Abstract

The accumulation in infected cells of large amounts of unspliced viral RNA for use as mRNA and genomic RNA is a hallmark of retrovirus replication. The negative regulator of splicing (NRS) is a long cis-acting RNA element in Rous sarcoma virus that contributes to unspliced RNA accumulation through splicing inhibition. One of two critical sequences located in the NRS 3′ region resembles a minor class 5′ splice site and is required for U11 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein (snRNP) binding to the NRS. The second is a purine-rich region in the 5′ half that interacts with the splicing factor SF2/ASF. In this study we investigated the possibility that this purine-rich region provides an RNA splicing enhancer function required for splicing inhibition. In vitro, the NRS acted as a potent, orientation-dependent enhancer of Drosophila doublesex pre-mRNA splicing, and enhancer activity mapped to the purine-rich domain. Analysis of a number of site-directed and deletion mutants indicated that enhancer activity was diffusely located throughout a 60-nucleotide area but only the activity associated with a short region previously shown to bind SF2/ASF correlated with efficient splicing inhibition. The significance of the enhancer activity to splicing inhibition was demonstrated by using chimeras in which two authentic enhancers (ASLV and FP) were substituted for the native NRS purine region. In each case, splicing inhibition in transfected cells was restored to levels approaching that observed for the NRS. The observation that a nonfunctional version of the FP enhancer (FPD) that does not bind SF2/ASF also fails to block splicing when paired with the NRS 3′ region supports the notion that SF2/ASF binding to the NRS is relevant, but other SR proteins may substitute if an appropriate binding site is supplied. Our results are consistent with a role for the purine region in facilitated snRNP binding to the NRS via SF2/ASF.

Retrovirus replication requires a substantial level of unspliced RNA for structural-protein production and for use as genomes in progeny virions (4). The unspliced RNA also serves as a substrate for RNA splicing in the nucleus to produce subgenomic RNAs such as env, the mRNA encoding the envelope protein. Efficient replication requires a precise balance between the unspliced and spliced RNA, which in the simple virus Rous sarcoma virus (RSV) is approximately 80% unspliced RNA. The RNA ratio is not influenced by viral proteins but, rather, results from the interaction of the host splicing machinery with regulatory or control elements within the viral RNA. A number of cis elements within the RSV primary transcripts contribute to the observed unspliced-to-spliced-RNA ratio, and two of these are represented by the env and src 3′ splice sites themselves, which have either a suboptimal branch point sequence (12, 22) or a pyrimidine tract (58). Mutation of these sequences toward the consensus splicing signals results in an oversplicing phenotype and a replication defect that is probably due to a shortage of unspliced RNA. When the mutant virus harbored an improved branch point at the env 3′ splice site, continued passage of infected cultures resulted in the appearance of replication-competent revertants with either a restored suboptimal branch or, surprisingly, small deletions downstream of the 3′ splice site in env exon sequences (22). The level of env 3′ splice site use is therefore controlled in part negatively by the suboptimal splicing signals and by a positive-acting element located nearby in the env exon that was subsequently shown to be an RNA splicing enhancer (see below).

In addition to suboptimal 3′ splice sites, RSV harbors two other negative elements that are not integral to the splice sites but still serve to repress splicing. Located close to the src 3′ splice site, the suppressor of src splicing is a largely uncharacterized element whose deletion results in an increase in splicing to src, but not env, and which also has a mild negative effect on the splicing of a heterologous intron (2, 32). A second element that globally controls splicing to both RSV 3′ splice sites, the negative regulator of splicing (NRS), has been extensively studied.

The NRS is located in gag approximately 300 nucleotides (nt) downstream of the 5′ splice site and more than 4,000 nt from the env 3′ splice site (1, 33). Deletions and mutations of the NRS result in an oversplicing phenotype, and the NRS can potently inhibit the splicing of heterologous introns in vivo and in vitro (1, 14, 33, 44). The NRS was minimally localized to a 227-nt BstNI fragment from the gag gene (nt 703 to 930) that is operationally divided into 5′ (NRS5′, nt 703 to 797) and 3′ (NRS3′, nt 798 to 930) halves that are themselves completely nonfunctional (33). The 5′ region is purine rich (73%), whereas the 3′ half is pyrimidine rich and contains a region similar to a 3′ splice site. While the element serves to block splicing, the presence of 5′ and 3′ splice site-like sequences suggested that it may represent a decoy (33) for binding of U1 and/or U2 small nuclear ribonucleoproteins (snRNPs), components of the spliceosome that recognize 5′ and 3′ splice sites, respectively (35). Binding of U1, U2, and, unexpectedly, the lower-abundance U11 snRNP was subsequently confirmed by in vitro binding assays (14). However, the functional significance of U1 and U2 snRNP binding has not been demonstrated, and the 3′ splice site sequence in the downstream region is not critical for activity. In contrast, Gontarek et al. (14) demonstrated an important role for U11 snRNP, since its interaction with the NRS was dependent on a critical sequence at the 3′ end whose mutation abolished both binding in vitro and splicing inhibition in vivo. Recent studies demonstrated that U11 snRNP replaces U1 snRNP in a spliceosome that removes a minor class of introns that contain highly conserved, noncanonical splice sites with AT-AC termini (variously called AT-AC, minor, or U12-dependent introns) (15, 25, 49; reviewed in references 36 and 50). However, naturally occurring introns with GT-AG termini but otherwise conforming to the minor consensus were recently reported and shown to be spliced by the minor pathway (7). The 5′ splice site consensus sequence is thus /RTATCCTY (the slash indicates the splice site). Significantly, the NRS sequence required for the U11 interaction exactly matches the minor-class 5′ splice site consensus sequence, with a G at intron position 1 (Fig. 1). Thus, the contribution of the NRS 3′ half to splicing inhibition may reflect solely U11 snRNP binding.

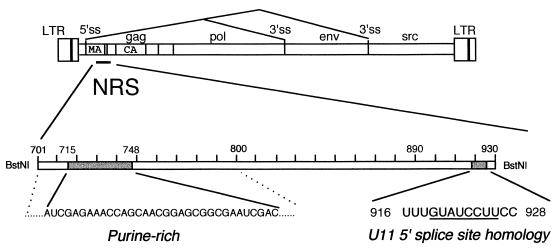

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of the RSV genome and significant sequences within the NRS. Shown for RSV (not to scale) are the long terminal repeats (LTR), 5′ and alternative 3′ splice sites, and gag, pol, env, and src genes. The location of the NRS relative to the matrix (MA) and capsid (CA) genes is also indicated. Below is a scaled-up enlargement of the minimal NRS (a BstNI fragment), showing the 5′ purine-rich region (between dotted lines) and the critical sequence (shaded region, nt 715 to 748) that is required for SF2/ASF binding and splicing inhibition. Also shown at the 3′ end (shaded) is the sequence that resembles the minor-class intron 5′ splice site consensus (underlined). Naturally occurring minor introns with G rather than A at the first position have recently been described, making the NRS sequence a perfect match to the consensus. Mutations in this sequence that abolish U11 snRNP binding also abrogate NRS splicing inhibition.

As noted above, the isolated NRS 3′ half is not functional, and inhibitory activity requires the 5′ region. Deletion of just the purine region from RSV results in an oversplicing phenotype (1). Furthermore, a partial deletion (nt 735 to 776) in a recombinant virus impairs NRS activity and results in rapid-onset lymphomas in infected birds, which highlights the biological relevance of the purine region (41). Few clues to the function of the 5′ region were initially obvious from its sequence, which is unremarkable except for being purine rich. Recent work aimed at identifying NRS binding proteins showed that a number of SR protein-splicing factors interact with the NRS, with SF2/ASF predominating, and that binding was localized to the 5′ half independent of the 3′ sequences (31). The failure of purified or bacterially expressed SF2/ASF to bind NRS mutants that lack the purine region established a correlation between binding and NRS activity (31). The SR proteins have been extensively studied and possess a number of activities important for splicing (reviewed in references 11, 30, and 52). This includes mediating the activity of purine-rich exonic RNA splicing enhancers (ESEs), elements found in a growing number of cellular (3, 8, 17, 19, 20, 27, 38, 48, 51, 54, 55) and viral (13, 22, 40, 42, 59) genes that serve to enhance splicing of introns with weak splice sites (reviewed in reference 18). The SF2/ASF binding site in the NRS was mapped to a 30-nt region in the 5′ half with similarity to SF2/ASF binding sites in purine-rich ESEs (21, 29, 37, 40, 43, 45, 47). Furthermore, as demonstrated for the FP and avian sarcoma/leukosis virus (ASLV) enhancers (43), the isolated NRS purine region assembles into a large complex in vitro (5) and assembly of the NRS complex requires SF2/ASF (6). Thus, NRS5′ has features in common with purine-rich splicing enhancers.

The observations that the 5′ half of the NRS is generally purine rich, harbors sequences similar to SF2/ASF binding sites in other systems, and binds purified and recombinant SF2/ASF raised the possibility that this region harbors splicing enhancer activity and that this property is important for NRS splicing inhibition. Indeed, we show here that the NRS 5′ region strongly stimulated the in vitro splicing of a Drosophila dsx RNA that lacks its resident enhancer. While enhancer activity was diffusely located throughout the NRS5′, only sequences that have been shown to bind SF2/ASF both activated dsx splicing in vitro and contributed to splicing inhibition of a heterologous intron in vivo. The ability of authentic enhancers from the bovine growth hormone gene and ASLV to substitute for the NRS 5′ sequences to reconstitute splicing inhibition in vivo supports the hypothesis that the enhancer activity associated with the NRS 5′ region is relevant to function. These data support a model in which SR proteins bound to the purine-rich region facilitate snRNP binding to the NRS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid constructions.

In vitro enhancer activity was assessed with pDsx and pDsx-ASLV plasmids (43), generously supplied by Robin Reed (Harvard Medical School, Boston, Mass.). RSV DNA fragments were from the Prague C strain (34), and the sequence numbering was that of Schwartz et al. (39). To facilitate the cloning of NRS fragments in each orientation into pDsx (51) and the myc intron of pRSVNeo-int (28), a 246-bp NRS fragment (nt 701 to 932) with KpnI and XbaI sites appended to the 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively, was produced by PCR (Perkin-Elmer) (primer sequences available upon request). This fragment was cloned into the blunt-ended BamHI site located downstream of the dsx sequences in pDsx, and plasmids with each orientation of the NRS were isolated. The KpnI and XbaI sites in the upstream vector sequence of pDsx were first removed by digestion with SphI-StyI, blunt ending, and recircularization. Thus, the sites introduced with the NRS were unique and subsequent PCR fragments containing appended KpnI and XbaI sites could be easily shuttled into the pDsx-NRS vectors in each orientation. A similar directional KpnI-XbaI cloning approach was developed for pRSVNeo-int by inserting the same 246-bp NRS PCR product into the BstXI or SacII sites in the myc intron; the sites are unique in this vector. Control experiments showed that the introduced restriction sites in both constructs and the modification of the dsx vector had no influence on enhancer or NRS activity (data not shown).

Additional NRS PCR fragments harboring KpnI and XbaI sites were NRS5′ (nt 701 to 797), NRS3′ (nt 798 to 932), and Δ748 (nt 748 to 932). The linker scan series (LS1 to LS10) and mutants mtm3, Δ720–744, and Δ747–777 (sequences presented in Table 1) were made by site-directed mutagenesis (U.S.E. kit; Pharmacia Biotech) of a vector containing RSV nt 704 to 1011 (p3ZMSΔRI). PCR was then used to produce the NRS (nt 701 to 932) or NRS5′ (nt 701 to 797) for cloning into the pDsx BamHI site or the pRSVNeo-int BstXI intron site, as indicated in the figure legends. The sequences of all PCR products were verified by DNA sequencing with a Sequenase v2.0 kit (Amersham Life Science).

TABLE 1.

Sequence of the purine-rich region and activities of the NRS mutants

| Mutant | Sequencea

|

Activityb

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 711720730740750760770780 | Enh | NRS (%) | |

| NRS | AGTGCATCGAGAAACCAGCAACGGAGCGGCGAATCGACAAAGGGGAGGAAGTGGGAGAAACAACTGTGCAGCGAG | + | 54 |

| mtm3 | AGTGCATCGTGTTTCCTGCTTCGGTGCGTCGTTTCGACAAAGGGGAGGAAGTGGGAGAAACAACTGTGCAGCGAG | + | 41 |

| Δ748 | --------------------------------------AAAGGGGAGGAAGTGGGAGAAACAACTGTGCAGCGAG | + | 21 |

| Δ720-44 | AGTGCATCG-------------------------CGACAAAGGGGAGGAAGTGGGAGAAACAACTGTGCAGCGAG | + | 36 |

| Δ747-77 | AGTGCATCGAGAAACCAGCAACGGAGCGGCGAATCG-------------------------------GCAGCGAG | + | 51 |

The A-to-T mutations in the mtm3 mutant are underlined. Dashes represent sequence deletions. The RSV sequence coordinates are shown above the sequences.

Chimeric NRS elements were made in a longer NRS context (nt 701 to 1011) and placed in the SacII site in the pRSVNeo-int myc intron. The FP element was obtained as a 115-nt FspI-PvuII fragment from pSVBa/B3 (16), and 35 nt of the ASLV enhancer were contained in a 108-bp XhoI-BglII fragment from pASLV (43) that also had an extensive multicloning site sequence. These were inserted in each orientation by blunt-end ligation into the SacII site. Each orientation of NRS5′ and a longer NRS3′ fragment (nt 797 to 1011) was obtained in the pRSVNeo-int SacII site by KpnI-XbaI shuttling. Chimeras were made by digesting the construct harboring NRS3′ with the upstream enzyme KpnI, repairing the ends, and introducing each orientation of FP, ASLV, and NRS5′ and the sense orientation of FPD by blunt-end ligation. FPD was a 135-bp SmaI-EcoRI fragment from pSVBa/B3ΔFP (16). Thus, while there were a number of deleted and inserted nucleotides as a result of the cloning method, the net difference in size between the chimeric (NRS5′/NRS3′) and authentic NRS was only 2 nt.

In vitro splicing reactions.

All dsx DNAs were linearized with MluI, and labeled transcripts were generated in vitro in a capping reaction with T7 RNA polymerase and [32P]UTP as described previously (31). All RNAs were gel purified before use, and splicing reactions were performed with extract from Promega (Madison, Wis.) under reaction conditions recommended by the supplier. The reaction products were phenol extracted, precipitated with ethanol, subjected to electrophoresis in a denaturing 4% polyacrylamide gel, and visualized by autoradiography.

Transfection of 293 cells and RNase protection assays.

293 cells were grown in minimal essential medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and penicillin-streptomycin. Cells grown to about 40 to 60% confluence in 6-cm dishes were transfected with 2 to 3 μg of DNA by the calcium phosphate method (Pharmacia), and total RNA harvested 40 h later was isolated on Qiagen RNAeasy columns as specified by the manufacturer. RNase protection assays were carried out as described previously (33) with 5 μg of RNA. A probe to analyze the splicing of RNA derived from the pRSVNeo-int vectors was made by inserting a 602-bp blunted NcoI-BstXI fragment that spans the myc 5′ splice site into the end-repaired HincII sites of pGEM-3Z. A 655-nt riboprobe was made by T7 transcription of a HindIII-linearized vector, and protected bands for unspliced and spliced RNA are 602 and 440 nt. Quantitation was done with a Molecular Dynamics Storm 860 PhosphorImager.

RESULTS

RNA splicing enhancer activity associated with the 5′ half of the NRS.

We used an in vitro approach to determine if the NRS harbors splicing enhancer activity and, if so, if that activity is associated with the purine-rich 5′ region of the NRS. This was accomplished with a construct derived from the Drosophila dsx gene, whose final intron contains a suboptimal 3′ splice site and is spliced only in the presence of its resident regulated splicing enhancer or enhancers from other sources (51). The NRS (nt 701 to 932) or its 5′ (nt 701 to 797) and 3′ (nt 798 to 932) halves were inserted downstream of the dsx-regulated exon in a construct lacking an enhancer (Fig. 2A). The antisense orientations of each fragment served as negative controls, and a construct containing the ASLV enhancer served as a positive control. Radiolabeled RNA produced in vitro was then added to a splicing-reaction mixture containing HeLa nuclear extract, and the extent of splicing was assessed after the recovered RNAs were subjected to denaturing gel electrophoresis and autoradiography.

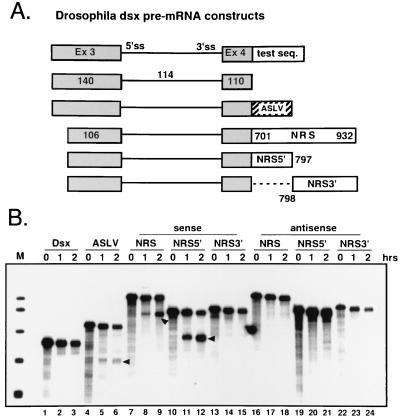

FIG. 2.

The NRS purine-rich region has RNA splicing enhancer activity in vitro. (A) Schematic representation of the Drosophila doublesex (dsx) pre-mRNAs used in the in vitro assay for splicing-enhancer activity. The lengths of the dsx exons (in shaded boxes) and intron (thin line) and the 5′ and 3′ splice sites (5′ss and 3′ss) are indicated. The 3′ splice site of the dsx third intron is weak, and an enhancer in the downstream exon is required for removal of the upstream intron. RNAs lacking an enhancer fail to splice. The NRS and its 5′ and 3′ halves (NRS5′ and NRS3′) are shown as open boxes (coordinates are shown) and were inserted in both orientations downstream of the truncated dsx exon 4 in the identical position to the ASLV enhancer (hatched box), which served as a positive control. The NRS constructs lack 34 nt of upstream polylinker sequence, and the inserts are flanked by KpnI and XbaI sites that facilitated cloning. Control experiments showed that these modifications had no influence on splicing efficiency (results not shown). (B) Enhancer activity of NRS fragments. The indicated 32P-labeled transcripts were spliced in vitro in HeLa nuclear extract for 1 and 2 h, as indicated above the lanes. The extracted RNA was subjected to electrophoresis in a 4% denaturing polyacrylamide gel followed by autoradiography. The spliced products are indicated by the solid arrowheads. The mobilities of the substrates and products varied due to the different sizes of the inserts. M, end-labeled pBR322 MspI fragments, which served as markers.

Consistent with other studies (43, 48, 51, 56, 60), dsx RNA lacking an enhancer did not splice (Fig. 2B, lanes 1 to 3) whereas a small amount of splicing was detected when the positive control ASLV enhancer was present (lanes 4 to 6). Significantly more splicing was observed when the NRS was inserted into the dsx construct in the sense orientation (lanes 7 to 9) but not when it was inserted in the antisense orientation (lanes 16 to 18). When the halves of the NRS were tested, it was found that the 5′ half (NRS5′) promoted efficient splicing even at 1 h and that more than 50% of the RNA was spliced at 2 h (lanes 10 to 12). Again, the antisense construct was largely inactive (lanes 19 to 21), although a trace amount of spliced product was seen in other experiments. In contrast, little enhancer activity was observed with either orientation of the NRS 3′ half (NRS3′; lanes 13 to 15 and 22 to 24), although in other experiments a low level of splicing was detected with the sense construct. These results indicate that in the dsx context and under these conditions, strong splicing-enhancer activity is associated with NRS5′. This strength may reflect the presence of a high-affinity site(s) for a single factor or a synergistic effect of several different elements and binding factors.

Enhancer activity is diffusely located throughout NRS5′.

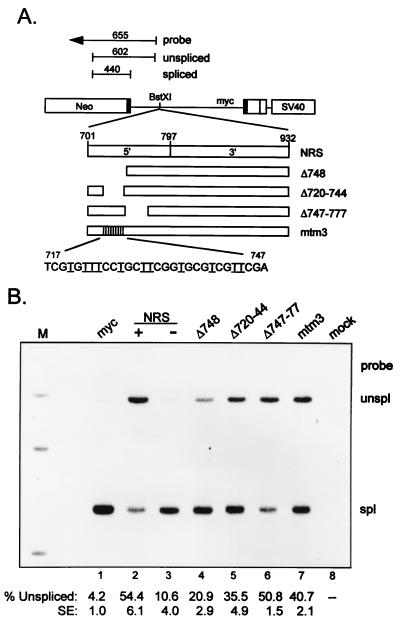

A number of mutants were used in an attempt to define the NRS5′ sequence(s) responsible for the enhancer activity and to determine if they corresponded to those previously shown to be critical for NRS activity and SF2/ASF binding (nt 715 to 748) (31). The sequences of the purine-rich region and some of the mutants are presented in Table 1. Initially, nine linker-scanning (LS) mutations from nt 718 to 777 were tested in the NRS5′ context for enhancer activity by using the dsx in vitro splicing assay described above. The effect of the LS mutants on in vivo splicing inhibition was also examined after the mutations were built back into the complete NRS and inserted 162 nt downstream of the 5′ splice site in the myc intron of a construct used previously to assess NRS activity (33) (the assay is described in Fig. 3). However, none of these mutations had any effect on in vitro enhancer activity or in vivo NRS activity (data not shown), indicating that the relevant sequence(s) for enhancement and splicing inhibition was either unaffected by the six base changes introduced in the LS mutants or redundant within NRS5′. The former possibility was addressed by using a mutant (mtm3) containing 11 A-to-T changes from nt 720 to 743, intended to decrease the purine content within the region required for SF2/ASF binding and NRS activity. A similar strategy was used to inactivate the immunoglobulin M splicing enhancer (48). Surprisingly, these changes also had no effect on in vitro enhancer activity (Table 1) but did decrease splicing inhibition in vivo relative to the wild-type NRS (Fig. 3, compare lane 7 with lane 2), although the decrease was not as dramatic as when this region was deleted (Δ748) (lane 4) (33). This suggested that either the sequences required for enhancer and splicing inhibition activity were independent, the mutations created a new enhancer that did not support NRS splicing inhibition, or the downstream region from nt 744 to 785 also contained enhancer sequences. This was addressed by using NRS5′ deletions in the SF2/ASF binding region (Δ720–744) or in the downstream area (Δ747–777). As expected, Δ720–744 was impaired for splicing inhibition whereas Δ747–777 had only a minor effect on NRS function (Fig. 3, lanes 5 and 6), but neither mutation reduced enhancer activity (Table 1). We conclude that the sequences in NRS5′that are required for SF2/ASF binding and splicing inhibition (nt 720 to 744) can also function in vitro as a splicing enhancer but that enhancer activity is located diffusely throughout the 5′ half of the NRS, including sequences that make only a minor contribution to splicing inhibition. Thus, enhancer activity is a feature of NRS5′, but not all sequences with enhancer activity may support splicing inhibition.

FIG. 3.

Effect of mutations in the NRS 5′ region on in vivo splicing inhibition. (A) Schematic representation of the pRSVNeo-int expression vector and RNase protection probe used to assess NRS splicing inhibition. Shown for pRSVNeo-int are the Neo gene (open boxes), myc exon sequences (solid boxes), the simian virus 40 (SV40) region (open box), and introns (thin lines). Inserted into the BstXI intron site 163 nt downstream of the myc 5′ splice site were the NRS, a mutant with deletions to nt 748 (Δ748), derivatives lacking nts 720 to 744 (Δ720–744) or nt 747 to 777 (Δ747–777), or a site-directed mutant containing 11 A-to-T changes between nt 720 and 743 (mtm3). Relevant NRS coordinates are shown, and vertical lines indicate point mutations. The sequence of mtm3 is shown with the A-to-T changes underlined. A construct containing the NRS in the antisense orientation was used as a negative control. Shown above the constructs is a diagram of the RNase protection probe that spans the myc 5′ splice site. Protected fragments corresponding to unspliced (602-nt) and spliced (440-nt) RNA are shown. The diagram is not to scale. (B) Results of an RNase protection assay. Constructs containing the NRS fragments indicated at the top were transfected into 293 cells, total RNA was harvested 48 h later and analyzed by RNase protection, protected fragments were extracted and run on a 4% denaturing polyacrylamide gel, and autoradiography was performed. The sense (+) and antisense (−) orientations of the NRS controls are indicated. myc, analysis of RNA from constructs containing no insert; mock, analysis of RNA from mock-transfected cells. Bands corresponding to probe and unspliced and spliced RNA are indicated. The average percent unspliced RNA of three independent experiments, as quantitated by PhosphorImager analysis, is shown below each lane. The standard error is also indicated (SE).

Functional substitution of NRS5′ by two authentic splicing enhancers.

If the observed splicing-enhancer activity of NRS5′ is related to its role in splicing inhibition, one would predict that authentic splicing enhancers should functionally replace NRS5′ and restore splicing inhibition when combined with the 3′ half of the NRS. To test this prediction, the constructs shown in Fig. 4A, in which the entire 5′ portion of the NRS was replaced with sense and antisense NRS5′ (as positive and negative controls) or each orientation of the ASLV or FP enhancers (FP enhancer is from the bovine growth hormone gene [8]), were made. Splicing inhibition activity was then assessed in transfected 293 cells. These enhancers were chosen because the FP enhancer, like NRS5′, binds SF2/ASF (45) whereas the ASLV enhancer binds SRp40 preferentially and binds only a low level of SF2/ASF (43). Thus, if NRS activity is restricted to SF2/ASF binding, FP might be expected to replace NRS5′ whereas ASLV would not. In this regard, it was recently shown that assembly of the NRS complex in vitro was supported by SF2/ASF but not by SC35 or SRp40 (6). The NRS context in these experiments was an ∼300-nt fragment that is more active than the minimal fragment used in the experiment in Fig. 3 (33). Additional negative controls were the sense orientation of a nonfunctional FP enhancer (FPD) that fails to bind SF2/ASF (45) coupled to NRS3′ and each orientation of FP, ASLV, NRS5′, and NRS3′ alone. These permutations were embedded in pRSVNeo-int at a SacII site positioned 340 nt downstream of the myc intron 5′ splice site. This distance from the 5′ splice site is similar to the native location of the NRS purine region in RSV, about 315 nt. The constructs were transfected into 293 cells, and total RNA was subjected to RNase protection analysis to assess unspliced and spliced RNA levels (Fig. 4A). The results of a representative experiment are shown in Fig. 4B, and a quantitative analysis of three independent experiments is presented in Fig. 4C.

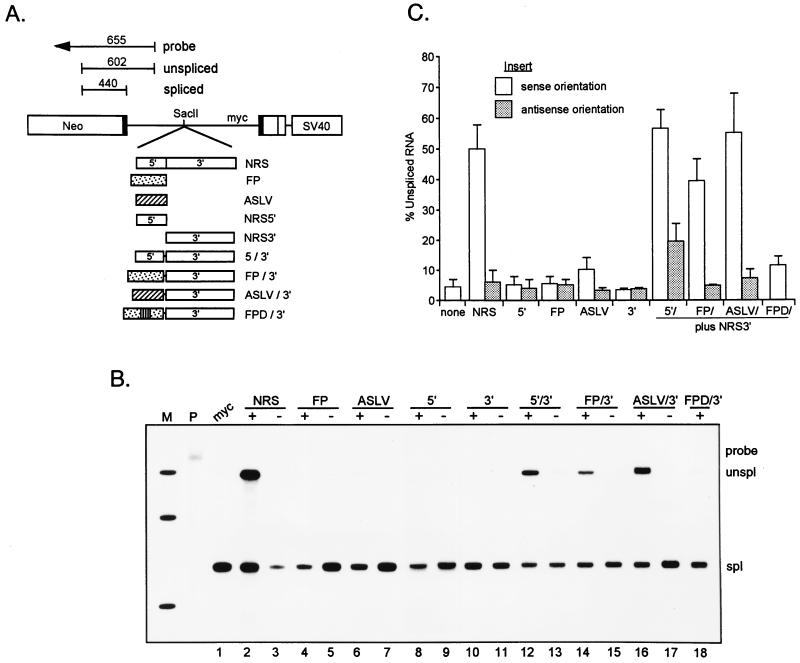

FIG. 4.

Bovine growth hormone and ASLV purine-rich splicing enhancers substitute for NRS5′ to reconstitute NRS activity. (A) Schematic representation of the expression vectors used to transfect 293 cells for RNase protection assays. The sizes of the probe and protected fragments are indicated. Fragments to be tested for splicing inhibition were inserted into the SacII intron site ∼340 nt downstream of the myc 5′ splice site in pRSVNeo-int. Fragments inserted in each orientation (not indicated) are the NRS (open boxes with the 5′ and 3′ regions separated by a vertical line), the bovine growth hormone FP enhancer (stippled box), the ASLV enhancer (hatched box), and NRS5′ and NRS3′ (appropriately sized open boxes). In the chimeric constructs, NRS5′ was deleted from the sense-oriented NRS and replaced with each orientation of NRS5′, FP, ASLV, or the sense version of an inactivated FP enhancer (FPD; stippled box with vertical lines). The diagram is not to scale. (B) Results of an RNase protection assay. Constructs were transfected into 293 cells, and total RNA was analyzed by RNase protection as in Fig. 5. myc, RNA containing no insert (lane 1). In lanes 2 through 11, the sense (+) and antisense (−) orientations of the entire fragment are indicated. In lanes 12 through 18, + and − refer to the orientation of the fragments inserted upstream of NRS3′, which is in the sense orientation. The positions of probe and unspliced and spliced protected fragments are indicated. M, labeled MspII fragments of pBR322; P, unprocessed probe. (C) Quantitation of unspliced RNA levels determined by PhosphorImager analysis. The data are the averages of three independent experiments.

Consistent with previous studies (14, 33), NRS activity was reflected as a dramatic increase in unspliced RNA relative to the level seen with the parent construct (Fig. 4B, lane 1) when the sense but not the antisense NRS was placed in the intron (lanes 2 and 3). No inhibitory activity was seen when either orientation of NRS5′ or NRS3′ was introduced (lanes 8 to 11). The FP and ASLV enhancers alone were also unable to block splicing at this position (lanes 4 to 7, but see Discussion). As expected, reintroduction of NRS5′ upstream of NRS3′ so as to produce only a few nucleotide differences from the native NRS resulted in a wild-type level of unspliced RNA, and the effect was restricted largely to the sense orientation (lanes 12 and 13). The low but reproducible inhibition observed when the incorrect orientation of NRS5′ was fused to NRS3′ may be attributable to the low level of in vitro splicing-enhancer activity that was occasionally observed with antisense NRS5′. Significantly, the sense orientation of the FP enhancer, when coupled to NRS3′, resulted in unspliced RNA levels that were comparable to those seen with the NRS and NRS5′/3′ (compare lane 14 to lanes 2 and 12); antisense FP did not result in splicing inhibition when paired with NRS3′ (lane 13), which ruled out spacing effects as the source of unspliced RNA accumulation. An equally important result was that FPD, the nonfunctional derivative of FP that does not bind SF2/ASF, failed to reconstitute NRS activity when coupled to NRS3′ (lane 18). These results show that the entire 5′ half of the NRS can be functionally replaced by a splicing enhancer that shares the feature of SF2/ASF binding and that the SF2/ASF binding site is critical for the effect. Surprisingly, the ASLV enhancer reconstituted NRS activity in the sense but not the antisense orientation as efficiently as FP and NRS5′ despite its reported weak binding of SF2/ASF (lanes 16 and 17). This result suggests that SR proteins other than SF2/ASF may collaborate with NRS3′ to bring about splicing inhibition if an appropriate binding site is provided. It is likely that the ASLV enhancer serves this purpose for SRp40. Collectively, these observations indicate that NRS5′ plays a role similar to that of splicing enhancers, i.e., SR protein binding, and that this, in concert with NRS3′, serves to bring about splicing inhibition.

DISCUSSION

Viruses serve as attractive models to study splicing regulation since they often exploit the host cell splicing machinery in unusual ways. This is true of retroviruses, which must control splicing to accumulate large pools of completely unspliced RNA but also exhibit remarkably complex splicing patterns, as seen in human immunodeficiency virus (4). In RSV, a number of cis elements cooperate to preserve up to 80% of the primary transcripts as unspliced RNA. Efforts to understand one of them, the NRS, have suggested a novel mechanism involving two important cis sequences and the binding of SF2/ASF and U11 snRNP that has not been described in other systems (31). How the two cis sequences and the identified trans factors that are normally required for splicing conspire to elicit splicing inhibition is unknown. In this study, we have investigated the role of the NRS 5′ region in splicing inhibition.

The majority of enhancers described thus far are purine rich and many bind SF2/ASF (13, 21, 29, 37, 40, 43, 45, 47, 60). Because the NRS shares these features, we asked if its purine-rich region possessed enhancer activity. Indeed, the full-length NRS was an active enhancer of dsx pre-mRNA splicing and NRS5′ was consistently much better, even more potent than the control ASLV enhancer, which is considered to be quite strong. While the basis for this difference is unknown, the 5′ and 3′ regions have the potential to form significant secondary structure (33), and this might reduce the binding efficiency of enhancer factors to the full-length NRS in vitro. Interestingly, SF2/ASF does bind NRS5′ more efficiently than it binds the full-length NRS (31). Alternatively, with the full-length construct, enhancer factors bound to the 5′ region might interact with and be preoccupied by factors bound to NRS3′ (e.g., U11 or U1 snRNP), which might make them unavailable for interactions that result in enhancement of the dsx 3′ splice site. This is supported by the in vitro formation of a large RNP complex on the NRS (the NRS complex) but not on NRS3′ alone (5).

The results of the localization experiments revealed that enhancer activity is present throughout NRS5′ (nt 701 to 798). This finding does not perfectly correlate with NRS splicing inhibition activity, which is confined largely to nt 703 to 748. Previous studies showed that nt 703 to 748 are very important for splicing inhibition and SF2/ASF binding but that nt 747 to 777 contribute only marginally to inhibitory activity and fail to bind SF2/ASF (33). Because nt 747 to 777 harbored enhancer activity but were suboptimal for splicing inhibition, we conclude that whatever factors mediate the enhancer activity do not efficiently support splicing inhibition in conjunction with the NRS 3′ sequences. That factor would appear to be SF2/ASF for nt 720 to 744 but not for nt 747 to 777, since an NRS fragment with deletions to nt 748 lost the ability to bind SF2/ASF and other SR proteins (31). Further support for a primary role for SF2/ASF derives from the observation that SF2/ASF, but not SC35 or SRp40, supports assembly of the NRS complex in vitro (6). The factor(s) responsible for the 747 to 777 enhancer activity have not been identified but clearly play a minor role in splicing inhibition.

Given that the NRS ultimately elicits splicing inhibition, the significance of the enhancer activity associated with NRS5′ was assessed in vivo with a series of chimeric NRS elements. We reasoned that if NRS5′ served as an enhancer, enhancers from other sources might functionally replace NRS5′ and restore splicing inhibition when combined with the NRS 3′ region. Implicit was the expectation that SF2/ASF binding would be important. The results were remarkably clear that the bovine growth hormone FP enhancer could replace NRS5′ and that the effect was related to SF2/ASF binding. Equally impressive was the level of inhibition brought about by the ASLV/NRS3′ chimera, but this was somewhat surprising since it was reported that ASLV binds primarily SRp40 and only minor levels of SF2/ASF (43). Also, the finding that only SF2/ASF can support NRS complex assembly suggested that SR proteins are not interchangeable for NRS function (6). One interpretation of the positive result with the ASLV/NRS3′ chimera is that low-level binding of SF2/ASF to ASLV is sufficient to potentiate NRS3′ for inhibition. It is more likely that the NRS lacks high-affinity binding sites for other SR proteins whereas the ASLV enhancer contributes to splicing inhibition by supplying a binding site for SRp40. The identification by systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (SELEX) of high-affinity binding sites for SF2/ASF, SC35, and SRp40 (46, 47) may allow definitive resolution of this question. Regardless of the proteins involved, the results provide strong evidence that the enhancer function of NRS5′ is important for NRS-mediated splicing inhibition.

It is somewhat paradoxical that an element with splicing-enhancer activity should be involved in splicing repression. How might an enhancer element contribute to splicing inhibition? Some insight into this was revealed with the identification of a purine-rich intronic repressor element (3RE) that is juxtaposed upstream of an alternative 3′ splice site in the adenovirus gene IIIa (21). It was shown that SF2/ASF actually decreased IIIa splicing in vitro by binding 3RE and blocking U2 snRNP entry into the spliceosome. In turn, splicing inhibition was reproduced when 3RE was replaced by consensus SF2/ASF binding sites, and 3RE functioned as an enhancer when located in the downstream exon. This is a precedent for the potential, at least in vitro, for enhancers to sterically block splicing when located close to the branch point. The NRS is distinguished from 3RE in that the distances over which the NRS works (several hundred nucleotides) are not compatible with a steric mechanism. Also, the NRS has been placed 169 nt upstream or 29 nt downstream of a 3′ splice site in vivo, and no splicing inhibition was observed (33). Further, while the NRS blocked the splicing of adenovirus pre-mRNA in vitro, U2 snRNP was present in aberrantly large splicing complexes that formed (14). We note that the insertion site in the chimeric NRS experiments (Fig. 4) was 337 nt from the myc 5′ splice site (SacII site), analogous to the NRS position in RSV, and that no inhibition occurred with the enhancers or NRS5′ alone. In other experiments, the enhancers alone, but not NRS5′, caused substantial accumulation of unspliced RNA when inserted 162 nt from the 5′ splice site (BstXI, 805 nt from the 3′ splice site). Still, some cooperation between the enhancers and NRS3′ was evident at the BstXI site, since there was an even larger increase in unspliced RNA accumulation when the two were combined (data not shown). This result indicates that some enhancers may block splicing from an intron position in vivo when located quite far from the branch point. In addition, some differences exist between NRS5′ and the enhancers used here in that insertion of NRS5′ at the proximal site did not influence unspliced RNA levels. We have not yet investigated how FP and ASLV contribute to unspliced RNA accumulation in this system. Clearly, the complete NRS is not simply an enhancer, since splicing inhibition requires the contribution of the 3′ half at all sites tested and thus reflects a role for U11 and/or other snRNPs.

Two of the proposed functions of SR proteins are to facilitate U1 snRNP binding to 5′ splice sites (24, 57, 62) and to stabilize interactions at 3′ splice sites when bound to enhancers (53, 61). The requirement of the purine region for NRS-mediated splicing inhibition suggests a collaboration with factors bound to the downstream region. While enhancers are generally thought to work on upstream 3′ splice sites, a long ESE in a caldesmon exon was shown to stimulate 5′ splice site use in the upstream direction (19), as was an enhancer in an influenza virus M2 gene exon (40). More recently, the cardiac troponin T (cTNT) enhancer (54) was shown to promote downstream 5′ splice site use in the caldesmon gene (9). How this directionality is achieved is unknown, but it may be that NRS5′ activity is more like the cTNT enhancer and specifies downstream interactions in NRS3′.

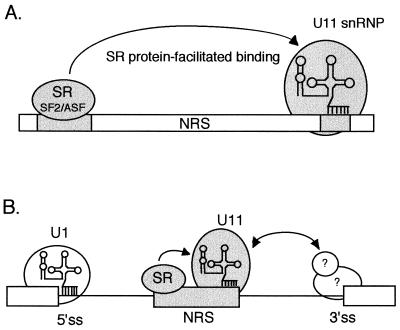

As has been suggested, an enhancer might be thought of simply as a binding site(s) for SR proteins that function to recruit the splicing machinery to weak splice sites (18), and its position and context within an RNA may determine enhancing or repressing activities. With this view in mind, a model for the role of the NRS purine region is shown in Fig. 5A. We envision that SR proteins bound to NRS5′ promote the downstream binding of U11 snRNP, in essence “enhancing” a U11 snRNP interaction with the minor-class 5′ splice site-like sequence located in NRS3′. It should be noted that the importance of U1 snRNP binding has not been excluded (see Introduction), and it is equally possible that U1 binding is also facilitated by the purine region. This model may be overly simplistic in that preliminary experiments to directly demonstrate this effect in vitro have revealed only a modest influence of the purine region on U11 binding (31a). To account for the splicing inhibition activity of the NRS, we propose that the NRS is recognized primarily as a minor-class 5′ splice site that effectively competes with the authentic 5′ splice site and associates with the authentic 3′ splice site in an inactive splicing complex (Fig. 5B). A recent finding that an authentic AT-AC 5′ splice site from the human P120 gene can block the major splicing pathway, but only when a purine-rich sequence was supplied, supports the idea that the NRS is recognized as a minor-class 5′ splice site (31b). A study by Kohrman et al. (23) concluded that major and minor splice sites are not catalytically compatible but did not address the possibility that an interaction occurs. In general, the proximal of two competing 5′ splice sites is selected for pairing with a 3′ splice site (10, 26) and the positioning of the NRS relative to the authentic 5′ splice site is a critical component of the model. In fact, the NRS does not function when placed outside of a test intron (33). Given that U1 snRNP has been estimated to be 100-fold more abundant than U11 snRNP, the purine-rich region and SR protein binding may serve to improve the efficiency of U11 recruitment to the NRS and increase the competitiveness of the putative minor-class 5′ splice site for interaction with the 3′ splice site. How this interaction might occur is the subject of ongoing investigations in our laboratory.

FIG. 5.

Model for the function of the purine-rich region and NRS splicing inhibition. (A) SR proteins (SF2/ASF) bound to the purine-rich region are proposed to facilitate the binding of U11 snRNP to the putative minor-class 5′ splice site at the 3′ end of the NRS. U11 snRNA base pairing to the NRS is represented by the vertical lines. (B) U11 snRNP associated with the NRS, which is in a proximal position relative to the authentic 5′ splice site (5′ss), is proposed to interact with factors associated with the major class 3′ splice site (3′ss), perhaps similarly to the way in which normal intron bridging interactions occur. Since splicing between major and minor class splice sites is not thought to occur (23), these interactions would elicit splicing inhibition by sequestering the 3′ splice site and preventing its pairing with the authentic 5′ splice site. U1 snRNP is shown base paired to the 5′ splice site. The hypothetical 3′ splice site-interacting factors are indicated with question marks.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Robin Reed for the Dsx and pASLV plasmids, Fritz Rottman for bovine growth hormone plasmids, and Craig Cook for helpful comments on the manuscript. Some of oligonucleotides were synthesized by the Protein/Nucleic Acid Shared Facility of the Medical College of Wisconsin.

This work was supported by NIH grant R29CA63348 to M.T.M.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arrigo S, Beemon K. Regulation of Rous sarcoma virus RNA splicing and stability. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:4858–4867. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.11.4858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berberich S L, Stoltzfus C M. Mutations in the regions of the Rous sarcoma virus 3′ splice sites: implications for regulation of alternative splicing. J Virol. 1991;65:2640–2646. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.5.2640-2646.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caputi M, Casari G, Guenzi S, Tagliabue R, Sidoli A, Melo C A, Baralle F E. A novel bipartite splicing enhancer modulates the differential processing of the human fibronectin EDA exon. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:1018–1022. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.6.1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coffin J M. Retroviridae: the viruses and their replication. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Fields virology. New York, N.Y: Raven Press; 1996. pp. 1767–1847. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cook C R, McNally M T. Characterization of an RNP complex that assembles on the Rous sarcoma virus negative regulator of splicing element. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:4962–4968. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.24.4962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cook C R, McNally M T. SR protein and snRNP requirements for assembly of the Rous sarcoma virus negative regulator of splicing complex in vitro. Virology. 1998;242:211–220. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dietrich R C, Incorvaia R, Padgett R A. Terminal intron dinucleotide sequences do not distinguish between U2- and U12-dependent introns. Mol Cell. 1997;1:151–160. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dirksen W P, Hampson R K, Sun Q, Rottman F M. A purine-rich exon sequence enhances alternative splicing of bovine growth hormone pre-mRNA. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:6431–6436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elrick L L, Humphrey M B, Cooper T A, Berget S M. A short sequence within two purine-rich enhancers determines 5′ splice site specificity. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:343–352. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.1.343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eperon I C, Ireland D C, Smith R A, Mayeda A, Krainer A R. Pathways for selection of 5′ splice sites by U1 snRNPs and SF2/ASF. EMBO J. 1993;12:3607–3617. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06034.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fu X D. The superfamily of arginine/serine-rich splicing factors. RNA. 1995;1:663–680. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fu X D, Katz R A, Skalka A M, Maniatis T. The role of branchpoint and 3′-exon sequences in the control of balanced splicing of avian retrovirus RNA. Genes Dev. 1991;5:211–220. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.2.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gontarek R R, Derse D. Interactions among SR proteins, an exonic splicing enhancer, and a lentivirus Rev protein regulate alternative splicing. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:2325–2331. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.5.2325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gontarek R R, McNally M T, Beemon K. Mutation of an RSV intronic element abolishes both U11/U12 snRNP binding and negative regulation of splicing. Genes Dev. 1993;7:1926–1936. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.10.1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hall S L, Padgett R A. Conserved sequences in a class of rare eukaryotic nuclear introns with non-consensus splice sites. J Mol Biol. 1994;239:357–365. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hampson R K, La Follette L, Rottman F M. Alternative processing of bovine growth hormone mRNA is influenced by downstream exon sequences. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:1604–1610. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.4.1604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heinrichs V, Baker B S. The Drosophila SR protein RBP1 contributes to the regulation of doublesex alternative splicing by recognizing RBP1 RNA target sequences. EMBO J. 1995;14:3987–4000. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00070.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hertel K J, Lynch K W, Maniatis T. Common themes in the function of transcription and splicing enhancers. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:350–357. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Humphrey M B, Bryan J, Cooper T A, Berget S M. A 32-nucleotide exon-splicing enhancer regulates usage of competing 5′ splice sites in a differential internal exon. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:3979–3988. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.8.3979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hwang D Y, Cohen J B. A splicing enhancer in the 3′-terminal c-H-ras exon influences mRNA abundance and transforming activity. J Virol. 1997;71:6416–6426. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.6416-6426.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kanopka A, Muhlemann O, Akusjarvi G. Inhibition by SR proteins of splicing of a regulated adenovirus pre-mRNA. Nature. 1996;381:535–538. doi: 10.1038/381535a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katz R A, Skalka A M. Control of retroviral RNA splicing through maintenance of suboptimal processing signals. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:696–704. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.2.696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kohrman D C, Harris J B, Meisler M H. Mutation detection in the med and medJ alleles of the sodium channel Scn8a. Unusual splicing due to a minor class AT-AC intron. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:17576–17581. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.29.17576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kohtz J D, Jamison S F, Will C L, Zuo P, Luhrmann R, Garcia-Blanco M A, Manley J L. Protein-protein interactions and 5′-splice-site recognition in mammalian mRNA precursors. Nature. 1994;368:119–124. doi: 10.1038/368119a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kolossova I, Padgett R A. U11 snRNA interacts in vivo with the 5′ splice site of U12-dependent (AU-AC) pre-mRNA introns. RNA. 1997;3:227–233. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krainer A R, Conway G C, Kozak D. The essential pre-mRNA splicing factor SF2 influences 5′ splice site selection by activating proximal sites. Cell. 1990;62:35–42. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90237-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lavigueur A, La Branche H, Kornblihtt A R, Chabot B. A splicing enhancer in the human fibronectin alternate ED1 exon interacts with SR proteins and stimulates U2 snRNP binding. Genes Dev. 1993;7:2405–2417. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.12a.2405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Linial M. Creation of a processed pseudogene by retroviral infection. Cell. 1987;49:93–102. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90759-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lynch K W, Maniatis T. Synergistic interactions between two distinct elements of a regulated splicing enhancer. Genes Dev. 1995;9:284–293. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.3.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Manley J L, Tacke R. SR proteins and splicing control. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1569–1579. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.13.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McNally L M, McNally M T. SR protein splicing factors interact with the Rous sarcoma virus negative regulator of splicing element. J Virol. 1996;70:1163–1172. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.2.1163-1172.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31a.McNally, L. M., and M. T. McNally. Unpublished data.

- 31b.McNally, M. T. Unpublished data.

- 32.McNally M T, Beemon K. Intronic sequences and 3′ splice sites control Rous sarcoma virus RNA splicing. J Virol. 1992;66:6–11. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.1.6-11.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McNally M T, Gontarek R R, Beemon K. Characterization of Rous sarcoma virus intronic sequences that negatively regulate splicing. Virology. 1991;185:99–108. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90758-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meric C, Spahr P F. Rous sarcoma virus nucleic acid-binding protein p12 is necessary for viral 70S RNA dimer formation and packaging. J Virol. 1986;60:450–459. doi: 10.1128/jvi.60.2.450-459.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moore M J, Query C C, Sharp P A. Splicing of precursors to mRNA by the spliceosome. In: Gesteland R, Atkins J, editors. The RNA world. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1993. pp. 303–357. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nilsen T W. A parallel spliceosome. Science. 1996;273:1813. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5283.1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ramchatesingh J, Zahler A M, Neugebauer K M, Roth M B, Cooper T A. A subset of SR proteins activates splicing of the cardiac troponin T alternative exon by direct interactions with an exonic enhancer. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:4898–4907. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.9.4898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Santisteban I, Arredondo-Vega F X, Kelly S, Loubser M, Meydan N, Roifman C, Howell P L, Bowen T, Weinberg K I, Schroeder M L, et al. Three new adenosine deaminase mutations that define a splicing enhancer and cause severe and partial phenotypes: implications for evolution of a CpG hotspot and expression of a transduced ADA cDNA. Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4:2081–2087. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.11.2081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schwartz D E, Tizard R, Gilbert W. Nucleotide sequence of Rous sarcoma virus. Cell. 1983;32:853–869. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90071-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shih S R, Krug R M. Novel exploitation of a nuclear function by influenza virus: the cellular SF2/ASF splicing factor controls the amount of the essential viral M2 ion channel protein in infected cells. EMBO J. 1996;15:5415–5427. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith M R, Smith R E, Dunkel I, Hou V, Beemon K L, Hayward W S. Genetic determinant of rapid-onset B-cell lymphoma by avian leukosis virus. J Virol. 1997;71:6534–6540. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.6534-6540.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Staffa A, Cochrane A. Identification of positive and negative splicing regulatory elements within the terminal tat-rev exon of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:4597–4605. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.8.4597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Staknis D, Reed R. SR proteins promote the first specific recognition of pre-mRNA and are present together with the U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particle in a general splicing enhancer complex. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:7670–7682. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.11.7670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stoltzfus C M, Fogarty S J. Multiple regions in the Rous sarcoma virus src gene intron act in cis to affect the accumulation of unspliced RNA. J Virol. 1989;63:1669–1676. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.4.1669-1676.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sun Q, Mayeda A, Hampson R K, Krainer A R, Rottman F M. General splicing factor SF2/ASF promotes alternative splicing by binding to an exonic splicing enhancer. Genes Dev. 1993;7:2598–2608. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.12b.2598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tacke R, Chen Y, Manley J L. Sequence-specific RNA binding by an SR protein requires RS domain phosphorylation: creation of an SRp40-specific splicing enhancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:1148–1153. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tacke R, Manley J L. The human splicing factors ASF/SF2 and SC35 possess distinct, functionally significant RNA binding specificities. EMBO J. 1995;14:3540–3551. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07360.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tanaka K, Watakabe A, Shimura Y. Polypurine sequences within a downstream exon function as a splicing enhancer. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:1347–1354. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.2.1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tarn W Y, Steitz J A. A novel spliceosome containing U11, U12, and U5 snRNPs excises a minor class (AT-AC) intron in vitro. Cell. 1996;84:801–811. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81057-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tarn W Y, Steitz J A. Pre-mRNA splicing: the discovery of a new spliceosome doubles the challenge. Trends Biochem Sci. 1997;22:132–137. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tian M, Maniatis T. A splicing enhancer complex controls alternative splicing of doublesex pre-mRNA. Cell. 1993;74:105–114. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90298-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Valcarcel J, Green M R. The SR protein family: pleiotropic functions in pre-mRNA splicing. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:296–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang Z, Hoffmann H M, Grabowski P J. Intrinsic U2AF binding is modulated by exon enhancer signals in parallel with changes in splicing activity. RNA. 1995;1:21–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xu R, Teng J, Cooper T A. The cardiac troponin T alternative exon contains a novel purine-rich positive splicing element. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:3660–3674. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.6.3660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yeakley J M, Hedjran F, Morfin J P, Merillat N, Rosenfeld M G, Emeson R B. Control of calcitonin/calcitonin gene-related peptide pre-mRNA processing by constitutive intron and exon elements. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:5999–6011. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.10.5999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yeakley J M, Morfin J P, Rosenfeld M G, Fu X D. A complex of nuclear proteins mediates SR protein binding to a purine-rich splicing enhancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7582–7587. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zahler A M, Roth M B. Distinct functions of SR proteins in recruitment of U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein to alternative 5′ splice sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:2642–2646. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.2642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang L, Stoltzfus C M. A suboptimal src 3′ splice site is necessary for efficient replication of Rous sarcoma virus. Virology. 1995;206:1099–1107. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zheng Z-M, He P-J, Baker C C. Selection of the bovine papillomavirus type 1 nucleotide 3225 3′ splice site is regulated through an exonic splicing enhancer and its juxtaposed exonic splicing suppressor. J Virol. 1996;70:4691–4699. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.7.4691-4699.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zheng Z-M, He P-J, Baker C C. Structural, functional, and protein binding analyses of bovine papillomavirus type 1 exonic splicing enhancers. J Virol. 1997;71:9096–9107. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9096-9107.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zuo P, Maniatis T. The splicing factor U2AF35 mediates critical protein-protein interactions in constitutive and enhancer-dependent splicing. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1356–1368. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.11.1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zuo P, Manley J L. The human splicing factor ASF/SF2 can specifically recognize pre-mRNA 5′ splice sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:3363–3367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.8.3363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]