Abstract

Key Clinical Message

This unique case report of primary Sjogren's syndrome (pSS) shows bilateral ptosis and significant periorbital edema, compromising vision. To avoid misleading diagnosis, antibody tests must be evaluated and interpreted in the context of clinical findings.

Abstract

Primary Sjögren's syndrome is an idiopathic, autoimmune disorder involving the lacrimal and salivary glands characterized by both localized and systemic manifestations including xerostomia and keratoconjunctivitis sicca. Myasthenia Gravis (MG) is also an autoimmune disorder characterized by the development of auto‐antibodies against nicotinic acetylcholine receptors that causes decreased muscle response to stimulation. It usually presents with ptosis and generalized body weakness. Ophthalmological involvement is common in both disorders but ptosis is very rarely seen in pSS. We report the case of a 27‐year‐old woman presenting to our clinic with the complaint of ptosis and eyelid swelling. She also had a positive anti‐acetylcholine receptor antibody test and her initial presentation mimicked Myasthenia Gravis. Her autoimmune workup revealed a positive titer of Anti Ro SSA antibodies. Myasthenia Gravis was ruled out on electrodiagnostic studies which showed no decremental response, and pSS was confirmed on lip biopsy. Our case highlights that it is important to interpret the antibody test results in the context of clinical findings as we can have spurious results in autoimmune diseases. Autoimmune conditions can have varying presenting complaints hence, clinical judgment should always overrule diagnostic investigations and should thus guide patient management.

Keywords: autoimmune diseases, eyelid ptosis, myasthenia gravis, Sjogren's syndrome

1. INTRODUCTION

Primary Sjögren's syndrome (pSS) is an idiopathic, autoimmune disorder characterized by both localized and systemic manifestations. The most common clinical presentations include the “sicca” or “dryness” symptoms such as xerostomia and keratoconjunctivitis sicca due to diminished salivary gland and lacrimal gland function, respectively. Patients may also present with nonspecific symptoms such as fatigue and arthralgia, as well as pulmonary, gastrointestinal, neurological, and renal involvement. 1 Secondary Sjogren's syndrome can coexist with other autoimmune disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). 2

According to the literature, ocular signs and symptoms in pSS range from foreign body sensations, punctate or filamentous keratitis, to overt seborrheic blepharitis 3 and eyelid swelling is reported to be rare. We report a rare presentation of Sjogren's syndrome in which the patient developed severe evolving mechanical ptosis and eyelid swelling to the extent that it impaired her ability to lift open her eyes and see, along with a positive anti‐acetylcholine receptor antibody test.

2. CASE HISTORY AND EXAMINATION

A 27‐year‐old woman presented to our rheumatology department with the complaint of periorbital swelling for the past 5 months. Prior to coming to our clinic, she presented to the neurology department of one of our allied hospitals, Benazir Bhutto Hospital with a complaint of drooping of eyelids for the last 5 months, where she was presumed to be a case of Myasthenia Gravis (MG) on the basis of positive anti‐acetylcholine receptor antibodies. She was given a therapeutic trial of pyridostigmine, but she failed to respond to the treatment and was referred to our rheumatology clinic for an autoimmune workup.

The periorbital swelling was gradual, bilateral, and had progressed to the degree that the patient had significant difficulty in opening her eyes. She resorted to use her fingers to lift her eyelids in order to see. Figure 1 shows the extent of her ptosis and eyelid swelling. It was not associated with any pain, redness, discharge, loss of vision, or diplopia. Upon systemic inquiry, she complained of undocumented weight loss, productive cough for the past 3 months, dry, gritty eyes, dry mouth, hair loss, and a photosensitive facial rash. There was no significant family history of disease other than her father, who was treated for tuberculosis 10 years ago.

FIGURE 1.

Photograph of the patient when she first presented to our department showing severe eyelid swelling. The lower face is covered to protect patient privacy.

On clinical examination, our patient had periorbital puffiness with closed palpebral fissures, there was no redness or discharge, and she had normal extraocular eye movements. There was no assessable lymphadenopathy, and none of the salivary glands were palpable. On oral examination, Schirmer test was positive with less than 5 mm tear production in 5 min, which is suggestive of dry eyes. On respiratory examination, bilateral coarse crepitations were heard. Her neurological examination was unremarkable, and muscle strength and endurance in all muscle groups were normal which was in contrast to the symptoms of MG. We could not perform all the provocative maneuvers for ocular MG (sustained‐up gaze, Herring's sign, peek sign) because of marked eyelid swelling that impaired lifted the eyelids. There was no fatigable diplopia. The rest of the systemic examination was normal.

3. METHODS

Peripheral blood test results were as follows: hemoglobin 14.0 g/dL, total leucocyte count 14,000/mm3, neutrophils 70.2%, lymphocytes 25.1%, mixed 5.7%, red blood cells 4.21 million/mm3, platelets 223,000/mm3, hematocrit 38.9%, erythrocyte sedimentation rate 44 mm/hour, C‐reactive protein 4.1 mg/L, Serum biochemical testing results were as follows: serum urea 3.0 mmol/L, serum creatinine 55 umol/L, serum sodium 137 mmol/L, serum potassium 4.6 mmol/L, alanine aminotransferase 15 U/L, alkaline phosphatase 86 U/L, and total bilirubin 0.4 mg/dL. The results of her autoimmune workup are displayed in Table I. Repetitive nerve stimulation showed no significant decremental response, which helped rule out generalized myasthenia gravis but not ocular myasthenia gravis.

We proceeded with a high‐resolution computed tomography (HRCT) scan of her chest, which revealed bilateral cylindrical bronchiectasis involving all lung lobes, consolidation in the right lower lobe, and mild pleural effusion. PCR was negative for COVID‐19, sputum for Gene Xpert, and Quantiferon TB gold test was also negative. Sputum culture revealed heavy growth of Candida and Klebsiella Pneumoniae. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain and orbits revealed bilateral symmetrical homogenous enlargement of lacrimal glands with accompanied symmetrical swelling and edematous changes in bilateral pre‐septal and para‐septal soft tissues. Figure 2 shows these MRI images prior to commencing therapy.

FIGURE 2.

MRI of Brain and orbits of the patient prior to commencing therapy showing lacrimal gland enlargement.

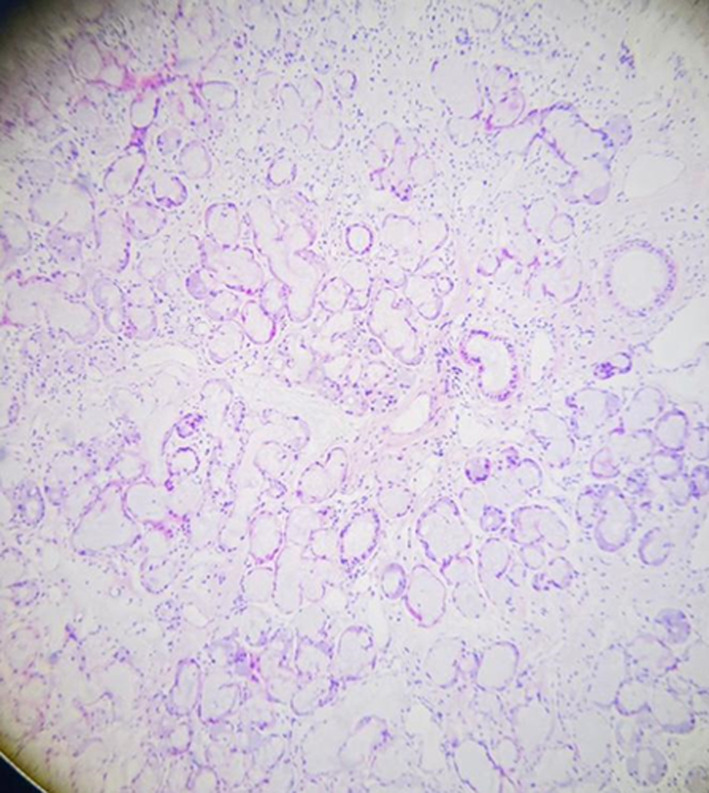

We considered the following differential diagnoses: primary Sjogren syndrome, ANCA‐associated vasculitis, IgG4‐related orbital pseudotumor, ocular myasthenia with idiopathic orbital inflammation, sarcoidosis, and systemic lupus erythematosus because she had a history of photosensitive facial rash. Our autoimmune investigations (shown in Table 1) had ruled out SLE, sarcoidosis, and ANCA‐associated vasculitis because they were all negative for the corresponding antibodies. Myasthenia gravis was ruled out on the basis of electrodiagnostic studies and ocular Myasthenia gravis was ruled out on the basis of failure to respond to the initial treatment trial of pyridostigmine. As she tested positive for anti‐SSA antibodies, we proceeded with a lip biopsy to confirm the diagnosis of primary Sjogren's syndrome and to rule out IgG4‐related disease. The lip biopsy indicated normal‐looking mucinous acini with lymphocytic infiltrate. There were four microscopic foci of lymphoid aggregates per 4 mm2, with no evidence of plasma cells and fibrosis (hence ruling out IgG4‐related disease), suggestive of primary Sjogren syndrome (pSS). Figure 3 shows the histopathological images of her lip biopsy.

TABLE 1.

Results of autoimmune workup of the patient.

| Test | Result | Normal levels |

|---|---|---|

| Anti‐nuclear antibodies | Negative | |

| Anti‐cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies | 2 AU/mL |

<10 AU/mL – Negative >10 AU/mL – Positive |

| Anti Sm antibodies | Negative | |

| Anti RNP antibodies | Negative | |

| Anti SSA (RO) antibodies | Positive | |

| RO‐52 | Positive | |

| Anti SSB (La) antibodies | Negative | |

| Anti Jo 1 antibodies | Negative | |

| Anti Scl 70 antibodies | Negative | |

| RA factor | Negative (<8) |

<8 IU/mL – Negative >8 IU/mL – Positive |

| Anti‐neutrophil cytoplasmic auto antibodies | Negative | |

| Serum Total IgE | 9 IU/mL | Less than 150 IU/mL |

| Total Vitamin D | 51 nmol/L |

Deficiency <25 nmol/L Insufficiency 25–75 nmol/L Sufficiency 75–250 nmol/L |

| ACE | 48.0 U/L | 8–52 U/L |

| C3 | 92.84 mg/dL | 90–180 mg/dL |

| C4 | 14.48 mg/dL | 9–36 mg/dL |

| Anti‐acetylcholine receptor antibodies | 1.05 nmol/L |

Negative <0.40 nmol/L Borderline >0.40 nmol/L to <0.50 nmol/L Positive >0.50 nmol/L |

| IgG Immunoglobulin level | 26.1 g/L | 5.3–16.5 g/L |

| Alpha‐1 Antitrypsin | 209 mg/dL | 23–383 mg/dL |

| Thyroid function tests | ||

| Serum Free T4 | 14.56 pmol/L | 8–24 pmol/L |

| Serum TSH | 1.14 mIU/L | 0.4–4.50 mIU/L |

| 24 h urine for protein | ||

| Urinary volume | 850 mL | |

| Urinary protein | 92 | 50–150 mg/24 h |

| Urinary protein excretion rate | 78 | 50–150 mg/24 h |

FIGURE 3.

Lip biopsy of the patient showing normal looking mucinous acini with lymphocytic infiltrate. Four microscopic foci of lymphoid aggregates per 4mm2 were examined.

A pulmonology consultation was sought, and she was started on an antibiotic cover to control infective pulmonary etiology prior to beginning immunosuppressive treatment for pSS. The patient was advised acetylcysteine, azithromycin 250 mg for 3 months along with influenza and pneumococcal vaccine. After her chest infection subsided, we started her on hydroxychloroquine 200 mg/day, azathioprine 2.5 mg/kg/day, and prednisolone 0.5 mg/kg/day. cyclophosphamide was deferred because we believed it would worsen her bronchiectasis. The patient was referred for an ophthalmology consultation for her persistent eyelid swelling, and the consensus was to control her primary disease process, which would ultimately resolve her swelling. As the persistent swelling was hampering her ability to see, she underwent a sling procedure to open her eyelids. Figure 4 shows an image of the patient after her sling procedure. Though the swelling had considerably subsided on therapy, her lacrimal glands were persistently inflamed. We shifted her towards a biological agent Rituximab, 1 g IV infusion. She has received two doses, and the next dose was scheduled for after 6 months. The recovery after the initiation of treatment is depicted in Figure 5.

FIGURE 4.

Photograph of the patient after sling procedure.

FIGURE 5.

MRI Brain and orbits after immunosuppressive therapy showing a decrease in lacrimal gland size after therapy.

4. DISCUSSION

This case highlights a rare presentation of pSS. The patient developed bilateral ptosis along with prominent eyelid swelling, which evolved to the extent that she could not lift her eyelids to see. Eyelid swelling has been reported in primary Sjogren's syndrome, 4 but to our knowledge, this is the first case in which the swelling has evolved to the extent that it impairs the patient's ability to lift open her eyes. Sjogren syndrome has a multitude of ophthalmological manifestations ranging from chronic conjunctivitis, sterile keratolysis, and non‐healing corneal ulcers, 5 but lacrimal gland involvement is reported to be rare. 1

Due to her initial presentation with ptosis and eyelid swelling along with a positive anti‐acetylcholine receptor antibody test, we presumed her to be a case of MG, and she was given a therapeutic trial of pyridostigmine, to which she failed to respond. This made us reconsider her initial diagnosis of MG, and we started her autoimmune workup. Our case is unique in this aspect as well because MG and Sjogren's syndrome very rarely co‐exist in the same patient, and very few cases have been reported in the current literature. 6 , 7 , 8 There are many diagnostic modalities for MG including ice pack test, tensilon test, anti‐acetylcholine receptor antibodies, repetitive nerve stimulation, and electromyography, all with varying sensitivity and specificity. 9 Of these, the positive titer of anti‐acetylcholine receptor antibodies has the highest specificity (97–99%) for the diagnosis of MG. 10 Our patient had no typical signs or symptoms of MG aside from ptosis, but she had a positive titer of anti‐acetylcholine receptor antibodies. We proceeded with repetitive nerve stimulation tests, which showed no decremental response, hence ruling out generalized MG but not ocular MG. A positive titer for this assay in the absence of typical signs and symptoms, a negative therapeutic trial of pyridostigmine, and electrodiagnostic studies ruling out generalized MG could mean that the test result was spuriously positive in our patient. The pathogenesis of false‐positive antibody test results in the context of autoimmune diseases is very interesting and has been reported in a number of other autoimmune diseases as well. 11 , 12 These false‐positive antibody results can be attributed to the phenomenon of heterophil antibody interference in which some of the patient's antibodies react with the immunometric sandwich assays and cross‐link the assay antibodies yielding a false‐positive test result. 13 Heterophil antibody interference has been well documented in the literature, and there are examples of catastrophic patient outcomes due to this phenomenon such as the HCG scandal in which false‐positive HCG levels, later attributed to heterophil antibodies, caused unnecessary treatment in a number of women. 14 Heterophile antibodies are common in autoimmune diseases and should be suspected in cases of positive antibody titers in absence of a solid clinical picture of the disease, and clinicians need to be made aware of this phenomenon. If such a spurious test result is encountered either on a single occasion or repeatedly, it should be followed by confirmatory testing and taking the clinical context into account. Our case thus highlights the importance of interpreting antibody test results in the context of clinical findings as our patient did not have MG despite a positive anti‐acetylcholine receptor antibody test result indicated by a negative therapeutic trial of pyridostigmine and electrodiagnostic studies.

The recent 2016 ACR‐EULAR Classification Criteria for primary Sjögren's Syndrome is most commonly used to establish a diagnosis of pSS. 15 On the basis of focal lymphocytic sialadenitis upon labial salivary gland biopsy, positive Anti‐SSA (RO) antibodies, and positive Schirmer test, our patient scored seven out of nine, where a score of 4 or more is required for a definite diagnosis of pSS.

Based on the HRCT findings, our patient also had co‐existent bronchiectasis, because of which she could not be started on immunosuppressive therapy for pSS immediately until the pulmonary infection had been resolved. Pulmonary involvement is an extraglandular manifestation of pSS, and it can be in the form of both interstitial parenchymal disease and airway disease. Bronchiolitis and bronchiectasis are the common airway lung diseases seen in pSS. The prevalence of bronchiectasis is up to 10% with involvement of the inferior lobes being more common. 16 Cylindrical bronchiectasis is the most common type seen, and patients of bronchiectasis have a higher frequency of respiratory infections and pneumonia. 17 Our patient similarly had bilateral cylindrical bronchiectasis involving all of the lung lobes along with a positive sputum culture for Klebsiella pneumoniae thus indicating an infective etiology coexisting with her autoimmune pulmonary manifestation. The pathogenesis of pulmonary involvement in pSS seems to involve epithelial damage due to any environmental factor such as infection or an extension of the primary immune response in salivary glands, followed by epitope spreading, antigen presentation and lymphocyte activation, formation of antibodies, and release of cytokines leading to an inflammatory state damaging airways and lung parenchyma. 16 Pulmonary involvement also proved to be a challenge in management as we had to control the infective etiology with antibiotics prior to commencing immunosuppressive therapy to avoid a flare‐up of the lung disease.

5. CONCLUSION

Our case highlights a unique ophthalmological manifestation of pSS and provides key insight into managing this autoimmune disease. We must always look at the clinical picture of a disease instead of relying solely on investigations as elucidated in our case, where a positive anti‐acetylcholine receptor antibody test led to a misleading diagnosis of MG, which was subsequently ruled out.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Alishba Ashraf Khan: Investigation; methodology; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Shamaila Mumtaz: Conceptualization; investigation; methodology; writing – original draft. Javeria Malik: Investigation; methodology; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Muhammad Shahzad Manzoor: Investigation; methodology; writing – review and editing. Faran Maqbool: Investigation; methodology; writing – review and editing. Mudassir Shafique: Investigation; methodology; writing – review and editing. Maheen Nazir: Investigation; methodology; writing – review and editing. Zohad Ibn‐e‐Shad: Investigation; methodology; writing – review and editing. Kamal Kandel: Supervision; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing.

FUNDING INFORMATION

The authors received no funding for this work from anywhere.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

CONSENT

Written informed consent was taken from the patient to publish this report in accordance with the journal's patient consent policy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

Khan AA, Mumtaz S, Malik J, et al. Primary Sjogren's syndrome presenting as ptosis and eyelid swelling: A case report. Clin Case Rep. 2024;12:e8554. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.8554

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data and supporting files of this article are available from the first and corresponding author on reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Kassan SS, Moutsopoulos HM. Clinical manifestations and early diagnosis of Sjögren syndrome. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(12):1275‐1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Amador‐Patarroyo MJ, Arbelaez JG, Mantilla RD, et al. Sjogren's syndrome at the crossroad of polyautoimmunity. J Autoimmun. 2012;39:199‐205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Acs M, Caffery B, Barnett M, et al. Customary practices in the monitoring of dry eye disease in Sjogren's syndrome. Aust J Optom. 2018;11(4):232‐241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhu JW, Wang JY. Eyelid swelling and primary Sjögren's syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2013;27(368):2501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Akpek EK, Bunya VY, Saldanha IJ. Sjögren's syndrome: more than just dry eye. Cornea. 2019;38(5):658‐661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hartert M, Melcher B, Huertgen M. Association of early‐onset myasthenia gravis and primary Sjögren's syndrome: a case‐based narrative review. Clin Rheumatol. 2022;1:1‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sidén Å, Lindahl G. Signs of Sjögren's syndrome in a patient with myasthenia gravis. Acta Neurol Scand. 1990;81(2):179‐180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fujiu K, Kanno R, Shio Y, Ohsugi J, Nozawa Y, Gotoh M. Triad of thymoma, myasthenia gravis and pure red cell aplasia combined with Sjögren's syndrome. Jpn J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;52(7):345‐348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rousseff RT. Diagnosis of myasthenia gravis. J Clin Med. 2021;10(8):1736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Benatar M. A systematic review of diagnostic studies in myasthenia gravis. Neuromuscul Disord. 2006;16(7):459‐467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Robinson MA, Nagurla SR, Noblitt TR, Almaghlouth NK, Al‐Rahamneh MM, Cashin LM. Falsely positive fourth generation ADVIA centaur® HIV antigen/antibody combo assay in the presence of autoimmune hepatitis type I (AIH). IDCases. 2020;1(21):e00886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dasgupta A, Banerjee SK, Datta P. False‐positive troponin I in the MEIA due to the presence of rheumatoid factors in serum: elimination of this interference by using polyclonal antisera against rheumatoid factors. Am J Clin Pathol. 1999;112(6):753‐756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bolstad N, Warren DJ, Nustad K. Heterophilic antibody interference in immunometric assays. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;27(5):647‐661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cole LA, Rinne KM, Shahabi S, Omrani A. False‐positive hCG assay results leading to unnecessary surgery and chemotherapy and needless occurrences of diabetes and coma. Clin Chem. 1999;45(2):313‐314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shiboski CH, Shiboski SC, Seror R, et al. 2016 ACR‐EULAR classification criteria for primary Sjögren's syndrome: a consensus and data‐driven methodology involving three international patient cohorts. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69(1):35‐45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gupta S, Ferrada MA, Hasni SA. Pulmonary manifestations of primary Sjögren's syndrome: underlying immunological mechanisms, clinical presentation, and management. Front Immunol. 2019;12(10):1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Soto‐Cardenas MJ, Perez‐De ‐Lis M, Bove A, et al. Bronchiectasis in primary Sjögren's syndrome: prevalence and clinical significance. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2010;28(5):647‐653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data and supporting files of this article are available from the first and corresponding author on reasonable request.