5.9-7.9 days; P < .001) and fluocinolone (7.6 days; range, 6.0-8.5 days; P = .01) groups in the CITT population and vs the fluocinolone group (7.5 days; range, 4.5-11.5 days; P = .01) in the MITT-PA/SA population.

Figure 2. Time to End of Ear Pain in the Microbiological Intent-to-Treat Population.

Kaplan-Meier graphic showing the time to end of ear pain in each treatment group and the number of patients at risk at each study visit. CIPRO indicates ciprofloxacin alone; CIPRO+FLUO, ciprofloxacin plus fluocinolone acetonide; and FLUO, fluocinolone acetonide alone.

In the MITT population, significantly higher rates of sustained microbiological cure were achieved in the ciprofloxacin plus fluocinolone group (94 of 103 [91.3%]) vs the ciprofloxacin group (74 of 91 [81.3%]; difference in response rate, 9.9%; 95% CI, 0.3%-19.6%; P = .04) and the fluocinolone group (34 of 45 [75.6%]; difference in response rate, 15.7%; 95% CI, 2.0%-29.4%; P = .01) (Table 2). The proportion of patients with a favorable microbiological outcome was significantly higher in the ciprofloxacin plus fluocinolone group vs the fluocinolone group at visit 3 (99 of 103 [96.1%] vs 37 of 45 [82.2%]; difference in response rate, 13.9%; 95% CI, 2.1%-25.7%; P = .01) and vs the ciprofloxacin group at visit 4 (97 of 103 [94.2%] vs 77 of 91 [84.6%]; difference in response rate, 9.6%; 95% CI, 0.9%-18.2%; P = .02).

No significant differences between study groups were observed for the clinical cure at visit 3 in the MITT population (63 of 103 [61.2%] for the ciprofloxacin plus fluocinolone group, 50 of 91 [54.9%] for the ciprofloxacin group, and 20 of 45 [44.4%] for the fluocinolone group). At visit 4, ciprofloxacin plus fluocinolone was statistically comparable to ciprofloxacin alone (90 of 103 [87.4%] vs 70 of 91 [76.9%]; difference in response rate, 10.5%; 95% CI, –0.3% to 21.2%; P = .06) and fluocinolone alone (36 of 45 [80.0%]; difference in response rate, 7.4%; 95% CI, –6.0% to 20.7%; P = .25). The combination of ciprofloxacin plus fluocinolone was statistically superior to ciprofloxacin alone at visit 4 in the CITT population (176 of 197 [89.3%] vs 156 of 196 [79.6%]; difference in response rate, 9.7%; 95% CI, 2.6%-16.8%; P = .008).

The proportion of patients whose otorrhea resolved was significantly higher in the ciprofloxacin plus fluocinolone group compared with the ciprofloxacin group at visit 3 in the MITT and CITT populations. The changes in otalgia, when assessed by the investigator, were significantly better in the ciprofloxacin plus fluocinolone group compared with the fluocinolone group at visit 3. For the change in otalgia scores, the patients treated with the combination of ciprofloxacin plus fluocinolone had significantly higher scores than patients in both comparator groups at visit 3 and patients who received ciprofloxacin at visit 4 in the MITT population (eTable in Supplement 2). In the CITT population, all comparisons between groups with regard to otalgia were significantly better with ciprofloxacin plus fluocinolone. No significant changes between groups were seen for edema at either visit in the populations assessed.

Safety Assessment

A total of 15 AEs related to study treatments were registered in the overall population: 6 AEs among 6 patients treated with ciprofloxacin plus fluocinolone and 9 AEs among 5 patients treated with ciprofloxacin. All AEs were considered mild or moderate and resolved before the end of the study (Table 3). Only 1 serious AE occurred during the study (an acute psychotic episode), and it was considered unrelated to the study medication.

Table 3. Related Adverse Events Registered in the Safety Population.

| Characteristic | Patients, No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| CIPRO+FLUO (n = 196) | CIPRO (n = 195) | FLUO (n = 100) | |

| Patients with at least 1 adverse eventa | 6 (3.1) | 5 (2.6) | 0 |

| Related adverse events | 6 (3.1) | 9 (4.6) | 0 |

| Otic events | |||

| Cerumen impaction | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 0 |

| Ear pruritus | 0 | 2 (1.0) | 0 |

| Application site pain | 4 (2.0) | 0 | 0 |

| Fungal ear infection | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 0 |

| Nonotic events | |||

| Nausea | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 0 |

| Dizziness | 0 | 2 (1.0) | 0 |

| Headache | 0 | 2 (1.0) | 0 |

| Lethargy | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 0 |

Abbreviations: CIPRO, ciprofloxacin alone; CIPRO+FLUO, ciprofloxacin plus fluocinolone acetonide; FLUO, fluocinolone acetonide alone.

Three patients in the CIPRO group had more than 1 related adverse event.

Discussion

In this study, we expected to show that the combination of ciprofloxacin, 0.3%, plus fluocinolone acetonide, 0.025%, was associated with higher rates of therapeutic cure, significantly faster cessation of ear pain, a significantly better microbiological outcome, and a good safety profile. For the therapeutic cure rate, ciprofloxacin plus fluocinolone did not demonstrate statistical superiority compared with ciprofloxacin or fluocinolone alone at the end of treatment, although significant differences were reached at the test of cure compared with ciprofloxacin treatment. This discrepancy is thought to be related to the limitation in the total study population for statistical analysis because almost half the sample size was not included in the MITT population. Nevertheless, the combination treatment showed statistical superiority for many efficacy end points.

Pain, the most relevant symptom for patients with AOE, disappeared sooner with ciprofloxacin plus fluocinolone vs ciprofloxacin or fluocinolone alone for the CITT population, which included all patients but also patients from other study populations. In addition, this better pain resolution was observed by both the investigators (at study visits) and the patients (by using a diary for self-assessment), which gives high consistency to the pain resolution pattern. The beneficial effect on pain relief of combining an antibiotic with a corticosteroid has already been described.9,25

Microbiological outcomes clearly showed the superior efficacy of the ciprofloxacin plus fluocinolone combination compared with ciprofloxacin or fluocinolone alone. The significantly higher proportion of patients in the MITT population with sustained microbiological cure in the ciprofloxacin plus fluocinolone group (91.3%) compared with both the ciprofloxacin (81.3%) and fluocinolone (75.6%) groups supports the enduring efficacy of the combination compared with the components alone. At visit 3, ciprofloxacin plus fluocinolone showed statistical superiority vs ciprofloxacin alone and fluocinolone alone in eradicating P aeruginosa and S aureus in the MITT-PA/SA population, which was unexpected owing to the low number of patients in this population. When the microbiological outcome was analyzed by isolated pathogen, higher eradication rates were observed with ciprofloxacin plus fluocinolone compared with ciprofloxacin alone and fluocinolone alone at visit 3 for P aeruginosa, S aureus, Turicella otitidis, and other pathogens, with similar results observed at visit 4.

Clinical cure, restrictively defined as the full disappearance of all assessed symptoms (otorrhea, otalgia, and edema) only achieved statistical significance in the ciprofloxacin plus fluocinolone group compared with ciprofloxacin in the CITT population at visit 4. Although otorrhea and otalgia had a higher rate of resolution in the ciprofloxacin plus fluocinolone group, no significant change in edema was seen between groups at either visit in the populations assessed. Edema is the most subjective symptom to be measured by the physician and also shows a slow resolution process in AOE owing to the anatomical structure of the external auditory canal. Therefore, the contribution of edema resolution to the clinical outcome could have had a negative effect when the combined clinical variable was assessed. An exploratory analysis of the clinical data without considering edema showed statistical differences in therapeutic response in favor of ciprofloxacin plus fluocinolone (at visit 3: 76 of 103 [73.8%] with ciprofloxacin plus fluocinolone vs 54 of 91 [59.3%] with ciprofloxacin; P = .03; and vs 24 of 45 [53.3%] with fluocinolone; P = .01).

Overall, the results in the CITT population were similar to those in the MITT population but with a higher level of significance. The MITT and CITT populations more closely resemble the situation in daily clinical practice, demonstrating the efficacy of ciprofloxacin plus fluocinolone in a realistic treatment setting. The higher efficacy of the combination was also evident by the lower use of rescue medication in the ciprofloxacin plus fluocinolone group (1.5%) compared with the ciprofloxacin group (8.2%) or the fluocinolone groups (4%). Efficacy results are in line with those of previous studies in which the addition of corticosteroids to ototopical antibiotics was efficacious.26,27,28 Few AEs were reported in all study groups, generally mild or moderate, and not related to study medication, supporting the favorable safety profile of the combination of ciprofloxacin and fluocinolone acetonide, as previously shown.18,19

Limitations

This study has some limitations. The lower than anticipated number of patients with a positive microbiological culture at baseline resulted in fewer evaluable patients in the MITT and MITT-PA/SA populations. However, the CITT population still included a high number of patients, which is the population most representative of daily practice.

Conclusions

In this randomized clinical study, ciprofloxacin, 0.3%, plus fluocinolone acetonide, 0.025%, otic solution was efficacious and safe in treating AOE but did not demonstrate superiority vs ciprofloxacin, 0.3%, or fluocinolone acetonide, 0.025%, otic solutions alone in the main study end point of therapeutic cure. However, the findings suggest the benefits of combining the antibiotic ciprofloxacin and the corticosteroid fluocinolone acetonide to better manage patients with AOE, with regard to both the bacterial infection and the typical disease signs and symptoms.

Trial Protocol and Statistical Analysis Plan

eTable. Clinical Signs and Symptoms at Visit 3 in the MITT Population

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Sander R. Otitis externa: a practical guide to treatment and prevention. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63(5):927-936, 941-942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guthrie RM, Bailey BJ, Witsell DL, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of acute otitis externa: an interdisciplinary update: introduction. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1999;108(2 suppl):2-18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenfeld RM, Brown L, Cannon CR, et al. ; American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery Foundation . Clinical practice guideline: acute otitis externa. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;134(4)(suppl):S4-S23. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2006.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaushik V, Malik T, Saeed SR. Interventions for acute otitis externa. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(1):CD004740. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004740.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roland PS, Stroman DW. Microbiology of acute otitis externa. Laryngoscope. 2002;112(7, pt 1):1166-1177. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200207000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark WB, Brook I, Bianki D, Thompson DH. Microbiology of otitis externa. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;116(1):23-25. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(97)70346-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Osguthorpe JD, Nielsen DR. Otitis externa: review and clinical update. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74(9):1510-1516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hui CPS; Canadian Paediatric Society, Infectious Diseases and Immunization Committee . Acute otitis externa. Paediatr Child Health. 2013;18(2):96-101. doi: 10.1093/pch/18.2.96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Balch G, Heal C, Cervin A, Gunnarsson R. Oral corticosteroids for painful acute otitis externa (swimmer’s ear): a triple-blind randomised controlled trial. Aust J Gen Pract. 2019;48(8):565-572. doi: 10.31128/AJGP-12-18-4795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Asperen IA, de Rover CM, Schijven JF, et al. Risk of otitis externa after swimming in recreational fresh water lakes containing Pseudomonas aeruginosa. BMJ. 1995;311(7017):1407-1410. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7017.1407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenfeld RM, Schwartz SR, Cannon CR, et al. Clinical practice guideline: acute otitis externa. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;150(1)(suppl):S1-S24. doi: 10.1177/0194599813514365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hannley MT, Denneny JC III, Holzer SS. Use of ototopical antibiotics in treating 3 common ear diseases. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;122(6):934-940. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2000.107813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenfeld RM, Singer M, Wasserman JM, Stinnett SS. Systematic review of topical antimicrobial therapy for acute otitis externa. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;134(4)(suppl):S24-S48. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2006.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Claes J, Govaerts PJ, Van de Heyning PH, Peeters S. Lack of ciprofloxacin ototoxicity after repeated ototopical application. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35(5):1014-1016. doi: 10.1128/AAC.35.5.1014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mösges R, Nematian-Samani M, Eichel A. Treatment of acute otitis externa with ciprofloxacin otic 0.2% antibiotic ear solution. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2011;7:325-336. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S6769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schaefer P, Baugh RF. Acute otitis externa: an update. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86(11):1055-1061. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pradhan M, Singh D, Murthy SN, Singh MR. Design, characterization and skin permeating potential of fluocinolone acetonide loaded nanostructured lipid carriers for topical treatment of psoriasis. Steroids. 2015;101:56-63. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2015.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lorente J, Sabater F, Rivas MP, Fuste J, Risco J, Gómez M. Ciprofloxacin plus fluocinolone acetonide versus ciprofloxacin alone in the treatment of diffuse otitis externa. J Laryngol Otol. 2014;128(7):591-598. doi: 10.1017/S0022215114001157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spektor Z, Pumarola F, Ismail K, et al. Efficacy and safety of ciprofloxacin plus fluocinolone in otitis media with tympanostomy tubes in pediatric patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;143(4):341-349. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2016.3537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Medical Association . World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Diabetes Association . Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2016 abridged for primary care providers. Clin Diabetes. 2016;34(1):3-21. doi: 10.2337/diaclin.34.1.3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matts JP, Lachin JM. Properties of permuted-block randomization in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1988;9(4):327-344. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(88)90047-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Merkel SI, Voepel-Lewis T, Shayevitz JR, Malviya S. The FLACC: a behavioral scale for scoring postoperative pain in young children. Pediatr Nurs. 1997;23(3):293-297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garra G, Singer AJ, Taira BR, et al. Validation of the Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale in pediatric emergency department patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(1):50-54. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00620.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wall GM, Stroman DW, Roland PS, Dohar J. Ciprofloxacin 0.3%/dexamethasone 0.1% sterile otic suspension for the topical treatment of ear infections: a review of the literature. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28(2):141-144. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31818b0c9c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pistorius B, Westberry K, Drehobl M, et al. Prospective, randomized, comparative trial of ciprofloxacin otic drops, with or without hydrocortisone otic suspention in the treatment of acute diffuse otitis externa. Infect Dis Clin Pract. 1999;8(8):387-395. doi: 10.1097/00019048-199911000-00009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mösges R, Schröder T, Baues CM, Şahin K. Dexamethasone phosphate in antibiotic ear drops for the treatment of acute bacterial otitis externa. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24(8):2339-2347. doi: 10.1185/03007990802285086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abelardo E, Pope L, Rajkumar K, Greenwood R, Nunez DA. A double-blind randomised clinical trial of the treatment of otitis externa using topical steroid alone versus topical steroid-antibiotic therapy. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;266(1):41-45. doi: 10.1007/s00405-008-0712-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol and Statistical Analysis Plan

eTable. Clinical Signs and Symptoms at Visit 3 in the MITT Population

Data Sharing Statement