Abstract

The dinuclear organoplatinum(IV) compound {Pt(CH3)3}2(μ-I)2(μ-adenine) (abbreviated Pt2ad), obtained by treating cubic [Pt(CH3)3(μ3-I)]4 with two equivalents of adenine, was isolated and structurally characterized by single crystal X-ray diffraction. The National Cancer Institute Developmental Therapeutics Program’s in vitro sulforhodamine B assays showed Pt2ad to be particularly cytotoxic against central nervous system cancer cell line SF-539, and human renal carcinoma cell line RXF-393. Furthermore, Pt2ad displayed some degree of cytotoxicity against non-small cell lung cancer (NCI-H522), colon cancer (HCC-2998, HCT-116, HT29, and SW-620), melanoma (LOX-IMVI, MALME-3M, M14, MDA-MB-435, SK-MEL-28, and UACC-62), ovarian cancer (OVCAR-5), renal carcinoma (A498), breast cancer (BT-549 and MDA-MB-468), and triple-negative breast cancer (MDA-MB-231).

Introduction

FDA-approved platinum-based chemotherapy agents such as cisplatin, carboplatin, and oxaliplatin are the clinical first-line standard of care for epithelial ovarian cancer1 and non-small cell lung cancer2,3 and often play significant roles in treating other types of cancer as well.4 The anticancer effectiveness arises from the interaction between the platinum compound and the cancerous DNA5,6 – although alternative mechanisms involving platinum-protein interactions likely contribute to the cytotoxicity as well.7 In order to facilitate the interaction with DNA, some experimental platinum-based anticancer drugs have been fitted with flat, aromatic ancillary ligands capable of engaging in π – π interactions with the nucleobases.8,9,10,11 These π – π interactions drive the intercalation of the platinum compound into the major or minor grooves of the DNA and bring the platinum center within bonding proximity of the nucleobases.

In light of the significance of such π – π interactions, platinum compounds having nucleobase ligands would seem to be ideal anticancer agents, since the nucleobase ligand would naturally intercalate between base pair layers in the DNA. Indeed, various platinum(II) complexes of nucleotides,12 nucleosides,13,14,15 and nucleobase derivatives16 have been reported as highly lethal to different kinds of cancers. Several platinum(II) compounds having adenosine17,18 or an adenine derivative19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30 as an ancillary ligand have also been reported to be highly cytotoxic toward various cancer cell lines. Although several platinum(IV) complexes with adenine derivatives as ligands have been reported,31 we are unaware of any that have been tested as anticancer drugs.

Our research group recently reported the cytotoxicity of octahedral PtIV(CH3)2I2{2,2’-bipyridine} against the human breast cancer cell line ZR-75-1 by the in vitro MTT assay method.32 This compound is easily prepared by treating [Pt(CH3)2I2]x with 2,2’-bipyridine. Indeed, the Lewis acids [Pt(CH3)2X2]x (X = Br, I) and cubic [Pt(CH3)3(μ3-I)]433 can be treated with diverse Lewis base ligands to produce a variety of organoplatinum(IV) derivatives, that could potentially display a broad spectrum of very different anticancer properties. In this work, we report the synthesis, structural characterization, and in vitro anticancer activity of {Pt(CH3)3}2(μ-I)2(μ-adenine), a compound prepared by treating [Pt(CH3)3(μ3-I)]4 with adenine.

Experimental

General Considerations.

All 1H, 13C, and 195Pt NMR spectra were obtained at room temperature on a Bruker Ascend 600 MHz FTNMR spectrometer running Topspin 3.6 at the frequencies 600.16 MHz, 150.91 MHz, and 129.015 MHz, respectively. 1H and 13C chemical shifts are reported in parts per million relative to SiMe4 (δ = 0) and were referenced internally with respect to the protio solvent impurity (δ = 3.31 ppm for HD2COD) or the 13C resonances (δ = 49.15 ppm for CD3OD), respectively. 195Pt NMR spectra were referenced externally to a solution of K2PtCl4 in D2O (δ = − 1620 ppm).34 Infrared spectra were recorded as KBr pellets on a Nicolet Magna-IR 560 spectrometer. Elemental analyses were carried out by Atlantic Microlab, Inc. (Norcross, GA). Unless otherwise noted, all reactions and manipulations were carried out in the presence of air. All reagents and solvents were obtained from commercial suppliers and were used without further purification. [Pt(CH3)3(μ3-I)]4 was prepared by a procedure modified from that by Clark and Manzer.33

Synthesis of [Pt(CH3)3(μ3-I)]4.

A solution consisting of [1,5-cyclooctadiene]Pt(CH3)2 (0.653 g, 1.96 mmol) in CH3I (6 mL) in a glass bomb was stirred magnetically at 70°C for 4.5 hours. The pale yellow homogeneous solution was cooled to room temperature and pale yellow crystals precipitated. Yield = 0.370 g (51%). The crystals were spectroscopically identical to [Pt(CH3)3(μ3-I)]4 and were used without any further purification.

Synthesis of {fac-Pt(CH3)3}2(μ-I)2(μ-adenine).

A mixture of [Pt(CH3)3(μ3-I)]4 (0.311 g, 0.212 mmol) and adenine (0.058 g, 0.429 mmol) in CHCl3CH3OH (1:1 by volume, 10 mL) was stirred at 75°C for 4 hours. The volatile components were removed in vacuo, and the residue was washed with CHCl3 (2 x 5 mL), extracted into CH3OH (10 mL), and crystallized from the CH3OH solution at room temperature as a white powder (yield = 0.135 g). A second batch of the product was crystallized from the CHCl3 washes (yield = 0.156 g). Yield = 0.291 g (79 %). Anal. Calc. for C11H23I2N5Pt2: C, 15.20%; H, 2.67%; N, 8.06%. Found: C, 15.30%; H, 2.86%; N, 7.94%. 1H NMR (CD3OD, δ ppm): 1.396 ppm (s, 6 H, 2JPt-H = 75 Hz), 1.399 ppm (s, 6 H, 2JPt-H = 75 Hz), 1.68 ppm (s, 3 H, 2JPt-H = 74 Hz), 1.76 ppm (s, 3 H, 2JPt-H = 74 Hz), 8.22 ppm (s, 1 H, 3JPt-H = 13 Hz), 8.51 ppm (s, 1 H, 3JPt-H = 10 Hz). 13C{1H} NMR (CD3OD, δ ppm): −8.04 ppm (JPt-C = 659 Hz), −7.16 ppm (1JPt-C = 661 Hz), 10.19 ppm (1JPt-C = 708 Hz), 11.68 ppm (1JPt-C = 718 Hz), 112.4 ppm, 144.0 ppm, 154.3 ppm, 155.8 ppm, 157.0 ppm. 195Pt{1H} NMR (CD3OD, δ ppm): − 2863 ppm, − 2929 ppm. IR (KBr): 3442 (vs), 2963 (m), 2911 (m), 2898 (s), 2853 (m), 2816 (m), 1653 (s), 1560 (m), 1541 (m), 1509 (w), 1507 (w), 1472 (m), 1457 (m), 1397 (m), 1322 (w), 1266 (w), 1224 (m), 1109 (m), 1082 (m), 1028 (w), 911 (w), 789 (m), 732 (m), 668 (m), 611 (s), 560 (s), 467 (m).

X-Ray Diffraction Studies.

Pale yellow plates of {fac-Pt(CH3)3}2(μ-I)2(μ-adenine) were crystallized by the slow addition of CHCl3 (g) to a C2H5OH solution at room temperature. X-ray intensity data were collected using a Bruker D8 Venture diffractometer equipped with a graphite monochromator and a Mo Kα micro-focus INCOATEC Iμs 3.0 sealed tube at 0.71073 Å. Data sets were corrected for Lorentz and polarization effects as well as absorption. The criterion for observed reflections is I > 2σ(I). Lattice parameters were determined from least squares analysis and reflection data. Empirical absorption corrections were applied using SADABS.35 The structure was solved by direct methods and refined by full-matrix least squares analysis on F2 using X-Seed36 equipped with SHELXT.37 All non-hydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically by full-matrix least squares on F2 using the SHELXL38 program. Hydrogen atoms were included in idealized geometric positions with Uiso = 1.2 Ueq of the atom to which they are attached (Uiso = 1.5 Ueq for methyl groups). Those hydrogen atoms attached to nitrogen or oxygen were located in difference maps and assigned 1.2 x Ueq. The frames were integrated with the Bruker SAINT software package using a narrow-frame algorithm. The structure was solved and refined using the Bruker SHELXTL Software Package, and the cell data and refinement parameters are summarized in Table 1. Crystallographic data have been deposited with the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre: the deposition number is CCDC 2298069. These data can be obtained free of charge at https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/ or from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12, Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK; email: deposit@ccdc.cam.ac.uk; fax: +44 (0)1223-336408.

Table 1.

Crystal and intensity collection data for {fac-Pt(CH33}2(μ-1)2(μ-adenine) ·CHCl3 · CH3CH2OH.

| formula | C14H30Cl3I2N5OPt2 |

| molecular weight, g mol−1 | 1034.76 |

| temperature, K | 100.00 |

| wavelength, Å | 0.71073 |

| lattice | triclinic |

| space group | P −1 |

| cell constants | |

| a, Å | 10.1669(9) |

| b, Å | 10.5929(9) |

| c, Å | 13.0266(11) |

| α, deg. | 92.574(3) |

| β, deg. | 109.885(3) |

| γ, deg. | 103.182(4) |

| volume, Å3 | 1272.97(19) |

| Z | 2 |

| ρ (calc.) g cm−3 | 2.700 |

| absorption coefficient, mm−1 | 13.732 |

| F(000) | 940 |

| crystal size, mm3 | 0.337 x 0.189 x 0.066 |

| θ range | 1.992 to 33.778° |

| index ranges | −15 ≤ h ≤ 15 −16 ≤ k ≤ 16 −20 ≤ l ≤ 20 |

| reflections collected | 83,153 |

| independent reflections | 10,210 [Rint = 0.0328] |

| coverage, independent reflections | 100% |

| Absorption correction | Multi-scan |

| max. & min. transmission | 0.7467 and 0.3892 |

| refinement method | Full-matrix least-squares on F2 |

| data/restraints/parameters | 10,210/1/263 |

| goodness-of-fit on F2 | 1.085 |

| Final R indices [I > σ(I)] | R1 = 0.0223 wR2 = 0.0460 |

| R indices (all data) | R1 = 0.0282 wR2 = 0.0475 |

| largest difference peak and hole | 1.413 & – 1.998 e. Å−3 |

In Vitro Sulforhodamine B Assays.

In vitro assays were carried out by staff members in the National Cancer Institute’s Developmental Therapeutics Program.39,40,41 Sixty human tumor cell lines were grown in RPMI 1640 medium containing 5% fetal bovine serum and 2 mM L-glutamine. Cells were inoculated into 96 well microtiter plates in 100 μL at plating densities ranging from 5,000 to 40,000 cells per well, depending on the doubling time of individual cell lines. After cell inoculation, the microtiter plates were incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2, 95% air and 100% relative humidity for 24 hours prior to addition of experimental drugs. After 24 hours, 2 plates of each cell line were fixed in situ with trichloroacetic acid, to represent a measurement of the cell population for each cell line at the time of drug addition (Tz). Pt2ad was solubilized in N,N-dimethylformamide at 400-fold the desired final maximum test concentration and stored frozen prior to use. At the time of drug addition, an aliquot of frozen concentrate was thawed and diluted to twice the desired final maximum test concentration with a complete medium containing 50 μg/mL gentamicin. An additional four, 10-fold or ½ log serial dilutions were made to provide a total of 5 drug concentrations plus control. 100 μL aliquots of these different drug dilutions were added to the appropriate microtiter wells already containing 100 μL of medium, resulting in the required final drug concentrations. Following drug addition, the plates were incubated for an additional 48 hours at 37°C, 5% CO2, 95% air and 100% relative humidity. For adherent cells, the assay was terminated by the addition of cold trichloroacetic acid. Cells were fixed in situ by the gentle addition of 50 μL of cold 50% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid (final concentration, 10% trichloroacetic acid) and incubated for 60 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was discarded, and the plates were washed 5 times with tap water and air-dried. Sulforhodamine B solution (100 μL) at 0.4% (w/v) in 1% acetic acid was added to each well, and plates were incubated for 10 minutes at room temperature. After staining, unbound dye was removed by washing 5 times with 1% acetic acid and the plates were air-dried. Bound stain was subsequently solubilized with 10 mM trizma base, and the absorbance was read on an automated plate reader at wavelength 515 nm. For suspension cells, the methodology was the same, except that the assay was terminated by fixing settled cells at the bottom of the wells by gently adding 50 μL of 80% trichloroacetic acid (final concentration, 16% trichloroacetic acid). Using the 7 absorbance measurements [time zero (Tz), control growth (C), and test growth in the presence of drug at the 5 concentration levels (Ti)], the percentage growth was calculated at each of the drug concentration levels. Calculations were carried out as follows: When Ti ≥ Tz, percentage growth = [(Ti – Tz) (C – Tz)−1)] (100%) When Ti < Tz, percentage growth = [(Ti - Tz) (Tz)−1] (100%)

Three dose response parameters were calculated for each experimental agent. Growth inhibition of 50% (GI50) was calculated from …..

which was the drug concentration resulting in a 50% reduction in the net protein increase (as measured by sulforhodamine B staining) in control cells during the drug incubation. The drug concentration resulting in total growth inhibition (TGI) was calculated from Ti = Tz. The LC50 (concentration of drug resulting in a 50% reduction in the measured protein at the end of the drug treatment as compared to that at the beginning) indicating a net loss of cells following treatment was calculated from ….

Values were calculated for each of these three parameters if the level of activity was reached; however, if the effect were not reached or were exceeded, the value for that parameter was expressed as greater or less than the maximum of minimum concentration tested.

Results and Discussion

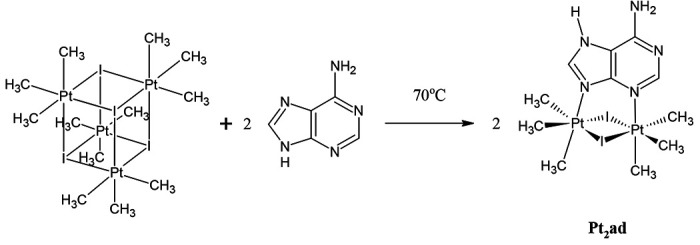

The new compound {fac-Pt(CH3)3}2(μ-I)2(μ-adenine) (abbreviated Pt2ad) was prepared by treating [Pt(CH3)3(μ3-I)]4 with two equivalents of adenine as shown in Figure 1 and isolated as an air-stable crystalline solid. The two platinum atoms in Pt2ad are chemically inequivalent, and so the 195Pt{1H} NMR spectrum features two peaks at δ − 2863 and − 2929 ppm. Four sets of methyl peaks appear with their 195Pt satellites in the 1H NMR spectrum, at δ 1.396 ppm (6H, 2J = 75 Hz), 1.399 ppm (6H, 2J = 75 Hz), 1.68 ppm (3H, 2J = 74 Hz), and 1.76 ppm (3H, 2J = 74 Hz). Likewise, the 13C{1H} NMR spectrum reveals 4 sets of methyl groups with their 195Pt satellites at δ −8.04 ppm (1J = 659 Hz), −7.16 ppm (1J = 661 Hz), 10.19 ppm (1J = 708 Hz), and 11.68 ppm (1J = 718 Hz).

Figure 1.

Synthesis of {fac-Pt(CH3)3}2(μ-I)2(μ-adenine) (Pt2ad).

Pt2ad was structurally characterized by single crystal X-ray diffraction. Figure 2 shows a thermal ellipsoid plot (50% probability) with the non-hydrogen atoms labeled. Table 1 shows the crystal and intensity collection data, while Table 2 shows select metrical data.

Figure 2.

Thermal Ellipsoid Plot (50%) from the X-ray Structure of {fac-Pt(CH3)3}2(μ-I)2(μ-adenine) • CHCl3 • CH3CH2OH.

Table 2.

Select Metrical Data

| Bond | Bond Length (Å) | Bond Angle | Degrees |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pt(1) – N(1) | 2.203(2) | Pt(1) – I(1) – Pt(2) | 87.111(9) |

| Pt(1) – I(1) | 2.7548(3) | N(1) – Pt(1) – I(1) | 89.22(6) |

| Pt(1) – I(2) | 2.8004(3) | N(1) – Pt(1) – I(2) | 87.14(6) |

| Pt(1) – C(6) | 2.064(3) | N(1) – Pt(1) – C(6) | 93.04(10) |

| Pt(1) – C(7) | 2.055(3) | N(1) – Pt(1) – C(7) | 91.37(10) |

| Pt(1) – C(8) | 2.051(3) | N(1) – Pt(1) – C(8) | 178.54(11) |

| Pt(1) ------ Pt(2) | 3.805 | C(6) – Pt(1) – I(1) | 177.73(9) |

| Pt(2) – N(2) | 2.207(2) | C(6) – Pt(1) – I(2) | 91.30(8) |

| Pt(2) – I(1) | 2.7672(3) | C(6) – Pt(1) – C(7) | 89.70(12) |

| Pt(2) – I(2) | 2.7887(3) | I(1) – Pt(1) – I(2) | 88.976(8) |

| Pt(2) – C(10) | 2.054(3) | Pt(2) – I(2) – Pt(1) | 88.966(9) |

| Pt(2) – C(11) | 2.053(3) | N(2) – Pt(2) – I(1) | 89.78(6) |

| Pt(2) – C(9) | 2.050(3) | N(2) – Pt(2) – I(2) | 90.31(6) |

| N(2) – Pt(2) – C(10) | 91.23(10) | ||

| N(2) – Pt(2) – C(11) | 90.09(10) | ||

| N(2) – Pt(2) – C(9) | 176.21(10) | ||

| C(10) – Pt(2) – I(1) | 89.51(9) | ||

| C(10) – Pt(2) – I(2) | 177.83(9) | ||

| C(10) – Pt(2) – C(11) | 91.58(13) | ||

| I(1) – Pt(2) – I(2) | 88.966(9) |

Adenine is known to coordinate to both platinum(II) and platinum(IV) through a variety of diverse coordination modes.31 The particular coordination mode in Pt2ad involves bridging two Pt(IV) centers by a neutral tautomer of adenine, as shown in Figure 2. A similar coordination mode was proposed for {PtIVCl3(H2O)}2(μ-Cl){μ-adenine(−1)} where adenine(−1) is a deprotonated adenine anion, but this compound was not structurally characterized by X-ray crystallography.42

The coordination geometry for each Pt(IV) center in Pt2ad is octahedral. The plane defined by I(1) – Pt(1) – I(2) intersects the plane defined by I(1) – Pt(2) – I(2) at an angle of 32.49°. The 3-center, 4-electron Pt – I bond lengths in Pt2ad are intermediate between the terminal 2-center, 2-electron Pt – I bonds in Pt(CH3)2I2{2,2’-bipyridine} (2.6355(5) and 2.6569(5) Å),32 and the 4-center, 6-electron bonds in cubic [Pt(CH3)3(μ3-I)]4 · ½ CH3I (2.8105(8) to 2.8366(7) Å).43 The Pt – N bond distances in Pt2ad closely resemble those in trinuclear [{PtIV(CH3)3(μ-9-methyladenine(−1))}3] · O=C(CH3)2 (2.18(1) – 2.25(1) Å) and in trinuclear [{PtIV(CH3)3(μ-9-methyladenine(−1))}3] · 1.5 Et2O ·2 H2O (2.180(7) – 2.226(7) Å).44 The Pt(1) ---- Pt(2) distance in Pt2ad (3.805 Å) is within the sum of the van der Waals radii of two platinum atoms,45 suggesting an intramolecular electronic interaction between the two platinum atoms.

The National Cancer Institute’s Developmental Therapeutics Program (NCI/DTP) tested the anticancer activity of Pt2ad against 60 cancer cell lines by the in vitro sulforhodamine B assay. More specifically, there were 6 leukemia, 9 non-small cell lung cancer, 7 colon cancer, 6 central nervous system cancer, 9 melanoma, 7 ovarian cancer, 8 renal cancer, 2 prostate cancer, and 6 breast cancer cell lines. Pt2ad exhibited cytotoxicity toward some cancer cell lines, but not all. The results involving only those cell lines effected by Pt2ad are summarized in Table 3. For comparison, the results involving cisplatin against the same cell lines are also included in Table 3, as values in parentheses.

Table 3.

In Vitro Sulforhodamine B Assay Results for Pt2ad. Values in Parentheses are Results for Cisplatin.

| Type of Cancer | Cell Line | GI50, μM | TGI, μM | LC50, μM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Small Cell Lung | NCI-H522 | 1.51 | 3.70 | 18.6 |

| Colon Cancer | HCC-2998 | 13.1 (10.7) | 31.7 (25.5) | 76.8 (60.8) |

| HCT-116 | 3.43 (9.24) | 15.5 (> 100) | 52.5 (> 100) | |

| HT29 | 5.99 (7.81) | 21.2 (> 100) | 63.6 (> 100) | |

| SW-620 | 3.37 (2.72) | 11.4 (> 100) | 39.2 (> 100) | |

| Central Nervous System | SF-539 | 1.47 (0.600) | 2.76 (7.67) | 5.20 (> 100) |

| Melanoma | LOX IMVI | 3.85 (0.961) | 18.4 (7.93) | 58.2 (> 100) |

| MALME-3M | 1.95 (1.85) | 8.19 (4.58) | 39.2 (> 100) | |

| M14 | 2.08 (1.71) | 14.8 (7.68) | 63.4 (35.1) | |

| MDA-MB-435 | 6.19 (2.77) | 18.4 (14.4) | 46.2 (42.7) | |

| SK-MEL-28 | 5.10 (2.99) | 17.4 (12.8) | 42.4 (99.5) | |

| UACC-62 | 3.18 (1.34) | 15.7 (9.39) | 42.0 (37.2) | |

| Ovarian Cancer | OVCAR-5 | 2.35 (4.38) | 11.9 (46.4) | 35.2 (> 100) |

| Renal Cancer | A498 | 19.7 (12.7) | 37.8 (26.4) | 72.6 (54.9) |

| RXF-393 | ---------- | 2.63 (4.58) | 5.99 (24.2) | |

| Breast Cancer | MDA-MB-231 | 1.62 (28.1) | 8.79 (> 100) | 60.2 (> 100) |

| BT-549 | 3.56 (3.36) | 16.5 (44.9) | 61.2 (> 100) | |

| MDA-MB-468 | 1.49 (0.233) | 3.85 (0.744) | 19.2 (4.50) |

These in vitro cell viability assays clearly underscore the importance of using multiple cell lines of the same type of cancer. For instance, Pt2ad was particularly lethal toward central nervous system (CNS) cancer cell line SF-539 with LC50 = 5.20 μM, but Pt2ad was completely inactive toward five other CNS cancer cell lines (SF-268, SF-295, SNB-19, SNB-75, and U251). For comparison, cisplatin was inactive toward all 6 CNS cancer cell lines. The SF-539 cell line was derived from glioblastoma multiforme cells located in the right, temporoparietal region of the brain of a 34 year-old white female in 1987.46 Glioblastoma multiforme is the deadliest of all brain cancers. Combined with radiotherapy, temozolomide47 is a first-line standard of care chemotherapy drug for treating glioblastoma multiforme, but, interestingly, the NCI/DTP assays showed temozolomide to be completely inactive (LC50 > 100 μM) against the SF-539 cell line. Indeed, the NCI/DTP tests showed temozolomide to be inactive against all 6 CNS cell lines. Thus, Pt2ad is significantly more cytotoxic toward the SF-539 cell line than either cisplatin or temozolomide.

Pt2ad is also more cytostatic than either cisplatin or temozolomide against the CNS SF-539 cancer cells, as seen by comparing the growth inhibition values in Table 3. For the total growth inhibition (TGI), the concentration of Pt2ad need be only 2.76 μM, compared to a required concentration of 7.67 μM for cisplatin. But, for 50% growth inhibition (GI50) of a population of SF-539 cells, a cisplatin solution with a concentration of only 0.600 μM is needed, compared to a 1.47 μM solution of Pt2ad. Interestingly, for temozolomide, GI50 > 100 μM and TGI > 100 μM.

In addition to demonstrating cytotoxicity toward cancer cells in vitro, a good chemotherapy drug for treating glioblastoma multiforme must be able to penetrate the blood-brain barrier. The free web tool Swiss ADME48 predicts that Pt2ad should be able to penetrate the blood-brain barrier, and that the gastrointestinal tract would highly absorb Pt2ad. The Swiss ADME calculation also points out the low water-solubility and the high molar mass of Pt2ad as limitations on the usefulness of this compound as a chemotherapy drug.

Pt2ad was also particularly cytotoxic and cytostatic toward renal cancer cell line RXF-393,49 with LC50 = 5.99 μM and TGI = 2.63 μM. For this same cell line, LC50 = 24.2 μM and TGI = 4.58 μM for cisplatin. Conversely, cisplatin was more cytotoxic and cytostatic than Pt2ad against the renal cancer cell line A498. Though notably less cytotoxic toward the ovarian and breast cancer cell lines, Pt2ad was nonetheless more cytotoxic than cisplatin toward both the ovarian OVCAR-5 cells and the triple-negative breast cancer cells MDA-MB-231.

Conclusions

Pt2ad joins a growing list of organometallic platinum(IV) derivatives that exhibit anticancer properties.32, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55

Pt2ad is more cytotoxic than cisplatin against some cell lines of colon cancer (HCT-116, HT29, and SW-620), the glioblastoma multiforme SF-539 cell line, some melanomas (cell lines LOX IMVI, MALME-3M, and SK-MEL-28), the ovarian cancer cell line OVCAR-5, the renal cancer cell line RXF-393, breast cancer cell line BT-549, and triple-negative breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-231. Nevertheless, there were also some cell lines for which cisplatin was more cytotoxic than Pt2ad, and a number of cell lines against which Pt2ad displayed little to no cytotoxicity at all. When assessing the anticancer properties of a new compound in vitro, using as many different cell lines as possible is necessary in order to gauge the chemotherapeutic potential accurately.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Department of Chemistry & Biochemistry at the University of Alaska Fairbanks (UAF) for financial support of this work. At UAF, the 600 MHz NMR spectrometer was purchased from funding by the US Army Medical Research and Material Command (05178001), and the 300 MHz NMR spectrometer was purchased from funding by the National Science Foundation (DUE–9850731). Undergraduate research support for A. M. O’B. and support for maintaining the 600 MHz NMR spectrometer at UAF were supplied by an Institutional Development Award (IDeA) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under grant number P20GM103395. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the official views of the NIH. A. M. O’B. also acknowledges undergraduate research support from the UAF Office of Undergraduate Research and Scholarly Activity (URSA). UAF is an affirmative action/equal employment opportunity employer and education institution: www.alaska.edu/nondiscrimination.) The National Science Foundation’s Major Research Instrumentation is acknowledged for their support (1827313) in the purchase of the Bruker D8 Venture X-ray diffractometer at Whitworth University. The authors thank the National Cancer Institute Developmental Therapeutics Program (NCI/DTP) and acknowledge NCI/DTP (https://dtp.cancer.gov) as the source of the in vitro sulforhodamine B assay data for Pt2ad (NSC 842139), cisplatin (NSC 119875), and temozolomide (NSC 362856/32).

Contributor Information

Alisha M. O’Brie, Department of Chemistry & Biochemistry, University of Alaska Fairbanks, 1930 Yukon Drive, Fairbanks AK 99775-6160

William A. Howard, Department of Chemistry & Biochemistry, University of Alaska Fairbanks, 1930 Yukon Drive, Fairbanks AK 99775-6160

Kraig A. Wheeler, Department of Chemistry, Whitworth University, Spokane, WA 99251

References

- 1.Richardson D. L., Eskander R. N., O’Malley D. M.. Advances in Ovarian Cancer Care and Unmet Treatment Needs for Patients with Platinum Resistance: A Narrative Review. J. Am. Med. Assoc. Oncol. 9 (2023), 851–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baxevanos P., Mountzios G.. Novel Chemotherapy Regimens for Advanced Lung Cancer: Have We Reached a Plateau? Ann. Transl. Med. 6 (2018), 139–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rossi A., Di Maio M.. Platinum-Based Chemotherapy in Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Optimal Number of Treatment Cycles. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 16 (2016), 653–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rottenberg S., Disler C., Perego P.. The Re-Discovery of Platinum-Based Cancer Therapy. Nature Rev. Cancer 21 (2021), 37–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Basu A., Krishnamurthy S.. Cellular Responses to Cisplatin-Induced DNA Damage. J. Nucleic Acids 2010, 201367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eastman A.. Activation of Programmed Cell Death by Anticancer Agents: Cisplatin as a Model System. Cancer Cells 2 (1990), 275–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casini A., Reedijk J.. Interactions of Anticancer Pt Compounds with Proteins: an Overlooked Topic in Medicinal Inorganic Chemistry? Chem. Sci. 3 (2012), 3135–3144. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zamora A., Wachter E., Vera M., Heidary D. K., Rodríguez V., Ortega E., Fernández-Espín V., Janiak C., Glazer E. C., Barone G., Ruiz J.. Organoplatinum(II) Complexes Self-Assemble and Recognize AT-Rich Duplex DNA Sequences. Inorg. Chem. 60 (2021), 2178–2187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Veclani D., Tolazzi M., Cerón-Carrasco J. P., Melchior A.. Intercalation Ability of Novel Monofunctional Platinum Anticancer Drugs: A Key Step in Their Biological Action. J. Chem. Info. Model. 61 (2021), 4391–4399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang F.-Y., Liu R., Huang K.-B., Feng H.-W., Liu Y.-N., Liang H.. New Platinum(II)-Based DNA Intercalator: Synthesis, Characterization, and Anticancer Activity. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 105 (2019), 182–187. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pages B. J., Garbutcheon-Singh K. B., Aldrich-Wright J. R.. Platinum Intercalators of DNA as Anticancer Agents. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 1613–1624. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tan Y., Xiang D., Pei J., Tan X.. Novel Anti-Tumor Compound and Application Thereof in Preparing Anti-Tumor Drugs. US Patent 2020/0377545 A1, December 3, 2020.

- 13.Leitão M. I. P. S., Orsini G., Murtinheira F., Gomes C. S. B., Herrera F., Petronilho A.. Synthesis, Base Pairing Properties, and Biological Activity Studies of Platinum(II) Complexes Based on Uracil Nucleosides. Inorg. Chem. 62 (2023), 16412–16425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.D’Errico S., Falanga A. P., Greco F., Piccialli G., Oliviero G., Borbone N.. State of Art in the Chemistry of Nucleoside-Based Pt(II) Complexes. Bioorg. Chem. 131 (2023), 106325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Castro F., De Luca E., Girelli C. R., Barca A., Romano A., Migoni D., Verri T., Benedetti M., Fanizzi F. P.. First Evidence for N7-Platinated Guanosine Derivatives Cell Uptake Mediated by Plasma Membrane Transport Processes. J. Inorg. Biochem. 226 (2022), 111660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pullen S., Hiller W. G., Lippert B.. Regarding the Diamagnetic Components in Rosenberg’s “Platinum Pyrimidine Blues”: Species in the Cis-Pt(NH3)2-1-Methyluracil System. Inorg. Chim. Acta 494 (2019), 168–180. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Montagner D., Gandin V., Marzano C., Longato B.. Synthesis, Characterization and Cytotoxic Properties of Platinum(II) Complexes Containing the Nucleosides Adenosine and Cytidine. J. Inorg. Biochem. 105 (2011), 919–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cleare M. J., Hoeschele J. D.. Studies on the Antitumor Activity of Group VIII Transition Metal Complexes. Part I. Platinum(II) Complexes. Bioinorg. Chem. 2 (1973), 187–210. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mueller K., Schütz C., Rüffer T., Bette M., Kaluderović G. N., Steinborn D., Schmidt H.. Synthesis, Characterization, Structures and in vitro Antitumor Activity of Platinum(II) Complexes Bearing Adeninato or Methylated Adeninato Ligands. Inorg. Chim. Acta 507 (2020), 119539. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aseman M. D., Aryamanesh S., Shojaeifard Z., Hemmateenejad B., Nabavizadeh S. M.. Cycloplatinated(II) Derivatives of Mercaptopurine Capable of Binding Interactions with HSA/DNA. Inorg. Chem. 58 (2019), 16154–16170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liskova B., Zerzankova L., Novakova O., Kostrhunova H., Travnicek Z., Brabec V.. Cellular Response to Antitumor cis-Dichlorido Platinum(II) Complexes of CDK Inhibitor Bohemine and Its Analogues. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 25 (2012), 500–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dvořák Z., Štarha P., Trávníček Z.. Evaluation of In Vitro Cytotoxicity of 6-Benzylaminopurine Carboplatin Derivatives against Human Cancer Cell Lines and Primary Human Hepatocytes. Toxicol. In Vitro 25 (2011), 652–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trávníček Z., Štarha P., Popa I., Vrzal R., Dvořák Z.. Roscovitine-Based CDK Inhibitors Acting as N-Donor Ligands in the Platinum(II) Oxalato Complexes: Preparation, Characterization, and In Vitro Cytotoxicity. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 45 (2010), 4609–4614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dvořák L., Popa I., Štarha P., Trávníček Z.. In Vitro Cytotoxic-Active Platinum(II) Complexes Derived from Carboplatin and Involving Purine Derivatives. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 3441–3448. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vrzal R., Štarha P., Dvořák Z., Trávníček Z.. Evaluation of In Vitro Cytotoxicity and Hepatotoxicity of Platinum(II) and Palladium(II) Oxalato Complexes with Adenine Derivatives as Carrier Ligands. J. Inorg. Biochem. 104 (2010), 1130–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Štarha P., Trávníček Z., Popa I.. Platinum(II) Oxalato Complexes with Adenine-Based Carrier Ligands Showing Significant In Vitro Antitumor Activity. J. Inorg. Biochem. 104 (2010), 639–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scűčová L., Trávníček Z., Zatloukal M., Popa I.. Novel Platinum(II) and Palladium(II) Complexes with Cyclin-Dependent Kinase Inhibitors: Synthesis, Characterization and Antitumour Activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 14 (2006), 479–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maloň M., Trávníček Z., Marek R., Strnad M.. Synthesis, Spectral Study and Cytotoxicity of Platinum(II) Complexes with 2,9-Disubstituted-6-Benzylaminopurines. J. Inorg. Biochem 99 (2005), 2127–2138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trávníček Z., Maloň M., Zatloukal M., Doležal K., Strnad M., Marek J.. Mixed Ligand Complexes of Platinum(II) and Palladium(II) with Cytokinin-Derived Compounds Bohemine and Olomoucine: X-Ray Structure of [Pt(BohH+-N7)Cl3] · 9/5 H2O {Boh = 6-(Benzylamino)-2-[(3-Hydroxypropyl)-Amino]-9-Isopropylpurine, Bohemine}. J. Inorg. Biochem. 94 (2003), 307–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baranowska-Kortylewicz J., Pavlik E. J., Smith W. T. Jr., Flanigan R. C., Van Nagell J. R. Jr., Ross D., Kenady D. E.. Inorg. Chim. Acta 108 (1985), 91–98. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Štarha P., Vančo J., Trávníček Z.. Platinum Complexes Containing Adenine-Based Ligands: an Overview of Selected Structural Features. Coord. Chem. Rev. 332 (2017), 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arabi A., Cogley M. O., Fabrizio D., Stitz S., Howard W. A., Wheeler K. A.. Anticancer Activity of Nonpolar Pt(CH3)2I2{bipy} Is Found to be Superior among Four Similar Organoplatinum(IV) Complexes. J. Mol. Struct. 1274 (2023), 134551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clark H. C.; Manzer L. E. Reactions of (π-1,5-Cyclooctadiene)organoplatinum(II) Compounds and the Synthesis of Perfluoroalkylplatinum Complexes. J. Organomet. Chem. 1973, 59, 411–28. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Appleton T. G., Encyclopedia of Spectroscopy and Spectrometry 3rd Ed., 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sheldrick G. M., SADABS and TWINABS – Program for Area Detector Absorption Corrections: University of Göttingen, Göttingen, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barbour L. J., J. Appl. Cryst. 53 (2020), 1141–1146. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sheldrick G. M., Acta Cryst. A 71 (2015), 3–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sheldrick G. M., Acta Cryst. C 71 (2015), 3–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morris J., Kunkel M. W., White S. L., Wishka D. G., Lopez O. D., Bowles L., Brady P. S., Ramsey P., Grams J., Rohrer T., Martin K., Dexheimer T. S., Coussens N. P., Evans D., Risbood P., Sonkin D., Williams J. D., Polley E. C., Collins J. M., Doroshow J. H., Teicher B. A.. Targeted Investigational Oncology Agents in the NCI60: A Phenotypic Systems-Based Resource. Mol Cancer Ther. 22 (2023), 1270–1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shoemaker R. H.. The NCI60 Human Tumor Cell Line Anticancer Drug Screen. Nature Rev. Cancer 6 (2006), 813–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Monks A., Scudiero D., Skehan P., Shoemaker R., Paull K., Vistica D., Hose C., Langley J., Cronise P., Vaigro-Wolff A., Gray-Goodrich M., Campbell H., Mayo J., Boyd M.. Feasibility of a High-Flux Anticancer Drug Screen Using a Diverse Panel of Cultured Human Tumor Cell Lines. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 83 (1991), 757–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Khan B. T., Kumari S. V., Goud G. N.. Complexes of Platinum (II & IV) with Adenine & Guanine. Indian J. Chem. A 21A (1982), 264–267. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ebert K. H., Massa W., Donath H., Lorberth J., Seo B.-S., Herdtweck E.. Organoplatinum Compounds: VI. Trimethylplatinum Thiomethylate and Trimethylplatinum Iodide. The Crystal Structures of [Pt(CH3)3S(CH3)]4 and [Pt(CH3)3I]4 • 0.5 CH3I. J. Organomet. Chem. 559 (1998), 203–207. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhu X., Rusanov E., Kluge R., Schmidt H., Steinborn D.. Synthesis, Characterization, and Structure of [{PtMe3(9-MeA)}3] (9-MeA = 9-Methyladenine): A Cyclic Trimeric Platinum(IV) Complex with a Nucleobase. Inorg. Chem. 41 (2002), 2667–2671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Batsanov S. S.. Van der Waals Radii of Elements. Inorg. Materials 37 (2001), 871–885. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rutka J. T., Giblin J. R., Høifødt H. K., Dougherty D. V., Bell C. W., McCulloch J. R., Davis R. L., Wilson C. B., Rosenblum M. L.. Establishment and Characterization of a Cell Line from a Human Gliosarcoma. Cancer Research 46 (1986), 5893–5902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stupp R., Mason W. P., van den Bent M. J., Weller M., Fisher B., Taphoorn M. J. B., Belanger K., Brandes A. A., Marosi C., Bogdahn U., Curschmann J., Janzer R. C., Ludwin S. K., Gorlia T., Allgeier A., Lacombe D., Cairncross J. G., Eisenhauer E., Mirimanoff R. O.. Radiotherapy Plus Concomitant and Adjuvant Temozolomide for Glioblastoma. New England J. Med. 352 (2005), 987–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Daina A., Michielin O., Zoete V.. SwissADME: a Free Web Tool to Evaluate Pharmacokinetics, Drug-Likeness and Medicinal Chemistry Friendliness of Small Molecules. Sci. Rep. 7 (2017), 42717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.https://www.cellosaurus.org/CVCL_1673 Accessed February, 2024.

- 50.Pouryasin Z., Yousefi R., Nabavizadeh S. M., Rashidi M., Hamidizadeh P., Alavianmehr M.-M., Moosavi-Movahedi A. A.. Anticancer and DNA Binding Activities of Platinum(IV) Complexes: Importance of Leaving Group Departure Rate. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 172 (2014), 2604–2617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Escolà A., Crespo M., López C., Quirante J., Jayaraman A., Polat I. H., Badía J., Baldomà L., Cascante M.. On the Stability and Biological Behavior of Cyclometallated Pt(IV) Complexes with Halido and Aryl Ligands in the Axial Positions. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 24 (2016), 5804–5815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Crespo M.. Cyclometallated Platinum(IV) Compounds as Promising Antitumour Agents. J. Organomet. Chem. 879 (2019), 15–26. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tan M.-X., Wang Z.-F., Qin Q.-P., Huang X.-L., Zou B.-Q., Liang H.. Complexes of Platinum(II/IV) with 2-Phenylpyridine Derivatives as a New Class of Promising Anticancer Agents. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 108 (2019), 107510. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Annunziata A., Amoresano A., Cucciolito M. E., Esposito R., Ferraro G., Iacobucci I., Imbimbo P., Lucignano R., Melchiorre M., Monti M., Scognamiglio C., Tuzi A., Monti D. M., Merlino A., Ruffo F.. Pt(II) Versus Pt(IV) in Carbene Glycoconjugate Antitumor Agents: Minimal Structural Variations and Great Performance Changes. Inorg. Chem. 59 (2020), 4002–4014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bauer E., Domingo X., Balcells C., Polat I. H., Crespo M., Quirante J., Badía J., Baldomà L., Font-Bardia M., Cascante M.. Synthesis, Characterization and Biological Activity of New Cyclometallated Platinum(IV) Iodido Complexes. Dalton Trans. 46 (2017), 14973–14987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.