Abstract

The μE motifs of the immunoglobulin μ heavy-chain gene enhancer bind ubiquitously expressed proteins of the basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) family. These elements work together with other, more tissue-restricted elements to produce B-cell-specific enhancer activity by presently undefined combinatorial mechanisms. We found that μE2 contributed to transcription activation in B cells only when the μE3 site was intact, providing the first evidence for functional interactions between bHLH proteins. In vitro assays showed that bHLH zipper proteins binding to μE3 enhanced Ets-1 binding to μA. One of the consequences of this protein-protein interaction was to facilitate binding of a second bHLH protein, E47, to the μE2 site, thereby generating a three-protein–DNA complex. Furthermore, transcriptional synergy between bHLH and bHLH zipper factors also required an intermediate ETS protein, which may bridge the transcription activation domains of the bHLH factors. Our observations define an unusual form of cooperation between bHLH and ETS proteins and suggest mechanisms by which tissue-restricted and ubiquitous factors combine to generate tissue-specific enhancer activity.

The immunoglobulin (Ig) μ heavy-chain gene enhancer is a cell-specific transcription regulatory sequence. Located in the JH-Cμ intron, it is necessary for the expression of a rearranged IgH gene in transfection as well as transgenic assays. Moreover, when taken out of its normal context, the μ enhancer is sufficient to target a heterologous transgene (1, 14, 18, 27) for expression at the appropriate differentiation stage in the B-lymphocyte lineage. In addition to activating transcription from a VH gene promoter that has recombined into the Cμ locus, this enhancer has also been implicated in the initiation of V(D)J recombination at the IgH locus. This is based on two experimental observations: transgenic recombination substrates were shown to be activated by the μ enhancer (7), and genetic deletion of the endogenous enhancer was shown to suppress IgH recombination (4, 31). At present, it is not clear whether the recombination activation and transcription activation properties of the enhancer are directly related; however, it is likely that μ enhancer-mediated chromatin reorganization resulting in increased accessibility of the IgH locus to polymerases and recombinases is important for both processes.

B-cell-specific μ enhancer function is determined by multiple trans-acting nuclear proteins that bind to specific sites within the enhancer (6, 19). Proteins that bind to the enhancer can be broadly classified into two categories: those that are more restricted in their tissue distribution, such as μA, μB, and octamer binding proteins, and those that are ubiquitously expressed in most cell types, such as the μE1, μE2, μE3, and μE5 binding proteins. However, no μ enhancer binding protein identified to date has an expression pattern that correlates perfectly with the cells in which the IgH gene is expressed. Based on the expression pattern of proteins binding to the μA and μB sites, we have previously proposed that tissue specificity of the enhancer is the result of two essential enhancer binding proteins that have overlapping tissue distributions, with the enhancer being active only in those cells where both factors are coexpressed (20).

Tissue specificity may also be achieved, in part, by negative regulation of the enhancer. In particular, μE4 and μE5 motifs have been implicated in suppressing enhancer activity in non-B cells (30, 32) by binding the zinc finger protein ZEB (8). The μE2 to μE5 motifs contain a consensus CANNTG motif that binds the basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) family of transcription factors (12, 17). Mutational analysis of μE motifs has shown that loss of single elements does not significantly affect μ enhancer activity (13, 15, 23, 35). This observation has been interpreted to indicate that there is redundancy among the μE elements; that is, absence of one μE element can be functionally compensated for by other μE elements present in the enhancer. Although sequence similarity among the μE elements suggests that they have similar roles in enhancer function, there is no experimental evidence in favor of or against this proposition.

To reduce the complexity of the enhancer, we have previously identified a core domain, which we refer to as the minimal enhancer, that has no redundant elements (20). The minimal enhancer contains the μA, μB, and μE3 motifs, and mutation of any one of these elements abrogates enhancer activity in B cells. We reasoned that μE3 plays an essential role in this context because there are no other compensatory μE motifs in the fragment. Two interesting features of the minimal enhancer should be noted. First, it is also composed of tissue-restricted (μA and μB) and ubiquitous (μE3) elements like the full enhancer, suggesting that it is a good starting point for the analysis of the μ enhancer. Second, multimerization of single elements from this enhancer does not produce a B-cell-specific transcription activator, suggesting that B-cell specificity of the tripartite enhancer is determined by a combinatorial mechanism.

Analysis of the minimal enhancer has led to the following model. This enhancer can be transactivated in nonlymphoid cells by coexpression of PU.1 and Ets-1 (μB and μA binding proteins, respectively). As observed in B cells, enhancer activity requires the intervening μE3 site to which, presumably, an endogenous protein is recruited in the presence of the transfected ETS proteins (26). Interestingly, a deletion mutant of PU.1 that lacks a previously identified transactivation domain (TD) retains its ability to activate the enhancer, whereas deletion of the TD of Ets-1 is functionally deleterious (5). We have proposed that the ETS domain of PU.1 may be sufficient to activate the enhancer because it serves a structural role that includes DNA bending and direct interactions with Ets-1 (21). A TD is required on the μA binding Ets-1 protein. Furthermore, the Ets-1 TD does not activate when tethered to the μB site, indicating that correct location of the domain on the enhancer is essential for function. Our working hypothesis is that μA and μE3 binding proteins present a composite activation domain to the basal transcription machinery (5).

Despite the insights gained from characterization of the minimal enhancer, a crucial aspect of the overall enhancer organization is still missing; this concerns how multiple E motifs contribute to enhancer activity. We show in this report that μE2 and μE3 elements have distinct functions, that μE2 and μE3 sites synergistically activate transcription, and that the synergy is mediated indirectly via protein binding to the μA element that lies between them. Our studies reveal a hitherto-unrecognized organization of μE motifs of the enhancer and a novel mechanism of “through-protein” cooperation between transcription factors. Notably, we provide evidence indicating that ETS domain proteins may mediate transcriptional synergy between bHLH proteins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids.

The PstI-BamHI fragments (nucleotides 376 to 433) derived from wild-type or mutant (μA−, μE3−, or μB−) enhancers were first subcloned into pSP72 digested with the same enzymes. (Note that the BamHI site in the enhancer was previously introduced by site-directed mutagenesis and shown not to affect enhancer activity.) The nucleotide sequences at mutant sites have been described previously (20). For the μE2 mutation, the sequence was changed from CAGCAGCTGG to CATGCTCTGG, creating an SphI site but destroying a PstI site present in the wild-type enhancer. The SphI-BamHI mutant fragment was subcloned into pSP72 cut with SphI and BamHI. The wild-type and mutant enhancer fragments were isolated as HindIII-Asp718 fragments from the pSP72 subclone, treated with Klenow fragment, and cloned into the Δ56CAT reporter plasmid at the SalI site. Plasmids with dimeric inserts were identified and sequenced to confirm orientation. All reporters contained the enhancer inserts in the B orientation as defined by Nelsen et al. (20). A mammalian expression vector for TFE3 (28) was provided by Kathryn Calame (Columbia University, New York, N.Y.). E47 protein was expressed from pRC.E47, which contains the full-length E47 cDNA cloned in the pRC/CMV vector.

Transfection assays.

S194 cells were grown in RPMI medium supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum, 5% calf serum, and 50 μg each of penicillin and streptomycin per ml. Reporter plasmids (5 μg) were transfected into S194 cells by the DEAE-dextran method (20), and whole-cell extracts were prepared 48 h later by three rounds of freezing and thawing.

COS cells, grown in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium containing 10% newborn bovine serum and the same amounts of antibiotics as described above, were transfected by the calcium phosphate procedure. The amounts of reporter and transactivator plasmids used are indicated in the figure legends. The medium was changed after 16 h, and cells were harvested 48 h after transfection. Whole-cell extracts were prepared by three rounds of freezing and thawing. S194 cell extracts or COS cell extracts (50 μg) were assayed for chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) enzyme level by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (CAT ELISA; Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.).

Expression and purification of recombinant proteins. (i) Ets-1 derivatives.

The full-length Ets-1 protein (26) and Ets-1 Δ167 (5) were expressed as hexahistidine-tagged proteins in pET vectors. For protein expression, the plasmid was transformed into the BL21 bacterial strain. Protein production was induced with 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), and His-tagged protein was purified from bacterial extracts by nickel affinity chromatography as described by the manufacturer (Novagen, Inc.).

(ii) GST.TFE3 and GST.E47.

Bacterial expression vector for GST.TFE3 was provided by Kathryn Calame (Columbia University), and full-length E47 cDNA was cloned into pGEX.2T for expression of the protein. Glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion proteins were purified as described previously (33). Briefly, expression of the fusion protein was induced by IPTG to a final concentration of 0.5 mM for 2.5 to 3 h. The bacteria were collected and resuspended in 6 ml of cold NETN buffer (10 mM Tris-Cl [pH 8.0], 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 0.5% Nonidet P-40). The cell extract was made by sonicating at 0°C. After centrifugation, the supernatant was added to glutathione-agarose beads and incubated for 1 h. The beads were washed three times with 30 ml of NETN, and the absorbed proteins were eluted with elution buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl [pH 8.0], 10 mM reduced glutathione). Proteins were dialyzed against buffer D (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 100 mM KCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, 20% glycerol).

To estimate the purity of the recombinant proteins, Coomassie blue-stained sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels were scanned by using the Adobe Photoshop program. The density of the protein bands was determined with Molecular Analysis software. Purity was defined as the density of the expected protein band compared to the sum of all bands present, expressed as a percentage. Typical purities of the various factors were as follows: E47, 80 to 90%; TFE3, 80%; and Ets-1, 50 to 80%.

DNase I footprinting assays.

The HinfI-DdeI fragment (bp 345 to 518) from the μ enhancer was treated with Klenow fragment and cloned into pSP72 cut with EcoRV. The plasmid was linearized with EcoRI, dephosphorylated, and radiolabeled with [γ-32P]ATP and polynucleotide kinase. After digestion with BglII, the labeled enhancer fragment was purified by electrophoresis through 8% polyacrylamide gels. Fifty-microliter footprinting reaction mixtures contained 15,000 cpm of probe, 100 ng of poly[d(I-C) · d(I-C)], 4% polyvinyl alcohol, 20 μg of bovine serum albumin, and various amounts of bacterial proteins. After incubation, an equal volume of 10 mM MgCl2–5 mM CaCl2 was added, followed by DNase I treatment at a final concentration of 17 μg/ml for 1 min. The reaction was quenched with 20 mM EDTA–1% sodium dodecyl sulfate–0.2 mM NaCl–250 μg of yeast tRNA per ml. The DNA was purified by one extraction with phenol-chloroform (1:1), precipitated, and analyzed by electrophoresis through 8% denaturing polyacrylamide gels containing urea. The gels were dried on 3MM paper and exposed to X-ray film or phosphorimager screens as required.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA).

The wild-type μ enhancer probe was isolated from the pSP72 subclone containing the PstI-BamHI fragment of the enhancer. Binding reaction mixtures (20 μl) contained 20,000 cpm of probe, 100 ng of poly[d(I-C) · d(I-C)], 2 μl of 10× lipage buffer (100 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 0.5 M NaCl, 100 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 10 mM EDTA, and 40% glycerol), and various amounts of recombinant proteins. After 15 min of incubation on ice, the reaction mixtures were electrophoresed through 4% polyacrylamide gels which were visualized by autoradiography.

RESULTS

μE2 function requires an intact μE3 element.

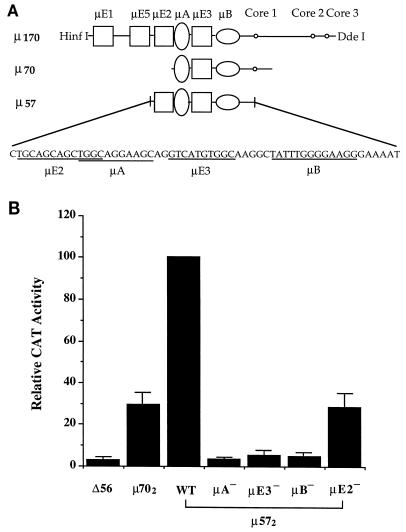

We previously defined a minimal domain of the Ig μ intronic enhancer (μ70) that contains three sequence elements, μA, μE3, and μB (Fig. 1A). To examine how additional E motifs affected the activity of this minimal enhancer, we incorporated the μE2 motif and assayed the transcription activation properties of an enhancer fragment containing μE2, μA, μE3, and μB (μ57 [Fig. 1A]). Note that the new fragment containing four motifs is shorter than the previously defined tripartite enhancer because we have eliminated sequences 3′ of the μB site that have no known function. For these studies a dimer of this fragment was cloned into the vector Δ56 fos CAT, which contains a bacterial CAT gene expressed from the c-fos gene promoter. S194 murine plasma cells were transiently transfected by using DEAE-dextran, and CAT protein expression was assayed by ELISA. Inclusion of the μE2 motif raised the transcription activation potential of the enhancer fragment significantly (three- to fourfold) compared to the activity of the μ70 enhancer (Fig. 1B). Mutation of the μE2 element in this context left an enhancer whose activity was indistinguishable from that of μ70 (Fig. 1B), confirming that sequences present in the μ70 fragment 3′ of μB did not contribute significantly to transcription activation in B cells. Consistent with our previous suggestion of a critical role for the μA and μB elements, mutation of either motif in this context substantially reduced enhancer activity (Fig. 1B). Interestingly, mutation of the μE3 element also abrogated transcriptional activity (Fig. 1B). Because the μ57 μE3− fragment contained an intact μE2 element, we concluded that juxtaposition of μE2, μA, and μB elements did not constitute a functional enhancer, unlike the placement of μA, μE3, and μB elements in the μ70 enhancer. Thus, μE2 and μE3 are not functionally equivalent despite their close sequence similarity. Furthermore, because μE2 function required an intact μE3 element, these observations reveal a previously undetected communication between E motifs of the μ enhancer.

FIG. 1.

Analysis of a four-motif μ enhancer in B cells. (A) Schematic representation of the immunoglobulin μ heavy chain gene enhancer and fragments used in this study. The μ170 enhancer contains four μE motifs (squares). Proteins binding to these elements can be detected in nuclear extracts from lymphoid as well as nonlymphoid cells. μA and μB sites (ovals) bind tissue-restricted ETS domain proteins. The μA site binds Ets-1 and several other ETS proteins such as Fli-1 and Erg-3. The μB site binds the B-cell- and macrophage-restricted protein PU.1. The three small circles indicated as core 1, 2, and 3 have sequence similarity to the simian virus 40 enhancer core sequence. Previous mutational analyses show that both μA and μB are essential for B-cell-specific activity of the μ enhancer, whereas mutation of individual μE motifs partially reduces enhancer activity. Mutation of each core site suggests that they do not contribute to enhancer function. μ70 refers to a previously identified minimal enhancer domain. We refer to this as a tripartite enhancer because the three sites μA, μB, and μE3 are all required for enhancer activity. In this context as well, the core 1 site does not contribute to enhancer activity. The μ70 enhancer has weak transcription activity as a monomer, and we usually assay it as a dimer. μ57 refers to an enhancer fragment that contains four sequence motifs. Its shorter length compared to μ70 is because sequences 3′ of the μB site that are present in μ70 were deleted in this fragment. In this study, μ57 activity was also assayed with the fragment cloned as a dimer. The last line shows the sequence of the μ57 fragment to indicate the positions of the various sequence elements. The μE2 and μE3 elements contain a core CANNTGG sequence, which is characteristic of the binding sites of bHLH transcription factors. The μA and μB elements contain the core GGAA sequence characteristics of ETS domain protein binding sites. However, recent structural and biochemical analyses of the ETS domain indicate that these proteins make several additional contacts 5′ of the core GGAA. Therefore, the underlined region for both sites is shown to extend five nucleotides upstream of the GGAA sequence. In this interpretation the 5′ end of the μA site significantly overlaps the 3′ end of the μE2 site. Enhancer mutations used in this study were as follows: μE2− changes the second GCAG within this site to TGCT, μA− changes the GGA within this site to TCG, μE3− changes the TGG within this site to CAT, and μB− changes the TTT within this site to CCC. (B) Transcriptional activity of the μ57 enhancer in B cells. CAT reporter plasmids containing wild-type or mutated μ57 dimers were transiently transfected into S194 plasma cells by using DEAE-dextran. CAT enzyme activity in whole-cell extracts was determined by an ELISA (Boehringer Mannheim) and is shown normalized to the activity of the wild-type (WT) fragment. The previously analyzed μ70 dimer-containing reporter was used as the positive control, and the enhancerless reporter (Δ56) was used as the negative control. μ57 derivatives mutated at each of the four elements are indicated as μA−, μE3−, μB−, and μE2−. The results shown were obtained by averaging three sets of transfections carried out in duplicate. Error bars represent standard errors.

Inhibitory interactions between μE2 and μA binding proteins.

The ability of μE2 to act as a transcriptional activator only in the presence of μE3 prompted us to more closely examine DNA-protein interactions on this segment of the enhancer, which is shown in greater detail in the sequence in Fig. 1A. Although the binding site of ETS domain proteins contain a GGAA sequence (at the right end of the μA sequence underlined in Fig. 1A) (22), it is clear that ETS proteins make additional contacts several nucleotides 5′ of the GGAA (36). Therefore, the μA bracket is shown extending 5 bp upstream of the core sequence, which makes it overlap with the μE2 element. We used full-length E47 and Ets-1 in in vitro binding assays.

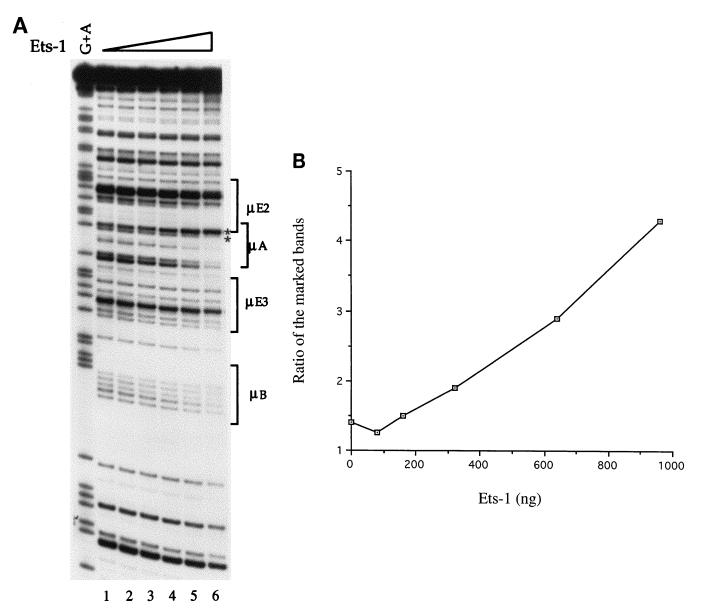

In DNase I footprinting assays, Ets-1 binding was characterized most prominently by effects on two closely migrating bands in the DNase I ladder (Fig. 2A); the upper band increased in intensity with increasing amounts of Ets-1 protein, whereas the lower band decreased in intensity, particularly at the highest levels of Ets-1. Thus, Ets-1 binding to μA resulted in an altered ratio of the intensity of the upper band to that of the lower band. In addition, several other bands within the μA site were also protected against DNase I digestion. Note that fairly high levels of Ets-1 were required to observe a footprint over the μA site, probably because DNA binding by the full-length protein is decreased by two previously characterized inhibitory domains (10, 11, 16, 22, 24). The same pattern of protection and hypersensitivity was observed with the DNA binding ETS domain used at lower protein concentrations (data not shown). However, as noted below, DNA binding by the μE3 binding protein TFE3 also protected bands at the 3′ end of the μA site (lower part of the μA site as shown in Fig. 2A), making these protections unsuitable as a direct measure of Ets-1 binding in the presence of TFE3. Therefore, we have used the altered ratio of the closely migrating bands described above as the unique indicator of Ets-1 binding to the μA element (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Analysis of Ets-1 binding to the μA sites of the enhancer. (A) The noncoding strand of the μ enhancer was radiolabeled and used in DNase I footprinting studies with bacterially expressed proteins. Lane 1, no added proteins; lanes 2 to 6, binding reactions carried out with increasing amounts of His-tagged Ets-1 protein prior to DNase I treatment. A G+A ladder to identify the locations of the various sites is shown preceding lane 1, and the locations of the motifs are indicated to the right of the gel. Ets-1 binding to μA is visualized best by an increased intensity of the upper band compared to the lower band of the doublet that is marked by asterisks to the right of the gel within a bracket labeled μA. The ratio of the intensity of the upper band to that of the lower band is approximately 1.4 in the absence of any added proteins (lane 1). With increasing Ets-1 binding, the intensity of the upper band is increased while that of the lower band is decreased, resulting in an increase in the ratio of the upper to lower bands. Note that there is very little protection of the μB site even at the highest levels of Ets-1. In the experiment shown, 80, 160, 320, 640, and 960 ng of Ets-1 (lanes 2 to 6, respectively) were used. (B) Quantitation of the intensities of the two bands marked by asterisks in panel A. The intensities of the indicated bands were estimated after exposure of the gel shown in panel A to a phosphorimager screen. The ratio of the intensity of the upper band to that of the lower band is plotted against the amount of Ets-1 protein used. The increasing ratio with higher Ets-1 concentrations reflect an increase in the intensity (hypersensitivity to DNase I) of the upper band and a decrease in the intensity (protection against DNase I) of the lower band.

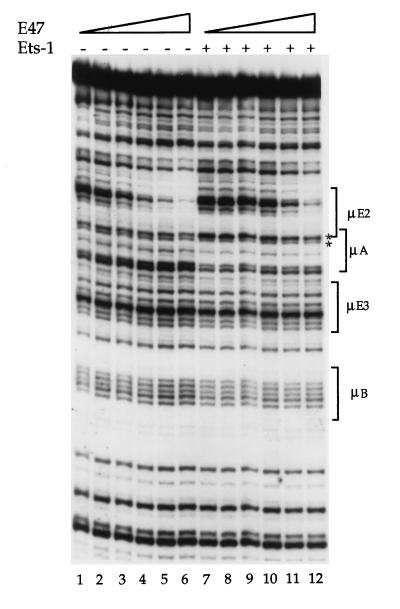

E47 purified from bacteria bound to both μE2 and the μE5 site that lies just above the μE2 site in the gel shown in Fig. 3 (the μE5 site is not marked because it does not feature in the subsequent discussion). When E47 and Ets-1 were present together, we observed a decrease in E47 DNA binding (Fig. 3, lanes 7 to 12). In this experiment, the Ets-1 concentration was fixed at a level that shows binding of this protein to the μA site (Fig. 3, lane 7, as evidenced by the increased ratio of intensities of the asterisk-marked bands), and the E47 concentration was varied over the same range as in lanes 2 to 5. In the presence of Ets-1, E47 protein binding was decreased (Fig. 3, compare lanes 8 to 12 with lanes 2 to 6), indicating that Ets-1 interfered with DNA binding by E47. At high E47 concentrations, when μE2 site protection was evident (for example, Fig. 3, lanes 11 and 12), we noted a decrease in the hypersensitivity of the relevant μA doublet, indicating loss of Ets-1 binding to this site. We infer that full-length E47 and Ets-1 proteins do not bind simultaneously to DNA.

FIG. 3.

Inhibition of E47 and Ets-1 binding to μ enhancer DNA. DNase I footprint analysis of E47 binding to the μ enhancer in the absence or presence of Ets-1 is shown. Lane 1, no protein added; lanes 2 to 6, increasing amounts of GST-E47; lane 7, Ets-1 alone; lanes 8 to 12, a constant amount of Ets-1 (equal to that present in lane 7) with increasing amounts of E47 (equal to those present in lanes 2 to 6, respectively). E47 binding to the μE2 site is visualized by the loss of a major band located in the middle of the bracket marked μE2 and several other bands located both above and below the major band. E47 protein was used at 60, 160, 300, 600 and 1.2 μg in lanes 2 to 6, respectively. For Ets-1-plus-E47 binding, Ets-1 was present at 640 ng and E47 was varied as described above.

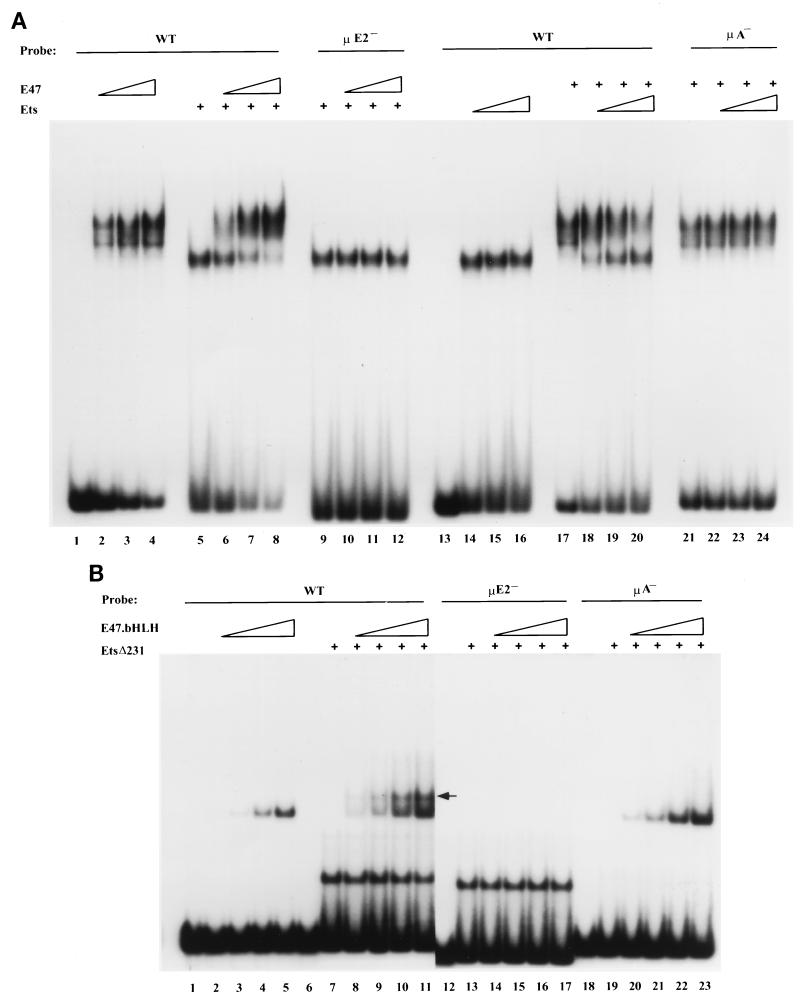

Inhibitory interactions between E47 and Ets-1 were further examined by EMSA. Addition of increasing amounts of full-length E47 resulted in specific binding to the μ enhancer probe (Fig. 4A, lanes 2 to 4). Full-length Ets-1, expressed as a GST fusion protein, bound to the μA site of the enhancer (Fig. 4A, lane 5); this binding was diminished in the presence of increasing amounts of E47 (Fig. 4A, lanes 6 to 8). In contrast, Ets-1 binding to a probe containing a mutated μE2 element was not affected (Fig. 4A, lanes 9 to 12), suggesting that E47 DNA binding was necessary in order to reduce Ets-1–DNA interactions. In a converse experiment, E47 DNA binding (Fig. 4A, lane 17) was reduced by increasing Ets-1 concentrations in the binding reaction mixtures (Fig. 4A, lanes 18 to 20). (Note that the apparent difference in mobility of the E47-DNA complexes in lane 17 compared to lanes 18 to 20 probably represents a gel artifact due to presence of two closely migrating complexes and not double occupancy of the DNA by two relatively large DNA binding proteins. The reduction of E47 binding at high Ets-1 levels is consistent with this interpretation.) To confirm that the Ets-1 preparation did not contain a contaminating activity that inhibited E47 binding, the assays were repeated with a μA mutant probe. Addition of increasing amounts of Ets-1 in this case had no effect on E47 binding to the μE2 site (Fig. 4A, lanes 21 to 24). These observations further support the idea that full-length E47 and Ets-1 proteins mutually inhibit DNA binding by the other.

FIG. 4.

E47 and Ets-1 binding to the μ enhancer. (A) Full-length Ets-1 and E47 were expressed in bacteria as GST fusion proteins and used in EMSAs with wild-type (WT) or mutated μ enhancer probes as indicated. Lane 1, no proteins; lanes 2 to 4, E47 alone (70, 140, and 280 ng, respectively); lane 5, Ets-1 alone (320 ng); lanes 6 to 8, a constant amount of Ets-1 (as in lane 5) with increasing amounts of E47 (as in lanes 2 to 4, respectively); lanes 9 to 12, same proteins as in lanes 5 to 8 with a μE2− probe; lane 13, no protein; lanes 14 to 16, Ets-1 (160, 320, and 640 ng, respectively); lane 17, E47 (140 ng); lanes 18 to 20, a constant amount of E47 (as in lane 17) with increasing amounts of Ets-1 (as in lanes 14 to 16, respectively); lanes 21 to 24, same proteins as in lanes 17 to 20 with a μA− probe. (B) EMSA analysis with DNA binding domains of E47 and Ets-1. Wild-type or mutated μ enhancer probes as indicated were used in binding assays with the bHLH domain of E47 and a truncated (Δ231) Ets-1 derivative. Lane 1, no proteins; lanes 2 to 5, E47 bHLH alone (0.25, 0.5, 1, and 2 ng, respectively); lane 7, EtsΔ231 alone, 400 ng; lanes 8 to 11, a constant amount of EtsΔ231 (as in lane 7) with increasing amounts of E47 bHLH (as in lanes 2 to 5, respectively) (a double-occupancy complex is indicated by the arrow); lanes 12 to 17, same protein conditions as in lanes 6 to 11 with a μE2− probe; lanes 18 to 23, same protein conditions as in lanes 6 to 11 with a μA− probe.

Interestingly, the DNA binding domains of E47 and Ets-1 were able to simultaneously bind to the μE2 and μA motifs, respectively (Fig. 4B). In this experiment the bHLH domain of E47 (Fig. 4B, lanes 2 to 5) and an N-terminal truncation of Ets-1 (Fig. 4B, lane 9) were used in binding assays. In the presence of both proteins, a slower-migrating complex was observed (Fig. 4B, lanes 8 to 11) which represented cobinding of the E47 bHLH and EtsΔ231 to the wild-type probe. This complex was not observed on either μA− or μE2− probes (Fig. 4B, lanes 12 to 23). Thus, inhibition of DNA binding was not due to overlap of the DNA recognition sites of the two factors but rather was likely to be mediated by the non-DNA binding portions of the proteins. These observations suggested an explanation for the inactivity of the enhancer fragment containing only μE2, μA, and μB elements: in this context, enhancer factors may bind to either μE2 or μA sites, but not both, thus precluding the formation of a functional three-protein–DNA complex.

TFE3 enhances Ets-1, but not E47, DNA binding.

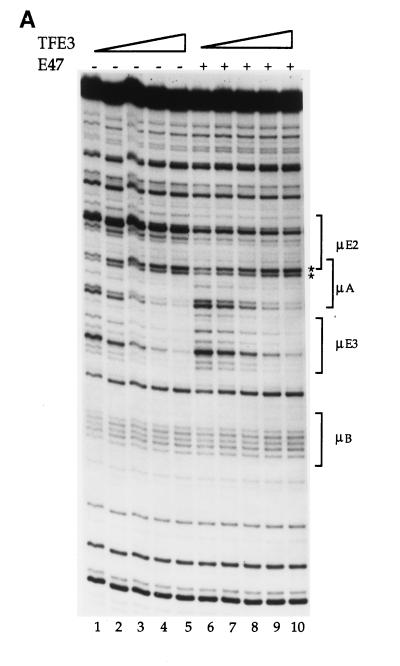

Transfection assays (Fig. 1B) indicated that the μE2 site contributed significantly to enhancer function only in the presence of μE3. To address how μE3 contributed to revealing the μE2 transcriptional potential, we included μE3 binding proteins in the in vitro analyses. Because the μE2 and μE3 sites are separated by 20 nucleotides and therefore lie on the same side of the DNA helix, one mechanism by which μE3 and μE2 may cooperate is by direct interactions between μE2 and μE3 binding proteins. Such interactions may be reflected in cooperative DNA binding. In DNase I footprint assays, TFE3 protein (2, 29) generated a footprint centered over the μE3 element (Fig. 5A, lanes 1 to 5) that extended into the μA element that lies directly 5′ of μE3. In addition to protecting residues within the μA element, TFE3 binding also increased the intensity of the two bands (asterisks) that were discussed above with regard to Ets-1 binding. However, phosphorimager quantification of these bands showed that the ratio of the intensity of the upper band to that of the lower band was unchanged upon TFE3 binding (Fig. 5B). This is in contrast to the observation with Ets-1, where the ratio of this doublet increases with Ets-1 binding (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 5.

Effect of TFE3 on proteins binding to the μE2 and μA elements in vitro. (A) Protein binding to the μE2 and μE3 sites. TFE3 binding to the μE3 site was assayed by DNase I footprinting in the absence or presence of E47. Lane 1, no proteins added; lanes 2 to 5, increasing amounts of TFE3 (100, 200, 400, and 600 ng, respectively); lane 6, 120 ng of E47; lanes 7 to 10, increasing amounts of TFE3 (as in lanes 2 to 5, respectively) in the presence of a constant amount of E47 (as in lane 6). Positions of the enhancer motifs are indicated on the right. Asterisks mark the positions of bands that are affected significantly by Ets-1 binding. Note that the intensity of both bands increases with TFE3 binding, whereas the ratio of the intensities of the bands changes with Ets-1 binding only, as described in the text and shown in panel B. (B) Quantitation of the asterisk-marked bands in the presence of TFE3 alone or TFE3 together with either E47 or Ets-1. Bands were quantitated by phosphorimager analysis, and the ratio of the upper band to the lower band is shown as a function of TFE3 concentration. Despite the increased intensities of these bands in the presence of TFE3 or of TFE3 plus E47, there is no discernible change in the ratio of their intensities. Quantitation of the autoradiograph shown in panel C demonstrates that in the presence of a constant amount of Ets-1, additional TFE3 results in a significant increase in this ratio (TFE3+Ets). The increased ratio at 0 ng of TFE3 in the TFE3+Ets curve is because 160 ng of Ets-1 alone (panel C, lane 1) results in weak but detectable binding to μA. (C) Binding of Ets-1 plus TFE3 in vitro. DNase I footprint assays were carried out with Ets-1 and TFE3 as indicated. Lane 1, Ets-1 alone (160 ng) at a level that shows weak, but detectable, enhancement of the upper asterisk-marked band; lanes 2 to 5, a constant amount of Ets-1 (as in lane 1) together with increasing amounts of TFE3 (100, 200, 400, and 600 ng, respectively).

Cobinding of E47 plus TFE3 was evaluated by using a fixed amount of E47 in the presence of increasing amounts of TFE3 (Fig. 5A, lanes 6 to 10). E47-dependent protection over the μE2 sequence was neither increased nor decreased significantly by the inclusion of TFE3 in the binding, as evident from the intensities of the bands within the μE2 site. Conversely, the presence of E47 did not lead to greater occupancy of μE3 in the range of TFE3 concentrations used in this experiment. At the higher end of the TFE3 titration, we observed simultaneous occupancy of both μE2 and μE3 sites, but there was no evidence for cooperative DNA binding by these two factors. TFE3 binding in the presence of E47 also increased the intensities of the marked bands but did not alter the ratio of the band intensities, as seen with TFE3 alone (Fig. 5B). These observations also strengthen the interpretation that an increased ratio of intensities of these bands is a good measure of Ets-1 binding to the μA element.

In contrast to the results with E47, TFE3 significantly accentuated Ets-1 binding to the μA site. As described above, a high concentration of Ets-1 is required to detect binding of this protein, presumably because of the Ets-1 inhibitory domains. For cobindings with TFE3, we used a fixed, intermediate amount of Ets-1 that did not produce the characteristic alteration in the ratio of the two bands that reflects Ets-1 binding to this site (Fig. 5C, lane 1) and added increasing amounts of TFE3 to the reaction mixtures. We not only observed the expected TFE3 footprint within μE3 but also detected increasing Ets-1 binding as evidenced by the relative increase in the intensity of the upper band of the doublet compared to the lower band (Fig. 5C, lanes 2 to 5). Phosphorimager quantification confirmed that the ratios of bands were changed (Fig. 5B), consistent with increased Ets-1 binding. Because the Ets-1 concentration was held constant in this experiment, we concluded that increasing TFE3 binding to μE3 helped Ets-1 binding to μA.

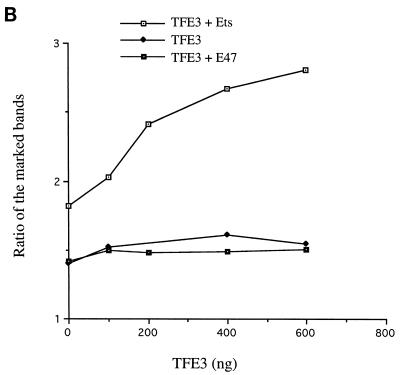

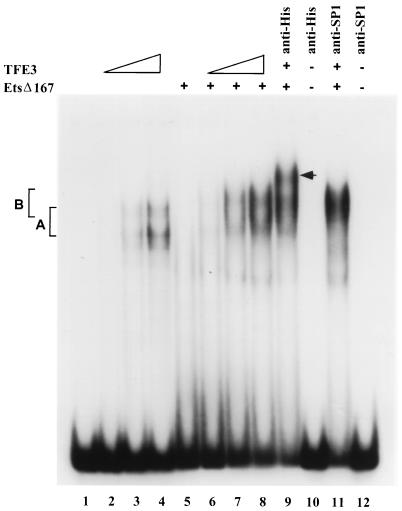

To strengthen this conclusion, we assayed TFE3–Ets-1 interactions by EMSA. TFE3 protein bound to a μ enhancer probe, generating a broad nucleoprotein complex (complex A; Fig. 6, lanes 3 and 4), whereas binding by Ets-1 alone was not detectable in this assay (Fig. 6, lane 5). Coincubation of this fixed amount of Ets-1 with increasing amounts of TFE3 resulted in a strong complex (complex B) that migrated slower than complex A formed with TFE3 alone (Fig. 6, lanes 6 to 8). The slower mobility of complex B suggested that it contained both Ets-1 and TFE3. The presence of Ets-1 in this complex was confirmed by including an antibody recognizing the hexahistidine tag linked to Ets-1. Anti-His antibody did not bind DNA by itself but supershifted complex B (Fig. 6, lanes 9 and 10). As a negative control, an anti-Sp1 antibody did not affect complex B (Fig. 6, lanes 11 and 12). In addition, complex B was not observed when probes mutated at either the μA or μE3 site were used (data not shown). We conclude that Ets-1 DNA binding is greatly enhanced by TFE3. Interestingly, in EMSAs TFE3 binding was also somewhat increased by Ets-1, which was not evident by DNase I footprinting. Further details of Ets-1–TFE3 interactions will be provided elsewhere (34a). Thus, of the three different pairwise combinations of proteins examined so far, Ets-1 and E47 binding appeared to be mutually inhibitory, E47 and TFE3 binding were independent of each other, and TFE3 plus Ets-1 led to enhanced Ets-1 binding.

FIG. 6.

EMSAs of Ets-1 and TFE3 binding to the μ enhancer. A μ enhancer probe, containing μE2-μB (Fig. 1A), was used in in vitro binding assays with increasing amounts of GST.TFE3 (lanes 2 to 4) or EtsΔ167 (lane 5) or a constant amount of EtsΔ167 (equal to that used in lane 5) together with increasing amounts of GST.TFE3 (same range as used in lanes 2 to 4) (lanes 6 to 8, respectively). The complex generated with TFE3 alone is indicated by bracket A, and the complexes generated in the presence of TFE3 plus Ets-1 are marked by bracket B. TFE3-plus-Ets-1 binding reactions were done with 1 μl of anti-His antibody (lane 9) or 1 μl of anti-Sp1 antibody (lane 11). Binding reactions also were done with either anti-His or anti-Sp1 antibody alone (lanes 10 and 12, respectively). A supershifted complex in the presence of anti-His antibody is indicated by the arrow. EtsΔ167 is an N-terminal truncation lacking the first 167 amino acids of Ets-1. The binding reaction mixture contained 200 ng of EtsΔ167 when indicated, and GST.TFE3 was used at 50, 100, and 150 ng (lanes 2 to 4 and lanes 6 to 8, respectively).

Ets-1–TFE3 interactions enhance formation of a three-protein–DNA complex.

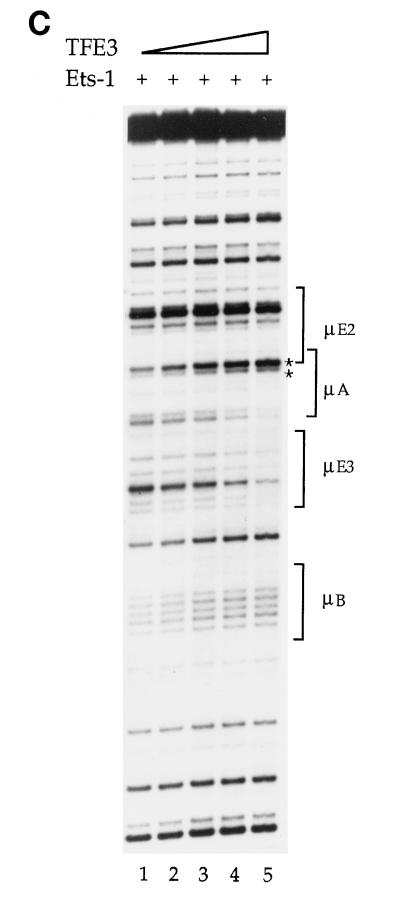

To investigate whether Ets-1–TFE3 interactions affected E47 binding to the μE2 site, we carried out footprinting studies with all three proteins. Increasing amounts of E47 protein were added to binding reaction mixtures that contained no other proteins (Fig. 7, lanes 1 to 5), only Ets-1 (Fig. 7, lanes 6 to 10), or both Ets-1 and TFE3 (Fig. 7, lanes 11 to 15). Because the goal was to examine the effect on E47 when Ets-1 was bound either alone or together with TFE3 to the DNA, we used conditions that gave comparable Ets-1 DNA binding in the two-protein (Fig. 7, lanes 6 to 10) or three-protein (lanes 11 to 15) analyses. Specifically, the ratio of the upper to lower asterisk-marked bands, which indicates Ets-1 DNA binding, was kept the same in the two sets. (Note that this ratio actually underestimates the extent of Ets-1 binding in the third set, because TFE3 increases the intensity of the lower band, thus decreasing the ratio.)

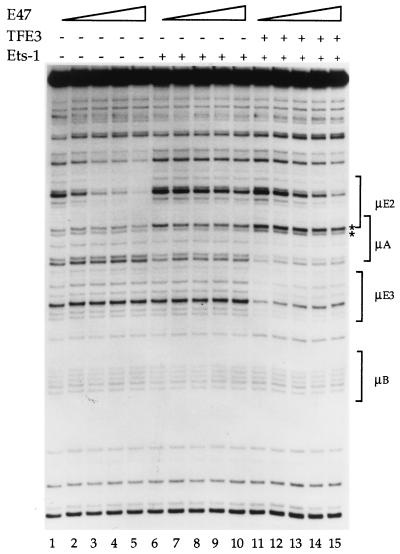

FIG. 7.

Binding of Ets-1, TFE3, and E47 to the μ enhancer. Increasing amounts of E47 protein were used in binding reactions containing no other proteins (lanes 1 to 5), a constant amount of Ets-1 (lanes 6 to 10) or a constant amount of Ets-1 plus TFE3 (lanes 10 to 15). Lane 1, no proteins added; lanes 2 to 5, increasing amounts of E47 alone (60, 120, 180, and 270 ng, respectively); lane 6, Ets-1 alone (480 ng); lanes 7 to 10; increasing amounts of E47 (as in lanes 2 to 5, respectively) in the presence of a constant amount of Ets-1 (as in lane 6); lane 11, Ets-1 (140 ng) plus TFE3 (400 ng); lanes 12 to 15 Ets-1 plus TFE3 (as in lane 11) with increasing amounts of E47 (as in lanes 2 to 5, respectively). Different concentrations of Ets-1 were used in lanes 6 to 10 than in lanes 11 to 15 to maintain similar levels of Ets-1 binding in the two sets, as estimated by the ratio of the upper to lower band of the asterisk-marked doublet. Phosphorimager quantification showed an insignificant change of the doublet ratio between lanes 11 to 15, indicating that Ets-1 occupancy was not reduced with increased E47 concentration.

Addition of increasing amounts of E47 generated a characteristic footprint over the μE2 site (Fig. 7, lanes 2 to 5). Ets-1 binding was revealed as increased intensity of the upper of the two asterisk-marked bands (Fig. 7, lane 6). The amount of Ets-1 used here resulted in partial filling of the μA site, reflected by the small change in the ratio of asterisk-marked bands (greater occupancy would induce a larger change in the ratio of these bands [see, for example, Fig. 2A, lane 6]). As discussed above, E47 binding to μE2 was substantially reduced in the presence of Ets-1 (Fig. 7, lanes 6 to 10) as evidenced by only marginal decreases in the bands within the μE2 bracket. However, E47 binding was significantly enhanced (Fig. 7, lanes 12 to 15) when Ets-1 binding was stabilized by TFE3 (Fig. 7, lane 11). Phosphorimager quantification of the marked μA bands in lanes 11 to 15 showed no change in the ratio of the intensities of this doublet, indicating that Ets-1 binding was not altered even at the highest levels of E47 added (data not shown). Although the extent of E47 binding was not the same as that seen in the absence of Ets-1, quantitation of μE2 occupancy in the presence of Ets-1 plus TFE3 showed approximately 70 to 80% restoration of E47 binding compared to that with E47 alone, especially at higher concentrations of E47 (for example, compare lanes 3 to 5 to lane 1 and lanes 13 to 15 to lane 11; phosphorimager data not shown). We infer that the interference of DNA binding between E47 and Ets-1 is significantly reduced in the presence of TFE3. We propose that conformational changes in Ets-1 induced by its interaction with TFE3 may increase E47 DNA binding in vitro. These observations suggest an explanation for the result that μE2 contributes to enhancer activity only when the μE3 site is intact.

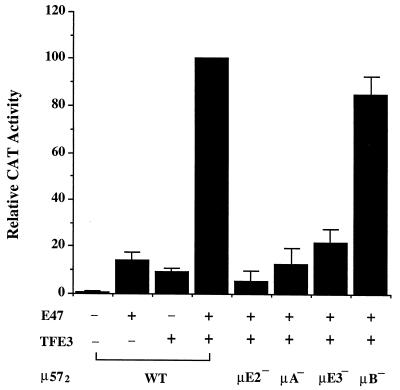

Transcriptional synergy between E47 and TFE3 requires the intervening μA site.

Our transfection studies with B cells indicated that endogenous μE2 and μE3 binding proteins synergistically activated transcription in the context of the μ57 enhancer. For the in vitro analyses described in the preceding section, we used E47 and TFE3 as μE2 and μE3 binding proteins, respectively. To test whether these proteins could activate the μ enhancer in nonlymphoid cells, we carried out the following transfection studies. The μ57-containing reporter plasmid was cotransfected into COS cells together with vectors directing expression of E47 and TFE3. Expression of either E47 or TFE3 alone activated transcription of the reporter weakly (Fig. 8, first three bars). Both of these genes have been previously shown to contain transcription activation domains, which are presumably responsible for this activity (2, 25). However, coexpression of both E47 and TFE3 resulted in synergistic activation of the reporter plasmid (Fig. 8). We also noted that the activity in the presence of both proteins was approximately fourfold greater than the sum of the activity due to each gene product. The extent of synergy is reminiscent of the three- to fourfold-greater activity of the μ57 enhancer (which contains μE2 and μE3) compared to the μ70 enhancer (which contains only μE3) in B cells. These results provide direct evidence for functional synergy between the bHLH (E47) and bHLH zipper (TFE3) families of transcription factors, which has also been noted by others (3).

FIG. 8.

Transcription activation by E47 and TFE3. A μ57 dimer reporter plasmid (2 μg) was transfected into COS cells by using calcium phosphate together with expression vectors for E47 (1 μg) and TFE3 (1 μg) as indicated below the graph. At 48 h after transfection, CAT expression was assayed by ELISA. In transfections containing only one of the transactivator plasmids, the total DNA was kept constant by the addition of pEVRF expression vector containing no insert. The roles of individual elements in transcriptional activation were assayed by using mutated μ57 reporter plasmids (indicated as μE2−, μA−, μE3−, and μB−). The results shown are the averages of three experiments carried out in duplicate, normalized to the expression of the wild-type (WT) plasmid in the presence of both transactivators. Error bars represent the standard error between measurements.

As expected, transcriptional activity in the presence of E47 and TFE3 was dependent on the μE2 and μE3 sites (Fig. 8, bars μE2− and μE3−). Furthermore, there was no effect of mutating the μB site that lies 3′ of μE3, presumably because the μE2 and μE3 binding proteins are being provided in trans. However, we were surprised to find that a mutation in the intervening μA element also abolished transcriptional synergy (Fig. 8, bar μA−). In vitro studies ruled out the trivial possibility that the μA− mutation affected binding of either E47 or TFE3 to its respective site (data not shown). We conclude that binding of an endogenous factor to the μA site is necessary for transcriptional synergy between E47 and TFE3. Although we have no direct evidence, the sequence of the μA element suggests that the endogenous COS cell protein is likely to be a member of the ETS family. Lack of transcriptional activity by E47 and TFE3 in the absence of the μA site may be because the two proteins do not bind their respective sites in vivo without a μA binding protein or because the μA binding protein promotes transcription activation by the combination of E47 and TFE3. Based on the observed transcription activation by each protein alone, as well as in vitro data indicating that E47 and TFE3 can bind simultaneously to DNA (Fig. 5), we think it unlikely that these proteins cannot find their respective sites in the μA− reporter. Rather, we favor a model where interaction between an ETS protein and TFE3 (such as that exemplified in Fig. 6) enhances the presentation of a combined E47-TFE3 TD to the basal transcription machinery.

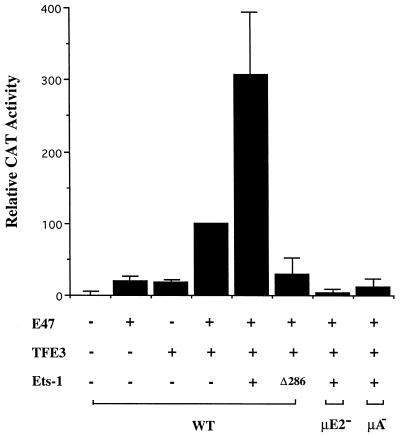

Ets-1 enhances transcriptional synergy between E47 and TFE3.

Next, we directly tested whether the μA binding protein, Ets-1, could mediate transcriptional synergy between μE2 and μE3. The effect of Ets-1 protein on transcriptional activation by E47 and TFE3 was examined in COS cell transfection assays. As described above, E47 plus TFE3 transactivated the wild-type μ57 enhancer (Fig. 9, first four bars). This activity was significantly increased by coexpression of Ets-1 (Fig. 9, fifth bar). Enhancers carrying mutated μE2 or μA motifs were inactive under these conditions, indicating that the exogenously expressed Ets-1 raised E47- and TFE3-dependent transcriptional synergy.

FIG. 9.

Ets-1 mediates E47-TFE3 transcriptional synergy. Reporter DNAs (2 μg) were cotransfected into COS cells with expression vectors for E47, TFE3, and Ets-1 as indicated, and CAT enzyme activity was assayed by ELISA 48 h after transfection. The data shown are normalized to the activity of the wild-type μ57 reporter in the presence of TFE3 and E47, which is assigned the value 100. μE2− and μA− refer to reporters containing mutated μE2 and μA motifs, respectively, in the context of the μ57 enhancer fragment (see also the legend to Fig. 1). Δ286 refers to an expression vector encoding an N-terminal truncation mutant of Ets-1 that contains the DNA binding ETS domain and extends to the C terminus (5). The total amount of DNA in each transfection was kept constant at 5 μg by using the empty expression vector pEVRF-0. All assays used 1 μg each of E47, TFE3, and Ets-1 expression vectors. The results shown are based on two transfection experiments carried out in duplicate. Error bars represent standard errors.

Finally, to determine whether the DNA binding ETS domain of Ets-1 was sufficient for this activity, we expressed a deletion mutant of Ets-1 which lacks the N-terminal 286 amino acids, EtsΔ286. In the presence of EtsΔ286, transcriptional activity of the wild-type μ57 reporter was even lower than that observed with only TFE3 and E47 (Fig. 9, sixth bar). We interpret these results to indicate that the first 286 amino acids of Ets-1, which contain a previously identified transcription activation domain, are required to enhance TFE3-E47 synergy. Reduced transcriptional activity in the presence of EtsΔ286 compared to that in the presence of TFE3 and E47 may be explained by competition between the functionally inactive exogenously expressed protein and the endogenous protein binding to the μA site. We conclude that full-length Ets-1, but not its DNA binding domain, can mediate transcriptional synergy between E47 and TFE3.

DISCUSSION

Functional differences between μE elements.

In this work, we studied the mechanisms by which bHLH proteins and ETS proteins cooperate to activate the Ig μ enhancer. First we showed that inclusion of an additional μE element, μE2, in the previously defined tripartite enhancer significantly increased enhancer activity in B cells. These results indicate that sequential addition of μE3 and μE2 raises the transcriptional activity of the μA-μB combination, which by itself is not significantly active. Unlike μE3, which together with μA and μB produces a transcriptional activator, a DNA fragment containing μE2, μA, and μB did not activate transcription. Thus, μE2 and μE3 appear to have distinct functions in the μ enhancer. Furthermore, the μE2 element contributes to transcription activation only when the μE3 element is intact, indicating functional synergy between these two μE elements.

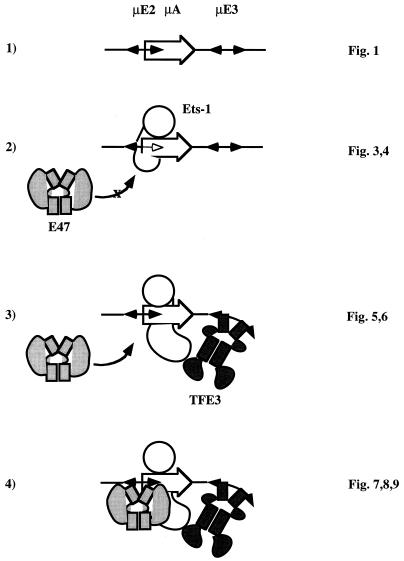

These observations raised two questions: why was the μE2-μA-μB fragment not active, and how did μE3 uncover the transcription activation potential of μE2? In vitro analyses of DNA-protein interactions provided possible explanations for these findings. We show that the μE2 binding protein, E47, and the μA binding protein, Ets-1, do not bind simultaneously to the μ enhancer in vitro. This is depicted schematically in Fig. 10 (line 2). Although Ets-1 is shown bound to DNA and thereby preventing access of E47, it is equally likely that DNA-bound E47 may prevent Ets-1 binding in vivo. It is also possible that in the absence of stabilization from a μE3-bound protein, Ets-1 cannot bind efficiently to the μA element. Regardless of whether it is because of the competition between the μE2 and μA sites or because Ets-1 cannot bind in the absence of TFE3, this situation reduces a putative three-component enhancer to a two-component enhancer. Therefore, only ternary protein-DNA complexes can be formed on a μE3− enhancer, with proteins bound either to the μA and μB sites or to the μB and μE2 sites. Based on our earlier studies, it is unlikely that such a two-component enhancer would be active in B cells (20, 26).

FIG. 10.

A model for through-protein cooperation between E motifs of the μ enhancer. Line 1, region of interest within the μ enhancer. The double-headed arrows represent the partially palindromic (CANNTG) μE2 and μE3 motifs, which bind bHLH proteins E47 and TFE3, respectively. The single-headed arrow represents the nonpalindromic μA site that binds ETS domain proteins. Partial overlap between the μE2 and μA sites (see Fig. 1A for nucleotide sequence) is indicated by the μE2 arrow lying partially within the μA arrow. Line 2, mutual inhibition of DNA binding by E47 and Ets-1. For simplicity, Ets-1 is shown bound to DNA (the circle represents the DNA binding ETS domain) with other parts of Ets-1 obstructing access to the μE2 site. However, our data does not directly address the mechanism by which these proteins are mutually inhibitory. Therefore, the indicated steric inhibition model should be viewed only as one of several possibilities. Line 3, TFE3 binding to the μE3 element enhances DNA binding by Ets-1. This is probably mediated by contacts between TFE3 and Ets-1 that relieve intramolecular inhibition of Ets-1 DNA binding. An altered Ets-1 conformation is indicated by the changed position of the non-DNA binding domains of Ets-1, which are shown directly interacting with TFE3. Line 4, Stabilization of Ets-1 binding by TFE3 reduces the inhibitory effect of Ets-1, allowing E47 to bind and generate a three-protein–DNA complex. One possibility is that reconfiguration of Ets-1 by interaction with TFE3 exposes the μE2 half-site shown to be blocked in line 2. Furthermore, transfection studies with COS cells indicate that coexpression of E47 and TFE3 is not sufficient for efficient transcriptional activation; maximal transcription activation requires, in addition, an ETS protein bound between the two bHLH factors. Based on these observations, we propose that functional synergy between μE2 and μE3 is the result of two interactions, both of which involve an intermediate ETS protein. First, the mutual inhibition of DNA binding by Ets-1–E47 interaction is relieved by TFE3, allowing all three proteins to bind the enhancer. Second, the ETS protein couples the transcription activation potential of the DNA-bound bHLH factors.

μE3-dependent μE2 activity.

The possible role of μE3 in recruiting the transcription activation potential of μE2 was also inferred from in vitro DNA binding assays. We found that in the presence of the μE3 binding protein, TFE3, Ets-1 binding to μA was significantly enhanced. Furthermore, under these conditions E47–Ets-1 interference was markedly reduced, resulting in increased occupancy of the μE2 site. Because the DNA binding domains of E47 and Ets-1 can bind simultaneously to the μE2 and μA sites, we concluded that the mutual inhibition of binding by the full-length proteins must be due to other domains in these proteins. In principle, this inhibition can be removed if conformational alterations in either protein realign these domains so that they no longer obstruct DNA binding. We propose that Ets-1–TFE3 interaction alters the conformation of Ets-1 so that it no longer inhibits E47 binding to the μE2 site (shown schematically in Fig. 10, lines 3 and 4). Moreover, Ets-1–TFE3 interactions may also stabilize Ets-1 DNA binding, thereby bringing Ets-1 into a complex where it plays a critical role in transcription activation, as described below. In these models, enhancement of E47 transcriptional activation potential by TFE3 is mediated indirectly via Ets-1 protein that binds between them and not by direct interactions between TFE3 and E47. The mechanism of μE box cooperation on the μ enhancer is therefore distinct from the cooperative interactions between factors forming multiprotein assemblies on the beta interferon promoter (34) or the T-cell receptor α-chain gene enhancer (9).

Our model is further substantiated by the following observations. DNA binding by Ets-1 is decreased by two inhibitory domains located on either side of the ETS domain (10, 11, 16, 22, 24). Increased binding of Ets-1 to the μA site in the presence of TFE3 may be attributed to neutralization of one or both inhibitory domains by direct Ets-1–TFE3 interactions. We have obtained evidence for such interactions by using a GST pull-down assay. Dissection of these proteins by using such an assay showed that the inhibitory domain of Ets-1 located N terminal to the DNA binding domain contributed significantly to interaction with the bHLH zipper domain of TFE3 (34a). Further evidence for Ets-1–TFE3 interactions was obtained from a partial proteolysis assay (26). We found that a trypsin cleavage site in the N-terminal domain of Ets-1 was protected from proteolysis in the presence of TFE3 but not other proteins, including transcription factors such as the p50 subunit of NF-κB. Furthermore, the protection was significantly enhanced in the presence of μ enhancer DNA. We interpret these results to indicate that association of Ets-1 and TFE3 leads to a conformational change in Ets-1 in an N-terminal domain. We propose that such changes, in addition to increasing the affinity of Ets-1 for DNA, may make the μE2 site more accessible to E47.

ETS protein-dependent transcriptional synergy between bHLH proteins.

We anticipated that the collaboration between μE2 and μE3 would be explained by the facilitation of E47 DNA binding via TFE3–Ets-1 interactions as described above. Presumably, when both proteins were bound to the DNA, their TDs would be brought into close proximity and thereby enhance transcription. However, when we directly assayed the combined transactivation potential of E47 and TFE3 by cotransfection, synergistic transactivation was observed only when the intervening μA site was intact. Thus, transcriptional synergy between E47 and TFE3 requires an intermediate protein. One possibility that cannot be ruled out unequivocally is that the two proteins cannot bind to the enhancer under these conditions. However, we consider this to be unlikely because each protein individually transactivated the reporter at low levels, indicating that each could access its site on the reporter plasmid. Taken together with the observation that both proteins bound simultaneously to their respective sites in vitro, it is likely that both sites are also occupied in the transfection experiment. We infer that the transcription activation domains of these factors cannot cooperate unless the μA element is also occupied. Transfection assays with Ets-1 provided direct evidence that ETS proteins can enhance the transcription activation potential of bHLH proteins such as TFE3 and E47. Furthermore, the DNA binding domain of Ets-1 was not sufficient for this purpose, implicating a role for the transcription activation domain of Ets-1 in the three-protein complex, as discussed below. These observations provide a novel example of “through-protein” cooperation between the μE2 and μE3 elements of the μ enhancer.

Two models of how Ets-1 (or an Ets-1-like protein) may enhance the transcription activation potential of E47 and TFE3 can be considered. First, the TD of Ets-1 may directly participate with E47 and TFE3 TDs to generate a composite TD. For example, a TD in Ets-1 may associate with the TFE3 and E47 TDs to generate a three-subunit TD that is presented to the basal transcription machinery. It is also possible that a TD in Ets-1 may independently associate with the TDs in E47 and TFE3, resulting in two two-subunit TDs. In these models, the composite domains would be better transcriptional activators than the individual domains of the μ enhancer binding proteins. Alternatively, Ets-1–TFE3 interactions may alter the TFE3 conformation so that its TD is able to interact with the TD in E47. Although our present study does not distinguish between these models, it highlights an unusual form of functional synergy in which the transcription activation potentials of two bHLH proteins are coupled by a third protein belonging to the ETS family.

A model for μ enhancer function.

These observations can be incorporated into a model for μ enhancer function as follows. The binding and cotransfection assays discussed above deal with the possible interactions between the μE2, μA, and μE3 sites. However, enhancer activity in B cells also requires the μB site (Fig. 1), which is located 3′ of the μE3 element. Our earlier studies, in particular those altering the spacing between μA and μB sites, have suggested that these two elements act as a unit (21). Furthermore, the ETS domain of PU.1 is sufficient to synergize with Ets-1 to activate the three-component μA-μE3-μB enhancer in nonlymphoid cells (5). Based on these observations, we have proposed that the ETS domain of PU.1 serves two functions: first, it may facilitate formation of a functional nucleoprotein complex by bending the DNA, and, second, direct interactions with Ets-1 may alter the structure of either Ets-1 or PU.1 (or both) and thereby affect enhancer activity. We suggest that PU.1 binding (via the mechanisms discussed above) is necessary to allow the formation of a transcription activation complex at the μE2, μA, and μE3 sites but that it does not participate directly in transcription activation. Stabilization of Ets-1 binding (to μA) by TFE3 (bound to μE3) is a critical aspect of the subsequent assembly. It is reflected in the transcriptional activity of the μA-μE3-μB enhancer as well as in rendering the μE2 site accessible to appropriate bHLH proteins. In the tripartite (μA-μE3-μB) enhancer, Ets-1 bound at the μA site provides a transcription activation domain which works together with an activation domain in TFE3. An additional, unexpected role for the μA binding protein was revealed in the studies presented here. Transcriptional synergy between μE2 and μE3 required an intact μA site, suggesting that ETS proteins mediate functional interactions between E47 (bHLH) and TFE3 (bHLH zipper) proteins bound to these sites. In addition to describing a novel mechanism of transcription activation by ETS proteins, these observations provide the first insights into how tissue-restricted elements, such as the μA motif, combine with ubiquitous elements, such as the μE2 and μE3 motifs, to generate tissue-specific enhancers.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Michael Rosbash and members of the laboratory for helpful discussions and Elaine Ames for preparation of the manuscript.

W.D. is a recipient of a Gillette Graduate Fellowship. This work was supported by PHS grant GM38925 to R.S.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams J M, Harris A W, Pinkert C A, Corcoran L M, Alexander W S, Cory S, Palmiter R D, Brinster R L. The c-myc oncogene driven by immunoglobulin enhancers induces lymphoid malignancy in transgenic mice. Nature. 1985;318:533–538. doi: 10.1038/318533a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Artandi S E, Cooper C, Shrivastava A, Calame K. The basic helix-loop-helix-zipper domain of TFE3 mediates enhancer-promoter interaction. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:7704–7716. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.12.7704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carter R S, Ordentlich P, Kadesch T. Selective utilization of basic helix-loop-helix-leucine zipper proteins at the immunoglobulin heavy-chain enhancer. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:18–23. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.1.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen J, Young F, Bottaro A, Stewart V, Smith R K, Alt F W. Mutations of the intronic IgH enhancer and its flanking sequences differentially affect accessibility of the JH locus. EMBO J. 1993;12:4635–4645. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06152.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Erman B, Sen R. Context dependent transactivation domains activate the immunoglobulin μ heavy chain gene enhancer. EMBO J. 1996;17:4665–4675. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ernst P, Smale S T. Combinatorial regulation of transcription. II. The immunoglobulin μ heavy chain gene. Immunity. 1995;2:427–438. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90024-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fernex C, Capone M, Ferrier P. The V(D)J recombinational and transcriptional activities of the immunoglobulin heavy-chain intronic enhancer can be mediated through distinct protein-binding sites in a transgenic substrate. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:3217–3226. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.6.3217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Genetta T, Ruezinsky D, Kadesch T. Displacement of an E-box-binding repressor by basic helix-loop-helix proteins: implications for B-cell specificity of the immunoglobulin heavy-chain enhancer. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:6153–6163. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.9.6153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giese K, Kingsley C, Kirschner J R, Grosschedl R. Assembly and function of a TCRα enhancer complex is dependent on LEF-1-induced DNA bending and multiple protein-protein interactions. Genes Dev. 1995;9:995–1008. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.8.995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hagman J, Grosschedl R. An inhibitory carboxyl-terminal domain in Ets-1 and Ets-2 mediates differential binding of ETS family factors to promoter sequences of the mb-1 gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:8889–8893. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.19.8889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jonsen M D, Peteson J M, Xu Q, Graves B J. Characterization of the cooperative function of inhibitory sequences in Ets-1. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:2065–2073. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.5.2065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kadesch T. Helix-loop-helix proteins in the regulation of immunoglobulin gene transcription. Immunol Today. 1992;13:31–36. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(92)90201-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kiledjian M, Su L, Kadesch T. Identification and characterization of two functional domains within the murine heavy-chain enhancer. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:145–152. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.1.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Langdon W Y, Harris A W, Cory S, Adams J M. The c-myc oncogene perturbs B lymphocyte development in Eμ-myc transgenic mice. Cell. 1986;47:11–18. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90361-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lenardo M, Pierce J W, Baltimore D. Protein-binding sites in Ig gene enhancers determine transcriptional activity and inducibility. Science. 1987;236:1573–1577. doi: 10.1126/science.3109035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lim F, Kraut N, Frampton J, Graf T. DNA binding by c-Ets-1, but not v-Ets, is repressed by an intramolecular mechanism. EMBO J. 1992;11:643–652. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05096.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murre C, McCaw P S, Baltimore D. A new DNA binding and dimerization motif in immunoglobulin enhancer binding, daughterless, MyoD, and myc proteins. Cell. 1989;56:777–783. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90682-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nelsen B, Hellman L, Sen R. The NF-κB-binding site mediates phorbol ester-inducible transcription in non-lymphoid cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:3526–3531. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.8.3526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nelsen B, Sen R. Regulation of immunoglobulin gene transcription. Int Rev Cytol. 1992;133:121–149. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)61859-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nelsen B, Tian G, Erman B, Gregoire J, Maki R, Graves B, Sen R. Regulation of lymphoid-specific immunoglobulin μ heavy chain gene enhancer by ETS-domain proteins. Science. 1993;261:82–86. doi: 10.1126/science.8316859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nikolajczyk B, Nelsen B, Sen R. Precise alignment of sites required for μ enhancer activation in B cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:4544–4554. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.8.4544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nye J A, Petersen J, Gunther C V, Jonsen M D, Graves B J. Interaction of murine Ets-1 with GGA-binding sites establishes the ETS domain as a new DNA-binding motif. Genes Dev. 1992;6:975–990. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.6.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perez-Mutul M, Macchi, Wasylyk B. Mutation analysis of the contribution of sequence motifs within the IgH enhancer to tissue specific transcriptional activation. Nuc Acids Res. 1988;16:6085–6090. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.13.6085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peterson J M, Skalicky J J, Donaldson L W, Mcintosh L P, Alber T, Graves B. Modulation of transcription factor Ets-1 DNA binding: DNA-induced unfolding of an α-helix. Science. 1995;269:1866–1869. doi: 10.1126/science.7569926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quong M W, Massari M E, Zwart R, Murre C. A new transcriptional-activation motif restricted to a class of helix-loop-helix proteins is functionally conserved in both yeast and mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:792–800. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.2.792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rao E, Dang W, Tian G, Sen R. A three protein-DNA complex on a B cell-specific domain of the immunoglobulin μ heavy chain gene enhancer. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:6722–6732. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.10.6722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reik W, Williams G, Barton S, Norris M, Neuberger M, Surani M A. Provision of the immunoglobulin heavy chain enhancer downstream of a test gene is sufficient to confer lymphoid-specific expression in transgenic mice. Eur J Immunol. 1987;17:465–469. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830170405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roman C, Cohn L, Calame K. A dominant negative form of transcription factor mTFE3 created by differential splicing. Science. 1991;254:94–97. doi: 10.1126/science.1840705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roman C, Matera A G, Cooper C, Artandi S, Blain S, Ward D C, Calame K. mTFE3, an X-linked transcriptional activator containing basic helix-loop-helix and zipper domains, utilizes the zipper to stabilize both DNA binding and multimerization. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:817–827. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.2.817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ruezinsky D, Beckmann H, Kadesch T. Modulation of the IgH enhancer’s cell type specificity through a genetic switch. Genes Dev. 1991;5:29–37. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Serwe M, Sablitzky F. V(D)J recombination in B cells is impaired but not blocked by targeted deletion of the immunoglobulin heavy chain intron enhancer. EMBO J. 1993;12:2321–2327. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05886.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shen L, Lieberman S, Eckhardt L A. The octamer/μE4 region of the immunoglobulin heavy-chain enhancer mediates gene repression in myeloma X T-lymphoma hybrids. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:3530–3540. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.6.3530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith D B, Johnson K S. Single step purification of polypeptides expressed in Escherichia coli as fusions with glutathione S-transferase. Gene. 1988;67:31–40. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thanos D, Maniatis T. Virus induction of human IFNF gene expression requires the assembly of an enhanceosome. Cell. 1995;83:1091–1100. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90136-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34a.Tian, G., B. Erman, H. Ishii, and R. Sen. Transcriptional activation by ETS and bHLH-zip proteins. Submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Tsao B T, Peterson C L, Calame K C. In vivo functional analysis of in vitro protein binding site in the immunoglobulin heavy chain enhancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:3239–3253. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.8.3239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Werner M H, Clore G M, Fisher C L, Fisher R J, Trinh L, Shiloach J, Gronenborn A M. The solution structure of the human ETS1-DNA complex reveals a novel mode of binding and true side chain interaction. Cell. 1995;83:761–777. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90189-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]