Abstract

Abnormal erythropoietin (EPO)-independent cell growth is induced after infection of erythroid progenitor cells with a polycythemic strain of Friend virus (FVp). Binding of its Env-related glycoprotein (gp55) to the EPO receptor (EPOR) mimics the activation of the EPOR with EPO. We investigated the gp55-EPOR signaling in erythroblastoid cells from mice infected with FVp and in cells of FVp-induced or gp55-transgenic-mouse-derived erythroleukemia cell lines, comparing it with the EPO-EPOR signaling in EPO-responsive erythroblastoid cells. While the Janus protein tyrosine kinase JAK2 and the transcription factor STAT5 became tyrosine phosphorylated with the EPO stimulation in EPO-responsive erythroblastoid cells from anemic mice, JAK1 and STAT5 were constitutively tyrosine phosphorylated in all of these FVp gp55-induced erythroblastoid or erythroleukemic cells. Moreover, this constitutively tyrosine-phosphorylated STAT5 was unable to bind to its specific DNA sequences and did not translocate to the nucleus. Nuclear translocation and DNA binding of this STAT5 species required EPO stimulation. These findings clearly indicate that the FVp gp55-EPOR signaling is distinct from the EPO-EPOR signaling and suggest that STAT5 may not play an essential role in the transmission of the cell growth signals in FVp gp55-induced erythroleukemia cells.

Erythropoietin (EPO) is a hematopoietic cytokine which regulates erythrocyte production, acting on proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis of erythroid progenitor cells (25). The EPO receptor (EPOR) is a type I cytokine receptor, one of the four subtypes of the cytokine receptor superfamily (10, 45). Following EPO stimulation, the EPOR, which has no catalytic activity as do other members of the cytokine receptor superfamily, associates with and activates JAK2 tyrosine kinase, a member of the Janus kinase (JAK) family (32, 52). This activation of JAK2 induces rapid tyrosine phosphorylation of the EPOR and STATs (signal transducers and activators of transcription) and association of the EPOR with a variety of cellular proteins possessing the Src homology 2 (SH2) domain, such as Shc (9, 29), hematopoietic protein tyrosine phosphatase 1 (22, 56), and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3-K) (8, 14, 31).

The JAKs are responsible for a variety of cytokine signaling. By using mutant cell lines defective in their response to interferons (IFNs), JAKs were first demonstrated to be involved in IFN signaling mediated by the IFN receptors, the type II cytokine receptors (46). JAK1 and Tyk2 are required for alpha/beta IFN (IFN-α/β) signaling, and JAK1 and JAK2 are required for IFN-γ signaling. The interleukin-2 (IL-2) receptor β chain (βc) and γc associate with JAK1 and JAK3, respectively, and activate each JAK in IL-2 signaling of T cells (3, 20, 33, 53). NIH 3T3 cell-derived transfectants expressing the reconstituted IL-2 receptors become responsive to IL-2 only after expression of JAK3, indicating that JAK3 plays a critical role in IL-2 signaling (33). The STATs are cytoplasmic transcription factors possessing SH2 and SH3 domains and undergo rapid tyrosine phosphorylation after cytokine stimulation of the receptor. The tyrosine-phosphorylated STATs then become dimerized and translocate to the nucleus, where they regulate the expression of their target genes by binding to specific DNA sequences, such as the IFN-γ activation site (GAS)-related sequence and the IFN-stimulated response element (12, 15, 27). Recent evidence indicates that specific JAKs and STATs are constitutively tyrosine phosphorylated in cells transformed with human T-cell lymphotropic virus type I (30), v-src (57), v-abl (11), or v-mpl (36), suggesting that activation of the JAK/STAT pathway participates in transformation of the cells by viral oncoproteins.

A replication-defective Friend spleen focus-forming virus (F-SFFV) of the polycythemic strain of Friend virus complex (FVp) causes erythroleukemia in adult mice (5). Although it has been demonstrated that a glycoprotein of 55 kDa (gp55) encoded by an env-related gene of F-SFFV binds to the EPOR and makes EPO-dependent cells factor independent (28), its signaling mechanism remains obscure. By using EPOR-expressing transfectants derived from nonerythroid cells, EPO has been found to activate the JAK2/STAT5 pathway downstream of the EPOR (13, 38, 49). It remains to be elucidated, however, which JAKs and STATs are actually used in normal erythroid cells that are the natural targets for EPO and FVp gp55. In this study, we report that the JAK2/STAT5 pathway is activated upon EPO stimulation of the EPOR in normal erythroblastoid cells. In contrast, JAK1 is constitutively activated by FVp gp55 stimulation of the EPOR in Friend erythroleukemia cells. We further show that the DNA binding activity of STAT5 is induced by EPO stimulation but not by this gp55 stimulation alone.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of splenic erythroblastoid cells from FVp-infected mice.

Female DBA/2N mice, 7 weeks old, were intravenously injected with a virus stock of FVp via the tail vein. After 3 weeks, the enlarged spleens from infected mice were minced in Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium (IMDM) supplemented with 30% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum (FBS) to prepare single-cell suspensions; the erythrocytes were lysed by exposure to erythrocyte-lysing buffer (15 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.6], 150 mM NH4Cl) at 37°C. The spleen cells were washed and resuspended in IMDM supplemented with 30% (vol/vol) FBS.

Preparation of normal erythroblastoid cells from anemic mice.

Female DBA/2N mice were injected intraperitoneally with 60 mg of phenylhydrazine hydrochloride (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) per kg daily for 2 days. Three days after the second injection, spleens were removed and minced in IMDM supplemented with 30% (vol/vol) FBS. The erythrocytes were lysed as described above, and the spleen cells were washed and resuspended in IMDM supplemented with 30% (vol/vol) FBS.

Cells and cell culture.

The FVp-induced mouse erythroleukemia cell line T3Cl-2-O (16) and the erythroleukemia cell line EL-TG-gp55-1-2, which had been established from the enlarged spleen of an FVp gp55-transgenic mouse (2), were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) FBS. An EPO-dependent mouse erythroleukemia cell line, HCD57 (39), was maintained in IMDM supplemented with 30% (vol/vol) FBS and recombinant human EPO (1 U/ml).

Antibodies.

Rabbit anti-JAK1 and anti-JAK2 antibodies and an antiphosphotyrosine monoclonal antibody (4G10) were purchased from Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, N.Y. A rabbit anti-EPOR antiserum was a gift from O. Miura, Tokyo Medical and Dental University. Rabbit anti-STAT1 and anti-STAT3 antibodies were purchased from Upstate Biotechnology. Mouse anti-STAT1α monoclonal antibody and rabbit anti-STAT3 antibody were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, Calif. A rabbit anti-STAT5 antiserum was a gift from H. Wakao, University of Tokyo.

Immunoprecipitation and Western blotting for detection of JAK/STAT phosphorylation.

Cells were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline and starved in the RPMI 1640 medium or IMDM supplemented with 1% (vol/vol) bovine serum albumin (BSA) at 37°C. The cells were unstimulated or stimulated with EPO (10 U/ml) for 10 min at 37°C and lysed in lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mM Na3VO4). Insoluble material was pelleted at 20,000 × g for 20 min. Nuclear and cytoplasmic extract fractions were prepared as described previously (40). Cell lysates were incubated with antibodies and protein G-Sepharose (Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden) at 4°C. Immunoprecipitates were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (7.5% polyacrylamide) under reducing conditions and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Atto Corporation, Hongo, Tokyo, Japan). Blots were incubated with antibodies, and immune complexes were visualized with the ECL chemiluminescence system (Amersham, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) for detection of STAT DNA binding.

Nuclear extracts were prepared as described previously (40) and added to 20 μl of reaction mixture containing 2 μg of poly(dI-dC) (Pharmacia Biotech) and 1 ng of 32P-end-labeled double-stranded probe oligonucleotide corresponding to the prolactin-responsive element (PRE) in the bovine β-casein promoter (48), the GAS of the mouse IFN regulatory factor-1 (IRF-1) promoter (43), or the high-affinity sis-inducible element (SIE) (m67) of the c-fos promoter (47). The mixtures were incubated for 30 min at room temperature as described previously (49). Complexes were separated on 5% polyacrylamide gels in 0.25× Tris-borate-EDTA electrophoresis buffer and detected by autoradiography. For a supershift assay, 10 μg of anti-STAT1, anti-STAT3, or anti-STAT5 antibody was added to the binding reaction mixture.

RESULTS

JAK1, but not JAK2, is constitutively activated in FVp-infected primary splenic erythroblastoid cells.

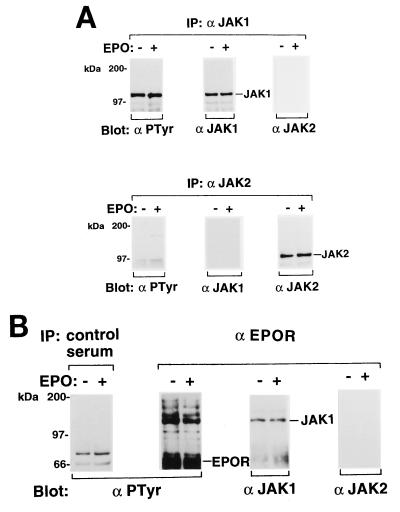

We examined tyrosine phosphorylation of JAKs in erythroblastoid cells obtained from the FVp-infected erythroleukemic mice. Ninety-two percent of total spleen cells were erythroid cells in the FVp-infected mice as determined by flow cytometric analysis with the anti-mouse erythroid cell monoclonal antibody TER-119 (17). The spleen cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline and incubated in IMDM supplemented with 1% BSA for 8 h at 37°C. They were unstimulated or stimulated with EPO for 10 min and then lysed. JAK1 and JAK2 were immunoprecipitated from the cell lysates with the anti-JAK1 and anti-JAK2 antibodies, respectively. The immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blotting with the antiphosphotyrosine antibody 4G10 or with anti-JAK1 or anti-JAK2 antibody. As shown in Fig. 1A, only JAK1 was constitutively tyrosine phosphorylated; JAK2 was not tyrosine phosphorylated at all. The tyrosine phosphorylation of JAK1 was not increased by EPO stimulation. Next, the EPOR complexes were immunoprecipitated with the anti-EPOR antiserum from the cell lysates and analyzed by Western blotting with the 4G10, anti-JAK1, or anti-JAK2 antibody. JAK1 was coimmunoprecipitated with the EPOR in both unstimulated and EPO-stimulated cells (Fig. 1B). Reprobing with the 4G10 antibody revealed that the EPOR was tyrosine phosphorylated with or without EPO stimulation.

FIG. 1.

(A) Constitutive tyrosine phosphorylation of JAK1 in FVp-infected erythroblastoid cells. Erythroblastoid cells from FVp-infected mice were starved for 8 h and then incubated in the presence (+) or absence (−) of EPO (10 U/ml) for 10 min at 37°C. JAK1 and JAK2 were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-JAK1 (α JAK1) and anti-JAK2 (α JAK2) antibodies, respectively, and analyzed by Western blotting with the antiphosphotyrosine 4G10 (α PTyr), anti-JAK1, or anti-JAK2 antibody. (B) Coimmunoprecipitation of JAK1 and the EPOR in FVp-infected erythroblastoid cells. The EPOR complexes were immunoprecipitated with the anti-EPOR antiserum (α EPOR). A similar immunoprecipitation was performed with normal rabbit serum (control serum). The complexes were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with the antiphosphotyrosine 4G10, anti-JAK1, or anti-JAK2 antibody.

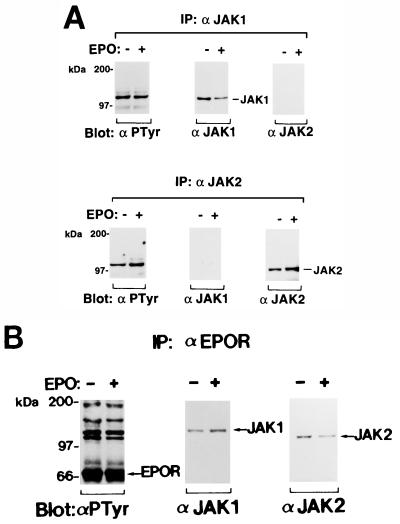

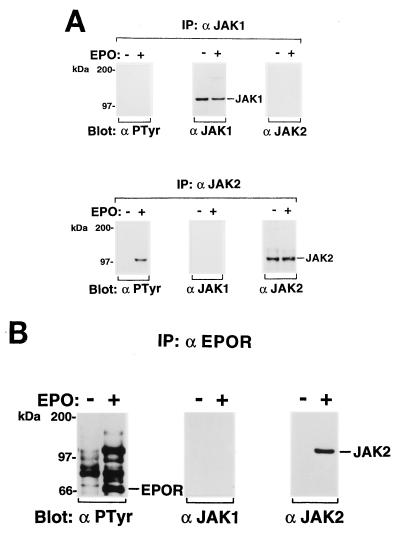

We performed similar Western blotting analysis with the Friend erythroleukemia cell lines. The FVp-induced T3-Cl-2-O cell line (16) expresses both the EPOR and gp55 on the cell surface and shows factor-independent cell growth. The cells were incubated in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 1% BSA for 13 h at 37°C and then either not stimulated or stimulated with EPO. Both JAK1 and JAK2 were constitutively tyrosine phosphorylated (Fig. 2A) and coimmunoprecipitated with the EPOR (Fig. 2B). The EPOR was constitutively tyrosine phosphorylated. The tyrosine phosphorylation of JAK1, JAK2, and EPOR was not increased by EPO stimulation. EL-Tg-gp55-1-2 and -2-2 (abbreviated as 1-2 and 2-2) are factor-independent erythroleukemia cell lines established from the enlarged spleen of an FVp gp55-transgenic mouse (2). JAK1 was constitutively tyrosine phosphorylated but JAK2 was not tyrosine phosphorylated in 1-2 cells (Fig. 3). Similar results were obtained with 2-2 cells (data not shown). We were unable to show coimmunoprecipitation of JAK1 with the EPOR by using the anti-EPOR antiserum. This might be because of a lower expression level of the EPOR or a weak association of JAK1 with the EPOR in 1-2 and 2-2 cells. Thus, constitutive activation of JAK1 was shown in the FVp gp55-EPOR signaling.

FIG. 2.

(A) Constitutive tyrosine phosphorylation of both JAK1 and JAK2 in the FVp-induced erythroleukemia cell line T3Cl-2-O. T3Cl-2-O (16) cells were starved for 13 h and then not stimulated (−) or stimulated (+) with EPO (10 U/ml) for 10 min at 37°C. JAK1 and JAK2 were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-JAK1 (α JAK1) and anti-JAK2 (α JAK2) antibodies, respectively, and analyzed by Western blotting with the antiphosphotyrosine 4G10 (αPTyr), anti-JAK1, or anti-JAK2 antibody. (B) Coimmunoprecipitation of JAK1 and JAK2 with the EPOR in T3Cl-2-O cells. The EPOR complexes were immunoprecipitated and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with the antiphosphotyrosine 4G10, anti-JAK1, or anti-JAK2 antibody.

FIG. 3.

Constitutive tyrosine phosphorylation of JAK1 in the EL-TG-gp55-1-2 (1-2) erythroleukemia cell line established from the FVp gp55-transgenic mouse (2). The cells were starved for 13 h and then incubated in the presence (+) or absence (−) of EPO (10 U/ml) for 10 min at 37°C. JAK1 and JAK2 were immunoprecipitated (IP) with the anti-JAK1 (α JAK1) and anti-JAK2 (α JAK2) antibodies, respectively, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with the antiphosphotyrosine 4G10 (α PTyr), anti-JAK1, or anti-JAK2 antibody.

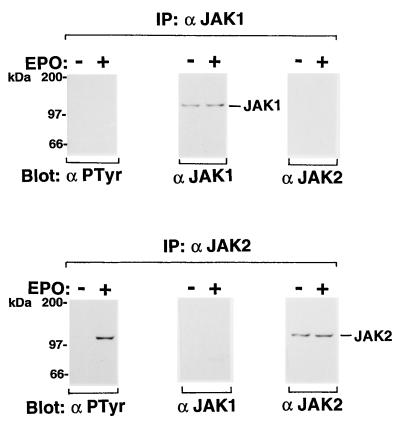

JAK2 is activated with EPO stimulation in EPO-responsive normal erythroblastoid cells.

We also examined tyrosine phosphorylation of JAKs in the EPO-responsive normal erythroblastoid cells from the spleens of phenylhydrazine hydrochloride-induced anemic mice. Eighty-one percent of the total spleen cells were erythroid cells as determined by flow cytometric analysis with the TER-119 antibody. The MTT assay (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) indicated that these erythroblastoid cells were induced to proliferate in response to EPO (data not shown). As shown in Fig. 4, JAK2 and the EPOR were tyrosine phosphorylated and coimmunoprecipitated with the anti-EPOR antiserum in response to EPO stimulation.

FIG. 4.

(A) EPO-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of JAK2 in EPO-responsive erythroblastoid cells from anemic mice. Erythroblastoid cells from phenylhydrazine hydrochloride-treated anemic mice were starved for 8 h and then not stimulated (−) or stimulated (+) with EPO (10 U/ml) for 10 min at 37°C. JAK1 and JAK2 were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-JAK1 (α JAK1) and anti-JAK2 (α JAK2) antibodies, respectively, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with the antiphosphotyrosine 4G10 (αPTyr), anti-JAK1, or anti-JAK2 antibody. (B) Coimmunoprecipitation of JAK2 and the EPOR in EPO-responsive erythroblastoid cells. The EPOR complexes immunoprecipitated with the anti-EPOR antiserum were analyzed by Western blotting with the antiphosphotyrosine 4G10, anti-JAK1, or anti-JAK2 antibody.

We performed similar Western blotting analysis with the EPO-dependent erythroleukemia cell line HCD57, which expresses the EPOR but not FVp gp55. The EPO stimulation induced tyrosine phosphorylation of JAK2 but not JAK1 (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

EPO-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of JAK2 in the EPO-dependent erythroleukemia cell line HCD57. HCD57 (39) cells were starved for 2 h and then incubated in the presence (+) or absence (−) of EPO (10 U/ml) for 10 min at 37°C. JAK1 and JAK2 were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-JAK1 (α JAK1) and anti-JAK2 (α JAK2) antibodies, respectively, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with the antiphosphotyrosine 4G10 (αPTyr), anti-JAK1, or anti-JAK2 antibody.

EPO stimulation, but not FVp gp55 stimulation alone, induces STAT5 DNA binding activity in erythroid cells.

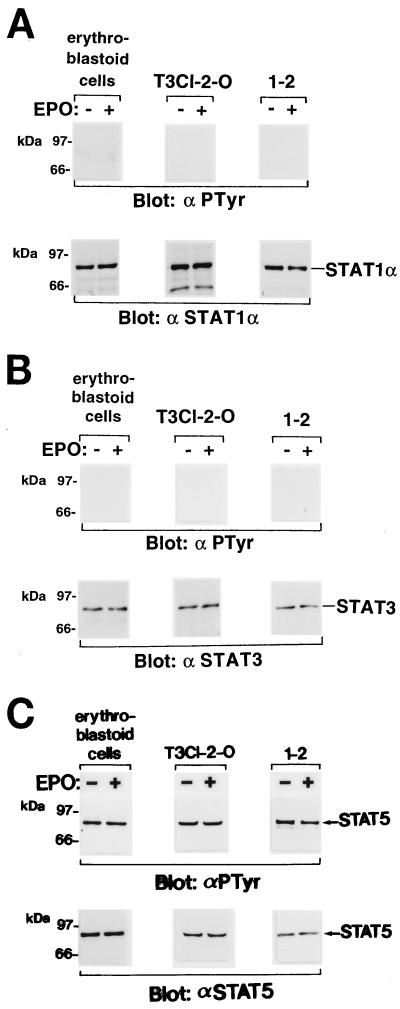

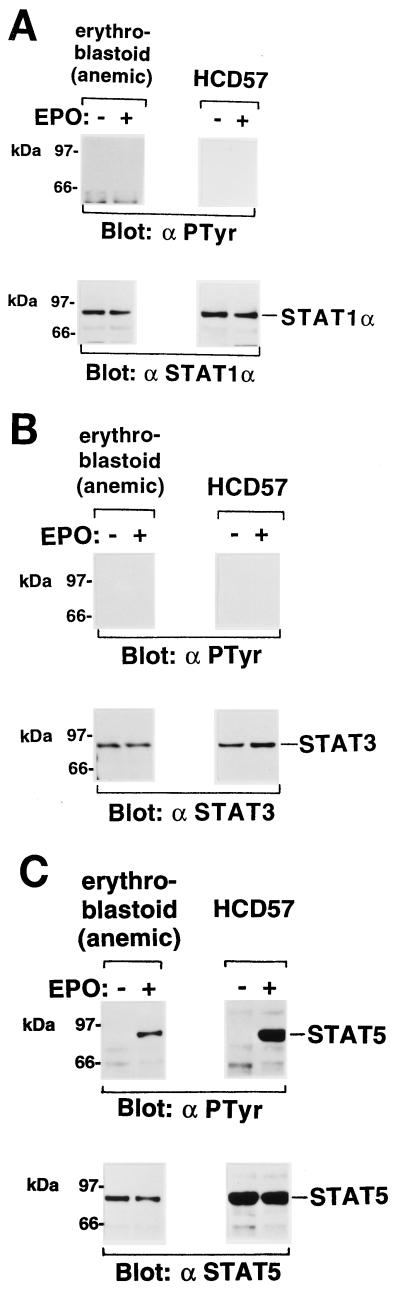

We examined tyrosine phosphorylation and DNA binding activity of STATs in signaling via the EPOR. Erythroblastoid cells prepared from FVp-infected mice and anemic mice and cells of the erythroleukemia cell lines were starved in medium supplemented with 1% BSA and then incubated in the presence or absence of EPO for 10 min at 37°C. STAT1α, STAT3, and STAT5 proteins were immunoprecipitated with antibodies specific for STAT1α, STAT3, and STAT5, respectively, and analyzed by Western blotting with the antiphosphotyrosine 4G10 antibody. STAT5, but neither STAT1α nor STAT3, was constitutively tyrosine phosphorylated in the FVp-infected erythroblastoid, T3Cl-2-O, and 1-2 cells (Fig. 6). In contrast, tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT5, but not STAT1α and STAT3, was induced by EPO stimulation only in the erythroblastoid cells from anemic mice and in HCD57 cells (Fig. 7).

FIG. 6.

Constitutive tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT5 in erythroleukemia cells. Erythroblastoid cells from FVp-infected mice spleens and cells of the T3Cl-2-O and 1-2 cell lines were starved and then incubated in the presence (+) or absence (−) of EPO (10 U/ml) for 10 min at 37°C. STAT1α (A), STAT3 (B), and STAT5 (C) were immunoprecipitated with anti-STAT1α (α STAT1α), anti-STAT3 (α STAT3), and anti-STAT5 (α STAT5) antibodies, respectively, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with the antiphosphotyrosine 4G10 (αPTyr), anti-STAT1α, anti-STAT3, or anti-STAT5 antibody.

FIG. 7.

EPO-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT5 in EPO-responsive erythroblastoid cells from anemic mice and the EPO-dependent HCD57 cell line. Cells were starved and then incubated in the presence (+) or absence (−) of EPO (10 U/ml) for 10 min at 37°C. STAT1α (A), STAT3 (B), and STAT5 (C) were immunoprecipitated with anti-STAT1α (α STAT1α), anti-STAT3 (α STAT3), and anti-STAT5 (α STAT5) antibodies, respectively, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with the antiphosphotyrosine 4G10 (αPTyr), anti-STAT1α, anti-STAT3, or anti-STAT5 antibody.

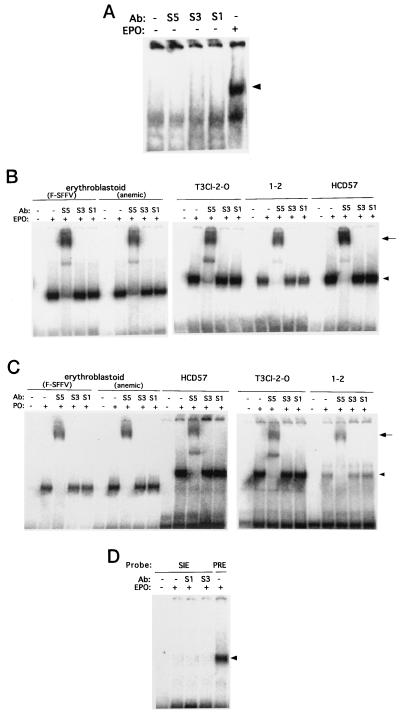

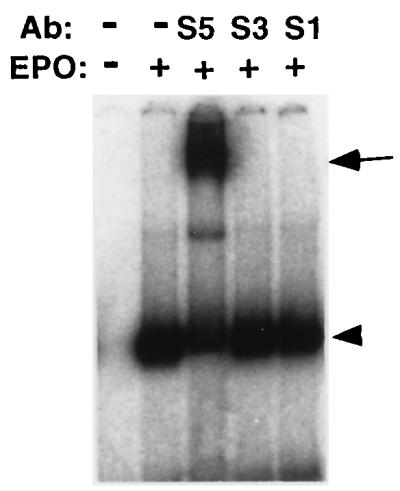

EMSAs were then carried out with DNA sequences recognized as binding motifs by STAT1, STAT3, or STAT5. Nuclear extracts prepared from the unstimulated FVp-infected erythroblastoid cells possessed no DNA binding activity with the PRE of the bovine β-casein promoter (Fig. 8A), while STAT5 was constitutively tyrosine phosphorylated in these cells (Fig. 6C). Additional EPO stimulation of these cells rapidly induced their DNA binding activity. All of the nuclear extracts prepared from the unstimulated FVp-infected erythroblastoid, T3Cl-2-O, and 1-2 cells possessed no DNA binding activity either with the PRE (Fig. 8B) or with the GAS of the mouse IRF-1 promoter (Fig. 8C). EPO stimulation, however, rapidly induced DNA binding activity of the nuclear extracts. The complexes bound to the PRE migrated with the same mobility as those bound to the IRF-1 GAS. Supershift assays were performed with anti-STAT1, anti-STAT3, and anti-STAT5 antibodies (Fig. 8B and C). Both the PRE and IRF-1 GAS binding complexes were supershifted by treatment of nuclear extracts with the anti-STAT5 antibody but not by treatment with the anti-STAT1 and anti-STAT3 antibodies. The DNA binding complexes induced in primary erythroblastoid cells migrated a little faster than the complexes induced in the cells of erythroleukemia cell lines. Naturally occurring carboxyl-truncated variant forms of STAT5 have recently been reported (50). Truncation of STAT5 might occur naturally in vivo. On the other hand, EPO stimulation induced DNA binding activity of nuclear extracts from the EPO-responsive erythroblastoid cells and EPO-dependent HCD57 cells with the PRE (Fig. 8B) and the IRF-1 GAS (Fig. 8C). Both DNA binding complexes were supershifted by treatment of the extracts with the anti-STAT5 antibody but not by treatment with the anti-STAT1 and anti-STAT3 antibodies. We also examined DNA binding activity of nuclear extracts from HCD57 cells with the high-affinity SIE (m67) of the c-fos promoter. No DNA binding complexes were detected (Fig. 8D).

FIG. 8.

(A) Nuclear extracts from unstimulated FVp-infected erythroblastoid cells have no DNA binding activity. FVp-infected erythroblastoids were incubated in the presence (+) or absence (−) of EPO (10 U/ml) for 20 min at 37°C. Nuclear extracts were prepared and analyzed in EMSAs with the PRE in the β-casein promoter as a probe in the presence or absence (−) of an excess of an anti-STAT1 (S1), anti-STAT3 (S3), or anti-STAT5 (S5) antibody (Ab). (B and C) EPO-induced STAT5 DNA binding activity in erythroblastoid and erythroleukemia cells. Erythroblastoid cells from FVp-infected mice and anemic mice and cells of the T3Cl-2-O, 1-2 and HCD57 cell lines were incubated in the presence (+) or absence (−) of EPO. Their nuclear extracts were analyzed in EMSAs with the PRE (B) and the GAS of IRF-1 (C) as probes in the presence or absence (−) of an excess of an anti-STAT1, anti-STAT3, or anti-STAT5 (S5) antibody. (D) Nuclear extracts from unstimulated (−) or EPO-stimulated (+) HCD57 cells were analyzed in EMSAs with the high-affinity SIE (m67) of the c-fos promoter and the PRE as probes in the presence or absence (−) of an anti-STAT1 or anti-STAT3 antibody. The DNA binding complexes are indicated by arrowheads. The supershifted complexes are indicated by arrows.

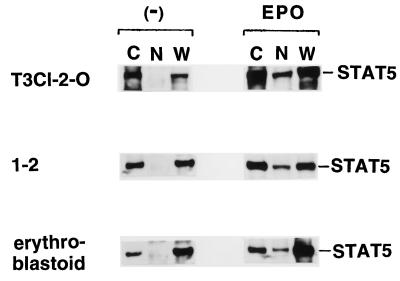

STAT5 which is constitutively tyrosine phosphorylated by FVp gp55 stimulation does not translocate to the nucleus and is unable to bind DNA.

The unexpected data described above clearly indicated that the tyrosine-phosphorylated STAT5 could not bind to its specific DNA motifs. We therefore tried to confirm nuclear translocation of the tyrosine-phosphorylated STAT5 in the FVp-infected erythroblastoid, T3Cl-2-O, and 1-2 cells. Cytoplasmic and nuclear extract fractions and whole-cell lysates were prepared from unstimulated or EPO-stimulated cells. STAT5 was immunoprecipitated with the anti-STAT5 antiserum and was analyzed by Western blotting with the antiphosphotyrosine 4G10 antibody. As shown in Fig. 9, the tyrosine-phosphorylated STAT5 was detected in the cytoplasmic fractions and the whole-cell lysates but was not detected in the nuclear fractions without EPO stimulation. Immediately after EPO stimulation, tyrosine-phosphorylated STAT5 appeared in the nuclear fractions.

FIG. 9.

Constitutively tyrosine-phosphorylated STAT5 does not translocate to the nucleus without EPO stimulation in FVp-infected erythroblastoid, T3Cl-2-O, and 1-2 cells. Cytoplasmic (lanes C) and nuclear (lanes N) extract fractions and whole-cell lysates (lanes W) were prepared from unstimulated (−) or EPO-stimulated cells. STAT5 was immunoprecipitated with an anti-STAT5 antiserum and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with the antiphosphotyrosine 4G10 antibody.

Moreover, we examined the DNA binding activity of cytoplasmic fractions from the unstimulated FVp-infected erythroblastoid cells with the PRE. As shown in Fig. 10, the cytoplasmic fraction from the unstimulated cells possessed no DNA binding activity. After EPO stimulation of the cells, the cytoplasmic fraction had DNA binding activity. These DNA binding complexes were supershifted by treatment of the extracts with the anti-STAT5 antibody but not by treatment with the anti-STAT1 and anti-STAT3 antibodies. Similar results were obtained with cytoplasmic fractions from the FVp-induced T3Cl-2-O cells (data not shown).

FIG. 10.

The cytoplasmic fraction from unstimulated FVp-infected erythroblastoid cells has no DNA binding activity. FVp-infected erythroblastoid cells were incubated in the presence (+) or absence (−) of EPO (10 U/ml) for 20 min at 37°C. Cytoplasmic fractions were prepared and analyzed in EMSAs with the PRE as a probe in the presence or absence (−) of an anti-STAT1 (S1), anti-STAT3 (S3), or anti-STAT5 (S5) antibody (Ab). The DNA binding complexes are indicated by the arrowhead. The supershifted complexes are indicated by the arrow.

DISCUSSION

Previous reports have provided evidence that the JAK2/STAT5 pathway is activated in EPO signaling (32, 49, 52); however, actual involvement of this pathway has not been well demonstrated in normal erythroid cells, which are real target cells of EPO. To our knowledge, our previous finding was the first demonstration of the activation of JAK2 in mouse erythroleukemia cells (54). Although JAK2 activation in the human erythroleukemia cell line TF-1 (7) and in the mouse erythroleukemia cell line HCD57 (41) has also been shown, it still remains unclear whether JAK2 is indeed activated following EPO stimulation of the EPOR in normal erythroid cells. Our present results indicated that the JAK2/STAT5 pathway is actually activated by EPO stimulation in the EPO-responsive normal erythroblastoid cells from anemic mice.

Since gp55, a membrane glycoprotein of FVp, binds to the EPOR and sends growth signals to the cells, it has been postulated that the same signaling pathway is recruited by FVp gp55-EPOR and EPO-EPOR signaling. However, we found that JAK1, but not JAK2, was constitutively activated in FVp gp55-EPOR signaling (55). It has been proposed that each cytokine receptor selectively associates with and activates a specific JAK(s). The EPOR activates JAK2 (32, 49, 52), while IL-2 receptor βc and γc subunits activate JAK1 and JAK3, respectively (3, 20, 33, 53). In our observation, however, the EPOR associated with and activated JAK1 in addition to JAK2 in erythroid cells. Stahl et al. (44) reported that IL-6 stimulation induced tyrosine phosphorylation of distinct JAKs in different cell lines. After IL-6 stimulation, tyrosine phosphorylation of JAK1, JAK2, and Tyk2 and of JAK1 and JAK2 was induced in SK-MES cells and EW-1 Ewing’s sarcoma cells, respectively. JAK1 and Tyk2 were tyrosine phosphorylated in U266 myeloma cells following the IL-6 stimulation. These distinct patterns of JAK tyrosine phosphorylation are not explained by the expression level of each JAK. A recent report has indicated that the extracellular domain of the IFN-γR2 chain of the IFN-γ receptor complex recruited Tyk2 to transmit the IFN-γ signal, instead of JAK2, which is usually recruited for IFN-γ signaling, using chimeric receptors possessing an extracellular domain of the IFN-γR2 (24). Thus, one member of the JAK family might be able to functionally substitute for the other members in cytokine receptor signaling.

Both JAK1 and JAK2 were associated with the EPOR and constitutively tyrosine phosphorylated in T3Cl-2-O cells (Fig. 2). The box1 and box2 domains are conserved motifs within membrane-proximal regions of the type I cytokine receptors and are essential for recruitment and activation of JAKs. The membrane-proximal region of the EPOR, comprising the box1 domain and the flanking domain, has been shown to be required for EPOR association with JAK2 (18, 31, 32). Using a chimeric receptor which contains the extracellular and box1 domains of the EPOR and the box2 and carboxyl-terminal domains of the IL-2 receptor βc (a JAK1-associated subunit), Jiang et al. have indicated that the box1 domain of the EPOR specifies JAK2 activation but not JAK1 activation (18). In contrast, the box2 domain of the EPOR is not required for JAK2 association. Therefore, it is possible that JAK1 and JAK2 associate with different regions of the EPOR and that the box2 domain of the EPOR may be required for association with JAK1 in T3Cl-2-O cells, although the actual JAK1 binding site of the EPOR should be determined in the future. Alternatively, it seems possible that JAK1 and JAK2 compete for the box1 domain and its flanking domain of the EPOR to bind it. JAK1, but not JAK2, binds each EPOR subunit of the EPOR homodimer in most FVp-induced erythroleukemia cells. However, in T3Cl-2-O cells, JAK1 and JAK2 bind different subunits of the EPOR homodimer. This is concordant with the results that JAK2 tyrosine phosphorylation was not additionally induced by EPO stimulation in FVp-infected erythroblastoid and gp55-induced 1-2 cells in which JAK1 was constitutively tyrosine-phosphorylated and that the box1 domain and its flanking domain of the EPOR could be occupied with JAK1. T3Cl-2-O cells express an increased number of EPORs owing to the integration of the FVp F-SFFV long terminal repeat downstream of the promoter region of the EPOR gene (26). This integration might upregulate the EPOR and result in the constitutive activation of both JAK1 and JAK2 in this erythroleukemia cell line.

We showed that the DNA binding activity of STAT5 was not induced despite its constitutive tyrosine phosphorylation in the FVp gp55-EPOR signaling (Fig. 8A, B, and C). These results, in conjunction with the JAK1 activation in the gp55-EPOR signaling, suggest that the FVp gp55-EPOR and EPO-EPOR signaling use distinct pathways and that other known or unknown signaling molecules downstream of JAK1 are involved in the FVp gp55-EPOR signaling for cell proliferation. In this regard, it is interesting that some studies show no requirement of STAT5 for a mitogenic response to EPO. Myeloid cell-derived transfectants expressing a mutant EPOR with a carboxyl-terminal truncation and a point mutation (Y343F) can proliferate in response to EPO without tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT5 (38). Recently, Klingmuller et al. showed that EPO-dependent cell proliferation and erythroid differentiation are induced downstream of a mutant EPOR in which all eight cytosolic tyrosines except Y479 are mutated to phenylalanine, through a cascade involving recruitment of PI3-K and activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase, independent of STAT5 and the Shc/Grb2-adapter pathway (23). The cascade involving PI3-K and mitogen-activated protein kinase might be responsible for the mitogenic effects of FVp gp55.

We further observed that EPO stimulation of FVp-infected erythroblastoid cells readily induced both nuclear translocation and DNA binding of constitutively tyrosine-phosphorylated STAT5 in the cytoplasmic fraction (Fig. 9 and 10). The phosphorylation of a specific tyrosine residue(s) of STAT5 induced by EPO stimulation would be required for its nuclear translocation and DNA binding ability. Along this line, it is interesting that the transcriptional activities of STAT1, STAT3, and STAT5 are regulated by its serine phosphorylation. Dephosphorylation of serine phosphorylation of STAT3 with serine/threonine-specific phosphoprotein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) prevents the formation of complexes of DNA with STAT3 homodimers (58). Mutant STAT1 and STAT3 proteins in which serine at residue 727 is replaced by alanine impair maximal activation of IFN-γ- and IFN-α-induced transcription, respectively (51). Moreover, it has been reported that IL-2 induces two forms of tyrosine-phosphorylated STAT5, STAT5p1 and STAT5p2, which differ in their levels of phosphorylation on serine residues and their cellular localization (4). STAT5p2 is the predominant form accumulating in the nucleus after IL-2 stimulation. Serine/threonine kinase inhibitor H7 inhibits IL-2-induced generation and IL-2-mediated transcriptional activity of STAT5p2. The serine phosphorylation site(s) of STAT5 is not yet known, but there must be a site corresponding to Ser727 of STAT1 and STAT3 in STAT5. Thus, it seems possible that the phosphorylation of Ser727 of STAT5 by EPO stimulation may be capable of inducing nuclear translocation and DNA binding activity of STAT5 which is constitutively tyrosine phosphorylated by FVp gp55. To examine a possible role of EPO-induced serine phosphorylation in inducing DNA binding activity of STAT5, we treated the nuclear extract from the EPO-stimulated T3Cl-2-O cells with PP2A and performed EMSA. The PP2A treatment had no effect on STAT5 binding with the PRE (data not shown). However, other types of serine/threonine phosphatases and serine/threonine kinase inhibitor H7 should be tested, because their effects are sometimes cell type dependent. Our present experimental system may provide an appropriate model to investigate the relation between STAT5 phosphorylation and its nuclear translocation and transcriptional activity.

We observed that the STAT5 DNA binding activity was induced in an EPO-dependent manner even in growth factor-independent erythroleukemia cell lines expressing FVp gp55. This suggests that factor-independent erythroleukemia cells may retain some undefined responsiveness to EPO. Along this line, we found that activation of STAT5, in both tyrosine phosphorylation and DNA binding, correlated with EPO-induced erythroid differentiation of the mouse erythroleukemia cell line SKT6 (55a), although others showed that EPO-induced impaired STAT5 activation correlated with EPO-induced differentiation of TF-1 cells (7). Ahlers et al. (1) introduced FVp gp55 or EPO in erythroid progenitors in spleens and bone marrow of mice by retrovirus vectors and found that FVp gp55 promoted proliferation over differentiation of erythroid progenitors, whereas EPO resulted in induction of differentiation. The membrane glycoprotein FVp gp55 may function as a subunit structure of the EPOR rather than to mimic the EPO ligand.

Using EPO-dependent HCD57 cells, Ohashi et al. (34) reported that the DNA binding activity of STAT1 and STAT3 is activated by EPO stimulation and that both STATs are constitutively activated after infection of the cells with FVp. Our results, however, indicated that neither tyrosine phosphorylation (Fig. 7A and B) nor DNA binding activity (Fig. 8B, C, and D) of STAT1 and STAT3 was induced in HCD57 cells after EPO stimulation. The STAT5 DNA binding activity was induced solely in an EPO-dependent manner. This discrepancy probably reflects a clonal variation of the HCD57 cell line. A similar clonal variation of the STAT activation has been reported for the TF-1 cell line (38). Moreover, Ohashi et al. (35) recently reported that the DNA binding activity of STAT5 is induced by EPO stimulation in HCD57 cells. They also found that constitutive activation of STAT proteins was not detected in cells of the mouse erythroleukemia cell line MEL. Sawyer and Penta (41) recently described the association of JAK2 and STAT5 with the EPOR and activation of STAT5-like DNA binding activity by EPO in HCD57 cells. Penta and Sawyer (37) also reported that tyrosine phosphorylation and DNA binding activity of both STAT1 and STAT5 are induced by EPO stimulation in proerythroblasts from the spleens of mice infected with an anemic strain of Friend virus (FVa). The STAT1 activation observed in FVa-infected cells may partly explain the difference between proliferative stimuli induced by FVp gp55 and FVa gp55; FVp gp55 induces factor-independent cell growth of erythroid cells, whereas FVa gp55 induces proliferation of erythroid cells but retains their requirement for EPO (5, 19).

Constitutive activation of related JAKs and STATs in cells transformed by some retroviruses and their viral oncogenes has been reported (11, 30, 36, 57). JAK1/JAK3 and STAT3/STAT5 are activated by IL-2 in normal T cells, and these JAKs and STATs are constitutively activated after transformation of the cells by human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 (30). In erythroid cells, however, JAK2 and STAT5 were activated by EPO, but neither was constitutively activated after transformation by FVp or its viral oncogenic glycoprotein gp55. Recent reports have shown no activation of JAKs and/or STATs in Bcr-Abl transformation (6, 21), while another report has indicated activation of both JAKs and STATs (42). Thus, the activation of related JAKs and STATs may not be consistently associated with transformation by retroviruses and their viral oncogenes. Transformation or abnormal expansion of erythroid cells by FVp gp55 might be caused by the constitutive activation of JAK1 and some unidentified transcription factors. In vivo, however, EPO might have a synergistic effect on FVp-induced rapid splenomegaly by activating STAT5.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Mariko Nagayoshi and Hiroshi Amanuma (The Institute of Physical and Chemical Research) for the FVp stock and FVp-induced erythroleukemia cell lines, Sandra K. Ruscetti (National Cancer Institute) for the HCD57 cell line, Hiroshi Wakao (University of Tokyo) for an anti-STAT5 antiserum, Osamu Miura (Tokyo Medical and Dental University) for an anti-EPOR antiserum, Hideya Ohashi (Kirin Brewery Co., Tokyo, Japan) for the supply of recombinant human EPO, H. Wakao and Atsushi Miyajima (University of Tokyo) for helpful discussions, Harvey F. Lodish (Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Institute and Massachusetts Institute of Technology) for critical reading of the manuscript and helpful discussions, and S. Shirai-Yamashita, T. Kojima, and Y. Tomimori (Tokyo Medical and Dental University) for helpful assistance.

This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan, from the Ichiro Kanehara Foundation, from CREST (Core Research for Evolutional Science and Technology) of Japan Science and Technology Corporation, and from the Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahlers N, Hunt N, Just U, Laker C, Ostertag W, Nowock J. Selectable retrovirus vectors encoding Friend virus gp55 or erythropoietin induce polycythemia with different phenotypic expression and disease progression. J Virol. 1994;68:7235–7243. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.11.7235-7243.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aizawa S, Suda Y, Furuta Y, Yagi T, Takeda N, Watanabe N, Nagayoshi M, Ikawa Y. Env-derived gp55 gene of Friend spleen focus-forming virus specifically induces neoplastic proliferation of erythroid progenitor cells. EMBO J. 1990;9:2107–2116. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07379.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beadling C, Guschin D, Witthuhn B A, Ziemiecki A, Ihle J N, Kerr I M, Cantrell D A. Activation of JAK kinases and STAT proteins by interleukin-2 and interferon α, but not the T cell antigen receptor, in human T lymphocytes. EMBO J. 1994;13:5605–5615. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06898.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beadling C, Ng J, Babbage J W, Cantrell D A. Interleukin-2 activation of STAT5 requires the convergent action of tyrosine kinases and a serine/threonine kinase pathway distinct from the Raf1/ERK2 MAP kinase pathway. EMBO J. 1996;15:1902–1913. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ben-David Y, Bernstein A. Friend virus-induced erythroleukemia and the multistage nature of cancer. Cell. 1991;66:831–834. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90428-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carlesso N, Frank D A, Griffin D. Tyrosyl phosphorylation and DNA binding activity of signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT) proteins in hematopoietic cell lines transformed by Bcr/Abl. J Exp Med. 1996;183:811–820. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.3.811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chretien S, Varlet P, Verdier F, Gobert S, Cartron J-P, Gisselbrecht S, Mayeux P, Lacombe C. Erythropoietin-induced erythroid differentiation of the human erythroleukemia cell line TF-1 correlates with impaired STAT5 activation. EMBO J. 1996;15:4174–4181. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Damen J E, Mui A L-F, Puil L, Pawson T, Krystal G. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase associates, via its Src homology 2 domains, with the activated erythropoietin receptor. Blood. 1993;81:3204–3210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Damen J E, Liu L, Cutler R L, Krystal G. Erythropoietin stimulates the tyrosine phosphorylation of Shc and its association with Grb2 and a 145-Kd tyrosine phosphorylated protein. Blood. 1993;82:2296–2303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.D’Andrea A D, Lodish H F, Wong G G. Expression cloning of the murine erythropoietin receptor. Cell. 1989;57:277–285. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90965-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Danial N N, Pernis A, Rothman P B. Jak-STAT signaling induced by the v-abl oncogene. Science. 1995;269:1875–1877. doi: 10.1126/science.7569929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Darnell J E, Jr, Kerr I M, Stark G R. Jak-STAT pathways and transcriptional activation in response to IFNs and other extracellular signaling proteins. Science. 1994;264:1415–1421. doi: 10.1126/science.8197455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gouilleux F, Pallard C, Dusanter-Fourt I, Wakao H, Haldosen L-A, Norstedt G, Levy D, Groner B. Prolactin, growth hormone, erythropoietin and granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor induce MGF-Stat5 DNA binding activity. EMBO J. 1995;14:2005–2013. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07192.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.He T-C, Zhuang H, Jiang N, Waterfield M D, Wojchowski D M. Association of the p85 regulatory subunit of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase with an essential erythropoietin receptor subdomain. Blood. 1993;82:3530–3538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ihle J N. STATs: signal transducers and activators of transcription. Cell. 1996;84:331–334. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81277-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ikawa Y, Aida M, Inoue Y. Isolation and characterization of high and low differentiation-inducible Friend leukemia lines. Gann. 1976;67:767–770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ikuta K, Kina T, MacNeil I, Uchida N, Peault B, Chien Y-H, Weissman I L. A developmental switch in thymic lymphocyte maturation potential occurs at the level of hematopoietic stem cells. Cell. 1990;62:863–874. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90262-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang N, He T-C, Miyajima A, Wojchowski D M. The box1 domain of the erythropoietin receptor specifies Janus kinase 2 activation and functions mitogenically within an interleukin 2 β-receptor chimera. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:16472–16476. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.28.16472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson P, Benchimol S. Friend virus induced murine erythroleukaemia: the p53 locus. Cancer Surv. 1992;12:137–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnston J A, Kawamura M, Kirken R A, Chen Y-Q, Blake T B, Shibuya K, Ortaldo J R, McVicar D W, O’Shea J J. Phosphorylation and activation of the Jak-3 Janus kinase in response to interleukin-2. Nature. 1994;370:151–153. doi: 10.1038/370151a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kanwar V S, Witthuhn B, Campana D, Ihle J N. Lack of constitutive activation of Janus kinases and signal transduction and activation of transcription factors in Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 1996;87:4911–4912. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klingmuller U, Lorenz U, Cantley L C, Neel B G, Lodish H F. Specific recruitment of SH-PTP1 to the erythropoietin receptor causes inactivation of JAK2 and termination of proliferative signals. Cell. 1995;80:729–738. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90351-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klingmuller U, Wu H, Hsiao J G, Toker A, Duckworth B C, Cantley L C, Lodish H F. Identification of a novel pathway important for proliferation and differentiation of primary erythroid progenitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3016–3021. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kotenko S V, Izotova L S, Pollack B P, Muthukumaran G, Paukku K, Silvennoinen O, Ihle J N, Pestka S. Other kinases can substitute for Jak2 in signal transduction by interferon-γ. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:17174–17182. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.29.17174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krantz S B. Erythropoietin. Blood. 1991;77:419–434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lacombe C, Chretien S, Lemarchandel V, Mayeux P, Romeo P-H, Gisselbrecht S, Cartron J-P. Spleen focus-forming virus long terminal repeat insertional activation of the murine erythropoietin receptor gene in the T3Cl-2 Friend leukemia cell line. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:6952–6956. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leung S, Li X, Stark G R. STATs find that hanging together can be stimulating. Science. 1996;273:750–751. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5276.750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li J-P, D’Andrea A D, Lodish H F, Baltimore D. Activation of cell growth by binding of Friend spleen focus-forming virus gp55 glycoprotein to the erythropoietin receptor. Nature. 1990;343:762–764. doi: 10.1038/343762a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu L, Damen J E, Cutler R L, Krystal G. Multiple cytokines stimulate the binding of a common 145-kilodalton protein to Shc at the Grb2 recognition site of Shc. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:6926–6935. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.10.6926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Migone T-S, Lin J-X, Cereseto A, Mulloy J C, O’Shea J J, Franchini G, Leonard W J. Constitutively activated Jak-STAT pathway in T cells transformed with HTLV-I. Science. 1995;269:79–81. doi: 10.1126/science.7604283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miura O, Nakamura N, Ihle J N, Aoki N. Erythropoietin-dependent association of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase with tyrosine-phosphorylated erythropoietin receptor. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:614–620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miura O, Nakamura N, Quelle F W, Witthuhn B A, Ihle J N, Aoki N. Erythropoietin induces association of the JAK2 protein tyrosine kinase with the erythropoietin receptor in vivo. Blood. 1994;84:1501–1507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miyazaki T, Kawahara A, Fujii H, Nakagawa Y, Minami Y, Liu Z-J, Oishi I, Silvennoinen O, Witthuhn B A, Ihle J N, Taniguchi T. Functional activation of Jak1 and Jak3 by selective association with IL-2 receptor subunits. Science. 1994;266:1045–1047. doi: 10.1126/science.7973659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ohashi T, Masuda M, Ruscetti S K. Induction of sequence-specific DNA-binding factors by erythropoietin and the spleen focus-forming virus. Blood. 1995;85:1454–1462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ohashi, T., M. Masuda, and S. K. Ruscetti. 1997. Constitutive activation of Stat-related DNA-binding proteins in erythroid cells by the Friend spleen focus-forming virus. Leukemia 11(Suppl. 3):251–254. [PubMed]

- 36.Pallard C, Gouilleux F, Benit L, Cocault L, Souyri M, Levy D, Groner B, Gisselbrecht S, Dusanter-Fourt I. Thrombopoietin activates a STAT5-like factor in hematopoietic cells. EMBO J. 1995;14:2847–2856. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07284.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Penta K, Sawyer S T. Erythropoietin induces the tyrosine phosphorylation, nuclear translocation, and DNA binding of STAT1 and STAT5 in erythroid cells. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:31282–31287. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.52.31282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Quelle F W, Wang D, Nosaka T, Thierfelder W E, Stravopodis D, Weinstein Y, Ihle J N. Erythropoietin induces activation of Stat5 through association with specific tyrosines on the receptor that are not required for a mitogenic response. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:1622–1631. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.4.1622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ruscetti S K, Janesch N J, Chakraborti A, Sawyer S T, Hankins W D. Friend spleen focus-forming virus induces factor independence in an erythropoietin-dependent erythroleukemia cell line. J Virol. 1990;64:1057–1062. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.3.1057-1062.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sadowski H B, Gilman M Z. Cell-free activation of a DNA binding protein by epidermal growth factor. Nature. 1993;362:79–83. doi: 10.1038/362079a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sawyer S T, Penta K. Association of JAK2 and STAT5 with erythropoietin receptors. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:32430–32437. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.50.32430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shuai K, Halpern J, ten Hoeve J, Rao X, Sawyers C L. Constitutive activation of STAT5 by the BCR-ABL oncogene in chronic myelogenous leukemia. Oncogene. 1996;13:247–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sims S H, Cha Y, Romine M F, Gao P Q, Gottlieb K, Deisseroth A B. A novel interferon-inducible domain: structural and functional analysis of the human interferon regulatory factor 1 gene promoter. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:690–702. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.1.690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stahl N, Boulton T G, Farruggella T, Ip N Y, Davis S, Witthuhn B A, Quelle F W, Silvennoinen O, Barbieri G, Pellegrini S, Ihle J N, Yancopoulos G D. Association and activation of Jak-Tyk kinases by CNTF-LIF-OSM-IL-6 β receptor components. Science. 1994;263:92–95. doi: 10.1126/science.8272873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Taniguchi T. Cytokine signaling through nonreceptor protein tyrosine kinases. Science. 1995;26:251–255. doi: 10.1126/science.7716517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Velazquez L, Fellous M, Stark G R, Pellegrini S. A protein tyrosine kinase in the interferon α/β signaling pathway. Cell. 1992;70:313–322. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90105-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wagner B J, Hayes T E, Hoban C J, Cochran B H. The SIF binding element confers sis/PDGF inducibility onto the c-fos promoter. EMBO J. 1990;9:4477–4484. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07898.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wakao H, Gouilleux F, Groner B. Mammary gland factor (MGF) is a novel member of the cytokine regulated transcription factor gene family and confers the prolactin response. EMBO J. 1994;13:2182–2191. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06495.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wakao H, Harada N, Kitamura T, Mui A L-F, Miyajima A. Interleukin 2 and erythropoietin activate STAT5/MGF via distinct pathways. EMBO J. 1995;14:2527–2535. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07250.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang D, Stravopodis D, Teglund S, Kitazawa J, Ihle J N. Naturally occurring dominant negative variants of Stat5. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:6141–6148. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.11.6141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wen Z, Zhong Z, Darnell J E., Jr Maximal activation of transcription by Stat1 and Stat3 requires both tyrosine and serine phosphorylation. Cell. 1995;82:241–250. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90311-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Witthuhn B A, Quelle F W, Silvennoinen O, Yi T, Tang B, Miura O, Ihle J N. JAK2 associates with the erythropoietin receptor and is tyrosine phosphorylated and activated following stimulation with erythropoietin. Cell. 1993;74:227–236. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90414-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Witthuhn B A, Silvennoinen O, Miura O, Lai K S, Cwik C, Liu E T, Ihle J N. Involvement of the Jak-3 Janus kinase in signaling by interleukins 2 and 4 in lymphoid and myeloid cells. Nature. 1994;370:153–157. doi: 10.1038/370153a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yamamura Y, Noda M, Ikawa Y. Activated Ki-Ras complements erythropoietin signaling in CTLL-2 cells, inducing tyrosine phosphorylation of a 160-kDa protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:8866–8870. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.19.8866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yamamura, Y., H. Senda, M. Noda, and Y. Ikawa. 1997. Activation of the JAK1-STAT5 pathway by binding of the Friend virus gp55 glycoprotein to the erythropoietin receptor. Leukemia 11(Suppl. 3):432–434. [PubMed]

- 55a.Yamamura, Y., et al. Unpublished observation.

- 56.Yi T, Zhang J, Miura O, Ihle J N. Hematopoietic cell phosphatase associates with erythropoietin (Epo) receptor after Epo-induced receptor tyrosine phosphorylation: identification of potential binding sites. Blood. 1995;85:87–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yu C-L, Meyer D J, Campbell G S, Larner A C, Carter-Su C, Schwartz J, Jove R. Enhanced DNA-binding activity of a Stat3-related protein in cells transformed by the Src oncoprotein. Science. 1995;269:81–83. doi: 10.1126/science.7541555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang X, Blenis J, Li H-C, Schindler C, Chen-Kiang S. Requirement of serine phosphorylation for formation of STAT-promoter complexes. Science. 1995;267:1990–1994. doi: 10.1126/science.7701321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]