Abstract

In addition to a reverse transcriptase activity, telomerase is associated with a DNA endonuclease that removes nucleotides from a primer 3′ terminus prior to telomere repeat addition. Here we examine the DNA specificity of the primer cleavage-elongation reaction carried out by the Euplotes crassus telomerase. We show that the primer cleavage activity copurified with the E. crassus telomerase polymerase, indicating that it either is an intrinsic property of telomerase or is catalyzed by a tightly associated factor. Using chimeric primers containing stretches of telomeric DNA that could be precisely positioned on the RNA template, we found that the cleavage site is more flexible than originally proposed. Primers harboring mismatches in dT tracts that aligned opposite nucleotides 37 to 40 in the RNA template were cleaved to eliminate the mismatched residues along with the adjacent 3′ sequence. The cleaved product was then elongated to generate perfect telomeric repeats. Mismatches in dG tracts were not removed, implying that the nuclease does not track coordinately with the polymerase active site. Our data indicate that the telomerase-associated nuclease could provide a rudimentary proofreading function in telomere synthesis by eliminating mismatches between the DNA primer and the 5′ region of the telomerase RNA template.

The ends of linear eukaryotic chromosomes are nucleoprotein structures comprised of simple G-rich DNA repeats and structural proteins that together form a protective cap known as the telomere. The integrity of the telomere complex is essential for genome stability. Broken chromosomes lacking telomeres are detected at DNA damage checkpoints and, if not repaired, lead to cell cycle arrest (13, 38), chromosome fusion, or degradation (12). In most eukaryotes, telomerase is responsible for the synthesis and maintenance of telomeric DNA (15). Telomerase adds telomeric DNA to pre-existing telomere tracts and forms telomeres de novo on broken chromosome ends (reviewed in reference 29).

Telomerase is a reverse transcriptase ribonucleoprotein. The telomerase RNA subunits from a variety of different organisms have been characterized (11, 16, 39, 40), and proteins that fit the criteria for telomerase subunits have been isolated from the ciliates Tetrahymena thermophila and Euplotes aediculatus (7, 24) and from yeast and mammals (18, 24, 31, 32). Telomerase catalyzes polymerization of telomeric repeats onto chromosome 3′ termini by copying a sequence within its RNA subunit. In addition to the RNA templating domain, telomerase protein components also establish contacts with DNA substrates. A protein anchor site in telomerase binds clusters of dG residues upstream of a primer 3′ terminus and mediates processive elongation by maintaining primer contact during successive rounds of polymerization and primer translocation (17, 23, 28, 30).

The telomerases from T. thermophila, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and Euplotes crassus are associated with nuclease activities in vitro (6, 28, 33). The nuclease cuts single-stranded DNA primers, removing nucleotides from the 3′ terminus prior to primer elongation by telomerase. Although initially observed with telomeric primers (6), the nuclease activity from E. crassus was subsequently shown to eliminate long stretches of 3′ nontelomeric DNA from primers that carry a short internal tract of telomeric sequence (28). Nontelomeric DNA regions as long as 29 nucleotides can be removed by this mechanism (29a). Experiments with the Tetrahymena and Euplotes enzymes suggested that the nuclease active site is fixed relative to the 5′ boundary of the RNA template (1, 6, 28) such that any primer nucleotides extending across this site are subject to elimination. Studies with methylphosphonate-substituted oligonucleotide substrates revealed that cleavage proceeds by an endonucleolytic mechanism (28).

The function of the telomerase nuclease activity has been unclear. The combined endonucleolytic and polymerization activities of telomerase could serve a specialized function in ciliated protozoa during site-specific chromosome fragmentation and de novo telomere formation. These events are developmentally programmed and temporally coupled during the formation of the new macronuclear genome following conjugation (reviewed in reference 8). It has also been postulated that cleavage serves a proofreading function (6, 28, 33) and may be mechanistically linked to processivity (5).

Here we examine the DNA specificity of the cleavage-initiated polymerization reaction by the Euplotes telomerase. We show that the nuclease activity remains associated with telomerase through extensive purification, indicating that it either is an intrinsic property of the enzyme or is catalyzed by a tightly associated factor. We also demonstrate that the nuclease active site is not rigidly fixed relative to the telomerase RNA. Instead, any primer nucleotides that cannot form Watson-Crick base pairs with the rA residues adjacent to the 5′ boundary of the telomerase RNA templating domain, even single-nucleotide mismatches, are eliminated before synthesis initiates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation of Euplotes macronuclei and purification of telomerase.

E. crassus EG3 and EG15 were each grown in 150-liter aliquots, at a density of ∼104 cells/ml, and starved for 5 to 10 days. Cells were mated as described previously (36), and macronuclei active for telomerase were isolated approximately 65 h after mating (28). All subsequent procedures were carried out at 4°C. For purification, macronuclei were lysed in TMG (30 mM Tris-Cl [pH 7.5], 10% glycerol, 5 mM MgCl2) plus 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.25 μg each of leupeptin, pepstatin, chymostatin, and antipain, and 0.5 M potassium glutamate (KGlu) at 18,000 per ml, 1 lb/in2 by French press and centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The cleared lysate was loaded onto a DEAE-Sepharose column (Sigma) equilibrated with 0.5 M KGlu in TMG. The column was washed with 0.5 M KGlu, and activity was eluted with a linear salt gradient of 0.5 to 1.5 M KGlu. Peak fractions were loaded onto a phenyl-Sepharose (Sigma) column equilibrated with 0.5 M KGlu and washed with TMG. Activity was eluted with 2% Triton X-100. Active fractions were loaded onto a spermine-agarose (Sigma) column equilibrated with 0.5 M KGlu, washed with 0.5 M KGlu, and eluted with a linear salt gradient of 0.5 to 2.0 M KGlu. Active fractions were dialyzed into TMG and stored at −80°C or dialyzed into 50% glycerol–30 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.5)–5 mM MgCl2–1 mM DTT–0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and stored at −20°C. By using this procedure, telomerase was purified approximately 500-fold, based on the ratio of telomerase RNA to total protein (7).

Telomerase assays.

Telomerase was assayed at 30°C in 20-μl reaction mixtures containing 0.14 μM primer DNA, 5 mM MgCl2, 20 mM EGTA, 50 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0), 1 mM spermidine, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mM dTTP, and 0.25 μM [α-32P]dGTP (800 Ci/mmol). Reactions with purified telomerase were incubated for 15 min, and reactions with macronuclear extracts were incubated for 1 h, except where indicated otherwise. Telomerase reactions were stopped by the addition of EDTA, extracted with phenol:chloroform, and precipitated with ethanol. The pellets were resuspended into loading buffer (95% [vol/vol] formamide and 0.25% [wt/vol] xylene cyanol) and resolved on 10% sequencing gels, and products were detected with autoradiography. Cleavage products were quantified on a FUJIX BAS2000 PhosphorImager. For activity quantitation, a fraction of the reaction was blotted onto DE81 paper (Whatman) and washed as previously described (7). We have defined 1 U of activity as the amount of enzyme required to incorporate 2 fmols of [32P]dGTP (800 Ci/mmol) onto the primer (G4T4)3 in 15 min. Typically 5 U of telomerase was used in each reaction.

In experiments in which [α-32P]dTTP was used as the labeled nucleotide, 6.5 μM [32P]dTTP and 43.5 μM cold dTTP were added to obtain a final concentration of 50 μM. When the relative efficiency of primer cleavage was estimated, reactions were performed with [32P]dGTP and dTTP or with [32P]dTTP and dGTP (specific activities of both isotopes were adjusted to the same value). The amount of DNA product resulting from addition of the third dG residue in the sequence GGGGTTTT was quantitated by phosphorimaging.

Oligonucleotides.

DNA oligonucleotides were obtained from Oligos Etc. Inc. or Gibco BRL. Oligonucleotides were purified on 20% denaturing polyacrylamide gels, eluted overnight into Tris-EDTA buffer (10 mM Tris-Cl [pH 7.5], 1 mM EDTA), and purified with C18 columns (Waters) as per the manufacturer’s recommendation. Most of the sequences for the oligonucleotides used in this study are shown in Table 1. The remaining sequences are listed in the figure legends.

TABLE 1.

Cleavage primer sequences and quantification data

| Primer | Sequencea | Relative amt of cleavage productb

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclei | Purified | ||

| 7-G4T4-6 | cactatcGGGGTTTTgactac | 1 | 1 |

| 7-CG3T4-6 | cactatcCGGGTTTTgactac | 5.9 ± 1.3 | 6.3 ± 1.4 |

| 7-GAG2T4-6 | cactatcGAGGTTTTgactac | 4.2 ± 1.2 | 6.8 ± 1.7 |

| 7-G2CGT4-6 | cactatcGGCGTTTTgactac | 3.4 ± 0.75 | 2.8 ± 0.81 |

| 7-G3AT4-6 | cactatcGGGATTTTgactac | NDc | ND |

| 7-G4AT3-6 | cactatcGGGGATTTgactac | 0.65 ± 0.063 | 0.17 ± 0.11 |

| 7-G4TAT2-6 | cactatcGGGGTATTgactac | 0.81 ± 0.005 | 0.13 ± 0.085 |

| 7-G4T2AT-6 | cactatcGGGGTTATgactac | 1.4 ± 0.060 | 0.09 ± 0.089 |

| 7-G4T3A-6 | cactatcGGGGTTTAgactac | 0.78 ± 0.066 | 0.24 ± 0.19 |

Nonspecific flanking sequences are in lowercase letters, and the internal telomeric sequences are in uppercase letters. Underlining indicates the positions of the nucleotide changes.

Data are reported as ratios between the amounts of cleavage-initiated elongation products generated with 7-G4T4-6 relative to the products generated with other primers. Values are the averages and standard deviations from three independent experiments.

ND, not determined.

A 22-nucleotide molecular weight marker was generated by adding [32P]dGTP to the 3′ terminus of 7-G4T4-6 with terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase. The product corresponds to addition of the first nucleotide in the direct addition pathway. A 16-nucleotide product, corresponding to addition of the first nucleotide to the cleaved substrate 7-G4T4, was generated in the same manner, starting with a 15-nucleotide oligonucleotide. The migration positions for these two markers were used to analyze all of the data shown in the paper. However, in some cases, the deduced positions for the 15- and 18-nucleotide cleavage-initiated elongation products are indicated to make data interpretation simpler.

RESULTS

Endonuclease activity copurifies with E. crassus telomerase.

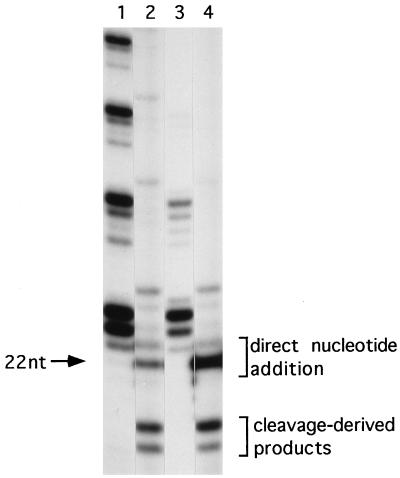

Previous experiments with Tetrahymena indicated that a nuclease activity copurified with telomerase (6). To determine if this was a general property of telomerase, we purified E. crassus telomerase from macronuclei over three consecutive chromatographic steps (estimated 500-fold purification) and then assayed primers that are normally substrates for cleavage. In the experiment shown in Fig. 1, telomerase was purified over DEAE-Sepharose, phenyl-Sepharose, and spermine-agarose. The purified telomerase exhibited decreased processivity relative to macronuclear extracts (Fig. 1, compare lanes 1 and 3), consistent with previous results after purification on glycerol gradients (4).

FIG. 1.

Copurification of telomerase endonuclease activity. Telomerase reactions were performed with 5 U of telomerase activity for 1 h at 30°C. Reactions with whole macronuclei (lanes 1 and 2) or purified telomerase (lanes 3 and 4) are shown. Primer substrates were GT4(G4T4)2 (lanes 1 and 3) and 7-G4T4-6 (lanes 2 and 4). See Table 1 for primer sequences. The arrow denotes the migration position of a molecular size standard. nt, nucleotide.

Despite its decreased processivity, the purified telomerase preparation retained the ability to cleave and extend the DNA primers (Fig. 1, lane 4). We have previously shown that telomerase utilizes two pathways for processing nontelomeric 3′ ends. The 3′ terminus of chimeric oligonucleotides containing an internal stretch of telomeric DNA surrounded by nontelomeric DNA may either be extended directly by nucleotide addition or endonucleolytically cleaved to eliminate the nontelomeric 3′ terminus. Cleavage exposes the internal telomeric cassette sequence for subsequent nucleotide addition by telomerase (4, 28). For example, the primer 7-G4T4-6 contains a cassette of telomeric sequence, G4T4, embedded between seven 5′ and six 3′ nontelomeric residues. In the cleavage-initiated elongation reaction, 7-G4T4-6 is cleaved so that the six 3′ nontelomeric nucleotides are eliminated. The shortened primer is then extended by the addition of telomeric sequence onto the newly created 3′ end (Fig. 1, lanes 2 and 4). Cleavage-initiated extension products can be distinguished from products generated by direct nucleotide addition because they migrate below the input primer on a DNA sequencing gel. Both types of products are detected when telomerase incorporates labeled nucleotides during synthesis of telomeric repeats (Fig. 1).

Telomerase reverse transcriptase activity never separated from the cleavage activity during purification. Another protocol that resulted in copurification of these two activities consisted of a polyethylene-glycol precipitation, followed by purification on DEAE-Sepharose, spermine-agarose, phenyl-Sepharose, and heparin-agarose (data not shown). The cleavage activity was also retained following poly(dG) affinity purification (data not shown) and during glycerol gradient sedimentation (4). These data indicate that the endonuclease activity associated with the E. crassus telomerase either is an intrinsic property of the enzyme or is catalyzed by a tightly associated factor.

Direct analysis of the cleavage reaction in the absence of polymerization would be very informative. However, we were unable to biochemically uncouple these two reactions. When purified telomerase was reacted with a primer carrying a 32P label on its 5′ end, in the presence or absence of deoxynucleoside triphosphates, specific cleavage products could not be detected (data not shown). In contrast, products arising from direct nucleotide addition onto the intact chimeric primer were observed with a 5′-labeled primer. Competition experiments revealed that the cleavage-elongation reaction was less efficient than the direct addition reaction (data not shown), which could explain our inability to detect cleavage products. In the experiments presented here, we infer that primer cleavage occurs because the elongation products generated are shorter than the original oligonucleotide and the reaction is inhibited by nonhydrolyzable nucleotide analogs placed at the predicted scissile bond (28).

The nuclease active site is not located at a fixed position relative to the telomerase RNA templating domain.

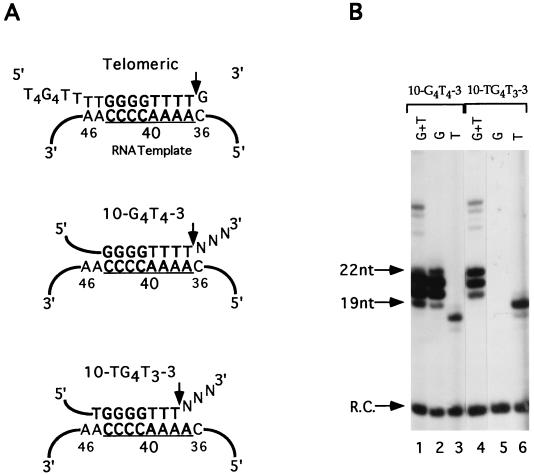

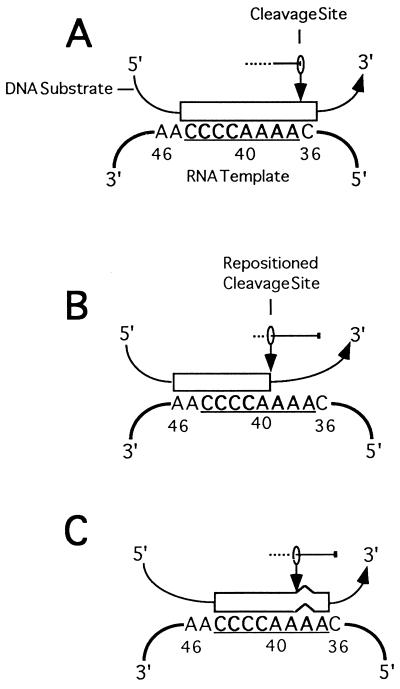

Telomerase nuclease activity can remove both telomeric and nontelomeric residues from a primer 3′ terminus (1, 5, 6, 28, 33). Previous studies indicated that cleavage removes nucleotides that extend across the 5′ boundary of the RNA template, whether they can form Watson-Crick base pairs with the telomerase RNA or not (Fig. 2A). Thus, it has been suggested that the cleavage site in telomerase is fixed at the 5′ boundary of the RNA template (1, 6, 28), which corresponds to position 36 in the E. crassus telomerase RNA sequence (39).

FIG. 2.

The nuclease active site is not fixed relative to the telomerase RNA template. (A) The predicted alignments for a telomeric primer and two chimeric primers on the E. crassus telomerase RNA template are shown. The predicted templating domain for the E. crassus telomerase RNA is underlined, and relative nucleotide positions are indicated (39). The proposed fixed cleavage site is illustrated at the top with the telomeric primer (T4G4)2T4G. Although the 3′ dG residue can align with position 36 in the telomerase RNA, this residue is removed (arrow) before the primer is elongated (28). Alignments for the chimeric primers 10-G4T4-3 and 10-TG4T3-3 are shown, and arrows indicate the positions of the predominant cleavage events. (B) Telomerase reactions with chimeric primers containing different permutations of the T4G4 cassette are shown. Reactions were performed with purified telomerase and either [32P]dGTP and dTTP (lanes 1 and 4), [32P]dGTP only (lanes 2 and 5), or [32P]dTTP only (lanes 3 and 6). To simplify the results, a 3′ ddC was added to 10-TG4T3-3 to block its processing by the direct addition pathway. A 12-nucleotide 5′-labeled recovery control oligonucleotide (R.C.) was included in the reactions. Because this oligonucleotide contains an extra phosphate on its 5′ terminus, it migrates as a 10- to 11-nucleotide DNA. 10-G4T4-3, CACTATCGACGGGGTTTTCAC; 10-TG4T3-3, CACTATCGACTGGGGTTTCAddC. Molecular size standards are indicated at left. nt, nucleotide.

To directly test whether the cleavage site is fixed, we performed telomerase assays with the primer 10-G4T4-3. The primer was cleaved and then elongated, as evidenced by the labeled products running below the input primer (Fig. 2B). The smallest of these products was 19 nucleotides in length, indicating that at least 3 nucleotides had been removed from this 21-mer primer followed by the addition of labeled dGTP (Fig. 2B, lane 1). To determine precisely how many residues had been eliminated from 10-G4T4-3 prior to telomerase elongation, reactions were carried out with [32P]dGTP or [32P]dTTP but not with both nucleotides (Fig. 2B, lanes 2 and 3). Examination of the first nucleotides added to the cleaved primer revealed that both dG and dT could be incorporated. In reactions with [32P]dGTP, four products of 19 to 22 nucleotides were obtained (Fig. 2B, lane 2). These corresponded to removal of the three 3′ nontelomeric nucleotides followed by the addition of four dG nucleotides. In addition, a prominent product of 18 nucleotides was labeled in the [32P]dTTP reaction (Fig. 2B, lane 3). This product corresponded to removal of the three 3′ nontelomeric nucleotides plus the fourth dT nucleotide from the G4T4 cassette followed by the addition of a radiolabelled dTTP.

To gauge the efficiency of cleavage at these two positions, we quantitated the cleavage-elongation products generated with either [32P]dGTP and dTTP or [32P]dTTP and dGTP. In a reaction with [32P]dGTP and dTTP, the 24-nucleotide product resulting from addition of the third dG in the first GGGGTTTT repeat added by telomerase will be present whether cleavage generated the substrate 10-G4T4 or 10-G4T3. However, the 24-nucleotide product should not be labeled in a reaction with [32P]dTTP and dGTP unless cleavage generates the 10-G4T3 substrate. Assuming that the elongation efficiencies of the G4T4 and G4T3 ends are approximately the same, the amount of label incorporated into the 24th nucleotide can be used to estimate the relative efficiency of cleavage at a particular site. These data suggested that the majority (≥80%) of the cleavage occurred after the fourth dT position, resulting in the addition of four [32P]dGTP residues to the primer (Fig. 2A and data not shown). However, because a significant proportion of the substrate (∼20%) was cleaved after the third dT residue, we conclude that the cleavage site is not rigidly fixed.

More direct evidence for flexible positioning of the nuclease active site in telomerase came from assays with chimeric oligonucleotides harboring different permutations of the internal G4T4 telomere cassette sequence. Changing the permutation of the internal telomeric cassette in the primer allowed us to systematically shift the primer’s base-pairing potential along the RNA template (Fig. 2A). The primer 10-TG4T3-3 was designed such that cleavage at the proposed fixed site would result in the elimination of two 3′ nontelomeric nucleotides. If the endonuclease activity functioned to remove nucleotides that could not base pair with the RNA template, an additional nucleotide would be removed. Elimination of this third nucleotide would generate a primer ending in G4T3 and would require the incorporation of dTTP by telomerase to initiate synthesis and maintain a perfect telomeric repeat (Fig. 2A). The primer 10-TG4T3-3 was assayed with [32P]dGTP or [32P]dTTP. No products were generated with [32P]dGTP (Fig. 2B, lane 5). However, a prominent band 19 nucleotides in length was obtained with [32P]dTTP (Fig. 2B, lane 6). This observation indicates that three nucleotides were removed from the 3′ terminus of 10-TG4T3-3, prior to the addition of a single [32P]dTTP. Fainter bands, corresponding to the 18- and 20-nucleotide elongation products were also detected, which suggests that cleavage of 10-TG4T3-3 might have occurred at more than one position. However, since the E. crassus telomerase always starts extension of nontelomeric DNA with the addition of dG and never with the addition of dT residues (28), we conclude that the 10-TG4T3-3 was extended only after removal of all three nontelomeric nucleotides from the primer 3′ terminus.

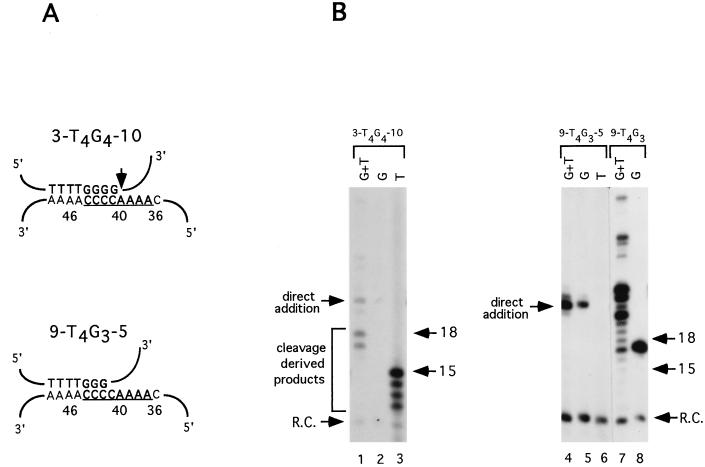

A similar result was obtained when telomerase was assayed with 3-T4G4-10. No products resulting from primer cleavage were generated in reactions with [32P]dGTP (Fig. 3B, lane 2); however, incorporation of [32P]dTTP was observed in products of 12 to 15 nucleotides in length (Fig. 3B, lane 3). Generation of a 12-nucleotide product is consistent with cleavage occurring after the fourth dG residue that aligns opposite nucleotide 41 in the telomerase RNA template. Taken together, these observations provide strong evidence for flexible positioning of the nuclease active site.

FIG. 3.

A boundary for the telomerase-associated nuclease on the RNA template. (A) The predicted alignments for chimeric primers on the E. crassus telomerase RNA template are shown. The site of primer cleavage is indicated by the vertical arrow. The predicted templating domain for the E. crassus telomerase RNA is underlined, and relative nucleotide positions are indicated. (B) Telomerase reactions with chimeric primers are shown. Reactions were performed with macronuclear extracts in the presence of [32P]dGTP and dTTP (lanes 1, 4 and 7), [32P]dGTP only (lanes 2, 5, and 8), or [32P]dTTP only (lanes 3, 6). Lanes 1 to 3 and 4 to 8 show results from two separate experiments. 3-T4G4-10, CACTTTTGGGGACGCGATCAT; 9-T4G3-5, CACTATCGATTTTGGGATCAT; 9-T4G3, CACTATCGATTTTGGG. Numbers at right of each gel are molecular size standards (in nucleotides). R.C., recovery control oligonucleotide.

Unexpectedly, moving the telomeric DNA sequence further 3′ into the telomerase RNA template strongly inhibited the primer cleavage-elongation reaction by telomerase. No cleavage-initiated elongation products were detected with the primer 9-T4G3-5. Instead, this primer was utilized solely by the direct addition pathway (28), and dG residues were added directly to its nontelomeric 3′ terminus (Fig. 3B, lanes 4 to 6). If this primer were cleaved after the third dG residue in the T4G3 sequence, an elongation product 17 nucleotides in length would be expected in a reaction with [32P]dGTP. This was not observed. The predicted cleavage product from this reaction, 9-T4G3, is an efficient substrate for telomerase elongation (Fig. 3B, lanes 7 and 8). Thus, failure to observe a cleavage-elongation reaction with 9-T4G3-5 is not due to the inability of telomerase to extend the cleaved substrate. Furthermore, the inefficiency of the cleavage-elongation reaction with 9-T4G3-5 does not result from decreasing the number of telomeric residues in the oligonucleotide from eight to seven. Cleavage-elongation reactions were observed with oligonucleotides containing the sequences G4 or GT4G surrounded by nontelomeric DNA (data not shown).

The simplest interpretation of our results is that the nuclease active site is restricted in its ability to cleave DNA primers associated with telomerase. We postulate that the nuclease “stretches” over only the 5′ portion of the RNA template, cleaving phosphodiester bonds in DNA primers at residues that do not form Watson-Crick base pairs with residues 37 to 40 in the telomerase RNA (see below).

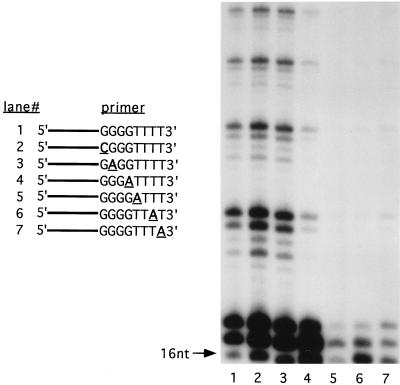

Altering the dG residues in the internal GGGGTTTT telomeric cassette alters the efficiency of the primer cleavage-elongation reaction.

We examined substrate requirements for cleavage-initiated elongation by assessing the roles of specific nucleotides within the telomeric sequence of the chimeric primer. Nucleotides within the telomeric cassette sequence of 7-G4T4-6 were systematically altered, and the primers were reacted with telomerase. Cleavage-initiated elongation products were resolved on sequencing gels (Fig. 4), and the data were quantified by phosphorimaging (Table 1). The amount of product resulting from polymerization to the third dG was expressed as a ratio relative to the amount of product generated with 7-G4T4-6. Reactions were performed with macronuclear extracts and with purified telomerase.

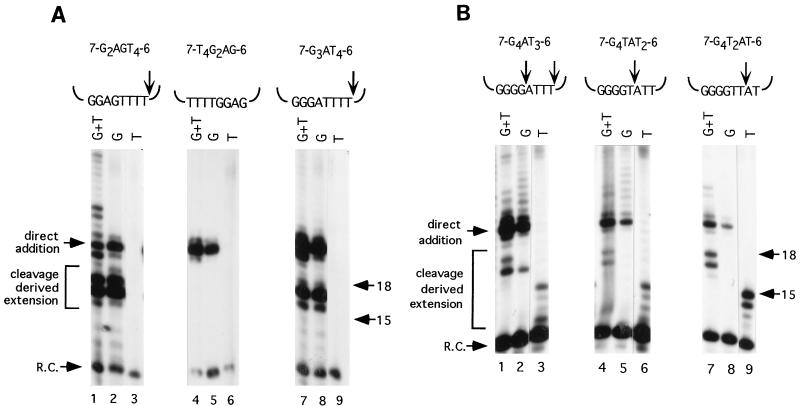

FIG. 4.

Effects of substrate point mutations on cleavage and polymerization. Cleavage substrates containing single-nucleotide changes within the internal telomeric sequence were reacted with purified telomerase. The positions of individual nucleotide changes within the telomeric cassette are shown (nucleotide sequences are listed in Table 1). Primers containing mismatches in the dG residues were cleaved after the fourth dT in the internal telomeric cassette. The elongation products generated after primer cleavage are designated +G1, +G2, and +G3 to indicate the residues that have been added to the cleaved substrate. The cleavage elongation reaction for primers containing mismatches in the dT tract was significantly less efficient. Lane 1, reaction with GT4(G4T4)2; lane 2, reaction with 7-G4T4-6. nt, nucleotide.

The ability of telomerase to cleave and extend a substrate was strongly dependent upon the position of the nucleotide alterations within the internal telomeric cassette. Changing any of the first three dG positions (underlined) in the internal GGGGTTTT sequence resulted in a three- to sevenfold increase in the amount of cleavage-initiated elongation product generated compared to the “wild-type” sequence (Fig. 4, compare lane 2 to lanes 3 to 5; Table 1). Like 7-G4T4-6, these primers were preferentially cleaved after the fourth dT residue in the internal telomeric cassette (see below).

We next tested whether alterations in the first three dG residues of the substrate specifically affected the extension step of the cleavage-dependent elongation reaction. Our approach was to compare utilization of “precleaved” primers to cleavage and extension of the corresponding full-length parental primers (Fig. 5). Precleaved primers were designed to mimic the predicted products of the endonucleolytic cleavage reaction prior to extension by telomerase. They carried no 3′ nontelomeric DNA. Like the full-length parental primers, precleaved substrates with alterations in the first three dG residues of the telomeric repeat showed an increase in total reaction products generated by purified telomerase (Fig. 5, compare lane 1 to lanes 2 and 3). These data suggest that single-nucleotide disruptions in the dG tract increase the efficiency of the polymerization step in the cleavage-elongation reaction, possibly by increasing primer turnover.

FIG. 5.

Reactions with precleaved substrates. Reactions were performed with purified telomerase. Primer telomeric sequences are indicated on the left. The 5′-flanking sequence, CACTATC, is depicted as a solid line. Underlined residues denote the positions of nucleotide changes within the telomeric repeat. The migration position of a molecular size standard is indicated. nt, nucleotide.

Altering the first three dG residues in the telomeric cassette did not change the site of DNA cleavage within these primers. For example, 7-G2AGT4-6 generated no products in a reaction with [32P]dTTP (Fig. 6A, lane 3). However, abundant products, 16 to 19 nucleotides in length, were obtained with [32P]dGTP (Fig. 6A, lane 2). Thus, the six nontelomeric residues on the primer 3′ terminus were removed followed by addition of one to four dG nucleotides. The dA residue in the dG tract of the telomeric cassette sequence was not eliminated. It is conceivable that 7-G2AGT4-6 was cleaved but not extended by telomerase. To test this possibility, we examined 7-T4G2AG-6. In contrast to 7-G2AGT4-6, this primer was not processed by the cleavage pathway. Instead, the six nucleotides of 3′ nontelomeric DNA remained intact and were extended by direct addition of two dG residues (Fig. 6A, lanes 4 to 6). The longer products generated in the reaction with 7-G2AGT4-6 resulted from processive elongation of the cleaved product (Fig. 6A, lane 1). Furthermore, in the reaction with dG only, the nontelomeric 3′ termini of both 7-T4G2AG-6 and 7-G2AGT4-6 were extended only two nucleotides (Fig. 6A, lanes 2 and 5). Thus, a mismatch in the dG tract inhibits elongation by the direct addition pathway.

FIG. 6.

Removal of mismatched nucleotides from DNA primers. Telomerase reactions were performed with macronuclear extracts and the primers indicated. Reactions with [32P]dGTP and dTTP (lanes 1, 4, and 7), [32P]dGTP only (lanes 2, 5, and 8), or [32P]dTTP only (lanes 3, 6, and 9) are shown. The flanking nontelomeric sequences are the same as in 7-G4T4-6. Molecular size standards (in nucleotides) and the recovery control oligonucleotide (R.C.) are indicated. The position(s) of cleavage is denoted by the arrow(s) above each primer. Processing of chimeric primers that contain mismatched residues in a dG tract (A) or a dT tract (B) are shown. Reactions with 7-G4AT3-6 and 7-G4TAT2-6 were less efficient than with primer 7-G4T2AT-6. Accordingly, the film was exposed twice as long (5 versus 2.5 days) to obtain data with these two oligonucleotides.

Primers containing variations at the fourth position in the GGGGTTTT in the internal cassette behaved differently than the other primers we tested. The most prominent band in the cleavage-derived products from this primer (+G2) was shifted to a position one nucleotide smaller than products generated with any other primers in this series (+G3) (Fig. 4, compare lanes 5 and 6). A −1 shift in the banding pattern could derive from a change in the site of primer cleavage, which results in the removal of an additional nucleotide from the primer 3′ terminus. If this was the case, the cleavage product should correspond to 7-G3AT3 and telomerase would be expected to incorporate a single dT residue before adding four dG nucleotides. To test this possibility, 7-G3AT4-6 was reacted with either [32P]dGTP or [32P]dTTP. Only dG residues were added (Fig. 6A, lanes 8 and 9), and product formation was not inhibited by ddTTP (data not shown). The size of the most abundant cleavage-elongation products obtained with [32P]dGTP corresponded to removal of the six 3′ nontelomeric residues followed by addition of three dG residues (Fig. 6A, lane 7). Even when dTTP was included in the reaction, elongation beyond this point was strongly inhibited (Fig. 4, lane 6). Likewise, the reaction with a precleaved 7-G3AT4 primer generated mostly short elongation products corresponding to the addition of the first three dG residues (Fig. 5, lane 4). Further extension of the primer was suppressed. It is unclear why a primer harboring a mismatch at this specific position in the telomeric repeat should be so poorly elongated by telomerase. Perhaps the active site becomes distorted when telomerase binds a primer with this particular mismatch. Taken together, these observations indicate that primers with nucleotide changes in a tract of dG residues strongly affect polymerization by telomerase. However, these imperfections in the telomeric repeat sequence cannot be removed by the telomeraseassociated nuclease.

Single-nucleotide mismatches in dT tracts are eliminated prior to primer elongation.

We next tested the effects of single nucleotide changes at the dT positions (underlined) within the GGGGTTTT sequence. Such residues are predicted to align opposite positions 37 to 40 in the telomerase RNA template. Altering any of the dT residues strongly diminished product formation in reactions with purified telomerase (Fig. 4, lanes 7 to 10), but the effects were less striking in reactions with macronuclear extracts (Table 1). Hence, the purified telomerase displayed increased stringency with respect to cleavage substrate recognition and/or processing.

In contrast to primers bearing mismatches in dG tracts, primers containing alterations in the dT nucleotides were specifically cleaved to remove the mismatched residue as well as the adjacent 3′ nucleotides. In reactions with 7-G4TAT2-6 or 7-G4T2AT-6, no cleavage-initiated elongation products were obtained in the presence of [32P]dGTP (Fig. 6B, lanes 5 and 8), and product formation was strongly inhibited by ddTTP (data not shown). However, in the presence of [32P]dTTP, 7-G4TAT2-6 generated products 12 to 15 nucleotides in length (Fig. 6B, lane 6), indicating that dT residues had been removed from the primer prior to elongation. In the case of 7-G4T2AT-6, products 14 and 15 nucleotides in length were the predominant products of the reaction with [32P]dTTP (Fig. 6B, lane 9), implying that most cleavage events generated the product 7-G4T2, which no longer contains the mismatched residue. The less-abundant products migrating below the major products may have resulted from imprecise positioning of the cleavage site.

Telomerase assays with the primer 7-G4AT3-6 gave a slightly more complex cleavage-elongation profile, with cleavage occurring at one of two discrete sites in this primer. A prominent product 17 nucleotides in length was obtained with [32P]dGTP (Fig. 6B, lane 2), indicating that a portion of the 7-G4AT3-6 primer was cleaved after the third dT residue in the cassette and then extended by the addition of dG residues. Since dG residues were added instead of a single dT, as expected for a primer terminating in three dTs, the deoxyribosyladenine (dA) residue in the primer apparently aligned opposite an rA residue in the RNA template prior to elongation.

The most efficient processing pathway for 7-G4AT3-6 resulted in removal of the dA residue from the internal cassette prior to telomerase elongation. Four products, 12 to 15 nucleotides in length, were generated in the reaction with [32P]dTTP, corresponding to primers that were cleaved 5′ of the dA residue in the G4AT3 cassette and then extended by one to four dT residues (Fig. 6B, lane 3). PhosphorImager analysis indicated that the primer cleavage-elongation reaction that eliminated the dA residue and the nucleotides 3′ of it was significantly more efficient (80%) than cleavage after the third dT residue in the internal cassette (20%) (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Flexible positioning of the telomerase-associated nuclease.

Nucleolytic activity is a common property of template-dependent DNA and RNA polymerases (20, 21). In this study, we used chimeric primers containing short stretches of telomeric DNA surrounded by nontelomeric DNA to investigate the DNA specificity of the telomerase-associated nuclease. In contrast to standard telomeric primers, the short telomeric sequence within chimeric primers is predicted to align at only one position on the RNA template (28), allowing us to investigate how Watson-Crick base pair formation between the primer and the telomerase RNA template influenced the cleavage reaction. We found that only a small stretch of telomeric sequence is sufficient to allow endonucleolytic cleavage and exposure of the telomeric DNA as a substrate for elongation. While only a short stretch of telomeric DNA is required, the permutation of this sequence dramatically affects both the efficiency of the reaction and the position of primer cleavage. These results cannot be explained by a nonspecific nuclease activity.

Instead, the data support a model in which the telomerase-associated nuclease displays flexibility in cleaving DNA. Working with telomeric primers, Collins and Greider showed that the only primer 3′ nucleotides subject to elimination were those residues that extended across the extreme 5′ boundary of the RNA template (6). We have now extended these original observations using chimeric primers. Our experiments revealed that the nuclease active site is not rigidly fixed with respect to the RNA template but can cleave phosphodiester bonds at the junction of telomeric and nontelomeric DNA up to four residues 3′ of the template boundary.

Only the 5′ region of the RNA templating domain is “scanned” by the telomerase-associated nuclease.

In addition to removing stretches of nontelomeric DNA from a primer 3′ terminus (28), the telomerase-associated nuclease can also recognize single-nucleotide mismatches between the primer and the RNA template. The nuclease preferentially removes the mismatch as well as the 3′ adjacent sequence, creating a 3′ terminus with precise complementarity to the RNA template. This new 3′ end is now a substrate for extension by reverse transcription. The ability of the telomerase-associated nuclease to specifically cleave primers at the junctions between telomeric and nontelomeric DNA suggests that the nuclease actively scans the RNA template.

Several lines of evidence indicate that the scanning mechanism does not occur throughout the entire telomerase active site but rather is confined to residues 37 to 40 where a tract of four dT residues in a primer would hybridize. First, the cleavage activity fails to remove the nontelomeric 3′ terminus on the primer 9-T4G3-5 (Fig. 3). The telomeric cassette in 9-T4G3-5 is predicted to align at residues 42 to 48 in the telomerase RNA and is not expected to extend into the 5′ region of the template. Second, single-nucleotide mismatches that are predicted to be located opposite the rC residues at positions 41 to 44 in the RNA template are not removed from primers (Fig. 6A). Such primers have alterations in one of the dG residues in an internal telomeric cassette. Nucleotide mismatches in dT residues, by contrast, are eliminated (Fig. 6B). Finally, the fact that the primer 7-G4AT3-6 is cleaved in two discrete places, after the fourth dG or the third dT, prior to telomerase elongation argues that the ability of the nuclease active site to recognize and cleave a primer mismatch across from residue 40 in the RNA template is compromised relative to primer cleavage across from residues 36 to 39 but is not ablated.

The nuclease activity may not actually recognize single-nucleotide mismatches between the primer and the RNA template. Rather, mismatched residues in the dT tract may prevent stable hybrid formation between the primer and 5′ region of the templating domain. The inability of the primer to form a hybrid with this region of the RNA may trigger the primer cleavage reaction. The apparent cleavage of the 7-G4AT3-6 primer in two places supports this interpretation. Base pairing between the dT residues and positions 36 to 39 in the RNA template may not be sufficient for stable hybrid formation between the primer and the 5′ region of the RNA template.

We speculate that a steric restriction in the telomerase ribonucleoprotein particle prevents the cleavage site from extending beyond nucleotide 40 on telomerase RNA. A similar barrier may be present at the 5′ end of the RNA template (residue 36 in the E. crassus telomerase), since both telomeric and nontelomeric nucleotides positioned across from this rC are subject to cleavage and elimination (1, 6, 28) (Fig. 7). Studies with Tetrahymena telomerase suggest that RNA-protein interactions within the ribonucleoprotein influence the flexibility of the nuclease active site. Telomerase particles reconstituted with wild-type RNA cleave primers only at the previously defined site (1). In contrast, telomerase complexes containing Tetrahymena proteins reconstituted with Glaucoma chattoni telomerase RNA exhibit aberrant nuclease activity in vitro, cleaving primers at other positions (5). The chimeric telomerase also displays reduced processivity compared to the wild-type telomerase (5). Hence, the cleavage and processive elongation may be mechanistically linked as is seen with RNA polymerase II (19, 34, 37). Consistent with this idea, the purified telomerase from E. crassus shows both increased stringency for cleavage substrates and significantly decreased processivity.

FIG. 7.

Model for cleavage by the telomerase-associated nuclease. The internal telomeric cassette sequence (open box) in a chimeric primer aligns with the RNA templating domain (underlined). The site of primer cleavage is dictated by primer alignment and complementarity to the RNA template. The nuclease active site (depicted with the vertical arrow) displays limited flexibility. All primer nucleotides that extend beyond the 5′ boundary of the templating domain (position 36) are eliminated, whether they are complementary to the telomerase RNA or not (A). The cleavage activity is repositioned for primers whose complementarity does not extend to the 5′ template boundary, and mismatched residues are removed (B). Single-nucleotide mismatches can be recognized and eliminated by the cleavage activity but only if they are positioned across from residues 37 to 40 in the RNA template (C). It is possible that mismatches in dT tracts destabilize the DNA-RNA hybrid so that no base pairs form in the 5′ region of the RNA template. The mismatch and the adjacent 3’ sequence would then be eliminated.

A possible role in proofreading for the telomerase-associated nuclease.

Homogeneity of the telomeric DNA tract is essential for telomere function, and indeed in most lower eukaryotes and in mammals, the most terminal regions of telomeres are comprised of invariant repeat arrays. Single-nucleotide mutations in telomeric repeat sequences impair normal interactions between structural telomere binding proteins and the DNA (22, 41). Such disruptions in the telomere complex can upset normal telomere length regulation (22, 27, 40, 41) which may, in turn, culminate in premature senescence and death (27, 40, 43).

DNA-dependent DNA polymerases achieve precision during synthesis by correct base selection and exonucleolytic removal of incorrectly inserted residues in the nascent chain (reviewed in reference 9). Base selection is facilitated by the geometry of the Watson-Crick base pair in the active site, while exonucleolytic editing reflects the melting capacity of the mispaired DNA residue at the 3′ end of the growing chain. Since addition of the next nucleotide after misincorporation is relatively slow, the exonuclease has a greater opportunity to eliminate the mismatched residue. Site-directed mutagenesis of the telomerase RNA templating domain revealed that the RNA bases strongly influence polymerization fidelity, presumably by maintaining the proper geometry of the enzyme active site during nucleotide selection (14, 33, 42). However, recent studies with Paramecium telomerase indicate that the fidelity of telomere synthesis is not mediated solely by the telomerase RNA subunit (26).

Our data suggest that the telomerase reverse transcriptase may have evolved a rudimentary system for proofreading telomeric DNA by using its associated endonuclease activity. Although viral reverse transcriptases lack 3′ to 5′ exonuclease activities (2, 35) and therefore must rely on other nucleotide-discriminating steps in the polymerization reaction for fidelity (reviewed in reference 3), telomerase appears to be only distantly related to retroviruses. Instead, telomerase bears a remarkable similarity to retrotransposons (10, 31). One of the interesting parallels between telomerase and retrotransposons is that both contain associated endonuclease activities (25, 28).

We have previously argued that the capacity to endonucleolytically cleave DNA primers that extend beyond the 5′ boundary of the telomerase RNA template could enhance the fidelity of the primer translocation step by ensuring that only those DNA residues that form base pairs with the functional templating domain are retained (28). We can now expand the range of activities ascribed to the telomerase nuclease (Fig. 7). This nuclease has a strong preference for cleaving DNA at the boundaries between telomeric and nontelomeric DNA, specifically eliminating those residues that do not hybridize with the telomerase RNA template. With this in mind, we can envision two additional roles that the nuclease activity could play in telomere synthesis. First, the activity could “repair” telomere ends by removing any 3′-terminal nucleotides that do not match the RNA template prior to telomerase elongation. Telomerase-associated cleavage activities are known to remove mismatched nucleotides near the 3′ terminus of telomeric DNA (4, 6, 33). Such a repair function could be very useful for telomerases that require their primers to display a stretch of perfect 3′-terminal complementarity to the RNA template for elongation (29). For example, telomerase from vegetatively growing Euplotes cells will not initiate synthesis on DNA that does not carry 4 to 5 bp of telomeric sequence on its 3′ terminus (4). The primer cleavage activity could help ensure that new telomere sequences are continually added to all chromosome ends.

Alternatively, the telomerase nuclease could provide a bona fide, albeit limited, proofreading function for telomerase by actively eliminating mismatched residues from primers during telomere synthesis. The nuclease can recognize and remove single-nucleotide mismatches in dT tracts but fails to eliminate mismatches in dG tracts. This limited capacity of the nuclease to remove imperfections at any position in a telomeric repeat suggests that the nuclease active site does not track coordinately with the polymerization site. However, since neither the E. crassus nor the T. thermophila polymerase activities could be biochemically separated from the nuclease (this work and reference 6), further studies will be required to determine the spatial relationship between the nuclease and polymerase active sites.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

E. C. Greene and J. Bednenko contributed equally to this work.

We thank Jeff Kapler for critically reading the manuscript and for helpful discussions.

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grant GM49157 (D.E.S.). National Science Foundation grant BIR9217251 was used to obtain a PhosphorImager.

REFERENCES

- 1.Autexier C, Greider C W. Boundary elements of the Tetrahymena telomerase RNA template and alignment domains. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2227–2239. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.18.2227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Battula N, Loeb L A. On the fidelity of DNA replication. Lack of exodeoxyribonuclease activity and error correcting function in avian myeloblastosis virus DNA polymerase. J Biol Chem. 1976;251:982–986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bebenek K, Kunkel T A. The fidelity of retroviral reverse transcriptases. In: Skalka A M, Goff S P, editors. Reverse transcriptase. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1993. pp. 85–102. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bednenko J, Melek M, Greene E C, Shippen D E. Developmentally regulated initiation of DNA synthesis by telomerase: evidence for factor-assisted programmed telomere formation. EMBO J. 1997;16:2507–2518. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.9.2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhattacharyya A, Blackburn E H. A functional telomerase RNA swap in vivo reveals the importance of nontemplate RNA domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:2823–2827. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.2823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collins K, Greider C W. Tetrahymena telomerase catalyzes nucleolytic cleavage and nonprocessive elongation. Genes Dev. 1993;7:1364–1376. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.7b.1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collins K, Kobayashi R, Greider C W. Purification of Tetrahymena telomerase and cloning of genes encoding the two protein components of the enzyme. Cell. 1995;81:677–686. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90529-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coyne R S, Chalker D L, Yao M-C. Genome downsizing during ciliate development: nuclear division of labor through chromosome restructuring. Annu Rev Genet. 1996;30:557–578. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.30.1.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Echols H, Goodman M F. Fidelity mechanisms in DNA replication. Annu Rev Biochem. 1991;60:477–511. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.60.070191.002401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eickbush T H. Telomerase and retrotransposons: which came first? Science. 1997;277:911–912. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feng J, Funk W D, Wang S-S, Weinrich S L, Avilion A A, Chiu C-P, Adams R R, Chang E, Allsopp R C, Yu J, Le S, West M D, Harley C B, Andrews W H, Greider C W, Villeponteau B. The RNA component of human telomerase. Science. 1995;269:1236–1241. doi: 10.1126/science.7544491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gall J G. Beginning of the end: origins of the telomere concept. In: Blackburn E H, Greider C W, editors. Telomeres. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1995. pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garvik B, Carson M, Hartwell L. Single-stranded DNA arising at telomeres in cdc13 mutants may constitute a specific signal for the RAD9 checkpoint. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:6128–6138. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.11.6128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gilley D, Lee M S, Blackburn E H. Altering specific telomerase RNA template residues affects active site function. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2214–2226. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.18.2214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greider C W. Telomerase biochemistry and regulation. In: Blackburn E H, Greider C W, editors. Telomeres. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1995. pp. 35–68. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greider C W, Blackburn E H. A telomeric sequence in the RNA of Tetrahymena telomerase required for telomere repeat synthesis. Nature. 1989;337:331–337. doi: 10.1038/337331a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hammond P W, Lively T N, Cech T R. The anchor site of telomerase from Euplotes aediculatus revealed by photo-cross-linking to single- and double-stranded DNA primers. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:296–308. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.1.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harrington L, McPhail T, Mar V, Zhou W, Oulton R, Bass M B, Arruda I, Robinson M O. A mammalian telomerase-associated protein. Science. 1997;275:973–977. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5302.973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Izban M G, Luse D S. The increment of SII-facilitated transcript cleavage varies dramatically between elongation competent and incompetent RNA polymerase II ternary complexes. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:12874–12885. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kassavetis G A, Geiduschek E P. RNA polymerase marching backward. Science. 1993;259:944–945. doi: 10.1126/science.7679800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kornberg A, Baker T A, editors. DNA replication. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: Freeman; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krauskopf A, Blackburn E H. Control of telomere growth by interactions of RAP1 with the most distal telomeric repeats. Nature. 1996;383:354–357. doi: 10.1038/383354a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee M, Blackburn E H. Sequence-specific DNA primer effects on telomerase polymerization activity. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:6586–6599. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.10.6586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lingner J, Hughes T R, Shevchenko A, Mann M, Lundblad V, Cech T R. Reverse transcriptase motifs in the catalytic subunit of telomerase. Science. 1997;276:561–567. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5312.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luan D D, Korman M H, Jakubczak J L, Eickbush T H. Reverse transcription of R2Bm RNA is primed by a nick at the chromosomal target site: a mechanism for non-LTR retrotransposition. Cell. 1993;72:595–605. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90078-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCormick-Graham M, Haynes W J, Romero D P. Variable telomeric repeat synthesis in Paramecium tetraurelia is consistent with misincorporation by telomerase. EMBO J. 1997;16:3233–3242. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.11.3233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McEachern M J, Blackburn E H. Runaway telomere elongation caused by telomerase RNA gene mutations. Nature. 1995;376:403–409. doi: 10.1038/376403a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Melek M, Greene E C, Shippen D E. Processing of nontelomeric 3′ ends by telomerase: default template alignment and endonucleolytic cleavage. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:3437–3445. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.7.3437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Melek M, Shippen D E. Chromosome healing: spontaneous and programmed de novo telomere formation by telomerase. Bioessays. 1996;18:301–308. doi: 10.1002/bies.950180408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29a.Melek, M., and D. E. Shippen. Unpublished data.

- 30.Morin G B. The human telomere terminal transferase enzyme is a ribonucleoprotein that synthesizes TTAGGG repeats. Cell. 1989;59:521–529. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakamura T M, Morin G B, Chapman K B, Weinrich S L, Andrews W H, Lingner J, Harley C B, Cech T R. Telomerase catalytic subunit homologs from fission yeast and human. Science. 1997;277:955–959. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakayama J-I, Saito M, Nakamura H, Matsuura A, Ishikawa F. TLP1: a gene encoding a protein component of mammalian telomerase is a novel member of the WD repeats family. Cell. 1997;88:875–884. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81933-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prescott J, Blackburn E H. Telomerase RNA mutations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae alter telomerase action and reveal nonprocessivity in vivo and in vitro. Genes Dev. 1997;11:528–540. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.4.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reines D, Ghanoui P, Li Q, Mote J. The RNA polymerase II elongation complex. Factor-dependent transcription elongation involves nascent RNA cleavage. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:15516–15522. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roberts J D, Bebenek K, Kunkel T A. The accuracy of reverse transcriptase from HIV-1. Science. 1988;242:1171–1173. doi: 10.1126/science.2460925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roth M, Lin M, Prescott D. Large scale synchronous mating and the study of macromolecular development in Euplotes crassus. J Cell Biol. 1985;101:79–84. doi: 10.1083/jcb.101.1.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rudd M D, Izban M G, Luse D S. The active site of RNA polymerase II participates in transcript cleavage within arrested ternary complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:8057–8061. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.17.8057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sandell L S, Zakian V A. Loss of a yeast telomere: arrest, recovery and chromosome loss. Cell. 1993;75:729–739. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90493-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shippen-Lentz D, Blackburn E H. Functional evidence for an RNA template in telomerase. Science. 1990;247:546–552. doi: 10.1126/science.1689074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Singer M S, Gottschling D E. TLC1: template RNA component of Saccharomyces cerevisiae telomerase. Science. 1994;266:404–409. doi: 10.1126/science.7545955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Steensel B, de Lange T. Control of telomere length by the human telomeric protein TRF1. Nature. 1997;385:740–743. doi: 10.1038/385740a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yu G-L, Blackburn E H. Developmentally programmed healing of chromosomes by telomerase in Tetrahymena. Cell. 1991;67:823–832. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90077-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yu G-L, Bradley J D, Attardi L D, Blackburn E H. In vivo alteration of telomere sequences and senescence caused by mutated Tetrahymena telomerase RNAs. Nature. 1990;344:126–132. doi: 10.1038/344126a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]