Abstract

Generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP) is a chronic, rare, and potentially life-threatening disease. There is limited understanding of patient characteristics in GPP and their correlation with disease progression or healthcare resource utilization. Our review aims to examine real-world evidence on these characteristics and the associated disease burden as related to economic and quality of life factors. Results showed that most patients with GPP experienced flares once a year, lasting from 2 weeks to 3 months, with > 80% of patients having residual disease post-flare, with/without treatment, indicating the long-term nature of GPP. The impact of GPP on patients’ daily activities was significant, even in the absence of a flare. GPP adversely affected mental health, and anxiety and depression were reported regularly. Patients with GPP had more comorbidities, were prescribed more medication, and had more inpatient and outpatient visits than in matched plaque psoriasis or general population cohorts. Improving the education of healthcare providers in diagnosing GPP, defining disease flares, and managing the disease, as well as making globally accepted clinical guidelines for GPP treatment available, could help to reduce the burden on patients with GPP. Effective therapies that control and prevent GPP flares and manage chronic disease are needed.

Keywords: Generalized pustular psoriasis, Comorbidities, Healthcare resource utilization, Quality of life, Real-world evidence, Triggering factors

Key Summary Points

| There is limited knowledge on patient characteristics in generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP) and their correlation with disease progression and/or healthcare resource utilization. |

| This review aims to examine the real-world evidence on these characteristics and the associated disease burden of GPP as they relate to economic and quality of life (QoL) factors. |

| GPP has a significant detrimental impact on QoL, compounded by flare severity, disease chronicity, presence of comorbidities, and effects on mental health. |

| Improving the education of healthcare professionals and obtaining globally accepted guidelines for GPP diagnosis and treatment may reduce the overall burden on patients with GPP by providing consistent clinical management. |

Introduction

Generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP) is a chronic, rare, and potentially life-threatening autoinflammatory disease [1, 2] characterized by an acute, widespread eruption of sterile pustules on erythematous skin [2], known as a flare. GPP flares often require inpatient hospital treatment as potentially life-threatening complications may occur in untreated individuals, including sepsis, respiratory distress, and high-output heart failure [3]. There is often no obvious cause for a GPP flare; however, there may be associated factors [4]. The clinical course of GPP is variable and can be relapsing with recurrent flares or persistent with intermittent flares [4, 5].

Although GPP may present in patients with plaque psoriasis, they are distinct conditions in clinical characteristics, pathology, and genetic background [6–10], and GPP represents < 1% of all psoriasis cases [11]. Lack of clinical awareness, plus variations in its presentation and diagnostic criteria, make it difficult to provide an accurate estimate of disease prevalence, with approximately 2 to 124 cases per 100,000 persons cited in the literature [12–15]. As such, GPP is considered an orphan disease in many jurisdictions, including the USA.

The exact cause of GPP is often unknown, but abnormal interleukin-36 (IL-36) pathway signaling plays a significant role in its immunopathology [10, 16–19]. Mutations in the IL-36 pathway cause a positive feedback loop of uncontrolled inflammatory signaling, leading to excess production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokine induction, and neutrophil recruitment into the epidermis [8]. Some people with GPP have loss-of-function mutations in the IL-36RN gene, which codes for the IL-36 receptor antagonist and is a negative regulator of the IL-36 pathway [10, 17–20]. GPP is also associated with mutations in several other genes linked with the IL-36 pathway [21].

Currently, there is limited knowledge on patient characteristics in GPP and their correlation with disease progression and/or healthcare resource utilization (HCRU). This review aims to examine the real-world evidence on these characteristics and the associated disease burden of GPP as they relate to economic and quality of life (QoL) factors.

Methods

Search Strategy

A literature search was performed on MEDLINE (PubMed) and Google Scholar for English language publications between 2012 and 2022. Inclusion criteria were “Generalized pustular psoriasis” OR “GPP” OR “Generalized PP” plus “Real world” OR “real-world” OR “RWE;” “HEOR” OR “health economic” OR “economic burden;” “Clinical outcome;” “Psycholog*;” “Case stud*;” “Claim*;” “Clinical profile” OR “clinical feature” OR “clinical characteristic;” “HCRU;” “Quality of life;” “Cost analysis;” “Case report*” OR “case series;” and “Database” OR “Optum” OR “Corrona” OR “CorEvitas.”

Study Selection

Titles and abstracts were screened according to search criteria, and 185 articles were identified from 2012 to 2022, of which 37 potentially relevant articles were considered. These were then screened during full-text review, leaving 30 articles for inclusion in this review, which are presented in Table 1 [22–51]. This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included (N = 30)

| Author, year, country | Study type | Overall study sample size (GPP sample) | Date collection period | Data source | Outcomes reported |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North America (N = 9) | |||||

|

Crowley et al. [24] US |

Retrospective study | 68,764 (1669 with GPP) | Oct 2015–Mar 2019 | Optum® Clinformatics® Data Mart |

• Comorbidities • Burden • Burden on QoL (anxiety and depression) • Burden on healthcare |

|

Hanna et al. [27] US |

Retrospective cross-sectional design |

• 71 GPP hospitalizations • 64 GPP emergency department visits |

Oct 2015–Jul 2017 | Cerner Health Facts EMR database |

• Comorbidities • Burden on QoL (anxiety and depression) • Burden on healthcare |

|

Hanna et al. [28] US |

Retrospective matched cohort study |

• Matched plaque psoriasis cohort 3890 (975 with GPP) • Matched general population cohort 3928 (982 with GPP) |

Apr 2016–Aug 2019 | IQVIA PharMetrics Plus US administrative claims database | • Burden on QoL (anxiety and depression, mortality) |

|

Lebwohl et al. [34] US and Canada |

Retrospective cohort study | 4954 (60 with GPP) |

Data cut-off Jan 2020 |

CorEvitas’ (formally Corrona) Psoriasis Registry |

• Comorbidities • Burden on QoL (DLQI, itch/pain/fatigue VAS) |

|

Noe et al. [41] US |

Retrospective, longitudinal case series | 95 | Jan 2007–Dec 2018 |

Participating sites’ electronic health records or site-specific databases |

• Patient characteristics and clinical features • Triggering factors • Comorbidities • Burden on healthcare |

|

Reisner et al. [45] US |

Survey based study | 66 respondents | Aug 2020 | Opt-in market research database (name undisclosed) |

• Patient characteristics and clinical features • Triggering factors • Comorbidities • Burden on QoL (anxiety and depression) |

|

Sobell et al. [46] US |

Retrospective matched cohort study |

• 1175 with GPP • 75,494 with plaque psoriasis 4312 matched general population cohort |

Oct 2015–Sep 2018 | Optum® and IBM® MarketScan® databases |

• Comorbidities • Burden on QoL (anxiety and depression) • Burden on healthcare |

|

Strober et al. [47] US and Canada |

Survey based study | 29 dermatologist respondents | Not given | Corrona Psoriasis Registry (now called CorEvitas) | • Patient characteristics and clinical features |

|

Zema et al. [51] US |

Retrospective observational cohort study | 1535 | Jul 2015–Jun 2020 | US electronic health records |

• Patient characteristics and clinical features • Comorbidities • Burden on QoL (anxiety and depression) |

| South America (N = 1) | |||||

|

Duarte et al. [25] Brazil |

Cross-sectional study | 30,004 (1458 with GPP) | Jan 2018–Aug 2020 | Outpatient Information System (SIA–Sistema de Informações Ambulatoriais) | • Burden on QoL (mortality) |

| Europe (N = 5) | |||||

|

Gisondi et al. [26] Italy |

Retrospective study | 140 (13 with GPP) | 2005–2021 | Electronic database of the Dermatology Division of University Hospital of Verona | • Patient characteristics and clinical features |

|

Kara Polat et al. [31] Turkey |

Retrospective, longitudinal case series | 156 | Mar 2020–Sep 2020 | 23 different dermatological departments |

• Patient characteristics and clinical features • Triggering factors • Burden on QoL (DLQI, mortality) |

|

Kharawala et al. [32] UK |

Review article | 19 publications | 2005–2018 | PubMed and EMBASE® databases | • Burden on QoL (SF-36) |

| Löfvendahl et al. [35] Sweden | Longitudinal population-based registry study | 4961 (914 with GPP) | 2004–2015 | Swedish National Patient Register |

• Patient characteristics and clinical features • Burden on healthcare |

| Löfvendahl et al. [36] Sweden | Longitudinal population-based registry study | 153,733 (1093 with GPP) | 2004–2015 | Swedish National Patient Register | • Patient characteristics and clinical features |

| Asia (N = 15) | |||||

|

Chao and Tsai [22] Taiwan |

Retrospective case series | 7 | Jan 2015–Oct 2021 | Department of Dermatology, National Taiwan University Hospital, Taiwan | • Patient characteristics and clinical features |

|

Choon et al. [23] Malaysia |

Retrospective study | 102 | 1989–Nov 2011 |

Electronic and manual records at the Department of Dermatology in Hospital Sultanah Aminah Johor Bahru, Malaysia |

• Patient characteristics and clinical features • Triggering factors Comorbidities • Burden on QoL (DLQI, mortality) |

|

Hayama et al. [29] Japan |

Questionnaire based study | 83 | 2016–2019 | Hospitals/facilities providing dermatological training under the certification of the Japanese Dermatological Association | • Patient characteristics and clinical features |

|

Jin et al. [30] South Korea |

Retrospective study | 33 | Jan 2002–Dec 2012 | Pusan National University Hospital and Busan Paik Hospital, South Korea |

• Patient characteristics and clinical features • Triggering factors • Burden on QoL (mortality) |

|

Lau et al. [33] Malaysia |

Retrospective case series | 27 | Nov 2015–Apr 2016 |

Medical records of dermatologist-confirmed GPP |

• Patient characteristics and clinical features • Triggering factors |

|

Lu and Shi [37] China |

Review article | NA | NA | NA | • Patient characteristics and clinical features |

|

Manone-Zenke et al. [38] Japan |

Retrospective cohort study | 1359 (27 with GPP) | Jul 2003–Mar 2021 | St Luke’s International Hospital, Tokyo, Japan | • Patient characteristics and clinical features |

|

Miyachi et al. [39] Japan |

Retrospective cohort study | 1516 | Jul 2010–Mar 2019 |

Diagnosis Procedure Combination database |

• Patient characteristics and clinical features • Comorbidities • Burden on QoL (mortality) |

|

Morita et al. [40] Japan |

Retrospective cohort study |

• 718 with GPP • 27,773 with plaque psoriasis • 2867 matched general population cohort |

Jul 2014–Dec 2019 | Japanese MDV database |

• Patient characteristics and clinical features • Comorbidities • Burden on QoL (anxiety and depression) • Burden on healthcare |

|

Ohata et al. [42] Japan |

Retrospective cohort study | 1394 (104 with GPP) | Jan 2010–Dec 2020 | West Japan Psoriasis Registry |

• Patient characteristics and clinical features • Triggering factors • Comorbidities |

|

Ohn et al. 2022 [43] South Korea |

Retrospective cohort study | 800 | Jan 2007–Dec 2020 |

Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service |

• Patient characteristics and clinical features • Comorbidities • Burden on QoL (mortality) |

|

Okubo et al. [44] Japan |

Retrospective cohort study |

• 148 with GPP • 28,129 with plaque psoriasis • 586 matched general population cohort |

Jan 2015–Dec 2019 |

Japanese Medical Data Center database |

• Patient characteristics and clinical features • Comorbidities • Burden on healthcare |

|

Tosukhowong et al. [48] Thailand |

Retrospective cohort study | 60 (48 with GPP) | Jan 2005–Jun 2020 | Dermatology Clinic, Maharaj Nakorn Chiang Mai Hospital, Thailand |

• Patient characteristics and clinical features • Triggering factors |

|

Wang et al. [49] China |

Retrospective study | 26 | Jan 2005–Dec 2014 | Inpatients medical records |

• Patient characteristics and clinical features • Triggering factors • Burden on QoL (mortality) |

|

Wang et al. [50] China |

Ambispective study | 66 | Jan 2013–Jul 2014 | Department of Dermatology, Xinhua Hospital, Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China | • Triggering factors |

DLQI Dermatology Life Quality Index, EMR electronic medical record, GPP generalized pustular psoriasis, NA not applicable, QoL quality of life, SF-36 36-Item Short Form Health Survey, VAS visual analog scale

Results

Patient Characteristics, Clinical Features, and Disease Course in GPP

Demographics

The majority of studies reported a higher prevalence of GPP in women [23, 30, 48], although studies from China and Japan reported a higher prevalence in men [29, 37, 39, 40, 42, 44]. The overall mean age of onset of GPP was 36.1 to 50.3 years [23, 30, 31, 41, 42, 48], juvenile onset (age of onset < 18 years of age) was 6.3 to 8.0 years [30, 31], and elderly onset (age of onset > 60 years of age) was 70.7 years [22]. In an online survey of US patients with GPP (N = 66), respondents reported delays in GPP diagnosis, with 36% of patients living with symptoms for months and 38% of patients living with symptoms for years [45].

Plaque Psoriasis

There was a wide variation in the percentage of patients with GPP with a history of plaque psoriasis (range 42.4–77.8%) [23, 30, 31, 35, 36, 38, 43]. In a small retrospective study of patients with GPP at two sites in South Korea (N = 33), patients who had a history of plaque psoriasis were more likely to have a flare (90.0%) versus those without (66.7%) [30]. Two further retrospective studies of patients with pustular psoriasis from Thailand (n = 48) and Italy (n = 13) reported GPP and concomitant plaque psoriasis in approximately 31% of patients [26, 48].

Disease Chronicity and Flare Characteristics

In an online survey of US patients with GPP, all patients had experienced one or more flare in the past 12 months, and 86% had experienced two or more GPP flares in the past 12 months [45]. In a retrospective cohort study of US patients with GPP, 271 patients had documented flares, of whom 182 (63%) had one flare during the follow-up period (mean 724.8 days); the mean number of flares per patient per year was 0.88 [51]. In a retrospective South Korean study, patients with follow-up for ≥ 1 year had a relapse rate of 76% [30]. The majority of dermatologists (69%) in the US and Canada estimated that their patients had zero to one flare per year, whereas 28% estimated two to three flares per year [47]. More than half (55%) of the estimated flares lasted 2 to 4 weeks, and 41% of patients reported that flares lasted from 1 to 3 months [47]. In an online survey, approximately 54% of patients with GPP had been diagnosed for 1 to 10 years, with 40% having been diagnosed for > 10 years [45]. Patients with GPP often live with symptoms from months to years before receiving a diagnosis. When their GPP was under control, patients stated that symptoms caused minimal pain (38%) or no pain or discomfort (39%), and 70% of patients reported symptoms were of low severity [45].

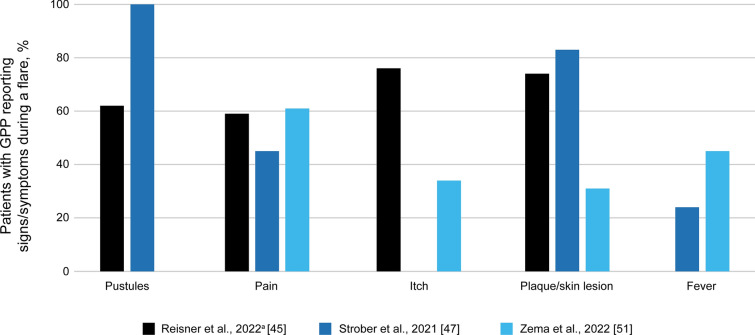

The main signs and symptoms associated with a diagnosed GPP flare were skin pustules [45, 47], pain [45, 47, 51], itch [45, 51], plaque/skin lesions [45, 47, 51], and fever [12, 47, 51] (Fig. 1). Other signs and symptoms include erythema (76%), increase in size of affected area (74%), rash (46%), skin scaling (31%), malaise (31%), and edema (24%) [45, 47, 51]. Although most pustules appeared on the trunk and extremities, pustules were also observed on the scalp, face, genitals, nail unit, and mucous membranes [23, 33, 41, 49]. During a flare, laboratory investigations revealed the presence of elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, leukocytosis, thrombocytosis, lymphopenia, and raised liver enzymes [23, 49]. Data from the dermatologists’ survey (N = 29) reported that for flares to be considered as resolved, there must be few to no pustules (83%), reduced to no erythema (83%), and minimal to no skin lesions (66%) [47]. It has been reported that time to resolution of skin lesions was 2 to 4 weeks for pustules (52%), 1 to 3 months for erythema (48%), and 1 to 3 months for scaling (59%) [47]. The majority (83%) of patients had some degree of residual disease post-flare, including skin scaling (76%), skin lesions (66%), and erythema (66%) [47], that continued to impact QoL.

Fig. 1.

Signs and symptoms associated with a diagnosed generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP) flare across studies. aIn the study by Reisner et al., reasons for GPP flares were self-reported. Data were collated from Reisner et al. [45], Strober et al. [47], and Zema et al. [51]. Not all symptoms were reported in each paper

Triggering Factors for GPP Flares

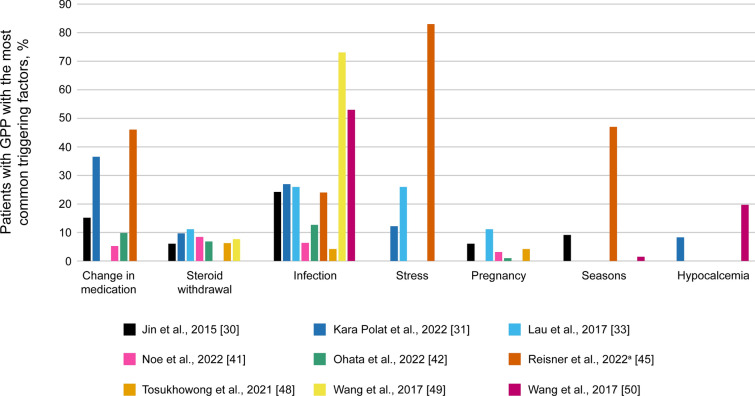

Flares tend to be triggered by certain internal and external factors, but identifiable triggers are not always found. The proportion of patients with unknown triggers was 14.7–62.1% [23, 41, 42]. The main triggers included changes in medication (particularly corticosteroid withdrawal) [30, 31, 33, 41, 42, 45, 48, 49], infections [30, 31, 33, 41, 42, 45, 48–50], and emotional stress [31, 33, 45]. Pregnancy [30, 33, 41, 42, 48], seasonal changes [30, 49, 50], and hypocalcemia [31, 50] are less common triggers (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Common triggering factors for GPP flares identified across studies. aIn the study by Reisner et al., reasons for GPP flares were self-reported. Data were collated from Jin et al. [30], Kara Polat et al. [31], Lau et al. [33], Noe et al. [41], Ohata et al. [42], Reisner et al. [45], Tosukhowong et al. [48], Wang et al. [49], and Wang et al. [50]. Not all triggering factors were reported in each paper

GPP Comorbidities

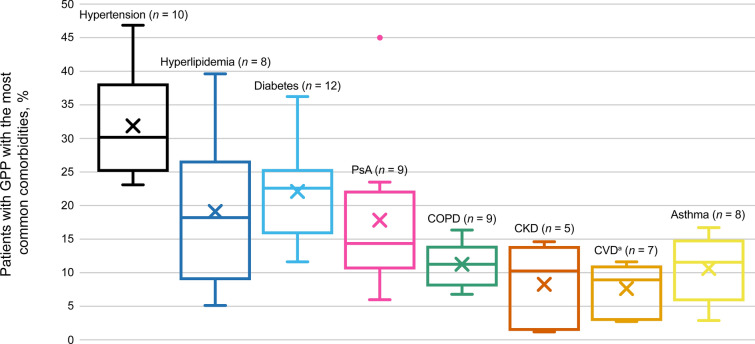

Thirteen studies described comorbidities with GPP, of which hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and psoriatic arthritis were the most common (Fig. 3). Other comorbidities reported in the literature included allergic rhino-conjunctivitis (2 studies; 8.5–30.9%) [40, 44] and obesity (3 studies; 9.2–59.3%) [23, 24, 34].

Fig. 3.

Proportion of patients with GPP reporting comorbidities across studies. X denotes the mean value for each condition. Thirteen studies were included. The number of studies mentioning each comorbidity is shown in the chart labels. aCardiovascular disease (CVD) includes ischemic heart disease, congestive heart failure (HF), chronic HF, and coronary disease. Data were collated from Choon et al. [23], Crowley et al. [24], Hanna et al. [27], Lebwohl et al. [34], Miyachi et al. [39], Morita et al. [40], Noe et al. [41], Ohata et al. [42], Ohn et al. [43], Okubo et al. [44], Reisner et al. [45], Sobell et al. [46], and Zema et al. [51]. CKD chronic kidney disease, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, PsA psoriatic arthritis

A higher proportion of patients with GPP was diagnosed with comorbidities than individuals with other forms of psoriasis or matched general population controls [24, 28, 40, 44, 46]. In a retrospective South Korean study of GPP (N = 800), patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) were significantly older; more frequently had liver disease, hypertension, diabetes, and/or renal disease; and were more likely to have a history of myocardial infarction (MI) than those not admitted to the ICU.

Burden on Patient QoL, Daily Activities, and Mental Health

GPP impacts a person’s daily life, whether that individual is experiencing a flare, is between flares, or is in remission [45]. In patients with GPP, the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) mean score was 7.8 to 12.4 [23, 31, 34], where a score of 6 to 10 indicates a moderate effect on QoL and a score of 11 to 20 indicates a very large effect. In a survey of 60 patients with GPP from the CorEvitas (formerly Corrona) Psoriasis Registry, 30.0% of patients responded that GPP had a very large effect on their QoL per the DLQI score, with 38.3% reporting a small effect and 16.7% reporting no effect [34]. Patients also reported greater median (interquartile range [IQR]) pain (20 [3–62] vs 5 [0–35]), fatigue (44 [15–73] vs 20 [4–50]), and itch (59 [10–85] vs 22 [5–70]) than those with plaque psoriasis (N = 4894) [34]. In a literature review of GPP [32], a study of QoL using the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey in patients with psoriasis (N = 380; of which 3% had pustular psoriasis) reported that QoL in patients with pustular psoriasis was lower than in those with plaque or guttate psoriasis (no statistical analysis was performed) [52]. An online survey of patients with GPP (N = 66) reported that even in the absence of flare symptoms, GPP had a high impact on a patient’s ability to be intimate with a partner (23%), exercise (21%), attend important life events (15%), or wear shoes (15%) [45]. This impact was greater during flares (impact on the ability to exercise, 58%; be intimate with a partner, 52%; wear shoes, 47%; complete errands, 44%; or socialize with friends and family, 41%). In general, patients reported feeling comfortable asking questions about GPP (86%) and felt their healthcare provider (HCP) understood their diagnosis (89%). However, 50% of patients felt HCPs did not understand the level of emotional and physical pain caused by GPP [45].

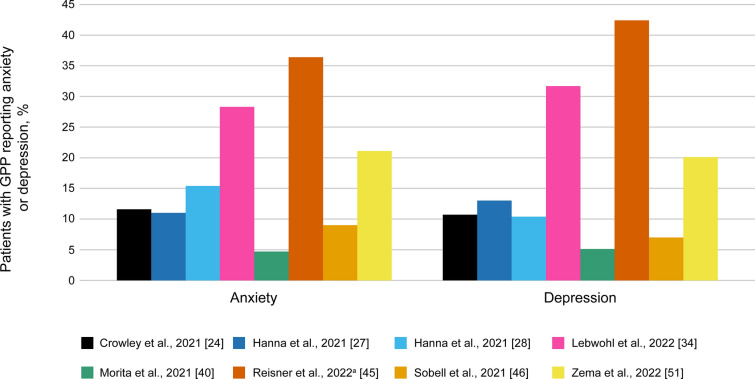

Several studies reported an impact on mental health, with patients commonly experiencing anxiety or depression (Fig. 4). More patients with GPP reported anxiety or depression versus those with plaque psoriasis or general population-matched cohorts [24, 40, 46].

Fig. 4.

Proportion of patients with GPP reporting anxiety and depression across studies. aIn the study by Reisner et al., anxiety and depression were self-reported. Data were collated from Crowley et al. [24], Hanna et al. [27], Hanna et al. [28], Lebwohl et al. [34], Morita et al. [40], Reisner et al. [45], Sobell et al. [46], and Zema et al. [51]

Burden on Healthcare Systems

All-cause outpatient visits were higher in patients with GPP in the US and Japan versus those with plaque psoriasis (28.7 vs 22.6 visits [24]; 15.7 vs 13.8 [40]; 14.8 vs 11.0 [44]). Data from a Swedish registry study (GPP, N = 914; plaque psoriasis, N = 2556; general population, N = 4047) reported that patients with GPP had two or more all-cause HCP visits versus general population-based controls and one more visit compared with plaque psoriasis controls [35]. The mean length of inpatient stays for patients with GPP was approximately 7 and 6 days longer than general population-based controls and plaque psoriasis controls, respectively [35]. Data from a US GPP case series (N = 95) reported that 36.8% of patients were hospitalized during their initial presentation and 67.4% were treated with systemic therapies, with 17 different systemic therapies being used during the index visit [41]. HCRU for 53 patients with ≥ 6 months of follow-up revealed that 35.8% of patients were hospitalized for disease flares at a median rate of 0.5 hospitalizations per year (IQR 0.4–1.6); the median number of reported dermatology visits was 3.2 per year (IQR 2.2–6.1; maximum of 18 visits); and eight patients had additional GPP-specific emergency department visits (median 0.5; IQR 0.4–1.3) [41]. Overall, patients with GPP received more concomitant medication during a 12-month follow-up than those with plaque psoriasis [24, 40, 44, 46]. A higher proportion of patients with GPP was prescribed opioid pain medication (36.1–39.8%) than patients with plaque psoriasis (24.3–24.8%) [24, 46].

In a US study of patients diagnosed with GPP from a health plan database (IQVIA PharMetrics Plus), the total direct cost per GPP patient per month was higher than costs from the matched plaque psoriasis and general population cohorts ($3175 vs $2031 vs $518, respectively) [28], mainly comprising pharmacy costs [28]. In Sweden, the total annual direct cost per GPP patient during 12-month follow-up was €5062, more than three times higher than for population-based controls (€1610). All-cause inpatient stays represented the largest share of total costs [35]. Approximately 33% of the costs appeared to be directly attributable to the consequences and complications of GPP [35]. In Japan, all-cause total cost during 12-month follow-up was ¥1.27 million for patients with GPP versus ¥284.5 K in the matched plaque psoriasis cohort [44].

These data were published prior to the recent approval of spesolimab for the treatment of GPP flares. However, they suggested that previous treatment options for GPP were suboptimal and were associated with high costs due to patients cycling through different treatment regimens, frequent hospitalization, and the management of comorbidities [24, 40, 41, 46].

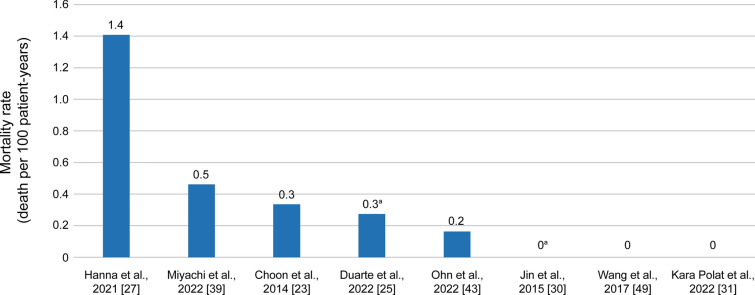

Mortality Rates

Hospital mortality rates for GPP varied from 0 to 1.4 deaths per 100 patient-years (Fig. 5) [23, 25, 27, 30, 31, 39, 43, 49]. In a retrospective South Korean study of GPP (N = 800), patients who died from GPP were older and were more likely to have hypertension, renal disease, and a history of MI than survivors [43].

Fig. 5.

Mortality rate in patients hospitalized with GPP. Assumes deaths occurred evenly across study follow-up, and all patients remained in the study for the entire study duration. aMortality rate in patients with acute GPP (von Zumbusch type); other studies report mortality rate in patients with GPP overall. Data were collated from Choon et al. [23], Duarte et al. [25], Hanna et al. [27], Jin et al. [30], Kara Polat et al. [31], Miyachi et al. [39], Ohn et al. [43], and Wang et al. [49]

Discussion

The majority of patients with GPP in the reported studies experienced flares once a year, lasting 2 weeks to 3 months. Importantly, approximately 80% of patients had residual disease after an acute flare, impacting QoL and indicating the long-term nature of GPP. Erythema is generally the first symptom to appear during an acute flare and the last symptom to disappear in most patients [47]. GPP has a significant effect on patients’ daily activities, even in the absence of flares, and particularly affects mental health, with anxiety and depression being commonly reported. Although it was not assessed in this review, GPP also impacts patients’ ability to work [34]. Recent literature published on GPP mortality rates range from 0 to 3.3 deaths per 100 patient-years in Italy, Spain, Sweden, and Thailand [53–56]. These data highlight the need for improved GPP management while minimizing lethal side effects. GPP caused a greater burden on healthcare, as patients received more medication (including suboptimal medications) and had more inpatient and outpatient visits than people with plaque psoriasis or the general population. Furthermore, the direct costs per patient were three-fold or greater than for the general population; although indirect costs play a role in GPP burden, they were not included in this review.

Unmet Needs in GPP

Further data describing the acute and long-term burden of GPP, and the health economic pathways and burden of disease, in various populations have been published recently [53, 57–60]. However, there remains an unmet need for improved guidelines for GPP diagnosis and management, improved recognition and understanding of GPP by HCPs, and multi-level support involving primary care, emergency care, and dermatologists [61]. The rarity of GPP and subsequent limited understanding of its presentation and pathogenesis may hinder prompt and accurate diagnosis and initiation of effective treatment. These issues could be helped by the development of standardized international guidelines on GPP diagnosis and management [62]. A Delphi panel of 21 expert dermatologists established a global consensus on the clinical course, diagnosis, treatment goals, and disease management of GPP to enable the development of an evidence-based clinical management algorithm [63]. Similarly, via a validated Delphi method, 32 psoriasis specialists from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation recently formulated consensus statements on GPP management [64].

Providing effective treatment options for patients with GPP remains a major challenge [61]. There is a lack of awareness of new treatment options among HCPs. Patients currently on non-targeted treatments for GPP often continue to experience flares [51], and the frequency of hospitalizations for GPP has not changed over time, indicating the need for better treatments [32]. Given the nature of the disease (i.e., symptoms post-flare, risk of further flares, and/or severe disease requiring ongoing maintenance therapy), long-term management of GPP is also needed. Research on the IL-36 pathway led to the development of a GPP-specific treatment, spesolimab, a first-in-class anti-IL-36 receptor monoclonal antibody, which was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in September 2022 for the treatment of GPP flares in adults [65]. It has since received regulatory approval in the European Union, Japan, China, and Taiwan, with additional countries pending approvals [66]. Data from clinical trials such as the Effisayil™ 1 trial have demonstrated the efficacy and safety of spesolimab in providing rapid and sustained clinical improvement for patients with GPP flares [67–69]. In the Effisayil™ 2 trial, high-dose spesolimab was shown to prevent GPP flares over 48 weeks, with an 84% reduction in the risk of flare development versus placebo (hazard ratio [95% confidence interval]: 0.16 [0.05–0.54]; p = 0.0005) [70]. A 5-year open-label extension study to collate long-term efficacy and safety data for spesolimab is ongoing, with participants recruited from the Effisayil™ 1 and Effisayil™ 2 trials [71, 72]. Several case studies in patients with poor treatment response have seen a rapid and sustained response following treatment with spesolimab [73–76]. A second anti-IL-36 receptor agent, imsidolimab, is in clinical development, and Phase III clinical trials are nearing completion [77, 78]. Several biologics are approved in Japan for the treatment of GPP, including anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α agents (adalimumab, infliximab, and certolizumab pegol), anti-interleukin (IL)-17 agents (IL-17A: secukinumab and ixekizumab; IL-17 receptor: brodalumab), and anti-IL-23 agents (risankizumab and guselkumab) [79, 80]. Prior to this, systemic treatment options for GPP were mainly limited to the off-label use of agents for the treatment of plaque psoriasis [79]. In countries where anti-IL-36 receptor agents are not yet available, there have been some cases of GPP that have been successfully managed with off-label biologics [81].

Limitations

This was not a systematic review; thus, some data may have been excluded if the reports did not contain information on impact of patient characteristics on GPP disease burden or HCRU. As GPP is a rare disease, the published literature database is limited, and large high-quality prospective observational studies are lacking. Definitions and classifications of GPP used in different studies are not consistent, which renders comparisons between studies difficult, and the data arise from small (and some medium-sized) retrospective studies. Furthermore, only English articles were included so this review may not fully account for regional variations. Finally, some of these studies are surveys of patients with GPP so it is unclear whether the self-reported diagnoses are accurate.

Conclusions

GPP has a significant detrimental impact on QoL, compounded by flare severity, disease chronicity, presence of comorbidities, and effects on mental health. Current treatments used for GPP are suboptimal, and the economic burden of disease is greater for patients with GPP versus those with plaque psoriasis or the general population, particularly regarding healthcare and treatment costs. Improving the education of HCPs and obtaining globally accepted guidelines for GPP diagnosis and treatment may reduce the overall burden on patients with GPP by providing consistent clinical management. Increased availability of targeted GPP-specific treatment is needed, such as an effective long-term therapy that controls and prevents GPP flares.

Acknowledgments

Medical Writing and Editorial Assistance.

Writing support was provided by Nikita Vekaria, PhD, and Debra Brocksmith, MB, ChB, PhD, of Envision Pharma Group, which was contracted and funded by BIPI.

Authorship.

The authors meet criteria for authorship as recommended by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE). The authors received no direct compensation related to the development of the manuscript. Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (BIPI) were given the opportunity to review the manuscript for medical and scientific accuracy as well as intellectual property considerations.

Author Contributions

Tina Bhutani and Aaron S. Farberg designed the study, participated in writing the paper, reviewed the drafts and approved the final version.

Funding

This manuscript and the journal’s Rapid Service Fee was funded by Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (BIPI).

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Tina Bhutani is a Principal Investigator for trials sponsored by AbbVie, Castle Biosciences, CorEvitas, Dermavant, Galderma, Mindera, and Pfizer; has received research grant funding from Novartis and Regeneron; and has been an advisor for AbbVie, Arcutis, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly and Company, Janssen, Leo, Novartis, Pfizer, Sun Pharma, and UCB. Aaron S. Farberg is an advisory board member for Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Castle Biosciences, Eli Lilly and Company, Galderma, Incyte, Novartis, Ortho Dermatologics, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi, Sun Pharma, and UCB.

Ethical Approval

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

References

- 1.Ly K, Beck KM, Smith MP, Thibodeaux Q, Bhutani T. Diagnosis and screening of patients with generalized pustular psoriasis. Psoriasis (Auckl) 2019;9:37–42. doi: 10.2147/PTT.S181808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benjegerdes KE, Hyde K, Kivelevitch D, Mansouri B. Pustular psoriasis: pathophysiology and current treatment perspectives. Psoriasis (Auckl) 2016;6:131–144. doi: 10.2147/PTT.S98954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prinz JC, Choon SE, Griffiths CEM, Merola JF, Morita A, Ashcroft DM, et al. Prevalence, comorbidities and mortality of generalized pustular psoriasis: a literature review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023;37(2):256–273. doi: 10.1111/jdv.18720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choon SE, Navarini AA, Pinter A. Clinical course and characteristics of generalized pustular psoriasis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23(Suppl 1):21–29. doi: 10.1007/s40257-021-00654-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Navarini AA, Burden AD, Capon F, Mrowietz U, Puig L, Koks S, et al. European consensus statement on phenotypes of pustular psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(11):1792–1799. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Onoufriadis A, Simpson MA, Pink AE, Di Meglio P, Smith CH, Pullabhatla V, et al. Mutations in IL36RN/IL1F5 are associated with the severe episodic inflammatory skin disease known as generalized pustular psoriasis. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;89(3):432–437. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Setta-Kaffetzi N, Navarini AA, Patel VM, Pullabhatla V, Pink AE, Choon SE, et al. Rare pathogenic variants in IL36RN underlie a spectrum of psoriasis-associated pustular phenotypes. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133(5):1366–1369. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marrakchi S, Puig L. Pathophysiology of generalized pustular psoriasis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23(Suppl 1):13–19. doi: 10.1007/s40257-021-00655-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bachelez H, Barker J, Burden AD, Navarini AA, Krueger JG. Generalized pustular psoriasis is a disease distinct from psoriasis vulgaris: evidence and expert opinion. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2022;18(10):1033–1047. doi: 10.1080/1744666X.2022.2116003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marrakchi S, Guigue P, Renshaw BR, Puel A, Pei XY, Fraitag S, et al. Interleukin-36-receptor antagonist deficiency and generalized pustular psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(7):620–628. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1013068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kubota K, Kamijima Y, Sato T, Ooba N, Koide D, Iizuka H, et al. Epidemiology of psoriasis and palmoplantar pustulosis: a nationwide study using the Japanese national claims database. BMJ Open. 2015;5(1):e006450. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Augey F, Renaudier P, Nicolas JF. Generalized pustular psoriasis (Zumbusch): a French epidemiological survey. Eur J Dermatol. 2006;16(6):669–673. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohkawara A, Yasuda H, Kobayashi H, Inaba Y, Ogawa H, Hashimoto I, et al. Generalized pustular psoriasis in Japan: two distinct groups formed by differences in symptoms and genetic background. Acta Derm Venereol. 1996;76(1):68–71. doi: 10.2340/00015555766871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee JY, Kang S, Park JS, Jo SJ. Prevalence of psoriasis in Korea: a population-based epidemiological study using the Korean National Health Insurance Database. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29(6):761–767. doi: 10.5021/ad.2017.29.6.761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yan D, Afifi L, Jeon C, Cordoro KM, Liao W. A cross-sectional study of the distribution of psoriasis subtypes in different ethno-racial groups. Dermatol Online J. 2018 doi: 10.5070/D3247040909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnston A, Xing X, Wolterink L, Barnes DH, Yin Z, Reingold L, et al. IL-1 and IL-36 are dominant cytokines in generalized pustular psoriasis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140(1):109–120. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.08.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Twelves S, Mostafa A, Dand N, Burri E, Farkas K, Wilson R, et al. Clinical and genetic differences between pustular psoriasis subtypes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143(3):1021–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.06.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sugiura K, Takemoto A, Yamaguchi M, Takahashi H, Shoda Y, Mitsuma T, et al. The majority of generalized pustular psoriasis without psoriasis vulgaris is caused by deficiency of interleukin-36 receptor antagonist. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133(11):2514–2521. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hussain S, Berki DM, Choon SE, Burden AD, Allen MH, Arostegui JI, et al. IL36RN mutations define a severe autoinflammatory phenotype of generalized pustular psoriasis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135(4):1067–70e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu ZJ, Tian YT, Shi BY, Zhou Y, Jia XS. Association between mutation of interleukin 36 receptor antagonist and generalized pustular psoriasis: a PRISMA-compliant systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;99(45):e23068. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000023068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uppala R, Tsoi LC, Harms PW, Wang B, Billi AC, Maverakis E, et al. “Autoinflammatory psoriasis”-genetics and biology of pustular psoriasis. Cell Mol Immunol. 2021;18(2):307–317. doi: 10.1038/s41423-020-0519-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chao JP, Tsai TF. Elderly-onset generalized pustular psoriasis: a case series. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47(8):1567–1570. doi: 10.1111/ced.15227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choon SE, Lai NM, Mohammad NA, Nanu NM, Tey KE, Chew SF. Clinical profile, morbidity, and outcome of adult-onset generalized pustular psoriasis: analysis of 102 cases seen in a tertiary hospital in Johor, Malaysia. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53(6):676–684. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crowley J, Golembesky AK, Kotowsky N, Gao R, Bohn RL, Garry EM, et al. Clinical characteristics and healthcare resource utilization in patients with generalized pustular psoriasis: real-world evidence from a large claims-based dataset. J Psoriasis Psoriatic Arthritis. 2021;6(3):151–158. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duarte GV, de Esteves Carvalho AV, Romiti R, Gaspar A, de Gomes Melo T, Soares CP, et al. Generalized pustular psoriasis in Brazil: A public claims database study. JAAD Int. 2022;6:61–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jdin.2021.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gisondi P, Bellinato F, Girolomoni G. Clinical characteristics of patients with pustular psoriasis: a single-center retrospective observational study. Vaccines (Basel) 2022 doi: 10.3390/vaccines10081171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hanna ML, Singer D, Bender SD, Valdecantos WC, Wu JJ. Characteristics of hospitalizations and emergency department visits due to generalized pustular psoriasis in the United States. Curr Med Res Opin. 2021;37(10):1697–1703. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2021.1951192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hanna ML, Singer D, Valdecantos WC. Economic burden of generalized pustular psoriasis and palmoplantar pustulosis in the United States. Curr Med Res Opin. 2021;37(5):735–742. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2021.1894108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hayama K, Fujita H, Iwatsuki K, Terui T. Improved quality of life of patients with generalized pustular psoriasis in Japan: a cross-sectional survey. J Dermatol. 2021;48(2):203–206. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.15657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jin H, Cho HH, Kim WJ, Mun JH, Song M, Kim HS, et al. Clinical features and course of generalized pustular psoriasis in Korea. J Dermatol. 2015;42(7):674–678. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.12863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kara Polat A, Alpsoy E, Kalkan G, Aytekin S, Ucmak D, Yasak Guner R, et al. Sociodemographic, clinical, laboratory, treatment and prognostic characteristics of 156 generalized pustular psoriasis patients in Turkey: a multicentre case series. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36(8):1256–1265. doi: 10.1111/jdv.18103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kharawala S, Golembesky AK, Bohn RL, Esser D. The clinical, humanistic, and economic burden of generalized pustular psoriasis: a structured review. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2020;16(3):239–252. doi: 10.1080/1744666X.2019.1708193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lau BW, Lim DZ, Capon F, Barker JN, Choon SE. Juvenile generalized pustular psoriasis is a chronic recalcitrant disease: an analysis of 27 patients seen in a tertiary hospital in Johor, Malaysia. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56(4):392–399. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lebwohl M, Medeiros RA, Mackey RH, Harrold LR, Valdecantos WC, Flack M, et al. The disease burden of generalized pustular psoriasis: real-world evidence from CorEvitas’ psoriasis registry. J Psoriasis Psoriatic Arthritis. 2022;7(2):71–78. doi: 10.1177/24755303221079814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lofvendahl S, Norlin JM, Schmitt-Egenolf M. Economic burden of generalized pustular psoriasis in Sweden: a population-based register study. Psoriasis (Auckl) 2022;12:89–98. doi: 10.2147/PTT.S359011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lofvendahl S, Norlin JM, Schmitt-Egenolf M. Prevalence and incidence of generalized pustular psoriasis in Sweden: a population-based register study. Br J Dermatol. 2022;186(6):970–976. doi: 10.1111/bjd.20966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lu J, Shi Y. A review of disease burden and clinical management for generalized pustular psoriasis in China. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2022;18(10):1023–1032. doi: 10.1080/1744666X.2022.2118716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Manone-Zenke Y, Ohara Y, Fukui S, Kobayashi D, Sugiura K, Ikeda S, et al. Characteristics of patients with generalized pustular psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: a retrospective cohort study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2022;102:adv00685. doi: 10.2340/actadv.v102.2226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miyachi H, Konishi T, Kumazawa R, Matsui H, Shimizu S, Fushimi K, et al. Treatments and outcomes of generalized pustular psoriasis: a cohort of 1516 patients in a nationwide inpatient database in Japan. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86(6):1266–1274. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morita A, Kotowsky N, Gao R, Shimizu R, Okubo Y. Patient characteristics and burden of disease in Japanese patients with generalized pustular psoriasis: results from the Medical Data Vision claims database. J Dermatol. 2021;48(10):1463–1473. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.16022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Noe MH, Wan MT, Mostaghimi A, Gelfand JM, Agnihothri R, Pustular Psoriasis in the USRG et al. Evaluation of a case series of patients with generalized pustular psoriasis in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158(1):73–78. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.4640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ohata C, Tsuruta N, Yonekura K, Higashi Y, Saito K, Katayama E, et al. Clinical characteristics of Japanese pustular psoriasis: a multicenter observational study. J Dermatol. 2022;49(1):142–150. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.16217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ohn J, Choi YG, Yun J, Jo SJ. Identifying patients with deteriorating generalized pustular psoriasis: development of a prediction model. J Dermatol. 2022;49(7):675–681. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.16383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Okubo Y, Kotowsky N, Gao R, Saito K, Morita A. Clinical characteristics and health-care resource utilization in patients with generalized pustular psoriasis using real-world evidence from the Japanese Medical Data Center database. J Dermatol. 2021;48(11):1675–1687. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.16084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reisner DV, Johnsson FD, Kotowsky N, Brunette S, Valdecantos W, Eyerich K. Impact of generalized pustular psoriasis from the perspective of people living with the condition: results of an online survey. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23(Suppl 1):65–71. doi: 10.1007/s40257-021-00663-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sobell JM, Gao R, Golembesky AK, Kotowsky N, Garry EM, Comerford EO, et al. Healthcare resource utilization and baseline characteristics of patients with generalized pustular psoriasis: real-world results from a large US database of multiple commercial medical insurers. J Psoriasis Psoriatic Arthritis. 2021;6(3):143–150. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Strober B, Kotowsky N, Medeiros R, Mackey RH, Harrold LR, Valdecantos WC, et al. Unmet medical needs in the treatment and management of generalized pustular psoriasis flares: evidence from a survey of Corrona registry dermatologists. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2021;11(2):529–541. doi: 10.1007/s13555-021-00493-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tosukhowong T, Kiratikanon S, Wonglamsam P, Netiviwat J, Innu T, Rujiwetpongstorn R, et al. Epidemiology and clinical features of pustular psoriasis: a 15-year retrospective cohort. J Dermatol. 2021;48(12):1931–1935. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.16164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang Q, Liu W, Zhang L. Clinical features of von Zumbusch type of generalized pustular psoriasis in children: a retrospective study of 26 patients in southwestern China. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92(3):319–322. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20175536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang Y, Cheng R, Lu Z, Guo Y, Yan M, Liang J, et al. Clinical profiles of pediatric patients with GPP alone and with different IL36RN genotypes. J Dermatol Sci. 2017;85(3):235–240. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2016.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zema CL, Valdecantos WC, Weiss J, Krebs B, Menter AM. Understanding flares in patients with generalized pustular psoriasis documented in US electronic health records. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158(10):1142–1148. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.3142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sampogna F, Tabolli S, Soderfeldt B, Axtelius B, Aparo U, Abeni D, et al. Measuring quality of life of patients with different clinical types of psoriasis using the SF-36. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154(5):844–849. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.07071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ericson O, Lofvendahl S, Norlin JM, Gyllensvard H, Schmitt-Egenolf M. Mortality in generalized pustular psoriasis: a population-based national register study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89(3):616–619. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2023.04.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bellinato F, Gisondi P, Marzano AV, Piaserico S, De Simone C, Damiani G, et al. Characteristics of patients experiencing a flare of generalized pustular psoriasis: a multicenter observational study. Vaccines (Basel) 2023 doi: 10.3390/vaccines11040740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Montero-Vilchez T, Grau-Perez M, Garcia-Doval I. Epidemiology and geographic distribution of generalized pustular psoriasis in Spain: a national population-based study of hospital admissions from 2016 to 2020. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2023;114(2):97–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2022.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chaiyabutr C, Silpa-Archa N, Wongpraprarut C, Likittanasombat S, Phumariyapong P, Chularojanamontri L. An analysis of psoriasis hospitalisation in Thailand. Arch Dermatol Res. 2023;315(4):779–786. doi: 10.1007/s00403-022-02429-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Choon SE, De La Cruz C, Wolf P, Jha RK, Fischer KI, Goncalves-Bradley DC, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with generalized pustular psoriasis: a systematic literature review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023 doi: 10.1111/jdv.19530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hayama K, Iwasaki R, Tian Y, Fujita H. Factors associated with generalized pustular psoriasis progression among patients with psoriasis vulgaris in Japan: results from a claims database study. J Dermatol. 2023 doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.16949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lofvendahl S, Norlin JM, Ericson O, Hanno M, Schmitt-Egenolf M. Prolonged sick leave before and after diagnosis of generalized pustular psoriasis: a Swedish population-based register study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2023;103:adv6497. doi: 10.2340/actadv.v103.6497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tarride JE, Prajapati VH, Lynde C, Blackhouse G. The burden associated with generalized pustular psoriasis: a Canadian population-based study of inpatient care, emergency departments, and hospital- or community-based outpatient clinics. JAAD Int. 2023;12:90–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jdin.2023.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Strober B, Leman J, Mockenhaupt M, Nakano de Melo J, Nassar A, Prajapati VH, et al. Unmet educational needs and clinical practice gaps in the management of generalized pustular psoriasis: global perspectives from the front line. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2022;12(2):381–93. doi: 10.1007/s13555-021-00661-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fujita H, Gooderham M, Romiti R. Diagnosis of generalized pustular psoriasis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23(Suppl 1):31–38. doi: 10.1007/s40257-021-00652-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Puig L, Choon SE, Gottlieb AB, Marrakchi S, Prinz JC, Romiti R, et al. Generalized pustular psoriasis: a global Delphi consensus on clinical course, diagnosis, treatment goals and disease management. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023 doi: 10.1111/jdv.18851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Armstrong AW, Elston CA, Elewski BE, Ferris LK, Gottlieb AB, Lebwohl MG, et al. Generalized pustular psoriasis: a consensus statement from the national psoriasis foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023 doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2023.09.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Boehringer Ingelheim. FDA approves the first treatment option for generalized pustular psoriasis flares in adults. (September 01, 2022) Available at: https://www.boehringer-ingelheim.us/press-release/fda-approves-first-treatment-option-generalized-pustular-psoriasis-flares-adults Accessed 14 Nov 2023.

- 66.Boehringer Ingelheim. European Commission approves SPEVIGO® (spesolimab) for generalized pustular psoriasis flares. (December 13, 2022) Available at: https://www.boehringer-ingelheim.com/human-health/skin-diseases/gpp/european-commission-approves-spevigo-spesolimab-generalized Accessed 14 Nov 2023.

- 67.Bachelez H, Choon SE, Marrakchi S, Burden AD, Tsai TF, Morita A, et al. Inhibition of the interleukin-36 pathway for the treatment of generalized pustular psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(10):981–983. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1811317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bachelez H, Choon SE, Marrakchi S, Burden AD, Tsai TF, Morita A, et al. Trial of spesolimab for generalized pustular psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(26):2431–2440. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2111563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Blair HA. Spesolimab: first approval. Drugs. 2022;82(17):1681–1686. doi: 10.1007/s40265-022-01801-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Morita A, Strober B, Burden AD, Choon SE, Anadkat MJ, Marrakchi S, et al. Efficacy and safety of subcutaneous spesolimab for the prevention of generalised pustular psoriasis flares (Effisayil 2): an international, multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2023;402(10412):1541–1551. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)01378-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Boehringer Ingelheim. Effisayil™ ON: A Study to Test Long-term Treatment With Spesolimab in People With Generalized Pustular Psoriasis Who Took Part in a Previous Study. Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/record/NCT03886246. Accessed 14 Nov 2023.

- 72.Navarini A, Bachelez H, Choon S, Burden A, Zheng M, Morita A, et al. 43008 Effisayil ON, an open-label, long-term extension study of spesolimab treatment in patients with generalized pustular psoriasis: interim results for flare treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023 doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2023.07.178. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jiang M, Li Y, Guan X, Li L, Xu W. Rapid response of spesolimab in biologics—failure patient with generalized pustular psoriasis flare. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2023;40(4):584–586. doi: 10.5114/ada.2023.129514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Burns M, Orlowski T, Ho-Pham H, Elston C, Elewski B. New onset generalized pustular psoriasis rapidly improved with IL-36 blockade. SKIN J Cutan Med. 2023;7(1):585–588. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fernández-Galván A, Daudén E, Butron-Bris B, Seguí-Olmedilla M, Miguélez A, Fraga J, et al. First experiences in real clinical practice treating a patient with generalised pustular psoriasis with Spesolimab. JEADV Clin Pract. 2023;2(2):369–372. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ran D, Yang B, Sun L, Wang N, Qu P, Liu J, et al. Rapid and sustained response to spesolimab in five Chinese patients with generalized pustular psoriasis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2023;48(7):803–805. doi: 10.1093/ced/llad108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gudjonsson JE, Randazzo B, Zhou J. 34617 imsidolimab in the treatment of adult subjects with generalized pustular psoriasis: design of a pivotal phase 3 clinical trial and a long-term extension study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2022.06.313. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Warren RB, Reich A, Kaszuba A, Placek W, Griffiths CEM, Zhou J, et al. Imsidolimab, an anti-interleukin-36 receptor monoclonal antibody, for the treatment of generalized pustular psoriasis: results from the phase II GALLOP trial. Br J Dermatol. 2023;189(2):161–169. doi: 10.1093/bjd/ljad083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Krueger J, Puig L, Thaci D. Treatment options and goals for patients with generalized pustular psoriasis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23(Suppl 1):51–64. doi: 10.1007/s40257-021-00658-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Komine M, Morita A. Generalized pustular psoriasis: current management status and unmet medical needs in Japan. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2021;17(9):1015–1027. doi: 10.1080/1744666X.2021.1961580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Avallone G, Maronese CA, Murgia G, Carrera CG, Mastorino L, Roccuzzo G, et al. Interleukin-17 vs. interleukin-23 Inhibitors in pustular and erythrodermic psoriasis: a retrospective, multicentre cohort study. J Clin Med. 2023 doi: 10.3390/jcm12041662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]