Highlights

-

•

Fatigue analysis of stents was conducted through cyclic loading.

-

•

Structural stability and fatigue life of stents can be compared using FEM.

-

•

D7 exhibited the greatest stability and structural rigidity under cyclic load.

Keywords: Computer simulation, Dog, Fatigue, Stents, Tracheal collapse

Abstract

This study aimed to evaluate fatigue of three stent designs when various forces are applied and perform a comparative analyses. A computer simulation using the finite element method was performed. In particular, we constructed a three-dimensional finite element model of nitinol stents with three designs (S6: single-woven wire, wire diameter: 0.006 inch; D6: double-woven wire, wire diameter: 0.006 inch, and D7: double-woven wire, wire diameter: 0.007 inch) that are used to treat canine tracheal collapse (TC). The stents were subjected to a 200 mmHg compression force, a pure torsion force in a perpendicular direction, and a bending-torsion force combining perpendicular and axial forces. The von Mises stress was calculated to evaluate the extent of stent displacement, and Goodman diagrams were plotted to compare fatigue life cycles. D7 exhibited a longer fatigue life compared to S6 and D6. Under compression, pure torsion, and bending-torsion forces, displacement was the smallest for D7, followed by D6 and S6. Similarly, the fatigue life was the longest for D7, followed by D6 and S6. S6 showed the greatest displacement when subjected to external forces; among stents designed using the same wire, D6 displayed less displacement than S6, and D7 exhibited superior fatigue life when subjected to varying degrees of force. This study showed that the structural stability and fatigue life of stents could be effectively compared using finite element method D7 has the greatest stability and structural rigidity under cyclic load.

1. Introduction

Canine tracheal stents are medical devices that can restore airway patency and immediately ameliorate respiratory failure in canines with end-stage tracheal stenosis. Tracheal stent placement is a minimally invasive procedure that is performed under general anesthesia and is usually followed by rapid recovery from anesthesia and symptom improvement, thereby allowing patients to be discharged on the same day (Weisse, Berent, Violette, McDougall & Lamb, 2019). By immediately alleviating the symptoms of patients who experienced chronic coughing and respiratory failure owing to tracheal collapse (TC), tracheal stent placement is effective in rapidly improving the quality of life of patients.

However, despite the effective clinical application of tracheal stents, stent failure is still a challenge (Weisse et al., 2019). The occurrence rate of complications due to stent fracture is approximately 19–50 % (Durant, Sura, Rohrbach & Bohling, 2012; Sura & Krahwinkel, 2008; Violette, Weisse, Berent & Lamb, 2019; Weisse et al., 2019). Symptoms resulting from stent fractures vary widely, ranging from asymptomatic to persistent and severe coughing, lung collapse, and airway perforation leading to mortality (Durant et al., 2012; Johnston & Tobias, 2017; Moritz, Schneider & Bauer, 2004; Sura & Krahwinkel, 2008). In the event of stent fracture, respiratory symptoms recur as the tracheal lumen narrows, and wire fragments from the stent can injure the tracheal wall, resulting in perforations. Resection and anastomosis of the affected stent and trachea are required to treat these complications, but euthanasia must also be considered (Mittleman, Weisse, Mehler & Lee, 2004).

There are various factors that can cause stent fracture. Contraction and relaxation of the respiratory muscles around the trachea, chronic respiratory disease, and coughing can increase cyclic loading on the weakened trachea and stent. Compression, bending, and torsion forces on the stent increase material fatigue, ultimately leading to stent failure (Petrini et al., 2012). In addition to the continual mechanical forces on the stent, the stent's material properties, design, size, placement process, extent of disease progression, and patient's anatomical features also contribute to stent failure (Auricchio, Constantinescu, Conti & Scalet, 2016; Yoon, Choi, Kim & Kim, 2017).

As stents are medical devices inserted directly into the body of patients, the assessment of their safety is crucial. Stent performance can be evaluated using a fatigue test, in which local compressive, radial, and shear forces are applied to the stent to assess its durability. We previously assessed the mechanical properties of stents with various designs using in vitro mechanical tests, and identified suitable stents for canine subjects with TC (Kim, Choi & Yoon, 2022). Nevertheless, further fatigue tests are required to evaluate fatigue of the stent material when subjected to cyclic loading.

This study aimed to analyze fatigue in three types of stents used in the treatment of canine TC, using the finite element method (FEM) for analysis. We hypothesized that the double-woven wire (diameter = 0.007 inches) will show the longest fatigue life when various cyclic loads are applied to the stent. By comparing the timing of fracture when each stent is subjected to repeated long-term stress, we investigated the long-term stability. By using finite element analysis to test fatigue, we anticipated that the optimization process for stent design and clinical procedures can be made simpler and less expensive.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Clinical evidence

Tracheas that are fitted with a stent are impacted by the complex physiological environment of the chest. The lumen diameter of the canine trachea changes during breathing. During repeated inspiration and expiration, the trachea contracts and relaxes, resulting in changes in the tracheal diameter of up to 24 % (Leonard, Johnson, Bonadio & Pollard, 2009). Coughing involves contraction of the muscles in the diaphragm and the chest and abdominal walls with the pharynx closed, increasing thoracic pressure. As the epiglottis opens, a strong exhalation and coughing sound are emitted, accompanied by strong airway compression (Polverino et al., 2012).

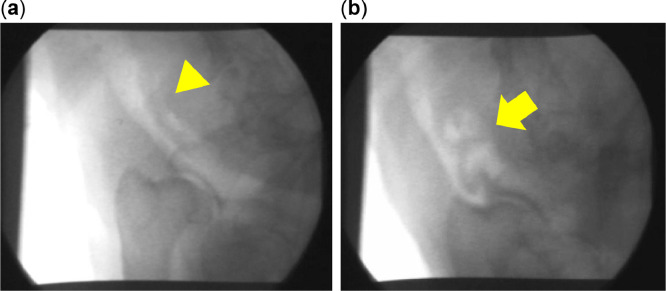

The mean cough pressure in canines is 200 mmHg (Niemann, Rosborough, Niskanen, Alferness & Criley, 1985). In individuals with weakened tracheal cartilage owing to TC, chronic cough can lead to tracheal kinking (Lee, Yun, Lee, Choi & Yoon, 2017). The bending and folding of the trachea in canines during coughing can be observed using fluoroscopic imaging (Fig. 1). In patients with severe TC fitted with a tracheal stent, coughing exerts complex torsion and bending forces on the stent, which, with repetition, could lead to deformation. The mean lifespan of canines is 11 years (Teng, Brodbelt, Pegram, Church & O'Neill, 2022), and given that refractory TC typically occurs in middle age or later, the stents should be guaranteed to last at least 5 years. Assuming one cough per minute, in which the intrathoracic pressure acts on the trachea, a given individual can be expected to cough 262,800 times in 5 years (60 times/h * 24 h/day * 365 days/year * 5 years); hence, we set a target lifespan of 300,000 cycles. In the loading condition, stents were subjected to 300,000 cycles of three types of force: a bending-torsion force (90° bending/90° torsion), a pure torsion force (90°), and a compression force (200 mmHg).

Fig. 1.

Fluoroscopic findings in the cervical trachea of a dog with end-stage tracheal collapse, under normal conditions (A) and during coughing (B). Cervical trachea shows a tracheoesophageal strip when not coughing (yellow arrow head). The trachea shows bent, flexed, and folded tracheal kinking (yellow arrow).

2.2. Stent types

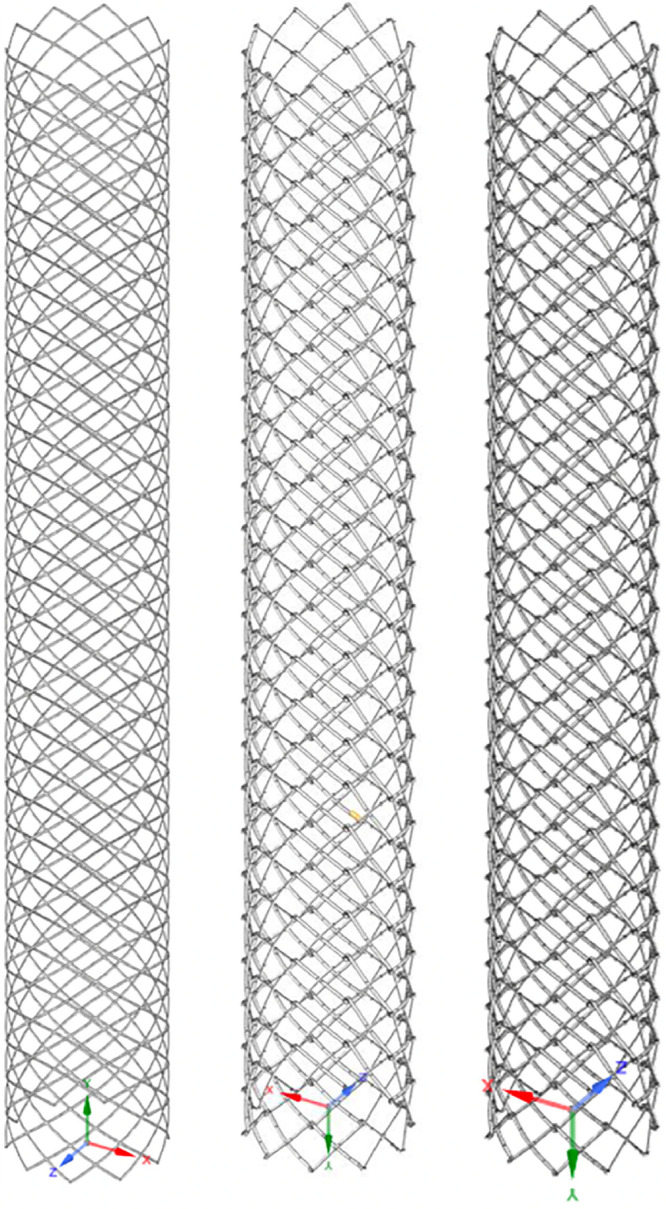

We selected three types of stents (S6, D6, D7) made of the same nickel-titanium alloy, but with different designs. These were all uncovered self-expanding metal stents (Niti-S biliary uncovered metallic stent; Taewoong Medical, Gimpo City, Korea; Fig. 2). S6 was a single-wire self-expanding metal stent with a wire diameter of 0.006 inches. D6 and D7 were double-wire braided stents with wire diameters of 0.006 and 0.007 inches, respectively. These three stents—S6, D6, and D7—were selected for this study so as to test the fatigue of the three most commonly used stents for treating canine TC, based on previous research. These three stents were chosen to conduct fatigue analysis, in conjunction with their previously studied mechanical properties, aiming to comprehensively evaluate the strength of the stents (Kim et al., 2022).

Fig. 2.

Three different types of 3D stent models used for fatigue analysis. S6, D6, and D7 are shown in order from left to right

3D, three-dimensional.

2.3. Fatigue analysis conditions

We used a computer-aided design software (ANSYS SpaceClaim Design Modeler 2022, Canonsberg, PA, USA) and convolutional autoencoder (ANSYS WORKBENCH 2022) for the three-dimensional (3D) modeling and fatigue test using the FEM (Supplementary Figure S1).

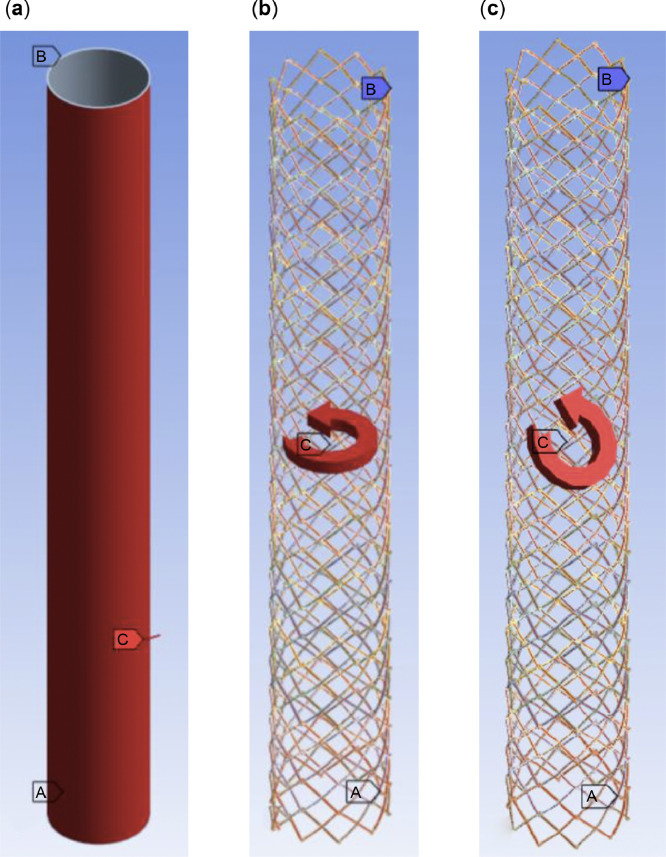

The stents were analyzed under the following conditions: two reference points (A and B) were created as constraint conditions as shown in Fig. 3; 200 mmHg (26.6 kPa) pressure was applied to the stent for compression force, 1 N-m torque was applied to the stent in the Y direction for pure torsion force, and 1 N-m torque was applied to the stent in both the X and Z directions for bending-torsion force. The outside of the stent was modeled as a tube, with fixed upper and lower parts. The results of static simulation (deformation, von Mises stress) and fatigue analysis were obtained under each condition.

Fig. 3.

Images showing the distribution of boundary conditions. Two reference points (A and B) are created as constraint conditions.

200 mmHg (26.6 kPa) pressure was applied to the stent for compression force (a), 1 N-m torque was applied to the stent in the Y direction for pure torsion force (b), and 1 N-m torque was applied to the stent in both the X and Z directions for bending-torsion force (c).

The material properties used in structural and fatigue analyses were as follows: density, 6450 kg/m3; Young's modulus, 83 GPa; Poisson's ratio, 0.33; tensile yield strength, 690 MPa; compressive yield strength, 250 MPa; and tensile ultimate strength, 1.9 GPa.

2.4. Fatigue analysis

Stress/strain analysis is used to obtain information regarding the durability of stents. The results of stress/strain analysis can be used to determine an appropriate range for design safety, set experimental conditions, and select a suitable stent size for durability testing. Fatigue-related stent fracture can cause recurrence of respiratory symptoms and tracheal perforation in canines with TC. Typically, the fatigue safety factor is assessed using an engineering approach, such as evaluating the lifespan when subjected to stress or deformation.

After obtaining the alternating stress and mean stress values through stress/strain analysis, the Goodman diagram can be plotted to calculate the von Mises stress reversal and predict the fatigue lifespan. This is the most commonly used method to assess fatigue life in stents (Perry, Oktay & Muskivitch, 2002).

Fatigue analysis reveals the location and size of deformations when certain forces are applied to the stent, and can be used to predict the equivalent stress (Mpa) and fatigue life.

3. Results

3.1. Fatigue analysis of stents

The results of stress/strain analysis of the stents are shown in Fig. 4. We performed fatigue analysis on the three different stent designs (Table 1, Supplementary Figures S2–22). Since tracheal stents for canines need a guaranteed lifespan of at least 5 years, we set the target lifespan to 300,000 cycles. We observed that the use of a single-type stent (S6) versus a double-type stent (D6) did not affect the target lifespan, and the double-type stent (D7) model possessed a lifespan exceeding 1 million cycles. Therefore, the D7 model was deemed the most stable in an environment imitating the diverse forces within the trachea of a canine with TC. As the radial, axial, and bending forces on the stent material increased with increasing wire diameter, we believe that the stents we tested had structural properties that could improve intraluminal rigidity in the collapsed trachea, relative to previous stents.

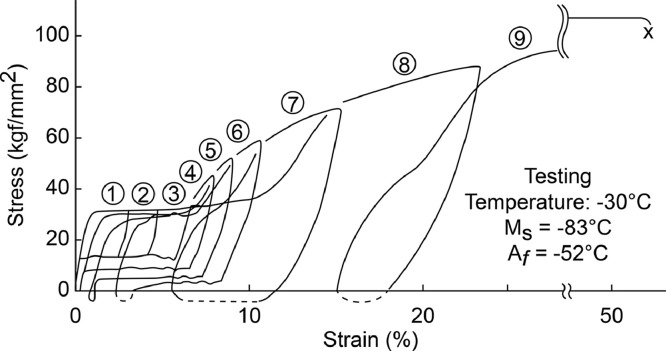

Fig. 4.

Stress–strain curve of stent material.

Table 1.

Structural rigidity and fatigue life of the three stents depending on each condition.

| Condition | Displacement (mm) | Equivalent stress (Mpa) | Fatigue (life cycle) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S6 | Compression | 0.00013416 | 2.4692 | > 1,000,000 |

| Torsion | 0.030915 | 120.12 | 165,000 | |

| Bending + Torsion | 0.047213 | 149.51 | 165,000 | |

| D6 | Compression | 0.0000796 | 1.6047 | > 1,000,000 |

| Torsion | 0.019836 | 108.67 | 263,000 | |

| Bending + Torsion | 0.021588 | 111.5 | 227,000 | |

| D7 | Compression | 0.000058123 | 0.55498 | > 1,000,000 |

| Torsion | 0.0083033 | 79.283 | > 1,000,000 | |

| Bending + Torsion | 0.018736 | 81.887 | > 1,000,000 |

The degree of displacement, equivalent stress, and fatigue life of the three stent designs are shown when three different types of forces of compression, torsion, and bending/torsion are applied for 300,000 cycles.

3.2. Fatigue criteria

We applied Goodman diagrams to predict the fatigue life of the stents. Goodman diagrams are defined, in terms of stress, as follows:

where a, m, Su, and -1 represent stress amplitude, mean stress, ultimate tensile stress and equivalent alternating stress (Se), respectively. -1 and u are determined by the material properties verified in the experimental cycle fatigue tests. a is the stress amplitude, which can be calculated as . m is the mean stress, which is given by . Su is the ultimate tensile stress, which can be obtained from material properties. a, m, and Su can be used to calculate the von Mises stress reversal. Se and fatigue life can be calculated by comparing this value to the S–N Curve.

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to measure and compare the fatigue life of tracheal stents used in dogs using finite element analysis. D7 was considered to be the most stable against material fracture when a tracheal stent was placed in dogs diagnosed as having severe TC. In this study, we were able to present a method for evaluating the durability of canine tracheal stent.

The FEM is an important tool to evaluate the mechanical performance of materials. There are various factors that can influence stent fracture, but an existing stent fracture owing to loads that exceed its mechanical limits can be fatal for the patient. Past studies have measured stent fatigue by using FEM to analyze the stress distribution (Auricchio et al., 2016; Jovicic, Vukicevic & Filipovic, 2014). Several previous studies on computational assessment of stents are present in the field of interventional cardiology. Using finite element analysis, researchers have investigated the specific locations where stent fractures occur under cyclic loading (Jovicic et al., 2014). In addition, research to improve the fatigue endurance of novel stent designs and evaluate the degree of stent fracture under specific forces have also been performed (Auricchio et al., 2016; Kogure, Shiraiwa, Enoki & Suzuki, 2015). These studies have helped to assess the risk of stents in clinical settings. The advantages of FEM studies are that the fatigue life of a material can be ascertained through 3D simulation under diverse environmental conditions, such as complex material design, various loading conditions, and cyclic loading of specific forces, making it possible to design a material with long-term stability, and reduce time and cost associated with manufacturing and testing the stents.

Von Mises stress is a numerical representation of material stress to determine if a structure will fail. If the forces on the material exceed the maximum von Mises stress value, the material will not withstand the load conditions and will fail. By comparing the equivalent stress values on materials, it is possible to verify the magnitude of stress at the materials’ limits.

Medical stents are used in environments where they are continuously subjected to fatigue loads; hence, ensuring they have sufficient durability against fatigue is crucial. Apart from the Goodman diagram used in this study, other methods such as Soderberg, Gerber, and Morrow, all featuring graphs depicting the relationship between fatigue strength and strain rate, can also be used. However, the Goodman diagram takes into account both the complexity of stent design and precise requirements of stents. It predicts fatigue life more precisely, ensuring sufficient stability against stent fatigue. Hence, the Goodman diagram is commonly used for fatigue analysis of medical stents (Auricchio et al., 2016; Jovicic et al., 2014).

When cyclic loading of a specific force is applied, it may cause displacement leading to stent fracture. The smaller the displacement, the longer the fatigue life and the lower the likelihood of fracture. In our study, displacement was the smallest for D7, followed by D6, then S6, indicating that D7 exhibited the longest fatigue life.

In veterinary medicine, there are no established specifications regarding stents to be implanted in animals. Almost no research has evaluated stents made for canines. Clinical case reports on stent use in canines have been diverse, including tracheal, urethral, biliary, esophageal, and colonic stents (Culp, Macphail, Perry & Jensen, 2011; Hill, Berent & Weisse, 2014; Lam et al., 2013; Lee, Lee, Jeong & Yoon, 2020; Yoon et al., 2017), but most of these used stents manufactured for use in humans. Further studies are required to evaluate stents that are customized for canines.

Our study demonstrates a method to assess the durability of tracheal stents for canines. Fatigue analysis, which assesses stent stability, enabled us to make a comparative prediction of the fatigue life of three different stent designs, and confirmed that D7 possessed a superior fatigue life compared to S6 and D6. These findings suggest that, when using stents in patients with severe TC that can cause tracheal kinking, the D7 stent model will be more stable in the trachea than the D6 stent model previously used to treat TC.

This is the first study to compare and evaluate the fatigue of canine tracheal stents. Previous research lacked fatigue analysis specific to stents designed for dogs and predominantly focused on stents used in humans. The stability of stents can be assessed by measuring fatigue in various fatigue-inducing environments. The fatigue testing method used in this study could be a useful tool to provide theoretical data to support optimal stent usage in canines and reduce stent fracture in clinical settings. Moreover, alongside assessments using 3D simulations, clinical trials to evaluate the short- and long-term clinical outcomes in real patients should be conducted.

This study had some limitations. It is impractical to perform an experiment that reflects the clinical characteristics of real patients, and, thus, we were only able to perform simulations. As it is difficult to acquire specific data for individual patients regarding the extent of tracheal damage, strength, or the external forces exerted on the trachea, the physical characteristics of actual patients cannot be replicated exactly in the 3D simulation. Thus, we were unable to account for the specific effects of stent fatigue resistance in different patients. To accurately reproduce the biological characteristics of affected dogs, further research to devise imaging techniques that can assess the tracheal geometry of refractory TC or to develop animal models for TC in dogs or rabbits based on their clinical grades is necessary.

5. Conclusions

In this study, fatigue analysis of stents was conducted through cyclic loading by applying a virtual tracheal stent environment through FEM. When a tracheal stent is applied to a dog with severe TC, more precise design and experiments are required to examine whether the characteristics of fatigue can change depending on the periodic symptoms and the dog's condition. Further research is needed to develop an effective evaluation method for stents applied to dogs.

Ethical statement

This research uses a 3D computer simulation and does not involve humans or animals; and therefore requirement of ethical approval/informed consent is not applicable to this study.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Hun-Young Yoon: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. Jin-Young Choi: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgment

None.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.vas.2024.100341.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- Auricchio F., Constantinescu A., Conti M., Scalet G. Fatigue of metallic stents: From clinical evidence to computational analysis. Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 2016;44(2):287–301. doi: 10.1007/s10439-015-1447-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culp W.T., Macphail C.M., Perry J.A., Jensen T.D. Use of a nitinol stent to palliate a colorectal neoplastic obstruction in a dog. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2011;239(2):222–227. doi: 10.2460/javma.239.2.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durant A.M., Sura P., Rohrbach B., Bohling M.W. Use of nitinol stents for end-stage tracheal collapse in dogs. Veterinary Surgery. 2012;41(7):807–817. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-950X.2012.01037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill T.L., Berent A.C., Weisse C.W. Evaluation of urethral stent placement for benign urethral obstructions in dogs. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 2014;28(5):1384–1390. doi: 10.1111/jvim.12412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston S.A., Tobias K.M. Elsevier Health Sciences; Amsterdam: 2017. Veterinary surgery: Small animal expert consult-e-book: 2-volume set. [Google Scholar]

- Jovicic G.R., Vukicevic A.M., Filipovic N.D. Computational assessment of stent durability using fatigue to fracture approach. Journal of Medical Devices. 2014;8(4) doi: 10.1115/1.4027687. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.H., Choi J.Y., Yoon H.Y. Evaluation of mechanical properties of self-expanding metal stents for optimization of tracheal collapse in dogs. Canadian Journal of Veterinary Research. 2022;86(3):188–193. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogure R., Shiraiwa T., Enoki M., Suzuki T. Evaluation of torsional fatigue behavior of coronary stents. Materials Transactions. 2015;56(8):1257–1261. doi: 10.2320/matertrans.M2015075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lam N., Weisse C., Berent A., Kaae J., Murphy S., Radlinsky M., Gingerich K. Esophageal stenting for treatment of refractory benign esophageal strictures in dogs. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 2013;27(5):1064–1070. doi: 10.1111/jvim.12132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D.E., Lee H.E., Jeong S.W., Yoon H.Y. Application of Billroth II gastrojejunostomy and a biliary stent in a dog with gastric adenocarcinoma and the associated extrahepatic biliary obstruction. Turkish Journal of Veterinary and Animal Sciences. 2020;44(2):473–480. doi: 10.3906/vet-1912-49. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J., Yun S., Lee I., Choi M., Yoon J. Fluoroscopic characteristics of tracheal collapse and cervical lung herniation in dogs: 222 cases (2012–2015) Journal of Veterinary Science. 2017;18(4):499–505. doi: 10.4142/jvs.2017.18.4.499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard C.D., Johnson L.R., Bonadio C.M., Pollard R.E. Changes in tracheal dimensions during inspiration and expiration in healthy dogs as detected via computed tomography. American Journal of Veterinary Research. 2009;70(8):986–991. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.70.8.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittleman E., Weisse C., Mehler S.J., Lee J.A. Fracture of an endoluminal nitinol stent used in the treatment of tracheal collapse in a dog. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2004;225(8):1217–1221. doi: 10.2460/javma.2004.225.1217. 1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moritz A., Schneider M., Bauer N. Management of advanced tracheal collapse in dogs using intraluminal self-expanding biliary wallstents. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 2004;18(1):31–42. doi: 10.1892/0891-6640(2004)18≤31:mOatci≥2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niemann J.T., Rosborough J.P., Niskanen R.A., Alferness C., Criley J.M. Mechanical “cough” cardiopulmonary resuscitation during cardiac arrest in dogs. American Journal of Cardiology. 1985;55(1):199–204. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(85)90328-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry M., Oktay S., Muskivitch J.C. Finite element analysis and fatigue of stents. Minimally Invasive Therapy and Allied Technologies. 2002;11(4):165–171. doi: 10.1080/136457002760273377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrini L., Wu W., Dordoni E., Meoli A., Migliavacca F., Pennati G. Fatigue behavior characterization of nitinol for peripheral stents. Functional Materials Letters. 2012;05(1) doi: 10.1142/S1793604712500129. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Polverino M., Polverino F., Fasolino M., Andò F., Alfieri A., De Blasio F. Anatomy and neuro-pathophysiology of the cough reflex arc. Multidisciplinary Respiratory Medicine. 2012;7(1):5. doi: 10.1186/2049-6958-7-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sura P.A., Krahwinkel D.J. Self-expanding nitinol stents for the treatment of tracheal collapse in dogs: 12 cases (2001–2004) Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2008;232(2):228–236. doi: 10.2460/javma.232.2.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng K.T., Brodbelt D.C., Pegram C., Church D.B., O'Neill D.G. Life tables of annual life expectancy and mortality for companion dogs in the United Kingdom. Scientific Reports. 2022;12(1):6415. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-10341-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Violette N.P., Weisse C., Berent A.C., Lamb K.E. Correlations among tracheal dimensions, tracheal stent dimensions, and major complications after endoluminal stenting of tracheal collapse syndrome in dogs. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 2019;33(5):2209–2216. doi: 10.1111/jvim.15555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisse C., Berent A., Violette N., McDougall R., Lamb K. Short-, intermediate-, and long-term results for endoluminal stent placement in dogs with tracheal collapse. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2019;254(3):380–392. doi: 10.2460/javma.254.3.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon H.Y., Choi J.W., Kim J.H., Kim J.H. Use of a double-wire woven uncovered nitinol stent for the treatment of refractory tracheal collapse in a dog: A case report. Veterinární Medicína. 2017;62(2):98–104. doi: 10.17221/15/2016-VETMED. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.