Abstract

Background

Adhesive capsulitis (also termed frozen shoulder) is commonly treated by manual therapy and exercise, usually delivered together as components of a physical therapy intervention. This review is one of a series of reviews that form an update of the Cochrane review, 'Physiotherapy interventions for shoulder pain.'

Objectives

To synthesise available evidence regarding the benefits and harms of manual therapy and exercise, alone or in combination, for the treatment of patients with adhesive capsulitis.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL Plus, ClinicalTrials.gov and the WHO ICTRP clinical trials registries up to May 2013, unrestricted by language, and reviewed the reference lists of review articles and retrieved trials, to identify potentially relevant trials.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐randomised trials, including adults with adhesive capsulitis, and comparing any manual therapy or exercise intervention versus placebo, no intervention, a different type of manual therapy or exercise or any other intervention. Interventions included mobilisation, manipulation and supervised or home exercise, delivered alone or in combination. Trials investigating the primary or adjunct effect of a combination of manual therapy and exercise were the main comparisons of interest. Main outcomes of interest were participant‐reported pain relief of 30% or greater, overall pain (mean or mean change), function, global assessment of treatment success, active shoulder abduction, quality of life and the number of participants experiencing adverse events.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently selected trials for inclusion, extracted the data, performed a risk of bias assessment and assessed the quality of the body of evidence for the main outcomes using the GRADE approach.

Main results

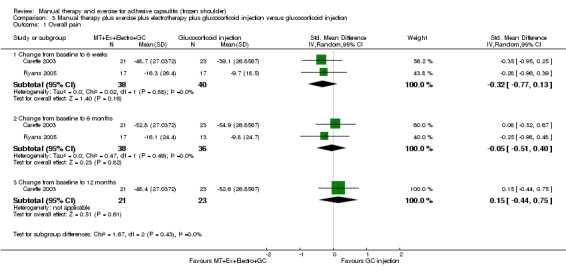

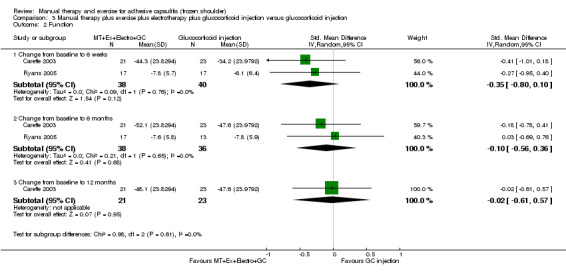

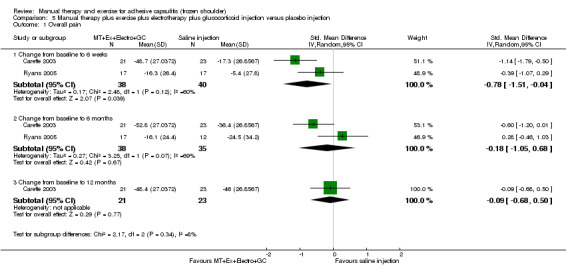

We included 32 trials (1836 participants). No trial compared a combination of manual therapy and exercise versus placebo or no intervention. Seven trials compared a combination of manual therapy and exercise versus other interventions but were clinically heterogeneous, so opportunities for meta‐analysis were limited. The overall impression gained from these trials is that the few outcome differences between interventions that were clinically important were detected only up to seven weeks. Evidence of moderate quality shows that a combination of manual therapy and exercise for six weeks probably results in less improvement at seven weeks but a similar number of adverse events compared with glucocorticoid injection. The mean change in pain with glucocorticoid injection was 58 points on a 100‐point scale, and 32 points with manual therapy and exercise (mean difference (MD) 26 points, 95% confidence interval (CI) 15 points to 37 points; one RCT, 107 participants), for an absolute difference of 26% (15% to 37%). Mean change in function with glucocorticoid injection was 39 points on a 100‐point scale, and 14 points with manual therapy and exercise (MD 25 points, 95% CI 35 points to 15 points; one RCT, 107 participants), for an absolute difference of 25% (15% to 35%). Forty‐six per cent (26/56) of participants reported treatment success with manual therapy and exercise compared with 77% (40/52) of participants receiving glucocorticoid injection (risk ratio (RR) 0.6, 95% CI 0.44 to 0.83; one RCT, 108 participants), with an absolute risk difference of 30% (13% to 48%). The number reporting adverse events did not differ between groups: 56% (32/57) reported events with manual therapy and exercise, and 53% (30/57) with glucocorticoid injection (RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.49; one RCT, 114 participants), with an absolute risk difference of 4% (‐15% to 22%). Group differences in improvement in overall pain and function at six months and 12 months were not clinically important.

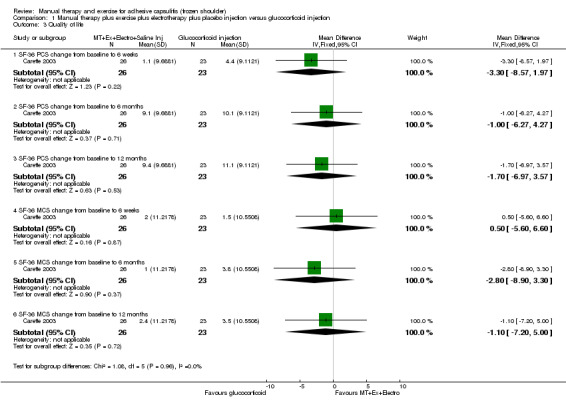

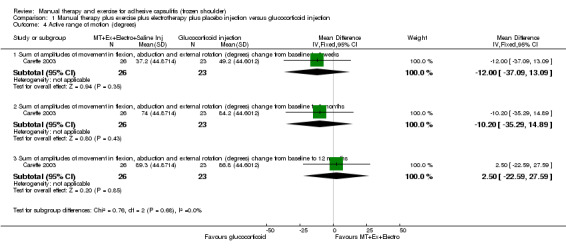

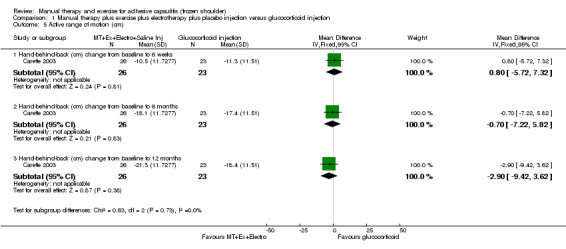

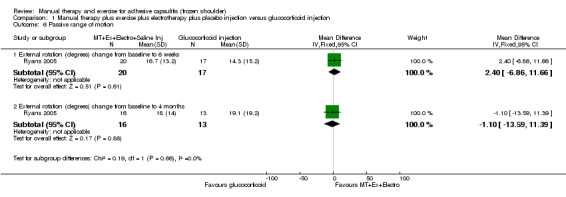

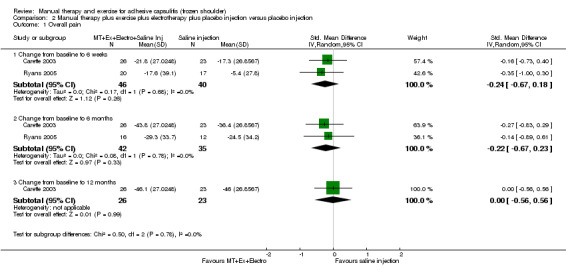

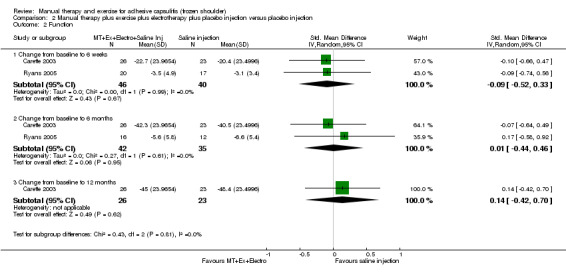

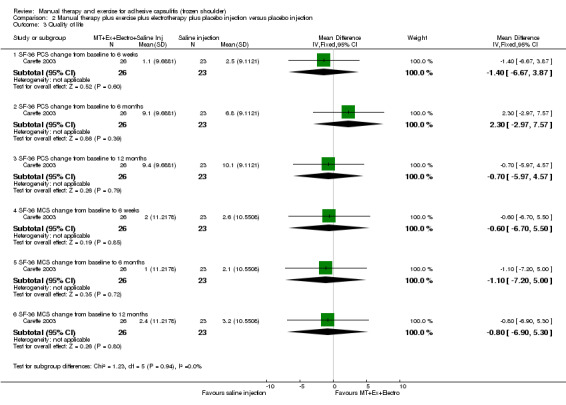

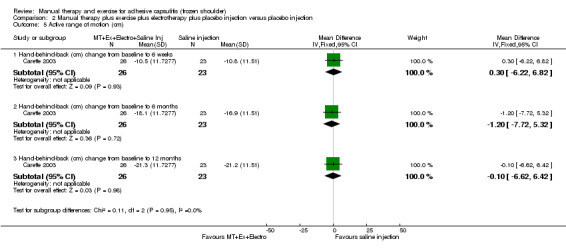

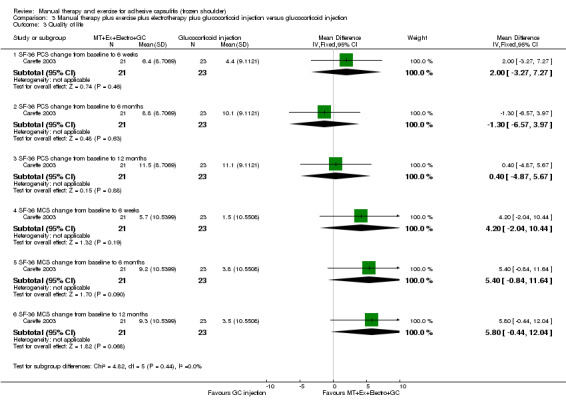

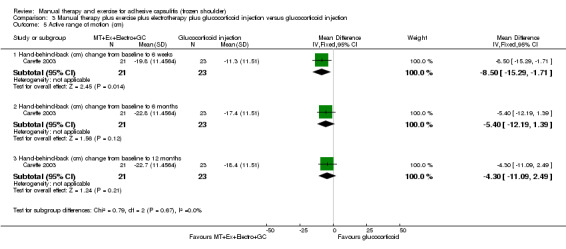

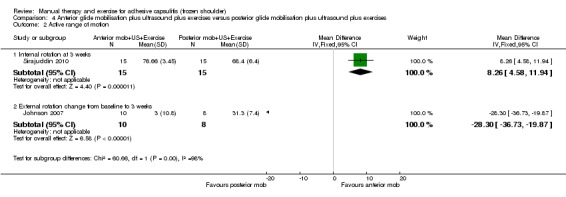

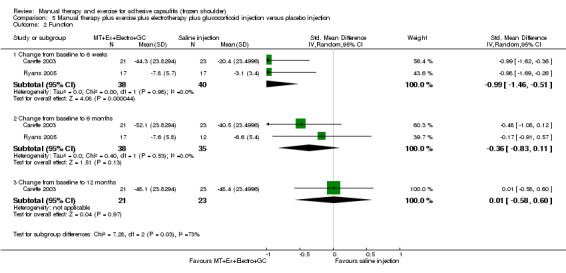

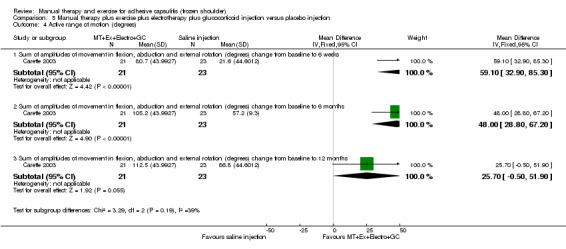

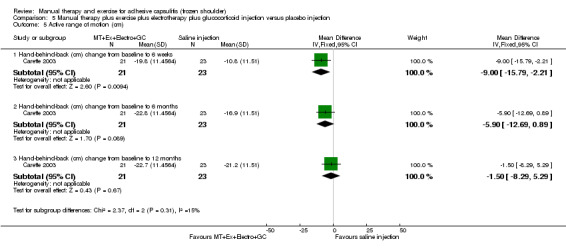

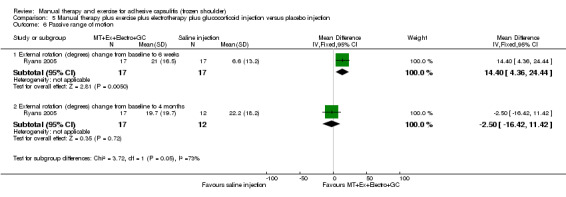

We are uncertain of the effect of other combinations of manual therapy and exercise, as most evidence is of low quality. Meta‐analysis of two trials (86 participants) suggested no clinically important differences between a combination of manual therapy, exercise, and electrotherapy for four weeks and placebo injection compared with glucocorticoid injection alone or placebo injection alone in terms of overall pain, function, active range of motion and quality of life at six weeks, six months and 12 months (though the 95% CI suggested function may be better with glucocorticoid injection at six weeks). The same two trials found that adding a combination of manual therapy, exercise and electrotherapy for four weeks to glucocorticoid injection did not confer clinically important benefits over glucocorticoid injection alone at each time point. Based on one high quality trial (148 participants), following arthrographic joint distension with glucocorticoid and saline, a combination of manual therapy and supervised exercise for six weeks conferred similar effects to those of sham ultrasound in terms of overall pain, function and quality of life at six weeks and at six months, but provided greater patient‐reported treatment success and active shoulder abduction at six weeks. One trial (119 participants) found that a combination of manual therapy, exercise, electrotherapy and oral non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drug (NSAID) for three weeks did not confer clinically important benefits over oral NSAID alone in terms of function and patient‐reported treatment success at three weeks.

On the basis of 25 clinically heterogeneous trials, we are uncertain of the effect of manual therapy or exercise when not delivered together, or one type of manual therapy or exercise versus another, as most reported differences between groups were not clinically or statistically significant, and the evidence is mostly of low quality.

Authors' conclusions

The best available data show that a combination of manual therapy and exercise may not be as effective as glucocorticoid injection in the short‐term. It is unclear whether a combination of manual therapy, exercise and electrotherapy is an effective adjunct to glucocorticoid injection or oral NSAID. Following arthrographic joint distension with glucocorticoid and saline, manual therapy and exercise may confer effects similar to those of sham ultrasound in terms of overall pain, function and quality of life, but may provide greater patient‐reported treatment success and active range of motion. High‐quality RCTs are needed to establish the benefits and harms of manual therapy and exercise interventions that reflect actual practice, compared with placebo, no intervention and active interventions with evidence of benefit (e.g. glucocorticoid injection).

Keywords: Adult; Female; Humans; Male; Middle Aged; Bursitis; Bursitis/therapy; Exercise Therapy; Exercise Therapy/methods; Glucocorticoids; Glucocorticoids/therapeutic use; Injections, Intra‐Articular; Musculoskeletal Manipulations; Musculoskeletal Manipulations/methods; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Shoulder Pain; Shoulder Pain/therapy

Plain language summary

Manual therapy and exercise for frozen shoulder (adhesive capsulitis)

Background

Frozen shoulder is a common cause of shoulder pain and stiffness. The pain and stiffness can last up to two to three years before going away, and in the early stages it can be very painful.

Manual therapy comprises movement of the joints and other structures by a healthcare professional (e.g. physiotherapist). Exercise includes any purposeful movement of a joint, muscle contraction or prescribed activity. The aims of both treatments are to relieve pain, increase joint range and improve function.

Study characteristics

This summary of an updated Cochrane review presents what we know from research about the benefits and harms of manual therapy and exercise in people with frozen shoulder. After searching for all relevant studies published up to May 2013, we included 32 trials (1836 participants). Among the included participants, 54% were women, average age was 55 years and average duration of the condition was six months. The average duration of manual therapy and exercise interventions was four weeks.

Key results—manual therapy and exercise compared with glucocorticoid (a steroid that reduces inflammation) injection into the shoulder

Pain (higher scores mean worse pain)

People who had manual therapy and exercise for six weeks did not improve as much as people who had glucocorticoid injection—improvement in pain was 26 points less (ranging from 15 to 37 points less) at seven weeks (26% absolute less improvement).

• People who had manual therapy and exercise rated their change in pain score as 32 points on a scale of 0 to 100 points.

• People who had glucocorticoid injection rated their change in pain score as 58 points on a scale of 0 to 100 points.

Function (lower scores mean better function)

People who had manual therapy and exercise for six weeks did not improve as much as people who had glucocorticoid injection—improvement in function was 25 points less (ranging from 15 to 35 points less) at seven weeks (25% absolute less improvement).

• People who had manual therapy and exercise rated their change in function as 14 points on a scale of 0 to 100 points.

• People who had glucocorticoid injection rated their change in function as 39 points on a scale of 0 to 100 points.

Treatment success

31 fewer people out of 100 rated their treatment as successful with manual therapy and exercise for six weeks compared with glucocorticoid injection—31% absolute less improvement (ranging from 13% to 48% less improvement).

• 46 out of 100 people reported treatment success with manual therapy and exercise.

• 77 out of 100 people reported treatment success with glucocorticoid injection.

Side effects

Out of 100 people, three had minor side effects such as temporary pain after treatment with manual therapy and exercise for six weeks compared with glucocorticoid injection.

• 56 out of 100 people reported side effects with manual therapy and exercise.

• 53 out of 100 people reported side effects with glucocorticoid injection.

Quality of the evidence

Evidence of moderate quality shows that the combination of manual therapy and exercise probably improves pain and function less than glucocorticoid injection up to seven weeks, and probably does not result in more adverse events. Further research may change the estimate.

Low‐quality evidence suggests that (1) the combination of manual therapy, exercise and electrotherapy (such as therapeutic ultrasound) may not improve pain or function more than glucocorticoid injection or placebo injection into the shoulder, (2) the combination of manual therapy, exercise, electrotherapy and glucocorticoid injection may not improve pain or function more than glucocorticoid injection alone and (3) the combination of manual therapy, exercise, electrotherapy and oral non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drug (NSAID) may not improve function more than oral NSAID alone. Further research is likely to change the estimate.

High‐quality evidence shows that following arthrographic joint distension, the combination of manual therapy and exercise does not improve pain or function more than sham ultrasound, but may provide greater patient‐reported treatment success and active range of motion. Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect.

No trial compared the combination of manual therapy and exercise versus placebo or no intervention.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Combination of manual therapy and exercise compared with glucocorticoid injection for adhesive capsulitis (frozen shoulder).

| Combination of manual therapy and exercise compared with glucocorticoid injection for adhesive capsulitis (frozen shoulder) | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with adhesive capsulitis (frozen shoulder) Settings: general practices in high‐income countries Intervention: manual therapy plus exercise for six weeks Comparison: glucocorticoid injection | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Glucocorticoid injection | Manual therapy plus exercise | |||||

| Participant‐reported pain relief ≥ 30% | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No studies reported this outcome |

| Overall pain (change from baseline) 0‐100 visual analogue scale (lower score = less pain) Follow‐up: 7 weeks | Mean overall pain (change from baseline) in the control group was 58 points | Mean overall pain (change from baseline) in the intervention group was 26 points lower (36.8‐15.2 lower) | 107 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatea | Absolute risk difference 26% (37% to 15% fewer); relative percentage change 30% (43% to 17% fewer) NNTB 3 (2 to 4) |

|

| Function (change from baseline) Shoulder Disabilty Questionnaire 0‐100 (lower scores = better function) Follow‐up: 7 weeks | Mean function (change from baseline) in the control group was 39 points | Mean function (change from baseline) in the intervention group was 25 points lower (35.24‐14.76 lower) | 107 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatea | Absolute risk difference 25% (35% to 15% fewer); relative percentage change 38% (51% to 22% fewer) NNTB 3 (2 to 4) |

|

| Global assessment of treatment success Complete recovery or much improvement (self‐rated) Follow‐up: 7 weeks | Study populationb | RR 0.6 (0.44‐0.83) | 108 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatea | Absolute risk difference 30% (48% to 13% fewer); relative percentage change 40% (56% to 17% fewer). NNTB 4 (3 to 8) |

|

| 769 per 1000 | 462 per 1000 (338‐638) | |||||

| Active shoulder abduction | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No studies reported this outcome |

| Quality of life | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No studies reported this outcome |

| Adverse events | Study population | RR 1.07 (0.76‐1.49) | 114c (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatea | Absolute risk difference 4% (15% fewer to 22% more); relative percentage change 7% (24% fewer to 49% more) NNTH not applicable Adverse events recorded included pain after treatment < 1 day or > 2 days, facial flushing, irregular menstrual bleeding, fever and skin irritation |

|

| 526 per 1000 | 563 per 1000 (400‐784) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; NNTB: number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome; NNTH: number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aParticipants were not blinded. bRisk of treatment success in the glucocorticoid injection group of van der Windt 1998 used as the assumed control group risk.

cIncludes 56 participants in the manual therapy and exercises group, who were treated according to protocol, 1 participant treated with both interventions, 52 participants in the glucocorticoid injection group who were treated according to protocol and 5 participants treated with both interventions.

Summary of findings 2. Combination of manual therapy, exercise, electrotherapy and placebo injection compared with glucocorticoid injection for adhesive capsulitis (frozen shoulder).

| Combination of manual therapy, exercise, electrotherapy and placebo injection compared with glucocorticoid injection for adhesive capsulitis (frozen shoulder) | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with adhesive capsulitis (frozen shoulder) Settings: outpatient rheumatology clinic and general practices in high‐income countries Intervention: manual therapy plus exercise plus electrotherapy for four weeks plus placebo injection Comparison: glucocorticoid injection | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Glucocorticoid injection | Manual therapy plus exercise plus electrotherapy plus placebo injection | |||||

| Participant‐reported pain relief ≥ 30% | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No studies reported this outcome |

| Overall pain (change from baseline) Shoulder Pain and Disability Questionnaire (SPADI, 0‐100) (lower scores = less pain)a Follow‐up: mean 6 weeks | Mean overall pain (change from baseline) in the control groups was 39.1b | Mean overall pain (change from baseline) in the intervention groups was 3.78 lower (19.26 lower‐11.7 higher)c | 86 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowd,e,f | Absolute risk difference 4% (19% fewer to 12% more);

relative percentage change 5% (27% fewer to 17% more). NNTB not applicable SMD 0.21 (‐0.65 to 1.07) |

|

| Function (change from baseline) Shoulder Pain and Disability Questionnaire (SPADI, 0‐100) (lower scores = better function)g Follow‐up: mean 6 weeks | Mean function (change from baseline) in the control groups was 34.2h | Mean function (change from baseline) in the intervention groups was 8.56 lower (0.56‐16.56 lower)i | 86 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowd,j | Absolute risk difference 9% (1% to 16% fewer);

relative percentage change 14% (1% to 26% fewer) NNTB 5 (3 to 68) SMD 0.46 (0.03 to 0.89) |

|

| Global assessment of treatment success | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No studies reported this outcome |

| Active shoulder abduction | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No studies reported this outcome |

|

Quality of life (change from baseline) SF‐36 Physical Component Score (0‐100) (lower scores = worse quality of life) Follow‐up: 6 weeks |

Mean quality of life (change from baseline) in the control group was 4.4 |

Mean quality of life (change from baseline) in the intervention group was 3.3 lower (8.57 lower‐1.97 higher) |

49 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowk,l | Absolute risk difference 3% (9% fewer to 2% more);

relative percentage change 9% (23% fewer to 5% more) NNTB not applicable |

|

| Adverse events | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No studies reported this outcome |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; NNTB: number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome; SD: standard deviation; SF: Short Form; SMD: standardised mean difference; SPADI: Shoulder Pain and Disability Index; VAS: visual analogue scale. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aPain measured using the SPADI in Carette 2003 and daytime rest pain (VAS 0‐100) in Ryans 2005. Results analysed using SMDs and back‐transformed to the 0‐100 SPADI scale units. bGlucocorticoid injection group mean reported in Carette 2003 used as the assumed control group risk. cTo convert SMDs in the Carette 2003 and Ryans 2005 meta‐analyses of overall pain scores, the pooled baseline SD in Carette 2003 (SD = 18) was multiplied by the SMDs and the 95% CIs to convert values to a 100‐point SPADI pain score. dParticipants were not blinded in either trial, and risk of attrition bias was high in 1 trial (Ryans 2005). eStatistical heterogeneity was high (I2 = 75%, with the direction of effect differing between trials).

f95% CIs relatively wide, incorporating (1) a clinically insignificant difference favouring combined intervention, (2) no difference between groups and (3) a minimal clinically important difference favouring glucocorticoid injection as possible estimates of effect. gFunction measured using the SPADI in Carette 2003 and using the Croft Shoulder Disability Questionnaire in Ryans 2005. Results analysed using SMDs and back‐transformed to the 0‐100 SPADI scale units.

hGlucocorticoid injection group mean reported in Carette 2003 used as the assumed control group risk.

iTo convert SMDs in the Carette 2003 and Ryans 2005 meta‐analyses of function scores, the pooled baseline SD in Carette 2003 (SD = 18.6) was multiplied by the SMDs and the 95% CIs to convert values to a 100‐point SPADI disability score.

j95% CIs relatively wide, incorporating both a clinically insignificant difference and a minimal clinically important difference favouring glucocorticoid injection as possible estimates of effect.

kParticipants not blinded.

l95% CIs relatively wide, incorporating (1) a clinically insignificant difference favouring combined intervention, (2) no difference between groups and (3) a clinically insignificant difference favouring glucocorticoid injection as possible estimates of effect.

Summary of findings 3. Combination of manual therapy, exercise, electrotherapy and placebo injection compared with placebo injection for adhesive capsulitis (frozen shoulder).

| Combination of manual therapy, exercise, electrotherapy and placebo injection compared with placebo injection for adhesive capsulitis (frozen shoulder) | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with adhesive capsulitis (frozen shoulder) Settings: outpatient rheumatology clinic and general practices in high‐income countries Intervention: manual therapy plus exercise plus electrotherapy for four weeks plus placebo injection Comparison: placebo injection | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo injection | Manual therapy plus exercise plus electrotherapy plus placebo injection | |||||

| Participant‐reported pain relief ≥ 30% | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No studies reported this outcome |

| Overall pain (change from baseline) Shoulder Pain and Disability Questionnaire (SPADI, 0‐100) (lower scores = less pain)a Follow‐up: mean 6 weeks | Mean overall pain (change from baseline) in the control groups was 17.3b | Mean overall pain (change from baseline) in the intervention groups was 4.32 higher (3.24 lower‐12.06 higher)c | 86 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowd,e | Absolute risk difference 4% (3% fewer to 12% more);

relative percentage change 6% (5% fewer to 17% more) NNTB not applicable SMD ‐0.24 (‐0.67 to 0.18) |

|

| Function (change from baseline) Shoulder Pain and Disability Questionnaire (SPADI, 0‐100) (lower scores = better function)f Follow‐up: mean 6 weeks | Mean function (change from baseline) in the control groups was 20.4g | Mean function (change from baseline) in the intervention groups was 1.67 higher (6.14 lower‐9.67 higher)h | 86 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowd,e | Absolute risk difference 2% (6% fewer to 10% more);

relative percentage change 3% (9% fewer to 15% more) NNTB not applicable SMD ‐0.09 (‐0.52 to 0.33) |

|

| Global assessment of treatment success | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No studies reported this outcome |

| Active shoulder abduction | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No studies reported this outcome |

|

Quality of life (change from baseline) SF‐36 Physical Component Score (0‐100) (lower scores = worse quality of life) Follow‐up: 6 weeks |

Mean quality of life (change from baseline) in the control group was 2.5 |

Mean quality of life (change from baseline) in the intervention group was 1.4 lower (6.67 lower‐3.87 higher) |

49 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowi,j | Absolute risk difference 1% (7% fewer to 4% more);

relative percentage change 4% (18% fewer to 11% more) NNTB not applicable |

|

| Adverse events | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No studies reported this outcome |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; NNTB: number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome; SMD: standardised mean difference; SPADI: Shoulder Pain an Disability Index. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aPain measured using the SPADI in Carette 2003 and daytime rest pain (VAS 0‐100) in Ryans 2005. Results analysed using SMDs and back‐transformed to 0‐100 SPADI scale units. bPlacebo injection group mean reported in Carette 2003 used as the assumed control group risk. cTo convert SMDs in the Carette 2003 and Ryans 2005 meta‐analyses of overall pain scores, the pooled baseline SD in Carette 2003 (SD = 18) was multiplied by the SMDs and the 95% CIs to convert values to a 100‐point SPADI pain score. dParticipants were not blinded in either trial, and risk of attrition bias was high in 1 trial (Ryans 2005). e95% CIs relatively wide, incorporating (1) a clinically insignificant difference favouring combined intervention, (2) no difference between groups and (3) a clinically insignificant difference favouring placebo injection as possible estimates of effect. fFunction measured using the SPADI in Carette 2003 and using the Croft Shoulder Disability Questionnaire in Ryans 2005. Results analysed using SMDs and back‐transformed to 0‐100 SPADI scale units.

gPlacebo injection group mean reported in Carette 2003 used as the assumed control group risk.

hTo convert SMDs in the Carette 2003 and Ryans 2005 meta‐analyses of function scores, the pooled baseline SD in Carette 2003 (SD = 18.6) was multiplied by the SMDs and the 95% CIs to convert values to a 100‐point SPADI disability score.

iParticipants not blinded.

j95% CIs relatively wide, incorporating (1) a clinically insignificant difference favouring combined intervention, (2) no difference between groups and (3) a clinically insignificant difference favouring placebo injection as possible estimates of effect.

Summary of findings 4. Combination of manual therapy, exercise, electrotherapy and glucocorticoid injection compared with glucocorticoid injection for adhesive capsulitis (frozen shoulder).

| Combination of manual therapy, exercise, electrotherapy and glucocorticoid injection compared with glucocorticoid injection for adhesive capsulitis (frozen shoulder) | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with adhesive capsulitis (frozen shoulder) Settings: outpatient rheumatology clinic and general practices in high‐income countries Intervention: manual therapy plus exercise plus electrotherapy for four weeks plus glucocorticoid injection Comparison: glucocorticoid injection | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Glucocorticoid injection | Manual therapy plus exercise plus electrotherapy plus glucocorticoid injection | |||||

| Participant‐reported pain relief ≥ 30% | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No studies reported this outcome |

| Overall pain (change from baseline) Shoulder Pain and Disability Questionnaire (SPADI, 0‐100) (lower scores = less pain)a Follow‐up: mean 6 weeks | Mean overall pain (change from baseline) in the control groups was 39.1b | Mean overall pain (change from baseline) in the intervention groups was 5.76 lower (13.86 lower‐2.34 higher)c | 86 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowd,e | Absolute risk difference 6% (14% fewer to 2% more);

relative percentage change 8% (20% fewer to 3% more) NNTB not applicable SMD ‐0.32 (‐0.77 to 0.13) |

|

| Function (change from baseline) Shoulder Pain and Disability Questionnaire (SPADI, 0‐100) (lower scores = better function)f Follow‐up: mean 6 weeks | Mean function (change from baseline) in the control groups was 34.2g | Mean function (change from baseline) in the intervention groups was 6.51 lower (14.88 lower‐1.86 higher)h | 86 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowd,e | Absolute risk difference 7% (15% fewer to 2% more);

relative percentage change 10% (24% fewer to 3% more) NNTB not applicable SMD ‐0.35 (‐0.80 to 0.10) |

|

| Global assessment of treatment success | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No studies reported this outcome |

| Active shoulder abduction | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No studies reported this outcome |

|

Quality of life (change from baseline) SF‐36 Physical Component Score (0‐100) (lower scores = worse quality of life) Follow‐up: 6 weeks |

Mean quality of life (change from baseline) in the control group was 4.4 |

Mean quality of life (change from baseline) in the intervention group was 2 higher (3.27 lower‐7.27 higher) |

44 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowi,j | Absolute risk difference 2% (3% fewer to 7% more);

relative percentage change 5% (9% fewer to 19% more) NNTB not applicable |

|

| Adverse events | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No studies reported this outcome |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; NNTB: number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome; SF: Short Form; SMD: standardised mean difference; SPADI: Shoulder Pain and Disability Index. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aPain measured using the SPADI in Carette 2003 and daytime rest pain (VAS 0‐100) in Ryans 2005. Results analysed using SMDs and back‐transformed to 0‐100 SPADI scale units. bGlucocorticoid injection group mean reported in Carette 2003 used as the assumed control group risk. cTo convert SMDs in the Carette 2003 and Ryans 2005 meta‐analyses of overall pain scores, the pooled baseline SD in Carette 2003 (SD = 18) was multiplied by the SMDs and the 95% CIs to convert values to a 100‐point SPADI pain score. dParticipants were not blinded in either trial, and risk of attrition bias was high in 1 trial (Ryans 2005). e95% CIs relatively wide, incorporating (1) a minimal clinically important difference favouring combined intervention, (2) no difference between groups and (3) a clinically insignificant difference favouring glucocorticoid injection alone as possible estimates of effect. fFunction measured using the SPADI in Carette 2003 and using the Croft Shoulder Disability Questionnaire in Ryans 2005. Results analysed using SMDs and back‐transformed to 0‐100 SPADI scale units.

gGlucocorticoid injection group mean reported in Carette 2003 used as the assumed control group risk.

hTo convert SMDs in the Carette 2003 and Ryans 2005 meta‐analyses of function scores, the pooled baseline SD in Carette 2003 (SD = 18.6) was multiplied by the SMDs and the 95% CIs to convert values to a 100‐point SPADI disability score.

iParticipants not blinded.

j95% CIs relatively wide, incorporating (1) a clinically insignificant difference favouring combined intervention, (2) no difference between groups and (3) a clinically insignificant difference favouring glucocorticoid injection as possible estimates of effect.

Summary of findings 5. Combination of manual therapy and exercise following joint distension compared with sham ultrasound following joint distension for adhesive capsulitis (frozen shoulder).

| Combination of manual therapy and exercise following joint distension compared with sham ultrasound following joint distension for adhesive capsulitis (frozen shoulder) | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with adhesive capsulitis (frozen shoulder) Settings: primary care and specialist practice in high‐income country Intervention: manual therapy plus exercise for six weeks following joint distension Comparison: sham ultrasound following joint distension | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Sham ultrasound following joint distension | Manual therapy plus exercise following joint distension | |||||

| Participant‐reported pain relief ≥ 30% | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No studies reported this outcome |

| Overall pain (change from baseline) 0‐10 visual analogue scale (lower scores = lower pain) Follow‐up: 6 weeks | Mean overall pain (change from baseline) in the control group was 3.4 | Mean overall pain (change from baseline) in the intervention group was 0 higher (0.69 lower‐0.69 higher) | 148 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | Absolute risk difference 0% (7% fewer to 7% more);

relative percentage change 0% (13% fewer to 13% more) NNTB not applicable |

|

| Function (change from baseline) SPADI 0‐100 (lower scores = better function) Follow‐up: 6 weeks | Mean function (change from baseline) in the control group was 38.5 | Mean function (change from baseline) in the intervention group was 0.5 lower (7.6 lower‐6.6 higher) | 148 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | Absolute risk difference 1% (8% fewer‐7% more);

relative percentage change 1% (12% fewer to 11% more) NNTB not applicable |

|

|

Active shoulder abduction (change from baseline) Degrees Follow‐up: 6 weeks |

Mean active range of abduction (change from baseline) in the control group was 36 |

Mean active range of abduction (change from baseline) in the intervention group was 13.1 higher (4.2‐22 higher) |

148 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | Absolute risk difference 7% (2% fewer to 12% more);

relative percentage change 19% (6% to 33% more). NNTB not calculated because there is no established minimal clinically important difference for this outcome. |

|

|

Quality of life (change from baseline) SF‐36 Physical Component Score (0‐100) (lower scores = worse quality of life) Follow‐up: 6 weeks |

Mean quality of life (change from baseline) in the control group was 8.3 |

Mean quality of life (change from baseline) in the intervention group was 0.5 lower (4.25 lower‐3.25 higher) |

148 (1 study) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | Absolute risk difference 1% (4% fewer to 3% more);

relative percentage change 2% (14% fewer to 11% more) NNTB not applicable |

|

| Global assessment of treatment success "Success, much improved, and/or completely recovered" (self‐rated) Follow‐up: 6 weeks | Study populationa | RR 1.33 (1.04‐1.69) | 148 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | Absolute risk difference 19% (3% to 34% more);

relative percentage change 33% (4% to 69% more) NNTB = 6 (3 to 45) |

|

| 562 per 1000 | 747 per 1000 (584‐949) | |||||

| Adverse events | Study population | RR 0.99 (0.14‐6.82) | 149 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | Absolute risk difference 0% (5% fewer to 5% more);

relative percentage change 1% (86% fewer to 582% more) NNTH not applicable |

|

| 27 per 1000 | 27 per 1000 (4‐184) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; NNTB: number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome; NNTH: number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aRisk of treatment success in the sham ultrasound group of Buchbinder 2007 used as the assumed control group risk.

Summary of findings 6. Combination of manual therapy, exercise, electrotherapy and oral NSAID compared with oral NSAID for adhesive capsulitis (frozen shoulder).

| Combination of manual therapy, exercise, electrotherapy and NSAID compared with NSAID for adhesive capsulitis (frozen shoulder) | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with adhesive capsulitis (frozen shoulder) Settings: orthopaedic and rehabilitation clinic in low‐ to middle‐income countries Intervention: manual therapy plus exercise plus electrotherapy plus oral NSAID Comparison: oral NSAID | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Oral NSAID | Manual therapy plus exercise plus electrotherapy plus oral NSAID | |||||

| Participant‐reported pain relief ≥ 30% | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No studies reported this outcome |

| Overall pain | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No studies reported this outcome |

| Function (change from baseline) Shoulder Pain and Disability Questionnaire (SPADI, 0‐100) (lower scores = better function) Follow‐up: 3 weeks | Mean function (change from baseline) in the control group was 11.9 | Mean function (change from baseline) in the intervention group was 8.6 higher (3.28‐13.92 higher) | 119 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa,b | Absolute risk difference 9% (3% to 14% more);

relative percentage change 17% (6% to 28% more) NNTB 4 (2 to 10) |

|

| Global assessment of treatment success "Disappearance of shoulder complaints or some pain/limitation which does not interfere with everyday life" Follow‐up: 6 weeks | Study population | RR 1.45 (0.99‐2.12) | 109 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa | Absolute risk difference 19% (1% to 38% more);

relative percentage change 45% (1% fewer to 112% more) NNTH not applicable |

|

| 423 per 1000 | 613 per 1000 (419‐897) | |||||

| Active shoulder abduction | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No studies reported this outcome |

| Quality of life | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | ‐ | See comment | No studies reported this outcome |

| Adverse events Pain persisting longer than 2 hours after treatment (during the 3‐week treatment period) Follow‐up: 3 weeks | Study population | RR 8.85 (0.49‐160.87) | 119 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa,c | Absolute risk difference 7% (1% fewer to 14% more);

relative percentage change 785% (51% fewer to 15987% more) NNTH not applicable |

|

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0‐0) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; NNTB: number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome; NNTH: number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome; NSAID: non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drug; RR: risk ratio; SPADI: Shoulder Pain and Disability Index. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aParticipants were not blinded. b95% CI relatively wide, incorporating both a clinically insignificant difference and a minimal clinically important difference favouring the combined intervention group.

c95% CI very wide.

Background

Description of the condition

This review is one of a series of reviews seeking to gather evidence for benefits and harms of common interventions for shoulder pain. This series of reviews forms the update of an earlier Cochrane review of physical therapy for shoulder disorders (Green 2003). Since the time of our original review, many new clinical trials studying a diverse range of interventions have been performed. To improve usability of this series, we have subdivided the reviews by type of shoulder disorder, as patients within different diagnostic groupings may respond differently to interventions. This review focuses on manual therapies and exercise alone or in combination for adhesive capsulitis (frozen shoulder). Separate reviews of (1) electrotherapy modalities for adhesive capsulitis, (2) manual therapy, exercise and taping for rotator cuff disorders and (3) electrotherapy modalities for rotator cuff disorders are currently under way.

Adhesive capsulitis (also termed frozen shoulder, painful stiff shoulder or periarthritis) is a common condition characterised by spontaneous onset of pain, progressive restriction of movement of the shoulder and disability that restricts activities of daily living, work and leisure (Codman 1934; Neviaser 1945; Reeves 1975). Lack of specific diagnostic criteria for the condition has been acknowledged. Reviews of the diagnostic criteria used in clinical trials of adhesive capsulitis have found that all trialists reported that restricted movement must be present, but the amount of restriction, whether the restriction had to be active or passive or both and the direction of restriction were inconsistently defined (Green 1998; Schellingerhout 2008). The cumulative incidence of adhesive capsulitis has been reported as 2.4 per 1000 people per year (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.9 to 2.9) based on presentations to Dutch general practice (van der Windt 1995). Adhesive capsulitis has been reported to affect slightly more women than men (Tekavec 2012; Walker 2004). Most studies indicate that it is a self‐limiting condition lasting up to two to three years (Reeves 1975), although some people may have residual clinically detectable restriction of movement and disability beyond this time point (Binder 1984; Hazelman 1972). The largest case series (269 shoulders in 223 patients) found that at a mean follow‐up of 4.4 years (range two to 20 years), 41% had ongoing symptoms (Hand 2008).

Description of the intervention

Manual therapy and exercise, usually delivered together as components of a physical therapy intervention, are commonly used interventions for adhesive capsulitis (Hanchard 2011a). Manual therapy includes any clinician‐applied movement of the joints and other structures, for example, mobilisation (of which several types exist, e.g. Kaltenborn 1976; Maitland 1977) or manipulation. Exercise includes any purposeful movement of a joint, muscle contraction or prescribed activity. It may be performed under the supervision of a clinician or unsupervised at home. Examples include range of motion, stretching, strengthening, pendulum, pulley, "shoulder wheel" and "wall climbing" exercises. Manual therapy and exercises are delivered by various clinicians, including physiotherapists, physical therapists, chiropractors and osteopaths. The aims of both types of interventions are to relieve pain, promote healing, reduce muscle spasms, increase joint range, strengthen weakened muscles and improve biomechanics and function (Hanchard 2011b). In practice, patients with adhesive capsulitis seldom receive a single intervention in isolation (i.e. manual therapy or exercise alone). In addition, electrotherapy modalities (e.g. therapeutic ultrasound, laser therapy) may be delivered along with manual therapy and exercise as part of a physical therapy intervention (Hanchard 2011a).

How the intervention might work

Although previous systematic reviews have found limited evidence for the benefit of manual therapy and exercise when used in isolation to treat adhesive capsulitis (Green 1998; Green 2003), these interventions are hypothesised to produce a number of beneficial physiological and biomechanical effects. Restricted movement of the shoulder for an extended period of time can result in loss of strength, proprioception and coordination of the shoulder complex (Ballantyne 1993), along with contraction of muscles, tendons and ligaments around the shoulder (Mao 1997). Mobilisation is employed to reduce pain by stimulating peripheral mechanoreceptors and inhibiting nociceptors, and to increase joint mobility by enhancing exchange between synovial fluid and cartilage matrix (Frank 1984; Mangus 2002; Vermeulen 2006). Exercises aim to improve range of motion and muscle function by restoring shoulder mobility, proprioception and stability (Nicholson 1985).

Why it is important to do this review

The previous version of this review (Green 2003), which included four trials investigating the benefits and harms of manual therapy or exercise (or both) for adhesive capsulitis (Bulgen 1984; Dacre 1989; Nicholson 1985; van der Windt 1998), concluded that little evidence was available to support or refute the benefits or harms of these interventions for adhesive capsulitis. Other recently published systematic reviews of interventions for adhesive capsulitis (Blanchard 2010; Favejee 2011; Hanchard 2011b; Maund 2012) have identified several new trials. Therefore, this review of manual therapy and exercise for adhesive capsulitis needs to be updated.

Objectives

To synthesise available evidence regarding the benefits and harms of manual therapy and exercise, alone or in combination, for the treatment of patients with adhesive capsulitis.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of any design (e.g. parallel, cross‐over, factorial) and controlled clinical trials using a quasi‐randomised method of allocation, such as by alternation or date of birth. Reports of trials were eligible regardless of the language or date of publication.

Types of participants

We included trials that enrolled adults (> 16 years of age) with adhesive capsulitis (as defined by trialists) for any duration. We included trials consisting of participants with various soft tissue disorders only if the results for participants with adhesive capsulitis were presented separately, or if 90% or more of participants in the trial had adhesive capsulitis. We excluded trials that enrolled participants with a history of significant trauma or systemic inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, hemiplegic shoulder and pain in the shoulder region as part of a complex myofascial neck/shoulder/arm pain condition.

Types of interventions

We included trials comparing any manual therapy or exercise intervention versus no treatment, placebo, a different type of manual therapy or exercise or any other intervention. Eligible interventions included mobilisation, manipulation and supervised or home exercise. Exercises could be land‐based or water‐based but had to consist of tailored shoulder exercises rather than just general activity (e.g. swimming). Trials primarily evaluating the effects of electrotherapy modalities such as therapeutic ultrasound, low‐level laser therapy, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), pulsed electromagnetic field therapy, interferential current, phonophoresis, iontophoresis or continuous short‐wave diathermy were excluded and are included in a separate Cochrane review.

Types of outcome measures

We did not consider outcomes as part of the eligibility criteria.

Considerable variation has been noted in the outcome measures reported in clinical trials of interventions for pain. However, it is generally agreed that outcome measures of greatest importance to patients should be considered.

The Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials (IMMPACT) has published consensus recommendations for determining clinically important changes in outcome measures in clinical trials of interventions for chronic pain (Dworkin 2008). Reductions in pain intensity of ≥ 30% and ≥ 50% reflect moderate and substantial clinically important differences, respectively, and it is recommended that the proportion of participants who respond with these degrees of pain relief should be reported.

Continuous outcome measures in pain trials (such as mean change on a 100‐mm visual analogue scale (VAS)) may not follow a Gaussian distribution. Often, a bimodal distribution is seen instead, in which participants tend to report very good or very poor pain relief (Moore 2010). This creates difficulty in interpreting the meaning of average changes in continuous pain measures. For this reason, a dichotomous outcome measure (the proportion of participants reporting ≥ 30% pain relief) may be clinically relevant for trials of adhesive capsulitis.

The original review determined that no trials had included a dichotomous outcome for pain, in keeping with the recognition that it has been the practice in most trials of interventions for chronic pain to report continuous measures only. We therefore also included a continuous measure of overall pain.

A global rating of treatment success, such as the Patient Global Impression of Change scale (PGIC), which provides an outcome measure that integrates pain relief, changes in function and adverse events into a single, interpretable measure, is also recommended by IMMPACT and was included as a main outcome measure (Dworkin 2008).

Main outcomes

Participant‐reported pain relief of 30% or greater (a moderate clinically important difference).

Overall pain (mean or mean change measured by VAS, numerical or categorical rating scale).

Function. When trialists reported outcome data for more than one function scale, we extracted data on the scale that was highest on the following a priori defined list: (1) Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI); (2) Croft Shoulder Disability Questionnaire; (3) Constant Score; (4) Short Form (SF)‐36 Physical Component Score; (5) Health Assessment Questionnaire; and (6) any other function scale.

Global assessment of treatment success as defined by trialists (e.g. proportion of participants with significant overall improvement).

Active shoulder abduction (measured in degrees or other).

Quality of life as measured by generic measures (such as components of the SF‐36 or disease‐specific tools).

Number of participants experiencing any adverse events.

Other outcomes

Night pain measured by VAS, numerical or categorical rating scale.

Pain on motion measured by VAS, numerical or categorical rating scale.

Other measures of range of motion (ROM) (flexion, external rotation and internal rotation (measured in degrees or other, e.g. hand‐behind‐back distance in centimetres)). When trialists reported outcome data for both active and passive ROM measures, we extracted the data on active ROM only.

Work disability.

Requiring surgery (e.g. manipulation under anaesthesia, arthroscopy).

We extracted benefit outcome measures (e.g. overall pain or function) at the following time points.

Up to three weeks.

Longer than three weeks and up to six weeks (this was the main time point).

Longer than six weeks and up to six months.

Longer than six months.

If data were available in a trial at multiple time points within each of the above periods (e.g. at four, five and six weeks), we extracted only data at the latest possible time point of each period. We extracted adverse events reported at all time points.

We collated the main results of the review into summary of findings (SoF) tables, which provide key information on the quality of evidence and the magnitude and precision of the effects of interventions. We included the main outcomes (see above) in the SoF tables, with results at, or nearest, the main time point (six weeks) presented.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (to 2013, Issue 4), MEDLINE (January 1966 to May 2013), EMBASE (January 1980 to May 2013) and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) Plus (January 1937 to May 2013). The complete search strategies are presented in Appendix 1. Note that the search terms used included clinical terms relevant to rotator cuff disorders and electrotherapy interventions, as the current review and Cochrane reviews of (1) electrotherapy modalities for adhesive capsulitis, (2) manual therapy and exercise for rotator cuff disorders and (3) electrotherapy modalities for rotator cuff disorders were conducted simultaneously.

In May 2014, we reran the search of all four electronic bibliographic databases and screened the results for potentially eligible records, but we did not incorporate any studies identified in the updated search.

Searching other resources

We searched for ongoing trials and protocols of published trials in the clinical trials register that is maintained by the US National Institutes of Health (http://clinicaltrials.gov) and the Clinical Trial Register at the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform of the World Health Organization (http://www.who.int/ictrp/en/). We also reviewed the reference lists of included trials and of relevant review articles retrieved from the electronic searches to identify other potentially relevant trials.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (MJP and BM) independently selected trials for possible inclusion against a predetermined checklist of inclusion criteria (see Criteria for considering studies for this review). We screened titles and abstracts and initially categorised studies into the following groups.

Possibly relevant—trials that met the inclusion criteria and trials from which it was not possible to determine from their title or abstract whether they met the criteria.

Excluded—trials clearly not meeting the inclusion criteria.

If a title or abstract suggested that the trial was eligible for inclusion, or if we could not tell, we obtained a full‐text version of the article, and two review authors (MJP and BM) performed an independent assessment to determine whether it met the inclusion criteria. The review authors resolved discrepancies through discussion or through adjudication by a third review author (SG or RB).

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (MJP and SK, RJ or MC) independently extracted data using a standard data extraction form developed for this review. The review authors resolved discrepancies through discussion or adjudication by a third review author (SG or RB) until consensus was reached. We pilot‐tested the data extraction form and modified it as needed before use. In addition to items for assessing risk of bias and numerical outcome data, we recorded the following characteristics.

Trial characteristics, including type (e.g. parallel, cross‐over), country, source of funding and trial registration status (with registration number recorded if available).

Participant characteristics, including age, sex, duration of symptoms and inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Intervention characteristics, including type of manual therapy or exercise, duration of treatment and use of co‐interventions.

Outcomes reported, including the measurement instrument used and timing of outcome assessment.

One review author (MJP) compiled all comparisons and entered outcome data into Review Manager 5.2.

For a particular systematic review outcome, a multiplicity of results may be available in the trial reports (e.g. multiple scales, time points, analyses). To prevent selective inclusion of data based on the results (Page 2013), we used the following a priori defined decision rules to select data from trials.

When trialists reported both final values and change from baseline values for the same outcome, we extracted final values.

When trialists reported both unadjusted and adjusted values for the same outcome, we extracted unadjusted values.

When trialists reported data analysed on the basis of the intention‐to‐treat (ITT) sample and another sample (e.g. per‐protocol, as‐treated), we extracted ITT‐analysed data.

For cross‐over RCTs, we extracted data from the first period only.

When trials did not include a measure of overall pain but included one or more other measures of pain, for the purpose of combining data for the primary analysis of overall pain, we combined overall pain with other types of pain in the following hierarchy: unspecified pain; pain with activity; daytime pain.

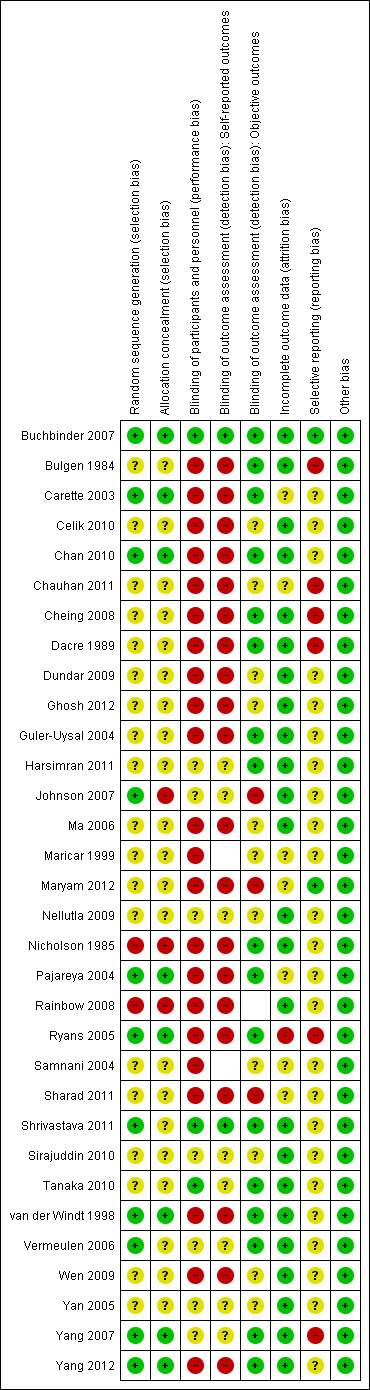

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (MJP and SK, RJ or MC) independently assessed the risk of bias in included trials using the tool of The Cochrane Collaboration for assessing risk of bias, as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a). The following domains were assessed.

Random sequence generation.

Allocation concealment.

Blinding of participants and personnel.

Blinding of outcome assessment (assessed separately for self‐reported and objectively assessed outcomes).

Incomplete outcome data.

Selective reporting.

Other sources of bias (specifically, baseline imbalance).

Each item was rated as at 'Low risk,' 'Unclear risk' or 'High risk' of bias. We resolved discrepancies through discussion or adjudication by a third review author (SG or RB).

Measures of treatment effect

We used the statistical software of The Cochrane Collaboration, Review Manager 5.2, to perform data analysis. We expressed dichotomous outcomes as risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and continuous outcomes as mean differences (MDs) with 95% CIs if different trials used the same measurement instrument to measure the same outcome. Alternatively, we analysed continuous outcomes using the standardised mean difference (SMD) when trials measured the same outcome but employed different measurement instruments. To enhance interpretability of dichotomous outcomes, risk differences and number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) or number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome (NNTH) were calculated. To enhance interpretability of continuous outcomes, pooled SMDs for overall pain and function were back‐transformed to an original SPADI (0 to 100) pain or disability score by multiplying SMDs and 95% CIs by a representative pooled standard deviation (SD) at baseline for one of the included trials.

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis was the participant. Two trials included a small number of participants with bilateral adhesive capsulitis. For these trials, we analysed data based on the number of participants, not the number of shoulders, to produce conservative estimates of effect.

Dealing with missing data

When required, we contacted trialists via email (twice, separated by three weeks) to retrieve missing information about trial design, outcome data or attrition rates, such as dropouts, losses to follow‐up and postrandomisation exclusions in the included trials. For continuous outcomes with no SD reported, we calculated SDs from standard errors (SEs), 95% CIs or P values. If no measures of variation were reported and SDs could not be calculated, we planned to impute SDs from other trials in the same meta‐analysis, using the median of other available SDs (Ebrahim 2013). When data were imputed or calculated (e.g. SDs calculated from SEs, 95% CIs or P values, or imputed from graphs or from SDs in other trials), we reported this in the Characteristics of included studies tables.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed clinical heterogeneity by determining whether characteristics of participants, interventions, outcome measures and timing of outcome measurement were similar across trials. We assessed statistical heterogeneity using the Chi2 statistic and the I2 statistic (Higgins 2002). We interpreted the I2 statistic by using the following as an approximate guide.

0% to 40% may not be important heterogeneity.

30% to 60% may represent moderate heterogeneity.

50% to 90% may represent substantial heterogeneity.

75% to 100% may represent considerable heterogeneity (Deeks 2011).

Assessment of reporting biases

To assess publication bias, we planned to generate funnel plots if at least 10 trials examining the same intervention comparison were included in the review and to comment on whether asymmetry in the funnel plot was due to publication bias or to methodological or clinical heterogeneity of the trials (Sterne 2011). To assess outcome reporting bias, we compared outcomes specified in trial protocols versus outcomes reported in corresponding trial publications; if trial protocols were unavailable, we compared outcomes reported in the methods and results sections of trial publications (Dwan 2011; Norris 2012). We generated an outcome reporting bias in trials (ORBIT) matrix (http://ctrc.liv.ac.uk/orbit/) using the ORBIT classification system (Kirkham 2010).

Data synthesis

For this review update, a large number of identified trials studied a diverse range of interventions. To define the most clinically important questions to be answered in the review, after data extraction was completed, one review author (MJP) sent the list of all possible trial comparisons to both of the original primary authors of this review (SG and RB). After reviewing the list of possible trial comparisons, both of these review authors discussed and drafted a list of clinically important review questions and categorised each trial comparison under the review question with which it fit best. This process was conducted iteratively until all trial comparisons were allocated to a single review question, and it was conducted without knowledge of the results of any outcomes. The following review questions were defined.

Is the combination of manual therapy and exercise (with or without electrotherapy) effective compared with placebo, no intervention or another active intervention (e.g. glucocorticoid injection, oral non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drug (NSAID), arthrographic joint distension)?

Is the combination of manual therapy and exercise (with or without electrotherapy) delivered in addition to another active intervention more effective than the other active intervention alone?

Is manual therapy (with or without electrotherapy) effective compared with placebo, no intervention or another active intervention?

Are supervised or home exercises (with or without electrotherapy) effective compared with placebo, no intervention or another active intervention?

Is one type of manual therapy or exercise (with or without electrotherapy) more effective than another (i.e. one type of manual therapy vs another type of manual therapy or one type of exercise vs another type of exercise)?

Is the combination of manual therapy and exercise (with or without electrotherapy) delivered in addition to another active intervention more effective than placebo or no treatment?

The first two of these were considered the main questions of the review, as these combination interventions are best reflective of clinical practice.

We combined results of trials with similar characteristics (participants, interventions, outcome measures and timing of outcome measurement) to provide estimates of benefits and harms. When we could not combine data, we summarised effect estimates and 95% CIs of each trial narratively. We combined results using a random‐effects meta‐analysis model based on the assumption that clinical and methodological heterogeneity was likely to exist and to have an impact on the results.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We did not undertake any subgroup analyses.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to perform a sensitivity analysis to investigate the robustness of the treatment effect (of main outcomes) to allocation concealment and participant blinding, by removing trials that reported inadequate or unclear allocation concealment and lack of participant blinding from the meta‐analysis, to see if this changed the overall treatment effect.

Summary of findings tables

We presented the results of the most important comparisons of the review in Summary of findings tables, which summarise the quality of evidence, the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined and the sum of available data on outcomes, as recommended by The Cochrane Collaboration (Schünemann 2011a). The Summary of findings tables include an overall grading of the evidence related to each of the main outcomes, using the GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation Working Group) approach (Schünemann 2011b).

In the Comments column of the Summary of findings table, we report the absolute per cent difference, the relative per cent change from baseline and the number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) (the NNTB is provided only when the outcome shows a statistically significant difference).

For dichotomous outcomes (pain relief ≥ 30%, global assessment, adverse events), the absolute risk difference was calculated using the risk difference statistic in RevMan, and the result expressed as a percentage; the relative per cent change was calculated as the risk ratio ‐1 and was expressed as a percentage. For continuous outcomes (overall pain, function, active shoulder abduction, quality of life), the absolute risk difference was calculated as the improvement in the intervention group minus the improvement in the control group, expressed in the original units (i.e. mean difference from RevMan divided by units in the original scale), expressed as a percentage. The relative per cent change is calculated as the absolute change (or mean difference) divided by the baseline mean of the control group, expressed as a percentage.

In addition to the absolute and relative magnitude of effect provided in the SoF table, for dichotomous outcomes the NNTB or the number needed to treat for an additional harmful effect (NNTH) was calculated from the control group event rate and the risk ratio using the Visual Rx NNT calculator (Cates 2004). For continuous outcomes of overall pain and function, the NNTB was calculated using Wells calculator software, which is available at the Cochrane Musculoskeletal Group (CMSG) editorial office (http://musculoskeletal.cochrane.org). We assumed a minimal clinically important difference (MCID) of 1.5 points on a 10‐point scale for pain, and of 10 points on a 100‐point scale for function or disability, for input into the calculator.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

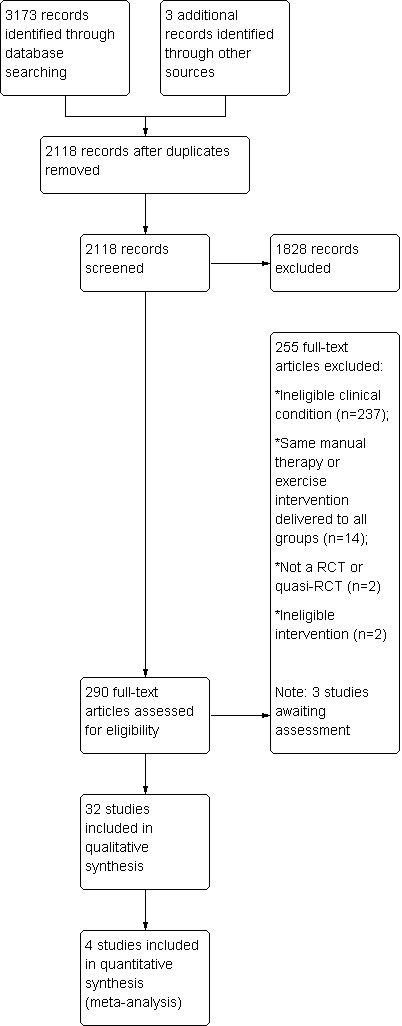

The search, which was conducted up to May 2013, yielded 3173 records across the four databases. Three additional records were identified by screening reference lists of previously published systematic reviews and included trials. After duplicates were removed, 2118 unique records remained. Of these, 290 were retrieved for full‐text screening on the basis of title and abstract. Thirty‐two trials were deemed eligible for inclusion (Buchbinder 2007; Bulgen 1984; Carette 2003; Celik 2010; Chan 2010; Chauhan 2011; Cheing 2008; Dacre 1989; Dundar 2009; Ghosh 2012; Guler‐Uysal 2004; Harsimran 2011; Johnson 2007; Ma 2006; Maricar 1999; Maryam 2012; Nellutla 2009; Nicholson 1985; Pajareya 2004; Rainbow 2008; Ryans 2005; Samnani 2004; Sharad 2011; Shrivastava 2011; Sirajuddin 2010; Tanaka 2010; van der Windt 1998; Vermeulen 2006; Wen 2009; Yan 2005; Yang 2007; Yang 2012). Two additional trials are available only as conference abstracts (Uddin 2012; Wies 2003); one is written in German and requires translation (Fink 2012). These three trials are awaiting classification (see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification table). Three ongoing trials were identified in clinical trials registries (see Characteristics of ongoing studies table). A flow diagram of the study selection process is presented in Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

The updated search in May 2014 yielded three studies deemed eligible for inclusion (Doner 2013; Ibrahim 2013; Russell 2014). These studies did not address the two main questions of the review (which focus on the effects of the combination of manual therapy and exercise) so were not incorporated into the review, but they are listed in the Characteristics of studies awaiting classification table. We will include these studies in a future update of the review.

Included studies

A full description of all included trials is provided in the Characteristics of included studies table. We contacted authors of 26 trials to retrieve (1) information about study design, participants, interventions and outcomes of the trial, (2) information required to complete the risk of bias assessments or (3) missing data for unreported or partially reported outcomes. We received replies from seven trialists (Carette 2003; Chan 2010; Maryam 2012; Pajareya 2004; Ryans 2005Yang 2007; Yang 2012).

Design

All trials except two were described as RCTs (Nicholson 1985 and Rainbow 2008 used a quasi‐random method of allocation). All trials except one used a parallel‐group design (Yang 2007 used a multiple‐treatment trial design, which involves the application of two or more treatments for a single participant and was used to assess differences among three interventions in two groups of participants). Twenty‐one trials included two intervention arms (Buchbinder 2007; Celik 2010; Chan 2010; Chauhan 2011; Dundar 2009; Guler‐Uysal 2004; Harsimran 2011; Johnson 2007; Maricar 1999; Nellutla 2009; Nicholson 1985; Pajareya 2004; Rainbow 2008; Samnani 2004; Sharad 2011; Shrivastava 2011; van der Windt 1998; Vermeulen 2006; Wen 2009; Yan 2005; Yang 2012), eight included three arms (Cheing 2008; Dacre 1989; Ghosh 2012; Ma 2006; Maryam 2012; Sirajuddin 2010; Tanaka 2010; Yang 2007) and three included four arms (Bulgen 1984; Carette 2003; Ryans 2005).

Participants

A total of 1836 participants were included in the 32 trials, and the number of participants per trial ranged from eight to 156. The median of the mean age of participants was 55 years, and the median of the mean duration of symptoms was six months. Fifty‐four per cent of participants were female. Diagnostic criteria for (or definitions of) adhesive capsulitis varied with regards to type, amount and direction of shoulder restriction, ranging from undefined (e.g. Samnani 2004) to very specific (e.g. ≥ 50% loss of passive movement of the shoulder joint relative to the non‐affected side, in one or more of three movement directions (i.e. abduction in the frontal plane, forward flexion or external rotation in 0° of abduction)) (Vermeulen 2006). Trials were conducted in India (N = 8); UK (N = 4); Turkey, USA and Taiwan (N = 3 each); China and The Netherlands (N = 2); and Australia, Canada, Hong Kong, Iran, Japan, Singapore and Thailand (N = 1 each).

Interventions

A detailed description of the interventions delivered in each trial is summarised in the Characteristics of included studies table. A summary of the manual therapy or exercise intervention components tested in each trial is presented in Table 7. The types of manual therapy and exercise delivered were very heterogeneous across trials; Maitland's mobilisation techniques were the most common type of manual therapy, and Codman's pendulum exercises, active and passive ROM exercises, pulley exercises and shoulder wheel exercises were the most common types of exercise. The median duration of manual therapy or exercise interventions was four weeks (range one to 18), with a median of three treatment sessions delivered per week (range one to seven) and a median of 12 treatment sessions provided in total across the treatment period (range five to 84).

1. Characteristics of manual therapy and exercise interventions.

| Study ID | Manual therapy component(s) | Exercise component(s) | Duration of session (minutes) | No. sessions (per week) | No. weeks treatment | Total no. sessions |

| Buchbinder 2007 | Both passive and self‐executed muscle stretching techniques to stretch muscles passing over the glenohumeral joint; cervical and thoracic spine mobilization, glenohumeral joint passive accessory glides; glenohumeral joint passive physiologic mobilization including rotation. | Supervised: strength and coordination exercises for rotator cuff and scapular stabilizers; proprioceptive challenge | 30 | 2 per week in first 2 weeks; 1 per week in next 4 weeks | 6 | 8 |

| Bulgen 1984 | Maitland's mobilisations (no other details provided) | NA | NR | 3 | 6 | 18 |

| Carette 2003 | Mobilisation techniques (no other details provided) | Supervised: active ROM exercises (for acute adhesive capsulitis); active and auto‐assisted ROM exercises and isometric strengthening exercises (for chronic adhesive capsulitis) | 60 | 3 | 4 | 12 |

| Celik 2010 | NA | Supervised: scapulothoracic strengthening (serratus anterior, middle and lower trapezius, latissimus dorsi), upper trapezius stretching, and postural exercises. Home: active assistive ROM exercises (flexion, scapular elevation, and internal and external rotation exercises), posterior and inferior capsule stretching exercises, and self‐stick exercises |

Dependent on participants pain and muscle strength | 5 | 6 | 30 |

| Chan 2010 | Passive mobilisation (Grade A and Grade B mobilisation techniques, as advocated by Cyriax for treatment of stage II capsulitis) | Home: active and active‐assisted ROM exercises, capsular stretching exercise, postural correction and scapular stabilising work | 30 | 1 | 6 | 6 |

| Chauhan 2011 | Deep transverse friction massage of the two tendon supraspinatus and subscapularis as laid by Cyriax 1983, followed by inferior capsular stretching. Deep friction was given transverse to the fiber direction | Supervised: passive ROM exercises. Home: Not specified | 60 | 3 | 2 | 6 |

| Cheing 2008 | NA | Home: exercises in four directions: (i) forward flexion; (ii) external rotation; (iii) horizontal adduction; and (iv) internal rotation | NR | 2 to 3 | 4 | 10 |

| Dacre 1989 | Mobilisation (no other details provided) | NA | NR | 1 | 4 to 6 | 4 to 6 |

| Dundar 2009 | NA | Supervised: active stretching and pendulum exercises | 60 | 5 | 4 | 20 |

| Ghosh 2012 | NA | Supervised: active and passive shoulder mobilisation exercises plus shoulder wheel and pulley exercise | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Guler‐Uysal 2004 | Cyriax approach of deep friction massage and manipulation | NA | 60 | 3 | 2 | 6 |

| Harsimran 2011 | Either anterior or posterior glide mobilisation (Kaltenborn grade III) | NA | NR | 5 | 1 | 5 |

| Johnson 2007 | Either anterior or posterior glide mobilisation (Kaltenborn grade III) | NA | NR | 2 to 3 | 2 to 3 | 6 |

| Ma 2006 | Mobilisation (no other details provide) | Supervised: active exercises (not specified) | 20 | 5 | 4 | 20 |

| Maricar 1999 | Mobilisation of shoulder quadrant, shoulder capsular stretch, shoulder flexion, shoulder abduction, shoulder external and internal rotation using Maitland Grade III+ and IV | NA | NR | 1 | 8 | 8 |

| Maryam 2012 | NA | Supervised: active ROM exercises | NR | NR | NR | 10 |

| Nellutla 2009 | NA | Supervised: either proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (PNF) movement patterns for exercises or conventional free exercises, such as finger ladder exercises, Codman's pendulum exercises, and overhead shoulder pulley and shoulder wheel | NR | 5 | 3 | 15 |

| Nicholson 1985 | Passive mobilisation. Generally, in the early sessions gliding and distractive mobilisation techniques were performed with the joint near its neutral position, progressing in the later sessions to mobilisation towards the end of the range of motion | NA | NR | 2 to 3 | 4 | 8 to 12 |