Abstract

In the field of family science and in the broader family policy discourse, debate is ongoing about the importance of family structure for child outcomes. Missing from this debate is a full integration of how the foundational pillars of White supremacy, namely structural racism and heteropatriarchy, impact both family formation and child outcomes, especially among diversely configured Black families. From a critical intersectional lens, we argue that conceptual models used to explain racialized child outcomes based on family structure effects are problematic because they compare family structure statuses without accounting for structural racism and interlinked heteropatriarchal conditions. We present a new conceptual model that integrates structural racism and heteropatriarchy to examine the salience of family structure statuses for child outcomes and discuss approaches to research design, empirical measurement, and interpretation in order to bring this new model into practice.

Keywords: African American Families, Child well-being, Family Structure, Race/ethnicity, Structural Racism

In the field of family science and in the broader family policy discourse, debate is ongoing about the importance of family structure—or more specifically, a heterosexual, two-parent, stably married, male-breadwinner, female-caregiver nuclear structure—for child outcomes (Jensen & Sanner, 2021). Missing from this debate is the full integration and understanding of how the foundational pillars of White supremacy, namely structural racism and heteropatriarchy, impact both family formation and child outcomes, especially among diversely configured Black families (Letiecq, 2019; Smith, 2016; Walsdorf et al., 2020). In this paper, we examine these interlinking forms of oppression and how they influence the structuring (and opportunity structure) of Black families and Black children’s well-being in a racialized and unequal society.

We draw upon an intersectional framework developed by critical race and feminist scholars (e.g., Collins, 1990, 1998; Crenshaw, 1989; Few-Demo, 2014). Intersectionality is increasingly being used by family scholars seeking to understand how social identities interlink with multiple axes of power and oppression to create and sustain racialized structural inequalities in family life (e.g., Burton et al., 2010; Collins, 1998; Few-Demo, 2014). From this lens, we contend that the United States (U.S.) has been built upon a foundation of White supremacy, in which an often-covert system of domination developed of, by, and for White men serves to maintain their power and control over all others (Waldsorf et al., 2020). Central pillars undergirding White supremacy are structural racism and heteropatriarchy, where racism, heterosexism, and patriarchy (i.e., domination by men) have been instantiated and codified into reinforcing laws, policies, rules, practices, ideologies, and customs enacted daily in U.S. society (Bailey et al., 2021; Bonilla-Silva, 1997; Powell, 2008; Smith, 2016). Importantly, these concepts (structural racism, heteropatriarchy) are recognized as structural because they operate at a macrosystems-level. For instance, a person or group of people can hold a set of beliefs about the intrinsic inferiority or superiority of certain racial groups (i.e., ideological or individual-level racism), but racism can also exist in a society in the absence of individual racists, when the structures that uphold that society foster racially discriminatory outcomes (Bonilla-Silva, 1997). Similarly, structural heteropatriarchy sustains a set of political, cultural, and economic systems that favor cisgender men and diminish access to power and resources among women and sexual and gender identity minorities regardless of whether actors within those systems hold sexist or stigmatizing beliefs or attitudes (Everett et al., 2021). In this way, these pillars of White supremacy form an interlocking matrix of domination engineered to maintain the marginalization of Black men, women, and children and other minoritized and marginalized people to the systematic, and often unearned advantaging of those at the top of the racialized heteropatriarchal hierarchy (Letiecq, 2019; Brown, 2021; Collins, 1990, 1998; Walsdorf et al., 2020).

It is from this intersectional lens that we interrogate the effects of family structure on child well-being. We argue that conceptual models used to explain racialized child outcomes based on family structure effects are problematic because they compare family structure statuses without controlling for structural racism and interlinked heteropatriarchal conditions. Here, we posit that family structure, like race, has been socially constructed to reproduce and sustain White heteropatriarchal supremacy to the harms of Black and other families disadvantaged by structural oppression. We present a new conceptual model that integrates structural racism and heteropatriarchy into models examining the salience of family structure statuses for child outcomes. We conclude with recommendations to further shift the research paradigm in family science to account for other structural forms of oppression in our theorizing, research approaches, methodologies, and meaning-making in order to advance a more just and anti-racist society.

Background

A central focus of family science has been to articulate the role of family structure and family complexity in shaping children’s well-being and transition into adulthood (Cavanagh & Fomby 2019; Jensen & Sanner, 2021). This work has been justified as a scholarly imperative because families have been positioned as the primary social institution through which resources are filtered to children in support of their physical, emotional, and social development. In the context of the contemporary United States, where the work and cost of raising children is a mostly privatized enterprise, the capacity of families to meet this effort with sufficient resources is largely shaped by who is available to provide them.

One seemingly objective, race-neutral approach put forward by family scientists to understand whether and how family structure influences children is through comparison. In family science, researchers compare outcomes among children who occupy different family structure statuses, such as living with one parent compared to two parents, or who experience a family structure event like parental death, divorce, or remarriage compared to those who do not. Group differences in outcomes are interpreted as a signal of family structure’s potential influence on children. The researcher’s task under this approach is then to isolate any causal role of family structure from its antecedents and consequences and to determine whether it bears any direct or indirect influence on children’s outcomes (Fomby, 2022).

But this enterprise is not impartial in its comparison. Rather, the vast majority of research on how families influence children is premised on the expectation that parents within heteropatriarchal (heterosexual, male-headed), nuclear (e.g., two-parent, stably married, cohoused) families (hereafter HNF) who have all of their children in common and who live apart from other kin provide the ideal family context for children (Jensen & Sanner, 2021). Under this approach, comparison becomes an exercise in investigating whether and why other family structure statuses are relatively harmful to children’s development. In the United States, Black children’s less frequent experience of the HNF structure compared to White children is often invoked as the primary explanation of disparities in children’s outcomes.

On the surface, this valorization of the traditional HNF structure appears to be warranted; it has been the statistical norm for decades in most U.S. settings, and objectively, contemporary children raised in this context experience better physical and socioemotional health, achieve higher grades in school, complete more schooling, and make a more “ordered” transition to adulthood compared to peers who experience other family structure statuses and sequences. But these patterns do not establish cause and effect or any inherent primacy of this family type as a setting for childrearing. Rather, we argue that these patterns reflect the enduring success of legal, economic, and social institutions in a White supremacist society to essentialize the HNF as a recognizable and efficient context through which to legitimate the transfer of resources and wealth from one generation to the next (Brown, 2021; Letiecq, 2019). In this sense, the HNF represents a bargain White women/mothers make with men/fathers, whether intentionally or not, to benefit from the heteropatriarchal status quo and to validate and reproduce it through their children’s achievements. Parents and families who do not make the same bargain or who have been systematically excluded from the HNF bargaining table via structural racism and heteropatriarchy do not receive the same rewards (Brown, 2021; Letiecq, 2019; Marks, 2000).

Historical Perspective

In colonized America, this gendered and racialized social contract was institutionalized in the context of a heteropatriarchal, White supremacist social order where the married-parent family served a particular purpose: to channel the flow of resources between generations of White male property owners (Smith, 2016). Exclusion, then, was elemental to this social contract: specifically, it excluded enslaved Black people, who were denied dominion over their marriages and children and who enjoyed no rights of property ownership or family inheritance. Importantly, the HNF has not always been the most common and idealized family structure in the U.S. Instead, American households shifted from consisting of mostly extended and multigenerational families to families containing only biological parents and their shared children at the end of World War II, during a period of unprecedented economic prosperity and government investment in building the suburban infrastructure that would eventually—and exclusively—house White HNFs (Dow, 2019; Goldscheider & Bures, 2003; Ruggles, 1994). To maintain the HNF lifestyle, these families were often serviced by Black and Brown people as domestic workers.

In fact, before 1940, extended-family households were more common among White than Black families (Goldscheider & Bures, 2003). The two-parent nuclear family only became a viable arrangement when White men were able to earn a family sustaining wage without the financial contributions of other household members (Coontz, 1992; Dow, 2019). Further, its rise to prominence allowed for the gendered division of labor that modern industrial capitalism and heteropatriarchy demanded (ibid). However, Jim Crow laws in the South and more covert forms of racial discrimination in the North (e.g., redlining, blockbusting, segregation, unfair labor practices, labor-related violence) successfully marginalized and segregated families of color into separate and unequal educational systems and housing and labor markets that denied Black men access to a “family wage,” generated low rates of home ownership, and denied Black people equal access to systems that held the keys to upward mobility (Hanks et al., 2018; Letiecq et al., 2021; Pager & Shepherd, 2008). Consequently, the same economic opportunities and governmental investments that promoted and sustained HNFs for the benefit of White upwardly mobile Americans have never been made available to Black Americans and other minoritized groups (Ruggles, 1997).

These kinds of racist, heteropatriarchal, exclusionary laws, policies, and practices were upheld by Christian religious doctrine and applied ubiquitously to deny non-White racial and ethnic minoritized groups and non-heteropatriarchal conforming families (e.g., LGBTQ families) entrée into the institution of marriage and to deny them access to the legal rights and protections needed to form, adapt, and sustain their families under a White heteropatriarchal regime (Coontz, 1992; Collins, 1998; Letiecq, 2019; Smith, 2016). In other words, these tools of oppression used to control, regulate, and sanction Black people, where also applied variously to other minoritized groups, revealing generalized patterns of racial and heteropatriarchal domination. Native American families, for example, were ravaged and disappeared by U.S. laws, policies and practices, with impacts persisting to date (Barnes & Josefowitz, 2019). Asian American people—through a form of structural racism called Orientalism—were deemed exotic, yet inferior, and faced societal exclusions and government-fomented mistrust (Smith, 2016; Tseng & Lee, 2021). More recently, the characterization of Asian Americans as a monolithic “model minority” has diverted attention from their ongoing exposure to racism, discrimination, and oppression and has excused public services and institutions from identifying and meeting the needs of disadvantaged Asian Americans (Shih et al., 2019). Lesbian and gay couples were not only excluded nationally from the institution of marriage until 2015, but LGBTQ families continue to be denied their full human rights (e.g., to claim their gender identity, to adopt children) in many states (Filisko, 2016; Riggle et al., 2017). These family-busting laws, policies, and practices continue to be wielded in the modern era in various forms as the U.S. government removes minoritized children from parental custody at shockingly disproportionate rates (Roberts, 1996, 2016), disproportionately incarcerates minoritized people in its vast prison industrial complex (Alexander, 2010; Lee & Wildeman, 2021), and separates Black and Brown immigrant parents from their children in record numbers (Chisti & Pierce, 2021; Menjívar et al., 2016).

Thus, structural racism, when interlinked with heteropatriarchy, is foundational to the way Black, other minoritized, and White children have experienced family structure throughout America’s history. At the population level, this structural oppression contributes to Black children’s lower likelihood of living in an HNF household compared to White children; it contributes to the weaker gains of marriage that Black children experience when they reside in that family structure; it contributes to the diversity of other family forms (often more egalitarian in nature) that Black children experience; and it foments structural resistance to recognizing those family forms as legitimate (Collins, 1998; Few, 2007; Powell et al., 2016).

We assert that structural racism and interlinked heteropatriarchal forces are so entrenched and so pervasive in their influence in shaping family structure and child outcomes that we risk losing sight of them. Indeed, few scholars studying family structure have pointed to structural racism as a cause of family structure variance, opting instead to interpret variance as culture-made or born out of individual choice (James et al., 2018; Jensen & Sanner, 2021). And the family field has yet to systematically study the HNF’s structural advantage over other family forms or to fully integrate macro-level forces into theoretical models, analyses, or interpretations of the data (Everett et al., 2021; Letiecq, 2019). We contend that this analytical myopia is reflected in the predominant conceptual model often brought to bear on the question of whether and why family structure matters for children, a model that focuses on variation in the individual- and family-level circumstances of family life but ignores how White and Black families continue to negotiate their unequal positions in the social contract with the web of institutions in which family life is embedded. In this model, the compromised well-being of the average Black child is compared to the advantaged well-being of the average White child. Group differences in family structure are invoked as a distal explanation of this disparity; and attendant differences in family resources and behavior are posited as mediators of this relationship (Brown, 2010; Fomby, 2022; Jansen & Sanner 2021). Under this framework, today’s Black families are held accountable for the consequences of group differences in family structure and family functioning that were built into the American system of racialized stratification by a White supremacist majority four centuries ago. Shifting the lens to implicate the enduring roles of structural racism and heteropatriarchy in this model requires a different approach.

Here we review characteristics of the predominant conceptual model that is invoked to empirically evaluate the causal relationship between various dimensions of family structure statuses and events and child well-being. We then describe limitations to this model for identifying and explaining variation in the apparent effect of family structure on Black compared to White children and young adults. We argue that these limitations arise because conceptual and empirical models that seek to identify the causal role of family structure in shaping child outcomes do not take into account structural inequalities in how diverse families interact with the social, legal, and economic institutions that shape and organize how families access and distribute resources to children. As a result, average family structure effects are likely biased; specifically, they may be overestimated for the groups that most benefit from interactions with those institutions and underestimated for those groups that gain less advantage or experience harm in those interactions.

We take as a case study the example of extant research on the effect of single compared to married parenthood on Black and White children’s and young adults’ outcomes in the United States. We illustrate how this research can be deepened and illuminated by explicitly situating Black and White families in the context of a structurally racist, heteropatriarchal society. We then present a new conceptual model that integrates explicitly the effects of structural racism and heteropatriarchal forces on each step on the causal pathway between family structure and child outcomes. We conclude with recommendations to improve the research paradigm to account for structural racism and interlinked heteropatriarchy through analytic approaches, measurement, and interpretation of the meaning of family structure for children’s outcomes in a racially stratified and unequal society.

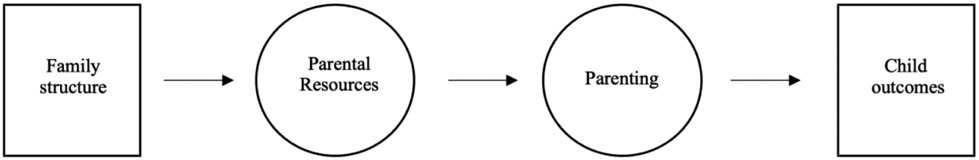

The Predominant Conceptual Model: The Family Resource Perspective

The family resource perspective is the predominant conceptual model used to explain the link between family structure and child outcomes. This perspective focuses on how the resources required for children’s growth and development differ substantially by family type. As depicted in Figure 1 below, researchers have posited that family structure impacts children’s life chances through two distinct (but not mutually exclusive) pathways: economic resources and parenting practices (McLanahan & Percheski, 2008; S. Brown, 2010; Powell et al., 2016). With respect to economic resources, scholars note that children living in HNFs typically have access to greater economic resources such as income and wealth than children raised in other contexts. High levels of income and wealth (as well as intergenerational wealth transfers) enable parents to purchase access to an array of social goods such as high-quality schools, safe neighborhoods, and services (including racialized and exploitative domestic labor), whereas financial precarity impedes upon other parents’ ability to provide the material goods and services that children need to thrive (Amato, 2005; Choi et al., 2018; McLanahan & Percheski, 2008). Support for the argument that economic resources mediate the relationship between family structure and child outcomes can be found in the fact that the correlation between these two factors decreases by approximately 50-65% after family income is taken into account (Brand et al., 2019; Brown, 2010; McLanahan & Sandefur, 1994).

Figure 1.

Predominant Conceptual Model Linking Family Structure to Child Outcomes

Model adapted from McLanahan and Percheski (2008)

The argument related to parenting practices hinges on the idea that good, consistent parenting, which leads to better child outcomes, is contingent on parents’ time, mental health, and money. Children who live apart from a parent generally receive less monitoring and supervision than children who grow up with both biological parents; this is especially the case among youth raised in single-parent families, who typically have fewer adults present in their homes to care for them (Kalil et al., 2014; McLanahan & Percheski, 2008). Research also suggests that single- step-, and cohabiting families tend to have a weaker and more ambiguous parental authority structure compared to HNFs, which can lead to inconsistent parenting (Cherlin & Furstenburg, 1994; Kalil et al., 2014; McLanahan & Percheski, 2008). Moreover, divorce and single parenthood may compromise the mental well-being of parents by inducing short-term stress and engendering the conditions for chronic stress, which may reduce parenting quality (McLanahan & Percheski, 2008). Lastly, good parenting is determined, in part, by parents’ economic resources. As previously mentioned, economic precarity due to structural inequalities reduces the level of material resources and services that parents can provide to children; it can also be an acute stressor for parents, both of which may undermine parenting quality. Results from a number of empirical studies show that differences in parenting practices between two-parent and single-parent families account for roughly 10-15% of the gap in child outcomes (e.g., Carlson, 2006; Thomson, McLanahan, & Curtin 1992), which lends support to the idea that parenting practices mediate the relationship between family structure and children’s life chances.

Racialized difference in the predominant conceptual model

Though the current conceptual model helps us see inside the black box of family structure to uncover the main pathways through which family structure impacts child outcomes, we note its limited generalizability. In particular, this framework does not adequately account for heterogeneity in the effect of family structure on children of color, especially Black youth. Although researchers consistently observe a negative effect of parental absence from children’s households on children’s academic, behavioral, and psychological well-being, a growing literature finds significantly weaker and often null associations between family structure and the well-being of children of color (e.g., Brand et al., 2019; Cross, 2020; Cross, 2021; Fomby et al., 2010; Sun & Li, 2007). In fact, in their meta-analysis of research on the long-term effects of divorce, Amato and Keith (1991) concluded that the negative impact of divorce on child outcomes was substantially greater for White than Black youth. Additionally, Dunifon and Kowaleski-Jones (2002) found that single parenthood was associated with increased delinquency for White, but not Black children. In a similar vein, Fomby et al. (2010) observed a weaker association between family structure transitions and Black adolescents’ risk behavior. More recently, Brand et al. (2019) noted that while parental divorce had a negative effect on White children’s college enrollment and completion, it did not lower the educational attainment of children of color, and Cross (2020) found that the negative impact of parental absence was substantially weaker for Black youth’s high school completion than their White peers.

Beyond the observed weaker associations of family structure on children’s outcomes in Black compared to White families, the family resource perspective is less effective as an explanation of family structure’s associations in Black families, a pattern that we argue is attributable to structural racism and heteropatriarchal forces that are unobserved in the conventional model. With regard to economic resources, for example, while poverty rates are lower and median family income is higher in married-parent compared to single-parent families across racial and ethnic groups, the income gains to marriage are smaller for Black compared to White families (Brown, 2021; Bureau of the Census, 2020). The Black-White wealth gap among married adults of childbearing age with or without a college education is even more acute (Darity, Jr. et al., 2018) and equally persistent (Aliprantis & Carroll, 2019). Further, even in Black families with moderate income, children are substantially more likely than their White counterparts to earn less and to accumulate less wealth than their parents when they reach adulthood, a pattern of downward intergenerational mobility that holds irrespective of parents’ marital status and that is particularly strong for Black boys (Pfeffer & Killewald, 2019). Thus, the economic gains to marriage and the economic costs to living with a single parent compared to a married one are unequal for children in Black and White families. A substantial literature suggests that these weaker gains are not the result of group differences in the attributes of Black compared to White families, but to enduring group differences in school quality, educational achievement, employment opportunity and discrimination, labor force attachment, and contact with the carceral system that contribute to Black men’s lower earnings and availability for marriage relative to White men’s (Pager et al., 2009; Pager, 2003; Sellers & Shelton, 2003; Wilson, 1987). Research models that overlook such racial variation in attachment to and engagement with social and economic institutions beyond the household introduce a profound problem of omitted variable bias that potentially misspecifies the effect of family structure on children’s well-being and contributes to policies that are misaligned with population need (Fomby 2022).

Similarly, parenting behaviors that are considered to be conducive to children’s productive development also have weaker direct associations with children’s outcomes and are weaker mediators of family structure’s effects in Black compared to White families. One example is parenting style, defined by the balance of strictness and emotional warmth that parents demonstrate to children in everyday interactions. Parenting style is widely used to explain population variation in behavior problems (Pinquart, 2017) and academic achievement (Pinquart, 2016), including as a hypothesized mediator of the relationship between family structure and child and adolescent outcomes (Bastaits & Mortelmans, 2016; Fine et al., 1993). But in the US context, authoritative parenting, characterized by the presence of both strictness and emotional warmth in parents’ interactions with children, is more weakly associated with child behavior problems and academic achievement in Black compared to White families, and authoritarian parenting, characterized by strictness and less frequent emotional warmth, is not associated with these outcomes for Black children in meta-analyses (Pinquart & Kauser, 2018; Deater-Deckard et al., 2011). This pattern may reflect true group differences or may be attributable to racial bias in measurement. The construct of parenting style was developed from laboratory- and home-based observation of child-parent interactions in convenience or clinical samples during the mid-20th century (Baumrind, 1966; Maccoby & Martin 1983), and subsequent work has demonstrated that it lacks comparable salience outside of the U.S. and even among non-White families within the U.S. Similar criticisms of racial bias have been made against the standard measurement of self-reported mental health, stress appraisal, and genetic expression to explain why these constructs appear to operate differently on family functioning and well-being in Black compared to White families (L. Brown et al., 2019; Rosenfield & Mouzon, 2013; Henrich et al., 2010).

There are at least two other features of Black compared to White family organization rooted in structural racism and heteropatriarchal forces that we argue contribute to the weaker predictive power of the family resource perspective for children’s outcomes. The first is that measurement of family structure that focuses on the HNF overlooks the presence of coresident extended kin such as grandparents and aunts or uncles as well as the proximity and involvement of non-coresident kin and friends in active social networks. As noted above, however, the retreat from these forms of household organization and exchange among White middle- and upper-middle class families is relatively recent, and recent quantitative work and a large body of qualitative research have highlighted the continued salience of these relationships in Black family life across the socioeconomic spectrum (Cross, 2018; Perkins, 2019; Pilkauskas & Cross, 2018; Taylor et al., 2021). This work also illustrates that in contemporary families, such relationships are neutral or positive for the well-being of Black youth, but more often associated with deleterious outcomes for White youth, largely because of differential selection into extended kin coresidence and activation of social networks by race (Cross 2020; Fomby et al., 2010; Mollborn, Fomby & Dennis 2011).

A second feature is inattention to differential selection into family structures including single parenthood and marriage. Social science scholarship is well-attuned to selection, or the expectation that characteristics of individuals that are present prior to their own family formation may be related both to their family structure trajectories and to their children’s outcomes. That is, any observed relationship between family structure and children’s outcomes may be spurious and driven by common antecedent causes. What is less widely recognized is that selection into family structure operates differently for Black and White adults. In particular, among White people, characteristics and experiences such as educational attainment, illegal behavior, or parental union dissolution during childhood are associated with a lower likelihood of marriage or union stability in adulthood, and these background characteristics are also associated with their own children’s outcomes. But among Black adults, the same characteristics are not associated with likelihood of marriage or union instability (Fomby & Cherlin 2007; Lee & McLanahan 2015; D. T. Williams 2021). Rather, the likelihood of marriage or union stability is more similar among Black people than among White people regardless of personal characteristics. Thus, selection mechanisms are a much more powerful explanation for sorting into family structure among White than among Black adults. When this distinction is overlooked, researchers risk applying erroneous conclusions about selection mechanisms to populations where they do not apply. This error has the potential to be particularly dangerous in the context of structural oppression, where Black families’ lower marriage rates may be falsely attributed to personal characteristics and choice, rather than to the structurally racist and heteropatriarchal policies, laws, and ideologies that prevail over union formation.

We argue that the predominant conceptual model’s inability to adequately predict and explain these racial differences in the impact of single parenthood and parental divorce or separation arise from its narrow focus on individual- and family-level factors (e.g., parents’ mental health or family income), while overlooking the role of macro-level factors (e.g., mass incarceration, housing segregation) in shaping the types of families that children are sorted into and the level of resources available to them within their families. Put differently, the predominant conceptual model largely treats the relationship between family structure and child outcomes as unbounded from or incidental to the larger societal contexts within which families operate. Family structure is positioned as a choice made by individuals, unaffected and unimpeded by the social, legal, and economic institutions with which they interact.

To be sure, it is standard practice for scholars to control for individual-level background characteristics (e.g., education level) that “select” individuals into various types of families in order to isolate the direct or indirect effects of family structure. However, the institutional arrangements that contribute to differential selection in the first place are routinely omitted from mainstream conceptual and empirical models. Because macro-level factors are not taken into account, these approaches will not be able to resolve the question of why family structure effects apparently vary across population subgroups.

The Costs of the Predominant Conceptual Model: Black Family Harms

As Jensen and Sanner (2021) conclude in their scoping review of the extant research on well-being across diverse family structures, “[t]he inherent and unchallenged bias toward the nuclear family model looms large in this literature” (p. 15). Jensen and Sanner (2021) further conclude that the body of research focused on family structure and child outcomes is devoid of theoretical guidance, and would benefit from the integration of critical theories (e.g., critical race, feminist, queer theories). So powerful is the “traditional nuclear family is best” ideology that it appears to drive the discourse seemingly unchecked. Comparisons of child outcomes by family structure statuses use the HNF model as the gold standard upon which other statuses are compared, setting up deficit-based narratives. And racist cultural tropes born out of this politicized discourse serve to denigrate Black mothers solely heading their families as a “blight” to the health of our nation (Bailey et al., 2021) and a threat to the social order (Smith, 2016). The promotion of heteropatriachal nuclear families in a White supremacist society built upon structural racism is costly to those who are systematically disadvantaged by it. Indeed, “race-neutral” promotion of marriage fundamentalism or HNF undergirds many U.S. social policies, including access to family and medical leave, health insurance, and many benefits built into the U.S. tax code (Brown, 2021; Fremstad et al., 2019; Letiecq et al., 2013), to the detriment of minoritized families historically and currently marginalized as a function of structural oppression.

Take for example the U.S.’ primary program for providing cash assistance to low-income families with children, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF). Three of the four goals of TANF center the primacy of marriage and parental responsibility as fundamental to poverty reduction in the U.S. (e.g., promotion of marriage, abstinence until marriage, and responsible fatherhood; U.S. House of Representatives, 1996). While created through federal legislation and largely funded through a federal block grant, states exercise broad discretion in determining TANF eligibility, the share of funds that are allocated towards cash assistance versus other social programs, and setting benefit levels (U.S. House of Representatives, 1996). States with the largest percentages of Black Americans (i.e., southern states) tend to spend a significantly higher share of TANF funds on marriage promotion activities (e.g., counseling about marital stability and healthy relationships) instead of providing direct cash assistance to families in need (Floyd et al., 2021; Monnat, 2010; Parolin, 2021). Consequently, compared to poor White families, poor Black families are more likely to receive assistance via a government “Healthy Marriage Initiative," rather than receiving money to help meet their basic needs (Parolin, 2021). These disparities in TANF benefit receipt are estimated to contribute up to 15% of the Black-White child poverty gap (Parolin, 2021).

Inserting Structural Racism and Heteropatriarchy into the Narrative: A New Conceptual Model

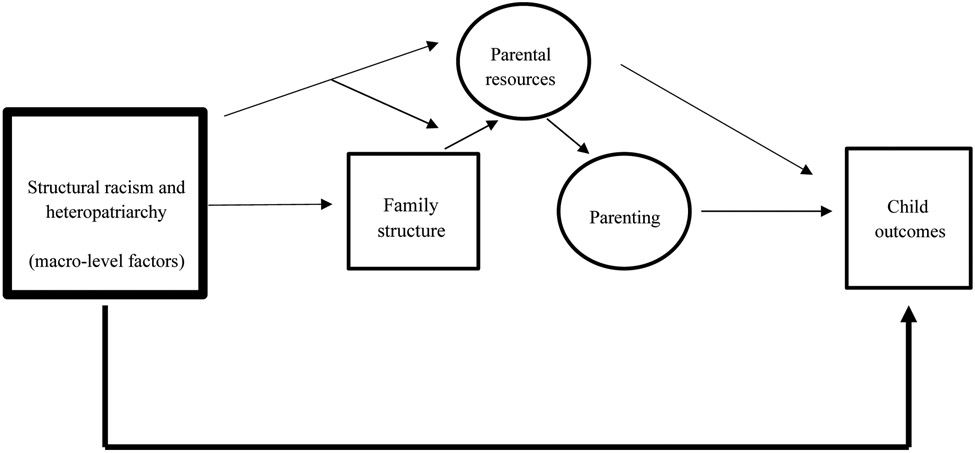

While the aforementioned example focused on a particular sector of society (government), structural racism and heteropatriarchal forces are ubiquitous, present in every area of a society whose establishment and maintenance depends on the exploitation of minoritized groups, like the U.S. (Bonilla-Silva, 1997; Pirtle, 2020). Thus, children and their families are not beyond the grip of these forces, and this must be taken into account when studying the role of family structure in shaping youth outcomes. We propose an alternative conceptual model (See Figure 2) that incorporates and expands upon key tenets of the family resource perspective to explicitly incorporate the influence of structural racism and heteropatriarchy. While we place emphasis on these pillars of White supremacy, our overarching goal is to draw attention to how previously omitted macro-level factors condition the relationship between family structure and child outcomes. In our view, any macro-level factor that differentially selects children into various familial configurations and leads to variation in the distribution of resources across families—be it on the basis of race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, class, or some other individual-level characteristic—has the ability to produce heterogeneity in the impact of family structure on child well-being. Further, macro-level factors may not operate additively, but instead may interlink and reinforce each other in ways that yield multiplicative effects. While we agree with the prevailing conceptual model’s articulation of parental resources and parenting practice as key mediators of the relationship between family structure and child well-being (McLanahan & Percheski, 2008), we critique its omission of macro-level factors like structural racism and heteropatriarchy that condition the relationship between family structure and each of these mediators (Burton et al., 2010; Pinquart & Kauser, 2018; Williams & Baker, 2021). We also acknowledge the negative influence of structural racism and interlinked heteropatriarchy on the well-being of children of color, independent of the family structure in which they are reared (Garcia Coll et al., 1996).

Figure 2.

New Conceptual Model Integrating Structural Racism and Heteropatriarchy as Macro-Level Factors Conditioning Family Structure and Child Outcomes

We identify three key pathways through which structural racism and heteropatriarchy shape the relationship between family structure and Black youth’s outcomes. First, we propose that these structural, macro-level forces directly influence the types of families that Black children are sorted into, which are often families that are resource-deprived (e.g., single-parent families) (Figure 2). The carceral system offers one useful example of this macro-level sorting influence. Increasingly, researchers have drawn strong links between incarceration and racial differences in family structure. Due to racially discriminatory policies and practices (e.g., racial profiling), Black Americans, and disproportionately Black men, experience higher rates of arrest and incarceration and face longer sentences than their White American counterparts—despite there being virtually no difference in their crime rates (Alexander, 2010; Western, 2006). These racialized and gendered inequities in punishment remove Black men from society at dramatically higher rates than White men, thereby reducing the number of Black men available to participate in marriage, cohabitation, childrearing, or family carework. Incarceration also increases Black men’s likelihood of experiencing union dissolution if they are partnered (Haskins & Lee, 2016; Wakefield et al., 2016; Western, 2006). Given that 12% of Black children have a parent who is incarcerated (most often their father), relative to 6% of White children (Murphy & Cooper, 2015), it is not difficult to see how racist and gendered policies and practices within the carceral system contribute to higher rates of parental divorce and separation for this group compared to White children.

Second, we posit that structural racism and heteropatriarchy directly influence parental resources like income and mental and physical health (Figure 2). Consider again our example of the carceral system. It is well established that incarceration negatively and profoundly influences individuals’ long-term employment opportunities and wages. Employers are often reluctant to hire applicants with criminal records (Pager & Quillian, 2005); formerly incarcerated persons who find work tend to be concentrated in low-wage sectors, and their incarceration history may disqualify them from receiving access to financial assistance via the social safety net (Haskins & Lee, 2016; Western, 2006). Additionally, the experience of incarceration may take a toll on individuals’ mental and physical health via the stress, stigma, social isolation, and financial strain that frequently accompany this negative life event (Haskins & Lee, 2016; Sewell et al., 2016; Wakefield et al., 2016). Further, research suggests that incarceration can lead to mental health challenges for the relatives of those imprisoned. In particular, paternal incarceration has been shown to increase maternal depression (Lee & Wildeman, 2021). In this way, parental incarceration, which disproportionately affects Black children, elevates their risk of experiencing loss in family income and/or having a parent with compromised mental and physical health.

Finally, we assert that structural racism and heteropatriarchal forces directly affect Black children’s outcomes independent of family-level characteristics such as family income (Figure 2). We return to our example from the carceral system to illustrate this final point. While incarceration can negatively impact Black youth via their parents, they themselves are more likely to be in contact with this institution than White children. For example, compared to White boys, Black boys are nearly twice as likely to be stopped by police (23% vs. 39%; Geller, 2018). Much of this difference in exposure to police can be attributed to aggressive policing practices such as broken-windows policing, which focus on stringent punishment for low-level crimes and extensive use of pedestrian stops that are targeted at neighborhoods of color (Fagan et al. 2016; Legewie & Fagan, 2019; Weisburd & Majmundar, 2018). In their recent study, Legewie and Fagan (2019) presented the first casual evidence of the impact of aggressive policing for minoritized youth, showing that exposure to police significantly reduced the test scores and school attendance of Black boys, which likely perpetuates racial and gender disparities in academic achievement. As this brief example demonstrates, structural racism and heteropatriarchal forces can negatively influence the well-being of Black youth, irrespective of the types of families they grow up in.

We maintain that structural racism and heteropatriarchy’s differential selection of Black children into family structures that tend to have fewer parental resources (e.g., single-parent families), their direct reduction of resources to Black families across all family types, and their independent and negative effect on Black youth outcomes help address the question of why the relationship between family structure and child well-being differs by racial group membership (Brown, 2021; Collins, 1998; Garcia Coll et al., 1996; Powell et al., 2016). If structural racism and heteropatriarchy interlink to diminish the availability of parental resources for minoritized groups like Black Americans, then the relative gap in resources between Black children living in HNFs compared to those in other family types is substantially lower than that between White children raised in HNFs relative to other familial configurations. Provided that parental resources largely mediate the relationship between family structure and child outcomes—as specified by the predominant conceptual model (Figure 1)—the relative difference in outcomes by family structure would then be smaller for Black than White children. Further, Black children’s well-being is likely directly compromised by experiences of structural racism and heteropatriarchy, regardless of the type of family that they live in and the level of resources available within their households (Garcia Coll et al., 2016). Research models that overlook variation in how macro-level factors (e.g., structural racism) produce advantages for one group (White Americans), at the expense of other groups (e.g., Black Americans), likely overestimate the gains to living in a two-parent family or the costs associated with living outside of it.

A Call for Just and Anti-Racist Approaches and Research Methods

Given the widening and deepening understanding of how structural racism and heteropatriarchy work (to varying degrees) to disadvantage and diminish Black children and their families while simultaneously advantaging White children and their families, we call for new, more just and anti-racist approaches to family science. This paradigm shift work, particularly with regard to explanatory models linking family structure to child outcomes, began in the 1960s, largely driven by Black family scholars concerned about the harms that would befall the Black community should deficit perspectives applied to family structure diversity take root (e.g., Billingsley, 1968; Ladner, 1973). Tragically, looking across systems (e.g., employment, housing, education, criminal justice, child welfare) at racialized familial outcomes, their worries were prescient (Bailey et al., 2021; Roberts, 1996; D. R. Williams et al., 2019). Thus, it is imperative that family scholars—and especially White family scholars—reconsider their research questions, approaches, measurements, and interpretations of the meanings of family structure in family life. This work requires the full integration of structural racism and heteropatriarchy into the narratives of Black and White family experiences in a society built to reproduce and sustain White supremacy.

Positionality of the Researcher in Relation to the Researched

One critique of scientific approaches to the study of minoritized and marginalized families is the positional distance of the researcher from the “subjects" of the research. (White) researchers claiming a neutral, objective, unbiased gaze while studying Black families have too often failed to fully integrate the racialized and unequal context of Black families in a racist, heteropatriarchal, White supremacist society. To redress these oversights, family scholars must reflexively consider their positionality and power relations and the ways in which they have been socialized to believe (and likely benefited from) the “traditional nuclear model as best” ideology that pervades family discourse. As we posit in this article, U.S. heteropatriarchal marriage fundamentalism cannot be disentangled from structural racism (see also Fremstad et al., 2019). Family scholars must bracket their assumptions regarding the salience of family structure for child well-being and, guided by critical and intersectional theories, attend to unanswered research questions regarding the effects of family privilege and HNF supremacy (Letiecq, 2019). For example, how have well-off White HNFs been advantaged by U.S. laws and policies, including the U.S. tax code, over time and how have those families been able to use intergenerational wealth transfers to reproduce White family advantage and structural supremacy (Bellisle et al., 2021)? What are the mechanisms of structural racism and heteropatriarchy that condition individual selection and resource allocation into different family structures and how do they operate? What systemic reforms are needed to repair the familial harms associated with structural oppression?

Anti-Racist Research Approaches: Intersectional Collaborations

Beyond researcher reflexivity, we urge family scholars to engage, at a minimum, in intersectional collaborations that transcend disciplinary and academic boundaries. Such collaborations are critical, particularly among scholars engaging in research on (and not with) minoritized and marginalized communities, and especially if they are not members of these communities. Intersectional collaborations can take place within the academy, where family scholars build interdisciplinary networks to include diverse and critical researchers with expertise in multiple methodologies. These networks should be grounded in both allyship (where those with intersectional privilege support those marginalized in the academy by race, class, gender, and sexuality) and accompliceship (where scholars jeopardize their own unearned privileges and take action for systemic change; Anderson, 2019; Harden-Moore, 2020). Family scholars (and especially those engaging in secondary analysis of national datasets) should look beyond the academy to build advisory boards made up of the families they are investigating. Advisors can serve as a sounding board, providing feedback regarding researcher assumptions, knowledge claims, interpretations of findings, and assertions about causal pathways. Importantly, this work should not be exploitative nor extractive, and should directly benefit the advisors (at the very least, through compensation and recognition).

Beyond postpositivist research approaches, scholars should pursue anti-racist approaches and methods (Collins, 2019; Smith, 2021), such as participatory action research (PAR) (Henderson et al., 2017; Letiecq et al., in press). Anti-racist PAR approaches require at the base trusted partnerships between university researchers and community partners (i.e., families) and should be driven by communities of color such that the research is of, by, and for (in this case) Black families and their well-being. PAR approaches can utilize a variety of research methodologies, including quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods. However, PAR approaches should engage co-researchers (e.g., Black families) throughout the research process, including question development, survey design, analytical approaches, interpretation of the data, and dissemination of findings (Letiecq et al., in press; Reason & Bradbury, 2008; Wallerstein et al., 2018). It can be challenging to implement PAR and other critical, anti-racist approaches, especially in an academy that privileges “traditional” forms of research engagement (e.g., where the researcher is the expert); however, as calls for new, collaborative, multi-method, and participatory approaches grow louder, shifts in funding schemes and academic expectations are changing (Letiecq et al., in press). Significantly, there are new and emerging centers for anti-racist research being established at institutions of higher education across the country. These centers hold promise in supporting new approaches to family scholarship that continue to expose structural racism, heteropatriarchy, and other interlinked macro-forces and advance structural change to the benefit of families of color.

Measurement and Meaning Making in Family Demography

We conclude our call for anti-racist research by centering on measurement and meaning-making, particularly as it relates to family demography. The field of family demography, a subfield that spans the social science disciplines, often relies upon large nationally representative datasets to examine patterns in family life. Importantly, some family demographers have begun to engage in a reflexive dialogue problematizing the use of race as an immutable characteristic rather than a socially constructed variable measuring racism in America (e.g., Williams & Baker, 2021; Zuberi & Bonilla-Silva, 2008). Some have also employed Quantitative Criticalism (QuantCrit) in family research. QuantCrit is an analytic framework based on critical race theory that challenges normative, racialized assumptions and the neutrality of data used in quantitative research (Curtis & Boe, 2021). These are critical steps in analytical approaches to the study of Black children, youth and families. However, we would argue that measures of family structure are also socially constructed and, as Jensen and Sanner (2021) recently suggested, have failed to fully capture the complexity and diversity of dynamic family structures formed through biological, legal, or social relatedness within and between households over time. There is also a growing recognition of the exclusion of data and methods required to observe and interpret the effects of structural racism on family structure within national datasets. We acknowledge the growing recognition of these methodological challenges within the family science field and demography more broadly and are inspired by changes already underway.

Informed by measurement and methodological advances made largely within the health sciences, we identify several avenues through which family demographers can better integrate structural racism and heteropatriarchal forces into empirical models. Recently, scholars examining the contributions of racism to ethnoracial inequalities in health have developed both single-item proxies and multi-indicator scales to capture the effects of structural racism (e.g., Adkins-Jackson et al., 2021; Dougherty, 2020; Sewell, 2021). Single-item measures can be captured at the individual-, meso- and macro-level. Individual-level items may include self-reports of perceived discrimination in a variety of institutional settings (e.g., schools or healthcare facilities). Some national household studies already include reports of perceived discrimination that could be incorporated into models. For example, the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) Transition into Adulthood Supplement and the Health and Retirement Study include the Everyday Discrimination Scale (D. R. Williams, Jackson, and Anderson 1997), a series of questions related to unfair treatment and asks respondents about potential reasons for mistreatment (e.g., on the basis of race, age, or gender). Audit studies offer another avenue for researchers to examine how the individual-level discriminatory preferences and practices of members of dominant groups shape the labor market opportunities and residential choices of parents from marginalized backgrounds (Hansen and Hawley, 2011; Pager and Shepherd, 2008).

Structural racism, of course, cannot be entirely captured by individual-level reports of racial discrimination. By definition, structural racism operates at a systemic level and can influence an individual’s life chances even if it escapes conscious recognition. Further, even if an individual is aware that they are being discriminated against, it may be difficult for them to ascertain and accurately attribute that negative experience to their racial background per se. At the meso- and macro-levels, researchers have endeavored to develop place-based, single-item indicators of structural racism. For example, measures of racial residential segregation, such as the dissimilarity index, can provide useful information about the larger racialized societal context within which families are operating and the degree of racial inequality (brought on by structural racism) that is present. County-level measures of racial inequality in homeownership, racial mortgage discrimination (Sewell, 2021), or historical racial slaveholding (Baker & O’Connell, in press) have also been developed by researchers to accomplish similar goals (also see Adkins-Jackson et al., 2021; Dougherty, 2020; Groos, Wallace, & Hardeman, 2018). State- and county-level variation in the extent or timing of policy implementation in programs such as TANF, Medicaid expansion, public transportation accessibility, and early child education also provide insight into axes of racialized inequality.

Ideally, multi-indicator scales that encapsulate the multidimensional nature of structural racism across institutions and sectors of society can be implemented into quantitative family research. A recent example from Dougherty et al. (2020) focused on five key sectors - housing, education, employment, healthcare, and criminal justice - to develop a multidimensional scale of structural racism. Their approach measured the racial composition of schools and neighborhoods relative to composition at the county level and constructed ratios of the incidence of events (e.g., arrests) experienced by White county residents compared to people of color. Baker (forthcoming) constructed a novel measure of the U.S.’ historical racial regime. It captures historic levels of slavery, sharecropping, disenfranchisement, and segregation within states, and it can be used to assess the long-term effects of structural racism on families today. While indices like these are relatively new, and many national household studies do not include multilevel and multidimensional variables such as these, they offer breadcrumbs for future work in the area of family studies. For example, family researchers using geocoded data in secondary datasets could consider harmonizing their individual- and family-level data with external datasets that include measures of place-based racial inequality (e.g., Census data or state-level crime data bases). Family scientists might also be inspired to add indicators of structural racism to ongoing national household studies or to develop new studies informed by PAR.

Research on how ambient sexism and entrenched heteropatriarchal systems affect adults’ family formation behaviors can also guide measurement on how these forces contribute to racialized differences in children’s family structure experience. With regard to sexism, a recent example from Charles, Guryan, and Pan (2018) demonstrated that childhood and adult exposure to state-level sexist attitudes about women’s employment are each predictive of women’s earlier childbearing and marriage and their lower labor force participation and wages. All of these factors may influence children’s family composition, family resources, and parenting. To directly engage both the heteronormative and patriarchal norms that undergird structural heteropatriarchy, Everett and colleagues (2021) created a holistic scale that included state and county measures of men’s compared to women’s earnings, labor force participation, and unemployment rates. It also included indicators of voting behavior, conservative religiosity, abortion access and policy, and policies pertaining to lesbian, gay, and bisexual equality. Residence in a locality with a higher score on the structural heteropatriarchy scale was predictive of women’s increased risk of preterm birth and lower birthweight irrespective of sexual orientation or gender identity, suggesting that these environments are harmful to women’s reproductive health regardless of whether they are the “targets” of discriminatory policies and practices. This perspective may also be usefully brought to bear on the context in which children experience family organization.

Even in the absence of direct measures of structural racism or heteropatriarchy, family demographers can incorporate their effects on family formation and family process using individual-level data. For example, in order to capture differential selection into family structure by race, researchers should stratify empirical models by racialized identity or interact racialized identity with indicators of hypothesized selection mechanisms. Research questions that focus on variation in family structure and family process within racialized groups can control for group members’ position in structurally racist, heteropatriarchal systems and yield new insights beyond those gained from between-racialized group comparisons. Researchers can also “flip” the deficit framing that underlies the predominant conceptual model to consider how structural racism and heteropatriarchy advantage White families through family structure and family resources rather than to investigate where Black families are falling short. Future work can also consider how other macro-level factors (e.g., capitalism, neoliberalism, and nationalism) interlink with these structural forces to produce varying degrees of advantage and disadvantage within all racial groups, subsequently shaping family structure effects. Lastly, when researchers observe racialized group differences in entry into family structure, in family structure effects on children, or in children’s outcomes that cannot be explained by the components of their statistical models, they can think more critically about how structural racism and heteropatriarchy might explain the residual. In particular, rather than attributing unexplained group differences to abstract cultural differences, scholarship that proposes structural explanations can help to generate new research directions.

At a minimum, acknowledging structural racism and heteropatriarchy as forces acting upon all families to advantage one racial group (White Americans) over others will be crucial to the interpretation of quantitative findings focused on family structure effects. If relevant measures cannot be included, recognizing the omission of these factors is critical to our interpretation of the consequences of family structure for child well-being.

Conclusion

For too long, scholars of family life have utilized conceptual and analytical models explaining family structure linkages to child well-being that ignore and/or fail to integrate the forces of structural racism interlinked with heteropatriarchy on Black family experiences. These limited models have skewed our understanding of the ways in which Black people do family and resist their structural oppression in a White supremacist society (Burton et al., 2010; Collins, 1998; Few, 2007). Even more egregious, these reductive models have perpetuated deficit-based perspectives used to justify racist laws, policies and practices that have further entrapped Black families in interlocking systems of oppression, resulting in incalculable losses and institutional betrayals (Brown, 2021; Fremstead & Williams, 2019; Letiecq, 2019; Zuberi & Bonilla-Silva, 2008. In this article, we present a new conceptual model that integrates structural racism and heteropatriarchy as critical factors in explaining family structure and child outcomes. We also call for new approaches, measurement strategies, and interpretations of findings that further instantiate structural racism and heteropatriarchy as critical factors in the structuring of Black and White family life. More work is needed to refine models and consider more pointedly the intersections of structural racism and heteropatriarchy (and other pillars of White supremacy, including genocide and capitalism; see Smith, 2016), but our model adds to the paradigmatic shift work that is required to advance a more just and anti-racist family science.

Contributor Information

Christina Cross, Harvard University.

Paula Fomby, University of Colorado.

Bethany L Letiecq, George Mason University.

References

- Adkins-Jackson PB, Chantarat T, Bailey Z, & Ponce N (2021). Measuring structural racism: a guide for epidemiologists and other health researchers. American Journal of Epidemiology, Online First. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander M. (2010). The new Jim Crow: Mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness. New Press. [Google Scholar]

- Aliprantis D & Carroll DR (2019). What Is Behind the Persistence of the Racial Wealth Gap? Economic Commentary, no. 2019–03 (February). 10.26509/frbc-ec-201903. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR (2005). The impact of family formation change on the cognitive, social, and emotional well-being of the next generation. The Future of Children, 15(2), 75–96. DOI: 10.1353/foc.2005.0012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR, & Keith B (1991). Parental divorce and adult well-being: A meta-analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family, 53(1), 43–58. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson LA (2019). Rethinking Resilience Theory in African American Families: Fostering Positive Adaptations and Transformative Social Justice. Journal of Family Theory and Review, 11(3), 385–397. 10.1111/jftr.12343 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey ZD, Feldman JM, & Bassett MT (2021). How Structural Racism Works — Racist Policies as a Root Cause of U.S. Racial Health Inequities. New England Journal of Medicine, 384, 768–773. 10.1056/NEJMms2025396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker Regina S. Forthcoming. The historical racial regime and racial inequality in poverty in the American South. American Journal of Sociology. [Google Scholar]

- Baker Regina S. and O'Connell Heather A.. In press. Structural racism, family structure, and black-white inequality: The differential impact of the legacy of slavery on poverty among single mother and married parent households. Journal of Marriage and Family. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes R, & Josefowitz N (2019). Indian residential schools in Canada: Persistent impacts on Aboriginal students’ psychological development and functioning. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie canadienne, 60(2), 65–76. 10.1037/cap0000154 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bastaits K & Mortelmans D (2016). Parenting as Mediator Between Post-Divorce Family Structure and Children’s Well-Being. Journal of Child and Family Studies 25 (7): 2178–88. 10.1007/s10826-016-0395-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D (1966). Effects of Authoritative Parental Control on Child Behavior. Child Development 37 (4): 887–907. 10.2307/1126611. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bellisle D, Harty J, & Letiecq B (2021). Dismantling Structural Racism and White Nuclear Family Hegemony in the Tax Code. NCFR Report. National Council on Family Relations: Minneapolis, MN. [Google Scholar]

- Billingsley A (1968). Black families in white America. New York: Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla-Silva E (1997). Rethinking racism: Toward a structural interpretation. American Sociological Review, 62(3): 465–480. [Google Scholar]

- Brand JE, Moore R, Song X, & Xie Y (2019). Why does parental divorce lower children’s educational attainment? A causal mediation analysis. Sociological Science, 6, 264–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown D (2021). The whiteness of wealth: How the tax system impoverishes Black Americans—and how we can fix it. New York: Crown. [Google Scholar]

- Brown L, Abrams L, Mitchell U, and Ailshire J (2019). Black-White Differences in Chronic Stress: Does Appraisal Matter for Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms? Innovation in Aging 3 (Suppl 1): S191–92. 10.1093/geroni/igz038.688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SL (2010). Marriage and child well-being: Research and policy perspectives. Journal of Marriage and Family 72, 1059–1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of the Census (2020). Historical Income Tables: Familes [Table F-7]. Washington, DC: Department of Commerce. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/income-poverty/historical-income-families.html. [Google Scholar]

- Burton LM, Bonilla-Silva E, Ray V, Buckelew R, & Freeman EH (2010). Critical race theories, colorism, and the decade’s research on families of color. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 440–459. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00712.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson MJ (2006). Family structure, father involvement, and adolescent behavioral outcomes. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68(1): 137–154. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll G (1998). Mundane Extreme Environmental Stress and African American Families: A Case for Recognizing Different Realities. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 29(2), 271–284. 10.3138/jcfs.29.2.271 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh S, & Fomby P (2019). Family Instability in the Lives of American Children. Annual Review of Sociology, 45, 493–513. 10.1146/annurev-soc-073018-022633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chetty R, Hendren N, Jones MR, and Porter SR (2020). “Race and Economic Opportunity in the United States: An Intergenerational Perspective.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 135 (2): 711–83. 10.1093/qje/qjz042 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin A, Furstenberg F (1994). Stepfamilies in the United States – A reconsideration. Annual Review of Sociology 20, 359–381. [Google Scholar]

- Chishti M & Pierce S (2021). Border Déjà Vu: Biden Confronts Similar Challenges as His Predecessors. Migration Policy Institute, Policy Beat. Retrieved from https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/border-deja-vu-biden-challenges [Google Scholar]

- Collins PH (1990). Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. Boston: Unwin Hyman. [Google Scholar]

- Collins PH (1998). Intersections of race, class, gender, and nation: Some implications for black family studies. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 29(1), 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Collins PH (2019). Intersectionality as a critical social theory. Duke University Press. 10.1515/9781478007098. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coontz S (1992). The Way We Never Were: American Families and the Nostalgia Trap. Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Choi J, Kelley MS, & Wang D. (2018). Neighborhood Characteristics, Maternal Parenting, and Health and Development of Children from Socioeconomically Disadvantaged Families. American Journal of Community Psychology, 62, 476–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw K (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989(1), 139–167. Retrieved from: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1052&context=uclf [Google Scholar]

- Cross CJ (2018). Extended family households among children in the United States: Differences by race/ethnicity and socio-economic status. Population Studies, 72(2), 235–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross CJ (2020). Racial/ethnic differences in the association between family structure and children's education. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(2), 691–712. [Google Scholar]

- Cross CJ (2021) Beyond the binary: Intraracial diversity in family organization and Black adolescents’ educational performance. Social Problems. 10.1093/socpro/spab050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis MG & Boe JL (2021). #QuantCrit: Integrating CRT with quantitative methods in family science. NCFR Report, 66.3, 15–18. National Council on Family Relations. [Google Scholar]

- Darity W Jr., Hamilton D, Paul M, Aja A, Price A, Moore A, & Chiopris C (2018). “What We Get Wrong About Closing the Racial Wealth Gap.” Durham, NC: Samuel DuBois Cook Center on Social Equity. [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Lansford JE, Malone PS, Alampay LP Sorbring E, Bacchini D, Bombi AS et al. (2011). “The Association between Parental Warmth and Control in Thirteen Cultural Groups.” Journal of Family Psychology 25 (5): 790–94. 10.1037/a0025120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty GB, Holden SH, Gross AL, Colantuoni E, & Dean LT (2020). Measuring structural racism and its association with BMI. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 59(4): 530–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dow DM (2019). Mothering while Black: Boundaries and burdens of middle-class parenthood (1st ed.). University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dunifon R, & Kowaleski-Jones L (2002). Who’s in the house? Race differences in cohabitation, single parenthood, and child development. Child Development, 73, 1249–1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everett BG, Limburg A, Homan P, and Philbin MM (2021). Structural Heteropatriarchy and Birth Outcomes in the United States. Demography, Advance Publication. https://read.dukeupress.edu/demography/article/doi/10.1215/00703370-9606030/286879/Structural-Heteropatriarchy-and-Birth-Outcomes-in [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan J, Braga AA, Brunson RK, & Pattavina A (2016). Stops and stares: Street stops, surveillance, and race in the new policing. Fordham Urban Law Journal 43(3): 539–614. [Google Scholar]

- Few A (2007). Integrating Black consciousness and critical race feminism into family studies research. Journal of Family Issues, 28, 452–473. [Google Scholar]

- Few-Demo AL (2014). Intersectionality as the “new” critical approach in feminist family studies: Evolving racial/ethnic feminisms and critical race theories. Journal of Family Theory and Review, 6, 169–183. doi: 10.1111/jftr.12039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Filisko GM (2016, June 1). After Obergefell: How the Supreme Court ruling on same-sex marriage has affected other areas of law. ABA Journal. https://www.abajournal.com/magazine/article/after_obergefell_how_the_supreme_court_ruling_on_same_sex_marriage_has_affe. [Google Scholar]

- Fine MA, Voydanoff P & Donnelly BW (1993). Relations between Parental Control and Warmth and Child Well-Being in Stepfamilies.” Journal of Family Psychology 7 (2): 222–32. 10.1037/0893-3200.7.2.222. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd I, Pavetti L, Meyer L, Safawi A, Schott L, Bellew E, & Magnus A (2021). TANF policies reflect racist legacy of cash assistance. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Fomby P (2022). Accounting for Race Differences in How Family Structure Shapes the Transition into Adulthood. In Kimmel J (Ed.). Intergenerational Mobility: How Gender, Race, and Family Structure Affect Adult Outcomes. Kalamazoo, MI: W.E. Upjohn Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Fomby P & Cherlin A (2007). Family Instability and Child Well-Being. American Sociological Review, 72(2): 181–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fomby P, Mollborn S, & Sennott C (2010). Race/ethnic differences in effects of family instability on adolescents’ risk behavior. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 234–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fremstad S, Glynn SJ, & Williams A (2019). The case against marriage fundamentalism:Embracing family justice for all. Washington, DC: Family Story. Retrieved from https://familystoryproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Case-Against-Marriage-Fundamentalism_Family-Story-Report_040419.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Coll CT, Lamberty G, Jenkins R, McAdoo HP, Crnic K, Wasik BH, & Vazquez Garcia H (1996). An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development, 67, 1891–1914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller A (2018). Policing America’s children: Police contact among teens in Fragile Families.” Fragile Families Working Paper WP18-02-FF. [Google Scholar]

- Goldscheider F & Bures RM (2003). The racial crossover in family complexity in the United States. Demography, 40(3): 569–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groos M, Wallace M & Hardeman R (2018). Measuring inequity: a systematic review of methods used to quantify structural racism. Journal of Health Disparities Research and Practice, 11(2): 190–206. [Google Scholar]

- Hanks A, Solomon D, & Weller CE (2018). Systematic inequality: How America’s structural racism helped create the Black-White wealth gap. Center for American Progress, Washington, DC. Retrieved October 26, 2021 from https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/race/reports/2018/02/21/447051/systematic-inequality/ [Google Scholar]

- Hansen A & Hawley Z (2011). Do landlords discriminate in the rental housing market? Evidence from an internet field experiment in US cities. Journal of Urban Economics, 70(2-3): 99–114. [Google Scholar]

- Harden-Moore T (2020). 2020 vision: The importance of focusing on accompliceship in the new decade. Diverse Issues in Higher Education. Retrieved from https://www.diverseeducation.com/opinion/article/15106233/2020-vision-the-importance-of-focusing-on-accompliceship-in-the-new-decade [Google Scholar]

- Haskins A & Lee H (2016). Reexamining race when studying the consequences of criminal justice contact for families. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 665(1): 224–230. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson TL, Shigeto A, Ponzetti JJ, Edwards AB, Stanley J, & Story C (2017). A cultural variant approach to community-based participatory research: New ideas for family professionals. Family Relations, 66, 629–643. doi: 10.1111/fare.12269 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Henrich J, Heine SJ, and Norenzayan A (2010). “The Weirdest People in the World?” Behavioral and Brain Sciences 33 (2–3): 61–83. 10.1017/S0140525X0999152X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James A, Coard SI, Fine M, & Rudy D (2018). The Central Roles of Race and Racism in Reframing Family Systems Theory: A Consideration of Choice and Time. Journal of Family Theory and Review, 10, 419–433. doi: 10.1111/jftr.12262 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen TM, & Sanner C (2021). A scoping review of research on well-being across diverse family structures: Rethinking approaches for understanding contemporary families. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 1–33. 10.1111/jftr.12437. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ladner JA (1973). The Death of White Sociology. Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Lee D, & McLanahan S (2015). Family Structure Transitions and Child Development: Instability, Selection, and Population Heterogeneity. American Sociological Review, 80(4), 738–763. doi: 10.1177/0003122415592129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H & Wildeman C (2021). Assessing mass incarceration’s effects on families. Science, 374, 277–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legewie J & Fagan J (2019). Aggressive policing and the educational performance of minority youth. American Sociological Review, 84(2), 220–247. [Google Scholar]

- Letiecq B (2019). Family privilege and supremacy in family science: Toward justice for all. Journal of Family Theory and Review, 11(3), 398–411. DOI: 10.1111/jftr.12338 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Letiecq B, Anderson EA, & Joseph A (2013). Social policies and families. In Peterson GW & Bush K (Eds.), Handbook of Marriage and the Family, 3rd ed. New York: Springer Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Letiecq B, Vesely C, & Goodman R (in press). Family-centered participatory action research: With, by, and for families. In Adamson K, Few-Demo A, Proulx C, and Roy K (Eds.), Sourcebook of Family Theories and Methodologies: A Dynamic Approach. NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Letiecq BL, Williams JM, Vesely CK, & Smith Lee JR (2021). Racialized housing segregation and the structural oppression of Black families: Understanding the mechanisms at play. NCFR Report. National Council on Family Relations: Minneapolis, MN. [Google Scholar]

- Kalil A, Ryan R, & Chor E (2014). Time investments in children across family structures. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 654(1): 150–168. [Google Scholar]