Abstract

Lathyrane-type diterpenes have a wide range of biological activities. Among them, euphoboetirane A (1) exerts neurogenesis-promoting activity. In order to increase the structural diversity of this type of lathyrane and explore its potential use in neurodegenerative disorders, the biotransformation of 1 by Streptomyces puniceus BC-5GB.11 has been investigated. The strain BC-5GB.11, isolated from surface sediments collected from the intertidal zone of the inner Bay of Cadiz, was identified as Streptomyces puniceus, as determined by phylogenetic analysis using 16S rRNA gene sequence. Biotransformation of 1 by BC-5GB.11 afforded five products (3–7), all of which were reported here for the first time. The main biotransformation pathways involved regioselective oxidation at non-activated carbons (3–5) and isomerization of the ∆12,13 double bond (6). In addition, a cyclopropane-rearranged compound was found (7). The structures of all compounds were elucidated on the basis of extensive NMR and HRESIMS spectroscopic studies.

Keywords: marine-derived actynomicete, Streptomyces, diterpenoids, lathyranes, biotransformation

1. Introduction

Lathyranes are polyoxygenated macrocyclic diterpenoids with a 5/11/3-fused-ring skeleton that are widely distributed in plants from the genera Euphorbia and Jatropha [1,2,3,4,5]. They stand out for their high structural diversity as well as for the variety of biological activities that they display [6]. A great number of lathyrane diterpenoids have shown the capability to modulate MDR, cytotoxicity against cancer cell lines, anti-inflammatory activity, and the ability to induce cell proliferation or differentiation of neural stem cells (NSC) [6]. Some structural features, such as a fused epoxy ring, the gem-dimethylcyclopropane ring, the oxidation degree, and the nature of the ester chains attached to the main skeleton, could be involved in the substrate-target biological interactions.

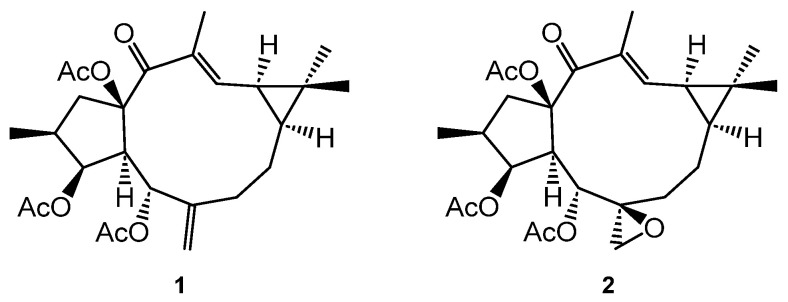

In previous studies, we have described that the lathyranes euphoboetirane A (1) and epoxyboetirane A (2) (Figure 1), isolated from Euphorbia boetica, increased the size of neurospheres in a dose-dependent manner in cultures stimulated with a combination of two growth factors, epidermal (EGF) and basic fibroblast (bFGF), in a synergist way. The results suggested that they act on receptors different from epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) or fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) [7]. On the other hand, it has been proven that lathyrane compounds can exert significantly different abilities to activate PKCs and promote NPC proliferation or differentiation [8,9] without knowing what the precise structural factors that determine the type of activity presented by these compounds are. Therefore, there is an interest in lathyrane-based library preparation with high structural diversity to explore its potential use in neurodegenerative disorders.

Figure 1.

Lathyranes euphoboetirane A (1) and epoxyboetirane A (2).

Microbial transformation is a really useful alternative to chemical approaches for performing highly regio- and stereoselective hydroxylations at non-activated carbons and rearrangement reactions [10,11,12,13]. To the best of our knowledge, only two precedents for the biotransformation of lathyrane diterpenoids have been described. Wu et al. reported the microbial transformation of three lathyrane diterpenoids (lathyrol, 7β-hydroxylathyrol, and Euphorbia factor L3) by Mortierella ramanniana CGMCC 3.03413, Mucor circinelloides CICC 40242, and Nocardia iowensis sp. nov. NRRL 5646. Eight new metabolites were obtained as a result of the regioselective hydroxylation at C-7, C-8, C-18, or C-19 positions, together with two 10,11-secolathyranes [11]. Recently, Euphorbia factor L1 and its deacylated derivative were biotransformed in their deoxy derivatives by Mucor polymorphosporus and Cunninghamella elegans [14]. Moreover, euphorbiasteroid was glycosylated, regioselectively hydroxylated, or methyl oxidized by another C. elegans strain, bio-110930 [15].

This paper reports on the isolation and identification of a Streptomyces puniceus strain isolated from sediment samples from the intertidal zone of the inner Bay of Cadiz (Cádiz, Spain). In order to broaden the structural diversity of lathyrane diterpenoids and further study the relationship between the functionalization presented by these diterpenes and their neurogenesis-promoting activity, we also described the biotransformation of euphoboetirane A (1), a lathyrane-type diterpenoid isolated from E. boetica by Streptomyces puniceus BC-5GB.11.

2. Results and Discussion

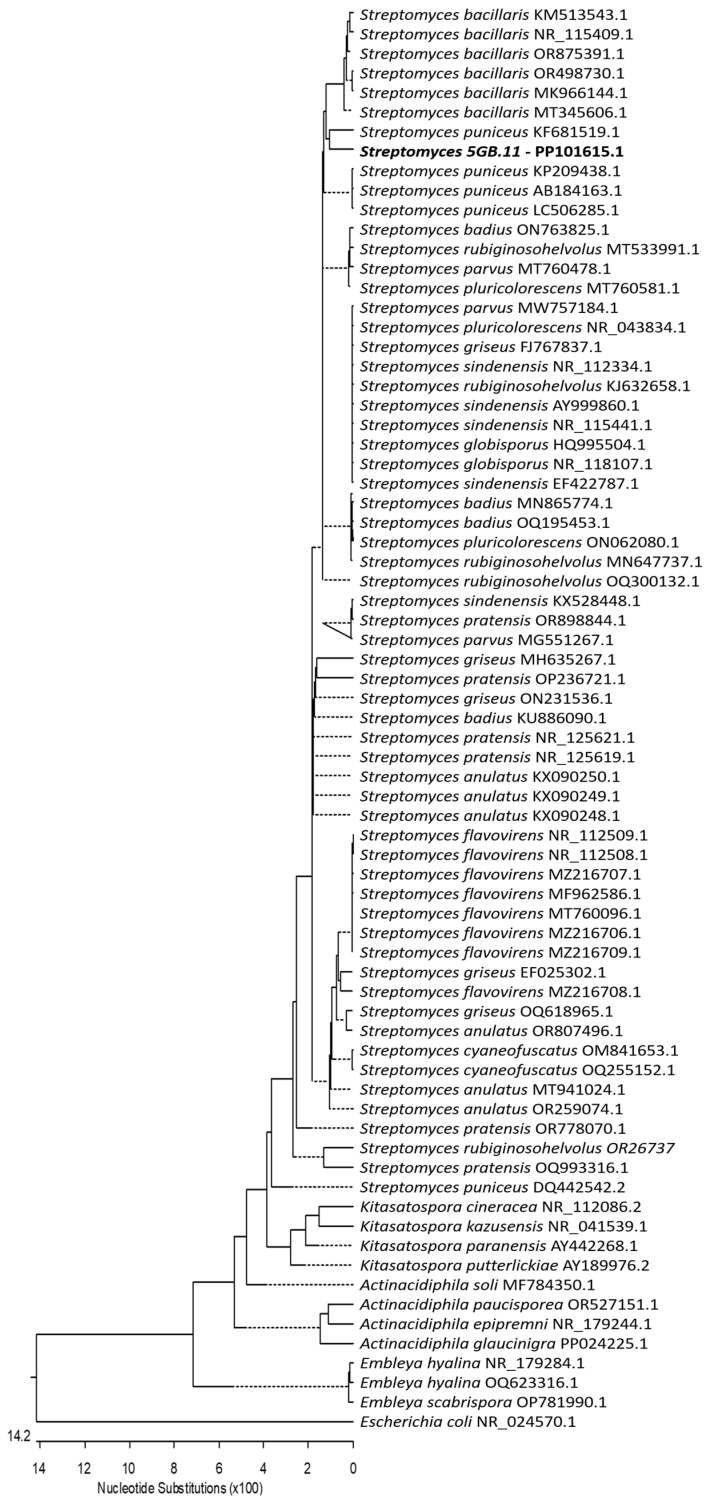

Actinomycete strain BC-5GB.11 was isolated from surface sediments collected in the intertidal zone of the inner Bay of Cadiz (Cádiz, Spain). This strain was sent for sequencing and identification to the identification service of the Spanish Type Culture Collection (CECT, https://www.uv.es/cect, accessed on 28 December 2023). The 16S-rRNA gene was sequenced and compared with those in NCBI databases. As a result, CECT identified strain BC-5GB.11 as Streptomyces. Then, a neighbor-joining phylogenetic analysis was conducted using the Kimura two-parameter model and a bootstrap test with 5000 runs (MegAlign, DNASTAR® La-Sergene package). A total of seventy-two sequences of the ribosomal DNA region comprising the 16S rRNA gene were downloaded from the Gen-Bank database. These sequences were selected from related species and genera in the family Streptomycetaceae and included five genera and twenty-four species. Based on all these studies, it was determined that strain BC-5GB.11 is grouped with the species S. puniceus (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Neighbor-joining tree constructed using 16S-rRNA gene sequences, comprising sequences identified in this study (highlighted in bold) and published sequences obtained from the GenBank database. The length of each branch pair reflects the distance between the respective sequence pairs. A dotted line on the tree denotes a negative branch length, while the bar indicates the number of nucleotide substitutions.

E. boetica was collected at “El Pinar del Hierro” in Chiclana de la Frontera, Cádiz (Spain). The n-hexane-soluble fraction of the methanolic extract of the aerial parts of E. boetica was fractionated and purified by silica gel column chromatography to afford the lathyrane euphoboetirane A (1), as indicated in the Section 3.

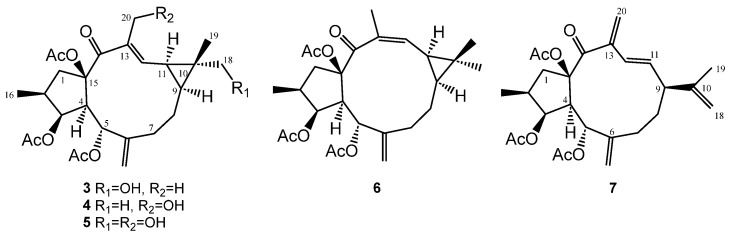

Preparative scale microbial transformation of 1 by S. puniceus BC-5GB.11 furnished three new hydroxylated lathyranes 3–5, one derivative with an isomerization of the ∆12,13 double bond (6), and one product where a cleavage for the cyclopropane ring has occurred (7) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Biotransformation products of euphoboetirane A (1) by Streptomyces puniceus BC-5GB.11.

The molecular formulas for compounds 3 and 4, C26H36O8, were identical. They were determined from [M+Na]+ molecular ions in their HRESIMS spectra (m/z 499.2322 and 499.2298, respectively, calculated for C26H36O8Na 499.2308) (Figures S8 and S16) and were 16 mass units higher than that of 1, suggesting that both were monohydroxylated derivatives of euphoboetirane A (1).

Their 1H NMR data (Table 1 and Figures S1 and S10) showed a deshielding of the signals corresponding to H-9 and H-11 (from 1.15 and 1.39 ppm for 1 [16] to 1.25 and 1.53 ppm for 3, and 1.27 and 1.59 ppm for 4, respectively). In addition, each one showed the absence of one of the singlet methyl signals and the appearance of new signals corresponding to methylenes bound to oxygen (3.46 and 3.39 ppm, d, J = 11.1 Hz, and 4.32 and 4.17 ppm, d, J = 12.2 Hz for 3 and 4, respectively). The disappearance of the signal corresponding to the methyl on the double bond (C-20) in compound 4 placed the new hydroxyl group at position C-20. In compound 3, it must be located on one of the methyls of the gem-dimethyl group. The exact location was established through the nOe effects observed between this methylene group and H-9 and H-11 (Figure 4 and Figure S7c).

Table 1.

1H (400 MHz) and 13C (100 MHz) NMR spectroscopic data for compounds 3–5 in CDCl3.

| 3 | 4 | 5 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Position | δH, Mult (J in Hz) | δC, Type | δH, Mult (J in Hz) | δC, Type | δH, Mult (J in Hz) | δC, Type |

| 1α | 3.40, dd (14.6, 8.4) | 48.3, CH2 | 3.41, dd (14.5, 8.7) | 48.0, CH2 | 3.40, dd (14.5, 8.7) | 48.0, CH2 |

| 1β | 1.56, dd (14.6, 11.4) | 1.63–1.56, m | 1.60, dd (14.5, 11.5) | |||

| 2 | 2.30–2.19, m | 37.1, CH | 2.33–2.24, m | 37.2, CH | 2.30–2.20, m | 37.2, CH |

| 3 | 5.53, t (3.5) | 80.2, CH | 5.57, t (3.5) | 80.1, CH | 5.57, t (3.5) | 80.1, CH |

| 4 | 2.74, dd (10.4, 3.5) | 52.2, CH | 2.83, dd (10.3, 3.5) | 52.2, CH | 2.83, dd (10.3, 3.5) | 52.3, CH |

| 5 | 6.05, d (10.4) | 65.7, CH | 6.06, d (10.3) | 65.6, CH | 6.07, d (10.3) | 65.5, CH |

| 6 | - | 144.2, C | - | 143.2, C | - | 143.2, C |

| 7α | 2.12–2.04, m | 34.9, CH2 | 2.15–2.09, m | 34.7, CH2 | 2.16–2.10, m | 34.7, CH2 |

| 7β | 2.30–2.19, m | 2.24–2.17, m | 2.30–2.20, m | |||

| 8α | 1.95–1.87, m | 21.2, CH2 | 2.05–1.99, m | 21.6, CH2 | 2.06–1.99, m | 21.2, CH2 |

| 8β | 1.75, m | 1.72, tdd (14.0, 11.9, 2.0) | 1.84–1.71, m | |||

| 9 | 1.25, ddd (12.2, 8.6, 3.9) | 30.8 CH | 1.27, ddd (14.0, 8.8, 4.0) | 36.4, CH | 1.39, ddd (12.1, 8.4, 3.9) | 31.8 CH |

| 10 | - | 30.8, C | - | 26.8, C | - | 32.0, C |

| 11 | 1.53, dd (11.3, 8.6) | 24.7 CH | 1.59, dd (11.6, 8.2) | 28.3, CH | 1.77, dd (11.6, 8.4) | 24.7 CH |

| 12 | 6.46, dd (11.3, 1.3) | 144.9, CH | 6.52, d (11.6) | 150.8, CH | 6.53, d (11.6) | 149.0, CH |

| 13 | - | 135.0, C | - | 135.5, C | - | 136.4, C |

| 14 | - | 196.9 C | - | 198.7, C | - | 198.7 C |

| 15 | - | 92.3, C | - | 92.1, C | - | 92.0, C |

| 16 | 0.88, d (6.7) | 14.1, CH3 | 0.91, d (6.7) | 14.1, CH3 | 0.91, d (6.7) | 14.1, CH3 |

| 17a | 4.98, s | 115.6, CH2 | 5.07, d (1.2) | 117.6, CH2 | 5.09, s | 117.7, CH2 |

| 17b | 4.71, s | 4.84, s | 4.85, s | |||

| 18a | 3.46, d (11.1) | 71.7, CH2 | 1.16, s | 16.8, CH3 | 3.51, d (11.1) | 71.7, CH2 |

| 18b | 3.39, d (11.1) | 3.40, d (11.1) | ||||

| 19 | 1.20, s | 12.5, a CH3 | 1.14, s | 28.9, CH3 | 1.22, s | 12.5, CH3 |

| 20a | 1.67, d (1.2) | 12.4, a CH3 | 4.32, d (12.2) | 58.3, CH2 | 4.31, d (12.4) | 58.2, CH2 |

| 20b | 4.17, dd (12.2, 5.9) | 4.20, d (12.4) | ||||

| 20-OH | - | - | 2.42, brs | - | - | - |

| 3-OCOCH3 | 2.02, s | 20.9, CH3 | 2.03, s | 20.9, CH3 | 2.04, b s | 20.9, c CH3 |

| 3-OCOCH3 | - | 170.7, C | - | 170.7, C | - | 170.6, C |

| 5-OCOCH3 | 1.96, s | 21.2, CH3 | 1.98, s | 21.2, CH3 | 1.99, b s | 21.2, c CH3 |

| 5-OCOCH3 | - | 170.6, C | - | 170.6, C | - | 170.6, C |

| 15-OCOCH3 | 2.08, s | 22.0, CH3 | 2.08, s | 21.9, CH3 | 2.10, s | 22.0, CH3 |

| 15-OCOCH3 | - | 169.8, C | - | 169.8, C | - | 169.8, C |

a–c Interchangeable signals.

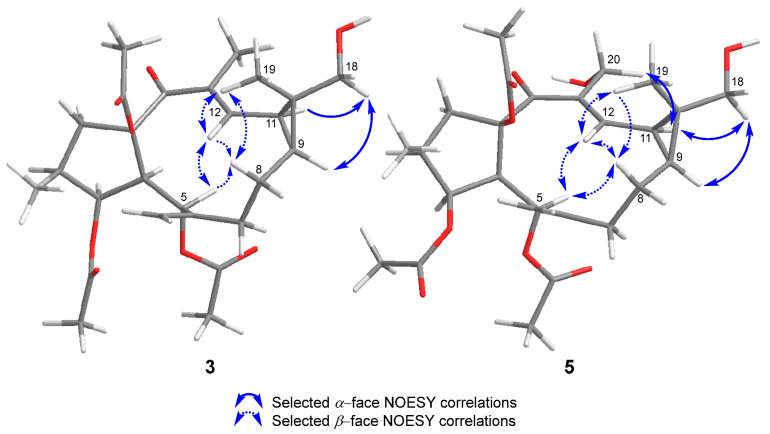

Figure 4.

Selected NOESY correlations for compounds 3 and 5.

Based on the NOESY correlations (Figures S6, S7a–d, and S15a–d), the absolute configuration described for euphoboetirane A (1) [16,17,18,19], and the similarity of the electronic circular dichroism (ECD) spectra of 3 and 4 (Figures S9 and S17) to that of 1 [16], the structures of 3 and 4 were determined as (10R)-18-hydroxyeuphoboetirane A and 20-hydroxyeuphoboetirane A, respectively.

Compound 5 showed spectroscopic characteristics common to both 3 and 4 (Table 1). Its molecular formula, C26H36O9, deduced from a [M+Na]+ molecular ion in its HRESIMS (m/z 515.2260 [M+Na]+, calculated for C26H36O8Na 515.2257) (Figure S25), indicated the presence of 32 additional mass units to that of compound 1, which was in agreement with the presence of two extra hydroxyl groups in the molecule. They were located on C-18 and C-20, as supported by the HMBC correlations between H2-18 and C-9 and between H-12 and C-20 (Figures S22 and S45).

The relative stereochemistry of the C-18-hydroxyl group was deduced as α by the NOESY correlations between H2-18 and H-9 and H-11 (Figure 4 and Figure S24c). The same configuration as 3 was inferred for 5 based on additional NOESY correlations between H-12 and H-5, H-8β, and H3-19; H-5 and H-8β; H2-20 and H-11; and between H3-19 and H-8β (Figures S23 and S24a,e,d). As a result, the structure of 5 was established as (10R)-18,20-dihydroxyeuphoboetirane A.

On the other hand, compound 6 showed a molecular formula, C26H36O7, determined by HRMS (m/z 483.2377 [M+Na]+, calculated for C26H36O7Na 483,2359) (Figure S34), which was identical to that of compound 1. The HMBC correlations (Figures S31 and S45) observed indicated the same connectivity as 1, therefore it might be an isomeric compound. The principal difference observed in its 1H NMR spectrum (Figure S27) was the large shielding of proton H-12 (from 6.48 ppm in 1 [16] to 5.28 ppm in 6, Table 2), as well as its coupling constant (d, J = 11.4 Hz in 1 [16] and dd, J = 8.7, 1.6 Hz in 6). Furthermore, the 13C NMR spectrum of 6 (Figure S28) showed a shift of the signals corresponding to C-12 and C-20 to upfield and downfield, respectively, in comparison to 1 (δC 146.7 for C-12 and δC 12.5 for C-20 in 1 [16]; δC 134.8 for C-12 and δC 22.2 for C-20 in 6). These data indicate that 6 might be the Z isomer of 1 [20].

Table 2.

1H (400 MHz) and 13C (100 MHz) NMR spectroscopic data for compounds 6 and 7 in CDCl3.

| 6 | 7 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Position | δH, Mult (J in Hz) | δC, Type | δH, Mult (J in Hz) | δC, Type |

| 1α | 3.08, dd (13.6, 6.7) | 45.6, CH2 | 2.96, dd (14.5, 6.4) | 45.9, CH2 |

| 1β | 1.76, t (13.6) | 2.24–2.17, m | ||

| 2 | 2.18–2.10, m | 37.5, CH | 2.18–2.07, m | 38.2, CH |

| 3 | 5.51, t (4.0) | 78.5, CH | 5.46, t (3.7) | 77.2, CH |

| 4 | 2.77, dd (9.0, 4.0) | 51.6, CH | 2.87, dd (10.2, 3.7) | 51.2, CH |

| 5 | 5.83, d (9,0) | 73.0, CH | 5.77, d (10.2) | 73.2, CH |

| 6 | - | 145.1, C | - | 142.8, C |

| 7α | 1.97–1.84, m | 29.7, CH2 | 1.76–1.67, m | 26.5, CH2 |

| 7β | 2.29, m | 2.09–1.99, m | ||

| 8α | 1.97–1.84, m | 23.0, CH2 | 1.91–1.76, m | 26.2, CH2 |

| 8β | 1.11, m | 1.91–1.76, m | ||

| 9 | 0.62, ddd (11.0, 8.7, 1.9) | 34.8, CH | 2.63, td (10.5, 5.7) | 52.4, CH |

| 10 | - | 20.8, C | - | 146.5, C |

| 11 | 1.50, t (8.7) | 23.9, CH | 5.59, dd (15.8, 10.5) | 138.5, CH |

| 12 | 5.28, dd (8.7, 1.6) | 134.8, CH | 5.94, d (15.8) | 124.5, CH |

| 13 | - | 138.0, C | - | 144.3, C |

| 14 | - | 204.4, C | - | 198.0, C |

| 15 | - | 92.0, C | - | 91.4, C |

| 16 | 0.91, d (6.6) | 13.3, CH3 | 0.91, d (6.4) | 13.4, CH3 |

| 17a | 5.33, s | 115.5, CH2 | 5.31, d (2.7) | 114.5, CH2 |

| 17b | 4.92, s | 4.99, bs | ||

| 18 | 1.03, s | 15.5, CH3 | 1.71, s | 21.1, CH3 |

| 19 | 1.04, s | 28.2, CH3 | 4.72, d (5.9) | 110.2, CH2 |

| 20a | 1.83, s | 22.2, CH3 | 5.29, s | 115.4, CH2 |

| 20b | 5.25, s | |||

| 3-OCOCH3 | 2.04, s | 20.9, CH3 | 2.02, s | 20.7, CH3 |

| 3-OCOCH3 | - | 170.4, C | - | 170.4, C |

| 5-OCOCH3 | 1.98, s | 21.1, CH3 | 1.96, s | 20.9, CH3 |

| 5-OCOCH3 | - | 169.5, C | - | 169.5, C |

| 15-OCOCH3 | 2.14, s | 21.9, CH3 | 2.23, s | 21.7, CH3 |

| 15-OCOCH3 | - | 170.3, C | - | 169.1, C |

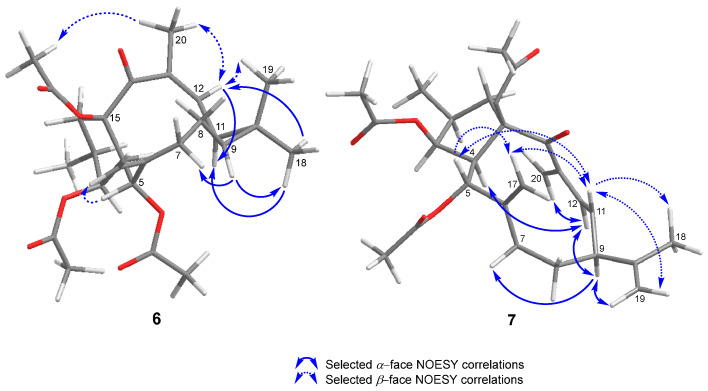

The isomerization was supported by the NOESY correlation observed between H-12 and H3-20 (Figure 5, Figures S32 and S33b,c) and by the negative cotton effect (∆ε −4.06) observed in its ECD spectrum (Figure S35) at 228 nm, opposite to that shown by 1 [16]. Accordingly, the structure of 6 was assigned as (12Z)-euphoboetirane A.

Figure 5.

Selected NOESY correlations for compounds 6 and 7.

Finally, compound 7 showed a molecular ion at m/z 481.2193 [M+Na]+ (calc. for C26H34O7Na 481.2202) (Figure S43), which allowed us to deduce its molecular formula as C26H34O7. The 1H NMR spectrum (Figure S36) of compound 7 showed similar main features for ring A to those of the previous compounds, but a significant change in rings B-C could be inferred from it. The characteristic signals for H-9 and H-11, as well as the signals corresponding to the gem-dimethylcyclopropane fragment, were missing (Table 2). Conversely, a spin system H2-7/H2-8/H-9/H-11/H-12 was identified in its 1H-1H COSY spectrum (Figure S38), which pointed to a C-10/C-11 bond cleavage of the cyclopropane ring. Indeed, proton and carbon resonances characteristic of an isopropenyl system were present. Moreover, olefinic protons located at C-10 (19), C-11 (12), and C-13 (20) were also observed in their NMR spectra (Figures S36 and S37).

HMBC correlations from H-11 to C-8, C-9, and C-13 and from H-12 to C-9, C-13, C-14, and C-20 (Figures S40 and S45) confirmed the cyclopropane rearrangement to a secolathyrane skeleton. Additional HMBC correlations from H-9 to C-8, C-10, C-11, C-12, C-18, and C-19, and from H2-18 to C-9, C-10, and C-19, indicated the presence of a conjugated double bond system between C-11/C-12 and C-13/C-20.

The configuration of the ∆11,12 doubled bond was assigned as E because of the large coupling constant between H-11 and H-12 (J = 15.8 Hz), as well as the NOESY correlations observed between H-11 and H-5, H2-17, H3-18, and H2-19; and between H-12 and H-4, H-9, and H2-20 (Figure 5, Figures S41 and S42a,c). On the other hand, the stereochemistry of the isopropenyl group at C-9 was assigned as β based on the NOESY correlations observed between H-9, H-7α, and H-12 (Figures S42a and S42h). As a result, the structure of 7 was established as (2S,3S,4R,5S,9S,15R)-3,5,15-tri-O-acetyl-10,11-secolathyra-6(17),10(19),11E,13(20)-tetraen-14-one. This cyclopropane rearrangement has been previously reported for the biotransformation of lathyrol and 7β-lathyrol by M. ramanniana [11].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Experimental Procedures

Optical rotations were determined with a JASCO P-2000 polarimeter (JASCO, Tokyo, Japan). Infrared spectra were recorded on a PerkinElmer Spectrum BX FT-IR spectrophotometer (PerkinElmer, Waltham, CA, USA) and reported as wave number (cm−1). ECD spectra were recorded on a JASCO J-1500 CD spectrometer (JASCO, Tokyo, Japan). 1H and 13C NMR measurements were recorded on an Agilent 400 MHz NMR spectrometer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) with SiMe4 as the internal reference. Chemical shifts are expressed in ppm (δ), referenced to CDCl3 (Eurisotop, Saint-Aubiu, France, δH 7.25, δC 77.0). COSY, HSQC, HMBC, and NOESY experiments were performed using a standard Agilent pulse sequence. Spectra were assigned using a combination of 1D and 2D techniques. HRMS was performed in a Q-TOF mass spectrometer (Xevo-G2-S QTOF; Waters, Manchester, UK) in the positive-ion ESI mode. TLC was performed on Merck Kiesegel 60 Å F254, 0.25 mm layer thickness. Silica gel 60 (60−200 µm, VWR) was used for column chromatography. Purification using HPLC was performed with a Merck-Hitachi Primade apparatus equipped with a UV−vis detector (Primaide 1410) and a refractive index detector (RI-5450), and a Merck-Hitachi LaChrom apparatus equipped with a UV−vis detector (L 4250) and a differential refractometer detector (RI-7490) (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). LiChroCART LiChrospher Si 60 (5 µm, 250 mm × 4 mm), LiChroCART LiChrospher Si 60 (10 µm, 250 mm × 10 mm), and ACE 5 SIL (5 µm, 250 mm × 4.6 mm id) columns were used for isolation experiments.

3.2. Plant Material

The whole plants of Euphorbia boetica were collected at El Pinar del Hierro (Chiclana de la Frontera, Cádiz, Spain) in March 2020 with the permission of the national competent authorities (Dirección General de Biodiversidad, Bosques y Desertificación, Secretaría de Estado de Medio Ambiente, Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica y Reto Demográfico, reference number ESNC64, and Consejería de Agricultura, Ganadería Pesca y Desarrollo Sostenible-Delegación Territorial de Cádiz, Junta de Andalucía, reference number 201999901092011).

3.3. Microorganisms and Their Identification

The actinomycete Streptomyces puniceus BC-5GB.11 was isolated from intertidal sediments collected in the inner Bay of Cadiz (Cádiz, Spain) within a Spartina spp. bed with the permission of the national competent authority (ABSCH-CNA-ES-240784-3, reference number ESNC84). Surface sediment samples were collected aseptically in the field, stored in sterile packaging, kept on ice, brought to the laboratory, and immediately processed. Sediment was diluted with sterile seawater (SSW), and aliquots were grown on potato dextrose agar (PDA) plates and marine agar plates (Condalab S.L.) and incubated at 25 °C for 5–10 d. Bacterial colonies were selected and streaked on PDA plates under axenic conditions. The isolates were maintained on PDA at 25 °C for routine experiments, and spores were stored in 60% (v/v) glycerol at −20 °C for later studies.

The BC-5GB.11 bacterial strain isolated was identified using the service of the Spanish Type Culture Collection (CECT, https://www.uv.es/cect, accessed on 28 December 2023) based on molecular techniques. Amplification and sequencing (with readings in both directions) of the 16S-rRNA gene were carried out. The sequencing of this region was compared with that in NCBI databases. The sequence was submitted to the NCBI database with the accession number PP101615.1. To study the phylogenetic relationship of our isolate, other sequences of related genera and species (72 sequences) from the family Streptomycetaceae were downloaded from the GenBank database and included in the phylogenetic trees (Figure 2).

This microorganism was preserved on PDA plugs of 1 cm diameter in H2O at 4 °C, and it is deposited in the Bacteriological Collection of the University of Cadiz.

3.4. Extraction and Isolation of Euphoboetirane A (1)

Compound 1 was isolated from the aerial parts of E. boetica following the procedure previously described in the literature [7]. The aerial parts of the fresh plant (3.0 kg) were frozen with liquid nitrogen, powdered, and extracted with MeOH (2.5 L × 3) at room temperature for 24 h. The MeOH extract was evaporated under reduced pressure to yield a crude extract, which was suspended in water (1 L) and then extracted with n-hexane (1.5 L × 3) and CH2Cl2 (1.5 L × 3), sequentially. Evaporation of the solvent at reduced pressure yielded 33.3 g and 8.9 g of the n-hexane- and CH2Cl2-soluble extracts, respectively. The n-hexane extract was fractionated through silica gel column chromatography, using an increasing gradient of EtOAc in n-hexane (10–100%) to afford 21 fractions, according to TLC analysis. Fractions 4–7 were combined and further purified by column chromatography using a gradient mixture of CH2Cl2 and acetone of increasing polarity (0–2%) to yield 1 (2.0 g).

3.5. Biotransformation of Euphoboetirane A (1)

Streptomyces puniceus BC-5GB.11 was grown in seventeen 500-mililiter Erlenmeyer flasks containing 200 mL of ISP2 medium (4 g of yeast extract, 10 g of malt extract, and 4 g of dextrose per liter of sea water) at pH 7.3. Each flask was inoculated with 1300 µL of a fresh conidial suspension obtained by adding 25 mL of sterile ISP2 medium to seven Petri dishes (9 cm in diameter) cultured with the strain BC-5GB.11 for 17 d. The flasks were shaken at 200 rpm and 25 °C under continuous white light (i.e., daylight lamp) for 3 d. A solution of euphoboetirane A (1) in DMSO (300 μL) was then added to each flask to a final concentration of 88 ppm. The culture control consisted of a fermentation flask to which 300 µL of DMSO was added. The substrate control contained sterile ISP2 medium and the same concentration of 1 dissolved in 300 µL of DMSO. All flasks were incubated under identical conditions as described above for an additional period of 11 d. The optimal biocatalysis time was established as a result of a preliminary study to determine the time at which all euphoboetirane A (1) is consumed in order to achieve maximum production of the biotransformation products.

3.6. Extraction, Isolation, and Characterization of Biotransformation Products

Once the biotransformation process was finished, the broth was vacuum filtered using a 200 µm pore-size Nytal filter. The mycelium was discarded, and the culture medium was saturated with NaCl and extracted with EtOAc (×3). The organic phase was washed with H2O (×3), dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, and filtered. Evaporation of the solvent under reduced pressure at a rotary evaporator yielded 522.5 mg of crude extract. This extract was purified by column chromatography using a gradient of increasing polarity of n-hexane/ethyl acetate. The fractions obtained were analyzed by CCF, combining those with the highest affinity. Successive purifications by semipreparative and analytical HPLC led to the obtaining of the following compounds:

(10R)-18-Hydroxyeuphoboetirane A (3): Purified through semipreparative HPLC (n-hexane:EtOAc 70:30, flow 3.0 mL/min, tR = 57 min), 87.2 mg, 28.1% yield. Amorphous solid; = +160.0 (c 1.2, MeOH); ECD (MeOH) λ (∆ε) 312 (+0.12) nm (Figure S9); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ɛ) 313 (3.1970) nm; IR (KBr) νmax 2932, 1739, 1372, 1258, 1022 cm−1; 1H and 13C NMR data see Table 1 and Figures S1–S5; HRMS (ESI+) 499.2322 [M+Na]+ (calc. for C26H36O8Na 499.2308) (Figure S8).

20-Hydroxyeuphoboetirane A (4): Purified through semipreparative HPLC (n-hexane:EtOAc 65:35, flow 3.0 mL/min, tR = 46 min), 8.3 mg, 2.7% yield. Amorphous solid; = +154.0 (c 0.6, MeOH); ECD (MeOH) λ (∆ε) 318 (+1.06) nm (Figure S17); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ɛ) 309 (3.180) nm; IR (KBr) νmax 2933, 1740, 1372, 1257, 1019 cm−1; 1H and 13C NMR data see Table 1, Figures S10–S14; HRMS (ESI+) 499.2298 [M+Na]+ (calc. for C26H36O8Na 499.2308).

(10R)-18,20-Dihydroxyeuphoboetirane A (5): Purified through analytical HPLC (CHCl3:MeOH 97:3, flow 1.00 mL/min, tR = 9 min), 4.5 mg, 1.4% yield. Amorphous solid; = +41.0 (c 0.4, MeOH); ECD (MeOH) λ (∆ε) 225 (-2.88), 249 (+2.25), 295 (+2.14) nm (Figure S26); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ɛ) 300 (2.137) nm; IR (KBr) νmax 2931, 1739, 1372, 1260, 1020 cm−1; 1H and 13C NMR data see Table 1, Figures S18–S22; HRMS (ESI+) 515.2260 [M+Na]+ (calc. for C26H36O9Na 515.2257).

(12Z)-Euphoboetirane A (6): Purified through analytical HPLC (n-hexane:EtOAc 90:10, flow 1.0 mL/min, tR = 84 min), 8.3 mg, 2.7% yield. Amorphous solid; = −41 (c 0.2, MeOH); ECD (MeOH) λ (∆ε) 227 (−4.06) nm (Figure S35); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ɛ) 298 (1.850) nm; IR (KBr) νmax 2932, 1740, 1373, 1250, 1022 cm−1; 1H and 13C NMR data see Table 2, Figures S27–S31; HRMS (ESI+) 483.2377 [M+Na]+ (calc. for C26H36O7Na 483.2359).

(2S,3S,4R,5S,9S,15R)-3,5,15-Tri-O-acetyl-10,11-secolathyra-6(17),10(19),11E,13(20)-tetraen-14-one (7): Purified through semipreparative HPLC (n-hexane:EtOAc 7:3, flow 3.0 mL/min, tR = 13 min), 3.2 mg, 1.0%, yield. Amorphous solid; = +76.0 (c 0.07, MeOH); ECD (MeOH) λ (∆ε) 242 (+10.70) nm (Figure S44); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ɛ) 295 (1.5246) nm; IR (KBr) νmax 2933, 1741, 1372, 1252, 1022 cm−1; 1H and 13C NMR data see Table 2, Figures S36–S40; HRMS (ESI+) 481.2193 [M+Na]+ (calc. for C26H34O7Na 481.2202).

4. Conclusions

Five new lathyrane-type diterpenoids were obtained by microbial transformation of euphoboetirane A (1) with Streptomyces puniceus BC-5GB.11. This strain, isolated from sediment samples from the intertidal zone of the inner Bay of Cadiz, catalyzed the regioselective hydroxylation of 1 at C-18 and C-20, as well as the isomerization of the ∆12,13 double bond. In addition, a rearranged cyclopropane compound was produced (7).

These derivatives have contributed to increasing the structural diversity of our lathyrane-based library, which will allow us to further investigate the relationship between the functionalization presented by these diterpenes and their neurogenesis-promoting activity. Studies are in progress to evaluate the ability of major metabolites to promote the release of transforming growth factor α (TFGα) and neuregulin 1 (NRG1) in cell cultures isolated from the subventricular zone (SVZ) of adult mice, which is an indirect measure to predict the role of these compounds as neurorregenerative agents.

Acknowledgments

Use of the NMR and MS facilities at the Servicio Centralizado de Ciencia y Tecnología (SC-ICYT) of the University of Cádiz is acknowledged. We appreciate the assistance provided by Juan Luis Rendon Vega of the Botanical Garden of San Fernando (Cádiz).

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijms25042289/s1.

Author Contributions

R.H.-G., R.D.-P. and J.M.B.-A. were involved in experimental design, data analysis, discussion of results, and article preparation and wrote the manuscript with the support of V.E.G.-R. and A.J.M.-S.; J.M.B.-A. and F.E.-M. collected the plants. V.E.G.-R. collected the sediment samples and isolated the actinomycete strain. R.D.-P. and J.M.B.-A. directed the research and coordinated the experiments. F.E.-M. conducted the biotransformation experiment and was involved in data acquisition. R.H.-G. and R.D.-P. acquired the funding. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in Supplementary Material.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

This work was co-financed by the Spanish Agencia Estatal de Investigación MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by “ERDF: A Way of Making Europe” (grant number PID2022-142418OB-C22), and by the Consejería de Transformación Económica, Industria, Conocimiento y Universidades, Junta de Andalucía (grant number P18-RT-2655).

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.Zhan Z., Li S., Chu W., Yin S. Euphorbia Diterpenoids: Isolation, Structure, Bioactivity, Biosynthesis, and Synthesis (2013–2021) Nat. Prod. Rep. 2022;39:2132–2174. doi: 10.1039/D2NP00047D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferreira M.-J.U., Duarte N., Reis M., Madureira A.M., Molnár J. Euphorbia and Momordica Metabolites for Overcoming Multidrug Resistance. Phytochem. Rev. 2014;13:915–935. doi: 10.1007/s11101-014-9342-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vasas A., Hohmann J. Euphorbia Diterpenes: Isolation, Structure, Biological Activity, and Synthesis (2008–2012) Chem. Rev. 2014;114:8579–8612. doi: 10.1021/cr400541j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vasas A., Redei D., Csupor D., Molnar J., Hohmann J. Diterpenes from European Euphorbia Species Serving as Prototypes for Natural-Product-Based Drug Discovery. European J. Org. Chem. 2012;2012:5115–5130. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.201200733. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shi Q.-W., Su X.-H., Kiyota H. Chemical and Pharmacological Research of the Plants in Genus Euphorbia. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:4295–4327. doi: 10.1021/cr078350s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kemboi D., Siwe-Noundou X., Krause R.W.M., Langat M.K., Tembu V.J. Euphorbia Diterpenes: An Update of Isolation, Structure, Pharmacological Activities and Structure—Activity Relationship. Molecules. 2021;26:5055. doi: 10.3390/molecules26165055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flores-Giubi E., Geribaldi-Doldán N., Murillo-Carretero M., Castro C., Durán-Patrón R., Macías-Sánchez A.J., Hernández-Galán R. Lathyrane, Premyrsinane, and Related Diterpenes from Euphorbia boetica: Effect on in Vitro Neural Progenitor Cell Proliferation. J. Nat. Prod. 2019;82:2517–2528. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.9b00343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Domínguez-García S., Geribaldi-Doldán N., Gómez-Oliva R., Ruiz F.A., Carrascal L., Bolívar J., Verástegui C., Garcia-Alloza M., Macías-Sánchez A.J., Hernández-Galán R., et al. A Novel PKC Activating Molecule Promotes Neuroblast Differentiation and Delivery of Newborn Neurons in Brain Injuries. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11:262. doi: 10.1038/s41419-020-2453-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murillo-Carretero M., Geribaldi-Doldán N., Flores-Giubi E., García-Bernal F., Navarro-Quiroz E.A., Carrasco M., Macías-Sánchez A.J., Herrero-Foncubierta P., Delgado-Ariza A., Verástegui C., et al. ELAC (3,12-Di-O-Acetyl-8-O-Tigloilingol), a Plant-Derived Lathyrane Diterpene, Induces Subventricular Zone Neural Progenitor Cell Proliferation through PKCβ Activation. Brit. J. Pharmacol. 2017;174:2373–2392. doi: 10.1111/bph.13846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silva E.d.O., Furtado N.A.J.C., Aleu J., Collado I.G. Terpenoid Biotransformations by Mucor Species. Phytochem Rev. 2013;12:857–876. doi: 10.1007/s11101-013-9313-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu Y., Yin C., Cao Y., Liu X., Yu J., Zhang J., Yu B., Cheng Z. Regioselective Hydroxylation of Lathyrane Diterpenoids Biocatalyzed by Microorganisms and Its Application in Integrated Synthesis. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2016;133:S352–S359. doi: 10.1016/j.molcatb.2017.02.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valentová K. Biotransformation of Natural Products and Phytochemicals: Metabolites, Their Preparation, and Properties. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023;24:8030. doi: 10.3390/ijms24098030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rico-Martínez M., Medina F.G., Marrero J.G., Osegueda-Robles S. Biotransformation of diterpenes. RSC Adv. 2014;4:10627. doi: 10.1039/C3RA45146A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu X., Cheng Z. Microbial and Chemical Transformations of Euphorbia Factor L1 and the P-Glycoprotein Inhibitory Activity in Zebrafishes. Nat. Prod. Res. 2023;37:871–881. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2022.2095379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xiao S., Xu X., Wei X., Xin J., Li S., Lv Y., Chen W., Yuan W., Xie B., Zu X., et al. Comprehensive Metabolic Profiling of Euphorbiasteroid in Rats by Integrating UPLC-Q/TOF-MS and NMR as Well as Microbial Biotransformation. Metabolites. 2022;12:830. doi: 10.3390/metabo12090830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu J., Li G., Huang J., Zhang C., Zhang L., Zhang K., Li P., Lin R., Wang J. Lathyrane-Type Diterpenoids from the Seeds of Euphorbia lathyris. Phytochemistry. 2014;104:79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2014.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Engel D.W. The Determination of Absolute Configuration and Δf” Values for Light-Atom Structures. Acta Cryst. B. 1972;28:1496–1509. doi: 10.1107/S0567740872004492. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Engel D.W., Zechmeister K., Hoppe W. Experience in the Determination of Absolute Configuration of Light Atom Compounds by X-Ray Anomalous Scattering. Tetrahedron Lett. 1972;13:1323–1326. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(01)84617-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiao W., Mao Z., Dong W., Deng M., Lu R. Euphorbia Factor L8: A Diterpenoid from the Seeds of Euphorbia lathyris. Acta Cryst. E. 2008;64:o331. doi: 10.1107/S1600536807066901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li L., Huang J., Lyu H., Guan F., Li P., Tian M., Xu S., Zhao X., Liu F., Paetz C., et al. Two Lathyrane Diterpenoid Stereoisomers Containing an Unusual trans-gem-Dimethylcyclopropane from the Seeds of Euphorbia lathyris. RSC Adv. 2021;11:3183–3189. doi: 10.1039/D0RA10724G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in Supplementary Material.