Abstract

Diffuse neonatal hemangiomatosis (DNH) is an infrequent condition characterized by the simultaneous occurrence of multiple cutaneous hemangiomas and the involvement of 3 or more organs. DNH is suspected when multiple hemangiomas are identified on the skin of the infant. Although it is benign in nature, DNH can lead to critical and life-threatening complications. Diagnosis primarily relies on clinical evaluation with a significant emphasis on imaging techniques. In this case report, we present an unusual pediatric case of diffuse infantile hemangioendothelioma, for which the investigative approach included ultrasound and CT scans. These imaging methods were instrumental in revealing the presence of lesions in the liver, thyroid, and brain, ultimately playing a pivotal role in making the diagnosis of DNH. A positive clinical and biological improvement was observed with corticosteroid treatment during a 3-month follow-up.

Keywords: Diffuse neonatal hemangiomatosis, infantile hepatic hemangioendothelioma, skin, liver, thyroid, brain, imaging

Introduction

Diffuse neonatal hemangiomatosis (DNH) is a rare condition characterized by onset in the neonatal period. It is non-malignant and distinguished by the presence of multiple cutaneous hemangiomas and the simultaneous involvement of 3 or more organs beyond the skin. The appearance of cutaneous hemangiomas may raise suspicion, leading to an investigation into potential visceral involvement.1,2 Lower gestational age and birthweight are associated with a higher risk of infantile hemangioma. Despite being a benign vascular tumor, DNH can lead to life-threatening complications, including conditions such as congestive heart failure, abdominal compartment syndrome, consumptive thrombocytopenia, and consumptive hypothyroidism. 3

Case Report

Our case is a boy born by spontaneous vaginal delivery with no signs of distress, weighing 3200 g. Following birth, numerous cutaneous lesions were recognized and diagnosed as multiple hemangiomas, no farther exploration was requested. Three months later he was admitted to our pediatric hospital due to recent abdominal distention and the appearance of jaundice associated with moderate tachypnea. His examination revealed large hepatomegaly, the liver was palpable 4 cm under the right costal margin with an enlargement of both right and left hepatic lobes, conjunction of cutaneous strawberry-like hemangiomas over the skin (Figure 1). Neurological examination revealed a hypotonic child without focal neurological deficits.

Figure 1.

Multiple cutaneous hemangiomas of the patient (black arrows).

The blood tests revealed several hematologic abnormalities, including moderate anemia and thrombocytopenia. Further biological tests uncovered elevated TSH levels (13 mU/L) along with low values of T3 (0.4 ng/ml), confirming the biological diagnosis of hypothyroidism. Liver function tests, including bilirubin (35 U/L), GGT (15 U/L), AST (78 U/L), ALT (91 U/L), and ALP (682 U/L), indicated increased levels of liver enzymes. Additionally, the biological investigation identified elevated levels of AFP (230 ng/ml), an uncommon finding but reported in some literature. There was no evidence of ABO or Rh incompatibility. Screenings for sepsis, TORCH, and metabolic disorders were mostly negative.

Abdominal ultrasound showed multifocal uniformly hypo-echoic mass ravishing most of the hepatic lobes (Figure 2). A quick US probe sweep of the thyroid revealed a clear homogenous hypotrophy of the gland (Figure 3) and a transfontanel US showed hydrocephalus with signs of meningeal bleed confirmed in CT scan (Figure 4). Given the unavailability of MRI, we completed the imaging exam with a contrast-enhanced abdominal CT revealing multiple hepatic lesions exhibiting peripheral ring enhancement on the portal phase (Figure 5).

Figure 2.

Abdominal US showing multifocal hypo-echoic mass ravishing most of the hepatic lobes (red arrows).

Figure 3.

Cervical US showing thyroid hypo-echoic nodules withing the gland (red arrows).

Figure 4.

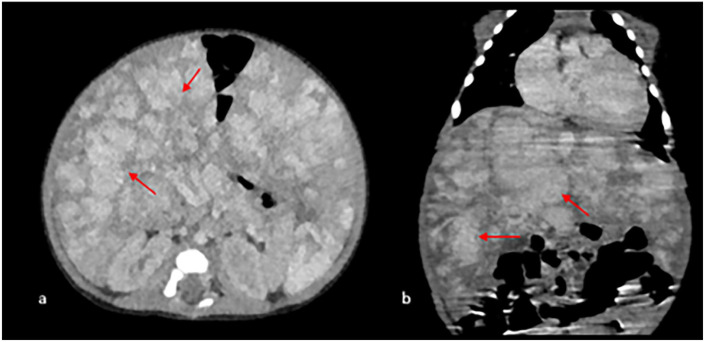

Axial (a) and coronal reconstruction (b) CT, showing hydrocephalus (red arrows) and meningeal bleed (black arrow).

Figure 5.

Axial (a) and coronal reconstruction (b) contrast-enhanced CT, showing countless hepatic enhanced lesions (red arrows).

Discussion

DNH is a rare but potentially fatal condition in neonates. Typically, the presence of multiplied hemangiomas on the skin has long been recognized as a marker of hepatic hemangiomas and should be systematically investigated by liver ultrasound.1,4 Historically, vascular lesions affecting multiple areas in infants have been classified under terms like “diffuse neonatal hemangiomatosis” and “benign neonatal hemangiomatosis.” In 1970, Holden and Alexander introduced 3 essential diagnostic criteria for identifying DNH; onset during the neonatal period, absence of malignancy indicators, and the involvement of 3 or more distinct organ systems. 5 Among these, the liver is frequently impacted, followed by the brain; which appear to be the case here, since the infant has shown a hemorrhagic meningeal bleed. Additional organs as the bowel, spleen, mesentery, heart, lung, and genitourinary system, may be affected but less frequently.

Despite the benign nature of the histology, the mortality rate associated with DNH ranges from 50% to 90%. 1 This high mortality is attributed to diverse complications, including congestive heart failure due to extensive arteriovenous shunting, liver failure, consumptive coagulopathy, and hemorrhaging. Characteristically, skin lesions manifest as red papules or nodules, measuring between 0.5 and 1.5 cm in size, with quantities varying from 10 to 100.1,2

Clinical and biological signs of DNH may include anemia, leukocytosis, thrombocytopenia, consumption coagulopathy, mildly abnormal liver function tests, and less frequently elevated serum AFP. 6 Hypothyroidism have also been reported due to increased activity of type 3 iodothyronine deiodinase within the tumor or a humoral thyrotropin-like factor secreted by the tumor. 3

The classic ultrasound appearance of hepatic hemangiomatosis is that of uniformly multifocal hypo-echoic masses. However, the findings may vary widely, with smaller hemangiomas appearing more homogeneous and larger hemangiomas exhibiting a more complex ultrasound appearance. 7 In our case the liver is invaded by multiple hypoechoic lesions resembling to the pattern seen in countless metastasis when they infects the lungs.

Cervical ultrasound should be conducted when there’s a disruption in the thyroid assessment, aiming to identify potential thyroid-related concerns. Additionally, transfontanel ultrasonography could offer valuable assistance in identifying cerebral localization, intracranial hemorrhage and hydrocephalus particularly if the infant exhibits neurological symptoms. In our case, cervical ultrasonography revealed several thyroid nodules, leading to the diagnosis of thyroid hemangiomas.

A contrast-enhanced CT scan demonstrates typical peripheral, nodular distribution of contrast enhancement on the early phases followed by gradual centripetal filling-in of the contrast. MRI helps to discriminate between other vascular tumors or malformations and to correctly classify lesions in the brain or in other vital organs. 7 In few cases, prenatal ultrasound with color Doppler may facilitate the early diagnosis of DNH and help through the early referral to specialized centers for appropriate treatment. 8

The spectrum of severity associated with diffuse hepatocutaneous hemangiomatosis varies widely, ranging from asymptomatic cases to fatalities. Identifying patients at a higher risk of developing such lesions and determining the specific risk factors that contribute to a more aggressive manifestation in some cases is of paramount importance. 9

Treatment with high-dose corticosteroids and interferon alfa-2b has been shown to cause various degree of hemangiomas regression. Nevertheless, these therapies may be associated with severe adverse reactions. 7 In resistant cases, hepatic artery embolization is a possible treatment. Recently, propranolol has been introduced as an effective treatment for cutaneous infantile hemangiomatosis as a primary treatment and in patients with poor response to steroids. Several recent cases involving an excellent response of DHN to propranol. 10 In our case, the infant showed a positive clinical response to steroid treatment, with a gradual reduction in dyspnea and jaundice, and a restoration of normal liver function tests.

Conclusion

Patients with multiple cutaneous hemangiomas are not always DNH, but they should be systematically investigated to look for more involvement organs beyond the skin. Our case is unusual in its presentation with thyroid localization, an elevation of alpha fetoprotein level, and a good evolution under corticosteroids. As by today there is no formal guidelines for the treat6ment of these conditions, and the therapeutic strategies implemented vary widely from simple observation to medical, radiological, and surgical interventions in the prism of multidisciplinary teams.

Footnotes

Abbreviation: IHH: Infantile hepatic hemangioendothelioma

DNH: Diffuse neonatal hemangiomatosis

TSH: Thyroid stimulating hormone

ALT: Alanine transaminase

AST: Aspartate transaminase

ALP: Alkaline phoshphatase

GGT: Gamma-glutamyltransferase

AFP: Alpha fetoprotein

US: Ultrasound

CT: Computed tomography

MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging

Author Contributions: FZEM: contributed to conception and design; contributed to acquisition; drafted manuscript; critically revised manuscript; gave final approval; agrees to be accountable for all aspects of work ensuring itegrity and accuracy.

ZEY: contributed to design; contributed to analysis; drafted manuscript; critically revised manuscript; Select item; agrees to be accountable for all aspects of work ensuring itegrity and accuracy.

MIH: contributed to design; contributed to interpretation; drafted manuscript; critically revised manuscript; Select item; agrees to be accountable for all aspects of work ensuring itegrity and accuracy.

NL: contributed to conception; contributed to interpretation; drafted manuscript; critically revised manuscript; gave final approval; agrees to be accountable for all aspects of work ensuring itegrity and accuracy.

NA: contributed to conception; contributed to acquisition and interpretation; Select item; Select item; gave final approval; agrees to be accountable for all aspects of work ensuring itegrity and accuracy.

LC: contributed to conception; contributed to analysis and interpretation; Select item; critically revised manuscript; gave final approval; agrees to be accountable for all aspects of work ensuring itegrity and accuracy.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics Approval: Our institution does not require ethical approval for reporting individual cases or case series.

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from a legally authorized representative(s) for anonymized patient information to be published in this article.

ORCID iDs: Fatima Zahrae El Mansoury  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6443-3217

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6443-3217

Zakia El Yousfi  https://orcid.org/0009-0005-0841-5475

https://orcid.org/0009-0005-0841-5475

Najlae Lrhorfi  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0300-6526

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0300-6526

References

- 1. Morakote W, Katanyuwong K, Pruksachatkun C, et al. Diffuse neonatal hemangiomatosis with a single atypical cutaneous hemangioma. Radiol Case Rep. 2022;17:2759-2764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rodríguez Bandera AI, Sebaratnam DF, Wargon O, Wong LCF. Infantile hemangioma. Part 1: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical presentation and assessment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1379-1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Acharya S, Giri PP, Das D, Ghosh A. Hepatic Hemangioendothelioma: A rare cause of congenital hypothyroidism. Indian J Pediatr. 2019;86:306-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Diop K, Ndiaye M, Ndiaye MT, et al. Diffuse miliary hemangiomatosis with hepatic Diff use miliary hemangiomatosis with hepatic involvement in an infant in Dakar involvement in an infant in Dakar Case Report. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Glick ZR, Frieden IJ, Garzon MC, Mully TW, Drolet BA. Diffuse neonatal hemangiomatosis: an evidence-based review of case reports in the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:898-903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Patiroglu T, Sarici D, Unal E, et al. Cerebellar hemangioblastoma associated with diffuse neonatal hemangiomatosis in an infant. Childs Nerv Syst. 2012;28:1801-1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Iacobas I, Phung TL, Adams DM, et al. Guidance Document for Hepatic Hemangioma (Infantile and congenital) evaluation and monitoring. J Pediatr. 2018;203:294-300.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schwickert A, Seeger KH, Rancourt RC, Henrich W. Prenatally detected umbilical cord tumor as a sign of diffuse neonatal hemangiomatosis. J Clin Ultrasound. 2019;47:366-368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Velayos M, Estefanía-Fernández K, Muñoz-Serrano AJ, et al. Diffuse hepatocutaneous hemangiomatosis: an unusual presentation. Cir Pediatr. 2022;35:99-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Okuno T, Tokuriki S, Yoshino T, Tanaka N, Ohshima Y. Diffuse neonatal hemangiomatosis in a very low-birthweight infant treated with erythropoietin. Pediatr Int. 2015;57:e34-e36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]