Abstract

The medial nucleus of the trapezoid body (MNTB) has been intensively investigated as a primary source of inhibition in brainstem auditory circuitry. MNTB-derived inhibition plays a critical role in the computation of sound location, as temporal features of sounds are precisely conveyed through the calyx of Held/MNTB synapse. In adult gerbils, cholinergic signaling influences sound-evoked responses of MNTB neurons via nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs; Zhang et al., 2021) establishing a modulatory role for cholinergic input to this nucleus. However, the cellular mechanisms through which acetylcholine (ACh) mediates this modulation in the MNTB remain obscure. To investigate these mechanisms, we used whole-cell current and voltage-clamp recordings to examine cholinergic physiology in MNTB neurons from Mongolian gerbils (Meriones unguiculatus) of both sexes. Membrane excitability was assessed in brain slices, in pre-hearing (postnatal days 9–13) and post-hearing onset (P18–20) MNTB neurons during bath application of agonists and antagonists of nicotinic (nAChRs) and muscarinic receptors (mAChRs). Muscarinic activation induced a potent increase in excitability most prominently prior to hearing onset with nAChR modulation emerging at later time points. Pharmacological manipulations further demonstrated that the voltage-gated K+ channel KCNQ (Kv7) is the downstream effector of mAChR activation that impacts excitability early in development. Cholinergic modulation of Kv7 reduces outward K+ conductance and depolarizes resting membrane potential. Immunolabeling revealed expression of Kv7 channels as well as mAChRs containing M1 and M3 subunits. Together, our results suggest that mAChR modulation is prominent but transient in the developing MNTB and that cholinergic modulation functions to shape auditory circuit development.

Keywords: auditory, cholinergic, developmental switch, Kv7, MNTB, muscarinic

Significance Statement

This study is the first to examine downstream cellular mechanisms that underlie modulatory effects of acetylcholine (ACh) in medial nucleus of the trapezoid body (MNTB) neurons. The MNTB is a primary source of inhibition in the superior olive and features the calyx of Held, an intensively studied giant synapse that plays a pivotal role in precise encoding of acoustic cues. Recently, we discovered that ACh modulates MNTB responses in adult gerbils through nicotinic receptors. Here, we demonstrate that ACh has potent effects on membrane excitability prior to hearing onset primarily via muscarinic receptors and describe the expression of two muscarinic receptor subtypes. Our results suggest that developmentally transient cholinergic modulation of a voltage-gated K+ conductance is poised to influence circuit development during the peri-hearing onset period.

Introduction

Auditory brainstem nuclei in the superior olivary complex (SOC) collectively process a range of stimulus cues that are important for computing several features of sound such as stimulus location and gap detection (Grothe et al., 2010; Kopp-Scheinpflug et al., 2011). A keystone nucleus in the SOC is the MNTB, which provides temporally precise glycinergic inhibition to the medial superior olive (MSO; Adams and Mugnaini, 1990), the lateral superior olive (LSO; Spangler et al., 1985; Banks and Smith, 1992), and the superior paraolivary nucleus (SPN; Sommer et al., 1993; Kopp-Scheinpflug et al., 2011). The MNTB precisely encodes temporal cues due primarily to its single large excitatory synapse, the calyx of Held, deriving from the contralateral cochlear nucleus (CN; Banks and Smith, 1992; Park et al., 1996; Pecka et al., 2008; Altieri et al., 2014; Koka and Tollin, 2014). This electrically secure synapse has been intensively studied due to its unique features; however, it was only recently established that neuromodulators such as acetylcholine (ACh) contribute to MNTB responses.

In a previous in vivo study, we demonstrated nAChR-mediated modulation of sound-evoked responses in the adult gerbil MNTB and in a separate study, anatomically mapped cholinergic inputs to the superior olive (Beebe et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2021). Across the brain, cholinergic modulation has been shown to affect multiple neural processes including neurotransmitter release (McGehee et al., 1995; Gray et al., 1996; Alkondon et al., 1997), postsynaptic excitability (Fujino and Oertel, 2001; Berg and Conroy, 2002), maturation of synapses (Aramakis et al., 2000), and synaptic plasticity (Fujii et al., 1999; Ji et al., 2001; Ge and Dani, 2005). Intriguingly, Happe and Morley (2004) demonstrated elevated expression of nAChRs in the SOC prior to hearing onset followed by persistent moderate expression into maturity. Several studies have demonstrated substantial refinement of SOC neural architecture during and immediately after hearing onset (Sanes and Takacs, 1993; Kandler and Friauf, 1995a,b; Kim and Kandler, 2003; Scott et al., 2005; Rodríguez-Contreras et al., 2008). However, the cellular mechanisms mediating this modulation in the MNTB remain unknown.

ACh activates both ionotropic nAChRs and metabotropic mAChRs. Each class comprises a variety of receptor species composed of differential subunit combinations and has varied expression levels both temporally and spatially throughout the brain. nAChRs are ligand-gated ion channels while mAChRs are G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) that initiate downstream intracellular cascades (Brown, 2010). mAChR expression has been documented in CN and SOC (Safieddine et al., 1996; Yao et al., 1996; Gillet et al., 2020) and has been shown to contribute to alterations in membrane excitability in the bushy cells of the CN (Goyer et al., 2016). This effect can occur by inactivating ion channels, including several K+ channels (Krnjevic et al., 1971; Halliwell and Adams, 1982; McCormick and Prince, 1986; Madison et al., 1987; Brown, 2018). Notably, there have been no physiological studies investigating cholinergic modulation in the MNTB or the superior olive. Here, we describe for the first time prominent mAChR modulation of MNTB membrane excitability that is mediated by mAChRs in pre-hearing onset neurons and moderately by nAChRs post-hearing onset. Further, we show that mAChRs exert this influence via the voltage-gated K+ channel KCNQ (Kv7) and provide immunohistochemical confirmation of expression of potentially relevant mAChRs and Kv7 channels. Our results suggest that mAChRs are poised to influence neural excitability during a dynamic critical period of circuit refinement.

Materials and Methods

All procedures were in compliance with Public Health Services and approved by the Lehigh University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Brain slice preparation

Mongolian gerbils (Meriones unguiculatus) aged postnatal days 9–22 (P9–P22) of both sexes were anesthetized with isoflurane and rapidly decapitated, and the brainstem containing the auditory nuclei was removed, blocked, and submerged in oxygenated artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) prepared as follows (in mM): 125 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 25 glucose, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2 at 22°C. The brainstem was placed rostral surface down on the stage of a vibrating microtome (HM650V, Microm). Coronal sections (150–200 μm) containing the auditory brainstem nuclei were collected, submerged in an incubation chamber of continuously oxygenated ACSF, and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Slices were then maintained at room temperature until used for recording. Brainstem slices were placed in a custom recording chamber on a retractable chamber shuttle system (Siskiyou Design Instruments), and neurons were visualized with a Nikon FN-1 Physiostation microscope using infrared differential interference contrast optics. Video images were captured with a CCD camera (Hamamatsu) coupled to a video monitor. The recording chamber was continuously perfused with ACSF at a rate of 2–4 ml/min. An inline feedback temperature controller and heated stage were used to maintain chamber temperature at 35 ± 1°C (TC344B, Warner Instruments).

In vitro whole-cell recordings

Borosilicate capillary glass pipettes (1B120F-4, World Precision Instruments) were pulled to a resistance of 4–8 MΩ with a two-stage puller (PC-10, Narishige) and back-filled with internal solution. The internal solution for current-clamp experiments contained the following in mM: 145 K-gluconate, 5 KCl, 5 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 1 MgCl2, 4 Na2ATP, and 0.3 Na2GTP, pH 7.2, adjusted with KOH. Cholinergic receptors were pharmacologically isolated in ACSF containing 6,7-dinitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (DNQX; 40 μM) and D-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid (AP5; 50 μM) to block AMPA and NMDARs, SR-95531 (20 μM) to block GABAARs, and CGP-55845 (2 μM) to block GABABRs. nAChRs and mAChRs were blocked with 10 µM mecamylamine (MEC) and 2 μM atropine, respectively, and both were activated with 30 μM ACh. Current injection protocols included steps ranging from 50 to 100 pA for 200 ms. The effect of the cholinergic receptors was compared between treatments by measuring resting membrane potential (RMP); threshold current (ITHRESH), defined as the lowest current injected to reliably elicit AP > 75% of the time; and action potential count (APCOUNT; Figs. 1–3).

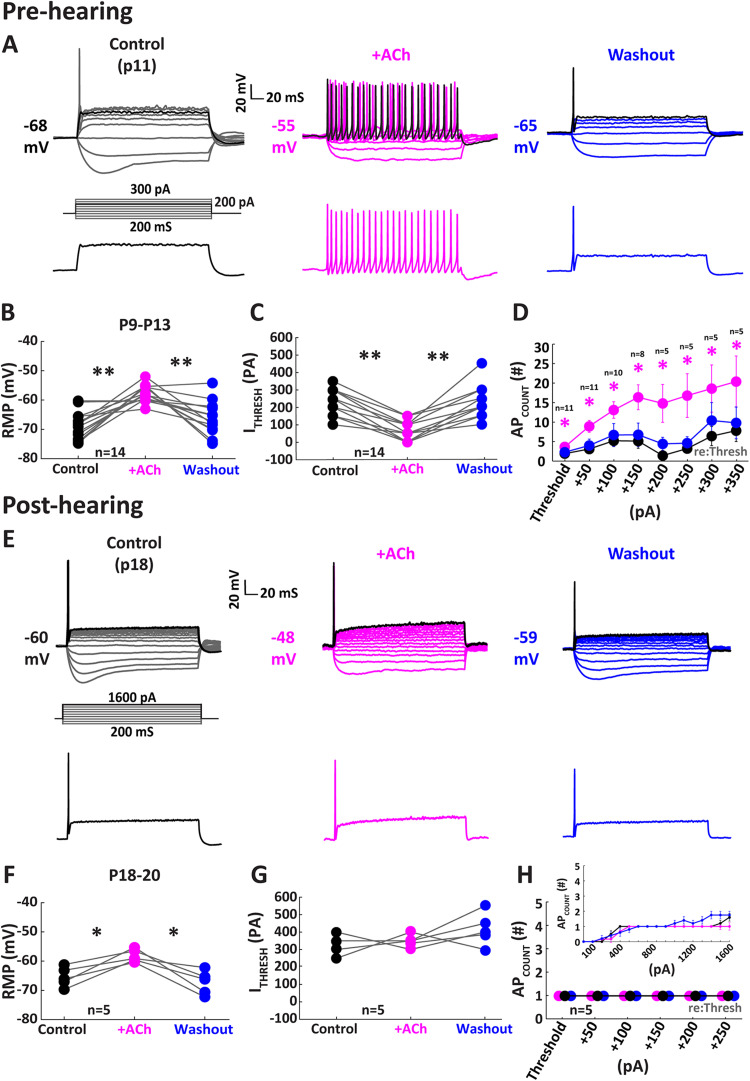

Figure 1.

Excitability is enhanced by ACh in pre-hearing onset MNTB cells. A, Illustration of a single MNTB neuron from a P11 gerbil in response to hyperpolarizing and depolarizing current steps following bath application of 30 μM ACh. The top row panels show a family of voltage responses from the input protocol. The black traces (200 pA) represent the maximum injection in the ACh condition and are isolated in the bottom panels illustrating the increase in APs in the presence of ACh. B–D, Population data of pre-hearing onset MNTB cells (P9–13). B, The modulation by ACh on MNTB cells depolarizes RMP (mV; p = 7.38 × 10−5; Tukey's post hoc; n = 14) C lowers ITHRESH (p = 2.22 × 10−6; Tukey's post hoc; n = 14) and D increases the APCOUNT (#; p = 0.016; Friedman's test; n = 8) indicating general enhancement of neuron excitability pre-hearing onset. E, Illustration of a single p18 MNTB neuron in the presence of ACh. The top panels show all current-clamp traces. The black traces (1,600 pA) represent the maximum injection and are shown in the bottom panels illustrating the lack of increase in AP in response to ACh. F–H, Population data from five post hearing onset MNTB cells. F illustrates the mild modulation of RMP (p = 0.02; Tukey's post hoc; n = 5), while (G) ITHRESH and (H) APCOUNT remain unchanged indicating that the effects of ACh are developmentally regulated. Inset in panel H shows unnormalized APCOUNT across a wide range of current injection levels. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.001.

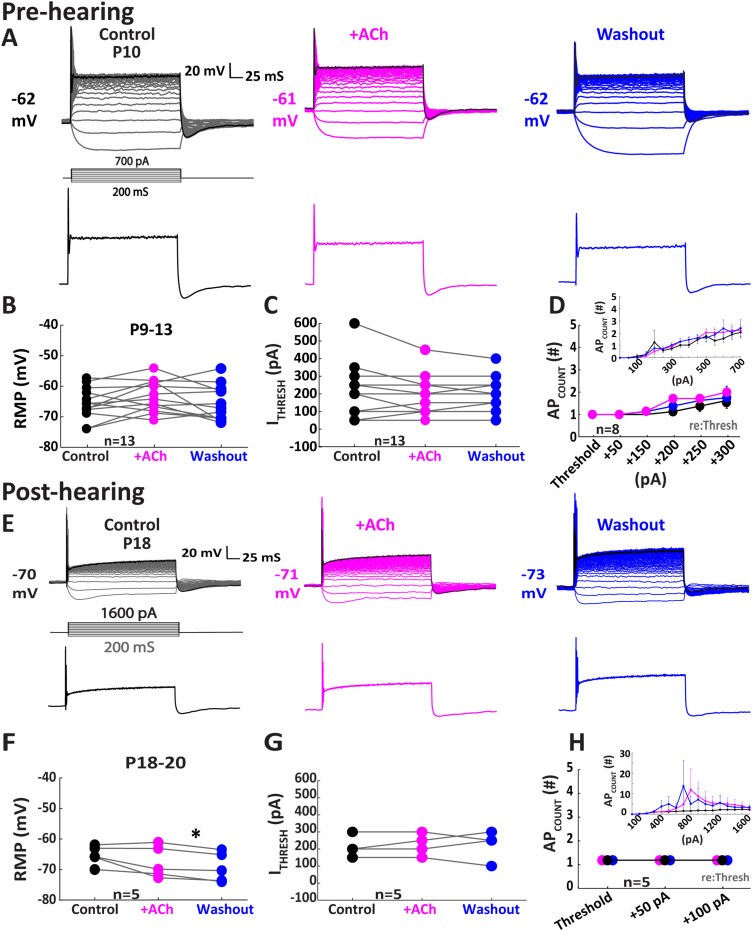

Figure 3.

ACh enhances pre-hearing onset MNTB cell excitability through muscarinic receptors (mAChRs). All data were collected in the presence of 2 μM atropine to block mAChRs. A, Illustration of a single MNTB neuron from a P10 gerbil in response to ACh while pre-blocking mAChRs with 2 μM atropine. The top panel shows current-clamp traces. The black traces (700 pA) represent the maximum injection and are shown isolated in the bottom panels illustrating the lack of increase in APs in response to ACh. B–D, Population data from 13 pre-hearing onset MNTB cells shows the lack of modulation of ACh on RMP (p = 0.093; Wilcoxon signed-rank test; n = 13) (B), ITHRESH (p = 0.167; Wilcoxon signed-rank test; n = 13) (C), and APCOUNT (p = 0.401; Friedman test; n = 8) (D) which remain unchanged indicating that mAChRs were necessary for the modulation of ACh on MNTB neurons pre-hearing onset. Inset in panel D shows the unnormalized APCOUNT. E, Illustration of a single MNTB neuron from a P18 gerbil in response to ACh while pre-blocking mAChRs. The top panels show the current-clamp traces. The black traces (1,600 pA) represent the maximum injection and are shown in the bottom panels illustrating the lack of increase in APs in response to ACh. F–H, Population data from post-hearing onset MNTB cells (P18–20) shows a lack of modulation by ACh on (F) RMP (p = 0.46; Tukey's post hoc; n= 5) while (G) ITHRESH remained unchanged in ACh (p = 0.317; Wilcoxon signed-rank test; n = 5) with a small but significant hyperpolarization in washout condition (p = 0.01; Tukey's post hoc; n = 5). H, APCOUNT remained unchanged. Inset in panel H shows unnormalized APCOUNT across a range of current injection levels; *p < 0.05.

For experiments involving Oxotremorine M (Oxo-M) and XE-991, the internal solution was prepared as follows (in mM): 145 K-gluconate, 5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 0.2 EGTA, 2 Na2ATP, 0.3 Na2GTP, 10 phosphocreatine Tris, pH adjusted to 7.2–7.3 with KOH. For voltage-clamp experiments, 5 mM QX-314 was added to the internal solution to prevent antidromic APs. The control ACSF for these experiments contained 20 μM SR-95531. For assessment of muscarinic effects during voltage- or current-clamp experiments, 1 mM Oxo-M or/and 1 mM XE-991 were added to the control bath. For M-current isolation, SR-95531 (20 μM), 4-AP (30 μM), ZD-7288 (20 μM), DNQX (40 μM), and tetraethylammonium chloride (1 mM, Sigma-Aldrich) were added to the control ASCF solution. Pharmacological agents were obtained from Tocris unless indicated otherwise. A liquid junction potential of 7–10 mV was corrected for in internal solutions. In voltage clamp, series resistance was compensated at 60–80% (Multiclamp 700B, Molecular Devices). The signal was digitized with a Digidata 1440A data acquisition board and recorded with Clampex software (Molecular Devices). The digitized data were analyzed offline using custom scripts in MATLAB (MathWorks). The capacitive transients from raw voltage-clamp traces were cropped for data display using Adobe Illustrator.

Immunohistochemistry

Staining for M1 and M3 AChRs was performed, using antibodies previously published, in the gerbil (Gillet et al., 2018). The M1 antibody was raised in rabbit against amino acids 227–353 of the intracellular loop i3 of the human M1 AChR. M1 receptors are highly conserved proteins, and previous studies have demonstrated these antibodies to be specific using a combination of Western blot (Batallan Burrowes et al., 2022) and antigen preadsorption studies in humans, monkeys, dogs, and rodents (Disney et al., 2014; Tsukimi et al., 2020). The M3 antibody was raised in rabbit against amino acids 461–479 of the third intracellular loop of rat M3 receptor. M3 is also highly conserved, and antibody specificity has been demonstrated in humans and rodents through Western blot (Olianas et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2022), immunoprecipitation (Yue et al., 2006), and knock-out controls (Olianas et al., 2014). Staining for KCNQ2 was performed using an antibody raised in the rabbit against the first 70 aa of human KCNQ2 and does not detect other KCNQ subtypes. KCNQ2 and KCNQ3 form heteromers and are known to underlie M currents. Specificity of the KCNQ antibody has been demonstrated by controlled expression in a mouse cell line (Verneuil et al., 2020), Western blot, immunoprecipitation in the rat (Pablo and Pitt, 2017), and using knock-out mice (Jenkins et al., 2015).

Briefly, 32 gerbils ranging in age from P9 to P22 were deeply anesthetized with an overdose of Somnasol veterinary euthanasia solution (Henry Schein Animal Health, >0.25 ml/kg body weight) and transcardially perfused with PBS followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS, pH 7.4. Brains were removed and postfixed in 4% PFA overnight at 4°C and then rinsed. The auditory brainstem was blocked and sectioned at 50 μm (7000smz-2, Campden Instruments). Tissue was rinsed, blocked in 10% normal goat serum for 1 h, and then incubated overnight at 4°C in solution containing 5% normal goat serum, anti-MAP2 (1:1,000; Neuromics, catalog #CH22103), anti-mACHR (M1, 1:200; Alomone Labs, catalog #AMR-010; M3, 1:50; Alomone Labs, catalog #AMR-006), anti KCNQ2 (1:100; Thermo Fisher Scientific, catalog #PA1-929), and anti-Rab3A (1:500; Synaptic Systems, catalog #107-111). Sections were rinsed and then incubated for 2 h with secondary antibodies (Thermo Fisher Scientific) conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit to label M1 and M3 and Kv7.2, Alexa Fluor 633 goat anti-chicken to label MAP2, and Alexa Fluor 546 to label Rab3A. Sections were mounted on slides in Glycergel (Dako) or (Vectashield containing DAPI) medium, and confocal images were captured (LSM 880 Meta, Zeiss). No immunohistochemical (IHC) staining was observed when primary antibodies were absent for any primary used in this study. Adobe Photoshop and Illustrator Software were used to label, colorize, and crop images for display.

Experimental design and statistical analysis

The normality of data distributions for RMP, ITHRESH, and APCOUNT during 200 ms stimulus epochs, membrane current, and holding current (IHOLD) were tested using the Shapiro–Wilk test, and the post hoc tests were corrected using Bonferroni’s adjustments where applicable. Neurons with initial RMPs between −55 and −80 mV were considered healthy, and data were kept for further analysis. All population analysis included data from at least three individual animals from at least three separate breeding cages. ITHRESH is defined as the lowest current injected that triggered APs in >75% of input sweeps. For M-current extraction, the traces were resampled offline at 49,980 Hz (with sampling rate at 50 kHz, there were roughly 50 kHz/60 Hz ≍ 833 samples in a complete cycle of 60 Hz; resampling frequency was therefore 833 × 60 Hz = 49,980 Hz) before applying a uniformly weighted moving average filter operating at 60 Hz to remove residual line noise. M-current was measured as the difference between the maximum instantaneous current (after the first 100 ms of the hyperpolarizing step in M-current isolation) and the steady-state current (at the end of each hyperpolarizing step), as described in Brown and Adams (1980) and Gillet et al. (2020). Comparisons between pre- and post-treatment data with only one pharmacological condition were assessed using two-tailed paired Student's t test if normally distributed or Wilcoxon paired signed-rank test if the distribution was not normal. Statistical comparisons among more than two conditions were evaluated using repeated-measures ANOVA, followed by Tukey's post hoc for pairwise assessment if normally distributed, or the Friedman test if non-normal. The average values were expressed as mean ± SE or medians if Friedman test was used. The confidence interval (CI) was invariably 95%.

Results

We recorded 111 neurons from 59 animals derived from two primary groups differentiated by developmental age. Animals aged P9–13, hereafter, are referred to as pre-hearing onset (n = 69); and those aged P18–20 will be indicated as post-hearing onset (n = 42). In addition, we performed immunohistochemical studies on 32 additional subjects ranging in age from P9 to 20.

ACh modulation depolarizes resting potential and membrane excitability in pre-hearing onset MNTB neurons

To assess effects of ACh on MNTB neuron excitability, we bath applied 30 μM ACh to neurons in both pre-hearing (P9–13; n = 14) and post-hearing onset (P18–20; n = 5; Fig. 1) groups. We then measured the RMP (mV; Fig. 1B,F), ITHRESH (pA; Fig. 1C,G), and APCOUNT (#; Fig 1D,H) in response to depolarizing current injections (200 ms, 50 pA steps) in both groups. In the pre-hearing onset group, the RMP reversibly depolarized in the presence of ACh application (Fig. 1B; from −68.84 ± 1.26 to −57.74 ± 0.75 mV) during treatment (n = 14; p = 7.38 × 10−5; Tukey's post hoc) and recovered to −66.24 ± 1.71 mV after washout (n = 14; p = 6.84 × 10−4; Tukey's post hoc). ITHRESH decreased in the presence of ACh (Fig. 1C; from 221.43 ± 22.06to 60.71 ± 14.03 pA) during application (n = 14; p = 2.22 × 10−6; Tukey's post hoc) and recovered to 214.29 ± 24.26 pA after washout (n = 14; p = 1.35 × 10−5; Tukey's post hoc).

We next examined input–output AP rate gain in response to depolarizing current steps in each condition. APCOUNT was normalized to the AP threshold current in each treatment to compare rate gain in response to increasing depolarizing current in 50 pA steps. ACh facilitated an increase in the overall APCOUNT at current steps above threshold (p < 0.05 for all steps; Fig. 1D; Friedman test). For example, at 150 pA over threshold analysis revealed that APCOUNT was increased from a median 2.00 spikes in control to a median 20.00 spikes in ACh (p = 0.037; n = 8) and, after washout, returned to near control values similarly to other current step amplitudes (washout, median = 3; p = 0.634 vs control; Fig. 1D). In most cases during ACh application, current step protocols were proactively arrested prior to reaching the maximum step amplitudes used in control, as increased response vigor in the presence of ACh often exceeded sustainable levels for neural viability.

In post-hearing onset neurons, RMP also depolarized in ACh treatment albeit by a smaller amount (Fig. 1F; from −65.44 ± 1.50 to −58.18 ± 0.97 mV) during drug treatment (n = 5; p = 0.02; Tukey's post hoc) and recovered to −67.34 ± 1.83 mV after washout (n = 5; p = 0.02; Tukey's post hoc). In contrast to the pre-hearing group, ITHRESH was not significantly affected in post-hearing onset neurons in the presence of ACh (Fig. 1G; from 320.99 ± 25.50 pA in control to 350.00 ± 15.81 pA) during ACh treatment (n = 5; p = 0.13; Tukey's post hoc).

We next examined APCOUNT normalized to ITHRESH in the post-hearing onset group. APCOUNT was unchanged in any condition in post-hearing MNTB neurons (Fig. 1H) which discharged only once at the onset of the step in most cases. Absolute spike counts are displayed over the full range of current injections in the inset of Figure 1H, demonstrating mature MNTB neurons’ reliable single action potential response over a very broad range of current injection levels regardless of treatment (Fig. 1H; control, 1 ± 0.00 spikes; ACh, 1 ± 0.0 spikes; n = 5; p = 1.00; Wilcoxon signed-rank test).

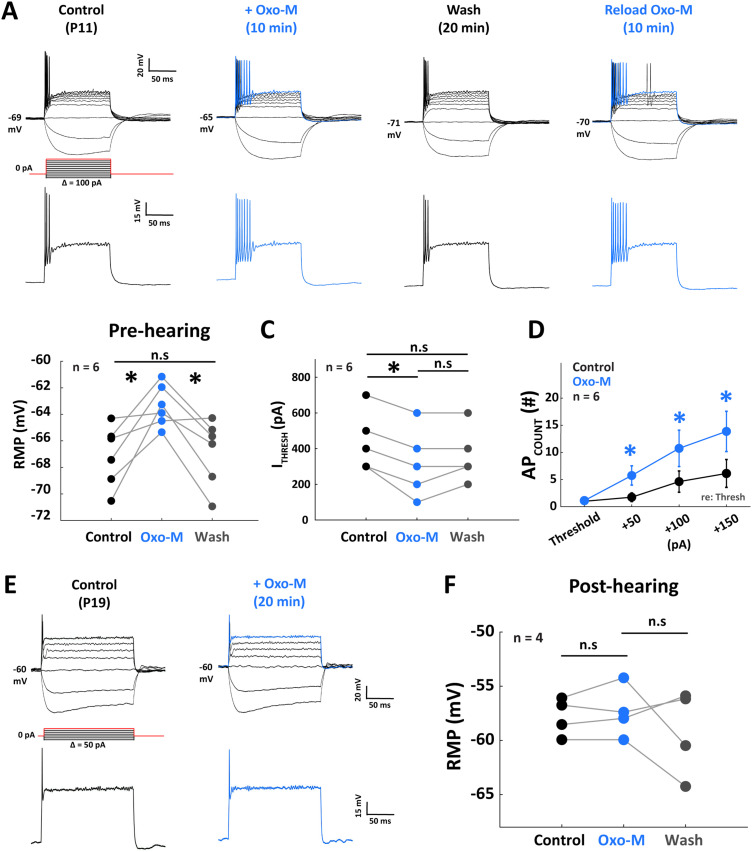

Cholinergic modulation in MNTB is predominantly mediated by muscarinic receptors

Since both nAChRs and mAChRs respond to ACh, we repeated these experiments in the presence of 10 µM MEC to block all nAChRs and to determine which of the effects that we observed were attributable to mAChRs. We again examined RMP, ITHRESH, and APCOUNT in both age groups (Fig. 2). When we examined the pre-hearing onset group, RMP again was reversibly depolarized by a similar amount to values observed in ACh alone (Fig. 2B; from −65.90 ± 2.51 to −58.42 ± 2.68 mV) during ACh treatment in the presence of 10 µM MEC (n = 6; p = 1.83 × 10−3; Tukey's post hoc) and recovered to −64.20 ± 2.94 mV after washout (n = 6; p = 2.55 × 10−3; Tukey's post hoc). However, ITHRESH did not significantly decrease in the presence of ACh with MEC treatment (Fig. 2C; from 125.0 ± 17.08 to 58.33 ± 15.37 pA) during drug treatment (n = 6; p = 0.06; Tukey's post hoc). We again examined input–output AP rate gain in each condition. In the presence of MEC, APCOUNT was again increased by ACh (p = 0.032; Friedman test). At 100 pA over threshold, post hoc analysis revealed that APCOUNT was increased from control by an average of 18 spikes (control, median count = 3.00 spikes; ACh, median count = 19.00 spikes; p = 0.130; n = 6) and after washout returned to near control values (washout, median count = 1.0 spike; p = 1.0 vs control; Fig. 2D).

Figure 2.

Cholinergic enhancement of pre-hearing onset MNTB excitability is independent of nAChR activity. All data were collected in the presence of 10 µM MEC to block nAChRs. A, Illustration of a single MNTB neuron from a P10 gerbil in response to 30 μM ACh while pre-blocking nAChRs with 10 µM MEC. The top panels show the current-clamp traces. The black traces (250 pA) represent the maximum injection and are shown in the bottom panels illustrating the increase in APs in response to ACh. B–D, Population data of five pre-hearing onset MNTB cells shows the modulation of ACh on MNTB cells by (B) depolarizing RMP (p = 1.83 × 10−3; Tukey's post hoc; n = 6). C, ITHRESH trended toward an insignificant decrease (p = 0.06; Tukey's post hoc; n = 6) while (D) APCOUNT increased (p = 0.032; Friedman test) indicating the enhancement of neuron excitability pre-hearing onset persists with nAChR block. E, Illustration of a single MNTB neuron from a P18 gerbil in response to ACh. The top panels show the current-clamp traces. The black traces (1,600 pA) represent the maximum injection and are shown in the bottom panels illustrating the lack of increase in APs in response to ACh. F–H, Population data of seven MNTB cells post-hearing onset shows the modulation of ACh on MNTB cells post-hearing onset by (F) depolarizing RMP (p = 3.64 × 10−3; Tukey's post hoc; n = 7), while (G) ITHRESH and (H) APCOUNT remain unchanged. *p < 0.05.

In the post-hearing onset group, we observed a smaller depolarization of the RMP during ACh treatment with an average decrease of 6.6 mV. The RMP reversibly depolarized from control during ACh application in the presence of 10 µM MEC (Fig. 2F; from −67.90 ± 1.08 to −64.77 ± 1.32 mV; n = 7; p = 3.64 × 10−3; Tukey's post hoc) and recovered to −69.33 ± 1.60 mV after washout (n = 7; p = 3.22 × 10−2; Tukey's post hoc). In contrast ITHRESH showed an insignificant downward trend in the presence of ACh (Fig. 2G; from 257.10 ± 39.98to 307.10 ± 46.84 pA; n = 7; p = 0.04; Tukey's post hoc) and recovered to 300.00 ± 43.64 pA after washout (n = 7; p = 0.91; Tukey's post hoc).

Similar to ACh treatment alone, there was no effect on APCOUNT as a function of depolarizing current magnitude in adult MNTB neurons as they maintained their characteristic phasic onset responses in each condition (Fig. 2H; control, 1 ± 0.00 mV; ACh, 1 ± 0.0 mV; n = 7; p = 1.00; Wilcoxon signed-rank test). The changes we observed during MEC application were similar in magnitude to those we observed with ACh alone, suggesting that nAChRs were unlikely to mediate cholinergic effects observed during application of ACh alone in pre-hearing MNTB neurons. Instead, these experiments suggest that mAChR activation was likely to contribute to the changes in membrane characteristics that were observed during ACh application.

To further test the hypothesis that nAChRs contribute to the cholinergic effects on MNTB neurons that we observed, we repeated these experiments in the presence of 2 µM atropine, a muscarinic antagonist. ACh application in the presence of atropine no longer facilitated a shift in RMP in the pre-hearing group (control, −67.29 ± 1.46 mV; ACh, −64.97 ± 1.44 mV; p = 0.093; Wilcoxon signed-rank test; n = 13; Fig. 3B). Similarly, ITHRESH was not affected by ACh treatment in the presence of atropine (control, 219.23 ± 40.64 pA; ACh, 196.15 ± 29.12 pA; p = 0.167; Wilcoxon signed-rank test; n = 13; Fig. 3C). Finally, ACh did not facilitate an increased APCOUNT during atropine application in the pre-hearing onset group (control, median = 1.00; ACh, median = 2.00; p = 0.401; Friedman test; n = 8).

In the presence of atropine, ACh treatment also had minimal impact on post-hearing neurons. There was no significant effect on RMP (Fig. 3F; from −64.86 ± 1.35 to −67.28 ± 2.26 mV) during ACh treatment (n = 5; p = 0.46; Tukey's post hoc). In washout conditions, neurons were significantly hyperpolarized compared with ACh conditions (Fig. 3F; from −67.28 ± 2.26 to −69.10 ± 2.17 mV; n = 5; p = 0.01; Tukey's post hoc). We observed no change in ITHRESH during ACh application compared with control (Fig. 3G; from 230.00 ± 30.00to 240.00 ± 29.15 pA; p = 0.62; Tukey's post hoc). Finally, APCOUNT was not altered by ACh for this group (Fig. 3H; control, 1 ± 0.00 mV; ACh, 1 ± 0.0 mV; n = 5; p = 1.00; Wilcoxon signed-rank test). Taken together, these results suggest that MNTB neuron excitability is modulated primarily through mAChRs in early development, around the period of hearing onset but this effect appears to wane by p18.

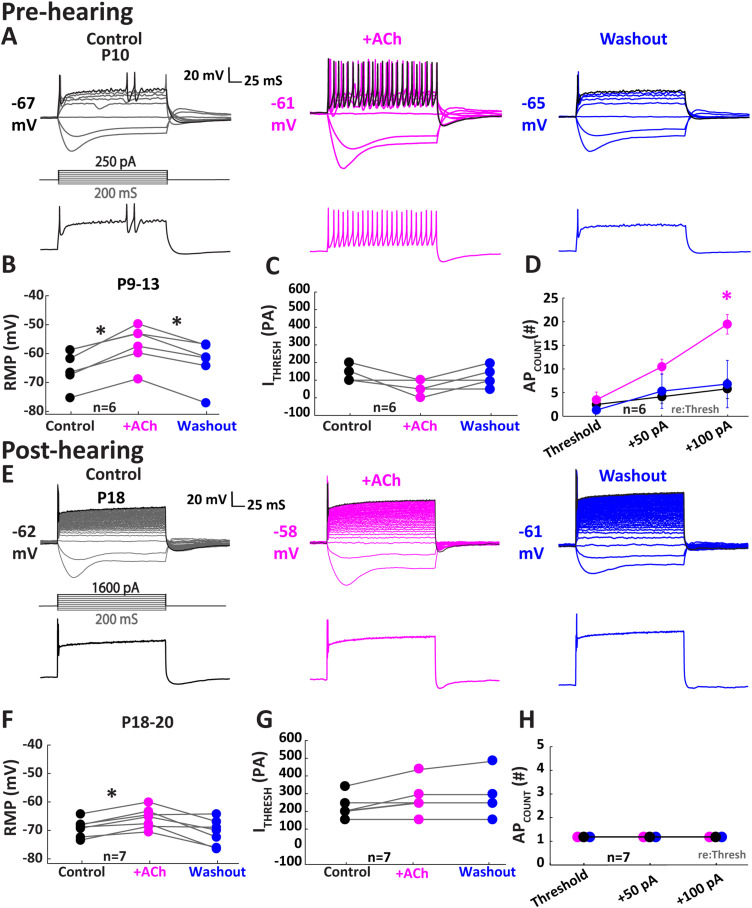

Muscarinic receptors inactivate M-channel currents (IM) prior to hearing onset

Since our results implicated mAChR-dependent mechanisms in the physiological changes that we observed in response to ACh application, we directly manipulated muscarinic signaling by bath application of the muscarinic agonist Oxo-M (Birdsall et al., 1978) in a series of experiments. A 1 mM Oxo-M application (Fig. 4) resulted in similar changes to RMP, ITHRESH, and APCOUNT compared with the ACh application after MEC pretreatment shown in Figure 2 (Fig. 4C), Oxo-M application also reduced ITHRESH from 317 ± 31 to 183 ± 31 pA (n = 6, p = 0.01; paired t test). Oxo-M increased the average APCOUNT (Fig. 4D) by 226.0 ± 81.2% (p = 0.03; Wilcoxon signed-rank test), 362.8 ± 190.0% (p = 0.03; Wilcoxon signed-rank test), and 492.3 ± 280.9% (p = 0.01; Wilcoxon signed-rank test) in response to depolarizing current injections at 50, 100, and 150 (pA) re: threshold, respectively (n = 6; Wilcoxon signed-rank test). The post-hearing onset MNTB neurons showed no change in RMP (Fig. 4F), ITHRESH, or the APCOUNT in the presence of Oxo-M, consistent with ACh application in the presence of MEC results (Fig. 2E–H). These data collectively demonstrate that cholinergic signaling modulates RMP, ITHRESH, and APCOUNT. These changes are most prominent in pre-hearing MNTB neurons, and mAChRs are the most potent mediators of ACh modulation. This suggests that mAChR activation increases membrane excitability in pre-hearing MNTB neurons, while the post-hearing MNTB neuron excitability becomes insensitive to muscarinic manipulation, demonstrating a developmental shift in cholinergic signaling mechanisms after hearing onset.

Figure 4.

Application of mAChRs agonist alone increases excitability of MNTB neurons prior to hearing onset. A, Illustration of a single MNTB neuron from a P11 gerbil in response to 1 mM Oxo-M, a muscarinic agonist. The top panels show the current-clamp traces. Traces from the step labeled in red are isolated in the bottom panels, showing the increase of AP in response to Oxo-M application. B, Population data show that in pre-hearing onset MNTB neurons, the RMP was reversibly depolarized in response to Oxo-M (F(2,10) = 10.74; p = 0.003; repeated-measures ANOVA). C, The ITHRESH is lowered in response to Oxo-M (F(2, 10) = 10.82; p = 0.003; repeated-measures ANOVA). D, The APCOUNT was elevated at supra-threshold after mAChR activation on pre-hearing MNTBs. E, Single cell traces from a P18 gerbil show the lack of muscarinic effect on AP firing rate. All four cells from post-hearing animals showed no change in APCOUNT or ITHRESH (population data not shown), neither did the RMP (panel F; F(2, 6) = 2.80; p = 0.13; repeated-measures ANOVA), suggesting the shift of muscarinic dependency during development around hearing-onset. *p < 0.05.

To further probe mAChR-coupled ion channel mechanisms underlying cholinergic modulation of MNTB excitability, we conducted voltage-clamp experiments with Oxo-M to investigate its effect on membrane conductances. Cells were voltage clamped at a holding voltage of −60 mV followed by 200 ms voltage steps ranging from −100 to +20 mV in 10 mV increments. The steady-state current near the end of voltage steps (−10 ms, vertical dashed line) were extracted for voltage analysis (Fig. 5B,D). Unsurprisingly, application of Oxo-M did not affect post-hearing onset MNTB neurons. However, in pre-hearing onset cells, Oxo-M reduced outward currents over the −40 to 20 mV range. This voltage range bound outward current modulation suggested voltage-dependent K+ conductances as downstream targets of muscarinic activation. Further, the reduction in outward current is consistent with the enhanced membrane excitability and RMP changes that we observed during ACh application.

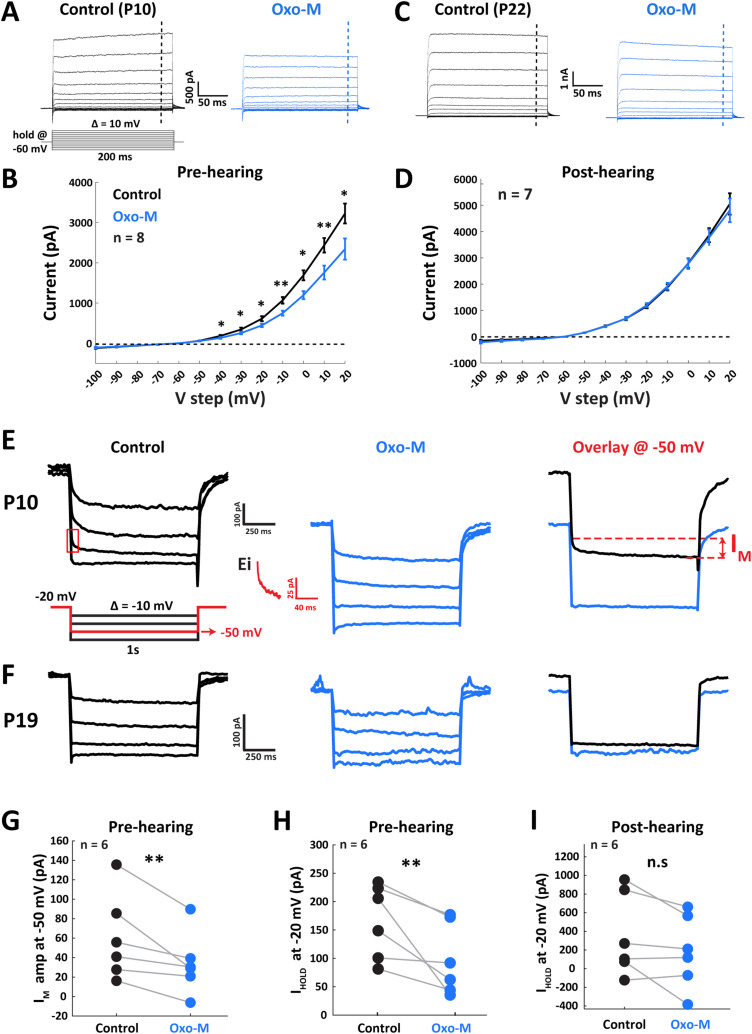

Figure 5.

Voltage-dependent outward potassium current M-current (IM) from MNTB neuron was decreased by muscarinic activation prior to hearing onset. A, Voltage-clamp traces from a single MNTB neuron from P10 gerbil before (left) and after (right) 1 mM Oxo-M application. Dashed vertical lines indicate the extracted current value for I–V function. B, Population I–V function from pre-hearing age group shows a decrease of outward current in response to Oxo-M. C, Voltage-clamp traces from a single MNTB neuron with Oxo-M treatment from P22 gerbil. D, Population I–V function from post-hearing age group shows no change in current amplitudes before and after Oxo-M treatment. E, Example traces from a P10 neuron show the isolation of IM (left) and the diminishment of IM after Oxo-M application (middle). Illustration of the initial relaxation of IM when neuron was hyperpolarized from −20 to −50 mV step is shown in inset on the left panel (Ei). An overlay of control and Oxo-M conditions on the right panel shows that the muscarinic activation decreased the IM amplitude and at the same time, reduced the IHOLD at −20 mV. F, A lack of prominent IM-dependent deactivation in control conditions was observed from a P19 neuron. G, Population data from pre-hearing cells show a significant reduction of IM amplitude after muscarinic activation. H, Population data from pre-hearing cells shows a significant decrease of IHOLD at −20 mV, suggesting an increase in input resistance in response to Oxo-M. I, Population data from post-hearing MNTB neurons show that the IHOLD-20 was not affected by Oxo-M, suggesting a lack of muscarinic effect on input resistance. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

Among voltage-gated channels known to be physiologically coupled to mAChRs, the M-channel, known as Kv7 or KCNQ channel, is the only one that conducts outward K+ current (Brown and Adams, 1980). Therefore, we further investigated the electrophysiological effects of Oxo-M on M-channel currents (Fig. 5E,F) by using voltage step protocols developed by Brown and Adams (1980) and Martinello et al. (2015). MNTB neurons were initially held at −20 mV, a potential expected to fully activate M-channels, and then stepped to a series of hyperpolarized voltages (−30 to −60 mV in 10 mV steps) that enabled the observation of M-channel deactivation. Clear hallmarks of IM deactivation were observed in pre-hearing onset neurons over a range of 18–138 mV while post-hearing neurons exhibited almost no evidence of modulation of IM across the entire voltage range. We then examined the effect of Oxo-M on IM at the −50 mV step, a voltage value that demonstrated robust IM activity in the pre-hearing onset group. In five of these MNTB neurons, IM was significantly decreased from 69.1 ± 19.2 to 41.9 ± 12.3 pA, yielding a 36.0 ± 7.7% reduction (Fig. 5G; p = 0.048; paired t test). In one additional pre-hearing onset neuron, the inward relaxation phase after hyperpolarizing step (Fig. 5E, right panel, between two dashed lines) was missing after Oxo-M application (e.g., the bottom trace of middle panel in Fig. 5E), returning a negative value. We could not attribute this hyperpolarization-induced current to IM, and thus it was not included in the population analysis.

Overall, our results examining IM-like currents were in accordance with the previously shown reduction of total outward current by mAChR activation (Fig. 5B). We then assessed the membrane conductance by comparing the amount of current injected to hold the cell at −20 mV (IHOLD-20; Fig. 5I). IHOLD-20 current significantly decreased from 163.9 ± 26.7 to 95.4 ± 25.8 pA, yielding a 40.9 ± 11.3% reduction in response to Oxo-M application (Fig. 5H; n = 6; p = 0.03; paired t test). This value did not change significantly (p = 0.10; paired t test) in the post-hearing onset neurons. These results suggest that the primary muscarinic effects on M-channels are to decrease outward conductances of MNTB neurons prior to hearing onset.

Muscarinic modulation of pre-hearing MNTB neurons depends on inactivation of M-channel (Kv7)

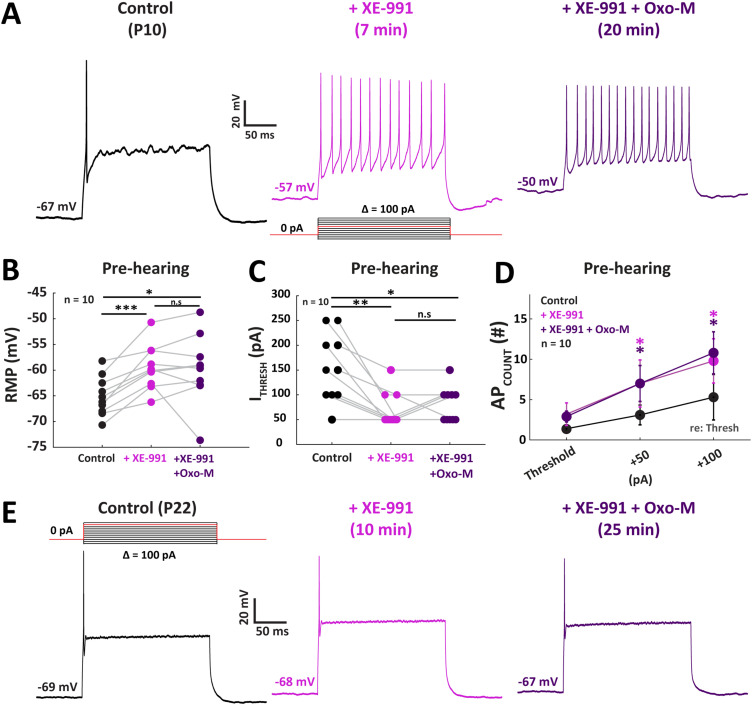

We showed that muscarinic agonist primarily enhanced the excitability of the pre-hearing onset MNTB neurons by decreasing IM-like currents, consistent with known Kv7 channel physiology. Therefore, we hypothesized that direct pharmacological inactivation of M-channels (Kv7) would have similar effects on neuron excitability to ACh or Oxo-M treatment. We applied XE-991, a Kv7-specific antagonist, to compare its effects on the excitability of MNTB neurons from both age groups to Oxo-M treatment (Wang et al., 1998; Zaczek et al., 1998). In current clamp, application of XE-991 (1 mM) increased the average spike count of pre-hearing onset neurons by 126 ± 55.3% (n = 10; p = 0.03; Tukey's post hoc) and 85 ± 44.4% (p = 0.048; Tukey's post hoc) after +50 and +100 pA re: threshold depolarizing current injections, respectively (Fig. 6A). Kv7 inactivation depolarized RMP significantly, from −65.1 ± 1.3 to −59.4 ± 1.4 mV after XE-991 application (Fig. 6B; n = 10; p = 0.0005; Tukey's post hoc test). The average ITHRESH decreased 55 ± 13% in response to XE-991 from 155 ± 22 to 70 ± 11 pA (Fig. 6C; n = 10; p = 0.005; Tukey's post hoc). We then tested the effect of XE-991 alone and compared results with simultaneous XE-991 and Oxo-M application treatments on RMP, ITHRESH, and APCOUNT of pre-hearing MNTB neurons. Co-application of Oxo-M in the presence of XE-991 yielded no additional change to the average RMP of −59.8 ± 1.4 mV, compared with the XE-991 alone condition (n = 10; p = 0.95; Tukey's post hoc). Co-application of Oxo-M also yielded no additional effect on ITHRESH (80 ± 11 pA; p = 0.60; Tukey's post hoc). The APCOUNT did not change significantly after co-applying Oxo-M either, with a 126 ± 44.7% change at +50 pA re: threshold and a 104 ± 32.1% change at +100 pA re: threshold (p > 0.9; Tukey's post hoc test; Fig. 6D).

Figure 6.

Excitability of MNTB neurons is enhanced by pharmacologically inhibiting Kv7 channel in early development. A, Example current-clamp traces from a P10 neuron showed an increase of AP firing and depolarization of RMP in response to application of 1 mM XE-991, a Kv7 antagonist. Subsequent co-application with 1 mM Oxo-M did not confer additional excitatory enhancement. B, Inhibition of Kv7 significantly depolarized RMP (F(1.33, 11.94) = 10.05; p = 0.005; repeated-measures ANOVA), again dual-drug treatment did not produce further effects. C, XE-991 lowered the ITHRESH on a population level (F(1.35, 12.14) = 13.63; p = 0.0017; repeated-measures ANOVA), and no effect was observed following Oxo-M addition. D, The APCOUNT function shows a significant increase of responsiveness to injection current after XE-991 application, and addition of Oxo-M did not further increase the APCOUNT at either +50 pA re: threshold (F(1.68, 15.15) = 4.86; p = 0.028; repeated-measures ANOVA) or +100 pA re: threshold injection current (F(1.56, 14.02) = 4.73; p = 0.034; repeated-measures ANOVA). E, Current-clamp traces from a P22 MNTB exhibited no sensitivity to XE-991, nor the addition of Oxo-M. The lack of muscarinic effect on excitability was accompanied by the lack of change in RMP (data not shown; F(2, 6) = 1.39; p = 0.32; repeated-measures ANOVA). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

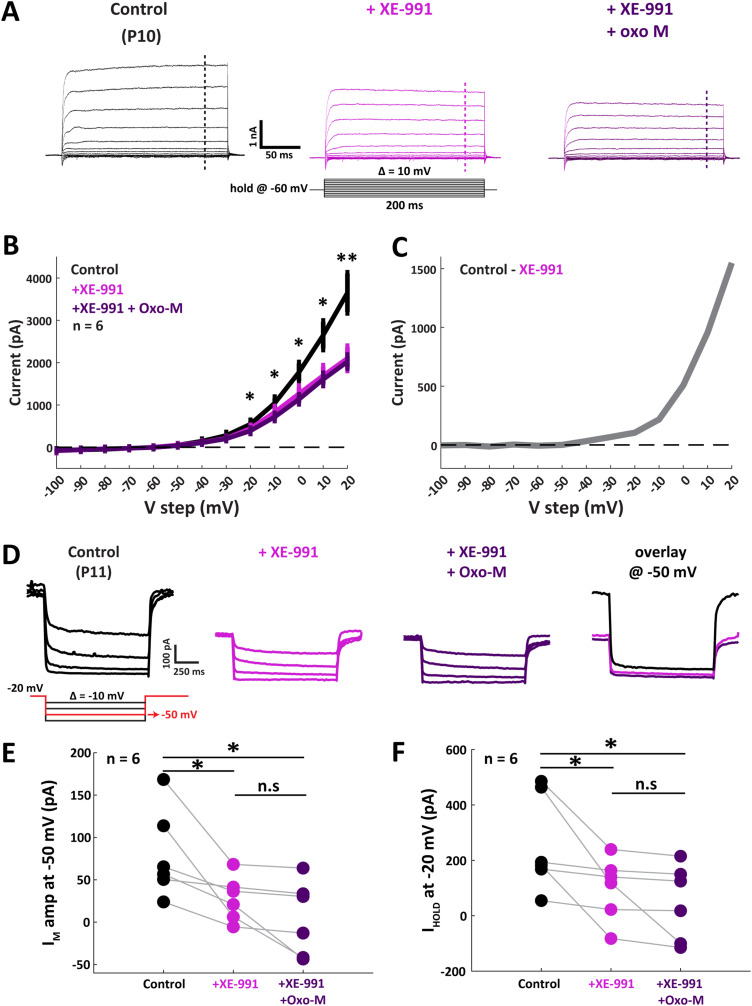

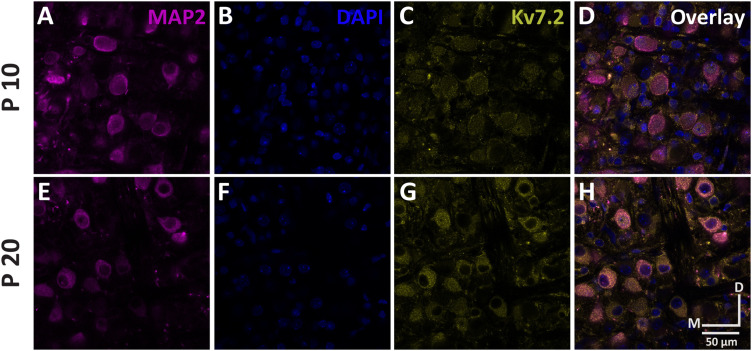

The negligible additional contribution of Oxo-M co-application following XE-991 alone strongly suggests that Kv7 is the primary downstream effector in muscarinic modulation of MNTB neurons. Accordingly, post-hearing onset neurons showed no significant change in RMP during XE-991-only treatment (from −59.3 ± 4.6 to −59.0 ± 5.1 mV; n = 4; p = 0.77; Tukey's post hoc), nor in the dual-drug treatment (−57.1 ± 5.7 mV; p = 0.25; Tukey's post hoc). Similarly, neither ITHRESH nor APCOUNT changed in response to XE-991 application (Fig. 6E). These results suggest that mAChR inactivation of Kv7 enhances excitability primarily in pre-hearing onset MNTB neurons. To further confirm the principal role of Kv7 inactivation to overall cholinergic modulation observed in these neurons, we directly tested the effects of XE-991 applied either alone or together with Oxo-M on IM currents recorded in voltage clamp in pre-hearing onset MNTB neurons (Fig. 7A). Voltage-clamp protocols were the same as shown previously in Figure 5 for the Oxo-M-only treatments. Application of XE-991 decreased the outward K+ current at depolarizing steps within the −20 to 20 mV range (Fig. 7B,C). The expression of Kv7.2 receptor subunits were confirmed by IHC (Fig. 8). We examined both pre- and post-hearing tissue and found expression across development in the MNTB. We then examined the effect of inactivating Kv7 with XE-991 using the Brown and Adams (1980) IM protocol (Fig. 7D). The average IM amplitude decreased from 79.8 ± 21.4 to 29.8 ± 9.8 pA in response to XE-991 treatment (Fig. 7E; n = 6; p = 0.04; paired t test). In two neurons, the negative value yielded after further addition of Oxo-M was considered to be unattributable to IM and thus not included in population analysis. Furthermore, the IHOLD-20 was compared among control, XE-991-only, and dual-drug treatment. XE-991 decreased the IHOLD-20 from 257.8 ± 71.5 to 100.2 ± 46.4 pA (Fig. 7F; p = 0.04; Tukey's post hoc test), while no significant change was observed after Oxo-M addition (p = 0.19; Tukey's post hoc test). This result indicates that inactivation of Kv7 yielded similar physiological changes to those observed during activation of muscarinic receptors, while subsequent Oxo-M application did not generate additional modulation on MNTB neurons. Together, these results suggest that mAChR coupling to Kv7 inactivation is the primary mechanism of mAChR-dependent modulation prior to hearing onset.

Figure 7.

Inactivation of Kv7 decreased outward IM current in pre-hearing MNTB. A, Voltage-clamp traces from a single MNTB neuron from a P10 gerbil in the control condition (left), post XE-991 application (middle), and post dual-drug treatment (right). Dashed vertical lines indicate the extracted current value for I–V function. B, Population I–V function from pre-hearing age group shows the decrease of outward potassium current in response to XE-991, but not with Oxo-M addition. C, Activation curve of XE-991-sensitive current, yielded by subtracting average XE-991 trace from control trace in panel B. D, Example traces from a P11 neuron show the isolation of IM and the muscarinic effect on IM after XE-991 and dual-drug treatment. Overlay panel (right) shows that the Kv7 inactivation decreased the IM amplitude and reduced the IHOLD at −20 mV. E, Population data from six pre-hearing cells show a significant reduction of IM amplitude after Kv7 inactivation, which did not change after Oxo-M addition. F, XE-991 decreased IHOLD-20, and addition of Oxo-M did not further change the outcome (F(2, 10) = 5.94; p = 0.02; repeated-measures ANOVA). *p < 0.05.

Figure 8.

Immunohistochemistry confirms Kv7.2 expression. Expression of Kv7.2 in a P10 (A–D) and a P20 (E–H) gerbil MNTB. The 50 μm coronal slices were obtained from PFA fixed tissues. Magenta indicates MAP2 staining (A,E), blue represents DAPI staining (B,F), yellow indicates Kv7.2 label (C,G), and the right column panels (D,H) are the overlay. Immunofluorescence for Kv7.2 was absent in tissue processed without primary antibodies (data not shown). Images were obtained with confocal microscopy at 40× magnification. Scale bar, 50 μm; D, dorsal; M, medial; n = 8.

mAChRs are expressed in the MNTB

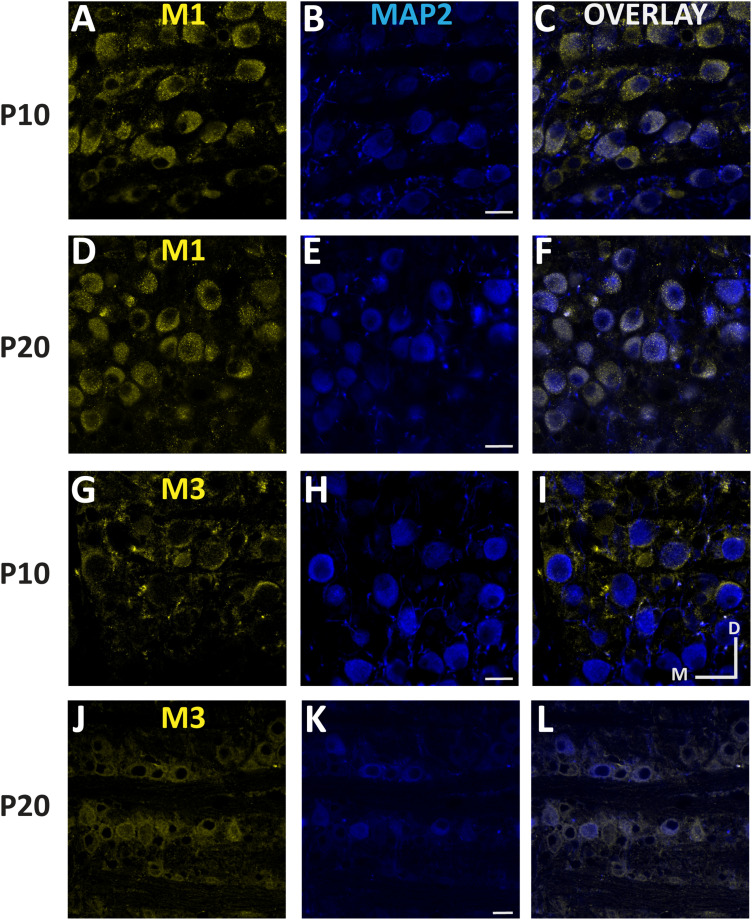

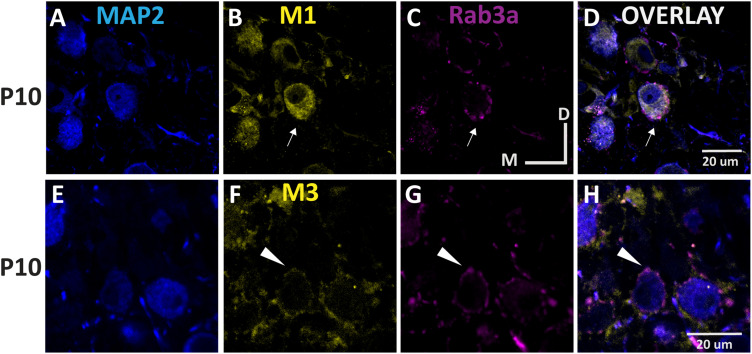

To our knowledge, there has been no prior documentation of mAChR expression in the MNTB. Our physiological recordings suggest mAChR activation suppressed outward currents, likely via Kv7 inactivation, and IHC confirmed the presence of Kv7 protein expression in MNTB neurons. Of the five known mAChR receptor types, M1 is the most closely associated with potassium channel inactivation (Brown, 2010; McCormick and Prince, 1986; McCormick and Williamson, 1989; Womble and Moises, 1992), while M2 and M4 are known to be inhibitory (Biscoe and Straughan, 1966; Eggermann and Feldmeyer, 2009) and M5 is most closely associated with dopaminergic neurons (Levey et al., 1991; Bubser et al., 2012). We performed IHC with antibodies against M1 and M3 AChR subunits (Fig. 9) in tissue from pre- and post-hearing onset subjects (n = 4 animals per group). Anti-M1 labeling was robust in both pre-hearing (Fig. 9A–C) and post-hearing (Fig. 9D–F) onset groups and exhibited primarily postsynaptic expression at both ages. M3 AChR subunits were also expressed in both groups (Fig. 9G–L) but appeared to be preferentially localized to presynaptic terminals in the pre-hearing group (Fig. 9I). To confirm the presynaptic or postsynaptic localization of the M3 and M1 receptors, respectively, we co-labeled M1 and M3 receptors with antibody to Rab3a, a known presynaptic marker in pre-hearing tissue from n = 4 animals in both age groups. M1 labeling was evident on the MNTB soma and did not colocalize with synaptic terminals (Fig. 10A–D). In contrast M3 expression appeared absent in P10 somas but was clearly associated with presynaptic terminals (Fig. 10E–H). The presynaptic distribution of M3 receptors in young tissue does not support the hypothesis that they contribute to membrane excitability in the postsynaptic neuron. In contrast, the M1 labeling patterns were most consistent with the physiological changes that we observed in response to ACh application.

Figure 9.

Immunohistochemical labeling for muscarinic acetylcholine receptor (mAChR) subtypes 1 (M1; n = 8) and 3 (M3; n = 8). Expression in a P10 (A–C,G–I) and a P20 (D–F,J–L) gerbil MNTB. The 50 μm coronal slices were obtained from PFA fixed tissues. Yellow indicates mAChR staining and blue represents MAP2 staining. The right column (C,F,I,L) are the merged overlay. A–F, Images of M1 AChR expression in P10 (A–C) and P20 (D–F) gerbils. M1 expression is robust and appears to be somatic at both pre- and post-hearing onset. (G–L) Images of M3 AChR expression in P10 (G–I) and P20 (J–L) gerbils are suggestive of presynaptic localization of M3 in the pre-hearing group. Immunofluorescence for mAChRs was absent in tissue processed without primary antibodies (data not shown). Images were obtained with confocal microscopy at 40× magnification. Scale bar, 20 μm; D, dorsal; M, medial.

Figure 10.

M3 colocalizes with presynaptic marker Rab3A at P10 while M1 does not. A–D, Co-immunolabel of M1 (n = 4) with the presynaptic marker Rab3A and (E–H) M3 (n = 4) in the P10 gerbil. The 50 μm coronal slices were obtained from PFA fixed tissues. Blue indicates MAP2 staining (A,E), yellow indicates M1 and M3 label (B,F), magenta indicates Rab3A (C,G), and the right column panels (D,H) are merged images. The white arrowheads (F–H) indicate colocalized presynaptic staining pattern of M3/Rab3a at P10 in contrast to the predominantly independent postsynaptic expression of M1 (arrows, A–D) at the same age. Images were obtained with confocal microscopy at 63× magnification. Scale bar, 20 μm; D, dorsal; M, medial.

Discussion

In this report, we demonstrate that cholinergic modulation enhances excitability of gerbil MNTB neurons through two receptor mechanisms that vary in impact with developmental stage. First, prior to hearing onset, muscarinic receptors strongly modulate membrane excitability, and this effect is markedly reduced following the first week of hearing. The age-constrained muscarinic modulation is developmentally coincident with a period of dramatic refinement of auditory circuitry involving several physiological and morphological processes in the SOC (Kandler and Gillespie, 2005; Pallas et al., 2006). We demonstrated that this muscarinic modulation is mediated by inactivation of XE-991-sensitive, KCNQ (Kv7) channels, a voltage-gated K+ conductance. This inactivation results in changes to membrane potential, threshold, and input response gain of MNTB neurons. Nicotinic receptor-dependent modulation emerges approximately a week after hearing onset, mediating a more moderate influence on excitability. Based on our previous study, this nicotinic modulation appears to persist into adulthood (Zhang et al., 2021). Our IHC results largely complement physiological observations and confirm expression of M1 and M3 AChR subtypes as well as the Kv7.2 subunit of the KCNQ channel. KCNQ genes code the Kv7 family with subunits 1–5. Kv7.2–7.5 are expressed in the nervous system (Jentsch, 2000; Robbins, 2001). M-channels are composed of Kv7.2 and Kv7.3 heteromers (Wang et al., 1998). Together, the data reveal a previously undescribed and strong modulatory influence on the MNTB that transiently appears during development.

Muscarinic modulation and Kv7 expression are prominent in the auditory system

Cholinergic modulation of both resting potential and spike probability in response to synaptic stimulation has been observed in the physiologically similar spherical bushy cells of the CN (Goyer et al., 2016). Our findings concur and show depolarizing RMPs and reduced thresholds in MNTB neurons during application of mAChR agonist. We further concluded that Kv7 is the primary effector of muscarinic modulation in MNTB. A previous study showed that Kv7.5 channels enhance transmitter release in rat calyx of Held (Huang and Trussell, 2011). Kv7 family channel expression has also been documented in several other auditory regions including hair cells, CN, and lemniscal nuclei (NLL; Kharkovets et al., 2000), inferior colliculus (Wang et al., 1998; Kharkovets et al., 2000), and primary neurons in SOC nuclei including the LSO, MSO, SPN, and MNTB (Caminos et al., 2007; Garcia-Pino et al., 2010).

Our conclusion that Kv7 channel inactivation is responsible for the developmentally transient enhancement of MNTB excitability is based on the observation that co-application of Kv7 antagonist following the application of mAChRs agonist alone yielded little to no additive effect, while similar changes in excitability were observed following application of each drug individually. Interestingly, IHC data did not indicate an accompanying reduction in protein expression of either mAChRs or Kv7.2 subunits over this period. It is thus possible that mAChR-coupled secondary messengers upstream of Kv7.2 could be developmentally regulated and alternatively impact the physiological state of Kv7.2 (Delmas and Brown, 2005; Soldovieri et al., 2011; Jepps et al., 2021).

Nicotinic modulation follows a complementary developmental pattern

We previously showed that in mature gerbils, in vivo sound-evoked responses are enhanced by nAChR activation in MNTB neurons, contributing to the efficacy of encoding sound intensity and detection of tones in noise (Zhang et al., 2021). Here we observed a lack of muscarinic influence on excitability after P18. Instead, a moderate nicotinic effect emerged by P18 that was not present in the younger age group. In the in vivo study of adult gerbils, the nicotinic component contributed to a maximum of ∼35% of the sound-evoked spike rate. Our in vitro results showed a 200–1,500% increase in spike rate to the strongest depolarizing current steps, a range that is putatively sufficient to explain the in vivo observations, albeit under very different experimental conditions. Taken together, these complementary muscarinic and nicotinic mechanisms of modulation appear to occur in distinct age ranges. While nicotinic modulation has a demonstrated role in sound encoding, muscarinic modulation appears more likely to serve a transient function during development. One caveat to this general conclusion is that the current study focused only on postsynaptic membrane properties; thus the question of whether cholinergic receptors influence synaptic transmission at this age requires further investigation.

Simultaneous morphological changes accompany physiological modulation at pre-hearing onset period

Concurrent with the period of muscarinic modulation MNTB described in this study, the calyx of Held undergoes dramatic morphological and physiological refinement prior to P21 (Taschenberger and von Gersdorff, 2000; Ford et al., 2009), which facilitate high fidelity responses to phase-locked input. Similar morphological changes during development were observed at cat endbulb of Held synapses on bushy cells (Ryugo and Fekete, 1982; Ryugo et al., 2006). Interestingly, in both cases, the refinement process was disrupted by abolition of ascending activity prior to hearing onset (Ryugo et al., 1997; Ford et al., 2009). These common developmental features suggest a dynamic, activity-dependent developmental refinement that relies on the integrity of the ascending auditory pathway. In congenitally deaf mice whose ascending auditory pathway is disrupted, MNTB neurons exhibit abnormal synaptic structure and membrane properties compared with normal-hearing mice prior to hearing onset, further suggesting the significance of intact auditory pathway during early development (Leao et al., 2004, 2006). The potent muscarinic expression and modulation described in this study is temporally and functionally well positioned to contribute to the refinement process, but confirmation of this developmental role will require empirical testing.

Cholinergic function in brainstem auditory neurons

The function of ACh has been most well studied in high-ordered brain areas that are responsible for attention, memory, and cognitive functions such as the thalamus (reviewed in Richardson et al., 2021) and auditory cortex (reviewed in Froemke, 2015). In contrast, low-ordered sensory neurons, like those of the MNTB, feature cholinergic signaling that is poised to exert functionally significant influences on acoustic gain control (Guinan, 1996; Darrow et al., 2006, 2007), stimulation encoding (Ayala and Malmierca, 2015; Goyer et al., 2016), noise protection (Maison et al., 2010; Wolpert et al., 2014), and signal detection (Zhang et al., 2021). In the present study, we have further shown a developmentally transient involvement of ACh in modulating neural excitability.

In addition to its putative potential to shape development, cholinergic modulation could also contribute to sustaining MNTB responses to weak synaptic input prevalent in the immature calyx. It is well established that in early development, the calyx of Held exhibits strong synaptic depression during sustained activity that leads to postsynaptic response failures (Taschenberger and von Gersdorff, 2000). It is therefore possible that one function of the cholinergic enhancement of membrane excitability is to preserve postsynaptic responses in neurons receiving chronically depressed synaptic input during sustained synaptic activity. Such activity could derive from either spontaneous or sound-driven input in the early hearing onset period (Babola et al., 2018). Indeed, our previous findings suggested that some sources of cholinergic input to MNTB derive from neurons that are driven by auditory input (Beebe et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2021).

Taken together with our previous work, the current study reveals additional mechanisms by which cholinergic modulation influences input encoding by MNTB neurons, albeit during a specific and formative developmental period. Our demonstration of muscarinic inactivation of Kv7 channels provides mechanistic insight into a novel modulatory influence on MNTB physiology that may shape development or sustain entrainment and encoding in immature circuitry. These findings also indicate that cholinergic modulation is well poised to contribute to developmental circuit refinement, but establishment of this role will depend on future developmental investigation.

References

- Adams JC, Mugnaini E (1990) Immunocytochemical evidence for inhibitory and disinhibitory circuits in the superior olive. Hear Res 49:281–298. 10.1016/0378-5955(90)90109-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkondon M, Pereira EF, Barbosa CT, Albuquerque EX (1997) Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor activation modulates gamma-aminobutyric acid release from CA1 neurons of rat hippocampal slices. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 283:1396–1411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altieri SC, Zhao T, Jalabi W, Maricich SM (2014) Development of glycinergic innervation to the murine LSO and SPN in the presence and absence of the MNTB. Front Neural Circuits 8:109. 10.3389/fncir.2014.00109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aramakis VB, Hsieh CY, Leslie FM, Metherate R (2000) A critical period for nicotine-induced disruption of synaptic development in rat auditory cortex. J Neurosci 20:6106–6116. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-16-06106.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayala YA, Malmierca MS (2015) Cholinergic modulation of stimulus-specific adaptation in the inferior colliculus. J Neurosci 35:12261–12272. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0909-15.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babola TA, Li S, Gribizis A, Lee BJ, Issa JB, Wang HC, Crair MC, Bergles DE (2018) Homeostatic control of spontaneous activity in the developing auditory system. Neuron 99:511–524.e5. 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.07.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks MI, Smith PH (1992) Intracellular recordings from neurobiotin-labeled cells in brain slices of the rat medial nucleus of the trapezoid body. J Neurosci 12:2819–2837. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-07-02819.1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batallan Burrowes AA, Olajide OJ, Iasenza IA, Shams WM, Carter F, Chapman CA (2022) Ovariectomy reduces cholinergic modulation of excitatory synaptic transmission in the rat entorhinal cortex. PLoS One 17:e0271131. 10.1371/journal.pone.0271131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beebe NL, Zhang C, Burger RM, Schofield BR (2021) Multiple sources of cholinergic input to the superior olivary complex. Front Neural Circuits 15:715369. 10.3389/fncir.2021.715369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg DK, Conroy WG (2002) Nicotinic alpha 7 receptors: synaptic options and downstream signaling in neurons. J Neurobiol 53:512–523. 10.1002/neu.10116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birdsall NJ, Burgen AS, Hulme EC (1978) The binding of agonists to brain muscarinic receptors. Mol Pharmacol 14:723–736. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biscoe TJ, Straughan DW (1966) Micro-electrophoretic studies of neurones in the cat hippocampus. J Physiol 183:341–359. 10.1113/jphysiol.1966.sp007869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DA (2010) Muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (mAChRs) in the nervous system: some functions and mechanisms. J Mol Neurosci 41:340–346. 10.1007/s12031-010-9377-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DA (2018) Regulation of neural ion channels by muscarinic receptors. Neuropharmacology 136:383–400. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2017.11.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DA, Adams PR (1980) Muscarinic suppression of a novel voltage-sensitive K+ current in a vertebrate neurone. Nature 283:673–676. 10.1038/283673a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bubser M, Byun N, Wood MR, Jones CK (2012) Muscarinic receptor pharmacology and circuitry for the modulation of cognition. Handb Exp Pharmacol 208:121–166. 10.1007/978-3-642-23274-9_7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caminos E, Garcia-Pino E, Martinez-Galan JR, Juiz JM (2007) The potassium channel KCNQ5/Kv7.5 is localized in synaptic endings of auditory brainstem nuclei of the rat. J Comp Neurol 505:363–378. 10.1002/cne.21497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darrow KN, Maison SF, Liberman MC (2006) Cochlear efferent feedback balances interaural sensitivity. Nat Neurosci 9:1474–1476. 10.1038/nn1807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darrow KN, Maison SF, Liberman MC (2007) Selective removal of lateral olivocochlear efferents increases vulnerability to acute acoustic injury. J Neurophysiol 97:1775–1785. 10.1152/jn.00955.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delmas P, Brown DA (2005) Pathways modulating neural KCNQ/M (Kv7) potassium channels. Nat Rev Neurosci 6:850–862. 10.1038/nrn1785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Disney AA, Alasady HA, Reynolds JH (2014) Muscarinic acetylcholine receptors are expressed by most parvalbumin-immunoreactive neurons in area MT of the macaque. Brain Behav 4:431–445. 10.1002/brb3.225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggermann E, Feldmeyer D (2009) Cholinergic filtering in the recurrent excitatory microcircuit of cortical layer 4. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:11753–11758. 10.1073/pnas.0810062106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford MC, Grothe B, Klug A (2009) Fenestration of the calyx of Held occurs sequentially along the tonotopic axis, is influenced by afferent activity, and facilitates glutamate clearance. J Comp Neurol 514:92–106. 10.1002/cne.21998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froemke RC (2015) Plasticity of cortical excitatory-inhibitory balance. Annu Rev Neurosci 38:195–219. 10.1146/annurev-neuro-071714-034002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii S, Ji Z, Morita N, Sumikawa K (1999) Acute and chronic nicotine exposure differentially facilitate the induction of LTP. Brain Res 846:137–143. 10.1016/S0006-8993(99)01982-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujino K, Oertel D (2001) Cholinergic modulation of stellate cells in the mammalian ventral cochlear nucleus. J Neurosci 21:7372–7383. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-18-07372.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Pino E, Caminos E, Juiz JM (2010) KCNQ5 reaches synaptic endings in the auditory brainstem at hearing onset and targeting maintenance is activity-dependent. J Comp Neurol 518:1301–1314. 10.1002/cne.22276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge S, Dani JA (2005) Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors at glutamate synapses facilitate long-term depression or potentiation. J Neurosci 25:6084–6091. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0542-05.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillet C, Goyer D, Kurth S, Griebel H, Kuenzel T (2018) Cholinergic innervation of principal neurons in the cochlear nucleus of the Mongolian gerbil. J Comp Neurol 526:1647–1661. 10.1002/cne.24433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillet C, Kurth S, Kuenzel T (2020) Muscarinic modulation of M and h currents in gerbil spherical bushy cells. PLoS One 15:e0226954. 10.1371/journal.pone.0226954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyer D, Kurth S, Gillet C, Keine C, Rubsamen R, Kuenzel T (2016) Slow cholinergic modulation of spike probability in ultra-fast time-coding sensory neurons. eNeuro 3. 10.1523/ENEURO.0186-16.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray R, Rajan AS, Radcliffe KA, Yakehiro M, Dani JA (1996) Hippocampal synaptic transmission enhanced by low concentrations of nicotine. Nature 383:713–716. 10.1038/383713a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grothe B, Pecka M, McAlpine D (2010) Mechanisms of sound localization in mammals. Physiol Rev 90:983–1012. 10.1152/physrev.00026.2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guinan JJ (1996) Physiology of olivocochlear efferents. In: The cochlea (Dallos P, Popper AN, Fay RR, eds), pp 435–502. New York, NY: Springer New York. [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell JV, Adams PR (1982) Voltage-clamp analysis of muscarinic excitation in hippocampal neurons. Brain Res 250:71–92. 10.1016/0006-8993(82)90954-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Happe HK, Morley BJ (2004) Distribution and postnatal development of alpha 7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the rodent lower auditory brainstem. Brain Res Dev Brain Res 153:29–37. 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2004.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H, Trussell LO (2011) KCNQ5 channels control resting properties and release probability of a synapse. Nat Neurosci 14:840–847. 10.1038/nn.2830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins PM, Kim N, Jones SL, Tseng WC, Svitkina TM, Yin HH, Bennett V (2015) Giant ankyrin-G: a critical innovation in vertebrate evolution of fast and integrated neuronal signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:957–964. 10.1073/pnas.1416544112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jentsch TJ (2000) Neuronal KCNQ potassium channels: physiology and role in disease. Nat Rev Neurosci 1:21–30. 10.1038/35036198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jepps TA, Barrese V, Miceli F (2021) Editorial: kv7 channels: structure, physiology, and pharmacology. Front Physiol 12:679317. 10.3389/fphys.2021.679317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji D, Lape R, Dani JA (2001) Timing and location of nicotinic activity enhances or depresses hippocampal synaptic plasticity. Neuron 31:131–141. 10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00332-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandler K, Friauf E (1995a) Development of electrical membrane properties and discharge characteristics of superior olivary complex neurons in fetal and postnatal rats. Eur J Neurosci 7:1773–1790. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1995.tb00697.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandler K, Friauf E (1995b) Development of glycinergic and glutamatergic synaptic transmission in the auditory brainstem of perinatal rats. J Neurosci 15:6890–6904. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-10-06890.1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandler K, Gillespie DC (2005) Developmental refinement of inhibitory sound-localization circuits. Trends Neurosci 28:290–296. 10.1016/j.tins.2005.04.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kharkovets T, Hardelin JP, Safieddine S, Schweizer M, El-Amraoui A, Petit C, Jentsch TJ (2000) KCNQ4, a K+ channel mutated in a form of dominant deafness, is expressed in the inner ear and the central auditory pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:4333–4338. 10.1073/pnas.97.8.4333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim G, Kandler K (2003) Elimination and strengthening of glycinergic/GABAergic connections during tonotopic map formation. Nat Neurosci 6:282–290. 10.1038/nn1015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JE, Seol A, Choi YJ, Lee SJ, Jin YJ, Roh YJ, Song HJ, Hong JT, Hwang DY (2022) Similarities and differences in constipation phenotypes between lep knockout mice and high fat diet-induced obesity mice. PLoS One 17:e0276445. 10.1371/journal.pone.0276445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koka K, Tollin DJ (2014) Linear coding of complex sound spectra by discharge rate in neurons of the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body (MNTB) and its inputs. Front Neural Circuits 8:144. 10.3389/fncir.2014.00144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp-Scheinpflug C, Tozer AJ, Robinson SW, Tempel BL, Hennig MH, Forsythe ID (2011) The sound of silence: ionic mechanisms encoding sound termination. Neuron 71:911–925. 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.06.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krnjevic K, Pumain R, Renaud L (1971) The mechanism of excitation by acetylcholine in the cerebral cortex. J Physiol 215:247–268. 10.1113/jphysiol.1971.sp009467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leao RN, Naves MM, Leao KE, Walmsley B (2006) Altered sodium currents in auditory neurons of congenitally deaf mice. Eur J Neurosci 24:1137–1146. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04982.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leao RN, Oleskevich S, Sun H, Bautista M, Fyffe RE, Walmsley B (2004) Differences in glycinergic mIPSCs in the auditory brain stem of normal and congenitally deaf neonatal mice. J Neurophysiol 91:1006–1012. 10.1152/jn.00771.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levey AI, Kitt CA, Simonds WF, Price DL, Brann MR (1991) Identification and localization of muscarinic acetylcholine receptor proteins in brain with subtype-specific antibodies. J Neurosci 11:3218–3226. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-10-03218.1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madison DV, Lancaster B, Nicoll RA (1987) Voltage clamp analysis of cholinergic action in the hippocampus. J Neurosci 7:733–741. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-03-00733.1987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maison SF, Liu XP, Vetter DE, Eatock RA, Nathanson NM, Wess J, Liberman MC (2010) Muscarinic signaling in the cochlea: presynaptic and postsynaptic effects on efferent feedback and afferent excitability. J Neurosci 30:6751–6762. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5080-09.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinello K, Huang Z, Lujan R, Tran B, Watanabe M, Cooper EC, Brown DA, Shah MM (2015) Cholinergic afferent stimulation induces axonal function plasticity in adult hippocampal granule cells. Neuron 85:346–363. 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.12.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick DA, Prince DA (1986) Mechanisms of action of acetylcholine in the guinea-pig cerebral cortex in vitro. J Physiol 375:169–194. 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp016112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick DA, Williamson A (1989) Convergence and divergence of neurotransmitter action in human cerebral cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 86:8098–8102. 10.1073/pnas.86.20.8098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGehee DS, Heath MJ, Gelber S, Devay P, Role LW (1995) Nicotine enhancement of fast excitatory synaptic transmission in CNS by presynaptic receptors. Science 269:1692–1696. 10.1126/science.7569895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olianas MC, Dedoni S, Onali P (2014) Involvement of store-operated Ca(2+) entry in activation of AMP-activated protein kinase and stimulation of glucose uptake by M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors in human neuroblastoma cells. Biochim Biophys Acta 1843:3004–3017. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olianas MC, Dedoni S, Onali P (2016) Protection from interferon-beta-induced neuronal apoptosis through stimulation of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors coupled to ERK1/2 activation. Br J Pharmacol 173:2910–2928. 10.1111/bph.13570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pablo JL, Pitt GS (2017) FGF14 is a regulator of KCNQ2/3 channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114:154–159. 10.1073/pnas.1610158114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallas SL, Wenner P, Gonzalez-Islas C, Fagiolini M, Razak KA, Kim G, Sanes D, Roerig B (2006) Developmental plasticity of inhibitory circuitry. J Neurosci 26:10358–10361. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3516-06.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park TJ, Grothe B, Pollak GD, Schuller G, Koch U (1996) Neural delays shape selectivity to interaural intensity differences in the lateral superior olive. J Neurosci 16:6554–6566. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-20-06554.1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pecka M, Brand A, Behrend O, Grothe B (2008) Interaural time difference processing in the mammalian medial superior olive: the role of glycinergic inhibition. J Neurosci 28:6914–6925. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1660-08.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson BD, Sottile SY, Caspary DM (2021) Mechanisms of GABAergic and cholinergic neurotransmission in auditory thalamus: impact of aging. Hear Res 402:108003. 10.1016/j.heares.2020.108003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins J (2001) KCNQ potassium channels: physiology, pathophysiology, and pharmacology. Pharmacol Ther 90:1–19. 10.1016/S0163-7258(01)00116-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Contreras A, van Hoeve JS, Habets RL, Locher H, Borst JG (2008) Dynamic development of the calyx of Held synapse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:5603–5608. 10.1073/pnas.0801395105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryugo DK, Fekete DM (1982) Morphology of primary axosomatic endings in the anteroventral cochlear nucleus of the cat: a study of the endbulbs of Held. J Comp Neurol 210:239–257. 10.1002/cne.902100304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryugo DK, Montey KL, Wright AL, Bennett ML, Pongstaporn T (2006) Postnatal development of a large auditory nerve terminal: the endbulb of Held in cats. Hear Res 216–217:100–115. 10.1016/j.heares.2006.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryugo DK, Pongstaporn T, Huchton DM, Niparko JK (1997) Ultrastructural analysis of primary endings in deaf white cats: morphologic alterations in endbulbs of Held. J Comp Neurol 385:230–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safieddine S, Bartolami S, Wenthold RJ, Eybalin M (1996) Pre- and postsynaptic M3 muscarinic receptor mRNAs in the rodent peripheral auditory system. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 40:127–135. 10.1016/0169-328x(96)00047-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanes DH, Takacs C (1993) Activity-dependent refinement of inhibitory connections. Eur J Neurosci 5:570–574. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1993.tb00522.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott LL, Mathews PJ, Golding NL (2005) Posthearing developmental refinement of temporal processing in principal neurons of the medial superior olive. J Neurosci 25:7887–7895. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1016-05.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soldovieri MV, Miceli F, Taglialatela M (2011) Driving with no brakes: molecular pathophysiology of Kv7 potassium channels. Physiology 26:365–376. 10.1152/physiol.00009.2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer I, Lingenhohl K, Friauf E (1993) Principal cells of the rat medial nucleus of the trapezoid body: an intracellular in vivo study of their physiology and morphology. Exp Brain Res 95:223–239. 10.1007/BF00229781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spangler KM, Warr WB, Henkel CK (1985) The projections of principal cells of the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body in the cat. J Comp Neurol 238:249–262. 10.1002/cne.902380302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taschenberger H, von Gersdorff H (2000) Fine-tuning an auditory synapse for speed and fidelity: developmental changes in presynaptic waveform, EPSC kinetics, and synaptic plasticity. J Neurosci 20:9162–9173. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-24-09162.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukimi Y, Pustovit RV, Harrington AM, Garcia-Caraballo S, Brierley SM, Di Natale M, Molero JC, Furness JB (2020) Effects and sites of action of a M1 receptor positive allosteric modulator on colonic motility in rats and dogs compared with 5-HT(4) agonism and cholinesterase inhibition. Neurogastroenterol Motil 32:e13866. 10.1111/nmo.13866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verneuil J, Brocard C, Trouplin V, Villard L, Peyronnet-Roux J, Brocard F (2020) The M-current works in tandem with the persistent sodium current to set the speed of locomotion. PLoS Biol 18:e3000738. 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HS, Pan Z, Shi W, Brown BS, Wymore RS, Cohen IS, Dixon JE, McKinnon D (1998) KCNQ2 and KCNQ3 potassium channel subunits: molecular correlates of the M-channel. Science 282:1890–1893. 10.1126/science.282.5395.1890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolpert S, Heyd A, Wagner W (2014) Assessment of the noise-protective action of the olivocochlear efferents in humans. Audiol Neurootol 19:31–40. 10.1159/000354913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Womble MD, Moises HC (1992) Muscarinic inhibition of M-current and a potassium leak conductance in neurones of the rat basolateral amygdala. J Physiol 457:93–114. 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao W, Godfrey DA, Levey AI (1996) Immunolocalization of muscarinic acetylcholine subtype 2 receptors in rat cochlear nucleus. J Comp Neurol 373:27–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue P, et al. (2006) Ischemia impairs the association between connexin 43 and M3 subtype of acetylcholine muscarinic receptor (M3-mAChR) in ventricular myocytes. Cell Physiol Biochem 17:129–136. 10.1159/000092074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaczek R, Chorvat RJ, Saye JA, Pierdomenico ME, Maciag CM, Logue AR, Fisher BN, Rominger DH, Earl RA (1998) Two new potent neurotransmitter release enhancers, 10,10-bis(4-pyridinylmethyl)-9(10H)-anthracenone and 10,10-bis(2-fluoro-4-pyridinylmethyl)-9(10H)-anthracenone: comparison to linopirdine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 285:724–730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Beebe NL, Schofield BR, Pecka M, Burger RM (2021) Endogenous cholinergic signaling modulates sound-evoked responses of the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body. J Neurosci 41:674–688. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1633-20.2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]