Abstract

Little is understood about the unintended consequences of cannabis liberalization on children. Subsequently, this scoping review aimed to map and identify evidence related to acute cannabis intoxication in children. We searched three medical literature databases from inception until October 2019. We identified 4644 information sources and included 158 which were mapped by topic area relating to 1) public health implications and considerations; 2) clinical management; and 3) experiences and information needs of HCPs and families. Public health implications were addressed by 129 (82%) and often reported an increased incidence of acute pediatric cannabis intoxications. Clinical information was reported in 116 (73%) and included information on signs and symptoms (n = 106, 92%), clinical management processes (n = 60, 52%), and treatment recommendations (n = 42, 36%). Few sources addressed the experiences or information needs of either HCPs (n = 5, <1%) treating children for acute cannabis intoxication or families (n = 1, <1%) seeking care. Increasing incidence of acute cannabis intoxications concurrent with liberalization of cannabis legislation is clear, however, evidence around clinical management is limited. Additionally, further research exploring HCPs and families experiences and information needs around cannabis intoxication is warranted.

Keywords: cannabis, child health, incidence, emergency care, intoxication

Introduction

Cannabis is the most popular illicit drug worldwide and is now used for both medicinal and non-medical purposes (United Nations, 2019). Recent reports have estimated over 200 million people used cannabis in the past year (United Nations, 2019; Leduc-Pessah et al., 2019). The increase in users and recent liberalization of cannabis policy in some jurisdictions (Leung et al., 2019) has led to concerns over unintentional pediatric exposures (Richards et al., 2017a; Wang, 2017).

In the United States of America (USA), pediatric cannabis intoxications have increased in states where cannabis is decriminalized (Thomas et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2019). In France, where cannabis consumption is the highest in Europe (despite remaining illegal), pediatric cannabis intoxications have also increased over the last decade, including cases with severe symptoms (Chartier et al., 2020). Similar trends in unintentional acute cannabis intoxications and more severe cases are now appearing in Canada (Cohen et al., 2021).

In 2018, Canada became one of the first countries to legalize cannabis for both recreational and medical use (Grant and Belanger, 2017). After the Cannabis Act passed, commercialization of cannabis-infused food and beverages (“edibles”) was legalized. Unlike other cannabis products, edibles are inherently attractive to young children; they frequently resemble baked goods or other sweets and are marketed using similar branding to popular commercial treats (MacCoun and Mello, 2015). Recently, an increase in severe intoxications among infants, toddlers, and younger children from cannabis was primarily linked to exposure to edibles (e.g. cannabis cookies) (Cohen et al., 2021). Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC; primary psychoactive constituent) is dose-responsive based on body weight, thus these types of products developed for adult consumption may have severe effects in children (Heizer et al., 2018). Additionally, increased adult access to cannabis for both recreational and medical purposes may increase unintentional exposures for children through passive smoke and access to unfinished or unsecured product (Amirav et al., 2011; Wang, 2017).

While intentional use of cannabis by youth has been well studied (Gobbi et al., 2019; Camchong et al., 2017), unintentional pediatric exposures and/or acute cannabis intoxications are not as well understood (Richards et al., 2017a). With an increase in emergency department visits for acute pediatric cannabis intoxication on the horizon (Wang et al., 2018), it is important to understand what current evidence is available on this topic to support informed decision making by policymakers and clinicians. Identifying gaps in the current evidence base will guide future investigations and enable development of knowledge translation tools to help healthcare providers (HCPs) and families navigate the changing cannabis landscape. Lack of knowledge syntheses and recent proliferation of literature on this topic make it an excellent candidate for a scoping review.

Aim

We conducted a scoping review of the available evidence on public health implications, clinical management, and experiences and information needs of HCPs and families related to acute cannabis intoxication in children. To this end, we identified and mapped available literature around:

(1) Public health impacts: What is known about the epidemiology (e.g. incidence, risk factors, etc.), population-level impacts, and prevention strategies?

(2) Clinical characteristics and management: How do children and adolescents present for care during an episode of acute cannabis intoxication and how are these cases managed?

(3) Experiences and information needs:

(a) What are the experiences and information needs of HCPs related to managing acute cannabis intoxication in children and adolescents?

(b) What are the experiences and information needs of parents and families (i.e., caregivers) around acute cannabis intoxication in children and adolescents?

Methods

This scoping review is reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guideline extension for Scoping Reviews (Tricco et al., 2018). The protocol for this review was developed a priori and archived in the Open Science Framework (OSF) on 8 November 2019 (https://osf.io/pbm6t/?view_only=2a9bbaa4d2894438871438c8be7e85e1) as no registry for scoping reviews exists. Protocol deviations are described and justified in the OSF archive. Throughout, we refer to identified search records as ‘information sources’.

Searching

A medical research librarian systematically searched the following databases: Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval Online System (MEDLINE), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Psychological Information Database, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global, and the Cochrane Library from inception to 29 October 2019 using combined subject headings and keywords for “marijuana,” “cannabis,” “intoxication” or “poisoning,” “caregivers,” “information needs (Supplementary Material 1).

To supplement the database searches (Haddaway et al., 2015), Google Scholar was iteratively searched on 25 October 2019 using one term from each of three concept pairs of related search terms per search: “cannabis” or “marijuana”; “intoxication” or “poisoning”; “children” or “caregiver information”. The first 10 pages of results were screened and a subsequent search was carried out, replacing one term in one of the concept pairs for the other term. Searches were conducted, screened and modified until all combinations of terms had been searched and modified. Finally, references and citations of all included information sources were hand-searched for relevant items not already identified. Hand searching concluded in March 2020.

Eligibility and screening

We included information sources discussing any of our four key questions about cannabis intoxication in children and adolescents. Information sources not reporting a mean age were included if either >80% of the study sample was <18 years old, or if information on pediatric patients was reported separately from adults. Only information sources in English or French were eligible. We did not restrict eligibility based on country or publication type/status (details available in Supplementary Material 2).

We defined cannabis intoxication as an acute medical event. Information sources solely about cannabis use in adolescents were excluded, as adolescent cannabis use and substance use disorder are well studied and previously synthesized (Das et al., 2016). Additionally, as evidence around therapeutic/medical use of cannabis in pediatric patients has already been synthesized (Wong and Wilens, 2017), information sources about therapeutic cannabis use were also excluded.

Experiences and information needs were defined based on previous reviews (Gates et al., 2018a, 2018b, 2019). Experiences are individualized circumstances or events that can be internal (e.g. emotions, sensations, etc.) and/or external (e.g. actions taken, environmental circumstances, etc.). Information needs were operationalized as self-reports of type, quantity, timing, and delivery mode of information desired by either HCPs or parents/families.

All search results were exported to EndNote reference management software (v. X9, Thomson Reuters, Toronto, Canada) and de-duplicated. Two reviewers independently reviewed unique titles and abstracts, and attempts were made to retrieve the full-texts of records marked as either ‘include’ or ‘unsure’ by at least one reviewer. Retrieved information sources were reviewed by one reviewer for their adherence to the a priori inclusion criteria. Information sources excluded by the first reviewer were screened by a second reviewer to ensure that no relevant information sources were missed.

Data abstraction, charting and collation

Data were extracted into a purpose-built Microsoft Excel form. Two reviewers independently verified 10% (n = 16) of records, and variables with >10% disagreement were fully verified. Extracted data included: information source characteristics, population characteristics, exposure details, clinical aspects of acute intoxication, prevention/intervention strategies, HCPs experiences and information needs, and parent/family experiences and information needs (Supplementary Material 3).

Information sources not intended for use by the general public were categorized as “academic”; these included doctoral theses, reports prepared for government or non-profit agencies, and all publications in academic journals. Independent of target audience, information sources were also clustered into six types: primary sources (i.e. primary research); knowledge summaries (e.g. systematic and non-systematic reviews); institutional reports (i.e. reports commissioned or prepared by governments, public health agencies, or non-profit organizations); editorials (e.g. letters and commentaries); media for HCPs; and media for public audiences. Since the nature of scoping reviews is to examine the breadth of literature on a particular topic, rather than conduct a quantitative synthesis, most variables were extracted as “reported” if they were discussed in an information source, regardless of whether the information source actively collected data on that topic. The exception to this strategy was symptom reporting in primary information sources, which were only marked as “reported” if they were actively collected by study authors.

Included information sources were categorized based on whether they addressed each of the four review questions, which were not mutually exclusive. If information was not explicitly stated, it was recorded as “not reported”, with few exceptions (e.g. a study reporting all patients were discharged was considered to have reported on fatality). We narratively summarized quantity and coverage of information within each of our four review questions to provide an overview of the main findings, while highlighting gaps in the evidence.

Information sources were categorized based on four key elements (population, design, audience, outcomes), which were used to generate graphic visualizations. Geographic maps illustrating the number of information sources addressing each review question by country were created using EviAtlas (Haddaway et al., 2019). Additional visualizations in the form of heat maps were generated using EviAtlas.

Two word clouds were generated based on word frequency using either 1) the stated or inferred objectives of academic information sources or 2) the full text of public-facing information sources. Word clouds were generated in NVivo Qualitative Data Analysis Software version 12 (QSR International, Melbourne, Australia).

Results

Search results

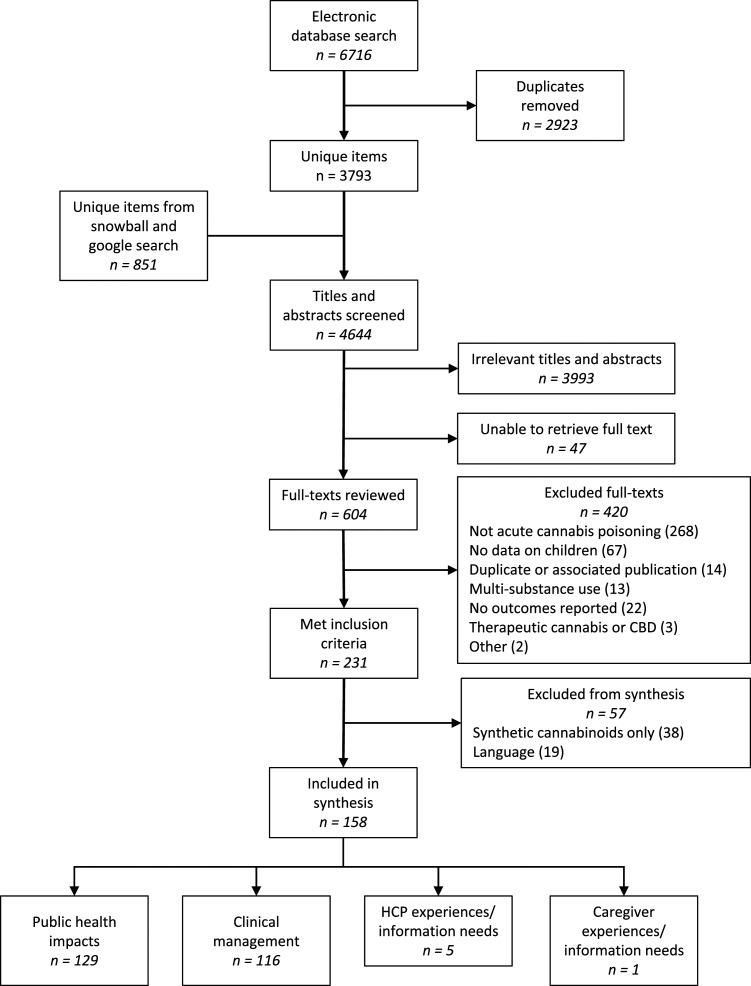

As presented in Figure 1 (PRISMA Flow Chart), our search identified 4644 unique items; 158 information sources met the inclusion criteria and were mapped and synthesized (Supplementary Material 3).

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow diagram for a scoping review of acute pediatric cannabis intoxication.

Characteristics of included information sources

Over 60% (n = 100) of identified information sources were from the last 5 years (median publication year: 2017). Information sources came mainly from the USA (n = 90, 57%), followed by Canada (n = 21, 13%) and France (n = 20, 13%). While 92 (58%) information sources reported children’s sex, only seven (4%) mentioned race or ethnicity. Most information sources (n = 123, 78%) addressed information relevant to infants and toddlers (<4 years old, or “young children”); while children aged 4–12 years and adolescents (12–∼20 years) were addressed in 64% (n = 101) and 41% (n = 64) of information sources, respectively.

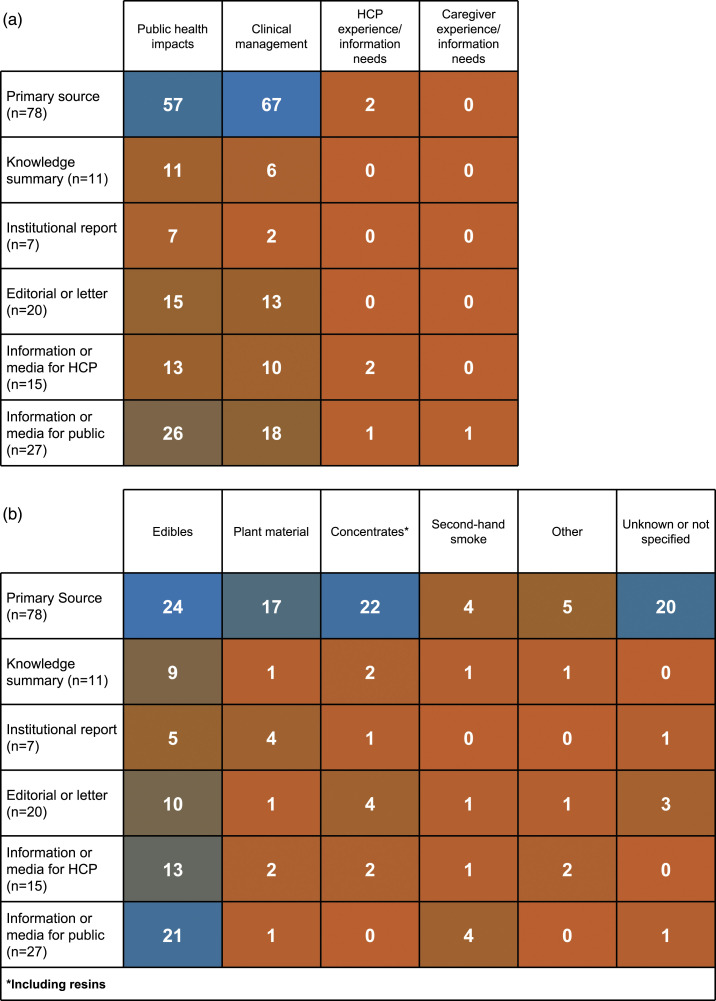

Table 1 describes information source type, population, care setting, and reporting of exposure details by our four review questions. Most information sources provided information on public health impacts (n = 129, 82%) and/or clinical information (n = 116, 73%). Few sources addressed either HCPs (n = 5, 3%) or parents/families (n = 1, 1%) experiences or information needs. Primary information sources were most common for both public health impacts (n = 57, 44%) and clinical information (n = 67, 58%). Additionally, case reports/series were the most common study design (n = 37, 29% and n = 52, 45%, respectively) for primary information sources reporting on public health impacts or clinical information.

Table 1.

Characteristics of information sources included in a scoping review of acute pediatric cannabis intoxications.

| Total | Public health impacts | Clinical information | HCP experiences and information needs | Caregiver experiences and information needs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 158 | n = 129 | n = 116 | n = 5 | n = 1 | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Source type | |||||

| Primary source | 78 (49) | 57 (44) | 67 (58) | 2 (40) | 0 (0) |

| Case report/series | 56 (35) | 37 (29) | 52 (45) | 1 (20) | 0 (0) |

| Retrospective cohort | 6 (4) | 6 (5) | 5 (4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Trend studies | 5 (3) | 5 (4) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Interrupted time series | 4 (3) | 4 (3) | 4 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Before/after | 4 (3) | 4 (3) | 3 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Other | 3 (2) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (20) | 0 (0) |

| Knowledge summary | 11 (7) | 11 (9) | 6 (5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Institutional report | 7 (4) | 7 (5) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Editorial | 20 (13) | 15 (12) | 13 (11) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Information/media for HCPs | 15 (9) | 13 (10) | 10 (9) | 2 (40) | 0 (0) |

| Information/media for the public | 27 (17) | 26 (20) | 18 (16) | 1 (20) | 1 (100) |

| Study population | |||||

| Infants and toddlers (<4 y) | 123 (78) | 100 (78) | 96 (78) | 2 (40) | 0 (0) |

| Children (4 to <12 y) | 101 (64) | 92 (71) | 64 (55) | 5 (100) | 0 (0) |

| Adolescents 12 to ∼20 y) | 64 (41) | 58 (45) | 35 (30) | 1 (20) | 1 (100) |

| Care setting | |||||

| Emergency department | 66 (42) | 49 (38) | 66 (57) | 1 (20) | 1 (100) |

| Hospital | 69 (44) | 51 (40) | 69 (59) | 2 (40) | 0 (0) |

| Poison control center | 16 (10) | 15 (12) | 13 (11) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Other | 22 (14) | 16 (12) | 22 (19) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Not reported | 14 (9) | 13 (10) | 6 (5) | 1 (20) | 0 (0) |

| Exposure details | |||||

| Form of cannabis | 119 (75) | 95 (74) | 87 (75) | 5 (100) | 0 (0) |

| Intent | 138 (87) | 117 (91) | 101 (87) | 4 (80) | 1 (100) |

| Route of exposure | 108 (68) | 84 (65) | 90 (78) | 5 (100) | 1 (100) |

| Source of cannabis | 55 (35) | 37 (29) | 53 (46) | 3 (60) | 0 (0) |

| Location of exposure | 66 (42) | 51 (40) | 60 (52) | 2 (40) | 1 (100) |

Exposure details were variably reported; intent (e.g. intentional, unintentional, etc.) was reported most often, followed by form of cannabis (Table 1). Less than half of information sources addressed source of cannabis or location of exposure. Route of exposure, source of cannabis, and location of exposure were more frequently discussed in information sources reporting on clinical information than in sources discussing public health impacts (Table 1). Edibles were universally the most commonly discussed form of cannabis (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Heat map of information source by cannabis type.

Themes present in word clouds generated from academic or public-facing information sources included cannabis/marijuana and children (Supplementary Material 4); however, objectives of academic sources primarily related to clinical context while public media/education sources highlighted themes relating to safety and prevention.

Public health impacts

One hundred 29 information sources (82%) reported on public health impacts, including 57 (44%) primary information sources (n = 37, 29% case reports) and 11 (9%) knowledge summaries (Table 1). Incidence was commonly reported (n = 41, 26%; Table 2), often in primary sources (n = 24, 31%) of which 16 (67%) reported incidence of acute pediatric cannabis intoxications increasing over time (Cao et al., 2016; Claudet et al., 2017; Thomas et al., 2018; Noel et al., 2019; Onders et al., 2016; Spadari et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2013, 2016, 2018, 2019; Whitehill et al., 2019; Graham et al., 2020; Zhu and Wu, 2016; Close, 2019). Discussion of long-term sequelae (including lack thereof) was infrequent (n = 7, 4%).

Table 2.

Reported outcomes related to the scoping review’s four questions by information source type.

| Variable | Total N=158 | Primary source n =78 | Knowledge summary n =11 | Institutional report n =7 | Editorial or letter n =20 | Information or media for HCPs n =15 | Information or media for public n =27 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Public health impacts | |||||||

| Reports incidence | 41 (26) | 24 (31) | 3 (27) | 4 (57) | 5 (25) | 4 (27) | 5 (19) |

| Risk factors (identified or potential) | 92 (58) | 34 (44) | 9 (82) | 4 (57) | 14 (70) | 11 (73) | 20 (74) |

| Prevention strategies (identified or potential) | 83 (53) | 24 (31) | 8 (73) | 6 (86) | 12 (60) | 8 (53) | 25 (93) |

| Reports of long-term sequelae | 7 (4) | 5 (6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (7) |

| Clinical characteristics | |||||||

| Signs and symptoms | 107 (68) | 61 (78) | 6 (55) | 2 (29) | 13 (65) | 10 (67) | 15 (56) |

| Toxicology testing reported | 70 (44) | 53 (68) | 2 (18) | 0 (0) | 8 (40) | 6 (40) | 1 (4) |

| Clinical management described | 60 (38) | 47 (60) | 1 (9) | 0 (0) | 7 (35) | 4 (27) | 1 (4) |

| No or supportive care* | 47 (30) | 36 (46) | 1 (9) | 0 (0) | 6 (30) | 4 (27) | 0 (0) |

| Pharmacological intervention** | 35 (22) | 31 (40) | 1 (9) | 0 (0) | 2 (10) | 1 (7) | 0 (0) |

| Mechanical intervention*** | 25 (16) | 21 (27) | 1 (9) | 0 (0) | 2 (10) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) |

| Makes treatment recommendations | 42 (27) | 25 (32) | 3 (27) | 1 (14) | 4 (20) | 8 (53) | 1 (4) |

| Reports involvement of child protective services | 38 (24) | 30 (38) | 1 (9) | 0 (0) | 3 (15) | 4 (27) | 0 (0) |

| Experiences and information needs of health care providers | |||||||

| Experiences | 4 (3) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (13) | 1 (4) |

| Information needs | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) |

| Experiences and information needs of parents/families | |||||||

| Experiences | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) |

| Information needs | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

* included observation, hydration maintenance, and symptomatic management with over-the-counter medications (e.g., acetaminophen).** included use of controlled pharmacologic agents. *** included gastric lavage, intubation, and other physical interventions.

Potential risk factors were mentioned frequently (n = 92, 58%), including in 34 (44%) primary information sources (Table 2). Eight (24%) primary sources evaluated associations between risk factors and acute cannabis intoxications, seven of which (all in the USA) reported a positive association between acute cannabis intoxications and decriminalization (Cao et al., 2016; Thomas et al., 2018, 2019; Wang et al., 2013, 2014, 2016, 2019; Onders et al., 2016). Eighty-three (53%) information sources, including 24 (31%) primary sources (n=8, 33% case reports/series), mentioned prevention strategies; none evaluated their effectiveness.

Clinical information

Overall, 116 (73%) information sources discussed clinical aspects of acute pediatric cannabis intoxication. Of primary sources reporting on clinical information, 37 (65%) were case series/reports (Table 1). Clinical aspects discussed included signs and symptoms (n = 107, 92%), use of toxicology screening (n = 70, 60%), type of clinical management (e.g. supportive care, mechanical ventilation; n = 60, 52%), and treatment recommendations (n = 42, 36%).

Table 2 summarizes clinical information reported by information source type. One knowledge synthesis (9%) and 47 (60%) primary sources (n = 38, 81% case reports/series) reported on clinical management. Several information sources remarked on the lack of an effective antidote for acute cannabis intoxication, (Levene et al., 2019; Wong and Baum, 2019; Bonkowsky et al., 2005; Nguyen and Cho, 2016; Thomas and Mazor, 2017; Thomas et al., 2017) but no comparative studies that evaluated the effectiveness of interventions for acute cannabis intoxication were reported. Despite this, 42 (27%) information sources made specific treatment recommendations for patients with acute cannabis intoxication, including 25 (32%) primary sources (n=23, 92% case reports/series).

Generally, observation, supportive care and symptom-specific treatments were the most commonly recommended clinical management strategies (Richards et al., 2017a). Reported pharmacotherapy treatment included: promethazine, atropine, bicarbonate, ipecac, diazepam, naloxone, physostigmine, flumazenil, dopamine, lorazepam, midazolam, dexmedetomidine and antibiotics. Information sources were divided on the usefulness of gastric lavage and activated charcoal, with some sources recommending their use (Shukla and Moore, 2004; Lavi et al., 2016; Miningou, 2014) and others recommending against them (Wang, 2019; Levene et al., 2019; Wong and Baum, 2019). Dexmedetomidine was used to treat intermittent agitation in a lethargic toddler with acute pediatric cannabis intoxication who had failed to tolerate a benzodiazepine bolus (Cipriani et al., 2015). Flumazenil successfully reversed cannabis intoxication-related coma in one case (Rubio et al., 1993), although it was unsuccessful in another (Carstairs et al., 2011). Despite these conflicting reports, several information sources recommended flumazenil as a potential treatment for coma due to cannabis intoxication (Molly et al., 2012; Miningou, 2014; Lavi et al., 2016). Involvement of child protective services was recommended by 38 (24%) sources (Table 2).

Information sources presenting clinical information frequently mentioned the non-specific nature of acute cannabis intoxication symptoms and importance of an accurate patient history and/or toxicological testing to prevent unnecessary and potentially invasive tests and treatments (Bashqoy et al., 2019; Nguyen and Cho, 2016; Appelboam and Oades, 2006; Bonkowsky et al., 2005; de Sonnaville-de Roy van Zuidewijn and Schilte, 1989; Shukla and Moore, 2004; Wang et al., 2013; Blackstone and Callahan, 2008; Wong and Baum, 2019; Ragab et al., 2014; Murti, 2017; Pires et al., 2018; Forman and Havranek, 2018; Morgan and Abernethy, 2019; Rochman, 2013).

Clinician experiences and information needs

Experiences and information needs of HCPs were reported in five (<1%) information sources (two primary sources, two information/media for HCPs sources, and one information/media for the public source). After participating in a medical simulation curriculum for acute pediatric cannabis intoxication, pediatric emergency medicine trainees reported increased confidence in identifying and managing THC exposures in pediatric patients (Burns et al., 2018). A medical education article examined the ethics around reporting a caregiver to child protective services (CPS) for providing their child marijuana edibles for therapeutic reasons without consulting a medical professional (Hines et al., 2018). Emergency medicine nurses participating in focus groups about perceived changes in workload due to cannabis legalization were concerned about spikes in pediatric cannabis intoxication cases, which they attributed to edibles (Wolf et al., 2020). The nurses also felt that public education campaigns around cannabis safety were inadequate (Wolf et al., 2020). Clinicians in France (where cannabis remains illegal) reported they rarely saw cases of pediatric cannabis intoxication, and many said they did not know much about testing for cannabis exposure or what type of tests to run for a child with cannabis intoxication (Hautin, 2017). Lastly, in a New York Times interview, an emergency physician from Colorado described their experience treating pediatric cases of acute cannabis intoxication including the perceived unpreparedness of their department and the dramatic increase in cases after legalization (Hoffman and Habibi, 2016). The physician also observed that caregivers were more willing to admit to accidental cannabis exposures in their children post-legalization, making it easier to treat those patients (Hoffman and Habibi, 2016).

Parents’ and families’ experiences and information needs

One (<1%) information source, a CBS News article, described a caregiver experience with acute cannabis intoxication. The caregiver described the aftermath of their teenaged son smoking cannabis at a party, which led the family to seek emergency care and ultimately the son’s death by suicide a few weeks later (Maas, 2015). No information sources addressed caregiver information needs regarding acute cannabis intoxication in children.

Discussion

We conducted a scoping review to map the available evidence around several facets of acute cannabis intoxication in children. The identification of a large number of relevant information sources, as well as several knowledge gaps suggest our aim was achieved.

The increase in cannabis intoxication events associated with liberalized cannabis regulations creates a need to understand its occurrence, prevention, and clinical management, and how to effectively relay that information to stakeholders. Despite an explosion in the last 5 years in academic and lay-public information sources addressing acute pediatric cannabis intoxication, this scoping review identified a lack of peer-reviewed scientific evidence to support clinical practice and policy-making.

Breadth of information sources

While academic interest in this topic is growing, (Canadian Pediatric Society, 2020) this review identified three times more narrative reviews, editorials, letters, and commentaries than publications of primary research on pediatric acute cannabis intoxication; scientific research in this arena may still be in its infancy due to the relatively recent legalization of cannabis (Richards et al., 2017a). With a rise in documented cases of cannabis intoxication in young children (Whitehill et al., 2019; Myran et al., 2022), awareness and primary research about this topic will likely also increase.

Lack of information sources describing clinician and parent/family experiences and information needs is noteworthy. The contrasting word clouds reflect the differing information needs of clinicians and the public. To effectively tailor resources to the needs of clinicians and families, further exploration of their experiences and information needs around the management of cannabis intoxication is warranted (Zarider et al., 2015).

Clinical management and guidance

The effectiveness of potential pharmacologic treatment options suggested in the literature (e.g. benzodiazepines, dexmedetomidine, flumazenil, activated charcoal) (Richards et al., 2017a) have not been rigorously evaluated. From this review, it appears current practice for management of acute pediatric cannabis intoxication is based on case reports, non-interventional observational studies, and clinical gestalt. Improving guidance for clinical management of pediatric acute cannabis intoxication patients may reduce health resource use (e.g. unnecessary diagnostic testing), as well as unnecessary harms (i.e. distress, pain, radiation exposure from diagnostic imaging) (Zarider et al., 2015). Multiple information sources indicated that in the absence of an accurate medical history, nonspecific symptoms of cannabis intoxication led to unnecessary and invasive tests and procedures (e.g. computed tomography scans, intubation, and lumbar puncture) that could have been avoided if an accurate medical history had been available. Similarly, information sources frequently suggested that – due to social or legal consequences – parents/families may be unwilling to report potential exposure, knowledge of which may influence clinical management decisions.

Reasons why parents/families choose to report or withhold information about a child’s known or suspected cannabis exposure have not been explored. Caregivers in jurisdictions where cannabis is legal may be more comfortable admitting that their child accessed cannabis. However, several information sources in this review conceptualized cannabis intoxication as child abuse, with calls for CPS involvement (Pelissier et al., 2014), even in jurisdictions where it had been legalized (Thomas et al., 2018; Murti, 2017; Bergeron et al., 2017; Friedman et al., 2017; Heard et al., 2017) and without discussion of broader implications and potential harms of CPS involvement. (Hines et al., 2018) Given the documented history of racism and overrepresentation of Black and Indigenous families in CPS systems in North America (Denison et al., 2014; Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2016) and persistent racism in health care (Mahabir et al., 2021), blanket recommendations for CPS involvement in all cases of cannabis intoxication may impact families decisions to seek care for their children in the case of acute cannabis intoxication (Pelissier et al., 2014). However, this concern is impossible to evaluate in the current literature because of the very small number of information sources in this review that reported race or ethnicity.

Public health messaging, and surveillance

Cannabis policy, including harm prevention, has largely been based on evidence from the tobacco and alcohol industries (Caulkins and Kilborn, 2019) and expert-opinion recommendations (Amirshahi et al., 2019). We did not identify any primary research studies or knowledge syntheses that evaluated strategies to prevent acute pediatric cannabis intoxications. This brings up two important considerations: first, prevention strategies implemented for acute cannabis intoxication are not being evaluated; and second, due to various routes of consumption and ability of individuals to produce cannabis products at home, cannabis policy based on alcohol and tobacco may not be effective (Kalant, 2016). Cannabis edibles can be more easily prepared at home than alcohol or tobacco products and may pose increased risk for cannabis intoxication due to questionable THC dosing (Wang, 2019). Similarly, retail edible products often contain multiple doses of THC in one usual serving of food (e.g. one chocolate bar) (Barrus et al., 2016). Evaluations of prevention strategies currently in place may highlight target areas for future prevention strategies.

One issue highlighted by this review is the discrepancy between characterization of the scope of the problem (e.g. “a serious public health concern”) (Richards et al., 2017b) and available evidence. Children with acute cannabis intoxication can experience potentially life-threatening symptoms such as coma, bradycardia and respiratory depression (Onders et al., 2016; Vo et al., 2018); however, the overall number of cases remains low, and deaths or significant morbidity are rarely reported (Gummin et al., 2019). A Canadian surveillance system capturing severe cases in patients <18 years reported 52 documented cases of serious and life-threatening cannabis-related events in 2019 (Canadian Paediatric Surveillance Program, 2019), and the limited number of severe outcomes being reported may explain the lack of primary information sources in this field.

While potential harms to children should never be downplayed, this scoping review did not identify evidence to support broad claims of significant public health harms from accidental single-substance cannabis exposures in children. We also did not find any reports of long-term consequences resulting from these single-exposure events. Although acute exposure events appear to occur infrequently, cases that are not serious or life-threatening can still be stressful events for families and thus have potential for harm. Quantification of the public health impacts of acute cannabis intoxications, especially over the longer term, are needed to evaluate the priority of this public health problem and guide decisions on harm mitigation from legalized cannabis.

Limitations

The broad scope of this review has identified not only gaps in the literature, but also challenges to its synthesis. To start, inconsistent language and keywords makes comprehensive searches in this field challenging; of 81 included information sources identified by reference and citation searching, 34 were published and indexed in MEDLINE at least 1 month before the initial search. Additionally, many publications in this area are case reports/series, which may be published as editorial letters and therefore more likely to be filtered out of rigorous syntheses/systematic reviews.

Duplicate reporting of case data, both in multiple large sample cohort studies and in small case-series, has the potential to bias systematic reviews in this area. Multiple studies used the same data sources to answer overlapping questions around the relationship between liberalization of cannabis policy (i.e. legalization) and incidence of pediatric cannabis exposures (Wang et al., 2013, 2017, 2019, 2020). The same is true of nation-wide American studies, many of which utilized data from the National Poison Data System (Cao et al., 2016; Onders et al., 2016; Graham et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2014). This calls into question the generalizability of the current evidence on a broader scale and highlights the importance for jurisdictions legalizing cannabis putting in place their own surveillance and research infrastructure to support evidence-based policy (Fischer et al., 2019).

Implications for practice

The Translating Emergency Knowledge for Kids network initiated an evidence repository (Featherstone et al., 2018) on acute cannabis intoxication to generate bottom-line recommendations and guide front-line pediatric HCPs managing children with acute cannabis intoxication (Hogue and Desai, 2021).

Unfortunately information sources reviewed relating to clinical management were predominately observational case studies/series. Currently, clinical management varies and is not strictly evidence based; clinical guidelines developed specifically for the pediatric population are lacking. Rigorous studies of suggested clinical treatments are needed to develop an evidence-base from which data can be synthesized and appraised to drive the development of clinical treatment recommendations.

To date, the experiences and information needs of those caring for children with cannabis intoxication have not been addressed. A greater understanding of the information required by caregivers is needed. Through consultation with HCPs and families, the usefulness of currently available resources could be explored and, coupled with an understanding of their experiences, used to tailor knowledge translation (KT) tools to meet the needs of clinicians and families. Developing KT tools that provide information on the signs and symptoms, as well as when/how to seek care, could prevent accidental exposures, increase recognition of signs and symptoms, and ensure early treatment/intervention is sought.

Conclusions

This scoping review examined the available information sources on acute pediatric cannabis intoxications. Despite a dramatic increase in publications over the last 5 years, evidence around acute pediatric cannabis intoxication remains limited to clinical observational studies and assessments of the impact of legalization on incidence. Modifiable risk factors and effectiveness of prevention strategies remain unstudied. Clinical practice varies and is not evidence based, as available recommendations are conflicting, and rely primarily on case series rather than rigorous clinical studies. Additional evidence is needed in order to make recommendations around best-practice clinical management.

Currently, there are significant gaps in the literature related to evidence-based clinical management strategies, environmental and social risk factors of acute cannabis intoxication to target prevention, and support for HCPs and families. However, as legalization in the USA and Canada has removed some of the barriers to research on this topic (namely access to previously restricted research materials and social desirability bias that may have limited participation), this expanding area of research will hopefully grow to fill those gaps, leading to improved care and management for children with unintentional acute cannabis intoxication.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material for Acute pediatric cannabis intoxication: A scoping review by Lindsay Gaudet, Kaitlin Hogue, Shannon Dawn Scott, Lisa Hartling and Sarah Elliott in Journal of Child Health Care

Supplemental Material for Acute pediatric cannabis intoxication: A scoping review by Lindsay Gaudet, Kaitlin Hogue, Shannon Dawn Scott, Lisa Hartling and Sarah Elliott in Journal of Child Health Care

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Michele Dyson and Maria Farag for their support drafting the scoping review protocol, Diana Keto-Lambert for completing the initial literature search, and Liza Bialy for assistance with data verification.

Appendix.

Abbreviations

USA = United States of America;

CPS = child protective services;

HCPs = Healthcare providers;

KT = knowledge translation;

MEDLINE = Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval Online System;

OSF = open science framework;

PRISMA = Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis;

THC = tetrahydrocannabinol.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by a Canadian Institutes for Health Research Foundation Grant (148411) awarded to Drs. Hartling and Scott. Dr. Hartling is supported by a Canada Research Chair in Knowledge Synthesis and Translation, Dr. Scott is supported by a Canada Research Chair in Knowledge Translation in Child Health and both are Distinguished Researchers with the Stollery Science Lab.

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

ORCID iD

SarahA Elliott https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9588-2226

References

- Amirav I, Luder A, Viner Y, et al. (2011) Decriminalization of cannabis–potential risks for children? Acta Paediatrica 100(4): 618–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amirshahi MM, Moss MJ, Smith SW, et al. (2019) ACMT position statement: addressing pediatric cannabis exposure. J Med Toxicol 15(3): 212–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appelboam A, Oades PJ. (2006) Coma due to cannabis toxicity in an infant. Eur J Emerg Med 13(3): 177–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrus DG, Capogrossi KL, Cates SC, et al. (2016) Tasty THC: Promises and Challenges of Cannabis EdiblesMethods Report. RTI Press. DOI: 10.3768/rtipress.2016.op.0035.1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashqoy F, Heizer JW, Reiter PD, et al. (2019) Increased testing and health care costs for pediatric cannabis exposures. Pediatric Emergency Care 37: e850–e854. DOI: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000001811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergeron S, Chiasson J, D’Ignazio T, et al. (2017) Reportno. Report Number|, Date. Place Published|. Institution Informative document on the effects and uses of cannabis. [Google Scholar]

- Blackstone M, Callahan J. (2008) An unsteady walk in the park. Pediatric Emergency Care 24(3): 193–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonkowsky JL, Sarco D, Pomeroy SL. (2005) Ataxia and shaking in a 2-year-old girl: acute marijuana intoxication presenting as seizure. Pediatric Emergency Care 21(8): 527–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns C, Burns R, Sanseau E, et al. (2018) Pediatric emergency medicine simulation curriculum: marijuana ingestion. MedEdPORTAL 14: 10780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camchong J, Lim KO, Kumra S. (2017) Adverse effects of cannabis on adolescent brain development: a longitudinal study. Cerebral Cortex 27(3): 1922–1930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Paediatric Surveillance Program (2019) CPSP 2018 ResultsReportno. Report Number|, Date. Place Published|. Institution|. [Google Scholar]

- Pediatric Society Canadian. (2020) Cannabis, Children & Youth Challenges for Paediatric Practice Pediatrics and Child Health, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Cao D, Srisuma S, Bronstein AC, et al. (2016) Characterization of edible marijuana product exposures reported to United States poison centers. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 54(9): 840–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstairs SD, Fujinaka MK, Keeney GE, et al. (2011) Prolonged coma in a child due to hashish ingestion with quantitation of THC metabolites in urine. The Journal of Emergency Medicine 41(3): e69–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caulkins JP, Kilborn ML. (2019) Cannabis legalization, regulation, & control: a review of key challenges for local, state, and provincial officials. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 45(6): 689–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chartier C, Penouil F, Blanc-Brisset I, et al. (2020) Pediatric cannabis poisonings in France: more and more frequent and severe. Clin Toxicol (Phila): 1–8. DOI: 10.1080/15563650.2020.1806295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Child Welfare Information Gateway (2016). In: Services USDoHaH (ed), Racial Disproportionality and Disparity in Child Welfare. Washington, DCChildrens’ Bureau: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- Cipriani F, Mancino A, Pulitano SM, et al. (2015) A cannabinoid-intoxicated child treated with dexmedetomidine: a case report. Molecular Cancer Research: MCR 9: 152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claudet I, Le Breton M, Brehin C, et al. (2017) A 10-year review of cannabis exposure in children under 3-years of age: do we need a more global approach? European Journal of Pediatrics 176(4): 553–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Close N. (2019) Adverse Health Effects of Marijuana Legalization. Washington: University of Washington. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen N, Galvis Blanco L, Davis A, et al. (2021) Pediatric cannabis intoxication trends in the pre and post-legalization era. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 60: 53–58. DOI: 10.1080/15563650.2021.1939881. 1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das JK, Salam RA, Arshad A, et al. (2016) Interventions for adolescent substance abuse: an overview of systematic reviews. J Adolesc Health 59(4S): S61–S75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Sonnaville-de Roy van Zuidewijn ML, Schilte PP. (1989) Cannabis poisoning in a young child; don’t ask about drugs. Nederlands tijdschrift voor geneeskunde 133(35): 1752–1753. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denison J, Varcoe C, Browne AJ. (2014) Aboriginal women’s experiences of accessing health care when state apprehension of children is being threatened. J Adv Nurs 70(5): 1105–1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Featherstone RM, Leggett C, Knisley L, et al. (2018) Creation of an integrated knowledge translation process to improve pediatric emergency care in Canada. Health Commun 33(8): 980–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer B, Russell C, Rehm J, et al. (2019) Assessing the public health impact of cannabis legalization in Canada: core outcome indicators towards an 'index' for monitoring and evaluation. Journal of Public Health 41(2): 412–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman KR, Havranek T. (2018) The pediatrician and marijuana: an era of change. Advances in Pediatrics 65(1): 159–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman N, Gantz J, Finkelstein Y. (2017) An (Un)fortune cookie: a 2-year-old with altered mental status. Pediatric Emergency Care 33(12): 811–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates A, Shave K, Featherstone R, et al. (2018. a) Procedural pain: systematic review of parent experiences and information needs. Clinical Pediatrics 57(6): 672–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates A, Shulhan J, Featherstone R, et al. (2018. b) A systematic review of parents’ experiences and information needs related to their child’s urinary tract infection. Patient Education and Counseling 101(7): 1207–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates M, Shulhan-Kilroy J, Featherstone R, et al. (2019) Parent experiences and information needs related to bronchiolitis: a mixed studies systematic review. Patient Education and Counseling 102(5): 864–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobbi G, Atkin T, Zytynski T, et al. (2019) Association of cannabis use in adolescence and risk of depression, anxiety, and suicidality in young adulthood: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 76(4): 426–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham J, Leonard J, Banerji S, et al. (2020) Illicit drug exposures in young pediatric patients reported to the national poison data system, 2006-2016. The Journal of Pediatrics 219: 254–258 e251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant CN, Belanger RE. (2017) Cannabis and Canada’s children and youth. Paediatr Child Health 22(2): 98–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gummin DD, Mowry JB, Spyker DA, et al. (2019) Annual report of the american association of poison control centers’ national poison data system (NPDS): 36th annual report. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 57(12): 1220–1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddaway NR, Collins AM, Coughlin D, et al. (2015) The role of google scholar in evidence reviews and its applicability to grey literature searching. Plos One 10(9): e0138237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddaway NR, Feierman A, Grainger MJ, et al. (2019) EviAtlas: a tool for visualising evidence synthesis databases. Environmental Entomology 8(1): 22. [Google Scholar]

- Hautin L. (2017) Accidental Cannabis Poisoning in Infants in Burgundy: A New Type of Domestic Accident: Series of Cases and Analysis of Local Practices. [Google Scholar]

- Heard K, Marlin MB, Nappe T, et al. (2017) Common marijuana-related cases encountered in the emergency department. American Journal of Health-system Pharmacy: Ajhp: Official Journal of the American Society of Health-system Pharmacists 74(22): 1904–1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heizer JW, Borgelt LM, Bashqoy F, et al. (2018) Marijuana misadventures in children: exploration of a dose-response relationship and summary of clinical effects and outcomes. Pediatric Emergency Care 34(7): 457–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hines L, Glick J, Bilka K, et al. (2018) Medical marijuana for minors may be considered child abuse. Pediatrics 142(4). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman SJ, Habibi R. (2016) International legal barriers to Canada’s marijuana plans. CMAJ 188(10): E215–E216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogue K, Desai N. (2021) Cannabis Intoxication. [Google Scholar]

- Kalant H. (2016) A critique of cannabis legalization proposals in Canada. Int J Drug Policy 34: 5–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavi E, Rekhtman D, Berkun Y, et al. (2016) Sudden onset unexplained encephalopathy in infants: think of cannabis intoxication. European Journal of Pediatrics 175(3): 417–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leduc-Pessah H, Jensen SK, Newell C. (2019) An overview of the adverse effects of cannabis use for Canadian physicians. Clinical and Investigative Medicine. Médecine clinique et experimentale 42(3): E17–e34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung J, Chiu V, Chan GCK, et al. (2019) What have been the public health impacts of cannabis legalisation in the USA? a review of evidence on adverse and beneficial effects. Current Addiction Reports 6(4): 418–428. [Google Scholar]

- Levene RJ, Pollak-Christian E, Wolfram S. (2019) A 21st century problem: cannabis toxicity in a 13-month-old child. The Journal of Emergency Medicine 56(1): 94–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maas B. (2015) Marijuana Intoxication Blamed in More Deaths, Injuries. CBS4. [Google Scholar]

- MacCoun RJ, Mello MM. (2015) Half-baked--the retail promotion of marijuana edibles. The New England Journal of Medicine 372(11): 989–991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahabir DF, O’Campo P, Lofters A, et al. (2021) Experiences of everyday racism in Toronto's health care system: a concept mapping study. Int J Equity Health 20(1): 74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGowan J, Straus S, Moher D, et al. (2020) Reporting scoping reviews-PRISMA ScR extension. J Clin Epidemiol 123: 177–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. (2018) PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine 169(7): 467–473. DOI: 10.7326/M18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miningou KRA. (2014) Les intoxications orales au cannabis chez l’enfant: aspects épidémiologique clinique évolutif et médico-légal. Morocco: UNIVERSITE MOHAMMED V- SOUISSI. [Google Scholar]

- Molly C, Mory O, Basset T, et al. (2012) [Acute cannabis poisoning in a 10-month-old infant]. Archives de pédiatrie: organe officiel de la Sociéte française de pédiatrie 19(7): 729–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan I, Abernethy S. (2019) G457(P) Acute cannabis intoxication in an infant. Archives of Disease in Childhood 104(Suppl 2): A185–A185. [Google Scholar]

- Murti M. (2017) Pediatric presentations and risks from consuming cannabis edibles. British Columbia Medical Journal 59(8): 2. [Google Scholar]

- Myran DT, Cantor N, Finkelstein Y, et al. (2022) Unintentional pediatric cannabis exposures after legalization of recreational cannabis in Canada. JAMA Network Open 5(1): e2142521–e2142521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen TTJ, Cho AK. (2016) Treat plays trick on a 3-year-old boy. Contemporary Pediatrics. [Google Scholar]

- Noel GN, Maghoo AM, Franke FF, et al. (2019) Increase in emergency department visits related to cannabis reported using syndromic surveillance system. European Journal of Public Health 29(4): 621–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onders B, Casavant MJ, Spiller HA, et al. (2016) Marijuana exposure among children younger than six years in the United States. Clinical Pediatrics 55(5): 428–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelissier F, Claudet I, Pelissier-Alicot AL, et al. (2014) Parental cannabis abuse and accidental intoxications in children: prevention by detecting neglectful situations and at-risk families. Pediatric Emergency Care 30(12): 862–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pires S, Paula Rocha A, Martins L, et al. (2018) Cannabinoid intoxication in children: a challenge in pediatric age. Polish Journal of Pathology: Official Journal of the Polish Society of Pathologists 49(4). [Google Scholar]

- Ragab AR, Al-Mazroua MK, Mahmoud NF. (2014) Accidental substance abuse poisoning in children: experience of the dammam poison control center. Journal of Clinical Toxicology 4(3): 1000204. [Google Scholar]

- Richards JR, Smith NE, Moulin AK. (2017. a) Unintentional cannabis ingestion in children: a systematic review. The Journal of Pediatrics 190: 142–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards JR, Smith NE, Moulin AK. (2017. b) Unintentional cannabis ingestion in children: a systematic review. The Journal of Pediatrics 190: 142–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochman B. (2013) More kids accidently ingesting marijuana folling new drug policies. Family Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio F, Quintero S, Hernandez A, et al. (1993) Flumazenil for coma reversal in children after cannabis. Lancet 341(8851): 1028–1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla PC, Moore UB. (2004) Marijuana-induced transient global amnesia. Southern Medical Journal 97(8): 782–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spadari M, Glaizal M, Tichadou L, et al. (2009) Accidental cannabis poisoning in children: experience of the Marseille poison center. La Presse Médicale 38(11): 1563–1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas AA, Dickerson-Young T, Mazor S. (2018) Unintentional pediatric marijuana exposures at a tertiary care children’s hospital in washington state: a retrospective review. Pediatr Emerg Care. DOI: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000001703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas AA, Mazor S. (2017) Unintentional marijuana exposure presenting as altered mental status in the pediatric emergency department: a case series. The Journal of Emergency Medicine 53(6): e119–e123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas AA, Moser E, Dickerson-Young T, et al. (2017) A review of pediatric marijuana exposure in the setting of increasing legalization. Clinical Pediatric Emergency Medicine 18(3): 159–162. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas AA, Von Derau K, Bradford MC, et al. (2019) Unintentional pediatric marijuana exposures prior to and after legalization and commercial availability of recreational marijuana in Washington State. The Journal of Emergency Medicine 56(4): 398–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (2019) Reportno. Report Number|, Date. Place Published|. Institution|.World Drug Report. [Google Scholar]

- Vo KT, Horng H, Li K, et al. (2018) Cannabis intoxication case series: the dangers of edibles containing tetrahydrocannabinol. Annals of Emergency Medicine 71(3): 306–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G. (2019) Cannabis (Marijuana): Acute Intoxication. [Google Scholar]

- Wang GS. (2017) Pediatric concerns due to expanded cannabis use: unintended consequences of legalization. J Med Toxicol 13(1): 99–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GS, Banerji S, Contreras AE, et al. (2018) Marijuana exposures in Colorado, reported to regional poison centre. Inj Prev 26(2): 184–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GS, Davies SD, Halmo LS, et al. (2018) Impact of marijuana legalization in colorado on adolescent emergency and urgent care visits. J Adolesc Health 63(2): 239–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GS, Hall K, Vigil D, et al. (2017) Marijuana and acute health care contacts in Colorado. Preventive Medicine 104: 24–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GS, Hoyte C, Roosevelt G, et al. (2019) The continued impact of marijuana legalization on unintentional pediatric exposures in colorado. Clinical Pediatrics 58(1): 114–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GS, Le Lait MC, Deakyne SJ, et al. (2016) Unintentional pediatric exposures to marijuana in colorado, 2009-2015. JAMA Pediatr 170(9): e160971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GS, Roosevelt G, Heard K. (2013) Pediatric marijuana exposures in a medical marijuana state. JAMA Pediatr 167(7): 630–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GS, Roosevelt G, Le Lait MC, et al. (2014) Association of unintentional pediatric exposures with decriminalization of marijuana in the United States. Annals of Emergency Medicine 63(6): 684–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehill JM, Harrington C, Lang CJ, et al. (2019) Incidence of pediatric cannabis exposure among children and teenagers aged 0 to 19 years before and after medical marijuana legalization in Massachusetts. JAMA Network Open 2(8): e199456e199456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf LA, Perhats C, Clark PR, et al. (2020) The perceived impact of legalized cannabis on nursing workload in adult and pediatric emergency department visits: a qualitative exploratory study. Public Health Nursing 37(1): 5–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong KU, Baum CR. (2019) Acute cannabis toxicity. Pediatric Emergency Care 35(11): 799–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong SS, Wilens TE. (2017) Medical cannabinoids in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Pediatrics 140(5). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarider NS, Phelps JB, Berman AJ, et al. (2015) Authors’ response to “parental cannabis abuse and accidental intoxication in children: prevention by detecting neglectful situations and at-risk families”. Pediatric Emergency Care 31(10). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H, Wu LT. (2016) Trends and correlates of cannabis-involved emergency department visits: 2004 to 2011. J Addict Med 10(6): 429–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material for Acute pediatric cannabis intoxication: A scoping review by Lindsay Gaudet, Kaitlin Hogue, Shannon Dawn Scott, Lisa Hartling and Sarah Elliott in Journal of Child Health Care

Supplemental Material for Acute pediatric cannabis intoxication: A scoping review by Lindsay Gaudet, Kaitlin Hogue, Shannon Dawn Scott, Lisa Hartling and Sarah Elliott in Journal of Child Health Care