Abstract

Host-microbe interactions have been linked to health and disease states through the use of microbial taxonomic profiling, mostly via 16S rRNA gene sequencing. However, many mechanistic insights remain elusive, in part because studying the genomes of microbes associated with mammalian tissue is difficult due to the high ratio of host to microbial DNA in such samples. Here, we describe a microbial-enrichment methodology (MEM) that enables high-throughput characterization of microbial metagenomes from human intestinal biopsies by reducing host DNA more than 1,000-fold with minimal microbial community changes (~90% of taxa had no significant differences between MEM-treated and untreated control groups). Shotgun sequencing of MEM-treated human intestinal biopsies enabled characterization of both high- and low-abundance microbial taxa, pathways, and genes longitudinally along the gastrointestinal tract. We report the first construction of metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) directly from human intestinal biopsies for bacteria and archaea at relative abundances as low as 1%. Analysis of MAGs reveals distinct subpopulation structures between the small and large intestine for some taxa. MEM opens a path for the microbiome field to acquire deeper insights into host-microbe interactions by enabling in-depth characterization of host-tissue-associated microbial communities.

Introduction

The mucosal microbiota of the intestine has been implicated in a wide range of health conditions1 including cancer,2,3 inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)4-7, and celiac disease.8,9 Most microbiome studies use fecal samples to infer the gastrointestinal (GI) microbiota due to its ease of access, despite microbes in feces and intestinal biopsies having distinct ecological niches.10-13

The majority of microbiome studies sequence 16S rRNA gene amplicons,14 enabling detailed descriptions of taxonomic profiles of microbial communities. More recently, shotgun metagenomics—sequencing of the entire DNA content of a sample—has become more common in human microbial ecology due to its ability to provide in-depth, genome-resolved characterizations of microbial populations.12,13,15,16 Further, by resolving subpopulation structures within a single taxon, shotgun metagenomics can enable additional insights, such as how physiological host gradients can induce evolutionary pressures on the microbiome.17,18 Genome-resolved characterization is also needed to study which microbial genes are under selection pressure under different host environments.

The molecular details of how tissue-associated microbes interact with the host environment remains poorly understood because the field lacks appropriate tools to go beyond taxonomic profiling and investigate microbial pathways and genes directly from intestinal biopsies. Two common methods of full-genome characterization include culturing microbial isolates or reconstructing metagenome-assembled genomes (MAG) directly from mixed microbial samples. Culture-dependent methods have their role; however, culture-independent methods are attractive for characterizing microbes from their native context, as well as those cannot be easily isolated. MAGs are created via a computational approach15 in which sequencing reads are assembled into continuous sequences and then grouped into separate bins to reconstruct complete genomes without culturing.19

Shotgun metagenomic sequencing analyses of complex host-associated microbiomes have been challenged by the high ratio of host to microbial nucleic acids20. In humans, 85-95% of reads in a saliva sample21 are host and more than 99.99% of reads in an intestinal biopsy are host. These enormous ratios of host to microbial DNA (1:10,000 in a human intestinal biopsy) are particularly challenging for shotgun metagenomic sequencing studies because most reads align to the host genome. Such tissue samples sequenced directly using current protocols and sequencing depths do not produce sufficient microbial reads to construct MAGs.

To prevent the majority of shotgun-sequencing reads assigning to host, a wide variety of host-removal (i.e. host-depletion) methods have been developed.21-26 Published and commercial protocols have enabled both long-read sequencing and bacterial MAG construction from mammalian derived liquid samples. Although some protocols have been validated for use on solid tissue sample types, and others may have potential for success in these samples, none have been shown to be sufficiently effective to enable bacterial MAG construction from solid mammalian tissues. Additionally, many host-depletion methods are not feasible to perform in the clinic due to extensive processing times and complex protocols.

Here, we developed and optimized a microbial-enrichment method (MEM) to remove host nucleic acids from complex samples while not substantially perturbing the microbial community composition. We demonstrate the performance of MEM in laboratory and clinical settings, and with a range of sample types, including saliva, feces, intestinal scrapings, and intestinal biopsies. We also demonstrate the ability of MEM followed by shotgun metagenomic sequencing to detect both high- and low-abundance microbial taxa, pathways, and genes from human intestinal biopsies along the GI tract. We further demonstrate the use of MEM to enable MAG construction directly from human intestinal biopsies to identify and differentiate subpopulations and subpopulation variants.

Results

Microbial-Enrichment Methodology (MEM) development

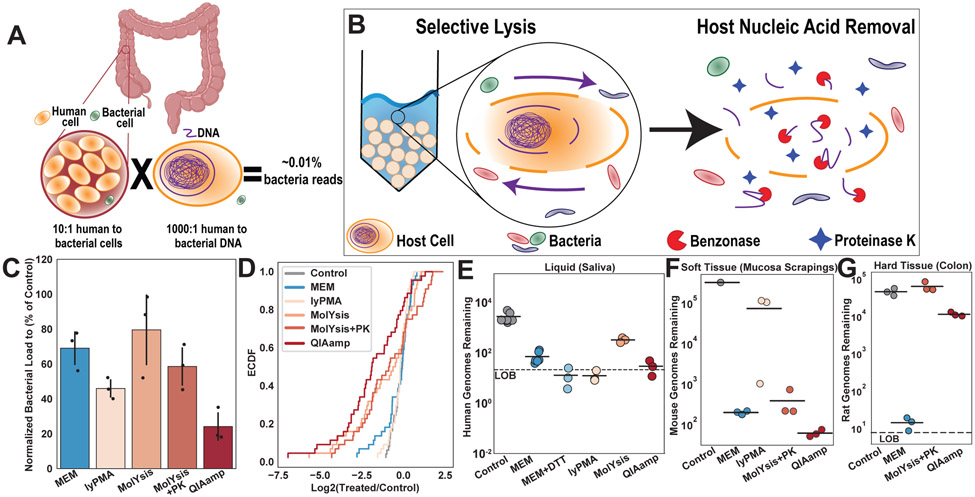

In developing our host-depletion methodology, we had three critical requirements: (1) it must remove host DNA at least 1000-fold (Fig 1A), (2) it must induce minimal microbial compositional perturbations, and (3) it must be compatible with a clinical setting (i.e. require few resources and hands-on time). To fulfill these requirements, we developed a microbial-enrichment methodology (MEM) that incorporates a selective-lysis protocol utilizing mechanical stress (bead-beating) by leveraging the size differences between host and bacterial cells (Fig 1B). Beads typically used for microbial lysis are 0.1-0.5 mm but we chose larger beads (1.4 mm) to create high mechanical shear stress on the larger host cells while leaving small bacterial cells intact.27 Next, Benzonase is added to degrade accessible extracellular nucleic acids (NA), including NA from dead lysed microbes. Proteinase K further lyses host cells and degrades host histones for DNA release. We optimized many aspects of MEM, including enzymatic NA removal, bead-beating, and incubation time, to keep the entire protocol time under 20 min, with gentle processing conditions to prevent microbe lysis. (Methods; Fig S1).

Figure 1: Comparison of the performance of the microbial-enrichment methodology (MEM) with published host-depletion methods.

A) Estimated percentage of bacterial reads obtained when human intestinal biopsies are sequenced without processing. B) Schematic demonstrating the two-step selective-lysis and nucleic-acid removal techniques used in MEM. C) Bacterial loads from mouse stool samples treated with five different host-depletion methods. Loads are normalized to the control (no host depletion) stool samples (N=3; error bars are 95% CI centered on the mean). D) Empirical cumulative distribution function (ECDF) of 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing results from mouse stool samples normalized to the control stool samples (N = 3). Curves shifted to the left of the control indicate a greater percentage of taxa with lower abundance than the control samples following host depletion. E-G) Remaining host DNA was quantified through ddPCR of a single-copy host specific primer (see Methods). Reported genomes remaining refers to the abundance of this single-copy gene present in 1 μL of elution. E) Remaining human genomes in fresh human saliva were quantified after treatment with each host-depletion method and in untreated controls (N=3 biological replicates for lyPMA, MolYsis, and QIAamp. N=4 biological replicates for Control. N=4 biological replicates for MEM. and N=3 technical replicates for MEM+DTT). F) Host-depletion methods were tested on mouse intestinal mucosal scrapings as a representative of soft tissue and remaining mouse genomes were quantified (n=3 for host depletion methods and n=1 for control from one mouse). G) Host-depletion methods were tested on rat colonic sections as a representative hard tissue (including connective tissue, muscle, and mucosa) and remaining rat genomes were quantified (N=3; biologic replicates from one rat).

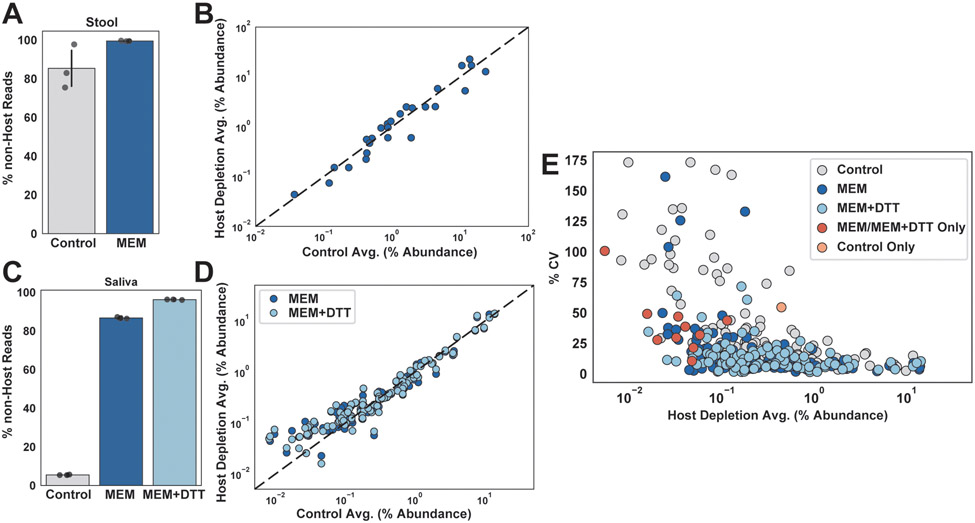

Figure 2: Microbial enrichment of stool and saliva after host-depletion by MEM as confirmed by shotgun sequencing.

(A) The percentages of non-host reads in control and MEM-treated mouse stool samples were calculated bioinformatically through alignment to a mouse reference genome (N=3; error bars are 95% CI centered on the mean). (B) Species-level taxon relative abundances were plotted for control and MEM-treated mouse stool and overlaid on a dashed line showing 1:1 correlation. (C) Shotgun sequencing was performed on control and MEM-treated fresh human saliva. The percentages of non-host reads were calculated bioinformatically through alignment to a human reference genome. One saliva sample was evenly split nine ways for this comparison (N=3). (D) Species-level taxon relative abundances were plotted for control and MEM-treated fresh human saliva and overlaid on a dashed line showing 1:1 correlation. An additional DTT pre-treatment was performed prior to MEM treatment for a subset of MEM-treated samples (MEM+DTT) (N=3). E) Coefficient of variation was plotted against relative species abundance and colored based on treatment types the taxa were detected in. Each point represents a species; grey, dark-blue and light-blue points indicate taxa that were present in all three treatments (control, MEM, and MEM+DTT). MEM/MEM+DTT only (red points) indicate the 10 taxa found only in the MEM-treated samples. Control only (orange point) indicates the single taxon that was found only in the control samples, which was identified as Haemophilus.

To compare host-depletion by MEM with existing methods, we selected three published methods that utilize different cell-lysis approaches: MolYsis, QIAamp, and lyPMA. All host-depletion methods are composed of two main steps: selective lysis followed by NA removal. QIAamp lyses cells lacking a cell wall through a weak detergent, saponin.28 MolYsis selectively lysis the more fragile mammalian cells through exposure to a weak concentration of guanidinium.29 lyPMA lyses mammalian cells through osmotic lysis21 and uses photochemistry to render DNA accessible to propidium monoazide (PMA) non-amplifiable.

MEM minimizes loss of bacteria during sample processing

To quantify how MEM affects microbial community composition and relative abundances of individual taxa, we first used frozen mouse fecal samples. For validation, we chose fecal samples instead of a contrived community to characterize microbial impacts on a wider range of unique taxa and on a continuum of abundances. Additionally, contrived communities still require an extracted control due to variation in extraction kit efficiency.30,31 Mouse fecal samples do not typically require host-depletion because they have low levels of host contamination (more than 90% of the DNA biomass originates from non-host cells). Thus, the high biomass of microbial cells makes feces ideal for characterizing the impact of different host-depletion methods on the microbial community composition.

Although we were unable to extract all DNA molecules in the samples, all samples were processed with the same extraction kit following host depletion to standardize extraction kit/lysis efficiency. On homogenized stool samples, we observed similar losses in microbial recovery across all five host depletion protocols compared to a control, untreated sample (Fig 1C). MEM induced on average 31% (SD: 11%) bacterial loss, which falls within the expected fraction of 10-50% dead microbial cells in stool.32 To characterize how MEM and the other host-depletion methods affect the microbiome at a taxonomic level, we next performed quantitative 16S rRNA gene sequencing 33 on the mouse fecal samples (N=3). By comparing paired host-depleted and control samples, we found that lyPMA and QIAamp induced the largest total bacterial losses whereas MolYsis and QIAamp induced the least uniform bacterial losses, with some taxa dropping more than 100-fold (Fig 1C-D). Previous literature suggests QIAamp’s saponin concentration can be lowered to limit some of these bacterial losses.25 We confirmed that MEM induced minimal losses in the microbial community; more than 90% of genera showed no significant difference in relative abundance between MEM and control samples (paired t-test, two-sided, P=0.05). Additionally, all taxa that were consistently detected in the control samples were also detected in the MEM-treated samples, whereas MolYsis and QIAamp resulted in some taxa drop-out (Table S1). Because MEM selectively lyses host cells based on cell size, this approach appears to introduce lower bacteria bias compared with chemical lysis alternatives (MolYsis and QIAamp) where degree of lysis may differ based on bacterial cell wall/membrane structures (Fig S2).

To determine how effectively MEM and the other host-depletion methods removed host material, we next quantified the amount of host DNA remaining after each host-depletion method on three additional sample types: liquid, soft-tissue, and hard-tissue samples (Fig 1E-Ge, discussed in detail below), in which the host DNA made up as much as 99.9% of the total biomass. In saliva, all methodologies enabled some host removal. Following MEM treatment, over 40-fold depletion of host was achieved (Fig 1E). The addition of DTT pre-treatment, which was added due to the high mucin content of saliva, slightly increased host removal by MEM in some participants (Fig 1E, Fig S3). lyPMA appeared highly effective at host removal, but was difficult to use predictably as the stoichiometric nature of the method can result in large microbial losses when host levels are lower than expected (Fig S3). Additionally, MolYsis showed increased bacterial recovery, likely due to the additional mutanolysis step.22,26

We next examined host depletion on whole tissue samples, beginning with mouse intestinal scrapings that isolate the epithelial layer with mucosa-associated bacteria (Fig S4). Mucosal scraping samples were efficiently host-depleted by MEM and some of the published methods (Fig 1F). MEM, MolYsis, and QIAamp all showed around 1000-fold depletion of host with QIAamp showing slightly greater host-removal (MEM had an average 1,600-fold depletion [SD: 170]). lyPMA performed poorly on the soft tissue sample because this method relies on UV-activated crosslinking making it incompatible with opaque sample types.

We next tested host-depletion methods on hard-tissue samples using rat colonic sections because they are anatomically similar to a human intestinal biopsy. We excluded lyPMA from the hard-tissue experiment due to its poor performance on soft tissue (Fig 1F). MEM was the only method that worked on the solid-tissue sample type (Fig 1G). MEM treatment resulted in almost complete removal of the host DNA (3,600-fold removal; SD: 1,500), whereas MolYsis and QIAamp host DNA levels after treatment were similar to the control.

These experiments demonstrated that MEM is the first solid-tissue host-depletion method to remove host DNA more than 1,000-fold while introducing minimal losses in the relative abundances of the microbial fraction. In our experiments, more than 90% of genera showed no significant difference in relative abundance between MEM-treated and control samples based on 16S rRNA gene profiling.

Shotgun sequencing of MEM-treated saliva and stool

We next investigated the utility of MEM for shotgun metagenomics. Due to biomass limitations, accurate characterization of microbial communities through shotgun sequencing of control (not host-depleted) samples is not feasible on intestinal biopsies. Thus, we first used saliva and stool samples to investigate potential biases associated with MEM treatment within the microbial fraction. We first confirmed that MEM treatment enabled reliable reduction in host reads across mouse stool and human saliva samples (Fig 2A, 2C). DTT pre-treatment in saliva improved host removal roughly 10-fold (Fig 2C).

Next, we compared the results of shotgun sequencing between the control and MEM-treated samples. There was a high correlation between the relative abundances of bacterial taxa in control and MEM-treated samples for both stool and saliva (R2 = 0.93 for stool and R2 = 0.90 for both MEM and MEM+DTT in saliva; with R2 = 0.93 for taxa above 0.1% relative abundance). For stool and saliva, a high correlation between the relative abundance of species in control vs MEM-treated samples showed that MEM did not substantially alter microbiome composition (Fig 2B & 2D, Table S2-3). For saliva, the correlation was less pronounced for low-abundance taxa with enrichment of specific species in MEM-treated samples and was investigated more quantitatively by comparing the coefficient of variation (CV) across samples for low-abundance species (Fig 2E). MEM-treated saliva samples had lower CV (50% CV, 95% CI), indicating better replicability compared with untreated controls. Additionally, MEM improved quantification of low-abundance species (0.5-0.05% abundance), enabling detection of an additional 10 species that were undetected in the control. We further confirmed these taxa were not introduced during MEM processing (Fig S5). These shotgun-sequencing experiments with mouse fecal and human saliva samples demonstrated that MEM treatment introduced minimal microbial biases (more than 98% of microbial species experienced less than a 4-fold loss in relative abundance) while detecting additional microbial taxa at equivalent sequencing depths.

MEM feasibility on human intestinal mucosal biopsies

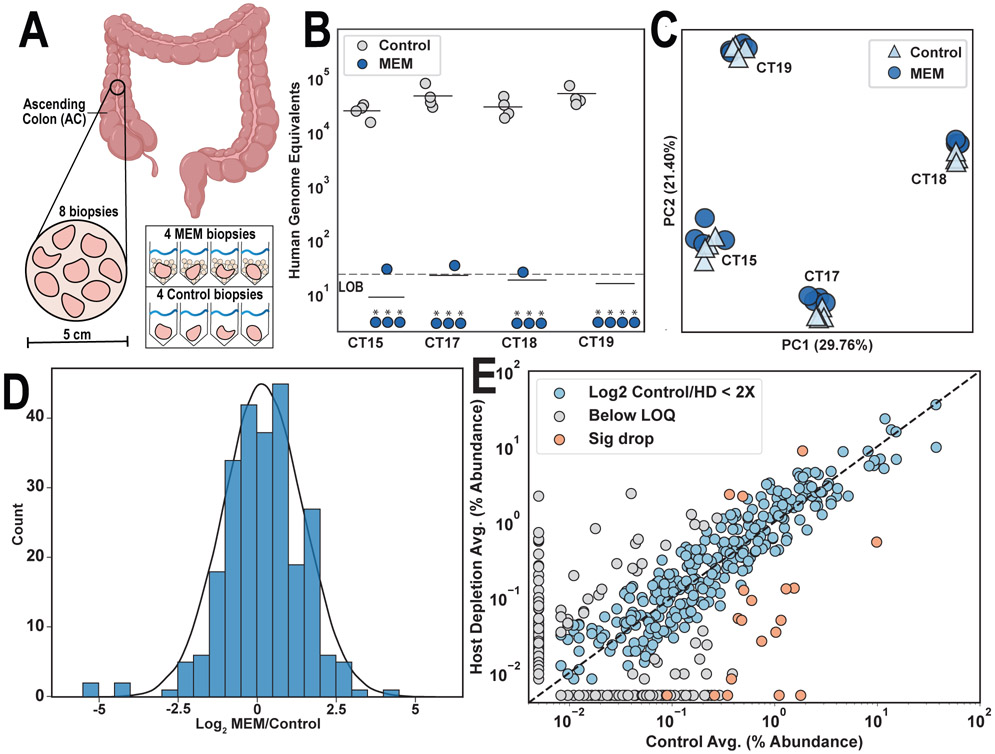

To determine how MEM performs on human intestinal biopsies, we recruited healthy participants undergoing routine colon cancer screenings via colonoscopy. From each of four participants, we obtained eight mucosal biopsies; four biopsies from each participant were assigned to the MEM-treatment group and four were untreated controls (Fig 3A). Due to concerns regarding contaminant DNA in samples with low bacterial loads,34-37 we also characterized the background bacterial signal associated with MEM and our processing methods through quantitative 16S rRNA gene sequencing of MEM processing blanks (see Methods and Tables S4-S5). MEM removed host DNA more than 2,000-fold across all 16 biopsies, with most biopsies having host levels comparable to a processing blank after MEM treatment. (Fig 3B).

Figure 3: Analysis of microbial enrichment in paired human intestinal biopsies processed with and without MEM.

A) Sampling graphic illustrates collection from four participants (CT15, CT17, CT18, and CT19) each with eight ascending colon biopsies. Four biopsies from each participant were MEM-treated and four were untreated controls. B) Host DNA was quantified for each biopsy using ddPCR of a single-copy host primer. Human genomes remaining refers to the abundance of this single-copy gene present in 1 μL of elution (* indicate measurement was below limit of blank [LoB]). C) Biopsies were characterized with 16S rRNA gene sequencing and principal component analysis (PCA) on microbial genus-level relative abundances were performed to visualize microbial population variation. D) Log2-fold differences in genus-level relative abundances of taxa between control and MEM-treated biopsies were plotted with a standard normal distribution overlaid in black. E) Genus-level relative abundance of taxa measured in control vs MEM-treated biopsies were plotted and overlaid on a dashed line showing 1:1 correlation. Highlighted in gray are taxa that were below the assay limit of quantification (LOQ). Highlighted in orange are taxa with greater than 4-fold changes between control and MEM biopsies.

To determine how MEM affects the human intestinal microbiome at a community level, we first performed quantitative 16S rRNA gene sequencing.33 Roughly 93% of genera remained in MEM-treated and control biopsies after computationally removing taxa found at higher absolute abundances in the blanks, giving us confidence most detected taxa were not background contaminants. To further confirm that MEM did not introduce additional contamination, we found strong agreement between taxon abundances in MEM and control biopsies (Table S6). Principal component analysis of sequencing results showed that any differences in microbial relative abundances introduced by MEM were less than the differences observed between participants (Fig 3C). Analysis of sequencing results revealed minimal changes in relative abundances of most taxa after MEM treatment, with roughly 88% of taxa having no significant differences in relative abundances from the controls (Mann Whitney U test, two-sided P=0.05). For taxa present at greater than 1% relative abundance, more than 95% of taxa had no significant differences between MEM and control samples. The log2-fold difference in taxa between control and MEM-treated samples approximated a normal distribution (Kolmogorov–Smirnov test against normal distribution, statistic=0.074 P=0.11) (Fig 3D). Furthermore, there was a linear correlation in relative taxon abundances between the control and MEM-treated samples (Fig 3E). MEM enables over 1,000-fold host removal while introducing minimal biases in microbial relative abundances when used in a clinical setting on human intestinal biopsies.

MEM enables study of microbial species, pathways, and genes

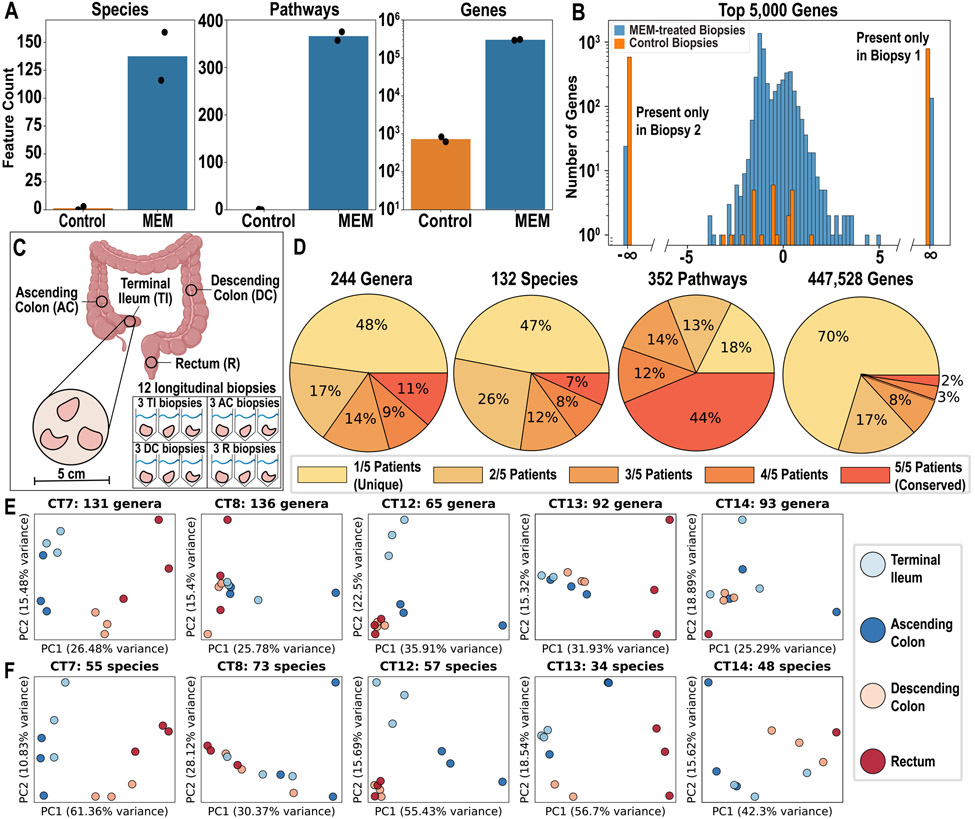

To investigate whether MEM enables detection and characterization of additional microbial species, pathways, and genes from human intestinal biopsies, we shotgun-sequenced paired control and MEM-treated biopsies from CT18 at a depth of above 100 million reads (N=2 for each condition) (Fig 3A). We observed roughly a 100-fold increase in the number of organisms, a 700-fold increase in the number of pathways, and over a 400-fold increase in the number of genes detected in MEM-treated samples compared with the control samples (Fig 4A). When comparing only completed pathways, defined as above 90% complete, no complete pathways were detected in either of the control biopsies. An average of 1.5 (± 1.5) species and 728 (± 107) genes were detected in the control biopsies, whereas an average of 137.5 (± 21.5) species and 300,641 ( ± 6,922) genes were detected in the MEM-treated biopsies. MEM treatment enabled shotgun-sequencing classification of microbes down to a relative abundance of 0.005%, whereas in control biopsies a minimum relative abundance of 10% was required to detect microbes at similar sequencing depths. MEM-treated biopsies could detect genes down to a relative abundance of 10−10, whereas in control biopsies genes could only be detected when present at a minimum relative abundance of 10−5. We further found that MEM treatment improved reproducibility of detecting the most abundant genes. We compared the relative abundance of the top 5,000 most abundant genes between two MEM-treated and two control biopsies (Fig 4B). In the control biopsies, a high percentage of the genes (98%) were detected in only one sample, whereas for the MEM-treated samples only 3% of the genes were detected in one biological replicate but not the other.

Figure 4: Shotgun sequencing of MEM-treated human intestinal biopsies.

A) Four biopsies from participant CT18 (two MEM-treated and two control) were shotgun-sequenced and the number of microbial species, pathways, and genes identified in each sample were plotted (N=2). B) For the top 5,000 abundant genes, the log2 fold-change in relative abundances between the two MEM-treated biopsies and the two control biopsies were plotted. C) Sampling graphic for collection of 12 biopsies from each of 5 participants (3 biopsies taken from 4 separate regions of the GI tract). Biopsies within one region were sampled within one field of view (5-cm diameter). D) All 60 biopsies were processed with MEM, followed by 16S rRNA gene sequencing (for genera) and shotgun sequencing (for species, pathways, and genes). The number of features for genera, species, pathways, and genes were grouped based on whether they were present in at least one biopsy sample from only one participant (1/5), two participants (2/5), three participants (3/5), four participants (4/5), or from all participants (5/5). Only genera and species above 0.1% abundance in at least one biopsy were considered for the analysis in panels D-F. E-F) PCA was performed on all 60 longitudinal samples grouped by participant (CT7, CT8, CT12, CT13, CT14). E) PCA on relative abundance of 16S rRNA gene sequencing genera assignments. F) PCA on relative abundance of shotgun-sequencing species assignments.

Next, we tested whether MEM would enable characterization of microbial variation (at the taxon-, pathway-, and gene-level) cross sectionally across individuals and longitudinally across the GI tract of a single individual. Five healthy participants undergoing colonoscopy were sampled in four regions across the GI tract: terminal ileum, ascending colon, descending colon, and rectum. From each location, three biopsies were obtained resulting in a total of 12 biopsies per participant (Fig 4C). All biopsies were processed with MEM and the microbial profiles were characterized via 16S rRNA gene sequencing and shotgun sequencing at an average read depth of 25 million, producing an average of 2 million non-host reads (Fig 4D-F, Fig ED1-2). About half (91 of 187) of the microbial species identified were unique to an individual (Fig 4D, Table S7). These unique species ranged in relative abundance from 10% to 0.01% (Fig S6). As was observed previously, pathways appeared more conserved across participants compared with taxonomy (genera and species),38,39.

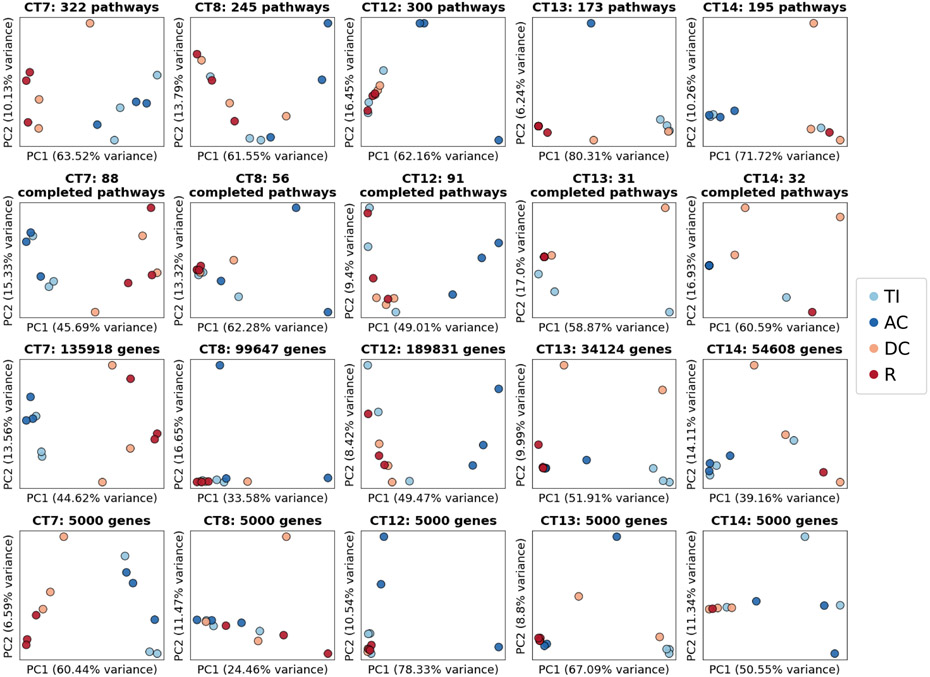

Variation in mucosal microbes longitudinally in the GI tract

Whether mucosa-associated microbes vary along the GI tract has been challenging to determine due to the low number of microbial reads that could be recovered from mucosal biopsies.12 We first tested whether microbial variation between GI sites is present at the genus-level. For each participant sample, we used quantitative33 16S rRNA gene sequencing to quantify genus-level microbial changes longitudinally along the GI tract. Microbial taxa from the proximal colon (terminal ileum [TI] and ascending colon [AC]) and taxa from the distal colon (descending colon [DC] and rectum [R]) showed some clustering by location in most participants (Fig 4E). Each participant sample was shotgun sequenced to test whether the observed variation in taxa along the GI tract extended to the species, pathway, or gene levels. Clustering between the TI/AC vs the DC/R was seen in some participants across species, namely in participants CT7, CT12, CT13, and CT14 (Fig 4F). There appeared to be minimal clustering between the TI/AC vs the DC/R at the pathway and gene-level (Fig ED3). Additionally, there was high variation within regions for some individuals, which may be attributed to read depth limitations. For example, for one DC sample from CT13 no microbial marker genes were identified due to the minimal number of non-host reads (Fig 4F).

Shotgun sequencing of MEM-treated human intestinal biopsies enabled characterization of high- and low-abundance microbial species, pathways, and genes. This characterization documented longitudinal shifts in the mucosal microbiome along the lower human GI tract. To investigate whether a single microbial strain varies along the GI tract, we next attempted to assemble microbial genomes from MEM-treated intestinal biopsies.

MEM enables MAG construction of intestinal microbes from human biopsies

To determine whether metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) could be constructed after processing with MEM, we selected two control and two MEM-treated biopsies with similar bacterial loads from participant CT18 (Fig 3A, 4A). Samples were shotgun-sequenced and processed for genome reconstruction as previously described.15 We sequenced both control and MEM-treated biopsies to measure the additional information MEM treatment can help yield at equivalent sequencing depths. After processing, host reads were removed bioinformatically and over 20% of reads were identified as non-host in MEM-treated samples whereas roughly 0.01% of reads were identified as non-host in the untreated controls (Fig 5A).

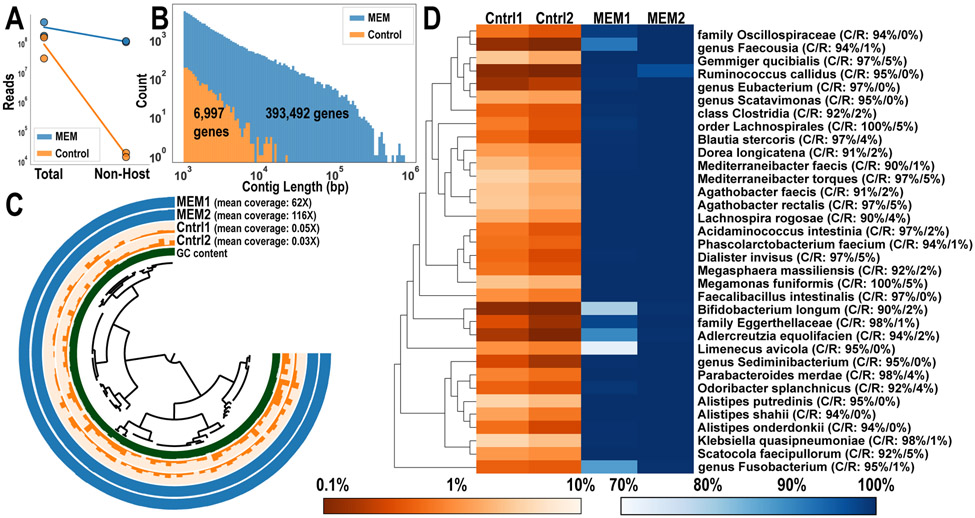

Figure 5: MAG construction with MEM-treated human intestinal biopsies performed from shotgun metagenomic sequencing.

A) Two control and two MEM-treated biopsies from the same participant (CT18) and intestinal region (ascending colon) were shotgun-sequenced. Number of non-host reads were determined after alignment to a human reference genome. B) Contigs were constructed from co-assembly of the two samples from each condition and the distribution of contig lengths was plotted. The number of prokaryotic genes identified in these contigs is shown. C) MAG of Alistipes putredinis was constructed from co-assembled MEM biopsies. Bar heights represent mean coverage and are scaled independently for each sample. D) From co-assembly of MEM biopsies, 34 high-quality MAGs (>90% complete, <5% redundant) were constructed de novo. Heatmap shows the percentage of each genome that is covered at least 1X by the sample (i.e., detection or breath of coverage), with a maximum of 3.7% in control samples and 99.999% in MEM samples. The average detection for MEM1, MEM2, Cntrl1, and Cntrl2 were 97.3% (SD: 6.4%), 99.8% (SD: 0.7%), 1.2% (SD: 1.1%), and 0.8% (SD: 0.7%) respectively across all MAGs. Taxonomy was assigned for each MAG and listed to the right along with completion/redundancy (C/R). The phylogenetic tree to the left of the heatmap highlights taxonomic grouping of each MAG.

We first tried to reconstruct MAGs from the control samples, however, the assembly of the short reads from non-host-depleted samples and our subsequent attempts to bin the resulting contigs into MAGs were unsuccessful because these assemblies suffered from remarkably short contigs (Fig 5B). Co-assembly was then performed on MEM-treated samples and resulted in substantially more and longer contigs compared with the control samples, with contig lengths of up to 833 kbp (Fig 5B & Table S8). Automatic binning and manual refinement steps resulted in a total of 34 high-quality bacterial MAGs (more than 90% complete and less than 5% redundant) and more than 70 medium-quality MAGs (more than 50% complete and less than 10% redundant), demonstrating how MEM treatment of human intestinal biopsies makes it possible to reconstruct MAGs from these samples. For the 34 high-quality MAGs, we computed detection, which reports the proportion of nucleotides in a given reference sequence that are covered by at least one short read in a given metagenome. Thus, detection is an extremely effective way to be able to discuss the presence of a given population in a given sample, independent of read coverage, and by avoiding false positives due to non-specific read recruitment. To confirm that the MAGs reconstructed from MEM-treated samples were accurate representations of the untreated biopsies, we assessed the uniformity of coverage of the control reads when mapped back onto the MAGs (Fig. 5C). To perform this analysis, we chose a MAG resolved to Alistipes putredinis, a known gut microbe that had the highest detection in the control samples. Control samples showed an even distribution of reads among the 29 contigs present, indicating that this MAG was also present in the control samples, but sequencing depth limitations prevented the reconstruction of a genome. Overall, we observed a higher detection of all 34 high-quality MAGs in MEM-treated samples compared to control samples (Fig 5D).

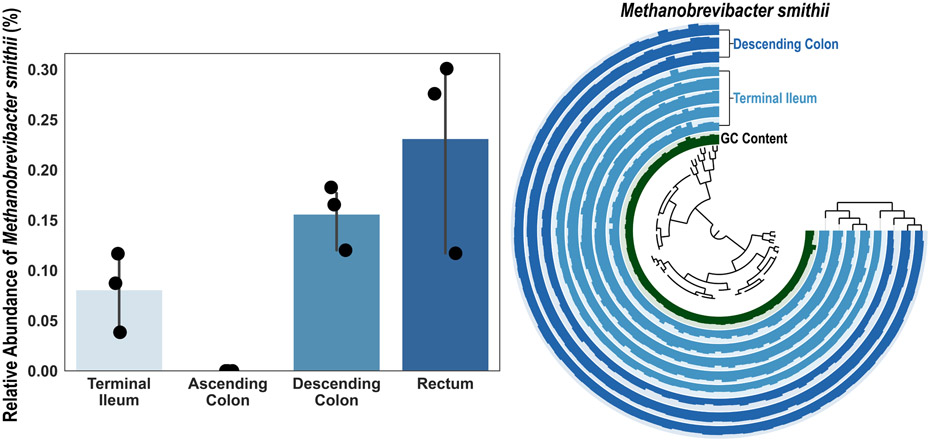

To quantify whether reads from control samples mapped back onto all 34 high-quality MAGs, detection was plotted for each MAG (Fig 5D). Next, to assess whether any of these MAGs were contaminated, we performed taxonomic classification on each genome. With a threshold of 95% average nucleotide identity (ANI), 33 MAGs were successfully classified. We compared the size of each classified MAG with the matching reference genomes in GTDB and found high agreement with current microbial databases (R2= 0.78, P= 4.32 x 10−12, Pearson coefficient of determination) indicating that the MAGs constructed from MEM-treated samples were not artifacts (Table S9-10). One Fusobacterium MAG matched closely with a published fecal-derived MAG at 86.85% ANI, but GTDB was unable to assign species-level taxonomy (Fig S7). Because all MAGs were constructed in the same manner and with similar quality metrics, it is likely that this Fusobacterium MAG is a uncharacterized taxon rather than contamination. We also wanted to quantify the range of microbial diversity we could capture with MAGs. These 34 MAGs spanned six bacterial phyla (Fig 5D) and an archaeon (Methanobrevibacter smithii) MAG was constructed from participant CT12, demonstrating MEM-treated biopsies enabled genome reconstruction of archaea and a wide variety of bacteria (Fig ED4). For the first time, using MEM, high-quality microbial MAGs were reconstructed from microbes from human intestinal biopsies at relative abundances down to 1%.

MEM identifies distinct microbial strains across individuals

After establishing the feasibility of MAG construction directly from human intestinal biopsies, we next investigated how microbial genomes may vary across individuals and within individuals. To determine whether MEM enables differentiation of population-level microbial differences across individuals within a single taxon, a total of six biopsies from participant CT12 were re-sequenced to a sequencing depth of roughly 250 million reads. Assembly and binning were performed on each of the six biopsies individually and MAGs were dereplicated across samples. A MAG of Phocaeicola vulgatus, the most prevalent and abundant species found in all participants, from participant CT12 was constructed and annotated (Fig 6A). Reads from all 60 intestinal biopsies taken from all five participants were then mapped onto this MAG to identify which genes were absent from the other participants’ biopsies.

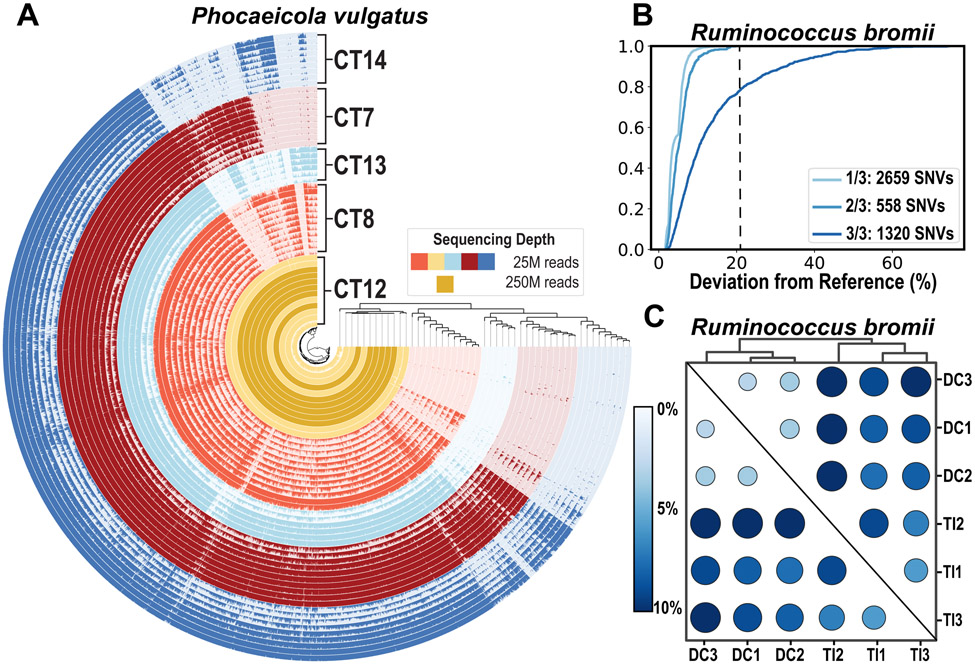

Figure 6: Interindividual and intraindividual bacterial biodiversity present along GI tract.

A) Gene-level analysis was performed on Phocaeicola vulgatus for all five participants. Samples were grouped by gene detection, defined as percentage of each gene with at least 1X coverage, and showed strong participant-dependent grouping but lacked grouping by GI location. B) ECDF of the occurrence of single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) in a MAG of Ruminococcus bromii and the deviation of these SNVs from the reference across three technical replicates. 1/3, 2/3, and 3/3 indicates the number of technical replicates that had an SNV at that location followed by the total number of SNVs in each of these categories. A black dashed line is drawn at 21% deviation from reference; above this value, all observed SNVs were present in all three technical replicates. C) Nucleotide-level analysis was performed on MAGs with a mean coverage above 50X across all samples. Shown here is the fixation index from SNVs analyzed within the coding region of R. bromii with a minimum deviation from reference set at 21%. Samples were clustered based on fixation index and strong region-dependent groupings can be seen. DC, descending colon; TI, terminal ileum.

A gene-resolved analysis of naturally occurring P. vulgatus populations through metagenomic read recruitment was performed, as described previously,42 and revealed a large core genome, and differentially occurring genes across individuals (Fig 6A). Genes from biopsies taken across GI tract regions within participant CT12 appeared conserved (CT12 samples had an average gene detection of > 96%). Some genes with high detection were only found in one or two participants (either CT12 only or CT12 and one other participant), which we defined as unique genes. To assess whether these genes were functionally distinct, genes were annotated with the Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COG) database to identify orthologous genes. Of the 287 genes unique to CT12, 100 of these were annotated by COG and corresponded to a wide range of functions (Fig S8). Of the gene clusters unique to two participants (i.e., CT12 and one other individual), about 30% were annotated (Fig S8). MEM treatment enables insights into functionally distinct microbial populations of the same taxon that occupy the same geographical location in the gut across individuals with similar health status.

SNVs detectable across GI tract regions within an individual

Finally, we investigated whether MEM treatment could enable studies of microbial population genetics in low-biomass samples through single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) as a result of the increased depth of coverage. For this analysis, we analyzed MAGs from participant CT12 as reference genomes and mapped the paired-end reads from the terminal ileum and descending colon from CT12 onto these assembled genomes. Six MAGs had a mean coverage above 50X across all 6 samples (3 terminal ileum and 3 descending colon) and were selected for subsequent SNV analysis (Fig S9). SNV profiles were generated from the paired-end reads of each sample by comparing them with the reference sequence (MAG). We investigated whether PCR errors may be responsible for some of the SNVs observed in our data by preparing libraries for an additional three technical replicates from a single terminal ileum biopsy (Fig 6B), with the expectation that differences in the SNV profiles of the technical replicates should be minimal. By looking at nucleotide variations occurring in one, two, or all three replicates, we observed that a minimum deviation from the reference nucleotide of 21% for Ruminococcus bromii (Fig 6B) allowed for the selection of SNVs only and minimized the impact of PCR errors in the population structure analysis. Analyses of these data using fixation index showed that some taxa, such as R. bromii (Fig 6C) and Gemmiger formicilis (Fig S9), were composed of subpopulations that were distinct between the upper and lower intestinal tract. To assess whether these SNVs were functionally important, codon-level and translated (amino acid) analyses of SNVs in R. bromii were performed and similar clustering of biopsies by location was detected (Fig ED5). The recovery of SNVs afforded by the deeper sequencing and increased coverage of MAGs from biopsy samples allowed us to detect the presence of subpopulation structures for some individual taxa along the lower GI tract of a single individual.

Discussion

MEM is a microbial-enrichment method for use on mammalian host-rich sample types which enables metagenome shotgun sequencing and analysis of microbes present in these samples. MEM enables over 1,000-fold removal of host DNA from solid mammalian tissue while minimally perturbing the microbial community composition. MEM is simple and fast, with processing times less than 30 min, facilitating integration into a laboratory or clinical workflow without in-person training. MEM is highly compatible with downstream shotgun sequencing of microbial DNA, leading to the detection of over 400-fold more species and genes, including low-abundance species, compared with control samples of a similar sequencing depth. MEM enabled the first culture-independent assembly of whole microbial genomes at relative abundances as low as 1% directly from human intestinal biopsies. The assembly of MAGs enables investigation of subpopulation variation across individuals and within an individual’s GI tract.

We acknowledge the following limitations of the MEM approach demonstrated here. We have analyzed biopsies with as few as 102 16S rRNA gene copies/μL in the 100 μL elution from the extraction column (corresponding to ~104 16S copies/mg of tissue), however deep analysis of samples below this bacterial load will require greater levels of host depletion and/or greater sequencing depth (Fig ED1-2). We advise users to refer to Fig ED1 to predict the percentage of non-host reads from bacterial load to guide sequencing depth decisions. We have successfully applied MEM to healthy intestinal biopsies but additional validation should be performed on samples with characteristics that could interfere with analysis, e.g. samples with active inflammation or bleeding. We have successfully applied MEM to fresh samples, but additional validation should be performed on preserved tissue samples. We have only characterized the impact MEM has on bacteria and archaea. Future studies should understand whether MEM affects the mycobiome and virome.

MEM provides the research community with the capability to deeply understand microbes integrated in mammalian host tissues and in mammalian host-rich samples. Here, MEM was validated on mouse feces and intestinal scrapings, rat colon sections, human saliva, and human intestinal biopsies. To extend the utility of MEM beyond mammals, future studies will be needed to optimize and validate MEM on samples from plants,43,44, insects45,46 and other non-mammalian hosts. Sample-processing with MEM will also enable higher throughput and less expensive microbiome investigations even in samples with moderate host loads (e.g., saliva in which enrichment of microbial reads from 10% to 95% cuts sequencing costs by an order of magnitude). We are especially motivated by the opportunities that MEM provides to investigate human-associated microbiomes. In fundamental studies, MEM would benefit researchers investigating evolution and dynamics of microbes and microbial genes across time and across interconnected ecological niches, such as within the human gastrointestinal tract. In clinical studies, we anticipate that MEM will provide researchers thecapability to investigate tumor microbiomes,2,3,47,48 mucosal intestinal microbiomes,4,9,12,49-51 tissue translocation of gut microbes,52,53 and the roles of tissue-associated microbes in complex immune disorders,9,54,55 immune modulation56 and cancer development. 2,57,58

METHODS

Sample Collection

Mice (stool samples).

All animal husbandry and experiments were approved by the Caltech Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC protocol #21-1769). Male and female wild-type, non-transgenic surplus mice were used for stool collection. These animals were being fed a standard chow (LabDiet Cat# 3005740-220) prior to stool collection. The stool was freshly collected by gently handling the mice. A total of 3 stool pellets from 3 different mice were collected at a time and were transferred to clean microfuge tubes with sterile tweezers. Samples were stored on ice for up to 30 min before being processed in the laboratory. A total of 1 mL of saline was added to each stool pellet and the samples were homogenized by pipetting. Homogenized stool samples were diluted 3-fold in saline and 100 μL from each diluted stool sample was processed with various host-depletion methodologies (see “MEM” and “Methodological comparisons with published host-depletion protocols”).

Rat (small intestine and colonic samples).

Tissue collection was performed post-mortem through an institutional tissue sharing program that does not require IACUC approval. One wild-type Syngap surplus rat was euthanized with CO2 and the small intestine was removed with sterilized tweezers. The rat was being fed a standard chow (LabDiet Cat# 3005740-220) but was fasted for 6 hours prior to sample collection.

A portion of the small intestine that appeared clear of content was cut and placed on a petri dish on ice. Any remnant lumenal contents were removed by squeezing the intestine with tweezers. The intestine was then cut and opened longitudinally with the mucosa facing upwards. A sterile glass slide was used to scrape the small intestine mucosa and placed into a clean microfuge tube on ice. Samples were stored on ice for up to 30 min before being processed in the laboratory. Mucosal scrapings were mixed and separated into 13 clean microfuge tubes, each tube containing a couple milligrams of tissues (see “MEM” and “Methodological comparisons with published host-depletion protocols”).

The large intestine was placed on a separate petri dish on ice and any luminal contents were removed by squeezing the intestine with tweezers. The entire large intestine was then cut into 14 evenly sized pieces with a sterile scalpel. Sterile tweezers were used to transfer each intestinal piece into a clean microfuge tube on ice. Samples were stored on ice for up to 30 min before being processed in the laboratory (see “MEM” and “Methodological Comparisons”).

Human (saliva samples).

Human saliva samples were acquired from two healthy adult volunteers and analyzed under California Institute of Technology Institutional Review Board (IRB) protocol #21-1092. All participants provided (digital) written informed consent prior to donation. No personal identifying information was collected at the time of consent and participant specimens were coded. Volunteers were asked not to eat, drink, chew gum, brush their teeth, or smoke 30 min prior to collection. No volunteers had taken systemic antibiotics for at least 2 weeks prior to donation. Volunteers were instructed to pool saliva in their mouths and spit 2 mL of saliva, ignoring bubbles when estimating volume, into a 15 mL conical tube through a plastic funnel. Prior to undergoing MEM, saliva samples underwent a DTT (dithiothreitol) pre-treatment in some experiments. Saliva was mixed at a 1:1 ratio with fresh DTT (10 mM DTT in 1X PBS, Sigma Aldrich Cat# 43815), vortexed briefly, and incubated for 1 min at room temperature before undergoing host-depletion processing (see “MEM” and “Methodological comparisons”).

Human (tissue samples).

All activities related to enrollment of participants, collection of samples, and sample analysis were approved by the University of Chicago IRB and performed under IRB protocols #15573A and #13-1080. De-identified samples were received at Caltech and analyzed under Caltech IRB protocol #21-1083. Adults scheduled for routine colon cancer screenings via colonoscopy at the University of Chicago Medicine (UCM) were screened for diagnosis and eligibility criteria for enrollment in the study on a weekly basis. Exclusion criteria included: participants with chronic infectious diseases such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or hepatitis C (HCV); active, untreated Clostridium difficile infection; active infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2); intravenous or illicit drug use such as cocaine, heroin, non-prescription methamphetamines; active use of blood thinners; severe comorbid diseases; participants on active cancer treatment; and participants who were pregnant. Approaching prospective participants was at the discretion of their treating physician and was not done in cases that would put participants at any increased risk, regardless of reason. Participants were approached the day of their procedure and informed, written consent was obtained before any samples were acquired.

Human Ascending Colon Paired MEM and Control (Figure Fig 3D)

To assess the impact of MEM on intestinal microbes, 8 ascending colon biopsies, designated as 10 cm distal to the ileocecal valve, were collected from a single field of view (5 cm diameter) for five different participants (Fig 3A). Biopsies were collected in a total of 2-3 passages with 3-4 biopsies per passage using a pair of 2.8-mm biopsy forceps. Biopsies from the same passage were stored together on ice in a dry microfuge tube for an average of 28 min (ranging from 15 min to 36 min). After samples were transferred to the lab, biopsies from the same passage were split into control and MEM groups for a total of 4 biopsies per condition with evenly sized biopsies present in each group. Biopsy size ranged from 0.2 mg to 4.8 mg with an average weight of 2.49 mg. Non-host-depleted biopsies were processed individually by adding 150 μL of PrimeStore MTM inactivation buffer (Longhorn) to each biopsy and vortexing briefly before storing at -80 °C until DNA extraction. Depleted samples were processed individually at University of Chicago (see “MEM”) before shipment on dry ice to Caltech for DNA extraction.

Longitudinal Sampling of the Human Intestinal Tract (Figure 4C)

For longitudinal sampling, a total of five participants were sampled 12 times from 4 different locations during a routine colonoscopy. The 4 locations sampled were the terminal ileum, ascending colon (designated as 10 cm distal to the ileocecal valve), descending colon, and rectum. From a single field of view (5 cm diameter) from each location, 3 biopsies were collected in one passage with 2.8 mm biopsy forceps and stored dry on ice in a microfuge. For participant CT14, only one rectal sample was obtained. On average, biopsies were 2.5 mg with a minimum size of 0.1 mg and a maximum of 5.9 mg. All biopsies were then processed individually in the laboratory at University of Chicago (see “MEM”) before shipment on dry ice to Caltech for DNA extraction. Time between specimen collection and processing ranged from 10 min to 52 min. Samples were processed individually in the laboratory at University of Chicago (see “MEM”) before shipment on dry ice to Caltech for DNA extraction. Additionally, three microfuge tubes of 400 μL saline were opened and closed in the laboratory and processed with MEM to serve as clinical processing blanks.

Depletion Protocols

Microbial-Enrichment Method (MEM).

Samples for MEM treatment were placed into 2-mL 1.4-mm ceramic bead-beating tubes (Lysing Matrix D from MP Biomedical, Cat #116913050-CF) with a maximum volume of 400 μL. For solid sample types (stool and intestinal tissue), up to 400 μL of saline (0.9% NaCl, autoclaved) was added into the bead-beating tube. Samples were homogenized using FastPrep-24 (MP Biomedical Cat #116004500) for 30 sec at 4.5 m/sec and then immediately placed on ice. A total of 150 μL of homogenized tissue was removed and placed into a clean microfuge tube containing 10 μL of buffer (100 mM Tris + 40 mM MgCl2, pH 8.0 and 0.22 μm sterile filtered), 33 μL of saline (0.9% NaCl, autoclaved), 2 μL of Benzonase Nuclease HC (EMD Millipore Cat # 71205), and 5 μL of Proteinase K (NEB Cat # P8107S). Samples were mixed lightly by manually pipetting up and down 5-10 times and spun briefly to pool (1,000 x g for 5 seconds). Tubes were placed on a dry block incubator for 15 min at 37 °C with shaking at 600 rpm. Samples were then pelleted at 10,000 xg for 2 min and the supernatant was removed and discarded. Pellets were resuspended in 150 μL of PrimeStore MTM (Longhorn), a transport medium, to inactivate residual enzymatic activity and stored at −80 °C until nucleic-acid extraction. The initial MEM protocol utilized DNase I treatment in place of Benzonase. However, we noted continuous microbial lysis during DNase I heat inactivation. Benzonase was used to remove high heat steps as it is fully inactivated by PrimeStore MTM.

Methodological Comparisons with Published Host-depletion Protocols.

For all mouse, rat, and human saliva samples, the following published protocols were conducted to compare with MEM.

MolYsis.

Host removal was performed with MolYsis Basic5 (Molzym Cat# D-301-050) following the manufacturer’s protocol. A proteinase K pre-treatment (10 μL of NEB Proteinase K (Cat # P8107S)) was performed on solid-tissue samples (stool and intestinal samples) based on Molyzm’s recommendations. The entire protocol was performed, including the additional BugLysis step before nucleic-acid extraction (see “DNA Extraction”).

QIAamp Microbiome.

Host removal was performed with QIAamp DNA Microbiome Kit (Qiagen Cat# 51704) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Buffer AHL was aliquoted upon kit arrival and was not freeze-thawed more than once. In order to remove confounding factors from different DNA-extraction kits, the QIAamp DNA Microbiome Kit protocol was followed until the proteinase K incubation and the sample was then processed for nucleic-acid extraction (see “DNA Extraction”).

lyPMA.

A previously published protocol known as lyPMA, was tested according to the paper’s specifications. Liquid samples (diluted stool and saliva) were pelleted at 10,000 x g for 8 min. Supernatant was removed and the pellet was resuspended in 200 μL of nuclease-free (NF) water with a light vortex. Samples were left at room temperature (RT) for 5 min. After samples were covered with foil, 10 μM of PMA (propidium monoazide) was added and mixed by lightly vortexing each tube for a few seconds. Samples were incubated for 5 min in the dark at RT before being placed on ice <20 cm from a fluorescent bulb. Samples were incubated under light for 25 min with a quick centrifugation and rotation every 5 min. All samples were then processed for nucleic-acid extraction (see “DNA Extraction”). The lyPMA method was not tested on rat colonic sectionals due to the limited efficacy of osmotic lysis on solid tissues seen from mouse mucosa samples.

DNA Extraction.

Nucleic acids were isolated following Qiagen’s AllPrep PowerViral DNA/RNA Kit (Cat # 28000-50). Samples were homogenized in 0.1 mm glass beads for 1 min at 6m/s using FastPrep-24 (MP Biomedical Cat #116004500) to ensure complete microbial lysis.59 A maximum of 24 clinical samples were processed at a time and at least 3 processing blanks were run on each extraction kit. Samples were eluted into 100 μL of NF water. It should be noted that standard microbial bead-beating with 0.1 mm beads was not sufficient to completely lyse intact (control) biopsies in this study. Control biopsies were homogenized with Lysis Matrix E (MP Biomedical Cat # 116914050-CF) for 1 min at 6 m/sec three times with a 5-min incubation on ice between each bead-beating.

Quantification of Host DNA.

Host load present in extracted DNA was characterized by droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) of a single-copy gene. For human saliva and tissue samples, the gene EIF5B was amplified based on primers found from literature60 (Forward: GCCAAACTTCAGCCTTCTCTTC and Reverse: CTCTGGCAACATTTCACACTACA). For samples originating from rodents, the gene Cyp8b1 was amplified based on primers found from literature61 (F: GGCTGGCTTCCTGAGCTTATT and R: ACTTCCTGAACAGCTCATCGG). Samples were amplified on the C-1000 thermocycler (Bio-Rad Cat #1851196) and quantified using the QX200 droplet digital PCR system (Bio-rad Cat #1864001). The concentrations of the components in the ddPCR mix used in this study were as follows: 1x QX200 ddPCR EvaGreen SuperMix (Bio-Rad Cat# 1864035), 500 nM forward primer, and 500 nM reverse primer for a total reaction volume of 25 μL. Thermocycling was performed as follows: 95 °C for 5 min, 40 cycles of 95 °C for 30 sec, 60 °C for 30 sec, and 68 °C for 30 sec, followed by a dye-stabilization step at 4 °C for 5 min and 90 °C for 5 min. All ramp rates were 2 °C per sec. LOB refers to limit of blank defined as LoB = meanblank + 1.645[SDblank] based on three processing blanks).

Quant-Seq.

Microbial characterization and quantification was performed using the quantitative sequencing (“Quant-Seq”) pipeline we have described previously.33 Due to the low bacterial loads present in intestinal biopsies, Quant-Seq was also performed on three MEM processing blanks. If a taxon was detected at a higher absolute abundance in any of the processing blanks compared to the intestinal biopsies, the taxon was removed from downstream analysis.

Shotgun Sequencing.

Extracted DNA was prepared for sequencing using Illumina DNA Prep (Cat #20018704). A maximum input of 500 ng of DNA was used for library prep. After processing with the MEM protocol, almost all human biopsy samples had less than Illumina’s recommended minimal DNA input amount of 1ng and were below the limit of detection of the Qubit double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) High Sensitivity assay (Thermo Cat #Q32851). Estimations of input DNA were made using 16S rRNA gene ddPCR (see “Quant-Seq” section) and host quantification (see “Quantification of Host DNA” section and Equation 1). For these calculations, we assumed the 16S rRNA gene copy number (4 per cell), total DNA per microbial cell (3fg based on average genome size of 3Mb), and absence of non-host/non-prokaryotic DNA.

| Equation 1: |

For samples with DNA concentrations below Illumina’s recommended input, additional PCR cycles were added to the amplification step based on DNA input (Supplemental Table 11).

Finished libraries were quantified through Qubit’s dsDNA High Sensitivity assay and a High Sensitivity D1000 TapeStation Chip (Agilent Cat #5067-5585, #5067-5584). If additional peaks were seen at 45bp or 120bp, indicating the presence of primer dimers or adapter dimers, we performed an additional clean-up step with AMPureXP beads (Beckman Coulter, Cat #A63880) at a ratio of 0.8:1 of beads to library volume. For quantification, finalized libraries were amplified on the CFX-96 qPCR (Bio-Rad Cat # 1855196) with primers targeting the Illumina adapter sequence (F: AAT GAT ACG GCG ACC ACC GA and R: CAA GCA GAA GAC GGC ATA CGA). Libraries were diluted 1:40,000 in NF water prior to amplification to fall within the range of KAPA standards concentrations (Roche Cat #07960387001) for quantification. The concentrations of the components in the qPCR mix used were as follows: 1x SsoFast EvaGreen Supermix (Bio-Rad Cat# 1725201), 125 nM forward primer, and 125 nM reverse primer for a total reaction volume of 10uL. Thermocycling was performed as follows: 95 °C for 5 min, 40 cycles of 95 °C for 30 sec and 60 °C for 45 sec, followed by a melt-curve step at 95 °C for 15 sec, 50 °C for 15 sec, 70 °C for 1 sec, and 95 °C for 5 sec. Pooled samples were quantified through Qubit’s dsDNA High Sensitivity assay and a High Sensitivity D1000 TapeStation Chip before submitting the samples for sequencing. Sequencing was performed by Fulgent Genetics using the Illumina NovaSeq6000 platform. Sequencing batch 1 was performed on the NovaSeq6000 SP flow cell and 2x100bp reagent kit for paired-end sequencing with an average sequencing depth of 23M reads. Sequencing batch 2 was used for MAG assembly and was performed on one NovaSeq6000 S4 lane and 2x150bp reagent kit for paired-end sequencing with an average sequencing depth of 223M reads. Samples were demultiplexed on the NovaSeq6000 and raw fastq files for read 1 and read 2 were provided along with fastqc files for each sample.

The number of non-host reads obtained from each sample can be accurately predicted based on a single qPCR measurement of bacterial load (16S rRNA gene copies) (ED1) and can be utilized to inform necessary sequencing depth.

Marker Gene Analyses.

Sequencing data was processed using the KneadData v0.10.062. Through KneadData, quality control (QC) and host removal were performed with Trimmomatic v0.3963. Human derived sample types were aligned to KneadData’s default human reference genome (a combination of hg38 human genome reference (GenBank assembly accession # GCA_000001405.29) and small contaminant sequences) and aligned reads were removed. Samples acquired from mice were processed using the reference genome GRCm39 constructed from C57BL/6J mouse-strains (GenBank assembly accession #GCA_000001635.9). After bioinformatic host removal, the percentages of host reads were calculated by dividing reads remaining after host filtering by the total reads that passed QC. To assign species, non-host reads from read 1 and read 2 were then concatenated and processed using the Metaphlan 3.0 workflow outlined in bioBakery (https://github.com/biobakery/biobakery) under default settings (Database: mpa_v30_CHOCOPhlAn_201901)62.

HUMAnN Pathway and Gene Alignment.

Non-host read 1 and read 2 outputted from KneadData were concatenated and processed using the HUMAnN 3.0 workflow outlined in bioBakery (https://github.com/biobakery/biobakery) under default settings.62 Taxonomic profiles obtained from MetaPhlan (see “Marker Gene Analyses”) were merged within participants and used as taxonomic inputs using the “--taxonomic-profile" flag in HUMAnN. Reported pathway abundances and gene abundances were normalized to relative abundances and concatenated. For stool, nearly 90% of the non-host reads did not align to known bacteria in the HUMAnN databases, likely due to the bias toward human microbiome datasets.

MAG Assembly.

Sequencing data was processed using the metagenomic workflow67,68 outlined in anvi’o69,70 v7.1 (https://anvio.org). QC filtering of short reads was performed using the Illumina-utils library71 v2.12. Host reads were removed by alignment to the hg38 human genome reference (GenBank assembly accession # GCA_000001405.29). Assembly was performed on each sample individually using MEGAHIT72 v1.2.9 unless co-assembly was explicitly stated as in figure 4, with default setting except setting a minimum contig length of 1000bp. Short reads generated from each sample were then aligned to contigs generated from all assemblies using Bowtie265 v2.3.5. Contigs were processed using anvi’o to generate a contig databases with the command “anvi-gen-contigs-database” with default settings and with Prodigal 73 v2.6.3 to identify open reading frames. Single-copy core genes were detected with “anvi-run-hmm” to (bacteria n = 71 and archaea n = 76, modified from Lee, 201974, ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs) (n = 12, modified from https://github.com/tseemann/barrnap) using HMMer75,76 v3.3.2. Genes were annotated using both ‘anvi-run-ncbi-cogs’ for NCBI’s Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COGs) database77 and ‘anvi-run-kegg-kofams’ from the KOfam HMM database of KEGG orthologs (KOs)78. BAM files were profiled with “anvi-profile” and merged with “anvi-merge” for samples originating from the same participant. Automatic binning was performed by CONCOCT79 v1.1.0by specifying a maximum number of bins based on the estimated number of bacterial genomes computed from each sample’s contigs. The maximum number of bins was set to 1/3 the number of expected genomes to limit the likelihood of fragmentation. Bins generated with CONCOCT were imported in the anvi’o profile database and were then manually refined and summarized to obtain fasta files of individual MAGs. Once manual binning of all samples from the same participant was complete, MAGs above 50% complete were dereplicated to generate a unique list of genomes using anvi’o and pyani v0.2.11. Representative genomes were chosen based on quality scores and clustered based on >95% ANI. The final list of MAGs were taxonomically assigned with GTDB-Tk (Genome Taxonomy Database Toolkit; v2.1.040,41) using classify_wf with default settings.

Strain Analysis Across Individuals.

A Phocaeicola vulgatus MAG from the terminal ileum of CT12 was selected as a reference genome based on genome length. Open reading frames (ORFs) were identified through Prodigal for the P. vulgatus reference genome. Non-host reads from four participants (CT7, CT12, CT13, and CT14) were mapped onto the P. vulgatus reference genome by following anvi’o’s metagenomics workflow using reference mode. For each sample and each gene present in the P. vulgatus reference genome, gene detection was calculated. Gene detection refers to the percentage of each gene sequence with at least 1X coverage. The average detection across all genes present within the P. vulgatus MAG was calculated and samples with a mean detection below 0.25 were removed from the final analysis. Pangenome visualization was performed in anvi’o interactive interface using the gene-mode flag with sorting of samples and genes by detection.

Analyses of SNVs.

One TI sample from CT12 was split into 3 technical replicates prior to library preparation and each replicate was sequenced at a depth of 150M to 250M reads in sequencing batch 2. SNV analyses across these samples were performed with anvi’o after dereplication using the command “anvi-gen-variability-profile” with a minimum mean coverage of 50X in all samples. Biological SNVs were classified as being present in all three technical replicates. SNVs present in only 1 or 2 technical replicates were classified as sequencing, PCR, or input errors. A threshold for minimum deviation from consensus was set based on the deviation required for all SNVs to be present in all technical replicates. This analysis was repeated for each MAG of interest (min mean coverage of 50X, n=6). After a threshold for minimum deviation from consensus was established, longitudinal samples from patient CT12 were analyzed using “anvi-gen-variability-profile” at the nucleotide, codon and amino acid level with the same minimum mean coverage of 50x and filtering out SNVs occurring in only one sample. The fixation index was computed using “anvi-gen-fixation-index-matrix” to describe the population structure between samples.

Extended Data

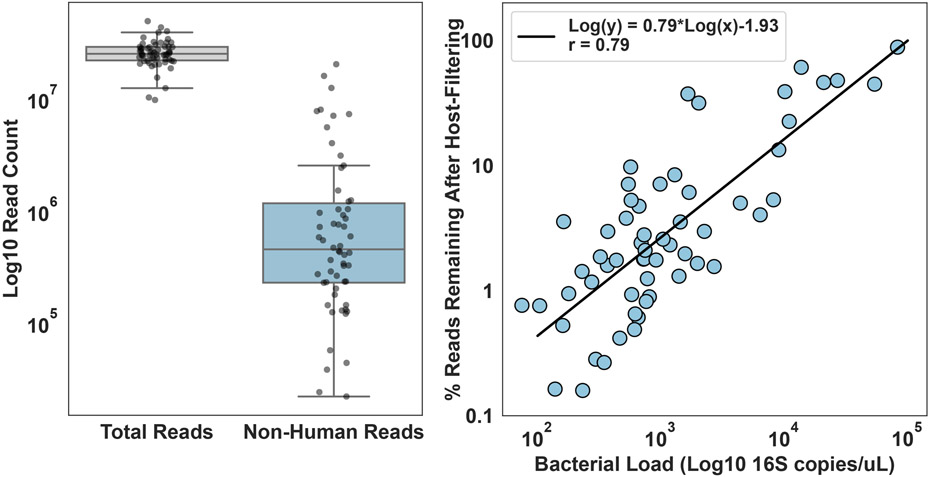

Extended Data Fig. 1. Correlation between bacterial load and non-host reads.

Shotgun sequencing was performed on longitudinally sampled intestinal biopsies after processing with host depletion (N=60 biological replicates). Roughly 25 million reads on average were obtained for each biopsy and all samples fit on a single NovaSeq S1 flowcell. After host-filtering an average of 2 million reads were remaining with a range from 2E4 reads to 2E7 reads. For each box, the middle horizontal line denotes mean values, boxes extend to the 25th and 75th percentile, and whiskers extend to the 1.5 interquartile range. The variability in non-host reads remaining had a strong correlation (Spearman, r=0.79) with the total microbial load as measured by digital PCR. This strong correlation indicated that our process was achieving a relatively uniform depletion across all samples. Additionally, the strong correlation indicates that the majority of non-human reads in our samples come from bacteria picked up by the 16S primers used for total microbial load quantification.

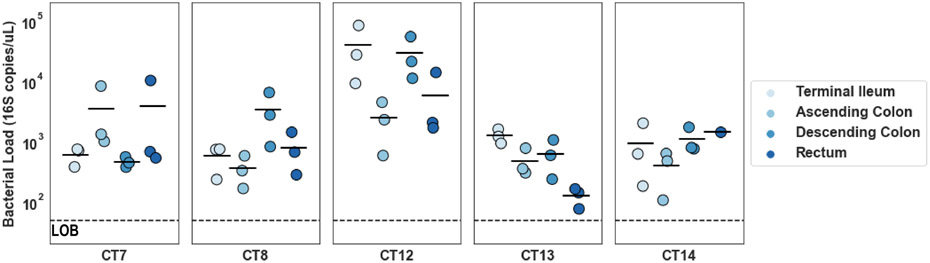

Extended Data Fig. 2. Bacterial loads of longitudinal biopsies.

16S rRNA gene copies were quantified as a proxy for bacterial load for all biopsies. Samples were plotted by participant and then by location. (N=3 biological replicates for each location for each patient, LOB refers to limit of blank defined as LoB = meanblank + 1.645[SDblank] based on three processing blanks).

Extended Data Fig. 3. Longitudinal variation at the pathways and gene-level.

PCA analysis was performed on all 60 longitudinal samples grouped by participant (CT7, CT8, CT12, CT13, and CT14). Shotgun-sequencing data was annotated for pathways and genes through HUMAnN 3. A) PCA on relative abundance of all pathways. B) PCA on relative abundance of completed pathways (defined as above 90% of modules being present). C) PCA on relative abundance of all genes. D) PCA on relative abundance of the top 5,000 most abundant genes in each participant.

Extended Data Fig. 4. Archaeon Methanobrevibacter smithii found along the lower GI tract.

From shotgun sequencing, we detected participant CT12 had low levels of Methanobrevibacter smithii present in the terminal ileum, descending colon, and rectal biopsies (N=3 biological replicates; error bars are 95% CI centered on the mean). MAG construction was performed on co-assembly of all biopsies taken from the terminal ileum and descending colon to reconstruct a full Methanobrevibacter smithii genome (completeness: 100%, redundancy: 0%).

Extended Data Fig. 5. Ruminococcus bromii strain variants at the nucleotide (SNV), codon (SCV), and amino acid (AA) level.

SNVs present in R. bromii above the threshold of 21% deviation from reference were analyzed at the codon and translated-level to determine if SNVs may indicate a functional change. The fixation index for each level of analysis were plotted.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge assistance with animal experiments from Caltech Office of Laboratory Animal Research. We thank Matt Ratanapanichkich (California Institute of Technology) for assistance on manual refinement of metagenomic bins and feedback on figure design. We thank Alyssa Carter (California Institute of Technology) for assistance with Quant-Seq library preparation, ddPCR measurements, and feedback during manuscript preparation. We thank Matt Cooper (California Institute of Technology) for identifying appropriate statistical tests, guidance during Quant-Seq analysis, and feedback on figure design. We thank Said R. Bogatyrev for preliminary investigations, discussions and advice. We thank Ojas Pradhan (California Institute of Technology) and Reid Akana (California Institute of Technology) for advice and feedback during manuscript preparation. We thank Benjamin McDonald (University of Chicago) for providing his expertise and advice on clinical sample collection and processing. We thank Anni Wang (University of Chicago) for her assistance in the processing of the human tissue for Figures 3-6. We thank Natasha Shelby (California Institute of Technology) for contributions to writing and editing this manuscript.

This work was funded in part by a grant from the Kenneth Rainin Foundation (2018-1207 to R.F.I.), the Army Research Office Multidisciplinary University Research Initiative (W911NF-17-1-0402 to R.F.I.), the Jacobs Institute for Molecular Engineering for Medicine, a NIH NIDDK grant (RC2 DK133947 to R.F.I. and B.J.), a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (DGE-1745301 to N.W), and a National Institutes of Health Biotechnology Leadership Pre-doctoral Training Program (BLP) fellowship from Caltech’s Donna and Benjamin M. Rosen Bioengineering Center (T32GM112592, to J.T.B.), a Helmsley Foundation grant (to F.T.), a NIH NIDDK grant (RC2 DK122394, to F.T.), a F30 (5F30DK121470, to D.G.S.), a R01 (DK067180, to B.J.), and the Digestive Diseases Research Core Center P30 DK42086 at the University of Chicago (to B.J.). The funders had no role in the design of the study, the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, nor in writing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Competing Interests Statement

The work in this paper is the subject of a patent application filed by Caltech (RFI, NW, JTB, AER). The other authors declare no competing interests.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available at CaltechDATA, https://doi.org/10.22002/gx69z-wec80. Microbial sequencing data for the main text and extended data figures is available at NCBI Accession PRJNA991155. Sequencing data from human samples have been host scrubbed using STAT80 sra-human-scrubber (https://github.com/ncbi/sra-human-scrubber) followed by alignment to CHM1381.

Code Availability

The code utilized in data processing and analysis is available at CaltechDATA, https://doi.org/10.22002/gx69z-wec80.

References

- 1.Tuganbaev T. et al. Diet Diurnally Regulates Small Intestinal Microbiome-Epithelial-Immune Homeostasis and Enteritis. Cell 182, 1441–1459 e1421, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.08.027 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dejea CM et al. Patients with familial adenomatous polyposis harbor colonic biofilms containing tumorigenic bacteria. Science 359, 592–597, doi: 10.1126/science.aah3648 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bullman S. et al. Analysis of Fusobacterium persistence and antibiotic response in colorectal cancer. Science 358, 1443–1448, doi: 10.1126/science.aal5240 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morgan XC et al. Dysfunction of the intestinal microbiome in inflammatory bowel disease and treatment. Genome Biol 13, R79, doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-9-r79 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caruso R, Lo BC & Nunez G Host-microbiota interactions in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Immunol 20, 411–426, doi: 10.1038/s41577-019-0268-7 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pascal V. et al. A microbial signature for Crohn's disease. Gut 66, 813–822, doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-313235 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gevers D. et al. The treatment-naive microbiome in new-onset Crohn’s disease. Cell Host Microbe 15, 382–392, doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.02.005 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng J. et al. Duodenal microbiota composition and mucosal homeostasis in pediatric celiac disease. BMC Gastroenterol 13, 113, doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-13-113 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Earley ZM et al. GATA4 controls regionalization of tissue immunity and commensal-driven immunopathology. Immunity, doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2022.12.009 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ringel Y. et al. High throughput sequencing reveals distinct microbial populations within the mucosal and luminal niches in healthy individuals. Gut microbes 6, 173–181, doi: 10.1080/19490976.2015.1044711 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parthasarathy G. et al. Relationship Between Microbiota of the Colonic Mucosa vs Feces and Symptoms, Colonic Transit, and Methane Production in Female Patients With Chronic Constipation. Gastroenterology 150, 367–379 e361, doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.10.005 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vaga S. et al. Compositional and functional differences of the mucosal microbiota along the intestine of healthy individuals. Sci Rep 10, 14977, doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-71939-2 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shen TD et al. The Mucosally-Adherent Rectal Microbiota Contains Features Unique to Alcohol-Related Cirrhosis. Gut microbes 13, 1987781, doi: 10.1080/19490976.2021.1987781 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klindworth A. et al. Evaluation of general 16S ribosomal RNA gene PCR primers for classical and next-generation sequencing-based diversity studies. Nucleic Acids Res 41, e1, doi: 10.1093/nar/gks808 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen LX, Anantharaman K, Shaiber A, Eren AM & Banfield JF Accurate and complete genomes from metagenomes. Genome research 30, 315–333, doi: 10.1101/gr.258640.119 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vineis JH et al. Patient-Specific Bacteroides Genome Variants in Pouchitis. mBio 7, doi: 10.1128/mBio.01713-16 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Groussin M, Mazel F & Alm EJ Co-evolution and Co-speciation of Host-Gut Bacteria Systems. Cell Host Microbe 28, 12–22, doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2020.06.013 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang GH, Dittmer J, Douglas B, Huang L & Brucker RM Coadaptation between host genome and microbiome under long-term xenobiotic-induced selection. Sci Adv 7, eabd4473, doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abd4473 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tyson GW et al. Community structure and metabolism through reconstruction of microbial genomes from the environment. Nature 428, 37–43, doi: 10.1038/nature02340 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pereira-Marques J. et al. Impact of Host DNA and Sequencing Depth on the Taxonomic Resolution of Whole Metagenome Sequencing for Microbiome Analysis. Front Microbiol 10, 1277, doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01277 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marotz CA et al. Improving saliva shotgun metagenomics by chemical host DNA depletion. Microbiome 6, 42, doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0426-3 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bruggeling CE et al. Optimized bacterial DNA isolation method for microbiome analysis of human tissues. Microbiologyopen 10, e1191, doi: 10.1002/mbo3.1191 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ganda E. et al. DNA Extraction and Host Depletion Methods Significantly Impact and Potentially Bias Bacterial Detection in a Biological Fluid. mSystems 6, e0061921, doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00619-21 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Avanzi C. et al. Red squirrels in the British Isles are infected with leprosy bacilli. Science 354, 744–747, doi: 10.1126/science.aah3783 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Charalampous T. et al. Nanopore metagenomics enables rapid clinical diagnosis of bacterial lower respiratory infection. Nature Biotechnology 37, 783–792, doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0156-5 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng WY et al. High Sensitivity of Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing in Colon Tissue Biopsy by Host DNA Depletion. Genomics, proteomics & bioinformatics, doi: 10.1016/j.gpb.2022.09.003 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oechslin CP et al. Limited Correlation of Shotgun Metagenomics Following Host Depletion and Routine Diagnostics for Viruses and Bacteria in Low Concentrated Surrogate and Clinical Samples. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 8, 375, doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00375 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hasan MR et al. Depletion of Human DNA in Spiked Clinical Specimens for Improvement of Sensitivity of Pathogen Detection by Next-Generation Sequencing. J Clin Microbiol 54, 919–927, doi: 10.1128/JCM.03050-15 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heravi FS, Zakrzewski M, Vickery K & Hu H Host DNA depletion efficiency of microbiome DNA enrichment methods in infected tissue samples. J Microbiol Methods 170, 105856, doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2020.105856 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shaffer JP et al. A comparison of six DNA extraction protocols for 16S, ITS and shotgun metagenomic sequencing of microbial communities. BioTechniques 73, 34–46, doi: 10.2144/btn-2022-0032 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hallmaier-Wacker LK, Lueert S, Roos C & Knauf S The impact of storage buffer, DNA extraction method, and polymerase on microbial analysis. Scientific Reports 8, 6292, doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-24573-y (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bellali S, Lagier JC, Raoult D & Bou Khalil J Among Live and Dead Bacteria, the Optimization of Sample Collection and Processing Remains Essential in Recovering Gut Microbiota Components. Front Microbiol 10, 1606, doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01606 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 33.Barlow JT, Bogatyrev SR & Ismagilov RF A quantitative sequencing framework for absolute abundance measurements of mucosal and lumenal microbial communities. Nat Commun 11, 2590, doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16224-6 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]