Abstract

Barriers to safe walking may prevent people from being physically active, and previous reports have identified differences in barriers to safe walking across racial and ethnic groups. The purpose of this research was to determine the role demographic characteristics play on racial/ethnic differences in perceived barriers to safe walking and determine if racial/ethnic differences vary by urban/rural residence and Census region. Participants in the 2015 National Health Interview Survey Cancer Control Supplement (n=31,433 adults ≥18 years) reported perceived barriers to safe walking (traffic, crime, and animals) and demographic characteristics. Urban/rural residence and Census region were based on home addresses. We calculated adjusted prevalence of barriers by race/ethnicity using logistic regression; geographic differences in barriers across racial/ethnic groups were examined via interaction terms. After adjustment for demographic characteristics, non-Hispanic blacks (blacks) and Hispanics reported crime and animals as barriers more frequently than non-Hispanic whites (whites) (crime: blacks, 22.2%; Hispanics, 16.7%; whites, 9.0%; animals: blacks, 18.0%; Hispanics, 12.4%; whites, 8.5%). Racial/ethnic differences in perceived crime as a barrier were more pronounced in the Northeast and Midwest than in the South and West. Urban-dwelling blacks (all regions) and Hispanics (Midwest and South) reported animals as barriers more frequently than whites. Racial/ethnic differences in perceived barriers to safe walking remained after adjusting for demographic characteristics and varied by geographic location. Addressing perceived crime and animals as barriers to walking could help reduce racial/ethnic differences in physical activity, and several barriers may need to be assessed to account for geographic variation.

Keywords: epidemiology, walking, population health, racial/ethnic disparities

Introduction

Walking is a common, accessible activity that can help people start and maintain an active lifestyle (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services., 2015). Barriers to walking and other physical activities can include concerns for personal safety (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services., 2015) related to traffic, crime, and animals. Favorable perceptions of neighborhood crime, traffic, and general safety have been directly associated with walking in cross-sectional and longitudinal studies (Evenson et al., 2012; Foster et al., 2016; Mason et al., 2013), but the strength and significance of the associations varied for transportation and leisure walking. Other studies have shown no or mixed associations between perceived safety and walking, but differences in study design, measurement, and variable definitions may underlie these inconsistencies (Kerr et al., 2015; Saelens and Handy, 2008).

Barriers to safe walking may contribute to racial/ethnic differences in physical activity (National Center for Health Statistics., 2016) and walking (Ussery et al., 2017). Concerns about the safety of walking are different across racial and ethnic groups. For example, in several studies, black participants (compared to white participants) and Hispanic participants (compared to non-Hispanic participants) have reported more barriers to safe walking, including animals, crime, and general safety concerns (Lovasi et al., 2009; Paul et al., 2016; Schroeder and Wilbur, 2013). Further, differences in perceived safety may have widened from 2000 to 2010, with decreases in neighborhoods with a greater than average proportion of black residents and increases in neighborhoods with a smaller than average proportion of black residents, after controlling for socioeconomic and demographic characteristics (Kaiser et al., 2016). Reducing racial/ethnic health disparities is a national public health priority (United States Department of Health and Human Services, 2011), and addressing differences in physical activity and walking is an important strategy toward achieving health equity (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017). However, at the national level, it is unclear whether additional demographic characteristics, such as sex, age, and education level influence racial/ethnic differences in perceived barriers to safe walking. Understanding these complex relations could inform strategies to meet national goals for racial/ethnic health equity (United States Department of Health and Human Services, 2011).

Geography may also be an important influence on racial/ethnic differences in safety concerns. There are established differences in racial/ethnic composition across Census regions and in urban and rural areas (United States Census Bureau, 2010), and factors related to walking safety (e.g., speed limits, sidewalks, and unmaintained lots) vary from place to place (Adams et al., 2014; Kerr et al., 2016; Thornton et al., 2016). However, it is not known if racial/ethnic differences in barriers to safe walking differ across regions or in urban/rural areas. Providing access for all to safe places for physical activity and walking is a national public health goal (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services., 2015; United States Department of Health and Human Services, 2011), and determining where racial/ethnic differences are greatest could help efficiently target public health and transportation programs for safe walking.

Previous national-level reports (Paul et al., 2016; Schroeder and Wilbur, 2013) have lacked the sample size to examine the influence of demographic characteristics and geography (e.g., urban and rural areas, Census regions) on racial/ethnic differences in barriers to safe walking. The 2015 Cancer Control Supplement of the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) assessed three perceived barriers to safe walking (crime, traffic, and animals) among a nationally-representative sample of U.S. adults. This large sample provides a unique opportunity to address the limitations of previous reports. The purposes of this paper are to 1) determine if demographic characteristics influence national-level racial/ethnic differences in perceived barriers to safe walking and 2) determine if racial/ethnic differences in perceived barriers to walking are consistent in urban and rural areas and across Census regions.

Methods

Sample

Full NHIS methods are published by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) (National Center for health Statistics, 2017a). Briefly, NHIS is an annual in-person survey of U.S. households and uses multi-staged, probability sampling to create a representative sample of the non-institutionalized U.S. population. All study variables, with the exception of urban/rural residence, were publicly available for download from NCHS. All analyses utilizing urban/rural residence were performed in the Research Data Center after approval by NCHS (National Center for health Statistics, 2017b). The sample adult response rate was 55.2%, and data are weighted to account for non-response and ensure representativeness. The Research Ethics Review Board of NCHS approved all NHIS activities, and all participants provided informed consent.

The 2015 Cancer Control Supplement of the NHIS included 33,672 adult respondents aged ≥ 18 years, of whom 2,109 were missing at least one response to a safety barrier. An additional 130 respondents were missing information on education level, for a final sample size of 31,433 with complete information for all study variables. When compared by sex, age group, or race/ethnicity, respondents in the analytic sample were not substantially different from the full Cancer Control Supplement sample (<1% difference in all strata, weighted analyses).

Measures

Perceived barriers to safe walking were assessed for one household adult in the Cancer Control Supplement. Participants were asked “Where you live…

…does traffic make it unsafe for you to walk?”

…does crime make it unsafe for you to walk?”

…do dogs or other animals make it unsafe for you to walk?”

Response categories included “yes” or “no”, and those who declined to answer (n = 64) or answered “I don’t know” (n = 189) were treated as missing.

Participants reported demographic characteristics in the NHIS interview. Sex was self-reported as male or female. Age was categorized as 18–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–64, and ≥65 years. Race and ethnicity were categorized as non-Hispanic white (white), non-Hispanic black (black), Hispanic, and non-Hispanic other. Interpretation of results for the “other” category was difficult because multiple races were grouped together and the sample size was small. Therefore, this category was retained for reference purposes, but interpretation focused on whites, blacks, and Hispanics. Education level was used as an indicator of socioeconomic position (Shavers, 2007) and was categorized as less than high school, high school graduate or equivalent, some college, and college degree or higher. Education was used because of a low prevalence of missing values and similarities to other markers of socioeconomic position, such as family income.

Two geographic characteristics were examined: urban/rural residence and Census region. Urban/rural residence was based on the 2010 Census urban/rural designation for Census tracts (Ratcliffe et al., 2016). Briefly, urban areas were identified as Census tracts with at least 1,000 people/mile2 and adjacent tracts with at least 500 people/mile2. Additionally, some nonresidential urban land uses (e.g., airports) and non-continuous urban developments are designated as urban. Any areas not designated as urban were classified as rural (Ratcliffe et al., 2016). Census region (Northeast, Midwest, South, or West) was based on state of residence (Bureau, 2017).

Analysis

For each barrier, the prevalence of “yes” responses, and corresponding 95% confidence interval was estimated overall and stratified by demographic and geographic characteristics. Associations between reported barriers and both demographic and geographic characteristics were tested with adjusted Wald tests. When a significant association was detected, pairwise differences of a given barrier between levels of a covariate were tested with adjusted Wald tests including a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Trends across ordered categories were tested with orthogonal contrasts.

Multiple logistic regression analyses were used to examine the association between race/ethnicity and each barrier to walking, while adjusting for potential confounding by other demographic characteristics. To examine variation in racial/ethnic differences in barriers by geography, interaction terms were added to the model. First, effect modification by urban/rural residence was assessed through a race/ethnicity by urban/rural two-way interaction. If significant, the model was stratified by urban/rural residence and additional effect modification by Census region was assessed with a race/ethnicity and region interaction term. If the initial urban/rural interaction term was not significant, effect modification by Census region was assessed through a race/ethnicity by region interaction, while including adjustment for the main effect of urban/rural residence. Results with statistically significant effect modification were stratified by the modifying variable(s).

All analyses were performed in Stata 13 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, U.S.A.) using survey commands to account for the complex survey design and weighting. Results, including interaction terms, were deemed significant at p < 0.05.

Results

Sample characteristics

The analytic sample comprised 17,324 females and 14,109 males (Table 1). In the weighted sample, the majority of participants were 45 years of age or older, of non-Hispanic origin and white race, had at least some college education, and lived in urban areas. The largest share of respondents were from the South region.

Table 1:

Description of analytic sample and prevalence of barriers to walking by select characteristics among U.S. adults – NHIS 2015

| Sample characteristics | Traffica | Crimeb | Animalsc | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Unweighted n | Weighted % | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | |||

| Total | 31,433 | 100.0 | 23.4 | 22.6–24.3 | 12.4 | 11.8–13.0 | 10.5 | 10.0–11.1 | |||

| Sex | |||||||||||

| Women | 17,324 | 51.7 | 25.2 | 24.2–26.2 | 14.9 | 14.1–15.7 | 12.8 | 12.0–13.5 | |||

| Men | 14,109 | 48.3 | 21.6 | 20.5–22.8 | 9.7 | 9.1–10.4 | 8.2 | 7.5–8.8 | |||

| Age (years)d | |||||||||||

| 18–24 | 2,733 | 12.5 | 20.1 | 18.2–22.1 | 15.1 | * | 13.3–17.1 | 9.9 | * | 8.3–11.8 | |

| 25–34 | 5,382 | 17.5 | 23.8 | * | 22.1–25.5 | 13.6 | *† | 12.5–14.9 | 10.6 | * | 9.6–11.8 |

| 35–44 | 4,906 | 16.4 | 24.3 | * | 22.7–26.0 | 12.3 | * ‡ | 11.0–13.6 | 10.1 | * | 9.1–11.2 |

| 45–64 | 10,540 | 34.2 | 23.9 | * | 22.7–25.2 | 11.4 | ‡ | 10.6–12.3 | 10.9 | * | 10.1–11.8 |

| ≥65 | 7,872 | 19.3 | 23.7 | * | 22.3–25.2 | 11.4 | †‡ | 10.4–12.5 | 10.5 | * | 9.6–11.5 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 19,850 | 65.8 | 23.5 | * | 22.4–24.6 | 8.6 | 8.0–9.2 | 8.2 | * | 7.6–8.8 | |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 4,189 | 11.9 | 24.5 | * | 22.6–26.5 | 23.5 | 21.7–25.4 | 18.8 | 17.1–20.5 | ||

| Hispanic | 5,199 | 15.6 | 23.6 | * | 22.0–25.4 | 19.3 | 17.8–21.0 | 13.9 | † | 12.6–15.2 | |

| Other, non-Hispanic | 2,195 | 6.7 | 20.8 | * | 18.5–23.2 | 14.1 | 12.1–16.4 | 10.8 | *† | 8.5–13.7 | |

| Education levele | |||||||||||

| Less than high school | 4,349 | 12.5 | 29.3 | 27.3–31.4 | 20.6 | 18.9–22.4 | 16.5 | 14.7–18.3 | |||

| High school | 7,843 | 24.7 | 25.0 | * | 23.5–26.6 | 14.4 | 13.3–15.5 | 11.8 | * | 10.8–12.9 | |

| Some college | 9,808 | 31.3 | 23.9 | * | 22.6–25.1 | 12.4 | 11.4–13.4 | 10.8 | * | 10.0–11.7 | |

| College graduate | 9,433 | 31.5 | 19.5 | 18.2–20.8 | 7.6 | 6.9–8.3 | 6.9 | 6.3–7.6 | |||

| Census region | |||||||||||

| Northeast | 5,206 | 17.4 | 25.3 | 22.9–27.9 | 12.7 | * | 11.2–14.3 | 9.2 | * | 8.1–10.5 | |

| Midwest | 6,648 | 22.4 | 18.2 | * | 16.7–19.9 | 9.5 | 8.5–10.6 | 7.4 | * | 6.5–8.5 | |

| South | 10,724 | 36.8 | 29.4 | 28.0–30.8 | 13.8 | * | 12.9–14.9 | 13.8 | 12.8–15.0 | ||

| West | 8,855 | 23.4 | 17.7 | * | 16.4–19.1 | 12.8 | * | 11.7–13.9 | 9.3 | * | 8.3–10.3 |

| Urban/rural residencef | |||||||||||

| Urban | -- | 81.2 | 20.6 | 19.8–21.4 | 14.0 | 13.3–14.6 | 9.6 | 9.0–10.1 | |||

| Rural | -- | 18.8 | 35.8 | 33.5–38.2 | 5.6 | 4.6–6.8 | 14.7 | 13.2–16.5 | |||

Within columns, values that share a super-script symbol are not significantly different (Bonferroni-adjusted p≥0.05)

CI: Confidence interval

Participants were asked, “Where you live, does traffic make it unsafe for you to walk?”

Participants were asked, “Where you live, does crime make it unsafe for you to walk?”

Participants were asked, “Where you live, do dogs or other animals make it unsafe for you to walk?”

There were significant linear and quadratic trends (both p=0.003) for traffic across age groups, and a significant linear trend (p<0.001) for crime across age groups

There were significant linear and cubic trends for all barriers across education levels (traffic: linear p<0.001, cubic p=0.026; crime: linear and cubic p<0.001; animals: linear p<0.001, cubic p=0.002)

Unweighted cell sizes are suppressed for restricted variables

Barriers to safe walking by demographic characteristics and geographic location

Overall, traffic was the most commonly reported barrier to walking (23.4%), followed by crime (12.4%) and animals (10.5%) (Table 1). Women reported higher prevalence of all barriers compared to men. Those 18–24 years old reported traffic as a barrier less frequently than respondents in older age groups, which all reported similar perceptions of traffic. The prevalence of perceived crime as a barrier was lower with older age, though the prevalence was similar among adults aged 35 and older. There were no significant differences in the prevalence of animals as a barrier across age groups.

The unadjusted perceptions of traffic as a barrier did not differ significantly by racial/ethnic group, while the prevalence of perceived crime and animals as barriers did. Blacks reported the highest prevalence of crime as a barrier (23.5%), followed by Hispanics (19.3%), and markedly lower prevalence among whites (8.6%). This pattern was repeated for animals as a barrier, with the highest prevalence among blacks (18.8%), followed by Hispanics (13.9%), and whites (8.2%).

The prevalence of perceived traffic, crime, and animals as barriers was significantly lower with higher education, but the difference in the middle two categories, high school graduate and some college, was small (crime) or non-significant (traffic, animals). Adults with college degrees or higher reported the lowest prevalence of all three barriers.

Patterns of barriers by region differed, though the prevalence of each in the South was the highest (traffic, animals) or among the highest (crime) for all barriers. Traffic and animals as barriers were more commonly reported among rural-dwelling adults while crime as a barrier was more commonly reported among urban-dwelling adults.

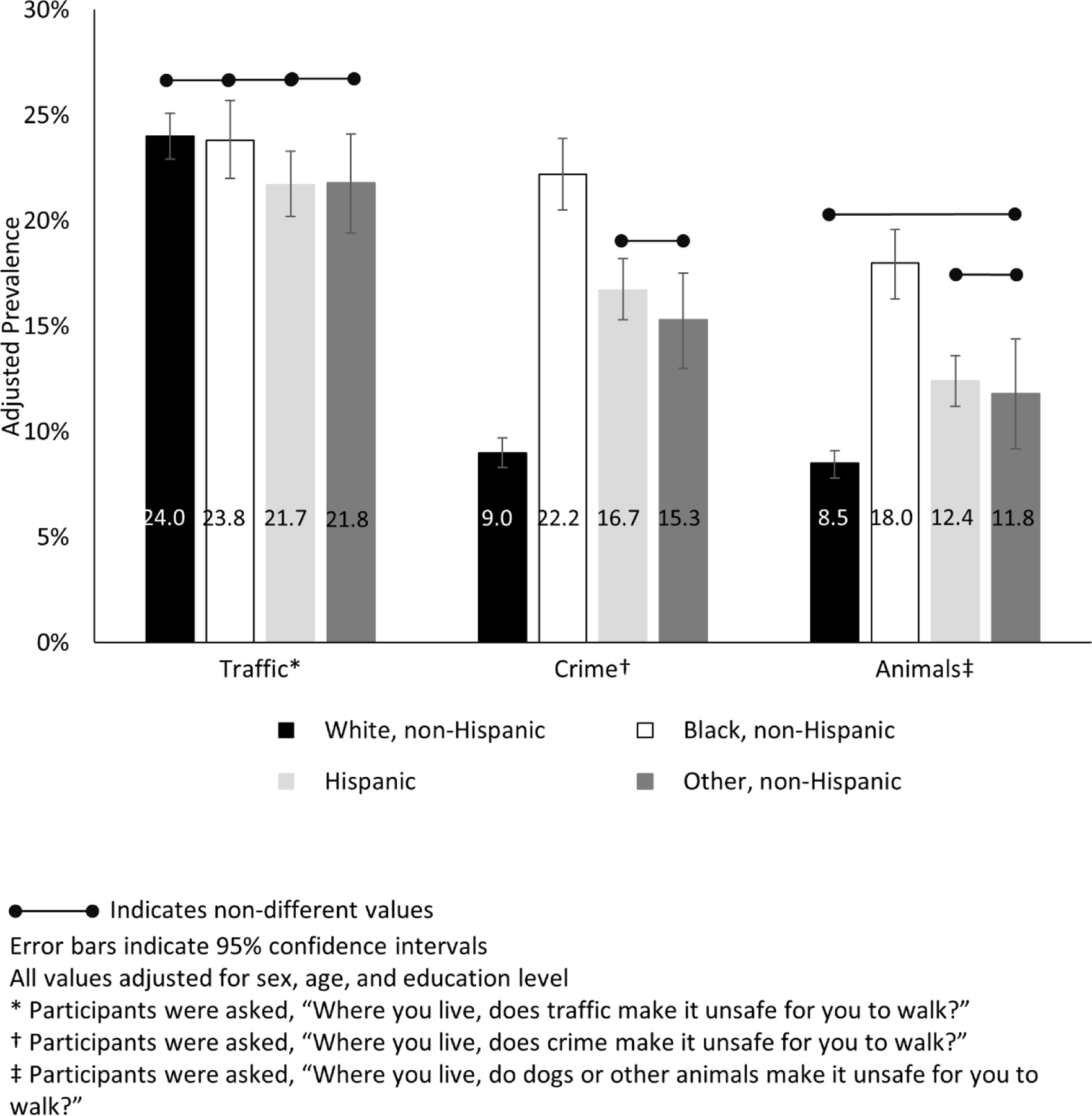

Barriers to safe walking by race/ethnicity, adjusted for demographic characteristics

After adjusting for sex, age, and education level, the prevalence estimates of barriers to safe walking across racial/ethnic groups were similar to unadjusted estimates (Figure 1). Perceptions of traffic as a barrier exhibited no significant differences by race/ethnicity. For crime and animals as barriers, the adjusted prevalence remained higher among blacks and Hispanics compared to whites.

Figure 1:

Adjusted prevalence of perceived traffic, crime, and animals as barriers to safe walking by race/ethnicity, NHIS 2015

Barriers to safe walking by race/ethnicity and geographic location

The association between race/ethnicity and traffic as a barrier to safe walking did not vary significantly by urban/rural residence (Table 2). Although there was no significant interaction between race/ethnicity and urban/rural residence, comparisons (presented as adjusted prevalence ratios) indicated blacks in urban areas reported traffic as a barrier more frequently than whites, which were the referent group. The association between race/ethnicity and crime as a barrier did not vary significantly by urban/rural residence. However, comparisons indicated blacks and Hispanics in urban areas, and blacks in rural areas, perceived crime as a barrier more frequently than whites. The association between race/ethnicity and animals as a barrier significantly differed by urban/rural residence. Blacks and Hispanics in urban areas, and blacks in rural areas, reported animals more frequently than whites. However, Hispanics reported animals as a barrier less frequently than blacks in rural areas (not shown, adjusted prevalence ratio [95% confidence interval]: 0.47 [0.25–0.69]).

Table 2:

Adjusted prevalence and prevalence ratios for perceived traffic, crime, and animals as barriers to safe walking among U.S. adults by urban/rural residence and race/ethnicity, NHIS 2015

| Traffica | Crimeb | Animalsc | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban/rural residence and race/ethnicity | % | 95% CI | APR | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | APR | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | APR | 95% CI |

| Urban | ||||||||||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 20.0 | 18.8–21.0 | 1.00 | Referent | 10.5 | 9.7–11.3 | 1.00 | Referent | 6.8 | 6.1–7.4 | 1.00 | Referent |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 22.5 | 20.7–24.4 | 1.13 | 1.02–1.24 | 23.1 | 21.3–25.0 | 2.21 | 1.96–2.46 | 17.1 | 15.4–18.8 | 2.52 | 2.19–2.86 |

| Hispanic | 21.3 | 19.8–22.9 | 1.07 | 0.97–1.17 | 16.9 | 15.4–18.4 | 1.62 | 1.43–1.81 | 12.2 | 11.0–13.4 | 1.81 | 1.55–2.06 |

| Other, non-Hispanic | 20.4 | 18.0–22.9 | 1.03 | 0.90–1.16 | 15.6 | 13.4–17.8 | 1.49 | 1.25–1.72 | 10.0 | 8.1–12.0 | 1.48 | 1.16–1.80 |

| Rural | ||||||||||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 35.8 | 33.2–38.4 | 1.00 | Referent | 5.1 | 4.0–6.2 | 1.00 | Referent | 13.5 | 11.9–15.2 | 1.00 | Referent |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 39.0 | 30.8–47.2 | 1.09 | 0.85–1.33 | 10.2 | 6.7–13.7 | 2.02 | 1.21–2.82 | 27.6 | 21.0–34.3 | 2.04 | 1.51–2.57 |

| Hispanic | 34.5 | 26.2–42.8 | 0.96 | 0.71–1.22 | 6.5 | 2.8–10.2 | 1.28 | 0.50–2.06 | 12.9 | 7.4–18.3 | 0.95 | 0.54–1.36 |

| Other, non-Hispanicd | 31.5 | 22.3–40.7 | 0.88 | 0.62–1.14 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

P-values for tests of interaction between race/ethnicity and urban/rural residence: Traffic p=0.66, Crime p=0.58, Animals p=0.006.

CI: Confidence interval; APR: Adjusted prevalence ratio

All models adjust for sex, age, and education level

Participants were asked, “Where you live, does traffic make it unsafe for you to walk?”

Participants were asked, “Where you live, does crime make it unsafe for you to walk?”

Participants were asked, “Where you live, do dogs or other animals make it unsafe for you to walk?”

Values with a relative standard error >30% are suppressed

The association between race/ethnicity and both traffic and crime as barriers to safe walking were different across Census regions after adjustment for demographic characteristics and urban/rural residence (Table 3). For traffic, only Hispanics in the South reported traffic as a barrier more frequently than whites. For crime as barrier to safe walking, blacks and Hispanics in all regions reported a significantly higher prevalence of crime as a barrier than whites, but the magnitude of the differences between blacks and whites and Hispanics and whites were more pronounced in the Northeast and Midwest than in the South and West. For example, compared to whites, blacks perceived crime as a barrier 2.77 times more frequently in the Northeast and 2.83 times more frequently in the Midwest but only 1.76 times more frequently in the South and 1.92 times more frequently in the West.

Table 3:

Adjusted prevalence and prevalence ratios for perceived traffic and crime as barriers to safe walking among U.S. adults by Census region and race/ethnicity, NHIS 2015

| Traffica | Crimeb | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Census region and race/ethnicity | % | 95% CI | APR | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | APR | 95% CI |

| Northeast | ||||||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 26.1 | 23.1–29 | 1.00 | Referent | 9.1 | 7.4–10.9 | 1.00 | Referent |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 23.4 | 18.4–28.5 | 0.90 | 0.68–1.12 | 25.4 | 20.3–30.4 | 2.77 | 2.01–3.54 |

| Hispanic | 23.5 | 18.9–28.1 | 0.90 | 0.69–1.11 | 20.2 | 15.5–24.8 | 2.21 | 1.55–2.86 |

| Other, non-Hispanic | 22.8 | 16.4–29.1 | 0.87 | 0.62–1.13 | 8.3 | 5.2–11.4 | 0.91 | 0.53–1.28 |

| Midwest | ||||||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 18.3 | 16.4–20.2 | 1.00 | Referent | 7.2 | 5.9–8.4 | 1.00 | Referent |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 18.1 | 14.1–22.2 | 0.99 | 0.75–1.24 | 20.3 | 16.7–23.9 | 2.83 | 2.11–3.55 |

| Hispanic | 17.3 | 12.5–22.1 | 0.95 | 0.66–1.23 | 12.9 | 9.4–16.4 | 1.79 | 1.24–2.35 |

| Other, non-Hispanic | 19.6 | 13.7–25.4 | 1.07 | 0.74–1.41 | 11.2 | 7–15.3 | 1.56 | 0.93–2.19 |

| South | ||||||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 28.5 | 26.8–30.2 | 1.00 | Referent | 10.9 | 9.7–12.2 | 1.00 | Referent |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 29.3 | 26.7–32 | 1.03 | 0.92–1.13 | 19.3 | 17.3–21.3 | 1.76 | 1.50–2.03 |

| Hispanic | 32.7 | 29.8–35.7 | 1.15 | 1.02–1.27 | 16.1 | 13.8–18.5 | 1.48 | 1.21–1.74 |

| Other, non-Hispanic | 29.1 | 23.2–34.9 | 1.02 | 0.81–1.23 | 16.2 | 11.7–20.8 | 1.48 | 1.05–1.92 |

| West | ||||||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 17.4 | 15.5–19.3 | 1.00 | Referent | 10.4 | 9.0–11.9 | 1.00 | Referent |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 23.4 | 17.7–29.1 | 1.35 | 0.99–1.71 | 20.0 | 14.6–25.5 | 1.92 | 1.35–2.50 |

| Hispanic | 16.2 | 14.1–18.4 | 0.93 | 0.78–1.09 | 13.6 | 11.6–15.5 | 1.30 | 1.03–1.57 |

| Other, non-Hispanic | 20.6 | 17.4–23.8 | 1.19 | 0.97–1.40 | 17.2 | 13.4–21.0 | 1.65 | 1.25–2.06 |

p-values for tests of interaction between race/ethnicity and region: Traffic p=0.03, Crime p<0.001

All models adjusted for sex, age, education level, and urban/rural residence

CI: Confidence interval; APR: Adjusted prevalence ratio

Participants were asked, “Where you live, does traffic make it unsafe for you to walk?”

Participants were asked, “Where you live, does crime make it unsafe for you to walk?”

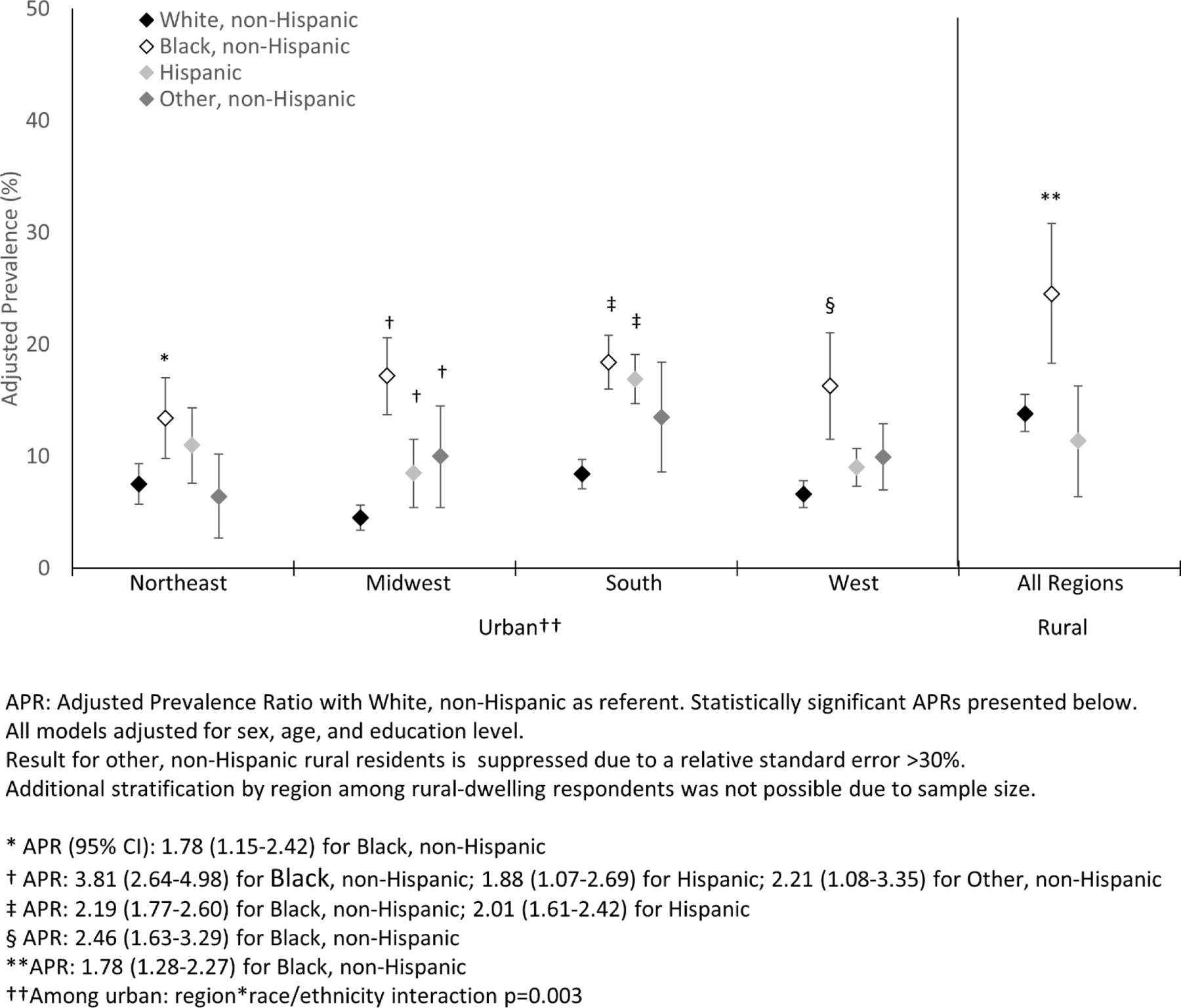

After stratifying by urban/rural residence, the association between race/ethnicity and animals as a barrier to safe walking was significantly different across Census regions among urban residents (Figure 2). There was insufficient sample size to test effect modification by Census region among rural residents. Among urban-dwelling adults in all regions, blacks reported a higher prevalence of animals as barriers than whites. In the Midwest and South, Hispanics also reported a higher prevalence of animals as a barrier than whites. Among rural-dwelling adults, after additional adjustment for Census region, blacks continued to report animals as barriers more frequently than whites and Hispanics, but there were no differences between whites and Hispanics.

Figure 2:

Adjusted prevalence of reported animals as a barrier to safe walking among U.S. adults in Urban or Rural Areas, stratified by Census region and race/ethnicity, NHIS 2015

Discussion

The 2015 NHIS allows examination of perceived traffic, crime, and animals as barriers to safe walking among adults at the national level. There were few racial/ethnic differences in traffic as a barrier, but differences in perceived crime as a barrier were present in all regions, and pronounced in the Northeast and Midwest. Further, racial/ethnic differences in reported animals as barriers varied by urban/rural residence and, among urban residents, by Census region. Notably, accounting for geography and important covariates did not eliminate racial and ethnic differences in perceived crime and animals as barriers to safe walking. These findings suggest a need for targeted work to address barriers to safe walking among racially and ethnically diverse populations.

Few national-level reports exist to compare with the present findings. In the 2012 ConsumerStyles survey, 18% of U.S. adults reported speeding vehicles (compared to 23% reporting traffic here), 8% reported perceptions of crime (12% here), and 10% reported dogs or other animals (11% here) as barriers that made walking difficult (Paul et al., 2016). Paul, et al., observed patterns across racial/ethnic groups similar to those observed here. The 2012 National Survey of Bicyclist and Pedestrian Attitudes and Behavior found 8% of respondents felt threatened for their personal safety during their last walk outdoors, and 2/3 of those identified motor vehicles as a safety concern (Schroeder and Wilbur, 2013). The low prevalence of safety concerns (8%) might be due to limiting inquiries to a particular episode of walking. Internationally, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) has reported data collected by the Gallup World Poll in 2014–2016 (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Develoment, 2017). The proportion who did not feel safe walking alone at night in their city or area where they lived ranged from 12% in Norway to 64% in South Africa, with 26% in the U.S., though the general nature of this question makes direct comparisons with the present results difficult.

Our results revealed differences in the prevalence of the three barriers for the overall population and across subgroups. For example, traffic as a barrier was reported by nearly one-quarter of U.S. adults while 12.4% reported crime and 10.5% reported animals as barriers. Further, perceived crime was associated with age, while animals were not, and both crime and animals were associated with race/ethnicity while traffic was not. These findings suggest single measures of perceived general safety (Schroeder and Wilbur, 2013) might be an initial screener to identify populations with safety concerns. Subsequently, because the most important barrier could vary across locations or demographic groups, targeted public health programs for safe walking might benefit from needs assessments that assess several possible safety barriers.

Pronounced differences in perceptions of traffic were observed across Census regions (highest in the South) and urban/rural residents (higher among rural residents). Notably, half of all rural residents live in the South (United States Census Bureau, 2016), so these findings likely contribute to each other. The finding among rural residents could also be explained by differences in pedestrian infrastructure. Vehicle volumes are higher in urban areas than rural areas (Federal Highway Administration, 2013), but urban areas may have appropriate pedestrian infrastructure (e.g., sidewalks, crosswalks) to separate walkers from vehicles. To better differentiate traffic concerns in various settings, future assessments may need to cover specific concerns, like speeding vehicles or traffic density. The prevalence of perceiving traffic as a barrier in this report (23.4% or 53 million adults) and previous reports (Paul et al., 2016; Schroeder and Wilbur, 2013) underscores the importance of addressing this barrier across the nation. The second goal of Step it Up! The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Promote Walking and Walkable Communities (Call to Action) calls for community designs that make it safe and easy to walk for people of all ages, including designing streets and sidewalks that slow vehicle speeds and separate pedestrians from other modes of traffic (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services., 2015).

There were considerable differences in the prevalence of perceived crime as a barrier to safe walking across racial/ethnic groups, with blacks and Hispanics reporting a higher adjusted prevalence than whites in all regions. These results are consistent with the 2016 National Crime Victimization Survey, in which blacks and Hispanics reported serious violent crimes (e.g., rape, robbery, aggravated assault) 30% more frequently than whites (Morgan and Kena, 2017). In our study, racial/ethnic differences in perceived crime tended to be larger in the Northeast and Midwest than the South and West. Regional differences in the number of racially and ethnically mixed neighborhoods might contribute to these differences: a 2015 analysis found 9 of the 10 cities with the fewest mixed neighborhoods were in the Northeast and Midwest, while the 10 with the most mixed neighborhoods were in the South or West (Frey, 2015). Arguably, residents of neighborhoods with mixed populations might share common experiences and perceive crime similarly. These results suggest areas in the Northeast and Midwest with large proportions of black or Hispanic residents might particularly benefit from efforts to understand and address the causes of perceived crime as a barrier to walking, which aligns with public health goals to provide safe and convenient places to walk for everyone (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services., 2015).

Racial/ethnic differences in perceived crime as a barrier across all Census regions remained after adjusting for sex, age, urban status, and education level. This suggests that regardless of underlying socio-demographic characteristics, areas with a large proportion of racial/ethnic minority residents may benefit from targeted interventions to reduce crime and concerns about crime to improve community walkability. The Call to Action recommends environmental design and maintenance to prevent violence and crime in affected areas (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services., 2015), including cleaning/maintaining vacant lots, and providing street lighting and ensuring visibility to residents (Garvin et al., 2013). Crime and violence prevention programs (e.g., mentoring and after-school programs) can complement environmental design and maintenance strategies (David-Ferdon et al., 2016). When these types of projects and programs are in place, walking groups that focus on minority populations (e.g., GirlTrek (GirlTrek, 2017)) can help community members experience improved neighborhood amenities through walking in a safe group environment.

Racial/ethnic differences in perceived animals as barriers varied by urban/rural residence and, among urban residents, by Census region. Blacks in all geographic areas reported animals more commonly than whites, as did urban-dwelling Hispanics in the Midwest and South. Perceiving animals as barriers was also generally more common in rural versus urban areas, and was particularly common among rural-dwelling blacks. Rural areas may have more diverse wildlife than urban areas, resulting in a broader array of potentially dangerous animals (Kays et al., 2008). Additionally, dog attacks may be more common in urban areas of low socio-economic position (New York City Department of Health, 2017), which could disproportionately impact racial and ethnic minorities. Hence, urban areas with large proportions of black and Hispanic residents, and rural areas in general, may benefit from efforts such as leash laws or increased enforcement to reduce barriers to walking posed by unconstrained animals.

Perceptions of safety are important correlates of walking behaviors (Kerr et al., 2016), but may or may not match directly observed measures of safety (Evenson et al., 2012). Assessing perceived safety barriers can help communities identify the most salient barriers in their populations, while objective measures might provide details needed for mitigation. For example, if traffic is perceived to be a problem, and direct observation reveals high-speed, low-volume traffic, then strategies to reduce speed or separate pedestrians from vehicles might most appropriately address residents’ concerns.

This study is subject to several limitations. First, results for racial and ethnic groups other than white, black, and Hispanic were not calculable due to small sample sizes. Second, Census regions are large and results could differ at smaller geographic scales. Third, a dichotomous categorization of urban and rural may omit information on suburban areas; future analyses could consider urban/rural gradients. Fourth, direct or objective measures of the environment were not available for simultaneous comparison with perceptions. Finally, this complete case analysis could bias results if those with missing data were not similar to those without.

This study also has several strengths. First, the 2015 NHIS is the first nationally representative health survey to assess perceived barriers to walking among adults, allowing national prevalence estimates. Second, the large sample size allowed for detailed analyses into differences among whites, blacks, and Hispanics. Third, conducting analyses in the NCHS Research Data Center allowed inclusion of urban status, which is an important environmental factor that is not publicly available.

Conclusions

These nationally-representative results suggest few differences in perceptions of traffic as a barrier across racial/ethnic groups, but considerable differences for perceived animals and crime. Racial/ethnic differences in reported traffic and crime as barriers to safe walking varied by Census region, and differences in reported animals as barriers varied by Census region and urban/rural residence. Addressing perceived barriers to safe walking among minority populations, especially crime and animals, could be a strategy to reduce previously-documented racial/ethnic differences in physical activity and walking. Communities and organizations working to reduce barriers to safe walking in racially and ethnically diverse communities may need to assess a variety of barriers, as the most important barrier can vary across regions and in urban and rural areas. Comparing perceived barriers to direct observations might help prioritize community interventions.

Acknowledgments

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: none.

References

- Adams MA, Frank LD, Schipperijn J, Smith G, Chapman J, Christiansen LB, Coffee N, Salvo D, du Toit L, et al. , 2014. International variation in neighborhood walkability, transit, and recreation environments using geographic information systems: the IPEN adult study. Int J Health Geogr 13:43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau, 2017. Geographic Terms and Concepts - Census Divisions and Census Regions United States Department of Commerce, Washington DC. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017. Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health, Atlanta, GA. [Google Scholar]

- David-Ferdon C, Vivolo-Cantor A, Dahlberg L, Marshall K, Rainford N, Hall J, 2016. A Comprehensive Technical Package for the Prevention of Youth Violence and Associated Risk Behaviors, in: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (Ed.). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA. [Google Scholar]

- Evenson KR, Block R, Diez Roux AV, McGinn AP, Wen F, Rodriguez DA, 2012. Associations of adult physical activity with perceived safety and police-recorded crime: the Multi-ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 9:146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federal Highway Administration, 2013. Highway Functional Classification: Concepts, Criteria and Procedures, in: United States Department of Transportation; (Ed.), Washington, DC, pp. 22–23. [Google Scholar]

- Foster S, Hooper P, Knuiman M, Christian H, Bull F, Giles-Corti B, 2016. Safe RESIDential Environments? A longitudinal analysis of the influence of crime-related safety on walking. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 13:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey W, 2015. Census shows modest declines in black-white segregation The Brookings Institution, Washington DC. [Google Scholar]

- Garvin EC, Cannuscio CC, Branas CC, 2013. Greening vacant lots to reduce violent crime: a randomised controlled trial. Inj Prev 19:198–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GirlTrek, 2017. GirlTrek [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser P, Auchincloss AH, Moore K, Sanchez BN, Berrocal V, Allen N, Roux AV, 2016. Associations of neighborhood socioeconomic and racial/ethnic characteristics with changes in survey-based neighborhood quality, 2000–2011. Health Place 42:30–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kays RW, Gompper ME, Ray JC, 2008. Landscape ecology of eastern coyotes based on large-scale estimates of abundance. Ecological applications : a publication of the Ecological Society of America 18:1014–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr J, Emond JA, Badland H, Reis R, Sarmiento O, Carlson J, Sallis JF, Cerin E, Cain K, et al. , 2016. Perceived Neighborhood Environmental Attributes Associated with Walking and Cycling for Transport among Adult Residents of 17 Cities in 12 Countries: The IPEN Study. Environ Health Perspect 124:290–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr Z, Evenson KR, Moore K, Block R, Diez Roux AV, 2015. Changes in walking associated with perceived neighborhood safety and police-recorded crime: The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Prev Med 73:88–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovasi GS, Hutson MA, Guerra M, Neckerman KM, 2009. Built environments and obesity in disadvantaged populations. Epidemiol Rev 31:7–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason P, Kearns A, Livingston M, 2013. “Safe Going”: the influence of crime rates and perceived crime and safety on walking in deprived neighbourhoods. Soc Sci Med 91:15–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan R, Kena G, 2017. Criminal Victimization, 2016, in: United States Department of Justice (Ed.), Washington, DC, p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for health Statistics, 2017a. National Health Interview Survey Methods Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Washington DC. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for health Statistics, 2017b. Research Data Center Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Washington DC. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics., 2016. Health, United States, 2015: With Special Feature on Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, in: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (Ed.). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Hyattsville, MD. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- New York City Department of Health, 2017. Preventing dog-bite related injuries among New York City residents, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Develoment, 2017. Better Life Index, Paris, France. [Google Scholar]

- Paul P, Carlson SA, Fulton JE, 2016. Walking and the Perception of Neighborhood Attributes Among U.S. Adults, 2012. Journal of Physical Activity and Health 14:36–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliffe M, Burd CH, Kelly, Fields A, 2016. Defining Rural at the U.S. Census Bureau, in: Commerce, U.S.D.o. (Ed.). United States Census Bureau, Washington DC. [Google Scholar]

- Saelens BE, Handy SL, 2008. Built environment correlates of walking: a review. Med Sci Sports Exerc 40:S550–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder P, Wilbur M, 2013. 2012 National Survey of Bicyclist and Pedestrian Attitudes and Behavior Volume 2: Findings Report, in: US Department of Transportation (Ed.). National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, Washington DC. [Google Scholar]

- Shavers VL, 2007. Measurement of socioeconomic status in health disparities research. Journal of the National Medical Association 99:1013–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton CM, Conway TL, Cain KL, Gavand KA, Saelens BE, Frank LD, Geremia CM, Glanz K, King AC, et al. , 2016. Disparities in Pedestrian Streetscape Environments by Income and Race/Ethnicity. SSM Popul Health 2:206–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services., 2015. Step it up! The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Promote Walking and Walkable Communities U.S. Dept of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General, Washington, DC. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau, 2010. Table CGT-P3: Race and Hispanic or Latino: 2010 - Region -- Urban/Rural and Inside/Outside Metropolitan and Micropolitan Area, 2010 Census Summary File 1, in: United States Department of Commerce (Ed.). United States Census Bureau, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau, 2016. Rural America, in: United States department of Commerce (Ed.). United States Census Bureau,, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Health and Human Services, 2011. HHS Action Plan to Reduce Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Ussery EN, Carlson SA, Whitfield GP, Watson KB, Berrigan D, Fulton JE, 2017. Walking for Transportation or Leisure Among U.S. Women and Men - National Health Interview Survey, 2005–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 66:657–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]