Abstract

Background

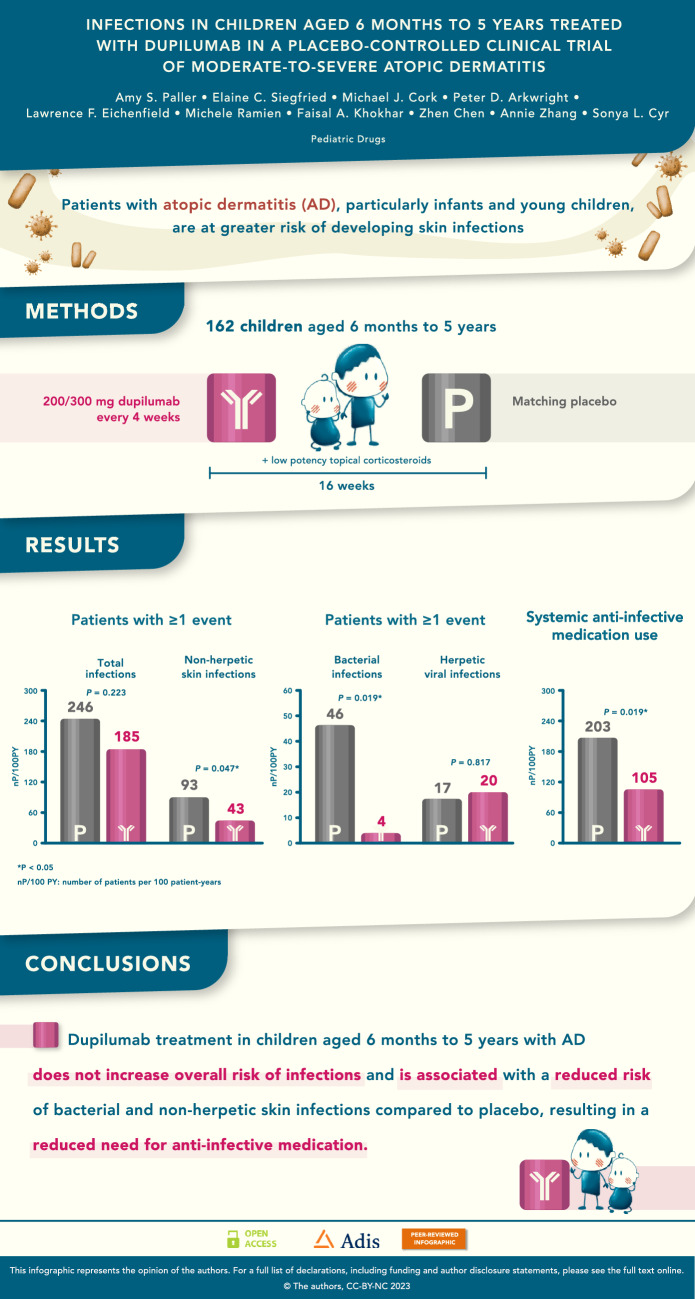

Patients with atopic dermatitis (AD), particularly infants and young children, are at greater risk of developing skin infections. In this study, we assessed infection rates in AD patients aged 6 months to 5 years treated with dupilumab.

Methods

In LIBERTY AD PRESCHOOL, a double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III clinical trial, children aged 6 months to 5 years with moderate-to-severe AD were randomized 1:1 to subcutaneous dupilumab or placebo, with concomitant low-potency topical corticosteroids, every 4 weeks for 16 weeks. Exposure-adjusted infection rates were used to compare treatment groups.

Results

The analysis included 162 patients, of whom 83 received dupilumab and 79 received placebo. Total infection rates were not significantly different between the dupilumab and placebo groups (rate ratio [RR] 0.75, 95% CI 0.48–1.19; p = 0.223). Non-herpetic adjudicated skin infections and bacterial infections were significantly less frequent with dupilumab versus placebo (non-herpetic skin infections: RR 0.46, 95% CI 0.21–0.99; p = 0.047; bacterial infections: RR 0.09, 95% CI 0.01–0.67; p = 0.019), and the number of patients using systemic anti-infective medication was significantly lower in the dupilumab group (RR 0.52, 95% CI 0.30–0.89; p = 0.019). There were no significant differences in the number of herpetic infections between the dupilumab and placebo groups (RR 1.17, 95% CI 0.31–4.35; p = 0.817). The number of patients with two or more infection events was significantly higher in the placebo group (RR 0.29, 95% CI 0.12–0.68; p = 0.004), and no severe or serious infections (including eczema herpeticum) were observed among patients receiving dupilumab.

Conclusions

These data suggest that dupilumab treatment in infants and children younger than 6 years with AD does not increase overall risk of infections and is associated with a reduced risk of bacterial and non-herpetic skin infections compared with placebo, resulting in a reduced need for anti-infective medication.

Trial Registration

The trial was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov with ID number NCT03346434 on November 17, 2017.

Infographic

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40272-023-00611-9.

Plain Language Summary

Patients with atopic dermatitis (AD), a chronic disease of the skin, are at greater risk of developing skin infections, particularly infants and young children. Several medications for AD may weaken the patient’s immune system, further increasing the risk of infections. Dupilumab is a recently developed drug for AD that should not interfere with the patient’s immune defenses against bacterial, viral, or fungal infections. In this study, we evaluated the effect of dupilumab on infections in children aged 6 months to 5 years with moderate-to-severe AD. Patients received 200 or 300 mg of dupilumab (depending on the child’s weight) or placebo, together with ointments containing mild steroids, every 4 weeks for 16 weeks. At the end of treatment, total infections were not significantly different between patients receiving dupilumab and placebo. Furthermore, patients receiving dupilumab experienced significantly less bacterial and non-herpetic skin infections and used significantly less anti-infective medication compared with patients receiving placebo. Herpetic infections were also not significantly different between dupilumab- and placebo-treated patients. Finally, significantly more patients in the placebo group experienced two or more infections. This study demonstrates that dupilumab does not increase the risk of infections in infants and young children with AD and can decrease the use of anti-infective medication.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40272-023-00611-9.

| Digital Features for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.24718977 |

Key Points

| In this randomized clinical trial that included 162 children aged 6 months to 5 years with moderate-to-severe AD, total infections were not significantly different between the dupilumab and placebo groups. |

| Rates of adjudicated non-herpetic skin infections and bacterial infections and the number of patients using anti-infective medications were significantly lower in the dupilumab group. |

| Overall safety was consistent with the known safety profile of dupilumab. |

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) has an estimated prevalence ranging from 3.3% to 18.7% in infants and children younger than 6 years; one of the highest across all ages [1]. Patients with AD—particularly pediatric patients [2]—are at greater risk of developing cutaneous infections due to skin barrier defects and aberrant immune responses [3]. Skin infections commonly associated with AD in infants and young children include staphylococcal infections, molluscum contagiosum, and herpetic infections [3, 4]. In particular, AD patients are at increased risk of eczema herpeticum, which may be so severe as to be disfiguring or life-threatening [2].

Traditional systemic medications used to treat AD may increase the risk of skin infections due to their immunosuppressive properties [5, 6]. Dupilumab, a fully human monoclonal antibody that targets the interleukin (IL)-4 receptor-alpha, selectively blocks the dysregulated signaling of IL-4 and IL-13 cytokines, and theoretically should not interfere with the primary host defense mechanisms against bacterial, viral, or fungal infections [7–9]. Previous studies in children aged 6 months to 11 years [10, 11], adolescents [12], and adults [13] showed that dupilumab significantly improved AD signs and symptoms compared with placebo with an acceptable safety profile. In children aged 6–11 years and adolescents, dupilumab treatment was associated with a lower risk of skin infections compared with placebo, and was not associated with a higher risk of overall infections [14]. In adults, dupilumab treatment did not increase overall infections and was associated with decreased rates of bacterial and other non-herpetic skin infections [15].

The aim of this analysis was to report the impact of dupilumab treatment on infections, including skin infections, in children aged 6 months to 5 years with moderate-to-severe AD.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This was a post-hoc analysis of data from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03346434 Part B) in patients aged 6 months to 5 years with moderate-to-severe AD (defined as Investigator’s Global Assessment [IGA] score of 3–4 at baseline). Details of the trial design are reported in the primary study results [10]. Patients were randomized 1:1 to placebo or subcutaneous dupilumab (200 mg if baseline weight ≥5 kg to <15 kg, 300 mg if ≥15 kg to <30 kg) every 4 weeks (q4w) during a 16-week treatment period. All patients received concomitant low-potency topical corticosteroids (TCS), starting 2 weeks before baseline. Patients with an active chronic or acute infection requiring treatment with systemic antibiotics, antivirals, antiprotozoals, or antifungals within 2 weeks before the baseline visit were excluded from the study.

Endpoints

Endpoints were based on treatment-emergent adverse events reported during the treatment period and described according to the System Organ Class (SOC), High Level Group Term (HLGT), High Level Term (HLT), and Preferred Term (PT) of the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA, https://www.meddra.org/how-to-use/support-documentation/english). The following endpoints were included:

Total infections (SOC)

Infections leading to treatment discontinuation

Severe or serious infections, according to standard criteria for determining seriousness and severity: severe = intense events that may interfere with the patient’s normal daily activities; serious = posing a threat to the patient’s life or normal functioning

Non-herpetic skin infections (manually adjudicated by the study’s clinical director)

- Herpes viral infections (HLT), including the following PTs:

-

oHerpes simplex

-

oHerpes virus

-

oEczema herpeticum

-

oHerpes zoster

-

oPrimary varicella zoster virus

-

oOral herpes

-

o

Non-skin infections (including all adverse events in the SOC ‘total infections’ minus ‘non-herpetic skin infections’ and HLT herpes viral infections)

Bacterial infections (HLGT)

Viral infections (HLGT)

Fungal infections (HLGT)

Helminthic infections (HLGT)

Skin structures and soft tissue infections (HLT) that fall within the HLGT category of ‘pathogens unspecified’

For manually adjudicated non-herpetic skin infections, the study’s clinical director reviewed the list of SOC ‘total infections’ and used medical judgment to determine which of these events were skin infections.

Statistical Analysis

The analysis included all patients who received at least one dose of dupilumab or placebo (safety set). The exposure-adjusted number of patients with one or more event and the exposure-adjusted number of patients with two or more events are presented for each endpoint. Confidence intervals (CI) were calculated using normal approximation. Rate ratios (RR) and p-values are from a Poisson regression model, with treatment as a fixed factor. P-values were derived by a Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test stratified by study identifier and baseline disease severity (IGA = 3 vs IGA = 4), baseline weight group (≥5 kg to <15 kg vs ≥15 kg to <30 kg), and region (North America vs Europe).

Results

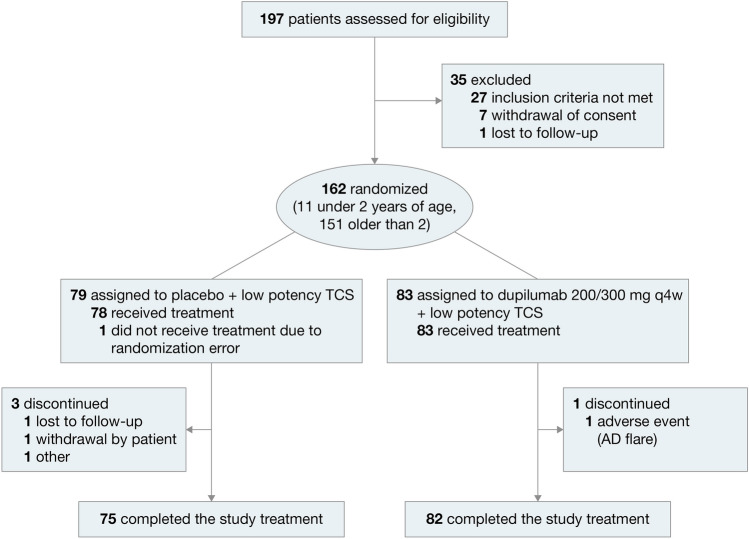

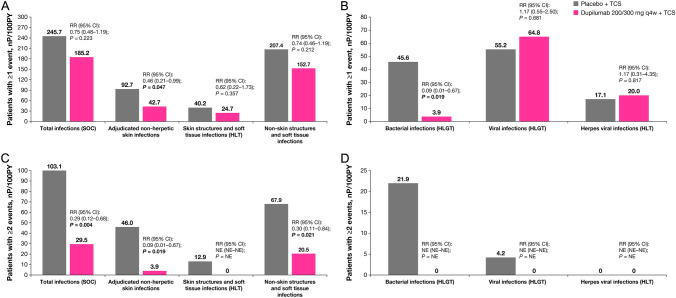

A total of 162 patients (mean age approximately 4 years; 61% male) were randomized to dupilumab (n = 83) or placebo (n = 79) (Fig. 1). At week 16, total infection rates were not significantly different between dupilumab-treated and placebo-treated patients (RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.48–1.19; p = 0.223; Table 1, Fig. 2A). In the placebo group, 40 patients/16.3 patient-years (PY) had one or more infections, compared with 35 patients/18.9 PY in the dupilumab group (Table 1, Fig. 2A). However, the exposure-adjusted number of patients with two or more infections was significantly lower in the dupilumab group (RR 0.29, 95% CI 0.12–0.68; p = 0.004; Table S1 [see electronic supplementary material, ESM], Fig. 2C), with 20 patients/19.4 PY having two or more infection events in the placebo group versus 7 patients/23.7 PY in the dupilumab group (Table S1 [see ESM], Fig. 2C). Severe and serious infections were rare and only occurred in the placebo group (4 patients/23.4 PY, Table 1), and no infections leading to treatment discontinuation occurred in either group (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram of the clinical trial. AD atopic dermatitis, q4w every 4 weeks, TCS topical corticosteroids

Table 1.

Exposure-adjusted numbers of patients with treatment-emergent infections during the study treatment period

| Patients with ≥1 event, nP/PY (nP/100 PY) | RR vs placebo (95% CI), p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo + TCS (n = 78) | Dupilumab 200/300 mg q4w + TCS (n = 83) | ||

| Total infections (SOC) | 40/16.3 (245.7) | 35/18.9 (185.2) |

0.75 (0.48–1.19) 0.223 |

| Infections leading to treatment discontinuation (SOC) | 0/24.0 | 0/25.8 |

NE (NE–NE) NE |

| Serious or severe infections | 4/23.4 (17.1) | 0/25.8 |

NE (NE–NE) NE |

| Serious infections | 3/23.6 (12.7) | 0/25.8 |

NE (NE–NE) NE |

| Severe infections | 4/23.4 (17.1) | 0/25.8 |

NE (NE–NE) NE |

| Adjudicated skin infections (excluding herpes infections) | 19/20.5 (92.7) | 10/23.4 (42.7) |

0.46 (0.21–0.99) 0.047 |

| Non-skin infections1 | 36/17.4 (207.4) | 31/20.3 (152.7) |

0.74 (0.46–1.19) 0.212 |

| Herpes viral infections (HLT) | 4/23.3 (17.1) | 5/25.0 (20.0) |

1.17 (0.31–4.35) 0.817 |

| Herpes virus infections (PT) | 0/24.0 | 2/25.6 (7.8) |

NE (NE–NE) NE |

| Eczema herpeticum (PT) | 1/23.9 (4.2) | 0/25.8 |

NE (NE–NE) NE |

| Herpes zoster (PT) | 0/24.0 | 0/25.8 |

NE (NE–NE) NE |

| Varicella (PT) | 0/24.0 | 2/25.4 (7.9) |

NE (NE–NE) NE |

| Oral herpes (PT) | 2/23.7 (8.4) | 1/25.5 (3.9) |

0.47 (0.04–5.13) 0.532 |

| Herpes simplex (PT) | 1/23.7 (4.2) | 0/25.8 |

NE (NE–NE) NE |

| Bacterial infections (HLGT) | 10/21.9 (45.6) | 1/25.4 (3.9) |

0.09 (0.01–0.67) 0.019 |

| Viral infections (HLGT) | 12/21.7 (55.2) | 15/23.2 (64.8) |

1.17 (0.55–2.50) 0.681 |

| Fungal infections (HLGT) | 1/23.8 (4.2) | 0/25.8 |

NE (NE–NE) NE |

| Helminthic infections (HLGT) | 0/24.0 | 0/25.8 |

NE (NE–NE) NE |

| Skin structures and soft tissue infections (HLT)2 | 9/22.4 (40.2) | 6/24.3 (24.7) |

0.62 (0.22–1.73) 0.357 |

CI confidence interval, HLGT MedDRA High Level Group Term, HLT MedDRA High Level Term, MedDRA Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities, NE not estimated, nP number of patients, PT MedDRA Preferred Term, PY patient-years, q4w every 4 weeks, RR rate ratio, SOC MedDRA System Organ Class, TCS topical corticosteroids

1Includes all adverse events in the SOC ‘Total infections’ except adjudicated non-herpetic skin infections and the HLT ‘Herpes viral infections’

2Only includes infections that fall within HLGT category of ’pathogens unspecified’

Significant differences (p < 0.05) are indicated in bold

Fig. 2.

Exposure-adjusted numbers of patients with ≥1 (A, B) or ≥2 (C, D) treatment-emergent infection events during the study treatment period. CI confidence interval, HLGT MedDRA High Level Group Term, HLT MedDRA High Level Term, MedDRA Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities, NE not estimated, nP/100 PY number of patients per 100 patient-years, PT MedDRA Preferred Term, q4w every 4 weeks, RR rate ratio, SOC MedDRA System Organ Class, TCS topical corticosteroids

Bacterial infections were significantly less frequent in patients treated with dupilumab compared with placebo (RR 0.09, 95% CI 0.01–0.67; p = 0.019; Table 1, Fig. 2B), with 10 patients/21.9 PY having one or more bacterial infection in the placebo group, and 1 patient/25.4 PY in the dupilumab group at week 16. Only patients in the placebo group had two or more bacterial infections (5 patients/22.8 PY; Table S1 [see ESM], Fig. 2D). Treatment-emergent bacterial infections (MedDRA PT) that were recurrent in the placebo group (≥2 infection events) included impetigo, paronychia, staphylococcal skin infection, and furuncle (Table S2, see ESM). No helminthic infections occurred in either group, while one patient in the placebo group had a fungal infection (Table 1). Viral infection rates were not significantly different between the dupilumab and placebo groups (RR 1.17, 95% CI 0.55–2.50; p = 0.681; Table 1, Fig. 2B), affecting 12 patients/21.7 PY in the placebo group and 15 patients/23.2 PY in the dupilumab group. No patients had two or more fungal infections, while one patient in the placebo group had two or more viral infections (Table S1 [see ESM], Fig. 2D).

Non-herpetic adjudicated skin infections were significantly less frequent in dupilumab-treated patients (RR 0.46, 95% CI 0.21–0.99; p = 0.047; Table 1, Fig. 2A), with 19 patients/20.5 PY in the placebo group and 10 patients/23.4 PY in the dupilumab group. The exposure-adjusted number of patients with two or more non-herpetic adjudicated skin infections was also significantly higher in the placebo group (RR 0.09, 95% CI 0.01–0.67; p = 0.019; Table S1 [see ESM], Fig. 2C), with 10 patients/21.7 PY having two or more infection events in the placebo group versus 1 patient/25.5 PY in the dupilumab group. Skin structures and soft tissue infection rates (HLT), representing infections that fall within the HLGT category of ‘pathogens unspecified’, were included for completeness; these were not significantly different between dupilumab-treated and placebo-treated patients (RR 0.62, 95% CI 0.22–1.73; p = 0.357; Table 1, Fig. 2A), affecting 9 patients/22.4 PY in the placebo group and 6 patients/24.3 PY in the dupilumab group. Only patients in the placebo group had two or more skin structures and soft tissue infections (3 patients/23.3 PY; Table S1 [see ESM], Fig. 2C).

The incidence of herpes infections was not significantly different between placebo- and dupilumab-treated patients (RR 1.17, 95% CI 0.31–4.35; p = 0.817; Table 1, Fig. 2B) at week 16. A total of 4 patients/23.3 PY had one or more herpes infections in the placebo group, compared with 5 patients/25.0 PY in the dupilumab group. Regarding generalized herpes infections, varicella only occurred in the dupilumab group (2 patients/25.4 PY), but eczema herpeticum was only observed in the placebo group, affecting 1 patient/23.9 PY (Table 1). No patients had two or more herpes infections (Table S1 [see ESM], Fig. 2D). Furthermore, cases of molluscum contagiosum were numerically more frequent in dupilumab-treated patients, with 4 patients/25.2 PY in the dupilumab group versus 2 patients/23.7 PY in the placebo group (Table 2).

Table 2.

Treatment-emergent infections (by MedDRA PT, under SOC ‘Infections and infestations’) by incidence rate: number of patients per 100 PY

| System Organ Class (SOC) Preferred Term (PT) |

Patients with ≥1 event, nP/PY (nP/100 PY) | |

|---|---|---|

| Placebo + TCS (n = 78) | Dupilumab 200/300 mg q4w + TCS (n = 83) | |

| Total infections | 40/16.3 (245.7) | 35/18.9 (185.2) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 7/22.7 (30.9) | 7/24.5 (28.6) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 6/22.9 (26.2) | 5/24.8 (20.1) |

| Molluscum contagiosum | 2/23.7 (8.4) | 4/25.2 (15.9) |

| Conjunctivitis | 0/24.0 | 3/25.5 (11.8) |

| Gastroenteritis viral | 0/24.0 | 3/25.4 (11.8) |

| Impetigo | 6/22.9 (26.2) | 3/25.1 (12.0) |

| Herpes virus infection | 0/24.0 | 2/25.6 (7.8) |

| Varicella | 0/24.0 | 2/25.4 (7.9) |

| Bronchitis | 0/24.0 | 1/25.6 (3.9) |

| COVID-19 | 1/23.7 (4.2) | 1/25.5 (3.9) |

| Cellulitis | 1/23.8 (4.2) | 1/25.4 (3.9) |

| Coronavirus infection | 0/24.0 | 1/25.5 (3.9) |

| Croup infectious | 1/23.8 (4.2) | 1/25.8 (3.9) |

| Dermatitis infected | 1/23.9 (4.2) | 1/25.5 (3.9) |

| Keratitis viral | 0/24.0 | 1/25.5 (3.9) |

| Oral herpes | 2/23.7 (8.4) | 1/25.5 (3.9) |

| Otitis media | 0/24.0 | 1/25.5 (3.9) |

| Otitis media acute | 2/23.6 (8.5) | 1/25.6 (3.9) |

| Paronychia | 1/23.8 (4.2) | 1/25.5 (3.9) |

| Pustule | 0/24.0 | 1/25.5 (3.9) |

| Skin infection | 1/23.7 (4.2) | 1/25.6 (3.9) |

| Respiratory tract infection viral | 3/23.2 (12.9) | 0/25.8 |

| Staphylococcal skin infection | 3/23.3 (12.9) | 0/25.8 |

| Ear infection | 2/23.6 (8.5) | 0/25.8 |

| Skin bacterial infection | 2/23.5 (8.5) | 0/25.8 |

| Viral upper respiratory tract infection | 2/23.6 (8.5) | 0/25.8 |

| Abscess limb | 1/23.9 (4.2) | 0/25.8 |

| Cellulitis staphylococcal | 1/23.9 (4.2) | 0/25.8 |

| Eczema herpeticum | 1/23.9 (4.2) | 0/25.8 |

| Furuncle | 1/23.8 (4.2) | 0/25.8 |

| Gastroenteritis | 1/23.8 (4.2) | 0/25.8 |

| Genital candidiasis | 1/23.8 (4.2) | 0/25.8 |

| Herpes simplex | 1/23.7 (4.2) | 0/25.8 |

| Pharyngitis | 1/24.0 (4.2) | 0/25.8 |

| Respiratory syncytial virus infection | 1/23.9 (4.2) | 0/25.8 |

| Staphylococcal abscess | 1/23.7 (4.2) | 0/25.8 |

| Staphylococcal bacteremia | 1/23.7 (4.2) | 0/25.8 |

| Staphylococcal infection | 1/23.8 (4.2) | 0/25.8 |

| Superinfection | 1/23.9 (4.2) | 0/25.8 |

MedDRA Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities, nP number of patients, PT MedDRA Preferred Term, PY patient-years, q4w every 4 weeks, SOC MedDRA System Organ Class, TCS topical corticosteroids

Non-skin infection rates were not significantly different between the placebo and dupilumab group (RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.46–1.19; p = 0.212; Table 1, Fig. 2A), affecting 36 patients/17.4 PY in the placebo group and 31 patients/20.3 PY in the dupilumab group. However, the exposure-adjusted number of patients with two or more non-skin infections was significantly lower in the dupilumab group (RR 0.30, 95% CI 0.11–0.84; p = 0.021; Table S1 [see ESM], Fig. 2C), with 14 patients/20.6 PY having two or more infection events in the placebo group versus 5 patients/24.4 PY in the dupilumab group. Nasopharyngitis and upper respiratory tract infection were the most frequent treatment-emergent infections (MedDRA PT) in both treatment arms (Table 2). Conjunctivitis and viral gastroenteritis were numerically more frequent in the dupilumab group compared with the placebo group (Table 2), and nasopharyngitis was the only recurrent infection in the dupilumab group, with one patient having two or more nasopharyngitis events (Table S2, see ESM). Nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory tract infection, and acute otitis media were recurrent in the placebo group (Table S2, see ESM).

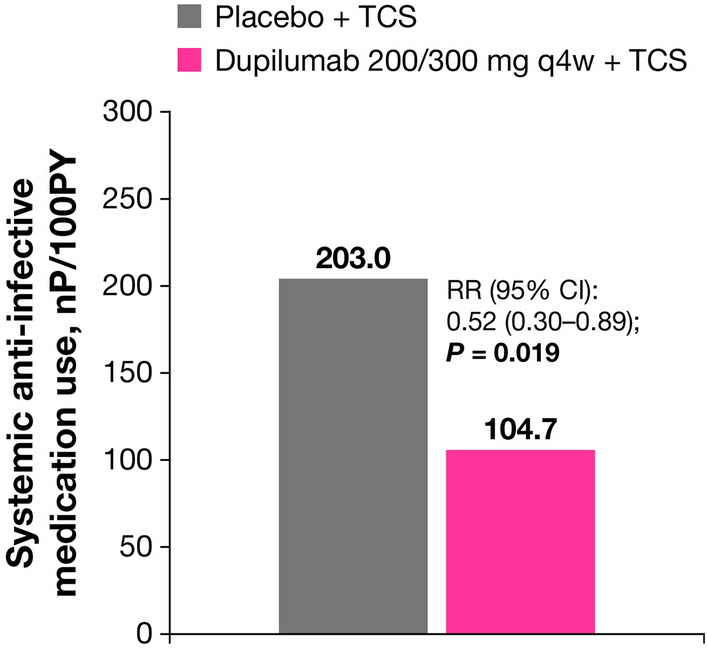

Systemic anti-infective medication use was significantly lower in the dupilumab group compared with the placebo group (RR 0.52, 95% CI 0.30–0.89; p = 0.019; Fig. 3). In the placebo group, 32 patients/15.8 PY were administered systemic anti-infective medication during the study, compared with 21 patients/20.0 PY in the dupilumab group (Table S3, see ESM). The most frequently used systemic anti-infective medications included cefalexin, clindamycin, amoxicillin, sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, and cefdinir in the placebo group and cefalexin, clindamycin, and acyclovir in the dupilumab group (Table S3, see ESM).

Fig. 3.

Exposure-adjusted number of patients using anti-infective medication during the study treatment period. CI confidence interval, nP/100 PY number of patients per 100 patient-years, q4w every 4 weeks, RR rate ratio, TCS topical corticosteroids

Discussion

In this analysis of data from a randomized, placebo-controlled, phase III clinical trial of 16 weeks in children aged 6 months to 5 years with moderate-to-severe AD, treatment with dupilumab did not lead to an increase in total infection rates. Adjudicated non-herpetic skin infections and bacterial infections were significantly less frequent in dupilumab-treated than placebo-treated patients, and anti-infective medication use was significantly lower in the dupilumab-treated group than in the placebo group. Severe and/or serious infections were rare and only reported in the placebo group.

Compared with older age groups [14], the rate of herpetic infections was relatively high (17.1 and 20.0 patients/100 PY in the placebo and dupilumab groups, respectively), which may be related to the severity of AD and young age of this population. In a previous pooled analysis of children aged 6–11 years with severe AD and adolescents with moderate-to-severe AD, rates of herpetic infections were 14.7 and 5.0 patients/100 PY in the placebo and dupilumab groups (approved doses), respectively [14]. In the present analysis, one case of eczema herpeticum was observed in the placebo group and two varicella cases were observed in the dupilumab group. Nevertheless, dupilumab treatment did not lead to a significant increase in viral infections, including herpetic infections, and the antiviral drug acyclovir was prescribed to the same number of patients from both treatment groups. Although an increase in molluscum contagiosum infections was observed in the dupilumab group compared with placebo, cases were mild and did not lead to treatment discontinuation. Dupilumab treatment was associated with an increased incidence of conjunctivitis, as reported in previous publications of dupilumab clinical trials [16, 17]; however, as previously described, conjunctivitis of non-infectious etiology may be reported as the MedDRA PT conjunctivitis, which falls under the SOC ‘Infections and infestations’ for the purposes of safety analysis [14]. Furthermore, the rate of conjunctivitis in the dupilumab group (11.8 patients/100 PY) was lower in the present study compared with adults (16.36 patients/100 PY) [18] and pediatric patients aged 6–17 years (12.6 patients/100 PY) [14].

Although total infection rates were not significantly different between treatment groups, the number of patients with more than one infection event was significantly higher in the placebo group. In the dupilumab group, patients rarely had more than one infection. Only patients in the placebo group had two or more bacterial or viral infections, and the number of patients with two or more adjudicated skin infections or non-skin infections was significantly higher in the placebo group. Nasopharyngitis was the only infection that occurred more than once to the same patient in the dupilumab group; several infections were recurrent in the placebo group, including staphylococcal skin infection, impetigo, furuncle, paronychia, otitis media acute, upper respiratory tract infection, and nasopharyngitis.

The effect of dupilumab treatment on infection rates in infants and children younger than 6 years is consistent with previous published results of pediatric, adolescent, and adult populations [14, 15]. Treatment with dupilumab might decrease infection rates due to improved skin barrier integrity, as dupilumab inhibits overabundance of type 2 cytokines that dysregulate the expression of key skin barrier proteins and antimicrobial peptides [19–22]. Furthermore, dupilumab reduces itching, thus decreasing scratch-related mechanical damage, and promotes skin microbiome diversity by limiting colonization and abundance of Staphylococcus aureus [20].

This analysis provides additional evidence to characterize the safety profile of dupilumab in infants and young children, and confirms that the safety profile of dupilumab in this young age group is similar to that observed in older age groups. Limitations of this study include its short treatment duration (16 weeks) and relatively small number of patients (n = 162), particularly the small number of patients under 2 years of age (n = 11).

Conclusion

In a randomized, placebo-controlled, phase III trial of dupilumab in infants and children aged up to 5 years with moderate-to-severe AD, dupilumab treatment with concomitant low-potency TCS was not associated with an increase in infection rates compared with placebo. Adjudicated non-herpetic skin infections and bacterial infections were significantly less frequent in patients treated with dupilumab compared with placebo, and serious or severe infections were not observed in the dupilumab group. There was no difference in the number of herpetic infections observed. The number of patients with two or more infections was significantly lower in the dupilumab group. Dupilumab was generally well tolerated with an acceptable safety profile.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

This research was sponsored by Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc.; ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03346434. Medical writing/editorial assistance was provided by Alessandra Iannino, PhD, of Excerpta Medica, and was funded by Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., according to the Good Publication Practice Guidelines. The authors would like to thank the patients and their caregivers for their participation, and publication managers Adriana Mello of Sanofi and Linda Williams of Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., who provided support and input. The National Institute for Health and Care Research provided support to the Manchester Clinical Research Facility at the Royal Manchester Children’s Hospital.

Declarations

Funding

This research was sponsored by Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03346434. The study sponsors participated in the study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; writing of the report; and the decision to submit the article for publication. Medical writing and editorial assistance was provided by Alessandra Iannino, PhD, of Excerpta Medica, and was funded by Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., according to the Good Publication Practice Guidelines. 10.7326/M22-1460.

Competing Interests

Dr Paller reported serving as an investigator, consultant, and/or data and safety monitoring board member for AbbVie, Abeona Therapeutics, Amryt Pharma, Azitra, BioCryst, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Castle Creek Biosciences, Catawba Research, Dermavant, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Incyte, InMed Pharmaceuticals, Janssen, Krystal Biotech, LEO Pharma, Novartis, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., Sanofi, Seanergy, TWi Biotechnology, and UCB. Dr Siegfried reported serving as a consultant, data safety monitoring board member, and/or principal investigator in clinical trials for Dermavant, Eli Lilly, GSK, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Novan, Pfizer, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., Stiefel, and Verrica Pharmaceuticals. Dr Cork reported serving as an investigator and/or consultant for AbbVie, Astellas Pharma, Boots, Dermavant, Galapagos, Galderma, Hyphens Pharma, Johnson & Johnson, LEO Pharma, L’Oréal, Menlo Therapeutics, Novartis, Oxagen, Pfizer, Procter & Gamble, Reckitt Benckiser, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., and Sanofi. Dr Arkwright reported acting as an investigator for Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc. and receiving grants from and acting as an advisor for Sanofi. Dr Eichenfield reported receiving honoraria for consulting services and/or research support from AbbVie, Amgen, Arcutis, Aslan, Bausch, BMS, Castle Biosciences, Dermavant, Eli Lilly, Forté Pharma, Galderma, Incyte, Novartis, Otsuka, Pfizer, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., Sanofi, and UCB. Dr Ramien reported serving as a consultant, speaker, and/or investigator for AbbVie, Eli Lilly, LEO Pharma, Pfizer, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., and Sanofi. Drs Khokhar, Chen, and Cyr are employees and shareholders of Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc. Dr Zhang is an employee of and may hold stock and/or stock options in Sanofi.

Availability of Data and Material

Qualified researchers may request access to study documents (including the clinical study report, study protocol with any amendments, blank case report form, and statistical analysis plan) that support the methods and findings reported in this manuscript. Individual anonymized participant data will be considered for sharing once the product and indication have been approved by a regulatory body, if there is legal authority to share the data and there is not a reasonable likelihood of participant re-identification. Submit requests to https://vivli.org/.

Ethics Approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and applicable regulatory requirements. An independent data and safety monitoring committee conducted blinded monitoring of patient safety data. The local institutional review board or ethics committee at each study center oversaw trial conduct and documentation. All patients, or their parents/guardians, provided written informed consent before participating in the trial. Pediatric patients provided assent according to the Ethics Committee (Institutional Review Board/Independent Ethics Committee)-approved standard practice for pediatric patients at each participating center.

Consent to Participate

For each patient, written informed consent was obtained from a parent or legal guardian.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

A.S. Paller, E.C. Siegfried, M.J. Cork, and P.D. Arkwright acquired data. Z. Chen conducted the statistical analyses on the data. All authors interpreted the data, provided critical feedback on the manuscript, approved the final manuscript for submission, and are accountable for the accuracy and integrity of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Silverberg JI, Barbarot S, Gadkari A, et al. Atopic dermatitis in the pediatric population. A cross-sectional, international epidemiologic study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021;126(4):417–428. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2020.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ellis CN, Mancini AJ, Paller AS, Simpson EL, Eichenfield LF. Understanding and managing atopic dermatitis in adult patients. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2012;31(3 Suppl):S18–22. doi: 10.1016/j.sder.2012.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ong PY, Leung DYM. Bacterial and viral infections in atopic dermatitis: a comprehensive review. Clinic Rev Allerg Immunol. 2016;51(3):329–337. doi: 10.1007/s12016-016-8548-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spergel JM, Paller AS. Atopic dermatitis and the atopic march. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112(6):S118–S127. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paller AS, Simpson EL, Eichenfield LF, Ellis CN, Mancini AJ. Treatment strategies for atopic dermatitis: optimizing the available therapeutic options. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2012;31(3 Suppl):S10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.sder.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part II. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(6):850–878. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gandhi NA, Pirozzi G, Graham NMH. Commonality of the IL-4/IL-13 pathway in atopic diseases. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2017;13(5):425–437. doi: 10.1080/1744666X.2017.1298443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Le Floc’h A, Allinne J, Nagashima K, et al. Dual blockade of IL-4 and IL-13 with dupilumab, an IL-4Rα antibody, is required to broadly inhibit type 2 inflammation. Allergy. 2020;75(5):1188–1204. doi: 10.1111/all.14151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Annunziato F, Romagnani C, Romagnani S. The 3 major types of innate and adaptive cell-mediated effector immunity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135(3):626–635. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paller AS, Simpson EL, Siegfried EC, et al. Dupilumab in children 6 months to younger than 6 years with uncontrolled atopic dermatitis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2022;400(10356):908–919. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01539-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paller AS, Siegfried EC, Thaçi D, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab with concomitant topical corticosteroids in children 6 to 11 years old with severe atopic dermatitis: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(5):1282–1293. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simpson EL, Paller AS, Siegfried EC, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adolescents with uncontrolled moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. A phase 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(1):44–56. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simpson EL, Bieber T, Guttman-Yassky E, et al. Two phase 3 trials of dupilumab versus placebo in atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(24):2335–2348. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1610020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paller AS, Beck LA, Blauvelt A, et al. Infections in children and adolescents treated with dupilumab in pediatric clinical trials for atopic dermatitis—a pooled analysis of trial data. Pediatr Dermatol. 2022;39(2):187–196. doi: 10.1111/pde.14909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eichenfield LF, Bieber T, Beck LA, et al. Infections in dupilumab clinical trials in atopic dermatitis: a comprehensive pooled analysis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2019;20(3):443–456. doi: 10.1007/s40257-019-00445-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akinlade B, Guttman-Yassky E, de Bruin-Weller M, et al. Conjunctivitis in dupilumab clinical trials. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181(3):459–473. doi: 10.1111/bjd.17869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bansal A, Simpson EL, Paller AS, et al. Conjunctivitis in dupilumab clinical trials for adolescents with atopic dermatitis or asthma. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2021;22(1):101–115. doi: 10.1007/s40257-020-00577-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blauvelt A, de Bruin-Weller M, Gooderham M, et al. Long-term management of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis with dupilumab and concomitant topical corticosteroids (LIBERTY AD CHRONOS): a 1-year, randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10086):2287–2303. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31191-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guttman-Yassky E, Bissonnette R, Ungar B, et al. Dupilumab progressively improves systemic and cutaneous abnormalities in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143(1):155–172. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Callewaert C, Nakatsuji T, Knight R, et al. IL-4Rα blockade by dupilumab decreases Staphylococcus aureus colonization and increases microbial diversity in atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2020;140(1):191–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2019.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haddad EB, Cyr SL, Arima K, et al. Current and emerging strategies to inhibit type 2 inflammation in atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2022;12(7):1501–1533. doi: 10.1007/s13555-022-00737-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leung DYM, Bissonnette R, Kreimer S, et al. Dupilumab inhibits vascular leakage of blood proteins into atopic dermatitis skin. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2023;11(5):1421–1428. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2023.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.