Abstract

Introduction

Lucio leprosy is a non-nodular diffuse type of lepromatous leprosy first described by Lucio and Alvarado. Lucio phenomenon is a rare vasculonecrotic reaction characterized by cutaneous necrosis with minimal constitutional features.

Case Presentation

We describe an unusual case of a 53-year-old man from Central India who had blisters, ulcers, and widespread erosions on his foot, forearms, and arms. The diagnosis of lepromatous leprosy with the Lucio phenomenon was established after thorough evaluation by clinical findings, histopathological findings, and slit-skin smear examination.

Conclusion

Lucio phenomenon is an uncommon cause of cutaneous infarction and necrosis. Primary care physicians should keep a high index of suspicion in patients with cutaneous necrosis and minimal constitution features. Since leprosy is a relatively curable disease, primary care physicians should think of a rare form of lepromatous leprosy presenting with cutaneous necrosis, especially in non-endemic zones.

Keywords: Leprosy, Lucio phenomenon, Ulcer, Cutaneous necrosis, Microvascular occlusion

Introduction

Lucio phenomenon is a rare cause of cutaneous infarction seen in cases of lepromatous leprosy. Leprosy is endemic in India and the Sub-Saharan subcontinent belt; however, very few cases of lepromatous leprosy eventually turn into the Lucio phenomenon. [1].

Leprosy is acquired when a genetically susceptible host comes into significant contact with an untreated, so-called open case of leprosy. Bacilli are usually found in the upper airway discharge and aerosol in untreated cases of multibacillary cases. The primary portal of entry/exit for Mycobacterium leprae is the nasal mucosa [2].

Clinically, the Lucio phenomenon is characterized by widespread, oddly shaped, painful skin ulcerations, and surprisingly few or no constitutional signs. Pathology shows the mobilization and proliferation of polyblasts and histiocytes, as well as dilatation, endothelial proliferation, luminal occlusion, and thrombosis of the superficial and mid-dermal blood vessels, and the presence of acid-fast bacilli in the blood vessel walls, confirms the clinical diagnosis [3]. Lucio phenomenon is a common cause of cutaneous infarction and necrosis. Primary care physicians should keep a high index of suspicion in patient with cutaneous necrosis and minimal constitution features.

Clinical Case

A 53-year-old male, a farmer by occupation, presented to the dermatology outpatient department with complaints of repeated blisters, cutaneous necrosis, and ulcers on both hands and feet for 2 years. The patient reportedly gave the history of having black-colored bizarre-shaped lesions on both arms, forearms, hand, and ear pinna for the past 3 weeks. The patient also gave a history of swelling of both hands and feet along with a reduced sensation of the acral area of hands and feet. The patient denied any history of tingling and numbness, fever, joint pain, epistaxis, history of any drug intake prior to the onset of the lesion, or lacrimation.

On cutaneous examination, there was the presence of multiple irregularly-shaped ecchymotic and necrotic plaques surrounded by a dusky red zone with black adherent crust present on both arms, forearm, hand (Fig. 1a), and pinna (Fig. 1b). General examination showed diffuse infiltration of bilateral earlobes, madarosis of the ciliary and superciliary areas, and pitting edema of both hands and feet with necrotic ulceration and serous discharge from the feet (Fig. 2). Peripheral nerve examination revealed thickening of the bilateral ulnar and common peroneal nerve, along with neuritis, gloves, and stocking pattern of peripheral sensory anesthesia. There was evidence of nodules or hypopigmented patches anywhere on the body. Cranial nerve and motor examination did not show any deficit.

Fig. 1.

a Clinical image showing multiple bizzare-shaped cutaneous infarcts on the dorsa of both the hands and fingers. b Clinical image showing necrosis of the pinna on the right ear.

Fig. 2.

Clinical image showing deep necrotic ulcers on both feet.

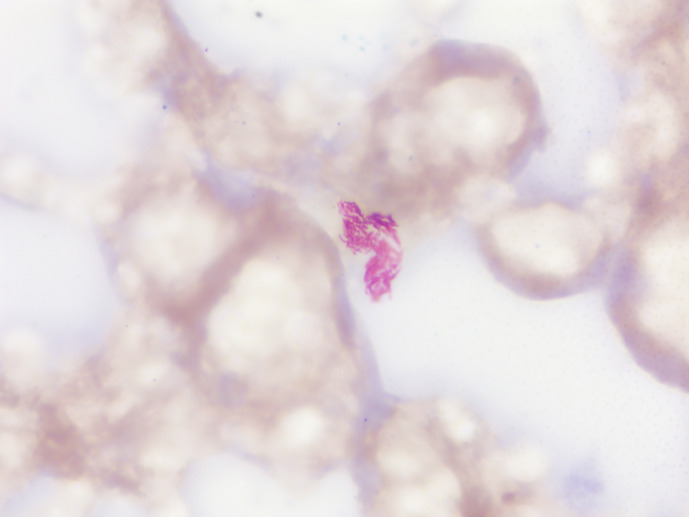

His complete blood count along with differential blood count was normal except for low hemoglobin (9.6 gm/dL), elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (36 mm at the end of the first hour), and positive rheumatoid factor (26 IU/mL). Routine serum biochemistry for the liver function test, kidney function test, random blood sugar, and urine examination were within the normal range. Serological tests for hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, and retrovirus were negative. His chest radiograph, Mantoux test, and sputum for acid-fast bacilli did not show any evidence of tubercular infection. Slit-skin smear examination obtained from the forehead and ear helices showed 4+ (10–100 bacilli in the average oil field) bacteriological index (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Slit-skin smear obtained from the earlobe of the left ear showing 4+ bacteriological index of acid-fast bacilli, Mycobacterium leprae.

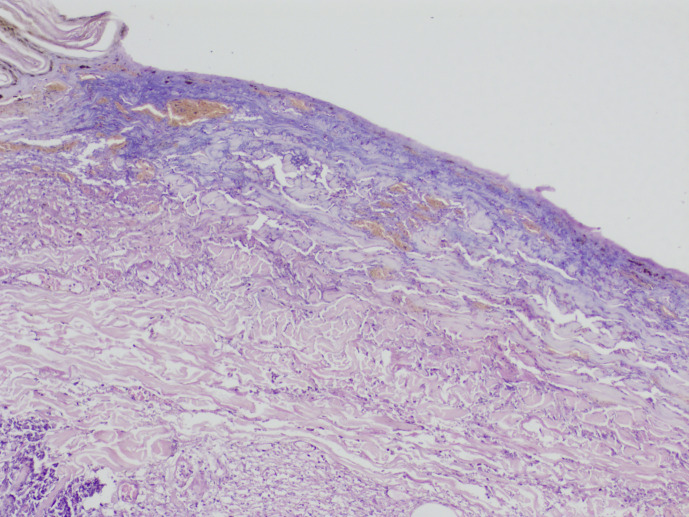

Coagulation profiles including prothrombin time/international normalized ratio, and activated partial thromboplastin time were within normal limit ruling out the possibility of underlying coagulopathy. Laboratory workup for connective tissue disease, including antinuclear antibody (ANA) were negative. Histopathological examination of the central and peripheral lesions showed foamy macrophages and the dermal vasculature showed changes suggestive of epidermal necrosis, ischemic necrotizing endarteritis obliterans, resulting in microvascular occlusion of dermal vasculature (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

H&E-stained section of skin biopsy from the edge of cutaneous infarct showing epidermal necrosis with dermal vascular occlusion.

Based on clinical and histopathological examination, diagnosis of the Lucio phenomenon was made. The patient was started on standard World Health Organization multibacillary multidrug therapy (WHO-MDT) comprising oral rifampicin 600 mg supervised dose once a month, clofazimine 300 mg supervised dose once a month and 50 mg unsupervised dose daily, and dapsone 100 mg daily. In addition to WHO-MDT, the patient was prescribed oral prednisolone 40 mg once a day for 15 days for anti-inflammatory action.

Discussion

Cutaneous microvascular occlusion syndrome (MVOS) presents as purpura or necrosis with minimal erythema. Through prompt identification and therapy, it can avert potentially fatal and organ-threatening consequences. On one hand, it can act as a marker for identifying the concomitant significant underlying systemic causes [4]. The causes of cutaneous MVOS based on pathophysiological mechanisms are systemic and vascular coagulopathies, infections, embolization, cell occlusion syndromes, and platelet-related thrombopathy [5].

Our case highlights the infectious cause of MVOS. Infectious organisms primarily affect immunosuppressed hosts and result in vascular blockage caused by invading microorganisms. Ecthyma gangrenosum [5], Lucio-Latapi’s leprosy [5], opportunistic fungal infections [6, 7], disseminated strongyloidiasis [8], Rocky Mountain spotted fever [9], and meningococcemia [10] are included in infectious cause of MVOSs. The differentiating features between the various infective causes of microvascular occlusion are summarized in Table 1. Patients with the non-nodular diffuse type of leprosy and untreated asymptomatic patients symptoms can develop the Lucio phenomenon, a type of vasculonecrotic response [11].

Table 1.

Infectious causes of MVOS

| Disease | Ecthyma gangrenosum [5] | Opportunistic fungal infection [Aspergillus spp., Rhizopus spp.] [6, 7] | Lucio phenomenon [5] | Disseminated strongyloidiasis [8] | Rocky Mountain spotted fever [9] | Meningococcemia [10] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical features | Painless erythematous macules that progress to form purpuric or escharotic lesions | Purpuric lesions in a retiform manner with cutaneous necrosis and sinus formation | Bullous and purpuric bizarre-shaped lesions that are surrounded by a dusky red erythematous zone that later necrotize are present on extremities with diffuse infiltration of earlobes | Reticulate purpuric lesions in a migratory and serpiginous pattern known as larva migrans | Petechial rash that begins from distal extremities and proceeds centripetally involving palms and soles | Pink maculopapular non-blanch-able rash which later merge to form large ecchymotic lesions |

| Investigation | Gram stain and culture for gram-negative bacilli, skin biopsy | Wet mount and culture for detection of fungi, histopathology, molecular methods | Slit-skin smear for detection of acid-fast bacilli, histopathology | Laboratory investigations for eosinophilia, stool culture for detection of Rhabditiform larva, ELISA | Serology testing, DNA testing by PCR, immunohistochemical staining of skin tissue | Gram stain and culture for detection of meningococcus, skin biopsy, CSF analysis |

| Treatment | Antibiotics like ceftazidime, amoxicillin, and clavulanic acid | Liposomal amphotericin B, posaconazole, isavuconazole | Thalidomide, multibacillary multidrug therapy and corticosteroids | Ivermectin, albendazole, and corticosteroids | Doxycycline and chloramphenicol | IV fluids, antibiotic therapy mainly 3rd generation cephalosporins and penicillin, vasoactive agents, and corticosteroids |

| In severe cases, surgical debridement may be required |

Lucio and Latapi described a peculiar form of polar leprosy characterized by diffuse infiltration of the entire skin, no nodularity of skin, complete alopecia of eyebrows and eyelashes and body hair, anhidrotic and dysesthesia zones of the skin, and a peculiar type of lepra reaction named Lucio’s phenomenon. According to international literature, the definition of the Lucio phenomenon is based on three criteria: cutaneous ulceration, vascular thrombosis, and bacillary invasion of cutaneous blood vessel walls with Mycobacterium leprae. Lepra bonita, which translates from Spanish as “pretty leprosy,” is another name for Lucio leprosy, a diffuse, non-nodular form of the disease that is commonly linked to the Lucio phenomenon. This term refers to the shiny, myxedematoid appearance of the skin that is characteristic of this form of leprosy [12].

The underlying cause of Lucio’s phenomenon is still unknown. The most widely recognized theory is that lepra bacilli multiply within the cutaneous microvasculature without restriction, causing widespread infiltration of the skin on an anergic background and increased exposure of the mycobacterial antigen to circulating antibodies, which can cause vasculitis [3].

In case of the Lucio phenomenon, the patient has minimal constitutional signs and symptoms with no concomitant neuritis, visceral involvement, or fever. The affected patient may experience mild discomfort and pain in the lesion of cutaneous infarction. According to the original observation by Latapi and Zamora, cutaneous ulcers often heal in 2 weeks and leave behind atrophic scars [13].

In a review by Frade et al. [14], clinically, all the affected patients displayed diffuse skin infiltration, purpuric macules, irregular skin ulcers, and skin necrosis. Usually, the patient with the Lucio phenomenon rarely has constitutional symptoms; there are cases of the Lucio phenomenon presenting with painful papules, macules, and necrotic lesions along with fever, myalgia, and headache [15–18].

Necrotic lesions in leprosy patients have two differential diagnoses: Lucio phenomenon and Erythema Nodosum Leprosum necroticans. The vasculonecrotic erythema nodosum leprosum, which manifests as painful necrotic ulcers with constitutional symptoms, neuritis, and occasionally visceral involvement, may be confused with the Lucio phenomenon. The differentiating features between the two are given in Table 2 [1, 11, 15].

Table 2.

Distinguishing features erythema nodosum necroticans (ENL necroticans) and Lucio phenomenon

| Parameters | Erythema nodosum necroticans | Lucio phenomenon |

|---|---|---|

| Patient profile | Seen in patients on treatment for multibacillary leprosy with nodules and plaques | Seen in untreated cases of diffuse and primitive leprosy without any nodules |

| Clinical features | Clinically presents as small, round-shaped, deep necrotic ulcers involving the trunk, upper, and lower limbs | Clinically presents as large, irregularly, and bizarre-shaped red to purple superficial ulceration involving the dorsum of hands, feet, and rarely trunk |

| Systemic features | Neuritis, visceral involvement, and fever are frequently associated | Rarely neuritis and fever are seen with no visceral involvement |

| Pathological features | On histology, there is neutrophilic predominance with involvement of odd dermis and hypodermis in the form of necrotizing vasculitis | On histology, there is superficial vasculitis with or without thrombosis limited to small vessels of superficial dermis |

| Slit-skin smear findings | Acid-fast bacilli are usually not seen on histopathology | Acid-fast bacilli are well preserved in granular cells |

| Treatment | Treatment includes a high dose of steroids in combination with anti-leprosy drugs | Treatment includes anti-leprosy drugs with or without steroids |

Multibacillary multidrug therapy for leprosy, which contains rifampicin, dapsone, and clofazimine for 12 months, is used to treat the Lucio phenomenon. In extreme situations, a brief course of high-dose corticosteroids (oral prednisolone 1 mg/kg/day) can be useful in reducing the initial immunological response [3, 15].

Conclusion

Our report serves as a good example of the diagnostic challenge presented by lepromatous leprosy in non-endemic areas. When a patient has significant leg ulcerations with ecchymotic plaques, it should be included in the differential diagnosis because it can mimic many life- and limb-threatening conditions. Given that it is largely treatable, it is vital to train the front-liners in non-endemic nations to be cautious and possess a high index of suspicion to avert unfavorable results. A prompt diagnosis can be made possible by slit-skin smears, and skin biopsies will enable the implementation of the proper therapy as soon as possible.

Skin lesions linked with MVOS are rarely given enough attention and are commonly mistaken for cutaneous vasculitis or systemic vasculitis. The severity, length, particular underlying cause, and early and adequate care frequently determine the outcomes of MVOS. The CARE Checklist has been completed by the authors for this case report, attached as online supplementary material (for all online suppl. material, see https://doi.org/10.1159/000536370).

Statement of Ethics

The authors attest to having gotten all necessary patient consent papers. The patient has granted his permission in the form for photographs and other clinical data to be published in the publication. The patient is aware that every attempt will be made to maintain anonymity and that neither name nor initials will be published. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of the details of their medical case and any accompanying images. Ethical approval is not required for this study in accordance with local or national guidelines.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding Sources

The author(s) affirmed that this work was not funded by any grants.

Author Contributions

Kaveri Rusia, Vikrant Saoji, Bhushan Madke, and Adarshlata Singh contributed in writing – original draft preparation, visualization, data curation, review and editing.

Funding Statement

The author(s) affirmed that this work was not funded by any grants.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and its online supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Sharma P, Kumar A, Tuknayat A, Thami GP, Kundu R. Lucio phenomenon: a rare presentation of Hansen’s disease. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2019;12(12):35–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lastória JC, Abreu MA. Leprosy: review of the epidemiological, clinical, and etiopathogenic aspects-part 1. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89(2):205–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sehgal VN. Lucio’s phenomenon/erythema necroticans. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44(7):602–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Abtahi-Naeini B, Dehghani S. COVID-19: a new cause of cutaneous microvascular occlusion syndrome. J Res Med Sci. 2021;26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lamadrid-Zertuche AC, Garza-Rodríguez V, Ocampo-Candiani JDJ. Pigmented purpura and cutaneous vascular occlusion syndromes. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93(3):397–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mohammadi F, Badri M, Safari S, Hemmat N. A case report of rhino-facial mucormycosis in a non-diabetic patient with COVID-19: a systematic review of literature and current update. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21(1):906–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Skiada A, Pavleas I, Drogari-Apiranthitou M. Epidemiology and diagnosis of mucormycosis: an update. J Fungi. 2020;6(4):265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Siddiqui AA, Berk SL, Siddiqui AA, Berk SL. Diagnosis of Strongyloides stercoralis infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33(7):1040–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Minniear TD, Buckingham SC. Managing rocky mountain spotted fever. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2009;7(9):1131–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sethi PK, Thukral R, Sethi NK, Torgovnick J, Arsura E, Wasterlain A. Meningococcal disease: a case report and discussion of clinical presentation and management. E J Med. 2012;17(1):40–5. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fogagnolo L, de Souza EM, Cintra ML, Velho PENF. Vasculonecrotic reactions in leprosy. Braz J Infect Dis. 2007;11(3):378–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Prem Anand P, Oommen N, Sunil S, Deepa MS, Potturu M. Pretty leprosy: another face of Hansen’s disease! A review. Egypt J Chest Dis Tuberculosis. 2014;63(4):1087–90. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Latapi F, Chevez Zamora A. The “spotted” leprosy of lueio (La lepra “manchada” de Lucio). An introduction to its clinical and histological study. Int J Lepr. 1948;16(4):421–30. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Frade MAC, Coltro PS, Filho FB, Horácio GS, Neto AA, da Silva VZ, et al. Lucio’s phenomenon: a systematic literature review of definition, clinical features, histopathogenesis and management. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2022;88(4):464–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Benard G, Sakai-Valente NY, Bianconcini Trindade MA. Concomitant Lucio phenomenon and erythema nodosum in a leprosy patient: clues for their distinct pathogeneses. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31(3):288–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kim JY, Chung KY, Kim WJ, Jung SY. Lucio phenomenon in non-endemic area of Northeast Asia. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(4):e192–e194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tajalli M, Wambier CG. Lucio’s phenomenon. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(17):1646–. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yang HM, Liu SW, Li YF, Wang YC. Lucio’s phenomenon. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2023;56(3):647–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and its online supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.