Abstract

The yeast GCN5 gene encodes the catalytic subunit of a nuclear histone acetyltransferase and is part of a high-molecular-weight complex involved in transcriptional regulation. In this paper we show that full activation of the HO promoter in vivo requires the Gcn5 protein and that defects in this protein can be suppressed by deletion of the RPD3 gene, which encodes a histone deacetylase. These results suggest an interplay between acetylation and deacetylation of histones in the regulation of the HO gene. We also show that mutations in either the H4 or the H3 histone gene, as well as mutations in the SIN1 gene, which encodes an HMG1-like protein, strongly suppress the defects produced by the gcn5 mutant. These results suggest a hierarchy of action in the process of chromatin remodeling.

Nuclear processes, including transcription, require that enzymes gain access to the eukaryotic DNA template despite the fact that it is complexed with histone and nonhistone proteins to form chromatin. Genetic studies with Saccharomyces cerevisiae have identified two groups of genes that appear to link transcriptional regulation to chromatin structure (40). The first group encodes components of the SWI/SNF complex, which has been proposed to antagonize the repressive effects of chromatin on transcription (24). SWI/SNF genes were identified in genetic screens for mutants defective in the expression of various genes, including the HO and SUC2 genes (2, 18, 22, 32). The second group of genes includes various SPT and SIN genes, which were defined as suppressors of various types of transcriptional defects (40). The sin2-1 mutation was found to lie in the HHT1 gene, which encodes histone H3. Five additional different point mutations, two in histone H3 and three in histone H4, also displayed a Sin−/Spt− phenotype (12, 25). These mutations affect residues that are believed either to contact DNA or to be involved in histone-histone contacts within the histone octamer (39). The SIN1 gene was found to encode a protein with similarities to mammalian HMG1, a structural component of chromatin (11). Although the precise role of yeast SIN1 is not known, the similarity of sin1 and sin2-1 mutant phenotypes has led to the inference that these two genes have related physiological functions.

Recently, a group of genes involved in acetylation and deacetylation of histones has been recognized. Histone acetylation has long been correlated with the modulation of gene activity (37). Acetylation of lysines in histone amino-terminal tail domains reduces the positive charge, thereby weakening histone-DNA interactions, destabilizing higher-order structure, and rendering nucleosomal DNA more accessible to transcriptional factors (4, 14). Yeast Gcn5 was originally identified as a regulatory factor required for function of the yeast activator Gcn4 (5), and recently it has been shown that Gcn5 is a histone acetyltransferase (3, 13, 28) that is part of at least two high-molecular-weight complexes called ADA (8) and SAGA (7). The recruitment of these complexes to DNA is thought to direct the local destabilization of nucleosomes, producing more efficient transcriptional activation on a promoter. Aside from transcriptional regulators that function as histone acetyltransferases, there are also regulators that deacetylate the histones (29, 36). These deacetylases comprise part of a transcriptional repression pathway conserved from yeast to vertebrates and provide a molecular mechanism whereby transcription can be continually controlled (19, 38).

In this paper we show that the expression of the HO gene is affected by defects in histone acetylation and deacetylation. Previous work has shown that the SWI/SNF complex and structural components of chromatin also affect HO expression (11, 12, 16, 22). We present an analysis of single and double mutations in the genes encoding several of these components, and the results suggest a hierarchy in the chromatin remodeling process.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and media.

All strains of S. cerevisiae used in this study are described in Table 1. Complete medium (yeast extract-peptone-dextrose [YEPD]) and minimal medium supplemented with the required amino acids were used for yeast growth and transformations (26). Histidine limitation was accomplished by supplementing minimal media with 10 mM 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole (3-AT) (5).

TABLE 1.

Yeast strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype |

|---|---|

| FY120 | MATa ura3-52 leu2Δ1 his4-912δ Lys2-128δ |

| RT238 | MATα ura3-52 leu2Δ1 his3 trp1 HO-lacZ |

| JJY12 | MATα ura3-52 leu2 Δ1 trp1 lys2-128δ HO-lacZ |

| JJY13 | Same as JJY12, plus swi5::hisG |

| JJY28 | Same as JJY12, plus gcn5::hisG |

| JJY36 | Same as JJY12, plus sin1Δ::TRP1 |

| JJY42 | Same as JJY28, plus hhf2-8 |

| JJY43 | Same as JJY28, plus hhf2-13 |

| JJY44 | Same as JJY28, plus sin2-1 |

| JJY45 | Same as JJY28, plus sin1Δ::TRP1 |

| JJY54 | Same as FY120, plus gcn5::hisG |

| JJY60 | Same as JJY28, plus swi5::hisG |

| JJY64 | Same as JJY12, plus rpd3Δ::LEU2 |

| JJY65 | Same as JJY28, plus rpd3Δ::LEU2 |

| JJY72 | Same as JJY41, plus rpd3Δ::LEU2 |

| JJY73 | Same as JJY42, plus rpd3Δ::LEU2 |

| JJY74 | Same as JJY43, plus rpd3Δ::LEU2 |

| JJY75 | Same as JJY44, plus rpd3Δ::LEU2 |

Strain constructions.

Single mutants were obtained either by gene disruptions performed by using the one-step replacement method (27) or by gene conversions carried out by a two-step gene replacement procedure (31). Double and triple mutants were obtained by crossing single mutants of opposite mating types and selecting segregants carrying the desired mutations.

A strain carrying a swi5::LEU2 null allele was generated as described in reference 34. The gcn5::hisG strain was generated as described in reference 15. The HO-lacZ fusion allele is described in reference 30. The histone mutations were introduced in the chromosome by a two-step replacement procedure (31) using integrating plasmids marked with the URA3 gene (obtained from R. K. Tabtiang and I. Herskowitz); as these mutations are partially dominant, it is possible to observe their effects, even in the presence of another histone gene copy (12). The rpd3Δ::LEU2 strain was generated by transforming yeast with pDM176 digested with BamHI. This plasmid carries the RPD3 locus with a replacement of the entire RPD3 open reading frame (ORF) with the LEU2 gene (15a). Correct integration was tested by PCR analysis using oligonucleotides flanking the RPD3 locus. The sin1Δ::TRP1 deletion strains were generated by transforming yeast with pUC-SIN1::TRP linearized with EcoRI-SphI. This plasmid carries a replacement of the SIN1 ORF with the TRP1 gene (11). Correct integration was tested by PCR analysis using oligonucleotides flanking the SIN1 locus.

RNA analysis.

Strains were grown to mid-log phase in YEPD medium. Total-yeast RNA was isolated and fractionated on formaldehyde gels, transferred to nylon membranes (Genescreen; DuPont), and hybridized with random-primed 32P-labeled fragments. The DNA probes used were obtained as PCR fragments by amplification of the desired ORF with specific primers (MapPairs; Research Genetics Inc.), with the exception of the HO probe, which was obtained as a 2.6-kb HindIII fragment from the plasmid pGAL-HO (9).

Other methods.

Yeast cells were transformed by the LiOAc method (6). β-Galactosidase assays were performed as described elsewhere (26).

RESULTS

The Gcn5 protein is required for HO expression.

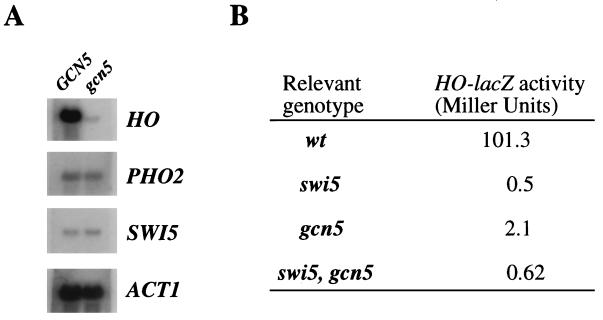

HO gene expression is dependent on SWI5. This gene encodes a zinc finger DNA-binding protein which binds specifically, along with the PHO2 protein, to the upstream region of the HO promoter (1, 34). Genetic studies have described a series of extragenic suppressor mutations that permit expression of HO in the absence of the SWI5 gene product (17, 33). Two of the genes identified in this screen, RPD3 and SIN3, encode, respectively, a histone deacetylase and a protein tightly associated with it (10, 29, 35). The fact that mutations in the gene pair SIN3/RPD3 are able to suppress the absence of the Swi5 protein suggests that one of the roles of the Swi5-Pho2 heterodimer is the recruitment, either directly or indirectly, of a histone acetyltransferase activity. A likely candidate is the GCN5 gene, which encodes a protein with histone acetyltransferase activity (13). To test this idea, we examined the levels of HO mRNA produced in wild-type and isogenic gcn5 mutant strains (obtained by disruption of the GCN5 gene; see Materials and Methods). We found that a gcn5 mutant strain produced significantly less HO mRNA (Fig. 1A). By contrast, the absence of the Gcn5 protein did not impair the normal levels of PHO2 and SWI5 mRNA.

FIG. 1.

Gcn5 is required for HO expression. (A) Effects of gcn5 disruption on the mRNA levels of the HO, PHO2, and SWI5 genes. Total RNA was extracted from FY120 (GCN5) and JJY54 (gcn5::hisG) grown in YEPD medium to mid-log phase. ACT1 mRNA was used as a control. (B) Genetic relationships between SWI5 and GCN5. β-Galactosidase activity was measured in strains carrying an HO-lacZ reporter gene integrated in the chromosome at the HO locus. The strains used were JJY12 (wild type [wt]), JJY28 (gcn5::hisG), JJY13 (swi5::hisG), and JJY60 (gcn5::hisG swi5::hisG). Values are averages of three independent measurements with less than 10% deviation.

In principle, SWI5 and GCN5 gene products could act in the same pathway or through different pathways to activate HO expression. If two genes act in the same pathway, then the phenotype of the double mutant should be the same as that of one of the single mutants. On the other hand, if two genes act through different pathways, then the phenotype of the double mutant should be more severe than that of either single mutant. To distinguish between these two possibilities, we measured the β-galactosidase activity produced by a chromosomal HO-lacZ gene fusion in a swi5 gcn5 double mutant and compared it to those in the single mutants (Fig. 1B). HO-lacZ expression in the gcn5 and swi5 mutants was reduced 50- and 200-fold, respectively. In the double mutant, HO-lacZ expression was reduced 200-fold. The β-galactosidase values of the swi5 mutant are so low (0.5 Miller units) that we cannot make a conclusive argument about the relationship of SWI5 and GCN5. However, since both defects are suppressed by the same mutations (i.e., by rpd3, sin1, and sin2 mutations; see below) and since the levels of mRNA for SWI5 and PHO2 genes are not affected by gcn5 mutations (Fig. 1A), these facts support the idea that SWI5 and GCN5 act in the same pathway to stimulate HO expression.

Deletion of the RPD3 gene suppresses the gcn5 mutation.

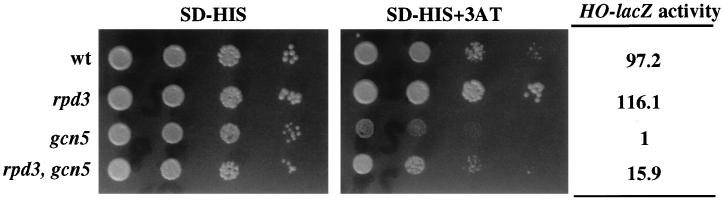

The results described above are compatible with the idea that histone acetylation is required for maximal HO transcriptional activation. According to this hypothesis, a mutation in a gene encoding a deacetylase should be able to suppress a gcn5 mutation. A likely candidate is the RPD3 gene, since mutations in this gene suppress the Swi5 requirement in the HO gene (35). We therefore measured HO-lacZ activity in single and double mutants carrying null alleles of the GCN5 and RPD3 genes. The results (Fig. 2) show that a deletion of the deacetylase gene RPD3 alleviates the requirement for the histone acetyltransferase gene GCN5 in HO gene expression. The level of suppression of a gcn5 mutation by the deletion of RPD3 is similar to that observed in the case of swi5 mutations (35) and is also similar to the suppression observed in a triple swi5 gcn5 rpd3 mutant, again supporting the view that SWI5 and GCN5 function in the same pathway.

FIG. 2.

A deletion of the RPD3 gene partially suppresses the defects caused by a disruption of the GCN5 gene. Cultures of JJY1 (wild type [wt]), JJY64 (rpd3Δ::LEU2), JJY28 (gcn5::hisG), and JJY65 (rpd3Δ::LEU2 gcn5::hisG) cells (approximately 5 × 106/ml) were spotted in 10-fold serial dilutions on medium lacking histidine (SD-HIS) and on medium lacking histidine and containing 10 mM 3-AT. Plates were incubated at 30°C for 3 days. The same cultures were used to measure β-galactosidase activity (in Miller units). Values are averages of three independent measurements with less than 10% deviation.

One of the defects originally observed in gcn5 mutant strains was their inability to grow in media imposing amino acid limitation (20). Thus, a strain carrying a deletion of the GCN5 gene is defective in growth in media containing 3-AT, a condition that mimics histidine starvation (5). To address whether a deletion in the RPD3 gene suppresses other defects in gcn5 strains, we also tested the ability of the RPD3 deletion to allow growth of a gcn5 strain in the presence of 3-AT. As shown in Fig. 2, the gcn5 strain exhibited a growth defect under such conditions compared with an isogenic wild-type strain. Deletion of the RPD3 gene indeed alleviates this defect, allowing growth of the gcn5 strain under these conditions.

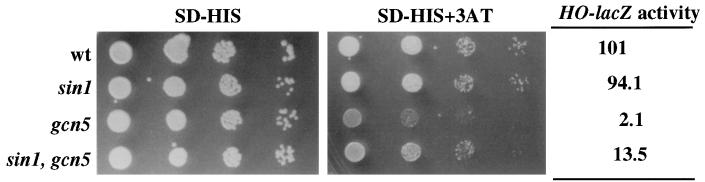

Disruption of SIN1, a gene encoding an HMG1-like protein, also suppresses gcn5 defects.

In addition to sin3 and rpd3 mutations, defects in other genes are well-known suppressors of transcriptional deficiencies in HO. One of these genes is SIN1. This gene encodes a protein with similarities to the mammalian HMG1 protein, and it is believed to be a component of chromatin (11). We have monitored both HO-lacZ expression and the ability to grow in the presence of 3-AT of a double mutant defective in both GCN5 and SIN1. The results shown in Fig. 3 indicate that the absence of Sin1 protein relieves the requirement of Gcn5 both for HO expression and for growth on 3-AT.

FIG. 3.

Deletion of the SIN1 gene alleviates the defects associated with disruption of the GCN5 gene. Cultures of JJY12 (wild type [wt]), JJY36 (sin1Δ::TRP1), JJY28 (gcn5::hisG), and JJY45 (sin1Δ::TRP1 gcn5::hisG) cells (approximately 5 × 106/ml) were spotted in 10-fold serial dilutions on medium lacking histidine (SD-HIS) and on medium lacking histidine and containing 10 mM 3-AT. Plates were incubated at 30°C for 3 days. The same cultures were used to measure β-galactosidase activity (in Miller units). Values are averages of three independent measurements with less than 10% deviation.

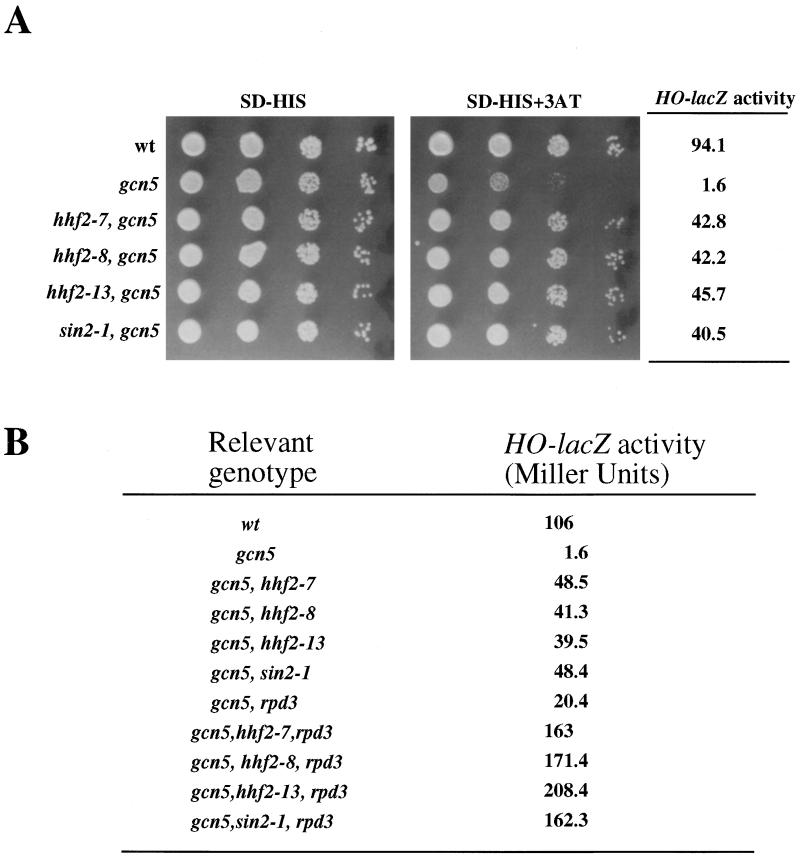

Histone mutations also suppress gcn5 defects.

An explanation for the results obtained with the sin1 mutant is that the suppression we observed is caused by a defect in chromatin structure, such that this defective chromatin bypasses the requirement for histone acetylation. If this is the case, then other mutations which produce defective chromatin might also be expected to suppress the gcn5 defects. Certain amino acid changes (sin mutations) in either histone H3 or histone H4 alleviate the same set of transcriptional defects as does the sin1 mutation (12, 23). These sin mutations lie in the histone fold domain of histones H3 and H4, and they are in close proximity to one another on the surface of the histone octamer. It has been proposed that residues altered by these mutations may define a functional domain (the SIN domain) that behaves formally as a negative regulator of transcription (12).

To address if defective histones also suppress gcn5 mutations, the following histone mutant alleles were tested for their ability to suppress a deletion of the GCN5 gene: sin2-1 (R116H in HHT1), hhf2-7 (R45C in HHF4), hhf2-8 (V43I in HHF4), and hhf2-13 (R45H in HHF4). In spite of the fact that the targets for GCN5 protein are the histone tails, mutations in the histone fold are able to efficiently suppress the defects caused by the absence of the GCN5 gene product (Fig. 4A).

FIG. 4.

Histone sin mutations suppress gcn5 defects. (A) Cultures of JJY12 (wild type [wt]), JJY28 (gcn5::hisG), JJY41 (hhf2-7 gcn5::hisG), JJY42 (hhf2-8 gcn5::hisG), JJY43 (hhf2-13 gcn5::hisG), and JJY44 (sin2-1 gcn5::hisG) cells (approximately 5 × 106/ml) were spotted in 10-fold serial dilutions on medium lacking histidine (SD-HIS) and on medium lacking histidine and containing 10 mM 3-AT. Plates were incubated at 30°C for 3 days. The same cultures were used to measure β-galactosidase activity (in Miller units). Values are averages of three independent measurements with less than 10% deviation. (B) Effects of rpd3 deletion on the suppression of gcn5 defects by histone sin mutations and sin1 mutations. The strains used were JJY12, JJY28, and JJY41 through JJY44 (all as described for panel A), as well as JJY65 (rpd3Δ::LEU2 gcn5::hisG), JJY72 (hhf2-7 rpd3Δ::LEU2 gcn5::hisG), JJY73 (hhf2-8 rpd3Δ::LEU2 gcn5::hisG), JJY74 (hhf2-13 rpd3Δ::LEU2 gcn5::hisG), and JJY75 (sin2-1 rpd3Δ::LEU2 gcn5::hisG). Values are averages of three independent measurements with less than 10% deviation.

We also determined the effects of combining a deletion of the RPD3 gene with the histone sin mutations. Levels of HO-lacZ activity were determined in single and double mutants, and we found in the double mutants a strong synergistic effect; that is, the activity displayed by the double mutant is higher than the sum of the activities displayed by the single mutants (Fig. 4B). The same synergistic effect is also seen in combinations of rpd3 and sin1 mutations (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Regulation of the yeast HO gene is complex, and many genes that regulate HO have been identified (16). These include genes encoding the SWI/SNF complex (22, 32); SIN1, which encodes an HMG1-like protein (11); SIN2, which encodes histone H3; HHF4, which encodes histone H4 (12); and SIN3, which, along with RPD3, is involved in the deacetylation of histones (35). In this paper, we show a requirement for the GCN5 gene, which encodes a histone acetyltransferase (3), for optimal transcription of the HO gene.

The identification of histone acetyltransferases and histone deacetylases as transcriptional regulators provides molecular mechanisms whereby transcription might be turned up or down (38), but so far no such interplay between acetylase and deacetylase activities at a single gene has been reported. The suppression of the gcn5 defects by deletion of one of the genes encoding a deacetylase activity provides clear support for such interplay at the HO promoter. The suppression we observed is only partial, suggesting a functional redundancy in the deacetylase activity. Another protein with deacetylase activity is encoded by the gene HDA1, and three additional ORFs with high levels of homology with RPD3 and HDA1 have also been described (29). However, we observed that deletion of HDA1 or of one of these additional ORFs (HOS1) does not suppress the GCN5 requirement in HO expression (data not shown). Another explanation for the fact that suppression is only partial is that the rpd3 deletion may destabilize additional proteins with which it is complexed (7), and these additional proteins may contribute to the activation of HO.

The pattern of genetic interactions described in this work suggests a hierarchy of gene function that pertains to chromatin components, histone acetylation, and the SWI/SNF complex. Loss of Swi5 (the major activator protein for the HO gene [16]) can be partially suppressed by sin1, sin2 (histone H3), sin3, and rpd3 mutations (33, 35). Loss of GCN5 (a histone acetyltransferase, also required for HO transcription) can be suppressed by these same mutations (Fig. 2, 3, and 4A). However, while defects in the SWI/SNF complex can be suppressed by sin1 (which is thought to be a target of the SWI/SNF complex [21] and sin2 mutations (11, 12), they cannot be suppressed efficiently by sin3 or rpd3 mutations (33, 35). These results indicate that histone acetylation at the HO promoter functions upstream of the SWI/SNF complex. Consistent with this view is the strong synergy seen between rpd3 mutations (which affect the acetylation of histone tails) and sin1 and sin2 mutations (which circumvent the need for the SWI/SNF complex) (Fig. 4B). One hypothesis consistent with this genetic hierarchy is that, at the HO promoter, histone acetylation precedes and enables the action of the SWI/SNF complex. A similar view has recently been developed independently by Pollard and Peterson (24a).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank D. Moazed, R. K. Tabtiang, and R. Candau for providing indispensable strains and plasmids throughout the course of this work. D. Moazed is also acknowledged for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by an NIH grant to A.D.J. and by an EMBO long-term postdoctoral fellowship to J.P.-M.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brazas R M, Stillman D J. Identification and purification of a protein that binds cooperatively with the yeast SWI5 protein. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:5524–5537. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.9.5524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Breeden L, Nasmyth K. Cell cycle control of the HO gene: cis- and trans-acting regulators. Cell. 1987;48:389–397. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90190-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brownell J E, Zhou J, Ranalli T, Kobayashi R, Edmondson D G, Roth S Y, Allis C D. Tetrahymena histone acetyltransferase A: a homolog to yeast Gcn5p linking histone acetylation to gene activation. Cell. 1996;84:843–851. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81063-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garcia-Ramirez M, Rocchini M, Ausio J. Modulation of chromatin folding by histone acetylation. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:17923–17928. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.30.17923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Georgakopoulos T, Thireos G. Two distinct yeast transcriptional activators require the function of the GCN5 protein to promote normal levels of transcription. EMBO J. 1992;11:4145–4152. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05507.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gietz D, St. Jean A, Woods R A, Schiestl R H. Improved method for high efficiency transformation of intact yeast cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:1425. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.6.1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grant P A, Duggan L, Cote J, Roberts S M, Brownell J E, Candau R, Ohba R, Owen-Hughes T, Allis C D, Winston F, Berger S L, Workman J L. Yeast Gcn5 functions in two multisubunit complexes to acetylate nucleosomal histones: characterization of an Ada complex and the SAGA (Spt/Ada) complex. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1640–1650. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.13.1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guarente L. Transcriptional coactivators in yeast and beyond. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:517–521. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89120-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herskowitz I, Jensen R E. Putting the HO gene to work: practical uses for mating-type switching. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:132–146. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94011-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kasten M M, Dorland S, Stillman D J. A large complex containing the yeast Sin3p and Rdp3p transcriptional regulators. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:4852–4858. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.8.4852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kruger W, Herskowitz I. A negative regulator of HO transcription, SIN1 (SPT2), is a nonspecific DNA binding protein related to HMG1. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:4135–4146. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.8.4135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kruger W, Peterson C L, Sil A, Coburn C, Arents G, Moudrianakis E N, Herskowitz I. Amino acid substitutions in the structured domains of histones H3 and H4 partially relieve the requirement of the yeast SWI/SNF complex for transcription. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2770–2779. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.22.2770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuo M H, Brownell J E, Sobel R E, Ranalli T A, Cook R G, Edmondson D G, Roth S Y, Allis C D. Transcription-linked acetylation by Gcn5p of histones H3 and H4 at specific lysines. Nature. 1996;383:269–272. doi: 10.1038/383269a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee D Y, Hayes J J, Pruss D, Wolffe A P. A positive role for histone acetylation in transcription factor access to nucleosome DNA. Cell. 1993;72:73–84. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90051-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marcus G A, Silverman N, Berger S L, Horiuchi N, Guarante L. Functional similarity and physical association between GCN5 and ADA2: putative transcriptional adaptors. EMBO J. 1994;13:4807–4815. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06806.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15a.Moazed, D. Unpublished data.

- 16.Nasmyth K. Regulating the HO endonuclease in yeast. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1993;3:286–294. doi: 10.1016/0959-437x(93)90036-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nasmyth K, Stillman D J, Kipling D. Both positive and negative regulators of HO transcription are required for mother-cell-specific mating-type switching in yeast. Cell. 1987;48:579–587. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90236-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neigeborn L, Carlson M. Genes affecting the regulation of SUC2 gene expression by glucose repression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1984;108:845–858. doi: 10.1093/genetics/108.4.845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pazin M J, Kadonaga J T. What’s up and down with histone deacetylation and transcription? Cell. 1997;89:325–328. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80211-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Penn M D, Galgoci B, Greer H. Identification of AAS genes and their regulatory role in general control of amino acid biosynthesis in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:2704–2708. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.9.2704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pérez-Martín, J., and A. D. Johnson. Submitted for publication.

- 22.Peterson C L, Herskowitz I. Characterization of the yeast SWI1, SWI2, and SWI3 genes, which encode a global activator of transcription. Cell. 1992;68:573–583. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90192-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peterson C L, Kruger W, Herskowitz I. A functional interaction between the C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II and the negative regulator SIN1. Cell. 1991;64:1135–1143. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90268-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peterson C L, Tamkun J W. The SWI-SNF complex: a chromatin remodeling machine? Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:143–146. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)88990-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24a.Pollard K J, Peterson C L. Role for ADA/GCN5 products in antagonizing chromatin-mediated transcriptional repression. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:6212–6222. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.11.6212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prelich G, Winston F. Mutations that suppress the deletion of an upstream activating sequence in yeast: involvement of a protein kinase and histone H3 in repressing transcription in vivo. Genetics. 1993;135:665–676. doi: 10.1093/genetics/135.3.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rose M D, Winston F, Hieter P. Methods in yeast genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rothstein R. Targeting, disruption, replacement and allele rescue: integrative DNA transformation in yeast. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:281–301. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94022-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruiz-Garcia A B, Sendra R, Pamblanco M, Tordera V. Gcn5p is involved in the acetylation of histone H3 in nucleosomes. FEBS Lett. 1997;403:186–190. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00049-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rundlett S E, Carmen A A, Kobayashi R, Bavykin S, Turner B M, Grunstein M. HDA1 and RPD3 are members of distinct yeast histone deacetylase complexes that regulate silencing and transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14503–14508. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Russell D W, Jensen R, Zoller M J, Burke J, Errede B, Smith M, Herskowitz I. Structure of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae HO gene and analysis of its upstream regulatory region. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:4281–4294. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.12.4281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scherer S, Davis R W. Replacement of chromosome segments with altered DNA sequences constructed in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:4951–4955. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.10.4951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stern M, Jensen R, Herskowitz I. Five SWI genes are required for expression of the HO gene in yeast. J Mol Biol. 1984;178:853–868. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(84)90315-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sternberg P W, Stern J M, Clark I, Herskowitz I. Activation of the yeast HO gene by release from multiple negative controls. Cell. 1987;48:567–577. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90235-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stillman D J, Bankier A T, Seddon A, Groenhout E G, Nasmyth K. Characterization of a transcription factor involved in mother cell specific transcription of the yeast HO gene. EMBO J. 1988;7:485–494. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb02836.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stillman D J, Dorland S, Yu Y. Epistasis analysis of suppressor mutations that allow HO expression in the absence of the yeast SWI5 transcriptional activator. Genetics. 1994;136:781–788. doi: 10.1093/genetics/136.3.781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tauton J, Hassig C A, Schreiber S L. A mammalian histone deacetylase related to the transcriptional regulator Rpd3p. Science. 1996;272:408–411. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5260.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Turner B M, O’Neil L P. Histone acetylation in chromatin and chromosomes. Semin Cell Biol. 1995;6:229–236. doi: 10.1006/scel.1995.0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wade P A, Pruss D, Wolffe A P. Histone acetylation: chromatin in action. Trends Biochem Sci. 1997;22:128–132. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01016-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wechser M A, Kladde M P, Alfieri J A, Peterson C L. Effects of Sin− versions of histone H4 on yeast chromatin structure and function. EMBO J. 1997;16:2086–2095. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.8.2086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Winston F, Carlson M. Yeast SNF/SWI transcriptional activators and the SPT/SIN connection. Trends Genet. 1992;8:387–391. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(92)90300-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]