Abstract

Background

Suicide is a leading cause of death among post‐secondary students worldwide. Suicidal thoughts and planning are common among post‐secondary students. Previous reviews have examined the effectiveness of interventions for symptomatic individuals; however, many students at high risk of suicide are undiagnosed and untreated.

Objectives

We evaluated the effect on suicide and suicide‐related outcomes of primary suicide prevention interventions that targeted students within the post‐secondary setting.

Search methods

We searched the following sources up to June 2011: Specialised Registers of two Cochrane Groups, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and nine other databases, trial registers, conference proceedings, and websites of national and international organizations. We screened reference lists and contacted authors of included studies to identify additional studies. We updated the search in November 2013; we will include these results in the review's next update.

Selection criteria

We included studies that tested an intervention for the primary prevention of suicide using a randomized controlled trial (RCT), controlled before‐and‐after (CBA), controlled interrupted time series (CITS), or interrupted time series (ITS) study design. Interventions targeted students within the post‐secondary setting (i.e. college, university, academy, vocational, or any other post‐secondary educational institution) without known mental illness, previous suicide attempt or self‐harm, or suicidal ideation. Outcomes included suicides, suicide attempts, suicidal ideation, changes in suicide‐related knowledge, attitudes and behavior, and availability of means of suicide.

Data collection and analysis

We used standardized electronic forms for data extraction, risk of bias and quality of evidence determination, and analysis. We estimated standardised mean differences (SMD) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We analysed studies by intervention type and study design. We summarized RCT effect sizes using random‐effects models meta‐analyses; and analysed statistical heterogeneity using the Chi2 test and I2 statistic. We described narratively the results from studies that used other study designs.

Main results

Eight studies met inclusion criteria. They were heterogeneous in terms of participants, study designs, and interventions. Five of eight studies had high risk of bias. In 3 RCTs (312 participants), classroom‐based didactic and experiential programs increased short‐term knowledge of suicide (SMD = 1.51, 95% CI 0.57 to 2.45; moderate quality evidence) and knowledge of suicide prevention (SMD = 0.72, 95% CI 0.36 to 1.07; moderate quality evidence). The effect on suicide prevention self‐efficacy in one RCT (152 participants) was uncertain (SMD = 0.20, 95% CI ‐0.13 to 0.54; low quality evidence). One CBA analysed the effects of an institutional policy that restricted student access to laboratory cyanide and mandated professional assessment for suicidal students. The incidence of student suicide decreased significantly at one university with the policy relative to 11 control universities, 2.00 vs. 8.68 per 100,000 (Z = 5.90; P < 0.05). Four CBAs explored effects of training 'gatekeepers' to recognize and respond to warning signs of emotional crises and suicide risk in students they encountered. The magnitude of effect sizes varied between studies. Gatekeeper training enhanced short‐term suicide knowledge in students, peer advisors residing in student accommodation, and faculty and staff, and suicide prevention self‐efficacy among peer advisors. There was no evidence of an effect on participants' suicide‐related attitudes or behaviors. One CBA found no evidence of effects of gatekeeper training of peer advisors on suicide‐related knowledge, self‐efficacy, or gatekeeper behaviors measured four to six months after intervention.

Authors' conclusions

We found insufficient evidence to support widespread implementation of any programs or policies for primary suicide prevention in post‐secondary educational settings. As all evaluated interventions combined primary and secondary prevention components, we were unable to determine the independent effects of primary preventive interventions. Classroom instruction and gatekeeper training increased short‐term suicide‐related knowledge. We found no studies that tested the effects of classroom instruction on suicidal behavior or long‐term outcomes. Limited evidence suggested minimal longer‐term effects of gatekeeper training on suicide‐related knowledge, while no evidence was found evaluating its effect on suicidal behavior. A policy‐based suicide intervention reduced student suicide, but findings have not been replicated. Our findings are limited by the overall low quality of the evidence and the lack of studies from middle‐ and low‐income countries. Rigorously designed studies should test the effects of preventive interventions on important health outcomes, including suicidal ideation and behavior, in varying post‐secondary settings.

Keywords: Humans; Education, Graduate; Suicidal Ideation; Suicide Prevention; Universities; Primary Prevention; Primary Prevention/methods; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Secondary Prevention

Plain language summary

Prevention of suicide in university and other post‐secondary educational settings

Review question

We reviewed evidence about the effect of suicide prevention programs on post‐secondary students who are not known to be suicidal. We examined the effects of these programs on suicide, suicidal behavior, and knowledge and attitudes about suicide.

Background

Worldwide, suicide is a leading cause of death among post‐secondary students. Suicidal thoughts and planning are common among such students. However, fewer than half of students who report suicidal thoughts or other serious mental illness have received professional treatment. There is a need for suicide prevention programs that target students who are not already known to be suicidal ("primary prevention").

Study characteristics

We identified eight studies that were eligible for this Cochrane Review. All studies had both primary and secondary prevention components. That is, they targeted students known to be suicidal as well as those not known to be suicidal. We separately analysed the effects of classroom instruction, institutional policies, and gatekeeper training programs. Gatekeeper training programs train people to recognize and respond to warning signs of emotional crises or suicide risk in students they encounter. The evidence is current to June 2011.

Key results

Three studies, including 312 students, evaluated classroom instruction. Classroom instruction increases short‐term knowledge of suicide and suicide prevention. It may slightly enhance short‐term confidence in ability to prevent suicide. However, long‐term effects have not been studied. Effects of classroom instruction on suicidal behavior have also not been studied. One study evaluated an institutional policy. The policy restricted access to laboratory cyanide and required professional assessment for students who threatened or attempted suicide. The policy significantly reduced student suicides. These findings have not been tested in other post‐secondary institutions. Four studies, ranging from 53 to 146 participants, evaluated the effect of gatekeeper training programs. Gatekeeper training may lead to small‐to‐medium improvements in short‐term suicide‐related knowledge and confidence about being able to prevent suicide. We found no evidence that gatekeeper training improved short‐term attitudes toward suicide or long‐term knowledge or behaviors about suicide. The effect of gatekeeper training on suicide or suicidal behavior has not been evaluated.

Quality of evidence

The quality of evidence for short‐term knowledge of suicide and suicide prevention was moderate. For suicide prevention self‐efficacy, the quality of evidence was low. The quality of evidence was reduced because results were not similar across studies and there were not enough data.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Summary of findings for classroom‐based instructional programs.

| What are the effects of classroom‐based instructional programs on suicidal behavior and ideation, knowledge of suicide and suicide prevention, and suicide prevention self‐efficacy? | ||||

|

Patient or population: Post‐secondary undergraduate students Settings: Large public universities located in medium‐sized cities Intervention: Experiential and didactic suicide prevention programs Comparison: Non‐suicide related material or no treatment | ||||

| Outcomes | SMD (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

| Completed suicide at the end of active intervention | N/A | N/A | N/A | No studies were found that evaluated the effect of intervention on completed suicide among students. |

| Suicidal ideation at the end of active intervention | N/A | N/A | N/A | No studies were found that evaluated the effect of intervention on suicidal ideation among students. |

| Attempted suicide at the end of active intervention | N/A | N/A | N/A | No studies were found that evaluated the effect of intervention on attempted suicide among students. |

| Knowledge of suicide at the end of active intervention | 1.51 (0.57 to 2.45) | 312 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | We downgraded the quality of evidence another level for unexplained, significant statistical heterogeneity, Chi2 = 22.60; P < 0.00001; I2 = 91%. We increased the quality of evidence by one level due to a large summary magnitude of effect. |

| Knowledge of suicide prevention at the end of active intervention | 0.72 (0.36 to 1.07) | 312 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | We observed moderate statistical heterogeneity between studies. |

| Suicide prevention self‐efficacy at the end of active intervention | 0.20 (‐0.13 to 0.54) | 152 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | We downgraded the quality of evidence by another level for imprecision. |

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||

1Quality of evidence downgraded by one level for unblinded outcome assessment.

Background

Description of the condition

Suicide is the deliberate act of taking one's own life. The World Health Organization (WHO) has reported that globally, suicide is the third leading cause of death among young people aged under 25 years (Wasserman 2010). Although data on suicide rates among students in post‐secondary education (i.e. enrolled in a university or other post‐secondary educational institution), hereafter referred to as 'student', are limited especially in low‐income countries, available statistics suggest that student suicide is an important cause of death worldwide. Incidences of 6.5, 8.2, and 10.0 per 100,000 full‐time students per year (or per academic year) have been reported in the United States, Great Britain, and China, respectively (Schwartz 2006; Universities UK 2002; Xiangmin 2009). The incidence in Finland is 13.8 and 9.0 per 100,000 per year for male and female students, respectively (Niemi 1993). These data indicate that student suicide is a significant mental and public health problem.

Risk factors for suicide include hopelessness, lack of social support, mental disorders (e.g. mood, anxiety, substance abuse) and a history of suicidal plans, ideation, and attempts (Arria 2009). Among people who have died by suicide, an estimated 90% had a known psychiatric disorder and 60% had a mood disorder (Sher 2001). Among students, academic problems may also increase risk of suicide (Bernard 1982; Schotte 1982). Annually among U.S. students, an estimated 11.4% have suicidal ideation, 8.3% make a suicidal plan, and 1.7% attempt suicide (Barrios 2000). The high prevalence of risk factors for suicide among post‐secondary students highlights the need for suicide prevention interventions in this setting.

Description of the intervention

Programs have been developed and implemented in the post‐secondary educational setting to reduce the rate of suicide and associated risk factors among students (Gould 2009). Primary prevention (i.e. intervention before suicidal behavior occurs, or ideation is expressed; SPAN 2001) within this setting may include a wide range of interventions, such as educational curricula, school policies (e.g. to increase access to mental health care, or restrict access to lethal means), peer organizational programs (e.g. training peers to recognize people at risk), screening programs to identify risk factors for suicide, and social norming programs (e.g. targeting perceptions of how common or how acceptable suicidal behavior is among students). Other primary prevention strategies may aim, either through campaigns or other means, to reduce taboos that isolate individuals who experience suicidal thoughts and behaviors and inhibit them from disclosing or seeking help.

Why it is important to do this review

Because suicide is a leading cause of student death, preventive measures are needed. Numerous reviews have previously examined diverse interventions aimed at symptomatic individuals (i.e. secondary prevention of suicide) (Crawford 2007; Hall 2002; Hawton 1999; Hepp 2004; Linehan 1997; Tarrier 2008; van der Sande 1997). However, fewer than half of students who report suicidal ideation or other serious mental health issues have received any professional services or treatment (Eisenberg 2012; Verger 2010; Schweitzer 1995) while Gallagher 2009 found that 80% of students that completed suicide had never participated in counseling services on campus. Therefore, secondary prevention within the post‐secondary school setting is limited by the failure to identify many students at risk of suicide. Primary prevention interventions, targeted to the general student population, have the potential to prevent suicide among students not previously identified. Furthermore, post‐secondary educational institutions comprise large populations of young adults who are relatively easy to access for program delivery, potentially increasing cost efficiency. Although primary prevention of suicide in the school setting has been reviewed previously, these reviews did not include (or did not identify) studies in post‐secondary educational settings (Guo 2002; Guo 2003; Harden 2001; Hider 1998; Katz 2013; Mann 2005; Miller 2009; Ploeg 1999). Students in post‐secondary educational settings encompass an age group that is distinct from younger students in terms of their development, demographics, subjective perceptions, identity explorations, and risk behaviors (Arnett 2000), while post‐secondary settings comprise a new and potentially stressful environment (Schwartz 1990). In this Cochrane Review we will address this gap in knowledge by assessing the available evidence to identify effective methods of primary suicide prevention within the post‐secondary educational setting.

Objectives

To evaluate primary suicide prevention interventions that targeted students within the post‐secondary setting to determine their effect on suicide and suicide‐related outcomes.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomized controlled trials (RCT): prospective studies that compare two or more groups, in which there is random assignment of participants or clusters to the interventions utilizing a known randomization or pseudo‐randomization technique (e.g. random numbers table, computer generated randomization, coin flip) or a statement that subjects were assigned randomly without explanation of how;

Controlled before‐and‐after (CBA) studies: studies that compare two or more groups to which participants are assigned by an entity other than themselves, and in which pre‐test and post‐test outcomes are measured concurrently and are available for both groups;

Controlled interrupted time series (CITS) design studies: studies in which there are at least three observations of the outcome measure both before and after a specific point in time when the intervention is implemented, from both the intervention group or area and concurrently at least one external comparison group or area, and in which an entity other than the participants determines which group or area receives the intervention;

Interrupted time series (ITS) design: studies in which there are at least three observations of the outcome measure both before and after a specific point in time when the intervention is implemented.

Types of participants

Students that attended a post‐secondary educational institution (e.g. college, university, community college, academy, or vocational or any other higher or post‐secondary educational institution) were a principal target of the intervention. We included studies that also targeted or collected data on faculty or staff in post‐secondary educational institutions as long as students were a principal target of the intervention. Students could be full‐time or part‐time, in any year of study, and live either on or off campus. We excluded individual apprenticeships unless they were part of matriculation in a vocational school. Also, we excluded studies solely targeting participants with a diagnosed mental health disorder or previous suicide attempt or self‐harm, or known suicidal ideation.

Types of interventions

We included any intervention that: a) targeted students without known suicidal risk (i.e. primary prevention), b) had the prevention of suicide as one of its primary purposes, and c) was delivered in the post‐secondary educational setting in any country. Examples of interventions included classroom‐based instructional programs, restricted access to lethal means (e.g. firearms), peer support programs, screening to identify suicide risk factors before development of suicidal ideation or behavior (e.g. substance abuse), and suicide awareness campaigns (CDC 1994). We excluded intervention programs that focused solely on early detection of suicidal ideation or planning and therapeutic interventions for known suicide risk, such as anti‐depressant medication (secondary prevention) and interventions to ameliorate the consequences of suicide attempts or other suicidal behavior (tertiary prevention) (SPAN 2001).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Our primary outcomes of interest were:

Completed suicide; and

Suicide attempt, which we defined as self‐injury with intent to die, as opposed to non‐suicidal self‐injury (Lloyd‐Richardson 2007).

We excluded assisted suicide because the type and focus of interventions for this outcome are likely to differ from those for non‐assisted suicide, and there is disagreement ‐‐ political, legal, and social ‐‐ about whether it is an appropriate prevention target.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes included suicidal ideation (i.e. thoughts, preparation, and planning), changes in knowledge and attitudes (e.g. knowledge of suicide or suicide prevention, suicide prevention self‐efficacy/self‐expectation, and attitudes toward suicide), changes in behavior including help‐seeking (e.g. use of mental health services) and helping others at risk (e.g. "gatekeeper" behavior), and lethal means availability.

When studies had multiple outcome measures of the same construct, we selected one outcome measure based on a predetermined hierarchy described elsewhere (Data extraction and management).

Search methods for identification of studies

In order to reduce publication and retrieval bias we did not restrict our search by language, date, or publication status.

Electronic searches

Using methods described elsewhere (Goss 2007), we developed a sensitive, database‐neutral search strategy to search electronic databases. We searched the following databases after adaptation of the free‐text search strategy to include subject headings (e.g. MeSH) specific to each database (Appendix 1):

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, The Cochrane Library) (Issue 2, July 2011);

Cochrane Injuries Group Specialised Register (18 July 2011);

Cochrane Depression, Anxiety & Neurosis Group Specialised Registers (25 July 2011);

MEDLINE (OvidSP) (1948 to 2011 June Week 4);

Embase (Elsevier) (pre‐1966 to July 2011);

CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature) (1960 to 12 July 2011);

PsycINFO (OvidSP) (1806 to 2011 June Week 4);

ISI Web of Science: Social Science Citation Index (SSCI) 1974 to 2011;

Dissertation Abstracts International (1816 to 2011);

ERIC (Education Resources Information Center) (pre‐1966 to 2011);

NIH RePORTER (Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tools Expenditures and Results) (projects still active as of 29 June 2011);

Suicide Information and Education Collection (SIEC) database (November 2011).

We limited the literature search of the Suicide Information and Education Collection (SIEC) database to studies of suicide and suicidal behaviors, searching initially for any suicide interventions, then within this subset using terms such as post‐secondary, college, university, and higher education.

We used lateral search functions such as "related articles" or "cited by" for each included study.

Searching other resources

We reviewed bibliographies of all included studies to identify additional relevant citations. We also handsearched the following journals from 1970 (or initial publication, as shown) through 2008:

Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica;

Archives of General Psychiatry;

British Journal of Psychiatry;

Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention (2005‐);

JAMA‐Journal of the American Medical Association;

Journal of American College Health (1982‐);

Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology;

Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry;

Psychological Reports;

Suicide and Life‐Threatening Behavior (1971‐).

Although some of these journals are already being handsearched by Cochrane groups, our broader inclusion criteria for study design necessitated additional handsearching.

We sought gray literature (Conn 2003) through electronic databases, as listed above, by contacting study authors, and by screening reference lists of included studies. We also contacted or searched electronic resources (e.g. websites) of the following organizations:

American Association of Suicidology;

American Foundation for Suicide Prevention;

Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet;

Australian Institute for Suicide Research and Prevention;

Beijing Suicide Research and Prevention Center;

Centre for Suicide Research (Denmark);

European Network for Suicidology;

International Association for Suicide Prevention;

Menzies School of Health Research (Australia);

National Prevention of Suicide and Mental Ill‐Health (Karolinska Institutet, Sweden);

National Centre for Suicide Research and Prevention (University of Oslo, Norway);

University of Oxford Centre for Suicide Research (United Kingdom);

World Health Organization (SUPRE).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (CH, CG or VT) independently screened titles and abstracts using selection criteria for eligible study designs, participants, and interventions. We obtained the full‐text articles of studies that met inclusion criteria or that both review authors could not definitely exclude. If eligibility remained unclear after full‐text review, we contacted the study authors for clarification. If an otherwise eligible study did not report collecting eligible outcome measures, we asked the study author to provide any unpublished outcomes data. If the two review authors were unable to agree about study eligibility after full‐text review and discussion, a third review author (CD) reviewed the full‐text to determine eligibility. We recorded and managed individual study information, including year, design, intervention type and population, using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) electronic data capture tools hosted at University of Colorado Denver (Harris 2009). REDCap is a secure, web‐based application designed to support data capture for research studies, providing an intuitive interface for validated data entry; audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures; automated export procedures for seamless data downloads to common statistical packages; and procedures for importing data from external sources (Harris 2009).

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (CH and CG) independently extracted information on study design, intervention type and characteristics, participants, setting, methods, outcomes, and results from all eligible studies and managed this data using Microsoft Excel. We contacted study authors for missing information. CH entered data into Review Manager and CG reviewed data entry for accuracy and completeness. If disagreement persisted following discussion, CD made a final determination.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

CH and CG independently assessed risk of bias using criteria developed by the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) review group (EPOC 2009). If the two review authors disagreed, a third review author (CD) resolved the dispute. We assigned each methodological quality criterion one of the following ratings: low risk, unclear risk, or high risk. Operational definitions of these methodological quality criteria ratings vary by the specific quality criteria. How these ratings are defined for each criterion can be found elsewhere (EPOC 2009).

The criteria to determine the methodological quality of RCTs and CBAs were as follows:

Adequacy of sequence generation;

Allocation concealment;

Completeness of outcome data;

Participant blinding;

Selective outcome reporting;

Other potential internal and external threats to validity.

The criteria to determine the methodological quality of CITS and ITS are described elsewhere (EPOC 2009).

To summarize the quality of evidence, we used the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach. CH and CG independently assessed the evidence of outcomes across included studies. CD resolved disputes. We used the GRADE criteria for increasing or downgrading the quality level of the body of evidence for each outcome in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008) and the McMaster (http://cebgrade.mcmaster.ca/) GRADE learning modules. We only applied the GRADE approach to evidence from RCTs, in which outcomes were meta‐analysed. We summarized the quality of evidence from non‐randomized studies narratively.

We used the following operational criteria for downgrading ratings based on heterogeneity and imprecision and upgrading ratings due to large magnitude of effect. We downgraded quality grades by one level if there was significant heterogeneity (i.e. I2 statistic ≥ 50% with P < 0.10 using the Chi2 test) between studies that could not be explained by such factors as subgroup analyses. Following recommendations by McMaster, we downgraded quality ratings by one level if an SMD 95% confidence interval (CI) contained both 0.0 (i.e. no effect) and 0.50, which we considered to be a meaningful effect. Using Cohen 1988's guidelines for interpreting SMD, we increased quality ratings by one level based on a large magnitude of effect if the SMD > 0.80.

For RCTs, we assigned the body of evidence for each outcome one of the following quality ratings, or N/A if no evidence was available:

High: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect;

Moderate: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate;

Low: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate;

Very low: we are very uncertain about the estimate.

Measures of treatment effect

We extracted and analysed dichotomous and continuous outcomes. Continuous data were analysed with means and standard deviations (SD) where available or as calculated using other estimates (e.g. from t‐tests, F‐tests, or exact P values). As the included studies used different scales, we estimated standardized mean difference (SMD) values using Review Manager's formula based on Hedges' g which adjusts for small sample bias. We used 95% CIs for individual study and summary estimates. For dichotomous outcomes, we converted odds ratios to SMD using the Cox logit formula (Sánchez‐Meca 2003).

Unit of analysis issues

For clustered studies with unit of analysis issues (Drabek 1991; Holdwick 2000; Tompkins 2009), we extracted data on sample size, average cluster size, and SDs by intervention group. We then corrected the group SDs for clustering using a published interclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.07 (Jacobson 2011).

Dealing with missing data

We asked study authors to provide any missing summary data, or failing that, data to derive the required summary data. If they were unable to provide this, we attempted to derive the data from other reported study statistics. If we could not obtain or derive the data, we analysed the study narratively.

Where included studies did not state that results were reported using an intention‐to‐treat analysis for primary outcomes, we contacted study authors to request the necessary data. In the event of non‐response, we analysed results as reported.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We analysed statistical heterogeneity using the Chi2 test and I2 statistic (Higgins 2003). As detection of heterogeneity has low power with a small numbers of studies, we used an alpha of P ≤ 0.10 (Dickersin 1992). We considered statistical heterogeneity to be significant if the I2 statistic was ≥ 50% with a P value < 0.10, and moderate if only one of the two criteria was met. We also examined study participants, interventions (within broadly categorized types – see Data synthesis below), and outcomes for evidence of clinical heterogeneity (i.e. variability across studies in participants, interventions, or outcomes studied (Section 9.5.1 of Higgins 2008)). We described these characteristics in the Characteristics of included studies tables. We examined clinical variations in subgroup and sensitivity analyses.

Assessment of reporting biases

To reduce reporting bias, we searched for studies without publication or language restrictions, and asked the authors of included studies for any data collected but not reported. Given the small number of included studies, we did not use funnel plots to assess bias.

Data synthesis

We grouped studies according to intervention type and study design (randomized or not). All comparisons were between intervention and control groups (placebo or no intervention). We considered both statistical and clinical heterogeneity within each intervention type.

For each outcome we calculated weighted means and SDs. For main analyses, we combined multiple different intervention groups in two RCTs (Abbey 1990; Holdwick 2000) and, in one CBA (Shipley 2003), combined results from two groups that received the same (mandatory) intervention but had been divided for reporting purposes into "voluntary" and "involuntary" participants based on reported likelihood at baseline of voluntary participation in gatekeeper training. One RCT (Abbey 1989) provided combined means and SDs for two intervention groups, and we analysed the data as such. Where appropriate data were available, we conducted sensitivity analyses comparing controls to each different intervention group in two RCTs (Abbey 1990; Holdwick 2000) and to the "voluntary" and "involuntary" groups separately in one CBA (Shipley 2003).

One CBA (Pasco 2012) created and used the Suicide Intervention Training Assessment (SITA), a 14‐item instrument that measures self‐efficacy, reported as 14 individual results. As the items were directionally and conceptually similar, we calculated overall weighted mean estimates and pooled SDs for SITA results for both intervention and control groups.

In one RCT (Abbey 1989), we used the reported t‐statistics and group means and sample sizes to calculate intervention and control group SDs for two outcomes measured by the Knowledge of Suicide Test (KOST) and Suicide Intervention Response Inventory (SIRI), assuming equality of variances between groups. Because the KOST was also used in a subsequent RCT with a similar intervention and student population (Abbey 1990), we pooled the SDs.

Using an average cluster size extracted from the respective included study and ICC = 0.07 (Jacobson 2011), we corrected group SDs of clustered studies that had not accounted for clustering, and re‐analysed the data.

For one CBA (Shipley 2003) that used a binary measure of "knowledge of suicide", we converted the odds ratio to SMD using the Cox logit formula (Sánchez‐Meca 2003). The original pre‐ and post‐test results (odds ratios) are displayed in a Forest plot. The converted results are described in the text.

Among three CBAs that implemented a delayed intervention control group (Drabek 1991; Pasco 2012; Tompkins 2009), we only extracted and analysed control group data collected concurrently with post‐test measures for the intervention groups, before the controls received the intervention.

We calculated SMD values for all analyses because of the heterogeneous scales used to measure each construct. Where the direction of a scale was dissimilar from other measures, i.e. a decrease indicated improved outcome (Scale 3 ‐ Suicide and Suicide Prevention Questionnaire (SSPQ) (Holdwick 2000), Suicide Opinion Questionnaire – Acceptability Factor (SOQ‐AF) (Drabek 1991), and SIRI‐2 (Pasco 2012)), we multiplied the mean values of intervention and control groups by ‐1. We did not modify group SDs.

For RCT studies, we conducted random‐effects model meta‐analyses using inverse variance techniques to estimate SMD at post‐test between intervention and control groups.

For CBA studies, we reported individual study effect sizes without summary estimates. Insufficient data were provided to calculate mean change score SDs and correlation coefficients for intervention and control groups. As a result, we calculated SMD and 95% CIs based on post‐test results only. This approach may bias SMD as participants were not randomly allocated to intervention and control groups; however, analysis comparing baseline measures between intervention and control groups revealed no statistically significant differences.

We performed analyses in Review Manager and used an alpha value of 0.05 for statistical significance throughout this review.

We used Cohen's guidelines for interpreting SMD (small = 0.20; medium = 0.50; and large = 0.80) (Cohen 1988). For our review, an SMD of zero translates to there being no evidence of an effect from the suicide prevention intervention relative to the comparison group. The higher the SMD, the more efficacious is the intervention in enhancing the respective outcome. A negative SMD means that the suicide prevention intervention had a negative effect on the outcome relative to the comparison group (Faraone 2008). Post‐test comparisons of suicide‐related outcomes immediately following active intervention are considered "short‐term". If a later follow‐up evaluation occurred, the findings are considered "longer‐term".

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Due to a lack of data on demographics, housing status (i.e. whether living on or off campus), and student workload (full vs. part‐time) and lacked study heterogeneity for level of study and institution type, we were unable to conduct subgroup analyses for relevant outcomes using random‐effects models (Borenstein 2009) as proposed. Although we proposed a subgroup analysis involving attrition (follow‐up > 80% vs. < 80%), no RCT had follow‐up < 80%. In a post hoc exploration of heterogeneity among studies of classroom instructional programs, we examined subgroups according to outcome measure used.

Sensitivity analysis

Although we proposed sensitivity analyses based on allocation concealment and randomization sequence generation, these quality parameters were similar across the three RCT studies we included in meta‐analyses. In post‐hoc sensitivity analyses, we tested the influence on suicide‐related outcomes of differing intervention groups and 'voluntary' versus 'involuntary' participant groups.

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies tables.

We included eight eligible studies in this review and identified one ongoing study that met our inclusion criteria (5R01MH083740).

Results of the search

See Figure 1.

1.

PRISMA study flow diagram.

This review fully incorporates the results of searches conducted up to November 2011. We identified a further 13 documents in a search update we conducted in November 2013. However, we have not yet incorporated these into the review and will be addressed in the next review update. See Studies awaiting classification for details.

Our electronic search strategy yielded 49,503 records (CENTRAL = 775; CINAHL = 2182; Cochrane Injuries Group Specialised Register = 21; Dissertation Abstracts International = 1283; EMBASE = 9490; ERIC = 2482; MEDLINE = 12,670; NIH RePORTER = 195; PsycINFO = 12,057; SSCI = 7674; Cochrane Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Group Specialised Register = 469 and SIEC = 205). Using forward, backward and lateral search functions on eligible studies, and screening reference lists of potentially eligible studies, we identified 47 additional records. Screening websites of national and international organizations and agencies (Searching other resources), and conference proceedings revealed no additional studies. Of 27,449 unique records, we deemed 290 potentially eligible. We examined 287 full‐text documents; we could not find the full‐text of three records and we excluded these records based on available information. Nine studies, including one ongoing study (5R01MH083740), were eligible. Also, we identified one of the nine studies (Pasco 2012) through author contact after the electronic search date. The authors of all but one study (Drabek 1991) provided additional information or data.

Included studies

We included eight completed studies: four published journal articles (Abbey 1989; Joffe 2008; Pasco 2012; Tompkins 2009) and four dissertations (Abbey 1990; Drabek 1991; Holdwick 2000; Shipley 2003). All contributed analysable outcome data. The three RCTs randomized a total of 312 students to relevant study arms. We have listed the details of the included studies in the Characteristics of included studies section.

Study designs

The eight included studies consisted of three RCTs (Abbey 1989; Abbey 1990; Holdwick 2000) and five CBAs (Drabek 1991; Joffe 2008; Pasco 2012; Shipley 2003; Tompkins 2009). Our searches did not yield any CITS or ITS studies. One RCT (Holdwick 2000) and one CBA (Drabek 1991) allocated participants by session date, and another CBA examined institutions that did and did not receive the experimental intervention (Tompkins 2009). One CBA (Joffe 2008) examined outcomes in twelve universities that were similar in location, size, and educational mission before (1975 to 1983) and after (1984 to 2004) one of the universities implemented the intervention.

Settings and populations

One study (Shipley 2003) was set in Australia and all others took place in the United States. All studies involved four‐year degree granting colleges or universities. Study participants included students enrolled in a psychology course (Abbey 1989; Abbey 1990; Holdwick 2000; Joffe 2008; Shipley 2003), peer advisors (i.e. students, generally in their third or fourth year at university, that reside and oversee peers within university student accommodation, plan social activities, and may serve as a mediator to interpersonal conflict or offer counsel to students dealing with personal issues) (Pasco 2012; Tompkins 2009), and faculty and staff (Drabek 1991).

Interventions

All interventions included both primary and secondary suicide prevention components. The three RCTs evaluated one to four week classroom‐based instruction involving suicide‐related lectures and handouts (Abbey 1989; Abbey 1990; Holdwick 2000). One RCT also included suicide vignettes (Abbey 1989) and another featured modeling and role‐play (Abbey 1990). Primary prevention components included empathetic listening, lethal means restriction (e.g. firearms), and prevention of risk factors for suicide (e.g. substance abuse). Secondary prevention components included instruction on intervening with suicidal peers and enhancing self help‐seeking if suicidal. One CBA (Joffe 2008) evaluated an institutional policy restricting access to laboratory cyanide (primary prevention) and mandating four professional assessment sessions for students threatening or exhibiting suicidal behavior (secondary prevention). The other four CBAs examined training "gatekeepers" ‐ those who are strategically positioned to recognize and refer students at risk for suicidal ideation or behavior‐ including fellow students (Shipley 2003), faculty and staff (Drabek 1991), and peer advisors (Pasco 2012; Tompkins 2009). The gatekeeper is trained to ask the student with suicide warning signs about the presence of suicidal thoughts and feelings, encourage them to seek help, and refer them to local resources to obtain needed help. Programs included Campus Connect training for peer advisors (Pasco 2012), "Question, Persuade, and Refer" training for students (Shipley 2003) and peer advisors (Tompkins 2009), respectively, and an experiential and didactic training program for faculty and staff (Drabek 1991). Gatekeeper training programs comprised one session lasting from one to three hours and generally including training in active listening (primary prevention) and in self‐efficacy and skills for responding to emotional distress or crisis (primary prevention) and suicidal threats or behavior (secondary prevention), as well as information on local mental health and crisis services.

Outcomes

Following data extraction, CH, CG, CD, and Dr. Jeffrey Gliner (see Acknowledgements) independently generated an outcome construct categorization scheme. We agreed final categorization through discussion and consensus, and measured six constructs in the included studies:

Completed suicide;

Knowledge of suicide;

Knowledge of suicide prevention;

Suicide prevention self‐efficacy;

Attitudes toward suicide;

Gatekeeper behavior.

Gochman 1997 describes self‐efficacy as a main determinant of behavioral self‐prediction (i.e. "I will perform this action"). Self‐expectation is interpreted as an individual's estimated likelihood of performing specific future behaviors. Despite the slight difference in definition, we combined self‐expectation with self‐efficacy for analytic purposes. No included studies evaluated intervention effects on suicide attempts or threats, suicidal ideation, help‐seeking behavior, or lethal means availability.

When studies collected and provided adequate data for multiple measures of primary or secondary outcomes of interest, we selected only one of those measures for analysis based on the following predetermined hierarchy applied independently by two review authors (CH and CG). We abstracted or determined study information for the hierarchy criteria through the index study or other documents, such as a validation study, by two review authors independently (CH and CG). We resolved any disagreements by discussion and referral to a third review author (CD) if necessary. We applied the following hierarchy to each measure with sufficient data for meta‐analysis:

Validity (i.e. degree to which an instrument measures what it intends to measure – operationalized as measures of construct, content, or face validity (Sushil 2010));

Specificity (i.e. extent to which the instrument only measures the construct of interest);

Reliability (i.e. repeatability and consistency);

Completeness of data (e.g. percent of missing data);

Objectivity (e.g. observed by study personnel) versus subjectivity (e.g. self‐reported);

Frequency of implementation within the included studies (i.e. of two equivalent measures, the one more frequently used);

Similarity of content between instruments (i.e. the most relevant outcome construct as determined by review authors; if review authors disagreed, we implemented the next level of the hierarchy);

Random selection if measures were still equivalent after steps 1 to 7.

After application of the hierarchy, we selected the following outcome measures with associated instruments and used them in this review:

Knowledge of suicide:

KOST (Abbey 1989);

KOST (Abbey 1990);

Recognition of Suicide Lethality Scale (RSL) (Drabek 1991);

Suicide Information Test (SIT) (Holdwick 2000);

Mental Health Literacy Scale 1‐item Questionnaire (Shipley 2003).

Knowledge of suicide prevention:

SIRI (Abbey 1989);

Suicide‐Related Vignette Questionnaire (Abbey 1990);

Assessment of Appropriate Responses Scale (AARS) (Drabek 1991);

Scale 2 ‐ SSPQ (Holdwick 2000);

SIRI‐2 (Pasco 2012);

Mental Health Literacy Scale 4‐item Questionnaire (Shipley 2003);

-

Question, Persuade, and Refer Quiz (Tompkins 2009)

Self‐evaluation of knowledge item.

Suicide prevention self‐efficacy:

Scale 3 ‐ SSPQ (Holdwick 2000);

SITA (Pasco 2012);

Generalized Self‐Efficacy Scale (Shipley 2003);

-

Question, Persuade, and Refer Quiz (Tompkins 2009)

Gatekeeper efficacy item.

Attitudes toward suicide:

SOQ‐AF (Drabek 1991);

Attitude Scale 8‐item Questionnaire (Shipley 2003).

Gatekeeper behaviors:

-

Question, Persuade, and Refer Quiz (Tompkins 2009);

Question, Persuade, and Refer behaviors item.

One study measured completed suicide (Joffe 2008).

Excluded studies

Of 290 potentially eligible studies, we excluded 282 studies. We have listed the reasons for exclusion of a small sample of these studies, representing our general reasoning for exclusion (see Characteristics of excluded studies).

Risk of bias in included studies

We successfully contacted authors of all but one included study (Drabek 1991) to obtain complete information on risk of bias. Nevertheless, some risk of bias criteria remained unclear because insufficient information was obtained.

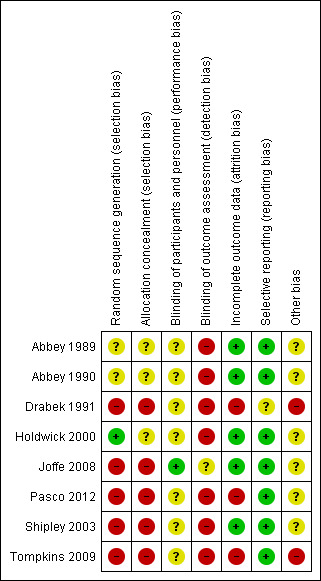

Figure 2 shows a summary of the aggregate and Figure 3 the individual risk of bias criteria and their ratings. We have given detailed descriptions of these assessments in the Characteristics of included studies table.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

One clustered RCT (Holdwick 2000) was rated at low risk of selection bias based on random sequence generation. The other two RCTs (Abbey 1989; Abbey 1990) were unclear. Allocation concealment was unclear due to insufficient information in all three RCTs. Random sequence generation and allocation concealment for non‐randomized studies (Drabek 1991; Joffe 2008; Pasco 2012; Shipley 2003; Tompkins 2009) were deemed at high risk of selection bias.

Blinding

In seven studies, the risk of performance bias based on blinding of participants and personnel was unclear due to insufficient information and the risk of detection bias was high because appropriate blinding of outcome assessment was not implemented. However, participant blinding in classroom instruction and gatekeeper training interventions may not be possible. In the remaining CBA (Joffe 2008), the risk of performance bias was low because the outcome (i.e. suicide) was unlikely to be influenced by a lack of blinding and the potential for detection bias in this study was unclear.

Blinding was attempted in two studies, but deemed insufficient. In a clustered RCT (Holdwick 2000), participants and study personnel were blinded to the research hypotheses but the data assessors were not. In a CBA (Pasco 2012), participants were blinded to research hypotheses but study personnel and data assessors were not.

Incomplete outcome data

All three RCTs were judged to be at low risk of bias as outcomes data were missing for 0% (Abbey 1989), 3% (Abbey 1990), and < 10% (Holdwick 2000) of participants, respectively. Three CBAs (Drabek 1991; Pasco 2012; Tompkins 2009) were at high risk of attrition bias: outcomes data were missing for 23% to 25% (Pasco 2012) and 26% (Drabek 1991) of participants, respectively, in two studies, while the third CBA (Tompkins 2009) purposely reduced the control sample for follow‐up evaluation to alleviate burden on subjects, resulting in 39% missing outcome data. Two CBA studies were at low risk of bias: Joffe 2008 measured the cumulative incidence of student suicide as a primary outcome, while Shipley 2003 had between 1.4% and 2.9% missing outcome data for three outcomes, and 15.9% for another.

Selective reporting

Seven studies were at low risk of reporting bias. Although none had protocols available for review, each study author confirmed that the published report had all expected outcomes, including those that were pre‐specified. We were unable to contact the investigators of one CBA (Drabek 1991) to confirm pre‐specified outcomes, rendering a judgement of unclear risk of bias.

Other potential sources of bias

Three RCTs had no other biases noted. In one clustered CBA (Tompkins 2009), administrators of each institution selected their own group assignment. This may bias the study if differences in suicide‐related factors between campuses influenced choice of study group. This is also a potential concern in Drabek 1991, where investigators allocated participants to intervention or control groups based on session date, after participants chose which session to attend. However, in neither instance did the participants themselves select their group assignment. In another CBA (Joffe 2008), an intervention to enhance help‐seeking behavior was implemented for a three‐month period before the index suicide‐related institutional policy was implemented. Although the study authors concluded it did not increase the number of contacts with social workers or psychologists, it is unclear how it may have influenced the results. One clustered CBA (Tompkins 2009) showed that baseline knowledge of suicide resources was greater among control compared to treatment participants, and different testing formats between the groups were used during the post‐test phase. Another CBA (Shipley 2003) had different source populations for intervention and control groups, resulting in significant differences in age, gender and ethnicity between groups.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

We analysed the effects of intervention stratified by intervention type and whether randomized or not. All comparisons were between intervention and placebo or no intervention control groups. We meta‐analysed results from three RCTs testing classroom‐based instruction (Abbey 1989; Abbey 1990; Holdwick 2000) and analysed five CBA studies narratively.

Using available data (Methods ‐ Data synthesis), in one RCT (Abbey 1989), we calculated intervention and control group SDs for two outcomes, knowledge of suicide (measured by the KOST) and knowledge of suicide prevention (measured by the SIRI). More conservative pooled SDs were used for the main analysis (Analysis 1.1), since sensitivity analysis (Analysis 5.1) revealed that the statistical significance of the test for knowledge of suicide did not differ using assumed equality of variance between intervention and control groups as compared to using the estimated pooled SDs between the two similar studies.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Classroom instruction: knowledge of suicide, Outcome 1 Post‐test differences in knowledge of suicide at the end of active intervention.

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Sensitivity analyses for classroom instruction: knowledge of suicide, Outcome 1 Sensitivity analysis (Abbey 1989, KOST ‐ equality of variance): post‐test differences in knowledge of suicide at the end of active intervention.

Classroom‐based instructional programs

Knowledge of suicide

Classroom instruction greatly increased short‐term knowledge of suicide in three RCTs (SMD = 1.51, 95% CI 0.57 to 2.45) with significant quantitative heterogeneity (Chi2 = 22.60; P < 0.00001; I2 = 91%; Analysis 1.1). Sensitivity analyses comparing experiential and didactic suicide prevention programs (Abbey 1990) respectively, to controls, revealed a slightly greater effect from didactic education (SMD = 1.74, 95% CI 0.56 to 2.93; Analysis 5.3) compared to experiential intervention (SMD = 1.35, 95% CI 0.41 to 2.28; Analysis 5.2). A direct comparison between the two intervention groups suggested that didactic intervention significantly enhanced short‐term knowledge of suicide relative to experiential (Analysis 4.1). Additional sensitivity analyses comparing each of two different intervention groups, an education‐based suicide prevention program (EB‐SP) and a motivational‐enhancement suicide prevention program (ME‐SP) (Holdwick 2000), respectively, to controls, revealed no statistically significant differences, with SMD = 1.50 (95% CI 0.55 to 2.46, Analysis 5.4) and SMD = 1.54 (95% CI 0.64 to 2.43, Analysis 5.5) for the two interventions, respectively. Post‐hoc exclusion of Holdwick 2000, which used a different outcome measure than did the other two RCTs, reduced but did not eliminate statistical heterogeneity (Chi2 test = 4.44; P = 0.04; I2 statistic = 77%; Analysis 5.6).

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Sensitivity analyses for classroom instruction: knowledge of suicide, Outcome 3 Sensitivity analysis (Abbey 1990, lecture and handouts vs. control): post‐test differences in knowledge of suicide at the end of active intervention.

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Sensitivity analyses for classroom instruction: knowledge of suicide, Outcome 2 Sensitivity analysis (Abbey 1990, modeling and role play vs. control): post‐test differences in knowledge of suicide at the end of active intervention.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Experimental group comparison for classroom instruction: post‐test differences at the end of active intervention, Outcome 1 Abbey 1990, lecture and handouts vs. modeling and role play: post‐test differences in knowledge of suicide at the end of active intervention.

5.4. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Sensitivity analyses for classroom instruction: knowledge of suicide, Outcome 4 Sensitivity analysis (Holdwick 2000, education‐based suicide prevention program vs. control): post‐test differences in knowledge of suicide at the end of active intervention.

5.5. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Sensitivity analyses for classroom instruction: knowledge of suicide, Outcome 5 Sensitivity analysis (Holdwick 2000, motivational‐enhancement suicide prevention program vs. control): post‐test differences in knowledge of suicide at the end of active intervention.

5.6. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Sensitivity analyses for classroom instruction: knowledge of suicide, Outcome 6 Post‐hoc sensitivity analysis (exclusion of Holdwick 2000): assessment of statistical heterogeneity.

Knowledge of suicide prevention

In three RCTs, classroom instruction increased short‐term knowledge of suicide prevention (SMD = 0.72, 95% CI 0.36 to 1.07) with moderate statistical heterogeneity (Chi2 test = 3.98; P = 0.14; I2 statistic = 50%; Analysis 2.1). Sensitivity analyses comparing experiential and didactic suicide prevention programs (Abbey 1990), respectively, to controls, revealed no differences in effect or significance, with SMD = 0.70 (95% CI 0.35 to 1.06; Analysis 6.1) and SMD = 0.72 (95% CI 0.35 to 1.10; Analysis 6.2) for the two interventions, respectively. Furthermore, comparing the education‐based suicide prevention program and the motivational‐enhancement suicide prevention program (Holdwick 2000), respectively, to controls revealed no differences in effect or significance, with SMD = 0.71 (95% CI 0.33 to 1.10; Analysis 6.3) and SMD = 0.75 (95% CI 0.45 to 1.04; Analysis 6.4), respectively. Post‐hoc exclusion of Holdwick 2000 eliminated heterogeneity (Chi2 = 0.01; P = 0.94; I2 = 0%) (Analysis 6.5).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Classroom instruction: knowledge of suicide prevention, Outcome 1 Post‐test differences in knowledge of suicide prevention at the end of active intervention.

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Sensitivity analyses for classroom instruction: knowledge of suicide prevention, Outcome 1 Sensitivity analysis (Abbey 1990, modeling and role play vs. control): post‐test differences in knowledge of suicide prevention at the end of active intervention.

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Sensitivity analyses for classroom instruction: knowledge of suicide prevention, Outcome 2 Sensitivity analysis (Abbey 1990, lectures and handouts vs. control): post‐test differences in knowledge of suicide prevention at the end of active intervention.

6.3. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Sensitivity analyses for classroom instruction: knowledge of suicide prevention, Outcome 3 Sensitivity analysis (Holdwick 2000, education‐based suicide prevention program vs. control): post‐test differences in knowledge of suicide prevention at the end of active intervention.

6.4. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Sensitivity analyses for classroom instruction: knowledge of suicide prevention, Outcome 4 Sensitivity analysis (Holdwick 2000, motivational‐enhancement suicide prevention program vs. control): post‐test differences in knowledge of suicide prevention at the end of active intervention.

6.5. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Sensitivity analyses for classroom instruction: knowledge of suicide prevention, Outcome 5 Post‐hoc sensitivity analysis (exclusion of Holdwick 2000): assessment of statistical heterogeneity.

Suicide prevention self‐efficacy

One RCT (Holdwick 2000) demonstrated a small, non‐significant increase in short‐term suicide prevention self‐efficacy among students who received the education‐based or motivational‐enhancement suicide prevention program compared to control students (SMD = 0.20, 95% CI ‐0.13 to 0.54; Analysis 3.1). Sensitivity analyses comparing education‐based suicide prevention programs and motivational‐enhancement suicide prevention programs to controls a somewhat greater effect size from the motivational‐enhancement suicide prevention program (SMD = 0.30, 95% CI ‐0.09 to 0.69; Analysis 7.2) than from the education‐based suicide prevention program (SMD = 0.09, 95% CI ‐0.30 to 0.48; Analysis 7.1), but effects did not differ significantly when the experimental groups were directly compared (Analysis 4.2).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Classroom instruction: suicide prevention self‐efficacy, Outcome 1 Post‐test differences in suicide prevention self‐efficacy at the end of active intervention.

7.2. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Sensitivity analysis for classroom instruction: suicide prevention self‐efficacy, Outcome 2 Sensitivity analysis (Holdwick 2000, motivational‐enhancement suicide prevention program vs. control): post‐test differences in self‐efficacy at the end of active intervention.

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Sensitivity analysis for classroom instruction: suicide prevention self‐efficacy, Outcome 1 Sensitivity analysis (Holdwick 2000, education‐based suicide prevention program vs. control): post‐test differences in self‐efficacy at the end of active intervention.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Experimental group comparison for classroom instruction: post‐test differences at the end of active intervention, Outcome 2 Holdwick 2000, motivational‐enhancement suicide prevention program vs. education based‐suicide prevention program: post‐test differences in self‐efficacy at the end of active intervention.

Policy‐based interventions

Completed suicide

One Midwestern US university implemented a multi‐component policy intervention involving means restriction and mandatory assessment for suicidal behavior (Joffe 2008). Before policy implementation (1980 to 1983), no evidence of a difference in the cumulative incidence of suicide was detected between the intervention institution and 11 comparable control institutions, 7.89 vs. 7.07 per 100,000 (Z = 0.33; P > 0.05). Afterward (1984 to 1990), the cumulative incidence of suicide was significantly lower at the intervention university relative to control universities, 2.00 vs. 8.68 per 100,000 (Z = 5.90; P < 0.05). Additionally, the cumulative incidence of student suicide was significantly lower at the intervention institution following implementation (2.00 (after) vs. 7.89 (before) per 100,000; Z = 2.32; P < 0.05), whereas the control institutions showed no evidence of a reduction (8.68 (after) vs. 7.07 (before) per 100,000; Z = 1.57; P > 0.05).

Gatekeeper training programs

There was no evidence of differences in suicide‐related baseline measures between intervention and control groups (Analysis 8.1; Analysis 8.2; Analysis 8.3; Analysis 8.4; Analysis 8.5; Analysis 8.6). Also, no statistically significant differences were found in suicide‐related baseline measures of "voluntary" versus "involuntary" student participants (designated according to baseline self‐reported motivation to participate, though all the students were required to participate) in a Question, Persuade, and Refer workshop (Shipley 2003) (Analysis 10.1; Analysis 10.2; Analysis 10.3; Analysis 10.4). Post‐test comparisons of the effects of gatekeeper interventions are described below.

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Gatekeeper training programs: baseline measures of suicide‐related outcomes, Outcome 1 Baseline measures of knowledge of suicide (continuous).

8.2. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Gatekeeper training programs: baseline measures of suicide‐related outcomes, Outcome 2 Baseline measures of knowledge of suicide (dichotomous).

8.3. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Gatekeeper training programs: baseline measures of suicide‐related outcomes, Outcome 3 Baseline measures of knowledge of suicide prevention.

8.4. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Gatekeeper training programs: baseline measures of suicide‐related outcomes, Outcome 4 Baseline measures of suicide prevention self‐efficacy.

8.5. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Gatekeeper training programs: baseline measures of suicide‐related outcomes, Outcome 5 Baseline measures of attitudes toward suicide.

8.6. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Gatekeeper training programs: baseline measures of suicide‐related outcomes, Outcome 6 Baseline measures of gatekeeper behaviors.

10.1. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Experimental group comparisons, gatekeeper training programs: baseline measures of suicide‐related outcomes, Outcome 1 Baseline measures of knowledge of suicide (Shipley 2003 ‐ dichotomous).

10.2. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Experimental group comparisons, gatekeeper training programs: baseline measures of suicide‐related outcomes, Outcome 2 Baseline measures of knowledge of suicide prevention (Shipley 2003).

10.3. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Experimental group comparisons, gatekeeper training programs: baseline measures of suicide‐related outcomes, Outcome 3 Baseline measures of suicide prevention self‐efficacy (Shipley 2003).

10.4. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Experimental group comparisons, gatekeeper training programs: baseline measures of suicide‐related outcomes, Outcome 4 Baseline measures of attitudes toward suicide (Shipley 2003).

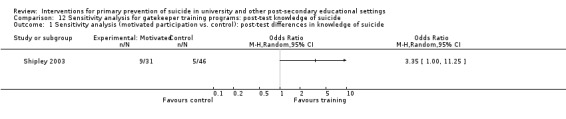

Knowledge of suicide

A gatekeeper training program (Drabek 1991) featuring experiential and didactic components administered to faculty and staff increased short‐term knowledge of suicide relative to no training (SMD = 0.86, 95% CI 0.28 to 1.44; Analysis 9.1). A two to three hour gatekeeper workshop delivered to students (Shipley 2003) also suggested an increase in short‐term knowledge of suicide among trained students relative to those who did not receive training (SMD = 0.63, 95% CI ‐0.02 to 1.28; original result: OR = 2.84, 95% CI 0.97 to 8.29); however, this finding was not statistically significant (Analysis 9.2). Sensitivity analyses revealed that when compared to students who received no training, students who expressed motivation to volunteer for the Question, Persuade, and Refer workshop had greater increases in short‐term knowledge of suicide (SMD = 0.73, 95% CI 0.001 to 1.47; original result: OR = 3.35, 95% CI 1.00 to 11.25; Analysis 12.1) than did those who did not express motivation to volunteer (SMD = 0.55, 95% CI ‐0.18 to 1.27; original result: OR = 2.46, 0.75 to 8.09; Analysis 12.2). However, a direct comparison between 'voluntary' and 'involuntary' participants showed no statistically significant difference in post‐test outcome (Analysis 11.1).

9.1. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Gatekeeper training programs: post‐test measures of suicide‐related outcomes, Outcome 1 Post‐test differences in knowledge of suicide (continuous).

9.2. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Gatekeeper training programs: post‐test measures of suicide‐related outcomes, Outcome 2 Post‐test differences in knowledge of suicide (dichotomous).

12.1. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Sensitivity analysis for gatekeeper training programs: post‐test knowledge of suicide, Outcome 1 Sensitivity analysis (motivated participation vs. control): post‐test differences in knowledge of suicide.

12.2. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Sensitivity analysis for gatekeeper training programs: post‐test knowledge of suicide, Outcome 2 Sensitivity analysis (unmotivated participation vs. control): post‐test differences in knowledge of suicide.

11.1. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Experimental group comparisons, gatekeeper training programs: post‐test of suicide‐related outcomes, Outcome 1 Post‐test differences in knowledge of suicide (Shipley 2003).

Knowledge of suicide prevention

One Question, Persuade, and Refer workshop delivered to students (Shipley 2003) increased short‐term knowledge of suicide prevention (SMD = 0.64, 95% CI 0.28 to 0.99; Analysis 9.3). Sensitivity analyses suggested that compared to students who received no treatment, 'voluntary' participants had a greater increase in short‐term knowledge of suicide prevention (SMD = 1.04, 95% CI 0.58 to 1.49; Analysis 13.1) than did 'involuntary' participants (SMD = 0.38, 95% CI ‐0.01 to 0.77; Analysis 13.2). A direct comparison between 'voluntary' and 'involuntary' Question, Persuade, and Refer workshop participants showed significantly greater short‐term knowledge of suicide prevention among 'voluntary' participants (SMD = 0.65, 95% CI 0.20 to 1.10; Analysis 11.2). No evidence of an effect was observed from gatekeeper training delivered to faculty and staff (Drabek 1991) (SMD = 0.06, 95% CI ‐0.50 to 0.61; Analysis 9.3) while a moderate effect was detected when delivered to peer advisors (Pasco 2012) (SMD = 0.46, 95% CI ‐0.06 to 0.98; Analysis 9.3). Question, Persuade, and Refer training delivered to peer advisors in another study (Tompkins 2009) suggested no evidence of an effect on longer‐term knowledge of suicide prevention (SMD = 0.13, 95% CI ‐0.20 to 0.46; Analysis 9.3).

9.3. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Gatekeeper training programs: post‐test measures of suicide‐related outcomes, Outcome 3 Post‐test differences in knowledge of suicide prevention.

13.1. Analysis.

Comparison 13 Sensitivity analysis for gatekeeper training programs: post‐test knowledge of suicide prevention, Outcome 1 Sensitivity analysis (motivated participation vs. control): post‐test differences in knowledge of suicide prevention.

13.2. Analysis.

Comparison 13 Sensitivity analysis for gatekeeper training programs: post‐test knowledge of suicide prevention, Outcome 2 Sensitivity analysis (unmotivated participation vs. control): post‐test differences in knowledge of suicide prevention.

11.2. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Experimental group comparisons, gatekeeper training programs: post‐test of suicide‐related outcomes, Outcome 2 Post‐test differences in knowledge of suicide prevention (Shipley 2003).

Suicide prevention self‐efficacy

The Campus Connect program delivered to peer advisors (Pasco 2012) demonstrated a large increase in short‐term suicide prevention self‐efficacy (SMD = 0.78, 95% CI 0.24 to 1.31), while another gatekeeper training program (Shipley 2003) showed a small, non‐statistically significant effect (SMD = 0.24, 95% CI ‐0.11 to 0.59; Analysis 9.4). Sensitivity analyses (Shipley 2003) suggested a small, non‐statistically significant difference in short‐term suicide prevention self‐efficacy among both "voluntary" and "involuntary" student participants compared to students who received no training, with SMD = 0.12 (95% CI ‐0.30 to 0.55; Analysis 14.1) and SMD = 0.32 (95% CI ‐0.08 to 0.71; Analysis 14.2), respectively. A direct comparison between 'voluntary' and 'involuntary' participants showed no statistically significant difference in post‐test outcome (Analysis 11.3). Question, Persuade, and Refer training delivered to peer advisors (Tompkins 2010) showed no evidence of an effect on longer‐term suicide prevention self‐efficacy (SMD = 0.15, 95% CI ‐0.18 to 0.48; Analysis 9.4).

9.4. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Gatekeeper training programs: post‐test measures of suicide‐related outcomes, Outcome 4 Post‐test differences in suicide prevention self‐efficacy.

14.1. Analysis.

Comparison 14 Sensitivity analysis for gatekeeper training programs: post‐test suicide prevention self‐efficacy, Outcome 1 Sensitivity analysis (motivated participation vs. control): post‐test differences in suicide prevention self‐efficacy.

14.2. Analysis.

Comparison 14 Sensitivity analysis for gatekeeper training programs: post‐test suicide prevention self‐efficacy, Outcome 2 Sensitivity analysis (involuntary participation vs. control): post‐test differences in suicide prevention self‐efficacy.

11.3. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Experimental group comparisons, gatekeeper training programs: post‐test of suicide‐related outcomes, Outcome 3 Post‐test differences in suicide prevention self‐efficacy (Shipley 2003).

Attitudes toward suicide

A gatekeeper training program administered to faculty and staff (Drabek 1991) and a Question, Persuade, and Refer workshop given to students (Shipley 2003) demonstrated no evidence of an effect on short‐term attitudes toward suicide, with SMD = 0.06 (95% CI ‐0.50 to 0.61) and SMD = 0.06 (95% CI ‐0.28 to 0.41) respectively (Analysis 9.5). Sensitivity analyses (Shipley 2003) displayed a slight, non‐statistically significant difference in effect between "voluntary" and "involuntary" participation when compared to students who received no treatment, SMD = 0.21 (95% CI ‐0.23 to 0.64; Analysis 15.1) and SMD = ‐0.04 (95% CI ‐0.43 to 0.35; Analysis 15.2), respectively. A direct comparison between 'voluntary' and 'involuntary' participants showed no statistically significant difference in post‐test outcome (Analysis 11.4).

9.5. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Gatekeeper training programs: post‐test measures of suicide‐related outcomes, Outcome 5 Post‐test differences in attitudes toward suicide.

15.1. Analysis.

Comparison 15 Sensitivity analysis for gatekeeper training programs: post‐test attitudes towards suicide, Outcome 1 Sensitivity analysis (motivated participation vs. control): post‐test differences in attitudes towards suicide.

15.2. Analysis.

Comparison 15 Sensitivity analysis for gatekeeper training programs: post‐test attitudes towards suicide, Outcome 2 Sensitivity analysis (unmotivated participation vs. control): post‐test differences in attitudes towards suicide.

11.4. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Experimental group comparisons, gatekeeper training programs: post‐test of suicide‐related outcomes, Outcome 4 Post‐test differences in attitudes towards suicide (Shipley 2003).

Gatekeeper behavior

Among peer advisors who received a Question, Persuade, and Refer training compared to no training (Tompkins 2009), no evidence of a longer‐term effect on suicide‐related gatekeeper behavior was found (SMD = ‐0.01, 95% CI ‐0.34 to 0.32; Analysis 9.6).

9.6. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Gatekeeper training programs: post‐test measures of suicide‐related outcomes, Outcome 6 Post‐test differences in gatekeeper behaviors.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Our review identified eight eligible, completed studies, only one of which provided any data on completed suicides, our primary outcome. The lack of studies examining health outcomes is an important finding that demonstrates a major gap in the research literature. Seven studies assessed only indirect measures, including suicide‐related knowledge, attitudes, and self‐reported gatekeeper behavior. As these measures have neither been directly linked to health outcomes, nor indirectly linked to health outcomes through correlation with previously validated measures, it is unclear whether observed changes in the measures will result in reductions in suicidal behavior or completed suicide. While completed suicides are rare, non‐fatal suicidal behavior (i.e. suicide attempts) is more common and therefore potentially feasible to measure in intervention studies. As such studies become available, combining them quantitatively through meta‐analysis may provide sufficient power to assess intervention effects on this important health outcome.

This review aimed to summarize the best available evidence on interventions for the primary prevention of suicide in post‐secondary settings. However, all of the included studies evaluated interventions targeting students at both the primary and secondary prevention levels. Hence we were unable to determine the independent effect of primary preventive interventions on suicide‐related outcomes.

The studies were heterogeneous in terms of participants, study designs, and interventions. As specified in our protocol (Harrod 2011), the main effects identified in the included studies are described according to the type of intervention implemented (see below). We have presented results, GRADE ratings, and associated comments from studies of classroom‐based instructional programs can be found in Table 1. Results from studies of gatekeeper training programs can be found in Table 2. We did not summarize results from the single study evaluating institutional policy in a table.

1. Findings for gatekeeper training programs (non‐randomized studies).

| What are the effects of gatekeeper training programs on suicidal behavior and ideation, knowledge of suicide and suicide prevention, suicide prevention self‐efficacy, attitudes toward suicide and gatekeeper behavior? | ||

|

Patient or population: Post‐secondary students, faculty and staff Settings: Public and private universities located in urban and rural settings Intervention: Campus Connect and Question, Persuade, and Refer gatekeeper training programs and workshops Comparison: Delayed treatment control groups or no treatment | ||

| Outcomes | SMD (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) |

| Completed suicide at the end of active intervention | N/A | N/A |

| Suicidal ideation at the end of active intervention | N/A | N/A |

| Attempted suicide at the end of active intervention | N/A | N/A |

| Knowledge of suicide at the end of active intervention | 0.86 (0.28 to 1.44) 0.63 (‐0.02 to 1.28) |

53 (1 study) 116 (1 study) |

| Knowledge of suicide prevention at the end of active intervention | 0.06 (‐0.50 to 0.61) 0.46 (‐0.06 to 0.98) 0.64 (0.28 to 0.99) 0.13 (‐0.20, 0.46)† |

53 (1 study) 65 (1 study) 136 (1 study) 146 (1 study) |

| Suicide prevention self‐efficacy at the end of active intervention | 0.78 (0.24 to 1.31) 0.24 (‐0.11 to 0.59) 0.15 (‐0.18 to 0.48)† |

64 (1 study) 136 (1 study) 146 (1 study) |

| Attitudes toward suicide at the end of active intervention | 0.06 (‐0.50 to 0.61) 0.06 (‐0.28, 0.41) |

53 (1 study) 134 (1 study) |

| Gatekeeper behavior at the end of active intervention | ‐0.01 (‐0.34 to 0.32)† | 146 (1 study) |

†Post‐test outcomes measured at four to six months follow‐up.

Classroom‐based instructional programs

In three RCTs, totaling 312 students (Abbey 1989; Abbey 1990; Holdwick 2000), classroom instruction featuring experiential and didactic components greatly increased short‐term knowledge of suicide and also improved knowledge of suicide prevention, but had little or no evidence of an effect on short‐term suicide prevention self‐efficacy (Table 1). In one RCT (Abbey 1990), a large, statistically significant difference was detected between experiential and didactic classroom instruction on students' short‐term knowledge of suicide, suggesting that didactic intervention may be more beneficial (Analysis 4.1). Although differences were not statistically significant (Analysis 4.2), motivational enhancement programs may improve students' short‐term suicide prevention self‐efficacy more than education‐based instruction. None of the RCTs tested long‐term effects of the instructional interventions nor the effects on suicidal behavior or completed suicides among students. Differing outcome measures may have contributed to observed statistical differences in results between studies, as exclusion of one trial (Holdwick 2000) that used a different instrument from the other two (Abbey 1989; Abbey 1990) reduced or eliminated these differences for knowledge‐related outcomes.

Policy‐based intervention