Abstract

DNA lesions that halt RNA polymerase during transcription are preferentially repaired by the nucleotide excision repair pathway. This transcription-coupled repair is initiated by the arrested RNA polymerase at the DNA lesion. However, the mutagenic O6-methylguanine (6MG) lesion which is bypassed by RNA polymerase is also preferentially repaired at the transcriptionally active DNA. We report here a plausible explanation for this observation: the human 6MG repair enzyme O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) is present as speckles concentrated at active transcription sites (as revealed by polyclonal antibodies specific for its N and C termini). Upon treatment of cells with low dosages of N-methylnitrosourea, which produces 6MG lesions in the DNA, these speckles rapidly disappear, accompanied by the formation of active-site methylated MGMT (the repair product of 6MG by MGMT). The ability of MGMT to target itself to active transcription sites, thus providing an effective means of repairing 6MG lesions, possibly at transcriptionally active DNA, indicates its crucial role in human cancer and chemotherapy by alkylating agents.

DNA in unwound (active) chromatin at sites of transcription or replication is vulnerable to damage induced by chemicals and irradiation (3, 7, 32, 34). Left unrepaired, these DNA lesions affect cell survival. First, they either inhibit DNA polymerase (11) or are miscoded by the polymerase during DNA replication (1, 30, 31). Second, they can halt RNA polymerase during transcription of active genes (44). For example, to overcome the possible lethal blockage of transcription due to the arrested RNA polymerase at the thymine-thymine (T-T) photodimer (or bulky DNA lesions) formed in the transcribing DNA strand by irradiation, bacteria use the MFD protein (a transcription repair coupling [TRC] factor), which interacts with the arrested RNA polymerase at the lesion and recruits the uvrABC repair proteins (bacterial nucleotide excision repair [NER] proteins) for its repair (41, 42). In eukaryotes, similar preferential repair of bulky DNA lesions in the transcribing DNA strand by the NER pathway, i.e., TRC, has been reported. However, the details of the mechanism appear to be much more complicated than the prokaryotic counterpart since coupling of eukaryotic DNA repair to transcription should involve several stages, such as nucleosome remodelling (e.g., the yeast RAD26 protein as a Swi2/Snf2-like ATPase [50]), assembling of the multicomponent preinitiation complex (e.g., the RAD25 helicase as a subunit of TFIIH [50]), and possibly others (e.g., the unestablished role of the human ERCC6 protein as a DNA-dependent ATPase [43]). Furthermore, TRC may be interrelated between different DNA repair pathways as mismatch repair-defective human cells may lack TRC of the T-T photodimer by NER (33).

The N-nitroso compounds are carcinogens to which we are all exposed because they are synthesized naturally in our gastrointestinal tract. They are also cytotoxic, and some of them, notably bis-chloroethylnitrosourea, are used in cancer chemotherapy. They owe their carcinogenic and toxic properties to their ability to alkylate the 6-oxygen of guanine in DNA. Cells protect themselves from these compounds with a DNA repair protein, O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT), which removes the alkyl group from the O6-alkylguanine and transfers it to a cysteine residue in the active site of the transferase (a suicidal repair protein) (37). Interestingly, the mutagenic O6-alkylguanine lesions are also preferentially repaired at transcriptionally active DNA. This was shown recently by direct measurements of the O6-ethylguanine residues formed and repaired in specific genes of rat cells treated with N-ethylnitrosourea (48), which agree with the findings for Escherichia coli, by quantifying the frequency of GC-to-AT point mutations resulting from the miscoding behavior of the O6-methylguanine (6MG) residues formed in the DNA of bacteria exposed to methylating agents (12, 42). However, unlike the arrested RNA polymerase-DNA lesion complex-mediated removal of bulky lesions in the transcribing DNA strand by NER, the O6-alkylguanine base in DNA does not arrest RNA polymerase. This results in directing the misincorporation of uridine at this site (12).

To address the question of how 6MG residues are preferentially repaired at transcriptionally active DNA by MGMT, we report here a detailed immunocytological study of the distribution of the repair protein within the cell nucleus. Studies with polyclonal antibodies specific for the N and C termini of MGMT show that MGMT is strongly localized in small foci (speckles or embedded structures) in the nucleus. Although this strong localization was not seen when monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) to inner regions of the transferase were used, the evidence is that this localization is a genuine phenomenon. These MGMT speckles are sensitive to α-amanitin and similar in locations to the bromo-UMP (BrUMP) incorporated (as speckles) into the newly synthesized RNA, suggesting that they are positioned at the sites of active transcription by RNA polymerase II. Further studies including (i) treatments of cells with low concentrations of N-methylnitrosourea (NMU) (to induce the repair of 6MG by MGMT) and DNase I (to probe the exposed DNA), (ii) protease V8 analysis of the active site alkylated MGMT (R-MGMT) formed during NMU treatment, and (iii) immunoprecipitation provide evidence that these MGMT speckles can rapidly repair the 6MG residues formed in the exposed and transcription-active DNA which is readily damaged by NMU. These results may explain the observation that O6-alkylguanine is removed more rapidly from active than from inactive genes (48). As O6-alkylguanine residues in DNA do not arrest transcription, we tentatively suggest that the direct presence of MGMT at active transcription sites may be a part of an alternative transcription-coupled repair pathway in repairing DNA lesions that escape the editing mechanism of the RNA polymerases, which is, therefore, different from that involved in transcription-coupled NER. Possibly, in active chromatin, MGMT might be taking the place of histone H1 in gaining access to the nucleosomal DNA for protecting this DNA from damage induced by alkylating agents.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines.

HeLa.CCL2B, MRC5, and WI-38 were from the American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, Md. MRC5.SV40 was a generous gift from P. Karran, Imperial Cancer Research Fund, London, United Kingdom. GM00037F and GM05509B were from the Coriell Institute for Medical Research, Camden, N.J. The cells were cultured according to the suppliers’ protocols.

Materials, immunochemistry, protease V8-Western blot analysis, and DNase I digestion.

α-Amanitin was purchased from Sigma, St. Louis, Mo. MAbs 3B8, 5H7, 4H11, and 6G8 were obtained from three hybridoma fusions (4). Mouse polyclonal antibodies (P30) were raised against clone 1 fusion protein as shown in Fig. 1a, subpanel A. Eighth-boost sera from five mice were purified with an MGMT affinity column. MGMT.PAb, affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal antibody to recombinant MGMT, does not recognize MGMT cleaved by protease V8 at E172 on Western blots (35). Procedures for staining were described elsewhere (4). Antibodies used were as follows: (i) MGMT antibodies, mouse antibodies (10 μg/ml) and rabbit MGMT.PAb (1.5 μg/ml); (ii) MAbs to bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) and 2,2,7-trimethylguanosine (TG) (Oncogene Science, Cambridge, Mass.), 5 μg/ml; (iii) human anti-Sm serum (human reference serum no. 5 from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Ga.), 1 to 50,000 dilution; (iv) secondary antibodies: fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) (green; Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany), tetramethyl rhodamine isocyanate (TRITC)–anti-rabbit IgG (red; Sigma), and FITC–anti-human IgG (green; Sigma), 1:50 dilution. DNA staining was with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) (1.5 μg/ml). For dual-antigen stainings, rabbit and mouse antibodies were combined and visualized by either single- or double-wavelength excitation (with a filter from Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). Procedures for immunostaining, protease V8 analysis, and immunoprecipitation were described previously (4, 35). For DNase I digestion, paraformaldehyde (4%)-fixed cells (on coverslips) were digested with DNase I (Sigma) in phosphate-buffered saline (with 5 mM MgCl2) for 1 h at 20°C before immunostaining.

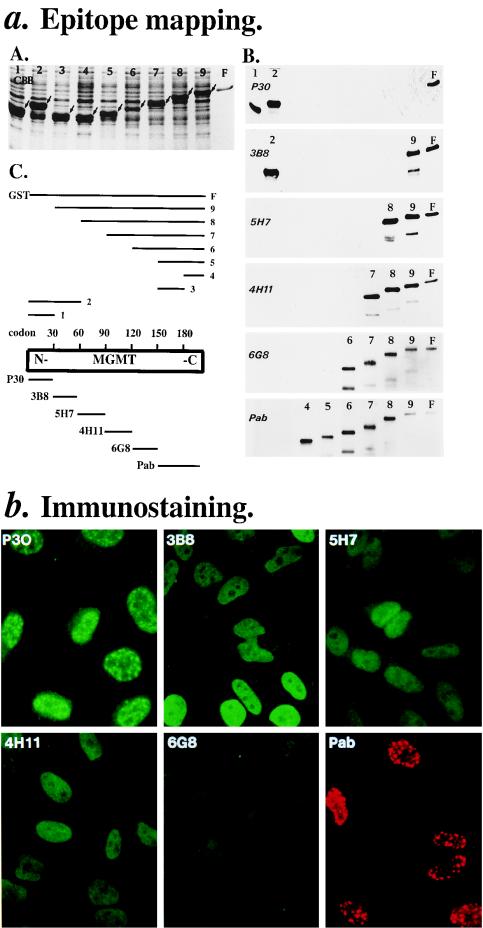

FIG. 1.

Antibodies to MGMT: epitope mapping and immunostaining. (a) Epitope mapping. (A) Coomassie blue staining of a sodium dodecyl sulfate–13.5% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gel of bacterial clones expressing soluble proteins (bands indicated by arrows [10 μg of crude proteins per lane] are domain-specific [lanes 1 to 3] and N-terminal deletion [lanes 4 to 9] GST fusion proteins of MGMT [see panel C]). (B) Western blot analysis of expressed proteins in panel A (300 μg of crude proteins per lane). Enhanced chemiluminescence times and antibodies used were as follows: 30 s for P30 (2.5 μg/ml), 2 min for 3B8 (3 μg/ml), 5 min for 5H7 (3 μg/ml), 5 min for 4H11 (3 μg/ml), 5 min for 6G8 (3 μg/ml), and 10 s for MGMT.PAb (1 μg/ml). Lower bands are degraded expressed proteins. (C) Summary: antibodies in order from the N to the C terminus of MGMT, i.e., P30, 3B8, 5H7, 4H11, 6G8, and MGMT.PAb. (b) Immunostaining. Amounts were 1.5 μg/ml for MGMT.PAb (in red with TRITC–anti-rabbit IgG) and 10 μg/ml for others (in green with FITC–anti-mouse IgG); pictures shown are at a magnification of ca. ×40 and under constant exposure.

Cloning and epitope mapping.

Fragments were cloned by PCR with BamHI (sense strand)- and EcoRI (antisense)-containing primers corresponding to 15 base residues in the 5′ and 3′ regions of the required inserts (28). The bacterially expressed crude proteins (4) were used directly for Western blot analysis.

Cell cycle experiments and labelling of newly transcribed RNA by BrUTP.

HeLa.CCL2B cells were grown in eight-well chamber slides (400 μl of medium per well). When one-third confluency was reached, cells were incubated with the required media for various times: (i) normal growth condition (G1) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) in minimal essential medium (MEM), (ii) G0 with 1% FBS followed by 0% FBS in MEM, and (iii) S with 2.5 mM thymidine in MEM with 10% FBS. Cells were fed every 12 or 5 h before fixation. For labelling of pre-mRNA by BrUTP, streptolysin O-permeabilized agarose-encapsulated cells were incubated in a mixture containing 2 mM ATP; 0.1 mM CTP, GTP, and UTP (or BrUTP [Sigma]); and 2 mM MgCl2 as described previously (17, 22). After fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde, cells were stained with MGMT.PAb and MAb.BrdU before they were spun onto slides for microscopy. Microinjections were performed as described previously (8, 14) by injecting the labelling mixtures into the nuclei of cells grown on marked coverslips with an Eppendorf microinjector (20 cells/min). Injected cells were incubated at 37°C for the required time before fixation with paraformaldehyde for immunostaining.

RESULTS

MGMT MAbs and polyclonal antibodies: epitope mapping and Western blot analysis.

To identify antibodies to different regions of human MGMT, we used our antibodies for Western blot analysis of various bacterially expressed domain-specific and deletion glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion proteins of MGMT (lanes 1 to 9 in Fig. 1a, subpanels A and C). Based on their inabilities to recognize expressed proteins lacking various regions of MGMT, the MAbs were mapped to codons 30 to 60 for 3B8, 60 to 90 for 5H7, 90 to 120 for 4H11, and 120 to 150 for 6G8 (summary in Fig. 1a, subpanel C). Although no MAbs were found to recognize codons 1 to 30 (N terminus) or 150 to 207 (C terminus) of MGMT, polyclonal antibodies to these regions were obtained from MGMT affinity column-purified polyclonal antibodies raised against GST fusion proteins containing codons 1 to 30 of MGMT and recombinant MGMT (P30 and MGMT.PAb in Fig. 1a, subpanel B; also Materials and Methods). All these antibodies were specific since the Western blot analysis in Fig. 2a showed that they recognized the 21-kDa MGMT in the mer+ (e.g., MGMT normal HeLa.CCL2B in lane b) but not mer− (MGMT-deficient MRC5.SV40 in lane c) cell extracts. Thus, in immunostaining experiments, these antibodies could detect the intracellular location of MGMT at 30 amino acid resolutions along its polypeptide backbone.

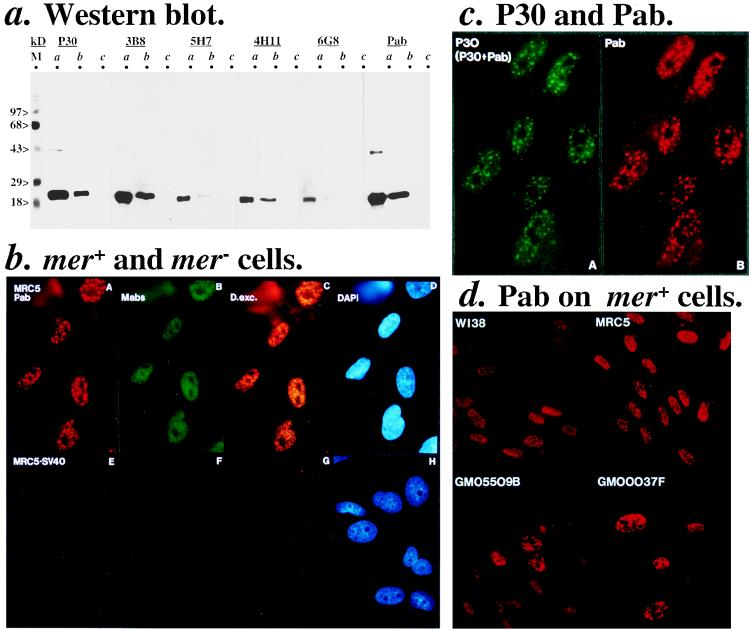

FIG. 2.

Specificities of MGMT antibodies. (a) Western blot analysis. Lanes labelled a, b, and c are purified recombinant MGMT (0.04 μg), HeLa.CCL2B (mer+; 200 μg of total cell extract), and MRC5.SV40 (mer mutant; 200 μg) samples, respectively. Conditions were 2 min of enhanced chemiluminescence for P30 (5 μg/ml), 3 min for 3B8 (6 μg/ml), 6 min for 5H7 (6 μg/ml), 6 min for 4H11 (6 μg/ml), 6 min for 6G8 (6 μg/ml), and 3 min for MGMT.PAb (3 μg/ml). M, prestained molecular weight markers. The 43-kDa band observed in the a lanes could be the dimer or improperly terminated recombinant MGMT. (b) mer+ (MRC5) and mer− (MRC5.SV40) cells. Pictures (magnification, ca. ×60) A, B, C, and D (MRC5) and E, F, G, and H (MRC5.SV40) are identical cells stained with combined MGMT.PAb (1.5 μg/ml in red), MAbs (3B8, 5H7, 4H11, and 6G8; 10 μg/ml in green), and DAPI (1.5 μg/ml in blue for nuclear DNA). Pictures C and G are double-wavelength excitation (D.exc.) of FITC and TRITC. (c) Speckles by P30 and MGMT.PAb. MRC5 cells were stained with combined P30 (in green) and MGMT.PAb (in red) and DAPI. Pictures are at a magnification of ca. ×100. (d) Speckles in mer+ cells by MGMT.PAb. Cells were stained with MGMT.PAb. Pictures (magnification, ca. ×40) shown are under constant exposure.

Intracellular localization of human MGMT by specific antibodies.

Immunostaining of HeLa.CCL2B (mer+) cells by these antibodies (Fig. 1b) showed two types of nuclear MGMT stainings; speckled (localized and concentrated MGMT) as revealed by P30 and MGMT.PAb polyclonal antibodies against the N and C termini, respectively, and diffused as revealed by MAbs (3B8, 5H7, 4H11, and 6G8) which recognize the inner regions of the protein. These antibodies when combined specifically stained MGMT because they recognized the mer+ cells (Fig. 2b, MRC5, pictures A and B) but not mer− cells (MRC5.SV40, pictures E and F), similar to the Western blot analysis in Fig. 2a. Although they are polyclonal antibodies, interestingly P30 (N terminus) and MGMT.PAb (C terminus) identify identical speckled structures in costaining experiments (Fig. 2c). This result provides further evidence that the speckled staining pattern is related to MGMT. As the intensities of the speckles were not reduced when the two antibodies were used either individually (Fig. 1b) or simultaneously (Fig. 2c), this result suggested that the N and C termini of MGMT might not interfere with each other in the formation of the speckles.

Several mer+ cell lines were then stained by MGMT.PAb. These are the frequently used MRC5 and WI-38 cells and the potentially NER-defective GM05509B and GM00037F cells. Fig. 2d shows that the speckled staining pattern is consistently present in all these mer+ cell lines, although some GM05509B cells showed lower levels of MGMT and fewer speckles. Thus, this speckled form of MGMT may be a general characteristic of mer+ cells. Interestingly, various speckled nuclear staining patterns have been reported for nucleic acids and related proteins in the mammalian cell nucleus (6), which might also represent target sites for MGMT function: examples of discretely localized nucleic acids include replicating DNA at the S phase (27), mRNAs (53), capped RNAs (5, 45), small nuclear RNAs (snRNAs) (20), and incorporated BrUMP residues in active transcription sites (17, 22), for proteins such as SC35 and small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particles (20, 46). Therefore, we investigated the appearances of MGMT speckles throughout the cell cycle when the possible target sites for MGMT, i.e., the genomic DNA, are undergoing a drastic change from an open (transcription and replication) to a condensed (mitosis) structure.

MGMT distribution in the cell cycle.

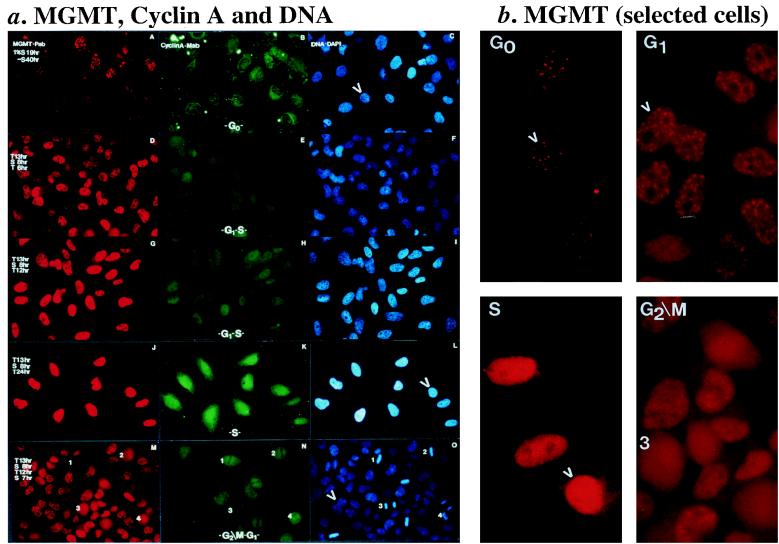

Cells (HeLa.CCL2B) were enriched at different phases of the cell cycle by serum depletion and double-thymidine blocking conditions. A MAb against cyclin A (to identify cells at different phases of the cell cycle [39]) and the MGMT.PAb were used to costain these synchronized cells. Figure 3 shows that cells at G0, arrested in low serum, were characterized by the presence of weak MGMT speckles (picture A in panel a and the enhanced picture G0 in panel b) and extranuclear staining of cyclin A (picture B in panel a). Both MGMT (pictures D, G, and J in panel a and picture S in panel b) and cyclin A (pictures E, H, and K in panel a) showed intense nuclear staining as cells progressed into the S phase (particularly during a double-thymidine block). Under these conditions, it was unclear whether the MGMT speckles remained since the strong nuclear staining could have masked them. At G2/M, cells were characterized by a lack of a definable nuclear structure, condensed DNA (see cells labelled 1, 2, 3, and 4 in picture O in panel a), and diffused MGMT staining (picture M in panel a and picture G2/M in panel b), whereas cyclin A was excluded from the condensed DNA (picture N in panel a). These observations suggest that the MGMT speckles are present in G0 and G1 (perhaps, S-phase cells) and that they are associated with open rather than condensed chromatin.

FIG. 3.

Cell cycle variation of MGMT speckles in HeLa.CCL2B cells. (a) MGMT, cyclin A, and DNA stainings. Pictures (magnification, ca. ×40) A, B, and C (G0 cells; grown under serum-free conditions); D, E, and F (early thymidine blocking); G, H, and I (first thymidine blocking); J, K, and L (S-phase cells; during double-thymidine blocking); and M, N, and O (cell populations from G2/M to G1; after release of the S-phase blocked cells) are individual sets of identical cells stained by combining MGMT.PAb (red, 1.5 μg/ml [A, D, G, J, and M]), cyclin A-MAb (green, 5 μg/ml [B, E, H, K, and N]), and DAPI (C, F, I, L, and O). Conditions for cell treatments are abbreviated as follows: S, complete serum (10% FBS in MEM); 1% S, 1% FBS in MEM; −S, 0% FBS in MEM; T, MEM containing 10% FBS and 2.5 mM thymidine (for S-phase synchronization); for example, S 8 hr is treatment under complete medium for 8 h before staining. G2/M cells with condensed DNA are marked 1, 2, 3, and 4 in pictures M, N, and O. (b) MGMT staining from selected cells. G0 cells are selected from picture A in panel a (see arrowhead-denoted cell in the DAPI staining in picture C); G1 cells are from picture M (see arrowhead-denoted cell in picture O); S cells are from picture J (see arrowhead-denoted cell in picture L); G2/M cells are from picutre M (see labelled cell 3 in picture O).

The relationship between MGMT speckles and transcription.

The above result suggests that the origin of these MGMT speckles may be related to transcription because (i) transcription activity diminishes upon chromatin condensation at G2/M (15, 36) at which MGMT speckles are also absent and (ii) MGMT speckles may peak at the S phase when transcription and replication (assembled from the preexisting transcription sites [18, 19]) activities are maximal. We, therefore, examined the relationships between the MGMT speckles and transcription by using transcription inhibitor and markers.

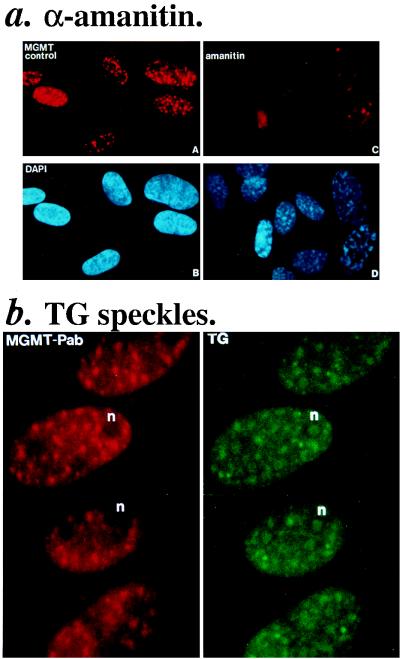

First, cells were treated with α-amanitin, which selectively blocks transcription by RNA polymerase II. Figure 4a shows that this inhibitor causes the disappearance of the MGMT speckles. Since Western blot analysis of the MGMT levels in these treated cells extracts by MAb.3B8 did not show obvious changes compared to the control (data not shown), MGMT speckles should be related to transcription by RNA polymerase II.

FIG. 4.

MGMT speckles and transcription. (a) α-Amanitin. Cells were treated with α-amanitin (50 μg/ml for 4.5 h) followed by staining with MGMT.PAb (A and C) and DAPI (B and D). (b) TG. HeLa.CCL2B cells were stained with combined antibodies; anti-TG MAb (in green) and MGMT.PAb (in red). n, nucleolus.

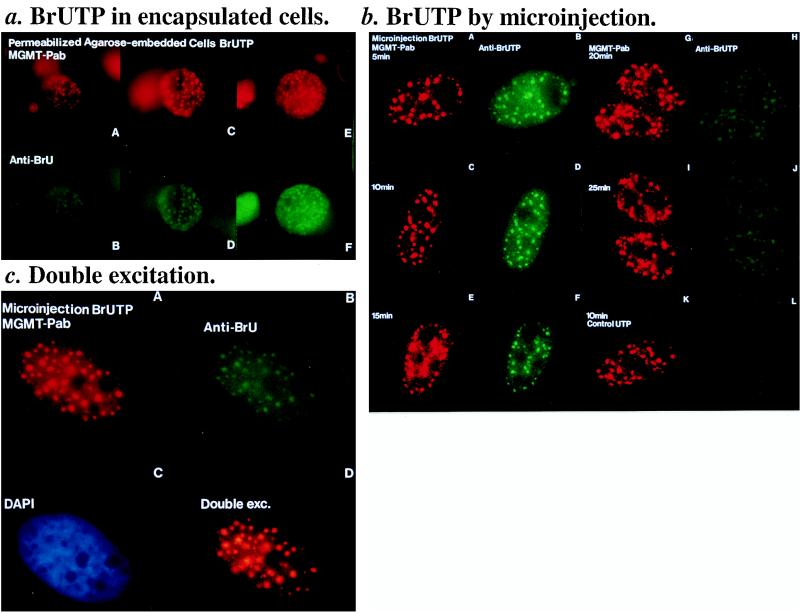

In order to establish the actual locations of MGMT speckles in the nucleus with respect to transcription by RNA polymerase II or various RNA species, we costained the cells with MGMT.PAb and a MAb against 2,2,7-trimethylguanosine (TG). TG can serve as a gross marker for potential nuclear locations of RNA formation, processing, and storage since it is a common structure found in capped snRNAs or pre-mRNAs (5, 45). Figure 4b shows that there is some similarity between MGMT and TG speckles, except for the nucleoli, where the TG antibodies stain the snRNAs. Therefore, these results suggest that MGMT speckles may be in close proximity to the pre-mRNAs that are recognized by TG antibodies. To confirm this, we pulse-labelled the transcribing RNAs with BrUTP with streptolysin O-permeabilized agarose-embedded cells (17, 22) and by microinjection (8, 14). In the permeabilized cell experiments, the MGMT speckles appear to mirror the incorporated BrUMP (visualized by MAb.BrdU [17]) as shown in Fig. 5a, where only individual cells are shown because the agarose-encapsulated cells have different morphologies and they are not on the same focal plane due to their thickness. When cells were labelled by microinjection, Fig. 5b showed that the BrUMP speckles appeared almost immediately after microinjection. For the 25 min when these were observable, the BrUMP and MGMT speckles were entirely superimposable (Fig. 5c) although the MGMT speckles appeared to be larger and more intense than the BrUMP speckles. This may be due to the differences in the efficiency of excitation of the red and green fluorescence or differences in concentration of the two antigens present at the active transcription sites. As labelling by microinjection was discontinuous, the loss of incorporated BrUMP speckles (the pre-mRNAs) with time (when BrUTP was consumed) could be expected as the pre-mRNAs had a rapid turnover rate, i.e., for translation and degradation.

FIG. 5.

Colocalization of incorporated BrUMP and MGMT speckles. (a) BrUTP with agarose-encapsulated cells. Pulse-labelling of newly synthesized RNA (or active-transcription sites) by incubating streptolysin O-permeabilized agarose-embedded cells with transcription labelling mixture containing BrUTP. Magnification, ca. ×40. A and B, C and D, and E and F are identical cells stained by MGMT.PAb (in red) and MAb-BrdU (in green; for incorporated BrUMP) simultaneously; note that the cells are spherical in shape due to the embedded agarose. (b) BrUTP with microinjection. Transcription labelling mixture in phosphate-buffered saline was injected into the nuclei of HeLa.CCL2B cells. Injected cells were incubated at 37°C for the required time in minutes before fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde for staining similar to that described for panel a. Magnification, ca. ×90. A and B, C and D, E and F, G and H, I and J, and K and L are identical cells visualized by single-wavelength excitation for MGMT in red and incorporated BrUMP in green, respectively. Pictures K and L are control cells injected with transcription labelling mixture containing UTP instead of BrUTP. (c) Dual-antigen stainings. MGMT and incorporated BrUMP speckles (after 10 min of labelling) were visualized by single (red or green)- and double (“Double exc.” in picture D)-wavelength excitations for half the exposure time of panel c.

Sensitivity of MGMT speckles to DNase I.

The relationship between the newly synthesized RNA (or active transcription sites) and MGMT speckles was further investigated by DNase I digestion (as reported for spliceosome factors [46]) because MGMT is functionally related to the DNA but not RNA (37) component of the transcription sites. Paraformaldehyde-fixed cells were partially digested with DNase I before staining with MGMT.PAb. Figure 6a shows that MGMT speckles were rapidly destroyed at 2 and 4 μg of DNase I treatment (pictures A and B), giving rise to intense and diffused nuclear stainings. Further increases from 10 to 50 μg of DNase I led to the loss of MGMT (pictures C and D) and DNA (picture F) stainings. Moreover, the staining of Sm antigens (spliceosome factors) was maintained under this condition, and they exhibited a different speckled staining pattern compared to MGMT (pictures A and E). These results showed that the nuclease digestion is specific and that MGMT speckles are associated with the DNA component in the active transcription sites. The sensitivity of MGMT speckles to low concentrations of DNase I (2 to 4 μg/ml) is, therefore, similar to the nuclease-hypersensitive sites in isolated nuclei (15).

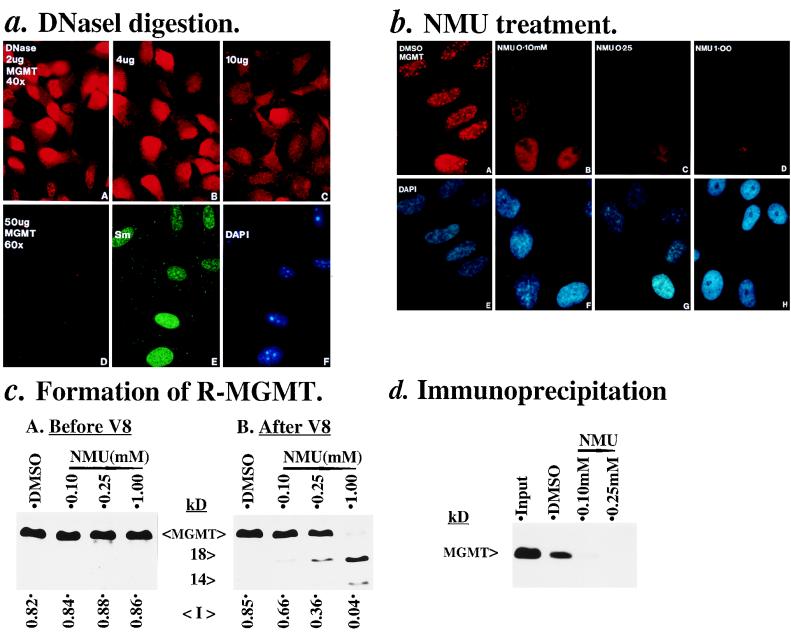

FIG. 6.

Sensitivity of MGMT speckles and formation of R-MGMT in cells treated with DNase I and NMU. (a) DNase I. Paraformaldehyde-fixed HeLa.CCL2B cells on coverslips were partially digested with 2, 4, 10, and 50 μg of DNase I per ml (1 h at room temperature) before immunostaining with MGMT.PAb (in red), anti-Sm (in green; 1:50,000), and DAPI (in blue). Pictures A, B, and C (original magnification, ×40) were taken under constant exposure of cells treated with 2, 4, and 10 μg of DNase I and stained with MGMT.PAb, whereas pictures D, E, and F (original magnification, ×60) are cells digested with 50 μg of DNase I and stained simultaneously with MGMT.PAb, anti-Sm, and DAPI, respectively. (b) NMU. MRC5 cells on coverslips were treated with DMSO (0.1% as vehicle) and 0.1, 0.25, and 1.0 mM NMU under serum-free conditions for 30 min at 37°C; cells were stained with MGMT.PAb and DAPI. (A and E) Control DMSO; (B and F) 0.1 mM NMU; (C and G) 0.25 mM NMU; (D and H) 1.0 mM NMU. (c) Protease V8-Western blot analysis of R-MGMT. MRC5 cells, from six 150-mm culture dishes per condition, were treated with NMU as described for panel b. Cell extracts were analyzed by protease V8-Western blot analysis. (A) Before protease V8; (B) after protease V8; I, intensities of the 21-kDa MGMT bands as quantified by densitometer. Conditions for Western blot analysis were as follows: 200 μg of protease V8-treated or untreated cellular proteins per lane was resolved on a sodium dodecyl sulfate–15% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gel, and MAb 2G1 (6 μg/ml) was used to visualize the 21-kDa MGMT and the protease V8 cleavage polypeptides (14 and 18 kDa) of R-MGMT by enhanced chemiluminescence (5 min). (d) Immunoprecipitation-Western blot analysis. Cell extracts (200 μg) from DMSO-treated cells (normal) and NMU-treated cells were immunoprecipitated with 1.5 μg of MGMT.PAb (19). The immunoprecipitated MGMTs were analyzed on a Western blot with MAb 2G1. Lane input is 200 μg of DMSO (normal)-treated cell extract without immunoprecipitation, whereas lanes DMSO (normal), 0.1 mM, and 0.25 mM NMU are MGMT.PAb immunoprecipitates of the corresponding cell extracts.

Rapid disappearance of MGMT speckles upon treatment with NMU.

To address the function of these MGMT speckles, we treated MRC5 cells briefly (30 min) with NMU, which produced the MGMT substrate 6MG in the DNA (26). At 0.1 mM NMU, photomicrographs of these treated cells in Fig. 6b showed a variety of staining patterns, generally diffused and poorly speckled MGMT stainings (picture B) and enlarged nuclei (picture F). Of the 200 cells examined, 82 cells showed poor MGMT speckles (less than 30% of MGMT speckles in the normal cells) and 118 cells exhibited only diffused MGMT staining. When the NMU treatment was increased to 0.25 and 1.0 mM, a loss of the nuclear MGMT staining (pictures C and D) and shrinkage of the nucleus (pictures G and H) were observed.

Disappearance of MGMT speckles upon NMU treatment is related to the formation of active-site alkylated MGMT (R-MGMT) at the transcription sites.

To understand whether the rapid disappearance of MGMT speckles upon NMU treatment was due to DNA damage and repair by MGMT, we analyzed the amount of R-MGMT formed in these NMU-treated cells and the ability of MGMT.PAb to immunoprecipitate active MGMT and R-MGMT. The R-MGMT was quantified by the protease V8-Western blot method (35), by which R-MGMT appeared as two distinctive 14- and 18-kDa polypeptides after cleavage by protease V8. Figure 6c, subpanel A, shows that the levels of total cellular MGMT remain constant (therefore, no degradation) in all samples. However, upon protease V8 treatment of these cell extracts, Fig. 6c, subpanel B, showed that increasing proportions of the 21-kDa MGMT were cleaved into two distinctive 14- and 18-kDa polypeptides characteristic of R-MGMT only in the NMU-treated samples. Thus, the loss of MGMT speckles might be related to the formation of R-MGMT. In the immunoprecipitation experiments (Fig. 6d), MGMT.PAb could precipitate only a subpopulation of MGMT in the normal cell extract (compare lanes labelled input and dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO] control), which might be the MGMT speckles located at the transcription sites. Apparently, MGMT.PAb also poorly precipitated MGMT in NMU-treated cell extracts (lanes labelled 0.1 and 0.25 mM), indicating its inability to recognize R-MGMT. Therefore, the disappearance of MGMT speckles upon NMU treatment could be a result of the failure of MGMT.PAb to stain R-MGMT formed from the repair of 6MG by the MGMT speckles at the transcription sites (see Discussion). By quantifying the intensities of the corresponding 21-kDa MGMT bands observed before (see “I” values in Fig. 6c, subpanel A) and after (Fig. 6c, subpanel B) protease V8 treatment, we estimated that ∼20% of active cellular MGMT was converted to R-MGMT during 0.1 mM NMU treatment. As MGMT speckles are largely lost at this NMU dosage (Fig. 6b, subpanel B), these R-MGMTs detected could represent the proportion of cellular MGMT present at active transcription sites.

DISCUSSION

Although immunostaining shows the intracellular location of proteins (16), this is dependent on the availability of the antibody recognition epitope, which can be masked due to the conformation of the antigen, the presence of interacting proteins, and modification during cell fixation. The results in Fig. 1b suggest that the speckled form of MGMT has exposed N (staining by P30) and C (by MGMT.PAb) termini but a buried central portion, which may be involved in stabilizing the speckled structure. The two epitopes also indicate different locations for active MGMT and R-MGMT in vivo since MGMT.PAb cannot stain or immunoprecipitate R-MGMT (Fig. 6b and d). These results suggested that, upon the repair of 6MG, MGMT undergoes a conformation change in vivo as indicated by the masking of these previously exposed N and C termini. This agrees with the specific cleavage of R-MGMT by protease V8 in vitro at glutamic acid residues E30 and E172 flanking the N and C termini of MGMT (35).

A salient finding in this study is, however, the demonstration of the hypersensitivity of MGMT speckles to both DNase I (Fig. 6a) and NMU (Fig. 6b). This result provides an important basis for TRC by MGMT in vivo. DNase I-hypersensitive sites are sites where nuclear DNAs are unwound and are undergoing active transcription or replication. These DNAs require constant repair surveillance because they are the target sites first hit by mutagens (see the introduction) such as NMU (Fig. 6b). Therefore, the hypersensitivity of MGMT speckles to DNase I is a direct reflection of MGMT speckles positioning at the sites that are preferentially damaged by NMU. Thus, the rapid disappearance of MGMT speckles, or the formation of R-MGMT as revealed by MGMT.PAb analysis, during low-dosage NMU treatment is the result of the preferential formation of 6MG residues in the transcription-active DNA by NMU and their subsequent repair by MGMT speckles. However, it is unclear whether the R-MGMT formed at the transcription sites remains closely associated with (or is detached from) these sites since none of the MGMT antibodies studied could stain MGMT as speckles after NMU treatment (data not shown).

Since 6MG does not arrest RNA polymerase during transcription (12), the mechanism behind MGMT repair of 6MG in transcriptionally active DNA is probably independent of the arrested RNA polymerase-DNA lesion complex-initiated TRC by NER (41, 42). This observation raises two related questions. First, why does MGMT become concentrated at active transcription sites? Second, why is TRC by NER orchestrated around RNA polymerase? A possible answer is that RNA polymerase contacts every transcribing base and that it exhibits a high degree of fidelity, i.e., it is arrested at DNA lesions with properties altered from those of the normal counterparts. Thus, RNA polymerase provides a mechanism for scanning DNA lesions at every transcribing base, the crucial initiation event in the repair process. By contrast, there is a failure of RNA polymerases to recognize O6-alkylguanine (6RG) in DNA since this lesion directs the misincorporation of uridine during transcription at these sites. This may arise from its similarity to adenine (being a substrate for adenosine deaminase [38]). Therefore, the presence of high levels of MGMT at the transcription site could compensate for a lack of an effective system, i.e., RNA polymerase, in scanning 6RG lesions during transcription. However, MGMT alone may not be sufficient to scan for and repair 6RG lesions in transcription-active DNA directly since it lacks DNA processivity. This suggests the presence of an accessory factor(s) for MGMT in active transcription sites, which might prevent the recognition of MGMT speckles by internal antibodies (Fig. 1b).

MGMT (21 kDa) and histone H1 (22 kDa) are similar in their sizes and DNA binding motifs (KAAR for MGMT [28] and the multiple KAAK domains for H1 [51]). Hence, MGMT could occupy the space vacated by H1, or the linker region, in the often H1-depleted transcriptionally competent nucleosomes (24). At this location, MGMT is in proximity to the histone octamer which contacts each residue in the DNA (analogous to the polymerases) for packaging them into the nucleosome (40). It appears to be an effective protection mechanism if the histones can serve as marker sites for coordinating DNA repair events because they modulate the activities of nucleosomal DNA by poising them for transcription (through the depletion of H1 [15, 36] and acetylation of H4 [23, 52]) which, inevitably, leads to the enhanced susceptibility of these exposed DNAs to damage (as discussed in the introduction). To effectively repair these damaged DNAs, a nucleosome-repair coupling mechanism would be appropriate and may be feasible according to two recent observations. First, the histone octamer remains intact and closely associates with the DNA during transcription across the nucleosome by RNA polymerase (2, 47). Second, RNA polymerase may actually be an immobilized component of the transcription factories (49). Transcription across the nucleosome would, therefore, follow the scooping of DNA (10) from the nucleosome towards RNA polymerase. This could occur through the sliding of the DNA around the octamer and provide a mechanism for scanning of the DNA by proteins (e.g., MGMT) associated with the octamer, possibly ahead of transcription by RNA polymerase. This should enable the repair of those DNA lesions, such as 6MG, that escape the editing mechanism of the polymerase.

Our genetic material is constantly under the influence of mutagens from our diet and environment (29). Although the etiologies of a few human cancers are linked to genetically predisposed defects in the coordination (by p53 [25]) and efficiency (by NER proteins [9]) of DNA repair, the in vivo basis for this remains to be established. Our results show some aspects of MGMT in protecting DNA from damage in vivo. First, it is enriched at active transcription sites (Fig. 5b) where it can respond rapidly to DNA damage (Fig. 6b). Second, its significant concentration at active transcription sites (∼20% of cellular MGMT [Fig. 6c]) may indicate the necessity for MGMT-mediated repair even under normal conditions. Third, its high level of expression coincides with the DNA unwinding activities during transcription and replication, suggesting that these important processes are directly coupled to MGMT surveillance (cell cycle experiments in Fig. 3). One would therefore predict that mutations in the amino acid residues associated with targeting MGMT to active transcription sites would increase mutations in transcriptionally active genes and, therefore, enhance the susceptibility of cells to the toxic and mutagenic effects of environmental alkylating carcinogens, such as N,N-dimethylnitrosamines. Similarly, the ineffectiveness of chemotherapeutic regimens involving alkylating agents, such as bis-chloroethylnitrosourea (which produces the DNA cross-linking intermediate O6-chloroethylguanine in DNA [13]), towards mer+ tumors could be related to the targeted protection afforded by MGMT being enriched at sites of unwound chromatins, which are potential targets for these drugs (see NMU study in Fig. 6b and c).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank E. Manser for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work received support from the National Science and Technology Board of Singapore.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abott P, Saffhill R. DNA synthesis with methylated poly (dC · dG) templates; evidence for a competitive nature of miscoding by O6-methylguanine. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1979;567:51–61. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(79)90125-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams C C, Workman J L. Nucleosome displacement in transcription. Cell. 1993;72:305–308. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90109-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arrand J E, Murray A M. Benzpyrene groups bind preferentially to DNA of active chromatin in human lung cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1982;10:1547–1555. doi: 10.1093/nar/10.5.1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ayi T C, Loh K C, Ali R B, Li B F L. Intracellular localisation of human repair enzyme, O6-methylguanine methyltransferase, by antibodies and its importance. Cancer Res. 1992;52:6423–6430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bachmann M, Schroder H C, Falke D, Muller W E G. Immunofluorescence microscopy. In: Peters R, editor. Methods of investigating nucleo-cytoplasmic transport of RNA. London, United Kingdom: Academic Press; 1988. pp. 33–139. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baskin Y. Mapping the cell’s nucleus. Science. 1995;268:1564–1565. doi: 10.1126/science.7777854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bodell W J. Nonuniform distribution of DNA repair in chromatin after treatment with methyl methanesulphonate. Nucleic Acids Res. 1977;4:2619–2623. doi: 10.1093/nar/4.8.2619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Capecchi M R. High efficiency transformation by direct microinjection of DNA into cultured mammalian cells. Cell. 1980;22:479–488. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90358-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cleaver J E, Kraemer K H. Xerodema pigmentosum. In: Scriver C A, Beaudet A L, Sly W S, Vale D, editors. The metabolic basis of inherited disease. 6th ed. Vol. 2. New York, N.Y: McGraw-Hill; 1989. pp. 2849–2971. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coverley D, Laskey R A. Regulation of eukaryotic DNA replication. Annu Rev Biochem. 1994;63:745–776. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.003525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Engelward B P, Dreslin A, Christensen J, Huszar D, Kurahara C, Samson L. Repair-deficient 3-methyladenine DNA glycosylase homozygous mutant mouse cells have increased sensitivity to alkylation-induced chromosome damage and cell killing. EMBO J. 1996;15:945–952. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gerchman L L, Ludlum D B. The properties of O6-methylguanine in template for RNA polymerase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1973;308:310–316. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(73)90160-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gonzaga P E, Potter P M, Niu T Q, Yu G, Ludlum D B, Rafferty J A, Margison G P, Brent T P. Identification of the cross-link between human O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase and chloroethylnitrosourea-treated DNA. Cancer Res. 1992;52:6052–6058. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Graessman M, Graessman A. Microinjection of tissue culture cells. Methods Enzymol. 1983;101:482–492. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(83)01033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gross D S, Garrard T W. Nuclease hypersensitive sites in chromatin. Annu Rev Biochem. 1988;57:159–197. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.57.070188.001111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harlow E, Lane D. Antibodies: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hassan A B, Cook P R. Visualisation of replication sites in unfixed cells. J Cell Sci. 1993;105:541–550. doi: 10.1242/jcs.105.2.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hassan A B, Errington R J, White N S, Jackson D A, Cook P R. Replication and transcription sites are colocalised in human cells. J Cell Sci. 1994;107:425–434. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.2.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hozak P, Jackson D A, Cook P R. Replication factories and nuclear bodies: the ultrastructural characterisation of replication sites during the cell cycle. J Cell Sci. 1994;107:2191–2202. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.8.2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang S, Spector D L. U1 and U2 small nuclear RNAs are present in nuclear speckles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:305–308. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.1.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ito T, Nakamura T, Maki H, Sekiguchi M. Roles of transcription and repair in alkylating agent mutagenesis. Mutat Res (DNA Repair) 1994;314:273–285. doi: 10.1016/0921-8777(94)90071-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jackson D A, Hassan A B, Errington R J, Cook P R. Visualisation of focal sites of transcription within human nuclei. EMBO J. 1993;12:1059–1065. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05747.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jeppesen P, Turner B M. The inactive X chromosome in female mammals is distinguished by a lack of histone H4 acetylation, a cytogenetic marker for gene expression. Cell. 1994;74:281–290. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90419-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kamakaka R T, Thomas J O. Chromatin structure of transcriptionally competent and repressed genes. EMBO J. 1990;9:3997–4006. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07621.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kastan M B, Zhan Q, El-Deiry W S, Carrier F, Jacks T, Walsh W V, Plunkett B S, Vogelstein B, Fornace A J., Jr A mammalian cell cycle checkpoint pathway utilizing p53 and GADD45 is defective in ataxia-telangiectasia. Cell. 1992;71:587–597. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90593-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lawley P D. Monograph 182. In: Glover P L, editor. Chemical carcinogens and DNA. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press, Inc.; 1979. pp. 325–484. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leonhardt H, Page A W, Weier H-U, Bestor T H. A targeting sequence directs DNA methyltransferase to sites of DNA replication in mammalian nuclei. Cell. 1992;71:865–873. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90561-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lim A, Li B F L. The nuclear targetting and nuclear retention properties of a DNA repair protein O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase are both required for its nuclear localization: the possible implications. EMBO J. 1996;15:4050–4060. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lindahl T. Instability and decay of the primary structure of DNA. Nature. 1993;362:709–715. doi: 10.1038/362709a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Loechler E L, Green C L, Essigmann J M. In vivo mutagenesis by O6-methylguanine built into a unique site in viral genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:6271–6275. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.20.6271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Loveless A. Possible relevance of O6-alkylation of deoxyguanosine to the mutagenicity and carcinogenicity of nitrosamines and nitrosamides. Nature. 1969;223:206–207. doi: 10.1038/223206a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mellon I, Hanawalt P C. Induction of the Escherichia coli lactose operon selectively increases repair of its transcribed DNA strand. Nature. 1989;342:95–98. doi: 10.1038/342095a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mellon I, Rajpal D K, Koi M, Boland C R, Champe G N. Transcription-coupled repair deficiency and mutations in human mismatch repair genes. Science. 1996;272:557–560. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5261.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mellon I, Spivak G, Hanawalt P C. Selective removal of transcription-blocking DNA damage from the transcribed strand of mammalian DHFR gene. Cell. 1987;51:241–249. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90151-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oh H-K, Teo A, Ali R B, Lim A, Ayi T C, Yarosh D B, Li B F L. Conformation change in human DNA repair enzyme O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase upon alkylation of its active site by SN1 (indirect-acting) and SN2 (direct-acting) alkylating agents: breaking a “salt-link.”. Biochemistry. 1996;35:12259–12266. doi: 10.1021/bi9603635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paranjape S M, Kamakaka R T, Kadonaga J T. Role of chromatin structure in the regulation of transcription by RNA polymerase II. Annu Rev Biochem. 1994;63:265–297. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.001405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pegg A E. Mammalian O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase: regulation and importance in response to alkylating carcinogens and therapeutic agents. Cancer Res. 1990;50:6119–6129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pegg A E, Swann P F. Metabolism of O6-alkylguanosines and their effects on removal of O6-methylguanine from rat liver DNA. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1979;565:241–252. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(79)90202-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pines J, Hunter T. Human cyclins A and B1 are differentially located in the cell and undergo cell cycle-dependent nuclear transport. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:1–17. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pruss D, Bartholomew B, Persinger J, Hayes J, Arents G, Moudrianakis E N, Wolffe A P. An asymmetric model for nucleosome: a binding site for linker histone inside the DNA gyres. Science. 1996;274:614–617. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5287.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Selby C P, Sancar A. Molecular mechanism of transcription-repair coupling. Science. 1993;260:53–58. doi: 10.1126/science.8465200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Selby C P, Sancar A. Mechanism of transcription-repair coupling and mutation frequency decline. Microbiol Rev. 1994;58:317–329. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.3.317-329.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Selby C P, Sancar A. Human transcription-repair coupling factor CSB/ERCC6 is a DNA-stimulated ATPase but is not a helicase and does not disrupt the ternary transcription complex of stalled RNA polymerase II. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:1885–1890. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.3.1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shi Y B, Gamper H, Hearst J E. Interaction of T7 RNA polymerase with DNA in an elongation complex arrested at a specific psoralen adduct. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:527–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spector D L. Macromolecular domains within the cell nucleus. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1993;9:265–315. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.09.110193.001405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spector D L, Fu X-D, Maniatis T. Association between distinct pre-mRNA splicing components and the cell nucleus. EMBO J. 1991;10:3467–3481. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04911.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Studitsky V M, Clark D J, Felsenfeld G. A histone octamer can step round a transcribing polymerase without leaving the template. Cell. 1994;76:371–382. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90343-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thomale J, Hochleitner K, Rajewsky M F. Differential formation and repair of the mutagenic DNA alkylation product O6-ethylguanine in transcribed and nontranscribed genes of the rat. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:1681–1686. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Traub P, Shoeman R L. Intermediate filament proteins: cytoskeletal elements with gene-regulatory functions? Int Rev Cytol. 1994;154:1–103. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)62198-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.van Gool A J, van der Horst G T J, Hoeijmakers J H J. Cockayne syndrome: defective repair of transcription. EMBO J. 1997;16:4155–4162. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.14.4155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wells D, McBride C. A comprehensive compilation and alignment of histones and histone genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:r311–r346. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.suppl.r311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wolffe A P. Transcription: in tune with histones. Cell. 1994;77:13–16. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90229-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xing Y, Johnson C V, Dobner P R, Lawrence J B. Higher level organisation of individual gene transcription and RNA splicing. Science. 1993;259:1326–1330. doi: 10.1126/science.8446901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]