Abstract

Specification and differentiation of the cardiac muscle lineage appear to require a combinatorial network of many factors. The cardiac muscle-restricted homeobox protein Csx/Nkx2.5 (Csx) is expressed in the precardiac mesoderm as well as the embryonic and adult heart. Targeted disruption of Csx causes embryonic lethality due to abnormal heart morphogenesis. The zinc finger transcription factor GATA4 is also expressed in the heart and has been shown to be essential for heart tube formation. GATA4 is known to activate many cardiac tissue-restricted genes. In this study, we tested whether Csx and GATA4 physically associate and cooperatively activate transcription of a target gene. Coimmunoprecipitation experiments demonstrate that Csx and GATA4 associate intracellularly. Interestingly, in vitro protein-protein interaction studies indicate that helix III of the homeodomain of Csx is required to interact with GATA4 and that the carboxy-terminal zinc finger of GATA4 is necessary to associate with Csx. Both regions are known to directly contact the cognate DNA sequences. The promoter-enhancer region of the atrial natriuretic factor (ANF) contains several putative Csx binding sites and consensus GATA4 binding sites. Transient-transfection assays indicate that Csx can activate ANF reporter gene expression to the same extent that GATA4 does in a DNA binding site-dependent manner. Coexpression of Csx and GATA4 synergistically activates ANF reporter gene expression. Mutational analyses suggest that this synergy requires both factors to fully retain their transcriptional activities, including the cofactor binding activity. These results demonstrate the first example of homeoprotein and zinc finger protein interaction in vertebrates to cooperatively regulate target gene expression. Such synergistic interaction among tissue-restricted transcription factors may be an important mechanism to reinforce tissue-specific developmental pathways.

Increasing evidence suggests that multiple trans-acting factors and cis-acting elements cooperatively regulate the expression of cardiac muscle-specific genes (reviewed in references 28 and 36), unlike skeletal muscle myogenesis where myogenic basic helix-loop-helix factors can activate the entire myogenic program (reviewed by Olson and Klein [37a]). For example, the cardiac α-myosin heavy chain gene (α-MHC) is synergistically activated by myocyte-specific enhancer factor 2 (MEF2) and thyroid hormone receptor, and this activation depends on the binding of each factor to the DNA target sequences (27). Multiple transcription factors, such as E-box and CArG-box binding factors and Sp1, are required for the muscle-specific expression of the cardiac α-actin gene (37b). Cardiac myosin light chain 2v (MLC2v) gene expression appears to depend on several factors, including YB-1 and CARP (44, 45).

Homeobox genes have been studied extensively in many animal species, where they play fundamental roles in specifying cell fate and positional identity in embryos. The nk-4/msh-2 Drosophila gene, tinman, has been of particular interest, since it is expressed in the developing dorsal vessel, the insect equivalent of the vertebrate heart, and its mutation results in absence of heart and visceral mesoderm formation in the Drosophila embryo (3–5). The murine cardiac-specific homeobox gene Csx/Nkx2.5 (hereafter referred to as Csx), one of the vertebrate homologs of tinman, is expressed in the precardiac mesoderm and in the myocardium of the embryonic and adult heart (22, 27a). Targeted disruption of Csx results in the arrest of heart development and embryonic lethality, probably due to the arrest of heart development during the looping stage associated with the lack of myocardial cell expansion and ventricular trabeculation (29). Thus, Csx seems to play an important role in these morphogenic events and is possibly involved with the regulation of cardiac muscle-specific gene activity.

Although each homeobox gene has a specific biological function in vivo, the mechanism of specificity of homeobox protein function is not well understood because many homeoproteins exhibit relatively weak selectivities in DNA binding in vitro. A current model is that homeodomain proteins may interact with other factors that increase DNA binding and/or functional specificity in vivo. Expression of Csx in the cardiac muscle lineage coincides with expression of the transcription factor GATA4, which contains a DNA binding domain (DBD) composed of two evolutionarily conserved zinc fingers (39). GATA4 plays an important role in regulating early cardiac development. Functionally important GATA4 binding sites were identified in many cardiac muscle-specific promoters and enhancers, including α-MHC, cardiac troponin C, and brain natriuretic factor (11, 13, 19, 30). Targeted GATA4 disruption showed that GATA4 is required for the fusion of the bilateral cardiac primordia to form the heart tube and for ventral folding morphogenesis (23, 32). In addition, both Csx and GATA4 are among the earliest transcription factors expressed in the murine precardiac mesoderm (1, 16), suggesting the possibility of functional cooperativity and/or physical interactions between these proteins.

Although both Csx and GATA4 null embryos have been shown to contain differentiated cardiomyocytes, the potential genetic redundancy of members of these two multigene families makes it difficult to assess the exact role of each factor in cardiomyocyte differentiation. The Csx-related factors Nkx2.3, Nkx2.7, and Nkx2.8 as well as GATA5 and GATA6 have been shown to be expressed early in the developing heart of the vertebrate (1, 10, 20, 24, 25, 33, 34). Therefore, their specific roles in controlling the identity or differentiation of cardiac myocytes remain to be elucidated.

The atrial natriuretic factor (ANF) gene is expressed very early in embryonic development, at the stage when cells are committed to the cardiac phenotype. Throughout embryonic and fetal development, ANF expression characterizes both atrial and ventricular but not skeletal or smooth muscle cells. Because of its early onset of expression and its lineage-specific pattern of expression late in development, the ANF gene may be a good model system to identify cardiac muscle-specific transcription factor and/or determination factors. Interestingly, the rat ANF enhancer-promoter region which confers cardiac muscle-specific expression contains several putative Csx binding sites and consensus GATA4 binding sites conserved among different species, such as mice and humans. Although Csx has been shown to activate the ANF gene by binding the proximal region of the promoter (8), other putative Csx binding sites (6) are located within the cardiac muscle-specific cis element of the ANF gene.

These results lead us to hypothesize that Csx and GATA4 may interact with each other and regulate a subset of cardiac muscle-specific genes. We show here that Csx physically associates with GATA4 in vivo and in vitro. The third helix of the homeodomain of Csx and the carboxy-terminal zinc finger of GATA4 are necessary for their physical association. Either Csx or GATA4 alone transactivates ANF gene expression, but coexpression of Csx and GATA4 synergistically transactivates ANF gene expression, probably through the direct physical interaction between two factors. Csx-GATA4 interaction represents the first example of homeoprotein-zinc finger protein interaction in vertebrates to cooperatively activate transcription of a target gene.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid construction.

Wild-type Csx and its mutants used for transfection and in vitro transcription were cloned in the pcDNA3 expression vector (Invitrogen). To make the full-length Csx in pcDNA3, the mouse Csx cDNA isolated from Csx/pBS was inserted into pcDNA3 digested with BamHI and EcoRI. To construct C1-199 and C1-182 in pcDNA, the corresponding C-terminal region of Csx was deleted by using PflmI and BglII sites in Csx, respectively. Csx containing a point mutation in the third helix, Csxpm/pcDNA3, was made by subcloning the EcoRI fragment from Csxpm/pBL (6) into pcDNA3. The Csx reporter gene A20/Luc was constructed by inserting the triplicate putative Csx binding sequence (designated A20 in reference 6) by using the XmaI site into the pGL3 vector, which contains the simian virus 40 promoter fused to a luciferase gene.

Wild-type GATA4 and its mutants used for transfection and in vitro transcription were cloned in pMT2 and the BlueScript SK− (pBS) vector (Stratagene), respectively. Mutations were introduced into GATA4 cloned into pBS by using the rolling-circle mutagenesis procedure (17). After the mutation was confirmed by analysis of restriction enzyme digestions, the mutant clones were excised and cloned into pMT2. The identities of all of the mutant clones were confirmed by DNA sequencing. To construct the N-terminal zinc finger point mutant (G-NFm), cysteine residues at 236 and 239 were replaced by serine residues (C236S and C239S). The N-terminal zinc finger deletion mutant (G-NFd) consists of amino acids 1 to 213 and 242 to 440. The C-terminal zinc finger point mutant (G-CFm) contains a C290S mutation. The GATA4 reporter gene (GATA4/Luc) in the pGL2 vector is comprised of the duplicate GATA4 target sequence from the α-MHC gene (30) linked to the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase promoter fused to the luciferase gene. The ANF reporter plasmid (−638/Luc) consists of the enhancer-promoter region up to nucleotide −638 from the transcription initiation site linked to the luciferase gene (21). ANF mutant reporter genes were constructed by PCR, amplified with primers containing appropriate mutations by using the Quickchange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). All new constructs were subjected to diagnostic digestion and confirmed by DNA sequencing. The oligonucleotides used for constructing mutant ANF reporter genes are as follows (putative DNA binding sites are underlined, and boldface letters indicate mutated nucleotides): ANF-Gm1 (which has mutations at the GATA4 binding site), −2965′ GGCGAGCGCCCAGGAATGCAACCAAGGACTCTTTTCTG; ANF-Gm2 (which has mutations at the GATA4 binding site), −1425′ GTGACAAGCTTCGCTGGACTTGCAACTTTAAAAGGGCATG; ANF-Cm1 (which has mutations at the putative Csx binding site), −2495′ CACCT T TGAAGTGGGGGCCTACTGCAGCAAATCATCAAGAATGTG; ANF-Cm2 (which has mutations at the putative Csx binding site), −2615′ CTGCTCTTCTCACACCTTTGCCTCGGGGGCCTCTTGAGGCAAATC; ANF-Cm3 (containing mutations in both putative Csx binding sites), −2615′ CTGCTC T TC TCACACCTTTGCCGCGGGGGCCTACTGCGGCAAATCATC. The phosphorylated primers used to construct the GATA4 mutants are as follows: G183-440, 5′ TTAGAATTCGCGATGACCAGCAGGGTAGCCCTGGCTG and 5′ AATGAATTCTGATTACGCGGTCATTATGT; G1-327, 5′ AGTTGAATTCGGGCGATGTACCAAAGCCTG and 5′ AGTTGAATTCTTACTTAGATTTATTCAGGTTCT; G-NFm, 5′ GTTAGCTAGCATTGGACAGGTAGTGTCCCTCCAT and 5′ CAATGCTAGCGGCCTCTATCACAAGATGAA; G-CFm, 5′ TAATGCTAGCTAGCGGCCTCTACATGAACTC and 5′ GGCCGCTAGCATTAGATACAGGCTCACCCTCGGC; G-NFd, 5′ CTCTCTGCCTTCTGAGSGT and 5′ CCTCATTAAGCCTCAGCGCCG. A Kozak sequence and the sequence corresponding to the first two amino acids of GATA4 were included in the clone encoding the mutant protein containing amino acids 183 to 440 to obtain a translation efficiency of the mutant clone similar to that of the wild type. The primers to generate the other C-terminal zinc finger mutants of GATA4 are as follows: for TTT to SSS (amino acids 277 to 279), 5′ AGCTCGAGCCTGTGGCGTCGTAATGCGGAGGGTGAGC and 5′ GGTAGTCTGGCAGTTGGCACAGG; for WRR to SSS (amino acids 281 to 283), 5′ AGCTCGAGCAATGCCGAGGGTGAGCCTGTATGTAATG and 5′ CAGCGTGGTGGTGGTAGTCTGGC; for EGE to SSS (amino acids 286 to 288), 5′ AGCTCGAGCCCTGTATGTAATGCCTGCGGCCTCTACA and 5′ GGCATTACGACGCCACAGCGTGGT.

To construct GAL4 DBD-GATA4 fusion proteins, the cDNAs encoding amino acids 200 to 300 or 251 to 300 of GATA4 were amplified by PCR using the following primers. The PCR fragments were cloned into pGBT9 (Clontech), which resulted in an in-frame fusion between GAL4 DBD and the GATA4 fragment. The cDNAs encoding these fusion proteins as well as the GAL4 DBD control were amplified by PCR using the 5′ GAL4 oligonucleotide along with primer 3′ GAL4 or 3′ 300, and the resulting fragments were cloned into pBKRSV (Stratagene). The fidelity of the PCR was confirmed by sequencing. The primers to generate these mutants are as follows (boldface letters indicate an introduced restriction site): 5′ 200, 5′ GCGGAATTCCCCAATCTCGATATGTTTGAT; 5′ 251, 5′ TTTGAATTCCCCCTCATTAAGCCTCAGCGC; 3′ 300, 5′-CGCGGATCCTTAATGGAGCTTCATGTAGAGGCC; 5′ GAL4, 5′-GCCATGAAGCTACTGTCTTCTATC; 3′ GAL4, 5′-TTACTTGGCTGCAGGTCGACG.

Protein binding assay.

Bacterially produced glutathione S-transferase (GST)-GATA4, maltose-binding protein (MBP)-Csx, MBP-HD containing only the homeodomain of Csx, and in vitro-transcribed and -translated [35S]Met-labeled Csx or GATA4 in reticulocyte lysates were made by the methods described previously (7, 27). Deletion mutants C1-230, C1-199, C1-182, and C1-148 were translated in vitro by linearizing Csx in pcDNA3 or pBS with restriction enzymes SacII, PflmI, BagII, and AccI, respectively. In vitro protein binding and double immunoprecipitation assays were performed as described previously with slight modifications (27). Briefly, for the in vitro protein binding assay, equal amounts of GST or MBP fusion proteins (1 μg) were incubated with equal amounts (50,000 cpm) of in vitro-translated counterparts labeled with 35S, as measured by trichloroacetic acid precipitation, in NETN buffer (NaCl, 100 mM; EDTA, 1 mM; Tris [pH 8.0], 20 mM; Nonidet P-40, 0.5%) for 2 h at 4°C. Bound proteins were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and detected by autoradiography.

To perform double immunoprecipitation, 293 cells in a 100-mm-diameter cell culture dish were transfected with 7 μg each of Csx/pcDNA and GATA4/pMT2. Whole-cell extracts were prepared as described previously (26) and precleared by incubation with preimmune rabbit serum and protein A-Sepharose. These precleared cell extracts, 600 μg of protein per reaction mixture, were incubated with 3 μl of the polyclonal anti-GATA4 antiserum (1) or preimmune rabbit serum and then incubated with 20 μl of protein A-Sepharose in NETN buffer. After extensive washes, bound proteins resolved on SDS-PAGE were subjected to Western blot analysis using the monoclonal anti-Csx antibody. The characterization of the polyclonal and monoclonal anti-Csx antibodies raised against His-tagged Csx protein will be described in detail elsewhere (19a). Proteins on polyvinylidene difluoride membranes were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence analysis (Amersham). The anti-GATA4 polyclonal antibody used for Western blotting was raised against the GST-GATA4 fusion protein containing amino acids from position 183 to the carboxy-terminal end and then affinity purified (29a).

Transient-expression assay and immunostaining.

Several cell lines, 10T1/2, 293, Cos, and CV1, were cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium with 10% fetal bovine serum. The reporter gene assays were done with 10T1/2 cells, and results were confirmed with CV1 cells (data not shown). For reporter gene assays, 4 μg of the reporter gene and 2 μg of Csx and/or GATA4 in the expression vectors were transfected into cells in 60-mm-diameter cell culture plates. The murine sarcoma virus β-galactosidase plasmid, 1 μg, was cotransfected to normalize the variations in transfection efficiency. The total amount of DNA per cell culture plate was kept constant by adding the corresponding vector plasmids. Luciferase assays were done with the luciferase assay system from Promega. Transfection by the calcium phosphate precipitation method and immunostaining were performed as described previously (26). Cos cells overexpressing wild-type Csx and its mutants on coverslips were subjected to immunostaining to examine subcellular localization. The fixed cells were visualized by using polyclonal or monoclonal anti-Csx antibodies followed by anti-rabbit or anti-mouse immunoglobulin G coupled to Texas red. GATA4/pMT2, GST-GATA4 plasmids, and the anti-GATA4 antibody were generous gifts from D. B. Wilson, the wild-type ANF reporter gene (−638) was from K. R. Chien, MBP-Csx, MBP-CsxHD, and Csxpm/pBL were from R. Schwartz, and 293 human kidney carcinoma cells were from E. Nabel.

RESULTS

Intracellular association of Csx with GATA4.

Expression of the cardiac marker Csx coincides with GATA4 expression in the precardiac mesoderm, and both factors play important roles in early cardiac development. Therefore, we hypothesized that these two factors may physically associate with each other, which may lead to functional cooperativity. To explore the possibility of protein-protein interaction between Csx and GATA4, the human kidney carcinoma cell line 293 was cotransfected with Csx and GATA4. 293 cells were used as transfection recipients to study the intracellular protein association because they have a high transfection efficiency, greater than 60%, when transfected by the calcium phosphate precipitation method (data not shown). As shown in Fig. 1, Csx migrated as a 42-kDa band upon direct Western blotting of the transfected cells (lane 1), while control cell extracts did not contain this band (lane 2). The faint bands at around 36 kDa are probably proteolytic fragments since they were not observed in nontransfected cell lysates. The Csx protein was detected when cell extracts coexpressing Csx and GATA4 were immunoprecipitated with the anti-GATA4 antibody (lane 3) (1). The coimmunoprecipitation of Csx was specific since no Csx band was detected when preimmune serum was used (lane 4). In control cell extracts, the Csx protein was not detected with either serum (lanes 5 and 6). These data clearly demonstrate that Csx physically associates with GATA4 intracellularly when the two proteins are coexpressed. The converse immunoprecipitation-Western blot experiment was not possible because the GATA4 protein comigrates with the immunoglobulin heavy chain.

FIG. 1.

Csx physically associates with GATA4 in vivo. Coimmunoprecipitation was performed with extracts of 293 cells coexpressed with Csx and GATA4. The Csx protein was observed as a 42-kDa band in 293 cell extracts coexpressed with Csx and GATA4 (lane 1) but not in control cell extracts (lane 2) by Western blot analysis using anti-Csx antibody. The precleared 293 cell extracts expressing both Csx and GATA4 were immunoprecipitated with polyclonal GATA4 antiserum (G) (lane 3) or rabbit preimmune serum (p) (lane 4). Immunoprecipitated proteins were subjected to Western blotting with the affinity-purified monoclonal anti-Csx antibody. Control 293 cell extracts were incubated with GATA4 antiserum or preimmune serum followed by Western blotting with the affinity-purified monoclonal anti-Csx antibody (lanes 5 and 6, respectively). I.ppt, immunoprecipitation.

The homeodomain of Csx interacts with the zinc finger of GATA4.

To confirm the specificity of these protein-protein interactions and to identify the regions which are required for the physical interaction, in vitro protein binding assays were done with various deletion mutants of Csx. Four Csx mutants were transcribed and translated in vitro and labeled with [35S]Met (Fig. 2A). These Csx mutants were subjected to the “pull-down” assay with GST-GATA4 fusion protein coupled to Sepharose beads and subjected to SDS-PAGE. As shown in Fig. 2B, the wild-type 35S-Csx bound efficiently to GATA4 (lane 1). C-terminal deletion mutants of Csx (C1-230 and C1-199) retained their abilities to interact with GATA4 (lanes 2 and 3), although C1-199 seemed to bind less efficiently to GATA4 than full-length Csx or C1-230. It should be noted that the NK-2-specific domain (NK2-SD), conserved for most members of the NK-2 family (reviewed in reference 15), was deleted in C1-199. The mutant C1-182, in which a part of the homeodomain helix 3 was deleted, failed to bind GATA4 (lane 4). The importance of helix 3 was confirmed by the lack of binding with the mutant C1-148, in which more than half of the C-terminal homeodomain was deleted (lane 5). The protein-protein interaction of Csx was specific to GATA4, since Csx did not interact with GST protein (lane 6). These data demonstrated that the third helix of the homeodomain of Csx is necessary to interact with GATA4 in vitro. The NK2-SD domain is not required, although it may be important for efficient binding to GATA4. The loss of GATA4 protein binding ability in some deletion mutants did not seem to result from conformational changes due to large deletions, since the MBP fusion protein containing only the homeodomain of Csx (MBP-HD) bound to GATA4 as efficiently as the full-length MBP-Csx fusion protein did (data not shown). The results are summarized in Fig. 2C.

FIG. 2.

The homeodomain of Csx is required to interact with GATA4. (A) Various 35S-labeled Csx deletion mutants made by in vitro transcription and translation were confirmed by SDS-PAGE. (B) Equal amounts of 35S-Csx were incubated with 1 μg of GST-GATA4 fusion protein coupled to Sepharose (lanes 1 to 5) or GST beads (lane 6), and bound proteins were resolved on SDS-PAGE and autoradiographed. (C) The Csx deletion mutant protein structures and binding results are shown. HD, homeodomain; WT, wild type. a, binding activity of the MBP fusion protein containing only the homeodomain of Csx (MBP-HD) to GATA4 as described in the legend to Fig. 3B. b, binding activity of the Csx point mutant (Cpm) where Asn at position 10 of helix 3 was replaced by Gln (data not shown); an asterisk indicates the position of the point mutation.

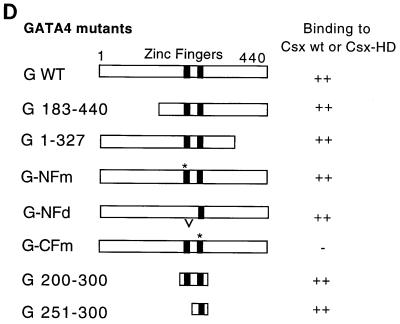

Converse experiments were performed to map the region in the GATA4 protein required for interaction with the Csx protein. Wild-type and various GATA4 mutants labeled with 35S were made by in vitro transcription and translation (Fig. 3A). These mutants were incubated with the MBP-Csx fusion protein coupled to the amylose resin, and bound proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 3B). Wild-type GATA4 bound efficiently to MBP-Csx (lane 1). Both N-terminal and C-terminal deletion mutants, G183-440 and G1-327, bound to Csx as efficiently as wild-type GATA4 did (lanes 2 and 3, respectively). Both N-terminal and C-terminal regions of GATA4 seem to be involved in the transactivation function (described below). GATA4 contains two zinc finger regions which are important for DNA-binding and/or protein interaction activities (reviewed in reference 11). The role of each zinc finger in binding Csx was examined by using several GATA4 zinc finger mutants, the N-terminal zinc finger point mutant and the deletion mutant (G-NFm and G-NFd, respectively), and the C-terminal zinc finger point mutant, G-CFm. All mutants but G-CFm bound to Csx (lanes 4 to 6), indicating that the C-terminal zinc finger is necessary to interact with Csx, whereas the N-terminal zinc finger is dispensable. The interaction of GATA4 was specific to Csx since GATA4 did not bind to MBP (lane 7). To confirm the role of the homeodomain of Csx, various GATA4 mutants were incubated with the MBP-HD fusion protein, which contains only the homeodomain of Csx; the same binding pattern as that of the full-length MBP-Csx was observed (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

The C-terminal zinc finger of GATA4 is required to interact with Csx. (A) Various GATA4 mutants labeled with [35S]Met were made by in vitro transcription and translation and resolved by SDS-PAGE. (B) The same amounts of 35S-GATA4 were incubated with the same amounts of MBP-Csx (lanes 1 to 6) or MBP-HD (data not shown) or MBP alone (lane 7). (C) The in vitro-translated and 35S-labeled GATA4 containing the entire zinc finger (amino acid positions 200 to 300) or C-terminal zinc finger (amino acid positions 251 to 300) fused to GAL4 DBD was resolved by SDS-PAGE (lanes 2 and 3, respectively). Lane 1 shows the control protein containing only GAL4 DBD. After these proteins were incubated with MBP-HD coupled to agarose beads, bound proteins were loaded onto an SDS-PAGE gel and autoradiographed (lanes 4 to 6): lane 4, GAL4 DBD alone; lane 5, the entire zinc finger fused to GAL4 DBD; lane 6, the C-terminal zinc finger fused to GAL4 DBD. (D) The structure of GATA4 and results are summarized. An asterisk indicates the position of the point mutation. wt, wild type.

To test whether the C-terminal zinc finger region is sufficient to interact with Csx, the zinc finger region fused to the GAL4 DBD (lanes 2 and 3) or GAL4 DBD alone (lane 1) was translated in vitro and then incubated with the MBP fusion protein containing only the homeodomain of Csx (MBP-HD) (Fig. 3C). Both the entire zinc finger (lane 5) and the C-terminal zinc finger regions (lane 6) interacted with the homeodomain of Csx. GAL4 DBD alone did not interact with Csx (lane 4), indicating the specific interaction between Csx and GATA4 proteins. The additional lower-molecular-weight band in lane 2 appeared to be GAL4 DBD produced by premature transcriptional or translational termination, which did not bind to Csx HD (lane 5).

These data indicate that the homeodomain of Csx is necessary and sufficient to interact with GATA4 protein and that the C-terminal zinc finger of GATA4 is necessary and sufficient to interact with Csx protein. The results are summarized in Fig. 3D.

DNA binding abilities of Csx and GATA4 are required for ANF gene activation.

The enhancer-promoter region of the ANF gene which confers cardiac muscle-specific expression contains several putative Csx binding sites (see Fig. 6). To examine the abilities of Csx mutants to transactivate ANF gene expression, transient-transfection assays were performed with 10T1/2 cells. The ANF reporter plasmid (−638/Luc) containing sequence up to bp −638 from the transcription initiation site of the enhancer-promoter region of ANF fused to the luciferase gene was cotransfected with Csx in the pcDNA3 expression vector. As shown in Fig. 4A, the ANF reporter gene cotransfected with Csx showed 66-fold-higher activation than the reporter gene alone (bars 1 and 2). C1-199, where the NK2-SD is deleted, transactivated the ANF gene fourfold more than the wild-type Csx did (bar 3) and 270-fold more than the ANF reporter gene alone did. It has been suggested that an inhibitory domain may reside in part across the NK2-SD, from amino acids 203 to 318 (7). A deletion mutant, C1-182, failed to transactivate the ANF gene (bar 4), probably due to the deletion of DNA recognition helix 3 in the homeodomain. A point mutant, Csxpm, in which asparagine at position 10 of helix 3 is replaced by glutamine, lost its ability to activate the ANF reporter gene (bar 5). Csxpm has been shown not to activate the reporter gene comprised of a synthetic target DNA sequence due to the loss of DNA-binding ability (7). The loss of transcriptional activities of Csx mutants was not due to a failure of nuclear localization, since Csx and its mutant proteins were detected in the nuclei of cells overexpressing each protein by immunostaining using anti-Csx polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies (data not shown). The activation profile of Csx mutants was examined by using a Csx-dependent reporter gene (A20/Luc) comprised of the synthetic Csx binding sites (7) linked to the heterologous simian virus 40 promoter. A similar activation profile was observed with the A20/Luc reporter gene (data not shown). These results demonstrate that Csx is a strong transactivator of ANF gene expression and that its activity depends on the DNA binding ability of Csx.

FIG. 6.

Characterization of GATA4 mutants containing mutations in the C-terminal zinc finger. (A) In vitro protein binding assays were performed as described above. 35S-labeled and in vitro-translated GATA4 wild type (Gwt) and several C-terminal zinc finger mutants (T, W, and E) (lanes 1 to 4) were incubated with MBP-HD coupled to agarose beads. Bound proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and autoradiographed (lanes 5 to 8). (B) Various GATA4 mutants with or without Csx were cotransfected with the ANF reporter gene into 10T1/2 cells. The transfection conditions are as described for Fig. 5A. Results are presented as a percentage of the ANF wild-type reporter activity when cotransfected with GATA4 wild type. Bars represent means + standard errors of the means from four separate transfections with triplicate plates.

FIG. 4.

Csx or GATA4 transactivates ANF gene expression. (A) The ANF reporter gene (−638/Luc), 4 μg, was cotransfected with 2 μg of wild-type or mutant Csx into pcDNA3 into 10T1/2 cells. (B) The ANF reporter gene (4 μg) was cotransfected with 2 μg of wild-type or mutant GATA4 in pMT2 into 10T1/2 cells. All cell culture dishes received 1 μg of murine sarcoma virus β-galactosidase. Luciferase activities were normalized to β-galactosidase activities. Relative luciferase activity was expressed as fold increase over that of the reporter gene alone (bar 1). Bars represent means + standard errors of the means of at least three separate transfection assays with duplicate plates.

The role of GATA4 in regulating ANF gene expression was examined in conjunction with Csx, since there are several consensus GATA4 DNA binding sequences close to the putative Csx binding sites located in the cardiac muscle-specific ANF enhancer/promoter region (see Fig. 6). When GATA4 in the pMT2 expression vector was cotransfected with the ANF reporter gene into 10T1/2 cells, the ANF gene showed 46-fold-higher activation than the reporter gene alone did (Fig. 4B, bars 1 and 2). Several GATA4 mutants were cotransfected with the ANF reporter gene to examine their transactivation capabilities. Deletion of the N-terminal region (G183-440) caused 85% reduction in the transactivation function of GATA4 (bar 3), and deletion of the C-terminal region (G1-327) caused a 56% reduction (bar 4). The marked reduction of the transactivation function of the N-terminal deletion mutants seems to be due to deletion of the transcriptional activation domain. The C-terminal region also seems to be involved in transactivation function. These results are consistent with a report of Morrisey et al. (35). G-NFm, a site-directed mutant in the N-terminal zinc finger (bar 5), showed slightly lower activation, by 20%, than that shown by the wild-type GATA4 (bar 2). G-NFm retains its ability to bind to its DNA target sequence (data not shown) and to the Csx protein (Fig. 3B). In contrast, G-CFm, which contains a site-directed mutation in the C-terminal zinc finger, minimally activated the ANF gene (Fig. 4B, bar 6), probably because of its inability to bind its DNA target sequence (data not shown). The C-terminal zinc finger has been shown to be sufficient for specific interaction with DNA target sequences (41, 42).

Thus, the DNA-binding ability of GATA4 is necessary to activate ANF gene expression. A similar activation pattern of GATA4 mutants was observed with a GATA/Luc reporter gene comprised of the duplicated GATA4 target sequence from the α-MHC gene (30) in front of the heterologous promoter, herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase (data not shown). These data, so far, indicate that either Csx or GATA4 alone activates ANF gene expression and that the DNA binding ability of each factor is required.

Csx synergistically activates ANF gene expression with GATA4.

To address the question of whether Csx and GATA4 function in a cooperative manner, the ANF reporter gene was cotransfected with Csx and GATA4 into 10T1/2 cells (Fig. 5A). When both factors were present (bar 4), the ANF gene was synergistically, or at least more than additively, activated (220-fold) in comparison to activation with either factor alone (bars 2 and 3). To examine the nature of the synergy, various Csx and GATA4 mutants were cotransfected with the ANF reporter gene. GATA4 and Csx mutants which fail to bind to the DNA target sequences, G-Cfm (bar 8), C1-182 (bar 10), and Cpm (bar 11), did not synergistically activate the ANF reporter gene. Cotransfection of Csx with the N-terminal (bar 5) or C-terminal (bar 6) deletion mutants of GATA4 or N-terminal zinc finger mutants (bar 7), which showed reduced transcriptional activity, resulted in at most additive effects but not synergy. Therefore, synergy was observed only when both factors retained full transcriptional activities.

FIG. 5.

Csx and GATA4 synergistically activate ANF gene expression. (A) The ANF reporter gene (4 μg) was cotransfected with various wild-type and mutant Csx/pcDNA3 and GATA4/pMT2 (2 μg each) into 10T1/2 cells. Luciferase values were normalized to β-galactosidase activities. Relative luciferase activity was expressed as fold increase over that of the reporter gene alone (bar 1). Bars represent means + standard errors of the means of three to six separate transfection assays with duplicate plates. (B) To examine the expression level of Csx and GATA4 proteins in various transfection conditions, Western blot analysis was performed with cells transfected with various plasmids as indicated in Fig. 5A. Whole-cell extracts prepared as described previously (26) were loaded onto an SDS-PAGE gel at 60 μg of protein per lane, and proteins on polyvinylidene difluoride membranes were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham). The extract numbers correspond to the bar numbers in Fig. 5A. The polyclonal Csx antiserum diluted 2,000-fold and affinity-purified GATA4 antibody (29a) diluted 1,500-fold were used to detect Csx and GATA4 proteins, respectively.

To confirm that the expression of one factor does not affect the levels of the other factor, Western blot analysis was performed with anti-Csx or anti-GATA4 polyclonal antibody (Fig. 5B). Whole-cell extracts were prepared from parallel cell culture dishes transfected as indicated for Fig. 5A. The level of Csx protein does not seem to be affected by GATA4 and vice versa. Therefore, the transcriptional activity of the ANF promoter seems to reflect the modulation of transcriptional function by two factors rather than changes in their protein expression levels.

In summary, the results indicate that the synergy requires both Csx and GATA4 to be transcriptionally active and to bind the target DNA sites. To address the question of whether the synergy requires the protein-protein interaction, site-directed mutations were introduced into the C-terminal zinc finger of GATA4 to generate a mutant(s) which loses protein interaction but retains transactivation as well as DNA binding functions. To construct the mutant TTT276SSS (T), the amino acids TTT at positions 276 to 278 were replaced by SSS. The mutants WRR280SSS (W) and EGE285SSS (E) contain the replacement of WRR at positions 280 to 282 by SSS and the replacement of EGE at positions 285 to 287 by SSS, respectively. These C-terminal zinc finger mutants were characterized for Csx binding (Fig. 6A), ANF promoter activation (Fig. 6B), and DNA binding activities (29a). The results are summarized in Table 1. To examine their Csx binding activities, in vitro protein binding assays were performed with 35S-labeled in vitro-translated wild-type and mutant GATA4 (Fig. 6A, lanes 1 to 4) and MBP-HD as described above. As shown in Fig. 6A, all three mutants, T, W, and E, failed to bind the Csx protein while the GATA4 wild type bound the Csx protein (lanes 5 to 8). The failure of Csx binding did not seem to be due to nonspecific conformational changes in the zinc finger, since the mutant NA283LL, in which two amino acids, NA, at positions 283 and 284 were replaced by LL, bound Csx (data not shown). Transient-transfection assays using the ANF reporter gene were performed to examine the transcriptional function of these mutants (Fig. 6B). The mutant T retained 45% transcriptional activity as compared to the wild-type GATA4 (bars 1 and 2). The mutants W and E failed to transactivate the ANF promoter (bars 3 and 4). To examine whether these mutants show synergy, Csx was cotransfected with the GATA4 mutants into 10T1/2 cells (Fig. 6B). None of the mutants exhibited as strong a synergy as wild-type GATA4 did (bars 6 to 9). Electrophoretic mobility shift assays were performed to examine DNA binding function by using in vitro-translated GATA4 proteins and the GATA4 DNA binding sequence. Two mutants, T and E, bound the DNA target sequence, but the mutant W did not (29) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Summary of functional characterization of C-terminal zinc finger GATA4 mutants

In summary, two mutants, T and E, that bound the DNA target sites but failed to bind Csx protein were identified. Interestingly, the mutant T, which retained transcriptional activity but failed to bind Csx, did not show synergy, suggesting that protein-protein interaction may be necessary for synergy. However, it is possible that the lack of synergy may be partly due to reduced transactivation function (Fig. 6B, bar 2). These data correlate well with the data from Fig. 5A, suggesting that synergy requires both factors to retain the full transactivation function and to bind the DNA and that the protein interaction seems to be required.

The functional DNA target sites of Csx and GATA4 in the ANF gene.

To identify the functional Csx and GATA4 DNA target sequences, several ANF point mutant reporter genes were generated in which the putative Csx or GATA4 binding sites were destroyed (Fig. 7A). The mutations were introduced into the two putative Csx binding sites homologous to the NK-2-like binding site (TNAAGTG) (−247 5′ CCTTTGAAGTGGGGGCCTCTTGAGGCAA 3′; the putative target sites located in tandem are underlined and the 3′ sequence in the antisense direction contains one nucleotide variation from the consensus site). These putative target sequences are conserved among different species, such as rats, humans, and mice, indicating the importance of these sequences. Transient-transfection assays were performed to examine the transcription profiles of ANF mutant promoters, and the data were presented as fold induction over transcriptional activity by each reporter gene alone (Fig. 7B). When ANFCm1 (mutation at position −231), ANFCm2 (mutation at −243), and ANFCm3 (mutations at both sites) were cotransfected with Csx, they showed 40, 17, and 60% lower (Fig. 7B, bars 6, 10, and 14, respectively) transcription activity than wild-type ANF did (bar 2). These ANF mutant promoters were still activated by Csx, suggesting that there may be other Csx functional target sites within the ANF promoter region. Indeed, another Csx target site was recently reported (8). These ANF mutants appeared to retain the abilities to respond to GATA4, like wild-type ANF (compare bars 7, 11, and 15 to bar 3).

FIG. 7.

The cis elements for Csx and GATA4 mediating ANF gene expression. (A) Diagram of several ANF mutant reporter plasmids containing mutations either in the putative Csx DNA binding sites (ANFCm1, ANFCm2, and ANFCm3) or in the GATA4 binding sites (ANFGm1 and ANFGm2). The locations of Csx or GATA4 binding sites are indicated by c or g, respectively, and x indicates the position of the mutation. (B) The mutant ANF reporter genes were cotransfected with Csx and/or GATA4 into 10T1/2 cells as described for Fig. 5A. Relative luciferase activity was expressed as fold induction over that of each reporter gene alone. Bars represent means of three separate transfection assays with duplicate plates. The standard error of the mean values were within 10% of the mean values.

The transcriptional activity of the mutated ANF promoters which contain site-directed mutations at the GATA4 consensus binding sites were examined. ANFGm1, in which the GATA4 consensus binding site was mutated at position −270, retained 60% of wild-type ANF activity when cotransfected with GATA4 (Fig. 7B, bars 3 and 19). In contrast, ANFGm2, mutated at the −122 GATA4 consensus binding site, was minimally (14% of wild-type level) activated by GATA4 (bar 23). The profiles of transactivation of these mutant ANF reporters by Csx did not significantly change from that of wild-type ANF (compare bars 18 and 22 to bar 2), although ANFGm1 showed a higher level of transactivation by Csx (bar 18). These results indicate that the GATA binding site at position −122 is the critical functional site for GATA4-dependent activation of ANF gene expression whereas the GATA4 binding site at −270 contributes to a smaller degree. It is unlikely that the remaining transcriptional activities of mutated ANF promoters may result from binding of each factor to the mutated DNA sequence, because mutations were introduced in such a way that they cannot function as binding sites.

To determine whether synergy would occur if the ANF reporter contained only GATA4 sites (mutated Csx sites) or Csx sites (mutated GATA4 sites), various mutant reporter genes were cotransfected into 10T1/2 cells with Csx and GATA4. All mutant ANF reporters showed mostly additive activation when Csx and GATA4 were coexpressed (Fig. 7B, bars 8, 12, 16, 20, and 24). This result suggests that all of the target sites of both factors need to be intact to exhibit the maximum synergy, again indicating that it is necessary for both factors to bind the DNA target sites. Because the mutation at one of the Csx or GATA4 DNA target sequences abolished synergy while these ANF mutant promoters were transactivated by Csx or GATA4, there seem to be cooperative interactions between the multiple Csx or GATA4 DNA target sequences, which leads to the maximum synergy of the ANF promoter.

DISCUSSION

The homeoprotein Csx plays an important role in early cardiac development. Csx is initially expressed in cardiac progenitors and the pharyngeal endoderm and is one of the earliest markers for the cardiogenic lineage in vertebrates. The targeted disruption of Csx in mice led to embryonic lethality due to abnormal cardiac looping morphogenesis, possibly as a result of abnormal ventricular muscle growth (29). The lack of a more severe phenotype, as observed for the heartless phenotype of the Drosophila tinman mutant, may be due to expression of another member of this family in the developing heart, which might partly compensate the function of Csx (see reviews in references 15 and 40), and/or to a more complex regulatory network governing the cardiogenic pathways in vertebrates. Therefore, the precise molecular mechanism of Csx function in cardiac muscle development and differentiation remains to be determined. The present study demonstrates that the Csx protein physically associates with the GATA4 protein in vitro and in vivo. Either Csx or GATA4 alone is a potent transcriptional activator of the ANF reporter. The activation of the ANF gene was further facilitated when Csx and GATA4 were coexpressed. This synergy may be explained at least in part by the protein-protein interaction between Csx and GATA4.

Possible direct or indirect downstream target genes of Csx have been suggested based on the reduced expression level of several genes in Csx-targeted mutant hearts, such as MLC2v (29), CARP (cardiac ankyrin repeat protein) (45), and eHAND (36). However, these alterations in expression level may not provide clear evidence that they are the downstream target genes of Csx. For instance, the expression of lacZ driven by the MLC2v promoter is strong in transgenic embryo hearts in a Csx-deficient background (37a). The reduced expression level of CARP and MLC2v in Csx-deficient mice does not correlate well with the demonstration that CARP inhibits expression of the MLC2v reporter gene (45).

Reporter gene analyses have suggested possible Csx target genes or possible modes of Csx action as a transcriptional activator. The recruitment of Csx by serum response factor resulted in synergistic activation of the cardiac α-actin gene, which did not require binding of Csx to DNA (7). The Nkx2.1 (TTF1) homeobox protein regulates the expression of a clara cell-specific gene by binding to cis elements, and Csx also regulates this gene in transfected cells through the same cis elements (37). The DNA binding sites for Csx have been identified by in vitro selection of DNA binding sequences from randomly generated oligonucleotides and grouped as high-affinity and weaker-affinity Csx DNA binding sites (6).

The first 700 bp of the ANF enhancer-promoter region has been shown to be sufficient to direct cardiac myocyte-specific expression of the ANF gene (2, 14, 21). Examination of this enhancer region reveals several putative Csx binding sites homologous to the in vitro-selected high-affinity Csx binding sequences (6) and consensus GATA4 DNA binding sites. Our transient-transfection assays indicate that Csx is a potent transcriptional activator of the ANF gene, as shown by 60-fold activation of the ANF promoter by Csx in nonmuscle cells. To identify the functional DNA target sequence of Csx, site-directed mutations were introduced between positions −243 and −221, where two putative Csx binding sites were located in tandem. The mutant ANF reporter gene activity decreased to 40% of the wild-type ANF when a mutation was introduced into both sites, indicating that this sequence is important for the Csx-mediated activation of the ANF gene. The residual 40% of the ANF activity might be mediated by the other Csx target site located between positions −94 and −78 (8).

GATA4, which has been previously demonstrated to regulate brain natriuretic factor expression, also activates ANF gene expression in nonmuscle cells to levels almost comparable to those activated by Csx. The critical GATA4 functional site was mapped to −122, although the other GATA4 consensus site, located at −270, also seems to be involved in GATA4-mediated activation; this is based on the result that the ANF reporter gene activity decreased to 14% of that of the wild-type ANF reporter gene when the GATA4 consensus site at −120 was mutated while the mutation at −270 decreased the ANF activity to 60% of that of wild type. It is not known how Csx and GATA4 interact over the distance that separates their two essential binding sites. The DNA binding of these proteins might result in DNA bending, which would allow the physical interactions between these two proteins to occur.

Throughout embryonic and fetal development, ANF expression characterizes both atrial and ventricular myocytes. However, the ANF gene is switched off in ventricular cells postnatally, whereas its level of expression remains high in atria, thus establishing the adult pattern of expression of this gene. The chamber-specific expression of the ANF gene in the adult heart cannot be explained solely by the function of Csx and GATA4, because both Csx and GATA4 are expressed throughout atria and ventricles. The reappearance of the ANF gene expression in hypertrophic ventricles might result, at least in part, from the increased binding activity of GATA4 to the DNA target sequence in pressure-overloaded hearts (18).

The physical interaction between Csx and GATA4 requires helix 3 of the homeodomain of Csx and the C-terminal zinc finger of GATA4, both of which directly contact the target DNA. The present study suggests that synergy of ANF gene activation requires both factors to be fully transcriptionally active and to bind to the DNA target sites. Whether physical association between Csx and GATA4 is necessary for this synergy could be directly addressed by constructing mutants that retain all abilities as transcription factors but that have lost their abilities to interact with each other. We have identified two mutants containing mutations in the C-terminal zinc finger, T and E, which have lost protein binding but retained DNA binding activity (see Table 1). One of the mutants, T, which retained DNA binding and transactivation function but lost protein interaction with Csx, failed to synergistically activate the ANF promoter. These data suggest that the protein interaction seems to be necessary for synergy. However, it is possible that the lack of synergy may be partly due to the reduced transcriptional activity of the mutant (45% of wild-type GATA4 activity).

It may be extremely difficult, if at all possible, to generate such mutants to fully test the requirement of protein interaction for synergy for the following reasons. First, the protein-protein interaction domains for both factors are mapped to the DBDs, where the DNA binding and protein-interactive surfaces are concentrated in a compact area. Second, the integrity of the DBD seems to be critical for the transcriptional activation function of GATA4, since all C-terminal zinc finger mutants tested so far failed to retain full transactivational function. Third, the protein-interactive surface appears to be distributed throughout the C-terminal zinc finger, since various C-terminal zinc finger GATA4 mutants lost their abilities to interact with Csx proteins. An overlapping of the function of the DNA binding region with protein-protein interaction sites has been demonstrated for MyoD and MEF2 (31) and for MEF2 and thyroid receptor interactions (27). It is possible that one of the reasons for a strong evolutionary conservation of DBD of transcription factors is that they also function as protein-protein interaction sites.

GATA4 is an activator of many cardiac contractile protein genes in vitro, suggesting that GATA4 may play an important role in specification and/or differentiation of cardiac myocytes. Targeted disruption of GATA4 in mice, however, demonstrated that GATA4 is required for the ventral folding morphogenesis of the embryo but not for specification or differentiation of cardiomyocytes (23, 32). GATA4 null embryos expressed ANF, MLC1A, and α-MHC genes normally, although these genes were thought to be GATA4 dependent based on in vitro experiments. The cardiac marker genes MLC2A, MLC2V, Csx, eHAND, and dHAND appeared to be expressed at normal levels in the mutant hearts. A potential explanation for these differences is that multiple isoforms of GATA4, such as GATA5 and GATA6, which are expressed early in the developing heart, might replace some function of GATA4. GATA5 and GATA6 bind the same DNA sequence as GATA4. In addition, GATA6 expression has been shown to be upregulated in the heart of GATA4 null mice. Alternatively, in the absence of one transcription factor, the presence of other types of transcription factors may be sufficient to activate the target genes, since multiple transcription factors seem to be involved in the regulatory network. As the present study suggests, Csx might be able to activate ANF gene expression to a certain degree in the absence of GATA4. Interestingly, ANF expression in the embryonic ventricular myocardium is abolished while it is maintained in the atrium of Csx null mice (40a). This observation further strengthens the notion that Csx plays an important role in ANF gene expression.

The Csx-GATA4 interaction reported in this study is the first example of homeoprotein and zinc finger protein interaction in vertebrates. Interaction between these two factors is especially intriguing because the cooperative interaction between homeobox and zinc finger proteins has been recently reported for the Drosophila homeodomain protein Ftz and zinc finger protein Ftz-F1 (12, 43). Just after this manuscript was completed, Durocher et al. (9) reported that Csx and GATA4 are mutual cofactors, which further substantiates our observations of a Csx and GATA4 interaction described here. Our study provides further insights into the regulatory mechanism of the cardiac muscle-restricted gene expression by cooperative interaction between transcription factors. The present study provides a more extensive examination of the nature of synergy by detailed site-directed mutational analyses of GATA4 as well as the ANF promoter. In addition, we clearly demonstrate that Csx or GATA4 alone is a strong activator of ANF gene expression. The interaction of homeobox proteins with other classes of transcription factors in the regulation of tissue-restricted gene expression may represent an important general mechanism of reinforcing the tissue-specific developmental pathway.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank K. Chien, R. Schwartz, C. Y. Chen, and D. Wilson for providing valuable reagents and T. Breyer for technical assistance. We thank G. E. Lyons for critically reading the manuscript.

This work was supported by an NIH grant to S.I. and grant HL 43662 to B.E.M.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arceci R J, King A A J, Simon M C, Orkin S H, Wilson D B. Mouse GATA-4: a retinoic acid-inducible GATA-binding transcription factor expressed in endodermally derived tissues and heart. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:2235–2246. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.4.2235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Argentin S, Ardati A, Tremblay S, Lihrmann I, Robitaille L, Drouin J, Nemer M. Developmental stage-specific regulation of artrial natriuretic factor gene transcription in cardiac cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:777–790. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.1.777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azpiazu N, Frasch M. Tinman and bagpipe: two homeobox genes that determine cell fates in the dorsal mesoderm of Drosophila. Genes Dev. 1993;7:1325–1340. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.7b.1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bodmer R, Jan L Y, Jan Y N. A new homeobox-containing gene, msh-2, is transiently expressed early during mesoderm formation of Drosophila. Development. 1990;110:661–669. doi: 10.1242/dev.110.3.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bodmer R. The gene tinman is required for specification of the heart and visceral muscles in Drosophila. Development. 1993;118:719–729. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.3.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen C Y, Schwartz R J. Identification of novel DNA binding targets and regulatory domains of a murine Tinman homeodomain factor, nkx-2.5. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:15628–15633. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.26.15628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen C Y, Schwartz R J. Recruitment of the Tinman homolog Nkx-2.5 by serum response factor activates cardiac α-actin gene transcription. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:6372–6384. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.11.6372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Durocher D, Chen C Y, Arditi A, Schwartz R, Nemer M. The artrial natriuretic factor promoter is a downstream target for Nkx-2.5 in the myocardium. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:4648–4655. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.9.4648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Durocher D, Charron F, Warren R, Schwartz R J, Nemer M. The cardiac transcription factors Nkx2.5 and GATA4 are mutual cofactors. EMBO J. 1997;16:5687–5696. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.18.5687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evans S M, Yan W, Murillo M P, Ponce J, Papalopulu N. Tinman, a Drosophila homeobox gene required for heart and visceral mesoderm specification, may be represented by a family of genes in vertebrates-xnkx-2.3, a second vertebrate homologue of tinman. Development. 1995;121:3889–3899. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.11.3889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evans T. Regulation of cardiac gene expression by GATA-4/5/6. Trends Card Med. 1997;7:75–83. doi: 10.1016/S1050-1738(97)00010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Florence B, Guichet A, Ephrussi A, Laughon A. Ftz-F1 is a cofactor in Ftz activation of the Drosophila engrailed gene. Development. 1997;124:839–847. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.4.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grepin C, Dagnino L, Robitaille L, Haberstroh L, Antakly T, Nemer M. A hormone-encoding gene identifies a pathway for cardiac but not skeletal muscle gene transcription. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:3115–3129. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.5.3115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris A N, Ruiz-Lozano P, Chen Y-F, Sionit P, Yu Y T, Lilly B, Olson E N, Chien K R. A novel A/T-rich element mediates ANF gene expression during cardiac myocyte hypertrophy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1997;29:515–525. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1996.0295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harvey R P. NK-2 homeobox genes and heart development. Dev Biol. 1996;178:203–216. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heikinheimo M, Scandrett J M, Wilson D B. Localization of transcription factor GATA4 to regions of the mouse embryo involved in cardiac development. Dev Biol. 1994;164:361–373. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hemsley A, Arnheim N, Toney M D, Cortopassi G, Galas D J. A simple method for site directed mutagenesis using polymerase chain reaction. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:6545–6551. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.16.6545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herzig T C, Jobe S M, Molkentin J D, Cowley A W, Jr, Markham B E. Angiotensin II type 1a receptor gene expression in the heart: AP-1 and GATA-4 participate in the response to pressure overload. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:7543–7548. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ip H S, Wilson D B, Heikinheimo M, Tang Z, Ting C-N, Simon M C, Leiden J M, Parmacek M S. The GATA4 transcription factor transactivates the cardiac muscle-specific troponin C promoter-enhancer in nonmuscle cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:7517–7526. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.11.7517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19a.Kasahara, H., S. Bartunkova, M. Schinke, M. Tanaka, and S. Izumo. Cardiac and extra-cardiac expression of Csx/Nkx2.5 homeodomain protein. Circ. Res., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Kelley C, Blumberg H, Zon L I, Evans T. GATA-4 is a novel transcription factor expressed in endocardium of the developing heart. Development. 1993;118:817–827. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.3.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knowlton K U, Baracchin E, Ross R S, Harris A N, Henderson S A, Evans S M, Glembotski C C, Chien K R. Coregulation of the atrial natriuretic factor and cardiac myosin light chain-2 genes during α-adrenergic stimulation of neonatal rat ventricular cells. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:7759–7768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Komuro I, Izumo S. Csx: a murine homeobox-containing gene specifically expressed in the developing heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:8145–8149. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.17.8145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuo C T, Morrisey E E, Anadappa R, Sigrist K, Lu M M, Parmacek M S, Soudais C, Leiden J M. GATA4 transcription factor is required for ventral morphogenesis and heart tube formation. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1048–1060. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.8.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laverriere A C, MacNeill C, Mueller C, Poelmann R E, Burch J B E, Evans T. GATA4/5/6, a subfamily of three transcription factors transcribed in developing heart and gut. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:23177–23184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee K H, Xu Q, Breitbart R E. A new tinman-related gene, nkx2.7, anticipates the expression of nkx2.5 and nkx2.3 in zebrafish heart and pharyngeal endoderm. Dev Biol. 1996;180:722–731. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee Y, Mahdavi V. The D domain of the thyroid hormone receptor α1 specifies positive and negative transcriptional regulation function. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:2021–2028. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee Y, Nadal-Ginard B, Mahdavi V, Izumo S. Myocyte-specific enhancer factor 2 and thyroid hormone receptor associate and synergistically activate the α-myosin heavy chain gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2745–2755. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.5.2745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27a.Lints T J, Parson L M, Hartley L, Lyons I, Harvey R. Nkx2.5: a novel murine homeobox gene expressed in early heart progenitor cells and their myogenic descendants. Development. 1993;119:419–431. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.2.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lyons G E. Vertebrate heart development. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1996;6:454–460. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(96)80067-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lyons L, Parson L M, Hartley L, Li R, Andrews J E, Robb L, Harvey R P. Myogenic and morphogenic defects in the heart tubes of murine embryos lacking the homeo box gene NKx2-5. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1654–1666. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.13.1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29a.Markham, B. Unpublished data.

- 29b.Markham, B., et al. Unpublished data.

- 30.Molkentin J D, Kalvakolanu D V, Markham B E. Transcription factor GATA-4 regulates cardiac muscle-specific expression of the α-myosin heavy chain gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:4947–4957. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.7.4947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Molkentin J D, Black B L, Martin J F, Olson E N. Cooperative activation of muscle gene expression by MEF2 and myogenic bHLH proteins. Cell. 1995;83:1125–1136. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90139-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Molkentin J D, Lin Q, Duncan S A, Olson E N. Requirement of the transcription factor GATA4 for heart tube formation and ventral morphogenesis. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1061–1072. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.8.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morrisey E E, Ip H S, Lu M M, Parmacek M S. GATA-6: a zinc finger transcription factor that is expressed in multiple cell lineages derived from lateral mesoderm. Dev Biol. 1996;177:309–322. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morrisey E E, Ip H S, Lu M M, Parmacek M S. GATA-5: a transcriptional activator expressed in a novel temporally and spatially-restricted pattern during embryonic development. Dev Biol. 1997;183:21–36. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.8485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morrisey E E, Ip H S, Tang Z, Parmacek M S. GATA-4 activates transcription via two novel domains that are conserved within the GATA-4/5/6 subfamily. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:8515–8524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.13.8515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Olson E N, Srivastava D. Molecular pathways controlling heart development. Science. 1996;272:671–676. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5262.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36a.Olson E N, Klein W H. bHLH factors in muscle development: dead lines and commitments, what to leave in and what to leave out. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1–8. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ray M K, Chen C-Y, Schwartz R J, DeMayo F J. Transcriptional regulation of a mouse clara cell-specific protein (mCC10) gene by the NKx transcription factor family members thyroid transcription factor 1 and cardiac muscle-specific homeobox protein (Csx) Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:2056–2064. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.5.2056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37a.Ross R S, Navankasattusas S, Harvey R P, Chien K R. An HF-1a/HF-1b/MEF2 combinatorial element confers cardiac ventricular specificity and establishes an anterior-posterior gradient of expression. Development. 1996;122:1799–1809. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.6.1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37b.Sartorelli V K, Webster K A, Kedes L. Muscle-specific expression for the cardiac α-actin gene requires MyoD1, CArG-box binding factor, and Sp1. Genes Dev. 1990;4:1811–1822. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.10.1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seidman C E, Wong D W, Harcho J A, Bloch K D, Seidman J G. Cis-acting sequences that modulate atrial natriuretic factor gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:4104–4108. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.11.4104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Simon M C. Gotta have GATA. Nat Genet. 1995;11:9–11. doi: 10.1038/ng0995-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tanaka, M., M. Schinkel, S. Bartunkoval, H. Kasahara, I. Komuro, H. Inagaki, M. Liu, Y. Lee, G. E. Lyons, and S. Izumo. Vertebrate homologs of tinman and bagpipe—roles of the homeobox genes in cardiovascular development. Dev. Genet., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40a.Tanaka, M., and S. Izumo. Unpublished observations.

- 41.Visvader J E, Crossley M, Hill J, Orkin S H, Adams J M. The C-terminal zinc finger of GATA-1 or GATA-2 is sufficient to induce megakaryocytic differentiation of an early myeloid cell line. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:634–641. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.2.634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang H-Y, Evans T. Distinct roles for the two cGATA-1 finger domains. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:4562–4570. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.10.4562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yu Y, Li W, Su K, Yussa M, Han W, Perrimon N, Pick L. The nuclear hormone receptor Ftz-F1 is a cofactor for the Drosophila homeodomain protein Ftz. Nature. 1997;385:552–555. doi: 10.1038/385552a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zou Y, Chien K R. EF1A/YB-1 is a component of cardiac HF-1a binding activity and positively regulates transcription of the myosin light chain-2v gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:2972–2982. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.6.2972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zou Y, Evans S, Chen J, Kuo H-C, Harvey R P, Chien K R. CARP, a cardiac ankyrin repeat protein, is downstream in the Nkx2-5 homeobox gene pathway. Development. 1997;124:793–804. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.4.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]