Abstract

Objective

To identify and summarise the evidence on the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) RNA detection and persistence in body fluids associated with sexual activity (saliva, semen, vaginal secretion, urine and faeces/rectal secretion).

Eligibility

All studies that reported detection of SARS-CoV-2 in saliva, semen, vaginal secretion, urine and faeces/rectal swabs.

Information sources

The WHO COVID-19 database from inception to 20 April 2022.

Risk of bias assessment

The National Institutes of Health tools.

Synthesis of results

The proportion of patients with positive results for SARS-CoV-2 and the proportion of patients with a viral duration/persistence of at least 14 days in each fluid was calculated using fixed or random effects models.

Included studies

A total of 182 studies with 10 023 participants.

Results

The combined proportion of individuals with detection of SARS-CoV-2 was 82.6% (95% CI: 68.8% to 91.0%) in saliva, 1.6% (95% CI: 0.9% to 2.6%) in semen, 2.7% (95% CI: 1.8% to 4.0%) in vaginal secretion, 3.8% (95% CI: 1.9% to 7.6%) in urine and 31.8% (95% CI: 26.4% to 37.7%) in faeces/rectal swabs. The maximum viral persistence for faeces/rectal secretions was 210 days, followed by semen 121 days, saliva 112 days, urine 77 days and vaginal secretions 13 days. Culturable SARS-CoV-2 was positive for saliva and faeces.

Limitations

Scarcity of longitudinal studies with follow-up until negative results.

Interpretation

SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detected in all fluids associated with sexual activity but was rare in semen and vaginal secretions. Ongoing droplet precautions and awareness of the potential risk of contact with faecal matter/rectal mucosa are needed.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42020204741.

Keywords: COVID-19, Public health, INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Inclusion in the analysis of a large number of patients.

Rigorous methodological approach with comprehensive inclusion criteria that were not limited to studies primarily evaluating SARS-CoV-2 viral shedding/persistence as their main aim, increasing the number of studies in the systematic review and meta-analysis.

This meta-analysis did not consider clinical severity or whether patients were symptomatic during sample collection.

The scarcity of longitudinal cohorts with follow-up until negative results were obtained.

Introduction

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, we have witnessed a complex pattern of fluctuating incidences of SARS-CoV-2.1 These fluctuations occurred both between waves, representing distinct surges of the virus and within a single wave.1 Evidence supports person-to-person transmission of the severe acute respiratory coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) predominantly through close contact with aerosols2 and respiratory droplets3 of an infected individual. SARS-CoV-2 RNA has also been detected in several body fluids, including saliva, semen, vaginal secretion, urine and faeces.4 As SARS-CoV-2 spread is mainly airborne/close contact, other body fluids become less critical during the acute phase of the infection.

Considering the characteristics of the virus, establishing its sexual transmissibility would be a challenging study design. Nonetheless, SARS-CoV-2 RNA was found in the post-acute phase in the faeces of patients whose upper respiratory specimens were already negative.5 6 This raises the concern of possible contagiousness when patients are thought to have cleared the infection through usual methods such as nasal-pharyngeal swab.

Therefore, knowledge about viral persistence and infectivity after recovery from the acute infection in other body fluids is essential to limit infection spread and inform clinical management. Viral RNA detection, however, does not necessarily imply infectivity, which is a precondition for transmissibility, best assessed by viral culture.7

This systematic review was motivated by the need to comprehensively understand the potential for SARS-CoV-2 transmission through various body fluids, particularly in the post-acute phase of infection. This knowledge is crucial for public health, clinical management and the development of targeted prevention strategies, especially in the context of intimate contact.

We aimed to identify and summarise the published evidence on SARS-CoV-2 detection and persistence in body fluids that can be associated with sexual activity (saliva, semen, vaginal secretion, urine and faeces/rectal swabs) with reference to reporting detection methods such as PCR detection of viral RNA and virus isolation.

Methods

Literature search strategy

Electronic searches were run using the WHO COVID-19 database.8 Medical subject headings and keywords for COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2, with viral persistence, and the body fluids (saliva, semen, vaginal secretion, urine and faeces/rectal swab) were used. The search strategy can be found in online supplemental table 1. Searches included the period from the database inception to 20 April 2022. The protocol was published in PROSPERO.

bmjopen-2023-073084supp001.pdf (1.8MB, pdf)

Selection criteria

Following the 2020-updated Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines,9 we conducted a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. PICO (population, intervention, comparison and outcomes) guidelines were used to formulate the research question: ‘In adult individuals diagnosed with COVID-19, what is the proportion of detection and persistence of SARS-CoV-2 in body fluids associated with sexual activity (saliva, semen, vaginal secretions, urine, and fecal matter or rectal mucosa)?’

We included all studies that reported detection of SARS-CoV-2 in saliva, semen, vaginal secretion, urine and faeces/rectal swab, with no restriction of language or country of publication. Results evaluating expressed prostatic secretion were included as semen as this is part of the ejaculate. Studies were considered if they included 10 or more patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection confirmed by real-time reverse transcriptase-PCR (RT-PCR), SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, viral isolation or combined methods.

We excluded studies involving individuals <18 years, to reduce the risk of inclusion bias in studies of the detection and persistence of fluids with different excretion dynamics from adults, such as in the gastrointestinal tract of children and adolescents, where high rates of detection and persistence of SARS-CoV-2 in the faeces has already been demonstrated.10 In cases where adults and participants <18 years were part of the same study, only data from adults were considered for the analysis. When this was not possible to be distinguished, the study was excluded. Studies with animals or in vitro, autopsies, conference papers, abstracts and lack of primary data were excluded (online supplemental figure 1).

Study screening and review

The sources identified through the search strategy performed by EK and LG were uploaded in an EndNote Reference Manager, followed by deduplication. The resulting papers were then exported to the Rayyan web application for systematic reviews,11 where a second deduplication was conducted. Finally, before the full-text review was performed, manual deduplication was completed to identify preprint manuscripts with titles and authors slightly different from their final published peer-reviewed versions. The authors (EK, LG, GC and PMQG) independently performed title and abstract screening. Disagreement on selection was discussed and resolved by consensus.

Data extraction

Data were extracted using Microsoft Excel spreadsheets (online supplemental table 2). A table containing the final list was then circulated to the reviewers for full-text assessment (online supplemental tables 3–9).

The acute and convalescent/recovery phases of COVID-19 disease were defined as the presence of symptoms up to and after 14 days from symptom onset, respectively. We adopted 14 days based on the initial guidance provided by WHO to release patients from isolation.12 The maximum persistence in days was recorded in each study. The duration of the viral persistence was calculated using the period between symptom onset and the last positive RT-PCR preceding the first negative RT-PCR result. For asymptomatic cases, the date of the first positive test result was considered.

Quality assessment

Validated checklists tailored for specific types of study published by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute13 were used to assess the methods’ quality (online supplemental tables 10–12). Risk of bias assessment tool for each study design was used.

Statistical analysis

The two principal summary measures were detection and persistence of SARS-CoV-2 calculated as the proportion of patients with positive results for RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2, and the proportion of patients with a viral duration/persistence of at least 14 days, in each of the studied fluids. We performed the meta-analyses by computing the above two proportions using fixed or random-effects models based on the degree of heterogeneity.

The test for heterogeneity was used to assess whether the difference between studies was due to random variability or should be interpreted with caution when statistically significant (p<0.05). We calculated the Tau2 and I2 statistics to measure the proportion attributed to heterogeneity and considered low, moderate and high heterogeneity in the I2 values of <25%, 25%–75% and >75%, respectively. The results are presented for each body fluid. We interpreted the common effect according to heterogeneity’s presence (random effect) or absence (fixed effect). We used the logit transformation of proportions to calculate the overall proportion.

To avoid problems when computing the variance, a value of 0.5 was added to the numerator and denominator of the study’s proportion when the numerator of a proportion was zero. We showed the results in the forest plots where proportionally sized boxes represent the weight of each study, and a diamond shows the overall effect at the bottom of the plot. The meta and metafor packages of R were used for the meta-analyses.14 Survival-related summary measures (hazard rates) were not used due to the relatively high number of censored data in each of the studies. We used a narrative descriptive approach to summarise the evidence for viral culture results for each selected body fluid.

Patient and public involvement

There was no patient or public involvement in this systematic review.

Results

The search resulted in 19 383 citations, of which 17 865 were eligible for title and abstract screening after duplicated articles exclusion. Of these, 1312 were retained for full-text screening of which 182 were included (online supplemental table 13). Reasons for study exclusions were: diagnostic accuracy (n=404), no sample of interest (n=301), no feasible separation of adults/children (n=123), correspondence, editorial, review, letter to editor commenting on another article, technical report or protocol (n=99), case report/case series <10 patients (n=47), RT-PCR results by fluid not presented (n=44), abstract/poster (n=43), text in Chinese, with no full text available (n=19), partial/same population of another article (n=16), surveillance/detection of RT-PCR in fluids without persistence details (n=12), strategies to decrease saliva infectivity (n=9), only autopsy studies (n=7) and duplicate articles (n=6).

Among the included studies 101 (55.5%) were prospective cohorts, 29 (15.9%) retrospective cohorts, 27 (14.8%) cross-sectionals, 21 (11.5%) case series, 3 (1.6%) ambispective cohorts and 1 (0.5%) case–control study (online supplemental table 3).

Global distribution of studies

Most studies were from China (n=72), followed by the USA (n=15), Turkey (n=13), Italy (n=11), India (n=9), Japan (n=7), Iran (n=6), Germany, Republic of Korea and Singapore (n=5 each), Belgium (n=4), Brazil, Denmark and France (n=3 each), Canada, Indonesia, Israel, UK (n=2 each), Argentina, Australia, Austria, Chile, Colombia, Czech Republic, Iraq, Romania, Russia, South Africa, Spain, Sweden and Switzerland (n=1 each) (online supplemental table 3).

Patient characteristics

The studies included 10 023 patients with recruitment ranging from 10 to 564 cases. Where data were available, the cohorts comprised 52.1% male (n=4962 of 9519) patients with ages ranging from 18 to 106 years. The phase of infection was reported by 86.3% of the studies (n=157), comprising the acute phase (n=3814 participants), the recovery phase (n=948 participants) and both phases (n=2760 participants). Only 13.7% of the studies (n=25) followed patients until negative results were obtained for the body fluids of interest (online supplemental tables 5–9).

Detection and persistence of SARS-CoV-2 in body fluids

Thirty-eight studies presented results from saliva, 30 from semen, 31 from vaginal secretions, 42 from urine and 91 from rectal samples. Online supplemental figure 2 depicts the median and range of detectable RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2 in all fluids with available information.

Saliva

Thirty-eight studies (27 cohorts, 9 cross-sectional and 2 case series) assessed saliva samples from 1838 patients (3898 specimens) but only 5 followed patients until negative results were yielded (n=195 patients). Saliva-positive samples (n=1339) were reported by 38 studies (1091 patients) of which 22 reported the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in saliva for at least 14 days (n=71 patients). SARS-CoV-2 was detected up to 112 days after symptoms onset.

Virus isolation was attempted by nine studies15–23 and viral cultures were successfully performed in six,17–19 21–23 although the presence of typical cytopathic effect and or increased viral in the supernatant was reported in only four of them,17–19 22 with one of the studies showing that most patients shed live virus for ≥20 days.19

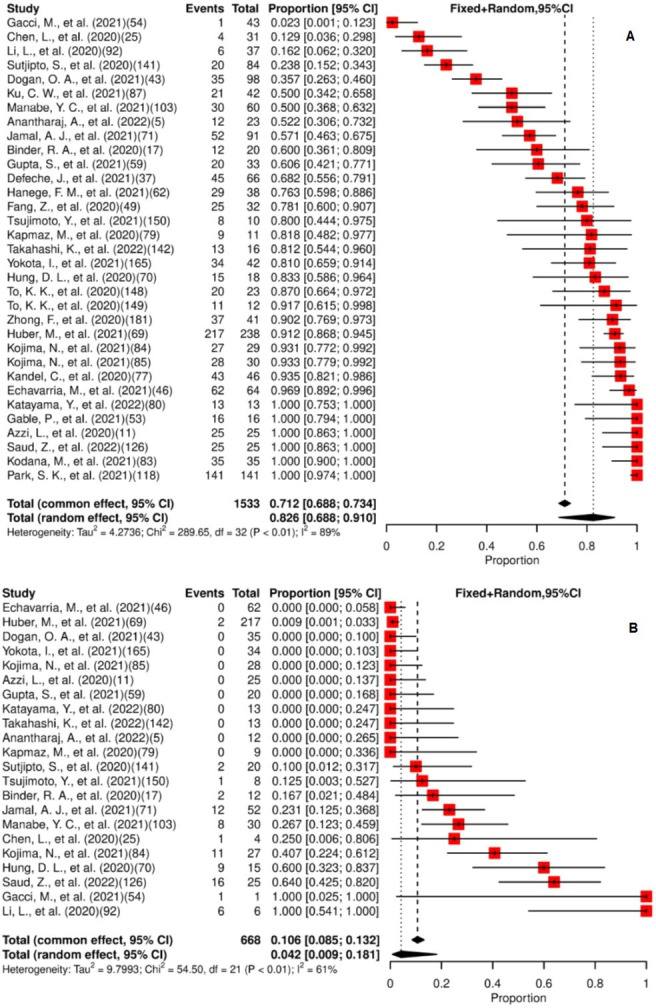

For the meta-analysis, 33 studies were included. Of the total patients (n=1533) providing saliva specimens, 82.6% (95% CI: 68.8% to 91.0% and 4.2% (95% CI: 0.9% to 18.1%) had viral detection and persistence for at least 14 days, respectively. These are separately represented in figure 1A,B. High and moderate heterogeneity were observed in studies assessing presence and persistence, respectively. The median of the maximum reported persistence was 20 days (IQR: 11.5–45, range 2–112).

Figure 1.

(A) Forest plot for meta-analysis of the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in saliva. (B) Forest plot for meta-analysis of persistence of SARS-CoV-2 in saliva for ≥14 days. The numbers in parentheses represent the article publication year and the reference listed in the online supplemental material.

Semen

The presence of SARS-CoV-2 in semen was assessed by 30 studies (16 cohort, 8 cross-sectional and 6 case series), including 888 patients (1428 specimens). Six studies reported the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in semen (n=14 patients),24–29 but only one followed patients until a negative result was obtained.25

The samples of 11 patients with SARS-CoV-2 detection in semen were collected within 2 weeks of symptom onset, while for 3 patients the collection was conducted during the recovery phase of the disease. Two studies that attempted to culture the virus did not recover the viable virus.27 30

Of the six studies reporting viral detection, two did not report the detection duration but informed that the specimens were collected within 2 weeks following symptom onset.25 29 The remaining four studies reported SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR detection for 6, 16, 58 and 121 days.24 26–28

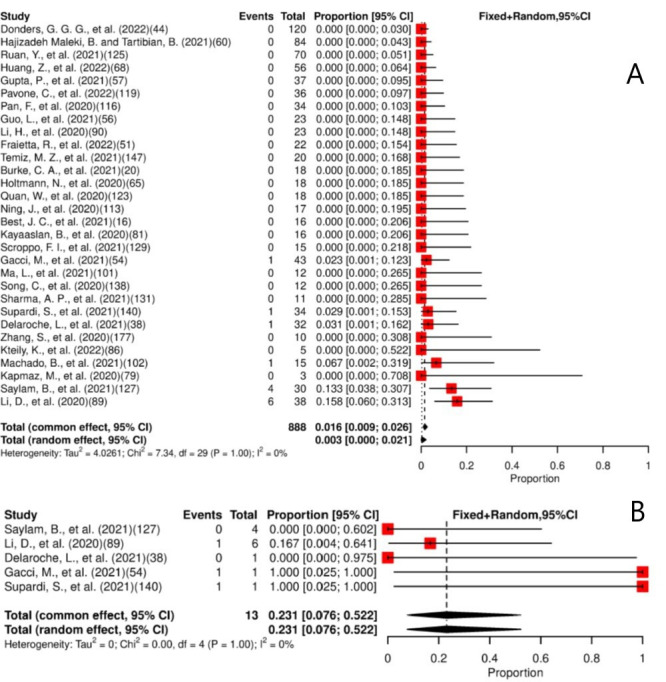

The meta-analysis of the 30 studies estimated that 1.6% (95% CI: 0.9% to 2.6%) of patients had SARS-CoV-2 detected in their semen specimens, as shown in figure 2A. Viral persistence for at least 14 days was found in 23.1% (95% CI: 7.6% to 52.2%) of the five studies included in the meta-analysis (figure 2B). Low heterogeneity for presence and persistence was observed. The median of the maximum persistence values was 37 days (IQR: 8.5–105.3, range 6–121).

Figure 2.

(A) Forest plot for meta-analysis of the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in semen. (B) Forest plot for meta-analysis of persistence of SARS-CoV-2 in semen for ≥14 days. The numbers in parentheses represent the article publication year and the reference listed in the online supplemental material.

Vaginal secretions

Thirty-one studies (20 cohort, 6 cross-sectional and 5 case series) assessed the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in vaginal secretion of 859 patients (875 specimens). Eight studies reported SARS-CoV-2 detection in 23 patients.31–38 Information on viral persistence was reported by only two studies (8 and 13 days).35 36 The remaining six studies evaluated viral persistence only during the acute phase of the disease; hence no reports at or after 14 days of COVID-19 diagnosis were provided. None of the included studies followed patients with positive vaginal specimens until negativisation.

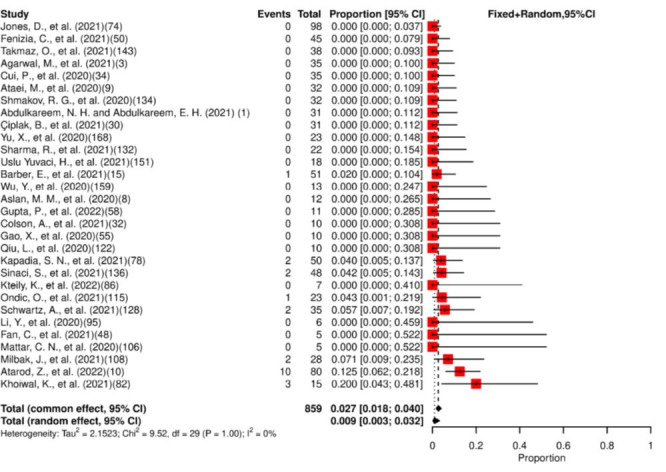

Thirty studies were included in the meta-analysis, which estimated that 2.7% (95% CI: 1.8% to 4.0%) of patients had SARS-CoV-2 detected in their vaginal secretions (figure 3). Low heterogeneity for presence was observed. No study reported viral persistence for at least 14 days. The mean of the maximum reported viral persistence was 10.5 days (SD: 3.54, range 8–13).

Figure 3.

Forest plot for meta-analysis of the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in vaginal secretions. The numbers in parentheses represent the article publication year and the reference listed in the online supplemental material.

Urine

Urine samples from 1801 patients (1904 specimens) were assessed by 42 studies (36 cohorts, 5 case series and 1 cross-sectional study). Positive specimens were detected in 141 patients from 26 studies. Six studies reported the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in urine (n=22 patients) for at least 14 days.28 39–43 Eleven studies followed patients until negative results (n=497 patients).6 25 42 44–51 SARS-CoV-2 was detected up to 77 days after symptoms onset.28

Three studies attempted viral isolation in Vero cells.15 52 53 Two urine sediment specimens generated cytopathic growth in the study by Caceres et al; however, subsequent RT-PCR failed to amplify any SARS-CoV-2 genetic material isolated from the culture cells.53 Kapmaz et al 15 and Young et al 52 were unable to isolate the virus.

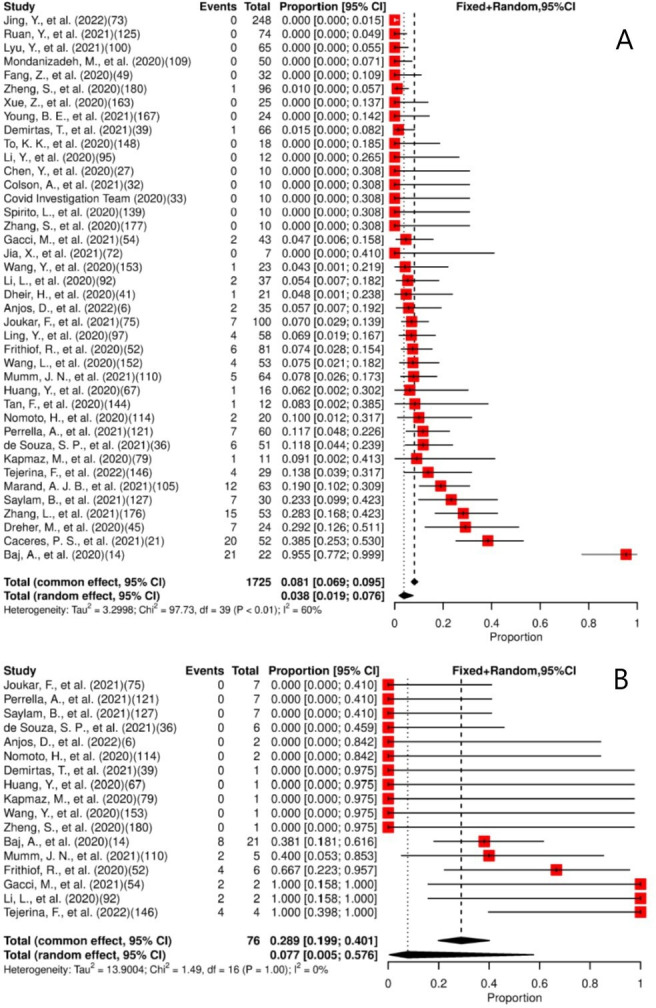

Forty studies were included in the meta-analysis. Of the total patients (n=1725) providing urine specimens, 3.8% (95% CI: 1.9% to 7.6%) had positive results. A moderate heterogeneity for the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in the urine among the studies was observed (figure 4A).

Figure 4.

(A) Forest plot for meta-analysis of the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in urine. (B) Forest plot for meta-analysis of persistence of SARS-CoV-2 in urine for ≥14 days. The numbers in parentheses represent the article publication year and the reference listed in the online supplemental material.

Viral persistence for at least 14 days was found in 29% (95% CI: 19.9% to 40.1%) of the 17 studies included in the meta-analysis. A low heterogeneity for the persistence of SARS-CoV-2 in the urine among the studies was observed (figure 4B). The median of the maximum reported persistence was 11 days (IQR: 9–35, range 7–77).

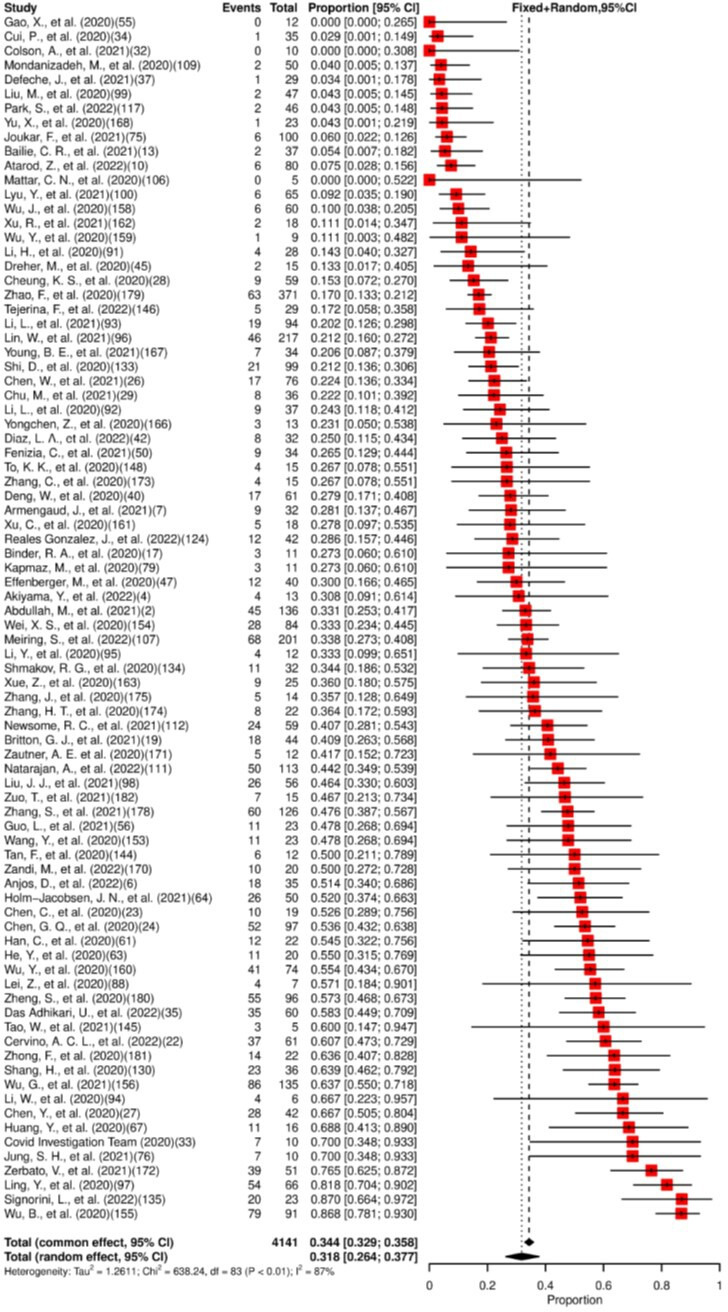

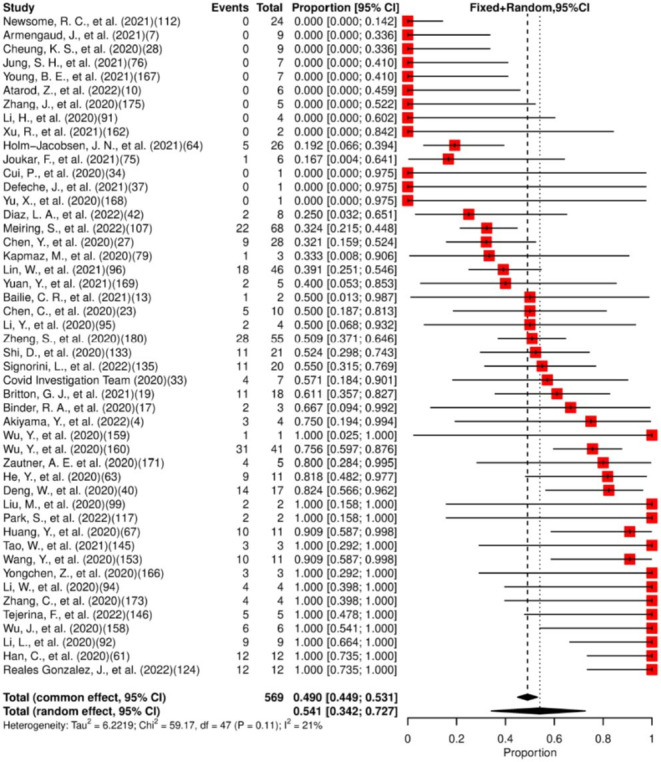

Faeces/rectal specimens

Half of the studies (n=91) included in this review assessed the presence and persistence of SARS-CoV-2 in faeces or rectal swabs (76 cohorts, 10 case series, 4 cross-sectional and 1 case–control).

The studies included 4386 patients (6773 specimens). Eighty-seven studies reported RT-PCR detection (1436 patients). Of these, 37 studies (282 patients) detected SARS-CoV-2 for more than 14 days, with maximum detection at 210 days.54 In total, 19 studies followed-up 831 patients (2466 specimens) until negative results were obtained.5 6 44–47 49–51 54–63

Viral isolation was attempted by seven studies,15 16 52 64–67 but only one achieved its goal by isolating viral particles from Vero E6 epithelial cell monolayers inoculated with stool specimens of 6.25% (7/112) patients without specifying the time elapsed between the symptoms onset and isolation.67

We included in the meta-analysis 84 studies. Of the patients included (n=4141), 31.8% (95% CI: 26.4% to 37.7%) had SARS-CoV-2 detected in their faeces/rectal swab specimens, as shown in figure 5. Viral persistence for at least 14 days was found in 49% (95% CI: 44.9% to 53.1%) of the 48 studies included in the meta-analysis (figure 6). High heterogeneity for presence and low heterogeneity for persistence were observed. The median of the maximum reported persistence values was 32 days (IQR 20–43.3; range 7–210).

Figure 5.

Forest plot for meta-analysis of the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in faeces/rectal swab. The numbers in parentheses represent the article publication year and the reference listed in the online supplemental material.

Figure 6.

Forest plot for meta-analysis of persistence of SARS-CoV-2 in faeces/rectal swab for ≥14 days. The numbers in parentheses represent the article publication year and the reference listed in the online supplemental material.

Risk of bias and quality assessment

Through the National Institutes of Health (NIH) tools, 170 studies were scored as good and 12 were assessed as fair. No studies were excluded from the meta-analysis due to low quality (online supplemental tables 10–12).

Discussion

In this review of 182 articles and meta-analysis of 10 023 patients from 31 countries, we summarise findings from studies reporting SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection and persistence in body fluids involved in sexual activity, namely saliva, semen, vaginal secretion, urine and faeces/rectal mucosa. Viable viruses from these body fluids could contribute to transmission during sexual or intimate contact.

This review revealed that SARS-CoV-2 RNA had been detected most often in saliva (83%), followed by faeces/rectal swabs (32%) and rarely in urine (3.8%), vaginal secretion (2.7%) and semen (1.6%). Viral persistence for at least 14 days was longest in faeces/rectal swabs (49%), followed by urine (29%), semen (23%) and saliva (4.2%). SARS-CoV-2 RNA was not detected for ≥14 days in vaginal secretions. As a surrogate marker for infectivity, viral isolation through culture was achieved only in saliva and stool samples.

Exposure to saliva occurs in many sexual activities involving oral, vaginal, penile and anal contact. The presence and persistence of the virus in this fluid should be considered when recommendations are made to reduce the spread of the infection. Some studies reported detectable SARS-CoV-2 RNA in saliva for more than 14 days after symptoms onset. However, a recent meta-analysis showed that infectious potential declined after 9 days, even among patients with high viral loads in a respiratory specimen inferred from cycle threshold values.68 69 In the present systematic review, virus isolation in saliva was attempted by nine studies,15–23 but the presence of a typical cytopathic effect and detectable viral particles in the supernatant was reported by only four studies.17–19 22

As SARS-CoV-2 can be potentially transmitted through saliva exchange or when used as a lubricant, the use of masks and sexual protection such as condoms and dental dams could be appropriate interventions to prevent transmission. However, it remains challenging to differentiate between transmission through saliva and respiratory droplets (talking, coughing, sneezing, kissing) during sexual activity.

Stool samples or rectal swabs were examined in half of the studies of this review, yielding detection in almost one-third of the patients. Viral persistence for at least 14 days was found in 49% of the 48 studies included in the meta-analysis. Several studies showed that the stool/rectal swabs remained positive after upper respiratory swabs returned negative results. Natarajan et al showed the presence of viral RNA in the faeces at late time points (up to 210 days), but reinfection could not be ruled out.54 The presence of SARS-CoV-2 in rectal/faecal specimens following the acute phase of the disease has implications for specific sexual activities such as anilingus (oral-anal contact) and insertive anal sex. The virus has been successfully cultured in faeces,67 and additional studies are necessary to further the knowledge of the magnitude and importance of these findings and their contribution as a potential transmission route.

SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detected in the urine of 3.8% of 1725 providing urine specimens in the 40 studies included in the meta-analysis, and viral persistence for at least 14 days was found in 29% of the 17 studies included. However, the observational studies analysed differed in sampling techniques, phase and disease severity, which may be associated with the high and significant heterogeneity observed in the meta-analysis. Selected case reports, not included in this systematic review,70 71 describe the successful isolation of infectious SARS-CoV-2 from the urine of patients with COVID-19. However, further studies of culture and virulence are needed, and it appears to be highly unlikely that urine is a relevant risk for transmission in patients. Depending on the sexual practices of individuals and the evidence that SARS-CoV-2 has been detected in the urine, safety and hygiene measurements should be taken into consideration.

SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection in vaginal secretions was also extremely low (2.7%), and viral persistence for at least 14 days has not been reported. All positive specimens, however, were reported during the acute phase of the disease. None of these studies followed-up with the patients until negative results were obtained, which raises the point of whether longer persistence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in vaginal specimens could have been identified if additional time points were added. A case report by Colavita et al reported a woman with SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection in cervicovaginal swabs for up to 20 days,72 reinforcing the necessity of more longitudinal studies with multiple sample collections over time.

The detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in semen was extremely low (1.6%) and almost 80% (11/14) of the samples were collected within 2 weeks of the COVID-19 diagnosis. Although viral persistence for at least 14 days was found in 23.1% of the patients, only one study had a follow-up period until it became negative.25 Therefore, this result should be taken with caution, as it may underestimate the potential real persistence value and calls for longitudinal studies with longer follow-ups to better understand SARS-CoV-2 persistence in this fluid.

A viable virus has not been cultured in the semen of patients infected with SARS-CoV-2.27 30 This meta-analysis suggests that sexual transmission of SARS-CoV-2 through semen is unlikely. However, several studies have shown that COVID-19 may cause testicular spermatogenesis dysfunction via immune or inflammatory reactions. Long-term follow-up is needed to also better understand the infection’s impact on the male reproductive system.73

Our study has some limitations. High heterogeneity among studies assessing SARS-CoV-2 presence in saliva and faeces/rectal swabs was observed. It might be attributed to the study design variation, sample size and characteristics. In addition, the scarcity of longitudinal studies with follow-up until negative results were obtained and no consistent time points for sample collection were also limitations.

This meta-analysis did not consider clinical severity or whether patients were symptomatic during sample collection. Additional cohort studies, including a range of disease severities and comorbidities, could identify associations between severity, viral presence and persistence. The lack of or paucity of successful viral cultures leaves the question of infectivity unanswered. Specifically, culture studies in this analysis did not successfully demonstrate the presence of viable virus in the evaluated fluids nor the possibility, probability or frequency of genital-to-genital transmission of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with respiratory transmission occurring as part of intimate sexual contact. Finally, viral persistence about other co-occurring sexually transmitted infections was not ascertained.

Strengths of our study include analysis of a large number of patients, a rigorous methodological approach with a comprehensive inclusion criterion that was not limited to studies primarily evaluating SARS-CoV-2 viral shedding/persistence as their main aim increasing the number of studies in the systematic review and meta-analysis.

Our findings emphasise the importance of maintaining preventive measures, which applies to future outbreaks. Furthermore, for effective public health strategies, the study underscores the importance of monitoring viral persistence and viral infectivity studies, especially in body fluids associated with sexual activity. Lastly, the study highlights the critical importance of maintaining awareness about possible alternative transmissions beyond the respiratory route.

Conclusions

This systematic review showed that SARS-CoV-2 detected by RT-PCR was present and persistent in body fluids involved in sexual activity, with reports suggesting the persistence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA beyond the symptomatic phase. However, additional longitudinal cohort studies, with viral cultures, infectivity evaluations, inclusion of disease severity and comorbidities are needed to better understand if sexual contact contributes to transmission of this new pathogen beyond that of respiratory exposure.

Although the viable virus has not been found in semen and was not attempted in vaginal secretions, studies have shown the plausibility of transmission through sexual activities, including saliva and anal contact. Therefore, caution related to contact with saliva and faecal matter/rectal mucosa is necessary. Early detection, contact tracing, isolation and provision of public information on safe sex practices, highlighting a possible period of infectiousness, are crucial to preventing spread, especially after the acute phase of the disease is finished.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @liannegonsalves, @CaronRKim

GAC and EK contributed equally.

Contributors: EK, LG and NB conceptualised and designed the study. GAC, EK, LG, RGPdL, MCG, GMP, BVRP, MGA, GOC, DCC, PMQG and MA were involved in the screening of articles, assessment of the risk of bias and data extraction. GAC, EK, LG, AHS, RdVCdO and SST contributed to the methodology. Software, data analysis and interpretation were done by GAC, EK, AHS and RdVCdO. Project administration was done by EK and LG. Guarantor is GAC. The original draft was done by GAC and EK. LG, AHS, RdVCdO, SST, RGPdL, MCG, GMP, BVRP, MGA, GOC, DCC, PMQG, MB, MT, AT, CK, MA and NB provided critical comments and edited the final draft.

Funding: This work was supported by the Department of Sexual and Reproductive Health and Research (WHO) without a specific grant number.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

References

- 1. World Health Organization . Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. n.d. Available: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019

- 2. Wang CC, Prather KA, Sznitman J, et al. Airborne transmission of respiratory viruses. Science 2021;373:eabd9149. 10.1126/science.abd9149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhou L, Ayeh SK, Chidambaram V, et al. Modes of transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and evidence for preventive behavioral interventions. BMC Infect Dis 2021;21:496. 10.1186/s12879-021-06222-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mishra C, Meena S, Meena JK, et al. Detection of three pandemic causing Coronaviruses from non-respiratory samples: systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 2021;11:16131. 10.1038/s41598-021-95329-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wu Y, Guo C, Tang L, et al. Prolonged presence of SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA in Faecal samples. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;5:434–5. 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30083-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zheng S, Fan J, Yu F, et al. Viral load dynamics and disease severity in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Zhejiang province, China, January-March 2020: retrospective cohort study. BMJ 2020;369:m1443. 10.1136/bmj.m1443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fomenko A, Weibel S, Moezi H, et al. Assessing severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus 2 infectivity by reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Med Virol 2022;32:e2342. 10.1002/rmv.2342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. World Health Organization . Global research on Coronavirus disease (COVID-19). n.d. Available: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/global-research-on-novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov

- 9. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wang JG, Cui HR, Tang HB, et al. Gastrointestinal symptoms and fecal nucleic acid testing of children with 2019 Coronavirus disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 2020;10:17846. 10.1038/s41598-020-74913-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, et al. Rayyan-a web and mobile App for systematic reviews. Syst Rev 2016;5:210. 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. World Health Organization, Scientific brief . Criteria for releasing COVID-19 patients from isolation. n.d. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/commentaries/detail/criteria-for-releasing-covid-19-patients-from-isolation

- 13. National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute . Study quality assessment tools. n.d. Available: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools

- 14. Viechtbauer W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the Metafor package. J Stat Softw 2010;36:1–48. 10.18637/jss.v036.i03 Available: https://www.jstatsoft.org/v36/i03/ [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dogan Ö, Aktürk H, Özer B, et al. Infectivity of adult and pediatric COVID-19 patients. Infect Dis Clin Microbiol 2021;3:78–86. 10.36519/idcm.2021.61 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Binder RA, Alarja NA, Robie ER, et al. Environmental and aerosolized severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus 2 among hospitalized Coronavirus disease 2019 patients. J Infect Dis 2020;222:1798–806. 10.1093/infdis/jiaa575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bae S, Kim JY, Lim SY, et al. Dynamics of viral shedding and symptoms in patients with asymptomatic or mild COVID-19. Viruses 2021;13:2133. 10.3390/v13112133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Park S, Lim SY, Kim JY, et al. Clinical and virological characteristics of severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-Cov-2) B.1.617.2 (Delta) variant: a prospective cohort study. Clin Infect Dis 2022;75:e27–34. 10.1093/cid/ciac239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Saud Z, Ponsford M, Bentley K, et al. Mechanically ventilated patients shed high-titer live severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) for extended periods from both the upper and lower respiratory tract. Clin Infect Dis 2022;75:e82–8. 10.1093/cid/ciac170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sohn Y, Jeong SJ, Chung WS, et al. Assessing viral shedding and infectivity of asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic patients with COVID-19 in a later phase. J Clin Med 2020;9:2924. 10.3390/jcm9092924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Takahashi K, Ishikane M, Ujiie M, et al. Duration of infectious virus shedding by SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant-infected Vaccinees. Emerg Infect Dis 2022;28:998–1001. 10.3201/eid2805.220197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kojima N, Mores C, Farsai N, et al. Duration of SARS-CoV-2 viral culture positivity among different specimen types. Clin Microbiol Infect 2021;27:1540–1. 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.07.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. To KK-W, Tsang OT-Y, Yip CC-Y, et al. Consistent detection of 2019 novel Coronavirus in saliva. Clin Infect Dis 2020;71:841–3. 10.1093/cid/ciaa149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Li D, Jin M, Bao P, et al. Clinical characteristics and results of semen tests among men with Coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e208292. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.8292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Saylam B, Uguz M, Yarpuzlu M, et al. The presence of SARS-CoV-2 virus in semen samples of patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. Andrologia 2021;53:e14145. 10.1111/and.14145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Supardi S, Nidom RV, Sisca EM, et al. Novel investigation of SARS-CoV-2 in COVID-19 survivors’ semen in Surabaya, Indonesia. Sexual and Reproductive Health 2021. 10.1101/2021.10.08.21264593 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Delaroche L, Bertine M, Oger P, et al. Evaluation of SARS-CoV-2 in semen, seminal plasma, and Spermatozoa pellet of COVID-19 patients in the acute stage of infection. PLoS One 2021;16:e0260187. 10.1371/journal.pone.0260187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gacci M, Coppi M, Baldi E, et al. Semen impairment and occurrence of SARS-CoV-2 virus in semen after recovery from COVID-19. Hum Reprod 2021;36:1520–9. 10.1093/humrep/deab026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Machado B, Barcelos Barra G, Scherzer N, et al. Presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in semen-cohort study in the United States COVID-19 positive patients. Infect Dis Rep 2021;13:96–101. 10.3390/idr13010012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fraietta R, de Carvalho RC, Camillo J, et al. SARS-CoV-2 is not found in human semen during mild COVID-19 acute stage. Andrologia 2022;54:e14286. 10.1111/and.14286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Atarod Z, Zamaniyan M, Moosazadeh M, et al. Investigation of vaginal and rectal swabs of women infected with COVID-19 in two hospitals covered by. J Obstet Gynaecol 2022;42:2225–9. 10.1080/01443615.2022.2036966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Khoiwal K, Kalita D, Shankar R, et al. Identification of SARS-CoV-2 in the vaginal fluid and cervical exfoliated cells of women with active COVID-19 infection: a pilot study. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2021;153:551–3. 10.1002/ijgo.13671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kapadia SN, Mehta A, Mehta CR, et al. Study of pregnancy with COVID-19 and its clinical outcomes in a tertiary care teaching hospital in Western India. J South Asian Fed Obstet Gynecol 2021;13:125–30. 10.5005/jp-journals-10006-1886 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sinaci S, Ocal DF, Seven B, et al. Vertical transmission of SARS-CoV-2: a prospective cross-sectional study from a tertiary center. J Med Virol 2021;93:5864–72. 10.1002/jmv.27128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Milbak J, Holten VMF, Axelsson PB, et al. A prospective cohort study of confirmed severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-Cov-2) infection during pregnancy evaluating SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in maternal and umbilical cord blood and SARS-CoV-2 in vaginal Swabs. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2021;100:2268–77. 10.1111/aogs.14274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Schwartz A, Yogev Y, Zilberman A, et al. Detection of severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in vaginal Swabs of women with acute SARS-CoV-2 infection: a prospective study. BJOG 2021;128:97–100. 10.1111/1471-0528.16556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Barber E, Kovo M, Leytes S, et al. Evaluation of SARS-CoV-2 in the vaginal secretions of women with COVID-19: A prospective study. J Clin Med 2021;10:2735. 10.3390/jcm10122735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ondič O, Černá K, Kinkorová-Luňáčková I, et al. SARS-CoV-2 RNA may rarely be present in a uterine cervix LBC sample at the asymptomatic early stage of COVID 19 disease. Cytopathology 2021;32:766–70. 10.1111/cyt.12995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Baj A, Azzi L, Dalla Gasperina D, et al. Pilot study: long-term shedding of SARS-Cov-2 in urine: a threat for dispersal in wastewater. Front Public Health 2020;8:569209. 10.3389/fpubh.2020.569209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Frithiof R, Bergqvist A, Järhult JD, et al. Presence of SARS-CoV-2 in urine is rare and not associated with acute kidney injury in critically ill COVID-19 patients. Crit Care 2020;24:587. 10.1186/s13054-020-03302-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tejerina F, Catalan P, Rodriguez-Grande C, et al. Post-COVID-19 syndrome. SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection in plasma, stool, and urine in patients with persistent symptoms after COVID-19. BMC Infect Dis 2022;22:211. 10.1186/s12879-022-07153-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mumm J-N, Ledderose S, Ostermann A, et al. Dynamics of urinary and respiratory shedding of severe acute respiratory syndrome virus 2 (SARS-Cov-2) RNA excludes urine as a relevant source of viral transmission. Infection 2022;50:635–42. 10.1007/s15010-021-01724-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Li L, Tan C, Zeng J, et al. Analysis of viral load in different specimen types and serum antibody levels of COVID-19 patients. J Transl Med 2021;19:30. 10.1186/s12967-020-02693-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Joukar F, Yaghubi Kalurazi T, Khoshsorour M, et al. Persistence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the Nasopharyngeal, blood, urine, and stool samples of patients with COVID-19: a hospital-based longitudinal study. Virol J 2021;18:134. 10.1186/s12985-021-01599-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Huang Y, Chen S, Yang Z, et al. SARS-CoV-2 viral load in clinical samples from critically ill patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2020;201:1435–8. 10.1164/rccm.202003-0572LE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wang Y, Zhang L, Sang L, et al. Kinetics of viral load and antibody response in relation to COVID-19 severity. J Clin Invest 2020;130:5235–44. 10.1172/JCI138759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Li Y, Hu Y, Yu Y, et al. Positive result of Sars-Cov-2 in Faeces and Sputum from discharged patients with COVID-19 in Yiwu, China. J Med Virol 2020;92:1938–47. 10.1002/jmv.25905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Fang Z, Zhang Y, Hang C, et al. Comparisons of viral shedding time of SARS-CoV-2 of different samples in ICU and non-ICU patients. J Infect 2020;81:147–78. 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Jia X, Shao S, Ren H, et al. Sinonasal manifestations and dynamic profile of RT-PCR results for SARS-CoV-2 in COVID-19 patients. Ann Palliat Med 2021;10:4174–83. 10.21037/apm-20-2493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Xue Z, You H, Luan Y, et al. Detection of 2019-nCoV nucleic acid in different specimens from confirmed COVID-19 cases during hospitalization and after discharge. Chinese Journal of Microbiology and Immunology (China) 2020;40:569–73. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tan F, Wang K, Liu J, et al. Viral transmission and clinical features in asymptomatic carriers of SARS-CoV-2 in Wuhan. Front Med (Lausanne) 2020;7:547. 10.3389/fmed.2020.00547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Young BE, Ong SWX, Ng LFP, et al. Viral dynamics and immune correlates of Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) severity. Clin Infect Dis 2021;73:e2932–42. 10.1093/cid/ciaa1280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Caceres PS, Savickas G, Murray SL, et al. High SARS-CoV-2 viral load in urine sediment correlates with acute kidney injury and poor COVID-19 outcome. J Am Soc Nephrol 2021;32:2517–28. 10.1681/ASN.2021010059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Natarajan A, Zlitni S, Brooks EF, et al. Gastrointestinal symptoms and fecal shedding of SARS-CoV-2 RNA suggest prolonged gastrointestinal infection. Med 2022;3:371–387. 10.1016/j.medj.2022.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Chen G-Q, Luo W-T, Zhao C-H, et al. Comparison of clinical characteristics between fecal/Perianal SWAB nucleic acid-positive and -negative patients with COVID-19. J Infect Dev Ctries 2020;14:847–52. 10.3855/jidc.12885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Zuo T, Liu Q, Zhang F, et al. Depicting SARS-CoV-2 Faecal viral activity in association with gut microbiota composition in patients with COVID-19. Gut 2021;70:276–84. 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Jung SH, Kim SW, Lee H, et al. Serial screening for SARS-CoV-2 in Rectal Swabs of symptomatic COVID-19 patients. J Korean Med Sci 2021;36:44. 10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Lei Z, Cao H, Jie Y, et al. A cross-sectional comparison of epidemiological and clinical features of patients with Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in Wuhan and outside Wuhan, China. Travel Med Infect Dis 2020;35:101664. 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Yongchen Z, Shen H, Wang X, et al. Different longitudinal patterns of nucleic acid and serology testing results based on disease severity of COVID-19 patients. Emerg Microbes Infect 2020;9:833–6. 10.1080/22221751.2020.1756699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Holm-Jacobsen JN, Bundgaard-Nielsen C, Rold LS, et al. The prevalence and clinical implications of rectal SARS-Cov-2 shedding in Danish COVID-19 patients and the general population. Front Med (Lausanne) 2021;8:804804. 10.3389/fmed.2021.804804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Wu B, Lei Z-Y, Wu K-L, et al. Compare the epidemiological and clinical features of imported and local COVID-19 cases in Hainan, China. Infect Dis Poverty 2020;9:143. 10.1186/s40249-020-00755-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Park S-K, Lee C-W, Park D-I, et al. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in fecal samples from patients with asymptomatic and mild COVID-19 in Korea. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021;19:1387–94. 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. He Y, Luo J, Yang J, et al. Value of viral nucleic acid in sputum and Feces and specific Igm/IgG in serum for the diagnosis of Coronavirus disease 2019. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2020;10:445. 10.3389/fcimb.2020.00445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Pedersen RM, Tornby DS, Bang LL, et al. Rectally shed SARS-CoV-2 in COVID-19 Inpatients is consistently lower than respiratory shedding and lacks infectivity. Clin Microbiol Infect 2022;28:304. 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.10.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Bailie CR, Franklin L, Nicholson S, et al. Symptoms and laboratory manifestations of mild COVID-19 in a repatriated cruise ship cohort. Epidemiol Infect 2021;149:e44. 10.1017/S0950268821000315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Akiyama Y, Kinoshita N, Sadamasu K, et al. A pilot study on viral load in stool samples of patients with COVID-19 suffering from diarrhea. Jpn J Infect Dis 2022;75:36–40. 10.7883/yoken.JJID.2021.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Das Adhikari U, Eng G, Farcasanu M, et al. Fecal severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) RNA is associated with decreased Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) survival. Clin Infect Dis 2022;74:1081–4. 10.1093/cid/ciab623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Jefferson T, Spencer EA, Brassey J, et al. Viral cultures for Coronavirus disease 2019 infectivity assessment: a systematic review. Clin Infect Dis 2021;73:e3884–99. 10.1093/cid/ciaa1764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Cevik M, Tate M, Lloyd O, et al. SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and MERS-Cov viral load dynamics, duration of viral shedding, and Infectiousness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Microbe 2021;2:e13–22. 10.1016/S2666-5247(20)30172-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Sun J, Zhu A, Li H, et al. Isolation of infectious SARS-CoV-2 from urine of a COVID-19 patient. Emerg Microbes Infect 2020;9:991–3. 10.1080/22221751.2020.1760144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Jeong HW, Kim S-M, Kim H-S, et al. Viable SARS-CoV-2 in various specimens from COVID-19 patients. Clin Microbiol Infect 2020;26:1520–4. 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.07.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Colavita F, Lapa D, Carletti F, et al. Virological characterization of the first 2 COVID-19 patients diagnosed in Italy: phylogenetic analysis, virus shedding profile from different body sites, and antibody response Kinetics. Open Forum Infect Dis 2020;7:ofaa403. 10.1093/ofid/ofaa403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. He Y, Wang J, Ren J, et al. Effect of COVID-19 on male reproductive system - a systematic review. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2021;12:677701. 10.3389/fendo.2021.677701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2023-073084supp001.pdf (1.8MB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.