Abstract

It is well-established that sleep and behavior are interrelated. Although studies have investigated this association, not many have evaluated the bidirectional relationship between the two. To our knowledge this is the first systematic review providing a comprehensive analysis of a reciprocal relationship between sleep and externalizing behavior. Five databases (PsycINFO, PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar) were utilized to yield a total of 3,762 studies of which 20 eligible studies, empirical articles examining bidirectionality of sleep and externalizing behavior, were selected for analysis. According to the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis, the varying methodological approaches used in these studies were analyzed and synthesized, including examining differences and similarities in outcomes between distinct study designs (longitudinal vs cross-sectional), sleep measures (objective vs subjective vs a combination of both), informants (parents, self-report, teachers), and recruited participants (clinical, subclinical and typical populations). The assessment of risk of bias and quality of studies was guided by the instruments employed in research on sleep and behavior in the past. This review establishes that a bidirectional relationship between sleep problems and externalizing behavior clearly exists, and identifies limitations in the existing literature. Furthermore, the importance of early interventions that target both externalizing behaviors and sleep problems is highlighted as a potentially effective way of breaking the sleep-externalizing behavior relationship. Nonetheless, causality cannot be claimed until more trials that manipulate sleep and evaluate changes in externalizing behavior are conducted.

Keywords: Sleep, Externalizing behavior, Bidirectionality, Systematic review, Sleep disturbances

1. Introduction

It is well established that sleep problems are correlated with externalizing behavior problems. 1-3 A growing number of studies are beginning to assess the directionality of this relationship in order to better understand whether sleep problems lead to externalizing problems or vice versa. 4-7 Examining the nature of this dynamic relationship may enable clinicians to improve interventions for both sleep and behavioral problems. For example, currently, interventions for externalizing problems rarely focus on improving sleep quality and quantity as a method for potentially improving externalizing problems. Knowledge that sleep problems may contribute to or exacerbate externalizing problems could be helpful in informing the development of such interventions. 8,9

In this systematic review, we aim to analyze the available studies on the bidirectional relationship between sleep (sleep duration, sleep quality, sleep/wake problems, insomnia) and externalizing behavior (aggression, hyperactivity, delinquency, impulsivity, attentional problems). We aim to provide initial answers to the following research questions: Does externalizing behavior cause sleep problems? Do sleep problems cause externalizing behavior? Or is the relationship reciprocal, with sleep problems predisposing to externalizing behavior which then feeds into further sleep problems? Could it also be that externalizing behaviors predispose to sleep problems which then feed further in more externalizing problems? Alternatively, is any bidirectional relationship confounded by other factors? Furthermore, do different sleep measures (objective vs subjective vs a combination of both) influence study outcomes? Finally, what are the limitations of existing studies, and how may these gaps be addressed in future research?

2. Methods

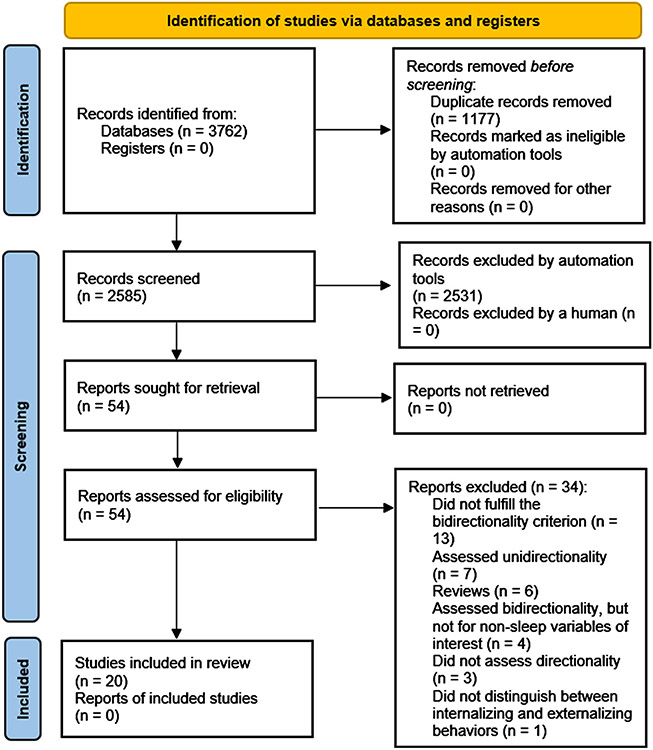

This systematic review, as illustrated in Fig. 1 and Table S1, was performed in compliance with PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines 10, 11 in order to provide valid reporting in this systematic review (see Table S3 and Table S4).

Fig. 1.

Bidirectionality of sleep and externalizing behavior: PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the studies selection process.11.

2.1. Search strategy

Five search engines, Google Scholar, Web of Science, PsycINFO, PubMed, and Scopus were used to identify articles eligible for inclusion; the search was concluded on 06/09/2022. In these databases, searches were conducted with an emphasis placed on a variety of different terms related to sleep and externalizing behaviors. A sample search was: ((bidirectional) OR (reciprocal) OR (two-way)) AND ((sleep) OR (insomnia) OR (hypersomnia) OR (sleep/waking disorder) OR (bedtime resistance) OR (sleep quantity) OR (sleep duration) OR (sleep quality) OR (sleep difficulty) OR (sleep disturbance)) AND ((behavior) OR (conduct) OR (aggression) OR (inattention) OR (hyperactivity) OR (opposition) OR (impulsivity)). Furthermore, certain database search functions were used to enhance the sensitivity and specificity of the search. For example, Google Scholar searches were refined by the “with at least one of the words” function, while searches in PubMed were accompanied by additional MeSH terms, such as “Sleep”, “Sleep disorders”, “Insomnia”, “Actigraphy”, “Polysomnography”, “Externalizing behavior”, “Hyperactivity”, “Impulsivity”, and “Aggression”. The precise search strategy is explicated in Table S1. No time restriction for publication dates of selected studies was introduced. Backward and forward citation searches were performed for studies identified as potentially relevant after initial assessment to maximize the scope of this systematic review.

2.2. Inclusion criteria

2.2.1. Types of studies

Observational and experimental studies on both community and clinical human populations were a target of database searches. Cross-sectional and longitudinal research for populations of all ages were taken into consideration. Cross-sectional studies were qualified for inclusion due to their advantageous methodology: they frequently utilized objective sleep measures, which allowed for a comprehensive and comparative view on the subject, and considerations regarding subjective versus objective sleep measures in the context of the bidirectionality of sleep and externalizing behavior were a major component of this systematic review. All non-empirical scholarly sources (such as systematic reviews, comprehensive reviews, commentaries, editorials, and narrative pieces) as well as case studies were excluded.

2.2.2. Type of predictor and outcome

Given the presumed reciprocal nature of the empirical relationship under scrutiny in this review, the type of exposure and the type of outcome had to be considered simultaneously within inclusion criteria. In order to be included, studies needed to directly assess sleep, externalizing behavior, and their bidirectional association. Studies that implemented either objective (e.g., actigraphy, polysomnography) or subjective (e.g., self-reports, parental reports) sleep measures qualified for inclusion. Nonetheless, studies whose objective was not to examine the reciprocal nature of the relationship were excluded. For example, studies whose key aim was not to investigate externalizing behavior as both cause and outcome in the context of sleep disturbances, even when they may have included behavior variables, were not incorporated.

Externalizing behavior was defined as a behavior directed towards the outer environment, which is in accordance with the classical understanding of this term in the field. 12 All three typical classes of externalizing behavior (aggression, hyperactivity, delinquency) were targeted in database searching. 13 Synonymous terms and behaviors closely associated with the aforementioned three categories (such as impulsivity, antisocial traits, conduct problems, attention problems, disruptive behaviors) were also taken into consideration. Studies that were suitable for inclusion included those that assessed reciprocity between sleep and overall externalizing behaviors and also those that focused on the bidirectionality between a specific aspect of sleep (such as insomnia, hypersomnia, and sleep/wake problems) and a specific aspect of externalizing behavior (e.g., attentional difficulties, impulsivity) or a given mental disorder (e.g., conduct disorder, ODD, antisocial personality disorder).

2.2.3. Study selection

Articles examined in this systematic review were located with the use of electronic databases. Duplicates were removed, after which remaining studies were gauged in terms of relevance to the paper. Subsequently, titles and abstracts were analyzed and empirical sources classified as possibly admissible were assessed for eligibility in accordance with the inclusion criteria. Additional screening was employed for potentially eligible articles within references of publications identified through database searches. All of the above-mentioned procedures were conducted independently by the first and the second author in order to maximally decrease the risk of bias.

2.2.4. Database searching

Databases searching yielded a total of 3755 studies. 7 additional sources were identified through screening the references of publications that were identified with the use of search engines, which translated into a total of 3762 studies. Having analyzed titles and abstracts against the inclusion criteria, we initially identified 54 studies as possibly relevant sources. Thirteen studies did not fulfill the bidirectionality inclusion criterion; 14-26 seven publications assessed unidirectional relationships, 27-33 six were reviews, 6, 34-38 four assessed bidirectionality but not for non-sleep variables of interest,39-42 three did not assess directionality, 43-45 and one study did not distinguish between internalizing and externalizing behavior. 46 Overall, 34 studies were excluded, resulting in 20 studies for inclusion.

2.2.5. Data extraction

As shown in Tables 1 and 2 , the following data were obtained from the eligible studies: study type, authors, study design and setting, sample characteristics, sleep measures, behavior measures, covariates, major findings, strengths, and limitations. Results of the quality assessment of the selected studies were collected in Table 3 and Table S2. Information regarding directionality of the reported associations between sleep and externalizing behaviors, informants for the externalizing behaviors variable, and sleep measure (objective/subjective) were gathered (see Table 4).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies on the bidirectionality of sleep and behavior in human subjects, ordered by study design.

| Study Type | Authors | Age at a last follow-up (childhood, adolescence, adulthood) |

Country and Sample |

Sample Characteristics1 |

Sleep Measures | Externalizing Behavior Measures |

Covariates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LONGITUDINAL | S1: Conway et al. (2017) 50 | Childhood | USA NICHD-SECCYD2 Toddler population with sleep and behavior problems |

n = 1001 Age 24–36 months 48.85% female Two waves of data collection |

Mother-reported CBCL3 | Mother-reported CBCL (withdrawn, aggressive, and destructive behaviors subscales) | Age, gender, ethnicity, maternal years of education, age, and depressive symptoms, family income, number of children at home |

| S2: Steinsbekk & Wichstrøm (2015) 2 | Childhood | Norway Child population who regularly attended community health check-ups |

Baseline (2007/2008): n = 995 Age 4 years Mean age=4.4 50.9% female Follow-up (2009/2010): n = 775 Age 6 years Mean age=6.7 49.9% female Two waves of data collection |

Parent-reported PAPA4 (investigating sleep disorders) |

DSM-IV5 symptom counts obtained with the use of PAPA interview completed by parents | Age, gender, sleep disorders at age of 4 years, initial level of psychiatric symptoms, parental gender, occupation, marital status, and cohabitation | |

| S3: Williams et al. (2017) 9 | Childhood | Australia Growing Up in Australia, the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC) Child community sample |

n = 4109 Age 0–9 years 49% female Five waves of data collection |

Four mother-reported items from the Infant Sleep Study | Four mother-reported items from The Infant Sleep Study | Age, gender, ethnicity, number of siblings, language spoken at home, parents’ age, parents’ education, parents’ presence at home | |

| S4: Kouros & El-Sheikh (2015) 51 | Childhood | USA Child Regulation Study Child community sample |

n = 142 Mean age=10.69 57% female Two waves of data collection |

Octagonal Basic Motionloggers Actigraphy |

Mother-reported five-point semantic differential scale Parent-reported Personality Inventory for Children |

Age, gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, day of the week (workday vs weekend), puberty, parental employment, BMI6 | |

| S5: Mulraney et al. (2016) 52 | Childhood | Australia Children with ADHD7 selected from pediatric clinics |

n = 270 Age 5–13 years Mean age=10.1 14.1% female Three waves of data collection |

Parent-reported CSHQ8 |

Parent-reported SDQ9 |

Age, gender, medication for ADHD, ASD10, ADHD subtype, primary caregiver’s age, primary caregiver’s education | |

| S6: Liu et al. (2021) 53 | Childhood | China China Jintan Cohort Study Child community sample |

Baseline (2004): n = 1209 Mean age=6.18 45.7% female Follow-up (2009): n = 775 Mean age= 11.5 48% female Two waves of data collection |

Parent-reported CBCL Child-reported YSR11 |

Parent-reported CBCL Teacher-reported TRF12 Child-reported YSR |

Age, gender, parents’ education, attended school | |

| S7: Quach et al. (2018) 54 | Adolescence | Australia Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC) Child/early adolescent community sample |

Baseline (2004): n = 4983 Age 4–5 years Mean age=4.7 Follow-up (2012): n = 3956 Age 12–13 years 49% female Five waves of data collection |

Parent-reported five items list (4 “yes/no” items, 1 dichotomized item assessing the extent of sleeping problems) | Parent-reported SDQ including hyperactivity/inattention and conduct problems subscales |

Age, gender, ethnicity, number of siblings, language spoken at home, parents’ age, parents’ education, parents’ presence at home | |

| S8: Williamson et al. (2021) 55 | Adolescence | Australia Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC) Child/early adolescent community sample |

Baseline (2004): n = 4983 Age 4–5 years Follow-up (2012): n = 3682 Age 12–13 years 49% female Five waves of data collection |

Parent-reported five items list (4 “yes/no” items, 1 dichotomized item assessing the extent of sleeping problems) | Parent-reported SDQ including hyperactivity/inattention and conduct problems subscales |

Age, gender, ethnicity, number of siblings, language spoken at home, parents’ age, parents’ education, parents’ presence at home | |

| S9: Kelly & El-Sheikh (2014) 56 | Adolescence | USA Child Regulation Study Child community sample |

Baseline (2003–2004): n = 176 Mean age=8.68 55.7% female Follow-up (2009): n = 113 Mean age= 13.6 Three waves of data collection |

Child-reported Sleep Habits Survey The 10-item Sleep–Wake Problems scale Actigraphy |

Parent-reported Personality Inventory for Children (Externalizing scale) |

Age, gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, BMI, puberty, season of the year, daylight hours at the time of measurement | |

| S10: Bauducco et al. (2019) 57 | Adolescence | Sweden Adolescent community sample |

Baseline (2014): n = 2767 Age 12–15 years Mean age=13.7 47.6% female Follow-up (2016): n = 1982 Three waves of data collection |

Self-reported bed time questions from the School Sleep Habits Survey Child-reported ISI13 | UPSS14 impulsive behavior scale (the urgency subscale) | Age, gender | |

| S11: Pieters et al. (2015) 58 | Adolescence | Netherlands Adolescent community sample |

n = 555 Age 11–16 years Mean age=13.96 52.25% female Two waves of data collection |

Child-reported ASWS15 Child-reported ASHS16 |

Child-reported SDQ | Age, gender, ethnicity, substance use, puberty, education | |

| S12: Wang et al. (2016) 59 | Adolescence | Australia Western Australian Pregnancy Cohort (Raine) Study Child/early adolescent community sample |

Baseline (1989): n = 2868 Assessed at birth 49.3% female Follow-up (2003): n = 1774 Age 14 Effective sample size: n = 1993 48.6% female Four waves of data collection |

Parent-reported CBCL | Parent-reported CBCL Child-reported YSR |

Age, gender, different developmental trajectories of sleep problems | |

| S13: Gregory & O’Connor (2002) 60 | Adolescence | USA Colorado Adoption Project Children population in adoptive and non-adoptive families |

n = 490 Age 4–15 years 46.3% female Two waves of data collection |

Parent-reported CBCL | Parent-reported CBCL | Age, gender, adoptive status | |

| S14: Shanahan et al. (2014) 61 | Adolescence | USA The Great Smoky Mountains Study Children population with certain scores on the CBCL externalizing scale |

n = 1420 Age 9–16 years Four waves of data collection |

Parent-reported and children-reported Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment |

Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment |

Age, gender, puberty, ethnicity, comorbidities | |

| S15: Kortesoja et al. (2020) 62 | Adolescence | Finland Adolescent community sample |

Baseline (2011): n = 8834 Mean age=13 51.1% female Follow-up (2016): n = 3712 Mean age= 17 50.2% female Three waves of data collection |

Self-reported sleep duration (2 questions about sleep and wake-up times) Self-reported sleep problems (1 question on difficulties falling asleep/waking up at night) |

Self-reported SDQ | Age, gender, mothers’ education (socioeconomic status) | |

| S16: Vermeulen et al. (2021) 63 | Adulthood | Netherlands Adolescent twin population |

n = 12,803 2148 MZ pairs 3358 DZ pairs Age 13–20 years 58% female Two waves of data collection |

Self-reported 3-point scale gaging habitual sleep duration Child-reported YSR |

Child-reported YSR (subscales for externalizing behaviors) | Age, gender, family clustering | |

| S17: Wang et al. (2021) 64 | Adolescents | China Adolescent population after experiencing an earthquake | Baseline (2009): n = 1275 Mean age=15.96 56.2% female Follow-up (2010): n = 927 Mean age= 16.92 57.2% female Two waves of data collection |

Self-reported PSQI17 |

Self-reported SDQ | Age, gender, earthquake exposure | |

| S18: Kelly et al., (2022) 65 | Adolescents | USA Family Stress and Youth Development Study Adolescent community sample |

Baseline (2012): n = 246 Mean age=15.79 53% female Follow-up (2015): n = 215 Mean age= 17.7 55% female Three waves of data collection |

Actigraphy Self-reported School Sleep Habits Survey | Parent-reported Personality Inventory for Children |

Age, gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic status | |

| CROSS-SECTIONAL | S19: Van Dyk et al. (2016) 66 | Childhood | USA Children with emotional and behavioral problems receiving outpatient treatment |

n = 25 Age 6–11 years Mean age=8.72 36% female |

Child-reported PDSS18 Parent-reported CSHQ Actigraph wrist watches supplemented by Actisleep software Parent-reported total daily sleep Child-reported sleep quality on a five-point Likert-type scale |

Child-reported BASC-2119 Parent-reported CBCL Parent-reported BPM20 |

Age, gender, ethnicity, psychotropic medication |

| S20: Yaugher & Alexander (2015)67 | Adulthood | USA Undergraduates |

n = 386 Age 18–27 years Mean age=18.59 58% female |

Self-reported PSQI Accelerometer | Self-reported BIS-1121 Self-reported TriPM22 Self-reported PAI23 |

Age, gender, ethnicity, sleep medication |

Baseline and final follow-up included in the study.

National Institute of Child Health and Development-Study of Early Childcare and Youth Development.

Child Behavior Checklist.

Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment.

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition.

Body Mass Index.

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder.

Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire.

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire.

Autism Spectrum Disorder.

Youth Self-Report.

Teacher’s Report Form.

Insomnia Severity Index.

Urgency, Premeditation, Perseverance, Sensation seeking.

Adolescent Sleep-Wake Scale.

Adolescent Sleep Hygiene Scale.

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index.

Pediatric Daytime Sleepiness Scale.

Behavior Assessment System for Children, Second Edition.

Brief Problems Monitor.

Barratt Impulsiveness Scale.

Triarchic Psychopathy Measure.

Personality Assessment Inventory.

Table 2.

Major findings, strengths, and limitations of the included studies on the bidirectionality of sleep and behavior in human subjects, ordered by study design.

| Authors | Major Findings | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| S1: Conway et al. (2017) (Longitudinal) | One-way association, in boys but not girls, between externalizing behavior and increase in bedtime resistance was observed. In boys with high externalizing behaviors, bedtime resistance was observed to grow. Bidirectionality between trouble getting to sleep and externalizing behaviors was not significant. |

Large sample size. Concentration on distinct sleep disturbances rather than general sleep difficulties. |

Results might be non-generalizable to groups other than European Americans. Non-clinical population was assessed – described relationships between measured variables might be different for toddlers with sleep disorders. Reliance on mothers’ reports. No objective sleep measures. |

| S2: Steinsbekk & Wichstrøm (2015) (Longitudinal) | ADHD symptoms were unidirectionally linked with increased risk of insomnia. Insomnia and oppositional-defiant disorder were reciprocally related. Insomnia unidirectionally predicted conduct disorder. |

Large sample size. Focus on distinct sleep disturbances and distinct mental disorders associated with them. Use of longitudinal data. |

Results might be non-generalizable to other countries than Norway due to different frequencies of psychiatric disorders. Symptom counts were used instead of diagnoses of mental disorders for power reasons. Use of parent-reported measures. |

| S3: Williams et al. (2017) (Longitudinal) | Bidirectional link between self-regulation and sleep was observed. Authors discovered that the higher attentional regulation at 2–3 years old, the smaller the number of sleep difficulties two years later. Attentional dysregulation was indirectly linked to sleep-related issues: lower attentional regulation for 4–5 year-olds was related to emotional regulation issues at 6–7 years old which, in turn, was associated with higher levels of sleep behavioral problems two years afterwards. Behavioral sleep problems result in emotional regulation which, subsequently, affects attentional regulation and further impacts sleep problems. |

Large representative sample size. Use of longitudinal data. |

Use of maternal reported measures. Non-clinical population was assessed; described relationships between measured variables might be different for individuals with psychiatric diagnoses. |

| S4: Kouros & El-Sheikh (2015) (Longitudinal) | Children’s daily mood was discovered to act as a mediator between bad sleep quality and externalizing as well as internalizing problems. Bidirectional link between sleep problems and externalizing behaviors was present; daily negative moods may connect sleep with behavioral outcomes. Potentially bigger significance of sleep quality rather than sleep duration in the context of negative behavioral effects was observed. |

Ethnically and socially diverse sample. Use of objective sleep measures. |

Reliance on self-reported and parent-reported measures. Gained insights were based on correlational data which means that other variables unaccounted for by the authors could have contributed to the observed results. |

| S5: Mulraney et al. (2016) (Longitudinal) | Bidirectionality between sleep problems and externalizing behaviors was not seen in children with ADHD, while weak bidirectionality between sleep problems and internalizing behaviors was observed. State of sleep, behavior, and emotions was found to be consistent over one year. |

Participants representing diverse cultural and social groups. Assessment of sleep and behavior through extensive methods with high validity. |

Restricted variability of behavior and sleep difficulties levels in the participants. A period of one year may be too short to accurately gage bidirectionality of sleep and externalizing symptoms. Use of caregiver-reported measures. No data on sleep medication taken by children were gathered. |

| S6: Liu et al. (2021) (Longitudinal) | Sleep and behavioral problems were stable over time. Mother-reported sleep difficulties of their children at age 6 predicted subsequent externalizing and internalizing behavior reported by the youth at 11.5 years old (but did not predict the same variables gauged by mothers and teachers). Issues pertaining to externalizing, attention, and internalizing functioning assessed by teachers and mothers when children were 6 were associated with mother-rated and (or) self-rated sleep difficulties at 11.5 years old. |

Large sample size. Implementation of valid and reliable measures. Use of assessments which included multiple raters. |

No objective sleep measures. Lack of information about specific sleep disturbances as cause and effect of behavioral problems. Certain variables (demographic, psychological) were considerably different among participants that took part and didn’t take part in the follow-up. |

| S7: Quach et al. (2018) (Longitudinal) | In 6–7 year-olds, sleep problems predicted externalizing behaviors when they were 8–9 years old (and at no other age). Externalizing symptoms were a predictor for later sleep problems and internalizing symptoms, whereas internalizing problems were not predictive of future externalizing difficulties. The presence of intertwined sleep problems, externalizing problems, and internalizing symptoms was stable over time, suggesting that externalizing symptoms may act as a direct contributor to internalizing problems and an indirect contributor leading to them via sleep disturbances. |

Large, representative sample. Implementation of invariance testing of the sleep problem factor. |

Exclusively parent-reported measures were used. No objective sleep measures. Restricted ethnicity of participants. |

| S8: Williamson et al. (2021) (Longitudinal) | Bidirectionality between externalizing behaviors and behavior sleep problems was observed only in early childhood (and not in later childhood). Externalizing behaviors predicted behavioral sleep problems more strongly than vice versa. |

Access to data from a long period of time, including crucial moments in children’s development. Large sample size. |

Lack of participants suffering from chronic medical conditions; non-generalizable for this population. No objective sleep measures. Restricted ethnicity of participants. |

| S9: Kelly & El-Sheikh (2014) (Longitudinal) | Various aspects of sleep (sleep/wake problems, sleep duration, sleep quality) were predictors for long-term externalizing symptoms. On the other hand, although to a smaller extent, externalizing symptoms predicted later sleep problems which evidenced bidirectionality of this association. Sleep predicts and is predicted by adjustment of a child. Externalizing problems were associated with subsequent bigger sleep/wake problems, whereas depression and anxiety had different outcomes: shorter sleep duration as well as worse sleep quality and worse sleep respectively. |

Implementation of objective sleep measures. Measuring different facets of sleep and their distinct psychological impact. |

Use of self-reports. Different times of assessment (school year and summer vacations) could have an impact on sleep durations due to different sleep schedules characteristic for these times of the year. |

| S10: Bauducco et al. (2019) (Longitudinal) | Association between sleep quality/sleep quantity and impulsive behaviors were found out to be bidirectional. Reciprocal links were stronger for insomnia and impulsive behavior in comparison to sleep duration and impulsive behavior. |

Large, community-based sample. Use of longitudinal data. |

Conclusions based on one measure of impulsive behaviors. Reliance on self-reports for sleep quantity and quality. No objective sleep measures. |

| S11: Pieters et al. (2015) (Longitudinal) | Sleep disturbances were predictive of subsequent externalizing, internalizing, and substance use problems, whereas the converse relationship was not significant (apart from alcohol use). | Large sample size. Application of valid and reliable measures. |

Use of only self-reported measures. Environmental factors were not examined. |

| S12: Wang et al. (2016) (Longitudinal) | The Troubled Sleepers group were discovered to have far higher levels of behavioral problems (attention, aggression) at age 17 in comparison to Normal Sleepers; at the same time, their emotional problems (anxiety, depression) were of a similar level. Bidirectionality of sleep disturbances and behavioral difficulties was observed, whereas emotional problems were unidirectionally predictive of later sleep problems. |

Large sample size. Conclusions based on longitudinal data. Use of growth mixture modeling which made identification of various trajectories of sleep difficulties possible. Use of valid and reliable measures. |

Non-generalizability to distinct sleep disorders caused by the assessment of general sleep problems. Use of self-reported and parent-reported measures. No objective sleep measures. |

| S13: Gregory & O’Connor (2002) (Longitudinal) | Early life sleep difficulties were predictive of attention issues and aggression 11 years later; however, the reverse is only true for attention problems predicting subsequent sleep disturbances. | Large sample size. Use of longitudinal data. |

Sample was not ethnically diverse. No objective sleep measures. Exclusive reliance on parental reports. |

| S14: Shanahan et al. (2014) (Longitudinal) | Longitudinal bidirectionality between sleep problems and oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) was observed, with sleep problems being a stronger predictor for ODD symptoms than vice versa. When comorbidity was taken into account, conduct disorder and ADHD were not predicted by sleep difficulties anymore. Once comorbidity was controlled for, the majority of reciprocal links between sleep problems and mental disorders gathered around generalized anxiety disorder, depression, and ODD; this led to a hypothesis that irritability, a common denominator of these psychopathologies, might be a reason for that particular bidirectionality. |

Assessment of the relationship between sleep and distinct types of mental disorder as well as their comorbidities. | Population from a restricted geographical area. Sample was not ethnically diverse. No objective sleep measures. |

| S15: Kortesoja et al. (2020) (Longitudinal) | Short sleep duration predicted subsequent emotional and behavioral problems more strongly than the converse. Larger behavioral and emotional problems were more predictive of sleep problems than vice versa. Self-reported sleep problems and externalizing behaviors (hyperactivity, conduct problems) were found to be bidirectional. |

Large sample size. Conclusions based on longitudinal data. |

Use of self-reported measures. No objective sleep measures. |

| S16: Vermeulen et al. (2021) (Longitudinal) | Bidirectionality between sleep length and externalizing problems might be attributed to environmental and genetic factors rather than the variables themselves. Reciprocal relationship between sleep problems and behavioral difficulties were observed, whereas sleep duration was not seen to be a contributing factor to maladaptive behavioral activity. |

Large sample size. Use of longitudinal discordant MZ cotwin design. |

Questionnaires with few items were used. No objective sleep measures. |

| S17: Wang et al. (2021) (Longitudinal) | A bidirectional relationship was detected between ADHD symptoms and sleep problems, with sleep being a stronger predictor of ADHD symptoms than vice versa. Sleep problems were found to be unidirectionally predicting conduct problems; the reverse relationship was non-significant. |

Assessing the sleep-externalizing behavior relationship in a unique context (post-earthquake). Examining the relationship of sleep with different facets of externalizing behavior (ADHD symptoms and conduct problems). |

No objective sleep measures. Data non-generalizable to the general population. Short period between collecting data from two waves. |

| S18: Kelly et al. (2022) (Longitudinal) | Bidirectionality between sleepiness and externalizing behavior was observed. Sleep duration was discovered to predict and be predicted by externalizing behavior. |

Assessment of specific sleep variables (sleepiness, sleep duration). Implementation of both subjective and objective sleep measures. |

Sleep stages, which may be an important factor in determining sleep-behavior associations, were not examined. Actigraphy was only employed during two weekend nights at each data collection wave. |

| S19: Van Dyk et al. (2016) (Cross-Sectional) | Increased externalizing symptoms were associated with shorter sleep. Every hour more in an individual’s sleep time led to a decline in mean externalizing problems. Unlike in the relationship with objective sleep duration, no significant bidirectionality between subjective sleep quality and externalizing problems was observed. |

Psychological symptoms and sleep were gauged in the environment natural for the participants. Application of various multivariable assessment techniques. Assessing a clinical group of individuals, the study obtained sufficient power to elaborate on effects of the measured variables on a daily level which allowed more detailed insights into the dynamics of bidirectionality between sleep and externalizing behavior. |

Small sample size. Bigger generalizations are not warranted. Possible changes in everyday youth’s functioning that could have influenced their sleep and mental health were not controlled for. No comparison group. |

| S20: Yaugher & Alexander (2015) (Cross-Sectional) | Bidirectionalities between impulsivity and sleep as well as between antisocial traits and sleep were found to be insignificant. Impulsivity was a predictor of subjectively reported poor sleep quality; however, it was not a predictor of objectively measured sleep duration and efficiency by actigraphy. Psychopathic (antisocial) traits TriPM scores were found not to be a significant predictor of subjective sleep quality. Similarly, they were not predictive of sleep duration. |

Implementation of both subjective and objective measures to assess sleep. Assessment of the relationship between sleep and distinct types of psychological outcomes. |

Overrepresentation of the Caucasian subjects (64.5%). Non-clinical population was assessed; described relationships between measured variables might be different for individuals with psychiatric diagnoses. |

Table 3.

Studies which met each of the quality assessment criteria.

| Question | Number of studies which met a given criterion |

Studies |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Sample procedure of cohort described? | 18 | S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S6, S7, S8, S9, S10, S11, S12, S13, S14, S15, S16, S17, S18 |

| 2. Population characteristics described? | 20 | S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S6, S7, S8, S9, S10, S11, S12, S13, S14, S15, S16, S17, S18, S19, S20 |

| 3. Inclusion and exclusion criteria described? | 18 | S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S6, S7, S8, S9, S10, S11, S12, S14, S15, S17, S18, S19, S20 |

| 4. Studied population ≥ 75% of the originally selected population? | 13 | S1, S2, S3, S4, S6, S7, S9, S10, S12, S14, S15, S17, S20 |

| 5. Information about responders vs non responders? | 12 | S1, S2, S3, S5, S6, S7, S8, S9, S11, S14, S15, S17 |

| 6. Lost to follow-up < 20%? | 5 | S1, S3, S9, S16, S18 |

| 7. Information about completers vs non-completers? | 20 | S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S6, S7, S8, S9, S10, S11, S12, S13, S14, S15, S16, S17, S18, S19, S20 |

| 8. Are sleep disturbances assessed for clinical diagnosis? | 2 | S2, S14 |

| 9. Are externalizing behaviors assessed for clinical diagnosis? | 2 | S2, S14 |

| 10. Same measures for baseline and follow-up? | 18 | S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S6, S7, S8, S9, S10, S11, S12, S13, S14, S15, S16, S17, S18, |

| 11. Does the sleep variable assess a specific sleep-related problem? | 10 | S2, S4, S9, S10, S11, S15, S16, S18, S19, S20 |

| 12. Correction for potential demographic confounders? | 13 | S1, S3, S4, S5, S7, S8, S9, S11, S14, S17, S18, S19, S20 |

| 13. Correction for circadian rhythm disorders, alcohol & drug use, exercise, or caffeine intake? | 2 | S2, S11 |

| 14. Correction for other potential non-demographic confounders, such as physical disorders or medication? | 8 | S1, S3, S4, S5, S9, S14, S19, S20 |

| 15. Are given data usable/transformable for meta-analysis? | 20 | S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S6, S7, S8, S9, S10, S11, S12, S13, S14, S15, S16, S17, S18, S19, S20 |

Table 4.

Other methodological approaches: reported directionality, informants for the behavior measure, and sleep measure type (objective/subjective), ordered by the reported directionality.

| Reported Directionality (arrows illustrate the direction of a given relationship24) |

Authors | Informant for the behavior measure |

Sleep measure |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parents | Self-report | Teachers | Subjective | Objective | |||

| BIDIRECTIONALITY | ODD25 ← → insomnia ADHD symptoms → insomnia insomnia → conduct disorder |

Steinsbekk & Wichstrøm (2015) | + | + | |||

| self- & attention regulation ← → sleep problems | Williams et al. (2017) | + | + | ||||

| externalizing behavior ← → sleep problems | Kouros & El-Sheikh (2015) | + | + | ||||

| externalizing behavior ← → sleep problems | Liu et al. (2021) | + | + | + | + | ||

| externalizing behavior ← → sleep problems | Quach et al. (2018) | + | + | ||||

| externalizing behavior ← → behavioral sleep problems | Williamson et al. (2021) | + | + | ||||

| externalizing behavior ← → sleep problems externalizing behavior ← → sleep/wake problems adjustment problems ← → sleep problems |

Kelly & El-Sheikh (2014) | + | + | + | + | ||

| impulsivity ← → sleep quality/sleep quantity impulsivity ← → insomnia |

Bauducco et al. (2019) | + | + | ||||

| externalizing behaviors ← → sleep problems | Wang et al. (2016) | + | + | + | |||

| attention problems ← → sleep problems sleep problems → aggression |

Gregory & O’Connor (2002) | + | + | ||||

| ODD ← → sleep problems | Shanahan et al. (2014) | + | + | ||||

| externalizing behavior ← → sleep duration externalizing behavior ← → sleep problems |

Kortesoja et al. (2020) | + | + | ||||

| externalizing behavior ← → sleep problems | Vermeulen et al. (2021) | + | + | ||||

| externalizing behavior ← → sleep duration | Van Dyk et al. (2016) | + | + | + | + | ||

| ADHD symptoms ← → sleep problems sleep problems → conduct problems |

Wang et al. (2021) | + | + | ||||

| externalizing behavior ← → sleepiness externalizing behavior ← → sleep duration |

Kelly et al. (2022) | + | + | + | |||

| UNIDIRECTIONALITY | externalizing behavior → increased bedtime resistance | Conway et al. (2017) | + | + | |||

| sleep disturbances → externalizing behavior | Pieters et al. (2015) | + | + | ||||

| impulsivity → poor sleep quality | Yaugher & Alexander (2015) | + | + | + | |||

| No relationship | Bidirectionality between sleep and behavior was found to be insignificant; the relationship between emotional problems and sleep was the only bidirectionality reported to be significant. | Mulraney et al. (2016) | + | + | |||

| TOTAL (n) | 14 | 10 | 1 | 19 | 5 | ||

A one-sided (→) arrow shows that a factor mentioned on the left impacts the one on the right, whereas a two-sided arrow (← →) indicate a bidirectional relationship between two factors..

Oppositional-Defiant Disorder.

2.2.6. Quality assessment

An assessment of study quality of each selected article was performed with minor adjustments to an instrument that was implemented in a systematic review performed by Alvaro and colleagues, who concentrated on the bidirectionality of sleep disturbances, anxiety, and depression; 1 the tool was adapted from other meta-analyses. 47, 48 The 15-item checklist was modified to focus on externalizing behavior; item 8 was divided into two items and item 10 was removed. Studies that fulfilled a given criterion were marked with a “1′, whereas those that did not were marked with a “0′. As Table S2 shows, depending on study type, an article could be awarded a maximum of either 12 (for cross-sectional design) or 15 (for longitudinal design) points. In item 11 (“Does the sleep variable assess a specific sleep-related problem?”), a point was given whenever at least one sleep measure assessed a specific sleep-related problem, even if other instruments measuring general sleep problems were also implemented. In order to make the quality assessment results comparable to one another, percentage values were reported for total scores. Following past systematic reviews, a 60% score was used as a benchmark for “high quality” studies. 48, 49 Each item from the quality assessment tool was independently evaluated by the first and the second authors to ensure internal validity and minimize the risk of bias, and all disputes were resolved upon additional review of the studies.

3. Results

3.1. Overall characteristics of studies

Tables 1 and 2 provide information about study type, objectives, study design and setting, sample characteristics, sleep measures, behavior measures, covariates, major findings, strengths, and limitations. Table 3 shows the quality assessment ratings and Table 4 shows data on the directionality of the observed relationships, informants for the externalizing behavior measure, and sleep variables (objective/subjective).

Eight studies were conducted in the United States, five in Australia, two in the Netherlands, two in China, and one in Finland, Sweden, and Norway. Sample sizes ranged from 25 subjects to 12,283 subjects. Participants’ age extended from toddlerhood to 27 years, with the majority of studies (n = 16) focusing on school-aged subjects. Most studies (n = 13) recruited participants from the general population. Four studies involved subjects from either clinical or subclinical populations, one study recruited twins, one enrolled adolescents who experienced an earthquake, and one included children from adoptive families. More than one study used data from the following cohorts: the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children 9, 54, 55 and the Child Regulation Study. 51, 56 However, given the fact that these publications focused on different aspects of a given cohort (i.e., Williams et al., 2017 and Quach et al., 2018), 1, 54 considered additional measures/variables (e.g., health-related quality of life in the case of Williamson et al., 2021), 55 or analyzed different waves of measurements for a given cohort (i.e., Kelly & El-Sheikh, 2014 and Kouros & El-Sheikh, 20 15),51, 56 they were classified as distinct studies in this systematic review. Two studies were cross-sectional and the remainder (n = 18) were longitudinal.

For longitudinal studies, the average duration between baseline and final follow-up measurements was 4.94 years (median: 4 years, standard deviation: 3.86 years). Regarding measurement of sleep, most studies (n = 19) employed subjective measures, while five studies employed objective measures, and four of these studies used both subjective and objective instruments. With regard to measurement of behavior, fourteen studies used parents as informants, ten applied self-reports, and one study included teachers’ reports. Some authors utilized more than one measure: four studies used both parental reports and self-reports while one study gathered information from parents, children, and teachers.

In terms of quality assessment, ratings ranged from 33.3% to 80%, with an average of 61.6%. Eight of the studies qualified as of high quality. Data from all twenty publications were transformable for use in a meta-analysis. Eighteen studies described inclusion and exclusion criteria, thirteen studies studied ≥ 75% of the originally selected populations, twelve studies outlined information about responders and non-responders, and thirteen corrected for potential demographic confounders. Eight studies corrected for potential non-demographic confounders, and two studies corrected for circadian rhythm disorders, alcohol and drug use, exercise, or caffeine intake. Half of the studies employed a sleep variable that assessed a specific sleep-related problem and five studies lost to follow-up < 20% of the originally recruited sample < 20%. Two studies assessed sleep disturbances using clinical diagnosis, while 2 studies assessed externalizing behavior using clinical diagnosis.

3.2. Sleep variables

Ten studies applied sleep measures assessing general non-specific sleep problems. These instruments, similar to those assessing behavior, consisted of items investigating specific sleep problems whose compilation provided a total overall sleep problem score (e.g., Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ) including ratings of sleep duration, bedtime resistance, daytime sleepiness etc.). Among general sleep measures, the Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment (ASEBA) framework is the most popular (60%); the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) (n = 4) was the most prevalent, followed by the Youth Self-Report (n = 2), and the CSHQ (n = 2). In publications implementing sleep measures assessing specific sleep difficulties, problems that were assessed included sleep duration (n = 4), sleep quality (n = 4), sleep/wake problems (n = 3), sleepiness (n = 1), insomnia (n = 1), and specific sleep disorder, including insomnia, sleepwalking, hypersomnia, and nightmare disorder (n = 1). Some studies included both general and specific sleep problems measures, while others employed multiple specific sleep measures.

3.3. Externalizing behavior variables

General externalizing problems rather than specific types of externalizing behavior (such as impulsivity) were most often assessed (n = 14). The CBCL and Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) were the two most popular general measures of externalizing behavior, used by, respectively, five and six studies. Other studies (n = 6) either implemented measures which concentrated exclusively on a specific facet of externalizing behavior (e.g., impulsivity, psychopathy, attention deficits) or involved a psychiatric assessment aimed at providing perspectives on specific mental disorders, such as oppositional-defiant disorder. Methods for measuring general externalizing problems did account for specific externalizing difficulties (for instance, through the use of subscales gaging hyperactivity/inattention and conduct problems in the SDQ). Additionally, authors who used general instruments could emphasize a certain aspect of the instrument; for example, Gregory & O’Connor used the CBCL while providing details on relationships between aggression and sleep as well as attention problems and sleep.60

3.4. Summary of directionality of the reciprocal relationships

3.4.1. Bidirectional relationships

As Table 4 shows, out of twenty studies, 80% (n = 16) reported a significant bidirectional relationship between sleep and externalizing behavior. Of these, ten focused on general sleep problems, whereas six focused on specific sleep problems: sleep duration, sleep quality, insomnia, sleepiness, and sleep/wake problems. Among articles which revealed bidirectionality between sleep and externalizing behavior, seven studies concentrated on specific behavioral difficulties: conduct problems, hyperactivity, impulsive behavior, self-regulation, ODD, ADHD symptoms, and attention issues. Some studies employed a combined approach: among ten assessing general sleep problems, five also assessed a specific behavior variable. At the same time, out of nine publications in which nonspecific externalizing behavior was measured, less than half (n = 4) also focused on specific sleep problems.

The majority of studies that reported significant bidirectional relationships employed subjective sleep measures (n = 12). Of these, six referred to parents as exclusive informants for the externalizing behavior variable, four utilized self-reports only, one relied on both parental reports and self-reports, and one had three informants (participants, their parents, and their teachers). Out of these sixteen publications which reported significant bidirectional relationships, four studies either employed an objective sleep measure alone or employed both an objective and a subjective sleep measure.

In terms of the quality of the studies that reported significant bidirectional relationships, five studies were of high quality, four were at the cutoff point of 60%, and the remaining seven were of low quality. Among studies that discovered reciprocal relationships, the average score equaled 60.3%, exceeding the benchmark for high quality studies in our assessment.

3.4.2. Unidirectionality and non-significant studies

Six studies (30%) reported unidirectional relationships between sleep and externalizing behaviors. The directionality of these associations varied. Three studies reported that externalizing behavior unidirectionally predicted later sleep problems: impulsivity → subjectively reported poor sleep quality,67 attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) → increased risk of insomnia,2 externalizing behavior → increased bedtime resistance.50 At the same time, the following one-way links with sleep affecting externalizing behavior were observed: sleep disturbances → externalizing problems,58 insomnia → conduct disorder,2 and early life sleep difficulties → aggression,60 and sleep problems → conduct problems.64 One study2 reported both types of sleep-externalizing behavior directionalities, although they pertained not to the same variables but instead distinct facets of behavioral problems. Significant bidirectional relationships were not seen for subjective sleep quality and externalizing problems, impulsivity and sleep, antisocial traits and sleep, externalizing behavior and sleep in children with ADHD, externalizing behavior and trouble getting to sleep, conduct disorder and sleep problems, and ADHD and sleep problems.

3.4.3. Controlling for covariates

Because many covariates and confounders can be attributed to both sleep and behavior, the rigor of these studies can be partially dependent on which types of covariates have been adjusted. Our analysis shows that studies vary in their control for covariates. As shown in Table 1, all twenty studies accounted for age and gender. The second most popular covariates were ethnicity, which was reported in eleven publications, and socioeconomic status or its proxies (such as parental education and parental income), which eleven studies controlled for. Other confounds included both a physiological indicator (puberty, BMI) and social/family environment (number of siblings, attended school, language spoken at home). Furthermore, some studies involved clinical populations, with covariates including sleep medication, psychotropic medication, ADHD subtype, ADHD medication, adoptive status, mental disorders comorbidities, and autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

3.4.4. Controlling for baseline sleep or behavior

Controlling for baseline for either sleep or behavior could be important in order to examine whether such manifestations are the result of outcomes from underlying sleep or behavior problems or the result of truly causal relationships. However, among the studies we selected, only six explicitly controlled for baseline sleep and/or behavior problems.9, 53, 60, 61, 64, 65 All of these studies had large sample sizes ranging from 215 to 4109. In these studies, the average number of years between baseline and final follow-up measurements was bigger than the median (4 years) of all included studies. Studies which controlled for baseline sleep or behavior problems reported significant bidirectional relationships between sleep and general externalizing behavior,53 sleep and attention problems,9, 60 sleep and ODD,61 sleep and ADHD symptoms,64 sleepiness and externalizing behavior,65 and sleep duration and externalizing behavior.65 Nevertheless, it is possible that other studies controlled for baseline sleep or behavior as well (e.g., through implementing cross-lagged methods), but this control was not mentioned explicitly in their methodology sections.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review investigating the bidirectionality of sleep and externalizing behavior. Of the 20 studies included, 18 employed longitudinal study designs. Sixteen publications reported significant bidirectional associations between sleep and externalizing behavior. Thus, our systematic review demonstrated the existence of a two-way relationship between sleep and externalizing behavior. Gaining more insights into reciprocal links between sleep and externalizing behavior is of potential importance to clinical practice in that both sleep and behavioral symptoms, rather than one and not the other, may be targeted in therapy to effectively tackle a self-perpetuating deleterious sleep-mental health cycle. We posit that this finding might be particularly beneficial for subclinical populations struggling with sleep and/or behavioral problems. Breaking their cycle with such a two-pronged therapeutic approach at early stages of the impairment can prevent more severe clinical health problems from emerging.

While behavior was exclusively gauged subjectively due to its nature, sleep was measured either objectively or subjectively. Hence, we stratified the sections below by this variable. To investigate why certain studies reported the bidirectionality of interest while others did not, we reviewed their methodological approaches and outcomes.

Because the majority of studies involved relatively large sample sizes, subjective sleep measures were the most popular instruments for gaging sleep due to their relative ease of implementation and reduced cost compared to objective sleep measures. This is particularly true for the study of bidirectionality which involves a follow-up period. Only five (25%) of the selected studies employed objective sleep measures. While utilizing subjective sleep measures have their advantages (enabling the assessment of facets of sleep that are not objective by nature, e.g., troubles with falling asleep, daytime sleepiness), their common use could affect the observed results as they are intrinsically prone to error.

Generally speaking, objective sleep measures are considered to be more valid and reliable in comparison to subjective measures.64, 65 On the other hand, subjective sleep measures are capable of measuring other dimensions of sleep-related phenomena not suited for actigraphy or polysomnography (e.g. daytime sleepiness). Hence, subjective and objective sleep measures may be complementary, providing a comprehensive perspective on the matters associated with sleep. Nevertheless, the publications that we analyzed frequently employed well-validated subjective sleep measures.

Interestingly, studies which assessed general sleep problems predominantly included measures drawn from the Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment framework, which is widely used to assess behavior problems but also contains sleep items.68 Given the fact that the CBCL, which is one of the ASEBA instruments, was the most prevalent among general sleep measures in the selected studies, it is important to point out that this instrument is considered adequate for assessing sleep in epidemiological studies but not for research into specific sleep problems and disorders (unless individual CBCL items instead of the entire checklist are used).69 However, an issue arising here, method variance, could have contributed to the significant results observed. When both sleep and behavior are measured using the same instrument, a halo effect may occur which increases all the correlations between scales. Since four studies50, 53, 59, 60 utilized the CBCL for assessing both behavior and sleep, and since all reported significant bidirectional relationships, method variance is crucial to consider when interpreting the outcomes of these studies. We observed that there was no clear relationship between instrument quality and findings in the studies reviewed here, as different levels of quality suggested by Lewandowski and others in compliance with EBA criteria did not translate into differential findings.70

Of the three studies that implemented subjective measures and did not report significant bidirectional relationships, two recruited participants from non-typical populations. Mulraney and colleagues recruited children with ADHD,52 while Conway and others recruited a toddler population with sleep and behavior problems.50 It may be the case that high levels of behavioral and sleep problems at baseline, which remained high at follow-up, influenced the lack of a significant longitudinal relationship. As Mulraney and colleagues hypothesize, researching a sample with relatively modest impairments at baseline could have yielded different results.52 On the other hand, developmental considerations should be taken into account. As Conway and colleagues state, “bedtime resistance at this period may be a developmentally normative behavior, which does not lead to increases in externalizing behavior. For boys who have high levels of early externalizing behavior, however, bedtime resistance increases”.50 The last study which employed subjective sleep measures and which did not report significant bidirectional relationships between sleep and externalizing behavior was Pieters and colleagues, where developmental aspects of adolescence and other third-party factors were suggested to possibly affect the results of this research.58 Therefore, we would suggest that different outcomes of these studies could be associated with specific elements of their design (participants, developmental influences, confounds unaccounted for). We believe the ambiguity concerning the bidirectionality of sleep and externalizing behavior is related to implementation of subjective sleep measures since, as stated previously, their accuracy is moderate when compared to objective sleep measures.

Only one study utilized objective sleep measures alone. In a large sample (n = 142), Kouros and El-Sheikh51 were able to assess sleep variables without the risk of self-report bias or parents’ not being fully aware of their children’s sleeping habits impacting the observed outcomes. Due to the application of various sleep parameters, an objective comprehensive sleep assessment was possible, with the authors arguing that, in comparison to sleep duration, sleep quality may be more significant in the context of negative behavioral effects.51 Given the methodological rigor of this study, we believe it presents the strongest evidence on the relationship between sleep and externalizing problems.

Four studies applied both subjective and objective measures to assess sleep variables. We believe that results from these studies could be particularly useful in determining specificity of the bidirectionality of sleep and externalizing behavior. Van Dyk and colleagues reported that increased externalizing behavior was associated with shorter sleep and vice versa. However, no significant bidirectionality between subjective sleep quality and externalizing problems was observed.66 Yaugher and Alexander discovered that impulsivity was a predictor of subjectively reported poor sleep quality, but it was not a predictor of objectively measured sleep duration and efficiency, as measured by actigraphy. Moreover, they did not find any bidirectional relationships between sleep and externalizing behavior, with impulsivity unidirectionally predicting later sleep problems.67 A third study which also assessed both objective and subjective sleep measures reported bidirectionality between sleep and externalizing behavior.56 At the same time, Kelly and colleagues (2022) reported bidirectionalities between sleepiness and externalizing behavior as well as sleep duration and externalizing behavior.65 This heterogeneity of outcomes in relatively similar studies dictates that more sophisticated and methodologically stronger research is needed to firmly establish causality in this relationship.

4.1. Implications and future directions

Given the variability in methods and outcomes reported in the selected studies, future research should aim to establish more unequivocal support for the bidirectionality between sleep and externalizing behavior. Importantly, specific aspects of both sleep (e.g., insomnia, hypersomnia, sleep/wake problems) and externalizing behavior (e.g., aggression, delinquency, impulsivity) should be closely examined, and determining relationships between specific facets of the two variables would be especially informative for future early interventions that could break the cycle of mutually exacerbating sleep and behavioral disturbances.9 At the same time, there are other important sleep parameters that have not received enough attention in the selected studies, including intraindividual variability in sleep duration and quality. Investigating this phenomenon could lead to a better understanding of transactional dynamics between sleep and externalizing behavior.71, 72

Additionally, interventions and objective sleep measures can be employed in future study design to gain more conclusive evidence about the relationships being reported. Another important factor to underscore in future studies is to control for baseline behavior and sleep problems, for which only a few studies explicitly controlled. By controlling for baseline sleep and behavior, precise bidirectional relationships could be determined.

4.2. Limitations of the current systematic review

Several limitations should be considered. First, we did not conduct a meta-analysis. Taking into consideration how diverse the included studies were in terms of recruited participants, assessments employed, and operationalization of the variables of interest, and considering that studies with seemingly similar study designs yielded quite different outcomes, this heterogeneity precluded the conduction of a meta-analysis at this point in time. Without it, definite conclusions about the bidirectional relationship between our variables of interest cannot be made. When future empirical studies gather more homogenous data on the bidirectionality between sleep and externalizing behavior, meta-analysis should be performed to quantify this association using inferential statistics. Another possible limitation of this review stems from our search approach. Publications written in English which directly focused on reciprocity between sleep and externalizing behavior were considered. Taking into account sources that either assessed bidirectionality indirectly or were written in other languages could expand the scope of our systematic review, possibly allowing for a quantitative analysis of the role of gender or age in the observed reciprocal relationships. Moreover, publication bias should be considered. To present a wide spectrum of results reported by the studies, we accounted for insignificant bidirectional relationships and unidirectional associations among these publications. Of course, they can still be impacted by selective reporting, which would distort our reviewing endeavors. Lastly, more definite conclusions could have been drawn if more studies were of high quality, which was the case for 40% of studies in this systematic review.

5. Conclusions

Overall, the literature on the subject of bidirectional relationship of sleep and externalizing behavior suggests that reciprocal associations between these two variables likely exist, though the strength of these associations is unclear due to heterogeneous methodological approaches of the studies reviewed. More studies applying objective sleep measures and focusing on specific sleep disturbances and externalizing symptoms are needed. We believe that such an approach will inform clinical practice, helping to prevent mutual exacerbation of worsening sleep and behavioral symptoms at early stages of the impairment.

Supplementary Material

Table S1. Detailed search strategy.

Table S2. Quality assessment of the included studies.

Table S3. PRISMA 2020 Checklist.

Table S4. PRISMA 2020 for Abstracts Checklist.

Funding

This work was supported by The National Institute of Child Health and Development (NIH/NICHD R01-HD087485).

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

Authors declare no competing interest or financial disclosures.

Supplementary materials

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi: 10.1016/j.sleepe.2022.100039.

References

- [1].Alvaro PK, Roberts RM, Harris JK. A systematic review assessing bidirectionality between sleep disturbances, anxiety, and depression. Sleep 2013;36(7):1059–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Steinsbekk S, Wichstrøm L. Stability of sleep disorders from preschool to first grade and their bidirectional relationship with psychiatric symptoms. J Dev Behav Pediatrics 2015;36(4):243–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Sheppes GSG, Gross JJ. Emotion regulation and psychopathology. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2015(11):379–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Asarnow LD, Mirchandaney R. Sleep and mood disorders among youth. Child Adolesc Psychiatric Clinics 2021;30(1):251–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Gilbert KE. The neglected role of positive emotion in adolescent psychopathology. Clin Psychol Rev 2012;32(6):467–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Shochat T, Cohen-Zion M, Tzischinsky O. Functional consequences of inadequate sleep in adolescents: a systematic review. Sleep Med Rev 2014;18(1):75–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Tempesta D, Socci V, De Gennaro L, Ferrara M. Sleep and emotional processing. Sleep Med Rev 2018;40:183–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Newton AT, Honaker SM, Reid GJ. Risk and protective factors and processes for behavioral sleep problems among preschool and early school-aged children: a systematic review. Sleep Med Rev 2020;52:101303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Williams KE, Berthelsen D, Walker S, Nicholson JM. A developmental cascade model of behavioral sleep problems and emotional and attentional self-regulation across early childhood. Behav Sleep Med 2017;15(1):1–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group* P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 2009;151(4):264–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int J Surg 2021;88:105906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Achenbach TM. The child behavior profile: I. Boys aged 6–11. J Consult Clin Psychol 1978;46(3):478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Liu J. Childhood externalizing behavior: theory and implications. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs 2004;17(3):93–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Bélanger M-È, Bernier A, Simard V, Desrosiers K, Carrier J. Sleeping toward behavioral regulation: relations between sleep and externalizing symptoms in toddlers and preschoolers. J Clinical Child Adolesc Psychol 2018;47(3):366–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Dzierzewski JM, Ravyts SG, Dautovich ND, Perez E, Schreiber D, Rybarczyk BD. Mental health and sleep disparities in an urban college sample: a longitudinal examination of White and Black students. J Clin Psychol 2020;76(10):1972–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Johnson EO, Roth T, Breslau N. The association of insomnia with anxiety disorders and depression: exploration of the direction of risk. J Psychiatr Res 2006;40(8):700–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Kaneita Y, Yokoyama E, Harano S, et al. Associations between sleep disturbance and mental health status: a longitudinal study of Japanese junior high school students. Sleep Med 2009;10(7):780–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Könen T, Dirk J, Leonhardt A, Schmiedek F. The interplay between sleep behavior and affect in elementary school children’s daily life. J Exp Child Psychol 2016;150:1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Liu X, Liu Z-Z, Liu B-P, Sun S-H, Jia C-X. Associations between sleep problems and ADHD symptoms among adolescents: findings from the Shandong Adolescent Behavior and Health Cohort (SABHC). Sleep 2020;43(6):zsz294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Meijer AM, Reitz E, Deković M, Van Den Wittenboer GL, Stoel RD. Longitudinal relations between sleep quality, time in bed and adolescent problem behaviour. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Muratori P, Menicucci D, Lai E, et al. Linking sleep to externalizing behavioral difficulties: a longitudinal psychometric survey in a cohort of Italian school-age children. J Prim Prev 2019;40(2):231–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Nota JA, Chu C, Beard C, Björgvinsson T. Temporal relations among sleep, depression symptoms, and anxiety symptoms during intensive cognitive–behavioral treatment. J Consult Clin Psychol 2020;88(11):971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Salis KL, Bernard K, Black SR, Dougherty LR, Klein D. Examining the concurrent and longitudinal relationship between diurnal cortisol rhythms and conduct problems during childhood. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2016;71:147–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Schneiderman JU, Ji J, Susman EJ, Negriff S. Longitudinal relationship between mental health symptoms and sleep disturbances and duration in maltreated and comparison adolescents. J Adolesc Health 2018;63(1):74–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Tsai M-H, Huang Y-S. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and sleep disorders in children. Med Clinics 2010;94(3):615–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Wong PM, Hasler BP, Kamarck TW, et al. Day-to-day associations between sleep characteristics and affect in community dwelling adults. J Sleep Res 2021;30(5):e13297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Dimakos J, Gauthier-Gagné G, Lin L, Scholes S, Gruber R. The Associations Between Sleep and Externalizing and Internalizing Problems in Children and Adolescents with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: empirical Findings, Clinical Implications, and Future Research Directions. Child Adolesc Psychiatric Clinics 2021;30(1):175–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Havekes R, Heckman PR, Wams EJ, Stasiukonyte N, Meerlo P, Eisel UL. Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis: the role of disturbed sleep in attenuated brain plasticity and neurodegenerative processes. Cell. Signal 2019;64:109420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Hiscock H, Sciberras E, Mensah F, et al. Impact of a behavioural sleep intervention on symptoms and sleep in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and parental mental health: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2015:350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Kamphuis J, Meerlo P, Koolhaas JM, Lancel M. Poor sleep as a potential causal factor in aggression and violence. Sleep Med 2012;13(4):327–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Maski KP, Kothare SV. Sleep deprivation and neurobehavioral functioning in children. Int J Psychophysiol 2013;89(2):259–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].O’Brien LM. The neurocognitive effects of sleep disruption in children and adolescents. Sleep Med Clin 2011;6(1):109–16. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Pisano S, Muratori P, Gorga C, et al. Conduct disorders and psychopathy in children and adolescents: aetiology, clinical presentation and treatment strategies of callous-unemotional traits. Ital J Pediatr 2017;43(1):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Barrett JR, Tracy DK, Giaroli G. To sleep or not to sleep: a systematic review of the literature of pharmacological treatments of insomnia in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2013;23(10):640–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Bondopadhyay U, Diaz-Orueta U, Coogan AN. A systematic review of sleep and circadian rhythms in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Atten Disord 2022;26(2):149–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Gregory AM, Sadeh A. Sleep, emotional and behavioral difficulties in children and adolescents. Sleep Med Rev 2012;16(2):129–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Raine A. Antisocial personality as a neurodevelopmental disorder. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2018;14:259–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Short MA, Weber N. Sleep duration and risk-taking in adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev 2018;41:185–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Gordon AM, Del Rosario K, Flores AJ, Mendes WB, Prather AA. Bidirectional links between social rejection and sleep. Psychosom Med 2019;81(8):739–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Huang BH, Hamer M, Duncan MJ, Cistulli PA, Stamatakis E. The bidirectional association between sleep and physical activity: a 6.9 years longitudinal analysis of 38,601 UK Biobank participants. Prev Med Feb 2021:143106315. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Kang Y, Liu S, Yang L, et al. Testing the bidirectional associations of mobile phone addiction behaviors with mental distress, sleep disturbances, and sleep patterns: a one-year prospective study among Chinese college students. Front Psychiatry 2020:634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Kim Y, Umeda M, Lochbaum M, Sloan RA. Examining the day-to-day bidirectional associations between physical activity, sedentary behavior, screen time, and sleep health during school days in adolescents. PLoS One 2020;15(9):e0238721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Agostini A, Centofanti S. Normal sleep in children and adolescence. Child Adolesc Psychiatric Clinics 2021;30(1):1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Dahl RE, Lewin DS. Pathways to adolescent health sleep regulation and behavior. J Adolesc Health 2002;31(6):175–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Matthys W, Vanderschuren LJ, Schutter DJ. The neurobiology of oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder: altered functioning in three mental domains. Dev Psychopathol 2013;25(1):193–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Zheng M, Rangan A, Olsen NJ, Heitmann BL. Longitudinal association of nighttime sleep duration with emotional and behavioral problems in early childhood: results from the Danish Healthy Start Study. Sleep 2021;44(1):zsaa138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Kuijpers T, van der Windt DA, van der Heijden GJ, Bouter LM. Systematic review of prognostic cohort studies on shoulder disorders. Pain 2004;109(3):420–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Luppino FS, de Wit LM, Bouvy PF, et al. Overweight, obesity, and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2010;67(3):220–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Van der Kooy K, Van Hout H, Marwijk H, Marten H, Stehouwer C, Beekman A. Depression and the risk for cardiovascular diseases: systematic review and meta analysis. Int J Geriatric Psychiatry: J Psychiatry Late Life Allied Sci 2007;22(7):613–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Conway A, Miller AL, Modrek A. Testing reciprocal links between trouble getting to sleep and internalizing behavior problems, and bedtime resistance and externalizing behavior problems in toddlers. Child Psychiatry Human Dev 2017;48(4):678–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Kouros CD, El-Sheikh M. Daily mood and sleep: reciprocal relations and links with adjustment problems. J Sleep Res 2015;24(1):24–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Mulraney M, Giallo R, Lycett K, Mensah F, Sciberras E. The bidirectional relationship between sleep problems and internalizing and externalizing problems in children with ADHD: a prospective cohort study. Sleep Med 2016;17:45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Liu J, Glenn AL, Cui N, Raine A. Longitudinal bidirectional association between sleep and behavior problems at age 6 and 11 years. Sleep Med 2021;83:290–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Quach JL, Nguyen CD, Williams KE, Sciberras E. Bidirectional associations between child sleep problems and internalizing and externalizing difficulties from preschool to early adolescence. JAMA Pediatr 2018;172(2):e174363 –e174363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Williamson AA, Zendarski N, Lange K, et al. Sleep problems, internalizing and externalizing symptoms, and domains of health-related quality of life: bidirectional associations from early childhood to early adolescence. Sleep 2021;44(1):zsaa139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Kelly RJ, El-Sheikh M. Reciprocal relations between children’s sleep and their adjustment over time. Dev Psychol 2014;50(4):1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Bauducco SV, Salihovic S, Boersma K. Bidirectional associations between adolescents’ sleep problems and impulsive behavior over time. Sleep Med: X 2019;1:100009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]