Abstract

Acyl-homoserine lactones (AHLs), mediating pivotal physiological activities through quorum sensing (QS), have conventionally been considered limited to Gram-negative bacteria. However, few reports on the existence of AHLs in Gram-positive bacteria have questioned this conception. Streptomyces, as Gram-positive bacteria already utilizing a lactone-based QS molecule (i.e., gamma-butyrolactones), are yet to be explored for producing AHLs, considering their metabolic capacity and physiological distinction. In this regard, our study examined the potential production of AHLs within Streptomyces by deploying HPLC-MS/MS methods, which resulted in the discovery of multiple AHL productions by S. griseus, S. lavendulae FRI-5, S. clavuligerus, S. nodosus, S. lividans, and S. coelicolor A3(2). Each of these Streptomyces species possesses a combination of AHLs of different size ranges, possibly due to their distinct properties and regulatory roles. In light of additional lactone molecules, we further confirm that AHL- and GBL-synthases (i.e., LuxI and AfsA enzyme families, respectively) and their receptors (i.e., LuxR and ArpA) are evolutionarily distinct. To this end, we searched for the components of the AHL signaling circuit, i.e., AHL synthases and receptors, in the Streptomyces genus, and we have identified multiple potential LuxI and LuxR homologs in all 2,336 Streptomyces species included in this study. The 6 Streptomyces of interest in this study also had at least 4 LuxI homologs and 97 LuxR homologs. In conclusion, AHLs and associated gene regulatory systems could be more widespread within the prokaryotic realm than previously believed, potentially contributing to the control of secondary metabolites (e.g., antibiotics) and their complex life cycle, which leads to substantial industrial and clinical applications.

Keywords: Streptomyces, acyl-homoserine lactone, gamma-butyrolactone, quorum sensing, differentiation, autoinducer

1. Introduction

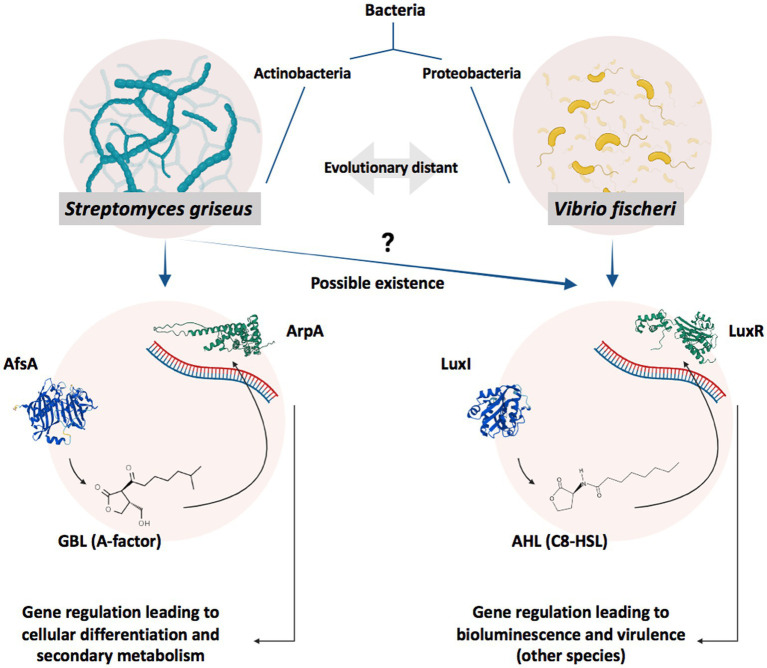

Streptomyces species, as filamentous Gram-positive bacteria, are acknowledged for their advanced secondary metabolism and cellular differentiation entangled with complex regulatory circuitry, which revolves around hormone-like signaling molecules known as gamma-butyrolactones (GBLs) (Khokhlov et al., 1967; Horinouchi and Beppu, 1994; Kong et al., 2019; Jose et al., 2021). GBL-based regulatory circuits follow quorum sensing (QS) principles of cooperative population-dependent gene expression and share an architecture with QS systems based on acyl-homoserine lactones (abbreviated as Acyl-HSLs or AHLs); hence, they are considered to be analogous to the latter (Figure 1; Polkade et al., 2016; Barreales et al., 2020).

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of GBL- and AHL-based gene regulation systems. GBLs and AHLs, produced by AfsA and LuxI, act as autoinducers in Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria to regulate the expression of specific genes by affecting their relevant receptors, ArpA and LuxR, respectively, when reaching a specific concentration (reflection of the cell density/population) in a process known as QS (Polkade et al., 2016). A specific level of bacterial population and, subsequently, autoinducer concentration in V. fischeri leads to bioluminescence (Engebrecht et al., 1983), while in Streptomyces species, it activates cellular differentiation or antibiotic production (Takano, 2006). Bacterial species possessing AfsA/ArpA and LuxI/LuxR protein families are evolutionary distant; however, AfsA and ArpA protein families are considered analogs to LuxI and LuxR protein families, respectively. Regarding the signaling molecules, GBLs and AHLs share structural similarities. Both molecule families possess a gamma-lactone moiety combined with a tail of the carbon chain; however, GBLs usually possess an extra-short branch on the lactone ring while missing the amide bond in the carbon tail. It is worth noting that more structurally different GBLs (Misaki et al., 2022) and AHLs (Schaefer et al., 2008) have also been discovered while all sharing the lactone moiety.

AHLs were primarily extracted from Gram-negative bacteria as autoinducers running QS gene regulation circuitry (Eberhard et al., 1981). Historically, extensive reports on the existence of AHLs in various Gram-negative bacterial taxa, such as Proteobacteria (Fuqua and Greenberg, 2002), Cyanobacteria (Sharif et al., 2008), and Bacteroidetes (Huang et al., 2008; Twigg et al., 2014), have led to the general assumption that AHLs and related cellular components (i.e., synthases and receptors) are exclusive to these species (Swift et al., 1994; Parsek and Greenberg, 2000; Miller and Bassler, 2001). However, three noticeable studies (Biswa and Doble, 2013; Bose et al., 2017; de Moura et al., 2021) that reported the production of AHLs in some Gram-positive bacteria undermine this broadly accepted view. Following these findings, the discovery of AHL synthases and receptors’ homologs in a limited number of Streptomyces species further justifies the quest for AHLs in these species (Santos et al., 2012). Moreover, due to the industrial and medical significance of Streptomyces (Khushboo et al., 2022), studying lactone-based signaling circuits and molecules, their evolutionary origin, and the existence of additional relevant circuits and molecules (e.g., AHLs and related circuits) would be of importance. Furthermore, the presence of novel gene regulation mechanisms in Streptomyces as complex prokaryotes demonstrating multicellular behaviors (see Flärdh and Buttner, 2009) will be notable from an evolutionary point of view.

In this study, we have demonstrated the production of AHLs by six well-known Streptomyces species, including S. griseus, S. lavendulae FRI-5, S. clavuligerus, S. nodosus, S. lividans, and S. coelicolor A3(2), via the chromatography/mass-spectrometry method. Afterward, we investigated the presence of AHL synthases homologous to the LuxI enzyme family and AHL receptors homologous to the LuxR receptor family in Streptomyces via in silico methods.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Culture conditions and preparation of crude extracts

S. clavuligerus DSM 738, S. griseus DSM 40236, and S. nodosus DSM 40109, all obtained from Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen, Germany, S. lavendulae FRI-5 MAFF 116015, and S. lividans TK-64 MAFF 304033, obtained from the National Food Research Institute, Tsukuba, Japan, and S. coelicolor A3(2), obtained from the John Innes Centre, UK, were used as standard strains in all experiments. The strains were cultured on ISP2 agar as sporulation medium consisting of (g/L): malt extract 10, yeast extract 4, glucose 4, CaCO3 2, and agar 18, at pH 7 ± 0.1, and incubated for 8–14 days at 28°C. The same medium was also used as the seeding and fermentation medium after excluding CaCO3 and agar. Using ventilation flasks under the mentioned operating conditions prepares the aeration rate of 1 vvm, preventing oxygen limitation during microorganism growth. To this end, for seed culture, ventilation flasks type F1 (modified 250-Erlenmeyer) (Amoabediny and Büchs, 2007) containing 25 mL of ISP2 medium were inoculated with 0.1 mL of spore suspensions of each strain (ca. 107–108 spores/ml) and incubated for 72 h, at 28°C and agitated at 220 rpm. The seed culture was then inoculated (5% v/v) into identical ventilation flasks containing 25 mL of fermentation medium and incubated in the same growth conditions as the previous step. After cultivation, the fermentation broth of each strain was acidified to pH 3 by concentrated HCl and centrifuged at 6000 g for 15 min. The supernatant was extracted twice with a 5-fold volume of ethyl acetate. For each strain, 3 liters of fermentation medium were used to prepare the crude extract. The solvent layer was evaporated to dryness, re-dissolved in 200 μL of methanol, filtered via 0.22 μm Nylon syringe filters, and finally subjected to chromatography and HPLC-MS/MS analysis. The fresh medium was also extracted using the same method and used as the control group.

2.2. Chromatography/mass-spectrometry analysis

HPLC-MS/MS setup consisted of an Agilent ZORBAX HPLC system (SB-C18 column) coupled with an Agilent G6410 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer and an ESI interface. The adjustments of the HPLC setup and the protocol were as follows: a sonicated, degassed, and filtered mobile phase of Acetonitrile:Water (0.1% Formic Acid) consists of 20 min 45% acetonitrile, 90% acetonitrile for 3 min, 7 min 100% acetonitrile, 10 min 45% acetonitrile with a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min. The column temperature was set at 25°C, and 20 μL of the sample was subjected to the instrument via an auto-sampler. Mass spectrometer adjustments were as follows: capillary voltage: 4500 V, mass range: 120–450 amu, Dwell time: 500 ms, fragmentor voltage: 120 V, collision energy: 7. Nine ultra-pure AHLs, including N-butanoyl-L-homoserine lactone (C4-HSL), N-hexanoyl-L-homoserine lactone (C6-HSL), N-(3-oxo-hexanoyl)-L-homoserine lactone (Oxo-C6-HSL), N-heptanoyl-L-homoserine lactone (C7-HSL), N-octanoyl-L-homoserine lactone (C8-HSL), N-(3-oxo-octanoyl)-L-homoserine lactone (Oxo-C8-HSL), N-decanoyl-L-homoserine lactone (C10-HSL), N-dodecanoyl-L-homoserine lactone (C12-HSL), and N-(3-oxo-dodecanoyl)-L-homoserine lactone (Oxo-C12-HSL), purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, were used as standards to determine the characteristic daughter ions, which were found to be at m/z 102, reflecting the lactone ring, similar to previous reports (Morin et al., 2003; Fekete et al., 2007; Bose et al., 2017). Accordingly, each sample was evaluated by the precursor ion method screening for AHL-characteristic daughter ion at m/z 102. Afterward, the total ion chromatogram (TIC) of each bacterial medium extract was screened for major masses, and each mass was depicted independently through an extraction chromatogram (EIC). To further confirm each mass to be an AHL, the concurrent existence of at least one other daughter ion at m/z 56, 74, or 84 was evaluated via the production method (Rodrigues et al., 2022). All the results were analyzed using Agilent MassHunter Qualitative Analysis.

2.3. In silico studies

2.3.1. Comparison of the model protein components of AHL- and GBL-signaling circuits

The molecular function ontology of LuxI from V. fischeri and AfsA from S. griseus, as the most investigated AHL- and GBL-synthases model proteins, and LuxR from V. fischeri and ArpA from S. griseus as the model receptors of AHL and GBL were retrieved from Gene Ontology (GO1, Ashburner et al., 2000). The enzymatic reactions of LuxI and AfsA were obtained from Rhea2 (Alcántara et al., 2012). Three-dimensional models of the proteins were created using the AlphaFold engine (Jumper et al., 2021; Varadi et al., 2022) and retrieved from EMBL-EBI.3

To obtain the conserved regions and residues, LuxI (Accession Number: P12747) and LuxR (Accession Number: P12746) of V. fischeri and AfsA (Accession Number: P18394) and ArpA (Accession Number: Q9ZN78) of S. griseus, in addition to nine homologs of each protein, were retrieved from the UniProt database. Multiple sequence alignment (MSA) of the retrieved sequences was performed using the ClustalW algorithm (Thompson et al., 1994) on the MEGAx platform (Tamura et al., 2021). Jalview (Version 2, Waterhouse et al., 2009) was used for illustrative purposes and further analysis of the aligned sequences. The molecular function ontology, enzymatic reactions, three-dimensional structure, protein sequence, and conserved regions of these proteins were compared to evaluate their similarity and status of homology.

2.3.2. Investigating the existence of LuxI and LuxR homologs in Streptomyces

LuxI and LuxR from V. fischeri as model proteins were checked against the non-redundant protein sequence database of Streptomyces via protein–protein BLAST (default parameters) to assess the existence of potential LuxI and LuxR homologs in this genus. In order to further evaluate the existence of AHL synthases and receptors, a search for these proteins based on protein models was also conducted. InterPro and KEGG databases were searched for the relevant Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) for AHL synthases homologous to LuxI and AHL receptors homologous to LuxR. HMMs were evaluated for their specificity, and only the specific models were used for further analysis (Supplementary material 1). HMMs for AHL synthases and AHL receptors were concatenated independently. A total of 3,313 Streptomyces species genomes curated in RefSeq were retrieved from the NCBI Genome database.4 Nucleotide sequences were converted into amino acid sequences using the Prodigal program. HMMs were searched against the sequence database locally using the HMMsearch program. The data were filtered for E-value <10−5 (significant hits), and in the case of the recognition of a single target by multiple models, the hit with a lower E-value was selected. Duplicate species were eliminated based on the highest values of LuxI and LuxR copy number multiplication, which resulted in 2336 unique species. It is worth noting that S. lividans TK64 genome did not exist in the Streptomyces genome database and S. lividans TK24, a close strain, was selected for further in-silico analyses to investigate the presence of LuxI and LuxR homologs.

3. Results

3.1. Streptomyces species produce AHL

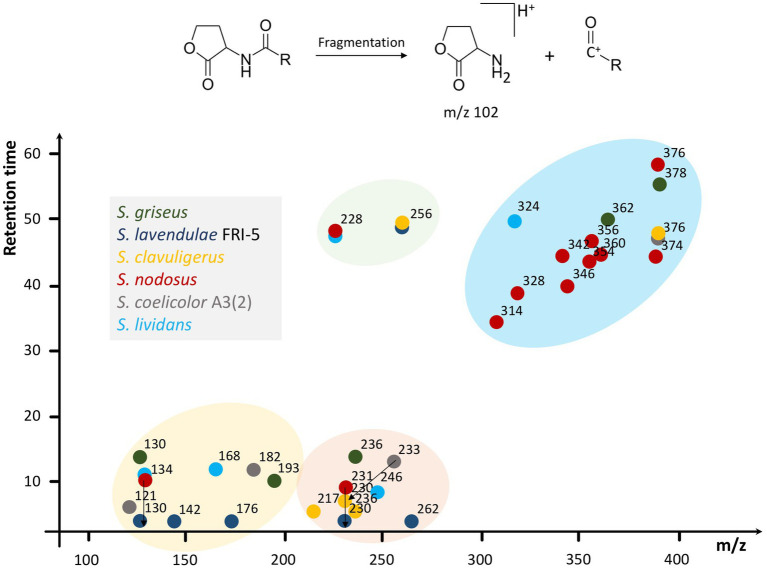

By analyzing the standard AHLs, the characteristic daughter ion of this molecular family was determined to be m/z 102. Afterward, the crude extracts of Streptomyces were primarily analyzed for the existence of AHLs by the characteristic m/z 102 daughter ion and then confirmed by other possible daughter ions. Various AHLs were found to be produced by the six Streptomyces of interest in this study (Figure 2). In this regard, by considering the significant peaks and comparison of EICs between samples and the control group, the profile of AHL (M + H)+ produced by each Streptomyces was as follows: S. griseus: m/z 130, 193, 236, 362, and 378, S. lavendulae FRI-5: m/z 130, 142, 176, 230, 256, and 262, S. clavuligerus: m/z 230, 256, and 376, S. nodosus: m/z 134, 228, 231, 314, 328, 342, 346, 354, 356, 360, 374, and 376, S. coelicolor A3(2): m/z 121, 182, 233, and 376, and S. lividans TK-64: m/z 134, 168, 228, 246, and 324. These compounds were further confirmed by the concurrent existence of at least one daughter ion at m/z 56, 74, or 84 via a production method.

Figure 2.

Schematic illustration of various AHLs found in six Streptomyces species. Multiple compounds found in Streptomyces species via HPLC-MS/MS are summarized based on m/z and retention time in a dot-plot and then clustered according to the parameters to depict the AHL distribution and prevalence regarding their properties. In this regard, four different clusters have appeared. S. lavendulae FRI-5 and S. clavuligerus do not participate in the yellow and blue clusters, respectively. Furthermore, the green cluster, containing m/z 228 and 256, lacks components from S. griseus and S. coelicolor A3(2). In addition, 3 m/z ranges of 100–200, 200–300, and 300–400 are evident, which contain AHLs from at least five Streptomyces species considered in this study. Original EICs are provided in Supplementary material 2. Different species of Streptomyces are represented by colors.

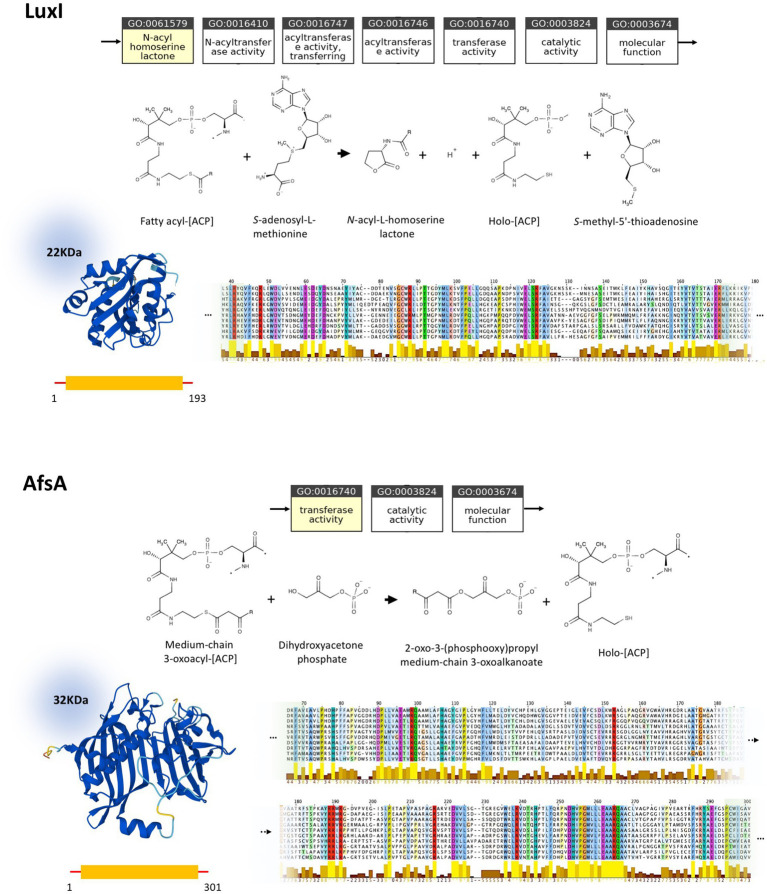

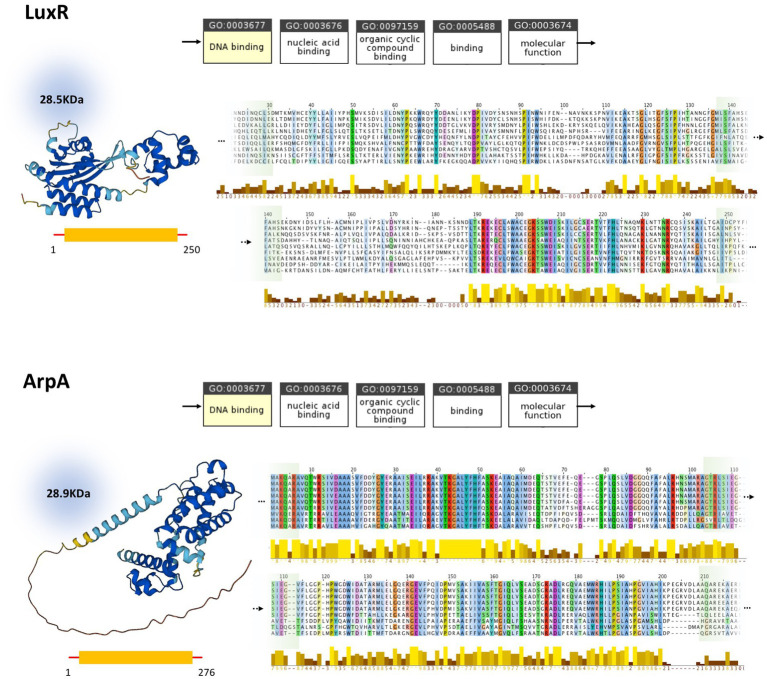

3.2. LuxI and AfsA enzyme families are not homologs

In silico studies investigating the properties of LuxI/LuxR and AfsA/ArpA protein families and their conserved regions, are conducted to assess the status of homology between these protein families. Despite the analogous function of LuxI and AfsA and that of LuxR and ArpA, their close homology could be ruled out based on our current knowledge (Figure 3). According to the ontology of LuxI and AfsA, both enzymes similarly possess transferase activity. Considering the enzymes’ catalytic reactions, in both reactions, the acyl chain originating from the fatty acid-[ACP] is transferred to the other substrate. However, the substrates of LuxI and AfsA are different, as the former is S-adenosyl-L-methionine and the latter is dihydroxyacetone phosphate. Consequently, these enzymes produce different products. AHLs are the product of LuxI, and AfsA produces GBLs. Moreover, the enzymatic reaction of lactone ring formation differs in both enzyme families. The lactone ring in AHLs is formed within the S-adenosyl-L-methionine, and then the fatty acid is bound to the ring acting as the acyl chain, not participating in the lactone ring formation, whereas the reaction of dihydroxyacetone phosphate and fatty acid-[ACP] leads to the formation of the lactone ring in GBLs. In addition, the structure and sequence of LuxI and AfsA were evaluated to assess the possibility of their homology. The sizes of the LuxI and AfsA are 22 and 32 KDa, respectively, and the length of the amino acid sequences are 193 and 301, respectively, which are significantly different. The three-dimensional structure of LuxI and AfsA, as evident in Figure 3, shows no remarkable similarities. Moreover, MSA is conducted to obtain the conserved amino acids of the LuxI and AfsA enzyme families. No similarity in the conserved amino acids of these enzyme families could be found, ruling out the possibility of common motifs responsible for the production of lactone molecules, according to previous studies (Hanzelka et al., 1997; Hsiao et al., 2007). Regarding the comparison of LuxR and ArpA receptor families, both protein families possess a similar molecular function, amino acid sequence length, and molecular weight; however, they are different in their three-dimensional structure and the conserved residues and regions obtained by MSA (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Comparison of LuxI (P12747) and AfsA (P18394) and their homologs. Molecular function ontology, catalytic activity, physical properties, and conserved regions of LuxI and AfsA are demonstrated at the top and bottom, respectively. Both LuxI and AfsA possess transferase activity and share fatty-acid-[ACP] as a substrate, while having a different second substrate. Moreover, these proteins are different in size and topology, as evident in their molecular weight, amino acid sequence length, and three-dimensional structure. LuxI and AfsA enzyme families possess different conserved residues and regions, according to the MSA. The complete MSA is provided in Supplementary material 3.

Figure 4.

Comparison of LuxR (P12746) and ArpA (Q9ZN78) and homologs. Molecular function ontology, physical properties, and conserved regions of LuxR and ArpA are demonstrated at the top and bottom, respectively. While possessing similar molecular function, molecular weight, and amino acid sequence length, these proteins are different in their three-dimensional structure and the conserved regions obtained by MSA. The full version of MSA is provided in Supplementary material 3.

3.3. Potential LuxI and LuxR homologs can be found in Streptomyces

The Streptomyces non-redundant protein sequence database has been examined for potential homologs of LuxI. Four potential homologs of LuxI were found in Streptomyces (GGY17999.1, WP_161252959.1, WP_208615587.1, and KOX59212.1) with an E-value of maximum 7e-26 and identity and query coverage of at least 35.03 and 84%, respectively (full data are accessible in Supplementary material 1). The sequence range of these proteins was from 191 to 293 amino acids, similar to that of LuxI (190 amino acids). Upon investigation of their function and conserved regions through Interpro, these proteins are annotated as acyltransferase and possess conserved regions found in autoinducer synthases like LuxI. The Streptomyces non-redundant protein sequence database has also been evaluated for the existence of potential LuxR homologs via protein–protein BLAST. In contrast to the limited number of hits in the search for LuxI, BLAST of LuxR against the Streptomyces proteins resulted in 153 hits with 109 significant hits (E-value<0.01) from 70 unique Streptomyces species with identity and query coverage of a maximum of 54.9 and 48% (full data are accessible in Supplementary material 1). These proteins were mostly annotated as “response regulator transcription factor,” “LuxR family regulator,” “DNA-binding response regulator,” and “response regulator.” The sequence range of these proteins was from 66 to 482 amino acids. While some potential LuxI and LuxR homologs were found in some Streptomyces species, the proteins were limited to a handful of Streptomyces species, despite the high abundance of species in this genus. In addition, species examined in this study (except for LuxR in S. griseus) could not be found through this method. Moreover, considering the variations in size of the proteins and their significant difference in size compared to LuxR while demonstrating relatively low query coverage and identity, these results could not be seen as satisfactory. To this end, further studies were conducted using LuxI- and LuxR-specific HMMs.

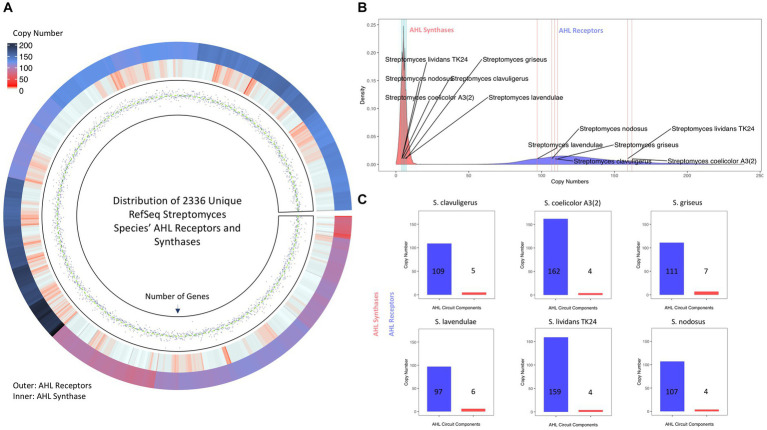

Interestingly, screening of the Streptomyces proteome for LuxI and LuxR homologs via HMMsearch yielded multiple hits (Figure 5A). Except for S. abikoensis (no hits in HMMsearch for LuxI homologs) and S. mashuensis (borderline E-value of 9.7e-5), all 2,336 unique Streptomyces species evaluated in this study possessed at least one potential AHL synthase homologous to LuxI, and all these species harbor at least five AHL receptor homologous to LuxR. The copy number of LuxR homologs was significantly higher than that of LuxI homologs. The maximum copy number of LuxI with 17 copy numbers was found in S. sp. NBC_00051, and that of LuxR homologs was found in S. albicerus with 239 copy numbers. Thirty-eight species possessed only one copy of LuxI, and the minimum copy number of LuxR was five found in S. cinereus. LuxI and LuxR homologs were also found in the six Streptomyces of interest evaluated for AHLs in this study. It is worth noting that subspecies S. lividans TK-64 did not exist in the Streptomyces genomes retrieved from NCBI, and other subspecies of S. lividans were considered for the analyses. The copy number of AHL synthases (i.e., LuxI homologs) was between four and seven, around the median (x̃=5) and average (x̄≈5.3) of these proteins in Streptomyces species (Figure 5B). On the other hand, except for S. nodosus, S. griseus, and S. clavuligerus, which resided around the median (x̃=123) and average (x̄=126.6) of copy numbers, S. lividans TK24 and S coelicolor A3(2) possessed more and S. lavendulae harbored fewer LuxR homologs (Figures 5B,C).

Figure 5.

AHL synthases (i.e., LuxI homologs) and AHL receptors (i.e., LuxR homologs) in Streptomyces species. (A) Circos Heatmap of AHL synthases (inner circle) and AHL receptors (outer circle) found in 2336 unique Streptomyces species and points track of number of genes. (B) Density plot demonstration of copy numbers of AHL synthases (red) and AHL receptors (blue). The LuxI and LuxR copy numbers of six Streptomyces of interest are indexed on each density plot. (C) The copy number of AHL synthases (red) and AHL receptors (blue) in the six Streptomyces of interest in this study. The data for HMMsearch and protein copy numbers are provided in Supplementary material 1.

4. Discussion

Gene regulatory circuits are of great interest due to their evolutionary, clinical, and industrial significance. Streptomyces, as Gram-positive bacteria, utilize GBL-based gene regulatory circuits to control their noticeable secondary metabolism (e.g., production of antibiotics) and cellular differentiation (Du et al., 2011; Mingyar et al., 2015; Barreales et al., 2020). Notably, GBLs have been only found in Streptomyces and are the sole lactone-based autoinducers in these species. On the other hand, AHLs, structurally similar molecules that also take on similar roles, are explicitly attributed to Gram-negative bacteria such as V. fischeri (Winson et al., 1995). GBL- and AHL-based gene regulatory circuits also share a common architecture and, along with their components (i.e., synthases and receptors), are considered analogous to each other (Figure 1). This study revealed that while the LuxI and AfsA enzyme families synthesize similar molecules and the LuxR and ArpA receptor families regulate gene expression in response to structurally similar molecules, each protein family has distinct protein structures, amino acid sequences, and conserved regions. Hence, in the absence of an evolutionary relationship between GBLs and AHL circuits, we wondered whether Streptomyces possessed AHLs and relevant components.

We found several AHLs produced by Streptomyces species, S. griseus, S. lavendulae FRI-5, S. clavuligerus, S. nodosus, S. lividans, and S. coelicolor A3(2), as Gram-positive bacteria, in addition to GBLs. While some AHLs (i.e., m/z 134, 228, 230, 256, and 376) were common between certain Streptomyces, each species demonstrated a unique AHL profile. The potential AHL compounds could be seen in four clusters when plotted by their m/z and retention time (Figure 2). Each cluster consists of AHLs from at least four Streptomyces species. Moreover, all species possessed at least one compound in the range of m/z 100–200, 200–300, and 300–400, except for S. lavendulae FRI-5 and S. clavuligerus, lacking any in the first and third range, respectively. The diversity of AHLs from different size ranges may be due to distinct properties of AHLs within each range and their specific physiological roles, which requires Streptomyces to possess a set of AHLs with different sizes. For instance, while AHLs with shorter acyl chains (e.g., 3-oxo-C6-HSL) can diffuse passively across the membrane, those with longer and more hydrophobic acyl chains might concentrate in lipid bilayers or require efflux pumps for their accelerated transport (Fuqua et al., 2001; Fuqua and Greenberg, 2002). Moreover, properties of the acyl chain, such as its length, provide specificity to QS systems (Fuqua et al., 2001). Therefore, various AHLs from different ranges might facilitate the regulation of multiple independent gene expressions in a specific species or intra-species and intra-kingdom communications (Shiner et al., 2005; Feng et al., 2014). On the other hand, multiple AHLs and relevant circuitry may also interactively regulate common target genes (Winson et al., 1995).

Based on the mass-spectrometry analyses of standard AHLs conducted here and data available in other reports (Rodrigues et al., 2022), the chemical structure of some AHLs could be predicted. For instance, a molecular ion peak at m/z 256 in S. lavendulae FRI-5 and S. clavuligerus could be predicted as C10-HSL. Moreover, m/z 228 found in S. nodosus and S. lividans and m/z 324 in S. lividans match C8-HSL and Oxo-C14:1-HSL, respectively. However, further studies such as nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) analysis are strongly suggested to illuminate the chemical structure of other masses, as they may not consist of a simple acyl chain, such as p-coumaroyl homoserine lactone (Schaefer et al., 2008).

In light of the production of AHLs by Streptomyces, these species were evaluated for harboring LuxI and LuxR homologs to further complete the scheme of AHL signaling circuits in Streptomyces. The protein–protein BLAST of V. fischeri’s LuxI and LuxR against the Streptomyces non-redundant protein sequences database resulted in limited homologs of LuxI and LuxR in a handful of Streptomyces species. However, the HMMsearch using LuxI- and LuxR-specific HMMs resulted in multiple AHL synthases and receptors homologous to LuxI and LuxR in 2336 unique Streptomyces. Previous investigations on the existence of LuxI and LuxR homologs in Actinobacteria only resulted in a single potential LuxI homolog in S. sviceus (SSEG_02829) (Santos et al., 2012) and some LuxR proteins in a limited number of Streptomyces species, including S. avermitilis MA-4680, S. coelicolor A3(2), and S. griseus subsp. griseus NBRC 13350 (Santos et al., 2012). Wet-lab studies on the LuxR family regulator in Streptomyces sp. SN593, although with other ligands (β-carboline), has proved the functional role of these receptors in gene regulation and secondary metabolism (Panthee et al., 2020).

Interestingly, many Streptomyces species were found to carry more than one AHL synthase homologous to LuxI. Similar to most of the Streptomyces covered here, the six Streptomyces of interest in this study possessed between four and seven LuxI homologs. Harboring multiple AHL synthases could be in line with the ability of these species to produce multiple AHLs of different size ranges. We were not able to establish a positive correlation between the copy number of LuxI homologs and the number of AHLs produced by the six Streptomyces of interest, yet we are not surprised due to the imperfection of our methods and the possibility of the role of substrate pools in the combination and abundance of produced AHLs. Regarding the AHL receptors, their high abundance could be interpreted in the context of Streptomyces’ rich secondary metabolism and the need for their physiological regulation activities or their inter- and intra-domain interactions and communications with other species. In spite of supporting evidence, it is worth noting that this data should be considered preliminary, and further investigations are suggested to shed light on the origins of these proteins, their structure, the existence of domains of interest, functions, and their physiological and ecological roles.

AHLs have also been reported in a few other Gram-positive bacteria, i.e., Salinispora (Bose et al., 2017), Exiguobacterium (Biswa and Doble, 2013), and Bacillus (de Moura et al., 2021). However, the discovery of AHLs in Streptomyces species is accompanied by consequential implications for exploring the evolution of signaling circuits and their role in cellular complexity and multicellularity, in addition to benefiting the industry and the clinic. Moreover, while previous studies only reported a few AHLs (Oxo-C10-HSL and Oxo-C12-HSL in Salinispora and Oxo-C8-HSL in Exiguobacterium) limited to a single size range, we demonstrated that each Streptomyces possesses a handful of AHLs from different size ranges, which is more compatible with the physiological complexity of these organisms. Consequently, these findings expand our understanding of lactone-based gene regulation systems in Gram-positive bacteria, especially Streptomyces. Therefore, AHLs might also be involved in regulating secondary metabolites and differentiation in Streptomyces, similar to the role of GBLs. While AHLs might regulate specific target genes, they might also interfere with the GBL–receptor interaction by competing with GBLs to occupy the receptor.

Production of AHLs by Streptomyces species as Gram-positive bacteria stands against previous knowledge suggesting the exclusivity of AHLs to Gram-negative bacterial species (Azimi et al., 2020). Following our observations, further investigations are required to confirm the existence of AHLs, their synthases and receptors, and the function of AHL-based gene regulation systems in Gram-positive bacteria, specifically in the Actinomycetota phylum and Streptomyces species, due to their pharmaceutical and evolutionary significance (Salwan and Sharma, 2020).

5. Conclusion

AHLs are generally attributed to Gram-negative bacteria as the mediators of QS. Contrarily, six Streptomyces species, S. griseus, S. lavendulae FRI-5, S. clavuligerus, S. nodosus, S. lividans TK-64, and S. coelicolor A3(2), as Gram-positive bacteria, have been found to produce various AHLs, whereas only GBLs have been previously discovered in these species. Furthermore, this study has demonstrated that Streptomyces species potentially possess the enzymes necessary for the synthesis of AHLs and the receptors mediating their effects. These results might suggest the potential presence of an additional regulatory and signaling circuit based on AHLs in Streptomyces. Furthermore, AHLs and related gene regulatory systems might be more prevalent in the prokaryotic domain than previously assumed, and they might play a role in the regulation of secondary metabolites (e.g., antibiotics), leading to significant industrial and clinical value.

Data availability statement

The LC-MS/MS raw data presented in the study is deposited in the figshare repository, accession number 10.6084/m9.figshare.25112672. The data used and produced during in-silico studies is provided in the Supplementary material section. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

AS-N: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Validation. ST: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Visualization. GA: Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. JH: Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Validation.

Funding Statement

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2024.1342637/full#supplementary-material

References

- Alcántara R., Axelsen K. B., Morgat A., Belda E., Coudert E., Bridge A., et al. (2012). Rhea—a manually curated resource of biochemical reactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D754–D760. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1126, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amoabediny G., Büchs J. (2007). Modelling and advanced understanding of unsteady-state gas transfer in shaking bioreactors. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 46, 57–67. doi: 10.1042/BA20060120, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner M., Ball C. A., Blake J. A., Botstein D., Butler H., Cherry J. M., et al. (2000). Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat. Genet. 25, 25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azimi S., Klementiev A. D., Whiteley M., Diggle S. P. (2020). Bacterial quorum sensing during infection. Ann. Rev. Microbiol. 74, 201–219. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-032020-093845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barreales E. G., Payero T. D., Jambrina E., Aparicio J. F. (2020). The Streptomyces filipinensis gamma-butyrolactone system reveals novel clues for understanding the control of secondary metabolism. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 86, e00443–e00420. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00443-20, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswa P., Doble M. (2013). Production of acylated homoserine lactone by gram-positive bacteria isolated from marine water. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 343, 34–41. doi: 10.1111/1574-6968.12123, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bose U., Ortori C. A., Sarmad S., Barrett D. A., Hewavitharana A. K., Hodson M. P., et al. (2017). Production of N-acyl homoserine lactones by the sponge-associated marine actinobacteria Salinispora arenicola and Salinispora pacifica. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 364:fnx002. doi: 10.1093/femsle/fnx002, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Moura G. G. D., de Barros A. V., Machado F., Martins A. D., da Silva C. M., Durango L. G. C., et al. (2021). Endophytic bacteria from strawberry plants control gray mold in fruits via production of antifungal compounds against Botrytis cinerea L. Microbiol. Res. 251:126793. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2021.126793, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Y.-L., Shen X.-L., Yu P., Bai L.-Q., Li Y.-Q. (2011). Gamma-butyrolactone regulatory system of Streptomyces chattanoogensis links nutrient utilization, metabolism, and development. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 8415–8426. doi: 10.1128/AEM.05898-11, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberhard A., Burlingame A. L., Eberhard C., Kenyon G. L., Nealson K. H., Oppenheimer N. J. (1981). Structural identification of autoinducer of Photobacterium fischeri luciferase. Biochemistry 20, 2444–2449. doi: 10.1021/bi00512a013, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engebrecht J., Nealson K., Silverman M. (1983). Bacterial bioluminescence: isolation and genetic analysis of functions from Vibrio fischeri. Cell 32, 773–781. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90063-6, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fekete A., Frommberger M., Rothballer M., Li X., Englmann M., Fekete J., et al. (2007). Identification of bacterial N-acylhomoserine lactones (AHLs) with a combination of ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC), ultra-high-resolution mass spectrometry, and in-situ biosensors. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 387, 455–467. doi: 10.1007/s00216-006-0970-8, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng H., Ding Y., Wang M., Zhou G., Zheng X., He H., et al. (2014). Where are signal molecules likely to be located in anaerobic granular sludge? Water Res. 50, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2013.11.021, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flärdh K., Buttner M. J. (2009). Streptomyces morphogenetics: dissecting differentiation in a filamentous bacterium. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7, 36–49. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1968, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuqua C., Greenberg E. P. (2002). Listening in on bacteria: acyl-homoserine lactone signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3, 685–695. doi: 10.1038/nrm907, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuqua C., Parsek M. R., Greenberg E. P. (2001). Regulation of gene expression by cell-to-cell communication: acyl-homoserine lactone quorum sensing. Annu. Rev. Genet. 35, 439–468. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.35.102401.090913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanzelka B. L., Stevens A. M., Parsek M. R., Crone T. J., Greenberg E. P. (1997). Mutational analysis of the Vibrio fischeri LuxI polypeptide: critical regions of an autoinducer synthase. J. Bacteriol. 179, 4882–4887. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.15.4882-4887.1997, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horinouchi S., Beppu T. (1994). A-factor as a microbial hormone that controls cellular differentiation and secondary metabolism in Streptomyces griseus. Mol. Microbiol. 12, 859–864. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01073.x, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao N.-H., Söding J., Linke D., Lange C., Hertweck C., Wohlleben W., et al. (2007). ScbA from Streptomyces coelicolor A3 (2) has homology to fatty acid synthases and is able to synthesize γ-butyrolactones. Microbiology 153, 1394–1404. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2006/004432-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y.-L., Ki J.-S., Case R. J., Qian P. (2008). Diversity and acyl-homoserine lactone production among subtidal biofilm-forming bacteria. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 52, 185–193. doi: 10.3354/ame01215 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jose P. A., Maharshi A., Jha B. (2021). Actinobacteria in natural products research: progress and prospects. Microbiol. Res. 246:126708. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2021.126708, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jumper J., Evans R., Pritzel A., Green T., Figurnov M., Ronneberger O., et al. (2021). Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 596, 583–589. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khokhlov A., Tovarova I., Borisova L., Pliner S. A., Shevchenko L. N., Kornitskaia E. I., et al. (1967). The A-factor, responsible for streptomycin biosynthesis by mutant strains of Actinomyces streptomycini. Dok. Akad. Nauk SSSR. 177, 232–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khushboo, Kumar P., Dubey K. K., Usmani Z., Sharma M., Gupta V. K. (2022). Biotechnological and industrial applications of streptomyces metabolites. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefin. 16, 244–264. doi: 10.1002/bbb.2294 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kong D., Wang X., Nie J., Niu G. (2019). Regulation of antibiotic production by signaling molecules in Streptomyces. Front. Microbiol. 10:2927. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02927, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller M. B., Bassler B. L. (2001). Quorum sensing in bacteria. Ann. Rev. Microbiol. 55, 165–199. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mingyar E., Feckova L., Novakova R., Bekeova C., Kormanec J. (2015). A γ-butyrolactone autoregulator-receptor system involved in the regulation of auricin production in Streptomyces aureofaciens CCM 3239. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 99, 309–325. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-6057-0, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misaki Y., Takahashi Y., Hara K., Tatsuno S., Arakawa K. (2022). Three 4-monosubstituted butyrolactones from a regulatory gene mutant of Streptomyces rochei 7434AN4. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 133, 329–334. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2022.01.006, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin D., Grasland B., Vallée-Réhel K., Dufau C., Haras D. (2003). On-line high-performance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometric detection and quantification of N-acylhomoserine lactones, quorum sensing signal molecules, in the presence of biological matrices. J. Chromatogr. A 1002, 79–92. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9673(03)00730-1, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panthee S., Kito N., Hayashi T., Shimizu T., Ishikawa J., Hamamoto H., et al. (2020). β-carboline chemical signals induce reveromycin production through a LuxR family regulator in Streptomyces sp. SN-593. Sci. Rep. 10:10230. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-66974-y, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsek M. R., Greenberg E. P. (2000). Acyl-homoserine lactone quorum sensing in gram-negative bacteria: a signaling mechanism involved in associations with higher organisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 97, 8789–8793. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.16.8789, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polkade A. V., Mantri S. S., Patwekar U. J., Jangid K. (2016). Quorum sensing: an under-explored phenomenon in the phylum Actinobacteria. Front. Microbiol. 7:131. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00131, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues A. M., Lami R., Escoubeyrou K., Intertaglia L., Mazurek C., Doberva M., et al. (2022). Straightforward N-acyl homoserine lactone discovery and annotation by LC–MS/MS-based molecular networking. J. Proteome Res. 21, 635–642. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.1c00849, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salwan R., Sharma V. (2020). Molecular and biotechnological aspects of secondary metabolites in actinobacteria. Microbiol. Res. 231:126374. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2019.126374, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos C. L., Correia-Neves M., Moradas-Ferreira P., Mendes M. V. (2012). A walk into the LuxR regulators of Actinobacteria: phylogenomic distribution and functional diversity. PLoS One 7:e46758. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046758, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer A. L., Greenberg E., Oliver C. M., Oda Y., Huang J. J., Bittan-Banin G., et al. (2008). A new class of homoserine lactone quorum-sensing signals. Nature 454, 595–599. doi: 10.1038/nature07088, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharif D. I., Gallon J., Smith C. J., Dudley E. (2008). Quorum sensing in Cyanobacteria: N-octanoyl-homoserine lactone release and response, by the epilithic colonial cyanobacterium Gloeothece PCC6909. ISME J. 2, 1171–1182. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2008.68, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiner E. K., Rumbaugh K. P., Williams S. C. (2005). Interkingdom signaling: deciphering the language of acyl homoserine lactones. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 29, 935–947. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2005.03.001, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swift S., Bainton N. J., Winson M. K. (1994). Gram-negative bacterial communication by N-acyl homoserine lactones: a universal language? Trends Microbiol. 2, 193–198. doi: 10.1016/0966-842X(94)90110-Q, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takano E. (2006). γ-Butyrolactones: Streptomyces signalling molecules regulating antibiotic production and differentiation. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 9, 287–294. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2006.04.003, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K., Stecher G., Kumar S. (2021). MEGA11: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 3022–3027. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msab120, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J. D., Higgins D. G., Gibson T. J. (1994). CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22, 4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twigg M. S., Tait K., Williams P., Atkinson S., Cámara M. (2014). Interference with the germination and growth of Ulva zoospores by quorum-sensing molecules from Ulva-associated epiphytic bacteria. Environ. Microbiol. 16, 445–453. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12203, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varadi M., Anyango S., Deshpande M., Nair S., Natassia C., Yordanova G., et al. (2022). AlphaFold protein structure database: massively expanding the structural coverage of protein-sequence space with high-accuracy models. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, D439–D444. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab1061, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterhouse A. M., Procter J. B., Martin D. M., Clamp M., Barton G. J. (2009). Jalview version 2—a multiple sequence alignment editor and analysis workbench. Bioinformatics 25, 1189–1191. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp033, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winson M. K., Camara M., Latifi A., Foglino M., Chhabra S. R., Daykin M., et al. (1995). Multiple N-acyl-L-homoserine lactone signal molecules regulate production of virulence determinants and secondary metabolites in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 92, 9427–9431. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9427, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The LC-MS/MS raw data presented in the study is deposited in the figshare repository, accession number 10.6084/m9.figshare.25112672. The data used and produced during in-silico studies is provided in the Supplementary material section. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.