Abstract

The U16 small nucleolar RNA (snoRNA) is encoded by the third intron of the L1 (L4, according to the novel nomenclature) ribosomal protein gene of Xenopus laevis and originates from processing of the pre-mRNA in which it resides. The U16 snoRNA belongs to the box C/D snoRNA family, whose members are known to assemble in ribonucleoprotein particles (snoRNPs) containing the protein fibrillarin. We have utilized U16 snoRNA in order to characterize the factors that interact with the conserved elements common to the other members of the box C/D class. In this study, we have analyzed the in vivo assembly of U16 snoRNP particles in X. laevis oocytes and identified the proteins which interact with the RNA by label transfer after UV cross-linking. This analysis revealed two proteins, of 40- and 68-kDa apparent molecular size, which require intact boxes C and D together with the conserved 5′,3′-terminal stem for binding. Immunoprecipitation experiments showed that the p40 protein corresponds to fibrillarin, indicating that this protein is intimately associated with the RNA. We propose that fibrillarin and p68 represent the RNA-binding factors common to box C/D snoRNPs and that both proteins are essential for the assembly of snoRNP particles and the stabilization of the snoRNA.

One of the most interesting recent findings related to ribosome biogenesis has been the identification of a large number of small RNAs localized in the nucleolus (snoRNAs). So far, more than 60 snoRNAs have been identified in vertebrates (17), and more than 30 have been identified in yeast (2). The total number of snoRNAs is not known, but it is likely to be close to 200 (33, 38). These snoRNAs, with the exception of the mitochondrial RNA processing (MRP) species (38), can be grouped into two major families on the basis of conserved structural and sequence elements. The first group includes molecules referred to as box C/D snoRNAs, whereas the second one comprises the species belonging to the box H/ACA family (2, 15).

The two families differ in many aspects. The box C/D snoRNAs are functionally heterogeneous. Most of them function as antisense RNAs in site-specific ribose methylation of the pre-rRNA (1, 10, 17, 26); a minority have been shown to play a direct role in pre-rRNA processing in both yeast and metazoan cells (11, 21). The box C/D snoRNAs play their role by means of unusually long (up to 21 contiguous nucleotides) regions of complementarity to highly conserved sequences of 28S and 18S rRNAs (1). In contrast, several members of the H/ACA RNA family have been shown to direct site-specific isomerization of uridines into pseudouridines and to display shorter regions of complementarity to rRNA (14, 24). Mutational analysis suggests that H/ACA snoRNAs can also play a role as antisense RNAs by base pairing with complementary regions on rRNA (15, 24).

Another difference between the two families can be seen by comparison of secondary structures. A Y-shaped motif, where a 5′,3′-terminal stem adjoins the C and D conserved elements, has been proposed for many box C/D snoRNAs (16, 26, 40, 42), whereas box H/ACA snoRNAs have been proposed to fold into two conserved hairpin structures connected by a single-stranded hinge region, followed by a short 3′ tail (15).

Despite these differences, analogies have been found in the roles played by the conserved box elements. Mutational analysis and competition experiments indicated that C/D and H/ACA boxes are required both for processing and stable accumulation of the mature snoRNA, suggesting that they represent binding sites for specific trans-acting factors (2, 3, 8, 15, 16, 28, 36, 41).

All snoRNAs are associated with proteins to form specific ribonucleoparticles (snoRNPs). The study of these particles began only recently, and so far, very few aspects of their structure and biosynthesis have been clarified. The only detailed analysis performed was on the mammalian U3 (19) and the yeast snR30 (20) snoRNPs. Of the identified components, a few appear to be more general factors: fibrillarin, which was shown to be associated with C/D snoRNPs (3, 4, 8, 13, 28, 31, 39), and the nucleolar protein GAR1, which was found associated with H/ACA snoRNAs in yeast (20). Just as the study of small nuclear RNP (snRNP) particles was crucial to the understanding of the splicing process, a detailed structural and functional analysis of snoRNP particles will be essential to elucidate the complex process of ribosome biosynthesis.

In this study, we have analyzed the snoRNP assembly of wild-type and mutant U16 snoRNAs by following the kinetics of complex formation in the in vivo system of the Xenopus laevis oocyte. By a UV cross-linking technique, we have identified two proteins, of 40- and 68-kDa apparent molecular mass, which require intact boxes C and D together with the terminal stem for their binding. The 40-kDa species is specifically recognized by fibrillarin antibodies, indicating that this protein is intimately associated with the RNA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Oligonucleotides.

The following oligonucleotides were used for obtaining the templates for in vitro transcription: B5 (TAATACGACTCACTATAGGCTTGCTATGATGTCGTAA), γU16 (TTTTTGCTCAGAACGCGA), B7 (TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCTTGCTACAATGTCGTAAT), γU16D (TTTTTGCTGGTAACGCGATAT), U16 stem (AAAAATCAGAACGCGATA), FW22 (TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGGTCGATATGATGAGTTCCAC), and Ale2 (CCAAGCTTAATCAGAACTTCCAC). The underlined sequence represents the T7 promoter (23).

Plasmids and templates for RNA transcription.

The following templates were obtained by PCR amplification of plasmid 003 (12) with the oligonucleotides indicated in parentheses: U16108 (B5 and γU16), bC (B7 and γU16), bD (B5 and γU16D), and stemM (B5 and U16 stem). Δ2 mutant was obtained from the corresponding mutant plasmid described by Prislei et al. (30) by PCR amplification with the B5 and γU16 oligonucleotides. The template used for T7 transcription of U6 snRNA, kindly provided by E. Lund, was obtained by PCR amplification of the X. laevis U6 gene (32); U3 snoRNA was obtained by SP6 transcription of a PCR template kindly provided by M. P. Terns (35). The template for U18 snoRNA was obtained by PCR on plasmid 00234 (6) with oligonucleotides FW22 and Ale2.

In vitro transcription and oocyte microinjection.

RNA substrates were synthesized in vitro (22) in the presence of 30 μCi of [α-32P]UTP (800 Ci/mmol) and 25 μM UTP. After transcription, the RNA was gel purified, phenol extracted, and precipitated with ethanol in the presence of 10 μg of Escherichia coli tRNA. For oocyte microinjection, 32P-labelled transcripts were dissolved in bidistilled water at a concentration of 0.75 pmol/μl, and 9.2 nl was injected into germinal vesicles of stage VI oocytes. In vitro transcription of cold RNAs was performed in the presence of 500 μM UTP. For competition experiments, 32P-labelled U16 snoRNA was coinjected with a 100× molar excess of U3 or U6 cold RNAs. After 2 h of incubation, nuclei were dissected and UV cross-linking analysis was performed as described below.

RNA and snoRNP particle analysis.

After injection of 32P-labelled RNAs, the oocytes were incubated at 19°C and 10 nuclei were manually isolated each time. One nucleus was used for RNA analysis. Disruption and digestion of the nucleus were carried out in the presence of 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 0.3 M sodium acetate (pH 5.5), 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.6), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM NaCl, and 2 mg of proteinase K per ml. RNA was then extracted with phenol-chloroform and analyzed on a 6% polyacrylamide–7 M urea gel. After disruption, three nuclei from the same sample were directly loaded onto a native 4% polyacrylamide gel (acrylamide-to-bisacrylamide ratio, 60:1) for snoRNP particle analysis. The remaining six nuclei were used for the analysis of UV cross-linked proteins.

UV cross-linking analysis.

Isolated nuclei injected with 32P-labelled transcripts were exposed to an energy of 600 mJ/cm2 under UV light (254-nm wavelength) in a Spectrolinker XL-1000 apparatus to achieve cross-linking of RNA-protein complexes. These complexes were then treated with 10 μg of RNase A per ml, 1,000 U of RNase T1 per ml, and 14 U of RNase V1 per ml for 15 min at 37°C and for 15 min at RT. The samples were treated with 2% SDS–62.5 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8)–100 mM dithiothreitol–10% glycerol–0.05% bromophenol blue and loaded onto SDS–13% polyacrylamide gels. The proteins were visualized by autoradiography.

Immunoprecipitation.

Antifibrillarin serum (20 μl) or preimmune antiserum was coupled initially to 3 mg of preswollen protein A-Sepharose (Pharmacia) in IPP 200 buffer (40 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 200 mM NaCl, 0.05% Nonidet P-40) in the presence of 10 μg of tRNA and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Isolated nuclei injected with 32P-labelled RNAs were disrupted in IPP 200, with the final NaCl concentration adjusted to 400 mM. Following centrifugation for 10 min (13,000 rpm at 4°C in an Eppendorf centrifuge), the cleared extracts were added to antibody-coupled protein-A Sepharose in the presence of 80 U of RNase inhibitor (Amersham) per ml in a final volume of 500 μl and the incubation was carried out for 2 h at 4°C, with constant mixing (27, 39). Washes were performed in IPP 200 buffer. The samples were digested with proteinase K (0.5 mg/ml), and the recovered RNA was analyzed on a 6% polyacrylamide–urea gel. Immunoprecipitation of cross-linked proteins was carried out by the same procedure on UV cross-linked nuclei after digestion with RNases (see UV Cross-Linking Analysis). For supershift analysis, five 32P-labelled U16-injected nuclei were disrupted and incubated with monoclonal antibodies against fibrillarin (72B9) or with preimmune immunoglobulin G for 1 h at 4°C with stirring; the samples were then directly loaded onto a native 4% polyacrylamide gel. Monoclonal antibodies 72B9 and antifibrillarin sera against 34-kDa Xenopus fibrillarin (18) were kindly provided by M. Caizergues-Ferrer.

RESULTS

In vivo assembly of snoRNP complexes.

We previously reported that stable and correctly processed U16 snoRNA is produced in X. laevis oocytes when they are microinjected with an in vitro-transcribed pre-U16 snoRNA containing 5′ and 3′ trailer sequences (7–9). In the present study, we utilized the same approach to analyze the kinetics of U16 snoRNP particle formation. The microinjected substrate was U16 snoRNA with two extra G residues at the 5′ end and an extension of three nucleotides (A residues) at the 3′ end. This 108-nucleotide-long RNA is converted into the trimmed form, which is 103 nucleotides long, by endogenous exonucleolytic activity and stably accumulates with time. In a typical experiment, 32P-labelled snoRNA was injected into the germinal vesicle of X. laevis oocytes, and for each incubation time, nuclei were manually dissected from the cytoplasm and utilized for (i) analysis of nuclear RNA, (ii) electrophoretic mobility shift assay of the complexes formed on the microinjected labelled RNA, and (iii) identification of RNA-binding proteins by label transfer after UV cross-linking.

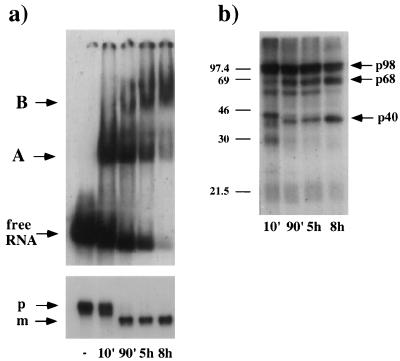

Figure 1a shows the kinetics of U16 snoRNA complex formation. Two major complexes, referred to as A and B, are visualized. Complex A is already visible at very short incubation times (2 to 10 min), while significant accumulation of complex B starts later; it is the major complex that persists after 8 h of incubation (lane 8h). Analysis performed over 24 h showed that complex B stably accumulates, even at such prolonged incubations (data not shown). The profile indicates that the rapidly associating complex A is subsequently replaced by complex B. As a control, protease treatment of samples at different incubation times resulted in the disappearance of both complexes and the release of free RNA (data not shown).

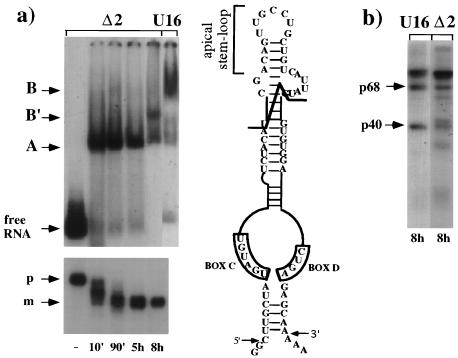

FIG. 1.

U16 snoRNP analysis. (a) In vitro-transcribed 32P-labelled U16 transcript was injected into the nuclei of X. laevis oocytes and incubated for the times indicated below. Purified nuclei, disrupted by pipetting, were directly loaded on a native 4% acrylamide gel. The bands corresponding to A and B complexes are indicated together with the free RNA. The lower panel shows the electrophoretic analysis on a 6% polyacrylamide–7 M urea gel of the RNA extracted at the corresponding time points. The 108-nucleotide-long injected precursor (p) U16 RNA and the 103-nucleotide-long mature (m) U16 snoRNA are indicated. (b) Proteins UV cross-linked to 32P-labelled U16 transcript. Samples were subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis on a 13% polyacrylamide gel. The 40-, 68-, and 98-kDa proteins are indicated by arrows. Protein molecular weight markers (in thousands) are shown at the side of the gel.

The parallel RNA analysis is shown in the lower part of Fig. 1a. Fifty percent of input RNA is found in the trimmed form after 90 min, and this amount remains stable over 8 h. From this and other experiments, it can be calculated that a single oocyte is able to assemble into stable particles with approximately 2 to 4 fmol of box C/D snoRNA. The difference in the lengths of precursor and mature RNAs is not sufficient to account for the differential mobilities of the A and B complexes, suggesting that the two complexes have different protein compositions.

Figure 1b shows the pattern of the proteins directly interacting with 32P-labelled U16, identified by label transfer after UV cross-linking. At short incubations (10 min), approximately 10 proteins, with molecular masses ranging from 20.5 to 98 kDa, are detected. After 8 h, three major proteins, with apparent molecular masses of 40, 68, and 98 (a doublet) kDa, remain bound to the snoRNA, and their presence parallels the formation of complex B. These data indicate that, soon after the injection, the majority of input RNA is associated with a wide range of factors, presumably abundant nuclear proteins with low binding specificity, and that subsequently, these interactions are replaced by more specific ones.

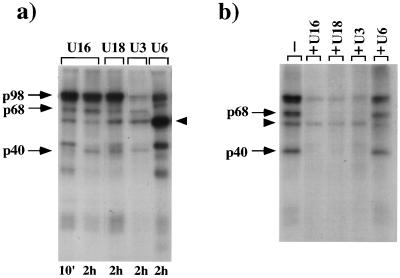

UV cross-linking analysis on different RNA substrates.

The specificity of the U16 protein pattern was analyzed on different RNA substrates containing (U18 and U3) or not containing (U6) the conserved boxes C and D. A p98 signal is found with all the RNAs, while the p40 and p68 proteins are detected on U18 and U3 snoRNAs and are absent from U6 snRNA (Fig. 2a). The U6-specific pattern shows a major UV cross-linked protein of approximately 50 kDa (arrowhead). Previous UV cross-linking analysis in X. laevis oocytes showed that the 50-kDa band corresponded to the La protein (34). This protein is known to have predominant nuclear localization and to be associated with nascent RNA polymerase III transcripts through their 3′ oligourydilate stretch (29). Immunoprecipitation with La protein antibodies (data not shown) demonstrated that the La protein is also bound to U16 snoRNA (arrowhead); this interaction occurs at short incubation times and is progressively lost (Fig. 1b), indicating that La is not part of the snoRNP-specific particle.

FIG. 2.

UV cross-linking and competition analyses with other substrates. (a) Gel electrophoresis analysis of the proteins UV cross-linked in vivo to 32P-labelled U16, U18, U3, and U6 RNAs. Incubation times are indicated below. (b) 32P-labelled U16 snoRNA was microinjected alone (lane −) or with a 100-fold molar excess of cold competitor RNAs: U16 snoRNA (lane +U16), U18 snoRNA (lane +U18), U3 snoRNA (lane +U3), or U6 snRNA (lane +U6). The incubation was allowed to proceed for 2 h, and UV cross-linked proteins were resolved on a 13% polyacrylamide denaturing gel. In both panels, the 40-, 68-, and 98-kDa proteins are indicated by arrows, while the La protein is indicated by an arrowhead.

Competition experiments, in which excesses of cold competitor U16, U18, U3, and U6 RNAs were coinjected with 32P-labelled U16 snoRNA, indicated that all C/D box snoRNAs specifically compete very efficiently for the binding of the p68 and p40 proteins and only partially for the p98 signal, while U6 competes only for the La protein (Fig. 2b).

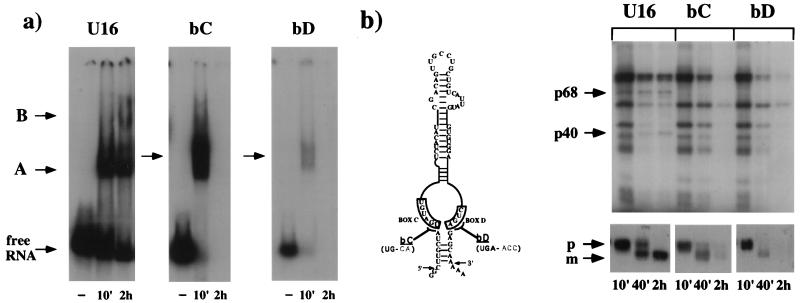

Assembly of RNP complexes on U16 mutant derivatives.

We further addressed the question of whether the binding of p40 and p68 proteins was dependent on the presence of the boxes C and D and/or on other structural elements. It is known that most of the components of the box C/D family, besides the conserved elements, have a Y-shaped secondary-structure motif in which a terminal stem adjoins the C and D boxes (16, 25, 40, 42). For this reason, a collection of U16 mutant derivatives were analyzed for their ability to assemble RNP complexes in vivo, for the resultant pattern of UV cross-linked proteins, and for RNA stability.

The first mutants tested were bC and bD RNAs, which have two- and three-base substitutions in boxes C and D, respectively (Fig. 3b). These mutants were previously shown to affect both processing and stability of the snoRNA (8). Figure 3a shows the band shift analysis performed with these mutants; bC and bD RNAs do not accumulate stable complexes, only a smeared band at short incubation times. This finding corresponds perfectly with the instability of the RNA, which at 2 h is completely degraded (Fig. 3b, lower panel). UV cross-linking analysis reveals that, at incubation times when RNA is not yet degraded (lanes 10 and 40 min), the p40 and p68 proteins are absent from both mutants (Fig. 3b). Notice that in these mutants the p98 signal is present, demonstrating that the binding of this protein is not dependent on C and D boxes. These results suggest that the two boxes are required for the binding of the p40 and p68 proteins and that this interaction is necessary to confer stability to the RNA molecule. Furthermore, both boxes should be intact for the binding of the two proteins.

FIG. 3.

Box C/D mutant analysis. (a) Time course of in vivo snoRNP complex assembly on U16 snoRNA and its mutant derivatives bC and bD. The sequences of the boxes C and D are reported in panel b together with the substituted nucleotides. 32P-labelled U16, bC, and bD RNAs were injected into oocytes and incubated for 10 min or for 2 h. The nuclei were loaded onto a native 4% polyacrylamide gel. The bands corresponding to complexes A and B are indicated. (b) Upper part, gel electrophoresis analysis of the proteins UV cross-linked in vivo to 32P-labelled U16, bC, and bD RNAs. Samples were analyzed on denaturing SDS–13% polyacrylamide gel. The 40- and 68-kDa proteins are indicated. Incubation times are noted below. The base substitutions inside the conserved boxes are shown in the schematic representation at the right. Lower part, 6% polyacrylamide–7 M urea gel of the RNA extracted at the corresponding time points. The input RNA (p) and trimmed form (m) are indicated.

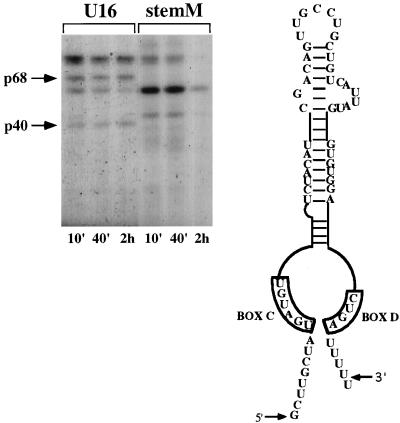

Figure 4 shows the pattern of UV cross-linked proteins on the stemM mutant, in which four base substitutions prevent the formation of the conserved 5′,3′-terminal stem. Despite its instability, this RNA survives for almost 40 min (data not shown), during which time it is possible to analyze the protein pattern. Again, neither the p40 nor the p68 protein is detected. These data indicate that, in addition to the conserved boxes, correct structure of the terminal stem is required for binding of the two C/D-specific proteins. The oocytes utilized in this experiment produce a very specific protein pattern by 10 min. Variability in the timing of protein binding was observed in all the experiments performed with different batches of oocytes. This difference is very likely due to the already reported and well-known variability of the oocyte system.

FIG. 4.

Gel electrophoresis analysis of the proteins UV cross-linked in vivo to 32P-labelled U16 and its mutant derivative stemM RNA. Samples were obtained and analyzed as shown in the previous figures. The base substitutions of the 5′,3′-terminal stem are shown in the schematic representation at the right.

Δ2 mutant RNA harbors a 28-nucleotide deletion of the apical stem-loop but has intact boxes C and D (see schematic representation in Fig. 5). In Fig. 5a, the band shift analysis shows that Δ2 RNA produces a different B-type complex (B′). In addition, its assembly is considerably delayed; at 8 h, almost 50% of the complexes are in the B′ form, while 80% of wild-type U16 snoRNA is in complex B (lane U16). RNA analysis (shown in the lower part of Fig. 5a) indicates that this mutant stably accumulates as the wild-type RNA. The pattern of UV cross-linked proteins, shown in Fig. 5b, reveals the presence of both p40 and p68 proteins, indicating that binding of the two proteins does not require the apical stem-loop structure. On the basis of this analysis, it is impossible to determine whether the faster migration of complex B′ is due to a different protein composition or to the different size and/or structure of the mutant RNA. Nevertheless, the different size of the RNA does not seem to affect the migration of complex A, which corresponds to that of the wild-type RNA. Additional mutations in the conserved central stem, previously reported to be important for U16 processing from the pre-mRNA (30), were also shown not to affect p40 and p68 binding (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Δ2 RNA mutant analysis. (a) Upper part, time course of in vivo snoRNP complex assembly on Δ2 RNA. The schematic representation at the right indicates the extension of the deletion. 32P-labelled Δ2 RNA was injected into oocytes, and incubation was allowed to proceed for the times indicated below. Lane U16, 32P-labelled U16 snoRNA was injected, and incubation was allowed to proceed for 8 h. The nuclei were loaded onto a native 4% polyacrylamide gel. The bands corresponding to complexes A, B′, and B are indicated. Lower part, 6% polyacrylamide–7 M urea gel of the RNA extracted at the corresponding time points. The 80-nucleotide-long injected Δ2 snoRNA precursor (p) and the 74-nucleotide-long mature (m) forms are indicated. (b) Gel electrophoresis analysis of the proteins UV cross-linked in vivo to 32P-labelled U16 and Δ2 RNAs after 8 h of incubation. Samples were obtained and analyzed as in the previous figures.

Fibrillarin association with U16 snoRNA.

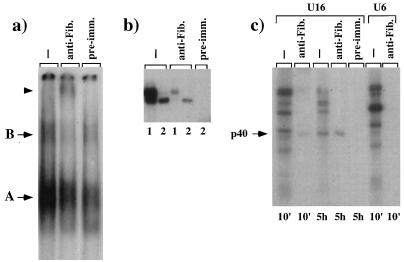

We previously showed that U16 snoRNA is associated in vivo in complexes containing fibrillarin (13), and so far its presence is considered diagnostic for the formation of box C/D snoRNPs (3, 8, 28, 39, 41). It was previously shown that fibrillarin association relies on the presence of box C, as in the case of U3 (3), or on the presence of both boxes, as demonstrated for U8 snoRNA (28). In order to determine the presence of fibrillarin in U16 snoRNP particles, we followed three different approaches. The first comprises a supershift assay of in vivo-assembled complexes with monoclonal antibodies against fibrillarin. Figure 6a shows that complex B is almost quantitatively supershifted when extracts from injected nuclei are incubated with antifibrillarin antibodies. The second approach used the immunoprecipitation of fibrillarin-containing complexes from microinjected nuclei followed by RNA analysis. Figure 6b shows that fibrillarin has already become associated with a small fraction of U16 by 10 min of incubation (compare lanes 1); at 2 h of incubation, RNA is almost quantitatively immunoprecipitated (compare lanes 2). Δ2 mutant RNA, which harbors the longest deletion we have analyzed (28 nucleotides), is also immunoprecipitated by antifibrillarin antibodies (data not shown), indicating that the U16 apical stem-loop is not necessary for fibrillarin association. The third approach was immunoprecipitation with antibodies against fibrillarin of UV cross-linked proteins. Figure 6c shows that antibodies already specifically recognize the p40 protein at 10 min (lane 10′) and more significantly at prolonged incubation times (lane 5h). As a control, none of the proteins bound to U6 snRNA was immunoprecipitated (lane U6 anti-Fib.). These data indicate that fibrillarin is intimately associated with U16 snoRNA.

FIG. 6.

Analysis of fibrillarin association. (a) Supershift analysis was performed with monoclonal antibodies against fibrillarin (lane anti-Fib.) or with preimmune immunoglobulin G (lane pre-imm.) on five nuclei injected with 32P-labelled U16 RNA and incubated for 2 h; in lane −, five control nuclei were loaded. Complexes A and B are indicated by arrows, and the supershifted complex is indicated by an arrowhead. (b) Nuclei were dissected from oocytes injected with 32P-labelled U16 RNA and incubated for 10 min (lanes 1) or 5 h (lanes 2). RNA was extracted from 20 control nuclei (lanes −) or from the pellets of 20 nuclei immunoprecipitated with antifibrillarin (lanes anti-Fib.) or preimmune (lane pre-imm.) serum. The samples were loaded on a 6% polyacrylamide–urea gel. (c) Oocytes were injected with U16 or U6 32P-labelled transcripts, and nuclei were manually dissected, UV irradiated, and, after RNase digestion, immunoprecipitated with antifibrillarin antibodies (lanes anti-Fib.) or preimmune serum (lanes pre-imm.). Lanes − show control UV cross-linking to U16 and to U6 RNAs. The products were run on an SDS–13% polyacrylamide gel. Incubation times are indicated below. The arrow indicates the p40 protein.

DISCUSSION

The identification of the numerous snoRNAs has indicated that the nucleolus, the site of ribosome assembly, may be by far the most complex of the known cellular RNA machines. All the different snoRNAs are associated with proteins forming specific complexes (snoRNPs), and so far very little is known about their identity and function. The discovery that most snoRNPs mediate posttranscriptional modifications of rRNA is quite recent. While it is believed that the role of the RNA component is to function as a guide in the selection of the specific residue to be modified, much less is known about the role played by the protein components. They can play a structural role or directly participate in the modifying and/or processing reactions as catalytic components. The only information available indicates that temperature-sensitive mutations of fibrillarin and Gar1 in yeast cause lower levels of methylation and pseudourydilation, respectively (5, 37). Nevertheless, the specific role of snoRNP protein components is not known.

In this study, we have analyzed the nuclear factors that associate in vivo with the X. laevis intron-encoded U16 snoRNA, which is a member of the box C/D snoRNA family (13). The results indicate that, after the injection, the RNA is rapidly assembled into a fast-migrating complex which is replaced in time by a slow-mobility complex. This particle represents the major species after 8 h and is the only one observed after overnight incubation. At short intervals, the pattern of UV cross-linked proteins is quite complex; however, it becomes much simpler after prolonged incubations when the stable, larger complex accumulates. At long incubation times, three major UV cross-linked proteins are detected, with apparent molecular masses of 40, 68, and 98 (a doublet) kDa. While the specificity of p98 is still difficult to assess, since proteins of this size are visualized with all the U16 mutants, the binding of the 40- and 68-kDa proteins was shown to be highly specific in a number of ways. The same two factors were revealed by in vivo UV cross-linking with other C/D box-containing snoRNAs, such as U18 and U3, while they were not visualized on the unrelated spliceosomal U6 snRNA. Specificity was also verified by competition experiments. C/D box-containing snoRNAs were able to compete out the binding of the two proteins from U16, while U6 snRNA could not.

Band shift and UV cross-linking analyses with several U16 mutants allowed us to identify the sequences required for p40 and p68 binding. Mutations in the boxes C and D and in the conserved 5′,3′-terminal stem were tested first. Since mutations in these regions are known to strongly affect the stability of the RNA, we analyzed the UV cross-linked proteins at very short incubation times, when the RNA had not yet been degraded and when both proteins were already present in the wild-type substrate. Under these conditions, neither the p40 nor the p68 protein could be detected. Since mutations in other parts of the U16 molecule did not affect binding, we could conclude that only the conserved boxes and terminal stem are necessary for p40 and p68 association.

Since fibrillarin is the only protein known to associate with the C/D class of snoRNAs, we sought to determine whether it is present in U16 complexes. Supershift analysis and immunoprecipitation experiments with antifibrillarin antibodies confirmed that fibrillarin is present in the U16 complex and demonstrated that it corresponds to the p40 protein. Interestingly, binding of fibrillarin and p68 was affected by the same mutations, suggesting that the two proteins cooperate for the binding to the conserved C/D box region. In conclusion, these two RNA-binding proteins appear to represent general factors associated with all box C/D snoRNAs. It is very likely that, similarly to the well-characterized snRNPs, other proteins, specific for single snoRNA species, associate with these common factors. If U16-specific factors exist, they have been underscored in our assay, since U16 snoRNPs constitute a small fraction of the overall population of box C/D snoRNPs. If specific factors have to be studied, large-scale fractionation of endogenous U16 snoRNP particles will be required.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Elsebet Lund and Michael Terns for kindly providing plasmids, Michèle Caizergues-Ferrer for fibrillarin antibodies, and Paola Pierandrei-Amaldi for the La antibodies. We also thank Jorg Hamm and Paola Fragapane for helpful discussion. We thank Massimo Arceci and Roberto Gargamelli for skillful technical help and Fabio Riccobono and M-medical for oligonucleotide facilities.

This work was partially supported by grants from 5% Biotecnologie of C.N.R. and by CEC contract no. CHRX-CT94-0677.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bachellerie J P, Michot B, Nicoloso M, Balakin A, Ni J, Fournier M J. Antisense snoRNAs: a family of nucleolar RNAs with long complementarities to rRNA. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:261–264. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89039-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balakin A G, Smith L, Fournier M J. The RNA world of the nucleolus: two major families of small RNAs defined by different box elements with related functions. Cell. 1996;86:823–834. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80156-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baserga S J, Yang X W, Steitz J A. An intact box C sequence in the U3 snRNA is required for binding of fibrillarin, the protein common to the major family of nucleolar snRNPs. EMBO J. 1991;10:2645–2651. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07807.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baserga S J, Gilmore-Hebert M, Yang X W. Distinct molecular signals for nuclear import of the nucleolar snRNA, U3. Genes Dev. 1992;6:1120–1130. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.6.1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bousquet-Antonelli C, Henry Y, Gélugne J P, Caizergues-Ferrer M, Kiss T. A small nucleolar RNP protein is required for pseudouridylation of eukaryotic ribosomal RNAs. EMBO J. 1997;16:4770–4776. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.15.4770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caffarelli E, Fragapane P, Gehring C, Bozzoni I. The accumulation of mature RNA for the Xenopus laevis ribosomal protein L1 is controlled at the level of splicing and turnover of the precursor RNA. EMBO J. 1987;6:3493–3498. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02674.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caffarelli E, Arese M, Santoro B, Fragapane P, Bozzoni I. In vitro study of processing of the intron-encoded U16 small nucleolar RNA in Xenopus laevis. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:2966–2974. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.5.2966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caffarelli E, Fatica A, Prislei S, De Gregorio E, Fragapane P, Bozzoni I. Processing of intron-encoded U16 and U18 snoRNAs: the conserved C and D boxes control both the processing reaction and the stability of the mature snoRNA. EMBO J. 1996;15:1121–1131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caffarelli E, Maggi L, Fatica A, Jiricnj J, Bozzoni I. A novel Mn++-dependent ribonuclease that functions in U16 snoRNA processing in X. laevis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;233:514–517. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cavaillé J, Nicoloso M, Bachellerie J P. Targeted ribose methylation of RNA in vivo directed by tailored antisense RNA guides. Nature. 1996;383:732–735. doi: 10.1038/383732a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fournier M J, Maxwell E S. The nucleolar snRNAs: catching up with the spliceosomal snRNAs. Trends Biochem Sci. 1993;18:131–135. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(93)90020-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fragapane P, Caffarelli E, Lener M, Prislei S, Santoro B, Bozzoni I. Identification of the sequences responsible for the splicing phenotype of the regulatory intron of the L1 ribosomal protein gene of Xenopus laevis. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:1117–1125. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.3.1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fragapane P, Prislei S, Michienzi A, Caffarelli E, Bozzoni I. A novel small nucleolar RNA (U16) is encoded inside a ribosomal protein intron and originates by processing of the pre-mRNA. EMBO J. 1993;12:2921–2928. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05954.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ganot P, Bortolin M-L, Kiss T. Site specific pseudouridine formation in preribosomal RNA is guided by small nucleolar RNAs. Cell. 1997;89:799–809. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80263-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ganot P, Caizergues-Ferrer M, Kiss T. The family of box ACA small nucleolar RNAs is defined by an evolutionarily conserved secondary structure and ubiquitous sequence elements essential for RNA accumulation. Genes Dev. 1997;11:941–956. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.7.941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang G M, Jarmolowski A, Struck J C R, Fournier M J. Accumulation of U14 small nuclear RNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae requires box C, box D, and a 5′,3′ terminal stem. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:4456–4463. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.10.4456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kiss-Laszlò Z, Henry Y, Bachellerie J P, Caizergues-Ferrer M, Kiss T. Site-specific ribose methylation of preribosomal RNA: a novel function for small nucleolar RNAs. Cell. 1996;85:1077–1088. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81308-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lapeyre B, Mariottini P, Mathieu C, Ferrer P, Amaldi F, Amalric F, Caizergues-Ferrer M. Molecular cloning of Xenopus fibrillarin, a conserved U3 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein recognized by antisera from humans with autoimmune disease. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:430–434. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.1.430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lubben B, Marshallsay C, Rottmann N, Luhrmann R. Isolation of U3 snoRNP from CHO cells: a novel 55 kDa protein binds to the central part of U3 snoRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:5377–5385. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.23.5377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lubben B, Fabrizio P, Kastner B, Luhrmann R. Isolation and characterization of the small nucleolar ribonucleoprotein particle snR30 from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:11549–11554. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.19.11549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maxwell E S, Fournier M J. The small nucleolar RNAs. Annu Rev Biochem. 1995;35:897–934. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.004341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Melton D A, Krieg P A, Rebagliati M R, Maniatis T, Zinn K, Green M R. Efficient in vitro synthesis of biologically active RNA and RNA hybridization probes from plasmids containing a bacteriophage SP6 promoter. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:7035–7056. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.18.7035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Milligan J F, Groebe D R, Witherell G W, Uhlembeck O C. Oligoribonucleotide synthesis using T7 RNA polymerase and synthetic DNA templates. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:8783–8798. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.21.8783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ni J, Tien A L, Fournier M J. Small nucleolar RNAs direct site-specific synthesis of pseudouridines in ribosomal RNA. Cell. 1997;89:565–573. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80238-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nicoloso M, Caizergues-Ferrer M, Michot B, Azum M C, Bachellerie J P. U20, a novel small nucleolar RNA, is encoded in an intron of the nucleolin gene in mammals. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:5766–5776. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.9.5766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nicoloso M, Qu L H, Michot B, Bachellerie J P. Intron-encoded, antisense small nucleolar RNAs: the characterization of nine novel species points to their direct role as guides for the 2′-O-ribose methylation of rRNAs. J Mol Biol. 1996;260:178–195. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peculis B A, Steiz J A. Disruption of U8 nucleolar snRNA inhibits 5.8S and 28S rRNA processing in the Xenopus oocyte. Cell. 1993;73:1233–1245. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90651-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peculis B A, Steiz J A. Sequence and structural elements critical for U8 snRNP function in Xenopus oocytes are evolutionarily conserved. Genes Dev. 1994;8:2241–2255. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.18.2241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peek R, Pruijn G J M, Van Venrooij W J. Interaction of the La (SS-B) autoantigen with small ribosomal subunits. Eur J Biochem. 1996;236:649–655. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0649d.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prislei S, Sperandio S, Fragapane P, Caffarelli E, Presutti C, Bozzoni I. The mechanisms controlling ribosomal protein L1 pre-mRNA splicing are maintained in evolution and rely on conserved intron sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:4473–4479. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.17.4473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prislei S, Michienzi A, Presutti C, Fragapane P, Bozzoni I. Two different snoRNAs are encoded in introns of amphibian and human L1 ribosomal protein genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:5824–5830. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.25.5824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reddy R, Busch H. Small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particles. In: Birnstiel M L, editor. Structure and function of major and minor small nuclear ribonucleotide particles. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 1988. pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith C M, Steitz J A. Sno storm in the nucleolus: new roles for myriad small RNPs. Cell. 1997;89:669–672. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80247-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Terns M P, Lund E, Dahlberg J E. 3′-end-dependent formation of U6 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particles in Xenopus laevis oocyte nuclei. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:3032–3040. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.7.3032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Terns M P, Dahlberg J E. Retention and 5′ cap trimethylation of U3 snRNA in the nucleus. Science. 1994;264:959–961. doi: 10.1126/science.8178154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Terns M P, Grimm C, Lund E, Dahlberg J E. A common maturation pathway for small nucleolar RNAs. EMBO J. 1995;14:4860–4871. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00167.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tollervey D, Lehtonen H, Jansen R, Kern H, Hurt E C. Temperature-sensitive mutations demonstrate roles for yeast fibrillarin in pre-rRNA processing, pre-rRNA methylation, and ribosome assembly. Cell. 1993;72:443–457. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90120-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tollervey D, Kiss T. Function and synthesis of small nucleolar RNAs. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:337–342. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tyc K, Steitz J A. U3, U8 and U13 comprise a new class of mammalian snRNPs localized in the cell nucleolus. EMBO J. 1989;8:3113–3119. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08463.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tycowski K T, Shu M D, Steitz J A. A small nucleolar RNA is processed from an intron of the human gene encoding ribosomal protein S3. Genes Dev. 1993;7:1176–1190. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.7a.1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Watkins N J, Leverette R D, Xia L, Andrews M T, Maxwell E S. Elements essential for processing intronic U14 snoRNA are located at the termini of the mature snoRNA sequence and include conserved nucleotide boxes C and D. RNA. 1996;2:118–133. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xia L, Watkins N J, Maxwell E S. Identification of specific nucleotide sequences and structural elements required for intronic U14 snoRNA processing. RNA. 1997;3:17–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]