Abstract

The proteasome is a multisubunit protease responsible for degrading proteins conjugated to ubiquitin. The 670-kDa core particle of the proteasome contains the proteolytic active sites, which face an interior chamber within the particle and are thus protected from the cytoplasm. The entry of substrates into this chamber is thought to be governed by the regulatory particle of the proteasome, which covers the presumed channels leading into the interior of the core particle. We have resolved native yeast proteasomes into two electrophoretic variants and have shown that these represent core particles capped with one or two regulatory particles. To determine the subunit composition of the regulatory particle, yeast proteasomes were purified and analyzed by gradient sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Resolution of the individual polypeptides revealed 17 distinct proteins, whose identities were determined by amino acid sequence analysis. Six of the subunits have sequence features of ATPases (Rpt1 to Rpt6). Affinity chromatography was used to purify regulatory particles from various strains, each of which expressed one of the ATPases tagged with hexahistidine. In all cases, multiple untagged ATPases copurified, indicating that the ATPases assembled together into a heteromeric complex. Of the remaining 11 subunits that we have identified (Rpn1 to Rpn3 and Rpn5 to Rpn12), 8 are encoded by previously described genes and 3 are encoded by genes not previously characterized for yeasts. One of the previously unidentified subunits exhibits limited sequence similarity with deubiquitinating enzymes. Overall, regulatory particles from yeasts and mammals are remarkably similar, suggesting that the specific mechanistic features of the proteasome have been closely conserved over the course of evolution.

In eukaryotes, the elimination of many short-lived proteins requires their covalent attachment to ubiquitin (43). This pathway is involved in a wide variety of regulatory mechanisms, with substrates including cyclins and CDK inhibitors (49), membrane proteins such as CFTR (104), p53 (84), NF-κB (71), c-Fos, c-Jun, and luminal components of the endoplasmic reticulum (9). Multiubiquitin chains target proteins for degradation by the proteasome, an ∼2-MDa proteolytic complex (reviewed in references 12, 55, 61, and 80).

The mechanism of the proteasome is thought to involve unfolding of a protein substrate and translocation from one subcompartment of the enzyme to another prior to degradation. This model is based primarily on the crystal structure of the proteasomal core particle (CP). The CP has a barrel-like shape, with the proteolytic active sites facing the inner chamber, or lumen. In the proteasomal CP from Thermoplasma acidophilum, openings into the lumen are found only at the ends of the barrel (59) and are therefore thought to function as channels for the proteolytic substrate. Because these channels are narrow, it is likely that proteolytic substrates must be unfolded prior to entry into the lumen of the CP. Based on electron micrographs of the proteasome’s from various eukaryotes, these channels open out into multisubunit complexes flanking the CP at one or both ends; these complexes have been variously termed PA700, the μ particle, the 19S complex, and the regulatory particle (RP) (15, 72, 73, 99). As the RP confers ATP dependence and ubiquitin dependence on the CP (15, 47), it is presumed to function by recognizing substrates, unfolding them, and directing their translocation through the channel of the CP. The channel observed in the T. acidophilum particle, however, is not observed in the crystal structure of the CP from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (38). This fact suggests that in eukaryotes the channel is gated, perhaps through the action of the RP. Recent data also indicate that purified PA700, a mammalian RP complex, can deubiquitinate proteolytic substrates (53, 54). Because the subunit composition and crystal structure of the S. cerevisiae CP are known and because yeasts are amenable to genetic analysis, yeasts provide a useful system for studies of the proteasome and the role of the RP.

While the RP has been purified from mammals and most of its subunits have been identified, the RP of S. cerevisiae has not been characterized biochemically. However, many genetic screens have identified genes suggested to encode components of the RP. For example, such genes were identified in screens for mutations that are synthetically lethal in combination with cdc28 mutations (30, 50), mutations that suppress recessive alleles of GAL4 (94), mutations that increase the levels of expression of SEN1 fusion proteins (14), mutations that are deficient in the degradation of membrane-bound enzyme HMG-coenzyme A reductase (39), mutations that suppress phenotypes associated with a yme1 deletion mutation (8), and multicopy suppressors of the nin1-1 mutation (51). While the phenotypic effects of mutations in these genes are remarkably diverse, the paucity of biochemical information about the yeast proteasome has limited the mechanistic insights achievable through analyses of mutants. In this work, we have identified 17 subunits from the RP of the yeast proteasome by amino acid sequence analysis. Together with additional experiments examining the nature of electrophoretic variants of the proteasome, the assembly of multiple ATPases within a single RP, and deletion mutations of RP subunits, these studies define the components of the yeast RP and the complexes that they form.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains, media, and genetic techniques.

Chromosomal deletions of RP genes were performed with strain DF5 (MATa/MATα lys2-801/lys2-801 leu2-3,112/leu2-3,112 ura3-52/ura3-52 his3-Δ200/his3-Δ200 trp1-1/trp1-1) (24). Strain SUB62 (MATahis3-Δ200 lys2-801 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-52) (24) was used as a wild-type control, as all phenotypic analyses were carried out with MATa derivatives (31). Yeast cultures were grown at 30°C unless otherwise noted. YPD medium consisted of 1% yeast extract, 2% Bacto Peptone, and 2% glucose. Synthetic medium consisted of 0.7% Difco yeast nitrogen base supplemented with amino acids, uracil, and 2% glucose as described previously (77). Specific nutrients were omitted as necessary for plasmid selections. Standard techniques were used for yeast transformations and tetrad analysis (31, 77).

Construction of strains expressing His6-tagged ATPases.

A plasmid designed to express hexahistidine (His6)-tagged versions of the proteasomal ATPases from a single promoter was constructed. Northern blot analysis revealed that RPT1, RPT2, RPT3, RPT5, and RPT6 express comparable levels of RNA at both 30 and 37°C (data not shown). We therefore chose to express recombinant forms of these genes from a single plasmid containing the RPT1 promoter and a His6 epitope at the N terminus of the gene to be expressed. With a two-step PCR protocol (86), a DNA fragment containing the RPT1 5′-untranslated region, a multiple cloning site (MCS), and the RPT1 3′-untranslated region was created. In the first step, the oligonucleotide pairs DR27 (5′-CACTGCTTAAGCTTGTCGACTACCCGCCATTGTTGCAC)-DR29 (5′-CGACGACTGCAGTCGATCTC TAGATTTAATTAAATGGTGATGGTGATGGTGCATTCCGTATAGT TCCTAAC) and DR30 (5′-GATCGACTGCAGTCGTCGGGATCCCCCGGGTACCCATACGACGTCCCAGACTACGC)-DR31 (5′-CTCAGTGGTACCGTCGACGATTATTCCCAATGTCGGTC) were used to amplify DNA from pL44CIM5 (containing wild-type RPT1 [30]) to create two overlapping fragments. The first fragment contains 500 nucleotides immediately upstream of the start codon, and the second fragment contains 764 nucleotides immediately downstream. To fuse the fragments via the overlapping MCS, a second PCR with DR27 and DR31 was performed. The resulting fragment was digested with HindIII and KpnI and cloned into YCplac22, a yeast CEN4 shuttle vector marked with TRP1 (32); the resulting plasmid was called DP1. All six genes were then amplified by PCR and subcloned into the MCS.

Haploid cells containing a given rpt deletion covered by a URA3-marked CEN plasmid expressing the corresponding wild-type gene under the control of an RPT1 promoter were generated. Plasmids carrying tagged versions of the ATPase genes were introduced into these strains, and following 5-fluoro-orotic acid selection (77), the following strains were produced: DY17 (His6-RPT2), DY19 (His6-RPT1), DY40 (His6-RPT6), DY41 (His6-RPT3), and DY178 (His6-RPT5). These strains grow at wild-type rates. His6-RPT4 was expressed in a wild-type SUB62 haploid strain (DY196).

Deletion of RPN9.

A strain containing HIS3 in place of the complete RPN9 coding region was constructed. The transforming DNA fragment was generated by PCR as described previously (86); the HIS3 gene was amplified from a plasmid (yDpH) by use of a primer pair with base-pairing sites upstream and downstream of the RPN9 coding sequence: DR117 (5′-CAAAAAGCAAACAGTG GGCACACGCGAGGAAACCACATTATATTTCGCAAGCTCTTGGCCTC CTCTAGT)-DR118 (5′-TTTATATATATGTGTGCGTGTGTGTTTTATATATAACTGCCAATGGCCTATCGTTCAGAATGACACG). The resulting fragment contains the HIS3 gene and, at either end, the 5′ and 3′ sequences that flank the RPN9 coding sequence. This DNA fragment was transformed into strain DF5, and several transformants were sporulated. His+ segregants displayed a uniform slow-growth phenotype. MATarpn9::HIS3 (MG18) and MATα rpn9::HIS3 (MG19) segregants were isolated for subsequent studies. The site of integration was confirmed by PCR with a primer for the upstream untranslated region of RPN9 and a primer internal to HIS3: DR123 (5′-AGATCCAAGCTTCAAATTGAAAGATTGTCTATCAATCTGTA) and DR26 (5′-CTGTCATCTTTGCCTTCG). To construct a Δrpn9Δrpn10 double mutant, a MATarpn10::LEU2 strain (102) was mated with MG19. His+ segregants displayed a nearly uniform slow-growth phenotype. MATa haploids with histidine and leucine prototrophy were recovered (MG29).

Myc6 tagging of RPN9.

To create a plasmid carrying Myc6-Rpn9 under the control of its own promoter, genomic DNA from SUB62 was amplified with the following primers: DR123 (5′-AGATCCAAGCTTCAAATTGAAAGATTGTCTATCAATCTGTA) and DR116 (5′-GCTGTATCCCTAAACCCAGATGGATTGGCCA). The resulting fragment was cloned into a LEU2-marked CEN plasmid containing a downstream Myc6 sequence followed by a stop codon (pNU119). This plasmid was transformed into MG18 to generate strain MG26.

Purification of the proteasome by conventional chromatography.

Purification of the proteasome by conventional chromatography was modified from that described previously (79). The proteasome was purified from a yeast cell lysate by the protocol shown in Fig. 1. SUB62 was grown to the stationary phase on YPD in a 12-liter fermentor. After centrifugation, the cell pellet was resuspended in a threefold volume of buffer A, containing 50 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 5 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol, 1 mM ATP (grade 1; Sigma), and 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). For cell resuspension and lysis, buffer A was supplemented with an additional 4 mM ATP. Cells were lysed with a French press, and the extract was clarified by centrifugation at 30,000 × g for 20 min and passage through cheesecloth. The extract was fractionated on a 100-ml DEAE–Affi-Gel Blue column (Bio-Rad), followed by anion-exchange chromatography and gel filtration chromatography. Anion exchange was performed by use of an XK26 column packed with 50 ml of Resource Q resin (Pharmacia). Proteins were resolved on a 500-ml gradient of 100 to 500 mM NaCl at 4 ml/min. Fractions (8 ml) were collected and screened for the ability to hydrolyze Suc-LLVY-AMC (Bachem). Fractions containing the peak of activity, eluting at 270 to 330 mM NaCl, were pooled, desalted, concentrated to 1 ml by use of Ultrafree concentrators with a molecular weight cutoff of 30 kDa (Millipore), and further resolved by gel filtration. For gel filtration, 100 ml of S-400 resin (Pharmacia) was packed in an XK16 column. Samples were run isocratically in buffer A with 100 mM NaCl at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. Fractions (2 ml) were collected and screened for peptidase activity. Fractions from a broad peak of peptidase activity were pooled into separate aliquots (pools A to D).

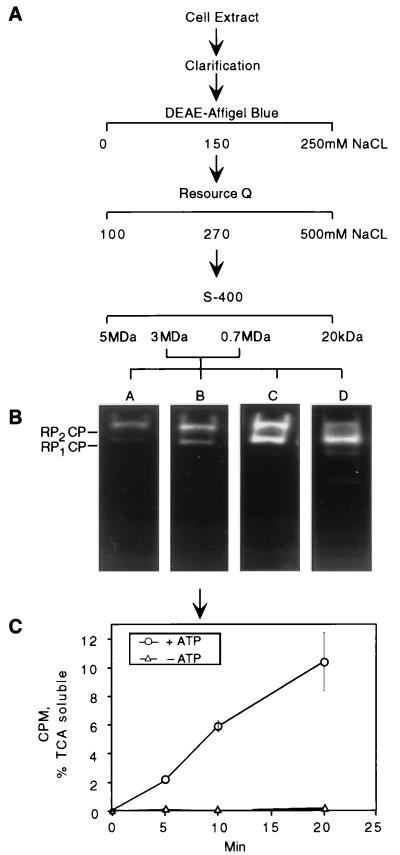

FIG. 1.

Proteasome purification procedure. (A) A yeast lysate was fractionated on a series of columns containing DEAE–Affi-Gel Blue, Resource Q resin, or S-400 resin (see Materials and Methods for details). Fractions containing peptidase activity were combined into four pools (A to D) in descending molecular mass order. Protein content and specific peptidase activity at each step are shown in Table 1. (B) Proteasomes from each pool were visualized by nondenaturing PAGE and fluorogenic peptide overlay. In pool D, two faster-migrating species were observed in addition to RP2CP and RP1CP. The fastest-migrating species was the CP, and the other contained the CP and a subset of RP subunits (data not shown). (C) Proteasomes from pool B were tested for the ability to proteolyse multiubiquitinated 125I-labeled lysozyme in the presence or absence of ATP. Degradation was measured as trichloroacetic acid-soluble 125I counts per minute at a given time point. Background radioactivity was subtracted from all readings. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

Assays of proteasome activity and concentration.

Aliquots from column fractions were incubated in buffer A with 0.1 mM Suc-LLVY-AMC for 10 min at 30°C. The reaction was quenched by the addition of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) to a final concentration of 1%. Fluorescence readings of released 7-amido-4-methylcoumarin (AMC) were taken at an excitation wavelength of 380 nm and an emission wavelength of 440 nm and were recorded as arbitrary (fluorescence) units per milligram of protein. Ubiquitin-lysozyme conjugate breakdown assays were performed essentially as described previously (79) by incubating proteasome with ubiquitinated, 125I-labeled lysozyme for 30 min and recording the trichloroacetic acid-soluble radioactivity released from the proteolysed substrate compared to the background. Protein concentrations in the different fractions were determined by using Coomassie Plus (Pierce) with bovine serum albumin as a standard.

Proteasome purification by Ni-NTA affinity chromatography.

Purification of the proteasome by Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) affinity chromatography was performed as described previously (79). Briefly, eluates from the DEAE–Affi-Gel Blue column were loaded onto Ni-NTA–agarose columns (Qiagen). Nonspecifically bound proteins were eluted with 100 mM NaCl and 15 mM imidazole in buffer A. His6-tagged proteasome was eluted with 100 mM NaCl and 100 mM imidazole in buffer A. Column fractions were tested for the presence of proteasomal subunits by immunoblotting with appropriate antibodies. Protein samples were also assayed for the ability to hydrolyze Suc-LLVY-AMC.

Ni-NTA affinity purification of the RP.

Purified proteasome preparations were dissociated to reveal uncapped CPs after incubation for 30 min at 30°C in buffer A without ATP and supplemented with 500 mM NaCl. Dissociation of the proteasome was confirmed by comparing the migration of the sample before and after NaCl incubation on nondenaturing polyacrylamide gels. Partial purification of the RP was performed by first-depleting cells of ATP; the cells were then incubated after harvesting in 1 volume of buffer A without ATP and supplemented with 0.2 nM dinitrobenzene and 200 mM deoxyglucose for 30 min at 30°C. Subsequent cell lysis and protein purification steps were performed in the absence of ATP. Clarified cell extract was applied to DEAE–CL-6B anion-exchange resin (Sigma), rinsed with 100 mM NaCl, and eluted with 500 mM NaCl in buffer A. Ni-NTA chromatography was performed as mentioned above for the intact proteasome but in the absence of ATP. Column fractions were tested for the presence of Rpt1, Rpt6, and Rpn10 by immunoblotting with specific antibodies.

Denaturing and nondenaturing PAGE.

Except for purposes of sequence analysis (see below), purified proteasome polypeptides were resolved by SDS–12% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) by standard techniques (52). Proteins were either stained in the gel with Coomassie blue or transferred to nitrocellulose for immunoblotting. For identification of proteins by immunoblotting, samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE and electrotransferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Whatman) with a semidry transfer system (Owl Scientific). Immunoblotting was performed with antisera to Rpn10 (generously provided by Steve van Nocker and Richard Vierstra) and to Rpt1 and Rpt6 (generously provided by Carl Mann). Primary antibodies were visualized with alkaline phosphatase-labeled goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulins (Promega) and the substrates nitroblue tetrazolium and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate (Promega).

Protein samples were resolved by nondenaturing PAGE by a modification of the method of Hoffman et al. (44). We used a single gel layer consisting of 0.18 M Tris-borate (pH 8.3), 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM ATP, 1 mM DTT, and 4% acrylamide-bisacrylamide (at a ratio of 37.5:1) and polymerized with 0.1% N,N,N′,N′-tetramethylethylenediamine (TEMED) and 0.1% ammonium persulfate. The running buffer was the same as the gel buffer but without acrylamide. Xylene cyanol was added to protein samples prior to loading onto the gels. Nondenaturing minigels were run at 100 to 150 mV until the Xylene cyanol eluted from the gels (approximately 2 h). The gels were then incubated in 10 ml of 0.1 mM Suc-LLVY-AMC in buffer A for 10 min. Proteasome bands were visualized upon exposure to UV light (360 nm) and photographed with a Polaroid camera.

For extracting intact proteasome from a gel, nondenaturing PAGE was performed as described above except that the usual cross-linker bisacrylamide mixture in the gel was replaced with the reversible cross-linker N,N′-bisacrylylcystamine (Bio-Rad). Gels containing 4% acrylamide–N,N′-bisacrylylcystamine at a ratio of 22:1 were polymerized with 0.1% TEMED and 0.1% ammonium persulfate. After the standard peptidase overlay assay, the proteolytically active bands were cut out of the gels and incubated with 40 μl of 2 M DTT per 100 μl of gel slice for 30 min at 30°C. Laemmli loading buffer (52) was added, and the samples were heated to 80°C for 3 min and loaded onto SDS-PAGE minigels. The gels were then stained with Coomassie blue, and the resulting protein banding pattern was quantitated by densitometry with NIH Image and LabGel software. The same methods were used for the quantitation of immunoblots.

Peptide sequence analysis.

Samples from different proteasome preparations, containing about 30 μg of purified protein, were precipitated with methanol-chloroform (105), denatured with SDS, reduced, and alkylated with iodoacetamide (96). Samples were then reprecipitated and resuspended in SDS-PAGE loading buffer (16) for resolution of subunits on an acrylamide gradient (10 to 20%) minigel (0.75 mm) with a standard Laemmli buffer system (52). No more than 10 μg of reduced and alkylated protein was loaded per gel lane to achieve acceptable resolution. After electrophoresis, the gel was stained with Coomassie blue and destained by standard protocols (25).

The Coomassie blue-stained subunits of the proteasome were cut from the gel with a scalpel, digested with trypsin in situ, and extracted as described previously (78). The extracts were concentrated under vacuum, resuspended in 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid, and fractionated by reverse-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) on a C18 column. Proteins were eluted with a gradient of acetonitrile containing 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid. The isolated peptides were sequenced by automated Edman degradation on a model 470/900/120A gas-phase sequencer (Applied Biosystems) with standard chemistry.

RESULTS

Purification and characterization of the proteasome.

The proteasome was purified from cell lysates by the protocol described in Fig. 1A and Table 1. In the final step of gel filtration, a broad peak of peptidase activity eluted between 3 and 0.7 MDa. Peak fractions were collected into four pools in descending molecular mass order as they eluted from the gel filtration column (pools A to D; Fig. 1B). The proteasome pools were active in the degradation of ubiquitin-protein conjugates in the presence of ATP (Fig. 1C and data not shown). Peptidase activity coincided with proteolytic activity, as assayed with ubiquitin-lysozyme conjugates (Fig. 1B and C and data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Proteasome purification procedure

Each pool was analyzed by nondenaturing PAGE, with proteasome bands visualized by their ability to hydrolyze the fluorogenic peptide Suc-LLVY-AMC (Fig. 1B). Two major electrophoretic bands whose relative abundance was characteristic from pool to pool were observed (Fig. 1B). Mammalian proteasome preparations have similarly been resolved into multiple forms by nondenaturing PAGE (44, 47, 100). To define the compositions of the two forms, they were resolved by nondenaturing PAGE, using a gel that had been polymerized with a reversible cross-linker, N,N′-bisacrylylcystamine. The two bands were excised, the gel matrix was dissolved, and the protein components of the particle were resolved by SDS-PAGE.

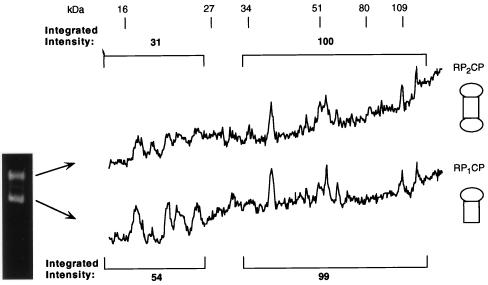

Similar polypeptide patterns were observed for the two electrophoretic forms of the proteasome (Fig. 2). The molecular masses of the CP subunits in yeast are all between 15 and 30 kDa (12), while most RP subunits are larger than 30 kDa (see below). We therefore compared the integrated intensity of the protein bands in the 30- to 120-kDa region to that in the 15- to 25-kDa region for the slower-migrating form of the proteasome and then compared this ratio to that for the faster-migrating form. The ratio of the integrated intensity of the RP subunits to that of the CP subunits for the slower-migrating form of the proteasome was approximately double that for the faster-migrating form (Fig. 2). The same results were obtained for the ratio of the cumulative intensity of all the RP bands to the cumulative intensity of all the CP bands and for the ratio of individual RP components to individual CP bands (Fig. 2). We conclude that the slowest-migrating form on nondenaturing PAGE represents doubly-capped proteasomes (RP2CP), that the faster-migrating form (of the two present in pool B) represents singly-capped proteasomes (RP1CP), and that the protein compositions of the two forms are otherwise equivalent. Electron micrographs confirmed the presence of dumbbell-shaped, doubly-capped proteasomes and mushroom-shaped, singly-capped proteasomes in these preparations (data not shown). Whether there are significant functional differences between singly- and doubly-capped forms of the proteasome is unknown.

FIG. 2.

The proteasome migrates as singly and doubly capped forms on nondenaturing PAGE. Purified proteasomes from pool B were resolved by nondenaturing PAGE with a reversible cross-linker, N,N′-bisacrylylcystamine. The fast- and slow-migrating forms were excised. Their proteins were extracted from the gels and resolved by SDS–12% PAGE. The gels were then stained with Coomassie blue. Densitometric quantitation of the resulting protein banding pattern is shown for each form. The protein banding pattern can be compared to that shown in Fig. 3 prior to nondenaturing PAGE. However, as the two gel systems are different, the comparison cannot be made on a one-to-one basis. Based on the data in Table 2 (and data not shown), proteins below 25 kDa were assumed to be CP subunits, and those above 30 kDa were assigned as be RP subunits. The integrated intensities of CP and RP subunits are displayed over the corresponding region of the gel. The ratio of intensity of RP subunits to that of CP subunits in the slower-migrating form of the proteasome is approximately double that in the faster-migrating form.

Subunit composition of the proteasome.

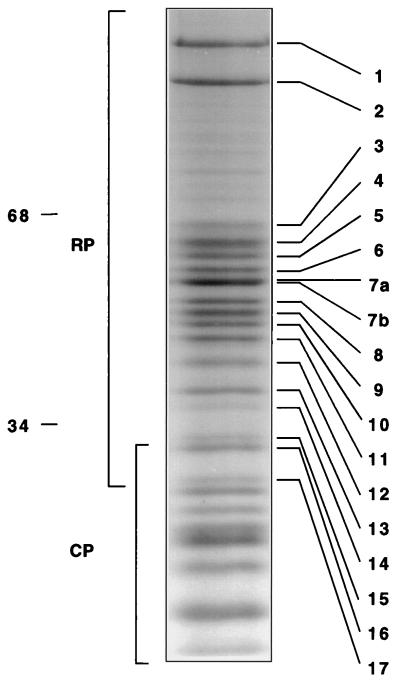

Amino acid sequence analysis was used to identify the subunits of the RP of the proteasome. Purified proteasomes were resolved by gradient SDS-PAGE, and the protein bands were stained with Coomassie blue (Fig. 3). The protein pattern in the 20- to 30-kDa region resembled that of independently purified CP (data not shown). Protein bands in the higher-molecular-mass region (30 to 120 kDa) with strong or intermediate staining intensities were numbered in descending molecular mass order from 1 to 17 (Fig. 3). The bands were excised from the gel and treated with trypsin. Representative peptides sequenced from each protein are shown in Table 2. The sequence of each peptide matched completely the deduced sequence from a yeast open reading frame (ORF) present in the SGD database, allowing the assignment of each protein as the product of a specific chromosomal locus (Table 2). Given that the S. cerevisiae genome is entirely known, the peptide sequence data are sufficient to assign each RP subunit as the product of a single gene. Although a few residues were not unambiguously assigned by the sequencer, no amino acid that was assigned differed from the corresponding yeast ORF-encoded sequence. In summary, seventeen RP proteins were resolved into 15 electrophoretic bands of comparable intensities (1 to 6, 8 to 15, and 17) and one more intense band (band 7), which contained peptides from two different RP subunits (Table 2). The RP proteins were named as follows: six of the proteins, which are putative ATPases of the AAA family (11), were designated Rpt1 to Rpt6 (for RP triple-A protein), and the other proteins were designated Rpn1 to Rpn12 (for RP non-ATPase). We note that the new nomenclature was arrived at in consultation with other yeast proteasome researchers and that nomenclatural conventions will be discussed in more detail in a separate communication.

FIG. 3.

Subunit composition of the proteasome determined by gradient SDS-PAGE. Proteins from pool B (Fig. 1) were resolved on a 10 to 20% polyacrylamide gradient gel. Protein bands were stained with Coomassie blue. Seventeen protein bands in the 120- to 30-kDa region were numbered in descending molecular mass order (masses are shown on the left). Proteins were excised from the gel and digested with trypsin. The resulting peptides were separated by reverse-phase HPLC and subjected to sequence analysis. Peptides sequenced from each band are shown in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Peptide sequences of RP subunits

| Band | Protein | Peptide sequencea | Chromosomal locusb | Residue no. | No. of matches to genomic sequencec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rpn1 | RLKEDDSSLYE | YHR027c | 55 | 11 |

| 2 | Rpn2 | KLALGIALEGYR | YIL075c | 151 | 12 |

| RYGGAFTIALAYA | 588 | 13 | |||

| 3 | Rpn3 | KFANQLXDEYL | YER021w | 566 | 10 |

| 4 | Rpt1d | RELFEMAR | YKL145w | 292 | 8 |

| KVMFATNRPNTLD | 350 | 13 | |||

| 5 | Rpt2 | KVAGENAPSIVFIDE | YDL007w | 269 | 15 |

| 6 | Rpt3 | RYVILQSDLEEAY | YDR394w | 399 | 13 |

| 7a | Rpt4 | REVIELPLK | YOR259c | 194 | 9 |

| RNCATEAGFFAIR | 392 | 13 | |||

| 7b | Rpt5 | KDSYLILDTLPSE | YOR117w | 150 | 13 |

| KLAAPQLVQMYI | 245 | 12 | |||

| 8 | Rpn5 | KSLDLNTR | YDL147w | 108 | 8 |

| KTYEPVLNEDDLA | 316 | 13 | |||

| RVIEXNLR | 344 | 7 | |||

| 9 | Rpn6 | KIMLNLIDDV | YDL097c | 269 | 10 |

| KIIEPFEXVEI | 349 | 10 | |||

| 10 | Rpn7 | KAFLLTQSK | YPR108w | 29 | 9 |

| RXADFFVR | 324 | 7 | |||

| 11 | Rpt6 | RLDILDPALLR | YGL048c | 296 | 11 |

| 12 | Rpn8 | RSIIAFDDLIENK | YOR261c | 283 | 13 |

| 13 | Rpn9 | RDLLDDLEK | YDR427w | 149 | 9 |

| KIPILAQHESF | 316 | 11 | |||

| 14e | Rpn10 | RVLSTFTAEFG | YHR200w | 60 | 10 |

| KLXMATALQI | 87 | 9 | |||

| 15 | Rpn11 | KVGSADTG | YFR004w | 12 | 8 |

| KXYDYEEK | 226 | 7 | |||

| 16 | Pre10f | PIPIPAFAD | YOR326c | 106 | 9 |

| 17 | Rpn12 | KNTELSYDFLP | YFR052w | 191 | 11 |

Bands were resolved by SDS-PAGE as shown in Fig. 3, excised from the gel, and digested with trypsin. Resulting peptides were separated by HPLC, and peptides were sequenced. Unassigned residues are indicated with an X. For details, see Materials and Methods.

Determined by a Blastp search of the yeast genome (GenBank) with the peptide sequence shown.

For all peptides that yielded high-confidence sequence data, assigned residues were in complete agreement with deduced amino acid sequences based on the DNA sequence of the yeast genome.

Five additional peptides were sequenced from this band; all were derived from Rpt1.

In some proteasome preparations, band 14 was contaminated with Cdc10 (see the text).

Pre10 is a CP subunit; therefore, the Rpt/Rpn notation does not apply.

Among bands 1 to 17, only one was found not to be an RP subunit; band 16 was identified as Pre10, a subunit of the CP (12, 43). Band 14 yielded peptides from two different proteins: Rpn10, which we have previously identified as Mcb1, a proteasome subunit that can bind multiubiquitin chains in vitro (102), and, in some preparations, Cdc10 (58). However, Cdc10 is not a component of the proteasome but rather is a substochiometric contaminant, since Cdc10 failed to comigrate with the proteasome upon nondenaturing PAGE, as determined by immunoblotting with anti-Cdc10 and anti-Rpt1 antibodies (data not shown). Also, in the final, gel filtration step of purification, Cdc10 peak fractions did not coincide with the proteasome peak.

Fujimuro et al. (27) recently showed that the Son1 protein cofractionates with the proteasome by gel filtration and that antibodies to Son1 precipitate proteasome subunits. Consistent with Son1 being a component of the proteasome, a subset of proteasome substrates were stabilized in son1 mutants (48). However, we were unable to detect Son1/Rpn4 in our purified proteasome preparation by direct sequencing or by using antibodies to Son1. Son1 homologs have not been found in purified mammalian proteasomes either. Unlike most proteasome subunits, Son1 is nonessential (69). It is perhaps a loosely associated component.

Characterization of novel RP subunits.

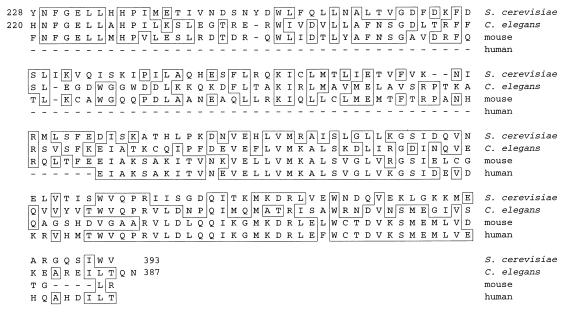

Table 3 lists the known subunits of the RP of the proteasome in yeast, their properties, and their homologs in other species. Two proteins did not have homologs previously identified as proteasomal subunits in other organisms: Rpn9 is encoded by ORF YDR427w, which has not been characterized, and Rpn11 is the product of the MPR1 gene. The mpr1 mutant was isolated as a suppressor of a defect in mitochondrial tRNA processing; deletion of the MPR1 gene is lethal (76). After submission of this manuscript, Rpn11 was identified as a subunit of human and Schizosaccharomyces pombe proteasomes (91). Like other Rpn subunits, Rpn9 has clear homologs in other species (Table 3 and Fig. 4). Rpn9 is 29% identical to a protein encoded by a hypothetical ORF in Caenorhabditis elegans (Fig. 4), and in various mammals there are expressed sequence tag (EST) fragments that are 42% identical to the C terminus of Rpn9 (Fig. 4). The Rpn9 homologs represented by these EST fragments are most likely RP subunits. An additional four of the non-ATPase subunits (Rpn5 to Rpn8), which have not been characterized biochemically in S. cerevisiae, are homologs of known mammalian subunits (Table 3). The RPN5/NAS5 and RPN6/NAS4 genes were recently found to be essential by Saito and colleagues (82). The six ATPases (Rpt1 to Rpt6), as well as Rpn1 to Rpn4, Rpn10, and Rpn12, were previously proposed to be RP subunits, with the nature of the evidence varying from case to case (Table 3 and references therein).

TABLE 3.

Subunit composition of the S. cerevisiae RP

| Band | Yeast

subunits

|

Homologs

|

% Yeast-human identityf | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proposed nomenclature | Existing nomenclature (or ORF)a | MMb | AAb | pIb | Humanc | Bovine and humand | Othere | ||

| 1 | Rpn1 | Hrd2/Nas1 | 109.4 | 993 | 4.32 | S2/Trap-2 | p97 | mts4 | 41 |

| 2 | Rpn2 | Sen3 | 104.3 | 945 | 5.92 | S1 | p112 | 41 | |

| 3 | Rpn3 | Sun2h | 60.4 | 523 | 5.37 | S3 | p58 | 21.5f | |

| Rpn4 | Son1/Ufd5i | 60.1 | 531 | 5.20 | |||||

| 4 | Rpt1 | Cim5/Yta3h | 52.0 | 467 | 5.32 | S7/Mss1 | 76 | ||

| 5 | Rpt2 | Yta5 | 48.8 | 437 | 5.78 | S4 | p56 | mts2 | 71 |

| 6 | Rpt3 | Yta2/Ynt1 | 48.0 | 428 | 5.38 | S6/Tbp7 | p48 | MS73 | 66 |

| 7a | Rpt4 | Crl13/Sug2/Pcs1 | 49.4 | 437 | 5.53 | S10b | p42 | CADp44 | 67 |

| 7b | Rpt5 | Yta1 | 48.2 | 434 | 4.93 | S6′/Tbp1 | 68 | ||

| 8 | Rpn5 | Nas5 | 51.8 | 445 | 5.79 | p55 | 40 | ||

| 9 | Rpn6 | Nas4 | 49.8 | 434 | 5.90 | S9 | p44.5 | 41 | |

| 10 | Rpn7 | ORF u32445 | 49.0 | 429 | 5.16 | S10 | p44 | 36 | |

| 11 | Rpt6 | Sug1/Cim3/Crl3h | 45.2 | 405 | 9.09 | S8/Trip1 | p45 | m56 | 74 |

| 12 | Rpn8 | ORF z75169 | 38.3 | 338 | 5.43 | S12 | p40 | Mov-34 | 47 |

| 13 | Rpn9 | ORF u33007 | 45.9 | 394 | 5.51 | dbESTg | 42g | ||

| 14 | Rpn10 | Mcb1/Sun1h | 29.7 | 268 | 4.73 | S5a | Mbp1/p54 | 34 | |

| 15 | Rpn11 | Mpr1 | 34.4 | 306 | 5.66 | Poh1 | pad1 | 65.5 | |

| 17 | Rpn12 | Nin1h | 31.9 | 274 | 4.8 | S14 | p31 | mts3 | 32 |

Existing nomenclature for S. cerevisiae in GenBank database [and reference(s)]: Nas1 (98), Hrd2 (39), Sen3 (14, 108), Sun2 (51), Cim5 (30, 85), Yta5 (85), Yta2 (85), Ynt1 (8), Crl13 (65), Sug2 (81), Pcs1 (66), Yta1 (85), Nas5 (82), Nas4 (82), (Sug1 (79, 94), Cim3 (30), Crl3 (29), Mcb1 (102), Sun1 (51), Mpr1 (76), and Nin1 (50). RP subunit genes that have not yet been named in yeast are designated by their ORF site in GenBank.

Molecular mass (MM) (in kilodaltons), number of amino acids (AA), and calculated pI were determined by use of the gene sequence and MegAlign (DNASTAR, Inc.).

Existing nomenclature in GenBank database [and reference(s)]: S1, S2, S3, S4, S6, S7, S8, S10, S12, and S14 (19–22); S9 (46); S6′ and S10b (75); S5a (17, 18); Trap-2 (6, 90); Tbp1 (68); Tbp7 (70); Mss1 (88); Trip1 (56); and Poh1 (91).

Existing nomenclature in GenBank [and reference(s)]: mts4 (106), mts3 and mts3 (87, 106), Mov-34 (37), Mbp1 (101), p54 (40), pad1 (89), MS73 (13), CADp44 (5), and m56 (92).

Homologies were determined with MegAlign by the Jotun Hein method (gap penalty, 11; gap length, 3), except for the Sun2/p58 homology, which was taken from reference 51.

See the text and the legend to Fig. 4 for details. The sequence was found in the dbEST database of the NCBI.

In addition to sequence analysis, the identities of these five bands were corroborated by immunoblotting with appropriate specific antibodies.

FIG. 4.

Rpn9 is homologous to putative proteasome subunits in other eukaryotes. Homology of the C terminus of Rpn9 to deduced protein sequences of the product of a hypothetical ORF in C. elegans (z49130) and mouse (w34049) and human (aa122133) EST fragments is shown. The alignment was obtained by the Jotun Hein method with MegAlign (gap penalty, 11; gap length, 3). The C terminus of Rpn9 was 35, 36, and 42% identical to the C. elegans, mouse, and human sequences, respectively. Boxes indicate amino acid identities; dashes indicate gaps in the alignment.

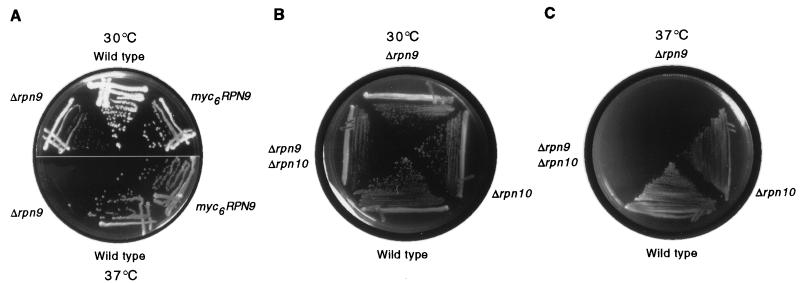

A precise deletion of the rpn9 coding sequence resulted in a slow-growth defect at 30°C (Fig. 5). After 48 h at 37°C, Δrpn9 mutants failed to form colonies. In a large-scale analysis of expressed genes in S. cerevisiae, the ORF corresponding to RPN9 was reported to be nonessential (7). RPN9 is apparently the only proteasome subunit gene that confers a temperature-sensitive phenotype when deleted, although this phenotype has been observed for point mutations in a number of other subunits. Temperature-sensitive phenotypes have been observed for rpn1 and rpn2 disruptions (98, 108), but complete deletions of these genes appear to be lethal (14, 54a, 57a). Aside from RPN9, the only other RP genes that are known to be nonessential are RPN10/MCB1 (102) and RPN4/SON1 (27). Δrpn9Δrpn10 double mutants did not display a marked synthetic phenotype for vegetative growth (Fig. 5B and C).

FIG. 5.

Temperature-sensitive phenotype caused by Δrpn9 deletion mutation. (A) Wild-type (SUB62), myc6-RPN9 (MG26), and Δrpn9 (MG18) strains were grown on YPD at 30°C (top panel) or 37°C (bottom panel). The Δrpn9 strain was temperature sensitive, showing no detectable growth after 48 h at 37°C. (After 1 week, a few small colonies were observed.) The myc6-tagged version of RPN9 fully complemented the deletion. (B and C) The Δrpn9Δrpn10 double mutant did not display a marked synthetic phenotype. Wild-type (SUB62), Δrpn9 (MG18), Δrpn10 (102), and Δrpn9Δrpn10 double mutant (MG29) strains were grown for 48 h on YPD at either 30°C (B) or 37°C (C).

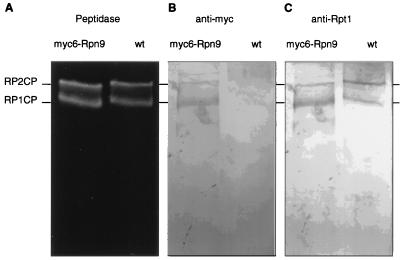

To confirm that Rpn9 is a subunit of the proteasome, Rpn9 was tagged at its C terminus with six copies of the Myc epitope. Expression of tagged Rpn9 in a Δrpn9 mutant background resulted in full complementation (Fig. 5A). Proteasomes from wild-type and myc6-RPN9 strains were partially purified on a DEAE–Affi-Gel Blue column and further resolved by nondenaturing gel electrophoresis. The gel was immunoblotted, and the filter was probed with anti-Myc antibodies. Two bands which comigrated with singly- and doubly-capped proteasomes were detected (Fig. 6). We conclude that Rpn9 is a subunit of the proteasome.

FIG. 6.

Rpn9 is an RP subunit. Proteasomes from wild-type (wt) and myc6-RPN9 strains were partially purified on a DEAE–Affi-Gel Blue column and further resolved by nondenaturing PAGE. (A) Proteasome bands visualized in situ by peptidase activity against Suc-LLVY-AMC. (B and C) Immunoblots probed with the indicated antibodies.

Interestingly, Rpn11/Mpr1 contains a single conserved cysteine which is flanked by a highly conserved sequence with similarities to the active-site “Cys box” seen in many deubiquitinating enzymes (Tables 4 and 5). The catalytic triad of many deubiquitinating enzymes is thought to be made up of a nucleophile (Cys), a general base (His), and an acidic residue (Asp) (4, 23, 107). In Rpn11, a number of conserved aspartates and histidines are present downstream of the conserved Cys box and could potentially serve these functions.

TABLE 4.

Alignment of Rpn11 to the conserved active-site cysteine in Ubp enzymes

| Protein | GenBank accession no. | Cys boxa |

|---|---|---|

| Rpn11 | X79561/P43588 | 113 GFGCWLSSV 121 |

| hUBP3 | Q92995 | 343 GNSCYLSSV 350 |

| yUBP14 | P38237 | 351 GNSCYLNSV 359 |

| hIsoT | U35116 | 332 GNSCYLNSV 340 |

| yUBP8 | P50102 | 143 GSTCFMSSI 151 |

| yUBP2 | Q01476 | 742 GNTCYLNSL 750 |

The putative active-site cysteine is marked in boldface.

TABLE 5.

Conservation of putative Cys boxes of Rpn11 homologs

| Group | Species | Locus or named | Cys boxa | Total amino acids | % Identity to Rpn11b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ic | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | YFR004w (Rpn11) | 104 VVGWYHSHPGFGCWLSSVDVNTQ 126 | 306 | 100 |

| Caenorhabditis elegans | U00032 | 106 ----------------------- 128 | 319 | 52 | |

| Discoides discoideum | U96916 | 108 -I--------------------- 130 | 306 | 58 | |

| Schizosaccharomyces pombe | D31731 (pad1) | 107 -----N-------------I--- 129 | 308 | 64 | |

| Homo sapiens | U86782 (Poh1) | 108 ----------------G--I--- 130 | 310 | 65 | |

| Mus musculus | Y13071 | 107 ----------------G--I--- 129 | 309 | 65 | |

| S. mansoni | AF014465 | 111 ----------------G--M--- 133 | 313 | 65 | |

| IIc | C. elegans | U80814 | 134 ----------Y-----GI--S-- 156 | 368 | 27 |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | AF000657 | 137 ----------Y-----GI--S-- 159 | 357 | 29 | |

| H. sapiens | U70734 (Jab1) | 133 AI--------Y-----GI--S-- 155 | 334 | 29 | |

| M. musculus | U70736 | 133 AI--------Y-----GI--S-- 155 | 334 | 29 | |

| S. cerevisiae | YDL216c (Z74264) | 174 ----F-----YD----NI-IQ-- 196 | 455 | 23 |

The putative active-site cysteine is marked in boldface. Dashes represent identities to Rpn11.

The identity of the product of each hypothetical ORF to Rpn11 was determined by the Jotun Hein method (gap penalty, 11; gap length, 3) with MegAlign. The identity within the putative Cys box was greater than that over the entire ORF.

A pairwise comparison of all proteins indicated that the proteasomal subunits in group I were 52 to 65% identical to each other. Similarly, putative members of group II from different phyla were up to 60% identical to each other. Identity between proteins from different groups was slightly less than 30%.

Evolutionary conservation of RP subunits.

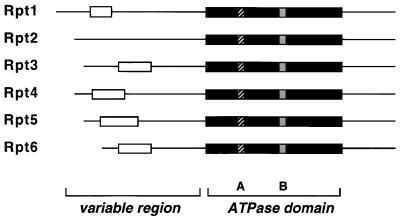

All RP subunits identified in the purified preparation from yeast (Fig. 3) have clear homologs in other eukaryotes (Table 3). The Rpt subfamily of putative ATPases shows a greater degree of homology between species than the Rpn subunits (Fig. 7). The Rpt subunits are 66 to 76% identical between yeasts and humans, whereas the non-ATPase subunits show a lower yet significant amount of sequence identity, varying between 22 and 47% between species. Alone among the Rpn subunits, Rpn11 is 65% identical to its human counterpart, a level of identity similar to that observed for the ATPase subunits, consistent with the suggestion above that it could serve an enzymatic function within the RP.

FIG. 7.

Structural alignment of six proteasomal ATPases. Comparison of the six Rpt subunits based on their primary structure shows a highly conserved ATPase module (black box) containing the A and B loops which form the predicted ATP binding domain (33, 34, 67, 103). The N termini are variable, in some genes containing a predicted (62) coiled-coil domain (open box).

A number of RP subunits show homology to each other. The six ATPase subunits (Rpt1 to Rpt6) are roughly 40% identical to each other. Among the non-ATPase subunits, three pairs show close to 20% identity to each other: Rpn1 with Rpn2 (6, 60), Rpn5 with Rpn7, and Rpn8 with Rpn11. The same relationship is maintained among their mammalian counterparts. Despite the similarity between Rpn11 and Rpn8, Rpn8 lacks candidates for a conserved active-site cysteine. However, another set of homologous proteins with a greater level of identity to Rpn11 (∼30%) is found in numerous eukaryotes and contains the Cys consensus region (Table 5, group II). There is no evidence that these proteins are proteasome subunits; however, the significant level of homology to both Rpn11 and Rpn8 suggests that they might play a role in the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. The sequence similarities among different Rpt and Rpn subunits raises the possibility that gene duplication played a major role in the evolution of the RP. The RP subunits may have diverged from a small number of subunits in an evolutionary precursor to the proteasome, similar to the apparent divergence of the 14 subunits of the CP from two precursors (12, 43).

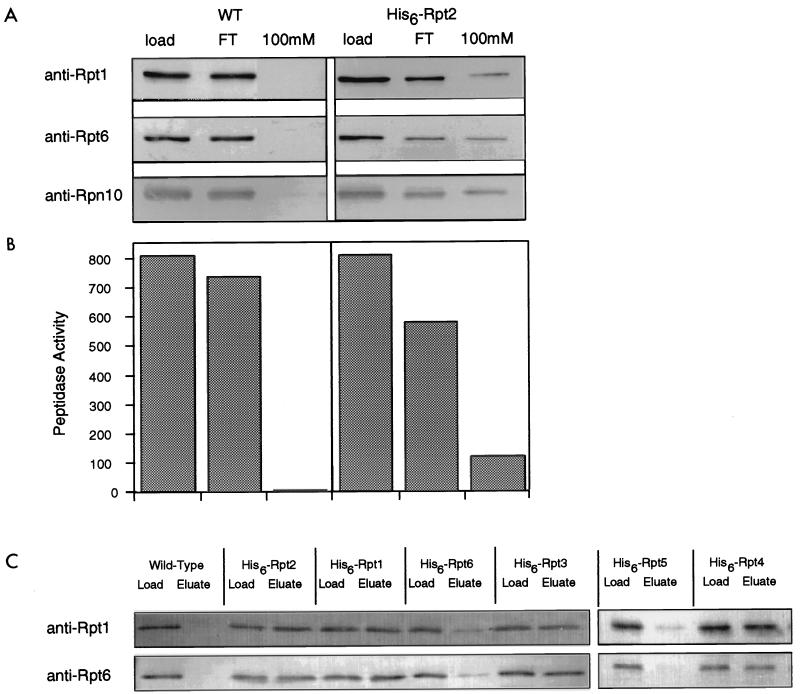

Coassembly of Rpt subunits within the proteasome.

The ATPase subunits of the RP are distinct from the non-ATPase subunits in that they show a high level of similarity to one another (Fig. 7). This fact raises the question of whether interchangeability among the ATPases during assembly may yield proteasomes with different subunit compositions and functional properties, as suggested, for example, by studies with Manduca sexta (13, 95). In Escherichia coli, the ClpP protease can assemble with multiple ATPase-containing RPs, but each ATPase is found in a different, homomeric assembly (36). In vitro, the mammalian proteasomal ATPases can interact in a pairwise manner, but assemblies of more than two ATPases have not been observed in such experiments (75). We tested whether multiple Rpt subunits are present in the same proteasome molecule by using Ni-NTA–chelate affinity chromatography of proteasomes bearing His6-tagged Rpt subunits. Wild-type and His6-Rpt2-containing proteasomes were partially purified on DEAE–Affi-Gel Blue columns and then affinity purified with Ni-NTA. The presence of proteasomes in the His6-Rpt2 eluate was shown by peptidase activity as well as the copurification of multiple proteasome subunits (Fig. 8A and B). Importantly, during affinity purification, the ratios of Rpt1 to Rpt6 in the column load, flowthrough, and eluate remained essentially constant (1.35, 1.35, and 1.25, respectively; Fig. 8A), indicating that the purification procedure did not select a specific subset of proteasomes. Thus, Rpt1 and Rpt6 are both present in Rpt2-containing proteasomes, and the ratio of Rpt1 to Rpt6 in Rpt2-containing proteasomes is indistinguishable from that in total proteasomes. Similar experiments were done with strains expressing His6-tagged versions of all six ATPases (Fig. 8C). Tagging of Rpt1, Rpt2, Rpt3, or Rpt4 allowed affinity purification of proteasomes without significantly altering the relative ratios of Rpt1 and Rpt6 in the column load and eluate (Fig. 8C). These data demonstrated that an individual proteasome contains multiple ATPases and that affinity purification of proteasomes from individually tagged ATPases yields proteasomes with similar compositions. The difficulty in purifying intact proteasomes from His6-Rpt5- and His6-Rpt6-expressing strains with Ni-NTA was probably due to the His6 tag being occluded when the RP was complexed to the CP (see below).

FIG. 8.

The proteasome is a heteromeric complex of ATPases. His6-Rpt2 was expressed in a Δrpt2 background (DY17). Extracts from His6-Rpt2-expressing and wild-type (WT) control strains were partially purified by DEAE–Affi-Gel Blue chromatography in the presence of 1 mM Mg-ATP. The 150 mM NaCl eluate was subjected to Ni-NTA affinity chromatography. Column fractions were immunoblotted (A) and tested for peptidase activity against Suc-LLVY-AMC (B). The epitope-tagged complex eluted at 100 mM imidazole, as indicated by immunoblotting against Rpt1, Rpt6, and Rpn10 (A) and by peptidase activity (B). The wild-type proteasome eluted during low-imidazole rinses. (C) Extracts from strains expressing His6-tagged versions of each of the six ATPases were individually purified by Ni-NTA chromatography. Fractions loaded onto the Ni-NTA column (Load) were compared to fractions from the 100 mM imidazole eluate (Eluate) by immunoblotting with anti-Rpt1 and anti-Rpt6 antibodies.

Because the proteasome can contain one or two RPs (Fig. 3 and 4), different ATPases may copurify even though they are not present in the same RP complex. To test whether distinct ATPases assembled into a single RP, we found conditions in which the RP can be dissociated from the CP (Fig. 9). The CP is visualized as a faster-migrating complex on nondenaturing PAGE after dissociation of the proteasome components in the absence of ATP (Fig. 9A). The peptidase activity of the proteasome is greater by 1 order of magnitude than that of the CP alone (Fig. 9B). However, the peptidase activity of the CP is stimulated by SDS to levels similar to that of the proteasome holoenzyme (Fig. 9B).

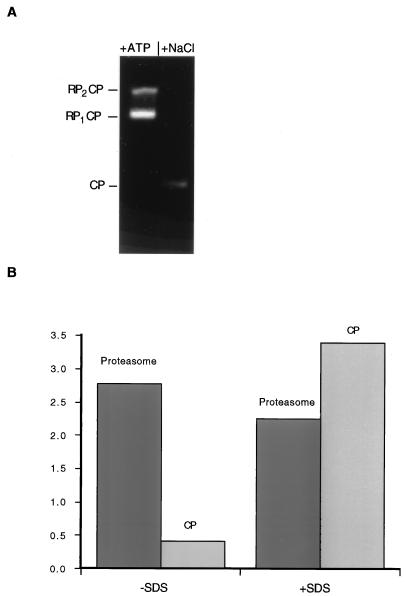

FIG. 9.

Dissociation of the RP from the CP inhibits peptidase activity. Equal amounts of purified proteasome were incubated for 30 min at 30°C in buffer A or in buffer A without Mg-ATP but with 500 mM NaCl. (A) The two samples were resolved by nondenaturing PAGE and visualized by activity against the fluorogenic peptide substrate Suc-LLVY-AMC. After incubation in 500 mM NaCl, both singly- and doubly-capped forms of the proteasome (RP2CP and RP1CP, respectively; left lane) disassembled, giving rise to free CPs (right lane). It is apparent that the CP had lower peptidase activity than the proteasome on a molar level. The RP was not visualized by this method, as it contains no intrinsic peptidase activity. (B) To quantify the difference in peptidase activities between the proteasome and the CP, approximately equimolar quantities of the two samples were incubated for 10 min at 30°C in buffer A with 0.1 mM fluorogenic peptide Suc-LLVY-AMC; the fluorescence of released AMC is shown in the left columns. The two samples were also incubated for 10 min at 30°C in buffer A with 0.1 mM Suc-LLVY-AMC and 0.02% SDS (right columns). The CP exhibited a lower level of peptidase activity and a higher level of SDS stimulation than the intact proteasome.

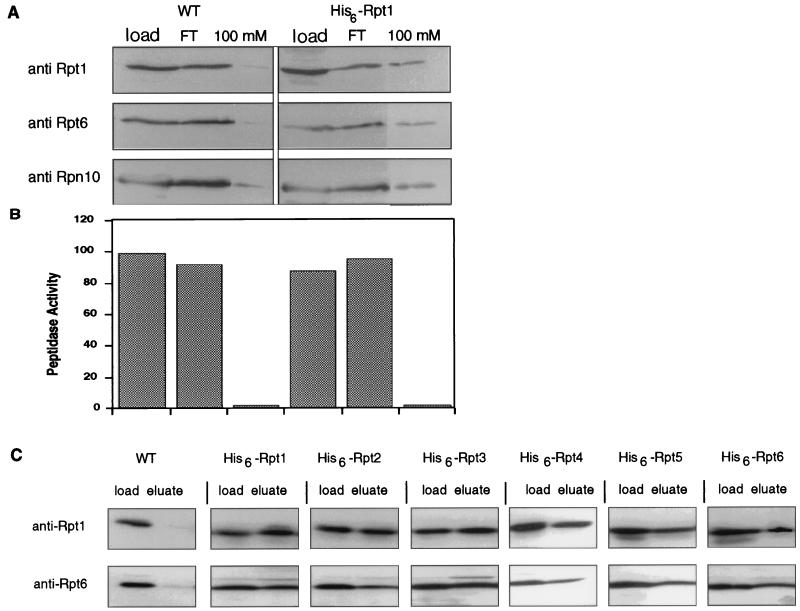

Components of the RP were affinity purified after dissociation from the CP; column profiles of wild-type and His6-Rpt1-expressing strains are shown in Fig. 10A and B. By tagging Rpt1 with His6 we purified a complex that contained Rpt6 and Rpn10, as shown by immunoblotting of the column fractions (Fig. 10A). That the CP was not retained on the column was shown by the absence of peptidase activity in the eluate (Fig. 10B). The ratios of Rpt1 to Rpt6 in the column load, flowthrough, and eluate remained essentially constant for the His6-Rpt1-containing cell extract (1.25, 1.40, and 1.20, respectively; Fig. 10A), indicating that the purification procedure did not select a specific subset of RPs. Indistinguishable results were obtained for His6-tagged versions of each Rpt subunit (Fig. 10C). Thus, each Rpt subunit coassembles with multiple Rpt subunits into complexes with similar ratios of Rpt1 to Rpt6. These data strongly suggest that each RP contains all six ATPases.

FIG. 10.

Proteasomal ATPases associate into a heteromeric complex. His6-Rpt1 was expressed in a Δrpt1 background (DY19). Extracts from His6-Rpt1-expressing and wild-type (WT) control strains were partially purified on DEAE–CL-6B resin in the absence of ATP. The 500 mM NaCl eluate was fractionated on Ni-NTA affinity columns. Column fractions were subjected to immunoblotting (A) and tested for peptidase activity against Suc-LLVY-AMC (B). The epitope-tagged complex eluting at 100 mM imidazole contained a number of RP subunits (Rpt1, Rpt6, and Rpn10) (A) but lacked peptidase activity (B). The wild-type complex eluted during low-imidazole rinses. (C) Extracts from strains expressing His6-tagged versions of each of the six ATPases were also purified by Ni-NTA chromatography. Fractions loaded onto the Ni-NTA column (Load) were compared to fractions from the 100 mM imidazole eluate (Eluate) by immunoblotting with anti-Rpt1 and anti-Rpt6 antibodies.

DISCUSSION

Previous work on the proteasome of S. cerevisiae focused on the CP, culminating in the solution of its crystal structure (38). However, CPs fail to degrade physiological substrates of the proteasome, and their activity is not stimulated by ubiquitin or ATP. Thus, substrate selection and other key early steps in protein breakdown by the proteasome must be studied with the holoenzyme form of the complex. Here we report the biochemical characterization of the proteasome holoenzyme from S. cerevisiae. By amino acid sequence analysis, we directly identified 17 subunits that form the RP of the yeast proteasome. Genes encoding a number of these subunits or their homologs were originally identified through a wide variety of genetic screens (8, 14, 30, 35, 39, 50, 51, 76, 89, 94), only a few of which were designed to detect proteolysis mutants (14, 39). These data point to the breadth of the regulatory functions of the proteasome. The assembly of these proteins into the same complex provides a common explanation for the disparate and in many cases unexpected phenotypes. These genetic studies also suggest that substrate-specific effects on protein turnover can result from mutations in any of a large number of RP subunit genes, a suggestion which has interesting mechanistic implications.

Of the known mammalian RP subunits, only S5b/p50.5 (17, 18) appears absent from yeast. We found no evidence for an S5b homolog in purified yeast proteasomes; in agreement with this result, no clear S5b homologs are identifiable in the yeast genome database. Our survey of yeast proteasome components also did not identify proteins homologous to the proteasome activator PA28 (63), a result which is similarly supported by the lack of close PA28 homologs in the yeast genome. Yeast proteasomes appear to be more uniform than those of mammals in several ways: they do not appear to associate with PA28-like activator proteins that can replace the RP complex, and each of the 32 known subunits is apparently encoded by a single gene. The heterogeneity of the mammalian proteasome appears to regulate the nature of peptide end products of degradation rather than substrate selection and may be linked to the role of the proteasome in antigen processing (12). The relevance of subunit interchangeability to antigen processing is best exemplified by the LMP proteins, which interchange with other proteolytically active β subunits of the CP to alter the cleavage site specificity of the proteasome (12).

Possible interchangeability among the ATPases is suggested both by their strong sequence similarity to one another and by evidence that the ratio of one ATPase to another in the proteasome may change during the course of programmed cell death in M. sexta, with possible replacement of one ATPase subunit for another (13, 95). The simplest model for interchangeability among the ATPases, which has a precedent in prokaryotic ATP-dependent proteases (36), is that each RP contains a single type of ATPase and thus that the various ATPases define distinct proteasome populations. The results of the His6 tagging experiments shown in Fig. 10 exclude this and related models. The data indicate that the six ATPases of the proteasome are present in the same complex, further suggesting that the subunit composition of the yeast proteasome may be uniform from particle to particle. The presence of six ATPases within a given proteasome is consistent with their assembly into a six-member ATPase ring structure analogous to those found in the simple ATP-dependent proteases of prokaryotes (36, 93). The same analogy suggests that this ring is situated in contact with the CP and that substrates pass through the center of this ring as they translocate into the CP. This model is consistent with the ATP dependence of proteasome assembly from the RP and CP complexes (3, 15, 45;unpublished data). A strictly determined site of assembly for each ATPase is suggested both by the coassembly of ATPases into a single particle and by the requirement for each ATPase in yeast (30, 81, 85).

The 17 subunit assignments proposed here all have a high degree of confidence. For example, for 29 peptides sequenced, all amino acids assigned were in agreement with predictions from the sequence of the yeast genome. Moreover, most of the subunits identified were homologs of known subunits of the mammalian RP (PA700). However, the existence of additional RP subunits in yeast remains a distinct possibility, which could best be addressed by two-dimensional isoelectric focusing and SDS-PAGE. In particular, the low-molecular-mass region of the one-dimensional gels that we used contained many CP-derived bands, which could comigrate with as-yet-unidentified RP subunits. In mammals, PA700 is a stable complex which has been purified and found to associate with the CP to produce a complex that is competent for the degradation of ubiquitin-protein conjugates (1, 15, 64). We have also partially purified a particle from yeast that can, when added to CPs, similarly reconstitute the degradation of ubiquitin-protein conjugates (unpublished data). However, it has yet to be established that PA700 is identical to the RP dissociated from purified proteasomes (83). As suggested above, certain components of the proteasome may be loosely associated and thus underrepresented in purified preparations.

The percentages of identities between sequences of yeast and human homologs of the various RP subunits are given in Table 3. The ATPases are exceptionally conserved, showing 66 to 76% identity, while identity scores for the non-ATPase Rpn subunits are much lower. The only exception is Rpn11/Mpr1, which is 65% identical between yeast and humans. Interestingly, the amino acid sequence surrounding Cys-117 within Rpn11 shows similarity to sequences flanking the active-site cysteine which serves as the nucleophile in deubiquitinating enzymes (Table 4). No other RP subunit thus far identified shows significant similarity to known deubiquitinating enzymes. All known Rpn11 homologs contain extended regions of identity to one another surrounding Cys-117 in Rpn11 (Table 5). It is plausible that Rpn11 and its homologs from other species function as a new class of deubiquitinating enzymes (Table 5, group I), potentially accounting for the deubiquitinating activity detected in preparations of the mammalian PA700 complex (53, 54). The predicted molecular masses of Rpn11 and its homologs are consistent with estimates based on active-site labeling of the bovine PA700 deubiquitinating factor (54). However, our proteasome preparations had low activity in several deubiquitination assays (data not shown) (52a), despite containing apparently intact Rpn11. It is possible that the ubiquitin conjugates tested thus far are not the preferred substrates of Rpn11 and that other substrates will allow the detection of Rpn11-dependent isopeptidase activity in yeast proteasomes.

Lam and coworkers have suggested that isopeptidase activity within the proteasome may serve to inhibit the degradation of certain conjugates by progressively trimming their ubiquitin chains from the distal end (53). We suggest that proteasomal isopeptidase activity may also, depending on the substrate, accelerate conjugate breakdown by removing ubiquitin groups that prevent translocation of the proteolytic substrate through the channel of the CP. Stimulatory effects of removing ubiquitin groups from the substrate may be particularly dramatic for substrates in which ubiquitin groups are bound to multiple lysine residues within the target protein, rather than being assembled into a single chain. Assuming that the tertiary structure of ubiquitin is too stable to be unfolded by the proteasome, as suggested by structural studies (57), every ubiquitin group that is directly bound to the substrate is expected to prevent access of the substrate polypeptide to the CP in the region surrounding the ubiquitination site. Deubiquitinating enzymes that reverse such linkages would be expected to facilitate degradation, perhaps accounting for the observed simulatory effects of the deubiquitinating enzyme UCH-3 on in vitro ubiquitin-protein conjugate degradation (42). Consistent with this hypothesis, such results were obtained with a UbK48R derivative of ubiquitin which is deficient in chain formation.

It is presently unclear whether any of the remaining Rpn subunits possess enzymatic activity, since they lack sequence similarities to known enzymes. They are likely to function in the binding of proteolytic substrates, in the binding of soluble cofactors of the proteasome, or as scaffolding proteins that maintain the architecture of the RP complex. Another possible function is to target the proteasome to specific subcellular sites, although recent photobleaching studies with green fluorescent protein-tagged proteasomes indicated that >90% of proteasomes are freely diffusible in both the nucleus and the cytoplasm (74). Among Rpn subunits other than Rpn11, the only significant sequence motif identified thus far is a ninefold repeat covering approximately 400 residues in both Rpn1 and Rpn2 (60). The repeat motif is similar to previously described leucine-rich repeats which have been implicated in specific protein binding. One possible role for these repeats therefore may be binding of the proteolytic substrate, as suggested by Lupas and Baumeister (60).

The only Rpn subunit that has been extensively studied is Rpn10/Mcb1 and its homologs in Arabidopsis thaliana (Mbp1), Drosophila melanogaster (p54), and humans (S5a). Rpn10 homologs from all of these species are capable of binding multiubiquitin chains in vitro. The universality of this binding interaction strongly suggests its functional significance, and Rpn10/Mcb1/S5a has consequently been proposed to be the multiubiquitin chain receptor of the proteasome (17, 18). However, yeast mutants in which the RPN10/MCB1 gene has been deleted are viable and competent for the degradation of many ubiquitin conjugates (102). Only the model substrate ubiquitin–Pro–β-galactosidase has been found to be stabilized in the rpn10 deletion strain. To test whether Rpn10 functions as a ubiquitin receptor, the in vitro ubiquitin chain binding site of Rpn10 was localized. When mutants in which the in vitro ubiquitin chain binding site was deleted were assayed for ubiquitin–Pro–β-galactosidase degradation in vivo, they were found to be fully competent (26). These data indicate that the role of Rpn10 in protein degradation is probably independent of its ability to bind multiubiquitin chains, at least in S. cerevisiae. Nonetheless, a comparison of the sequences of Rpn10 and its homologs across eukaryotes indicates that the in vitro ubiquitin chain binding site is stringently conserved evolutionarily (26, 41, 109), suggesting that it may have a role in proteasome function that has yet to be identified. The mechanistic role of Rpn10/Mcb1 in protein breakdown remains problematic but should emerge from additional genetic analysis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Olivier Coux, Alfred Goldberg, and Inge Wefes for assistance in refining the proteasome purification procedure; Keiji Tanaka and Akio Toh-e for providing unpublished data; Chris Larsen for constructing the His6-Rpt4 plasmid; Chris Larsen and Seth Sadis for useful discussions and comments; an anonymous reviewer for helpful comments on the text; Michel Ghislain and Carl Mann for the rpt1 knockout construct and polyclonal antibodies to Rpt1 and Rpt6; Richard Diaz, Olivier Coux, and Fred Goldberg for ubiquitin-lysozyme conjugates; Steve van Nocker and Richard Vierstra for the polyclonal antibody to Rpn10; Akio Toh-e for antibodies to Rpn3, Rpn4, and Rpn12; Michelle Mischke and John Chant for anti-Cdc10 antibodies; and Andrei Lupas and Takashi Toda for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by NIH grant GM43601 (to D.F.) and by fellowships from the NIH and the Massachusetts Division of the American Cancer Society (to D.M.R.) and the Damon Runyon Walter Winchell Cancer foundation (to M.H.G.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams G M, Falke S, Goldberg A L, Slaughter C A, DeMartino G N, Gogol E P. Structural and functional effects of PA700 and modulator protein on proteasomes. J Mol Biol. 1997;273:646–657. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akiyama K, Yokota K, Kagawa S, Shimbara N, DeMartino G N, Slaughter C A, Noda C, Tanaka K. cDNA cloning of a new putative ATPase subunit p45 of the human 26S proteasome, a homolog of yeast Sug1. FEBS Lett. 1995;363:151–156. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00304-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armon T, Ganoth D, Hershko A. Assembly of the 26S complex that degrades proteins ligated to ubiquitin is accompanied by the formation of ATPase activity. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:20723–20726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baker R T, Tobias J W, Varshavsky A. Ubiquitin-specific proteases of S. cerevisiae. Cloning of UBP2 and UBP3 and functional analysis of the UBPgene family. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:23364–23375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bauer V W, Swaffield J C, Johnston S A, Andrews M T. CADp44: a novel regulatory subunit of the 26S proteasome and the mammalian homolog of ySug2p. Gene. 1996;181:63–69. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00463-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boldin M P, Mett I L, Wallach D. A protein related to a proteasomal subunit binds to the intracellular domain of the p55 TNF receptor upstream to its death domain. FEBS Lett. 1995;367:39–44. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00534-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burns N, Grimwade B, Ross-MacDonald P B, Choi E Y, Finberg K, Roeder G S, Snyder M. Large-scale analysis of gene expression, protein localization, and gene disruption in S. cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1087–1105. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.9.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell C L, Tanaka N, White K H, Thorsness P E. Mitochondrial morphological and functional defects in yeast caused by yme1are suppressed by mutation of a 26S protease subunit homologue. Mol Biol Cell. 1994;5:899–905. doi: 10.1091/mbc.5.8.899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ciechanover A. The ubiquitin-proteasome proteolytic pathway. Cell. 1994;79:13–21. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90396-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Claret F X, Hibi M, Dhut S, Toda T, Karin M. A new group of conserved coactivators that increase the specificity of AP-1 transcription factors. Nature. 1996;383:453–457. doi: 10.1038/383453a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Confalonieri F, Duguet M. A 200-amino acid ATPase module in search of a basic function. Bioessays. 1995;17:639–650. doi: 10.1002/bies.950170710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coux O, Tanaka K, Goldberg A L. Structure and functions of the 20S and 26S proteasomes. Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:801–847. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.004101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dawson S P, Arnold J E, Mayer N J, Reynolds S E, Billett M A, Gordon C, Colleaux L, Kloetzel P M, Tanaka K, Mayer R J. Developmental changes of the 26S proteasome in abdominal intersegmental muscles of Manduca sextaduring programmed cell death. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:1850–1858. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.4.1850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeMarini D J, Papa F R, Swaminathan S, Ursic D, Rasmussen T P, Culbertson M R, Hochstrasser M. The yeast SEN3gene encodes a regulatory subunit of the 26S proteasome complex required for ubiquitin-dependent protein degradation in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:6311–6321. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.11.6311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeMartino G N, Moomaw C R, Zagnitko O P, Proske R J, Ma C P, Afendis S J, Swaffield J C, Slaughter C A. PA700, an ATP-dependent activator of the 20S proteasome, is an ATPase containing multiple members of a nucleotide binding protein family. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:20878–20884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deshpande K L, Fried V A, Ando M E, Webster R G. Glycosylation affects cleavage of an H6N2 influenza virus hemagglutinin and regulates virulence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:36–40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.1.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deveraux Q, Jensen C, Rechsteiner M. Molecular cloning and expression of a 26S proteasome subunit enriched in dileucine repeats. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:23726–23729. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.40.23726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deveraux Q, Ustrell V, Pickart C, Rechsteiner M. A 26S subunit that binds ubiquitin conjugates. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:7059–7061. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dubiel W, Ferrell K, Dumdey R, Standera S, Prehn S, Rechsteiner M. Molecular cloning and expression of subunit 12: a non-MCP and non-ATPase subunit of the 26S protease. FEBS Lett. 1995;363:97–100. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00288-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dubiel W, Ferrell K, Pratt G, Rechsteiner M. Subunit 4 of the 26S protease is a member of a novel eukaryotic ATPase family. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:22669–22702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dubiel W, Ferrell K, Rechsteiner M. Peptide sequencing identifies MSS1, a modulator of HIV Tat-mediated transactivation, as subunit 7 of the 26S protease. FEBS Lett. 1993;323:276–278. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81356-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dubiel W, Ferrell K, Rechsteiner M. Subunits of the regulatory complex of the 26S proteasome. Mol Biol Rep. 1995;21:27–34. doi: 10.1007/BF00990967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Falquet L, Paquet N, Frutiger S, Hughes G J, Hoang-Van K, Jaton J C. cDNA cloning of a human 100 kDa deubiquitinating enzyme: the deubiquitinase belongs to the ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase family 2 (UCH2) FEBS Lett. 1995;376:233–237. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01287-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Finley D, Özkaynak E, Varshavsky A. The yeast polyubiquitin gene is essential for resistance to high temperatures, starvation, and other stresses. Cell. 1987;48:1035–1046. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90711-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fried V A. Membrane biogenesis: evidence that a soluble chimeric polypeptide can serve as a precursor of a mutant lac permease in E. coli. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:244–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fu H, Sadis S, Rubin D M, Glickman M H, van Nocker S, Finley D, Vierstra R D. Multiubiquitin chain binding and protein degradation are mediated by distinct domains within the 26S proteasome subunit Mcb1. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:1970–1989. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.4.1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fujimuro M, Tanaka K, Yokosawa H, Toh-e A. Son1p is a component of the 26S proteasome of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 1998;423:149–154. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00084-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fujiwara T, Watanabe T K, Tanaka K, Slaughter C A, DeMartino G N. cDNA cloning of p42, a shared subunit of two proteasome regulatory proteins, reveals a novel member of the AAA protein family. FEBS Lett. 1996;387:184–188. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00489-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gerlinger U M, Hoffmann M, Wolf D H, Hilt W. Yeast cycloheximide-resistant crlmutants are proteasome mutants defective in protein degradation. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:2487–2499. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.12.2487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ghislain M, Udvardy A, Mann C. S. cerevisiae26S protease mutants arrest cell division in G2/metaphase. Nature. 1993;366:358–361. doi: 10.1038/366358a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gietz R D, Schiestl R H, Willems A R, Woods R A. Studies on the transformation of intact yeast cells by the LiAc/SS-DNA/PEG procedure. Yeast. 1995;11:355–360. doi: 10.1002/yea.320110408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gietz R D, Sugino A. New yeast-E. colishuttle vectors constructed with in vitro mutagenized yeast genes lacking six-base pair restriction sites. Gene. 1988;74:527–534. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90185-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gorbalenya A E, Koonin E V. Viral proteins containing the NTP binding pattern. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:8413–8437. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.21.8413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gorbalenya A E, Koonin E V, Donchenko A P, Blinov V M. Two related superfamilies of putative helicases involved in replication, repair, and expression of DNA and RNA genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:4713–4729. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.12.4713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gordon C, McGurk G, Dillon P, Rosen C, Hastie N D. Defective mitosis due to a mutation in the gene for a fission yeast 26S protease subunit. Nature. 1993;366:355–357. doi: 10.1038/366355a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gottesmann S, Wickner S, Maurizi M R. Protein quality control: triage by chaperones and proteases. Genes Dev. 1997;11:815–823. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.7.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gridley T, Jaenisch R, Maguire M G. The murine Mov-34gene: full length cDNA and genomic organization. Genomics. 1991;11:501–507. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(91)90056-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Groll M, Ditzel L, Löwe J, Stock D, Bochtler M, Bartunik H D, Huber R. Structure of 20S proteasome from yeast at a 2.4 Å resolution. Nature. 1997;386:463–471. doi: 10.1038/386463a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hampton R Y, Gardner R G, Rine J. Role of 26S proteasome and HRDgenes in the degradation of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase, an integral endoplasmic reticulum membrane protein. Mol Biol Cell. 1996;7:2029–2044. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.12.2029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haracska L, Udvardy A. Cloning and sequencing a non-ATPase subunit of the regulatory complex of the Drosophila 26S protease. Eur J Biochem. 1995;231:720–725. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haracska L, Udvardy A. Mapping the ubiquitin-binding domains in the p54 regulatory complex subunit of the Drosophila 26S protease. FEBS Lett. 1997;412:331–336. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00808-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hegde A N, Inokuchi K, Pei W, Casadio A, Ghirardi M, Kandel E R, Schwartz J H. Ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase is an immediate early gene essential for long term facilitation in Aplysia. Cell. 1997;89:115–126. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80188-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hochstrasser M. Ubiquitin-dependent protein degradation. Annu Rev Genet. 1996;30:405–439. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.30.1.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hoffman L, Pratt G, Rechsteiner M. Multiple forms of the 20S multicatalytic and the 26S ubiquitin/ATP-dependent proteases from rabbit reticulocyte lysate. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:22362–22368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hoffman L, Rechsteiner M. Activation of the multicatalytic protease. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:16890–16895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hoffman L, Rechsteiner M. Molecular cloning of subunit 9 of the 26S proteasome. FEBS Lett. 1997;404:179–184. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00126-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hoffman L, Rechsteiner M. Nucleotidase activities of the 26S proteasome and its regulatory complex. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:32538–32545. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.51.32538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Johnson E S, Ma P C, Ota I M, Varshavsky A. A proteolytic pathway that recognizes ubiquitin as a degradation signal. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:17442–17456. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.29.17442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.King R W, Deshaies R J, Peters J M, Kirshner M W. How proteolysis drives the cell cycle. Science. 1996;274:1652–1659. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kominami K, DeMartino G N, Moomaw C R, Slaughter C A, Shimbara N, Fujimuro M, Yokosawa H, Hisamatsu H, Tanahashi N, Shimizu Y, Tanaka K, Toh-e A. Nin1p, a regulatory subunit of the 26S proteasome, is necessary for activation of Cdc28 kinase of S. cerevisiae. EMBO J. 1995;14:3105–3115. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07313.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kominami K, Okura N, Kawamura M, DeMartino G N, Slaughter C A, Shimbara N, Chung C H, Fujimura M, Yokosawa H, Shimizu Y, Tanahashi N, Tanaka K, Toh-e A. Yeast counterparts of subunits S5a and p58 (S3) of the human 26S proteasome are encoded by two multicopy suppressors of nin1-1. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:171–187. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.1.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52a.Lam, A., and R. Cohen. Personal communication.

- 53.Lam Y A, DeMartino G N, Pickart C M, Cohen R E. Specificity of the ubiquitin isopeptidase in the PA700 regulatory complex of the 26S proteasome. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:28438–28446. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.45.28438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lam Y A, Xu W, DeMartino G N, Cohen R E. Editing of ubiquitin conjugates by an isopeptidase in the 26S proteasome. Nature. 1997;385:737–740. doi: 10.1038/385737a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54a.Larsen, C., and S. Sadis. Personal communication.

- 55.Larsen C N, Finley D. Protein translocation channels in the proteasome and other proteases. Cell. 1997;91:431–434. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80427-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee J W, Choi H S, Gyuris J, Brent R, Moore D D. Two classes of proteins dependent on either the presence or absence of thyroid hormone for interaction with the thyroid hormone receptor. Mol Endocrinol. 1995;9:243–254. doi: 10.1210/mend.9.2.7776974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lenkinski R E, Chen D M, Glickson J D, Goldstein G. Nuclear magnetic resonance studies of the denaturation of ubiquitin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1977;494:126–130. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(77)90140-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57a.Levin, D. Personal communication.

- 58.Longtine M S, DeMarini D J, Valencik M L, Al-Awar O S, Fares H, De Virgilio C, Pringle J R. The septins: roles in cytokinesis and other processes. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1996;8:106–119. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(96)80054-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Löwe J, Stock D, Jap B, Zwickl P, Baumeister W, Huber R. Crystal structure of the 20S proteasome from the archeon T. acidophilumat 3.4 Å resolution. Science. 1995;268:533–539. doi: 10.1126/science.7725097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lupas A, Baumeister W. A repetitive sequence in subunits of the 26S proteasome and 20S cyclosome (APC) Trends Biochem Sci. 1997;22:195–196. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01058-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lupas A, Flanagan J M, Tamura T, Baumeister W. Self compartmentalizing proteases. Trends Biochem Sci. 1997;22:399–404. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01117-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lupas A, van Dyke M, Stock J. Predicted coiled-coils from protein sequences. Science. 1991;252:1162–1164. doi: 10.1126/science.252.5009.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ma C P, Slaughter C A, DeMartino G N. Identification, purification, and characterization of a protein activator (PA28) of the 20S proteasome. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:10515–10523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ma C P, Vu J H, Proske R J, Slaughter C A, DeMartino G N. Identification, purification, and characterization of a high molecular weight ATP-dependent activator (PA700) of the 26S proteasome. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:3539–3547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.McCusker J H, Haber J E. Cycloheximide-resistant temperature-sensitive lethal mutations of S. cerevisiae. Genetics. 1988;119:303–315. doi: 10.1093/genetics/119.2.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.McDonald H B, Byers B. A proteasome cap subunit required for spindle pole body duplication in yeast. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:539–553. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.3.539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mian I S. Sequence similarities between cell regulation factors, heat shock proteins and RNA helicases. Trends Biochem Sci. 1993;18:125–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nelbrock P, Dillon P J, Perkins A, Rosen C R. A cDNA for a protein that interacts with the human immunodeficiency virus Tat transactivator. Science. 1990;248:1650–1654. doi: 10.1126/science.2194290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nelson M K, Kurihara T, Silver P A. Extragenic suppressors of mutations in the cytoplasmic C terminus of SEC63 define five genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1993;134:159–173. doi: 10.1093/genetics/134.1.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]