Abstract

Among individuals with a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders (ASD), conversation topic preference could influence social skills in many ways. For example, an individual with advanced vocal-verbal skills, but just learning to join a conversation, might be less inclined to participate if the topic chosen is not preferred. However, commonly used preference assessment procedures have not been applied to evaluating conversation-topic preferences. Therefore, the purpose of the current experiment was to conduct three different types of assessments that varied in efficiency, the degree of certainty they allow, and clients with whom they are likely to be applicable and acceptable. In particular, we conducted a self-report preference assessment, a multiple-stimulus-without-replacement (MSWO) preference assessment, and a response restriction conversation assessment (RRCA). Each assessment identified a preferred topic of conversation, but the RRCA was the only assessment that was able to differentiate which topics would maintain a conversation. Implications for assessment and intervention procedures related to complex social skills are discussed and directions for future research are proposed.

Keywords: autism, conversation, preference assessment, social interaction

Many behavior analysts provide services to individuals diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD; Burning Glass Technologies & Behavior Analyst Certification Board [BACB], 2022; Graff & Karsten, 2012). Considering preferences of social stimuli among individuals diagnosed with ASD is important because ASD is characterized in part by a lack of interest in social interaction and corresponding behavioral differences, such as failure to reciprocate conversations (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013). However, recent research has shown that several differentially reinforcing types of social interaction can be identified for children with ASD (e.g., Kelly et al., 2014; Morris & Vollmer, 2019) and that these social interactions can support socially directed responding (e.g., Morris & Vollmer, 2020b) and facilitate skill acquisition (e.g., Morris & Vollmer, 2020a). Thus, social interactions may function as effective reinforcers for individuals with and without ASD. Social reinforcers might include the delivery of vocal (e.g., praise) or physical stimuli (e.g., tickles) as well as more extended interactions such as parallel or cooperative engagement with an activity (e.g., playing a board game) or conversation about a preferred topic (e.g., talking about movies).

Social reinforcers in general, and conversation in particular, offer several advantages relative to other types of stimuli, such as edible or leisure reinforcers. First, and most important, utilizing preferred conversation topics as reinforcers could be more ecologically valid. Behavior analysts are obligated to prioritize the least restrictive procedures and avoid the use of harmful reinforcers (BACB, 2020, Guidelines 2.09, 2.13, 2.14, 2.15, 3.01). Conversation topics are less intrusive or restrictive to deliver than edible or leisure reinforcers and other types of social reinforcers (e.g., hide-and-seek, tickles). Moreover, given that conversation is ubiquitous in many natural environments, the use of preferred topics as reinforcers may minimize the risk of stigmatization.

Second, conversation is ubiquitous and naturalistic; preferred conversation topics may support much of our behavior in the school, workplace, and community. Therefore, relative to other types of social reinforcers or edible and leisure reinforcers, using preferred conversation topics as reinforcers may have higher social or ecological validity. Moreover, using preferred topics as reinforcers during skill acquisition may facilitate the generalization and maintenance of behavior change because the same reinforcers are readily available in the natural environment (Stokes & Baer, 1977).

Third, preferred conversation topics may be especially useful when teaching social skills and this may be the context in which the aforementioned benefits are the most pronounced. For example, therapists could use preferred topics when teaching a client to initiate conversations with peers (e.g., discuss something you enjoy talking about) or provide access to conversation about a preferred topic contingent on more discrete conversational skills (e.g., greeting peers, terminating a conversation appropriately). Stocco et al. (2021) demonstrated that contingent access to reportedly preferred topics was effective in increasing on-topic conversation and decreasing off-topic conversation. Methods to systematically identify preferred conversation topics could increase the effectiveness of such interventions by ensuring the most preferred topics were being used. Moreover, methods of producing a valid hierarchy of preferred conversation topics could allow for differential reinforcement of independent versus prompted on-topic conversation that could improve intervention effectiveness. Thus, methods of assessing preference for conversation topics may allow for more effectiveness, more socially valid, and more ecologically valid interventions.

Despite the potential utility, no methods of systematically obtaining a hierarchy of conversation topic preferences have been evaluated. However, some researchers have evaluated vocally mediated preference assessments in which the therapist’s vocal-verbal behavior served as the stimuli to be selected from and the client’s vocal-verbal behavior served as the selection response. Northup et al. (1996) compared participant-reported hierarchies from surveys, a vocally mediated paired stimulus preference assessment (PSPA), and a picture-based PSPA in terms of their accuracy in identifying the most preferred classes of stimuli relative to a reinforcer assessment for individuals between the ages of 6 and 9. Northup et al. found that the survey was only accurate for 55% of participants, whereas the vocally mediated and picture-based PSPAs were both accurate for 70% of participants. Tessing et al. (2006) compared vocally mediated PSPAs for activities with and without access to the activity selected for seven boys between the ages of 11 and 18. They found that PSPAs with access to the activity were more accurate. Finally, Morris and Vollmer (2020b) demonstrated that a vocally mediated PSPA for social interactions produced accurate hierarchies for all three participants with whom it was conducted.

Given the success of vocally mediated preference assessments described above, such assessments may represent an effective and naturalistic method for assessing preference for conversation topics. However, no methods of obtaining a hierarchy of preference for conversation topics have been evaluated, so the best method of doing so remains unclear. The optimal method of assessing conversation topic preferences will vary depending on the client with whom the assessment is to be conducted. These context or client-specific variables may inform procedural details such as the prompts and discriminative stimuli used, the primary dependent variable (e.g., selection, conversation), whether access to conversation topics is provided, whether repeated measures are included, and the amount of data collected. One reason procedural details may vary is efficiency. That is, some contexts (e.g., weekly, 1-hr appointments) may require more efficient assessments than others (e.g., daily, 3-hr appointments after school) due to time constraints or the relative importance of conversation and social skill acquisition relative to other goals.

Another reason procedural details may vary is the degree of certainty required about the hierarchy produced. Although accuracy of an assessment should be highly valued for all contexts and procedures, there should be a balance between the efficiency and accuracy of an assessment depending on the context. For example, in some contexts, (e.g., research, implementing differential reinforcement by quality) it may be important to be relatively certain or confident that the assessment has produced an accurate hierarchy of relative reinforcer efficiency than in other contexts (e.g., identifying the most preferred topic to use for a single assessment or intervention session). Likewise, more certainty may be required if conversation is to be used as a reinforcer for unestablished chains of behavior (e.g., in teaching conversation or social skills) than if conversation is to be used as a reinforcer for established, low-effort responses (e.g., to support the maintenance of mastered skills). Furthermore, considerations of a procedure’s applicability and acceptability must be considered for each client. That is, different methods may be more applicable to some clients than others based on the skills currently in their repertoire (e.g., some can describe a hierarchy of their preferences or respond to questions about their preferences, whereas some cannot). Different methods may vary in their efficiency, the degree of certainty or confidence they allow, and their applicability and acceptability for different clients. In an ideal situation, clinicians and researchers could select from a continuum of methods based on the needs and characteristics of the client with whom and context in which they are working.

Thus, the purpose of the study was to identify potential assessment methods that could be used to systematically assess conversation topic preferences. Each method can yield a hierarchy of preference for different conversation topics, but they vary in efficiency, the degree of certainty they allow, and clients with whom they are likely to be applicable and acceptable. In particular, with each participant, we conducted a self-report preference assessment in which the participant simply reported their hierarchy of preference, a multiple-stimulus-without-replacement (MSWO; DeLeon & Iwata, 1996) preference assessment in which the participants made selections from topics that were represented vocally and textually and selections were followed by brief access to the selected topic, and a response restriction conversation assessment (RRCA; using similar procedures to those of Hanley et al., 2003) in which the participants were prompted to converse about whatever they preferred and topics were restricted after the participant consistently allocated responding to that topic.

Method

Participants and Setting

Five individuals diagnosed with ASD were recruited to participate. James was a 15-year-old male whose caregivers reported he was unable to develop and maintain friendships with peers in his school due to his limited interest in conversation topics. James would often only talk about three different video games and the subject of physics. Victor was a 17-year-old male whose topics of interest included school activities, music, and dating. Damien was a 10-year-old male whose topics of interest often included various theme parks (e.g., Magic Kingdom, Epcot) and topics related to history (e.g., Queen Victoria). Leo was a 9-year-old male whose topics of interest included the subject of mathematics, various video games, and his family. Alex was a 13-year-old male whose interests included military transport (e.g., airplanes, helicopters, tanks), video games, and comics. All participants were enrolled in classrooms with materials and curricula typical for their age and they were able to read and write at or near their age level. No academic skill deficits were indicated for any participants, according to parent and teacher reports and our informal observations.

Sessions were conducted at a local autism clinic (Damien, Leo, and Victor) or a university clinic (James and Alex). Session rooms included a table and chairs. No other stimuli were available during sessions. Assessments required a total of roughly 30–45 min to complete and were conducted in one day with approximately a 5-min break between each. Assessments were conducted once with all participants except Damien, who completed it twice roughly 8 weeks apart (i.e., Damien[a] and Damien [b]). We conducted a second assessment with Damien because we observed changes in conversational topics he elected to speak about outside of the study.

It is important to note that all participants and their families had contacted the first author because limited social skills had resulted in problems developing and maintaining friendships in school. Enrollment in the current investigation was part of an ongoing series of assessments and interventions that occurred during a single 1-hr weekly appointment that included general conversation skills such as asking questions, engaging in small talk, and learning to identify when a conversation partner was interested in the conversation topic (Kronfli et al., 2022).

Procedures

Self-Report Preference Assessment

During the self-report preference assessment, we asked each participant to list four topics they like to talk about, in order from most to least preferred. We asked participants to list the topics as opposed to ranking a list, so we did not limit participants from electing a topic that had previously not been preferred. The primary dependent variable during the self-report preference assessment was the vocal utterance emitted by the participant. We did not provide any examples to minimize the potential for biasing responses for certain topics and did not ask any clarifying questions to determine if the order the topics were presented were ranked from most to least preferred. If 30 s elapsed without a response, we asked “Are there any other topics you like to talk about?” If the participant did not respond within 10 s or indicated they were finished (e.g., “I think that’s all”), we stopped and continued to the MSWO preference assessment. Alex was the only participant who did not identify four preferred topics. If the participant began to talk about the topic, we said “We can talk about that soon, I just want a list of your favorite topics right now.” Thus, the order in which participants reported each topic produced a hierarchy of preference. Self-report preference assessment typically required about 1 min to complete.

Multiple-Stimulus-without-Replacement Preference Assessment

We wrote the topics provided by the participant during the self-report preference assessment on index cards for the MSWO preference assessment. They were randomly placed on a table in front of the participant. We then asked the participant to pick one topic to talk about with us. The primary dependent variable was either the vocal utterance emitted (i.e., naming the card) by the participant or the index card they physically selected (e.g., pointing). After the topic was chosen, we removed all the index cards from the table, said, “Tell me about [topic],” and allowed the participant to lead the discussion for 30–45 s. We responded to every statement with general comments indicating interest (e.g., “That sounds cool!”) but avoided directing the conversation or providing information about our own experiences unless explicitly asked by the participant. For example, if a participant said, “My favorite game is Minecraft,” we said something like “That’s cool. I hear it’s really fun,” as opposed to “I don’t like that game, I prefer racing games.” We used general, neutral comments so that participants' preferences for conversation topics were not influenced by the conversation partner's comments or the content of the conversation itself. After 30–45 s had elapsed, we re-presented the remaining topics in random order and asked the participant to pick one topic. This was repeated until (1) all topics had been chosen, (2) the participant did not choose a topic for 30 s, or (3) the participant asked or requested to stop (e.g., “I’m done” or “I don’t want to talk about the rest of those”). If at any time, the participant began talking about another topic, we would have redirected toward the chosen topic by saying “We’re talking about [topic] now,” but this did not occur. Thus, the order in which participants reported the number of selections over the number of trials available produced a hierarchy of preference. MSWO preference assessments typically required about 3.5 min to complete.

Response Restriction Conversation Assessment

The RRCA began when the experimenter said, “You can talk about anything you want. That includes [the list of topics chosen during self-report and MSWO preference assessment].” We collected data on the percentage of intervals during which the participant talked about a topic using a 10-s partial interval data collection method. The primary dependent variable was vocalizations that occurred for at least 2 consecutive seconds. Examples of vocalizations included mands, tacts, and intraverbals. Nonexamples of vocalizations included “fillers” such as “umm” or “ahh.” Vocalizations were categorized as falling under one of the topics previously identified or as an unreported topic. Although it did not occur, vocalizations could include multiple topics across one 10-s interval. For example, Alex might emit vocalizations about comics during the first 5 s of the 10-s interval, followed by vocalizations about video games during the second 5 s of the 10-s interval. Similar to the responses during the MSWO preference assessment, we responded to all statements with general comments indicating interest but avoided directing the conversation or providing information about our own experiences unless explicitly asked by the participant. What we observed throughout the assessment was that participants would speak about a single topic until it met removal criteria, then chose a different topic to discuss. To facilitate experimental control and assessment clarity we chose to make the conversation more one-sided (i.e., "perseverative") so the experimenter avoided biasing participants responding by differentially responding to some topics and not others.

Participants could talk about any topic until a given topic met removal criteria, which included (1) talking about any topic for at least five out of six 10-s intervals for 2 consecutive minutes; (2) talking about any topic for at least three out of six 10-s intervals for 3 consecutive minutes; or (3) any two or more topics discussed for greater than two out of six 10-s intervals for 3 consecutive minutes, which would remove all topics that were discussed. These criteria were developed based on those described by Hanley et al. (2003) and Morris and Vollmer (2019) such that removal of the topic was based on the stability of vocalizations across intervals. After a topic met removal criteria, we told the participant, “Now you can talk about anything you want, except [the topics that have met removal criteria].” This continued until (1) all topics had met removal criteria; (2) 2 min elapsed without the participant emitting a vocalization; (3) the participant manded to stop; or (4) a topic was discussed for fewer than one out of six 10-s intervals for 3 consecutive minutes. Thus, the order in which topics met the criteria for removal in the RRCA produced a hierarchy of preferred conversation topics.

Interobserver Agreement

Responses were independently recorded during the sessions by two data collectors for 100% of sessions, and interobserver agreement (IOA) was 100% across all participants. IOA was calculated for the self-report and MSWO preference assessments by dividing the total number of selections in which both observers agreed on the item selected by the total number of selections in the session and multiplied by 100. Interval-by-interval IOA was calculated for the RRCA by dividing the total number of 10-s intervals in which both observers agreed that a conversation topic occurred during the interval divided by the total number of intervals multiplied by 100. For intervals in which multiple topics were recorded, both observers had to record each topic for that interval to be scored as an agreement. However, this did not occur.

Results

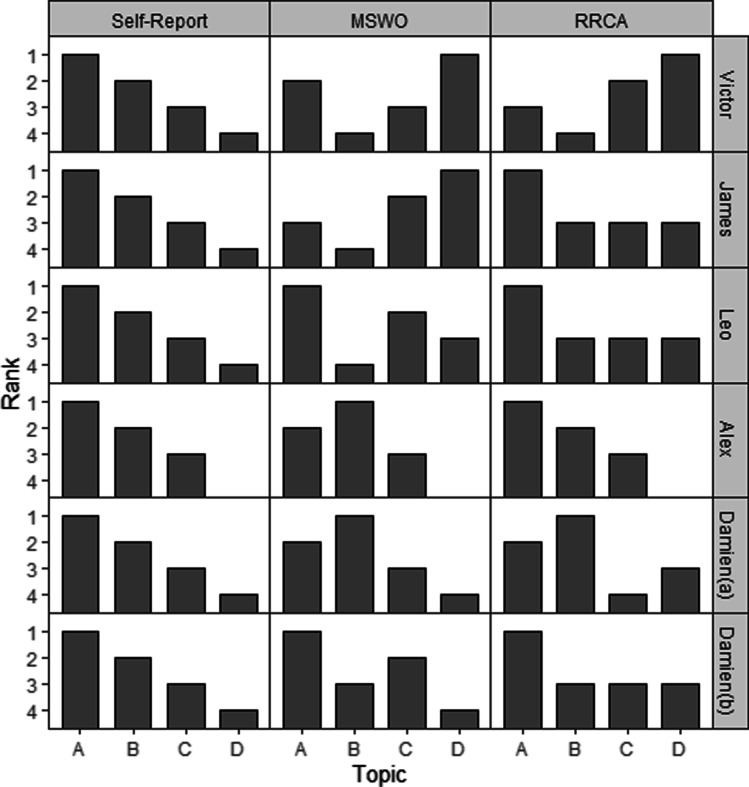

Table 1 provides specific conversation topics reported by each participant. Topics are listed in the order they were reported, selected, or met criteria for removal in the self-report preference assessment, MSWO preference assessment, and RRCA, respectively. Figure 1 provides the resulting stimulus rank for each topic across each assessment type. The graphs depict the self-report preference assessment hierarchy on the left, the MSWO preference assessment hierarchy in the middle, and the RRCA hierarchy on the right.

Table 1.

Hierarchy of Topic Preference Produced by Self-Report Preference Assessments, MSWO Preference Assessments, and Response Restriction Conversation Assessments (RRCA)

| Participant | Self-Report | MSWO | RRCA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Victor |

Black Midi (A) Dating (B) School (C) Gossiping (D) |

Gossiping (D) Black Midi (A) School (C) Dating (B) |

Gossiping (D) School (C) Black Midi (A) Dating (B) |

| James |

Subnautica (A) (VG) Physics (B) Minecraft (C) (VG) Memes (D) |

Memes (D) Minecraft (C) Subnautica (A) Physics (B) |

Subnautica (A) |

| Leo |

Roblox (A) (VG) Pokemon (B) Math (C) Sister (D) |

Roblox (A) Math (C) Sister (D) Pokemon (B) |

Roblox (A) Other |

| Alex |

Military (A) Video Games (B) Comics (C) |

Video Games (B) Military (A) Comics (C) |

Military (A) Video Games (B) Comics (C) |

| Damien (a) |

Topsail (A) Versailles (B) Magic Kingdom (C) Epcot (D) |

Versailles (B) Topsail (A) Magic Kingdom (C) Epcot (D) |

Versailles (B) Topsail (A) Epcot (D) Magic Kingdom (C) |

| Damien (b) |

Disney Parks (A) Mad Libs (B) Queen Victoria (C) Vacation (D) |

Queen Victoria (C) Disney Parks (A) Mad Libs (B) Vacation (D) |

Disney Parks (A) |

Fig. 1.

Preference Assessment Outcomes by Method

The top panels of Fig. 1 display Victor’s data. For Victor, all assessments generated different hierarchies, although the MSWO preference assessment and RRCA both identified the same most and least preferred conversation topics. The second panels of Fig. 1 display James’s data. For James, the self-report and MSWO preference assessments generated inconsistent hierarchies, although the same topic was identified as most preferred during the self-report preference assessment and the RRCA. The third panels of Fig. 1 display Leo’s data. For Leo, the self-report and MSWO preference assessments generated different hierarchies, but all assessments identified the same topic (A, Roblox) as the most preferred. The fourth panels of Fig. 1 display Alex’s data. For Alex, the self-report preference assessment and RRCA generated identical hierarchies. However, the first and second most preferred topics switched when comparing the MSWO preference assessment to the self-report preference assessment and the RRCA. The fifth panels of Fig. 1 display Damien’s data from his first series of assessments (denoted with an “a”). During this series, the self-report preference assessment, MSWO preference assessment, and RRCA generated similar hierarchies. The first- and second-most preferred topics switched during the self-report preference assessment and the MSWO preference assessment. A similar pattern was observed between the MSWO preference assessment and the RRCA hierarchies of the third- and fourth-most preferred conversation topics, in which the hierarchy switched. The bottom panels of Fig. 1 display Damien’s data from his second series of assessments (denoted with a “b”). During this series, the self-report and MSWO preference assessments generated somewhat discrepant hierarchies, but all assessments identified the same topics as the most preferred (A, Queen Victoria).

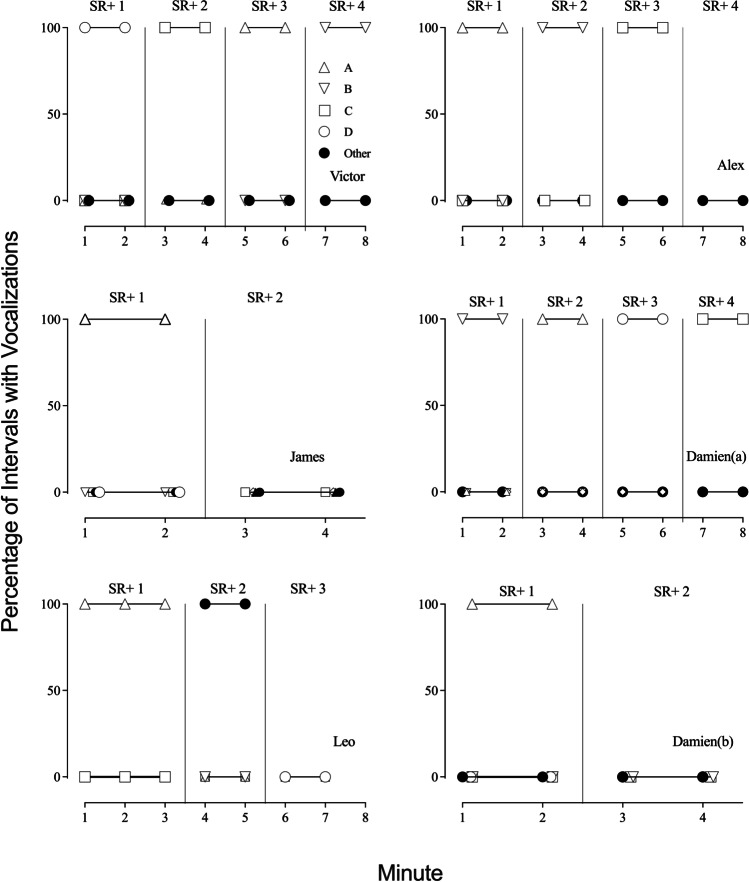

Figure 2 displays minute-by-minute responding for the RRCA across participants. James and Damien(b)'s RRCA required 4 min to complete, both choosing not to converse with the experimenter after speaking about the first topic chosen, which were Subnautica for James and Disney parks for Damien(b). Leo’s RRCA required 6 min to complete and he was the only participant to choose a new topic (labeled as other) that was not discussed during the self-report or MSWO preference assessment. Victor and Damien(a)’s RRCA each required 8 min to complete and both participants talked about each topic chosen in the previous self-report and MSWO preference assessment. Alex spoke about all three topics he had chosen during the self-report and MSWO preference assessment.

Fig. 2.

Minute-by-Minute Responding for the RRCA across Participants. Note. This figure displays the occurrence of conversation for each of the reported preferred topics as well as all other topics. Data are displayed across each minute of the RRCA and SR+ refers to reinforcement

Discussion

This study was the first application of preference assessment procedures for identifying and evaluating preference for conversation topics. A continuum of three different types of assessments were conducted that varied in efficiency, the degree of certainty they allow, and clients with whom they are likely to be applicable and acceptable. Each assessment identified a preferred topic of conversation. However, the RRCA was the only assessment that was able to differentiate between which topics would maintain a conversation and which would not, as indicated by James, Leo, and Damien(b)’s assessments.

Thus, the RRCA was the only assessment that showed whether or not it would support conversation and clarified absolute or relative reinforcer effectiveness for conversation topics. The self-report and MSWO preference assessments also frequently did so, but the RRCA is the only assessment that suggested which topics were sufficiently reinforcing to maintain conversation and systematically restricted conversation topics in such a way that their relative and absolute value as reinforcers for conversation became apparent. This is important when considering the degree of certainty that is necessary when identifying the most reinforcing conversation topics (e.g., identifying a conversation topic that can function as a potent reinforcer would require a higher degree of certainty when teaching novel skills as opposed to a mastered skill). This was observed in James, Leo, and Damien’s second assessment. Although hierarchies were observed when using the self-report and MSWO preference assessments, participants stopped talking after one topic (James and Damien) or two topics (Leo), suggesting the RRCA would offer a higher degree of certainty when the goal is to identify conversation topics that are likely to support responding. However, when simply identifying conversational topics that provide insight into an individual’s preferences, regardless of their success as reinforcers, self-report preference assessments might be sufficient. That is, self-report measures provide researchers and practitioners with a tool that can be conducted frequently and efficiently. This can be useful when topics help determine if conversational topics are fluctuating and can be repeated if topics are broad (e.g., video games). For example, although James was specific about the types of video games he enjoyed talking about, Alex gave us the broad topic of video games as a preferred topic. However, during the RRCA, he spoke exclusively about one video game and expressed that it was the only game he enjoyed playing.

It is important to consider applicability before implementing any of these procedures. Depending on the individual, the procedures might be viewed as cumbersome or redundant (e.g., MSWO preference assessment). In fact, on multiple occasions, James asked experimenters why we wrote down the conversation topics during the MSWO preference assessment when he just told us what he liked talking about (during the self-report preference assessment). These are factors that should be considered, rather than using each of these procedures as standard practice across individuals.

That being said, our results suggest that the self-report and MSWO preference assessments could still be useful for several reasons. The self-report and MSWO preference assessments each identified the same most preferred topic as the RRCA for five out of six participants, but it remains unclear what variables may impact the utility of their results. The self-report and MSWO preference assessments always produced a complete hierarchy of preference, whereas the RRCA often identified the highest preferred but indicated that all other stimuli were insufficiently reinforcing to maintain conversation. The more complete hierarchies produced by the self-report and MSWO preference assessments could be useful in evaluating the relative value of different topics as reinforcers for responses that are less effortful than vocal conversation from the participants' perspective (e.g., texting, maintaining posture, smiling). Self-report preference assessment hierarchies may also be less susceptible to problems arising from talking about a given topic for an extended period. For example, once one talks about their most preferred topic at length, it may no longer be the most reinforcing topic. Furthermore, this might be important if these are conversation topics individuals want to listen to, rather than speak about. For example, an individual might enjoy the topic of animals, but they enjoy learning about animals (e.g., asking questions) rather than contributing novel information to the conversation. Thus, all three of the assessments evaluated in the current study may be useful for clinicians and researchers. The most suitable choice may depend on the level of certainty and efficiency required, the specific behavior to be evaluated or addressed, as well as the individual involved and the surrounding circumstances in which it will take place. For example, during nonstudy-related assessments, many of the participants dissented or expressed displeasure with repeated exposure to assessment conditions making statements including “You’ve already asked me that,” “We did this last time,” and “I’m not doing that again.” It is also possible that an assessment such as the MSWO preference assessment would not be feasible if the participants were unable to read the stimuli presented.

The diagnostic criteria for ASD suggest that social interactions such as conversations may be unlikely to function as reinforcers (APA, 2013). However, the current study suggests that preferred and differentially reinforcing conversation topics can be identified and adds to the growing body of evidence suggesting social reinforcers can be identified readily for this population (e.g., Butler & Graff, 2021; Clay et al., 2018; Davis et al., 2021; Huntington & Higbee, 2018; Morris & Vollmer, 2019, 2020a, b, c, d, 2021, 2022; Wolfe et al., 2018). Thus, the use of social reinforcers may be especially relevant to providing services to those diagnosed with ASD and particularly useful in the assessment and improvement of social skills. In general, the identification and use of social reinforcers could allow for more effective (DeLeon et al., 2009; Egel, 1981; Tiger et al., 2006), naturalistic (DeLeon et al., 2013), and ecologically valid (BACB, 2020. Guidelines 2.09, 2.13, 2.14, 2.15, 3.01) assessments and interventions. Moreover, the use of preferred conversation topics as reinforcers would be less stigmatizing than other types of reinforcers, especially when assessments or interventions are implemented in the natural environment.

The current study extends the literature on vocal preference assessments (Northup et al., 1996; Tessing et al., 2006; Morris & Vollmer, 2020b) by evaluating preference for conversation topics among individuals diagnosed with ASD who have relatively sophisticated vocal-verbal repertoires. This study also suggests that vocal responses can be used in place of selection or approach. For example, simply asking participants to report their hierarchy of topic preference often identified the most reinforcing topic. The RRCA also extends a small subset of preference and reinforcer assessments that have evaluated preference and relative reinforcer effectiveness by making all options available and only removing stimuli from the array when stability in selection or allocation has been obtained (Hanley et al., 2003; preference and reinforcer assessment; Morris & Vollmer, 2019, 2020c).

There are several limitations to the current study and corresponding future directions. First, we conducted three types of assessments that differed in several ways. It is unclear which differences may have contributed to variance in the hierarchy produced by these assessments. For example, the self-report preference assessment only involved asking the participants to list their preferred topics in order of preference, whereas the MSWO preference assessment required participants to make selections from a list of their preferred topics that were presented vocally and in written form. Future research should evaluate differences between preference assessments for conversation topics that include only vocal stimuli to topics that include vocal stimuli and written or pictorial stimuli. In addition, it would be useful for future research to evaluate the differences between assessments that do or do not provide access to stimuli reported or selected (as in Wolfe et al., 2018). Researchers could also evaluate other methods of systematically asking participants about their preferred topics, such as the PSPA (Fisher et al., 1992; Morris & Vollmer, 2020b; Tessing et al., 2006); however, some participants might find more repetitive and time-consuming procedures to be aversive and this should be taken into consideration.

Second, during the RRCA for three of the six datasets, only one of the participant’s reported topics met the criteria for removal before they stopped talking or requested to stop talking (i.e., the end of the assessment). Future research should evaluate variations of the RRCA used in the current study that increase the likelihood that participants will continue to talk throughout the assessment instead of requesting to stop talking after being told they could no longer talk about their most preferred topic. Although we based our removal criteria on those used in previous research, that may be one procedural characteristic that could influence the assessment results. For example, if removal criteria allowed for more conversation about a given topic before it was removed, then the participants may be less likely to stop talking after their most preferred topic is removed. The relative occurrence of conversation about a topic may be indicative of the relative reinforcing effectiveness of that topic. When there are no restrictions on which topics may be discussed, no programmed discriminative stimuli, and no differential reinforcement contingencies for conversing about one topic over another, then differential discussion about a given topic may provide a measure of the relative value of automatic reinforcers produced by that topic (e.g., talking about sports, visualizing sports, remembering sport-related past events; Skinner, 1957). The RRCA was designed to emulate these conditions and provide a measure of preference for, and the relative reinforcing value of each topic in the absence of prompts or differential social reinforcement in favor of a specific topic (i.e., the same general, positive responses were always provided). Within the set of available topics (i.e., all topics were available or after some had met removal criteria), we considered the topic(s) that occurred most consistently to be the most reinforcing. We also considered any topics that maintained participants’ conversation to be reinforcing.

Third, we did not collect procedural fidelity data. Behaviors that should be collected to ensure responding is consistent across topics include general comments (e.g., “That’s cool!”) to ensure the experimenter did not ask questions that might evoke responding and a positive affect (e.g., smiling, consistent inflection changes). This would mitigate the possibility that it is the experimenter’s behavior, rather than the conversation topic, that maintains responding.

Fourth, regarding clinical utility, our study provides a useful first step in identifying preference for conversation topics. The self-report and MSWO preference assessments are more efficient and provide a complete hierarchy of preference, which can be useful in evaluating the relative value of different topics as reinforcers for responses that are less effortful than vocal conversation from the participants' perspective. On the other hand, the RRCA is the only assessment that provides a higher degree of certainty when identifying the most reinforcing conversation topics that can function as potent reinforcers, especially when teaching novel skills. However, practitioners should also consider applicability and acceptability before implementing any of these procedures, as they might be viewed as cumbersome or redundant by some individuals. It would be important to investigate how different variables may affect the utility of the results from each assessment. For example, the self-report and MSWO preference assessments may be less susceptible to problems arising from talking about a given topic for an extended period. In addition, repeated exposure to assessment conditions may not be acceptable for some individuals. Future research should aim to investigate how these assessments can be modified to improve their clinical utility and acceptability for different individuals.

Finally, it is important to note that there is currently no validated assessment for identifying preference for conversation topics. Therefore, it is essential to reframe this study as preliminary and to identify assessment methods that can reliably identify preference for conversation topics. Future research should focus on validating these methods and demonstrating their correspondence with other methods. In addition, it would be useful to conduct reinforcer assessments for arbitrary and socially valid tasks, such as mastered and unmastered social skills and interactions, to further validate the utility of preferred conversation topics as reinforcers.

In summary, the current study evaluated whether a self-report preference assessment, MSWO preference assessment, and RRCA could identify a hierarchy of preferred conversational topics. All three methods produced preference hierarchies in a relatively efficient manner with individuals with ASD who have complex vocal-verbal repertoires. Clinicians and researchers assessing and improving conversation or social skills should consider and assess the topic preferences of the individuals with whom they work, as the resulting hierarchies may allow for more effective and ecologically valid interventions. The current study provides a starting point in terms of procedures for effectively doing so. Moving forward, it will be important to continue to refine these procedures and evaluate the utility of preferred conversation topics. The use of conversation topics as reinforcers could improve methods of assessing and improving conversation skills but should not be limited to this area. Conversation topics could be just as effective as edible and leisure stimuli and may constitute a more socially and ecologically valid alternative for a variety of assessments and interventions.

Declarations

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2020). Ethics code for behavior. https://bacb.com/ethics-code/. Accessed 8/1/2023

- Burning Glass Technologies & Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2022). Workforce demand in the field of behavior analysis: 2022 report. https://www.bacb.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/2022-Workforce-Demand-Report_Final.pdf. Accessed 8/1/2023

- Butler C, Graff RB. Stability of preference and reinforcing efficacy of edible, leisure, and social attention stimuli. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2021;54(2):684–699. doi: 10.1002/jaba.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clay CJ, Samaha AL, Bogoev BK. Assessing preference for and reinforcing efficacy of components of social interaction in individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Learning and Motivation. 2018;62:4–14. doi: 10.1016/j.lmot.2017.03.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davis T, Weston R, Hodges A, Gerow S. Comparison of picture-and video-presentation preference assessments for social interactions. Journal of Behavioral Education. 2021;31:367–387. doi: 10.1007/s10864-020-09402-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeLeon, I. G., Bullock, C. E., & Catania, A. C. (2013). Arranging reinforcement contingencies in applied settings: Fundamentals and implications of recent basic and applied research. In APA handbook of behavior analysis, Vol. 2: Translating principles into practice (pp. 47–75). American Psychological Association.

- DeLeon IG, Frank MA, Gregory MK, Allman MJ. On the correspondence between preference assessment outcomes and progressive-ratio schedule assessments of stimulus value. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2009;42(3):729–733. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2009.42-729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLeon IG, Iwata BA. Evaluation of a multiple-stimulus presentation format for assessing reinforcer preferences. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1996;29(4):519–533. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1996.29-519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egel AL. Reinforcer variation: Implications for motivating developmentally disabled children. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1981;14(3):345–350. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1981.14-345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher W, Piazza CC, Bowman LG, Hagopian LP, Owens JC, Slevin I. A comparison of two approaches for identifying reinforcers for persons with severe and profound disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1992;25(2):491–498. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1992.25-491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graff RB, Karsten AM. Evaluation of a self-instruction package for conducting stimulus preference assessments. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2012;45(1):69–82. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2012.45-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley GP, Iwata BA, Lindberg JS, Conners J. Response-restriction analysis: I. Assessment of activity preferences. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2003;36(1):47–58. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2003.36-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huntington RN, Higbee TS. The effectiveness of a video based preference assessment in identifying social reinforcers. European Journal of Behavior Analysis. 2018;19(1):48–61. doi: 10.1080/15021149.2017.1404397. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly MA, Roscoe EM, Hanley GP, Schlichenmeyer K. Evaluation of assessment methods for identifying social reinforcers. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2014;47(1):113–135. doi: 10.1002/jaba.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronfli FR, Vollmer TR, Parks ME, Hack GO. A brief assessment to identify sensitivity to a conversational partner’s interest. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2022;15:838–844. doi: 10.1007/s40617-021-00668-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris SL, Vollmer TR. Assessing preference for types of social interaction. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2019;52(4):1064–1075. doi: 10.1002/jaba.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris SL, Vollmer TR. Evaluating the stability, validity, and utility of hierarchies produced by the social interaction preference assessment. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2020;53(1):552–535. doi: 10.1002/jaba.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris SL, Vollmer TR. A comparison of methods for assessing preference for social interactions. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2020;53(2):918–937. doi: 10.1002/jaba.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris SL, Vollmer TR. A comparison of picture and GIF-based preference assessments for social interaction. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2020;53(3):1452–1465. doi: 10.1002/jaba.680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris SL, Vollmer TR. Evaluating the function of social interaction using time allocation as a dependent measure: A replication and extension. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2020;53(4):2405–2420. doi: 10.1002/jaba.750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris SL, Vollmer TR. Evaluating the function of social interaction for children with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2021;54(4):1456–1467. doi: 10.1002/jaba.850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris SL, Vollmer TR. Increasing social time allocation and concomitant effects on mands, item engagement, and rigid or repetitive behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2022;55(3):814–831. doi: 10.1002/jaba.919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northup J, George T, Jones K, Broussard C, Vollmer TR. A comparison of reinforcer assessment methods: The utility of verbal and pictorial choice procedures. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1996;29(2):201–212. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1996.29-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner, B. F. (1957). Verbal behavior. Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- Stocco CS, Saavedra I, Fakharzadeh S, Patel MR, Thompson RH. A comparison of intervention for problematic speech using reinforcement with and without preferred topics. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2021;54(1):217–230. doi: 10.1002/jaba.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokes TF, Baer DM. An implicit technology of generalization. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1977;10(2):349–367. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1977.10-349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tessing JL, Napolitano DA, McAdam DB, DiCesare A, Axelrod S. The effects of providing access to stimuli following choice making during vocal preference assessments. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2006;39(4):501–506. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2006.56-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiger JH, Hanley GP, Hernandez E. An evaluation of the value of choice with preschool children. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2006;39(1):1–16. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2006.158-04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe K, Kunnavatana SS, Shoemaker AM. An investigation of a video-based preference assessment of social interactions. Behavior Modification. 2018;42(5):729–746. doi: 10.1177/2F0145445517731062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]