Abstract

The role of the first intron of the Col1A1 gene in the regulation of type I collagen synthesis remains uncertain and controversial despite numerous studies that have made use of transgenic and transfection experiments. To examine the importance of the first intron in regulation of the gene, we have used the double-replacement method of gene targeting to introduce, by homologous recombination in embryonic stem (ES) cells, a mutated Col1A1 allele (Col-IntΔ). The Col-IntΔ allele contains a 1.3-kb deletion within intron I and is also marked by the introduction of a silent mutation that created an XhoI restriction site in exon 7. Targeted mice were generated from two independently derived ES cell clones. Mice carrying two copies of the mutated gene were born in the expected Mendelian ratio, developed normally, and showed no apparent abnormalities. We used heterozygous mice to determine whether expression of the mutated allele differs from that of the normal allele. For this purpose, we developed a reverse transcription-PCR assay which takes advantage of the XhoI polymorphism in exon 7. Our results indicate that in the skin, and in cultured cells derived from the skin, the intron plays little or no role in constitutive expression of collagen I. However, in the lungs of young mice, the mutated allele was expressed at about 75% of the level of the normal allele, and in the adult lung expression was decreased to less than 50%. These results were confirmed by RNase protection assays which demonstrated a two- to threefold decrease in Col1A1 mRNA in lungs of homozygous mutant mice. Surprisingly, in cultured cells derived from the lung, the mutated allele was expressed at a level similar to that of the wild-type allele. Our results also indicated an age-dependent requirement for the intact intron in expression of the Col1A1 gene in muscle. Since the intron is spliced normally, and since the mutant allele is expressed as well as the wild-type allele in the skin, reduced mRNA stability is unlikely to contribute to the reduction in transcript levels. We conclude that the first intron of the Col1A1 gene plays a tissue-specific and developmentally regulated role in transcriptional regulation of the gene. Our experiments demonstrate the utility of gene-targeting techniques that produce subtle mutations for studies of cis-acting elements in gene regulation.

Collagens are among the most abundant extracellular matrix proteins in vertebrate organisms. They maintain the structural integrity of tissues and mediate a wide variety of cell-matrix interactions. Type I collagen is a heterotrimer composed of two polypeptides encoded by the Col1A1 and Col1A2 genes. The transcriptional regulation of these two genes (reviewed in references 1, 10, 21, 28, 42, and 46) is of special interest because they are expressed at widely different levels which reflect the tissue-specific and developmental regulation of type I collagen synthesis. Furthermore, transcription of the Col1A1 and Col1A2 genes is responsive to cues generated by injury and repair and is modulated by a variety of cytokines, hormones, and pharmacological agents (1, 10, 28, 42, 46). Finally, the expression of type I collagen genes is disturbed in fibrotic disorders such as pulmonary fibrosis, cirrhosis, and scleroderma (13, 14, 18). Although both transcriptional and posttranscriptional mechanisms are involved in regulation, the concordance between mRNA levels and type I collagen synthesis suggests that the predominant mode of control is transcriptional (46).

Cell-specific expression of Col1A1 is conferred by a modular arrangement of promoter elements in the 5′ flanking region of the gene (41, 45). The lethal phenotype of homozygous Mov 13 mice, which contain the Moloney murine leukemia retrovirus (MMLV) within the first intron of Col1A1, was the first indication that this intron might also be important in regulating expression of the gene (47). Subsequently, it was demonstrated that the retroviral insertion led to transcriptional inactivation of the gene in mouse embryo cell lines (24). It was also shown that the Col1A1 gene was transcribed in odontoblasts and osteoblasts and that in these cells, the first intron along with the integrated retrovirus was spliced out (30, 31, 48). These findings implied that incorrect splicing could not account for the lethality of the mutation in homozygous mice and that different cis-acting elements function in the regulation of Col1A1 in different cells. Since some of these elements could be placed in the first intron, numerous studies, using both transfection and transgenic approaches, have been designed to investigate transcriptional regulation by the first intron and to identify possible responsible regulatory elements, but these experiments have resulted in conflicting conclusions (reviewed in reference 8). While some studies have demonstrated a role for the intron in regulation and have identified cis-acting sequences that bind Sp1 and AP1 as important elements (6, 9, 29, 33–35, 44, 51, 52), other studies have indicated that the intron does not regulate expression of the gene (40, 53, 54). Thus, the role of the first intron in the regulation of the Col1A1 gene remains uncertain and controversial.

In recent years, the study of gene function has been assisted greatly by gene-targeting techniques (15, 38). Several methods for the introduction of mutations in the mouse genome have been described (3, 19, 23, 25, 55, 58, 59). Despite the potential advantages, relatively few studies have used these approaches to determine the role of cis-acting sequences (7, 20, 37, 50, 57). In this report, we describe the generation of a mouse model for the study of regulation mediated by the first intron of the Col1A1 gene. A double-replacement procedure (59), also termed tag and exchange (3), was used to create a mutated Col1A1 allele that contains a large deletion within the first intron and a silent mutation within exon 7; the latter generates a new XhoI restriction site. In heterozygous mice, reverse transcription (RT)-PCR followed by XhoI restriction analysis can be used to quantify the relative abundance of transcripts derived from the two alleles. In this study, we describe the approach and demonstrate that an intact first intron is required for normal transcription of Col1A1 mRNA in the lungs and muscle of adult mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of mutant mice.

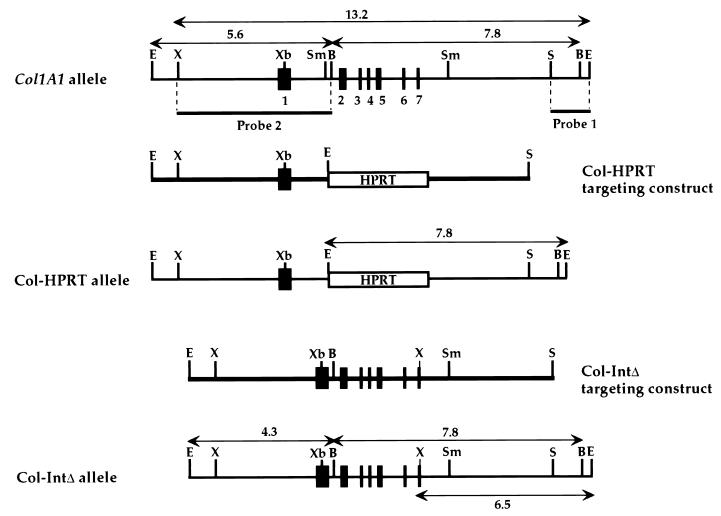

Mouse 129 genomic clones, containing fragments of the Col1A1 gene, were kindly provided by H. Wu and were assembled to form a 12.8-kb EcoRI-SphI sequence. This sequence and two targeting constructs derived from it are shown in Fig. 1. In the Col-HPRT construct, the ∼3-kb HPRT (hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase) gene under the control of the PGK promoter (49) replaces an internal 4.1-kb SmaI fragment, creating a targeting construct with ∼5.5 kb of 5′ identity and ∼3.2 kb of 3′ identity with the endogenous allele. The Col-IntΔ targeting construct contains a 1,283-bp deletion within the first intron and a single base alteration within exon 7 which generates an XhoI restriction endonuclease cleavage site. Although this change in exon 7 alters the genomic sequence and the sequence of the Col1A1 transcript, it preserves the identity of the amino acid residue at that position.

FIG. 1.

Map of the murine wild-type and mutant alleles and of the targeting constructs used in the double-replacement procedure. The relevant 14-kb EcoRI-EcoRI fragment of the Col1A1 allele, and its derivatives in the Col-HPRT and Col-IntΔ alleles, are shown. The fragments from which probes 1 and 2 were derived and the sizes, in kilobases, of the restriction fragments (lines with double-headed arrows) which were used in the genotyping of ES cells and mice are also shown. Exons 1 to 7 are not drawn to scale, and exons 3′ to exon 7 are omitted for the purpose of clarity. Locations of the restriction enzyme sites BamHI (B), EcoRI (E), SmaI (Sm), SphI (S), XhoI (X), and XbaI (Xb) are indicated.

As a first step in the generation of the XhoI mutation, an EcoRV-SmaI fragment containing exon 7 was subcloned into pBluescript SK (+). A PCR-based procedure was then used to synthesize a fragment identical in sequence, except for the alteration. For the PCR, the complementary oligonucleotides 5′ GCCAGGGAGACCTCGAGGACCAGA 3′ and 5′ TCTGGTCCTCGAGGTCTCCCTGGC 3′ (mutated bases underlined) specific to the Col1A1 gene were used along with the reverse and M13 −20 primers which flank the fragment and are situated in the vector. A 1,283-bp deletion within the first intron of the Col1A1 gene, 5′ to the BamHI site (Fig. 1), was generated by controlled exonuclease III digestion of DNA. The deleted intron is thus composed of 110 bp 5′ to the BamHI site and 68 bp of 3′ sequence. All of the nucleotide changes were confirmed by sequencing relevant subclones.

E14TG2a HPRT− embryonic stem (ES) cells (a gift from T. Doetschman) were cultured on neomycin-resistant STO cells in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM; high glucose; 4.5 g/liter) supplemented with 15% fetal calf serum (ES qualified; GIBCO-BRL), 0.1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 2 mM l-glutamine, penicillin G (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), nonessential amino acids (0.1 mM each; GIBCO-BRL), and leukemia inhibitory factor (1,000 U/ml; GIBCO-BRL). The double-replacement procedure for the generation of cells targeted with the Col-IntΔ construct was performed essentially as described previously (39, 55, 59). Cells (2 × 107) were electroporated with 30 μg of linearized targeting DNA. To target Col-HPRT to the Col1A1 locus, selection with 100 μM hypoxanthine, 0.8 μM aminopterin, and 20 μM thymidine was started 24 h after electroporation, and resistant colonies were picked 8 to 10 days later. Appropriately targeted cells were electroporated with Col-IntΔ DNA in the second replacement step of the procedure. Six days later, cells were plated at a density of 1.5 × 106 cells per 10-cm-diameter dish in selection media containing 6-thioguanine (5 μg/ml). Surviving colonies were picked 2 weeks later and were screened by Southern blotting for proper targeting of the mutations to the locus. Since a strong correlation between karyotypic abnormality and poor germ line transmission has been reported previously (36), we determined the karyotypes of correctly targeted clones and selected those with a normal complement of chromosomes for blastocyst injections. Chimeric mice, generated after blastocyst injections of ES cell clones, were bred to produce homozygous and heterozygous Col-IntΔ mice.

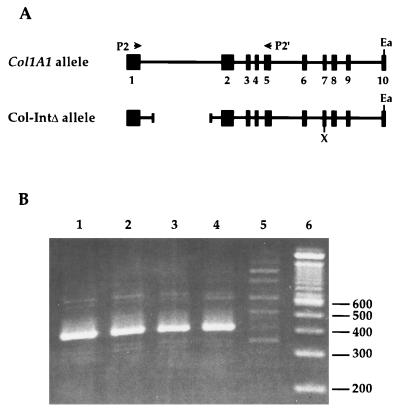

Identification of ES cells containing correctly targeted clones was done by Southern blot analysis. The strategy for screening can be discerned from Fig. 1, which also shows the relevant restriction sites, diagnostic DNA fragments, and the fragments used in the preparation of probes 1 and 2. Mouse genotyping was done by PCR using primers P1 and P1′ (Fig. 2C). The primers amplify a 750-bp fragment of genomic DNA containing the XhoI mutation. Restriction analysis of this fragment with XhoI is thus able to distinguish between the different mouse genotypes, as shown in Fig. 2D.

FIG. 2.

Identification of targeted ES cell clones and procedure for determining the genotype of mice. (A) Representative Southern blot, hybridized with probe 1, showing EcoRI-restricted fragments diagnostic for wild-type (lane 1) and Col-HPRT-targeted (lane 2) ES cell clones. (B) Representative Southern blot hybridized with probes 1 and 2, showing EcoRI- and BamHI-restricted fragments diagnostic for wild-type (lane 1) and Col-IntΔ-targeted (lane 2) ES cell clones. (C) A portion of the Col1A1 locus containing exons 6 to 9 (shown as rectangles) is illustrated. Also indicated are the locations of primers P1 and P1′ (shown as arrowheads) and of the XhoI restriction site within the Col-IntΔ allele. (D) Genotyping of wild-type (lane 1), heterozygous (lane 2), and homozygous (lane 3) mutant mice was accomplished by PCR analysis of DNA using primers P1 and P1′. After restriction with XhoI, the 750 bp of amplified genomic DNA gives rise to fragments of 520 and 230 bp, only if derived from the mutant allele.

COS cell culture, transfection, and PCR analysis.

COS cells were cultured in high-glucose DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (GIBCO-BRL), 2 mM l-glutamine, penicillin G (100 U/ml), streptomycin, and nonessential amino acids (0.1 mM each; GIBCO-BRL); 1.5 × 106 cells were transfected with 20 μg of DNA in a BRL Cell-Porator (800 μFa, 150 V). Stable transfectants were selected by means of cell culture in medium containing G418 (800 μg/ml), added 24 h after electroporation.

For the transfection studies shown in Fig. 3B, XbaI-EagI fragments of the wild-type and Col-IntΔ alleles were cloned into the pcDNA3 expression vector (Invitrogen). The XbaI site is located 5′ to the translation initiation codon in Fig. 1, and the EagI site is located in exon 10. The Stratascript RT-PCR kit was used to identify mRNA derived from expression of the pcDNA3 constructs. Conditions recommended by the manufacturer were followed. Three hundred nanograms of primer P2′ (5′ GCTAGTCGACATCGATCAGGAAGCAAAGTTTCCTCCAAG 3′) was used for the synthesis of the first-strand cDNA (Fig. 3A); 10 pmol each of primers P2 (5′ CCACTGCCCTCCTGACGCATG 3′) and P2′ were then used for amplification of the cDNA (Fig. 3A). The underlined portion of P2′ is a polylinker sequence used in other cloning experiments; the remainder of the primer is derived from the Col1A1 cDNA sequence and is identical with sequence located at the exon 5/6 boundary. The sequence of primer P2 is located at the 3′ end of exon 1. Amplification of Col1A1 transcript by primer P2 and P2′, as described above, should generate a 428-bp fragment from RNA of cells stably transfected with genomic collagen sequences derived from either the wild-type or Col-IntΔ allele, provided that splicing of deleted intron 1 occurred normally in transcripts derived from the Col-IntΔ allele.

FIG. 3.

The mutation within the first intron does not hinder its capacity to be spliced correctly. (A) The relevant segment (exons 1 to 10 are shown as boxes) of the two alleles is shown, along with the positions of priming by P2 and P2′, the deletion within intron 1, and the locations of the XhoI and EagI restriction enzyme sites. (B) RNA isolated from COS cells transfected with pcDNA3 (lane 5), wild-type Col1A1-pcDNA3 (lanes 1, 2), or Col-IntΔ-pcDNA3 (lanes 3, 4) plasmid DNA was subjected to RT-PCR using primers P2 and P2′. Amplified DNA was electrophoresed on a 4% polyacrylamide gel and stained with ethidium bromide. Positions of the 200- to 600-bp DNAs in the size ladder (lane 6) are indicated.

Isolation of cells from lung and skin.

Lung and back skin (taken from neonatal mice) were minced finely and were incubated for 30 min in a 2-mg/ml solution of collagenase (CLS1; Worthington Biochemical Corporation) at 37°C. Cells were cultured in high-glucose DMEM supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum (GIBCO-BRL), 2 mM l-glutamine, penicillin G (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), amphotericin B (Fungizone; 0.25 μg/ml), and nonessential amino acids (0.1 mM each; GIBCO-BRL).

Quantification of allele-specific expression.

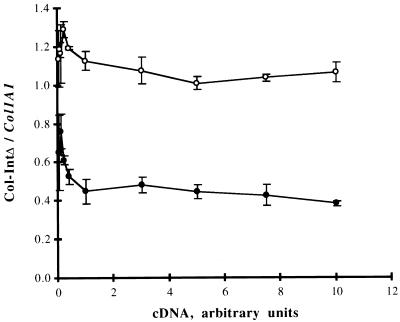

The StrataScript RT-PCR kit (Stratagene Cloning Systems) was used to perform RT-PCR on RNA extracted by the guanidinium thiocyanate method (16). For quantitation of allele-specific transcripts, 300 ng of primer P3′ (5′ CCGGGCTTGCCAGCTTCCCATCATC 3′) was used for synthesis of first-strand cDNA from 5 μg of RNA; 5 μl of the reaction products containing cDNA (the volume used varied in the experiments reported in Fig. 6) was then subjected to 25 cycles of amplification at an annealing temperature of 65°C in the presence of 100 ng of primers P3 (5′ CCACGCATGAGCCGAAGCTAACCCC 3′) and P3′ and 1 mM MgCl2. For a determination of the relative abundance of the XhoI-resistant and XhoI-sensitive fragments (indicative of transcription from the wild-type and mutant alleles, respectively), [32P]dCTP (1 μCi/sample) was added to the samples and a 26th amplification cycle was run. The addition of [32P]dCTP prior to the final amplification cycle prevents erroneous estimates of transcript abundance attributable to heteroduplex formation between the two species of transcripts, since only DNAs synthesized during this cycle, which will not be heteroduplexed, will have incorporated the isotope and contribute to quantification. Labeled samples were restricted with XhoI, electrophoresed on a 4% acrylamide gel, dried, and subjected to phosphorimager analysis. Counts were determined for the 750- and 600-bp fragments only. To correct for the number of dCTP nucleotides in the smaller 150-bp XhoI fragment that was derived from the Col-IntΔ allele, the counts obtained for the 600-bp DNA fragment were multiplied by 1.3. The values are expressed as a ratio of XhoI-sensitive fragment abundance relative to XhoI-resistant fragment abundance. Thus, a value of 1 is expected if the two alleles are transcribed equally well, and a value of 0.5 is expected if the mutant allele is transcribed half as well as the wild-type allele.

FIG. 6.

Ratio of Col-IntΔ to Col1A1 allelic expression in lung (•) and skin (○) as determined by RT-PCR. The relative abundance of the Col-IntΔ transcript was determined as a function of increasing amounts of first-strand cDNA. Average values and standard deviations of determinations from three adult mice are shown.

RNase protection.

RNase protection assays were conducted by use of the Hyb-Speed RPA kit (Ambion). For these experiments, a 305-bp fragment of the murine Col1A1 cDNA containing exons 2, 3, and 4 and the first 42 bp of exon 5 was cloned into pBluescript KS (+); 400-bp [32P]CTP labeled transcripts, containing the Col1A1 sequence, were generated from this clone by in vitro transcription with T3 RNA polymerase and were used in RNase protection experiments. Samples were simultaneously hybridized in the same tube with the Col1A1 probe and with a mouse β-actin probe which was generated by using the clone provided in the kit. For each sample, the amount of Col1A1 transcript was normalized to the amount of protected β-actin. Protected fragments were resolved on a 5% acrylamide gel and subjected to phosphorimager analysis for quantification.

RESULTS

Generation of Col-IntΔ mice.

The introduction of subtle mutations into a locus by double replacement, utilizing a mouse HPRT minigene/HPRT-deficient ES cell system, has been described previously (39). The replacement of one of the two Col1A1 alleles in E14TG2a ES cells with the Col-IntΔ allele, which lacks 1,283 bp of the 1,462-bp first intron, was achieved in a similar manner (Fig. 1). Targeting of Col-HPRT to the Col1A1 locus was accomplished by selection for the presence of HPRT enzymatic activity, followed by the identification of homologous recombination events in ES clones by Southern analysis of DNA restricted with EcoRI (Fig. 2A). Whereas the Col1A1 allele yielded a hybridizing fragment of 14 kb (Fig. 2A, lane 1), the Col-HPRT allele gave rise to a 7.8-kb fragment (Fig. 2A, lane 2). Nine positive clones were identified among the 146 that were examined. A single target clone was expanded and utilized for the second step of the procedure, in which negative selection was used to accomplish the replacement of the Col-HPRT allele with the Col-IntΔ allele (Fig. 1). For the identification of clones targeted by homologous recombination, ES cell clones were screened in two different ways. EcoRI- and XhoI-restricted DNA was hybridized with probe 1, which identifies a 13.2-kb hybridizing fragment from the Col1A1 allele and a 6.5-kb hybridizing fragment from the Col-IntΔ allele (data not shown). In addition, DNA was restricted with EcoRI and BamHI and was hybridized with a mixture of probe 1 and probe 2. Under these conditions, wild-type ES cells yielded 7.8- and 5.6-kb fragments (Fig. 2B, lane 1), whereas targeted clones yielded hybridizing fragments of 7.8, 5.6, and 4.3 kb (Fig. 2B, lane 2). Genotyping of the mice was accomplished by PCR analysis of tail DNA with primers P1 and P1′ (Fig. 2C). Whereas the wild-type allele gave rise to an XhoI-resistant 750-bp fragment (Fig. 2D, lanes 1 and 2), the corresponding fragment derived from the Col-IntΔ allele was cleaved into 520- and 230-bp fragments (Fig. 2D, lanes 2 and 3).

Two clones (107 and 111), which were determined to be of normal karyotype, were injected into blastocysts, and the blastocysts were transferred into pseudopregnant females. The resultant chimeras were bred to raise the mice which were used for the experiments reported in this study. Similar results were obtained with mice from either cell line. Physical examination of homozygous mutant mice indicated that there were no gross morphological differences from their wild-type littermates, and histological examination of collagen-containing tissues showed no abnormalities (data not shown).

The deleted intron is correctly spliced.

We have generated mice bearing a 1,283-bp deletion within the first intron of the Col1A1 locus (Col-IntΔ allele). Although splicing signals and sufficient intronic sequence were left intact, we wished to examine the capacity of the mutated first intron to be spliced correctly. For this purpose, we cloned a fragment of Col-IntΔ, extending from the start of translation in exon 1 to an EagI site in exon 10, into the eukaryotic expression vector pcDNA3. A construct which contains the wild-type intronic sequence was generated for comparison. COS cells, which synthesize levels of Col1A1 transcript that are undetectable by Northern blot analysis (data not shown), were transfected with pcDNA3 and with two independently derived plasmid clones of each of the two constructs. As shown in Fig. 3B, RT-PCR using primers P2 and P2′ amplified a 428-bp DNA fragment from both the wild-type (lanes 1 and 2)- and Col-IntΔ (lanes 3 and 4)-transfected cells but not from cells transfected with pcDNA3 (lane 5). No additional fragment with a size of 606 bp, which would be expected if the deleted intron was not properly spliced, was detected in lanes 3 and 4. We therefore conclude that the deletion within the first intron does not affect its capacity to be spliced correctly.

Quantification of expression of Col1A1 and Col-IntΔ in heterozygous mice.

Col1A1 and Col-IntΔ, the two alleles in a heterozygous mouse, are expected to produce transcripts that are identical in sequence except for the single base pair alteration which gives rise to the XhoI restriction enzyme cleavage site in the Col-IntΔ allele. Furthermore, since the deletion in the first intron and the mutation are linked, all transcripts containing the XhoI site in exon 7 must be derived from the Col-IntΔ allele. Thus, the relative abundance of XhoI-containing and XhoI-lacking transcripts should reflect the transcriptional activity of the two alleles. In this way, it should be possible to determine whether the first intron plays a regulatory role in the expression of the Col1A1 gene in different tissues.

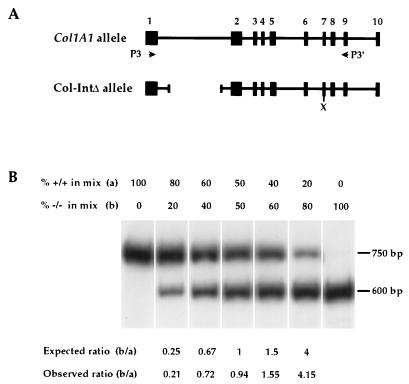

Based upon the above principle, we have developed an RT-PCR assay that measures expression from one allele relative to the other. The accuracy of this assay was first tested in mixing experiments in which cDNAs from homozygous mutant and wild-type mice were combined in different ratios (Fig. 4). Good agreement between the observed and expected ratios of allelic expression (based upon the known compositions of the mixes) was obtained. Thus, these results demonstrate that the relative abundance of the Col-IntΔ transcript can be determined accurately by measuring the relative amounts of the XhoI-resistant and XhoI-sensitive fragments. It should be noted that the RT-PCR procedure is useful for monitoring the relative expression of the wild-type and mutant alleles in different tissues and under different pathological and developmental conditions, but it does not measure total Col1A1 expression. A similar approach was used by Fiering et al. (20) to study the importance of the 5′HS2 element for expression of murine β-globin genes.

FIG. 4.

Mixing experiments to demonstrate the accuracy of the RT-PCR/XhoI restriction digest assay for quantification of the ratio of abundance of Col-IntΔ to Col1A1 transcripts. (A) The relevant segments (exons 1 to 10 are shown as boxes) of the two alleles are shown, along with the positions of priming by P3 and P3′, the deletion within intron 1, and the location of XhoI within the Col-IntΔ allele. (B) RT reaction was performed on RNA extracted from homozygous wild-type rib and mutant muscle. Assays were performed by mixing the RT reactions from the two genotypes in the denoted amounts (RT reactions were normalized to give equal activity per volume of the 750- and 600-bp fragments from wild-type and mutant reactions, respectively), amplifying by PCR, and digesting with XhoI. The observed ratios are compared to the ratios expected from the known compositions of the mixes.

Expression of the Col-IntΔ allele in skin and muscle.

The RT-PCR procedure described above was used to determine the ratio of allele-specific transcripts in skin and muscle of mice heterozygous for the Col-IntΔ allele. The results indicate that the mutant allele transcript was as abundant as its wild-type counterpart in skin (Table 1). The age of the mouse did not seem to affect the level of expression of the mutant allele since the Col-IntΔ/Col1A1 expression ratios were similar in mice ranging in age from 7 to 168 days (Table 1). Scattered determinations of this ratio in mice older than 6 months gave no indication of a reduction in this ratio (data not shown). The ratio of expression of the two alleles in cultured dermal cells derived from two different mice (1.03 ± 0.06 [n = 6] and 1.03 ± 0.07 [n = 3]) was also found to be in the range of that observed in skin. In contrast to skin, Col-IntΔ/Col1A1 ratios in muscle showed a significant decline in older mice. Thus, the mutant and wild-type alleles were expressed equally well in young adults, but at some point between the ages of 2 and 6 months this ratio dropped to between 0.6 and 0.5 (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Ratio of expression of Col-IntΔ and Col1A1 alleles in skin and muscle

| Mouse | Age (days) | Col-IntΔ/Col1A1 (mean ± SD)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Skin | Muscle | ||

| 1b | 7 | 1.27 ± 0.02 (3c) | NDd |

| 2b | 7 | 1.09 ± 0.08 (3) | ND |

| 3a | 39 | 1.11 ± 0.08 (2) | 1.10 ± 0.07 (4) |

| 4a | 39 | 0.98 ± 0.06 (2) | 1.15 ± 0.03 (4) |

| 5b | 47 | 1.08 ± 0.09 (3) | 1.05 ± 0.06 (3) |

| 6b | 47 | 1.03 ± 0.07 (4) | 1.08 ± 0.12 (4) |

| 7a | 56 | 1.17 ± 0.02 (2) | 1.04 ± 0.01 (2) |

| 8a | 168 | 1.10 ± 0.12 (5) | 0.63 ± 0.05 (7) |

| 9a | 254 | ND | 0.60 ± 0.06 (3) |

| 10a | 254 | ND | 0.49 ± 0.04 (5) |

Derived from ES cell line 107.

Derived from ES cell line 111.

Number of determinations.

ND, not determined.

Expression of the Col-IntΔ allele is reduced in the lung and is further reduced as a function of age.

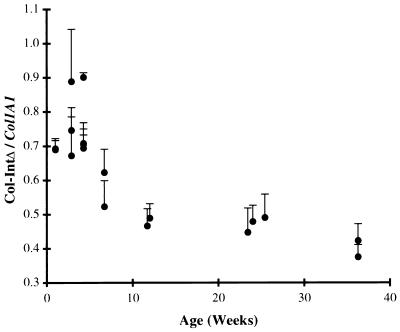

In contrast to skin and muscle, the level of expression of the mutant allele was considerably lower than that of the wild-type allele in lungs of young animals (Fig. 5 and 6). Furthermore, age was determined to influence the ratio of expression of the two alleles in this tissue (Fig. 5). Thus, the average of the Col-IntΔ/Col1A1 ratios for nine premature mice aged 7 to 30 days was 0.74, that for two young adult mice aged 47 days was 0.58, and that for seven mature mice aged 82 to 254 days was 0.45. The correlation between age and ratio of expression in lung for the mice shown in Fig. 5, r = −0.80, was determined to be highly significant (P < 10−4). Thus, it appears that in the lung, the influence of the intron on transcriptional regulation is evident at a young age and becomes more pronounced as the animals grow older. In three of the mice for which ratios of allelic expression in lung were determined to be 0.48, 0.52, and 0.62, the corresponding ratios in skin were 1.10, 1.08, and 1.03. Thus, it is clear that within the same animal, tissue-specific differences in the extent to which the deletion in the first intron influences allelic expression are observed. Interestingly, expression of the Col-IntΔ allele was determined to be normal or slightly high (1.28 ± 0.06 [n = 3] and 1.12 ± 0.04 [n = 5]) in cultured cells derived from lungs of a 3- and a 4-month-old mouse. It is unclear whether the small increase in expression of the Col-IntΔ allele is due to a lack of an inhibitory role for the first intron in cells subjected to culture conditions or whether it is due to a relative proliferation of some cells, among the many types present in lung (see Discussion), which are less dependent on the first intron for expression of the Col1A1 transcript. In any event, the data suggest that conclusions regarding the role of the first intron in regulation should consider the possibility that the modulatory effects of the first intron on Col1A1 gene expression may differ in vitro and in vivo.

FIG. 5.

Ratio of Col-IntΔ to Col1A1 allelic expression in lung decreases with age. The relative abundance of the Col-IntΔ transcript was plotted as a function of the age of the mouse. Average values and standard deviations of a minimum of three determinations are shown.

The averages of the ratios of expression of Col-IntΔ and Col1A1 as a function of the amount of cDNA in the RT-PCR, obtained from the lungs and skin of three adult mice, are shown in Fig. 6. The data clearly indicate that the expression of the mutant allele is equal to the wild-type level in the skin but is only about half of this level in the lung. Furthermore, the data demonstrate that for a given tissue sample, the ratio of expression was constant with increasing amounts of the first-strand cDNA used in the RT-PCR. The total amount of amplified product increased substantially over the 250-fold increase in first-strand cDNA, but as shown in Fig. 6, this change did not affect the ratio of expression of the two alleles. Thus, the determinations of allelic expression ratios should be valid in tissues that differ in their levels of collagen gene expression by a factor of 2 to 3 orders of magnitude, and the lower ratio in adult lung than in skin is unlikely to result from technical difficulties in dealing with the lower abundance of collagen mRNA in the former tissue.

Determination of Col1A1 transcript abundance by RNase protection.

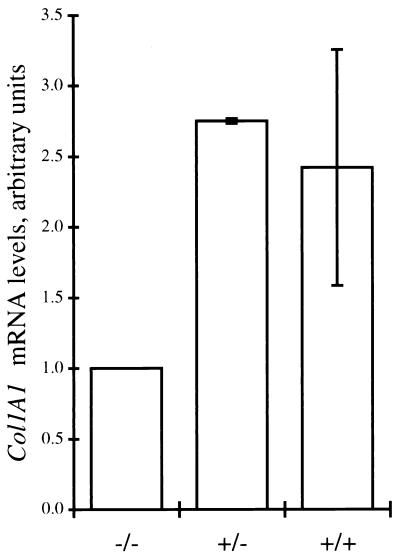

The results of the RT-PCR assays shown in Fig. 5 and 6 predict that lungs of adult wild-type mice should contain twice as much Col1A1 mRNA as lungs of homozygous Col-IntΔ mice. To confirm the RT-PCR results, we measured the total amount of Col1A1 transcript in tissues of wild-type and homozygous Col-IntΔ mice by RNase protection. The assays were conducted on RNA derived from sex-matched siblings of the same litter (5 to 6 months old) to reduce age- and sex-related variability. For each sibling set, the amount of Col1A1 transcript in a homozygous mutant mouse was compared to the amount detected in its wild-type or heterozygous littermate. The results of experiments with three sets of mice show that lungs of wild-type mice contained about 2.5 times the amount of Col1A1 transcript found in their homozygous mutant siblings (Fig. 7). Interestingly, lungs of heterozygous mutant mice were found to contain a similar excess of Col1A1 transcript (Fig. 7). Thus, the wild-type allele might be capable of compensating for reduced expression of the intron-deleted gene.

FIG. 7.

Determination of Col1A1 mRNA levels by RNase protection. Col1A1 mRNA levels in lungs of four heterozygous and three homozygous wild-type mice (5 to 6 months old) and their five homozygous mutant littermates were quantified by an RNase protection assay. The amount of Col1A1 mRNA in heterozygous and wild-type homozygous mice is expressed as the relative increase in abundance over that detected in a homozygous mutant littermate.

DISCUSSION

We have used a gene-targeting approach to introduce, into the murine Col1A1 locus, a mutated Col1A1 allele (Col-IntΔ) bearing a large deletion within the first intron and a single nucleotide substitution in exon 7. The nucleotide substitution generated a new XhoI restriction site. An RT-PCR assay, which takes advantage of the XhoI polymorphism and its linkage to the deletion in intron 1, was then developed for the quantification of allele-specific transcription. The RT-PCR/XhoI restriction digest assay was used to examine the relative abundance of allele-specific mRNA in different tissues of heterozygous Col-IntΔ mice. Our data show that the shortened first intron, which is still spliced correctly, does not affect transcription of Col1A1 mRNA in skin but results in a substantial, age-dependent decrease in abundance of Col-IntΔ mRNA in the lung and muscle. Thus, our results establish a developmental and tissue-specific role for the first intron in transcriptional regulation of the α1(I) collagen gene in mice. Additional effects of the intron in induced expression of Col1A1 are possible.

The role of the first intron in regulation of expression of the α1(I) collagen gene has been studied extensively both in transfected cells and in transgenic animals, but little agreement on the nature of the effect, or even on its existence, has been achieved (8, 11). A number of possible reasons for the conflicting results of previous experiments can be advanced. The majority of experiments were performed by transfection of promoter-reporter gene constructs in cultured cells. These experiments were restricted by the choice of the promoter, usually a 5′ flanking sequence contiguous with the first exon and intron, or intronic sequences placed 5′ or 3′ to the promoter-reporter cassette, and by the type and culture conditions of the cells. The limitations of these experiments include the likely requirement for a precise geometry of the transcription initiation complex, which may not be accommodated by some constructs (9, 56), and distinct differences in the transcriptional activity of fibroblastic cells such as dermal fibroblasts and NIH 3T3 cells (9). The use of an α1(I) minigene in place of a promoter-reporter gene construct in transfection experiments (40) has averted some of these drawbacks, but even minigenes are limited in the extent to which 5′ and 3′ flanking sequences can be represented, and there are possible uncertainties in quantification that can result from differences in the levels of stability of the initial and mature transcripts in comparison with that of Col1A1 mRNA. The results of transgenic experiments have also been controversial (8, 35, 53, 54), in part because of the need to compare different constructs and the possible confounding effects of copy number and site of insertion on expression of the transgene.

The introduction of a deletion in the first intron of the Col1A1 gene by gene targeting, and the concomitant generation of a linked polymorphism, circumvent most of the shortcomings of transfection and transgenic approaches and, as was done in this study, enable the investigator to compare the expression of the mutant and wild-type collagen alleles accurately within the same tissue sample. Our observations provide partial explanations for some of the discrepancies that have been reported in the past. The large intronic deletion that was created resulted in, at best, a two- to threefold reduction in expression of the mutated allele, and this only in certain tissues of older mice. A difference of this magnitude would be difficult to detect in a comparison of two different tissues by a procedure such as RNase protection since, in this method, variations in measurements of replicate samples tend to be very high (35, 53). The recognition that the influence of the intron can be age dependent makes it imperative that the age of mice used in studies of this sort be carefully controlled and that expression be monitored as a function of age, a practice which has not always been followed. Finally, the finding that cultured cells derived from adult lung express the intron-deleted allele to an extent similar to the extent they express the wild-type allele, whereas this is not the case in the tissue, emphasizes the limitations of cell transfection and subsequent cell culture as a means of evaluating the regulation of transcription of the Col1A1 gene. However, since lung is a heterogeneous tissue in which many cells (smooth muscle, mesothelial, endothelial, and type II alveolar epithelial cells, as well as fibroblasts) are capable of type I collagen synthesis (5, 21), it is possible that the conditions used to derive cells from lung in our study favored the growth of cells which are less subject to regulation by the first intron. In addition, levels of expression of type I collagen genes are known to differ greatly between cells grown as a monolayer and cells grown within a collagen gel (17, 32). Growth of adult lung cells within a collagen gel might therefore restore the dependence of these cells on an intact intron for maximum expression of Col1A1.

In many ways the Col-IntΔ allele is uniquely suited to evaluate the effects of the intron on expression of the Col1A1 gene since the intronic deletion occurs in the context of an otherwise wild-type locus. However, our studies would be unable to detect redundant elements that are present both within the intron and elsewhere in the gene. Such redundancy could account for the finding that a promoter-reporter transgene with a deletion in the first intron was poorly expressed in skin (35), whereas a requirement for the deleted sequence in skin was not found when a Col1A1 minigene was tested in transgenic mice (54) or in this study. Recently, indirect evidence was, in fact, obtained in stably transfected cells for an enhancer in the body of the Col1A1 gene (11). In addition, the deletion tested in our study was a large one which very likely includes many potential cis-acting elements. Some of these elements have been tested individually or as part of shorter sequences in cell transfection studies, and both positively and negatively acting elements have been identified (2, 6, 26, 29, 33, 34, 52; see reference 8 for a review). The phenotype identified thus far in homozygous Col-IntΔ mice may therefore reflect the net result of deleting multiple elements with opposing effects on transcription. It is possible that more discrete deletions will reveal effects that differ in magnitude and in cell and tissue specificity.

Recently, in a study involving two populations of British women, reduced bone mineral density and a tendency for osteoporotic fractures were shown to be associated with a polymorphic (G→T) Sp1-binding site in the first intron of the human Col1A1 gene (22). The polymorphism is predicted to reduce significantly the affinity of binding of Sp1 to the site. This finding, if confirmed, would provide additional evidence for a function of the first intron of Col1A1 in modulating tissue-specific expression of the gene. However, although this Sp1 site is located in a region of the intron that is well conserved between mice and humans (our observation), physiological differences between the two species, and the possibility that a point mutation and a large deletion may have different consequences, make it unlikely that homozygous Col-IntΔ mice will develop osteoporosis.

Although different methods have been used to introduce mutations into the murine genome (3, 19, 23, 25, 55, 58, 59), relatively few studies have utilized gene-targeting techniques to examine regulatory sequences in the mouse (7, 20, 37, 50, 57). Reports by Fiering et al. (20) and McDevitt et al. (37) evaluated the importance of transcriptional elements for expression, whereas those by Takeda et al. (57), Serwe and Sablitzky (50), and Bories et al. (7) evaluated the role of transcriptional enhancer elements in controlling rearrangements in immunoglobulin genes. Interestingly, in most of these studies an inhibitory effect of the integrated Neor gene on transcription of the targeted gene was observed. Thus, the above-named studies illustrate the importance of using gene-targeting methods, such as double replacement, which do not otherwise perturb the endogenous gene. In this regard, it seems possible that the insertion of the 9-kbp MMLV 19 bp downstream from the 5′ splice site in the first intron of the Col1A1 gene in homozygous Mov 13 mice (24, 31, 47) inhibits transcription of the gene as a consequence of the transcriptional activity of the MMLV genome. However, this possibility seems unlikely in view of evidence for increased methylation and altered chromatin conformation of Col1A1 sequences flanking the proviral insertion (12, 27, 43).

In conclusion, we have shown that the generation of a targeted, mutated allele containing both an altered, putative regulatory element, and a change in a restriction endonuclease sequence within an exon, can be used to determine the contribution of the regulatory sequence to the expression of the gene. Our findings confirm a role for the first intron in regulation of expression of the Col1A1 gene.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by grant AR11248 from the National Institutes of Health, by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Arthritis Foundation awarded to S.H., and by a grant from the Academy of Finland to R.P.

We thank Katherine Kafer and Jessie Dausman for assistance with blastocyst injections and generation of chimeric mice, Tom Doetschman for the HPRT gene construct and the E14TG2a ES cells, Serena Lo, Kim Yeargin, Bobby Bridgforth, and Patricia Jun for technical assistance, Sean Kim for animal care, and Diane Martin for assistance with illustrations. We also thank Helene Sage and members of the Bornstein laboratory for helpful discussions and comments on the manuscript. P.B. is indebted to Hong Wu and Xin Liu for making mouse 129 genomic α1(I) collagen clones available to this project and for assistance with gene targeting during the early phases of this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams S L. Collagen gene expression. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1989;1:161–168. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/1.3.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armendariz-Borunda J, Simkevich C P, Roy N, Raghow R, Kang A H, Seyer J M. Activation of Ito cells involves regulation by AP-1 binding proteins and induction of type I collagen gene expression. Biochem J. 1994;304:817–824. doi: 10.1042/bj3040817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Askew G R, Doetschman T, Lingrel J B. Site-directed point mutations in embryonic stem cells: a gene-targeting tag-and-exchange strategy. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:4115–4124. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.7.4115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bedalov A, Breault D T, Sokolov B P, Lichtler A C, Bedalov I, Clark S H, Mack K, Khillan J S, Woody C O, Kream B E, Rowe D W. Regulation of the α1(I) collagen-producing cells in transgenic animals and cultured cells. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:4903–4909. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bienkowski R S, Gotkin M G. Control of collagen deposition in mammalian lung. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1995;209:118–140. doi: 10.3181/00379727-209-43886a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boast S, Su M W, Ramirez F, Sanchez M, Avvedimento E V. Functional analysis of cis-acting DNA sequences controlling transcription of the human type-1 collagen genes. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:13351–13356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bories J C, Demengeot J, Davidson L, Alt F W. Gene-targeted deletion and replacement mutations of the T-cell receptor β-chain enhancer: the role of enhancer elements in controlling V(D)J recombination accessibility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7871–7876. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bornstein P. Regulation of expression of the α1(I) collagen gene: a critical appraisal of the role of the first intron. Matrix Biol. 1996;15:3–10. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(96)90121-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bornstein P, McKay J, Devarayalu S, Cook S C. Interactions between the promoter and first intron are involved in transcriptional control of α1(I) collagen gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;18:4851–4857. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.11.4851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bornstein P, Sage H. Regulation of collagen gene expression. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1989;37:66–106. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60695-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Breault D T, Lichtler A C, Rowe D W. COL1A1 transgene expression in stably transfected osteoblastic cells: relative contributions of first intron, 3′-flanking sequences, and sequences derived from the body of the human COL1A1 minigene. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:31241–31250. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.50.31241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Breindl M, Harbers K, Jaenisch R. Retrovirus-induced lethal mutation in collagen I gene of mice is associated with an altered chromatin structure. Cell. 1984;38:9–16. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90521-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brenner D A, Westwick J, Breindl M. Type I collagen gene regulation and the molecular pathogenesis of cirrhosis. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:589–595. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1993.264.4.G589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brenner D A, Rippe R A, Rhodes K, Trotter J F, Breindl M. Fibrogenesis and type I collagen gene regulation. J Lab Clin Med. 1994;124:755–760. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bronson S K, Smithies O. Altering mice by homologous recombination using embryonic stem cells. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:27155–27158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chomczynski P, Sacchi M. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clark R A F, Nielsen L D, Welch M P, McPherson J M. Collagen matrices attenuate the collagen-synthetic response of cultured fibroblasts to TGF-β. J Cell Sci. 1995;108:1251–1261. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.3.1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Crombrugghe B, Vuorio T, Karsenty G. Control of type I collagen genes in scleroderma and normal fibroblasts. Rheum Dis Clin N Am. 1990;16:109–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Detloff P J, Lewis J, John S W, Shehee W R, Langenbach R, Maeda N, Smithies O. Deletion and replacement of the mouse adult beta-globin genes by a “plug and socket” repeated targeting strategy. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:6936–6943. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.10.6936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fiering S, Epner E, Robinson K, Zhuang Y, Telling A, Hu M, Martin D I K, Enver T, Ley T J, Groudine M. Targeted deletion of 5′ HS2 of the murine β-globin LCR reveals that it is not essential for proper regulation of the β-globin locus. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2203–2213. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.18.2203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldstein R H. Control of type I collagen formation in the lung. Am J Physiol. 1991;261:L29–L40. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1991.261.2.L29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grant S F A, Reid D M, Blake G, Herd R, Fogelman I, Ralston S H. Reduced bone density and osteoporosis associated with a polymorphic SP1 binding site in the collagen type I α1 gene. Nat Genet. 1996;14:203–205. doi: 10.1038/ng1096-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gu H, Marth J D, Orban P C, Mossmann H, Rajewsky K. Deletion of a DNA polymerase b gene segment in T cells using cell type-specific gene targeting. Science. 1994;265:103–106. doi: 10.1126/science.8016642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hartung S, Jaenisch R, Breindl M. Retrovirus insertion inactivates mouse α1(I) collagen gene by blocking initiation of transcription. Nature. 1986;320:365–367. doi: 10.1038/320365a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hasty P, Ramirez-Solis R, Krumlauf R, Bradley A. Introduction of a subtle mutation into the hos 2.6 locus in embryonic stem cells. Nature. 1991;350:243–246. doi: 10.1038/350243a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Houglum K, Buck M, Alcorn J, Contreras S, Bornstein P, Chojkier M. Two different cis-acting regulatory regions direct cell-specific transcription of the collagen α1(I) gene in hepatic stellate cells and in skin and tendon fibroblasts. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:2269–2276. doi: 10.1172/JCI118282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jähner D, Jaenisch R. Retrovirus-induced de novo methylation of flanking host sequences correlates with gene inactivity. Nature. 1985;315:594–597. doi: 10.1038/315594a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karsenty G, Park R W. Regulation of type I collagen genes expression. Int Rev Immunol. 1995;12:177–185. doi: 10.3109/08830189509056711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Katai H, Stephenson J D, Simkievich C P, Thompson J P, Raghow R. An AP-1 like motif in the first intron of human pro α1(I) collagen gene is a critical determinant of its transcriptional activity. Mol Cell Biochem. 1992;118:119–129. doi: 10.1007/BF00299391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kratochwil K, Ghaffari-Tabrizi N, Holzinger I, Harbers K. Restricted expression of Mov13 mutant α1(I) collagen gene in osteoblasts and its consequences for bone development. Dev Dyn. 1993;198:273–283. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001980405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kratochwil K, von der Mark K, Kollar E J, Jaenisch R, Mooslehner K, Schwarz M, Haase K, Gmachl I, Harbers K. Retrovirus-induced insertional mutation in Mov 13 mice affects collagen I expression in a tissue-specific manner. Cell. 1989;57:807–816. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90795-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Langholz O, Röckel D, Mauch C, Kozlowska E, Bank I, Krieg T, Eckes B. Collagen and collagenase gene expression in three-dimensional collagen lattices are differentially regulated by α1β1 and α2β1 integrins. J Cell Biol. 1995;131:1903–1915. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.6.1903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liska D J, Slack J L, Bornstein P. A highly conserved intronic sequence is involved in transcriptional regulation of the α1(I) gene. Cell Regul. 1990;1:487–498. doi: 10.1091/mbc.1.6.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liska D J, Robinson V R, Bornstein P. Elements in the first intron of the α1(I) collagen gene interact with SpI to regulate gene expression. Gene Expr. 1992;2:379–389. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liska D J, Reed M J, Sage E H, Bornstein P. Cell-specific expression of α1(I) collagen-hGH minigenes in transgenic mice. J Cell Biol. 1994;125:695–704. doi: 10.1083/jcb.125.3.695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu X, Wu H, Loring J, Hormuzdi S, Disteche C M, Bornstein P, Jaenisch R. Trisomy eight in ES cells is a common potential problem in gene targeting and interferes with germ line transmission. Dev Dyn. 1997;209:85–91. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199705)209:1<85::AID-AJA8>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McDevitt M A, Shivdasani R A, Fujiwara Y, Yang H, Orkin S H. A “knockdown” mutation created by cis-element gene targeting reveals the dependence of erythroid cell maturation on the level of transcription factor GATA-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:6781–6785. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.13.6781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Melton D W. Gene targeting in the mouse. Bioessays. 1994;16:633–638. doi: 10.1002/bies.950160907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moore R C, Redhead N J, Selfridge J, Hope J, Manson J C, Melton D. Double replacement gene targeting for the production of a series of mouse strains with different prion protein gene alterations. Bio/Technology. 1995;13:999–1004. doi: 10.1038/nbt0995-999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Olsen A S, Geddis A E, Prockop D J. High levels of expression of a minigene version of the human pro-α1(I) collagen gene in stably transfected mouse fibroblasts: effects of deleting putative regulatory sequences in the first intron. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:1117–1121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pavlin D, Lichtler A C, Bedalov A, Kream B E, Harrison J R, Thomas H F, Gronowicz G A, Clark S H, Woody C O, Rowe D W. Differential utilization of regulatory domains within the α1(I) collagen promoter in osseous and fibroblastic cells. J Cell Biol. 1992;116:227–236. doi: 10.1083/jcb.116.1.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ramirez F, Di Liberto M. Complex and diversified regulatory programs control the expression of vertebrate collagen genes. FASEB J. 1990;4:1616–1623. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.4.6.2180769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rhodes K, Rippe R A, Umezawa A, Nehls M, Brenner D A, Breindl M. DNA methylation represses the murine α1(I) collagen promoter by an indirect mechanism. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:5950–5960. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.9.5950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rippe R A, Lorenzen S-I, Brenner D A, Breindl M. Regulatory elements in the 5′-flanking region and the first intron contribute to transcriptional control of the mouse alpha 1 type I collagen gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:2224–2227. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.5.2224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rossert J, Eberspaecher H, de Crombrugghe B. Separate cis-acting DNA elements of the mouse pro-α1(I) collagen promoter direct expression of reporter genes to different type I collagen-producing cells in transgenic mice. J Cell Biol. 1995;129:1421–1432. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.5.1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rossert J A, Garrett L A. Regulation of type I collagen synthesis. Kidney Int. 1995;47:S34–S38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schnieke A, Harbers K, Jaenisch R. Embryonic lethal mutation in mice induced by retrovirus insertion into the α1(I) collagen gene. Nature. 1983;304:315–320. doi: 10.1038/304315a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schwarz M, Harbers K, Kratochwil K. Transcription of a mutant collagen I gene is a cell type and stage-specific marker for odontoblast and osteoblast differentiation. Development. 1990;108:717–726. doi: 10.1242/dev.108.4.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Selfridge J, Pow A M, McWhir J, Magin T M, Melton D W. Gene targeting using a mouse HPRT minigene/HPRT-deficient embryonic stem cell system: inactivation of the mouse ERCC-1 gene. Somatic Cell Mol Genet. 1992;18:325–336. doi: 10.1007/BF01235756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Serwe M, Sablitzky F. V(D)J recombination in B cells is impaired but not blocked by targeted deletion of the immunoglobulin heavy chain intron enhancer. EMBO J. 1993;12:2321–2327. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05886.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Slack J L, Liska D J, Bornstein P. An upstream regulatory region mediates high-level, tissue-specific expression of the human α1(I) collagen gene in transgenic mice. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:2066–2074. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.4.2066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Slack J L, Parker M I, Bornstein P. Transcriptional repression of the α1(I) collagen gene by ras is mediated in part by an intronic AP1 site. J Cell Biochem. 1995;58:380–392. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240580311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sokolov B P, Mays P K, Khillan J S, Prockop D J. Tissue- and development-specific expression in transgenic mice of a type I procollagen (COL1A1) minigene construct with 2.3 kb of the promoter region and 2 kb of the 3′-flanking region. Specificity is independent of the putative regulatory sequences in the first intron. Biochemistry. 1993;32:9242–9249. doi: 10.1021/bi00086a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sokolov B P, Ala-Kokko L, Dhulipala R, Arita M, Khillan J S, Prockop D J. Tissue specific expression of the gene for type I procollagen (COL1A1) in transgenic mice: only 476 base pairs of the promoter are required if collagen genes are used as reporters. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:9622–9629. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.16.9622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stacey A, Schnieke A, McWhir J, Cooper J, Colman A, Melton D W. Use of double-replacement gene targeting to replace the murine α-lactalbumin gene with its human counterpart in embryonic stem cells and mice. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:1009–1016. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.2.1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sun Z, Means A R. An intron facilitates activation of the calspermin gene by the testis-specific transcription factor CREMτ. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:20962–20967. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.36.20962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Takeda S, Zou Y-R, Bluethmann H, Kitamura D, Muller U, Rajewsky K. Deletion of the immunoglobulin κ chain intron enhancer abolishes κ chain gene rearrangement in cis but not λ chain gene rearrangement in trans. EMBO J. 1993;12:2329–2336. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05887.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Valancius V, Smithies O. Testing an “in-out” targeting procedure for making subtle genomic modifications in mouse embryonic stem cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:1402–1408. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.3.1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wu H, Liu X, Jaenisch R. Double replacement: strategy for efficient introduction of subtle mutations into the murine Col1A1 gene by homologous recombination in embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:2819–2823. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.7.2819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]