Abstract

Objectives

To find what proportion of a broad set of health journals have published on climate change and health, how many articles they have published, and when they first published on the subject.

Design

Bibliometric study.

Setting and participants

We conducted electronic searches in Ovid MEDLINE ALL for articles about climate change and human health published from 1860 to 31 December 2022 in 330 health journals. There were no limits by language or publication type. Results were independently screened by two raters for article eligibility.

Results

After screening there were 2932 eligible articles published across 253 of the 330 journals between 1947 and 2022; most (2795/2932; 95%) were published in English. A few journals published articles in the early 90s, but there has been a rapid increase since about 2006. We were unable to categorise the types of publication but estimate that fewer than half are research papers. While articles were published in journals in 39 countries, two-thirds (1929/2932; 66%) were published in a journal published in the UK or the USA. Almost a quarter (77/330; 23%) of the journals published no eligible articles, and almost three-quarters (241/330; 73%) published five articles or fewer. The publication of joint editorials in over 200 journals in 2021 and 2022 boosted the number of journals publishing something on climate change and health. A third of the (112/330; 34%) journals in our sample published at least one of the joint editorials, and almost a third of those (32/112; 29%) were publishing on climate change and health for the first time.

Conclusions

Health journals are rapidly increasing the amount they publish on climate change and health, but despite climate change being the major threat to global health many journals had until recently published little or nothing. A joint editorial published in multiple journals increased coverage, and for many journals it was the first thing they published on climate change and health.

Keywords: Public Health, Review

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

The World Health Organisation has declared climate change to be the major threat to global health.

Previous studies have shown that articles on climate change and health began to appear in the early 1990s and then began to increase rapidly from around 2006.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

This study provides the first information on journals rather than simply articles and shows that many health journals had published little or nothing on climate change and health until recently. Some have still not published anything.

A few journals have published most of the articles.

For many journals the first article they published on climate change and health was an editorial published simultaneously in more than 200 journals.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

A next study might be to explore why many health journals have published so little on climate change and health and how they might be supported to publish more.

A preliminary investigation has shown that many journals would be interested to publish more, and a consortium of journals and publishers may be established to continue the publishing of the joint editorial each year. The consortium might also provide material for journals with limited resources and contacts and publish editorials on other topics threatening the world—for example, nuclear war.

Introduction

‘Climate change is the biggest global health threat of the 21st century’, concluded the Lancet Commission on Climate Change in 2009.1 Harm arises from heatwaves, storms, fires, floods, shortages of water, food, and shelter, changing patterns of disease, forced migration, and conflict.1 Yet if the world were to make the changes necessary to respond to climate change—for example, ending the use of fossil fuels, shifting diets to being largely plant-based and encouraging active transport, then the change could also be ‘the greatest opportunity for global health’.2

A series of reports by the Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change, the latest in 2022, show that the global temperature and emissions continue to rise, and the global response is inadequate.3 Health systems, like all other human activities, emit greenhouse gases, and if health systems were a country they would be the fifth biggest emitter.4 Most health systems have rising emissions of greenhouse gases.3 The NHS in England is responsible for between 4% and 5% of UK global emissions and is committed to achieving carbon net zero by 2040 on all that it controls directly and by all that it consumes by 2045.5 All other health systems will also have to achieve net zero by 2050 if the world is to respond adequately to climate change, and the changes will have to be radical, affecting all parts of the system including all medical specialties. Indeed, nobody knows exactly how health systems can achieve net zero, and much research will be needed. In addition, health systems must adapt to the climate changes that have already occurred and will continue to worsen for a while even if global emissions are cut. This includes both the impacts on patients and changing patterns of diseases, and the direct threat of changing climates to the health system.

The seriousness of the threat to health and the necessity for health systems and medical practice to change mean that climate change should receive extensive coverage in health journals. Health professionals need to be aware of all aspects of climate change and health because they will need to change as individuals and professionals. In addition, health systems and the organisations of health professionals will have to change. There will also have to be political changes and informed health professionals can be trusted advocates for change. All health professionals receive or access different journals, and all journals, not just a few, should be covering climate change and health. Each medical specialty will need to find a route to net zero, and specialist journals will have an important role in helping their specialty find the route.

Climate change from rising carbon dioxide levels was predicted as long ago as the late 19th century. In 1988, the head of the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies told a US Senate Committee: ‘The greenhouse effect has been detected, and it is changing our climate now’.6 The first Earth Summit was held in Rio de Janeiro in 1992.

Health journals could have been covering climate change and health for many decades. The Lancet Countdown on Climate Change conducted a bibliometric study of climate change and health and showed a near exponential growth in the number of peer-reviewed articles between 1985 and 2022, with fewer than 100 in 2000 and over 3200 in 2021.3 There was a 22% increase between 2020 and 2021.3 A supporting study of reports between 2013 and 2020 showed that more than four-fifths of the articles (86%) covered the implications for health of climate change rather than mitigation or adaptation.7 The authors used supervised machine learning and other natural language processing methods without checking the relevance of the individual articles identified by the search, and did not conduct an analysis by journal.7 Authors of a study published in 2016 searched in PubMed and Science Direct for publications from 1990 to 2014 for articles that contained one climate term and one health term in either the title, abstract or as a Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) term.8 The authors found few articles until 2006 and then an exponential increase, but papers dealing with health and climate were about half that of climate related articles in other sectors.

Another group searched the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Climate Change and Human Health Literature Portal, which includes global peer-reviewed research and grey literature conducted in North America (USA, Mexico and Canada).9 10 The database was compiled by searching PubMed, Web of Science and Google Scholar for research on climate change and health published from 2012 to 2019. The group reviewed individual articles and identified 7082 original research articles published between 2012 and 2019 with an average annual increase of 23%.

These previous bibliometric studies dealt with articles not journals, and only one study reviewed individual articles to ensure that they did cover climate change and health—and that study covered only the years after 2012 and research conducted in North America.9 10 Terminology for this topic has changed over the years and simply mentioning climate change does not mean that the article is addressing the topic. We set out to find the extent of the coverage of climate change in health journals over time in a broad set of health journals, using a broad search strategy with two raters screening the eligibility of the search results. We were particularly interested to know when and which health journals first published on climate change and health and how many had not published anything on the subject.

We were prompted to do this by a programme developed by the UK Health Alliance on Climate Change to encourage over 200 health journals around the world to publish the same editorials on climate change and health before COP26 and COP27, the United Nations annual meetings on climate change, in 2021 and 2022.11 12 The aim of the editorials was to encourage more action by governments and to reach more health professionals with information on the importance for health of acting on climate change. Before conducting our study, we had the impression that many of the journals had published little or nothing on climate change until they published these editorials.

Methods

Data sources and searches

We conducted electronic searches in Ovid MEDLINE ALL for articles about climate change published from 1860 to 31 December 2022.

Search: identification of journals

To identify a broad range of health journals to include in the search and to avoid retrieving articles in journals that focus on environmental health rather than climate change, we took three purposive journal samples and pooled the results. We identified the top 50 most highly cited clinical medicine journals based on impact factor from Clarivate’s Journal Citation Reports Database (JCR 2021); all journals listed in the JCR 2021 category of ‘Medicine, General & Internal’; and all journals that published the joint editorial coordinated by UKHACC, titled ‘Call for emergency action to limit global temperature increases, restore biodiversity, and protect health’ in 2021. After pooling the three samples, we removed duplicated journals and excluded journals that were not indexed in MEDLINE in January 2023.

To ensure a comprehensive list of journals meeting inclusion criteria, each journal was individually reviewed in the NLM Journals Database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nlmcatalog/journals/). Each included journal was reviewed for title changes since being indexed in MEDLINE. When title changes were identified, each previous and current journal title was reviewed to see whether it was indexed in MEDLINE. Published journals that were not labelled ‘Currently indexed by MEDLINE’ were excluded. For currently published titles indexed in MEDLINE, all journal titles for the same publication were included in the search to ensure maximum coverage of each journal if they were or had been indexed in MEDLINE. To be considered the same publication, volume numbering needed to continue across the title changes (eg, British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Edition) ceased with volume 296, number 6639 and BMJ (Clinical Research Edition) began with volume 297, number 6640).

Search: identification of articles on climate change and human health

MeSHs have not been available for the topic of climate change until 2010 and an array of terms have been used to describe the topic. We created a list of keywords based on those used in previous studies13–18 and supplemented this with additional keywords we thought should also be included following discussions as a team and experimenting with different keywords. We tested the initial search strategy on a single journal (The BMJ) and the research team reviewed the results to help decide whether the search should be more or less specific.

We found the inclusion of keywords for extreme weather conditions led to the inclusion of some ineligible articles but their exclusion from the search would lead to the exclusion of some relevant articles. Based on the pilot results and to estimate the magnitude of the problem in the full set of articles from all journals we decided to conduct two separate literature searches: (1) the ‘main search’ with the extreme weather-related terms excluded (see online supplemental appendix 1, line 409) and (2) the ‘extreme weather conditions search’ with additional weather-related terms that were not included in the main search (see online supplemental appendix 1, line 410).

bmjgh-2023-014498supp001.pdf (327.9KB, pdf)

Data extraction and synthesis

The main literature search was conducted in Ovid MEDLINE ALL on 26 January 2023 and updated on 31 March 2023. Results were exported to Covidence systematic review software (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Available at www.covidence.org) and Microsoft Excel. For every article identified by the main search, two independent raters screened articles for eligibility (using the inclusion and exclusion criteria in online supplemental appendix 2) based on article title and abstract only. For four non-English articles where no title or abstract were included from the export from MEDLINE, raters used the full text article link available in Covidence to access the full text of the article to assess the article title and or abstract for eligibility. All conflicting ratings were resolved independently by a third rater on Covidence. Ineligible articles were then removed from the Excel file which was exported from the search results in MEDLINE. For the ‘extreme weather conditions’ search, the search was conducted on 28 January 2023. We took a random sample of 5% articles from the search results and screened them for eligibility in the same way as for the main search.

Exclusion and inclusion criteria

For the search, all articles in the included journals available in MEDLINE and published 1860–2022 were eligible; there were no limits by language or publication type. Online supplemental appendix 2 gives details of the inclusion/exclusion criteria applied by raters.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the article language, year of publication, journal name and journal country of publication.

Patient and public involvement

BR, who completed a placement at the UK Health Alliance on Climate Change in autumn 2022 as part of the NHS Graduate Management Training Scheme, is our public representative and has been involved from the start of the study and at every stage of the study and in the writing of the manuscript.

Results

Sample

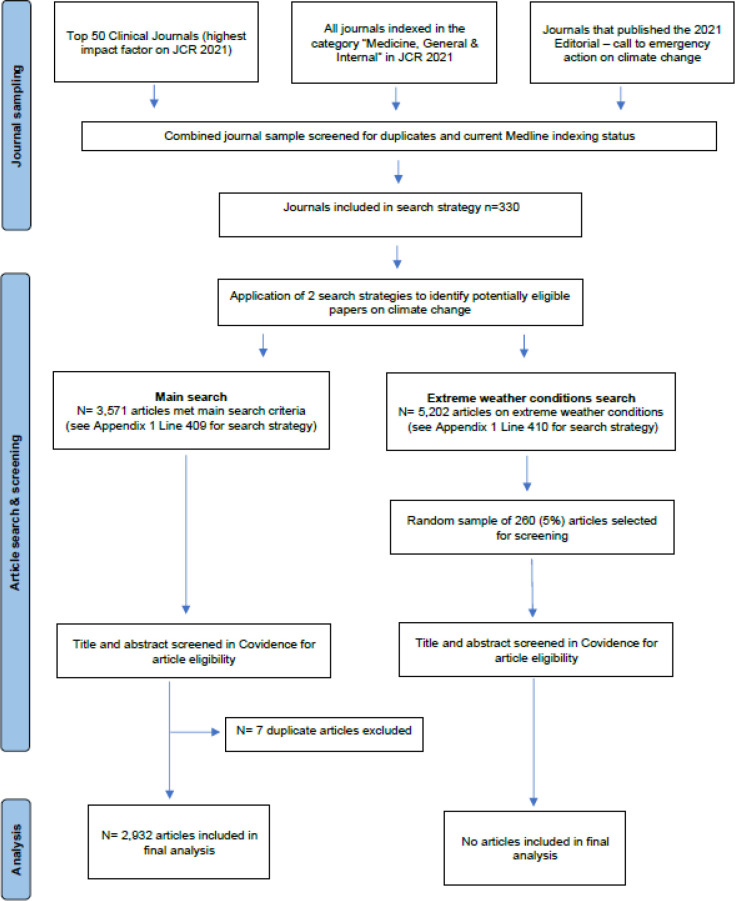

We included a sample of 330 journals from across the three sources (figure 1). The main search strategy identified a total of 3571 articles published. Five duplicates were removed after identification in Covidence and two during data analysis. After screening by raters 2932 (82%) of the remaining 3564 articles were considered eligible for inclusion.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of included articles.

The extreme weather conditions search identified 5202 articles. Screening of a random sample of 260 (5%) of these identified that only 6 (2%) were eligible for inclusion so we decided not to screen the results from the entire extreme weather conditions search and not to include any articles from this search in the final data analysis.

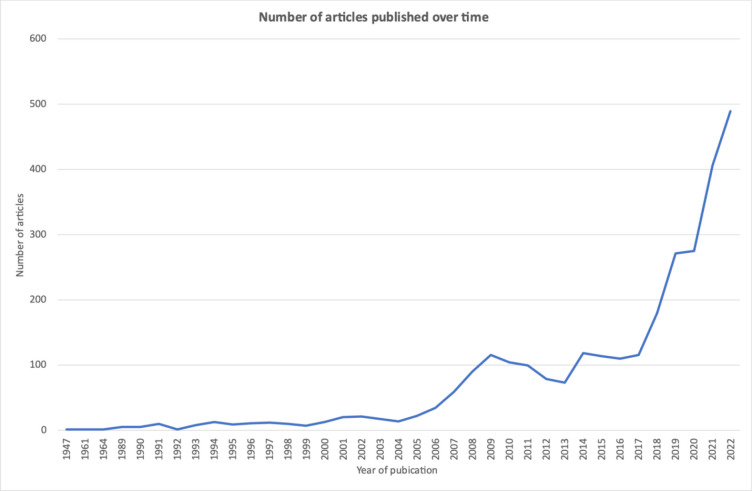

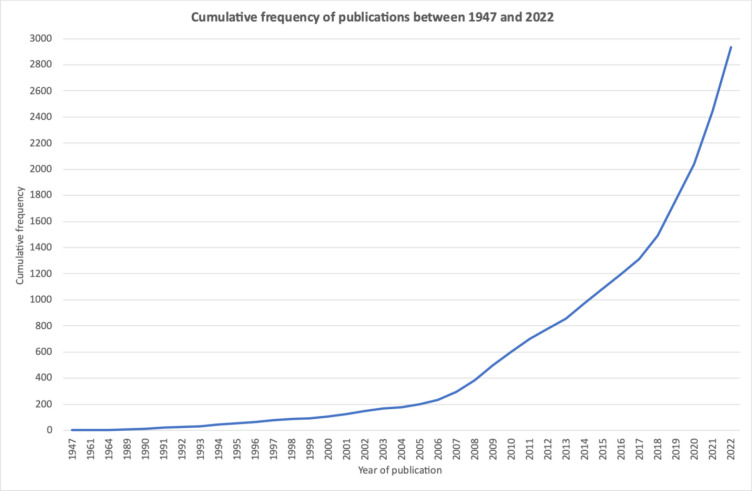

Distribution over time

Figure 2 shows the number of articles on climate change and health published each year between 1947, the earliest year of publication we identified, and 2022. We did not identify any articles published before 1947. Figure 3 shows the cumulative frequency of articles published between 1947 and 2022. There were occasional articles published in the 1990s, but the increase in the number of articles began in the early 2000s. Fewer than 100 articles had been published before 2000, slightly more than 600 by 2010, around 2000 by 2020 and almost 3000 by 2022.

Figure 2.

Number of articles published each year between 1947 and 2022 (n=2932).

Figure 3.

Cumulative frequency of articles published between 1947 and 2022 (n=2932).

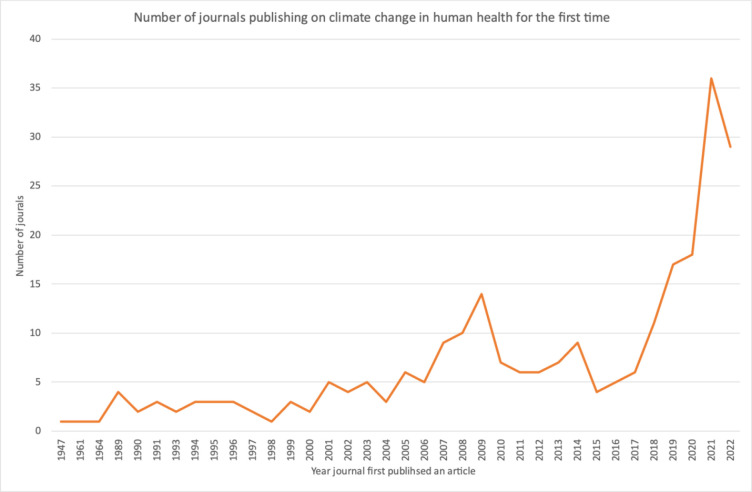

The figures for 2021 and 2022 were inflated by the publication of the two joint editorials11 12 across multiple journals. A total of 43 journals in our sample published the first editorial, 92 the second and 23 both. Figure 4 shows the number of journals publishing articles on climate change for the first time; there was a big increase between 2017 and 2022.

Figure 4.

Number of journals publishing an article on climate change in human health for the first time (n=253 journals).

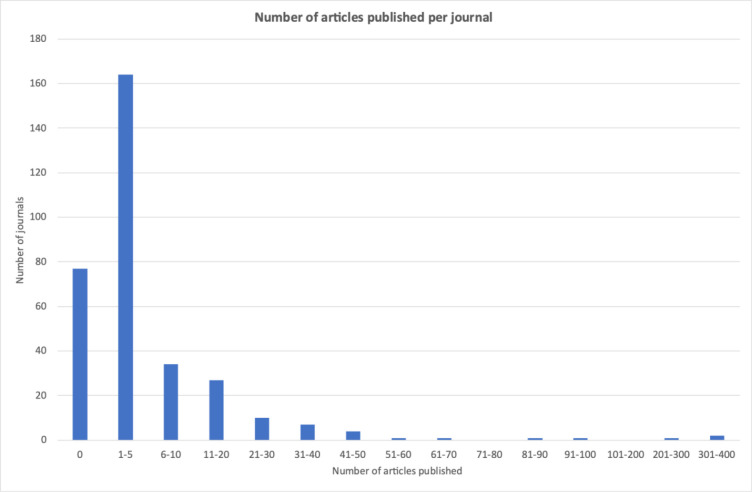

Distribution across journals

The 2932 eligible articles were published in 253 of the 330 included journals between 1947 and 2022. While the articles were published in journals in 39 countries, two-thirds (1929; 66%) of the articles were published in a journal published in the UK or the USA (online supplemental table 1). Figure 5 shows the distribution of articles across these 330 journals. Almost a quarter (77/330; 23%) of the journals published no articles on climate change and health, and almost three quarters (241/330; 73%) published five or fewer articles. Nine of the top 48 most highly cited clinical medicine journals (based on JCR 2021 and indexed in MEDLINE) published no articles; 58 of the 77 journals that published no articles were indexed in the JCR 2021 category of ‘Medicine, General & Internal’.

Figure 5.

Distribution of articles across the 330 sampled journals between 1947 and 2022 (n=2932).

The 10 journals publishing the most articles were The BMJ (343), Lancet Planetary Health (324), the Lancet (262), Global Health Action (92), the Medical Journal of Australia (82), mBio (67), Bulletin of the World Health Organization (55), BMJ Open (49), JAMA (44) and CMAJ (42). These 10 journals published 1360 (46%) of the 2932 articles.

Online supplemental table 2 shows the 59 journals publishing at least 10 articles between 1947 and 2022. Online supplemental figure 1 shows the number of articles published each year over time for the 10 journals publishing the most content between 1947 and 2022 (1360 articles). Since 2018 the specialist journal Lancet Planetary Health has published the most per year and in 2021–2022 it published 153 (17%) of all the 895 articles published; The BMJ published 98 (11%) and the Lancet 37 (4%).

Online supplemental figure 2 shows the number of journals that published at least one article on climate change in human health between 1947 and 2022. In 2000 fewer than 10 journals had published at least one article during the year; in 2010 it was slightly fewer than 40, in 2020 it was almost 100 and in 2022 it was 161 journals.

Article characteristics

Language of publication

The 2932 articles were published in 10 languages (English 2795, Spanish 41, Norwegian 41, French 31, German 22, Portuguese 19, Russian 6, Hungarian 5, Icelandic 3 and Chinese 1). 2795/2932 (95%) of the articles were published in English.

Article type

The publication type variable gave 134 different article types and we were not able to distinguish research from editorial and news type content without access to the full text of all articles. However, 1345/2932 (46%) articles had an abstract (abstracts were introduced to MEDLINE in the 1960s) so it is likely that fewer than half were research papers.

Impact of the first joint editorial

The aim of the joint editorials published in multiple journals is to push governments to be more active in acting on climate change and to reach more health professionals with information on the importance of acting on climate change for the benefit of health. The first joint editorial11 was published in September 2021 and the second12 in October 2022, and these boosted the number of articles published on the topic and the number of journals publishing on the topic in those years. If we exclude the publications of both these joint editorials there were 2796 articles published across 224 journals; 106/330 (32%) journals would have published no articles on climate change between 1860 and 2022.

Of the 330 journals, 112 (34%) published at least one of the joint editorials and 32 (29%) of these 112 were publishing on the topic for the first time. 29 (26%) of the 112 publishing at least one of the editorials did not publish anything else on the topic between 1947 and 2022. Of the 23 journals that published both of the editorials, 5 (22%) did not publish anything else on the topic between 1947 and 2022.

A total of 43 (13%) of the 330 journals published the first joint editorial. While 30 (70%) of these 43 journals published at least one article on climate change after this first joint editorial, for 10/30 (33%) this was just the second joint editorial.

18 (42%) of the 43 journals that published the first joint editorial had not previously published any articles on climate change in human health; 8/18 (44%) journals went on to publish at least one more article on the topic but 6 of these 8 just published the second joint editorial.

Discussion

Main findings

Our study confirms that there were occasional articles published on climate change and human health in the 1990s, but the increase in the number of articles began in the early 2000s.

Our study looked at journals as well as articles, and the main finding that our study adds to previous studies is that despite climate change being recognised as the major threat to global health, roughly a quarter of health journals (77/330; 23%) had by 2022 published nothing on the topic and almost three quarters (241/330; 73%) had published five or fewer articles. If the joint editorials published in multiple journals are excluded from the analysis then almost a third (106/330; 32%) of the journals would have published no articles on climate change between 1860 and 2022.

Three journals (The BMJ, Lancet Planetary Health and Lancet), all based in Britain, published almost a third of the articles (32%), and 10 journals, all in English, published almost half (46%). The two leading general journals based in Britain (Lancet and The BMJ) published 605 (21%) articles between 1860 and 2022, while the two leading general journals based in the USA (NEJM and JAMA) published 83 (3%).

Another new finding is that the joint editorials published in multiple journals in 2021 and 2022 were often the first article on climate change and health that the journals published: 112 of the 330 journals published at least one of the joint editorials and 32 (29%) were publishing on the topic for the first time.

Publishing the joint editorial as their first article on climate change has so far had little impact on encouraging the journals to publish more: of the 18 journals that published the first joint editorial as their first article on climate change, fewer than half (8, 44%) published at least one more article on the topic and six of these eight just published the second joint editorial.

Our results in comparison to other studies

Studies that have examined articles published on climate change and health have shown that articles first appeared in the early 1990s and then rapidly increased from the early 2000s.3 7 8 10 13 15 16 18 One study found, however, that papers concerned with climate change are published at about two times the rate in other sectors, when compared with health.8

The only study that gives information on journals is that by Sangam and Savitha, which looked at all articles on climate change in Web of Science between 2001 and 2016.15 The study includes data on the 20 journals publishing the most publications: Science is at the top (1523 publications). None of the 20 were health journals.

Other studies found that most articles on climate change and health came from high-income countries. We did not look at the country of origin of the articles, but we did find that most articles were published in journals from high income countries. Verner et al found that about two-thirds of all published studies were carried out in Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development countries, predominantly in Europe and North America.8 Berrang-Ford et al looked at 15 963 studies published between 2013 and 2019 and found the studies came mostly from high-income countries and China. There were few studies from low-income countries despite them suffering most from the health consequences of climate change.7 Bartlett et al studied research articles between 2012 and 2019, took a random sample of 348, and found that fewer than a third had first authors from the Global South.10 The Lancet Countdown looked at scientific studies and the majority of studies were located in, and led by, authors in WHO regions of Western Pacific and the Americas.3

We did not analyse the subject matter of the articles that we studied, but others have. Articles on the health impacts of climate change far outnumbered those on mitigation and adaptation, with little or nothing on decarbonising health systems.3 Berrang-Ford et al found that air quality and heat stress were the most frequently studied exposures, with major gaps in evidence on the impact of climate change on mental health, undernutrition, and maternal and child health.7 Bartlett et al found a lack of research on vulnerable populations, particularly the elderly and those in the Global South.10 Verner et al found that the effects of climate change on malnutrition and non-communicable diseases is understudied.8

Study strengths and limitations

A strength of our study is that we have looked at journals not just articles. We could not find any other studies that had looked at journals rather than articles, although Sangam and Savitha gave data on the top 20 journals covering all aspects of the science of climate not just health.15 We were able to examine the distribution of articles in journals and how many had published little or nothing on climate change and health.

We chose to use Ovid MEDLINE as the database to search in order to use complex adjacent word searching, which was not possible in PubMed. We may have missed some articles, but were able to design a more specific search using this technique. In addition to keyword searches, we also used MeSHs, however, the MeSH ‘Climate Change’ is relatively new and terminology has changed over time. Thus, we used combinations of specific MeSHs (eg, Climate Change, Global Warming) that were directly related to our topic and MeSHs that were more generic (eg, Public Health, Global Health) in combination with keyword searches.

Our use of search terms and adjacent word searching to try to capture all relevant papers will inevitably have resulted in the inclusion of some articles that may not be devoted to climate change’s impact on human health and may just have mentioned it. There is also an element of subjectivity when determining if an article is about climate change and human health or just mentioning it. Therefore, to improve the accuracy of the search results, two independent raters screened the articles’ title and abstract (where available) for article eligibility. Checking the full text of the included articles for relevance was not feasible as we were unable to access a large number of articles due to subscription and language barriers.

This independent screening of the MEDLINE search results is a strength in our approach, as other studies did not include this step, with the exception of Bartlett et al,10 and they studied only articles from North America published after 2012. However, even screening did not remove all ineligible articles. For example, we included all articles that had ‘climate change’ in the title but closer inspection of the earliest article, ‘Dangers of climate change’, published in German in Schweizerische Medizinische Wochenschrift in 194719 showed that it was about high altitude acclimatisation. A further two articles were published before 1989 (both in the 1960s) and were published in Spanish20 and French21 with no abstract. These articles may also not have been on the topic of climate change as they were published before the adoption of the use of the term climate change as we use it today. We expect that these errors will only have impacted the very early publications, but for reasons of consistency have not excluded them from the analysis as we did not apply full text screening across the whole sample.

Extreme weather events—heatwaves, floods, wildfires and extreme storms—have become more common with climate change, but existed before climate change and are not always linked to climate change. We reviewed a sample of articles on extreme weather events and found that only 2% mentioned these events being linked to climate change. Other search strategies might lead to these articles being included.

Our study includes the intervention of a group organising a joint editorial on climate change and health, which was published in multiple journals in 2021 and 2022. We were able to examine whether journals that published the first editorial, not having published before on climate change and health, were prompted to publish more articles on climate change and health.

We must be cautious in generalising to all health journals from our study. It was difficult to identify a representative list of health journals to include and our sampling will inevitably have influenced the results. We did include the most highly cited clinical journals and the top journals in general and internal medicine, which means that we have a bias towards bigger journals and medical as opposed to health journals. These journals are better resourced than most health journals, which makes it likely that we probably underestimated the number of health journals that have never mentioned climate change.

We may also have excluded some relevant articles. For example, by including only journals that are currently indexed in MEDLINE, we excluded many journals that published the joint editorials on climate change.11 12 However, we needed to do the article searches electronically as hand searching of the entire back archive of 330 journals was not feasible. Not all articles in a journal are always indexed in MEDLINE even if the journal itself is indexed. Some journals are indexed with multiple titles in MEDLINE and there is no systematic way of identifying these, so some journal names may have been omitted.

We excluded all the results from our extreme weather-related search, as our assessment of a random sample of 5% of these articles indicated that only 2% were potentially eligible for inclusion. However, we know that we missed a very small proportion of articles by excluding these results.

A limitation of our study is that we have not been able to examine the types of articles published, so our study does not differentiate between research articles and editorials, comments, news, letters and other types of articles. We know that only 46% of the articles had abstracts, which suggests that fewer than half of the articles were research studies. We know too that funding for research on climate change and health has been slow to become available,22 meaning that early articles—those before 2010—were likely to be editorials and comments rather than research. This may also explain why particular journals have published more—for instance, both the Lancet and The BMJ publish news.

Nor do we know the themes of the articles, but we know from the Lancet Countdown3 that the majority of articles published have been about the impact of climate change on health, far fewer on mitigating the effects of climate change, and fewer still on adapting to the changes that have already happened. Almost no articles so far have been on decarbonising health systems.

Another limitation of the study may have been unconscious bias as several of the authors were linked with the BMJ and the UK Health Alliance on Climate Change (see the Competing interest section).

Study implications

Why have most health journals published little or nothing on climate change and health?

Despite climate change being predicted in the 19th century, detectable effects occurring by the 80s, and the first Earth Summit being held in 1992, few articles on climate change and health appeared in health journals until the 2000s. Indeed, despite climate change being identified as the major threat to global health, by 2022 about a quarter of health journals in our sample had published nothing on climate change and health and almost three quarters had published five or fewer articles.

Why have health journals been so slow? There are almost certainly multiple reasons.

One answer might be that almost everybody has been slow. Although the serious threat of climate change has long been identified, emissions of greenhouse gases are still rising.3 The annual UN meeting on climate change, COP, featured health in the main agenda for the first time only in 2023. Of course, the policymakers may have been slow because health scientists have been slow.

Another reason may be that journals found the subject of climate change ‘too political’.23 Although scientists have been clear since the 90s that climate change is damaging health, many politicians denied the existence of climate change, that it is caused by human activity, and that it matters. Some still do. This may have made editors of health journals nervous about covering the subject. That journals based in the USA, where climate change has been a party political issue, have been slower than journals based in Britain, where there has been consensus on the importance of climate change, offers support for this possible reason.

Although general, public and global health, and epidemiology journals could feel comfortable covering climate change and health, specialist journals may have worried that the topic was not relevant to their readers. The health community has now recognised that health systems have to decarbonise, which means that every specialty will have to explore how it can do so, making the subject directly relevant to all parts of healthcare.

More than half of the articles we identified are not research articles but editorials, news, letters, comments and educational articles. Many health journals publish little but research articles, and, as we and others have shown, there has been little research on climate change and health until recently.

One important reason for the slow and limited coverage of climate change and health is that many journals commission few articles. They wait for material, usually research papers, to be submitted. A related reason is that even if they do commission material, many health editors would not know whom to ask to write on the subject: there have been, and still are, few authorities on climate change and health.

Increasing coverage of climate change and health in health journals?

As health journals are a major source of information to health professionals, we think it important that all health journals include material on all aspects of this subject. Specialist journals will need to cover the impact on their specialty and explore how the specialty can progress to net zero. Coverage of climate change and health is increasing in health journals and is likely to continue to increase because of growing global concern about the seriousness of the climate crisis, and because of the recognition of the need for decarbonising healthcare.

It seems that many journals are willing to publish further articles on climate change and health but lack the capacity to commission such articles. This finding supports a proposal to establish a consortium that would lead the publishing of joint editorials on the subject, perhaps more than once a year, and commission and share articles with the many journals that lack the capacity to commission articles themselves. In this way, material on climate change and health could reach many more health professionals.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Twitter: @muhiajoy, @BenRossington1

Contributors: SS, JM, MLR, BR, RS designed the study and developed the search strategy. MLR wrote the search strategy and conducted the literature searches. SS, MLR and JM extracted data. RS, BR, JM, FW, AP, MLR screened the articles for eligibility. SS analysed the data with JM. SS is the study guarantor. All authors had direct access to the data, interpreted the findings and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/disclosure-of-interest/ and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; SS is a full time employee of BMJ Publishing Group which published many of the articles included in this study. MLR is working on a self-funded PhD in conjunction with BMJ Publishing Group and Maastricht University. AP is working as a policy officer with the UK Health Alliance on Climate Change (UKHACC). RS was the editor of The BMJ from 1991 to 2004, an assistant editor before that from 1979, and is now chair of the UK Health Alliance on Climate Change, which organised and funded the joint editorial that has appeared in multiple journals. RS has long been concerned about environmental issues. FW recently completed a year as a sustainability fellowship at The BMJ, and she remains a freelance clinical editor at The BMJ. BR worked at UKHACC for 2 months in autumn 2022 and supported work on the second joint editorial. JM helped with the second joint editorial.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository. The data that support the findings of this study are available on OSF:https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/GSFYQ

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Costello A, Abbas M, Allen A, et al. Managing the health effects of climate change. Lancet 2009;373:1693–733. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60935-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang H, Horton R. Tackling climate change: the greatest opportunity for global health. Lancet 2015;386:1798–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60931-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Romanello M, Di Napoli C, Drummond P, et al. The 2022 report of the lancet countdown on health and climate change: health at the mercy of fossil fuels. Lancet 2022;400:1619–54. 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01540-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Health Care Without Harm and Arup . Health care’s climate footprint: how the health sector contributes to the global climate crisis and opportunities for action. 2019. Available: https://noharm-global.org/sites/default/files/documents-files/5961/HealthCaresClimateFootprint_092319.pdf [Accessed 18 Oct 2023].

- 5.NHS England . Delivering a ‘net zero’ national health service. London: NHS England; 2019. Available: https://www.england.nhs.uk/greenernhs/wp-content/uploads/sites/51/2022/07/B1728-delivering-a-net-zero-nhs-july-2022.pdf [Accessed 18 Oct 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krajick K. James hansen’s climate warning, 30 years later. Columbia Climate School; 2018. Available: https://news.climate.columbia.edu/2018/06/26/james-hansens-climate-warning-30-years-later/ [Accessed 18 Oct 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berrang-Ford L, Sietsma AJ, Callaghan M, et al. Systematic mapping of global research on climate and health: a machine learning review. Lancet Planet Health 2021;5:e514–25. 10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00179-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verner G, Schütte S, Knop J, et al. Health in climate change research from 1990 to 2014: positive trend, but still underperforming. Glob Health Action 2016;9:30723. 10.3402/gha.v9.30723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harper SL, Cunsolo A, Babujee A, et al. Climate change and health in North America: literature review protocol. Syst Rev 2021;10:3. 10.1186/s13643-020-01543-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bartlett VL, Gupta R, Wallach J, et al. Published research on the human health implications of climate change from 2012-2019: a cross-sectional study. MedRxiv [Preprint] 2022. 10.1101/2022.10.01.22280596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Atwoli L, Baqui AH, Benfield T, et al. Call for emergency action to limit global temperature increases, restore biodiversity, and protect health. BMJ 2021;374:n1734. 10.1136/bmj.n1734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Atwoli L, Erhabor GE, Gbakima AA, et al. COP27 climate change conference: urgent action needed for Africa and the world. BMJ 2022;379:o2459. 10.1136/bmj.o2459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Einecker R, Kirby A. Climate change: a bibliometric study of adaptation, mitigation and resilience. Sustainability 2020;12:6935. 10.3390/su12176935 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fu HZ, Waltman L. A large-scale bibliometric analysis of global climate change research between 2001 and 2018. Clim Change 2022;170:36. 10.1007/s10584-022-03324-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sangam SL, Savitha KS. Climate change and global warming: a scientometric study. CJSIM 2019;13:199–212. 10.1080/09737766.2019.1598001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sweileh WM. Bibliometric analysis of peer-reviewed literature on climate change and human health with an emphasis on infectious diseases. Global Health 2020;16:44. 10.1186/s12992-020-00576-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sweileh WM. Bibliometric analysis of peer-reviewed literature on food security in the context of climate change from 1980 to 2019. Agric Food Secur 2020;9:9. 10.1186/s40066-020-00266-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li F, Zhou H, Huang D-S, et al. Global research output and theme trends on climate change and infectious diseases: a retrospective bibliometric and co-word biclustering investigation of papers indexed in PubMed (1999–2018). Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:5228. 10.3390/ijerph17145228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neergaard KV. Dangers of climate change [in German]. Schweiz Med Wochenschr 1947;77:1160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hollander JL. The effect of climate changes upon the evolution of rheumatoid arthritis [in Spanish]. Rev Med Chil 1964;92:180–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cuenot A. [Psychism and change of climate]. Presse Med 1961;69:35–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ebi KL, Semenza JC, Rocklöv J. Current medical research funding and frameworks are insufficient to address the health risks of global environmental change. Environ Health 2016;15:108. 10.1186/s12940-016-0183-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hai Z, Perlman RL. Extreme weather events and the politics of climate change attribution. Sci Adv 2022;8:eabo2190. 10.1126/sciadv.abo2190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjgh-2023-014498supp001.pdf (327.9KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository. The data that support the findings of this study are available on OSF:https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/GSFYQ