Abstract

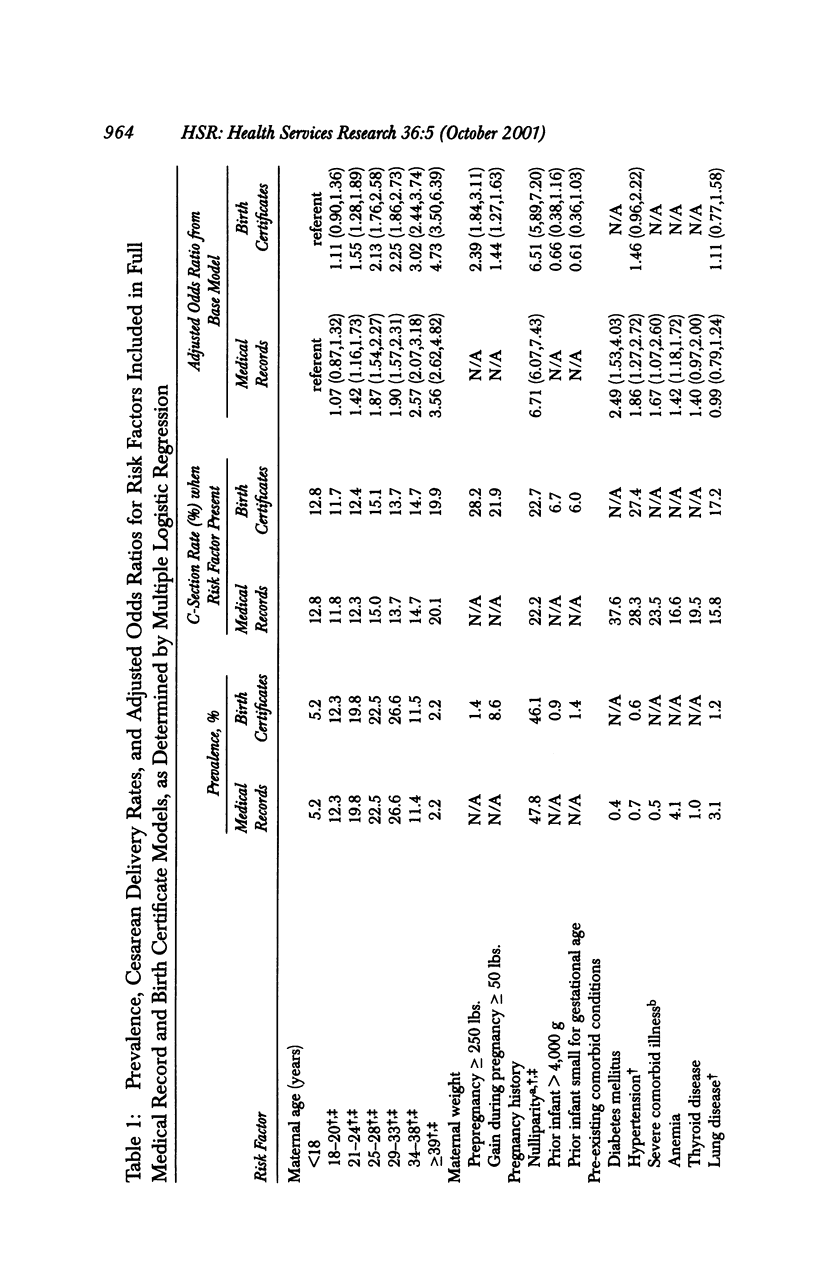

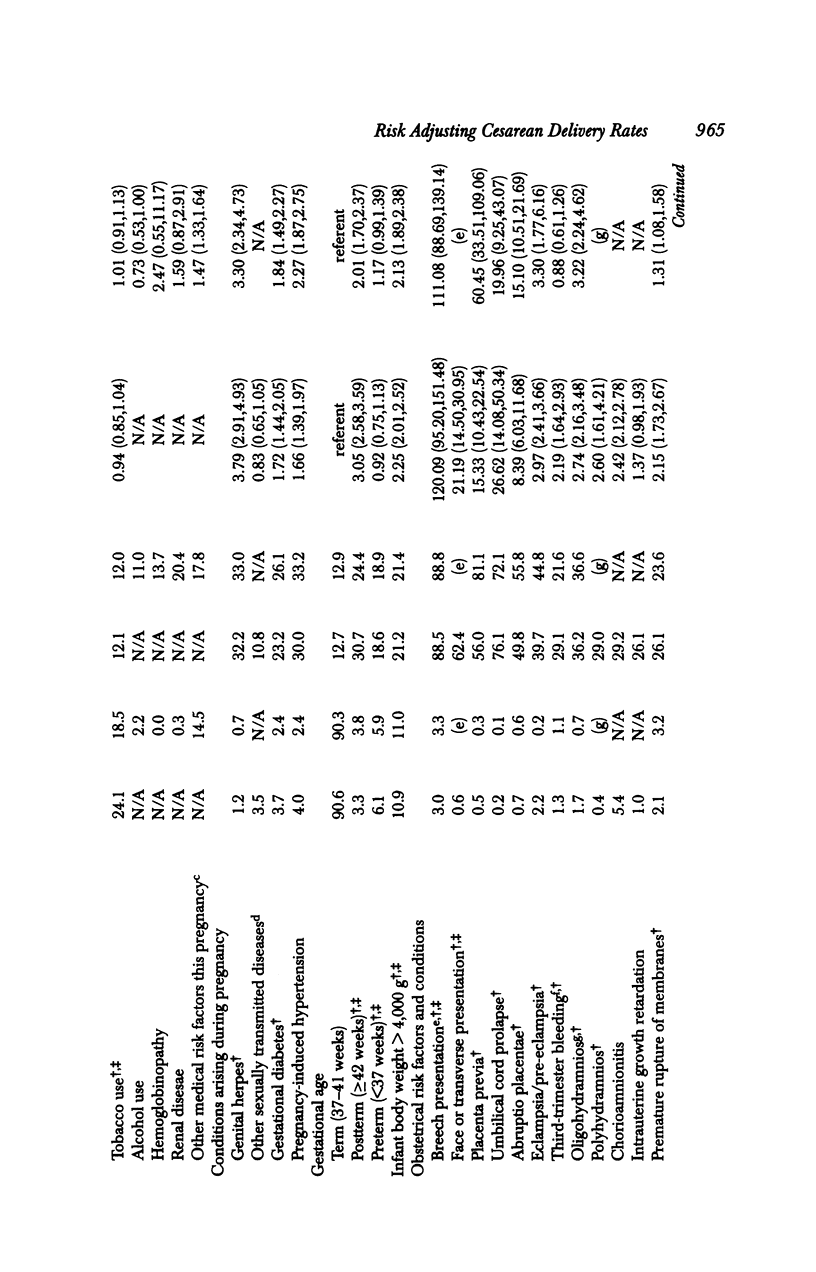

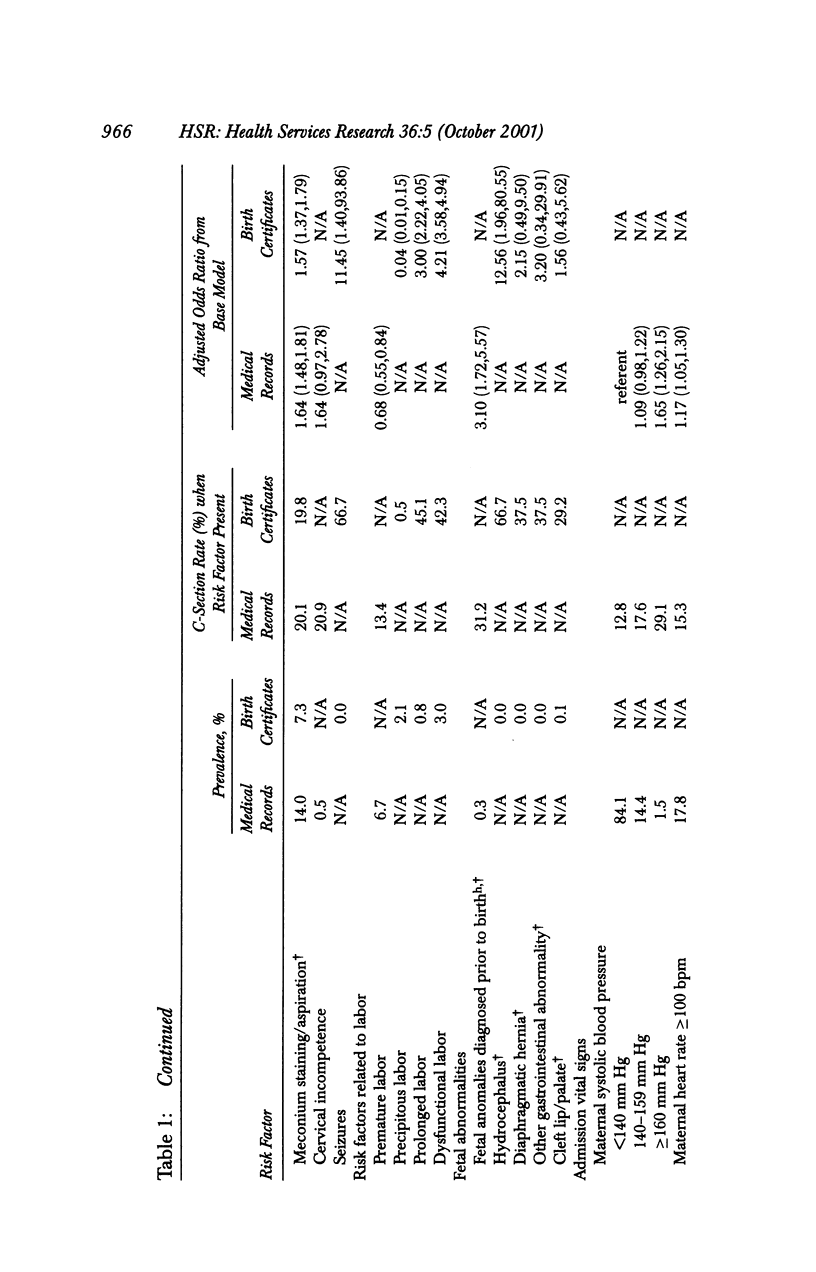

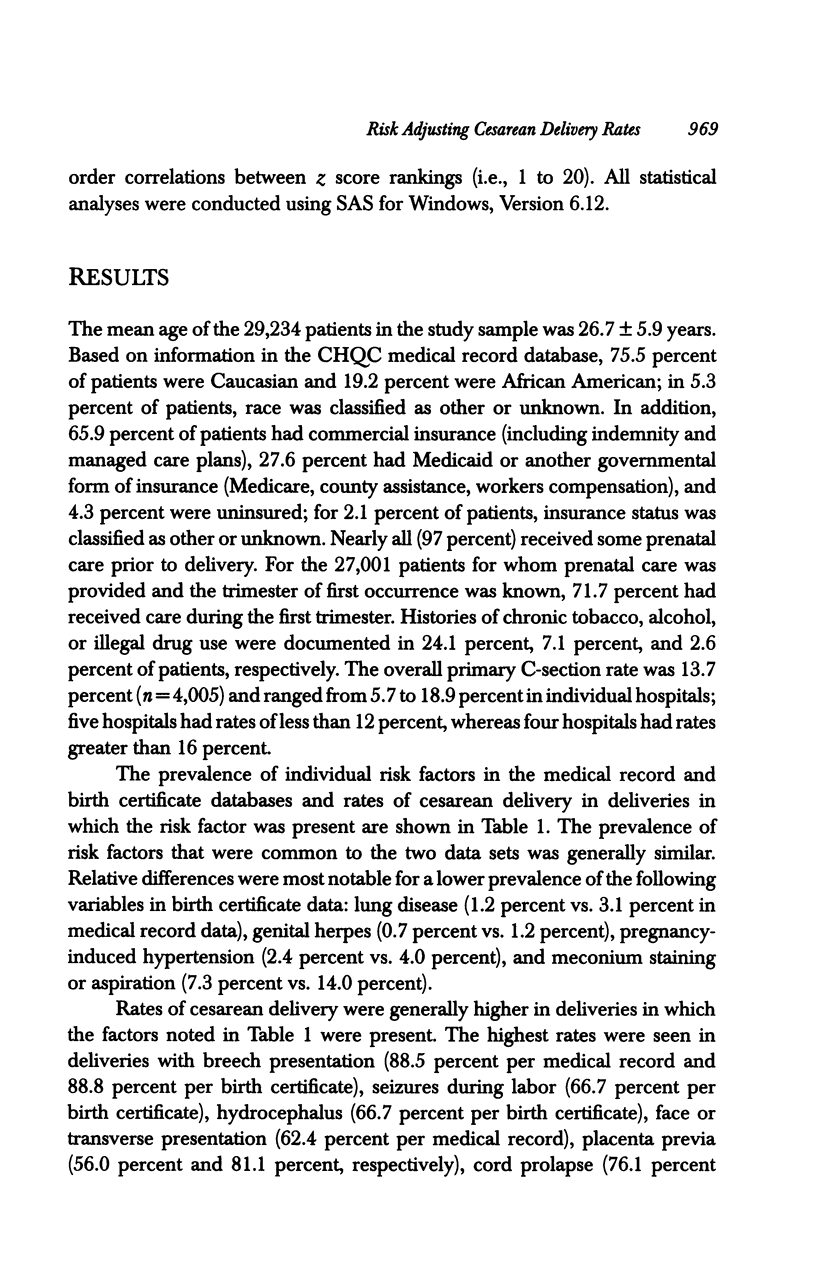

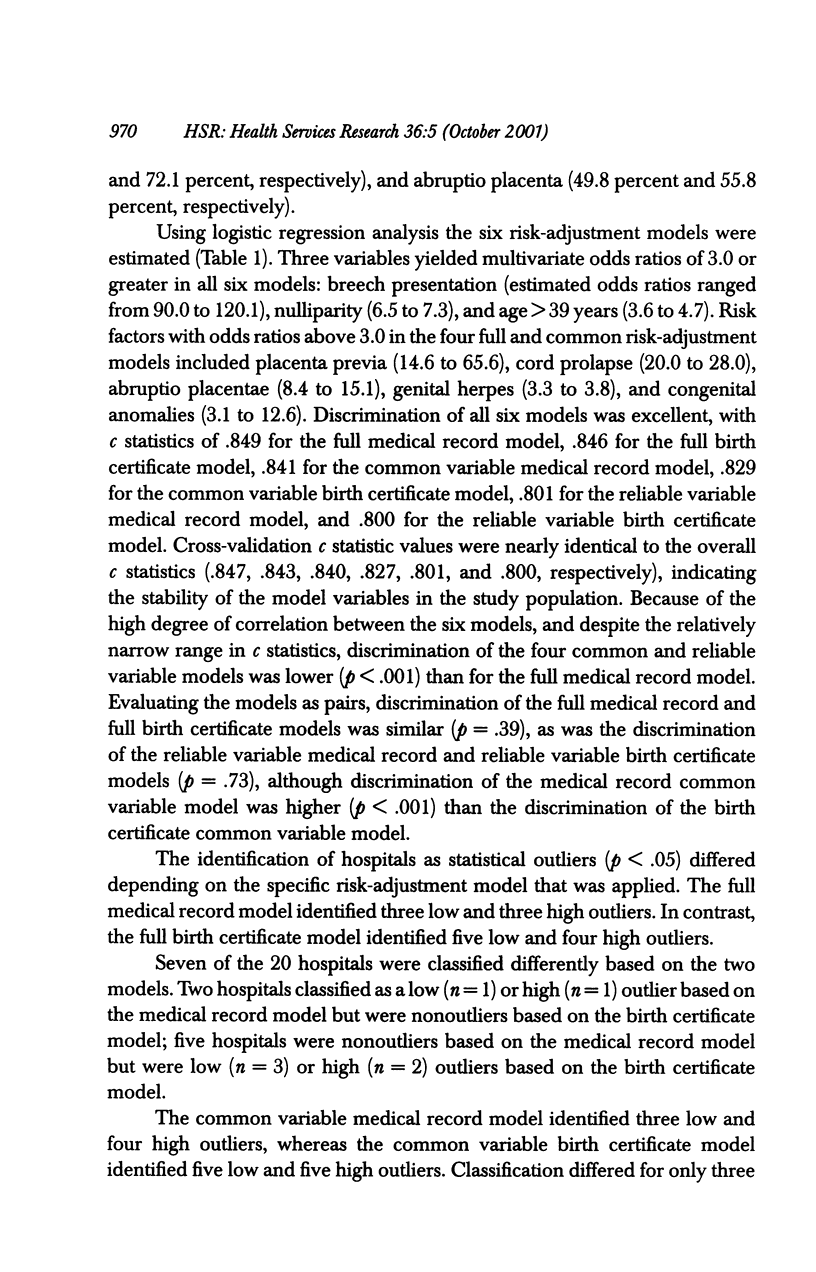

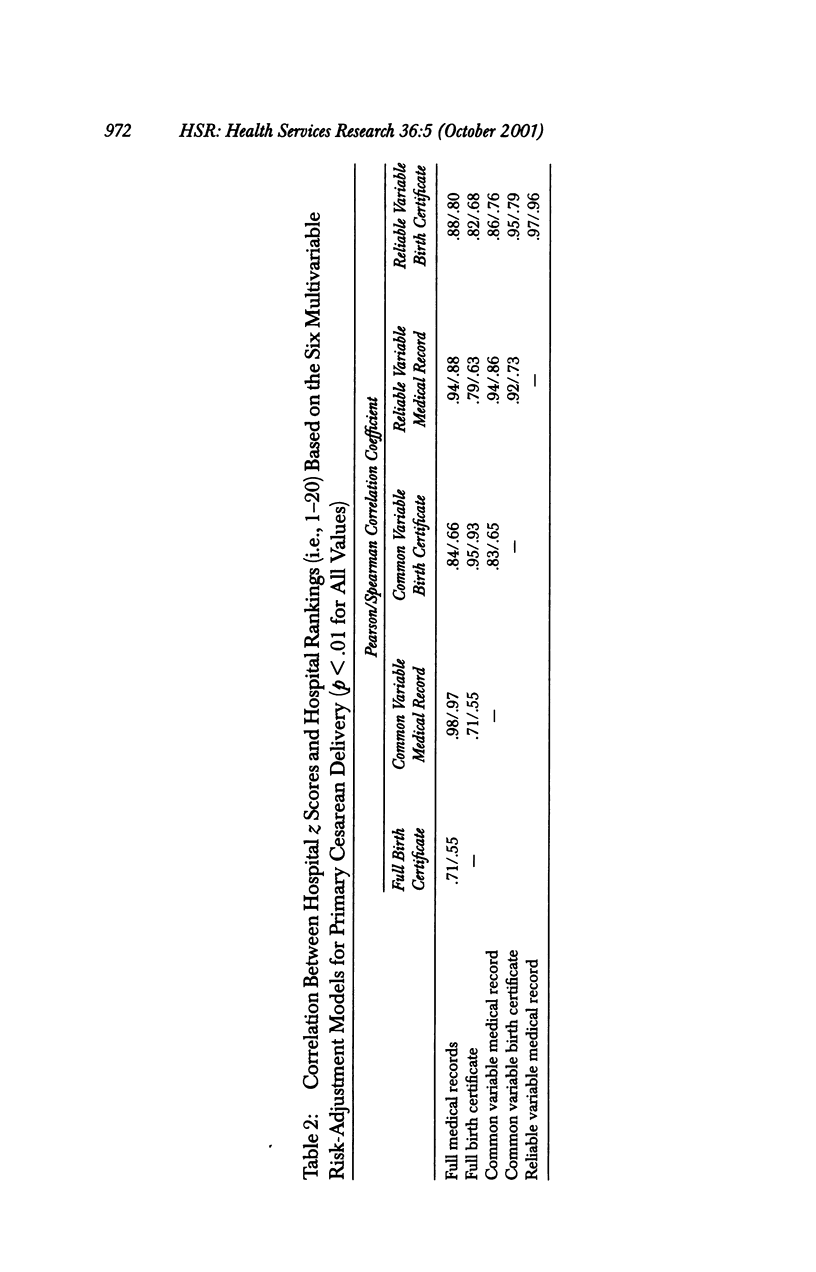

OBJECTIVES: Compare the discrimination of risk-adjustment models for primary cesarean delivery derived from medical record data and birth certificate data and determine if the two types of models yield similar hospital profiles of risk-adjusted cesarean delivery rates. DATA SOURCES/STUDY SETTING: The study involved 29,234 women without prior cesarean delivery admitted for labor and delivery in 1993-95 to 20 hospitals in northeast Ohio for whom data abstracted from patient medical records and data from birth certificates could be linked. STUDY DESIGN: Three pairs of multivariate models of the risk of cesarean delivery were developed using (1) the full complement of variables in medical records or birth certificates; (2) variables that were common to the two sources; and (3) variables for which agreement between the two data sources was high. Using each of the six models, predicted rates of cesarean delivery were determined for each hospital. Hospitals were classified as outliers if observed and predicted rates of cesarean delivery differed (p < .05). PRINCIPAL FINDINGS: Discrimination of the full medical record and birth certificate models was higher (p < .001) than the discrimination of the more limited common and reliable variable models. Based on the full medical record model, six hospitals were classified as statistical (p < .01) outliers (three high and three low). In contrast, the full birth certificate model identified five low and four high outliers, and classifications differed for seven of the 20 hospitals. Even so, the correlation between adjusted hospital rates was substantial (r = .71). Interestingly, correlations between the full medical record model and the more limited common (r = .84) and reliable (r = .88) variable birth certificate models were higher, and differences in classification of hospital outlier status were fewer. CONCLUSION: Birth certificates can be used to develop cesarean delivery risk-adjustment models that have excellent discrimination. However, using the full complement of birth certificate variables may lead to biased hospital comparisons. In contrast, limiting models to data elements with known reliability may yield rankings that are more similar to rankings based on medical record data.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Aron D. C., Harper D. L., Shepardson L. B., Rosenthal G. E. Impact of risk-adjusting cesarean delivery rates when reporting hospital performance. JAMA. 1998 Jun 24;279(24):1968–1972. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.24.1968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailit J. L., Dooley S. L., Peaceman A. N. Risk adjustment for interhospital comparison of primary cesarean rates. Obstet Gynecol. 1999 Jun;93(6):1025–1030. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00536-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berwick D. M. The double edge of knowledge. JAMA. 1991 Aug 14;266(6):841–842. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berwick D. M., Wald D. L. Hospital leaders' opinions of the HCFA mortality data. JAMA. 1990 Jan 12;263(2):247–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buescher P. A., Taylor K. P., Davis M. H., Bowling J. M. The quality of the new birth certificate data: a validation study in North Carolina. Am J Public Health. 1993 Aug;83(8):1163–1165. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.8.1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley J. A., McNeil B. J. A method of comparing the areas under receiver operating characteristic curves derived from the same cases. Radiology. 1983 Sep;148(3):839–843. doi: 10.1148/radiology.148.3.6878708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iezzoni L. I., Ash A. S., Shwartz M., Daley J., Hughes J. S., Mackiernan Y. D. Predicting who dies depends on how severity is measured: implications for evaluating patient outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 1995 Nov 15;123(10):763–770. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-10-199511150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iezzoni L. I., Shwartz M., Ash A. S., Hughes J. S., Daley J., Mackiernan Y. D. Severity measurement methods and judging hospital death rates for pneumonia. Med Care. 1996 Jan;34(1):11–28. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199601000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iezzoni L. I., Shwartz M., Ash A. S., Mackiernan Y. D. Predicting in-hospital mortality for stroke patients: results differ across severity-measurement methods. Med Decis Making. 1996 Oct-Dec;16(4):348–356. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9601600405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landon B., Iezzoni L. I., Ash A. S., Shwartz M., Daley J., Hughes J. S., Mackiernan Y. D. Judging hospitals by severity-adjusted mortality rates: the case of CABG surgery. Inquiry. 1996 Summer;33(2):155–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrish K. M., Holt V. L., Connell F. A., Williams B., LoGerfo J. P. Variations in the accuracy of obstetric procedures and diagnoses on birth records in Washington State, 1989. Am J Epidemiol. 1993 Jul 15;138(2):119–127. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pine M., Norusis M., Jones B., Rosenthal G. E. Predictions of hospital mortality rates: a comparison of data sources. Ann Intern Med. 1997 Mar 1;126(5):347–354. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-5-199703010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper J. M., Mitchel E. F., Jr, Snowden M., Hall C., Adams M., Taylor P. Validation of 1989 Tennessee birth certificates using maternal and newborn hospital records. Am J Epidemiol. 1993 Apr 1;137(7):758–768. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal G. E., Harper D. L. Cleveland health quality choice: a model for collaborative community-based outcomes assessment. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 1994 Aug;20(8):425–442. doi: 10.1016/s1070-3241(16)30088-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaller D. V., Woods P. Reforming the market for value in health care: the Cleveland experience. J Occup Med. 1991 Mar;33(3):358–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starr P., Starr S. Reinventing vital statistics. The impact of changes in information technology, welfare policy, and health care. Public Health Rep. 1995 Sep-Oct;110(5):534–544. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeglen M. Accreditation requirements for ORYX: the next evolution in accreditation. J AHIMA. 1997 Jun;68(6):20-2, 24-31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]