Abstract

Incorporating literature into practice can help behavior analysts provide better services and achieve better outcomes. In addition, behavior analysts have an ethical obligation to remain current with the scholarly literature and to use it to inform services. Despite the merits of maintaining regular contact with the published literature, barriers exist to doing so. In this tutorial, we present a system that was created for a human service agency to increase practitioner access to the scholarly literature. The system consisted of an electronic search request form, a literature team, and a liaison. We present 7 years of data including the frequency of use, topics of interest, and other noteworthy patterns of submitter responding. We discuss the value of this type of system, limitations of its design, and considerations for practitioners who may wish to implement a similar system in their agency. We discuss modifications that could be made to fit organizations of diverse sizes and with different resources, while presenting ideas for improvement and expansion of the system.

Keywords: Evidence-based practice, Information literacy, Literature access, Research-to-practice gap, Scientist-practitioner model

The profession of behavior analysis is marked by quickly moving literature, with new information published regularly. Given our reliance on single-case design, we steadily have access to new methodology and novel treatment approaches. There are a variety of reasons behavior-analytic practitioners may wish to consistently access the literature including professional development, training content design, and clinical case decisions. For example, a practitioner may wish to make decisions about the optimal type of preference assessment to use based on a specific client profile (Heinicke et al., 2016), to teach menstrual hygiene skills (Veazey et al., 2016), or to reduce the pace of eating for an autistic client (Valentino et al., 2018). Remaining in contact with this literature and utilizing the literature in practice may support practitioners in applying best clinical practices to their everyday work and help to narrow the research-to-practice gap (Valentino & Juanico, 2020). In addition, practitioners may desire to utilize the literature for various other reasons, including providing effective research-informed supervision (Sellers et al., 2019). In accessing the research literature, practitioners will have the most current knowledge of current standards of practice and will be able to provide the best standard of care, which ultimately may result in high-quality services.

The Behavior Analyst Certification Board’s (BACB; 2020) Ethics Code for Behavior Analysts (hereafter, “the Code”) specifies behavior analysts have the ethical responsibility of relying on behavioral principles and scientific evidence to inform practice (2.01, 2.13, 2.14) and that we must undertake efforts to maintain competence by engaging in professional development activities such as reading the research literature (1.06). Although most practitioners develop the necessary skills to access published literature following their graduate school education, there are barriers that may prevent them from successfully doing so. Bank et al. (2023) found that 80% of professionals in a survey searched for literature at least once per month through academic web searches, university library systems, and the BACB research resource. Of these respondents searching the literature, only 45% reported satisfaction with the resources available to them. Identifying methods to increase practitioner access to and satisfaction with searching the published literature is a noble goal, as this fulfills their ethical obligation, ensures delivery of high-quality services to clients, and does not limit their service delivery to what was considered best practice when they graduated (Dixon et al., 2015; Gillis & Carr, 2014).

Carr and Briggs (2010) published a resource that identified common barriers to accessing and consuming contemporary literature and proposed several solutions for circumventing each barrier that could increase the likelihood of accessing and contacting novel research. Briggs and Mitteer (2022) updated this article to be current with changes to technology and expanded the resources. Many of these barriers were validated by Bank et al. (2023), who demonstrated many participants (37.6%) in a survey study reported subscription or payment requirements functioned as barriers to successful literature searches, and some (26.2%) reported they were not always able to find what they wanted. Briggs and Mitteer acknowledged these barriers, as well as many others, and offered concrete solutions for searching, accessing, and contacting the contemporary literature. These authors identified barriers for searching the literature, which included (1) deciding where to start; (2) the inefficiencies associated with searching individual journal websites; (3) the generation of “false positives” when using general web searches; and (4) limited or costly access to popular search engines. Although some resources exist for credentialed practitioners (e.g., access to various journals and search engines through the BACB’s portal), other barriers such as limited time, competing job contingencies, and difficulty navigating the literature may increase the response effort associated with contacting the literature, reducing the likelihood of practitioners accessing the literature to guide their practice (Carr & Briggs, 2010). Barriers associated with accessing the literature include less than reliable access to journals, expensive journal subscriptions, an overwhelming number of journals to follow, and outdated author contact information. Finally, Briggs and Mitteer identified additional barriers associated with contacting the literature which include the difficulties associated with keeping up with articles, the effort involved in following multiple journals, the constraints on one’s environment for supporting the activity, and limited time to dedicate to reviewing content.

Briggs and Mitteer (2022) and other authors (e.g., Goodfellow, 2004; Gillis & Carr, 2014) have suggested several ways in which practitioners can overcome the barriers associated with searching, accessing, and contacting the literature. Some of these solutions include activities following inexpensive and free journals when possible, signing up for email content alerts, and using self-management procedures. Other authors have also suggested strategies such as monthly journal clubs (Goodfellow, 2004; Parsons & Reid, 2011) and reading annotated bibliographies (Gillis & Carr, 2014). The strategies offered by authors thus far are helpful and practitioners are likely to consume more literature by employing them.

These strategies place incredible onus on the individual practitioner and many of the strategies involve high response effort. Effortful literature searches and difficulty effectively integrating literature into practice may prove to be too much for a field so prone to burnout (Slowiak & DeLongchamp, 2022) and for professionals who report difficulties with work-life balance (Wine et al., 2020). Moreover, depending on competing contingencies (e.g., responding to client needs, report writing, developing treatment plans), a practitioner may allocate responding toward daily tasks associated with their position rather than searching, accessing, and contacting the literature. Carr and Briggs (2010) recommended arranging the contingencies of the work environment to increase the likelihood of a practitioner accessing the literature such as a liaison to the literature. The liaison would be responsible for gathering and disseminating scholarly information to other employees, thereby minimizing the response effort placed on practitioners. Other similar recommendations in that early article included consulting with senior practitioners/researchers to become familiar with relevant content, starting or joining a journal club, and consulting with established clinicians or researchers to become familiar with relevant journals.

In this tutorial, we describe a system that is like the literature liaison recommended by Carr and Briggs (2010). Given that access to a university library is associated with the most satisfaction and confidence in contacting the literature (Bank et al., 2023), but most practitioners do not have access to these types of resources, we sought to create a system within an organization that employs practitioners that would support their literature access. The purpose of our literature request system was to reduce the response effort of accessing the literature, increase satisfaction with the experience of searching the literature and outcomes of doing so, and increase the likelihood that a practitioner’s practice is guided by best practices found in the published literature. The system was designed to ensure that every request resulted in a prompt and relevant response from an experienced member of the team who was familiar with relevant journal content. Therefore, the purposes of this tutorial are to (1) describe the development of the literature request system; (2) describe the process by which the literature request system works; (3) share information about the literature requests that have been received between 2015 and 2022 at our organization; and (4) provide recommendations for other human service organizations that might wish to implement such a system, with a specific focus on modifications that may need to be made to the system to support organizations of diverse sizes and with different resources. We end the tutorial by generating ideas for readers about how a system such as this could be expanded and improved.

System Components

The components of the literature request system consisted of a literature liaison, a literature-access team, a webform embedded into the organization’s company-wide intranet, and journal access through an institutional subscription to PsycINFO. Over the course of time that the organization has employed the literature request system, the size of our organization, the makeup of our staff, the number of clients served, and the states in which we operate have varied (e.g., serving 500 clients across four states vs. serving 1,600 clients across seven states). The components described below have stayed the same despite these size changes. To support organizations in modifying the system to their size, needs, and resources, as we describe each of these components below, we also make recommendations for how the component could be modified. Appendix A Table 1 lists each component, our current iteration of that component, previous iterations, possible modifications, and considerations for implementation.

Table 1.

Descriptions of current and previous iterations of the literature request system and considerations for modifications

| Component | Description of Component, Modifications, and Considerations |

|---|---|

| Literature Liaison | |

| Current Iteration |

• Advanced leadership position (i.e., Senior Director of Severe Behavior) • Management of literature request system in job responsibilities • Responds to or delegates requests • Tracks literature request system metrics |

| Previous Iteration | • Advanced leadership position (i.e., Chief Clinical Officer, Executive Director Of Research And Clinical Standards) |

| Possible Modifications | • Any individual with relevant skills |

| Considerations |

• Relevant skills needed for role • Competing contingencies (e.g., current responsibilities, volume of requests) • Reduction in responsibilities to accommodate work |

| Literature-Access Team | |

| Current Iteration |

• 2 members in advanced leadership positions (i.e., senior director of severe behavior and chief clinical officer) • Respond to requests in professional and timely manner |

| Previous Iteration |

• 2–5 members (e.g., postdoctoral fellows, senior clinical team members, advanced leadership positions) • > 5 years certified, 1 peer-reviewed research article • Voluntary position |

| Possible Modifications |

• Literature liaison only (i.e., no team) with low volume • Greater number of members who complete a small number of requests each month • Specific designated roles with stipends |

| Considerations |

• Volume of requests • Skillset of members • Programmed reinforcers (e.g., training, or mentoring opportunities, small stipend) and capacity to make changes in workload |

| Component | Description of Component, Modifications, and Considerations |

| Webform | |

| Current Iteration |

• 16 questions embedded within organization’s website • Form automatically emailed to literature team |

| Previous Iteration | • General email inquiry form |

| Possible Modifications |

• Designated email • Chat room or group • Drop-down menus for answers • Removal or addition of questions |

| Considerations |

• Information needed by literature-access team to fulfill request • Response effort and time to complete the request by submitter • Behaviors you would like to prompt submitters to engage in prior to making a request |

| Journal Access | |

| Current Iteration |

• PsychInfo Subscription • BACB portal access |

| Previous Iteration | • PsychInfo Subscription |

| Possible Modification | • N/A |

| Considerations | • Organizational needs for nonbehavior-analytic journals that may have relevant content that are not included in the BACB free access |

| Literature Request System | |

| Current Iteration |

• Webform posted on organization’s website • Submitter completes literature request form • Completed form emailed to literature-access team • “Grab and go” method by literature-access team via email • Member of literature-access team conducts search • Emails team member article(s) within 7 days |

| Previous Iteration | • N/A |

| Possible Modification |

• Assign requests in order or based on team expertise • Organize requests via central tracking system • Structured expectations for search process • Place articles in centralized location |

| Considerations |

• Organization’s size and resources • Reasonable response time to meet need of submitted • Storage of found articles |

The Literature Liaison

The literature liaison takes primary responsibility for responding to or delegating literature requests to other members of the literature-access team, as well as tracking basic metrics such as date of submission and date of response. The current literature liaison is the senior director of severe behavior who is a board certified behavior analyst-doctoral (BCBA-D) with experience publishing peer-reviewed articles and conducting editorial work at a high level (e.g., serves as a guest editor and associate editor for several peer-reviewed journals). Three individuals in advanced leadership positions within the organization have served as the literature liaison over the years our system has existed—the executive director of research and clinical standards, the chief clinical officer, and currently the senior director of severe behavior. In our organization, the literature liaison has management of this system as a stated purpose of their job responsibilities and time is allocated to the task accordingly.

Organizations could put any person with the skills needed in the role of literature liaison. In organizations without this type of clinical leadership, a board certified behavior analyst (BCBA) or another clinical team member could take the role. Assigning the role of literature liaison may require a reduction in other responsibilities (e.g., caseload, administrative tasks) to support the effort. In our experience, the workload has been manageable over the years—the ability to respond quickly seemed to be the most important element of making the system work. For individuals conducting client-facing work, driving, and in roles where they may often be disconnected electronically, the task of responding to requests in a timely manner may be more arduous. When the literature liaison cannot respond quickly to requests, the system might be set up such that a dedicated time occurs each week for request review and fulfillment, with the employees aware of this timeline before submitting. Thus, it would be important to consider the skills required for this position, the ability of the person to respond within a reasonable timeframe given their other responsibilities, other competing contingencies, and the volume of requests when selecting an individual for the literature liaison.

The Literature-Access Team

The literature-access team’s primary responsibility is to respond to literature requests in a professional and timely manner (i.e., within 1 week of the initial submission). The current literature-access team is composed of the literature liaison and another BCBA-D in an advanced leadership position (i.e., chief clinical officer). The composition of the literature-access team varied over the 7 years of data reported here and members served on the team voluntarily. Members participated for as long and as frequently as they wished, and we suspect were motivated by several benefits to participation. Some of these benefits include mentorship and interaction by the senior members of the literature-access team, interacting with staff members with whom they might not normally interact, becoming familiar with a novel clinical concern or case relevant to the request(s), and becoming more aware of existing or new literature as a function of having to identify relevant articles. Over the years, the total membership included between two and five team members, most often holding the BCBA-D credential. BCBAs who sat on the committee were individuals who had been certified for 5 years or more and had published at least one peer-reviewed research article. Common positions participating in the literature-access team included postdoctoral fellows, senior clinical staff members interested in research, and advanced leadership positions in the organization (e.g., directors, executive staff members). Our organization had a postdoctoral fellowship program for 3 of the 7 years presented in the current article (i.e., 2015–2018). When the postdoctoral fellows were not employed, the literature liaison managed the system with the support of sometimes one other team member. Although the number of team members varied, we experienced that the system could sustain changes in the size and make-up of the literature-access team when there is a constant literature liaison with time dedicated to the system.

Organizations may wish to modify the literature-access team by only having the literature liaison manage the requests (in situations with low volume) or by having a team of volunteers across the organization who agree to respond to one or two requests per month. Staff members could sit on the literature-access team in exchange for training about how to search the literature, heightened interaction with clinical leadership, additional mentoring opportunities, or even a small stipend. Although we never collected formal data on the amount of time it took for the liaison and literature-access team to complete the work, we hypothesize it varied greatly based on several variables including (1) the volume of requests; (2) the skill set of the liaison or team member; (3) the amount of information provided in the form; (4) the available literature on the topic requested; and (5) the level of complexity of the literature on the topic. We estimate the work related to a request could be conducted within 5 min if the submitter is requesting a specific article but could take as long as 20 min if the submission involves a general inquiry (e.g., teaching verbal behavior to people with visual impairment) and/or a complex population (e.g., a rare chromosomal abnormality not often seen at the clinic).

Literature Request Form

The literature request form was web-based and designed within Google Forms by the primary author and two other clinical leaders employed by the organization at the time of inception. The form consists of demographic variables (e.g., name, position, email address), information about the submitter’s attempts to search the literature, and information about their search request (e.g., looking for a specific article vs. a group of articles, the primary topic of interest). The form is linked into several locations on the organization’s website for easy access by staff employed by the organization. Upon submission, the form automatically emails the literature liaison and members of the literature request team with the details of the request. The form is included below, and a deidentified sample response is included in Appendix C.

Literature Request Form

Email

Full Name

Phone Number

Location

Are you a BCBA or BCaBA? (Yes/No)

Have you attempted to access this literature on your own through the BACB portal, Google Scholar, or another search engine? (Yes/No)

If you answered yes to the question above, which search engine did you use to access literature?

Please describe your purpose for seeking literature (e.g., for a research project, professional development, and/or support of a clinical case).

Are you searching for a specific article?

If you answered yes to the above question, enter the full name of the article, author(s), journal, and year.

Choose a category of the type of article you are seeking. (Dropdown options: Verbal behavior, functional analysis, assessment of challenging behavior, treatment of challenging behavior, organizational behavior management, skill acquisition procedures, staff training, parent training, research methods, graphing, data collection, other)

If you answered other to the question above, please describe the category of literature.

Choose the population of interest for this literature review (choose all that apply). (Dropdown options: Children (ages birth to 5), Children (ages 6–12), Children (ages 13–17), Young adults (ages 18–29), Adults (ages 30+), Individuals diagnosed with autism, Individuals diagnosed with intellectual disability, Individuals diagnosed with developmental delay, Individuals diagnosed with a specific diagnosis (e.g., fragile X syndrome, cerebral palsy), Other

If you answered other to the above question, please describe the population of interest.

Search Phrases (Enter up to five keywords or phrases and separate with commas. Type terms or phrases that describe information needed for this literature review. For example, tacts, teaching procedures, generalization, echoic prompts, and labeling).

Tell us more about your request. (Please write a few brief sentences regarding your literature review request to assist the individual conducting the literature review.)

Although we used Google Forms, this component could be modified to a simple email system (e.g., create a specific email dedicated to this task such as litrequests@abacompany.com) or a chat tool (e.g., creating a Google Chat room that is comprised of the literature-access team where staff can check in and request an article or group of articles). Our form serves as a prompt for the submitter to ensure they provide the information the literature-access team member would need to complete the search, so if these types of modifications (i.e., use of an email address or chat room) are made, the literature-access team will want to ask the team member any important information they will need to get the article or groups of articles requested. The form may facilitate initial communication between the submitter and the literature team, but smaller organizations with a lower volume of submissions may not need an involved form and could stick to more basic forms of communication.

If an organization wishes to use a webform like ours, we have several suggestions for modifications to increase the utility of the form and streamline the overall process. First, not all questions contained a drop-down menu, but we believe there would be an opportunity to create a drop-down menu for all questions, except the demographic information (e.g., name, phone number, email address). Even questions that involve descriptions (e.g., Question #16 “tell me more about your request. . . .”) could contain standard responses from a drop-down menu to allow the submitter to be more precise but not be required to write if they felt it unnecessary. Our literature-access team appreciated having a free text option so we could more fully understand what the person was seeking, but if the free text option is unhelpful or too laborious to the user, it could be removed or modified to an optional response. Second, our webform did not contain conditional formatting or survey logic. Thus, all submitters completed the entirety of the webform. Several questions were irrelevant to those seeking a specific article. Thus, we recommend creating conditional formatting or survey logic such that the survey skips to the end of the webform once the submitter indicates they need a specific article. If conditional formatting is not possible, provide an option to mark the rest of the form fields as “not applicable.” Third, it is possible organizations could remove Questions #11 (and subsequently #12) about the category of request (e.g., verbal behavior, functional analysis), as our team did not find the information to provide additive value. Many submissions may have covered multiple categories, and we found submitters did not always identify the category of their search in the same way the literature team would categorize it. For example, a person might identify an issue as a skill acquisition need whereas the literature team would identify the same issue as one involving assessment of challenging behavior.

Our organization has always viewed the form as an opportunity to prompt the submitter to engage in specific behaviors (e.g., attempting to search the literature first before submitting a request, thinking through the details of their request), but in doing so the form is likely longer than it needs to be. We have never taken data on the amount of time it takes to complete a form, but anecdotal information gathered from submitters allow us to estimate that it takes anywhere from 5 to 15 min to complete. If creating this form today from scratch, we would likely simplify it to include the submitter’s name, email address, reason for the request (Question #8 above), specific citation of article needed (if applicable) or brief sentence about what is needed in free text (e.g., “I have a client who is engaging toe walking and I have not treated this issue before. I need literature to write a protocol for this”). Thus, one could reasonably reduce a 16-question form to 4 or 5 questions, reducing the response effort for the submitter and likely the literature request team members. If an organization aims to prompt users to engage in specific behaviors or otherwise orient to different resources upon using the form, additional components could be included.

Journal Access

Prior to the BACB’s widely available access to ProQuest for all certificants, we purchased an institutional membership to PsycINFO. This membership allowed us to search and have access to the literature to best respond to requests. Upon the BACB’s access to ProQuest, we did not renew our PsycINFO subscription and utilized the BACB resources accordingly. This component of the system may not need modifications based on an organization’s size and resources. A team member would simply need access to the BACB portal.

The Literature Request System

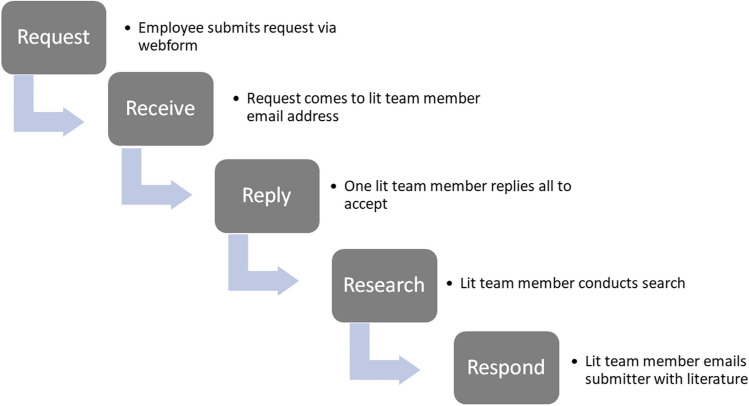

Appendix B Fig. 3 demonstrates the process flow of the literature request system. All staff employed by the organization had access to the literature request form. We placed the link to the form on our organization’s website and frequently reminded staff members of the resource via email and during professional development opportunities. Upon interest in receiving an article or group of articles related to a specific topic, the team member navigated to the organization’s website and clicked on the link titled “literature request form.” The team member completed all sections of the form and clicked “submit.” The response was automatically logged in the system’s responses via a Google Form and an email notification was automatically sent to anyone currently on the literature-access team. The literature-access team reviewed the submission independently and decided who would respond. We did not rotate responsibilities but allowed the literature-access team members to volunteer for topics for which they felt well suited to respond or for which they had special knowledge of the literature. The member of the literature-access team would “reply all” to the literature-access team with a simple acknowledgement that they would handle this request. The member of the literature-access team then searched the literature using keywords from the submission and standard literature search processes. The search process was not standardized, and the member of the literature team was able to search based on their knowledge of the literature, access to information, and preferences for searching the literature. Following the search, the member of the literature-access team independently contacted the team member. The response to the team member included the literature, any other related resources (e.g., offer for case consultation), and a warm acknowledgement for use of the system and for accessing the literature. The goal was to respond to the team member within 7 calendar days and to provide praise for engaging with the system and accessing the literature.

Fig. 3.

Process Flow of the Literature Request System

There are a variety of ways the overall system could be modified based on an organization’s size and resources. Our suggestions for modifying the overall system are also included in Appendix A, along with suggestions for modifying each component described above.

Preliminary Data from our Organization

The data presented below were automatically collected via webform upon submission. For analysis, we exported the data from the webform via CSV file and placed it into a Microsoft Excel document. We created bar graph templates for each area of analysis and the fourth author reviewed the primary data in the Excel spreadsheet and created formulas to capture the total numbers and percentages in the following areas: frequency of submissions per year, percentage of submitters with the BCBA or BCaBA credential, percentage of submitters who attempted to search the literature prior to submitting a request, and the reported purpose of the request. The fourth author then manually checked the formulas to be sure the numbers presented were an accurate reflection of each category.

A separate coder (the first author) reviewed the same spreadsheet created and reviewed by the fourth author. Each formula was reviewed to be sure it captured the total number for each category of responses. The first author also checked to be sure they calculated the same percentage for any data that were converted to a percentage for reporting purposes. The first author confirmed the initial coder was accurate 100% of the time.

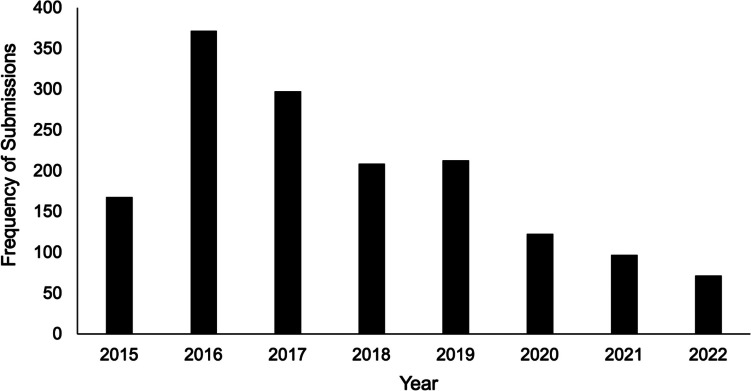

We received a total of 1,552 requests over the course of 7 years. Most submitters (79%) held the BCBA or BCaBA credential, whereas 21% did not. Figure 1 depicts the frequency of submissions per year during the 7-year timespan analyzed (2015-20221). Years are scaled to the x-axis, and frequency of submissions to the y-axis. We received an average of 194 requests per year (range: 72–372). There was a relatively even split between submitters who reported to attempt to search the literature prior to submitting a form (52%) and those who did not (48%).

Fig. 1.

Frequency of submissions per year

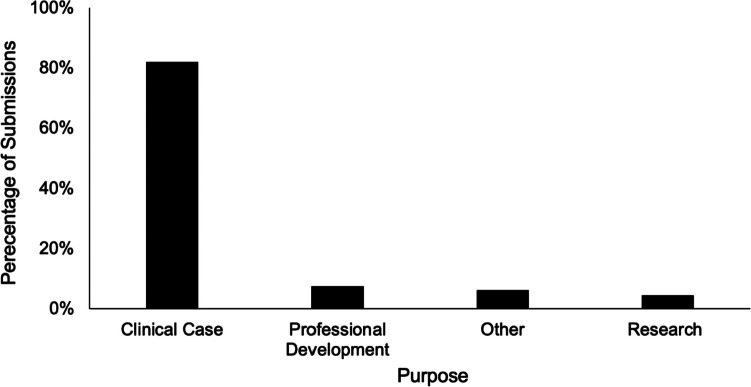

Figure 2 represents the primary reasons individuals submitted a literature request, presented as a percentage of the total submissions for each category. The purpose of the literature review is depicted on the x-axis, and the percentage of submissions is on the y-axis. Most submitters (83%) requested literature for support with a clinical case, 7% submitted a request for professional development, 6% for “other reasons,” and 4% requested literature for research purposes. The stated reasons in the “other” category included supporting parents, supporting insurance/third party requests for information, supervision, academic tasks, blog/presentations, CEU events, or training.

Fig. 2.

Percentage of primary reasons for submitting a request

Discussion and Recommendations

Accessing a discipline’s literature base can encourage a behavior-analytic practitioner to be well-informed of new research, can increase the quality-of-care practitioners provide to their clients, and support ethical practice. However, consistently maintaining contact with the scholarly literature can pose challenges. Organizations who employ practitioners are in a unique position to reduce the response effort associated with accessing the literature through efficient and effective systems that are made easily available to their workforce. In this tutorial, we presented a system, consisting of an electronic search request, a literature search team, and a liaison that was created for a human service agency to reduce many of the barriers associated with practitioners accessing the literature. Seven years of data from our organization were presented, showing that practitioners (primarily those holding the BCBA or BCaBA credential) accessed a liaison to the literature regularly when given the chance to do so and that they primarily accessed the literature for support with their clinical cases.

This tutorial presents the first system with accompanying data demonstrating how to structure a literature request system and the way in which behavior-analytic practitioners engage with the literature when they have access to a system such as this. Although similar systems have been developed to support practitioners on a large scale in other professional areas such as ethics (LeBlanc et al., 2020; Valentino et al., 2023), this is the first organization-wide system in the published literature to demonstrate how to make literature accessible to practitioners geographically spread across the United States.

Slightly over half of submitters identified attempting to access the literature prior to submitting their request. This finding is consistent with the results obtained via survey by Bank et al. (2023), who found that respondents commonly used academic web searches, university library subscriptions, and the BACB research resource to access needed literature and that some (45%) were satisfied with the research resources available to them. Most practitioners may know how to conduct a literature search but could still struggle to find exactly what they are looking for, suggesting a system such as ours can be helpful, even when access is available. For example, practitioners may not know exactly how to narrow their search, choose a clinical method from the literature, or identify clients like their own in the literature where a demonstrated procedure may be of use. Having a system in place where a knowledgeable liaison and team can help narrow down results, send relevant articles, and make recommendations can be valuable, even if access to the literature is widely available. We believe it is valuable for practitioners to attempt a search prior to requesting help, but a system such as this one is still necessary to ensure the literature can be effectively accessed and used in clinical practice. Finally, most submitters needed literature for support with a clinical case. These data suggest that practitioners are actively adhering to their ethical obligation to be knowledgeable of the literature and to use it to guide clinical programming.

It is important to interpret our data and findings against the profile of our organization—one that is primarily a practice organization. Organizations with other goals or priorities (e.g., a dedicated research branch) may have individuals accessing the literature for other reasons (e.g., for the development of a research project, to conduct training). In addition, our data should be interpreted against the size of our organization. Although it is difficult to know the exact data from the years reviewed, our organization has generally grown from approximately 500 clients in four states during the start of the data analysis to 1,600 in seven states during the final year of data analysis. We tend to employee approximately one BCBA or BCBA-D per 12 clients, so the low end of BCBAs was likely around 40 and the high end around 130. These company metrics should be interpreted with extreme caution—as the exact number of clients and certified staff fluctuated due to many variables including staff resignations, newly credentialed staff members, leaves of absence, the pandemic, clinical model shifts and unique payor requirements (e.g., unique staffing models in the state of California, higher staffing ratios for severe behavior programming).

Several barriers to accessing the scholarly literature have been identified by previous researchers (e.g., Briggs & Mitteer, 2022; Carr & Briggs, 2010). These barriers have been identified and solutions offered, yet to our knowledge, no research has demonstrated the implementation of any of these solutions. Our article shows how an organization can overcome many of the barriers related to accessing the literature and reduce the response effort associated with literature access for individual practitioners. We hypothesize that a system such as the one presented here is likely to be of great value to behavior analytic practitioners, as was suggested by Bank et al. (2023). Data such as this may be helpful to organizations wishing to develop the skills of their practitioner workforce. In particular, the type of literature requests can be analyzed, and skills targeted accordingly. For example, many requests we received were related to the assessment and treatment of challenging behavior. Our analysis of these data led us to build standardized resources specific to this topic and supported our decision to hire additional experts to support our practitioners with this clinical population. A system such as ours can also help put practitioners in touch with experts who can support clinical cases and provide training. Particularly as an organization grows, tracking individual practitioner needs can be challenging: a simple system and process such as ours can serve as one cue to the clinical leadership team that a team member needs support with the case and heightened training. Thus, the system can certainly serve solely as a literature access system, but it also may serve to request and provide case consultation and keep practitioners across a multistate organization connected with clinical experts (i.e., the literature request team and clinical leaders).

We have several recommendations for those interested in establishing a literature request system like the one described here. First, identify the team members that will be responsible for completing these requests. Literature requests are often not embedded within a practitioner’s day-to-day activities and responsibilities. Thus, those who volunteer for the literature team may need to dedicate additional time to the task. Second, clearly identify the literature liaison and make their role well-known to the members of the organization (Carr & Briggs, 2010). This liaison will monitor the requests to ensure that all requests are completed in a timely manner and with a high-quality response. The liaison is essential to the success of the literature request system. Third, give considerable thought to the development of the literature request system. Utilize a format that is user friendly and place it in a location that is easy to find. These decisions may be individualized based on the organization’s profile, size, and demographics. Identify how the request system will be structured and the information that you will need from staff members to complete a thorough literature review. Fourth, develop a monitoring system such that requests can be tracked. In the early years of the existing system, the requests primarily came via email, which was convenient for the small team at the time but made it difficult to track and analyze the data later. Fifth, pilot the system before launching it to the entire organization. Open the request system to a few individuals and ensure it functions properly and that you receive the information through the form that will be needed for the literature review. Based on piloting the system, make modifications before going live with all staff members. We also recommend providing the practitioner with information surrounding how the literature request team member successfully identified research on the topic (e.g., provide the keywords and search engine they used and how to access the BACB resources). Finally, we recommend conducting an initial training and ongoing trainings with staff that reviews the importance of the system, how to access the system, and how to use the received information following the request. Be sure that staff members who are new to the organization are made aware of the system and how to use it during their first few weeks of hire.

We also have several recommendations for expanding and improving the system. These are suggestions we have not implemented but that we believe would result in important extensions and the ultimate improvement of an organization’s literature request system. Our literature request system ended when submitters received the literature they requested. We recommend following up with submitters after they receive the information to assess several areas. For example, we do not know how satisfied users were with the system. A quick rating scale or satisfaction survey may help the system creators understand how to adapt it to be more user friendly and to meet the changing needs of a practitioner work force. There is also an opportunity to collect data on the impact of the system, in particular changes that occur from accessing the literature and any influence on client outcomes. Follow-up could include debriefing with recipients (e.g., a quick phone call with structured questions or a simple web-based form) on how they used the articles. If an organization has an objective outcomes database, data from client outcomes could be compared against frequency of use of the literature request system to determine how the latter influenced the former. Having the data on outcomes and the frequency of submissions to the literature system for clients would provide both data points needed to conduct such an analysis. As an organization and the literature team grows, we recommend standardizing the communication response to help streamline the process and ensure users of the system receive consistent responses. We did not keep a running list or database of the articles requested by or delivered to recipients. We suspect we could decrease barriers to research access, consumption, and integration by having article banks relevant to certain topics that any team member could access. Although each of the literature liaisons kept their own system over the years, it was never organized or placed into a central location for others to access. The liaison in our organization would often share articles with the rest of the literature team via a shared drive, but this was not done in any structured way. A repository of all delivered articles that future employees could peruse before requesting would be a wonderful extension of the literature-access system. In the data we analyzed, it was uncommon to see multiple requests for the same article(s); however, we observed frequent requests on similar categories. The most frequent requests were in the following categories: functional analysis, assessment of challenging behavior, treatment of challenging behavior, and skill-acquisition procedures. We envision a repository including one area where individual articles could be accessed that are organized by title, authorship, and year. Then, a second area could include larger categories such as these (e.g., assessment of challenging behavior), with subcategories (e.g., trial-based functional analyses) for easy access to a topic of interest.

Finally, searching, accessing, and contacting the literature ideally becomes a part of the treatment planning process for practitioners. Training an organization’s workforce to conduct literature searches may facilitate independence with this task and reduce the need for a system such as ours. However, even when practitioners are adequately trained to effectively search the literature, they may still have competing contingencies, need consultation around how an intervention fits into their treatment plan or applies to their client and they may need general clinical support. If practitioners are adequately trained to search the literature and do so regularly, a system such as ours could still serve as a resource for them (e.g., if someone finds an article but struggles to adapt the protocol to their client and the team provides this type of support).

Although it can seem laborious to maintain contact with the scholarly literature and use it in practice, systems such as the one described here can reduce the efforts associated with this important professional guideline. Reducing the response effort involved in access and creating a culture wherein it is common to read an article, incorporate it into practice, and go to the literature when you need answers can create a community of knowledgeable practitioners who remain connected to the science and who follow best clinical practices by doing so.

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix C

Sample Deidentified Literature Request

Full Name

Team member

teammember@work.com

Phone Number

123-456-7890

Work Location

Literature Seeking, MA

Are you a BCBA or BCaBA?

Yes

Have you attempted to access this literature on your own through the BACB portal, Google Scholar, or another search engine?

No

If you answered yes to the question above, which search engine did you use to access literature?

N/A

Please describe your purpose for seeking literature (e.g., for a research project, personal interest, and/or support of a clinical case).

Support on a clinical case

Are you searching for a specific article?

No

If you answered yes to the above question, enter the full name of the article, author(s), journal, and year.

N/A

Choose a category of the type of article you are seeking.

Skill acquisition procedures

Parent Training

If you answered other to the question above, please describe the category of literature.

N/A

Choose the population of interest for this literature review (choose all that apply).

Children (ages 6–12)

Individuals diagnosed with autism

If you answered other to the above question, please describe the population of interest.

N/A

Search Phrases (Enter up to 5 keywords or phrases and separate with commas. Type terms or phrases that describe information needed for this literature review. For example, tacts, teaching procedures, generalization, echoic prompts, and labeling).

Desensitization, tolerating hair brushing, tolerating grooming

Tell us more about your request (Please write a few brief sentences regarding your literature review request to assist the individual conducting the literature review).

I am on a case of a client of an older client with autism and some medical difficulties. She has difficulties with parents during shower time and when they are brushing her hair specifically. I want to become familiar with the literature because I would like to write a desensitization program or another way to help her brush her hair independently but would like some research and/or materials backing these kinds of programs as I have never written one before.

Funding

No funding was associated with the current study.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest regarding this article.

Ethical Approval

All procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional review committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments.

Footnotes

The literature review system was launched in 2012; however, for the first 3 years, the form did not make it such that all data were captured and able to be analyzed. Therefore, data analysis began in 2015 upon the switch to a different type of form.

We thank Linda LeBlanc for her vision supporting access to literature at Trumpet Behavioral Health and execution of the early phases of the system.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Bank NL, Ingvarsson ET, Landon TJ. Evaluating professional behavior analysts’ literature searches. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2023;16:284–295. doi: 10.1007/s40617-022-00720-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2020). Ethics code for behavior analysts. https://bacb.com/wp-content/ethicscode-for-behavior-analysts/. Accessed 31 July 2023

- Briggs AM, Mitteer DR. Updated strategies for making regular contact with the scholarly literature. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2022;15:541–552. doi: 10.1007/s40617-021-00590-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr JE, Briggs AM. Strategies for making regular contact with the scholarly literature. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2010;3:13–18. doi: 10.1007/bf03391760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon MR, Reed DD, Smith T, Belisle J, Jackson RE. Research rankings of behavior analytic graduate training programs and their faculty. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2015;8:7–15. doi: 10.1007/s40617-015-0057-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillis JM, Carr JE. Keeping current with the applied behavior-analytic literature in developmental disabilities: Noteworthy articles for the practicing behavior analyst. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2014;7:10–14. doi: 10.1007/s40617-014-0002-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow LM. Can a journal club bridge the gap between research and practice? Nurse Educator. 2004;29(3):107–110. doi: 10.1097/00006223-200405000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinicke MR, Carr JE, Pence ST, Zias DR, Valentino AL, Falligant JM. Assessing the efficacy of pictorial preference assessments for children with developmental disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2016;49(4):848–868. doi: 10.1002/jaba.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc LA, Onofrio OM, Valentino AL, Sleeper JD. Promoting ethical discussions and decision making in a human service agency. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2020;13:905–913. doi: 10.1007/s40617-020-00454-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons MB, Reid DH. Reading groups: A practical means of enhancing professional knowledge among human service practitioners. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2011;4:53–60. doi: 10.1007/BF03391784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers TP, Valentino AL, Landon TJ, Aiello S. Board certified behavior analysts’ supervisory practices of trainees: Survey results and recommendations. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2019;12:536–546. doi: 10.1007/s40617-019-00367-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slowiak JM, DeLongchamp AC. Self-care strategies and job-crafting practices among behavior analysts: Do they predict perceptions of work–life balance, work engagement, and burnout? Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2022;15:414–432. doi: 10.1007/s40617-021-00570-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentino AL, LeBlanc LA, Raetz PB. Evaluation of stimulus intensity fading on reduction of rapid eating in a child with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2018;51(1):177–182. doi: 10.1002/jaba.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentino, A. L., & Juanico, J. F. (2020). Overcoming barriers to applied research: A guide for practitioners. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 13, 894–904. 10.1007/s40617-020-00479-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Valentino, A. L., Gayle, R. I., George, A. J., & Fuhrman, A. M. (2023). Promoting ethical discussions and decision making in a human services agency: Updates to LeBlanc et al.’s (2020) ethics network. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 10.1007/s40617-023-00785-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Veazey SE, Valentino AL, Low AI, McElroy AR, LeBlanc LA. Teaching feminine hygiene skills to young females with autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2016;9(2):184–189. doi: 10.1007/s40617-015-0065-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wine B, Osborne MR, Newcomb ET. On turnover in human services. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2020;13:492–501. doi: 10.1007/s40617-019-00399-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.