Abstract

Osteogenic differentiation is essential for bone development and metabolism, but the underlying gene regulatory networks have not been well investigated. We differentiated mesenchymal stem cells, derived from 20 human induced pluripotent stem cell lines, into preosteoblasts and osteoblasts, and performed systematic RNA-seq analyses of 60 samples for differential gene expression. We noted a highly significant correlation in expression patterns and genomic proximity among transcription factor (TF) and long noncoding RNA (lncRNA) genes. We identified TF-TF regulatory networks, regulatory roles of lncRNAs on their neighboring coding genes for TFs and splicing factors, and differential splicing of TF, lncRNA, and splicing factor genes. TF-TF regulatory and gene co-expression network analyses suggested an inhibitory role of TF KLF16 in osteogenic differentiation. We demonstrate that in vitro overexpression of human KLF16 inhibits osteogenic differentiation and mineralization, and in vivo Klf16+/− mice exhibit increased bone mineral density, trabecular number, and cortical bone area. Thus, our model system highlights the regulatory complexity of osteogenic differentiation and identifies novel osteogenic genes.

Keywords: bone, induced pluripotent stem cell, mesenchymal stem cell, osteoblast, RNA sequencing, differential gene expression, transcription factor, long noncoding RNA, splicing, single-cell RNA-seq, network analysis, systems biology

Introduction

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are multipotent cells that can differentiate into a variety of lineages, including osteoblasts (OBs), chondrocytes, and adipocytes (Pittenger et al., 1999). Osteoblast differentiation from MSCs plays a pivotal role in bone development, homeostasis, and fracture repair. Given their critical roles, exploring the molecular mechanisms underlying MSC differentiation into OBs is of significant clinical importance.

Osteogenic differentiation is highly regulated by multiple mechanisms, and previous research has highlighted the roles of various genes, including those coding for transcription factors (TFs), long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs), alternative spliceoforms, and signaling pathways such as TGF-β/BMP, Notch, Hedgehog, Wnt, Hippo, and estrogen receptor signaling (Thomas and Jaganathan, 2022). Out of over 1,600 identified TFs (Lambert et al., 2018), only a small subset has been linked to osteogenic differentiation (Chan et al., 2021; Thomas and Jaganathan, 2022; Rauch et al., 2019), underscoring the need to explore other TFs’ roles (Kang et al., 2019). Precise and robust transcriptional regulation is required during osteoblast differentiation, achieved by networks of transcriptional regulators. For example, RUNX2 is a master transcription factor in early osteoblast differentiation (Komori et al., 1997; Schroeder et al., 2005), but its expression does not increase in later stages. Concurrently, Notch signaling initially decreases but later represses RUNX2, boosting terminal differentiation and mineralization (Canalis et al., 2013; Ji et al., 2017; Shao et al., 2018). TFs ATF4, TEAD4, and KLF4 work alongside RUNX2 to regulate osteogenesis (Suo et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2004; Yu et al., 2021). However, the broader TF interplay in osteoblast differentiation remains largely uncharted, even with insights from ENCODE (Encyclopedia of DNA Elements) data that reveal the co-association of human TFs in a combinatorial and context-specific manner (Gerstein et al., 2012).

LncRNAs are vital in regulating cellular growth and differentiation (Guttman et al., 2011; Ransohoff et al., 2018), and nearly 30,000 human IncRNA genes have been annotated (Hon et al., 2017). Though our understanding of their role in osteogenesis is emerging, only about 60 lncRNAs are known to influence osteogenic differentiation, affecting TFs, pathway genes, or acting as molecular sponges for miRNAs (Ghafouri-Fard et al., 2021; Lanzillotti et al., 2021). For instance, lncRNA H19 promotes osteoblast differentiation via the TGF-β1/SMAD3/HDAC pathway by encoding miR-675 (Huang et al., 2015), while lncRNA MALAT1 enhances osteoblast differentiation through SMAD4 up-regulation by sequestering miR-204 (Xiao et al., 2017). Numerous studies have independently investigated both human coding and lncRNA gene expression profiles during osteogenic differentiation (Abd Rahman, 2021; Håkelien et al., 2014; Hong et al., 2020; Huang et al., 2017; Khodabandehloo et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020; Park et al., 2015; Qiu et al., 2017; Shaik et al., 2019; Skårn et al., 2014; Song et al., 2015; Sun et al., 2019; Twine et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2015; Xia et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2017; Zheng et al., 2018). However, many of these studies are limited by such factors as reliance on microarrays, small sample sizes, and brief osteogenic differentiation periods. In-depth exploration of lncRNA profiles and their association with adjacent protein-coding genes would therefore be advantageous.

Around 4,000 genes were identified to have alternative splicing (AS) during osteogenic differentiation using microarray technology (Shang et al., 2016), while almost all human genes are expected to exhibit AS, producing multiple transcript isoforms (Wang et al., 2008). AS serves as a widespread regulatory mechanism in gene expression and is implicated in various processes, including MSC osteogenic differentiation (Aprile et al., 2018; Makita et al., 2008). Abnormal splicing, as seen in the mutant COL1A1 gene, can lead to conditions such as osteogenesis imperfecta (Gug et al., 2020). Despite these findings, the role of splicing factors (SF) and differential splicing (DS) in osteogenic differentiation remains globally unexplored.

Unraveling the osteogenic differentiation of MSCs demands a systems biology approach, using a comprehensive transcriptome atlas and combined analysis of TFs, lncRNAs, and spliceoforms. Due to the invasiveness required to obtain human primary MSC and the suboptimal conditions for preserving available samples, large-scale human transcriptomics projects, such as GTEx, exclude data from bone and cartilage. Consequently, studies focusing on these tissues are often limited to disease contexts. Induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) derived systems, given their robust pluripotency and differentiation, offer an avenue for studying skeletal development. iPSC-derived sclerotome models have been used to recapitulate endochondral ossification (Nakajima, et al., 2018; Lamandé et al., 2023; Tani, et al., 2023). However, previous studies for osteoblast differentiation from iPSC-derived MSCs included only 1–2 MSC cell lines (Rauch et al., 2019; Matsuda, et al., 2020), limiting the power for comprehensive transcriptomic analyses. In this study, we used 20 human iPSC lines, each from a healthy individual, to investigate osteogenic differentiation of MSCs by RNA sequencing at three key stages: MSC, preosteoblast (preOB), and OB. Our findings highlight dynamic gene expression changes and the intricate interactions of lncRNAs and TFs. We spotlight the significance of alternative splicing during osteogenic differentiation. Finally, we identify the regulatory role of TF KLF16 as a potential inhibitor of osteogenic differentiation. This work provides insights into osteogenic differentiation and sheds light on novel therapeutic targets for bone diseases.

Results

Transcriptome profiles of human iPSC-derived MSCs and OBs are similar to that of primary MSCs and OBs.

We established a workflow to generate iPSCs from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) or skin fibroblasts from 20 healthy individuals (9 males and 11 females) and differentiated them into MSC, preOB, and OB stages (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Fig. 1a, 1b, and 1h; Supplementary Table 1). To abrogate the memory of their somatic cell origin and attenuate in vitro transcriptional and differentiation heterogeneity, the established iPSC lines were cultured for at least 16 passages and underwent quality control (Polo et al., 2010). The lines then underwent MSC differentiation for three weeks and purification by sorting for CD105+/CD45- markers (Giuliani et al., 2011; Kang et al., 2015). No significant differences were found in the percentage of this cell population, irrespective of erythroblast or fibroblast origins (Supplementary Fig. 1c and 1d). After two weeks of expansion, our iPSC-derived MSCs were confirmed to have mesenchymal characteristics by prominently expressing positive MSC surface markers (CD29, CD73, CD90, and CD105) and by barely detecting negative markers (CD31, CD34, and CD45) at both the protein level by flow cytometry (Supplementary Fig. 1e and 1f) and mRNA level by RNA-seq (Supplementary Fig. 1g). After osteogenic differentiation for 21 days, the OBs demonstrated alkaline phosphatase (ALPL) enzyme activity and mineralization with alizarin red and von Kossa staining, reflective of functional OBs (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1. Generation of healthy human iPSCs and osteogenic differentiation transcriptomic data.

a Flowchart of iPSC establishment, iPSC-derived MSC generation, MSC to OB differentiation (preOBs, preosteoblasts; OBs, osteoblasts), and RNA-seq data generation and analyses. b In vitro osteogenic differentiation of MSCs (Day 0), preOBs (Day 7), and OBs (Day 21) stained with alkaline phosphatase (ALP), alizarin red, and von Kossa. c Expression level of known osteogenic genes at the three osteogenic stages. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. * MSC vs preOB, # preOB vs OB, or + MSC vs OB, adjusted p value < 0.0001. d Principal component analysis (PCA) of RNA-seq data from our iPSC-derived MSCs and differentiated OBs as well as previously published human primary MSCs and OBs, iPSCs, and other tissues in GTEx.

A total of 60 RNA-seq libraries were generated from the 20 individuals at the three stages (Fig. 1a; Supplementary Table 1). We initially employed bulk RNA-seq rather than single-cell RNA-seq (scRNAseq) because the latter recovers only sparse transcriptional data from individual cells, thus limiting comprehensive expression analysis and the development of robust prediction models for regulatory and gene co-expression networks (Wang and Li, 2021). These data revealed increased expression of OB lineage markers (ALPL, COL1A1, RUNX2, SPARC, OMD, and OGN) with characteristic temporal expression patterns during osteogenic differentiation (Fig. 1c). We further compared our MSC and OB RNA-seq datasets with previously published human primary MSC and OB datasets, human iPSC datasets, and GTEx datasets for different tissues derived from the three germ layers (ectoderm, endoderm, and mesoderm) and germ cells (Al-Rekabi et al., 2016; Ardlie et al., 2015; Ma et al., 2019; Roforth et al., 2015; Rojas-Peña et al., 2014). By principal component analysis (PCA), our MSC and OB datasets clustered with those of published primary MSCs and OBs, respectively, and were discrete from iPSCs and other tissue datasets, further validating our MSC and OB cell lines (Fig. 1d).

Differential transcription profiles of human iPSC-derived MSCs, preOBs, and OBs.

During in vitro osteogenic differentiation, we detected the expression of 17,795 unique genes across all stages, of which 79% were protein-coding and 21% were noncoding (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Seventy percent or 9,724 of the protein-coding genes were differentially expressed (DE) between the osteogenic stages (MSC to preOB or preOB to OB) (fold change ⩾ 1.2 and adjusted p value ⩽ 0.05). Sixty percent (2,297) of the noncoding genes also were DE (Supplementary Fig. 2a), of which 2,249 (98% of DE noncoding) were lncRNA genes. By intersecting with the identified 1,600 TFs (Lambert et al., 2018), we found that nine percent (840 genes) of the DE coding genes (Supplementary Fig. 2b) and six percent (257 genes) of the non-DE coding genes coded for TFs (Supplementary Fig. 2a). And a chi-square test revealed a significant correlation between TFs and differentially expressed genes (DEGs) (X2 = 27.4, p < 0.0001), indicating TF genes were more likely than non-TF coding genes to be differentially expressed during osteogenic differentiation. There were 5,715 up-regulated genes and 4,409 down-regulated genes from the MSC to the preOB stage and 3,342 up-regulated genes and 2,835 down-regulated genes from the preOB to the OB stage, revealing that the majority of the DEGs were up-regulated during osteogenic differentiation (Supplementary Fig. 2c and 2d; Supplementary Table 2). Among the top statistically significant up- or down-regulated genes, known osteogenesis-associated genes, including a SMAD ubiquitination regulatory factor SMURF2 (Kushioka et al., 2020), natriuretic peptide precursor B NPPB (Aza-Carmona et al., 2014), hypoxia inducible factor 3 subunit alpha HIF3A (Zhu et al., 2014), a TF ZBTB16 (Onizuka et al., 2016), a Wnt signaling pathway family member WNT7B (Yu et al., 2020a), osteoinductive factor OGN, a SFRP family (modulators of Wnt signaling) member SFRP2 (Yang et al., 2020a), and a glycoprotein member of the glycosyl hydrolase 18 family CHI3L (Chen et al., 2017), were identified. There were also many genes with no defined function in bone, including those that play critical roles in RNA binding activity (EBNA1BP2), maintenance of protein homeostasis (PSMD2), arachidonic acid metabolism (PRXL2B), hemostasis and antimicrobial host defense (FGB), embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells (PCSK2), as well as cell proliferation, differentiation and migration (FGFBP1). A larger number of DEGs with larger changes in gene expression was identified from the MSC to the preOB stage than from the preOB to the OB stage, even though there was half the differentiation interval (one week) between the earlier two stages than between the latter two stages (two weeks) (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Fig. 2c, 2d, and 2e).

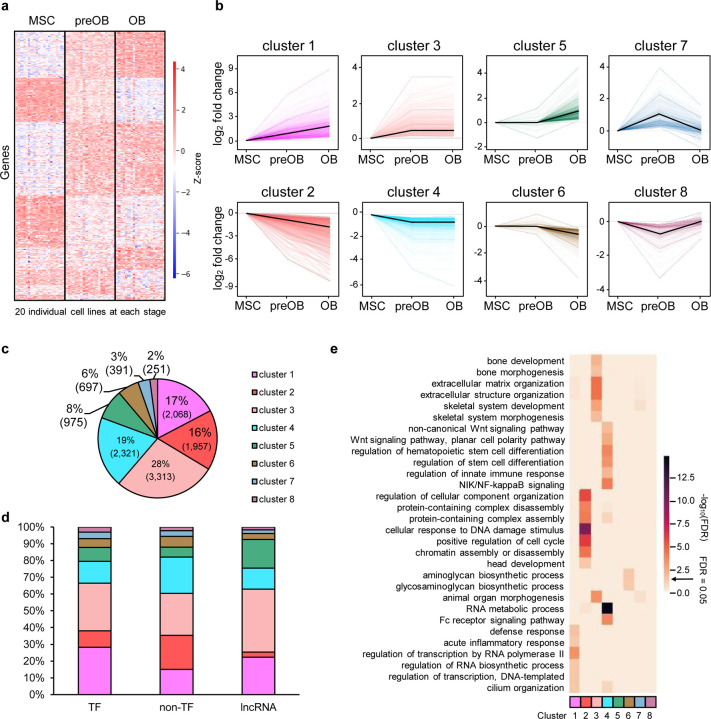

Fig. 2. Gene expression profile during osteogenic differentiation.

a Heatmap showing hierarchical clustering of 60 RNA-seq datasets from 20 iPSC-derived MSC, preOB, and OB lines (columns) and significant differentially expressed genes (DEGs) (rows), fold change ≥ 1.2 and adjusted p ≤ 0.05. Up-regulated and down-regulated gene expression is colored in red and blue, respectively. b Clustering of DEGs according to their expression profiles during differentiation, visualized with the TiCoNE Cytoscape app (Wiwie et al., 2019). In each plot, colored lines represent individual genes, and the black line represents cluster means. c Pie chart showing the number and percent of DEGs for each cluster. d Histogram chart showing the percentage distribution of transcription factor (TF), non-TF, and long noncoding (lnc) RNA DEGs in the eight clusters. Distribution correlation coefficient ρ = 0.9 between TF and lncRNA, 0.7 between TF and non-TF protein-coding genes, and 0.6 between lncRNA and non-TF coding genes. e Top significantly enriched gene ontology (GO) biological process (BP) terms of DEGs for each cluster.

Correlation of gene expression patterns of TFs and lncRNAs during human osteogenic differentiation.

Distinguishable gene expression profiles for each of the three osteogenic stages were displayed by a heatmap of Z-score normalized gene-expression values (Fig. 2a). We further characterized the DEGs by clustering them into eight possible patterns based on their expression up/down changes across the three osteogenic stages, MSC to preOB and preOB to OB (Fig. 2b; Supplementary Table 3). Cluster 1 and cluster 2 genes increased or decreased expression, respectively, throughout differentiation. The expression of genes for all other pairs of clusters also displayed opposite stage-specific changes. Genes in cluster 3 and cluster 4 increased or decreased expression, respectively, from the MSC to the preOB stage and remained relatively stable from the preOB to the OB stage. Genes in clusters 5 and 6 displayed no significant change In expression from the MSC to the preOB stage, but their expression increased or decreased, respectively, from the preOB to the OB stage. Genes in cluster 7 increased and in cluster 8 decreased in their expression from the MSC to the preOB stage, and in cluster 7 decreased and in cluster 8 increased from the preOB to the OB stage (Fig. 2b; Supplementary Table 3). When comparing the pairs of clusters, other than clusters 7 and 8, the number of genes with increased expression was consistently greater than that with decreased expression among stages (e.g., cluster 3 had 3,313 genes up-regulated while cluster 4 had 2,321 genes down-regulated from the MSC to the preOB stage) (Fig. 2b). 81% of all DEGs were in either pair of clusters 1 and 2 or 3 and 4, with almost half of all DEGs in clusters 3 and 4 (Fig. 2b and 2c). Also, each cluster contains various proportions of different types of genes, including TF, non-TF protein-coding, and lncRNA genes. Cluster 1 contained the highest percentage of TF genes (11%), cluster 2 contained the highest percentage of non-TF protein-coding genes (92%), and cluster 5 contained the highest percentage of lncRNA genes (40%) (Supplementary Fig. 2f). We determined the proportions of TF, non-TF protein-coding, and lncRNA genes in the eight clusters (Fig. 2d). We then calculated correlation coefficients to measure the similarity between the distribution of the proportion of a pair of the gene types. Interestingly, we found that TF and lncRNA genes were the most highly correlated with a correlation coefficient of 0.9 (p value = 0.003), compared to those of TF and non-TF protein-coding genes (ρ = 0.7, p value = 0.04), or lncRNA and non-TF coding genes (ρ = 0.6, p value = 0.11), suggesting that there is tighter regulatory control between TF and lncRNA genes, compared to the other pairs.

Gene ontology (GO) biological process (BP) overrepresentation tests revealed that each cluster was enriched for various functions that are distinct from other clusters (FDR ≤ 0.05, Fig. 2e; Supplementary Table 3). For example, cluster 3 was enriched for bone development, bone morphogenesis, ECM organization, skeletal system development, and skeletal system morphogenesis. Cluster 4 was enriched for Wnt signaling pathway planar cell polarity pathway, non-canonical Wnt signaling pathway, regulation of hematopoietic stem cell differentiation, regulation of innate immune response, regulation of stem cell differentiation, NIK/NF-kappaB signaling, RNA metabolic process, and Fc receptor signaling pathway. Cluster 5 had no significantly enriched BP terms, which may be explained by its high content of lncRNA genes (Supplementary Fig. 2f), of which biological functions are largely unknown and not annotated in the GO resource database (Carbon et al., 2019). Clusters 7 and 8 contained relatively small numbers of DEGs and showed no significantly overrepresented terms (Fig. 2c and 2e).

Transcription factor regulatory network during human osteogenic differentiation.

By PCA, we found that the expression profiles for all the DEGs segregated all of the samples by their differentiation stage, with MSCs being most distinct from preOBs and OBs, which is consistent with the larger number of DEGs present between the MSC and preOB stages than the later stages (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 2c and 2d). TFs were similar to other protein-coding genes in gene expression levels at each stage and their fold changes between stages (Supplementary Fig. 3a and 3b). Of note, when we used only the 840 differentially expressed TFs, their expression profiles also segregated the three osteogenic stages (Fig. 3b).

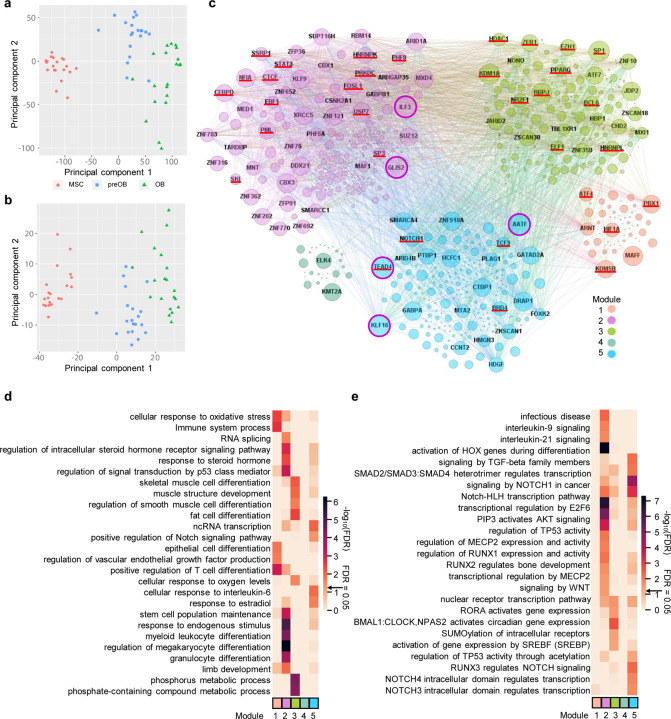

Fig. 3. Complex TF-TF regulatory network in osteogenic differentiation.

a Principal component analysis (PCA) of all 20 healthy cell lines at three stages of osteogenic differentiation using all differentially expressed genes (DEGs). b PCA using only differentially expressed TF genes. c Transcriptional regulator, mainly TF networks, during osteogenic differentiation. Each node represents a transcriptional regulator, with known bone formation associated regulators underlined in red. Two nodes are connected by a line where ReMap data suggest regulation and our RNA-seq data suggest the association between them. Nodes labeled with the gene name represent the top 100 strongest transcriptional regulators based on betweenness centrality. The size of the nodes reflects the regulation strength of the regulator, with the top 5 strongest circled in pink. d and e Top significantly enriched GO BP terms in d and Reactome pathways in e of transcriptional regulators in each network module.

TFs not only regulate the transcription of other protein-coding genes and noncoding RNA genes but also of TF genes themselves. We focused on the TF biological cooperativity with respect to TF-TF regulation because it has not been investigated globally in osteogenic differentiation. To predict the TF-TF regulatory network during osteogenic lineage differentiation, we constructed a network using the database ReMap, which integrated and analyzed 5,798 human ChIP-seq and ChIP-Exo datasets from public sources to establish a transcriptional regulatory repertoire to predict target genes (Chèneby et al., 2020), rather than more specific datasets as comprehensive MSC, preOB, or OB DNA-binding data are not available, in combination with our RNA-seq data. ReMap covers 1,135 transcriptional regulators, including mainly TFs and a few coactivators, corepressors, and chromatin-remodeling factors with a catalog of 165 million binding peaks. We filtered transcriptional regulators that did not show associations in ReMap, given that the transcription regulators are less likely to have real regulatory relationships in osteogenic differentiation if they do not display their associations in ReMap. To further assure the reliability and accuracy of the regulatory relationship in our osteogenic differentiation datasets, we then assessed regulations among them by computing correlation coefficients of gene expression, which resulted in 451 TFs preserved in the network. After the application of a partitioning algorithm, the generated network was organized into five interconnected modules (Bastian et al., 2009) (Fig. 3c; Supplementary Table 4). The network showed that TFs might regulate other TFs both internal and external to their respective modules, revealing a highly complex network of transcriptional regulators. We also identified the top 100 transcriptional regulators determined by their betweenness centrality, which coincided with their power to regulate others in the network (Fig. 3c; Supplementary Table 4) (Bastian et al., 2009). Among them, TF genes known to regulate osteogenic differentiation were present in different modules, such as ATF4 in module 1 (Yang et al., 2004), FOSL1 in module 2 (Krum et al., 2010), ZEB1 in module 3 (Fu et al., 2020), and TEAD4 in module 5 (Suo et al., 2020) (Supplementary Table 4). Of interest, TF KLF16 in module 5, which previously was not demonstrated to be involved in bone formation and bone development, was revealed to have an important role in the osteogenic network by its ranking as the fifth top regulator directly interacting with second top regulator TEAD4, and its high degree of association with 315 transcriptional regulators (Supplementary Table 4).

GO and Reactome pathway (RP) analyses revealed regulatory functions and pathways specific to each module (FDR ≤ 0.05; Fig. 3d and 3e; Supplementary Table 4). As examples for the GO BP terms, module 2 was enriched for RNA splicing. Module 3 was enriched for skeletal muscle cell differentiation and muscle structure development. These two terms were associated with six (EGR1, NR4A1, EGR2, SIX4, FOS, ATF3) and 15 (ZBTB18, MEF2A, EGR1, TCF7L2, EGR2, EPAS1, SRF, ZBTB42, ETV1, FOS, RBPJ, NR4A1, SIX4, ID3, ATF3) transcriptional regulator genes, respectively. Also, this module was enriched for the term fat cell differentiation and six associated TF genes (ATF2, NR4A1, TCF7L2, EGR2, PPARG, GLIS1). Module 5, containing KLF16, was enriched for terms ncRNA transcription and positive regulation of the Notch signaling pathway, which is essential in bone development and metabolism (Fig. 3d) (Liu et al., 2016).

In addition, each of the modules was enriched for GO cellular component (CC) terms of various complexes. Module 2 was enriched for the term ESC/E(Z) complex, a multimeric protein complex that can interact with several noncoding RNAs, a vital gene silencing complex regulating transcription, and an effector of response to ovarian steroids (Dubey et al., 2017) (Supplementary Fig. 4a). The modules were enriched for different GO molecular function (MF) terms of receptor binding of various hormones, including androgen, estrogen, glucocorticoid, and thyroid hormone receptor binding (Supplementary Fig. 4b), providing more evidence of the crosstalk between bone and gonads (Oury, 2012). With RP analysis, Module 2 was associated with activation of HOX genes during differentiation, consistent with its established important role in osteogenic differentiation of MSCs and skeletogenesis (Seifert, 2015). Module 5 was associated with signaling by TGF-beta family members, and the SMAD2/SMAD3:SMAD4 heterotrimer regulates transcription (Fig. 3e). These results revealed the complex and robust nature of TF regulatory networks during osteogenic differentiation.

Correlation in genomic proximity of lncRNA and TF genes during human osteogenic differentiation.

Given a large number of lncRNA DEGs during osteogenic differentiation (Supplementary Fig. 2a and 2b) and the similarity of their distribution to that of regulatory TF genes in the defined clusters of expression patterns per the coefficient calculation above (Fig. 2d), we further investigated the characteristics of lncRNAs during osteogenic differentiation. Our data showed that among all lncRNA genes, there were near equal amounts with one exon (24%) or two exons (22%), and the remaining 54% had more than two exons, of which each category contributed no more than 15% (Supplementary Fig. 3c). The proportion of lncRNA genes with the various numbers of exon differed from TFs and non-TFs (Supplementary Fig. 3c), as well as from previous studies that demonstrated that lncRNA genes have a tendency to have only two exons (42%) while each category of the remaining lncRNA genes with other than two exons contributed less than 27% on average over a wide range of human organs (GENCODE consortium, Derrien et al., 2012). The expression level of DE lncRNA genes was lower than TF and non-TF coding genes at each osteogenic stage (Supplementary Fig. 3a). However, the expression fold changes of the lncRNA genes among the osteogenic stages were larger than that of TF and non-TF coding genes (Supplementary Fig. 3b). We also performed PCA using the expression profiles of DE lncRNA genes from all 60 samples. PCA segregated them into three groups corresponding to their osteogenic stage, indicating the differentiation stages also can be defined by lncRNA expression profiles (Fig. 4a).

Fig. 4. lncRNA expression profiles discriminate osteogenic differentiation stages.

a PCA of differentially expressed lncRNA genes from all 20 healthy cell lines at three stages of osteogenic differentiation. b and c Bean plots showing the expression fold change (FC) of the protein-coding DEGs near up-regulated, down-regulated, and non-differentially expressed lncRNA genes from MSC to preOB stages (p < 0.0001, by Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test) in b and from preOB to OB stages (p < 0.0001) in c. The individual observations are shown as small horizontal lines in a one-dimensional scatterplot, and the average is indicated as the long horizontal line. The estimated density of the distributions is visible. d Density of the correlations of expression of DE lncRNAs and their pairwise DE neighboring protein-coding genes (pink) and that of DE lncRNAs and their randomly shuffled pairwise DE protein-coding genes outside the neighboring area (blue). e Venn diagram showing the numbers of protein-coding DEGs near up-regulated and down-regulated lncRNA genes specifically from the MSC to preOB stages as in b (blue) or from the preOB to OB stages as in c (orange) and their overlap. Top significantly enriched GO BP terms of the neighboring differentially expressed protein-coding genes are shown in the lower panel. f Expression of lncRNAs AC005261.1 and FTX during osteogenic differentiation. Data are shown as mean + SEM. * MSC vs. preOB, # preOB vs. OB, or + MSC vs. OB, adjusted p value < 0.001.

Unlike many coding genes that have well-known biological functions, most lncRNA genes have little functional annotation. Given that a major function of lncRNAs is to regulate their neighboring coding genes and that a classic way to assign cis biological functions to a set of lncRNA genes is to analyze their nearby genes’ functional annotations, we matched the lncRNAs to their nearby coding genes (Statello et al., 2021) (see Methods). We identified 441 neighboring protein-coding genes that were also differentially expressed (Supplementary Table 5). The expression fold changes for coding DEGs near either up-regulated or down-regulated lncRNA genes were larger than the expression fold changes for coding DEGs near non-differentially expressed lncRNA genes both from MSC to preOB and from preOB to OB stage (p < 0.0001 for both comparisons, by Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test), respectively (Fig. 4b and 4c). lncRNAs have been reported to display either positive (Kim et al., 2010; Ørom et al., 2010) or negative (Brockdorff et al., 1992; Nagano et al., 2008) regulation of their neighboring protein-coding genes. We found that both positive (25.3% vs. 5.1%, 0.8 > ρ ≥ 0.5, Chi-Square test, p < 0.0001) and negative (5.8% vs. 2.8%, −0.5 ≤ ρ > −0.8, Chi-Square test, p < 0.05) expression correlations, as well as very strong positive expression correlations (3.0% vs. 0.5%, ρ ≥ 0.8, Chi-Square test p < 0.01) of DE lncRNA genes with their pairwise neighboring coding DEGs, were significantly stronger than with randomly shuffled coding DEGs (Fig. 4d). This indicates a dual-directional regulation of lncRNA genes to their nearby coding genes in osteogenic differentiation. There was no significant difference in very strong negative expression correlations (ρ ≤ −0.8). Among the coding DEGs associated with DE lncRNA genes, we found 55 TF genes, including several members of the TEAD and ZNF families known to be involved in osteogenesis, 16 SF genes (e.g., SYF2 and SRSF1), and 59 DS genes (Supplementary Table 5). A chi-square test revealed a significant correlation of DE lncRNA genes with DE TF genes (X2 = 8.6, p < 0.01), which indicated that DE TF genes were more likely than DE non-TF coding genes to be neighbors of lncRNA genes, providing more evidence regarding a tight regulatory control between lncRNA and TF genes. We did not see a significant correlation of DE lncRNA genes with DE SF genes or with DE DS genes.

We further performed GO BP enrichment analysis on these coding DEGs near DE lncRNA genes to investigate functional annotations. It was not surprising to see these coding DEGs were enriched for regulation of transcription and gene expression because of the significant correlation of lncRNA and TF genes in both gene expression pattern and neighborship. Eight percent (36 genes) were identified to be involved in skeletal system development or regulation of ossification, 14% involved in the regulation of cell differentiation, and 25% involved in the regulation of cell communication (FDR ≤ 0.05, Fig. 4e, Supplementary Table 5). 12% of the lncRNA neighboring protein-coding genes differentially expressed from the preOB to OB stage were associated with regulation of phosphorus and phosphate metabolic processes, which are essential for bone mineral deposition and bone growth (Penido and Alon, 2012).

Among all genes, noncoding as well as coding, two lncRNA genes, AC005261.1 and FTX, were the first and fifth most significantly up-regulated genes from the preOB to OB stage (Supplementary Fig. 2c and 2d). The expression of AC005261.1 increased only at the later stage of OB differentiation (cluster 5), and FTX increased throughout differentiation (cluster 1) (Fig. 4f). AC005261.1 is antisense to a KRAB-containing zinc finger transcription gene ZNF304, which plays a fundamental role in T- cell differentiation (Sabater et al., 2002). FTX, an X-inactive-specific transcript regulator, previously was demonstrated to have a regulatory function in cell proliferation of multiple tumor types (Huang et al., 2020), and its down-regulation promotes the differentiation of osteoclasts in osteoporosis (Yu et al., 2020b). Taken together, these results demonstrate that dynamic expression of lncRNA genes is an integral component of the transcriptional profiles of osteogenic differentiation and may contribute to the regulation of osteogenic differentiation by regulating proximal coding genes.

Differential splicing of TF and lncRNA genes during human osteogenic differentiation.

To systematically investigate the role of RNA alternative splicing during osteogenic differentiation, we first identified 287 DE SFs by intersecting our DEGs with an SF list curated from published literature (Fig. 5a and 5b; Supplementary Table 6) (Piva, et al., 2012; Giulietti, et al., 2013; Sveen, et al., 2011; Seiler, et al., 2018; Hegele, et al., 2012; Koedoot, et al., 2019). Thirty-six percent of them showed stage-specific expression changes, with 86 DE SFs from MSC to preOB and 18 DE SFs from preOB to OB stage (Fig. 5b). The expression fold changes of the SF genes between the earlier two stages were greater than that between the latter two stages (Fig. 5b; Supplementary Table 6). To the best of our knowledge, only six SFs (U2AF1, SF3b4, HnRNPL, SRSF1, SRSF2, and DDX17) have been revealed to be associated with osteogenesis (He et al., 2022; Jia et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2021; Watanabe et al., 2007; Yi et al., 2019), and five of them except U2AF1 were found to be differentially expressed (top 62 up-regulated and top 12 down-regulated) during osteogenic differentiation in our datasets (Supplementary Table 6). U2AF1 was not a DEG, but U2AF1L4, predicted to be part of H2AF complex, was ranked as the top seventh down-regulated gene. The remaining DE SFs, including the top five up-regulated (CELF2, JUP, ALYREF, MELK, and SNRPB) and down-regulated (SEC31B, PCBP3, CLK4, LGALS3, and CLK1), have not been investigated in osteogenesis (Supplementary Table 6). We then examined differential splicing among stages using Leafcutter, which quantifies intron usage across samples by leveraging spliced reads that span an intron and calculates the percent spliced-in (PSI), which is the percentage of transcripts for a given gene in which the intron sequence is present (Li et al., 2018). Around 30% of the maximum changes of PSI for DS intron clusters of variably excised introns of a gene across osteogenic stages were greater than 10% (Fig. 5c). We identified 1,932 DS intron clusters for 1,750 genes from the MSC to preOB stage, and 254 clusters for 260 genes from the preOB to OB stage (Fig. 5d; Supplementary Table 6); the difference of the number of DS genes between these stages may be a reflection of the difference in the number and expression level changes of SFs (Fig. 5a and 5b). 31% and 25% of the DS genes contained at least one previously unannotated exon, from the MSC to the preOB stage and from the preOB to OB stage, respectively, indicating specific transcription profiling and the complexity and diversity of the human transcriptome of osteogenic differentiation (Supplementary Table 6).

Fig. 5. Differential splicing between osteogenic differentiation stages.

a Heatmap of the expression of 287 splicing factors (SFs) differentially expressed across the MSC, preOB, and OB stages. b Venn diagram showing the numbers of the differentially expressed SFs from the MSC to preOB stages (blue) and the preOB to OB stages (orange) and their overlap. Their expression fold changes for both up and down directions between stages are shown in the lower panel. Center lines show the medians; box limits indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles; whiskers extend to the minimum and maximum values; crosses represent sample means. c Proportion of the maximum percent spliced-in (PSI) changes for intron clusters with significant (FDR ⩽ 0.05) differential splicing (DS) between stages identified by LeafCutter. d Venn diagram showing the numbers of the differentially spliced genes from the MSC to preOB stages (blue) and the preOB to OB stages (yellow) and their overlap. Their top enriched GO terms and Reactome pathways (BP, biological process; MF, molecular function; CC, cellular component; RP, Reactome pathway) are shown in the lower panel. e Overview of a significant DS intron cluster in TF NFIX associated with increased expression of the intron at chr19:13025552–13073047 at the preOB stage compared to the MSC stage (CTF_NFI_2, CCAAT box-binding transcription factor_nuclear factor I_2 domain). (Left) Increased or decreased intron usage from the MSC to the preOB stages are indicated in red and turquoise, respectively. The FDR-corrected p value for the significant DS is indicated in blue above the intron cluster when it is significant. (Right) Details of the significant DS intron cluster indicate the PSI for each intron at the MSC stage (red) and the preOB stage (fuchsia) and the changes in PSI (ΔPSI) (blue) between stages. The affected protein domain is highlighted in grey above the intron cluster. f Similar to e, but for the lncRNA gene CYTOR. The significant p value for the DS is indicated above the intron cluster.

We then performed GO and RP enrichment analyses of the DS genes to explore their potential biological functions during osteogenic differentiation (FDR ≤ 0.05, Fig. 5d and Supplementary Table 6). Several hundred of the DS genes were significantly enriched for various metabolic processes, and 52 DS genes were associated with ECM organization. Various sets of the DS genes were associated with chromosome organization, histone modification, transcription factor binding and activity, transcription coactivator activity and coregulator activity, and post-translational protein modification, suggesting that DS events regulate gene expression at multiple levels, including modulating TFs and TF-TF association during osteogenic differentiation. 48 DS genes were significantly enriched for RNA splicing regulation, indicating modulation of the functions of SFs themselves by DS events (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Table 6).

A considerable number of differential splicing events are predicted to produce different protein isoforms, and more than 40% (MSC to preOB, 798 domains affected in a total of 1,929 DS genes; preOB to OB,110 domains affected in a total of 254 genes) of the events potentially modify domains of protein-coding genes (Supplementary Table 6). There were many DS genes encoding proteins with known roles in ECM organization, mineralization, and bone formation, such as VCAN (Nakamura et al., 2005), FN1 (Yang et al., 2020b), and MACF1 (Hu et al., 2021) (Supplementary Fig. 5a, 5b, and 5c). A notable example of a DS TF was NFIX (Fig. 5e). NFIX, encoding nuclear factor I transcription factor family member X, plays a pivotal role in bone mineralization (Driller et al., 2007). NFIX at the preOB stage compared to the MSC stage, showed increased expression of isoforms containing the intron at chr19:13025552–13073047, where the N-terminal DNA-binding domain is located (Fig. 5e). This domain contains four Cys residues highly conserved in all species, which are required for its DNA-binding activity (Novak et al., 1992). We found that some lncRNA genes also had differential splicing among stages. For example, cytoskeleton regulator RNA gene (CYTOR), which promotes cell proliferation, invasion, and migration in various types of cancer (Zhu et al., 2020), showed increased inclusion of the exon at chr2:87455645–87521207 (Fig. 5f). Altogether, these findings suggest that alternative splicing plays a prominent role in osteogenic differentiation.

Identification of key regulators in the co-expression network of human osteogenic differentiation.

We performed multiscale embedded gene co-expression network analysis (MEGENA) to identify gene co-expression structures (i.e., modules) as well as key network regulators (Holmes et al., 2020; Song and Zhang, 2015). MEGENA was conducted on the RNA-seq data from the three osteogenic differentiation stages and identified 168 co-expressed gene modules (FDR ⩽ 0.05, Fig. 6a; Supplementary Table 7). We then identified potential key network regulators (KNR) that were predicted to modulate a large number of DEGs in the network by key driver analysis (Zhang et al., 2013; Zhang and Zhu, 2013). Many modules enriched for DEGs and their associated KNR recapitulated known osteogenic factors. For example, module M188, comprised of 99 genes, was significantly enriched for the up-regulated DEGs (MSC to preOB, fold enrichment = 1.64, adjusted p value = 6.65E-3; preOB to OB, fold enrichment = 2.04, adjusted p value = 1.31E-3) (Supplementary Fig. 6a and Supplementary Table 7). This module contained ten genes previously implicated in bone development or remodeling (Supplementary Table 7). Three of them, including SF DDX17 and lncRNA MALAT1, were identified as KNRs by key driver analysis (Supplementary Fig. 6b) (He et al., 2022; Xiao et al., 2017). Another SF (RNPC3) and two lncRNAs (MIR99AHG and ZKSCAN2-DT) were identified as KNRs among 11 DE SFs and 10 DE lncRNAs in the module (Supplementary Fig. 6b). As TFs are known to be fundamental to the osteogenic process, we particularly were interested in finding TFs with key regulatory roles new to osteogenesis. We focused on modules that were significantly enriched for DEGs and contained DE TF genes identified as key drivers (Supplementary Table 7). We identified 80 such TF key drivers, of which 60 have unknown biological functions in osteogenesis (Supplementary Table 7). The top 3 up-regulated (ZBTB16, HIF3A, and NR2F1) (Manikandan et al., 2018; Onizuka et al., 2016; Zhu et al., 2014) and the top 2 down-regulated (TEAD4, HMGA1) (Suo et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2021) KNR TFs have established roles in osteogenesis. The third most down-regulated KNR TF is KLF16 of module M204, which previously had little known involvement in osteogenesis (Supplementary Table 7).

Fig. 6. Gene co-expression network analysis reveals KLF16 plays an important role in osteogenic differentiation.

a Sunburst plots represent the hierarchy structure of the MEGENA co-expression network constructed on gene expression during the osteogenic differentiation. The structure is shown as concentric rings where the center ring represents the parent modules, and outer rings represent smaller child modules. Subnetwork modules are colored according to the enrichment of differential gene expression between stages (FDR < 0.05; top, MSC to preOB; bottom, preOB to OB; blue, down-regulated; red, up-regulated; cyan, both up- and down-regulated). The subnetwork branch for module M204 is outlined and labeled. b Co-expression network module M204. Diamonds indicate key driver genes, and circles indicate non-key driver genes. Blue indicates DEGs from MSC to preOB stages, red indicates DEGs from preOB to OB stages, and cyan indicates shared DEGs for both comparisons. Differentially expressed lncRNA and SF genes are underlined in fuchsia and green, respectively. Genes known to be related to bone are in red.

To further evaluate the expression patterns of the top candidate genes that we had discovered through our MEGENA as well as our DEG and TF-TF network analyses at the cell type level, we employed our previously published single-cell RNA-seq data. This data from iPSC-induced MSC osteogenic differentiations in six healthy individuals, were originally used to compare the human and chimpanzee skeleton (Housman et al., 2022). In that study, gene expression had been assessed at two stages, MSCs (day 0) and osteogenic cells (day 21) – analogous to our bulk MSC (day 0) and OB (day 21) stages, respectively. Although the differentiation culture conditions differed from this study, we found similar differential expression patterns in a pseudobulk analysis of the scRNA-seq time points for the top-5 gene sets of up- and down-regulated KNR-TFs (Supplementary Table 7), TF regulators based on TF-TF regulatory networks (Supplementary Table 5), up- and 5 down-regulated SFs (Supplementary Table 6), as well as 6 well known osteogenic markers (Fig. 1c). KLF16 was significantly differentially expressed, with its expression decreasing from the MSC to the OB stage in both datasets (Fig. 7a, Supplementary Fig. 7, Supplementary Table 9), validating our observations. We further analyzed pseudobulk expression data derived from five different osteogenic cell types and found that most genes of interest showed similar levels of expression among these cell types with the most differences occurring in mature osteocytes, including a notable reduction of RUNX2 expression as expected (Supplementary Table 10) (Thomas and Jaganathan, 2022).

Fig. 7. Inhibitory role of Klf16 in osteogenic differentiation.

a The expression of Klf16 at three human osteogenic differentiation stages. Data are shown as mean + SEM. * MSC vs. preOB, # preOB vs. OB, or + MSC vs. OB, adjusted p value < 0.001. b Analysis of Klf16 expression by RT-qPCR in MC3T3-E1 cells transduced vectors containing either stuffer sequence or Klf16 cDNA. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM (n=3, unpaired t-test p < 0.01). c Osteogenic differentiation of MC3T3-E1 cells without or with overexpression of Klf16, stained for ALP at day seven and alizarin red and von Kossa at day 14 and 21. d Length, fat mass, and lean mass of wild type (WT) and Klf16+/− mice. e DEXA analysis of whole body (head excluded) bone mineral content (BMC), bone area (B-area), and bone mineral density (BMD) of WT and Klf16+/− mice. f and g Representative microCT images of distal femur trabecular bone in f (left, top view; right, side view) and cortical bone in g from WT and Klf16+/− mice. Scale bar: 1 mm. h and i Graphs show trabecular bone volume/tissue volume (BV/TV), trabecular thickness (Tb.Th), trabecular number (Tb.N), and trabecular separation (Tb.Sp) in h; cortical bone area (Ct.Ar), cortical periosteal perimeter (Ct.Pe.Pm), and cortical endosteal perimeter (Ct.En.Pm) in i. For d, e, h, and i, data are presented using BoxPlotR (Spitzer, et al., 2014) as the mean ± SEM (WT n = 6, Klf16+/− n = 6, 3 males and 3 females for each group, aged 17 weeks, paired t-test, * p < 0.05, ** p <0.01).

KLF16, a key regulator of module M204 involved in human osteogenic differentiation.

We further focused on KNR TF, KLF16, as it is a key regulator in module M204. Multiple lines of evidence point to a potentially critical role of M204 in osteogenic differentiation. M204, comprised of 85 genes, was significantly enriched for down-regulated DEGs (MSC to preOB, fold enrichment = 1.80, adjusted p value = 1.58E-2; preOB to OB, fold enrichment = 2.29, adjusted p value = 1.08E-3) (Fig. 6a). Additionally, more than 9% (8 genes) of the DEGs in M204 are related to bone development and metabolism (Supplementary Table 7). Three (PHLDA2, RHOC, PFN1) out of the eight genes were identified as KNRs (Fig. 6b). The expression of PHLDA2 is associated with skeletal growth and childhood bone mass (Lewis et al., 2012). Knockdown of RHOC dramatically inhibits osteogenesis (Zheng et al., 2019). PFN1, a member of the profilin family of small actin-binding proteins, is known to regulate bone formation. The loss of function of PFN1, causes the early onset of Paget’s disease of bone, a disease with impaired osteoclast and osteoblast differentiation (Scotto di Carlo et al., 2020). We also examined overlap of the genes in M204 with the genes from genome-wide association studies with significant signals for bone area (B-area), bone mineral density (BMD), and hip geometry (Hsu et al., 2019; Morris et al., 2019; Styrkarsdottir et al., 2019), and found five genes, CYFIP1, MMD, PELO, PRSS23, and SNX13. Thus, based on our accumulative analyses, we hypothesized that KLF16 plays an important role in osteogenic differentiation.

Regulatory role of Klf16 in murine osteogenic differentiation in vitro.

We explored the role of Klf16 in osteogenic differentiation and bone mineral density and architecture. We overexpressed Klf16 in the preosteoblast murine cell line MC3T3-E1 using lentivirus vector-mediated gene transfer (Fig. 7b). We then performed three independent osteogenic differentiation experiments, each with three technical replicates for each differentiation stage (day 7, 14, and 21). Consistent with its continuously decreased expression across osteogenic stages, overexpression of Klf16 in the preosteoblast murine cell line MC3T3-E1 dramatically suppressed osteogenic differentiation at the early stage (day 7) with reduced matrix maturation detected by ALP staining, and at later stages (day 14 and 21) with reduced mineralization detected by alizarin red and von Kossa staining, compared to the control cells (Fig. 7c). The inhibitory function of Klf16 in osteogenic differentiation in vitro was observed consistently for each of the experimental and technical replicates.

Klf16+/− mice show increased bone mineral density and abnormal trabecular and cortical bone.

We explored the role of Klf16 in bone formation in vivo by studying a Klf16 knock-out mouse, generated by deleting a 444 bp segment in exon 1 using CRISPR technology by the Knockout Mouse Phenotyping Program (KOMP). This mutation deleted the Kozak sequence and ATG start, leaving the final 16 bp of exon one and the splice donor site. We examined heterozygous rather than homozygous mutants because of difficulties in breeding for the latter. No significant difference in the overall length between adult Klf16+/− and wild type (WT) control mice of the same C57BL/6 background and matched by gender and age were initially found (Fig. 7d). However, adult Klf16+/− mice had significantly increased lean mass (total tissue mass – fat mass, including bone mineral content) (p < 0.05), and no significant change in fat mass relative to WT mice (Fig. 7d). Furthermore, there was a dramatic increase in whole body bone mineral content (BMC), bone area, and bone mineral density in Klf16+/− mice compared to WT control mice revealed by DEXA scanning (p <0.01) (Fig. 7e). Likewise, μCT scanning of trabecular bone from adult Klf16+/− mice showed significantly increased bone to tissue volume (BV/TV) (p < 0.05) and trabecular thickness (Tb.th) (p < 0.01). There were no significant differences in trabecular number (Tb.N) and trabecular separation (Tb.Sp), indicating the maintenance of distances between trabeculae in the mutant (Fig. 7f and 7h). In addition, adult Klf16+/− mice showed significantly increased cortical bone area (Ct.Ar) (p < 0.05), cortical periosteal perimeter (Ct.Pe.Pm) (p < 0.01), and cortical endosteal perimeter (Ct.En.Pm) (p <0.01) compared to WT control mice (Fig. 7g and 7i). These findings further validated our predicted TF and co-expression networks and established a regulatory role of TF Klf16 in bone. Studying the bone features in MSC-specific Klf16 conditional knockout mice could offer additional confirmation of its importance in the osteoblast lineage, as Klf16 might have functions in both osteoblasts and osteoclasts, yet such a animal model is not available to date.

Discussion

Understanding the cellular and molecular mechanisms that drive both physiological and pathological bone formation requires knowledge of global transcriptional changes during osteogenic differentiation. To shed light on this, we utilized iPSC-derived MSCs as our tool. By profiling RNA expression in 20 healthy human lines at three osteogenic stages, MSC, preOB and OB, we observed the transcriptome profiles of our iPSC-derived MSCs and OBs were consistent with those of their primary counterparts, which suggests the potential applicability of our model system for osteogenic differentiation studies. Our differential gene expression analyses provided insights into transcriptional variations for each osteogenic stage, marked by changes in expression levels of numerous coding and non-coding genes. Patterns of dynamic gene expression identified clusters of genes implicated in different biological functions during differentiation. Many genes known to be implicated in bone function, such as bone development, bone morphogenesis, and extracellular matrix organization, were found to be significantly up-regulated only from the MSC to the preOB stage (cluster 3).

Our systems biology approach revealed complex networks of TFs, lncRNAs, and differential splicing events underlying osteogenic differentiation. A particular observation was the high degree of correlation between the dynamic expression patterns of TFs and lncRNAs. TF networks in mammalian cells often arise from TFs modulating other TFs (Wilkinson et al., 2017). Our research unveiled a multifaceted osteogenic differentiation TF network, segmented into five interactive modules. These modules, consistent with previous findings on functional modularity (Dittrich et al., 2008), showcased specific biological functions. For instance, Module 3 underscores TFs associated with fat cell differentiation, suggesting a balance between osteogenesis and adipogenesis within bone structures. This resonates with recent studies emphasizing the role of stem cell TFs in osteogenesis, which also act as checks on adipogenesis (Rauch et al., 2019). Additionally, this module identifies TFs integral to muscle differentiation, hinting at overlapping regulatory mechanisms for both bone and muscle growth. This concept is further supported by recent discoveries linking mesenchymal progenitors in muscle to bone formation (Julien et al., 2021). Further analyses discerned connections between TFs, RNA splicing, and ncRNA transcription across modules. This connectivity endorses known interactions between signaling pathways like TGF-β/BMP and Wnt (Hernández-Vega et al., 2021; Thomas and Jaganathan, 2022). Overall, our findings reveal intricate TF networks, pathway interactions, and offer deeper insights into osteogenic differentiation.

Our results offer a pioneering atlas of the expression of lncRNAs across three osteogenic stages: MSC, preOB, and OB. We discerned 2,249 lncRNAs with notable expression changes, surpassing even those of TFs. Concurrently, we identified 441 differentially expressed adjacent protein-coding genes, illustrating the bi-directional influence of lncRNAs during differentiation. Numerous neighboring coding DEGs were associated with skeletal development and mineral deposition processes. Fifty-five TFs, including several TEAD and ZNF TF family members were within these genes, and the correlation in genomic proximity of DE lncRNA and DE TF genes was statistically significant. The TEAD family, vital in bone remodeling, operates via the Hippo pathway (Tang and Weiss, 2017; Zhao et al., 2018), while the ZNF family finely tunes osteogenic differentiation with both inhibition and promotion by different members (Quach et al., 2011; Stains and Civitelli, 2003; Twine et al., 2016). Moreover, 16 SFs emerged in these findings, reinforcing the significant role lncRNAs play in osteogenic differentiation through various regulatory pathways.

In our study, we systematically identified differentially expressed SFs and DS genes during osteogenic differentiation. We discovered extensive differentially spliced genes, including ECM, TF, lncRNA, and SF, highlighting alternative splicing’s pivotal role in osteogenic differentiation. Some DS genes, like NFIX, are linked to human diseases. Mutations in NFIX that affect splicing lead to Marshall-Smith syndrome, marked by rapid bone maturation and other skeletal abnormalities (Malan et al., 2010; Martinez et al., 2015). These observations underscore the importance of correct splicing in physiological osteogenesis and the potential implications in pathological conditions, including bone cancer (Liu and Rabadan, 2021).

Our study explored the osteogenic gene co-expression network, highlighting potential gene modules and driver genes, like TFs, lncRNAs and SFs, that play an important role in differentiation. In this study we experimentally validated the regulatory role of KLF16 of module M204 in osteogenic differentiation as a proof-of-concept that our dataset provides a resource for the discovery of novel mechanisms in osteogenic differentiation. Future studies will be required to explore the roles of specific lncRNA and alternative splicing genes identified in this study. Module M204 was enriched for DEGs, many of which are related to bone metabolism. Three of these hinted at being KNR genes. When we focused on the transcription factor KLF16, not previously associated with bone formation, we observed some implications for its involvement in osteogenic differentiation. Overexpression of Klf16 reduced matrix maturation during MC3T3-E1 differentiation. Conversely, Klf16-haploinsufficient mice showed altered bone characteristics, including increases in whole body BMD, femoral bone volume to total tissue volume, trabecular bone thickness, and cortical bone area, which suggests KLF16’s regulatory function in restraining bone formation.

Encoded as a C2H2-type zinc finger transcription factor, KLF16 has affinity for GC and GT boxes, displacing TFs SP1 and SP3 in neural settings (Wang et al., 2016). These TFs, when attached to certain promoters, play roles in osteogenic differentiation (Le Mée et al., 2005). Furthermore, KLF16 targets specific metabolic genes, including estrogen-related receptor beta (ESRRB) and PPARA (Daftary et al., 2012; Sun et al., 2020). Also, our TF regulatory network found that KLF16 is associated with Notch signaling and TGFβ/BMP-SMAD signaling pathways, and regulation of ncRNA transcription. This paints a broad canvas of potential regulatory mechanisms for KLF16 in bone dynamics. Furthermore, other members from the KLF family, especially KLF4 (module 1), KLF5 (module 5), and KLF15 (module 3) (Supplementary Table 4), significantly influence skeletal development (Li et al., 2021; Shinoda et al., 2008; Song et al., 2017; Yu et al., 2021; Zakeri et al., 2022). KLF5, co-existing with KLF16 in module 5, curtails osteogenesis by inhibiting β-catenin through DNMT3B-induced hypermethylation (Li et al., 2021). KLF4’s modulation of osteogenic differentiation hinges on the BMP4-dependent pathway, resulting in reduced osteoblast numbers in deficient mice (Yu et al., 2021). Meanwhile, KLF15 enhances chondrogenic differentiation via the TF SOX9 promoter (Song et al., 2017). The roles of KLF6 and KLF9 (modules 3 and 2) in bone metabolism remain less defined (Zakeri et al., 2022). Collectively, these findings underline the KLF family’s complex involvement in osteogenesis.

Interestingly, KLF16 was upregulated in the MSCs of five elderly patients (79–94 years old) suffering from osteoporosis compared to five age-matched controls in a previous study (Benisch et al., 2012). A following study identified KLF16 as one of the key TFs whose targets were enriched from the DEGs in the MSCs of the osteoporosis patients versus controls (Liu et al., 2019). The inhibitory role of KLF16 in osteoblast differentiation identified in our study supports the hypothesis that the overexpression of KLF16 might contribute to osteoporosis, and KLF16 could be a potential therapeutic target for osteoporosis.

Taken together, the differentiation from iPSC-derived MSC to OB presents a promising model to explore the gene expression and networks in osteogenic differentiation. Our study offers insights into the intricate, layered, and diverse landscape of osteogenic differentiation regulation, encompassing TFs, lncRNAs, differential splicing, and their reciprocal regulations. This information serves as a foundational resource for delving deeper into physiological osteogenesis processes and decoding the complexities of pathological bone formation. Furthermore, this experimental model might hold potential for therapeutic research, possibly aiding treatments for conditions like osteoporosis and osteomalacia.

Methods

Human subjects

The twenty human subjects included in this study were in good general health. The study protocols and informed consent were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Stanford University and the IRB of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Each subject gave written informed consent for study participation. Height and weight for each subject were measured while wearing light clothing and with no shoes. See Supplementary Table 1 for complete demographic metadata.

Animal care and use

The Klf16+/− mouse strain was generated on the C57BL/6NJ genetic background by the Knockout Mouse Phenotyping Program (KOMP) at The Jackson Laboratory using CRISPR technology as described in the above text. Mouse procedures were in compliance with animal welfare guidelines mandated by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and Institutional Biosafety Committee (IBC) at The Jackson Laboratory. Genotyping was performed by real-time PCR of DNA extracted from tail biopsies. A detailed protocol can be found on The Jackson Laboratory website.

Cell lines

MC3T3-E1 Subclone 4 line (ATCC, CRL-2593, sex undetermined) was purchased directly from the ATCC. Mouse Embryonic Feeders were purchased from GlobalStem (Cat# GSC-6001G). Human iPSC lines were generated in this study. The cells were maintained at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) and dermal fibroblast isolation

The twenty human subjects included in this study were in good general health. The study protocols and informed consent were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Stanford University and the IRB of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Each subject gave written informed consent for study participation. Height and weight for each subject were measured while wearing light clothing and with no shoes. See Supplementary Table 1 for complete demographic metadata. PBMCs were isolated as we previously described (Carcamo-Orive et al., 2017). Briefly, blood was drawn in tubes containing sodium citrate anticoagulant solution (BD Vacutainer CPT mononuclear cell preparation tube, 362760). PBMCs were separated by gradient centrifugation. The cells were then frozen in RPMI medium (MilliporeSigma, R7388) supplemented with either 12.5% human serum albumin and 10% DMSO (MilliporeSigma, D2438) or 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (MilliporeSigma, F4135) and 10% DMSO, and stored in liquid nitrogen for later use. The detailed protocol for dermal fibroblast isolation can be found in our previous publication (Schaniel et al., 2021). Briefly, a skin sample was taken from each of the clinically healthy subjects using a 3 mm sterile disposable biopsy punch (Integra Miltex, 98PUN3–11). Each sample was cut into smaller pieces and placed into gelatin-coated tissue culture dishes with DMEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 10567022) supplemented with antibiotics, 20% FBS, non-essential amino acids (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 11140050), 2mM L-glutamine (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 25030081), 2 mM sodium pyruvate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 11360070), and 100 μM 2-mercaptoethanol (MP Biomedicals, C194705) to establish fibroblast lines. Fibroblasts were harvested using TrypLE Express (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 12605010) and passaged at a 1 to 4 split ratio. Fibroblasts were cryopreserved in 40% DMEM, 50% FBS, and 10% DMSO.

iPSC generation

Erythroblast protocol

The detailed erythroblast reprogramming process can be found in our previous publication (Carcamo-Orive et al., 2017). Briefly, PBMCs were thawed, and the erythroblast population was expanded for 9–12 days until approximately 90% of cells expressed CD36 and CD71. These expanded erythroblasts were reprogrammed by transduction with Sendai viruses (SeV) expressing factors Oct3/4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc using the CytoTune™-iPS 2.0 Sendai Reprogramming kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, A16518) according to manufacturer’s protocol.

Fibroblast protocol

The detailed fibroblast reprogramming process can be found in our previous publication (Schaniel et al., 2021). Briefly, mycoplasma-free fibroblasts at passage number 3–5 were reprogrammed using the mRNA reprogramming Kit (Stemgent, 00–0071) in combination with the microRNA booster kit (Stemgent, 00–0073) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

iPSCs expansion and characterization

To establish iPSCs, the cells were cultured on Matrigel (BD Bioscience, 354230–10, or Corning, 254248) in feeder-free conditions and maintained in mTeSR1 (Stem Cell Technologies, 05850). The iPSCs were passaged every 5–7 days after clones were picked. To ensure the high quality of the iPSC lines used in this study, those lines generated with Sendai virus first underwent virus clearance by continuous passaging. To measure the loss of SeV in the iPSCs generated from erythroblasts with SeV, quantitative RT-PCR was performed according to the SeV reprogramming kit manufacture protocol. For quality control, G-banded karyotyping, ALP staining, iPSC pluripotency marker immunocytochemistry, and embryoid body formation analysis (Yaffe et al., 2016) were performed. Differentiating colonies were routinely eliminated from the cultures. All the lines included in the current study had normal karyotypes, exhibited human embryonic stem cell morphology, and expression of ALP and pluripotency markers NANOG, SOX2, OCT4, SSEA4, and TRA-1–60. Further, embryoid body (EB) formation and differentiation assays demonstrated their competence for differentiation into all three germ layers. We excluded samples where any of these characterizations were abnormal (Daley et al., 2009; Yaffe et al., 2016).

Mycoplasma quality control

Mycoplasma testing of the cells was performed intermittently during culture. Cultures were grown in the absence of antibiotics for at least three days before testing. The culture medium or the DNA harvested from the cultures were tested for mycoplasma contamination using a MycoAlert Mycoplasma Detection Kit (Lonza, LT07–418) or e-Myco PLUS PCR Detection Kit (BOCA scientific, 25237).

Alkaline Phosphatase Staining

A high level of ALP expression can characterize the undifferentiated state of iPSCs. ALP is also an osteogenic marker. ALP staining was performed on iPSCs and to monitor the osteogenic differentiation process. Cells cultured on plates were briefly washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), fixed in 4% PFA for 3 minutes at room temperature, and then stained with Alkaline phosphatase kit II (Stemgent, 00–0055) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

iPSC embryoid body analysis

iPSC embryoid body formation and characterization were performed as previously described with modifications (Lin and Chen, 2008). Briefly, iPSCs were cultured in mTeSR1 medium on Matrigel-coated plates, and the medium was changed daily. On the day of EB formation, when the cells grew to 60–80% confluence, cells were washed once with PBS and then incubated in Accutase for 8–10 minutes to dissociate colonies to single cells and resuspended with mTeSR1 containing 2uM Thiazovivin. To form self-aggregated EBs, single iPSCs were transferred into an ultra-low attachment plate (Corning, CLS3471) via 1:1 or 1:2 passage. EBs were aggregated from iPSCs for three days, then were transferred to 0.1% gelatin-coated 12 well plates and maintained in embryoid body medium (DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10% FBS, 2mM L-glutamine, 0.1 mM non-essential amino acids, and 0.1mM 2–mercaptoethanol) for another ten days for the spontaneous generation of three germ layers with medium changed every other day. Fluorescent immunostaining was performed to detect the expression of markers of the three germ layers.

Fluorescence immunocytochemistry

The cells cultured on plates were briefly washed with PBS, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS for 15 minutes, washed with PBS three times, and then permeabilized with 0.2% Triton in PBS for 15 mins. The cells were then washed with PBS three times prior to blocking with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (MilliporeSigma, A8412) in PBS for 1 hour at room temperature and incubating with primary antibody 1:100 to 1:900 dilutions in 0.1% BSA in PBS for overnight at 4°C. Washing three times was conducted with PBS followed by incubation with a corresponding secondary antibody in 1:500 dilution in 0.1% BSA for 1 hour at room temperature. After washing with PBS, 1:50,000 diluted Hoechst (Thermo Fisher Scientific, H1398) was added to stain nuclei for 5 minutes, followed by washing with PBS three times and imaging. The following primary antibodies were applied to detect the expression of iPSC markers: anti-TRA-1–60 (Invitrogen, 41–1000, 1/100), anti-SSEA4 (Invitrogen, 41–4000, 1/200), anti-NANOG (Abcam, ab109250, 1/100), anti-OCT-4 (Cell signaling technology, 2840S, 1/400), and anti-SOX2 (Abcam, ab97959, 1/900). To detect the expression of the markers of three germ layers, anti-AFP (Agilent, A0008, 1/100) for endoderm, anti-α-SMA (MilliporeSigma, A5228, 1/200) for mesoderm, and anti-TUBB3 (MilliporeSigma, T2200, 1/200) for ectoderm were used. All the Alexa-conjugated secondary antibodies used were from Invitrogen: anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 (A-11029), anti-rabbit Alexa 488 (A-21206), and anti-rabbit Alexa 594 (A-11037).

G-banding karyotyping

Karyotype analysis was performed on all iPSC lines by the Human Genetics Core facility at SEMA4. iPSCs were cultured on Matrigel-coated T25 flasks before karyotyping and reached approximately 50% confluence on the day of culture harvest for karyotyping. Twenty cells in metaphase were randomly chosen, and karyotypes were analyzed using the CytoVision software program (Version 3.92 Build 7, Applied Imaging).

Differentiation of iPSCs to MSCs

In vitro differentiation of iPSCs to MSCs was carried out with commercial cell culture media according to the manufacture protocols with modifications. Briefly, iPSC colonies were harvested with Accutase (Innovative Cell Technologies, AT-104) and seeded as single cells on a Matrigel-coated plate in mTeSR1 and supplemented with 2uM Thiazovivin. The next day, TeSR1 medium was replaced with STEMdiff mesoderm induction medium (MIM) (Stem Cell Technologies, 05221) when cells were at approximately 20 – 50% confluence. Cells were then fed daily and cultured in STEMdiff MIM for four days. On day 5, the culture medium was switched to MesenCult-ACF medium (Stem Cell Technologies, 05440/8) for the rest of the MSC induction duration. Cells were passaged as necessary using MesenCult-ACF Dissociation Kit (Stem Cell Technologies, 05426). Cells were subcultured onto Matrigel at the first passage to avoid loss of the differentiated cells before tolerating the switch to MesenCult-ACF attachment substrate (Stem Cell Technologies, 05448). For passage two or above, cells were subcultured on MesenCult-ACF attachment substrate. After three weeks of differentiation, the cells were sorted for the CD105 (BD Biosciences, 561443, 1/20) positive and CD45 (BD Biosciences, 555483, 1/5) negative MSC population (Giuliani et al., 2011; Kang et al., 2015) using BD FACSAria II in the Mount Sinai Flow Cytometry Core Facility, and then expanded in MSC medium consisting of low-glucose DMEM (Gibco, 10567022) containing 10% FBS (Sotiropoulou et al., 2006). After expansion, a few MSC lines were further examined by BD CantoII for expression of other MSC positive surface markers CD29 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 17–0299, 1/20), CD73 (BD Biosciences, 561254, 1/20), CD90 (BD Biosciences, 555595,1/ 20), absence of other negative surface markers CD31 (BD Biosciences, 561653, 1/20), CD34 (BD Biosciences, 560940, 1/5), and retention of marker CD105 positivity and CD45 negativity as well.

Fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) and analysis

Single cells were washed with FACS buffer (PBS supplemented with 1% FBS and 25mM HEPES (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 1688449)) twice, resuspended to a concentration of 1×107 cells/ml in ice-cold FACS buffer, and incubated with the above conjugated antibodies for 30 minutes at 4° in the dark. Stained cells were then washed with FACS buffer three times before FACS or flow cytometry analysis. Flow cytometry data were analyzed with BD FACSDiva software.

Differentiation of iPSC-derived MSCs to osteoblasts

iPSC-derived MSCs were plated in a 6-well plate at a density of 3×103 /cm2 in MSC medium. After three days, the culture medium was switched to osteogenic differentiation medium (α MEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific, A1049001) supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% non-essential amino acids, 0.1 uM dexamethasone (MilliporeSigma, D4902), 10 mM β-glycerophosphate (MilliporeSigma, G9422), and 200 uM ascorbic acid (MilliporeSigma, A4544)) (Barberi et al., 2005; Holmes et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2015) and maintained in this medium for 21 days. The culture medium was changed every 2–3 days. Cells were harvested for total RNA isolation and RNA sequencing at day 0, day 7, and day 21 of differentiation, as indicated in the main text. ALP staining, and alizarin red staining and von Kossa staining, were employed to examine bone ALP expression and mineralization, respectively.

Alizarin red staining and von Kossa staining

Mineralization of osteoblast extracellular matrix was assessed by both alizarin red staining and von Kossa staining. Cells were washed briefly with PBS, fixed with 4% PFA for 15 minutes, and washed with deionized distilled water three times. For alizarin red staining, fixed cells were incubated in alizarin red stain solution (MilliporeSigma, TMS-008-C) with gentle shaking for 30 minutes, followed by washing with water four times for 5 minutes each with gentle shaking to remove non-specific alizarin red staining. For von Kossa staining, fixed cells were incubated in 5% silver nitrate solution (American Master Tech Scientific, NC9239431) while exposed to UV light for 20 minutes. Unreacted silver was removed by incubating in 5% sodium thiosulfate (American Master Tech Scientific, NC9239431) for 5 minutes, followed by washing with water twice. Mineralized nodules were identified as red spots by alizarin red staining and dark brown to black spots by von Kossa staining.

RNA-seq library preparation and sequencing

For total RNA isolation, cells were washed with PBS and harvested for RNA extraction using miRNeasy mini kit (QIAGEN, 217004) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Illumina library preparation and sequencing were conducted by the Genetic Resources Core Facility, Johns Hopkins Institute of Genetic Medicine (Baltimore, MD). RNA concentration and quality were determined using NanoDrop Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, DE). RNA integrity (RNA Integrity Number, RIN) was verified using Agilent BioAnalyzer 2100 and the RNA Nano Kit prior to library creation. Illumina’s TruSeq Stranded Sample Prep kit was used to generate libraries. Specifically, ribosomal depleted RNA was converted to cDNA and size selected to 150 to 200 bp in length, then end-repaired and ligated with appropriate adaptors. Ligated fragments were subsequently size selected and underwent PCR amplification techniques to prepare the libraries with a median size of 150bp. Libraries were uniquely barcoded and pooled for sequencing. The BioAnalyzer was used for quality control of the libraries to ensure adequate concentration and appropriate fragment size. Sequencing was performed on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 instrument using standard protocols for paired-end 100bp sequencing. All the samples were processed in one batch.

RNA-seq pre-processing and gene differential expression analyses

Illumina HiSeq reads were processed through Illumina’s Real-Time Analysis (RTA) software generating base calls and corresponding base call quality scores. CIDRSeqSuite 7.1.0 was used to convert compressed bcl files into compressed fastq files. After adaptor removal with cutadapt (Martin, 2011) and base quality trimming to remove 3′ read sequences if more than 20 bases with Q ⩾ 20 were present, paired-end reads were mapped to the human GENCODE V29 reference genome using STAR (Dobin et al., 2013) and gene count summaries were generated using featureCounts (Liao et al., 2014). Raw fragment (i.e., paired-end read) counts were then combined into a numeric matrix, with genes in rows and experiments in columns, and used as input for differential gene expression analysis with the Bioconductor Limma package (Ritchie et al., 2015) after multiple filtering steps to remove low-expressed genes. First, gene counts were converted to FPKM (fragments per kb per million reads) using the RSEM package (Li and Dewey, 2011) with default settings in strand specific mode, and only genes with expression levels above 0.1 FPKM in at least 20% of samples were retained for further analysis. Additional filtering removed genes less than 200 nucleotides in length. Finally, normalization factors were computed on the filtered data matrix using the weighted trimmed mean of Mvalues (TMM) method, followed by voom (Law et al., 2014) mean-variance transformation in preparation for Limma linear modeling. The limma generalized linear model contained fixed effects for sex (male/female), and cell source (fibroblast/erythroblast) and a random effect term was included for each unique subject. Data were fitted to a design matrix containing all sample groups, and pairwise comparisons were performed between sample groups (i.e., MSC stage, preOB stage, and OB stage). eBayes adjusted p values were corrected for multiple testing using the Benjamin-Hochberg (BH) method and used to select genes with significant expression differences (adjusted p value ≤0.05).

Gene expression patterns

Significantly up- or down-regulated genes identified by the above DEG analyses were clustered into eight possible patterns based on their up/down expression changes between MSC to preOB and preOB to OB stages, including up-up, down-down, up-stable, down-stable, stable-up, stable-down, up-down, and down-up. Gene expression of the DEGs was normalized by Z-score transformation. Heatmap of Z-score normalized gene expression of the DEGs in the eight clusters was plotted using Seaborn in Python (Waskom et al., 2021). Dynamic gene expression change patterns were plotted with TiCoNE using the log2 fold change of gene expression from MSC to preOB and preOB to OB stages as input for each of the clusters.

Integration of RNA-Seq data of human primary MSCs and OBs, iPSCs, and tissues in GTEx