Abstract

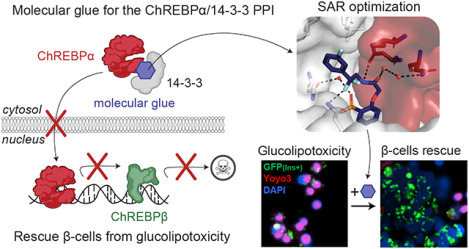

The Carbohydrate Response Element Binding Protein (ChREBP) is a glucose-responsive transcription factor (TF) with two major splice isoforms (α and β). In chronic hyperglycemia and glucolipotoxicity, ChREBPα-mediated ChREBPβ expression surges, leading to insulin-secreting β-cell dedifferentiation and death. 14-3-3 binding to ChREBPα results in cytoplasmic retention and suppression of transcriptional activity. Thus, small molecule-mediated stabilization of this protein-protein interaction (PPI) may be of therapeutic value. Here, we show that structure-based optimizations of a ‘molecular glue’ compound led to potent ChREBPα/14-3-3 PPI stabilizers with cellular activity. In primary human β-cells, the most active compound retained ChREBPα in the cytoplasm, and efficiently protected β-cells from glucolipotoxicity while maintaining β-cell identity. This study may thus not only provide the basis for the development of a unique class of compounds for the treatment of Type 2 Diabetes but also showcases an alternative ‘molecular glue’ approach for achieving small molecule control of notoriously difficult to target TFs.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) imposes an escalating burden on global health and economy. In 2021 537 million adults worldwide had diabetes, and this is expected to rise to 693 million by 20451 or even 1.31 billion by 20502, making it one of the leading causes of global morbidity3. Both major types of diabetes are characterized by insufficient functional β-cell mass to meet the increased demand for insulin. T2D develops due to decreased insulin response4, triggering a vicious cycle of increased insulin demand and decreased peripheral tissue response. While lifestyle adjustments can alleviate insulin resistance5, inadequate hyperglycemic control can lead to β-cell exhaustion, dedifferentiation, and eventual demise due to metabolic stress. This final stage is irreversible due to the restricted proliferative capacity of adult β-cells. Current T2D therapies mainly target insulin resistance and secretion, yet many T2D patients eventually become insulin dependent due to the loss of functional β-cells. Preventing the loss of functional β-cell mass remains one of the most important unmet needs in the armamentarium for the treatment of diabetes.

An emerging potential target to treat T2D is the glucose-responsive transcription factor (TF) Carbohydrate Response Element Binding Protein (ChREBP)6, 7. ChREBP is a key mediator in the response to glucose in pancreatic β-cells, controlling the expression of glycolytic and lipogenic genes8. Small molecule modulation of ChREBP function may thus represent a promising approach to combat T2D; however, many TFs such as ChREBP are known as notoriously difficult to target with small molecules due to their lack of suitable ligand binding sites9. However, several proteins interact with ChREBP to regulate its activation mechanism, including the 14-3-3 proteins10, 11. The protein-protein interaction (PPI) between ChREBP and 14-3-3 potentially offer long-sought entries to address ChREBP via molecular glues12, 13. The “hub” protein 14-3-3 is involved in numerous signaling pathways, as well as in the pathophysiologic state of diabetes14. Molecular scaffold proteins belonging to the 14-3-3 protein family are widely conserved among eukaryotes15, 16. In mammals, this family comprises seven isoforms, namely, β, γ, ζ, η, τ, σ, and ε17. In the context of pancreatic β-cells, 14-3-3 proteins are integral to the regulation of insulin secretion, cell proliferation, and survival14. They contribute to maintaining glucose homeostasis and influence key aspects of the cell cycle, impacting β-cell mass18, 19. The diverse functions of 14-3-3 proteins encompass their involvement in mitochondrial activity18, cell cycle progression14, contribution to apoptosis and cell survival pathways20. ChREBP interacts with 14-3-3, via a PKA responsive phosphorylation site S196 of ChREBP, and also via an alpha helix in its N-terminal domain (residues 117–137), which is one of the few known phosphorylation-independent 14-3-3 binding motifs10, 21, 22. The molecular basis of this PPI has been studied by X-ray crystallography, revealing the presence of a free sulfate or phosphate ion binding in the 14-3-3 phospho-accepting pocket that interacts with both proteins (Fig. S1a)23. Adenosine monophosphate (AMP) has also been reported to bind to this phospho-accepting pocket, weakly stabilizing the protein complex and enhancing the 14-3-3-mediated cytoplasmic sequestration of ChREBP (Fig. S1b)22. Next to inorganic phosphate and AMP, ketone bodies regulate ChREBP activity by increasing its binding to 14-3-310, 22. This may suggest that small-molecule stabilizers – molecular glues – of the ChREBP/14-3-3 PPI are potentially valuable tools to suppress glucolipotoxicity in T2D by inhibiting the transcriptional activity of ChREBP, thereby overcoming the current limitations of ‘direct’ targeting of TF functions.

MLXIPL, the gene that expresses ChREBP, produces two major splice isoforms: ChREBPα and ChREBPβ. The ChREBPα isoform is the full length-isoform, containing the low glucose inhibitor domain (LID, including the nuclear export signal (NES)) at its N-terminal region. One of the mechanisms that retains ChREBPα in the cytosol is via its interaction with 14-3-3 (Fig. 1a)10, 22. ChREBPβ lacks this N-terminal domain, resulting in a nuclear, constitutively active, hyper-potent TF24, 25. In healthy conditions, glucose flux leads to dissociation of CHREBPα from 14-3-3 resulting in its translocation to the nucleus and induction of ChREBPβ transcription, ultimately leading to glucose-stimulated β-cell proliferation to meet the demand for insulin (Fig. 1b). However, under prolonged hyperglycemic conditions, a robust positive feedback loop is triggered in which the newly produced ChREBPβ binds to its own promoter sites leading to even more ChREBPβ synthesis eventually resulting in glucolipotoxicity and β-cell apoptosis (Fig. 1c)10, 22, 26. These molecular mechanisms suggest that small molecule stabilization of the ChREBPα/14-3-3 PPI via a suitable molecular glue may prevent the nuclear import of ChREBPα under prolonged hyperglycemic conditions and thereby avert glucolipotoxicity (Fig. 1d). Indeed, our groups recently developed biochemically active stabilizers of the ChREBPα/14-3-3 PPI12; these compounds were only moderately active and more importantly lacked cellular activity, preventing cellular validation and downstream analyses of our hypothesis12. Here, we aimed to further improve these ChREBPα/14-3-3 PPI small-molecule stabilizers by using structure-activity relationship (SAR) analysis. This resulted in small-molecule stabilizers with a cooperativity factor (α) up to 220 for the ChREBPα/14-3-3 PPI. The introduction of a geminal-difluoro group into the pharmacophore not only significantly enhanced their stabilization efficiency, most probably by slight bending of the pharmacophore arrangement, but was also crucial for obtaining cellular permeation and activity. X-ray crystallography confirmed engagement of the molecular glues at the composite interface formed by the 14-3-3 binding peptide motif of ChREBPα and 14-3-3. Immunofluorescence showed retention of ChREBPα, by 14-3-3, in the cytoplasm of primary human β-cells upon addition of the stabilizers. Concomitantly, the transcriptional activity of ChREBPα was suppressed, hence preventing the upregulation of ChREBPβ in response to glucose and glucolipotoxicity. By exploiting this mechanism of action, β-cells were rescued from glucolipotoxicity, both in terms of viability and in terms of β-cell identity, including insulin production, by keeping ChREBP transcriptionally inactive at high glucose levels. This study provides the foundation for a potential new class of compounds for regulating ChREBP activity in T2D12, 22.

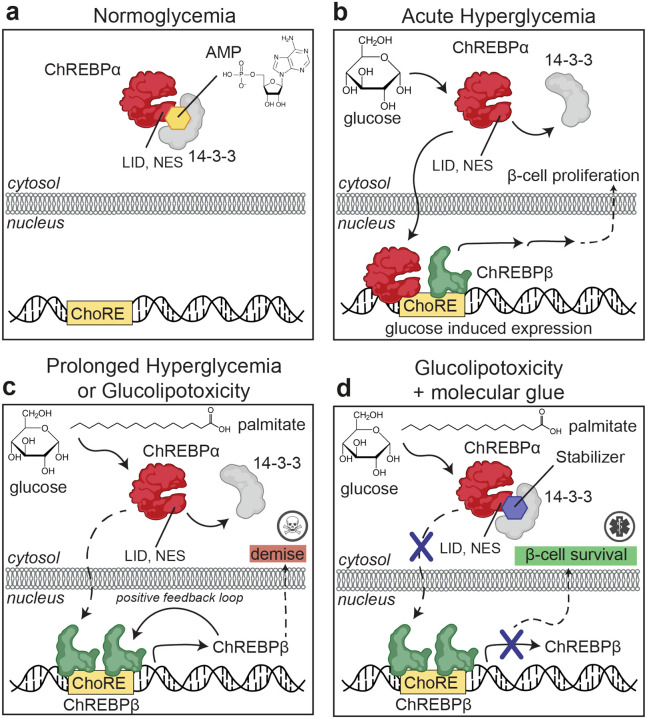

Fig. 1: Protein-Protein Interaction between 14-3-3 and ChREBPα regulates β-cell fate.

a. Under normoglycemic conditions, ChREBPα remains mostly cytoplasmic by binding to 14-3-3. ChREBPα is one of very few phosphorylation-independent 14-3-3 partner proteins and binds via a pocket containing a phosphate or sulfate ion, ketone, or AMP. b. In acute hyperglycemia, ChREBPα dissociates from 14-3-3 and transiently translocates into the nucleus where it binds multiple carbohydrate response elements (ChoREs) and promotes adaptive β-cell expansion. c. In prolonged hyperglycemia or hyperglycemia combined with hyperlipidemia (glucolipotoxicity), ChREBPα initiates and maintains a feed-forward surge in ChREBPβ expression, leading to β-cell demise. d. A novel class of molecular glue drugs specifically stabilize ChREBPα/14-3-3 interaction, prevent surge of ChREBPβ expression in glucolipotoxicity, and protect β-cell identity and survival.

Results

Differential stability and regulatory roles of ChREBP isoforms under high glucose

24, 25ChREBPβ is a constitutively active transcription factor that promotes its own production by binding to its own promoter24, 25. This raises questions of how ChREBPβ production gets turned off and what is its relationship to ChREBPα once it begins the positive-feedback mechanism. To address this, we analyzed the two isoforms’ half-lives. ChREBPβ, under high glucose concentrations, exhibits substantial instability, with a half-life as short as 12 minutes. In contrast, ChREBPα displays increased stability, with its half-life extending beyond 30 minutes (Fig. S2). These findings suggest that without continuous priming by ChREBPα activity, ChREBPβ production would be self-limiting, and provides a mechanistic explanation of how the positive-feedback production of ChREBPβ can be turned off when glucose levels decrease, or when ChREBPα is prevented from entering the nucleus when glucose levels are high.

Focused library based on 1 established a crucial SAR

To investigate the hypothesis that cytosolic sequestration of ChREBPα via molecular glue stabilization of the ChREBPα/14-3-3 PPI inhibits downstream glucotoxicity and β-cell apoptosis it was critical that our previously discovered stabilizer 1 (Fig. 2a) was first optimized to improve activity, but more importantly cellular efficacy. Stabilizer 1 was previously found to bind to the ChREBPα-peptide/14-3-3β interface (Fig. S3a–c)12. A challenge to optimization of 1 was the poor resolution of the ligand’s electron density in the X-ray co-crystal structure, particularly around the phenyl ring and linker of 1. This poor electron density limited structure-guided optimization and indicated sub-optimal PPI stabilization (Fig. S3d). To address this technical challenge our efforts were directed towards the development of an alternative crystallization approach. Gratifyingly, this novel co-soak crystallization approach resulted in a new co-crystal structure with an improved resolution of 1.6 Å. The improved resolution enabled a more reliable model building, including the atomic fitting of the phenyl ring and ethylamine linker of 1. (Fig. 2a, S3e). In addition to the phosphonate of 1 interacting with the phosphate-accepting pocket of 14-3-3 (R56, R129, Y130), and R128 of ChREBPα (Fig. 2b), it was now observed that both the phenyl and phenyl phosphonate rings of 1 make hydrophobic contacts with side chains of both 14-3-3 and ChREBPα. Further, an intramolecular hydrogen bond between the amide moiety and the phosphonate group of 1 was resolved. Finally, the improved resolution of this novel crystal structure enabled detection of a water-mediated hydrogen bond between the carbonyl amide of 1 and the main chain amide of I120 of ChREBPα (Fig. 2b). Subsequent Fluorescence Anisotropy (FA) measurements revealed that compound 1 stabilized the ChREBPα/14-3-3 complex with a cooperativity factor (α) of 35 (Fig. 2c). The cooperativity factor (α) and the intrinsic compound affinity to 14-3-3 (KDII) were determined by fitting, using a thermodynamic equilibrium model, which allows for an objective comparison of different stabilizers (Fig. S4, S5).32

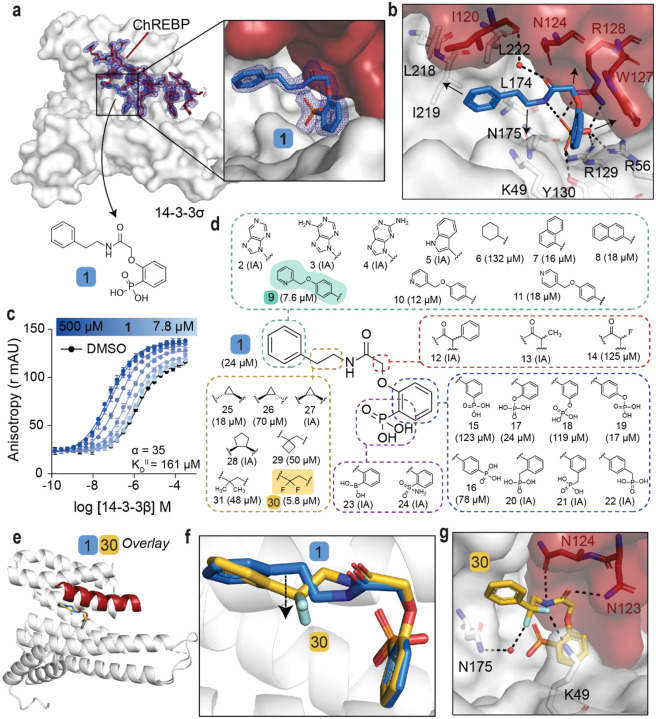

Fig. 2: SAR around analog 1 results in improved stabilizer 30.

a. Crystal structure of compound 1 (blue sticks) in complex with 14-3-3σ (white surface) and ChREBPα (red sticks and surface). Final 2Fo-Fc electron density contoured at 1.0σ. b. Interactions of 1 (blue sticks) with 14-3-3σ (white) and ChREBPα (red) residues (relevant side chains are displayed in stick representation, polar contacts are shown as black dashed lines). c. FA 2D protein titration of 14-3-3β in FITC-labeled ChREBPα peptide (10 nM) and varied but fixed concentrations of 1 (0–500 μM), including the cooperativity factor (α, determined, by fitting, using a thermodynamic equilibrium model32) and intrinsic affinity of 1 to 14-3-3 (KDII). d. Structure and activity analogs of 1. The two best compounds are marked in cyan and yellow. EC50 in parenthesis with mean ± SD, n = 2. For FA titration graphs see Fig. S4, S5. e, f. Crystallographic overlay of 1 (blue sticks) with 30 (yellow sticks) in complex of 14-3-3σ (white cartoon) and ChREBPα (red cartoon). g. Interactions of 30 (yellow) with 14-3-3 σ (white) and ChREBPα (red) (relevant side chains are displayed in stick representation, polar contacts are shown as black dashed lines).

With structural characterization of the ternary ChREBPα/14-3-3/1 complex in hand, attention was shifted to the optimization of compound activity. To gain a greater SAR understanding, a focused library was synthesized aiming to improve the stabilization efficiency and selectivity for this class of molecular glues, in which compounds were compared based on their EC50 value derived from FA-based compound titrations (Fig. 2d, S6, S7, S8, Table S1)27–29. To mimic the structure of the natural stabilizer AMP, the phenyl substituent of 1 was replaced by a purine (2, 3, 4). However, these modifications were not tolerated. Similarly, no stabilization was observed upon replacement of the phenyl moiety with either an indole (5), or a cyclohexane moiety (6), while naphthalene groups (7, 8) led to slightly more active compounds. Extension of the phenyl group with a methylpyridine functional group (9, 10, 11) increased the stabilization efficiency, with the N-2 position (9, EC50 = 7.6 ± 0.5 μM) eliciting the greatest response. Substitutions at the central acetamide were not tolerated (12, 13, 14). Furthermore, systematic shifting of the phosphonate group along the phenyl phosphonate ring showed that the ortho position is most favorable (1, 15, 16). Interestingly, replacement of the phosphonate with a phosphate group was tolerated (17, 18, 19) and the para positioned analog led to improved compound activity (EC50 = 17.4 ± 3.2 μM). Conversion of the phenyl phosphonate into a benzyl phosphonate was however not tolerated (20, 21, 22). Phosphonate mimics, e.g. a boronic acid (23) or a sulfonamide (24) group were also inactive compounds. Lastly, we focused on modifications of the alkyl fragment of the phenyl ethyl amine moiety. Investigation of the SAR around the ethylene linker showed that replacement of the ethylene linker with a constrained (1R, 2S) cyclopropyl ring (25, EC50 = 17.6 ± 1.7 μM) elicited similar activity to 1, while stereoisomers 26 (1S, 2R) and 27 (1R, 2R) were not tolerated. Furthermore, ring expansion to the cyclopentyl ring (28, 1R, 2R) was inactive and installation of a cyclobutyl (29) or geminal-dimethyl groups (31) resulted in diminished activity relative to 1. Interestingly, the introduction of a geminal-difluoro group however significantly enhanced (six-fold relative to 1) the stabilization of the ChREBPα/14-3-3 PPI, resulting in the best stabilization observed so far (30, EC50 = 5.8 ± 0.4 μM). Unfortunately, this analog was not amendable for phosphonate replacement with a sulfonamide or boronic acid, since this resulted in inactivity (58, 68, Table S2). Merging the two best stabilizers (9 and 30) resulted in analog 73 with a similar EC50 value compared to each individual substitution (73, EC50 = 11.0 ± 1.5 μM, Table S3). Co-crystallization of ChREBPα and 14-3-3 was successful for 30, showing a clear density of both the ChREBPα peptide and 30 (Fig. S9a). Overlaying the crystal structure of 30 with 1 revealed a high conformational similarity of 14-3-3σ and the ChREBPα peptide, with a comparable positioning of the phosphonate of 30 in the ChREBPα/14-3-3 phospho-accepting pocket (Fig. 2e, 2f). The geminal-difluoro group of 30 was, however, directed downwards into the 14-3-3 binding groove, causing an alternative bend of the phenyl ethyl amine moiety (Fig. 2f). Both fluorine atoms form interactions with 14-3-3σ; one directly contacts K49 and the other engages in a water-mediated polar interaction with N175 (Fig. 2g), thereby recapitulating other literature reports showing that fluorinated small molecules can form potent hydrogen bonds27–29. Additionally, due to the alternative bend of the linker, the amide of 30 was now positioned to interact with N123 and N124 of ChREBPα (Fig. 2g). These additional contacts of the molecular glue with both 14-3-3 and ChREBPα explain the increase in ternary complex formation by the introduction of the geminal-difluoro group.

Fluorination of compounds improves stabilization potency

Encouraged by the enhanced stabilizing activity of the fluorinated analog 30, a focused library of fluorinated compounds was next synthesized and compared to their non-fluorinated analogs (Fig. 3a, Table S3). Fluorination of analogs increased their stabilization potency consistently across all library members. Even the previously inactive p-Cl (32) and p-Br (33) substituted compounds now elicited a high activity when combined with the geminal-difluoro group substitution (40: EC50 = 6.6 ± 0.9 μM, 41: EC50 = 4.1 ± 0.4 μM, respectively). The fluorine functionality has a common place in medicinal chemistry as reflected by 20–25% of drugs in the pharmaceutical pipeline containing at least one fluorine atom30, 31. Introduction of a fluoro group at the meta position of the phenyl ring even further improved compound activity (43: EC50 = 3.8 ± 0.2 μM). Additional to single fluoro-substitutions at the phenyl ring of 30, double fluoro-substituted analogs were synthesized (panel IV in Fig. 3a). A 2,4-difluoro substitution resulted in the most potent stabilizer observed so far (53, EC50 = 3.1 ± 0.6 μM).

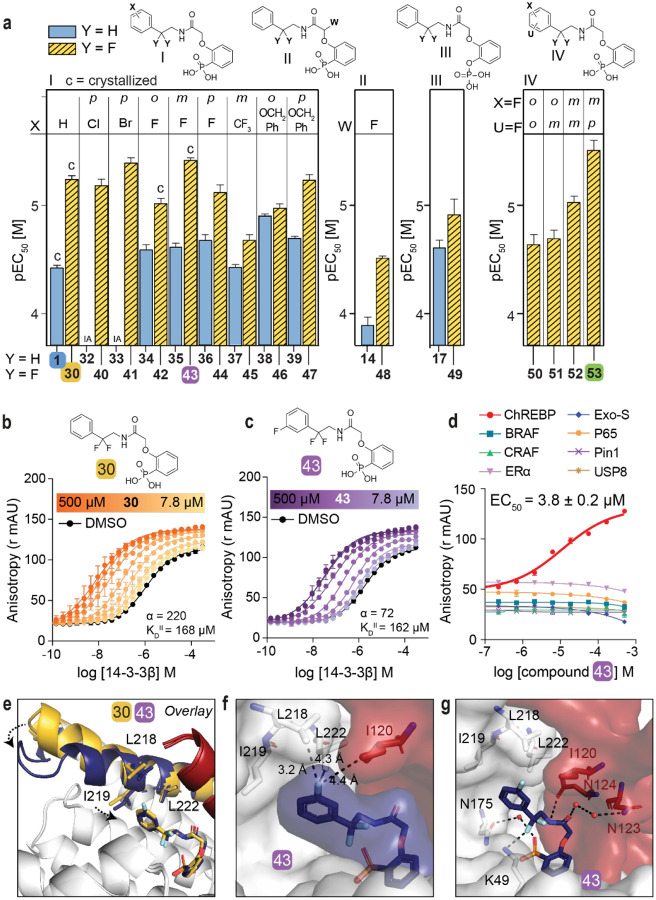

Fig. 3: Fluorination of compounds enhances stabilizing potency.

a. Structures and bar graphs of pEC50 values derived from FA compound titrations, for Y=H (blue bars) and Y=F (yellow bars). (For graphs see Fig. S4, S5, for EC50 values see Table S3) (mean ± SD, n=2). b, c. Titration of 14-3-3β to FITC-labeled ChREBPα peptide (10 nM) against varying fixed concentrations of 30 or 43 (0–500 μM) (mean ± SD, n = 2), including the cooperativity factor (α, determined, by fitting, using a thermodynamic equilibrium model32) and intrinsic affinity of the stabilizers to 14-3-3 (KDII). d. Selectivity studies by titrating 43 to 14-3-3β and eight different 14-3-3 interaction FITC-labeled peptides (all 10 nM) (mean ± SD, n = 2). e. Crystallographic overlay 30 (yellow) and 43 (purple) in complex with 14-3-3σ (white cartoon) and ChREBPα (red cartoon). Helix 9 of 14-3-3σ is colored in the same color as the corresponding compound, showing a helical ‘clamping’ effect when 43 (purple) is present. f. Surface representation of 43 (purple) in complex with 14-3-3σ (white) and ChREBPα (red), showing the distances (black dashes) of the 43 m-F substitution to the residues (sticks) of 14-3-3σ and ChREBPα. g. Interactions of 43 (purple) with 14-3-3σ (white) and ChREBPα (red) (relevant side chains are displayed in stick representation, polar contacts are shown as black dashed lines).

Two-dimensional FA titrations were performed to investigate the cooperativity in ChREBPα/14-3-3/stabilizer complex formation. 14-3-3β was titrated to FITC-labeled ChREBPα peptide (10 nM) in the presence of different, but constant, concentrations of 30, 43 or 53 (0–500 μM) (Fig. 3b, 3c, S10a). The change in apparent KD of the ChREBPα/14-3-3 complex, over different concentrations of stabilizer (Fig. S10b), showed that all three fluorinated compounds (30, 43 and 53) elicit a similar stabilizing profile, with a 2.4- to 6-fold increase in stabilization compared to the non-fluorinated parent analog 1. Fitting the two-dimensional data using the thermodynamic equilibrium model32 showed increased cooperativity for all three fluorinated compounds (α = 220 (30), 72 (43), 126 (53)) compared to their defluorinated parent compound 1 (α = 35), while their intrinsic affinity for 14-3-3 was barely affected (KDII = 168 μM, 162 μM, 110 μM for 30, 43, 53 and 161 μM for 1) (Fig. 3b, 3c, S5, S10a). This indicates that the compound optimization has mainly improved the interaction with ChREBPα and not the binding affinity to 14-3-3. Of note, the mean squared error landscape of the two fitted parameters showed for some stabilizers that the α and KDII parameters are interconnected, meaning that a weaker intrinsic affinity, KDII, correlates to an increased cooperativity factor, α. (Fig. S5).

Phosphate- and phosphonate-based compounds may also act as inhibitors of other 14-3-3-client protein complexes, often acting as low micromolar (IC50 ~ 1–20 μM) inhibitors33, 34. To test the specificity of the ChREBPα/14-3-3 PPI stabilizers, we selected an array of eight representative 14-3-3 client-derived peptide motifs with differentiating binding sequences and included internal binding motifs BRAF35, CRAF36, p6537, USP838, 39, one C-terminal binding motif ERα40, one special binding mode Pin141 and another reported non-phosphorylated motif ExoS21. Strikingly, all three compounds (30, 43, 53) displayed a high selectivity for stabilizing ChREBPα, without affecting any other client peptide up to 100 μM (Fig. 3d, S10c). Furthermore, titration of all seven 14-3-3 isoforms to ChREBPα in the presence of 43 showed PPI stabilization among all isoforms (Fig. S11). The ChREBPα stabilization selectivity of 43 was also preserved among different 14-3-3 isoforms (Fig. S12). These data demonstrate the highly selective nature of the molecular glue activity of these compounds by addressing a unique pocket only present in the ChREBPα/14-3-3 complex and via a stabilization mechanism, involving a large cooperativity effect.

Crystallization of the new fluorinated compounds with the ChREBPα/14-3-3σ complex was also successful for 42 and 43, resulting in a clear density for the entire molecule (Fig. S9b, c). A crystallographic overlay with 30 revealed an additional conformational ‘clamping’ effect of helix-9 of 14-3-3σ in the presence of 43 (Fig. 3e), causing the hydrophobic residues of 14-3-3 (I219, L218) to be closer to the phenyl ring of 43. This clamping effect of helix-9 is in line with previous observations for molecular glues with high cooperativity factors, for other 14-3-3 PPIs42. A more detailed analysis showed that the meta-fluoro group of 43 is positioned at the rim of the hydrophobic interface of 14-3-3 and ChREBPα (Fig. 3f). The rest of stabilizer 43 has similar interactions with both ChREBPα and 14-3-3 as 30 (Fig. 3g, S13). An ortho-fluoro substitution at the phenyl ring was less favorable (42, EC50 = 9.6 ± 1.1 μM) although it did result in a similar ‘clamping’ effect of helix-9 of 14-3-3 (Fig. S14). This ortho substituted fluoro was not positioned at the rim of the ChREBPα/14-3-3 interaction interface, instead it made a polar interaction with N175 of 14-3-3 (Fig. S14). While no crystal structure could be solved for the double fluoro-substituted analog 53, the structure of 43 shows room for a fluoro-substitution at the para position of its phenyl ring, explaining the high potency of 53 (Fig. 3g). Likely, the electron withdrawing effects of the fluorine substitutions are enhancing hydrophobic contacts with the hydrophobic amino acids at the roof of the 14-3-3 groove. Concluding, fluorination of the scaffold enhanced stabilizing efficiency of the ChREBPα/14-3-3 complex, by strengthening the interactions at the rim of the PPI interface.

Molecular glues stabilizing the ChREBPα/14-3-3 interaction rescue human β-cells from glucolipotoxic death

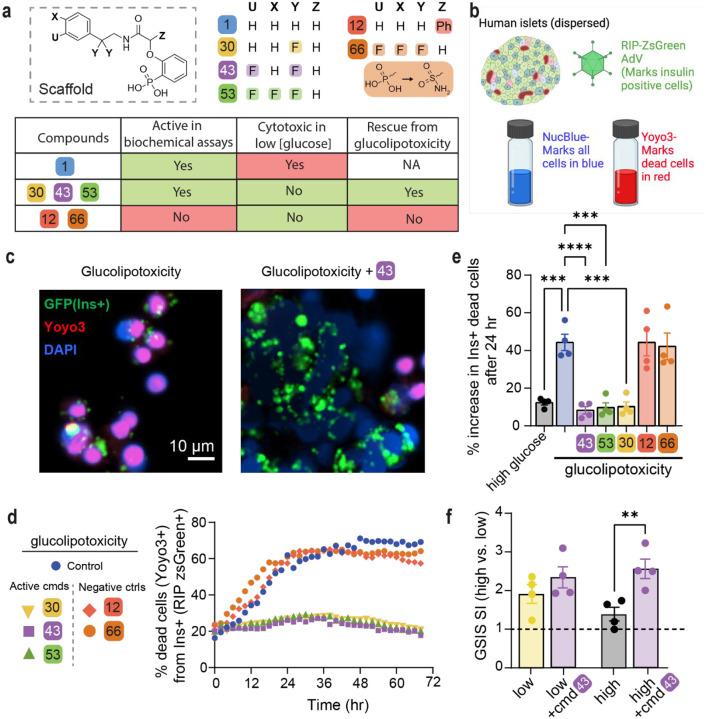

We tested six compounds (1, 12, 30, 43, 53, 66) for cytotoxicity and their ability to protect β-cells from glucolipotoxicity (summarized in Fig. 4a). Compound 1, our previously reported parent compound that was moderately active in the biochemical assay, displayed cytotoxicity in INS-1 cells. In contrast, compounds 30, 43 and 53, which were all active in biochemical assays, demonstrated no cytotoxicity in INS-1 cells and protected the β-cells from glucolipotoxicity, turning them into candidates for further cellular evaluation. Compounds 12 and 66, which served as control compounds, were not active in the biochemical assay and were also neither generally cytotoxic nor rescued the cells from glucolipotoxicity. To test the efficacy of our compounds in mitigating β-cell death from glucolipotoxicity, we conducted dose-response experiments in rat insulinoma, β-cell-like INS-1 cells43. We observed a significant attenuation of cell death in response to glucolipotoxic conditions at 5 and 10 μM of active compounds 30, 43, and 53, but not in the presence of the inactive compounds 12 or, 66 (Fig. S15a). To investigate cadaveric human islets, we optimized the single-cell and population-level analyses using real-time kinetic labeling (SPARKL) assay44, that measures the kinetics of overall proliferation (cell count, using NucBlue) or cell death rates (using YoYo3) specifically in β-cells using the rat insulin promoter (RIP)-ZSGreen adenovirus45 (Fig 4b, Fig S15a–c). The active compounds (30, 43, 53) all exhibited a remarkable decrease in β-cell death in glucolipotoxic conditions, as observed in Fig 4c, 4d, 4e while the ‘inactive’ control compounds showed no activity. Notably, for all five tested compounds, there was no discernible impact on β-cell number, indicating that over the course of 72 h, no meaningful proliferation occurred in treatment groups (Fig S15b–c). We also performed glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) in primary human islets pre-treated for 24 h with 43, in low or high glucose conditions. Remarkably, we found that 43 improved glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) stimulation index (SI) in high glucose (Fig 4f) with no effect on SI in response to KCl or on insulin content (Fig S15d–e).

Fig 4: Active compounds protect human β-cells from glucolipotoxicity.

a. Overview of compounds included in cellular assays. Table shows results of cytotoxicity and β-cell rescue from glucolipotoxicity in the presence of the compounds (green indicates positive outcome and red cytotoxicity). b. Schematic of adaptation to the SPARKL assay in human islets to specifically monitor β-cells. c. Representative figures from d at 48 h with 43. The results are representative from 4 different human cadaveric donors. d. Representative kinetics of β-cell death in glucolipotoxicity (20 mM glucose+500 μM palmitate), in the presence of 10 μM of the indicated compounds. e. Quantification of β-cell death (assessed by Yoyo3+% of GFP+ cells) at 24 h from d. f. Human islets were treated for 24 h as indicated, followed by quantification of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) in KREBS buffer (2.8 mM glucose, 1% BSA) over 30 min. The corresponding GSIS-stimulation index (SI) was obtained by determining the ratio of insulin release at high vs low glucose. Data are means +/−SEM; n=4; p<0.01**, p<0.01; ***, p<0.005; ****, pP<0.001.

Our method was validated using TUNEL staining at 48 h using 10 μM 43 to show similar cell death patterns as the kinetic measurement (Fig S16). Indeed, 43, which we focus on for the rest of this study, also prevented glucose-stimulated proliferation, confirming our previous studies8, 25, 46 and glucolipotoxic cell death in INS-1 cells (Fig S17). Together, these studies demonstrated that the three active compounds (30, 43, 53) prevent β-cell death while maintaining and even enhancing β-cell function in the context of glucolipotoxicity. Importantly. we also demonstrated that the effects of 43 were mediated by ChREBPβ as silencing of ChREBPβ had a similar effect on protection from glucolipotoxicity in human islet cells, while overexpression of ChREBPβ led to increased cell death under low, high, and glucolipotoxic conditions, and 43 was unable to protect human islet cells from apoptosis due to overexpression of ChREBPβ (Fig S18).

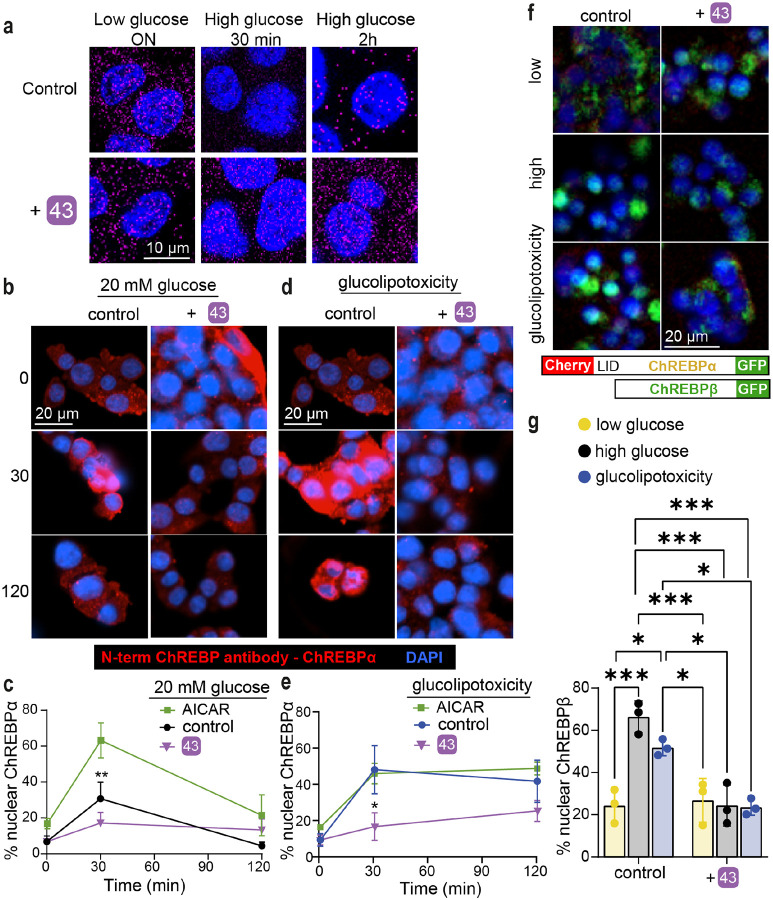

Compound 43 stabilizes the ChREBPα/14-3-3 interaction in situ preventing ChREBPα’s nuclear translocation in response to glucose or glucose + palmitate

To explore the mechanism by which 43 acts in cellulo as a molecular glue, we performed three sets of experiments. First, a proximity ligation assay (PLA) was employed in INS-1 cells using an antibody against ChREBPα and a pan 14-3-3 antibody. PLA assays show a fluorescent signal only when proteins are in close (<40 nm) and stable proximity to each other47. In low glucose, we observed an interaction between 14-3-3 and ChREBPα. By contrast, following exposure to high glucose for 30 min, ChREBPα no longer interacted with 14-3-3, but the interaction was restored after 2 h (Fig 5a). These observations are consistent with our previous study showing that ChREBPα transiently enters the nucleus to begin the feed-forward induction of ChREBPβ25. Remarkably, in the presence of 43, the interaction between 14-3-3 and ChREBPα remained unchanged at high glucose concentrations, thus confirming that 43 stabilized the interaction between 14-3-3 and ChREBPα in high glucose. In a second set of experiments, in which nuclear localization of ChREBPα was studied using a ChREBPα-specific antibody, we again found the same dynamics; ChREBPα entered the nucleus after 30 min of high glucose and exited the nucleus after 2 h. However, 43 blocked the transient translocation of ChREBPα in response to glucose (Fig. 5b, 5c). To confirm specificity of 14-3-3 binding to ChREBPα, we also studied the dissociation of 14-3-3 from NFATC1, previously demonstrated to translocate into the nucleus in response to glucose stimuli48, 49. In the presence and absence of 43, glucose promoted 14-3-3 dissociation from NFATC1, demonstrating the selectivity of our molecular glue to stabilize the interaction of ChREBPα and 14-3-3 (Fig S19). Under glucolipotoxic conditions (20 mM glucose + 500 μM palmitate), we observed a similar translocation of ChREBPα to the nucleus after 30 min, however, the nuclear clearance of ChREBPα under glucolipotoxic conditions took longer compared to high glucose alone (Fig. 5d, 5e). AMPK activity cannot mediate 43’s effects since in the presence of 1 mM AICAR, a widely used AMPK activator, translocation of ChREBPα is not blocked (Fig 5c, 5e). Because our nuclear translocation studies are based on immunodetection, this positive outcome could be a result of epitope masking, e.g. by a ChREBPα interaction with the transcription machinery or other heteropartners, which could block antibody binding. Therefore, a third approach used CRISPR/Cas9 engineered INS-1 cells 2525252525252525252525252525wherein fluorescent tags to the 5′ and 3′ ends of ChREBP were added25. An mCherry tags the N-terminal LID domain, which identifies ChREBPα exclusively, and an eGFP tag on the C-terminus represents both ChREBPα and ChREBPβ. In these cells, ChREBPα appears as yellow (red+green), and ChREBPβ appears green. Compound 43 clearly prevents the built up of nuclear ChREBPβ in both high glucose and glucolipotoxic conditions, thus confirming the immunostaining results (Fig. 5f, 5g). Together, these studies demonstrate that 43 stabilizes the interaction of 14-3-3 and ChREBPα under conditions of hyperglycemia and glucolipotoxicity.

Fig. 5: 43 stabilizes ChREBPα/14-3-3 interaction and thus retains cytoplasmic ChREBPα localization in response to glucose and glucolipotoxicity.

a. Proximity ligation assay demonstrating increased interaction between 14-3-3 and ChREBPα. INS-1 cells were cultured overnight (ON) at low (5.5 mM) glucose and exposed to high (20 mM) glucose for the indicated times b, d. Representative figures showing the nuclear localization of ChREBPα after exposure to high glucose (b) or glucolipotoxic (d) conditions. c, e. Time course of nuclear localization of ChREBPα based on figures b, d, respectively in addition to 1mM AICAR. f, g. CRISPR/Cas9 engineered INS-1 cells treated with the indicated compounds for 24 h; Low-5.5 mM glucose, High-20 mM glucose, glucolipotoxicity-20 mM glucose+500 μM palmitate. f. Representative images at 24 h. g. Quantification of % nuclear ChREBP at 24 h. Data are the means +/− SEM, n=3–5, *p<0.05, **p<0.01.

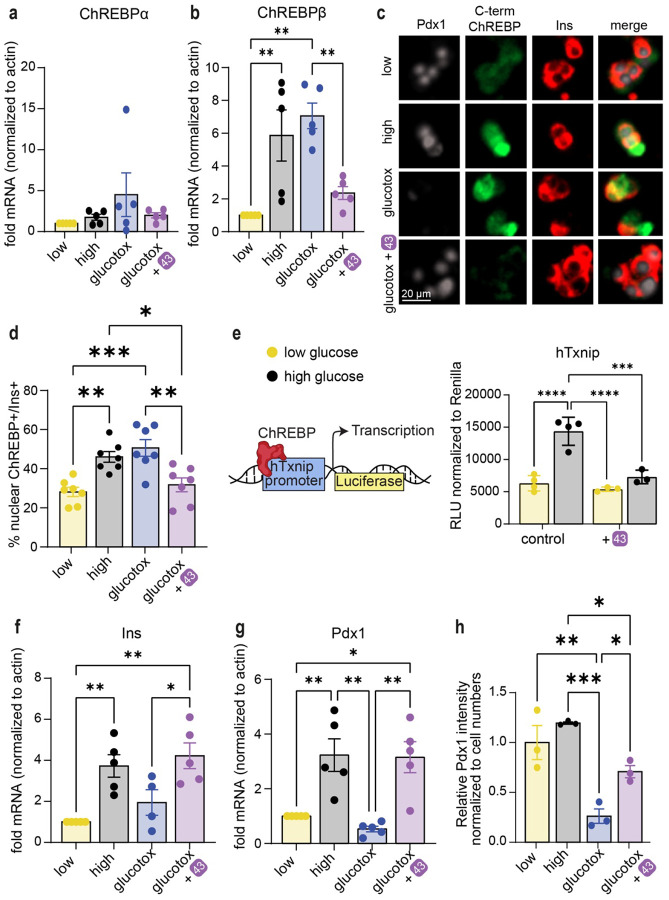

Effect of stabilizers on ChREBP downstream genes and preservation of β-cell identity

Next, we assessed the effect of stabilizers on transcription of the ChREBP splice isoforms in human islets. While ChREBPα mRNA levels remained relatively stable in all conditions tested (Fig. 6a), ChREBPβ, which contains a well characterized carbohydrate response element (ChoRE) on its promoter24, 46, was upregulated in response to high glucose, or to high glucose and high palmitate (glucolipotoxicity). Interestingly, compound 43 prevented upregulation of ChREBPβ both at mRNA level (Fig. 6b) and at protein level (Fig. 6c, 6d), indicating that inhibition of the nuclear translocation of ChREBPα by strengthening the ChREBPα/14-3-3 interaction with 43 is required for the blocking of the upregulation of glucose responsive genes such as ChREBPβ. TXNIP is another glucose responsive gene, which also contains a well characterized ChoRE50 and its upregulation is implicated in oxidative stress and β-cell death51. Promoter luciferase assays demonstrated that 43 prevents the glucose response of the TXNIP gene (Fig. 6e). Importantly, β-cell identity marker genes, INS (Fig. 6f) and PDX1 (Fig. 6g), were both downregulated at the mRNA level in human islets exposed to glucolipotoxicity, consistent with the previously reported de-differentiation phenotype pertinent to β-cell demise52, 53. Yet, in the presence of 43 this de-differentiation was prevented (Fig. 6f, 6g). Similarly, immunostaining for PDX1 showed a marked decrease in PDX1 protein levels in glucolipotoxicity, which was rescued by 43 (Fig. 6c, 6h). We also tested by qPCR in human islets other known 14-3-3 interactors, including USP8, RELA, PIN1, NFATC1 and BRAF (Fig S20a–e). Other β-cell maturity markers or glucose sensing and processing genes were unchanged by 43 (Fig S20f–i). However, the β-cell dedifferentiation marker-ALDH1A354 was significantly decreased by 43 in low glucose concentrations but unaffected in high glucose or glucolipotoxicity (Fig S20j). To test functional consequences, we measured the effects of 43 on Ca+2 signaling in INS-1 cells, where 43 had no effect on calcium upregulation in response to glucose (Fig S21a). However, 43 enhanced mitochondrial activity in high glucose as evidenced by both active mitochondria staining (Fig S21b) and ATP/ADP ratio (Fig S21c). Together these data suggest that silencing ChREBPβ by 43 decreases de novo lipogenesis leading to less accumulation of toxic lipid species like ceramides, improving mitochondrial function.

Fig. 6: 43 preserves β-cell identity in glucolipotoxicity and prevents upregulation of ChREBPβ in high glucose and glucolipotoxicity.

a,b,f,g. mRNA fold-enrichment over control low glucose in human islets, treated with 10 μM 43 for 24 h; Low-5.5 mM glucose, High-20 mM glucose, glucotox-20 mM glucose+500 μM palmitate. c, d, h. Immunostaining for Pdx1, c-term ChREBP, and insulin in dispersed islets treated for 48 h with the indicated treatments. e. INS-1 cells expressing luciferase driven by the human TXNIP promoter were incubated for 24 h at the indicated glucose concentrations, in the presence or absence of 10 μM 43. Data are the means +/− SEM, n=3–7, *p<0.05, **p<0.01***, p<0.005, ****, p<0.001.

Discussion

The global epidemic of T2D necessitates the development of novel therapeutic and preventive strategies to arrest the progressive nature of this disease55. ChREBP is an important regulator of glucose levels and is increasingly recognized as a potential target for T2D treatment56. A small molecule regulation of its function is however challenging as TFs are notoriously difficult to target with ‘classical’ small molecules. Here, we sought to develop a molecular glue approach, based on the use of novel small molecule PPI stabilizers, molecular glues, for the ChREBPα/14-3-3 PPI. These compounds were then used to test if retention of ChREBPα in the cytoplasm may lead to a persistent, chemotherapeutically exploitable inactivation of its transcriptional activity. Through the development of cellularly active molecular glues, we were able to demonstrate that this unconventional strategy for targeting TF functions via TF retention in the cytoplasm indeed resulted in the desired, consistent, and efficacious glucolipotoxicity rescue phenotype. We also did not observe significant cytotoxicity on a cellular level. Besides its implications for T2D therapy, we therefore believe that 14-3-3 or other scaffold-mediated retention of TFs in the cytoplasm via customized molecular glues may represent a broader therapeutic approach that may also be extended to other, difficult to target TFs with medicinal relevance. This strategy also complements other non-conventional ‘molecular glue’ or PROTAC TF approaches such as TRAFTACs or other TF targeted degradation systems57, 58.

Sequence alignments59 of the interacting regions between 14-3-3 proteins and ChREBPα display the conserved sequences of the α2 and α3 helices of ChREBPα across multiple species, including human, chimpanzee, gorilla, rat, and mouse (Fig S22a). The alignment of specific 14-3-3 helices (helices 9, 7, and 3) that interact with ChREBPα’s α2 helix, highlighted in red within the crystal structure model demonstrates sequence conservation across the seven human 14-3-3 isoforms (Fig S22b top). Cross-species alignment (human, chimpanzee, gorilla, rat, and mouse) for the 14-3-3 sigma isoform underscores the evolutionary conservation of interaction domains (Fig S22b bottom), suggesting functional relevance in ChREBPα’s regulation by 14-3-3 proteins.

Our cellular active molecular glues simultaneously engage both protein partners in the composite ChREBPα/14-3-3 binding pocket, causing a cooperativity factor up to 220 for this PPI. The addition of geminal-difluoro groups increased the PPI stabilization efficiency significantly, overall leading to compounds with micromolar cellular potency. On a molecular level, this enhanced PPI stabilization by fluorination of the molecular glues was achieved by stimulating the clamping of helix-9 of 14-3-3 and contacting hydrophobic amino acids at the interaction surface of the ChREBPα/14-3-3 complex. This molecular mechanism also resulted in a very high selectivity of the compounds for the stabilization of the ChREBPα/14-3-3 PPI over other 14-3-3-based PPIs. Selective interfacing of these molecular glues with amino acid residues that only occur in the context of this specific PPI complex, thus result both in a large cooperative effect for PPI stabilization and high selectivity. Combined, this high cooperativity and selectivity for the ChREBPα/14-3-3 PPI, and probably increased membrane permeability, conferred cellular activity to our lead compound.

Our studies also shed further light on the function and suitability of ChREBP as a target in metabolic disease. As T2D progresses, there is a progressive decline in β-cell mass due to the metabolic overload associated with a diabetic environment. ChREBP has long been identified as a potential mediator of this decline, in part by activating the pro-oxidative protuberant, TXNIP50. Indeed, clinical trials have been launched with compounds that inhibit the induction of TXNIP in T1D60. We recently described the destructive feed-forward production of ChREBPβ in β-cells in the context of prolonged hyperglycemia and diabetes25, 60–62. Unrestrained ChREBPβ leads to increased oxidative stress, which in turn leads to decreased expression of transcription factors necessary to maintain β-cell identity and function. Importantly, we found that deletion of the ChREBPβ isoform, using the Cre/Lox system, completely rescues β-cells from cell death and dedifferentiation due to glucolipotoxicity25. Here, we found molecular glues, which prevented ChREBPα from dissociating from 14-3-3 and initiating the feed-forward production of ChREBPβ, that were also remarkably effective at preventing cell death and dedifferentiation from glucolipotoxicity. One additional consequence of the retention of ChREBPα was that the molecular glues attenuated cell proliferation (Fig. S17f). This result was consistent with our previous findings that a modest induction of ChREBPβ is required for adaptive β-cell expansion in mice8, 25, 46. Considering molecular glues as a potential therapeutic, it is likely that preservation of β-cell mass is more clinically relevant compared to the loss of an extremely low proliferation rate of human β-cells63, 64.

ChREBPα may be anchored in the cytoplasm by elements other than 14-3-3 including sorcin, a Ca++-binding ER protein, and via C-terminal amphiphilic interactions with lipid droplets65, 66. In addition, numerous post translational modifications6, 67 as well as interaction with importin α68 may play important roles in regulating ChREBP cellular location. Since 14-3-3 and importin α compete for the same ChREBP binding region, ChREBP/importin α-PPI inhibitors, as developed by Uyeda et al.69 could potentially work synergistically with ChREBPα/14-3-3 stabilizers in suppressing the progression of T2D. Importantly, upregulation of ChREBPβ and downstream genes (i.e. TXNIP and/or DNL genes) are implicated not only in β-cell demise but also in kidney failure70, cardiac hypertrophy71, ischemic and cardiovascular diseases72, 73, liver steatosis74, and NAFLD75 in particular in high glucose setting. Inhibiting ChREBPβ and downstream genes might prove to be valuable not only for preserving β-cell mass but may also be therapeutic in other tissues for the previously listed conditions.

To summarize, we demonstrated the development of highly potent, selective, active stabilizers of the ChREBPα/14-3-3 PPI with a phosphonate chemotype that display activity in both INS-1 cell lines and primary human islets. This new compound class possibly presents the first foundations for the development of novel therapeutics against T2D. More broadly, this work delineates a novel conceptual entry to the forthcoming discoveries of molecular glues, and we envision that 14-3-3 PPI stabilization can not only be applied for the interaction with ChREBP but can be translated to other TFs as well and offers an orthogonal strategy for hard-to-drug proteins and pathways in general.

Online content

Any methods, additional references, Nature Portfolio reporting summaries, source data, extended data, supplementary information, acknowledgements, peer review information; details of author contributions and competing interests; and statements of data and code availability are available upon request

Methods

Protein expression and purification.

The 14-3-3βFL and 14-3-3σΔC isoform (full length and truncated C-terminus after T231 (ΔC to enhance crystallization)) containing a N-terminal His6 tag were expressed and purified as described previously12.

Peptide Sequences.

The N-terminal FITC labeled ChREBP-derived peptide (residues 117 – 142; sequence: RDKIRLNNAIWRAWYIQYVKRRKSPV-CONH2) was synthesized via Fmoc solid phase peptide synthesis as described previously12. N-terminal acetylated ChREBP peptide used for crystallization was purchased from GenScript Biotech Corp. Peptides used for selectivity studies were purchased from GenScript Biotech Corp with the following sequences: BRAF: (5-FAM-RDRSS(pS)APNVH-CONH2), CRAF: (5-FAM-QRST(pS)TPNVH-CONH2), ERα: (5-FAM-AEGPFA(pT)V-COOH), EXO-S: (5-FAM-KKLMFK(pT)EGPDSD-CONH2), P65: (5-FAM-EGRSAG(pS)IPGRRS-CONH2), PIN1: (5-FAM-LVKHSQSRRPS(pS)WRQEK-CONH2), USP8: (5-FAM-KLKRSY(pS)SPDITQ-CONH2).

Fluorescence Anisotropy measurements.

Fluorescein labeled peptides, 14-3-3βFL protein, the compounds (100 mM stock solution in DMSO) were diluted in buffer (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween20, 1 mg/mL Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA; Sigma-Aldrich). Final DMSO in the assay was always 1%. Dilution series of 14-3-3 proteins or compounds were made in black, round-bottom 384-microwell plates (Corning) in a final sample volume of 10 μL in duplicates.

Compound Titrations

Compound Titrations were made by titrating the compound in a 3-fold dilution series (starting at 500 μM) to a mix of FITC labeled peptide (10 nM) and 14-3-3β (concentration at EC20 value of protein-peptide complex; 150 nM for ChREBP). For the selectivity studies concentration of 14-3-3β were: 300 nM for ERα, 3.65 μM for Exo-S, 10 μM for Pin1, 250 nM for USP8, 230 nM for B-RAF, 30 μM for P65 and 450 nM for C-RAF. Fluorescence anisotropy measurements were performed directly.

Protein 2D titrations

Protein 2D titrations were made by titrating 14-3-3β in a 2-fold dilution series (starting at 300 μM) to a mix of FITC-labeled peptide (10 nM) against varying fixed concentrations of compound (2-fold dilution from 500 μM), or DMSO. Fluorescence anisotropy measurements were performed directly.

Fluorescence anisotropy values were measured using a Tecan Infinite F500 plate reader (filter set lex: 485 ± nm, lem: 535 ± 25 nm; mirror: Dichroic 510; flashes:20; integration time: 50 ms; settle time: 0 ms; gain: 55; and Z-position: calculated from well). Wells containing only FITC-labeled peptide were used to set as G-factor at 35 mP. Data reported are at endpoint. EC50 and KD values were obtained from fitting the data with a four-parameter logistic model (4PL) in GraphPad Prism 7 for Windows. Data was obtained and averaged based on two independent experiments.

Cooperativity Analysis.

The cooperativity parameters for compound 1, 30, 43 and 53 for 14-3-3 and ChREBP were determined by using the thermodynamic equilibrium system as described previously76. The data from 2D-titrations was provided to the model including the KDI = 1.5 μM, P_tot = 10 nM, and the variable concentrations of 14-3-3 and stabilizer at each data point. Fit parameters were given the following initial guess values: KDII: 500 μM, α: 100.

X-Ray crystallography data collection and refinement.

A mixture of Ac-ChREBP peptide and compound (2 μL of 5 mM stock ChREBP peptide + 0.5 μL of 100 mM stock compound) was mixed in crystallization buffer (CB: 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 2 mM MgCl2, 2 mM βME) to a final concentration of 4 μL. This was added to preformed 14-3-3σ/peptide 2d crystals at 4 °C that were produced as described previously13. Single crystals were fished after 7 days of incubation at 4 °C, and flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen. Diffraction data was collected at either the Deutsche Elektronen-Synchrotron (DESY Petra III beamline P11 proposal 11011126 and 11010888, Hamburg, Germany (crystal structures of compound 1 and 30), or at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF Grenoble, France, beamline ID23–2 proposal MX2268) (crystal structures of compound 43 and 42). Initial data processing was performed at DESY using XDS77 or at ESRF using DIALS78 after which pre-processed data was taken towards further scaling steps, molecular replacement, and refinement.

Data was processed using the CCP4i2 suite79 (version 8.0.003). After indexing and integrating the data, scaling was done using AIMLESS80. The data was phased with MolRep81 using 4JC3 as a template. Presence of soaked ligands and ChREBP-peptide was verified by visual inspection of the Fo-Fc and 2Fo-Fc electron density maps in COOT82 (version 0.9.6). If electron density corresponding to ligand and peptide was present, the ChREBP peptide was built in and the structure and restrains of the ligands were generated using AceDRG83, followed by model rebuilding and refinement using REFMAC584. The PDB REDO85 server (pdb-redo.edu) was used to complete the model building and refinement. The images were created using the PyMOL Molecular Graphics System (Schrödinger LLC, version 2.2.3). For refinement statistics see Table S4.

The structures were deposited in the protein data bank (PDB) with IDs: 8BTQ (compound 1), 8C1Y (compound 30), 8BWH (compound 42) and 8BWE (compound 43).

Synthesis of SAR library for 1.

Detailed synthetic procedures and characterization of compounds marked with a star (*) in Table S1 were described previously12. The synthetic procedure and characterization of all remaining compounds are provided in the Supplemental Methods. Generally, all compounds obtained had been purified by reversed-phase high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and characterized by liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (LC-MS) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR; 400 MHz for 1H NMR and 100 MHz for 13C NMR). Compounds were prepared as 100 mM stock solutions in DMSO before use in experiments, and stored at −20 °C.

Cell lines.

INS-1–derived 832/13 rat insulinoma cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium with 10% FBS, 10 mM HEPES, 2 mM L-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, and 50 mM β-mercaptoethanol 100U/mL penicillin, 100 mg/mL streptomycin and further supplemented with 11 mM glucose, at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. Human islets were isolated from human cadaveric islets donors provided by the NIH/NIDDK-supported Integrated Islet Distribution Program (IIDP) (https://iidp.coh.org/overview.aspx), and from Prodo Labs (https://prodolabs.com/), the University of Miami, the University of Minnesota, the University of Wisconsin, the Southern California Islet Cell Resource enter, and the University of Edmonton, as summarized in Supplementary Table 5 Informed consent was obtained by the Organ Procurement Organization (OPO), and all donor information was de-identified in accord with Institutional Review Board procedures at The Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai (ISMMS). Human islets were cultured and dispersed as previously described8.

Adenovirus.

Human islets were transduced with RIP-ZsGreen at MOI of 100. Overnight, the following day, islets were dispersed, and seeded in RPMI with 100U/mL penicillin, 100 mg/mL streptomycin in the presence of an additional 100 MOI of the virus for 2–4 h. Following, FBS was added to a final concentration of 10%, compounds added and cells were continuously imaged for the course of 48–72 h.

Immunostaining.

INS-1 cells or dispersed human islet cells were plated on 12-mm laminin-coated glass coverslips. Cells were treated with the indicated conditions and times. Cells were washed with PBS and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. Immunolabeling was performed as previously described25 with primary antibodies directed against N-terminus ChREBP (1:250,25), C-terminus ChREBP (Novus, 1:250), Pdx1 (Abcam, 1:500), and Insulin (Fisher, 1:1000)

Glucose stimulated Insulin Secretion (GSIS) analysis.

20 IEQ primary human were placed in 12 μm pore diameter inserts (Millipore) and incubated for 24 h with indicated treatment. Following, media was replaced with KREBS containing 2.8 mM glucose and 1% BSA and GSIS analysis was performed as previously described48. Insulin levels were measured using a commercial ELISA assay (Mercodia), following the manufacturer instructions.

qPCR and PCR.

mRNA was isolated using the Qiagen RNAeasy mini kit for INS-1 cells, or for islets using the Qiagen RNAeasy mini kit. cDNA was produced using the Promega m-MLV reverse transcriptase. qPCR was performed on the QuantStudio5 using Syber-Green (BioRad) and analysis was performed using the ΔΔCt method. PCR for genotyping was performed using standard methods. Primer sequences are shown in Table S6.

Proximity Ligation Assay (PLA).

PLA was used to determine endogenous protein–protein interactions as previously described in86. Briefly, ChREBPα (by GenScript) or NFATC1 (cell signaling) and Pan-14-3-3 (Santa Cruz) antibodies were conjugated to Duolink oligonucleotides, PLUS and MINUS oligo arms, respectively, using Duolink® In Situ Probemaker Following a PBS wash, cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde solution for 10 min at room temperature, and blocked with Duolink Blocking Solution for 1 h at 37 °C and then incubated with 4 μg/mL ChREBPα-Plus and 14-3-3-MINUS overnight at 4 °C. PLA was performed according to the manufacturer’s directions. No secondary antibodies were used, because PLUS and MINUS oligo arms were directly conjugated to ChREBP and 14-3-3. Cells were imaged on a Zeiss 510 NLO/Meta system (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany), using a Plan-Apochromat 63×/1.40 oil differential interference contrast objective.

Proliferation and cell death.

Cellular proliferation and cell death was quantified using Real-Time Kinetic Labeling (SPARKL) technique22. Syto21 marked all cells, Yoyo3 marked all dead cells.

Calcium Imaging.

INS-1 cells seeded on glass bottom dish at low glucose. After 24 h media was replaced with KREBs buffer containing 5.5 mM glucose. Following 1 h incubation, Fluo-4 AM was added and incubated with cells for 45 min. The cells were then imaged at low glucose concentrations for 1 min, with images captured at 6 sec intervals. Glucose was supplemented to the cells to reach a final concentration of 20 mM and imaging was continued with the same settings for 5 additional min. The images were acquired using the confocal Cytation 10 system. Fluo-4 intensities were calculated using Gen5 Software.

Active mitochondria staining.

INS-1 cells were incubated with 250 nM MitoTracker® Orange CM-H2TMRos (Life Technologies, Eugene, OR) for 30 min at 37°C. Mitochondrial activity was analyzed based on fluorescence intensity using a confocal Cytation 10 system and Gen 5 software.

ATP/ADP measurements.

Measurements were performed using a commercially available ADP/ATP bioluminescent kit (Abcam).

Luciferase Reporter.

The reporter assays were done as described previously17. Briefly, INS-1-derived 832/13 cells that stably express the luciferase reporter gene under control of the human TXNIP promoter. Cells were harvested after 24 h and luciferase activity was measured using the Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega, Cat. #E1500) on Victor Nivo luminometer (PerkinElmer). Firefly luciferase activity was normalized to Renilla luciferase activity.

Statistics.

All studies were performed with a minimum of three independent replications. Data were represented in this study as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA on GraphPad (Prism) V9.2.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

This work was supported by the European Union through ERC Advanced Grant PPI-Glue (101098234), the Netherlands Ministry of Education, Culture and Science (Gravity program 024.001.035). The Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (ECHO grant 711.018.003), and by DFG-funded CRC1093 (Supramolecular Chemistry on Proteins). Views and opinions expressed are however those of the authors only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Council. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them. DKS grant support from NIH/NIDDK R01DK130300 and the Human Islet and Adenoviral Core (HIAC) of P30DK020541.

We thank Michelle Arkin (UCSF) for stimulating discussions. We thank Sr. Sarah Stanley for help with Calcium imaging and members of the Diabetes Obesity and Metabolism Institute at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai for useful discussions. We acknowledge DESY (Hamburg, Germany), a member of the Helmholtz Association HGF, for the provision of experimental facilities. Parts of this research were carried out at PETRA III and we would like to thank Johanna Hakanpää for assistance in using beam P11. Beamtime was allocated for proposals 11011126 and 11010888. Further, we acknowledge the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) for provision of synchrotron radiation facilities and thank Shibom Basu for assistance and support in using beamline ID23-2 (mx2407).

List of Abbreviations

- ChREBP

carbohydrate response element binding protein

- ChoRE

carbohydrate response element

- TF

transcription factor

- PPI

protein-protein interaction

- T2D

type 2 diabetes

- AMP

adenosine monophosphate

- LID

low glucose inhibitory domain

- NES

nuclear export signal

- SAR

structure-activity relationship

- α

cooperativity factor

- FA

fluorescence anisotropy

- KdII

intrinsic compound affinity

- SPARKL

single-cell and population-level analyses using real-time kinetic labeling

- RIP

rat insulin promoter

- GSIS

glucose-stimulated gene expression

- SI

stimulation index

- PLA

proximity ligation assay

Footnotes

Disclosures

US provisional patent applicaon No. 63/523,289 – Pennings M.A.M., Katz L.S. Otmann C, Scot D.K, Visser E.J. Plitzko K.F, Kaiser M Cossar P.J, Brunsveld, L. Small-molecule stabilizers of the ChREBP–14-3-3 interacon with cellular acvity. United States Patent and Trademark Office, June 2023

The authors declare the following compeng financial interest(s): L.B. and C.O. are founders of Ambagon Therapeucs. L.B. is a member of Ambagon’s scienfic advisory board, C.O. is employee of Ambagon.

References

- 1.Ogurtsova K. et al. IDF diabetes Atlas: Global esmates of undiagnosed diabetes in adults for 2021. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 183, 109118 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collaborators G.B.D.D. Global, regional, and naonal burden of diabetes from 1990 to 2021, with projecons of prevalence to 2050: a systemac analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 402, 203–234 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tancredi M. et al. Excess mortality among persons with type 2 diabetes. New England Journal of Medicine 373, 1720–1732 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaterjee S., Khun K. & Davies M.J. Type 2 diabetes. The lancet 389, 2239–2251 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schellenberg E.S., Dryden D.M., Vandermeer B., Ha C. & Korownyk C. Lifestyle intervenons for paents with and at risk for type 2 diabetes: a systemac review and meta-analysis. Annals of internal medicine 159, 543–551 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abdul-Wahed A., Guilmeau S. & Posc C. Sweet Sixteenth for ChREBP: Established Roles and Future Goals. Cell Metab 26, 324–341 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vijayakumar A. et al. Absence of Carbohydrate Response Element Binding Protein in Adipocytes Causes Systemic Insulin Resistance and Impairs Glucose Transport. Cell Rep 21, 1021–1035 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Metukuri M.R. et al. ChREBP mediates glucose-smulated pancreac beta-cell proliferaon. Diabetes 61, 2004–2015 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henley M.J. & Koehler A.N. Advances in targeng ‘undruggable’ transcripon factors with small molecules. Nat Rev Drug Discov 20, 669–688 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sakiyama H. et al. Regulaon of nuclear import/export of carbohydrate response element-binding protein (ChREBP): interacon of an alpha-helix of ChREBP with the 14-3-3 proteins and regulaon by phosphorylaon. J Biol Chem 283, 24899–24908 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Merla G., Howald C., Antonarakis S.E. & Reymond A. The subcellular localizaon of the ChoRE-binding protein, encoded by the Williams-Beuren syndrome crical region gene 14, is regulated by 14-3-3. Hum Mol Genet 13, 1505–1514 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sijbesma E. et al. Structure-based evoluon of a promiscuous inhibitor to a selecve stabilizer of protein-protein interacons. Nat Commun 11, 3954 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Somsen B.A. et al. Funconal mapping of the 14-3-3 hub protein as a guide to design 14-3-3 molecular glues. Chem Sci 13, 13122–13131 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rial S.A., Shishani R., Cummings B.P. & Lim G.E. Is 14-3-3 the Combinaon to Unlock New Pathways to Improve Metabolic Homeostasis and beta-Cell Funcon? Diabetes 72, 1045–1054 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiang W. et al. Molecular Evoluon of Plant 14-3-3 Proteins and Funcon of Hv14-3-3A in Stomatal Regulaon and Drought Tolerance. Plant Cell Physiol 63, 1857–1872 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang K., Huang Y. & Shi Q. Genome-wide idenficaon and characterizaon of 14-3-3 genes in fishes. Gene 791, 145721 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abdrabou A., Brandwein D. & Wang Z. Differenal Subcellular Distribuon and Translocaon of Seven 14-3-3 Isoforms in Response to EGF and During the Cell Cycle. Int J Mol Sci 21 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mugabo Y. et al. 14-3-3zeta Constrains insulin secreon by regulang mitochondrial funcon in pancreac beta cells. JCI Insight 7 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hermeking H. & Benzinger A. 14-3-3 proteins in cell cycle regulaon. Semin Cancer Biol 16, 183–192 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lim G.E., Piske M. & Johnson J.D. 14-3-3 proteins are essenal signalling hubs for beta cell survival. Diabetologia 56, 825–837 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Otmann C. et al. Phosphorylaon-independent interacon between 14-3-3 and exoenzyme S: from structure to pathogenesis. EMBO J 26, 902–913 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sato S. et al. Metabolite Regulaon of Nuclear Localizaon of Carbohydrate-response Element-binding Protein (ChREBP): ROLE OF AMP AS AN ALLOSTERIC INHIBITOR. J Biol Chem 291, 10515–10527 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ge Q. et al. Structural characterizaon of a unique interface between carbohydrate response element-binding protein (ChREBP) and 14-3-3beta protein. J Biol Chem 287, 41914–41921 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herman M.A. et al. A novel ChREBP isoform in adipose ssue regulates systemic glucose metabolism. Nature 484, 333–338 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Katz L.S. et al. Maladapve posive feedback producon of ChREBPbeta underlies glucotoxic beta-cell failure. Nat Commun 13, 4423 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakagawa T. et al. Metabolite regulaon of nucleo-cytosolic trafficking of carbohydrate response element-binding protein (ChREBP): role of ketone bodies. J Biol Chem 288, 28358–28367 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou P., Zou J., Tian F. & Shang Z. Fluorine Bonding How Does It Work In Protein− Ligand Interacons? Journal of chemical information and modeling 49, 2344–2355 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dalvit C., Invernizzi C. & Vulpe A. Fluorine as a hydrogen-bond acceptor: Experimental evidence and computaonal calculaons. Chemistry–A European Journal 20, 11058–11068 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okiyama Y., Fukuzawa K., Komeiji Y. & Tanaka S. Taking water into account with the fragment molecular orbital method. Quantum Mechanics in Drug Discovery, 105–122 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shah P. & Westwell A.D. The role of fluorine in medicinal chemistry. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem 22, 527–540 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Purser S., Moore P.R., Swallow S. & Gouverneur V. Fluorine in medicinal chemistry. Chem Soc Rev 37, 320–330 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Geertjens N.H., de Vink P.J., Wezeman T., Markvoort A.J. & Brunsveld L. A general framework for straighorward model construcon of mul-component thermodynamic equilibrium systems. bioRxiv, 2021.2011. 2018.469126 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thiel P. et al. Virtual screening and experimental validaon reveal novel small-molecule inhibitors of 14-3-3 protein-protein interacons. Chem Commun (Camb) 49, 8468–8470 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao J. et al. Discovery and structural characterizaon of a small molecule 14-3-3 protein-protein interacon inhibitor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108, 16212–16216 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu H., Ge J. & Yao S.Q. Microarray-assisted high-throughput idenficaon of a cell-permeable small-molecule binder of 14-3-3 proteins. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 49, 6528–6532 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park E. et al. Architecture of autoinhibited and acve BRAF-MEK1–14-3-3 complexes. Nature 575, 545–550 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Molzan M. et al. Stabilizaon of physical RAF/14-3-3 interacon by cotylenin A as treatment strategy for RAS mutant cancers. ACS Chem Biol 8, 1869–1875 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wolter M. et al. Fragment-Based Stabilizers of Protein–Protein Interacons through Imine-Based Tethering. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 59, 21520–21524 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Centorrino F., Ballone A., Wolter M. & Otmann C. Biophysical and structural insight into the USP8/14-3-3 interacon. FEBS Lett 592, 1211–1220 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.De Vries-van Leeuwen I.J. et al. Interacon of 14-3-3 proteins with the estrogen receptor alpha F domain provides a drug target interface. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110, 8894–8899 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cossar P.J. et al. Reversible Covalent Imine-Tethering for Selecve Stabilizaon of 14-3-3 Hub Protein Interacons. J Am Chem Soc 143, 8454–8464 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Andrei S.A. et al. Raonally Designed Semisynthec Natural Product Analogues for Stabilizaon of 14-3-3 Protein-Protein Interacons. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 57, 13470–13474 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hohmeier H.E. et al. Isolaon of INS-1-derived cell lines with robust ATP-sensive K+ channel-dependent and -independent glucose-smulated insulin secreon. Diabetes 49, 424–430 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gelles J.D. et al. Single-Cell and Populaon-Level Analyses Using Real-Time Kinec Labeling Couples Proliferaon and Cell Death Mechanisms. Dev Cell 51, 277–291 e274 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang H. et al. Insights into beta cell regeneraon for diabetes via integraon of molecular landscapes in human insulinomas. Nat Commun 8, 767 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang P. et al. Inducon of the ChREBPbeta Isoform Is Essenal for Glucose-Smulated beta-Cell Proliferaon. Diabetes 64, 4158–4170 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alam M.S. Proximity Ligaon Assay (PLA). Curr Protoc Immunol 123, e58 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang P. et al. A high-throughput chemical screen reveals that harmine-mediated inhibion of DYRK1A increases human pancreac beta cell replicaon. Nat Med 21, 383–388 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang P. et al. Disrupng the DREAM complex enables proliferaon of adult human pancreac β cells. The Journal of clinical investigation 132 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Minn A.H., Hafele C. & Shalev A. Thioredoxin-interacng protein is smulated by glucose through a carbohydrate response element and induces beta-cell apoptosis. Endocrinology 146, 2397–2405 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Oslowski C.M. et al. Thioredoxin-interacng protein mediates ER stress-induced β cell death through iniaon of the inflammasome. Cell metabolism 16, 265–273 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Accili D. et al. When beta-cells fail: lessons from dedifferenaon. Diabetes Obes Metab 18 Suppl 1, 117–122 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cin F. et al. Evidence of beta-Cell Dedifferenaon in Human Type 2 Diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 101, 1044–1054 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim-Muller J.Y. et al. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1a3 defines a subset of failing pancreac β cells in diabec mice. Nature communications 7, 12631 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wysham C. & Shubrook J. Beta-cell failure in type 2 diabetes: mechanisms, markers, and clinical implicaons. Postgrad Med 132, 676–686 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Song Z., Yang H., Zhou L. & Yang F. Glucose-Sensing Transcripon Factor MondoA/ChREBP as Targets for Type 2 Diabetes: Opportunies and Challenges. Int J Mol Sci 20 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hines J., Largue S., Dong H., Qian Y. & Crews C.M. MDM2-recruing PROTAC offers superior, synergisc anproliferave acvity via simultaneous degradaon of BRD4 and stabilizaon of p53. Cancer research 79, 251–262 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Samarasinghe K.T. et al. OligoTRAFTACs: a generalizable method for transcripon factor degradaon. RSC Chemical Biology 3, 1144–1153 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Madeira F. et al. The EMBL-EBI Job Dispatcher sequence analysis tools framework in 2024. Nucleic Acids Res 52, W521–W525 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Forlenza G.P. et al. Effect of Verapamil on Pancreac Beta Cell Funcon in Newly Diagnosed Pediatric Type 1 Diabetes: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 329, 990–999 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Borowiec A.M., Właszczuk A., Olakowska E. & Lewin-Kowalik J. TXNIP inhibion in the treatment of diabetes. Verapamil as a novel therapeuc modality in diabec paents. Medicine and Pharmacy Reports 95, 243 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Couper J. Preserving Pancreac Beta Cell Funcon in Recent-Onset Type 1 Diabetes. JAMA 329, 978–979 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Meier J.J. et al. Beta-cell replicaon is the primary mechanism subserving the postnatal expansion of beta-cell mass in humans. Diabetes 57, 1584–1594 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang P. et al. Diabetes mellitus--advances and challenges in human beta-cell proliferaon. Nat Rev Endocrinol 11, 201–212 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mejhert N. et al. Paroning of MLX-Family Transcripon Factors to Lipid Droplets Regulates Metabolic Gene Expression. Mol Cell 77, 1251–1264 e1259 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Noordeen N.A., Meur G., Ruter G.A. & Leclerc I. Glucose-induced nuclear shutling of ChREBP is mediated by sorcin and Ca2+ ions in pancreac β-cells. Diabetes 61, 574–585 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Katz L.S., Baumel-Alterzon S., Scot D.K. & Herman M.A. Adapve and maladapve roles for ChREBP in the liver and pancreac islets. J Biol Chem 296, 100623 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ge Q. et al. Imporn-alpha protein binding to a nuclear localizaon signal of carbohydrate response element-binding protein (ChREBP). J Biol Chem 286, 28119–28127 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jung H. et al. The structure of imporn alpha and the nuclear localizaon pepde of ChREBP, and small compound inhibitors of ChREBP-imporn alpha interacons. Biochem J 477, 3253–3269 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Huang C. et al. Thioredoxin interacng protein (TXNIP) regulates tubular autophagy and mitophagy in diabec nephropathy through the mTOR signaling pathway. Sci Rep 6, 29196 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yoshioka J. et al. Thioredoxin-interacng protein controls cardiac hypertrophy through regulaon of thioredoxin acvity. Circulation 109, 2581–2586 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Domingues A., Jolibois J., Marquet de Rouge P. & Nivet-Antoine V. The Emerging Role of TXNIP in Ischemic and Cardiovascular Diseases; A Novel Marker and Therapeuc Target. Int J Mol Sci 22 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Guo S., Zheng F., Qiu X. & Yang N. ChREBP gene polymorphisms are associated with coronary artery disease in Han populaon of Hubei province. Clin Chim Acta 412, 1854–1860 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Denechaud P.D., Denn R., Girard J. & Posc C. Role of ChREBP in hepac steatosis and insulin resistance. FEBS Lett 582, 68–73 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Calle R.A. et al. ACC inhibitor alone or co-administered with a DGAT2 inhibitor in paents with non-alcoholic faty liver disease: two parallel, placebo-controlled, randomized phase 2a trials. Nat Med 27, 1836–1848 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Geertjens N.H.J., de Vink P.J., Wezeman T., Markvoort A.J. & Brunsveld L. Straighorward model construcon and analysis of mulcomponent biomolecular systems in equilibrium. RSC Chem Biol 4, 252–260 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kabsch W. xds. Acta Crystallographica Section D: Biological Crystallography 66, 125–132 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Winter G. et al. DIALS: implementaon and evaluaon of a new integraon package. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol 74, 85–97 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Poterton L. et al. CCP4i2: the new graphical user interface to the CCP4 program suite. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol 74, 68–84 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Evans P.R. & Murshudov G.N. How good are my data and what is the resoluon? Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 69, 1204–1214 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Vagin A. & Teplyakov A. Molecular replacement with MOLREP. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66, 22–25 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Emsley P. & Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 60, 2126–2132 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Long F. et al. AceDRG: a stereochemical descripon generator for ligands. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol 73, 112–122 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Murshudov G.N. et al. REFMAC5 for the refinement of macromolecular crystal structures. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 67, 355–367 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Joosten R.P., Joosten K., Murshudov G.N. & Perrakis A. PDB_REDO: construcve validaon, more than just looking for errors. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 68, 484–496 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Katz L.S., Argmann C., Lamberni L. & Scot D.K. T3 and glucose increase expression of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PCK1) leading to increased beta-cell proliferaon. Mol Metab 66, 101646 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.