Abstract

For over a decade, behavior analysts have been calling for more culturally responsive practices. Within the newest edition of the Ethics Code for Behavior Analysts, one addition in particular was Standard 1.07 Cultural Responsiveness and Diversity (Behavior Analyst Certification Board, 2020b). The inclusion of this new standard shows positive movement but there is more to unpack. This article seeks to contextualize the relevance and necessity of Standard 1.07 both at a societal level and within the field of applied behavior analysis (ABA). A timeline of previous calls to actions and changes within ABA that align with the inclusion of this standard is discussed along with the obstacles that hindered progress. Lastly, directions are provided for how to make behavior analytic practices more culturally responsive through confronting our personal biases, using culturally responsive pedagogies, updating and adapting our practices regarding the selection of target skills and assessment administration, and collaborating with our clients and their teams. Through an understanding of its urgency and direct applications into our work, this article seeks to aid behavior analysts in shifting our practices to being more culturally responsive.

Keywords: Ethics, Cultural responsiveness, Diversity, Cultural competency, Application

Behavior analysts must engage in ethical behavior for the sake of clients and society. The Behavior Analyst Certification Board (BACB) provides the Ethics Code for Behavior Analysts (2020b; hereafter referred to as the Code) to guide professional practice and allow for the evaluation of ethical behavior. The Code explicitly outlines the ethical standards to which behavior analysts must adhere when credentialed as or studying to obtain the credential of a board certified behavior analyst (BCBA) or board certified assistant behavior analyst (BCaBA; hereafter referred to as behavior analysts; BACB, ). Behavior analysts are responsible for knowing and adhering to the Code in all professional behavior analytic activities (e.g., direct service delivery, consultation, supervision, training, research).

On January 1, 2022, the newest edition of the Code when into effect (BACB, 2020b). Several changes and additions were made to the new 2022 Code, including the addition of Standard 1.07: Cultural Responsiveness and Diversity. This standard states,

Behavior analysts actively engage in professional development activities to acquire knowledge and skills related to cultural responsiveness and diversity. They evaluate their own biases and ability to address the needs of individuals with diverse needs/ backgrounds (e.g., age, disability, ethnicity, gender expression/identity, immigration status, marital/relationship status, national origin, race, religion, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status). Behavior analysts also evaluate biases of their supervisees and trainees, as well as their supervisees’ and trainees’ ability to address the needs of individuals with diverse needs/backgrounds. (BACB, 2020b, p. 9)

To support behavior analysts’ responsiveness to Standard 1.07, we have written this article to not only describe the importance of the addition of Standard 1.07: Cultural Responsiveness and Diversity to the 2022 Code (BACB, 2020b) but also to provide explicit actions that behavior analysts can take to ensure they adhere to Standard 1.07 when working with clients. Although Standard 1.07 addresses several areas of diversity, we focus on how Standard 1.07 applies to racially, ethnically, and religiously marginalized populations. First, we review the relevance and necessity of Standard 1.07, including a discussion of background information at the societal level, and also within the field of applied behavior analysis (ABA). Next, we provide a brief overview of previous calls to action and changes within ABA that align with the inclusion of this standard. After providing this foreground for Standard 1.07, we detail avenues for bridging recommendations for culturally responsive practices into clear actionable steps. Finally, we end with recommendations for future research and practice.

What it Really Means: The Context of Cultural Responsiveness and Diversity

The concept of what encompasses a person’s culture is extensive. Several factors can be considered a part of an individual’s cultural identity, including age, disability, ethnicity, gender expression/identity, immigration status, marital/relationship status, national origin, race, religion, sexual orientation, and socioeconomic status. Given the various aspects of an individual’s cultural identity, movements for culturally responsive practice began with a call for practitioners (e.g., behavior analysts) to be culturally competent. Cultural competence is a practitioner’s ability to develop an awareness of their own cultural beliefs, values, and biases while also acquiring knowledge of the norms and behaviors of other cultures and displaying professional skills that combine awareness and knowledge of different cultures to provide culturally responsive practices (Danso, 2018; Mlcek, 2014; Sousa & Almeida, 2016). More recent criticisms have argued that the concept of culture is individually and socially constructed and is continually changing, making cultural competency an unobtainable goal that practitioners should continuously strive to achieve (Dean, 2001).

In working to achieve cultural competence, a practitioner creates a more culturally responsive environment because the client is treated as the “expert” and the practitioner continuously seeks knowledge and tries to understand the client within the client’s cultural identity (Dean, 2001). Thus, to create a culturally responsive environment, the behavior analyst uses their ever-evolving cultural competence to create and support an atmosphere that acknowledges and addresses multicultural issues, validates practices, and promotes culturally valid decision making (Garrett et al., 2001; Vincent et al., 2011).

To begin working toward cultural competence and creating culturally responsive environments, behavior analysts must first understand and recognize the society in which our field is situated. The United States was founded by one group of people using another to build an economy (Baptist, 2016; Stone, 1971). As a result, inequity in the United States is synonymous with its dominant (White) culture (Horner-Johnson, 2021; Jensen, 2012; Lemke, 2016; Swidler, 1992). As the United States has developed, the large systemic issues of inequity have been woven into the fabric of the country’s blueprint. As a result, there are disparities among race, gender, disability status, and socioeconomic class in every aspect of industry, government, and education. Through unequal and inequitable access to services such as transportation, health care, the internet, employment opportunities, and education, inequity is ingrained into the “character and quality of life for most Americans” (Noguera, 2017, p. 130).

Black and Indigenous people of color (BIPOC) and disabled1 people experience the highest rates of health and educational inequities in today’s society (Planty et al., 2008, World Health Organization, 2017). As racial inequalities are experienced across and within disabled populations, the intersectional experiences of disabled people who are also racially or ethnically minoritized are even more important to recognize and understand in order to provide culturally responsive practices (Horner-Johnson, 2021).

Intersectional Identities

Intersectionality is the way an individual’s multiple cultural identities come together and are each uniquely affected by society (Boveda & Aronson, 2019). When discussing matters of social justice, it would be a disservice to consider one aspect of a person’s cultural identity (e.g., disability) without considering other aspects of their cultural identity (e.g., race). Rather than separating these identities, it is the intersection of these identities that holds their distinct and unique experiences and shapes their individualized cultural identity (McCall et al., 2014). Thus, recognizing the intersectionality of cultural identities and understanding that no individual identity exists in isolation will better inform the development and delivery of culturally responsive practices (Crenshaw, 1989).

Behavior analysts serve clients with fluid and usually oppressed intersectional identities. For example, over 80% of behavior analysts report their primary area of professional emphasis to be related to disabled populations, including autism (72.2%), education (6.92%), and intellectual and developmental disabilities (2.76%; BACB, n.d.; unfortunately, the BACB does not report the demographic data of clients receiving ABA services). Developing intersectional competence—the understanding of how individuals with multiple cultural identities each are uniquely affected by society (Boveda & Aronson, 2019)—supports the provision of culturally responsive practices by providing behavior analysts with a better understanding of their clients’ unique experiences.

Dis/ability Critical Race Studies (DisCrit) provides a useful framework to help behavior analysts understand the intersectionality of an individual’s disability identity and their other identities (e.g., race). DisCrit combines Critical Race Theory and Disability Studies to analyze these interdependent constructs within the United States and the compounding impact of these multiply minoritized identities (Annamma et al., 2013). Although an in-depth review of DisCrit is beyond the scope of this article, its inclusion within ABA teachings could provide numerous benefits to our field and could help inform the development of culturally responsive behavior analytic practices.

An example that highlights the importance of taking our clients’ intersecting identities into consideration is when teaching interactions with police. Safety skills such as being able to call the police and answer basic identification questions by police officers can be lifesaving. Although these skills may be important, the lives of our clients would be put at risk if these safety skills were taught without considering the intersection of disability and individual’s other identities. The risk of being subjected to police violence significantly increases as disability intersects with race, class, gender, and LGBTQ+ status (Mueller et al., 2019). In recent years, the extent of excessive force usage and killings by police disproportionality against the BIPOC community has become more publicly known, whereas the addition of disability has remained outside of the mainstream media reporting (Perry & Carter-Long, 2016). Data estimates that disabled people account for 30%–50% of excessive force usage by police, and 33%–50% of people killed by police are disabled (Perry & Carter-Long, 2016). Given these realities, when determining if a police safety skill program would be beneficial or when creating a police safety skills program, the behavior analyst should be aware of and considering intersecting identities such as race + disability status.

How We Got Here: Progress within the Field

Although the inclusion of Standard 1.07 is new to the 2022 Code, the idea of culturally responsive behavior analytic practice is not necessarily novel. Whereas the previous ethics code, Professional and Ethical Compliance Code for Behavior Analysts (hereafter Compliance Code; BACB, 2014), did not contain explicit discussion or requirements related to culturally responsive practices and/or intersectional identities, some could argue that Standard 1.05: Professional and Scientific Relationships loosely addressed this need. Under subsection C, the Compliance Code detailed that behavior analysts should seek out training, consultation, and/or supervision if a difference in age, gender, race, culture, ethnicity, national origin, religion, sexual orientation, disability, language, or socioeconomic status significantly affect the behavior analyst’s work (BACB, 2014, p. 5). Thus, although it was not explicitly stated, some behavior analysts may have interpreted this code to indicate that they should be well-informed about their clients’ intersectional identities and about the different cultures they may or may not share.

Beyond the guidance provided by the BACB Codes, many behavior analysts have published articles regarding the importance of more explicitly bringing culturally responsive practices and concepts into the field. Several behavior analysts have suggested ideas, such as developing training and curriculum surrounding culture and diversity, increasing opportunities for mentoring, and increasing and supporting minority practitioners (Beaulieu et al., 2019, Conners et al., 2019, Fong et al., 2016, Gatzunis et al., 2022, Ortiz et al., 2023). Fong and Tanaka (2013) highlighted that although the 2014 Compliance Code included Standard 1.02: Competency, the Standard did not address the importance of cultural competence, or the ability to competently work with individuals from different cultures. Thus, these authors offered operational definitions for culture, competence, and cultural competence and proposed recommendations for new standards for cultural competence within the field of ABA (Fong & Tanaka, 2013).

Wright (2019) used the field of social work’s cultural humility framework to suggest adaptations to behavior analytic practices. Wright argued that the term “cultural humility” is a more appropriate term to represent the individual and institutional accountability that should exist within the field. Wright also discussed ways practitioners could use self-management, a common method used in ABA, to address disparities and improve outcomes through self-reflection. Lastly, in response to the increased visibility of the impact of racism ignited by the deaths of numerous Black people like George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Elijah McClain by police and domestic terrorists, the journal Behavior Analysis in Practice issued an emergency publication series titled Police Brutality and Systemic Racism, edited by Denisha Gingles and Jomella Watson-Thompson.

Obstacles

Although many behavior analysts have made valiant efforts to improve cultural competence within the field, these efforts have not gone without barriers and challenges. The 2022 Code now includes a specific standard related to cultural responsiveness (BACB, 2020b); however, calls for a more explicit inclusion of standards related to cultural competence had been made for years prior to the new Code, without any changes from the BACB. Further, even with the numerous articles, groups, and movements that have been created by behavior analysts in pursuit of more culturally responsive practices, there is still little training provided in behavior analytic education programs or to behavior analysts in the field (Beaulieu et al., 2019; Uher et al., 2023). In 2019, behavior analysts were surveyed to determine whether they viewed cultural competency training as important and how much of their training included working with people from diverse backgrounds (Beaulieu et al., 2019). The authors found that although respondents indicated they felt being trained to work with marginalized clients is extremely important, the majority of respondents reported receiving little to no training in this area. Expanding on this finding, a recent systematic review was conducted to identify common practices for training cultural competency within the social service professions. This review revealed that no training programs for behavior analysts have been published in the peer reviewed literature to date (Uher et al., 2023).

Finally, recent actions by the BACB indicate that the field still has significant progress to make. For example, after a failure to issue a statement in response to George Floyd’s murder on May 25, 2020, a petition on change.org entitled “Call for the BACB to denounce racial injustice” was created and garnered 4,024 signatures (Kelly, 2020). On June 4, 2020, the BACB released a statement on Facebook (BACB, 2020a; see Figure 1). The BACB’s statement generated several comments criticizing the fact that the BACB stated they “cannot speak for or represent our discipline as a whole” and many commenters deemed the post as an empty gesture that demonstrated a lack of accountability when it comes to topics of racial injustice. Respondents also expressed their frustrations with both the delay in making any type of public statement (10 days after George Floyd’s murder) and how the post did not make any attempt to address actionable change.

Fig. 1.

BACB Statement in Response to the Death of George Floyd. Note: This figure is a screenshot of a status update posted by the official Facebook page BACB—Behavior Analyst Certification Board on Facebook on June 4, 2020.

Thus, in response to the BACB’s public Facebook statement, a second petition on change.org entitled “Cultural Competency Training Requirements for Behavior Analysts” was made on June 9, 2020 (Beaulieu, 2020). This petition received 3,072 signatures echoing the comments on the public Facebook statement and calling for the BACB to implement two changes. The first suggested change was for the BACB to convene a diverse task force to develop and adopt guidelines for working with individuals from marginalized, minoritized, and/or oppressed backgrounds and to add cultural competence task list items in future versions of the Task List as well as continuing education requirements. To date, no such task force has been convened. It should be noted, however, that the Association for Behavior Analysis International’s existing Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Board has added content (eight tasks across four domains) into the BACB Test Content Outline, a guide for the BACB certification exam (BACB, 2022).

The second suggested change was for the BACB to release the demographic data of all certificants who have self-reported data. On September 8, 2020, the BACB released the available demographic data available for its members (BACB, n.d.). Nine days later, however, the Latino Association for Behavior Analysts (2020) called attention to how many behavior analysts were not represented within these data: only 53.5% of BCBA/BCBA-D, 54.2% of BCaBA, and 30.3% of registered behavior technicians had input their demographic data into the BACB’s database.

Behavior Analysts’ Call for Evolution

Given the obstacles to cultural responsivity still experienced by behavior analysts and the continued lack of inclusion of culturally competent training and ethical standards within the field, we echo that it is time for a behavior analytic evolution (Miller et al., 2019). All behavior analysts can and should shift their practices to be culturally responsive in ways that best meet the individual needs of all clients. To do this, Miller et al. (2019) highlights that the field of behavior analysis must evolve at both the individual practice level and at organizational levels. They stress that such an evolution will require a critical examination of how behavior analytic services affect both the direct consumers of services and society.

The field needs to evolve from the current practice of allowing the “dominant group” to design the goals and procedures for consumers, to a new interactional approach in which the consumer’s perspectives and cultural identities are acknowledged and considered as a part of program development (Miller et al., 2019). When behavior analysts recognize the intersection of their client’s cultural identities, they are better able to consider the impact and influence of these identities when making intervention selection decisions (DeFelice & Diller, 2019).

Behavior analysts should also evolve to focus on equity in service provision, rather than focusing on equality (U.S. Department of Education, 2013). Although the terms “equality” and “equity” sound very similar, the distinction between the two produces highly different decisions. A situation has equality when everyone, regardless of individual needs, receives the same tools to complete a task—everyone is treated the same, but in the end not everyone may be able to complete the task because the tool might not be appropriate for some people. An example that directly relates to behavior analytic practices is the considerations when recommending the number of ABA service hours a client should receive. When a recommendation for the number of services hours is made, that recommendation is determined by factoring in the client’s individual needs and goals (i.e., based on equity). If the number of service hours were determined based on equality, then all clients would receive a recommendation for the same amount of service hours. Equity in service-hour recommendations focuses on the specific number of hours each individual would benefit from rather than focusing on giving the same number of service hours to every client. Equality is distinguished by the process whereas the equity is distinguished by the end product. Likewise, it is ableist to view two autistic people as interchangeable on the basis of their diagnosis. In other words, a behavior analyst selecting and implementing an intervention with an autistic client because that intervention was effective for another autistic client implies that the behavior analyst sees these two people as interchangeable.

It is important to note that it is the job of all behavior analysts to lead this evolution. Culturally responsive practices highlight the need to elevate the voices of marginalized people, but it is not the job of marginalized people to be responsible for change. As of 2022, over half (53.66%) of all practicing behavior analysts are White and this number increases to 70.5% for BCBAs (BACB, n.d.). Given that the majority of behavior analysts who provide training and supervision to future behavior analysts are White, these behavior analysts will need the skills to be culturally responsive to both clients and staff who do not share their racial identity. It is not the burden of behavior analysts from marginalized backgrounds to take the lead in pushing the field toward cultural competency. Although marginalized behavior analysts will have many insights and contributions, the concept of having those who are oppressed responsible for the education of others removes the focus from the individual responsibilities’ practitioners have to develop their own competencies. We are all responsible for the betterment of our field and every behavior analyst should be putting in the personal work (Machalicek et al., 2022). These data also indicate there is a critical need to diversify the field, both for the marginalized clients who are being served and for those who are studying to become behavior analysts.

Where We Go from Here: Actionable Items to Bring Standard 1.07 into Practice

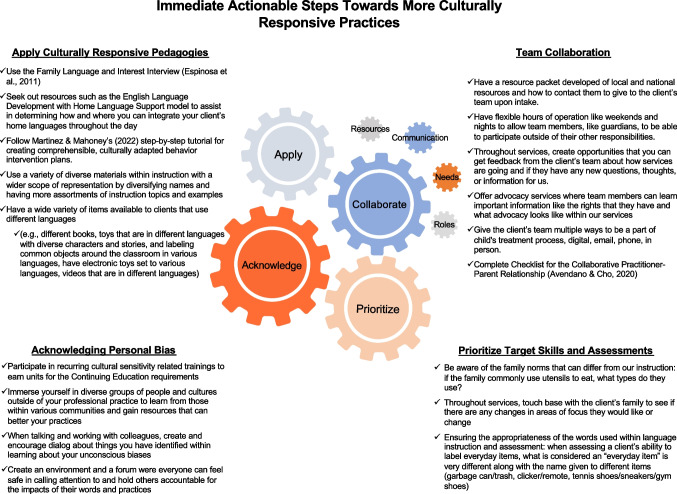

To begin the behavior analytic evolution, we now present four areas within the practice of ABA where changes can be made to better serve consumers in a culturally responsive way, including (1) acknowledging our personal biases; (2) applying of culturally responsive pedagogies; (3) prioritizing skills and assessments; and (4) collaborating with our client and their team. Figure 2 serves as a resource that breaks down these four areas and provides immediate action items that behavior analysts can take to improve their services.

Fig. 2.

Four categories of actionable steps behavior analysts can incorporate into their work for more culturally responsive practices within ABA

Acknowledging Personal Bias

An individual cannot be culturally responsive without acknowledging their personal biases. In fact, such an acknowledgement is also a new standard within the 2022 Code: Standard 1.10: Awareness of Personal Biases and Challenges (BACB, 2020b). Everyone, regardless of whether they are a member of a dominant or oppressed group, has personal biases. Within a racial context, bias can also be thought of as a prejudice (Matsuda et al., 2020). Bias can slip into our work when we do not actively and critically reflect on our thoughts and behaviors. When we critically reflect on the assumptions that we make, we can begin to recognize “one set of contingencies may lead to a specific set of behaviors that may be reinforced or viewed as acceptable in one culture, though the same set of behaviors may be punished or viewed unfavorable by another culture” (Conners & Capell, 2020, p. 7). Thus, all individuals should acknowledge and address their biases, regardless of their social positioning.

To acknowledge biases, the behavior analyst must first identify their personal biases. As there is no singular tool for assessing personal biases, Table 1 first provides a variety of assessments that can be used to help behavior analysts identify complementary and competing contingencies between their own identities and others’. Table 1 also provides a list of educational modules that behavior analysts can use to learn about personal biases and how to be more proactive about identifying the influences their personal biases have in their practices. When personal biases are identified and acknowledged, then behavior analysts are able to better situate their clients within their own intervention goals (Conners & Capell, 2020). As the process of assessing personal biases is not a one-time learning opportunity, these self-assessments and modules can be used as continuous self-reflection and to identify areas for continuous improvement.

Table 1.

Tools to use for understanding and learning about personal biases

| Type | Name | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment | Unconscious Bias: An Educator’s Self-Assessment | This self-assessment will help you discover areas where you may hold an unconscious bias, guide you in exploring your own personal narrative, or story, that may have informed your bias, learn how to disarm your bias by looking for more than one way to interpret a situation or interaction, use the power of books to gain exposure and insight into the lives, experiences, and stories of those against whom you may hold a bias. | Maryland State Education |

| Personal Self-Assessment of Anti-Bias Behavior | A checklist for assessing individual attitudes and behaviors for bias. Provides an area to chart out goals and areas of growth after taking the assessment. | Anti-Defamation League | |

| Implicit Association Test | Measures the strength of associations between concepts and evaluations or stereotypes to reveal an individual’s hidden or subconscious biases. | Project Implicit | |

| Educational Content | Implicit Bias Module Series | This module series covers implicit bias. Module 1: Understanding Implicit Bias covers the basics of implicit bias including what it is, the origins of bias, and implicit bias in action. Module 2: Real-World Implications discusses the identifiable role and impact of implicit bias in various institutes. Module 3 and Module 4 address how to test for implicit bias with Implicit Association Tests and how to understand and move forward after receiving results. | Kirwan Institute for The Study of Race and Ethnicity |

| ADDRESSING Model | A framework that facilitates recognition and understanding of the complexities of individual identity. There are considerations of age, developmental disabilities, acquired disabilities, religion, ethnicity, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, indigenous group membership, nationality, and gender contributes to a complete understanding of cultural identity. | Hays (2001) |

When behavior analysts reflect on their own unique positionalities and culture, they are better able to label their own perspective and identify that how the experiences they have had and the lenses they use to see the world are not the same for others. If behavior analysts do not reflect on their behaviors and thoughts, they risk confusing their personal beliefs and values with their duty to clients (Rogerson et al., 2022). Within their personal reflections, they can acknowledge these differences so that the active work of checking their own biases and assumptions can begin (McGill et al., 2021). Proactively checking biases and assumptions when entering into new partnerships with clients will create an atmosphere for collaboration. The addition of acknowledging and addressing personal biases can significantly affect interactions. Additional actionable steps that behavior analysts can take to unpack their personal biases can be found in Figure 2.

Applying Culturally Responsive Pedagogies

ABA services are meant to ensure each client receives individually tailored interventions that best suit their needs (Cooper et al., 2020). To ensure these services also address the complexities and nuances of clients’ intersectional identities, behavior analysts should use culturally responsive practices (Johnson et al., 2006; Vincent et al., 2011). Culturally responsive practices are not “a pre-determined curriculum, a specific set of strategies, a watering down of the curriculum, a ‘feel-good’ approach, or only for [clients] of particular backgrounds” (Nieto, 2016, p. 1). Rather, cultural responsiveness is a mentality that both respects and honors each clients’ uniqueness along with their cultural experiences and histories (Nieto, 2016). Culturally responsive practices ensure that individuals with intersectional identities are provided the support they need to be successful. Culturally responsive practices also provide opportunities for social, political, religious, socioeconomic, and racial norms to guide best-practices for each person as well as knowledge regarding how one’s identity shapes and influences their learning (Nieto, 2016).

To improve culturally responsive practices in ABA, Mathur and Rodriguez (2022) created a cultural responsiveness curriculum for behavior analysts that includes seven domains in which target behaviors, learning context, outcomes, and evidence of generalization are listed. In addition to the curriculum, Mathur and Rodriguez (2022) also created a detailed competency checklist of a comprehensive cultural responsiveness curriculum for behavior analysts. This curriculum demonstrates that culturally responsive practices should be implemented and governed at the organizational level, rather than focusing on individual behavior analysts, and the authors call on behavior analysts and educational programs and organizations to do so.

The goal of culturally responsive teaching should include, at minimum: (1) family involvement; (2) bringing home language into the learning environment; and (3) understanding history and culture and community culture within the classroom (Ferlazzo, 2020). First, cultural responsiveness involves collaboration with clients and their families. Collaborating with families will help behavior analysts learn how to best tailor their services for their client and allow for an open discussion of the client and/or their guardian(s) preferences for instruction (Mathur & Rodriguez, 2022). For example, although it may not be possible for instruction to be exclusively provided in a client’s home language, there are many ways in which it can still be incorporated throughout instruction. Planning for how language is to be emphasized and how their language can be used throughout the day should be a collaborative process. One method is to use the English Language Development with Home Language Support Model (Oliva-Olson et al., 2019), which was designed for teachers who are not proficient in their clients’ home language. At the organizational level, agency owners and administrators can arrange for their entire staff to be trained in this model. Whereas instruction is primarily provided in English, this module helps identify how language and multicultural supports can be interwoven in day-to-day activities (Oliva-Olson et al., 2019). As every aspect of behavior analytic practices should be considered when behavior analysts are striving to be culturally responsive, the ways in which practices can be updated are endless. As a step in the right direction, Figure 2 lists specific actionable examples behavior analysts can take to make their practices more culturally responsive.

Prioritizing Target Skills and Assessment of Skills

Even though individualized intervention is a cornerstone of ABA practices, the inclusion of cultural considerations within both the selection of target skills and assessment implementation can create an even more individualized experience. Although it is anticipated that behavior analytic oriented resources will emerge in the coming years, Figure 2 provides a brief list of considerations and actions behavior analysts can take to better incorporate cultural responsivity into prioritizing target skills and using assessments.

Target Skills

When creating intervention goals for clients, behavior analysts first ask what skills are going to be helpful to the client? Behavior analysts need to understand and recognize that they are not the sole person deciding what is best for their clients. In fact, the role of the behavior analyst is to support and help guide the client identify goals and skills that are important to them. Thus, to answer this initial question, behavior analysts should work first and foremost with the client to determine their goals and interests and should then collaborate with the caregivers to develop a further informed understanding of what is important to the family at any given time. Obtaining family input can be essential when determining which skills to prioritize and how to assess and interpret the results (Jimenez‐Gomez & Beaulieu, 2022). For example, whereas some guardians may want to focus on skills such as communication or social skills, others may prefer to focus on less often emphasized skills, such as identifying family members, safety skills, or cleaning their room and other chores to help around the house (Jimenez‐Gomez & Beaulieu, 2022). Prioritizing goals identified through collaboration will help to reassure clients and guardians that their input and their thoughts, experiences, and opinions are both wanted and essential in the creation and continuation of intervention plans. Behavior analysts can also work with clients and families to prioritize educational goals while also considering the various objectives and goals that are required by the school, state, and national education departments.

Assessments

In addition to writing intervention plans, behavior analysts also conduct assessments to identify skills to target. Jimenez-Gomez and Beaulieu (2022) identified that research on behavioral assessments that specifically incorporate cultural variables is limited. Most assessments that are used in ABA were developed with the assumption that all clients have the same general goals and priorities (i.e., Western, able-bodied, neurotypical goals and priorities; Leaf et al., 2022). The sequence in which items on an assessment are arranged communicate a universal developmental projection with the assumption that everyone develops the same skills around the same time and in the same sequence. This assumption of a universal developmental sequence regards any deviation from this sequence as a deficit or problem and fails to consider the individual or the individual’s culture as an important developmental variable. For example, crawling is often considered a prerequisite for walking on these assessments. If a behavior analyst has a client who is not walking, they might choose to first teach crawling skills; this approach might not take the child’s culture into consideration because in certain cultures it is not considered appropriate to encourage or teach an infant to crawl. For instance, in Jamaica, the developmental sequence does not emphasize crawling because it is seen as unsanitary for the child to be moving around on the floor (Adolph et al., 2010). As another example, behavior analysts should consider the language most often used in the home when they are assessing language (Jimenez-Gomez & Beaulieu, 2022). Clients living in a multilingual household may be able to identify everyday items in their native language, but not in English. Thus, if an assessment only asks the client to identify items in English, the results could be interpreted as a deficit skill in item identification and an intervention plan could be developed and implemented to address an unnecessary target skill. The question of skill appropriateness for the client and their cultural identity needs to be addressed before teaching begins.

Collaborating with the Client, Guardians, and the Client’s Team

The 2022 Code includes Standard 2.09: Involving Clients and Stakeholders (BACB, 2020b), which emphasizes the client’s involvement in their intervention planning. Standard 2.09 also provides a new definition for the term “stakeholders”2 as those who are not the client but are affected by and invested in the client’s services, including parents, caregivers, relatives, legally authorized representatives, collaborators, employers, agency or institutional representatives, licensure boards, and funder, third-party contractors for services (BACB, 2020b). For intervention to have the greatest impact, team collaboration and communication are key; however, the low quantity and quality of communication between behavior analysts and team members has been a frequent concern (Helton & Alber-Morgan, 2018). To empower team members and help position them to best advocate when the client is in their care, it is the behavior analyst’s job to create the best atmosphere for team collaboration. Because collaborating with teams is a multifaceted task, Figure 2 provides a brief list of actionable items within four essential components that behavior analysts can take to improve collaboration.

Communicating their Essential Role to the Client’s Team

From the onset of services, behavior analysts should help the client’s team understand their role and how they can help shape intervention plans. The behavior analyst should clearly communicate and thoroughly explain the team’s essential role in the development and delivery of the individual’s intervention plan. Clearly communicated roles and expectations creates opportunities for individuals like guardians to advocate for their child’s needs and wants as well as input on the services that are provided from behavior analysts. To support team collaboration, behavior analysts can provide documents that describe the role of the behavior analyst and how the services that are provided can be designed to meet their goals. Having extensive outlets for behavior analysts to understand each team’s ecosystem creates pathways for open communication and understanding while also ensuring they know their partnership is encouraged.

Understanding Each Team’s Needs and Goals

Another way to build effective collaboration is to have direct conversations about the Team’s needs and goals for the services. All discussions with the team should include the client to the greatest extent possible. Having standard intake materials that include prompts to ask teams about their goals, as well as about their traditions or norms can help remove feelings of “otherness.” Examples for guardians can include items such as “Are there any practices within your home that you would like us to follow (e.g., shoes taken off or kept on)?”; “Are there practices around eating that you would like us to know so we can follow them?”; and “There are a variety of ways we can send out communication, such as through emails, letters sent home, phone calls. What method would you prefer?” Asking these direct questions at the beginning can open communication between the behavior analyst and the family and can prevent several of the missteps that often arise due to lack of knowledge or assumptions (Cole, 2008; Sanders, 2009).

In addition, revisiting these questions over time is important; the goal is to build more trust, thus, making it easier for teams to disclose their true viewpoints when practitioners demonstrate that they provide culturally responsive services. As time passes and families become more familiar with the behavior analyst, they may want to make changes. They may share new thoughts they have held since the original discussion after trust has been built.

Being Aware of Jargon and Type of Communication

Aligning with Standard 2.08: Communicating About Services, behavior analysts must use understandable language when communicating. Research demonstrates that the jargon used by behavior analysts is perceived negatively by others (Becirevic et al., 2016; Conners & Capell, 2020; Critchfield et al., 2017). Behavior analytic terminology and jargon affects both the client’s and guardian’s perspectives on the services that are provided and may make it difficult to understand intervention goals and procedures. Approachable and easy to understand language will support quality collaboration between behavior analysts, their clients, and the client’s team. Baires et al. (2022) discuss how systemic change will occur when the importance and depth of listening and intercultural communication is understood. For behavior analysts this means that the use of jargon not only creates a barrier for the client and their team to engage in programming decisions, but also that communication with little to no language consideration between people with different cultural backgrounds also creates a disconnect between the two parties.

Indeed, behavior analysts should be attentive to the overall complexity and method of their communication. Building further on identifying biases and assumptions, behavior analysts cannot assume the style of communication they use is appropriate. When communicating with the client’s team, behavior analysts should actively think about elements such as the languages used in the home, the education and reading level of the recipient, and the functional and preferred methods of communication. With all of the barriers to behavior analytic practices, like the diversity of languages, having correspondences that are accessible can help create a more cohesive relationship.

Having Resources Readily Available for Team Members

Effective communication can also be supported by having resources readily available. As team members and clients are likely unfamiliar with behavior analytic services, the amount of “new” can often be overwhelming with new transitions (Freedman, 2016; Martinez & Mahoney, 2022). Having easy-to-navigate, accessible information about behavior analytic services, relevant laws and client rights, and various advocacy and support groups can help remove some pressure for those just beginning the ABA journey. Providing these resources to the client and their team members can remove some of the responsibility off of them to both find the information and also to determine the legitimacy and quality of the information. In addition, letting the client’s team know there are networks of support can help foster a greater sense of community. These networks can help clients and their team learn more about different ways that behavior analytic services can look, which can then help behavior analysts to identify ways to better tailor services to best meet their needs.

Moving Forward

Standard: 1.07 Cultural Responsiveness and Diversity is just one of the many elements added to the 2022 Code that went into effect on January 1, 2022. Through situating this Standard within the inequities present in today’s society, this article provided both the context for the new Standard, as well as the rationale for its inclusion. Then, to ensure behavior analysts move beyond simply having background knowledge, we provided specific behaviors and recommendations situated in multiple aspects of our work as behavior analysts.

As all the knowledge necessary to be culturally responsive could never fit into one single outlet, it is also important to recognize that too brief of introductions cannot be of much assistance in bringing content into action. In an attempt to balance breadth and depth, the content within this manuscript is both meant to sufficiently introduce the topic while also providing enough information and actions to move beyond the surface level. Along with interacting with academic sources, there are various other actions behavior analysts can take, including (1) join and create special interest groups within various organizations like the Association of Behavior Analysis International (e.g., Culture and Diversity Group); (2) join online educational communities across social media platforms; (3) join various associations related to diversity (e.g., Black Applied Behavior Analysts, Latino Association For Behavior Analysis); and (4) seek continuing education units that focus on culturally relevant practices and topics.

The task of becoming more competent in an area such as cultural responsiveness is not a simple, finite undertaking. Maintaining contact with this and related content will be essential for all practitioners to keep improving behavior analytic services and bettering the field. The hope is for this article to be a steppingstone in the process for answering the calls of many behavior analysts to engage in a behavior analytic evolution.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethical Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

Not applicable.

Footnotes

We use “disabled person/people” intentionally in recognition of the countermovement against person-first language that is being voiced by the disability community. Disabled is not a bad word.

We recognize that the term “stakeholder” is rooted in colonial practices. For the purposes of the article, the term is used when naming Standard 2.09 but has been replaced with the word “team” thereafter.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Adolph KE, Karasik LB, Tamis-Lemonda CS. Motor skills. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of cultural developmental science. Psychology Press; 2010. pp. 61–88. [Google Scholar]

- Annamma SA, Connor D, Ferri B. Dis/ability critical race studies (DisCrit): Theorizing at the intersections of race and dis/ability. Race Ethnicity & Education. 2013;16(1):1–31. doi: 10.1080/13613324.2012.730511. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Avendano SM, Cho E. Building collaborative relationships with parents: A checklist for promoting success. TEACHING Exceptional Children. 2020;52(4):250–260. doi: 10.1177/0040059919892616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baires NA, Catrone R, May BK. On the importance of listening and intercultural communication for actions against racism. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2022;15:1042–1049. doi: 10.1007/s40617-021-00629-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baptist EE. The half has never been told: Slavery and the making of American capitalism. Hachette UK; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu L, Addington J, Almeida D. Behavior analysts’ training and practices regarding cultural diversity: The case for culturally competent care. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2019;12(3):557–575. doi: 10.1007/s40617-018-00313-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu, B. (2020). Call for the BACB to denounce racial injustice. Change.org. Retrieved September 18th, 2022 from https://www.change.org/p/aba-professionals-call-for-the-bacb-to-denounce-racial-injustice

- Becirevic A, Critchfield TS, Reed DD. On the social acceptability of behavior-analytic terms: Crowdsourced comparisons of lay and technical language. The Behavior Analyst. 2016;39(2):305–317. doi: 10.1007/s40614-016-0067-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (n.d.). BACB certificant data. Retrieved September 18th, 2022 from https://www.bacb.com/BACB-certificant-data

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2014). Professional and ethical compliance code for behavior analysts.

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2020a). BACB statement in response to the death of George Floyd. [Status Update] Facebook. Retrieved September 18th, 2022 from https://www.facebook.com/BehaviorAnalystCertificationBoard/posts/3130978453635489

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2020b). Ethics code for behavior analysts. Retrieved September 18th, 2022 from https://www.bacb.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Ethics-Code-for-Behavior-Analysts-230119-a.pdf

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2022, February). Special edition on 2025 BCBA and BCaBA examinations. BACB Newsletter. Retrieved September 18th, 2022 from https://www.bacb.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/BACB_February2022_Newsletter-220207.pdf

- Boveda M, Aronson BA. Special education preservice teachers, intersectional diversity, and the privileging of emerging professional identities. Remedial & Special Education. 2019;40(4):248–260. doi: 10.1177/0741932519838621. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cole RW. Educating everybody's children: Diverse teaching strategies for diverse learners. ASCD; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Conners BM, Capell ST, editors. Multiculturalism and diversity in applied behavior analysis: Bridging theory and application. Routledge; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Conners BM, Johnson A, Duarte J, Murriky R, Marks K. Future directions of training and fieldwork in diversity issues in applied behavior analysis. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2019;12(4):767–776. doi: 10.1007/s40617-019-00349-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper JO, Heron TE, Heward WL. Applied behavior analysis. Pearson Education; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics, University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989(1), Article 8. http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol1989/iss1/8

- Critchfield TS, Doepke KJ, Epting LK, Becirevic A, Reed DD, Fienup DM, Kremsreiter JL, Ecott CL. Normative emotional responses to behavior analysis jargon or how not to use words to win friends and influence people. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2017;10(2):97–106. doi: 10.1007/s40617-016-0161-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danso R. Cultural competence and cultural humility: A critical reflection on key cultural diversity concepts. Journal of Social Work. 2018;2(4):410–430. doi: 10.1177/1468017316654341. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dean RG. The myth of cross-cultural competence. Families in Society. 2001;82(6):623–630. doi: 10.1606/1044-3894.151. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeFelice KA, Diller JW. Intersectional feminism and behavior analysis. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2019;12(4):831–838. doi: 10.1007/s40617-019-00341-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza, L., Matera, C., & Magruder, E. S. (2010). Family language and interest interview. California Transitional Kindergarten Program. Retrieved September 18th, 2022 from https://earlyedgecalifornia.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/CDE-Sample-Family-Language-Interest-Interview.pdf

- Ferlazzo, L. (2020). Steps to make classrooms more culturally responsive. Education Week. Retrieved September 18th, 2022 from https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/opinion-steps-to-make-classrooms-more-culturally-responsive/2020/03

- Fong EH, Tanaka S. Multicultural alliance of behavior analysis standards for cultural competence in behavior analysis. International Journal of Behavioral Consultation & Therapy. 2013;8(2):17. doi: 10.1037/h0100970. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fong EH, Catagnus RM, Brodhead MT, Quigley S, Field S. Developing the cultural awareness skills of behavior analysts. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2016;9(1):84–94. doi: 10.1007/s40617-016-0111-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman DH. Improving public perception of behavior analysis. The Behavior Analyst. 2016;39(1):89–95. doi: 10.1007/s40614-015-0045-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett M, Borders L, Crutchfield LB, Torres-Rivera E, Brotherton D, Curtis R. Multicultural SuperVISION: A paradigm of cultural responsiveness for supervisors. Journal of Multicultural Counseling & Development. 2001;29:147–158. doi: 10.1002/j.2161-1912.2001.tb00511.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gatzunis KS, Edwards KY, Rodriguez Diaz A, Conners BM, Weiss MJ. Cultural responsiveness framework in BCBA supervision. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2022;15:1373–1382. doi: 10.1007/s40617-022-00688-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays PA. Addressing cultural complexities in practice: A framework for clinicians and counselors. American Psychological Association; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Helton MR, Alber-Morgan SR. Helping parents understand applied behavior analysis: Creating a parent guide in 10 steps. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2018;11(4):496–503. doi: 10.1007/s40617-018-00284-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner-Johnson, W. (2021). Disability, intersectionality, and inequity: Life at the margins. In Public Health Perspectives on Disability (pp. 91–105). Springer. 10.1007/978-1-0716-0888-3_4

- Jensen B. Reading classes: On culture and classism in America. Cornell University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez-Gomez C, Beaulieu L. Cultural responsiveness in applied behavior analysis: Research and practice. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2022;55(3):650–673. doi: 10.1002/jaba.920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson A, Bukard A, Madson M, Pruitt N, Contreras-Tadych D, Kozlowski J, Hess S, Knox S. Supervisor cultural responsiveness and unresponsiveness in cross-cultural supervision. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2006;53(3):288–301. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.53.3.288. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, L. (2020). Cultural competency training requirements for behavior analysts. Change.org. Retrieved September 18th, 2022 from https://www.change.org/p/behavior-analyst-certification-board-aba-cultural-competency-training?recruiter=862855899&utm_source=share_petition&utm_medium=facebook&utm_campaign=share_petition&recruited_by_id=bde451a0-2656-11e8-9e84-571905304f9c

- Latino Association for Behavior Analysts. (2020). Newly released demographic data for the BACB. Retrieved September 18th, 2022 from https://www.laba-aba.com/post/newly-released-demographic-data-for-the-bacb

- Leaf JB, Cihon JH, Leaf R, McEachin J, Liu N, Russell N, Unumb L, Shapiro S, Khosrowshahi D. Concerns about ABA-based intervention: An evaluation and recommendations. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders. 2022;52(6):2838–2853. doi: 10.1007/s10803-021-05137-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemke S. Inequality, poverty and precarity in contemporary American culture. Springer; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Machalicek W, Strickland-Cohen K, Drew C, Cohen-Lissman D. Sustaining personal activism: Behavior analysts as antiracist accomplices. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2022;15:1066–1073. doi: 10.1007/s40617-021-00580-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez S, Mahoney A. Culturally sensitive behavior intervention materials: A tutorial for practicing behavior analysts. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2022;15:516–540. doi: 10.1007/s40617-022-00703-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathur SK, Rodriguez KA. Cultural responsiveness curriculum for behavior analysts: A meaningful step toward social justice. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2022;15:1023–1031. doi: 10.1007/s40617-021-00579-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda K, Garcia Y, Catagnus R, Brandt JA. Can behavior analysis help us understand and reduce racism? A review of the current literature. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2020;13(2):336–347. doi: 10.1007/s40617-020-00411-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCall Z, McHatton PA, Shealey MW. Special education teacher candidate assessment: A review. Teacher Education & Special Education. 2014;37(1):51–70. doi: 10.1177/0888406413512684. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McGill L, Joseph J, Walker M, Nervo LM, Addo T, Guerra A. Voices on diversity: Overcoming our own racial biases. Molecular Cell. 2021;81(6):1117–1119. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2021.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KL, Re Cruz A, Ala’i-Rosales S. Inherent tensions and possibilities: Behavior analysis and cultural responsiveness. Behavior & Social Issues. 2019;28(1):16–36. doi: 10.1007/s42822-019-00010-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mlcek S. Are we doing enough to develop cross-cultural competencies for social work? British Journal of Social Work. 2014;44(7):1984–2003. doi: 10.1093/bjsw/bct044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller CO, Forber-Pratt AJ, Sriken J. Disability: Missing from the conversation of violence. Journal of Social Issues. 2019;75(3):707–725. doi: 10.1111/josi.12339. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nieto, S. (2016). Culturally responsive pedagogy: Some key features. Lecture guide, Amherst.

- Noguera PA. Introduction to “racial inequality and education: Patterns and prospects for the future”. Educational Forum. 2017;81(2):129–135. doi: 10.1080/00131725.2017.1280753. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oliva-Olson, C., Espinosa, L. M., Hayslip, W., & Magruder, E. S. (2019). Many languages, one classroom: Supporting children in superdiverse settings. Retrieved September 18th, 2022 from https://www.naeyc.org/resources/pubs/tyc/dec2018/supporting-children-superdiverse-settings

- Ortiz SM, Joseph MA, Deshais MA. Increasing diversity content in graduate coursework: A pilot investigation. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2023;16:222–231. doi: 10.1007/s40617-022-00714-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry, D. M., & Carter-Long, L. (2016). The Ruderman white paper on media coverage of law enforcement use of force and disability. Ruderman Family Foundation. Retrieved September 18th, 2022 from https://rudermanfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/MediaStudy-PoliceDisability_final-final.pdf

- Planty, M., Hussar, W., Snyder, T., Provasnik, S., Kena, G., Dinkes, R., KewalRamani, A., & Kemp, J. (2008). The condition of education, 2008. NCES 2008-031. National Center for Education Statistics.

- Rogerson CV, Prescott DE, Howard HG. Teaching social work students the influence of explicit and implicit bias: Promoting ethical reflection in practice. Social Work Education. 2022;41(5):1035–1046. doi: 10.1080/02615479.2021.1910652. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, M. G. (2009). Teachers and parents. In Internationalhandbook of research on teachers and teaching (pp. 331–341). Springer.

- Sousa P, Almeida JL. Cultural sensitive social work: Promoting cultural competence. European Journal of Social Work. 2016;19(3):537–555. doi: 10.1080/13691457.2015.1126559. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stone C. The white foundation's role in Black oppression. The Black Scholar. 1971;3(3):29–31. doi: 10.1080/00064246.1971.11431194. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Swidler A. Inequality and American culture: The persistence of voluntarism. American Behavioral Scientist. 1992;35(4–5):606–629. doi: 10.1177/000276429203500414. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Uher, A., Fisher, M. H., & Josol, C. K. (2023). Cultural competency training for the social service professions: A systematic literature review. Multicultural Learning & Teaching. Advance online publication. 10.1515/mlt-2022-0024

- U.S. Department of Education. (2013). For each and every child—A strategy for education equity and excellence. Retrieved September 18th, 2022 from http://www2.ed.gov/about/bdscomm/list/eec/index.html

- Vincent C, Randall C, Cartledge G, Tobin T, Swain-Bradway J. Toward a conceptual integration of cultural responsiveness and schoolwide positive behavior support. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2011;13:219–229. doi: 10.1177/1098300711399765. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wright PI. Cultural humility in the practice of applied behavior analysis. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2019;12(4):805–809. doi: 10.1007/s40617-019-00343-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2017). 10 facts on disability. Retrieved September 18th, 2022 from https://www.who.int/features/factfiles/disability/en/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Not applicable.