Abstract

In all biological systems, DNA is under high mechanical stress from bending and twisting. For example, DNA is tightly bent in nucleosome complexes, virus capsids, bacterial chromosomes, or complexes with transcription factors that regulate gene expression. A structurally and mechanically accurate model of DNA is therefore necessary to understand some of the most fundamental molecular mechanisms in biology including DNA packaging, replication, transcription and gene regulation. An iconic feature of DNA is its double helical nature with an average repeat of ~10.45 base pairs per turn, which is commonly believed to be independent of curvature. We developed a ligation assay on nicked DNA circles of variable curvature that reveals a strong unwinding of DNA to over 11 bp/turn for radii around 3–4 nm. Our work constitutes a major modification of the standard mechanical model of DNA and requires reassessing the molecular mechanisms and energetics of all processes involving tightly bent DNA.

Introduction

In all cells and viruses, DNA is twisted and bent in a highly dynamic way. For example, two meters of human DNA are tightly wrapped around histone proteins, compacting it into a nucleus measuring mere micrometers across. During DNA replication and transcription, DNA unbinds from the nucleosome and relaxes its mechanical stress. DNA is also tightly bent in nanometer-sized virus capsids, bacteria, or complexes with many transcription factors that regulate gene expression. An accurate physical model of tightly bent DNA is therefore essential to understand the molecular mechanisms and energetics of many fundamental biological processes 1,2.

The twistable wormlike chain (TWLC) is the standard elastic model for DNA and treats DNA as an inextensible rod with elastic moduli controlling twist and bend deformations 3. It accurately describes circularization probabilities of long linear DNA fragments 4–8. While some studies postulated extreme bendability for short fragments 9,10, kinetic effects have likely distorted the results 11–13. Moreover, sharp kinks at nicks that release bending and torsional stress limit the usefulness of circularization experiments with short fragments and complicate the measurement of the natural helical repeat , which is the average number of base pairs that are required to complete a full helical turn in the absence of torsional stress (Supplementary Note 1, 13–15). B-DNA has an of 10.45 (±0.05) base pairs (bp) per helical turn 4–8,16,17.

Twisting and bending deformations are treated as independent by the standard TWLC model 3, and the textbook value of is widely considered to be constant for straight and bent DNA alike. This model was challenged 30 years ago by Marko and Siggia 18 and their prediction of twist-bend coupling (TBC) that would lead to an unwinding, or increase of , when DNA is bent into radii of curvatures that are well below the persistence length (50 nm). Such tight curvatures are common in biology. For example, the radius of curvature in the nucleosome is only 4.5 nm—just 10% of its persistence length—with DNA that is considerably overwound at 17,19. On the other hand, recent all-atom molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of protein-free DNA circles at similar radii predict 20–22.

However, there has been no direct experimental quantification of the change of due to TBC, as existing assays cannot precisely control curvature and measure simultaneously.

Nicked minicircle assay

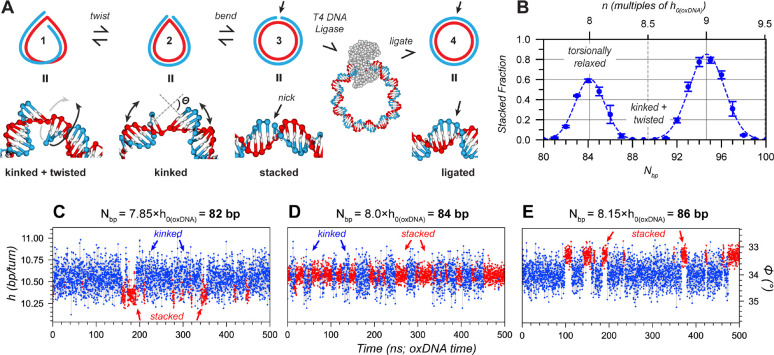

To determine of tightly bent DNA, we developed an assay using nicked DNA circles (Fig. 1). The point where the 5’ and 3’ ends of the linear strand meet is called a nick and is mechanically the weakest point in the structure. Unlike linear fragments in circularization experiments, this complex can neither unloop nor dimerize, which eliminates the impact of bending stress on complex formation (Supplementary Note 1). Three distinct conformations exist: a “stacked” state (Fig. 1A3); a “kinked” state (Fig. 1A2); and a “kinked + twisted” state in which the ends are twisted out of alignment (Fig. 1A1). Stacked states are approximately circular or oval, whereas kinked configurations are sharply bent at the nick which reduces the bending stress by lowering the DNA’s average curvature. The transition from a kinked to a stacked state is stabilized by additional π-stacking between nucleobases, but destabilized by increased bending stress; nevertheless, the energy difference between these states is small compared to the energy required for looping a linear duplex of the same length. In a “kinked + twisted” conformation (Fig 1A1), the two ends cannot be realigned through bending alone, but requires an additional twisting energy that must be overcome for stacking, either by over- or underwinding.

Fig. 1. Conformational states in nicked minicircles.

(A) Representative snapshots from oxDNA simulations of nicked minicircles in a (1) kinked + twisted, (2) kinked, or (3) stacked conformation (rendered with oxView 23,24). See Fig. S3 for analysis of kink angles . In a ligation experiment (Fig. 2), only the ends of stacked configurations (3) can be joined into a fully ligated circle (4). Complex with T4 DNA ligase (PDBID: 6DT1) is for size comparison and illustration only. (B) Plot of the fraction of stacked configurations from 21 different oxDNA simulations of nicked circles between 80–100 bp. Dotted line: Gaussian fits. (C-E) Analysis of dynamics between kinked (blue) and stacked (red) conformations as well as ℎ in oxDNA simulations of nicked circles with 82 (C), 84 (D) and 86 bp (E). (scale on left) was calculated from the average twist angle between adjacent base pairs (scale on right; ). Note that kinked conformations fluctuate around the equilibrium of oxDNA (10.55 bp/turn), while stacked conformations can be overwound (C) or underwound (E).

MD simulations

We first simulated nicked minicircles with circumferences of with the coarse-grained MD model oxDNA 25. The fraction of stacked configurations in each simulation was determined through a geometrical analysis of the bases around the nick (Fig. 1B, Methods and Fig. S1). Two maxima around and 94.6 bp appear roughly at 8 and 9 multiples of the natural helical repeat of oxDNA, 26, indicating no significant change in the helical repeat compared to relaxed DNA. The minicircles are generally kinked around for integer (Fig. 1A1, Fig. S3). Transitions between stacked and kinked conformations occur within nanoseconds to microseconds (Fig. 1C–E and Fig. S6, Fig. S7, Supplementary Movies S1–4). In these simulations of tightly bent circles, is not significantly changed compared to that of relaxed DNA, indicating a weak or absent TBC in the oxDNA model.

Ligation experiments

Next, we determined the helical repeat through ligation experiments of nicked minicircles. For this, we first circularized linear oligonucleotides with all lengths between 67–105 nucleotides (nt) with a ‘splint’ into single-stranded circles (Fig. 2A–B). All strands share the same 13 nt sequences at the ends, so that one common 26 nt splint can be used for all strands. Single-stranded circles formed with near-quantitative yields, as most of the complex is single-stranded and therefore very flexible, entropically favoring circularization over dimerization (Fig. 2B). Addition of the complementary strands (Fig. 2C, blue) forms the respective nicked circles. The sequences in between the common splint-binding domains are unique such that each ss circle can only hybridize to the correct counterstrand. The resulting nicked circles (Fig. 2D) were then enzymatically ligated into topologically closed double-stranded (ds) circles (Fig. 2E). The different species including linear strands, single- and double-stranded circles, can be separated by denaturing PAGE (polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis), (F-H), which also separates ss circles and linear strands of non-ligated complexes Fig. 2E). Four to five oligonucleotides with a length difference of 4 nt were combined into eight different subpools to fit all experiments on one gel and to allow for a better relative comparison between them as indicated in Fig. 2G.

Fig. 2. Experimental ligation of nicked circles of different lengths.

(A) Splint ligation of oligonucleotides (67–105 nt) produces ss minicircles (B). oxDNA simulation snapshot illustrates flexibility of ss region. (C) Respective complementary strands are annealed to yield nicked circles (D), which can then be enzymatically ligated into double-stranded circles (E). (F) Denaturing PAGE gel. (1) Five oligonucleotides (same as pool 7 in (G) and (H)) before and (2) after splint ligation. The splints run out of the gel; (3) Hybridization to the blue complementary strand before and (4) after ligation. M = size marker (linear ds DNA). (G) Denaturing PAGE analysis of the ligation experiment at 37 °C of all nicked circles , that are distributed between eight pools as annotated. Note that some circles split into two bands (73, 83, 93, and 103 bp) indicating different topoisomers. We hypothesize that the ligase does not change of DNA and that splitting occurs at half-integer multiples of , or . Ligase concentration in the final ligation step (D to E) was 100-fold lower in experiment H (4 U/μl). Uncropped gel images, an independent repeat of experiment G and of a 0.1X [ligase] experiment are shown in Fig. S4. (I) Helical repeat for theoretically possible (grey) and experimentally observed (blue) ligated circles. Vertical lines indicate where nicked circles form two topoisomers after ligation. Red datapoints: circles that should have been observed for a constant . Circles with are torsionally relaxed ( are underwound (), and are overwound (). (J) The total mechanical energy of DNA in stacked or ligated circles is the sum of twisting energy and bending energy . At the local minima, circles are torsionally relaxed; to the left they are overwound, and to the right underwound. Red: Expected energy landscape if was constant and independent of curvature.

Equilibrium helical repeat is curvature-dependent

As only stacked configurations present the terminal 5’ phosphates and the 3’ OH groups close enough for ligation, we originally expected a band intensity profile like that in Fig. 1B and to detect TBC through a shift of maxima. However, ligation was near-quantitative at all (Fig. 2G). Reducing [ligase] (Fig. 2H, Fig. S4) or increasing [salt] (Fig. S8) increased the difference between ligation maxima and minima and indicate a clear shift towards longer , but an accurate determination of from gel band intensities was still difficult. However, at those where ligation produces two topoisomers ( and 103 bp), the energetical cost (twist energy) for unwinding or overwinding the ends from a torsionally relaxed kinked and twisted starting configuration into a ligatable stacked configuration must have been roughly equal. This is only the case if , which is equivalent to an excess twist . Therefore, and . Likewise, for and so on. If were constant at , two topoisomers would have been observed around , and instead. For any other circle length, only the topoisomer with the least torsional stress (the lowest ) is observed (see Supplementary Note 2).

Fig. 2I shows the helical repeat of circles with different lengths and linking numbers , which is the number helical turns. For a given increases linearly with with a slope of (Fig. 2I). Rings with are either over- or underwound. Two topoisomers form at the vertical lines. With additional datapoints from topoisomer splitting at 123, 143 and 164 bp (see Fig. S5), the length-dependent, or rather curvature-dependent, can be fitted through the datapoints at , where two topoisomers are observed with a function from MS [18, Fig. 3B, Supplementary Note 4, eq. 31)].

Fig. 3. Extent of change of .

(A) A 39 bp DNA fragment is displayed with decreasing radii of curvature (). All DNA with a smaller radius of curvature than is considered tightly bent. The fragment with has and is unwound by ~82° compared to the canonical 10.45 bp/turn (transparent overlay); a full circle is unwound by almost ½ turn. (B) Relaxed helical repeat of a duplex bent with a constant radius of curvature (top axis) matching that of a minicircle of base pairs (bottom axis). Green: from gel data (topoisomer splitting); black: data from circularization experiments 5–7; blue: fit using the Marko/Siggia model 18 with fit parameters (=linear DNA) and G/C = 2.7, where G is the twist-bend coupling parameter and C is the torsional stiffness; red: TBC prediction with parameters from ref. 28,29. (C) A Nucleosome (PDBID: 3LZ0) has a helical repeat of ~10.1 bp/turn 17, but a circle with this curvature is torsionally relaxed at ~11.1 bp/turn according to our measurements (D). It follows that .

In Fig. 2J, we plot the sum of the twist and bend deformation energy, (see Supplementary Note 2). Circles are torsionally relaxed if they lie on the observed curve in Fig. 2I, which connects the helical repeats of circles at the local minima of the energy shown in Fig. 2J. The measured helical repeat is not changed by lowering the ligase concentration, as band splitting is still visible at the same lengths (Fig. 2, Fig. S4). On the other hand, DNA slightly unwinds at high temperatures and low salinity 16,27, and both trends are captured by oxDNA simulations and ligation experiments (Fig. S8 - Fig. S9). In summary, our data shows that is curvature-dependent and bending unwinds DNA (Fig. 3A–B).

Discussion

DNA is commonly tightly bent or twisted in biology, and the associated mechanical stress influences all molecular mechanisms involving DNA. Physical models often treat DNA as an elastic rod or beam where three fundamental modes of deformation exist: stretching, bending, and twisting. These deformations can in principle be coupled. Entropically coiled DNA can be straightened by forces below 1 pN and allow one to determine the persistence length 30,31. Higher forces overstretch DNA, causing twist-stretch coupling 32,33, where DNA counterintuitively first slightly overwinds at small forces (<20–30 pN) and unwinds at higher forces. Tension in minicircles is only ~3–5 pN (see simulation in Fig. S10 and Supplementary Note 5), and the influence of twist-stretch coupling on their helical repeat is therefore negligible. Finally, TBC was theoretically predicted three decades ago by Marko and Siggia (MS) 18 as an unwinding of tightly bent DNA.

A direct quantification of as in our experiments is difficult with magnetic torque tweezer (MTT) experiments because these require fragments where and cannot produce tight curvatures in a controllable way. Recent TBC estimates 28,29 predict an insignificant widening of by only 0.2 % at the curvature of the nucleosome (Fig. 3B, red curve; see Suppl. Note 4), which would be practically indetectable. Our data and the magnitude of the relative difference in helical repeat (~10 %), however, is in almost perfect agreement with the predictions from the original MS paper 18 and the extrapolation of the trend from some circularization experiments (Fig. 3B, black datapoints 5–7, discussion in Supplementary Note 4). While the MS equation (Supplementary Note 4, eq. 31) fits excellently to the experimental data in Fig. 3B, the value of the fitted TBC parameters may indicate that additional physics is at play. General stability requirements of the MS model are difficult to satisfy for a linear model when the twist-bend coupling parameter exceeds the torsional stiffness , and non-linearities might have to be introduced (see Supplementary Note 4). In contrast, the TBC parameter estimates from ref. 28,29 satisfy naturally, but the effect on the helical repeat (Fig. 3B, red curve) is irreconcilably weaker than the experimental results suggest.

In a related assay, Du et al. also observed circles with different topoisomers consistent with our data 34, but interpreted them as a species with internal kinks () and one without kinks (). However, generating circles of these lengths with 34 through ligation of nicked circles seems implausible due to the high energetical cost of undertwisting and/or the large stabilization energy required for a kink to make the free energy of the delta TW = −1 state and Delta TW = 0 comparable. Moreover, we performed MD simulations that confirm that nicks are the weakest link in the structure (Fig. S12). We therefore apply the conventional interpretation that two topoisomers are found at 4–8, which requires a changing .

Theoretically, the T4 DNA ligase might also influence the assay results. While of DNA in ligase complexes is not directly significantly changed 35,36, a stabilization of internal defects by ligase was reported 37. On the other hand, a helical repeat of 11–11.3 bp/turn consistent with TBC and our data also appears in ligation-free circularization experiments where j-factor maxima (Fig. 3E in ref. 10) and the uncircularization kinetics 15 are significantly shifted. Different found in other circularization experiments 9,11 can be explained by sticky end geometries and kinks at nicks (15, Supplementary Note 1).

Moreover, the helical repeat is also increased in transcription factors that loop DNA including the lac repressor 38, or araCBAD 39 or in HU protein induced loops 40 . We therefore conclude that a widening of in tightly bent DNA occurs irrespective of ligase.

Conclusions

DNA in biological systems is commonly under high mechanical stress. Around 72% of eukaryotic DNA is nucleosomal DNA with a radius of curvature of ~4.5 nm (Fig. 3C). Our data suggests that DNA with this curvature would be torsionally relaxed at , but instead, nucleosomal DNA is overwound to 17. This results in a (Fig. 3D) or a twist energy of (Supplementary Note 2, eq. 13) in addition to a bending stress (eq. 15). The total mechanical stress in a nucleosome would therefore be , which must be compensated or modulated through noncovalent interactions between the DNA and highly positively charged histone proteins. The increase of aggravates the linking number paradox (36) and the torsional stress will influence DNA wrapping and unwrapping (37) that are necessary for gene regulation and expression.

Our findings also apply to packing of virus capsids, bacterial genomes 41 or transcription factors, or the template length-dependent amplification bias in rolling circle amplification 42. Next, the curvature-dependence of the helical repeat will also have to be considered in the design of DNA nanostructures that contain small minicircles such as DNA catenanes 43, rotaxanes 44, DNA-encircled lipid nanodiscs 45, or for tightly bent DNA origami structures 46,47. Physical models of DNA need to be corrected for tightly bent DNA. Finally, a consequence of TBC is that torque from helicases, polymerases or DNA packing motors will induce bending. We conclude that a changing helical repeat must be considered in all processes where DNA is tightly bent or twisted.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

We thank Dr. Ned Seeman, Dr. Michael Matthies, Dr. Petr Sulc, Dr. Christopher Maffeo, Dr. Aleksei Aksimentiev, Dr. Hamza Balci and Dr. Alexander Vologodskii for helpful discussions.

Funding:

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences through MIRA award #R35GM142706 to TLS, and the National Science Foundation through an EAGER grant #2117998 to TLS.

Footnotes

Competing interests: Authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability:

Raw experimental or simulation data as well as code is available upon request.

References

- (1).Basu A.; Bobrovnikov D. G.; Ha T. DNA Mechanics and Its Biological Impact. J. Mol. Biol. 2021, 433 (6), 166861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Garcia H. G.; Grayson P.; Han L.; Inamdar M.; Kondev J.; Nelson P. C.; Phillips R.; Widom J.; Wiggins P. A. Biological Consequences of Tightly Bent DNA: The Other Life of a Macromolecular Celebrity. Biopolymers 2007, 85 (2), 115–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Shimada J.; Yamakawa H. Ring-Closure Probabilities for Twisted Wormlike Chains. Application to DNA. Macromolecules 1984, 17 (4), 689–698. [Google Scholar]

- (4).Shore D.; Langowski J.; Baldwin R. L. DNA Flexibility Studied by Covalent Closure of Short Fragments into Circles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1981, 78 (8), 4833–4837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Shore D.; Baldwin R. L. Energetics of DNA Twisting: II. Topoisomer Analysis. J. Mol. Biol. 1983, 170 (4), 983–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Horowitz D. S.; Wang J. C. Torsional Rigidity of DNA and Length Dependence of the Free Energy of DNA Supercoiling. J. Mol. Biol. 1984, 173 (1), 75–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Taylor W. H.; Hagerman P. J. Application of the Method of Phage T4 DNA Ligase-Catalyzed Ring-Closure to the Study of DNA Structure: II. NaCl-Dependence of DNA Flexibility and Helical Repeat. J. Mol. Biol. 1990, 212 (2), 363–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Spakowitz A. J. Wormlike Chain Statistics with Twist and Fixed Ends. Europhys. Lett. 2006, 73 (5), 684. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Cloutier T. E.; Widom J. Spontaneous Sharp Bending of Double-Stranded DNA. Mol. Cell 2004, 14 (3), 355–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Vafabakhsh R.; Ha T. Extreme Bendability of DNA Less than 100 Base Pairs Long Revealed by Single-Molecule Cyclization. Science 2012, 337 (6098), 1097–1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Du Q.; Smith C.; Shiffeldrim N.; Vologodskaia M.; Vologodskii A. Cyclization of Short DNA Fragments and Bending Fluctuations of the Double Helix. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2005, 102 (15), 5397–5402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Vologodskii A.; Frank-Kamenetskii D., Strong M. Bending of the DNA Double Helix. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41 (14), 6785–6792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Harrison R. M.; Romano F.; Ouldridge T. E.; Louis A. A.; Doye J. P. K. Identifying Physical Causes of Apparent Enhanced Cyclization of Short DNA Molecules with a Coarse-Grained Model. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2019, 15 (8), 4660–4672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Le T. T.; Kim H. D. Probing the Elastic Limit of DNA Bending. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42 (16), 10786–10794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Jeong J.; Kim H. D. Determinants of Cyclization–Decyclization Kinetics of Short DNA with Sticky Ends. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48 (9), 5147–5156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Wang J. C. Helical Repeat of DNA in Solution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1979, 76 (1), 200–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Hayes J. J.; Tullius T. D.; Wolffe A. P. The Structure of DNA in a Nucleosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1990, 87 (19), 7405–7409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Marko J. F.; Siggia E. D. Bending and Twisting Elasticity of DNA. Macromolecules 1994, 27 (4), 981–988. [Google Scholar]

- (19).Vasudevan D.; Chua E. Y. D.; Davey C. A. Crystal Structures of Nucleosome Core Particles Containing the ‘601’ Strong Positioning Sequence. J. Mol. Biol. 2010, 403 (1), 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Yoo J.; Park S.; Maffeo C.; Ha T.; Aksimentiev A. DNA Sequence and Methylation Prescribe the Inside-out Conformational Dynamics and Bending Energetics of DNA Minicircles. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49 (20), 11459–11475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Kim M.; Bae S.; Oh I.; Yoo J.; Kim J. S. Sequence-Dependent Twist-Bend Coupling in DNA Minicircles. Nanoscale 2021, 13 (47), 20186–20196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Kim M.; Hong C. C.; Lee S.; Kim J. S. Dynamics of a DNA Minicircle: Poloidal Rotation and in-Plane Circular Vibration. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2022, 43 (4), 523–528. [Google Scholar]

- (23).Poppleton E.; Bohlin J.; Matthies M.; Sharma S.; Zhang F.; Šulc P. Design, Optimization and Analysis of Large DNA and RNA Nanostructures through Interactive Visualization, Editing and Molecular Simulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48 (12), e72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Bohlin J.; Matthies M.; Poppleton E.; Procyk J.; Mallya A.; Yan H.; Šulc P. Design and Simulation of DNA, RNA and Hybrid Protein–Nucleic Acid Nanostructures with oxView. Nat. Protoc. 2022, 17 (8), 1762–1788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Sengar A.; Ouldridge T. E.; Henrich O.; Rovigatti L.; Sulc P. A Primer on the oxDNA Model of DNA: When to Use It, How to Simulate It and How to Interpret the Results. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 693710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Snodin B. E. K.; Randisi F.; Mosayebi M.; Šulc P.; Schreck J. S.; Romano F.; Ouldridge T. E.; Tsukanov R.; Nir E.; Louis A. A.; Doye J. P. K. Introducing Improved Structural Properties and Salt Dependence into a Coarse-Grained Model of DNA. J. Chem. Phys. 2015, 142 (23), 234901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Kriegel F.; Matek C.; Dršata T.; Kulenkampff K.; Tschirpke S.; Zacharias M.; Lankaš F.; Lipfert J. The Temperature Dependence of the Helical Twist of DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46 (15), 7998–8009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Skoruppa E.; Laleman M.; Nomidis S. K.; Carlon E. DNA Elasticity from Coarse-Grained Simulations: The Effect of Groove Asymmetry. J. Chem. Phys. 2017, 146 (21), 214902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Nomidis S. K.; Skoruppa E.; Carlon E.; Marko J. F. Twist-Bend Coupling and the Statistical Mechanics of the Twistable Wormlike-Chain Model of DNA: Perturbation Theory and Beyond. Phys. Rev. E 2019, 99 (3), 032414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Smith S.; Finzi L.; Bustamante C. Direct Mechanical Measurements of the Elasticity of Single DNA Molecules by Using Magnetic Beads. Science 1992, 258 (5085), 1122–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Bustamante C.; Marko J. F.; Siggia E. D.; Smith S. Entropic Elasticity of λ-Phage DNA. Science 1994, 265 (5178), 1599–1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Strick T. R.; Allemand J.-F.; Bensimon D.; Bensimon A.; Croquette V. The Elasticity of a Single Supercoiled DNA Molecule. Science 1996, 271 (5257), 1835–1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Gore J.; Bryant Z.; Nöllmann M.; Le M. U.; Cozzarelli N. R.; Bustamante C. DNA Overwinds When Stretched. Nature 2006, 442 (7104), 836–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Du Q.; Kotlyar A.; Vologodskii A. Kinking the Double Helix by Bending Deformation. Nucleic Acids Res 2008, 36 (4), 1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Pascal J. M.; O’Brien P. J.; Tomkinson A. E.; Ellenberger T. Human DNA Ligase I Completely Encircles and Partially Unwinds Nicked DNA. Nature 2004, 432 (7016), 473–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Shi K.; Bohl T. E.; Park J.; Zasada A.; Malik S.; Banerjee S.; Tran V.; Li N.; Yin Z.; Kurniawan F.; Orellana K.; Aihara H. T4 DNA Ligase Structure Reveals a Prototypical ATP-Dependent Ligase with a Unique Mode of Sliding Clamp Interaction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46 (19), 10474–10488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Yuan C.; Lou X. W.; Rhoades E.; Chen H.; Archer L. A. T4 DNA Ligase Is More than an Effective Trap of Cyclized dsDNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35 (16), 5294–5302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Müller J.; Oehler S.; Müller-Hill B. Repression oflacPromoter as a Function of Distance, Phase and Quality of an AuxiliarylacOperator. J. Mol. Biol. 1996, 257 (1), 21–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Lee D. H.; Schleif R. F. In Vivo DNA Loops in araCBAD: Size Limits and Helical Repeat. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1989, 86 (2), 476–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Haykinson M. J.; Johnson R. C. DNA Looping and the Helical Repeat in Vitro and in Vivo: Effect of HU Protein and Enhancer Location on Hin Invertasome Assembly. EMBO J. 1993, 12 (6), 2503–2512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Spakowitz A. J.; Wang Z.-G. DNA Packaging in Bacteriophage: Is Twist Important? Biophys. J. 2005, 88 (6), 3912–3923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Joffroy B.; Uca Y. O.; Prešern D.; Doye J. P. K.; Schmidt T. L. Rolling Circle Amplification Shows a Sinusoidal Template Length-Dependent Amplification Bias. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46 (2), 538–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Schmidt T. L.; Heckel A. Construction of a Structurally Defined Double-Stranded DNA Catenane. Nano Lett. 2011, 11 (4), 1739–1742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Ackermann D.; Schmidt T. L.; Hannam J. S.; Purohit C. S.; Heckel A.; Famulok M. A Double-Stranded DNA Rotaxane. Nat Nanotechnol 2010, 5 (6), 436–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Iric K.; Subramanian M.; Oertel J.; Agarwal N. P.; Matthies M.; Periole X.; Sakmar T. P.; Huber T.; Fahmy K.; Schmidt T. L. DNA-Encircled Lipid Bilayers. Nanoscale 2018, 10 (39), 18463–18467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Dietz H.; Douglas S. M.; Shih W. M. Folding DNA into Twisted and Curved Nanoscale Shapes. Science 2009, 325 (5941), 725–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Han D.; Pal S.; Nangreave J.; Deng Z.; Liu Y.; Yan H. DNA Origami with Complex Curvatures in Three-Dimensional Space. Science 2011, 332 (6027), 342–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Schindelin J.; Arganda-Carreras I.; Frise E.; Kaynig V.; Longair M.; Pietzsch T.; Preibisch S.; Rueden C.; Saalfeld S.; Schmid B.; Tinevez J.-Y.; White D. J.; Hartenstein V.; Eliceiri K.; Tomancak P.; Cardona A. Fiji: An Open-Source Platform for Biological-Image Analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9 (7), 676–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Walther J.; Orozco M. MC_DNA: A Web Server for the Detailed Study of the Structure and Dynamics of DNA and Chromatin Fibers.

- (50).Pérez A.; Marchán I.; Svozil D.; Sponer J.; Cheatham T. E.; Laughton C. A.; Orozco M. Refinement of the AMBER Force Field for Nucleic Acids: Improving the Description of α/γ Conformers. Biophys. J. 2007, 92 (11), 3817–3829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Cornell W. D.; Cieplak P.; Bayly C. I.; Gould I. R.; Merz K. M.; Ferguson D. M.; Spellmeyer D. C.; Fox T.; Caldwell J. W.; Kollman P. A. A Second Generation Force Field for the Simulation of Proteins, Nucleic Acids, and Organic Molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117 (19), 5179–5197. [Google Scholar]

- (52).Yoo J.; Aksimentiev A. Improved Parameterization of Amine–Carboxylate and Amine–Phosphate Interactions for Molecular Dynamics Simulations Using the CHARMM and AMBER Force Fields. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2016, 12 (1), 430–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Yoo J.; Aksimentiev A. New Tricks for Old Dogs: Improving the Accuracy of Biomolecular Force Fields by Pair-Specific Corrections to Non-Bonded Interactions. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20 (13), 8432–8449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Hess B.; Bekker H.; Berendsen H. J.; Fraaije J. G. LINCS: A Linear Constraint Solver for Molecular Simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 1997, 18 (12), 1463–1472. [Google Scholar]

- (55).Darden T.; York D.; Pedersen L. Particle Mesh Ewald: An N Log (N) Method for Ewald Sums in Large Systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98 (12), 10089–10092. [Google Scholar]

- (56).Bussi G.; Donadio D.; Parrinello M. Canonical Sampling through Velocity Rescaling. J. Chem. Phys. 2007, 126 (1). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Parrinello M.; Rahman A. Polymorphic Transitions in Single Crystals: A New Molecular Dynamics Method. J. Appl. Phys. 1981, 52 (12), 7182–7190. [Google Scholar]

- (58).Vologodskii A.; Du Q.; Frank-Kamenetskii M. D. Bending of Short DNA Helices. Artif. DNA PNA XNA 2013, 4 (1), 1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Jacobson H.; Stockmayer W. H. Intramolecular Reaction in Polycondensations. I. The Theory of Linear Systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1950, 18 (12), 1600–1606. [Google Scholar]

- (60).Bates A. D.; Maxwell A. DNA Gyrase Can Supercoil DNA Circles as Small as 174 Base Pairs. EMBO J. 1989, 8 (6), 1861–1866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Nomidis S. K.; Kriegel F.; Vanderlinden W.; Lipfert J.; Carlon E. Twist-Bend Coupling and the Torsional Response of Double-Stranded DNA. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017, 118 (21), 217801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Gao X.; Hong Y.; Ye F.; Inman J. T.; Wang M. D. Torsional Stiffness of Extended and Plectonemic DNA. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2021, 127 (2), 028101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Lipfert J.; Kerssemakers J. W. J.; Jager T.; Dekker N. H. Magnetic Torque Tweezers: Measuring Torsional Stiffness in DNA and RecA-DNA Filaments. Nat. Methods 2010, 7 (12), 977–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Snodin B. E. K.; Romano F.; Rovigatti L.; Ouldridge T. E.; Louis A. A.; Doye J. P. K. Direct Simulation of the Self-Assembly of a Small DNA Origami. ACS Nano 2016, 10 (2), 1724–1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Raw experimental or simulation data as well as code is available upon request.