Abstract

Introduction

The burden of mental health-related visits to emergency departments (EDs) is growing, and agitation episodes are prevalent with such visits. Best practice guidance from experts recommends early assessment of at-risk populations and pre-emptive intervention using de-escalation techniques to prevent agitation. Time pressure, fluctuating work demands, and other systems-related factors pose challenges to efficient decision-making and adoption of best practice recommendations during an unfolding behavioural crisis. As such, we propose to design, develop and evaluate a computerised clinical decision support (CDS) system, Early Detection and Treatment to Reduce Events with Agitation Tool (ED-TREAT). We aim to identify patients at risk of agitation and guide ED clinicians through appropriate risk assessment and timely interventions to prevent agitation with a goal of minimising restraint use and improving patient experience and outcomes.

Methods and analysis

This study describes the formative evaluation of the health record embedded CDS tool. Under aim 1, the study will collect qualitative data to design and develop ED-TREAT using a contextual design approach and an iterative user-centred design process. Participants will include potential CDS users, that is, ED physicians, nurses, technicians, as well as patients with lived experience of restraint use for behavioural crisis management during an ED visit. We will use purposive sampling to ensure the full spectrum of perspectives until we reach thematic saturation. Next, under aim 2, the study will conduct a pilot, randomised controlled trial of ED-TREAT at two adult ED sites in a regional health system in the Northeast USA to evaluate the feasibility, fidelity and bedside acceptability of ED-TREAT. We aim to recruit a total of at least 26 eligible subjects under the pilot trial.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval by the Yale University Human Investigation Committee was obtained in 2021 (HIC# 2000030893 and 2000030906). All participants will provide informed verbal consent prior to being enrolled in the study. Results will be disseminated through publications in open-access, peer-reviewed journals, via scientific presentations or through direct email notifications.

Trial registration number

Keywords: MENTAL HEALTH, PSYCHIATRY, Health informatics, Clinical Trial, ACCIDENT & EMERGENCY MEDICINE, Information technology

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

Given limited prior evidence on real-life implementation of best practice recommendations for agitation symptoms, this study aims to identify patient and user-centred strategies to develop a clinical decision support (CDS) system that facilitates management of agitation in an acute care setting.

Our tool will include pragmatic strategies to implement best practice recommendations for risk assessment and timely de-escalation techniques in agitation management prior to definitive psychiatric treatment.

The CDS design process will follow an iterative, user-centred approach with feedback from end-users at every step to refine and develop an electronic health record embedded, fully functional prototype.

Our risk assessment data, qualitative design, and pilot trial will arise from the same geo-political area and health system, which may limit generalisability.

Introduction

Behavioural health-related visits to emergency departments (EDs) are growing.1–3 Agitation, defined as excessive psychomotor activity leading to aggressive and violent behaviour,4 is a frequent symptom of such visits. An estimated 1.7 million agitation episodes occur annually in EDs across the USA alone.5 6 When an individual becomes agitated, they may cause harm to themselves, hospital staff, and property.7–9 Rapid management of agitation is imperative and use of physical restraint may be necessary to facilitate patient assessment and prevent injury.5 Although physical restraints are routinely used in the ED,10 11 they are associated with up to 37% risk of injury in patients, including blunt chest trauma, asphyxiation, respiratory depression, and sudden death.12–17 To address these challenges, the American Association for Emergency Psychiatry sponsored Project BETA (Best Practices in Evaluation and Treatment of Agitation).18 Project BETA was a pioneer effort to create a comprehensive list of five sets of best practices for preventing and managing agitation through multidisciplinary consensus panels. Key strategies within Project BETA included use of structured risk assessment4 to help clinicians screen patients at risk of developing agitation and pre-emptive intervention using behavioural techniques,19 environmental modification,20 and consensual use of medication therapy18 to obviate use of restraints.

Despite these established best practice recommendations, multiple systems-level barriers challenge their practical implementation.21–23 Care delivery in the ED occurs in a uniquely complex environment. Clinical decisions are made under time pressure, using limited information and amidst multiple and frequent interruptions and other unpredictable factors due to the dynamic course of acute, undifferentiated conditions.24 As burden on the emergency care system rises in the USA,25–28 these systems-level challenges are particularly relevant for patients at risk for agitation because behavioural and de-escalation techniques require investment in time and effort to build a strong rapport and trusting therapeutic relationship with the patient. Given that clinicians may have difficulty accurately identifying patients at risk for agitation and access to expert psychiatric evaluation in such settings may be limited,29–32 there is a significant mismatch between resources available and application of those resources to individuals who would most benefit from early risk assessment and intervention. A recent prospective study observing 100 at-risk patients in the ED found that over 60% of individuals develop agitation more than 30 min into their visit,33–35 presenting opportunities to prevent agitation earlier in the course.

Clinical decision support (CDS) tools can help address systems-based challenges, facilitate risk assessment, and guide clinicians to use best practices strategies recommended by Project BETA in the ED. CDS tools show increasing promise in the emergency setting to help clinical staff identify high-risk patients and provide more efficient and higher quality of care,36 including individuals requiring use of high-cost imaging37 and older adults.38–41 A CDS system encompasses any on-screen tool designed to improve healthcare delivery by enhancing medical decisions with targeted clinical knowledge, patient data and other health-related information.42 Use of a CDS tool to assist in assessment and management of potentially agitated patients may be an effective strategy in the ED.40 43 44

Rationale and aims

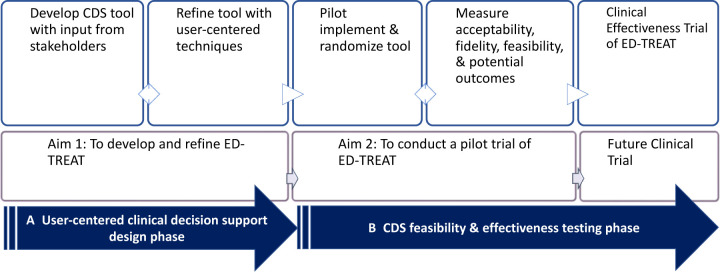

This study is one of the first that aims to prevent agitation and improve outcomes for ED patients with agitation. We will achieve this by (figure 1):

Figure 1.

Overview and steps for each phase of ED-TREAT design and pilot implementation study. CDS, clinical decision support; ED-TREAT, Early Detection and Treatment to Reduce Events with Agitation Tool.

Designing and developing an electronic health record (EHR)-embedded, user-centred, CDS system, Early Detection and Treatment to Reduce Events with Agitation Tool (ED-TREAT), using a contextual design approach to obtain input from key stakeholders and iterative user-centred design process.

Conducting a pilot study to evaluate the feasibility, fidelity and bedside acceptability of ED-TREAT. ED-TREAT aims to help ED staff and clinicians to identify patients at high risk for developing agitation, guide them through appropriate risk assessment and efficient decision-making to implement best practice recommendations for preventing development of agitation, and minimise use of restraints.

We hypothesise that, with the use of ED-TREAT, ED staff will be able to identify at-risk individuals, conduct appropriate risk assessment, implement interventions to minimise use of restraints and improve patient experience and outcomes related to agitation management in the ED. If this study is successful, a planned subsequent clinical effectiveness trial will compare effectiveness of ED-TREAT to usual care across multiple ED sites in the future. The long-term goal of this CDS tool is to increase fidelity with best practice recommendations for prevention of agitation through early use of behavioural techniques prior to onset of agitation.

Methods and analyses

Patient and public involvement

We invited patients to help us design, develop and test the intervention so that it is designed to improve the public good and help individuals with lived experience of mental illness and behavioural crises. In addition, we will solicit patient feedback and guidance on dissemination of study results to participants and the local community through networks at our affiliated community-based organisations that have had sustained engagement with our team for several years to implement a research agenda in agitation care that is patient centred and recovery oriented.

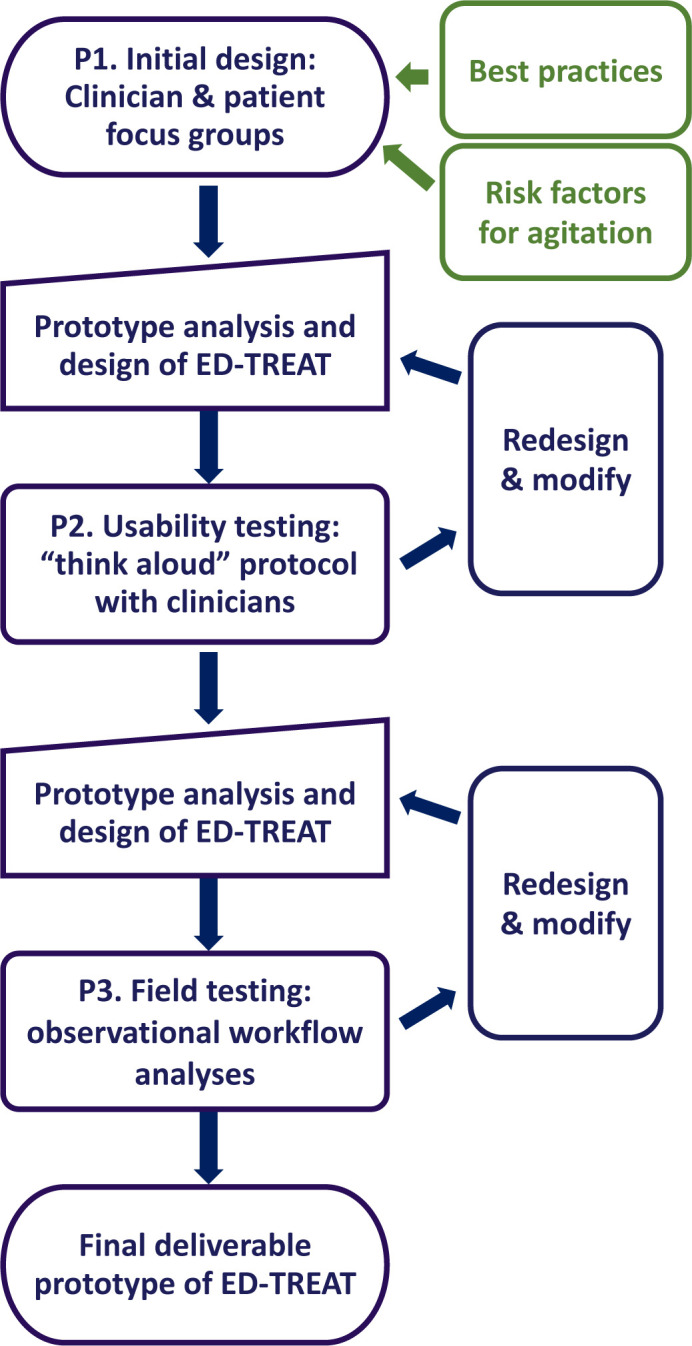

Aim 1: developing and refining ED-TREAT

With the goal of developing a final prototype that maximises usability, staff self-efficacy, satisfaction and patient-centred care, ED-TREAT will be designed, developed and refined in three phases (P1–P3) (figure 2). During phase 1 (P1), we will conduct a needs assessment to collect input from key stakeholders including ED physicians, nurses, patient care technicians, behavioural health experts, informatics experts and patients with lived experience of being restrained in the ED. We will combine needs assessment findings with Project BETA recommendations for agitation management in the ED5 and risk factors for agitation from the literature to design an initial prototype. Next, in phase 2 (P2), we will conduct formative usability testing, which will consist of ‘think aloud’ protocols, a standard usability procedure for CDS design,45 with clinician users and standardised patients in a controlled simulation setting to guide further modifications of the tool in an iterative fashion. Finally, in phase 3 (P3), we will conduct field testing in the ED through observational workflow analyses to identify and address barriers in the real-world clinical environment.

Figure 2.

Overview and steps for aim 1: ED-TREAT user-centred design and prototype development. ED-TREAT, Early Detection and Treatment to Reduce Events with Agitation Tool.

Participant recruitment

We will design ED-TREAT for use by staff members who work mostly closely with agitated patients in the ED.7 35 46–48 These consist of ED physicians, nurses and patient care technicians. We plan to recruit these staff participants via email and biweekly staff meetings. In addition, we will also recruit patients with prior lived experience of being restrained in the ED to solicit their input and ensure that patient-centred practices are considered during the design process. We will recruit these patients from the pool of peer support workers from local community-based recovery organisations via email and presentations at monthly staff meetings. These peer support workers have a history of mental health and substance use disorders and have received training to become employed as patient advocates on community-based treatment teams. Finally, our design team will interview informatics and behavioural health experts to solicit ideas and relevant CDS design strategies to improve decision-making during agitation management.49 50

Phase 1: needs assessment and initial design of ED-TREAT

We will conduct focus groups and observations starting June 2023 via a contextual inquiry36 approach. This approach seeks to engage prospective users and participants described above to understand clinical workflow, roles of different members of the patient care team and thought processes involved in managing a behavioural health crisis in the ED. We will first conduct in-depth qualitative interviews with staff and patient participants using a semistructured interview guide that will include open-ended questions to cover topics (online supplemental table 1) related to application of Project BETA recommendations in preventing agitation and user-centred design.37 Each focus group will consist of 2–5 participants from the same stakeholder group and be approximately 60 min in duration. Sessions will be audio recorded after obtaining participant verbal consent (online supplemental file 2). In addition, members of the design team will conduct observation sessions in the ED to observe ED staff during real-life agitation management events. These sessions will provide information about environmental and systems contexts, interactions among members of patient care team during an active agitation episode, and logistics of integrating CDS tool into EHR workflow to facilitate clinical decision-making.

bmjopen-2023-082834supp001.pdf (92.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-082834supp002.pdf (78.8KB, pdf)

After identifying crucial user requirements in P1, we will develop an initial low-fidelity prototype for ED-TREAT. This will occur in collaboration with EHR analysts and informatics experts by incorporating Project BETA recommendations for preventing and managing agitation5 and potential risk factors for agitation to identify potential at-risk patients in the ED. These risk factors (online supplemental table 2) will be based on existing literature on risk factors for agitation and workplace violence in the healthcare setting,4 42 51 our team’s prior work on agitation management in the ED,48 patient perspectives of ED visits resulting in restraint use,52 characterisation of physical restraint use among adults presenting to the ED with agitation,11 and attributes and levels of agitation impacting thresholds for restraint use in the ED.34 35

Preliminary work by our team has shown that identifying risk factors for agitation and implementing EHR-based interventions for agitation are feasible in the emergency setting.46 The CDS will extract patient-specific data on variables of interest from existing patient chart data via EPIC’s Cogito analytics performance suite.53 Based on current expert recommendations from Project BETA,46 we anticipate that ED-TREAT will likely stratify patients into three risk groups (table 1) and recommend increasing levels of resource utilisation and pre-emptive management as the risk level increases based on best practices for preventing agitation from Project BETA. Depending on results from the needs assessment, ED-TREAT’s recommendations may include automated order sets for medication therapy, staff instructions and communication orders and templated clinical documentation. Our team will collaborate with EHR analysts to create an initial interactive prototype within the EHR testing environment, ‘Epic Playground’, a non-production, functional, simulated EHR replica used for developing and validating new workflows. We anticipate that our final product will be an EHR-integrated web application through a dedicated graphical Application Programming Interface.54

Table 1.

Sample elements of initial ED-TREAT prototype

| Risk level | Project BETA5 guidelines | Recommended tasks |

| Negligible |

|

|

| Mild to moderate | Tasks in negligible risk level PLUS:

|

|

| High | Tasks in mild to moderate risk-level PLUS:

|

BEAT, Best Practices in Evaluation and Treatment of Agitation; ED-TREAT, Early Detection and Treatment to Reduce Events with Agitation Tool.

Phase 2: usability testing of ED-TREAT

Heuristic evaluation

We will first perform heuristic evaluation55 of CDS interface usability before testing with clinician participants. This will consist of an expert team of three evaluators with experience in emergency medicine as well as CDS design who will navigate through different aspects of the CDS and judge the compliance and usability of the tool in agitation management triangulated between their expertise and usability standards. Each evaluator will inspect the interface and assess the guidelines and recommendations provided by the CDS for various levels of agitation. After individual assessment is completed, we will debrief as a group and aggregate the results of each evaluator to examine deficiencies in the prototype design. After addressing concerns and refining the prototype CDS tool, we will conduct further usability testing with clinicians in simulated training protocols.

‘Think Aloud’ protocol

Next, our team will perform one-on-one ‘think aloud’ protocol45 sessions with clinician users in a quiet office at the EHR training classroom. We will ask participants to perform designated tasks with ED-TREAT using mock patient charts in Epic Playground and ‘think aloud’ how they would use ED-TREAT to test whether the user understands and is using the CDS as intended. We will develop a facilitator guide that focuses on domains related to usability of the prototype and design of the CDS interface (online supplemental table 3). We will videorecord each usability testing session, incorporating user screen captures and field notes56 taken during the session. At the end of the session, each participant will complete the System Usability Scale (SUS)57 to measure perceived usability of and satisfaction with a health informatics tool. The SUS is a widely used and effective survey composed of ten statements assessed on a 5-point Likert scale, with inter-item correlations of 0.69–0.75 and a reliability coefficient α of 0.91.58 Each session is expected to take 30 min.

Simulation sessions

Additionally, we will observe the clinical team in a simulation session with a live actor or mannequin simulating being an agitated patient. Participants will be briefed on how the CDS tool works and will be encouraged to use it at various points in the care process. We will similarly videorecord each session and distribute the SUS to gather participant feedback. We will make iterative refinements to the prototype until the team reaches consensus that it has reached a threshold level of usability.

Phase 3: field testing of ED-TREAT

We will recruit staff participants working in the ED for field testing of the ED-TREAT prototype through observational workflow analysis of ED visits with mild-to-moderate or high risk of agitation (table 1). We will develop an observational guide based on sample topics of usability testing (online supplemental table 3) that will detail both the workflow of managing an at-risk patient and barriers to adopting ED-TREAT in the clinical environment. Field notes will detail events, actions and their time and duration,56 while maintaining an open-ended format to describe and follow variations or workarounds in workflow. Either the PI or a trained research associate will complete the observations as an unobtrusive non-participant observer through a patient’s visit from ED arrival to patient disposition, similar to procedures we developed for prior observations of agitation.34 35 We will enter field notes using a portable electronic tablet into a word document for free text and a spreadsheet for data elements.

Data analysis

In P1 (design and development), our team will use the iterative and phased approach of building an affinity diagram, a commonly used organisational tool that allows large numbers of ideas stemming from brainstorming and qualitative data to be sorted into groups, based on their natural relationships, for review and analysis.59 60 Following completion of each focus group and contextual inquiry session, we will conduct an interpretation session to review the user-provided keynotes from the inquiry session and capture them as affinity notes.61 To help identify common issues, work patterns and needs, we will arrange the affinity notes into hierarchical categories (‘must-have’, ‘good to have’ and ‘nice to have’) based on common themes in the data to create an affinity diagram.61 Building of the affinity diagram will occur online using Miro software (RealtimeBoard, San Francisco, California, USA).62 We will mock up a low fidelity prototype of ED-TREAT based on current best practices and iteratively refine it based on user data from P1.

For P2 (usability testing) and P3 (field testing), field notes will be analysed using a deductive coding method to conduct directed content analysis63 based on predetermined usability requirements and recommended tasks from ED-TREAT (online supplemental table 3).64 We will use Dedoose (SocioCultural Research Consultants, Manhattan Beach, California, USA),65 a collaborative and cloud-based qualitative software package, for thematic analysis and data organisation of transcripts. Codes identifying suboptimal or deficient performance of the prototype will uncover critical system factors impacting adoption and usability that need optimisation and adjustment. Two trained reviewers will perform independent coding and we will calculate inter-rater reliability assessments with kappa scores. For the SUS,57 participants’ scores from each question of are added together and then multiplied by 2.5 to convert the original scores to continuous data from 0 to 100. Scores will be described using mean and SD, and >85 will be indicative of excellent usability.66 We will use the results generated from this analysis process at each round of revisions to make appropriate adjustments to the ED-TREAT prototype in close collaboration with the EHR analyst team until we derive a final deliverable prototype that will be ready for the pilot trial.

Sample size

We will use purposive sampling67 to ensure the full spectrum of perspectives for clinicians who will engage with ED-TREAT and peer support workers who have had experience as patients in the ED. We will conduct data collection until reaching thematic saturation,68 when new concepts no longer emerge from iterative analysis of the data.69 For initial design (P1), we anticipate that this will occur after 5–6 focus groups with 6 participants (staff and patients) in each focus group.70 As enrolment of 10–12 subjects can identify up to 90% of usability problems,71 we will perform usability testing (P2) for approximately 5 participants in each round of refinement and expect about three rounds of refinement (15 participants total) as per our prior published work.72 For field testing (P3), we plan to observe eight patient encounters to detect any usability problems when deployed in the ED.

Aim 2: pilot trial and feasibility testing

We will conduct a pilot randomised controlled trial (RCT) for ED-TREAT to compare the intervention to usual care. This will allow us to evaluate acceptability of the intervention to its end-users (ED staff), fidelity of its intended outcomes to identify at-risk individuals and prevent agitation, feasibility of randomisation, ease of subject enrolment and measurement of other outcomes of interest. This will be a mixed-methods study, wherein we will quantitatively measure usability and efficiency of clinical decision-making via the SUS57 and specific patient outcomes, as well as qualitatively assess the effect of ED-TREAT on clinical workflow and patient care. In addition, this pilot trial will (1) test the integrity of the study protocol in preparation for a future comparative effectiveness clinical trial, (2) evaluate randomisation protocols, (3) estimate rates of recruitment and retention of trial subjects and (4) estimate effect size for sample size calculation in the subsequent trial.73 Pilot trials74 are not designed to test the efficacy of the intervention but will help establish acceptability and feasibility in preparation for a future multicentre RCT. We hypothesise that it will be feasible to implement the tool, measure identified outcomes, be acceptable to its end-users and work as intended.

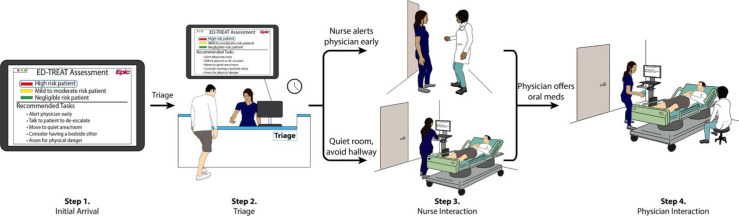

Study setting, participants and randomisation

We will conduct the pilot trial at two adult ED campuses that belong to a large regional healthcare system in the Northeast USA, with a planned trial start date in the Fall of 2024. Prior to initiation of the pilot trial, all emergency physicians, ED nurses and ED patient care technicians at both campuses will receive an email introduction and a link to a brief training regarding the use of ED-TREAT. Eligibility criteria for patients and recruitment will include ability to provide verbal consent for the study and a score of ‘4’ (quiet and awake; normal level of activity) or less on the Behavioural Activity Rating Scale (BARS),75 an accepted seven-point scale to assess levels of agitation in acute care settings. We will first perform screening for eligibility via an ED-TREAT administrative interface that performs risk assessment for each ED patient on arrival. Inclusion criteria for ED patients include adult (age ≥18) patients, presenting to the ED during the pilot trial period, deemed to have a mild-moderate or high risk of agitation as determined by ED-TREAT, do not require physical restraint orders within <30 min of arrival, with a score of ‘4’ (quiet and awake; normal level of activity) on the BARS, have comfort with conversational English, and able to provide verbal consent. Exclusion criteria include presence of a restraint order <30 min of arrival and presence of a non-violent physical restraint order where indications are not due to agitation (eg, for protecting intubation or life-preserving equipment). A research associate will then approach eligible patients and their designated clinician team members for enrolment after confirming ability to consent and assessing patient BARS scores as close to the beginning of the visit as feasible. Study procedures, risks/benefits of participating, and the purpose of ED-TREAT will be described, and verbal consent will be obtained for patients and staff participants. Since we plan to enrol patients prior to onset of agitation, we anticipate that most patients should be able to engage in decisions and provide verbal consent. Our prior work found that >70% of ED patients with subsequent agitation arrived with a normal mental status and BARS scores ≤4.34 35 We will perform 2:1 randomisation at the patient level and also recruit a higher proportion of high-risk patients in each arm, as a primary aim of the pilot trial is to test the acceptability of ED-TREAT and we anticipate that our intervention will recommend more tasks for high-risk patients. Randomisation will occur using sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes that will only be opened by the research team member after enrolment of each patient. In the intervention group, ED-TREAT will automatically launch as part of the clinical team’s workflow in the EHR after randomisation. We anticipate that critical steps in ED-TREAT will occur at four stages of a visit (figure 3): (1) at initial arrival with automated risk stratification using predetermined criteria set during the CDS design process; (2) at triage assessment; (3) at initial nurse interaction and (4) at initial clinician interaction. In the control group, ED-TREAT will notify the research team regarding the patient’s risk group but will not launch for the clinical team’s interfaces.

Figure 3.

Anticipated clinical steps for the intervention arm of ED-TREAT. ED-TREAT, Early Detection and Treatment to Reduce Events with Agitation Tool.

Data collection

Our anticipated data collection strategy is summarised in table 2. In addition to visit characteristics (system factors, relevant clinical data) collected through the EHR during the visit, we will collect acceptability and fidelity measures, feasibility assessment and potential outcomes of interest for each visit.

Table 2.

Anticipated data collection for ED-TREAT pilot trial

| Measure | Tool or strategy | Timing of measurement |

| Visit characteristics | ||

| System factors | EHR (eg, staff traits, National ED Overcrowding Scale)77 | During and end of visit |

| Clinical data | EHR/ED-TREAT (eg, risk category) | During and end of visit |

| Acceptability, fidelity | ||

| Clinician acceptability of ED-TREAT | System Usability Scale57 (satisfied, useful) | End of visit |

| Fidelity of ED-TREAT | Observational workflow checklist (perform as intended) | During visit |

| Effect on patient experience | Qualitative interviews with patients | End of visit or <72 hour after visit |

| Potential bias or differential treatment | Implicit Association Test (for clinicians), patient interviews | End of visit or <72 hour after visit |

| Feasibility | ||

| Available subjects | # of eligible visits | Every 3 months |

| Subject identification | % eligible visits approached | Every 3 months |

| Enrolment | % visits with consent to enrol from patient/clinical staff | Every 3 months |

| Retention | % visits with completed measures | Every 3 months |

| Effect on clinical workflow | Qualitative interviews with clinicians | Every 3 months |

| Outcomes | ||

| Physical restraint order | EHR | During and end of visit |

| Intramuscular chemical sedative order | EHR | During and end of visit |

| Level of agitation | Behavioural Activity Rating Scale75 | Highest level during visit |

| Disposition | EHR | End of visit |

| Length of stay | EHR | End of visit |

ED, emergency department; ED-TREAT, Early Detection and Treatment to Reduce Events with Agitation Tool; EHR, electronic health record.

For all clinicians caring for patients in the intervention group, we will administer the SUS57 either in person at the end of the ED visit or within 72 hours by email. In addition, we will perform observation workflow analyses as described earlier using a task checklist to determine if clinicians were using ED-TREAT as intended, and if any barriers or unintended consequences occurred because of the intervention. We will perform brief, semistructured interviews with patients either at the end of a visit or within 1 week after disposition to evaluate the impact of ED-TREAT on their experiences.

Feasibility

To assess the feasibility of a comparative effectiveness trial, we will evaluate the following at 3-month intervals: (1) available number of potential subjects (# of eligible patient visits), (2) subject identification (% of eligible patients/staff approached), (3) enrolment (% of patients/staff with consent to enrol) and (4) retention (% of visits with completed outcome measures). We will also conduct brief, semistructured interviews with staff participants to evaluate their experiences with ED-TREAT and effect on clinical workflow.

Outcome measures

The anticipated primary outcome of the comparative effectiveness trial will be the presence of a physical restraint order during the ED visit (>30 min after arrival). Additional secondary outcomes include the presence of an intramuscular chemical sedative order, the highest level of agitation on the BARS75 during visit, disposition and length of stay.

Sample size and data analysis

As this pilot trial is not designed to test the efficacy of ED-TREAT, a power calculation is not appropriate.73 To determine the sample size for this pilot randomised trial, we will use the outcome of fidelity as measured by the proportion of visits in the intervention arm that are adherent to >80% of the observational workflow checklist. To estimate the proportion achieving this level of fidelity with a reasonable precision (95% CI with a width of ±20%), a total of at least 26 eligible subjects will be enrolled in the pilot trial. We will determine ratings from the SUS57 and calculate proportions of each clinician group with scores of >85, indicating excellent usability. We will consider ED-TREAT to be acceptable if ≥90% of each clinician group give ratings >85. For feasibility, we will measure the proportion of potentially eligible patient visits with successful enrolment and collection of all outcomes of interest. Based on our group’s anecdotal experience with pilot studies, we will consider a comparative effectiveness trial feasible if ≥30% of visits assessed for eligibility are enrolled and ≥90% of all outcome measures are collected. Qualitative data obtained from interviews will be analysed with Dedoose using the analytic strategy mentioned earlier for iterative refinement of the study protocol in preparation for a comparative effectiveness trial.

Ethics and dissemination

We plan to conduct our study in accordance with the Yale Institutional Review Board (IRB). We have obtained the necessary regulatory and human subjects protection approvals for each aspect or phase of our protocol. Ethical approval by the Yale University Human Investigation Committee was obtained in 2021 (HIC# 2000030893 and 2000030906). After careful review, Yale IRB has approved Aim 1 of this study to be eligible for exemption of full IRB review under 45 CFR 46.104(d)(4), since any information collected by the investigator will be in such a manner that the identity of the human subjects cannot readily be ascertained directly or through identifiers linked to the subjects. Aim 2 of the study has been approved as a full protocol for a clinical trial and is undergoing annual continuing review. As we work with structured EHR patient data, we will maintain deidentification where necessary and keep access to datasets secure. Additionally, all clinicians and patients participating in focus groups, feasibility testing or the pilot trial will be informed of their rights as subjects. Clinicians will retain the right to retain control of their practice and patients will retain the right to not participate and request termination of participation at any point in the study. All staff, participants and patients will provide verbal consent prior to involvement with the study. Sample consent forms for patients and staff are included as online supplemental materials. The pilot trial is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (clinical trial registration number: NCT04959279).

Monitoring for data integrity and safety will be the responsibility of the principal investigator (AHW) and the Yale Human Investigation Committee, and a data safety monitoring board (DSMB). DSMB members will be composed of experts in care disparities and health equity for vulnerable and disadvantaged populations, clinical trials for mental illness and substance use disorders, measurement and risk stratification for disinhibited behaviours, and an expert in statistical analysis of clinical trials in emergency medicine. Twice annually, the DSMB will review the progress of the study and frequency of serious adverse events. All adverse events, as well as any unanticipated problems that arise, will be reported within 48 hours to the Human Investigation Committee. A full report will be provided annually or on request to the IRB and the sponsor’s Programme Official. The effect of adverse events on the risk/benefit ratio of the study will be re-evaluated by the investigators with each event, with appropriate adjustments made to the protocol or consent forms if needed. Given the minimal risk of the study and intervention, the investigators do not anticipate the occurrence of any serious adverse events.

Results and outcomes of the study will be disseminated through peer-reviewed journals and presentations at relevant scientific meetings throughout the study timeline. A successful pilot trial will aid in a future full RCT to fully measure the effectiveness of the ED-TREAT CDS tool in agitation management in ED settings. At the time of publication of any manuscripts that arise from this research, the deidentified data for that manuscript will be made available to share for scholarly activities. Sharing of the data will require a data use agreement to be established between the requesting and host institutions. Data will be shared through secure file transfer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to sincerely thank Mr. Justin Laing for his contributions to preparing and drafting of the figures within this manuscript.

Footnotes

Twitter: @ambrosehwong, @EM_Informatics, @TelementalHlth

Contributors: AHW, JD, KAY, SLB and ERM designed the study protocol and obtained funding. AHW is responsible for the overall logistical and scientific aspects of the study, data collection and analysis, and draft of this manuscript. DS, AK, MB, PO and IVF provided administrative and logistical support for the study. BN, RH, KA, MB, RAT and TM contributed statistical, scientific and design expertise in the development and planned scientific activities of the protocol. All authors contributed to critical revisions and gave final approval of the manuscript.

Funding: This study is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (Award Number K23 MH126366).

Disclaimer: The funder had no role in the design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Competing interests: AHW reported receiving grants from National Institute of Health outside the conduct of the study. ERM reported receiving grants and contracts from the National Institute of Health, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, American Medical Association, and Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services outside of this study. TM reported receiving grants from the National Institute of Health, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and Google outside of this study. TM is a member of the Clinical Diversity Advisory Board at Woebot Health and Advisory Board at RACE Space. RH reported receiving salary support from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to develop, implement, and maintain clinical performance outcome measures that are publicly reported, in addition to receiving research support from the US Food and Drug Administration, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute of Health, Connecticut Department of Public Health, and from the Community Health Network of Connecticut for her work as a medical consultant. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; peer reviewed for ethical and funding approval prior to submission.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1. Theriault KM, Rosenheck RA, Rhee TG. Increasing emergency department visits for mental health conditions in the United States. J Clin Psychiatry 2020;81:20m13241. 10.4088/JCP.20m13241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Santillanes G, Axeen S, Lam CN, et al. National trends in mental health-related emergency department visits by children and adults, 2009-2015. Am J Emerg Med 2020;38:2536–44. 10.1016/j.ajem.2019.12.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Capp R, Hardy R, Lindrooth R, et al. National trends in emergency department visits by adults with mental health disorders. J Emerg Med 2016;51:131–5. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2016.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nordstrom K, Zun LS, Wilson MP, et al. Medical evaluation and triage of the agitated patient: consensus statement of the american association for emergency psychiatry project Beta medical evaluation workgroup. West J Emerg Med 2012;13:3–10. 10.5811/westjem.2011.9.6863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Holloman GH, Zeller SL. Overview of project BETA: best practices in evaluation and treatment of agitation. West J Emerg Med 2012;13:1–2. 10.5811/westjem.2011.9.6865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zeller SL, Rhoades RW. Systematic reviews of assessment measures and pharmacologic treatments for agitation. Clin Ther 2010;32:403–25. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2010.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wong AH, Ray JM, Eixenberger C, et al. Qualitative study of patient experiences and care observations during agitation events in the emergency department: implications for systems-based practice. BMJ Open 2022;12:e059876. 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-059876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hooton A, Bloom BM, Backus B. Violence against healthcare workers at the emergency department. Eur J Emerg Med 2022;29:89–90. 10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gates DM, Ross CS, McQueen L. Violence against emergency department workers. J Emerg Med 2006;31:331–7. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2005.12.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wong AH, Whitfill T, Ohuabunwa EC, et al. Association of race/ethnicity and other demographic characteristics with use of physical restraints in the emergency department. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e2035241. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.35241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wong AH, Taylor RA, Ray JM, et al. Physical restraint use in adult patients presenting to a general emergency department. Ann Emerg Med 2019;73:183–92. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Grant JR, Southall PE, Fowler DR, et al. Death in custody: a historical analysis. J Forensic Sci 2007;52:1177–81. 10.1111/j.1556-4029.2007.00500.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Barnett R, Stirling C, Pandyan AD. A review of the scientific literature related to the adverse impact of physical restraint: gaining a clearer understanding of the physiological factors involved in cases of restraint-related death. Med Sci Law 2012;52:137–42. 10.1258/msl.2011.011101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zun LS. A prospective study of the complication rate of use of patient restraint in the emergency department. J Emerg Med 2003;24:119–24. 10.1016/s0736-4679(02)00738-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Korczak V, Kirby A, Gunja N. Chemical agents for the sedation of agitated patients in the ED: a systematic review. Am J Emerg Med 2016;34:2426–31. 10.1016/j.ajem.2016.09.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mohr WK, Petti TA, Mohr BD. Adverse effects associated with physical restraint. Can J Psychiatry 2003;48:330–7. 10.1177/070674370304800509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Karger B, Fracasso T, Pfeiffer H. Fatalities related to medical restraint devices-asphyxia is a common finding. Forensic Sci Int 2008;178:178–84. 10.1016/j.forsciint.2008.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wilson MP, Pepper D, Currier GW, et al. The psychopharmacology of agitation: consensus statement of the american association for emergency psychiatry project beta psychopharmacology workgroup. West J Emerg Med 2012;13:26–34. 10.5811/westjem.2011.9.6866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Richmond JS, Berlin JS, Fishkind AB, et al. Verbal de-escalation of the agitated patient: consensus statement of the American association for emergency psychiatry project BETA de-escalation workgroup. West J Emerg Med 2012;13:17–25. 10.5811/westjem.2011.9.6864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Knox DK, Holloman GH. Use and avoidance of seclusion and restraint: consensus statement of the American association for emergency psychiatry project beta seclusion and restraint workgroup. West J Emerg Med 2012;13:35–40. 10.5811/westjem.2011.9.6867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chan EW, Taylor DM, Knott JC, et al. Variation in the management of hypothetical cases of acute agitation in Australasian emergency departments. Emerg Med Australas 2011;23:23–32. 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2010.01348.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Downey LVA, Zun LS, Gonzales SJ. Frequency of alternative to restraints and seclusion and uses of agitation reduction techniques in the emergency department. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2007;29:470–4. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Richardson SK, Ardagh MW, Morrison R, et al. Management of the aggressive emergency department patient: non-pharmacological perspectives and evidence base. Open Access Emerg Med 2019;11:271–90. 10.2147/OAEM.S192884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kovacs G, Croskerry P. Clinical decision making: an emergency medicine perspective. Acad Emerg Med 1999;6:947–52. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1999.tb01246.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hooker EA, Mallow PJ, Oglesby MM. Characteristics and trends of emergency department visits in the United States (2010-2014). J Emerg Med 2019;56:344–51. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2018.12.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lane BH, Mallow PJ, Hooker MB, et al. Trends in United States emergency department visits and associated charges from 2010 to 2016. Am J Emerg Med 2020;38:1576–81. 10.1016/j.ajem.2019.158423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Peterson SM, Harbertson CA, Scheulen JJ, et al. Trends and characterization of academic emergency department patient visits: a five-year review. Acad Emerg Med 2019;26:410–9. 10.1111/acem.13550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Skinner HG, Blanchard J, Elixhauser A. Trends in Emergency Department Visits, 2006-2011. Rockville (MD): Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chang G, Weiss AP, Orav EJ, et al. Bottlenecks in the emergency department: the psychiatric clinicians’ perspective. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2012;34:403–9. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nordstrom K, Berlin JS, Nash SS, et al. Boarding of mentally Ill patients in emergency departments: American psychiatric association resource document. West J Emerg Med 2019;20:690–5. 10.5811/westjem.2019.6.42422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Richmond JS, Dragatsi D, Stiebel V, et al. American association for emergency psychiatry recommendations to address psychiatric staff shortages in emergency settings. Psychiatr Serv 2021;72:437–43. 10.1176/appi.ps.201900501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zun LS. An issue of equity of care: psychiatric patients must be treated “on par” with medical patients. Am J Psychiatry 2014;171:716–9. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14010002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wong AH-W, Combellick J, Wispelwey BA, et al. The patient care paradox: an interprofessional qualitative study of agitated patient care in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 2017;24:226–35. 10.1111/acem.13117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wong AH, Crispino L, Parker J, et al. Use of sedatives and restraints for treatment of agitation in the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med 2019;37:1376–9. 10.1016/j.ajem.2018.12.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wong AH, Crispino L, Parker JB, et al. Characteristics and severity of agitation associated with use of sedatives and restraints in the emergency department. J Emerg Med 2019;57:611–9. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2019.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Miller A, Koola JD, Matheny ME, et al. Application of contextual design methods to inform targeted clinical decision support interventions in sub-specialty care environments. Int J Med Inform 2018;117:55–65. 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2018.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Maguire M. Methods to support human-centred design. Int J Hum Comput Stud 2001;55:587–634. 10.1006/ijhc.2001.0503 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kwan JL, Lo L, Ferguson J, et al. Computerised clinical decision support systems and absolute improvements in care: meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. BMJ 2020;370:m3216. 10.1136/bmj.m3216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bright TJ, Wong A, Dhurjati R, et al. Effect of clinical decision-support systems: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2012;157:29–43. 10.7326/0003-4819-157-1-201207030-00450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kawamoto K, Houlihan CA, Balas EA, et al. Improving clinical practice using clinical decision support systems: a systematic review of trials to identify features critical to success. BMJ 2005;330:765. 10.1136/bmj.38398.500764.8F [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Garg AX, Adhikari NKJ, McDonald H, et al. Effects of computerized clinical decision support systems on practitioner performance and patient outcomes: a systematic review. JAMA 2005;293:1223–38. 10.1001/jama.293.10.1223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Phillips JP. Workplace violence against health care workers in the United States. N Engl J Med 2016;374:1661–9. 10.1056/NEJMra1501998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Musen MA, Middleton B, Greenes RA. Clinical decision-support systems. In: Shortliffe EH, Cimino JJ, eds. Biomedical Informatics: Computer Applications in Health Care and Biomedicine. London: Springer London, 2014: 643–74. 10.1007/978-1-4471-4474-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Dean NC, Jones BE, Jones JP, et al. Impact of an electronic clinical decision support tool for emergency department patients with pneumonia. Ann Emerg Med 2015;66:511–20. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Li AC, Kannry JL, Kushniruk A, et al. Integrating usability testing and think-aloud protocol analysis with “near-live” clinical simulations in evaluating clinical decision support. Int J Med Inform 2012;81:761–72. 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2012.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Roppolo LP, Morris DW, Khan F, et al. Improving the management of acutely agitated patients in the emergency department through implementation of project BETA (Best Practices in the Evaluation and Treatment of Agitation). J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open 2020;1:898–907. 10.1002/emp2.12138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wong AH, Auerbach MA, Ruppel H, et al. Addressing dual patient and staff safety through a team-based standardized patient simulation for agitation management in the emergency department. Simul Healthc 2018;13:154–62. 10.1097/SIH.0000000000000309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wong AH, Ruppel H, Crispino LJ, et al. Deriving a framework for a systems approach to agitated patient care in the emergency department. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2018;44:279–92. 10.1016/j.jcjq.2017.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Agboola IK, Coupet E, Wong AH. “The coats that we can take off and the ones we can’t”: the role of trauma-informed care on race and bias during agitation in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med 2021;77:493–8. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2020.11.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Jin RO, Anaebere TC, Haar RJ. Exploring bias in restraint use: four strategies to mitigate bias in care of the agitated patient in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 2021;28:1061–6. 10.1111/acem.14277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hahn S, Müller M, Hantikainen V, et al. Risk factors associated with patient and visitor violence in general hospitals: results of a multiple regression analysis. Int J Nurs Stud 2013;50:374–85. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.09.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wong AH, Ray JM, Rosenberg A, et al. Experiences of individuals who were physically restrained in the emergency department. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e1919381. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.19381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Epstein RH, Hofer IS, Salari V, et al. Successful implementation of a perioperative data warehouse using another hospital’s published specification from Epic’s electronic health record system. Anesth Analg 2021;132:465–74. 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Melnick ER, Holland WC, Ahmed OM, et al. An integrated web application for decision support and automation of EHR workflow: a case study of current challenges to standards-based messaging and scalability from the EMBED trial. JAMIA Open 2019;2:434–9. 10.1093/jamiaopen/ooz053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Cho H, Keenan G, Madandola OO, et al. Assessing the usability of a clinical decision support system: heuristic evaluation. JMIR Hum Factors 2022;9:e31758. 10.2196/31758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Qualitative research in health care. Analysing qualitative data. BMJ 2000;320:114–6. 10.1136/bmj.320.7227.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Bangor A, Kortum PT, Miller JT. An empirical evaluation of the system usability scale. Int J Hum-Com Int 2008;24:574–94. 10.1080/10447310802205776 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Lewis JR. The system usability scale: past, present, and future. Int J Hum-Com Int 2018;34:577–90. 10.1080/10447318.2018.1455307 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lucero A. Using affinity diagrams to evaluate interactive prototypes. In: Human-Computer Interaction – INTERACT 2015. Springer-Verlag, 2022: 231–48. 10.1007/978-3-319-22668-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Holtzblatt K, Beyer H. Contextual Design: Defining Customer-Centered Systems. Morgan Kaufmann Publishers Inc, 1997. 10.1145/1120212.1120334 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ho J, Aridor O, Parwani AV. Use of contextual inquiry to understand anatomic pathology workflow: Implications for digital pathology adoption. J Pathol Inform 2012;3:35. 10.4103/2153-3539.101794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. van den Driesche C, Kerklaan S, University of Twente EEMCS Faculty - DesignLab . The value of visual co-analysis models for an inclusive citizen science approach. Inspired by co-creation methods from design thinking. Fteval Journal 2022;2022:51–60. 10.22163/fteval.2022.571 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 2005;15:1277–88. 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Holden RJ, Carayon P, Gurses AP, et al. SEIPS 2.0: a human factors framework for studying and improving the work of healthcare professionals and patients. Ergonomics 2013;56:1669–86. 10.1080/00140139.2013.838643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Talanquer V. Using Qualitative Analysis Software To Facilitate Qualitative Data Analysis. Tools of Chemistry Education Research: American Chemical Society, 2014: 83–95. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Jenssen BP, Bryant-Stephens T, Leone FT, et al. Clinical decision support tool for parental tobacco treatment in primary care. Pediatrics 2016;137:e20154185. 10.1542/peds.2015-4185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Collingridge DS, Gantt EE. The quality of qualitative research. Am J Med Qual 2008;23:389–95. 10.1177/1062860608320646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Curry LA, Nembhard IM, Bradley EH. Qualitative and mixed methods provide unique contributions to outcomes research. Circulation 2009;119:1442–52. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.742775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Ranney ML, Meisel ZF, Choo EK, et al. Interview-based qualitative research in emergency care Part II: data collection, analysis and results reporting. Acad Emerg Med 2015;22:1103–12. 10.1111/acem.12735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Guest G, Namey E, McKenna K. How many focus groups are enough? Building an evidence base for nonprobability sample sizes. Field Methods 2017;29:3–22. 10.1177/1525822X16639015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Kushniruk AW, Patel VL. Cognitive and usability engineering methods for the evaluation of clinical information systems. J Biomed Inform 2004;37:56–76. 10.1016/j.jbi.2004.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Ray JM, Ahmed OM, Solad Y, et al. Computerized clinical decision support system for emergency department-initiated buprenorphine for opioid use disorder: user-centered design. JMIR Hum Factors 2019;6:e13121. 10.2196/13121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Lancaster GA, Dodd S, Williamson PR. Design and analysis of pilot studies: recommendations for good practice. J Eval Clin Pract 2004;10:307–12. 10.1111/j.2002.384.doc.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Thabane L, Ma J, Chu R, et al. A tutorial on pilot studies: the what, why and how. BMC Med Res Methodol 2010;10:1. 10.1186/1471-2288-10-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Swift RH, Harrigan EP, Cappelleri JC, et al. Validation of the behavioural activity rating scale (BARS): a novel measure of activity in agitated patients. J Psychiatr Res 2002;36:87–95. 10.1016/s0022-3956(01)00052-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Stowell KR, Florence P, Harman HJ, et al. Psychiatric evaluation of the agitated patient: consensus statement of the american association for emergency psychiatry project Beta psychiatric evaluation workgroup. West J Emerg Med 2012;13:11–6. 10.5811/westjem.2011.9.6868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Weiss SJ, Ernst AA, Nick TG. Comparison of the national emergency department overcrowding scale and the emergency department work index for quantifying emergency department crowding. Acad Emerg Med 2006;13:513–8. 10.1197/j.aem.2005.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2023-082834supp001.pdf (92.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-082834supp002.pdf (78.8KB, pdf)