Abstract

The gut microbiota is a complex and dynamic ecosystem known as the ‘second brain’. Composing the microbiota-gut-brain axis, the gut microbiota and its metabolites regulate the central nervous system through neural, endocrine and immune pathways to ensure the normal functioning of the organism, tuning individuals’ health and disease status. Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), the main bioactive metabolites of the gut microbiota, are involved in several neuropsychiatric disorders, including depression. SCFAs have essential effects on each component of the microbiota-gut-brain axis in depression. In the present review, the roles of major SCFAs (acetate, propionate and butyrate) in the pathophysiology of depression are summarised with respect to chronic cerebral hypoperfusion, neuroinflammation, host epigenome and neuroendocrine alterations. Concluding remarks on the biological mechanisms related to gut microbiota will hopefully address the clinical value of microbiota-related treatments for depression.

Keywords: depression

Introduction

Depression is a ubiquitous and debilitating neuropsychiatric disease that impairs behaviour, feelings, thoughts and overall well-being.1 According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (fifth edition), five or more depressive symptoms within a 2-week period are required to determine the presence of a depressive episode, including depressed mood or anhedonia (loss of interest or pleasure), appetite or weight disturbance, insomnia or hypersomnia, poor concentration, fatigue or loss of energy, psychomotor agitation or retardation, feelings of worthlessness or excessive guilt and suicidality.2 Globally, approximately 280 million people, that is, 3.8% of the total population worldwide, suffer from depression, which has become the third leading cause of disability.3 The pathophysiology of depression is an intricate process involving neural, endocrinal and immune pathways.4 With a deeper understanding of the pathogenesis of depression, recent research has revealed an essential role of gut microbiota in depression.

The gut microbiota is a dynamic organ that affects the activities of the autonomic nervous, enteric, neuroendocrinal and immune systems.5 The gut microbiota participates in the maintenance of the intestinal barrier, fibre metabolism, vitamin synthesis and drug metabolism.6–8 Beyond its effects on material metabolism, the gut microbiota affects the nervous system by regulating the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA) and producing neurologically active substances.9 10 The interaction between the central nervous system (CNS) and gut microbiota is termed the microbiota-gut-brain axis. A growing body of research reveals a complex interplay between the microbiota-gut-brain axis and psychiatric comorbidities, such as anxiety,11 bipolar disorder,12 schizophrenia,13 obsessive-compulsive disorder,14 substance use disorder15 and depression.16 17 In the gut-brain axis, alterations in gut microbial metabolites lead to abnormal physiological responses in microbial dysbiosis.

Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) are the primary metabolites of the gut microbiota produced via saccharolytic fermentation of non-digestible carbohydrates.18 SCFAs are natural ligands for free fatty acid receptors 2 and 3 (FFAR2/3), which are widely found in enteroendocrine, immune and neural cells.19–22 Many studies have indicated essential interactions between depressive episodes and gut microbiota metabolism. SCFAs act as essential mediators in the microbiota-gut-brain axis and play a vital role in the neurobiological mechanisms of depression. In the last decade, the specific approach by which gut microbiota metabolites influence the neural adaptation underlying brain circuitry has gradually been elucidated. This review summarises the interplay between the main gut microbiota metabolites—SCFAs, and the biological mechanisms of depression. We hope that illustrating the biological mechanisms related to SCFAs from the gut microbiota will shed light on novel treatment strategies for depression.

Gut microbiota and its abnormal metabolism in depression

Gut microbiota

Gut microbiota, including bacteria, fungi, archaea and viruses, inhabit the large surface area of the alimentary canal in humans.23 The human fetus is thought to be germ-free prior to delivery. Infant gut microbiota mature by approximately 1–2 years of age and become similar to those of adults in terms of diversity, composition and physiology.24 The human gut microbiota contains approximately 1000–5000 different species and is composed of several dominant phyla: 90% Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes and 10% Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, Fusobacteria and Verrucomicrobia.25 Approximately 100 trillion microorganisms vary across the digestive tract, and the colon contains the largest population of bacteria (3.8×1013).26 Due to both strain-level and host-level differences, including structural variants of the microbial genome, inter-individual variation in host genetics and differences in environmental exposure, composition and growth rates of the gut microbiota vary considerably in human individuals.27

The human gut microbiota is closely linked to the CNS through the regulation of neural, endocrine and immune communication lines.28 The composition and abundance of the gut microbiota are determined by many factors, such as diet, antibiotics, stress, age, genetics and environmental toxins.29–32 In a typical human digestive system, the host interacts with the gut microbiota in a mutually beneficial manner; the digestive tract offers a conducive environment for the inhabitation and survival of the microbiota, while the microbiota performs pivotal roles in preserving intestinal health, including nutrient metabolism and intestinal protection.33 Microbial metabolism mediates microbiota-gut-brain communication through its metabolites that act as or affect neurotransmitters, hormones, or immune modulators.34–36 These metabolites, such as SCFAs, function as secondary substrates or signalling molecules to complement multiple processes that cannot be carried out alone by host metabolites.37 Accordingly, disturbing the gut microbiota metabolism impairs physiological activities in the human body.

Gut dysbiosis

Gut dysbiosis refers to the imbalance of symbiotic microorganisms in the gastrointestinal tract, including the expansion of new bacterial groups and significant perturbations in symbiont composition.38 For example, patients suffering from inflammatory bowel disease often have gut dysbiosis, exhibiting lower diversity but a higher density of gut microorganisms on the surface of the intestinal mucosa.39 Subsequently, perturbations of the gut microbiome may precipitate psychiatric symptoms through their adverse effects on the brain.40 Gut dysbiosis is involved in the progression of mental disorders. A large population study indicated that the application of antimicrobials also disrupts the homeostasis of the gut microbiota and increases the risk of depression and anxiety, amplifying with multiple exposures.41 Moreover, gut dysbiosis induces neuroinflammation through disturbances in the gut microbiota and elicits a series of CNS symptoms in patients with autism spectrum disorder.42 43 It has been reported that patients with schizophrenia show gut dysbiosis with a decreased microbiome α-diversity index and changes in gut microbial composition compared with healthy controls.44

Alterations in gut microbiota composition and metabolism resulting from gut dysbiosis are closely related to a series of psychopathological processes, including inflammatory responses, abnormal protein degradation and heritable mutations.45 46 Gut dysbiosis also directly affects the synthesis and secretion of neurotransmitters, such as 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT), dopamine, glutamate, norepinephrine and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) in the gastrointestinal tract, while the regulation of the CNS by neurotransmitters impacts the microbial composition and abundance.47–49 Gut dysbiosis induces the breakdown of intestinal barrier integrity by reducing the expression of proteins involved in tight junctions such as claudin-5 and occludin.50 The loss of goblet cells leads to reduced mucus secretion and the thinning of the mucus layer. Consequently, pathobionts and toxic metabolites are translocated into the blood, resulting in chronic local and systemic inflammatory responses.34 51 Chronic low-grade inflammation decreases the expression of 5,6,7,8-tetrahydrobiopterin, which is a co-factor of multiple amino acid-converting enzymes responsible for the biosynthesis of neurotransmitters such as tryptophan, 5-HT, dopamine and norepinephrine.52 Therefore, neurotransmitter production is disrupted. These results demonstrate that gut dysbiosis affects the activities of the gut microbiota, initiates a cascade of pro-inflammatory pathways and disrupts the production of neurotransmitters, which are tightly linked with the occurrence of neuropsychiatric disorders.

Current research has confirmed that the composition and abundance of gut microbiota in patients with depression differ significantly from those of healthy controls, with patients suffering from depression having a higher proportion of Bacteroidetes and Proteobacteria and a lower proportion of Firmicutes, Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus.53–55 Animal studies have also reported similar findings, with depression models exhibiting an increased abundance of Bacteroidetes and a decreased abundance of Firmicutes.56 However, several studies have shown different relative proportions in individuals with depression compared with healthy controls. Zheng et al 57 reported that the relative abundance of Bacteroidetes was lower in patients with depression than in healthy controls. These conflicting results may be attributed to differences in sample sizes, demographic disparities, screening criteria of the recruited patients and disparate sequencing and bioinformatics techniques. Nevertheless, it has been consistently indicated that depression corresponds with marked alterations in gut microbiota composition.

A lower abundance of SCFA-producing bacteria (eg, Faecalibacterium) was observed in depression.58 Additionally, Coprococcus, a bacterial species that produces butyrate, was found to be diminished in patients with depression.59 Coprococcus plays a significant role in maintaining perceived health status, physical functioning, vitality, emotional well-being and social functioning. Various clinical trials and analyses have demonstrated that restoration of the microbiota with probiotics ameliorates depressive-like behaviours in patients with depression, which also confirms essential interactions between depression and the metabolism of the gut microbiota.60–62

Effect of gut microbiota-derived SCFAs on depression

Metabolism and physiological effects of SCFAs

SCFAs are monocarboxylic acids with two to five carbon atoms derived from the fermentation of dietary carbohydrates in the host intestine.18 The vast majority of circulating SCFAs are derived from gut microbial fermentation and absorbed in the colon.63 Diet, microbial composition and gut transit time have an impact on the fermentation of dietary fibres. Humans generally produce approximately 500–600 mmol of SCFAs per day. SCFAs mainly consist of acetate (C2), propionate (C3) and butyrate (C4) in a ratio of 60:20:20.64 Multiple gut bacteria with diverse genetic potentials participate in the anaerobic fermentation of different SCFAs. In this regard, acetogenic commensal bacteria in the gut synthesise acetate from CO2 and as an electron source, where Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes preferentially generate propionate, and Firmicutes (Eubacterium, Anaerostipes, Roseburia and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii) predominantly synthesise butyrate and degrade indigestible polysaccharide molecules.65–68 Colonocytes take up the majority of SCFAs through H+-linked monocarboxylate transporters and sodium-linked monocarboxylate transporters and use them to maintain intestinal barrier function.69 Most SCFAs are transmitted to hepatocytes through portal circulation and are metabolised as an energy source.70 Only a fraction of acetate, propionate and butyrate reach the systemic circulation and exert physiological effects elsewhere.63

SCFAs in the systemic circulation can cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and have a pivotal impact on the microbiota-gut-brain crosstalk.71 72 The high expression of monocarboxylate transporters in endothelial cells facilitates the penetration of SCFA through the BBB.73 In human cerebrospinal fluid, the concentration of SCFAs is as follows at physiological levels: 0–171 µM acetate, 0–6 µM propionate and 0–2.8 µM butyrate.70 SCFAs can also regulate the transfer of nutrients and molecules involved in the maintenance of BBB integrity, directly influencing brain development and CNS homeostasis.74 Additionally, SCFAs mediate a plethora of basic behavioural and neurological processes through the modulation of the immune system, HPA axis and tryptophan metabolism, along with the synthesis of several metabolites such as neurotransmitters that have neuroactive properties.75–77 A disease-promoting imbalance in the human gastrointestinal tract can change the composition and abundance of the gut microbiota and alter the normal formation of metabolites, which elicits disease development or severity.

The role of SCFAs in the pathological mechanisms underlying gut microbiota-associated depression

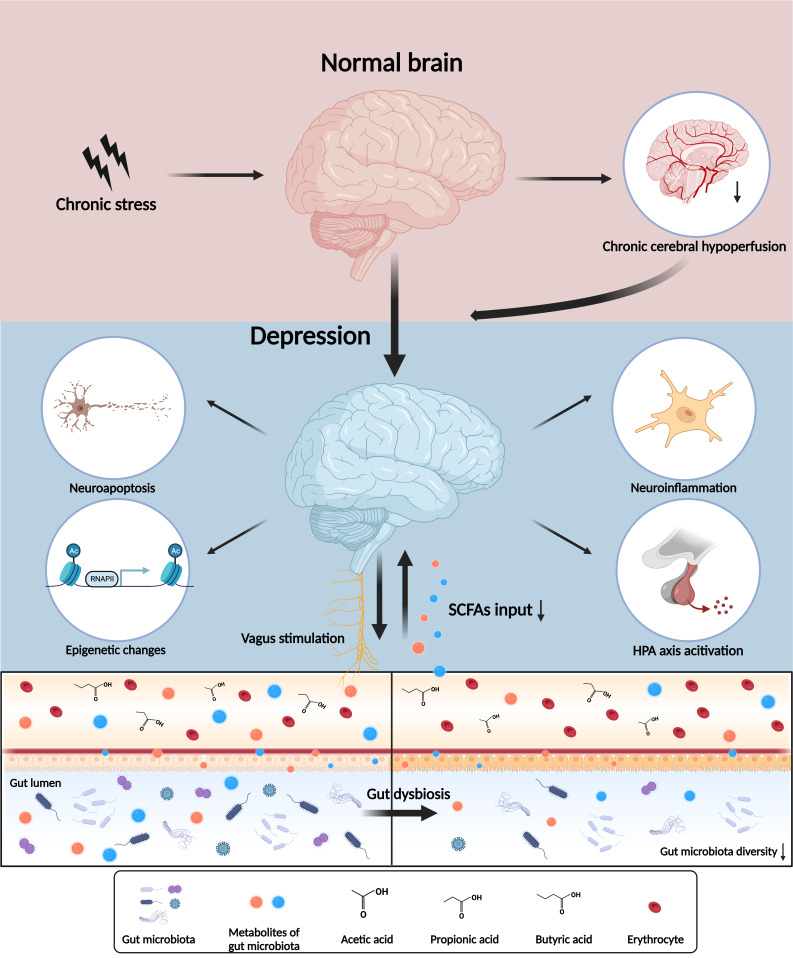

SCFAs are the major mediators of the microbiota-gut-brain axis in the pathophysiology of depression. Chronic stress, along with gut dysbiosis, interferes with the metabolism of SCFAs and accelerates the dysfunction of the microbiota-gut-brain axis in depression. SCFAs have a neuroprotective effect and participate in the complex biological mechanisms and pathological processes involved in the onset and progression of depression, including chronic cerebral hypoperfusion (CCH), neuroinflammation, epigenetic modifications and neuroendocrine alterations (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Microbiota-gut-brain axis and central nervous system dysfunctions in depression. The interaction of the microbiota-gut-brain axis and depression are involved in the neural, endocrine and immune systems. Chronic stress induces a series of psychopathological processes including chronic cerebral hypoperfusion, neuroinflammation, epigenetic alteration, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and vagus activation through gut microbiota and its metabolites. SCFA, short-chain fatty acid.

SCFAs and chronic cerebral hypoperfusion

CCH has emerged as a major contributor to cognitive decline and degenerative processes that predispose the brain to mental disorders.78 CCH induces inadequate transportation of nutrients and oxygen in cerebral cells and aggravates brain injury, including BBB dysfunction,79 metabolic disturbance,80 activated neuroinflammation81 and neuroendocrine perturbation.82 In turn, the adverse consequences of repeated hypoperfusion/hypoxic events underline chronic cognitive and behavioural impairments (eg, memory deficits, anxiety and depression).83 Previous studies have indicated that CCH is closely associated with depression in animal models and humans.84 85

Bilateral common carotid artery occlusion (BCCAO) is adopted to model CCH-induced depressive behaviours in rats.85 Several recent studies have assessed the role of SCFAs in CCH-induced depression. Xiao et al 86 demonstrated that rats with BCCAO exhibit compromised gut barrier function and perturbed gut microbiota. The decrease in representative SCFA-producing flora results in hippocampal SCFA reduction in BCCAO rats that suffer from cognitive impairment and show depressive-like behaviours.86 Subsequently, rats were supplied with water containing a mixture of SCFAs (acetate, propionate and butyrate). SCFAs attenuated BCCAO-induced hippocampal neuroinflammation and neuronal apoptosis through the inhibition of nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB) and activation of the Erk1/2 pathway, accompanied by amelioration of cognitive decline and degenerative processes.86 NF-κB is a key transcription factor that regulates the expression of genes involved in immunity and inflammation. It should be noted that the intervention of oral SCFA intake could not be normalised in each animal, and it also elevates sodium intake. Hence, rebuilding the gut microbiota by faecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) appears to be a more reasonable method to replenish these beneficial metabolites.

Reestablishment of the gut microbiome has emerged as a potential approach for treating CCH-induced depression and cognitive impairment. Restoring balanced gut flora in BCCAO rats through FMT restores gastrointestinal motility and ameliorates hippocampal neuronal apoptosis and cognitive dysfunction.87 88 Nevertheless, it is still difficult to confirm whether FMT and SCFAs exert a protective or therapeutic effect on CCH or both. FMT may not eradicate a disease by itself, but it can replenish SCFAs and alleviate secondary impairment induced by the dysfunction of the microbiota-gut-brain axis.

SCFAs and neuroinflammation

The essential role of inflammation in depression has been widely investigated in recent decades, with the microbiota-gut-brain axis emerging as a key intermediate regulator.89–92 Gut dysbiosis affects the onset and maintenance of neuroinflammation in depression by altering SCFA metabolism.93 In chronic mild stress mouse models, physiological stress initiates alterations in the gut microbiota characterised by significantly decreased faecal microbial diversity.94 Rats with depressive-like behaviours exhibit a decreased relative abundance of SCFA-producing gut microbes and reduced serum levels of SCFAs, which are closely associated with cytokine expression and inflammatory pathway activation in neuroinflammation.95

The levels of cytokines in the blood, including interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), are significantly higher in patients with depression than in healthy controls.96 These pro-inflammatory cytokines, particularly IL-6, IL-1β and TNF-α, promote the generation of T helper 17 (Th17) cells, which are strongly implicated in depression and other CNS diseases.97 Th17 cells may come in two ways: peripheral Th17 cells, which are probably released from the lamina propria of the small intestine, can directly infiltrate the brain parenchyma through the BBB leakage induced by Th17-derived cytokines,98 or they may originate from CD4+ T cells in the brain when stimulated by pro-inflammatory cytokines.99 In turn, the products of Th17 cells, interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and IL-17A, could promote neuroinflammation. IFN-γ has been proposed to confer a signal for Th17 infiltration in the CNS and enhance synapse elimination.100 IFN-γ and IL-17A contribute to the proliferation, polarisation and activation of microglia.101 102 Microglia are a major source of cytokines among all glial cells in the CNS.103 Microglia polarise to the M1 phenotype and release reactive oxygen species (ROS) and pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α.104 ROS, such as hydroxyl radicals (OH−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and the superoxide anion (O2 −), impair neurogenesis, synaptic plasticity and neuronal transmission as a consequence of oxidative stress-induced mitochondrial injury and neuronal apoptosis.105 In summary, neuroinflammation mediated by pro-inflammatory cytokines evokes a detrimental response in the CNS that aggravates depression.

Apart from indirect mechanisms via chemical mediators, the onset of neuroinflammation is also activated through direct pathophysiological mechanisms via the vagus nerve pathway.106 The vagus nerve can stimulate infiltrated or resident immune cells (eg, microglia and dendritic cells) in the vicinity of the perineural sheath. Activated immune cells boost the immune response by relaying signals from pro-inflammatory cytokines to the CNS, which induces a series of physiological and behavioural responses.107 Pro-inflammatory cytokines in the gastrointestinal tract stimulate the vagus nerve and activate the HPA axis, which influences the central stress circuitry.108 In contrast, stimulation from cholinergic signalling enables the vagus nerve to decrease the inflammatory response and production of pro-inflammatory cytokines.109 Several studies revealed a key role of the subdiaphragmatic vagus nerve in the onset of depression by regulating the brain-gut microbiota axis.107 110 Additionally, the subdiaphragmatic vagotomy exhibited an antidepressant effect in lipopolysaccharide administration mice, which indicated an essential role of the vagus nerve in depression.111 Apart from subdiaphragmatic vagotomy, vagus nerve stimulation has been developed as an emerging treatment for depression.112 113 These results indicate the potential role of the vagus nerve in depression treatment.

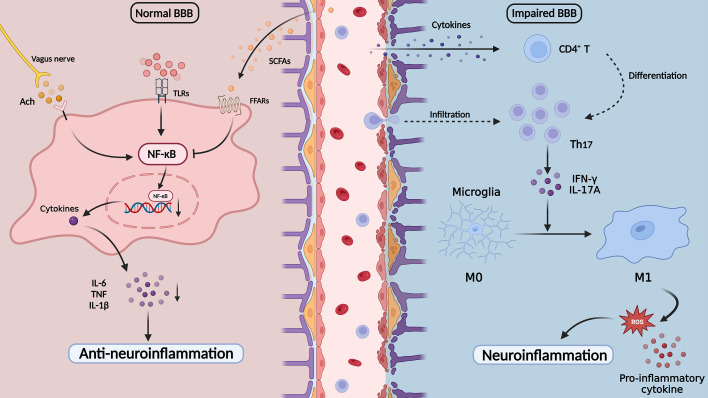

Gut microbiota-derived SCFAs play a vital role in anti-inflammatory actions owing to their maintenance of gut-brain permeability and constant input to the CNS for the homeostasis of microglia.114 115 SCFAs decrease the permeability of both the intestinal barrier and the BBB. SCFAs, especially acetate, propionate and butyrate, have been reported to exhibit protective effects on the intestinal barrier as energy substrates.116 Butyrate enhances the expression of aryl hydrocarbon receptors and hypoxia-inducible factor 1α, which upregulates the levels of IL-12 through regulating the mammalian target of rapamycin and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3.117 IL-12 is a protective cytokine that contributes to resisting inflammatory stimuli and maintaining intestinal homeostasis. These findings suggested that SCFAs have an anti-inflammatory effect on maintaining gut homeostasis. In the CNS, propionate preserves the BBB through FFAR3 on the surface of endothelial cells.118 SCFAs protect hippocampal neurons from injury to the mitochondrial membrane potential and ROS accumulation.87 In addition, the regulatory function of SCFAs protects the CNS from peripheral inflammatory cytokines and toxic substances. SCFAs have a direct anti-inflammatory effect on microglial proliferation and activation by binding FFARs, as well as activating FFARs on neutrophils and dendritic cells to alleviate systemic inflammation.119 120 SCFAs bind to GPR41 on microglia, regulate microglial proliferation and inflammatory status and inhibit pro-inflammatory signalling pathways via NF-κB inhibition and Erk1/2 activation.86 121 Butyrate also activates GPR109A-mediated signalling pathways to downregulate NF-κB signalling in microglia. The inhibition of pro-inflammatory enzymes (inducible nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase-2) and pro-inflammatory cytokine (TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6) production in microglia prevents the onset and process of neuroinflammation.122 IL-10 and CD26, markers reflecting the anti-inflammatory status of microglia, are increased after butyrate treatment, indicating the neuroprotective effects of SCFAs in vivo.123 The intricate interactions between neuroinflammation and anti-inflammation through the SCFA-mediated microbiota-gut-brain axis are involved in the pathophysiology of depression (figure 2).

Figure 2.

The neuroinflammation and short-chain fatty acids in depression. Cytokines pass through the impaired BBB and promote the brain CD4+ T cells to the Th17 cells and peripheral Th17 cell infiltration. Th17 cells activate microglia and release pro-inflammatory cytokines and ROS, which induce the onset of neuroinflammation. SCFAs could inhibit microglia activation by inhibiting the NF-κB pathway and play an important role in anti-neuroinflammation processes. ACh, acetylcholine; BBB, blood-brain barrier; FFARs, free fatty acid receptors; IFN-γ, interferon-γ; IL-12, interleukin-12; IL-17A, interleukin-17A; IL-6, interleukin-6; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa-B; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SCFAs, short-chain fatty acids; Th17, T helper 17 cells; TLRs, toll-like receptors; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

SCFAs and host epigenome

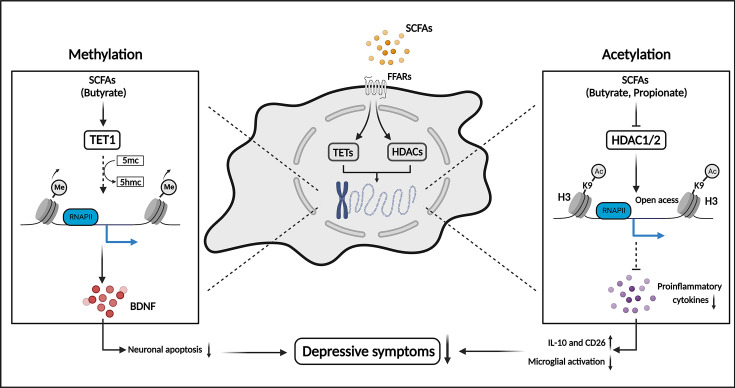

The epigenome describes the heritable and reversible alterations of the genome that change DNA packaging or associated proteins without affecting nucleotide sequences.124 Epigenetic modifications include histone modifications, DNA methylation and non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs). These modifications integrate abundant environmental messages into phenotypes by regulating the three-dimensional architecture of chromatin. Therefore, epigenetic modifications have been implicated in the pathogenesis of depression, manipulation of the HPA axis, neuroinflammation, excitatory-inhibitory balance and monoamine pathways.125–129 Epigenetic pathways, especially DNA methylation and histone modifications, have been extensively investigated in depression and have been proven to be tightly correlated with the metabolism of the gut microbiota.130 SCFAs from the gastrointestinal tract also have a vital effect on epigenetic modifications as mediators in the CNS of patients with depression. In this section, we introduce the molecular mechanisms and interactions between the gut microbiota, SCFAs and host epigenome in depression. Figure 3 shows the neuroprotective effect of SCFAs through histone acetylation and DNA methylation in depression.

Figure 3.

SCFAs alleviate depressive symptoms by regulating epigenetic modifications in the CNS. SCFAs, especially propionate and butyrate, regulate the DNA methylation and histone acetylation in the neural cells and microglia. The decreased DNA methylation promotes BDNF synthesis and inhibits neuronal apoptosis. The increased histone acetylation decreases pro-inflammatory cytokines and inhibits microglia activation. These modifications elicited by SCFAs jointly decrease depressive symptoms. 5hmc, 5-hydroxymethylcytosine; 5mc, 5-methylcytosine; Ac, acetylation; BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor; CD26, dipeptidyl peptidase 4; FFARs, free fatty acid receptors; H3K9, histone 3 lysine 9; HDACs, histone deacetylases; IL-10, interleukin-10; Me, methylation; RNA PII, RNA polymerase II; SCFAs, short-chain fatty acids; TETs, Ten-eleven translocation enzymes.

Histone modifications

Histones are the basic elements of nucleosomes. An octamer of two distinct copies of four types of histones (H2A, H2B, H3 and H4) wrapped with long DNA chains composes the nucleosome core particles. The -NH2 terminus of histone tails can be reversibly modified by several functional groups, such as acetyl and methyl groups, and the accessibility of genomic DNA is altered due to the disruption of electrostatic interactions between the modified residues and nucleic acids, thereby manipulating cell activities (eg, DNA replication, DNA repair, transcriptional activities and cell cycle progression).131 The addition and deletion of specific functional groups are regulated by antagonistic enzymes. For instance, histone acetyltransferases and histone deacetylases (HDACs) jointly control the addition or deletion of acetyl groups on the histone tails.132 HDACs could be divided into five major families, including class I (HDACs 1, 2, 3, 8), class IIA (HDACs 4, 5, 7, 9), class IIB (HDAC 6, 10), class III (SIRT1–7) and class IV (HDAC11), and the class I members play a key role in the initiation and progression of depression.

Epigenetic modifications in the CNS, particularly histone acetylation, are closely associated with the activation of glia and immune cells during the pro-inflammatory response.133 134 These modifications control microglial polarisation and inflammatory cytokine expression.123 Several studies have demonstrated the role of HDAC in the immune response, which epigenetically modulates gene expression and the inflammatory response.135 SCFAs are well-known HDAC inhibitors (HDACi), together with histone acetyltransferases, that upgrade histone and non-histone protein acetylation.136 Among the SCFAs, butyrate is the most potent and extensively applied in neuropsychiatric studies as a class I and class II HDACi. Butyrate induces an increased level of histone acetylation and upregulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) levels in the corticolimbic portions of the mouse frontal cortex.137 BDNF is an important protein of growth factor, which plays a crucial role in neuronal growth and synaptic plasticity in brain development.138 139 Patients with depression show decreased levels of BDNF in the serum and cerebrospinal fluid.140 141 Bifidobacterium longum NCC3001, a SCFA-producing bacteria, has been demonstrated to upregulate BDNF, regulate neuronal plasticity in the enteric nerve and alleviate depression-like behaviours in mice.142 Moreover, fluoxetine (a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressant) combined with butyrate substantially decreased behavioural despair compared with fluoxetine treatment alone, with an increasing transcript level of BDNF,137 suggesting that upregulation of BDNF expression might be important for alleviating depressive behaviours.

Propionate or butyrate treatment has been reported to promote histone 3 lysine 9 acetylation in the brain, with decreased HDAC1 expression in microglia.143 SCFA treatment reduces microglial activation and the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF‐α, IL‐1α and IL‐1β, and represses neuronal apoptosis and neurodegeneration to alleviate depressive-like behaviours.143 Lactate, an important intermediate of SCFAs, has reversible effects on stress-induced depression.144 The effects of lactate on HDACs have also been studied through distinct epigenetic mechanisms. In mouse models, lactate treatment increased the levels of hippocampal class I HDAC, especially HDAC2/3, enhanced resilience to stress and rescued social avoidance and anxiety.145 These results indicate that class I HDACs could be potential targets for reversing chronic unpredictable stress-induced depressive-like behaviours, and natural compound SCFAs may serve as antidepressants owing to their high security. However, further research has indicated the opposite roles of class I HDACs during different periods of depression. Treatment with the HDAC2/3 inhibitor CI-994 inhibited the activities of HDAC2/3 and alleviated depression-like behaviours in mice.145 HDAC2 and HDAC3 play different roles in the progression of depression. Thus, it remains difficult to elucidate the pathways by which lactate regulates HDAC2/3 during different periods of depression. These inconsistent results demonstrated that targeting HDAC2/3 may only serve as a therapeutic antidepressant, but not as a prophylactic.

DNA methylation

DNA methylation involves the covalent addition of a methyl group to the pyrimidine ring of cytosines in CpG regions, which appear in approximately 70% of the gene promoters.146 DNA methylation is also a dynamic and reversible process similar to histone modifications, whereas methylation in CpG regions transforms the genes into an inaccessible state and represses transcriptional activities. DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) catalyse DNA methylation by transferring the methyl group from S-adenyl methionine to carbon-5 of cytosine to form 5-methyl cytosine.147 There are five major categories of DNMTs in mammals: DNMT1, DNMT2, DNMT3a, DNMT3b and DNMT3L. Ten-eleven translocation (TET) enzymes are involved in the demethylation of CpG regions by oxidising methylated bases, which activate gene expression and transcriptional activities.

Depression has been linked to alterations in BDNF, which influences GABA neurotransmission, synaptic plasticity and neuronal activity.147 148 Patients with depression have a higher level of methylation at specific CpG regions within BDNF promoters than healthy controls, which results in decreased expression of BDNF in the hippocampus.149 Further research has investigated the effects of SCFAs on the methylation of BDNF promoters. Butyrate treatment in depressed mice restored the decreased TET1 level, which promoted the hydroxylation of the cytosine residue to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine, reduced DNA methylation and facilitated BDNF transcription, exerting antidepressant-like effects.150 These results link neural activities to the metabolism of the gut microbiome through epigenetic alterations, which may be crucial to the biological mechanisms underlying depression and potential therapeutic strategies.

Non-coding RNA

ncRNAs, including long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), circular RNAs and microRNAs (miRNAs), are significant mediators of normal transcriptional and translational processes, and their abnormal metabolism has been extensively reported in the pathogenesis of depression.151–153 However, interactions between the gut microbiome and ncRNAs in the CNS remain largely unknown.

The competitive endogenous RNA (ceRNA) hypothesis indicates that miRNAs compete for shared miRNA-binding sites in post-transcriptional control, which is the key for neurodevelopment and neurodegeneration.154 Recently, aberrant expression of ncRNAs was observed in the hippocampus of mice with gut dysbiosis. An integrated analysis found two lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA ceRNA regulatory networks in depressed mice induced by gut dysbiosis.155 Regulatory networks are primarily associated with inflammatory responses and the neurodevelopmental regulation of microbial-related pathological changes. One consisted of two lncRNAs (4930417H01Rik and AI480526), one miRNA (mmu-miR-883b-3p) and two mRNAs (Adcy1 and Nr4a2). The other consists of six lncRNAs (5930412G12Rik, 6430628N08Rik, A530013C23Rik, A930007I19Rik, Gm15489 and Gm16251), one miRNA (mmu-miR-377-3p) and three mRNAs (Six4, Stx16 and Ube3a).155 These molecules have been proposed as pivotal mediators of ncRNA adjustment in the microbiota-gut-brain axis, and have the potential to be applied as epigenetic biomarkers in gut microbial-related depression.

Although emerging evidence has revealed the crosstalk between ncRNAs and the gut microbiota in depression, it is still challenging to make a conclusive narrative about how alterations of the microbiota-gut-brain axis mediate ncRNA activities in the CNS. There are several limitations in the current investigations of ncRNAs to form homogeneous groups compared with histone modifications and DNA methylation. For instance, ncRNA levels tend to be affected by multiple factors, including environment, diet, exercise, ageing, alcohol consumption and drug abuse. Despite the clear implication, convincing evidence is still lacking to demonstrate how certain ncRNAs mediate specific signalling pathways in the microbiota-gut-brain axis, thereby influencing depression. Hence, unlike histone modifications and DNA methylation, it is difficult to construct a generalised framework to depict ncRNA regulation by gut microbial metabolites.

In sum, depression can be considered a slowly developing but multifaceted maladaptation to long-term environmental stressors.156 Maladaptive neuronal plasticity in regions implicated in depression pathogenesis, such as the hippocampus, has been shown to be relevant to allostasis of the brain through epigenetic pathways. Delayed addition or deletion of epigenetic modifications may explain the slow development and insignificant initial effects of antidepressants in treating depression. Disrupted gut homeostasis induces altered epigenetic regulators synthesised by the gut microbiota, such as acetate, butyrate and propionate, following the activation of neuroinflammation and other pathways by epigenetic reprogramming. The underlying mechanisms in the microbiota-gut-brain axis may play an important role in the long-term abnormal synaptic plasticity and behavioural response to stress in depression.

SCFAs and neuroendocrine alterations

SCFAs participate in modulating the metabolism of multiple neuroactive substances in the gastrointestinal and nervous systems. SCFAs ligate to G protein-coupled receptors, for example, GPR43 (FFAR2), GPR41 (FFAR3), GPR109A, OLFR78 and OR51E2, located on the surface of intestinal epithelial cells and enteroendocrine cells.157–160 In addition to serving as energy supplements for epithelial cells, SCFAs strengthen intestinal barrier integrity by enhancing glucose metabolism, lipid homeostasis and the expression of tight junction protein to promote gut health.161 SCFAs, especially butyrate, increase the expression of claudin-1 and induce the redistribution of occludin and zonula occludens-1 to repair and enhance gut barrier function.162 Furthermore, they induce the release of hormones and neuropeptides, such as glucagon-like peptide 1 and peptide YY from intestinal enteroendocrine cells and regulate gastric motility and digestive absorption, which might activate a signalling cascade that affects brain circuits related to appetite and food intake.163 164 Taken together, these findings suggest that SCFAs play a crucial role in maintaining energy metabolism and intestinal homeostasis.

In the microbiota-gut-brain axis, SCFAs are involved in the synthesis and release of peripheral neurotransmitters, including acetylcholine and 5-HT.165 166 The enterochromaffin cells in the gut synthesise >90% of the circulating 5-HT, which participates in regulating diverse gastrointestinal functions including motility and secretory reflexes.167 The stimulatory activities of SCFAs, especially acetate and butyrate, promote the expression of colonic tryptophan hydroxylase 1, the rate-limiting enzyme in 5-HT synthesis,168 suggesting that SCFAs are actively involved in host 5-HT biosynthesis and crosstalk between the microbiome and gut homeostasis. Owing to the permeability of the BBB, peripheral neurotransmitters may be unable to access the brain and directly affect the functioning of the CNS. However, serotonin in the peripheral blood circulation can regulate gastrointestinal movement and excretion and indirectly affect emotional, cognitive and behavioural responses through neuroendocrine pathways or vagal afferents.169 170 Some evidence also shows that SCFAs that are taken up through the BBB regulate the levels of neurotransmitters in the CNS. Intraperitoneal acetate resulted in altered glutamate, glutamine and GABA in the hypothalamus and increased anorexigenic neuropeptide expression.114 The disordered gut microbiota, especially Firmicutes, could regulate the levels of acetate, propionate and butyrate, which could elicit the metabolism disturbance of peripheral and central glycerophospholipid. As a result, the levels of tryptophan, 5-HT, 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid and indoleacetic acid were decreased in the hippocampus.171 As mentioned above, the metabolic disturbance of SCFAs elicits activation of a series of inflammatory pathways with increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and microglial proliferation and activation in the CNS. Meanwhile, the disturbance throws the normal biosynthesis of neuroprotective factors into confusion, such as BDNF. Ultimately, the levels of 5-HT are decreased due to neuronal apoptosis and metabolic dysfunction. Decreased circulating levels of 5-HT represent a classical biomarker indicating mental disorders like depression.172 These findings suggest that decreased levels of SCFAs can partly explain the altered expression of 5-HT and other neurotransmitters through the gut-brain axis in patients with depression.

SCFAs also alleviate stress-induced CNS dysfunction by ameliorating HPA axis activity. Specific pathogen-free mice receiving faecal microbiome colonisation at early postnatal life (3 weeks) instead of at a later stage exhibited reversed stress-associated physiological alterations on the HPA axis.173 This suggests that the gut microbiota is involved in the normal development of the HPA axis and neuroendocrine response to stress. In addition, after solely receiving SCFA administration, the expression of hypothalamic genes involved in the stress response is decreased, including corticotrophin-releasing factor and related receptors (corticotrophin-releasing factor receptor (CRFR) 1 and 2, mineralocorticoid receptor).174 The reactivity of the HPA axis leads to increased levels of serum cortisol, a stress hormone that increases access to energy stores and promotes protein and fat mobilisation.175 Colon-delivered SCFAs at high doses (174.2 mmol acetate, 13.3 mmol propionate and 52.4 mmol butyrate daily) and low doses (87.1 mmol acetate, 6.6 mmol propionate and 26.2 mmol butyrate daily) both increase the levels of serum SCFA and attenuate the cortisol response to acute psychosocial stress in healthy humans.176 It is speculated that SCFAs penetrating through the BBB are involved in HPA axis integration by rich innervations in and projections to the medial parvocellular paraventricular nucleus.176 These findings demonstrate the mechanisms by which SCFAs participate in the regulation of HPA axis responsiveness in depression.

Nowadays, ketamine, an N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist, has been proven effective against treatment-resistant depression due to its anti-inflammatory effect and regulation of neurotransmitters.177 Previous research also revealed alterations in the gut microbiota during ketamine treatment.178 Ketamine could amplify the Lactobacillus and maintain the level of Bacteroidales and Clostridiales at the genus level in mice.179 180 However, while the effect of ketamine on the composition and abundance of gut microbiota has been well illustrated, how ketamine regulates the metabolism of gut microbiota and its metabolites, such as SCFAs, is unclear. Hence, further studies should concentrate on the mechanisms by which ketamine regulates the metabolism of gut microbiota and its metabolites as a promising antidepression agent.

Potential application of gut microbiota and SCFAs in depression treatment

Nowadays, the medical treatment of depression is eminently pharmacological along with adjuvant treatments, such as transcranial magnetic stimulation,181 electroconvulsive therapy182 and psychological treatment.183 With a deeper understanding of bidirectional interactions between depression and gut microbiota, emerging evidence has indicated a promising prospect for microbiota-related interventions for depression. Maintaining microbiota-gut-axis homeostasis is the main purpose of restoring gut microbiomes. Dietary control, microorganism transplantation and beneficial substance administration have been extensively harnessed to improve the composition and abundance of gut microbiota in preclinical and clinical settings of depression treatment, which indicates the feasibility of the gut microbiota as a novel therapeutic target for depression.

Dietary interventions

Previous studies demonstrated a complex relationship between diet, gut microbiota and depression.184 The normal gut microbial composition and function depend on healthy dietary patterns, which contribute to the growth of commensal microbiota and the decline of pathogenic bacteria. Improving diet was proven to maintain gut barrier permeability and inhibit inflammation.185 Moreover, replenishing the essential macronutrients in healthy food choices is also a promising approach to improving depressive symptoms. Gut microbiota participates in the fermentation of carbohydrates into SCFAs in the colon. It was reported that increased intake of carbohydrates was associated with a decrease in the risk of depression.186 The Mediterranean diet (MD), characterised by rich dietary polyphenols and fibres, is thought to be beneficial to human health due to its enteroprotection and anti-inflammatory properties.187 Numerous studies reported that higher adherence to MD was related to a lower risk of depression.188–191 SCFAs, especially propionate and butyrate, are the key mediators for the interactions between MD and gastrointestinal health.192 SCFAs have been proven to be potentially beneficial metabolites that alleviate depressive-like behaviours via HDAC inhibition and exert anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects.86 Current research has applied oral administration or intraperitoneal injection of SCFAs in animal models to modulate depressive symptoms. For instance, oral intake of sodium butyrate restores paclitaxel-induced alterations in microbiota composition and gut barrier integrity, and decreases depressive-like and anxiety-like behaviours.193 Additionally, increased butyrate could participate in anti-inflammation, regulation of neurotransmitters, endocrine and BDNF along the gut-brain axis.194 Similarly, intraperitoneal injection of sodium butyrate inhibits neuroinflammation and oxido-nitrosative stress and prevents the onset and progression of depression.195 Additionally, an open-label and randomised trial increased gut microbial SCFAs indirectly by using an omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplement drink or capsule, which led to an increase in the SCFA-producing bacteria (eg, Bifidobacterium, Roseburia and Lactobacillus) in humans.196 These results indicate a promising approach to improving gut dysfunction and depressive symptoms by using SCFAs. However, several drawbacks limit their clinical application. Oral intake requires a high SCFA concentration in drinking water to guarantee sufficient absorption, while SCFA injection is difficult to apply and popularised owing to its invasiveness and transient effect. It is necessary to develop a safe and feasible approach to sustain the production and input of SCFAs. Therefore, recent research has focused on microbiota transplantation to rebuild the gut microbiome profile in patients with depression.

Faecal microbiota transplantation

FMT is widely used to replenish the gut microbiota in patients with gut dysbiosis by transplanting faecal flora from healthy donors. For depression treatment, FMT yielded a promising prognosis in both preclinical and clinical settings.197 198 For instance, FMT ameliorates chronic unpredictive mild stress-induced depressive symptoms in rats by reshaping the gut microbiota and intestinal barrier and restoring the metabolites of the gut microbiota, which are involved in increased levels of BDNF, the 5-HT transmitter system and GABA pathways in the CNS.199 Several studies have reported the effects of FMT in the treatment of depression in patients. FMT treatment improves anxiety and depressive behaviours in patients with irritable bowel syndrome.200 Oral FMT capsules attenuate depressive symptoms and improve gastrointestinal symptoms and rebalance the gut ecosystem in patients with irritable bowel symptoms.201 In addition, a recent randomised controlled, double-blinded trial verified the feasibility, efficacy and safety of enema-delivered FMT in adults with moderate-to-severe depression.202 Meanwhile, some of the patients showed high accessibility and tolerance to enema delivery despite the potential side effects and complications, suggesting its great therapeutic potential.202

Probiotics and prebiotics

Probiotics, the selected microorganisms that confer health benefits to the host, have been applied in depression treatment, particularly Lactobacillus spp and Bifidobacterium spp, which are involved in SCFAs metabolisms.203 Several clinical trials have demonstrated the efficacy of Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus in depression treatment.204–208 Previous research has also assessed the value of Clostridium butyricum in depression, which participates in the production of SCFAs.209 The C. butyricum (C. butyricum RH2 and C. butyricum miyairi 588) has shown protective effects in mice and rats with stress-induced anxiety-like and depressive-like behaviour.210 211 Other SCFA-producing bacteria, such as F. prausnitzii, have been proven to alleviate depressive-like behaviours in animal models.212 However, the safety and efficacy of these novel probiotics should be further verified in humans. Probiotics therapy exhibited a promising effect in treating perinatal depression. Most patients with postnatal depression are reluctant to receive pharmacological treatment during pregnancy and breast feeding. Therefore, the safe and effective therapy of probiotics, such as Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus, has become a potential approach to preventing and treating perinatal depression.213 214 Nevertheless, it is necessary to alleviate the adverse effects of probiotics when treating clinical depression. The use of SCFA-producing probiotics should be considered carefully due to excessive SCFAs may serve as an additional source of energy substances, which may induce obesity in patients. Several adverse effects and complications, such as infection and gastrointestinal symptoms, have been observed with microbiota transplantation treatments.215 Some determinants like the duration, dosage and interactions in probiotics treatment need to be investigated and standardised in the future. Meanwhile, several studies focus on substrates that are beneficial for restoring the gut microbiota concerning the invasive effect of prebiotics.

Prebiotics, including oligosaccharides (eg, fructooligosaccharides (FOS), galactooligosaccharides (GOS) and inulin) and xylooligosaccharides, are beneficial substrates in human milk, fruits and vegetables.216 Prebiotics are soluble dietary fibres that can produce more SCFAs than insoluble dietary fibres. Prebiotics exert an antidepressant effect and confer host health by promoting gut microbiome profile, especially Bifidobacteria and Lactobacillus.203 Prebiotics also facilitate the growth of other beneficial bacteria, including SCFA-producing bacteria.217 Animal research revealed that the levels of acetate and propionate increased after prebiotic administration.218 Long-term FOS and GOS use also reduces pro-inflammatory cytokine levels and HPA-axis activities and attenuates depressive-like behaviours.218 FOS and GOS feeding in rats increased levels of hippocampal BDNF and N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunit, which are crucial for normal synaptic plasticity and memory formation.219 These findings suggest the feasibility and convenience of using prebiotics for the treatment of depression.

Conclusions and perspective

In the present review, we summarised the vital functions of gut microbiota-derived SCFAs in depression through several pathways, including CCH, neuroinflammation, epigenetic modifications and neuroendocrine functions. The complex, multifaceted and interacting interplay between these alterations in the neural, endocrinal and immune systems elicited by SCFAs plays an essential role in the onset and progression of depression. Although we have preliminarily understood the interactions between microbiota, SCFAs and depression, there are still several problems that obscure the translation from laboratory findings to clinical applications. Indeed, it is difficult to estimate the direct and indirect influence of gut microbial metabolism on the CNS. Owing to the intricate crosstalk concerning the gut microbiota, immunity, endocrine and nervous systems, it is difficult to elaborate on the effects of SCFAs in any single aspect. Meanwhile, a number of studies have investigated alterations in the composition and abundance of gut microbiota in patients with depression, but the alterations exhibit ramified results that puzzle researchers and may lead to undesirable consequences in microbial treatment. Given the complexity of human physiology, several factors, including diet, exercise, ageing and mood, affect the composition and abundance of gut microbiota. With the help of novel methods, such as high-throughput sequencing, multi-omics approaches and microbial culture technology, further research could isolate the pathogenic and harmful strains involved in depression and elaborate the interactions between the microbiota, gut-brain axis and other systems,220 thereby clarifying the pathological mechanism in the microbiota-gut-brain axis and identifying key strains as new therapeutic targets for depression.

Numerous studies have revealed a promising prospect in microbiota-related treatments for depression. SCFA-involved depression treatments, including direct administration of SCFAs, FMT, probiotics and prebiotics have exhibited an antidepressant effect in previous preclinical and clinical studies. Future research should focus on standardising the present microbiota-targeting therapeutic strategies and verifying their safety in different populations. To achieve these goals, a deep understanding of the gut microbiota is needed, concerning the characteristic microbial changes that synchronise with depressive symptoms, the characteristic strains in humans with different traits and the composition and abundance in diverse depression stages (eg, episodes and recurrence). In current clinical studies, the use of gut microbiota and its metabolites is generally standardised for patients with depression. Considering the individual variance of depression, the efficacy and safety of these treatments should be further evaluated. In order to achieve reliable clinical applications, the complexity and individual variance of depression must be thoroughly considered to formulate the standards for microbial intervention. In addition, it would be necessary to identify the impact of SCFA-involved treatments on general antidepressant pharmacotherapy to examine if synergisms generally exist or if the beneficial effects of SCFA-involved treatments depend on specific antidepressants. Factually, there are still several obstructions to translating microbiota-targeted therapeutic designs into clinical treatments. We hope that the biological mechanisms and potential applications related to SCFAs that we summarised could provoke innovations in depression treatment.

Biography

Junzhe Cheng is currently an undergraduate student at the Mental Health Institute of Central South University in China. He is enrolled in the Clinical Medicine Eight-Year Program, Xiangya School of Medicine, Central South University in China. His research interests are mood disorders, including major depressive disorder and anxiety.

Footnotes

JC and HH contributed equally.

Contributors: YZ and BL developed the key concepts and planned the study. JC and HH wrote the original draft, and YZ, BL, YJ, JL and MW participated in the revision. All authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding: This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82001437 and 82371535), STI2030-Major Projects (2021ZD0202000), and the Science and Technology Innovation Program of Hunan Province (2023RC3083).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

References

- 1. de Zwart PL, Jeronimus BF, de Jonge P. Empirical evidence for definitions of episode, remission, recovery, relapse and recurrence in depression: a systematic review. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 2019;28:544–62. 10.1017/S2045796018000227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical Manual of mental disorders. In: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed. Arlington, VA, US: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013. 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization . Depressive disorder (depression). 2021. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression [Accessed 18 Aug 2023].

- 4. Malhi GS, Mann JJ. Depression. Lancet 2018;392:2299–312. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31948-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Baquero F, Nombela C. The microbiome as a human organ. Clin Microbiol Infect 2012;18 Suppl 4:2–4. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03916.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Paone P, Cani PD. Mucus barrier, mucins and gut microbiota: the expected slimy partners? Gut 2020;69:2232–43. 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Weersma RK, Zhernakova A, Fu J. Interaction between drugs and the gut microbiome. Gut 2020;69:1510–9. 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-320204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wang S, Zhang C, Yang J, et al. Sodium butyrate protects the intestinal barrier by modulating intestinal host defense peptide expression and gut microbiota after a challenge with deoxynivalenol in weaned piglets. J Agric Food Chem 2020;68:4515–27. 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c00791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wang H-X, Wang Y-P. Gut microbiota-brain axis. Chinese Medical Journal 2016;129:2373–80. 10.4103/0366-6999.190667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Farzi A, Fröhlich EE, Holzer P. Gut microbiota and the neuroendocrine system. Neurotherapeutics 2018;15:5–22. 10.1007/s13311-017-0600-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Needham BD, Funabashi M, Adame MD, et al. A gut-derived metabolite alters brain activity and anxiety behaviour in mice. Nature 2022;602:647–53. 10.1038/s41586-022-04396-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Li Z, Lai J, Zhang P, et al. Multi-omics analyses of serum metabolome, gut microbiome and brain function reveal dysregulated microbiota-gut-brain axis in bipolar depression. Mol Psychiatry 2022;27:4123–35. 10.1038/s41380-022-01569-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cryan JF, O’Riordan KJ, Cowan CSM, et al. The microbiota-gut-brain axis. Physiol Rev 2019;99:1877–2013. 10.1152/physrev.00018.2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Turna J, Grosman Kaplan K, Anglin R, et al. The gut microbiome and inflammation in obsessive-compulsive disorder patients compared to age- and sex-matched controls: a pilot study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2020;142:337–47. 10.1111/acps.13175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yu Z, Chen W, Zhang L, et al. Gut-derived bacterial LPS attenuates incubation of methamphetamine craving via modulating microglia. Brain Behav Immun 2023;111:101–15. 10.1016/j.bbi.2023.03.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. McGuinness AJ, Davis JA, Dawson SL, et al. A systematic review of gut microbiota composition in observational studies of major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry 2022;27:1920–35. 10.1038/s41380-022-01456-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Modesto Lowe V, Chaplin M, Sgambato D. Major depressive disorder and the gut microbiome: what is the link? Gen Psychiatr 2023;36:e100973. 10.1136/gpsych-2022-100973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Miller TL, Wolin MJ. Pathways of acetate, propionate, and butyrate formation by the human fecal microbial flora. Appl Environ Microbiol 1996;62:1589–92. 10.1128/aem.62.5.1589-1592.1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Le Poul E, Loison C, Struyf S, et al. Functional characterization of human receptors for short chain fatty acids and their role in polymorphonuclear cell activation. J Biol Chem 2003;278:25481–9. 10.1074/jbc.M301403200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kimura I, Ichimura A, Ohue-Kitano R, et al. Free fatty acid receptors in health and disease. Physiol Rev 2020;100:171–210. 10.1152/physrev.00041.2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brown AJ, Goldsworthy SM, Barnes AA, et al. The orphan G protein-coupled receptors GPR41 and GPR43 are activated by propionate and other short chain carboxylic acids. J Biol Chem 2003;278:11312–9. 10.1074/jbc.M211609200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tian D, Xu W, Pan W, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation enhances cell therapy in a rat model of hypoganglionosis by SCFA-induced Mek1/2 signaling pathway. EMBO J 2023;42:e111139. 10.15252/embj.2022111139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Morais LH, Schreiber HL, Mazmanian SK. The gut microbiota-brain axis in behaviour and brain disorders. Nat Rev Microbiol 2021;19:241–55. 10.1038/s41579-020-00460-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Stewart CJ, Ajami NJ, O’Brien JL, et al. Temporal development of the gut microbiome in early childhood from the TEDDY study. Nature 2018;562:583–8. 10.1038/s41586-018-0617-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yu LW, Agirman G, Hsiao EY. The gut microbiome as a regulator of the neuroimmune landscape. Annu Rev Immunol 2022;40:143–67. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-101320-014237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Arumugam M, Raes J, Pelletier E, et al. Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome. Nature 2011;473:174–80. 10.1038/nature09944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Korem T, Zeevi D, Suez J, et al. Growth dynamics of gut microbiota in health and disease inferred from single metagenomic samples. Science 2015;349:1101–6. 10.1126/science.aac4812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yu X, Jiang W, Kosik RO, et al. Gut microbiota changes and its potential relations with thyroid carcinoma. J Adv Res 2022;35:61–70. 10.1016/j.jare.2021.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zmora N, Suez J, Elinav E. You are what you eat: diet, health and the gut microbiota. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;16:35–56. 10.1038/s41575-018-0061-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gao X, Cao Q, Cheng Y, et al. Chronic stress promotes colitis by disturbing the gut microbiota and triggering immune system response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018;115:E2960–9. 10.1073/pnas.1720696115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. O’Toole PW, Jeffery IB. Gut microbiota and aging. Science 2015;350:1214–5. 10.1126/science.aac8469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Reyman M, van Houten MA, Watson RL, et al. Effects of early-life antibiotics on the developing infant gut microbiome and resistome: a randomized trial. Nat Commun 2022;13:893. 10.1038/s41467-022-28525-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zhao Y, Wang C, Goel A. Role of gut microbiota in epigenetic regulation of colorectal cancer. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Reviews on Cancer 2021;1875:188490. 10.1016/j.bbcan.2020.188490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chen C, Liao J, Xia Y, et al. Gut microbiota regulate Alzheimer's disease pathologies and cognitive disorders via PUFA-associated neuroinflammation. Gut 2022;71:2233–52. 10.1136/gutjnl-2021-326269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fan Y, Støving RK, Berreira Ibraim S, et al. The gut microbiota contributes to the pathogenesis of anorexia nervosa in humans and mice. Nat Microbiol 2023;8:787–802. 10.1038/s41564-023-01355-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kosuge A, Kunisawa K, Arai S, et al. Heat-sterilized Bifidobacterium breve prevents depression-like behavior and interleukin-1Β expression in mice exposed to chronic social defeat stress. Brain Behav Immun 2021;96:200–11. 10.1016/j.bbi.2021.05.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Schoeler M, Caesar R. Dietary lipids, gut microbiota and lipid metabolism. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 2019;20:461–72. 10.1007/s11154-019-09512-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fröhlich EE, Farzi A, Mayerhofer R, et al. Cognitive impairment by antibiotic-induced gut dysbiosis: analysis of gut microbiota-brain communication. Brain Behav Immun 2016;56:140–55. 10.1016/j.bbi.2016.02.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schirmer M, Garner A, Vlamakis H, et al. Microbial genes and pathways in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Microbiol 2019;17:497–511. 10.1038/s41579-019-0213-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kilinçarslan S, Evrensel A. The effect of fecal microbiota transplantation on psychiatric symptoms among patients with inflammatory bowel disease: an experimental study. Actas Esp Psiquiatr 2020;48:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lurie I, Yang Y-X, Haynes K, et al. Antibiotic exposure and the risk for depression, anxiety, or psychosis: a nested case-control study. J Clin Psychiatry 2015;76:1522–8. 10.4088/JCP.15m09961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Matta SM, Hill-Yardin EL, Crack PJ. The influence of neuroinflammation in autism spectrum disorder. Brain Behav Immun 2019;79:75–90. 10.1016/j.bbi.2019.04.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lou M, Cao A, Jin C, et al. Deviated and early unsustainable stunted development of gut microbiota in children with autism spectrum disorder. Gut 2022;71:1588–99. 10.1136/gutjnl-2021-325115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zheng P, Zeng B, Liu M, et al. The gut microbiome from patients with schizophrenia modulates the glutamate-glutamine-GABA cycle and schizophrenia-relevant behaviors in mice. Sci Adv 2019;5:eaau8317. 10.1126/sciadv.aau8317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Singh A, Dawson TM, Kulkarni S. Neurodegenerative disorders and gut-brain interactions. J Clin Invest 2021;131:13. 10.1172/JCI143775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zhao N, Chen Q-G, Chen X, et al. Intestinal dysbiosis mediates cognitive impairment via the intestine and brain NLRP3 inflammasome activation in chronic sleep deprivation. Brain Behav Immun 2023;108:98–117. 10.1016/j.bbi.2022.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chen Y, Xu J, Chen Y. Regulation of neurotransmitters by the gut microbiota and effects on cognition in neurological disorders. Nutrients 2021;13:2099. 10.3390/nu13062099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wang Y, Li N, Yang J-J, et al. Probiotics and fructo-oligosaccharide intervention modulate the microbiota-gut brain axis to improve autism spectrum reducing also the hyper-serotonergic state and the dopamine metabolism disorder. Pharmacological Research 2020;157:104784. 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.104784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Liu Y, Xu F, Liu S, et al. Significance of gastrointestinal tract in the therapeutic mechanisms of exercise in depression: synchronism between brain and intestine through GBA. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2020;103:109971. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.109971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zeissig S, Bürgel N, Günzel D, et al. Changes in expression and distribution of claudin 2, 5 and 8 lead to discontinuous tight junctions and barrier dysfunction in active Crohn’s disease. Gut 2007;56:61–72. 10.1136/gut.2006.094375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Shan Y, Lee M, Chang EB. The gut microbiome and inflammatory bowel diseases. Annu Rev Med 2022;73:455–68. 10.1146/annurev-med-042320-021020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Sperner-Unterweger B, Kohl C, Fuchs D. Immune changes and neurotransmitters: possible interactions in depression. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2014;48:268–76. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2012.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Jiang H, Ling Z, Zhang Y, et al. Altered fecal microbiota composition in patients with major depressive disorder. Brain Behav Immun 2015;48:186–94. 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Liu Y, Zhang L, Wang X, et al. Similar fecal microbiota signatures in patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome and patients with depression. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;14:1602–11. 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.05.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Nikolova VL, Smith MRB, Hall LJ, et al. Perturbations in gut microbiota composition in psychiatric disorders: a review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2021;78:1343–54. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.2573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kelly JR, Borre Y, O’ Brien C, et al. Transferring the blues: depression-associated gut microbiota induces neurobehavioural changes in the rat. J Psychiatr Res 2016;82:109–18. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zheng P, Zeng B, Zhou C, et al. Gut microbiome remodeling induces depressive-like behaviors through a pathway mediated by the host’s metabolism. Mol Psychiatry 2016;21:786–96. 10.1038/mp.2016.44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Simpson CA, Diaz-Arteche C, Eliby D, et al. The gut microbiota in anxiety and depression - a systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev 2021;83:101943. 10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Valles-Colomer M, Falony G, Darzi Y, et al. The neuroactive potential of the human gut microbiota in quality of life and depression. Nat Microbiol 2019;4:623–32. 10.1038/s41564-018-0337-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kim C-S, Cha L, Sim M, et al. Probiotic supplementation improves cognitive function and mood with changes in gut microbiota in community-dwelling older adults: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2021;76:32–40. 10.1093/gerona/glaa090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Rudzki L, Ostrowska L, Pawlak D, et al. Probiotic Lactobacillus Plantarum 299V decreases kynurenine concentration and improves cognitive functions in patients with major depression: a double-blind, randomized, placebo controlled study. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2019;100:213–22. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kazemi A, Noorbala AA, Azam K, et al. Effect of probiotic and prebiotic vs placebo on psychological outcomes in patients with major depressive disorder: a randomized clinical trial. Clinical Nutrition 2019;38:522–8. 10.1016/j.clnu.2018.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Cummings JH, Pomare EW, Branch WJ, et al. Short chain fatty acids in human large intestine, portal, hepatic and venous blood. Gut 1987;28:1221–7. 10.1136/gut.28.10.1221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Macfarlane S, Macfarlane GT. Regulation of short-chain fatty acid production. Proc Nutr Soc 2003;62:67–72. 10.1079/PNS2002207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Itoh Y, Kawamata Y, Harada M, et al. Free fatty acids regulate insulin secretion from pancreatic beta cells through GPR40. Nature 2003;422:173–6. 10.1038/nature01478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Trompette A, Gollwitzer ES, Yadava K, et al. Gut microbiota metabolism of dietary fiber influences allergic airway disease and hematopoiesis. Nat Med 2014;20:159–66. 10.1038/nm.3444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Li H-B, Xu M-L, Xu X-D, et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii attenuates CKD via butyrate-renal GPR43 axis. Circ Res 2022;131:e120–34. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.122.320184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Hou Y-F, Shan C, Zhuang S-Y, et al. Gut microbiota-derived propionate mediates the neuroprotective effect of osteocalcin in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Microbiome 2021;9:34. 10.1186/s40168-020-00988-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Vijay N, Morris ME. Role of monocarboxylate transporters in drug delivery to the brain. Curr Pharm Des 2014;20:1487–98. 10.2174/13816128113199990462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Schönfeld P, Wojtczak L. Short- and medium-chain fatty acids in energy metabolism: the cellular perspective. J Lipid Res 2016;57:943–54. 10.1194/jlr.R067629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Doifode T, Giridharan VV, Generoso JS, et al. The impact of the microbiota-gut-brain axis on Alzheimer’s disease pathophysiology. Pharmacol Res 2021;164:105314. 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.105314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Mitchell RW, On NC, Del Bigio MR, et al. Fatty acid transport protein expression in human brain and potential role in fatty acid transport across human brain microvessel endothelial cells. J Neurochem 2011;117:735–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Kekuda R, Manoharan P, Baseler W, et al. Monocarboxylate 4 mediated butyrate transport in a rat intestinal epithelial cell line. Dig Dis Sci 2013;58:660–7. 10.1007/s10620-012-2407-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Fock E, Parnova R. Mechanisms of blood-brain barrier protection by microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids. Cells 2023;12:657. 10.3390/cells12040657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Serger E, Luengo-Gutierrez L, Chadwick JS, et al. The gut metabolite indole-3 propionate promotes nerve regeneration and repair. Nature 2022;607:585–92. 10.1038/s41586-022-04884-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Wu M, Tian T, Mao Q, et al. Associations between disordered gut microbiota and changes of neurotransmitters and short-chain fatty acids in depressed mice. Transl Psychiatry 2020;10:350. 10.1038/s41398-020-01038-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Agus A, Clément K, Sokol H. Gut microbiota-derived metabolites as central regulators in metabolic disorders. Gut 2021;70:1174–82. 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-323071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Awata S, Ito H, Konno M, et al. Regional cerebral blood flow abnormalities in late‐life depression: relation to refractoriness and chronification. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 1998;52:97–105. 10.1111/j.1440-1819.1998.tb00980.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Rajeev V, Fann DY, Dinh QN, et al. Pathophysiology of blood brain barrier dysfunction during chronic cerebral hypoperfusion in vascular cognitive impairment. Theranostics 2022;12:1639–58. 10.7150/thno.68304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Ren C, Liu Y, Stone C, et al. Limb remote ischemic conditioning ameliorates cognitive impairment in rats with chronic cerebral hypoperfusion by regulating glucose transport. Aging Dis 2021;12:1197–210.:1197. 10.14336/AD.2020.1125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Zhang L-Y, Pan J, Mamtilahun M, et al. Microglia exacerbate white matter injury via complement C3/C3aR pathway after hypoperfusion. Theranostics 2020;10:74–90. 10.7150/thno.35841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Lansdell TA, Dorrance AM. Chronic cerebral hypoperfusion in male rats results in sustained HPA activation and hyperinsulinemia. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2022;322:E24–33. 10.1152/ajpendo.00233.2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Farrell JS, Colangeli R, Wolff MD, et al. Postictal hypoperfusion/hypoxia provides the foundation for a unified theory of seizure-induced brain abnormalities and behavioral dysfunction. Epilepsia 2017;58:1493–501. 10.1111/epi.13827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Lan D, Song S, Jia M, et al. Cerebral venous-associated brain damage may lead to anxiety and depression. J Clin Med 2022;11:6927. 10.3390/jcm11236927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Lee SR, Choi B, Paul S, et al. Depressive-like behaviors in a rat model of chronic cerebral hypoperfusion. Transl Stroke Res 2015;6:207–14. 10.1007/s12975-014-0385-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Xiao W, Su J, Gao X, et al. The microbiota-gut-brain axis participates in chronic cerebral hypoperfusion by disrupting the metabolism of short-chain fatty acids. Microbiome 2022;10:62. 10.1186/s40168-022-01255-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Su SH, Chen M, Wu YF, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation and short‐chain fatty acids protected against cognitive dysfunction in a rat model of chronic cerebral hypoperfusion. CNS Neurosci Ther 2023;29:98–114. 10.1111/cns.14089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Su S-H, Wu Y-F, Lin Q, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation and replenishment of short-chain fatty acids protect against chronic cerebral hypoperfusion-induced colonic dysfunction by regulating gut microbiota, differentiation of Th17 cells, and mitochondrial energy metabolism. J Neuroinflammation 2022;19:313. 10.1186/s12974-022-02675-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Raison CL, Capuron L, Miller AH. Cytokines sing the blues: inflammation and the pathogenesis of depression. Trends Immunol 2006;27:24–31. 10.1016/j.it.2005.11.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Köhler CA, Freitas TH, Maes M, et al. Peripheral cytokine and chemokine alterations in depression: a meta-analysis of 82 studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2017;135:373–87. 10.1111/acps.12698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Cui Y, Yang Y, Ni Z, et al. Astroglial Kir4.1 in the lateral habenula drives neuronal bursts in depression. Nature 2018;554:323–7. 10.1038/nature25752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Cervenka I, Agudelo LZ, Ruas JL. Kynurenines: tryptophan’s metabolites in exercise, inflammation, and mental health. Science 2017;357:eaaf9794. 10.1126/science.aaf9794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Leclercq S, Le Roy T, Furgiuele S, et al. Gut microbiota-induced changes in Β-hydroxybutyrate metabolism are linked to altered sociability and depression in alcohol use disorder. Cell Rep 2020;33:108238. 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Li H, Xiang Y, Zhu Z, et al. Rifaximin-mediated gut microbiota regulation modulates the function of microglia and protects against CUMS-induced depression-like behaviors in adolescent rat. J Neuroinflammation 2021;18:254. 10.1186/s12974-021-02303-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Xiao W, Li J, Gao X, et al. Involvement of the gut-brain axis in vascular depression via tryptophan metabolism: a benefit of short chain fatty acids. Exp Neurol 2022;358:114225. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2022.114225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Goldsmith DR, Rapaport MH, Miller BJ. A meta-analysis of blood cytokine network alterations in psychiatric patients: comparisons between schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and depression. Mol Psychiatry 2016;21:1696–709. 10.1038/mp.2016.3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Beurel E, Lowell JA. Th17 cells in depression. Brain Behav Immun 2018;69:28–34. 10.1016/j.bbi.2017.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Peng Z, Peng S, Lin K, et al. Chronic stress-induced depression requires the recruitment of peripheral Th17 cells into the brain. J Neuroinflammation 2022;19:186. 10.1186/s12974-022-02543-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Beurel E, Lowell JA, Jope RS. Distinct characteristics of hippocampal pathogenic TH17 cells in a mouse model of depression. Brain Behav Immun 2018;73:180–91. 10.1016/j.bbi.2018.04.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Kann O, Almouhanna F, Chausse B. Interferon γ: a master cytokine in microglia-mediated neural network dysfunction and neurodegeneration. Trends Neurosci 2022;45:913–27. 10.1016/j.tins.2022.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Wachholz S, Eßlinger M, Plümper J, et al. Microglia activation is associated with IFN-α induced depressive-like behavior. Brain Behav Immun 2016;55:105–13. 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]