Abstract

Dysmenorrhea, affecting approximately 80% of adolescents, significantly impairs quality of life, disrupts sleep patterns, and induces mood changes. Furthermore, its economic impact is substantial, accounting for an estimated $200 billion in the United States and $4.2 million in Japan annually. This review aimed to identify the effects of vitamin D and calcium on primary dysmenorrhea. We conducted a comprehensive literature search across Web of Science, PubMed, Scopus, and Science Direct, focusing on studies published from 2010 to 2020. Keywords included 'primary dysmenorrhea', 'vitamin D', '25-OH vitamin D3', 'cholecalciferol', and 'calcium'. The quality assessment of the articles was done using the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) and the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklists, and the risk bias was assessed using the Cochrane assessment tool. Abnormal low Vit. D levels increased the severity of primary dysmenorrhea through increased prostaglandins and decreased calcium absorption. Vitamin D and calcium supplements could reduce the severity of primary dysmenorrhea and the need for analgesics. This systematic review found an inverse relation between the severity of dysmenorrhea and low serum Vit. D and calcium.. Vitamin D and calcium supplements could reduce the severity of primary dysmenorrhea and the need for analgesics.

Keywords: Calcium, dysmenorrhea, vitamin D

ABBREVIATIONS: 25-OH Vit. D3: 25-Hydroxyvitamin D3, BMI: Body Mass Index, Ca: Calcium, IU: International Unit, NRS: Numeric Rating Scale, NSAIDs: Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs, PGDs: Prostaglandins, PTH: Parathyroid Hormone, VAS: Visual Analogue Scale, VDR: Vitamin D Receptor, VIPS: Verbal Intensity Pain Scale, Vit. D: Vitamin D, Vit. E: Vitamin E

INTRODUCTION

Dysmenorrhea, characterized by lower abdominal pain occurring just before and sometimes lasting hours after menstruation, often presents alongside symptoms like nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, insomnia, and irritability [1, 2]. This condition affects 80% of adolescents [3-5]. Primary dysmenorrhea occurs in the absence of any pelvic pathology [6], while secondary dysmenorrhea is usually associated with pelvic pathologies (i.e., endometriosis and/or adenomyosis) [7]. Primary dysmenorrhea is primarily attributed to increased local prostaglandin (PGD) levels [8-11], impacting quality of life, sleep patterns, and mood [12]. Dysmenorrhea negatively affects the quality of life and contributes to a disturbed sleep pattern and mood changes [12]. Furthermore, dysmenorrhea imposes a substantial economic burden, costing $200 billion annually in the United States and $4.2 million in Japan [11].

The usual treatment of dysmenorrhea includes non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and oral contraceptives [13, 14]. While NSAIDs decrease the severity of dysmenorrhea by inhibiting PGD synthesis, they increase the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding and gastric ulcers [15, 16]. There is little evidence regarding the efficacy of oral contraceptives in the treatment of dysmenorrhea, and 50% of women stopped oral contraceptives prescribed for the treatment of their dysmenorrhea because of their side effects [17].

The treatment of dysmenorrhea with therapeutic options other than NSAIDs and oral contraceptives could be helpful and limit the use of NSAIDs and oral contraceptives. Understanding the presence of vitamin D receptor in the uterus and ovaries [18] highlights the role of Vit. D in regulating inflammatory cytokines [19]. Vit. D metabolites could reduce the level of inflammatory cytokines [20, 21]. Inverse relationships between the severity of dysmenorrhea and serum Vit. D and calcium (Ca) were reported in a systematic review [11]. In addition, Karacin et al. [22] found a significant negative association between dysmenorrhea and Vit. D. Kucukceran et al. [23] reported a significant reduction in menstrual pain and consumed NSAIDs after a single dose of oral cholecalciferol compared to placebo. A randomized trial reported reduced severity of dysmenorrhea after Vit. D intake [8] and Zarei et al. [24] reported a significant reduction in menstrual pain after Ca intake. Consequently, this review aimed to assess the impact of Vit. D and Ca on primary dysmenorrhea.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

A comprehensive search was conducted across Web of Science, PubMed, Scopus, and Science Direct, focusing on articles/studies published between 2010 and 2020 containing keywords such as "primary dysmenorrhea", "painful menses", and "Vit. D", "Vit. D3", "25-OH Vit. D3", or "cholecalciferol", and "Ca". The objective was to assess the impact of Vit. D and Ca in alleviating the severity of primary dysmenorrhea.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies examining vitamin D and/or calcium in primary dysmenorrhea involving non-smoking, non-alcoholic women of reproductive age with regular menses and low serum vitamin D levels and studies that included participants without a history of uterine disorders (i.e., fibroids, adenomyosis, endometrial hyperplasia or endometrial polyps) or ovarian disorders (ovarian cysts, endometriosis, or polycystic ovaries) were included in this systematic review.

Studies that included pregnant women, women with medical disorders (i.e., gastrointestinal, renal, or cardiac disorders), uterine (i.e., fibroids, adenomyosis, endometrial hyperplasia or endometrial polyps), ovarian disorders (ovarian cysts, endometriosis, or polycystic ovaries), women with previous pelvic surgery, psychological or neurological disorders, or who received hormonal therapy were excluded from this systematic review.

Study selection

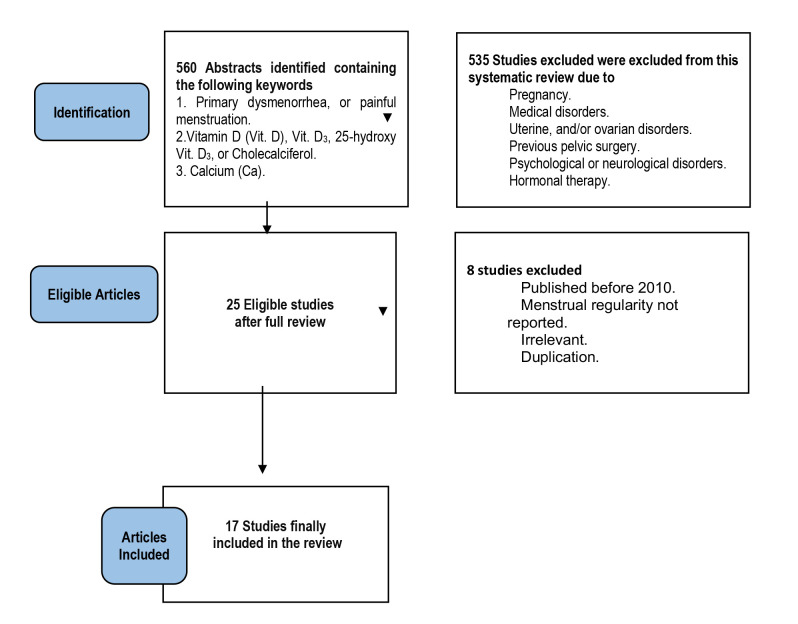

Five hundred sixty articles were initially retrieved. Eligible articles were evaluated by two independent authors (AD and IA). After reviewing the titles and abstracts of each article, 535 articles were not eligible for inclusion in this systematic review because of the above-mentioned exclusion criteria (Figure 1). After a full review (i.e., including the results and discussions) of the remaining 25 articles, another 8 articles were excluded (published before 2010, irrelevant or duplicate), and finally, 17 articles were eligible and included in this systematic review (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The PRISMA flowchart

Quality assessment

The quality assessment of the articles was done using the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) and the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklists. CONSORT is a 25-item checklist focusing on the article design, analysis, and interpretation. STROBE is a 22-item checklist evaluating different sections of the observational studies [11].

Risk bias assessment

The risk bias was assessed by two independent authors (AD and IA) using the Cochrane risk-bias assessment tool, which includes selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias, and reporting bias.

Data extraction

The following data were extracted: name of the first author, country, publication year, study design and sample size, age of participants and their age of menarche, body mass index (BMI), duration and severity of dysmenorrhea, intervention, serum Vit. D, dysmenorrhea assessment tool (i.e., visual analog scale [VAS] or numeric rating scale [NRS], or verbal intensity pain scale [VIPS]) and results.

RESULTS

Out of the 17 studies included in this systematic review, three studies were cross-sectional [25-27], one was a case-control study [22], two were semi-experimental [23, 28], and 11 were randomized controlled studies [24, 29, 30-38]. The studies were conducted in Iran (10 studies) [24-26, 28, 29, 32, 33, 35-37], Turkey (three studies) [22, 23, 30], Jordan (one study) [27], India (1 study) [34], Italy (one study) [38], and Saudi Arabia (one study) [31]. A total of 2,774 participants were included in this systematic review, with most participants having a normal BMI and a normal age of menarche.

Vitamin D and severity of dysmenorrhea

Although two studies did not find a significant relationship between serum Vit. D levels and the severity of primary dysmenorrhea [25, 27], an inverse association between serum Vit. D and the severity of primary dysmenorrhea was observed in two other studies. These studies reported that individuals with lower serum Vit. D levels experienced more severe primary dysmenorrhea symptoms [22, 26].

Effectiveness of vitamin D and calcium in reducing the severity of dysmenorrhea

Clinical studies reported that vitamin D supplementation decreased the severity of dysmenorrhea [25, 32-34, 36, 37]. A comparative study [30, 31] found vitamin D more effective than vitamin E or ginger in reducing severe dysmenorrhea symptoms. Participants receiving Vit. D supplements exhibited a higher recovery rate from primary dysmenorrhea and consumed fewer NSAIDs [32]. Zarei et al. [24] found that calcium intake was more effective than Vit. D and Ca combined in relieving severe dysmenorrhea. Charandabi et al. [33] found that Ca alone or combined with magnesium was equally effective in reducing the severity of dysmenorrhea. Furthermore, Mehrpooya et al. [32] reported that omega-3 effectively reduced the pain of primary dysmenorrhea. Table 1 shows the reviewed articles.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies included in the systematic review

| Author Country |

Design Sample size |

Age (yrs.) Menarche age (yrs.) |

BMI (Kg/m2) | Dysmenorrhea Duration (days) |

Intervention (Treatment) |

Control | Intensity of dysmenorrhea | Serum Vit. D | Assessment tool | Definition | Results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | After | Baseline | After | ||||||||||

| Rahnemaie et al. [25], Iran |

Cross-sectional 143 |

225±2.97 13.46±1.03 |

23.53±3.7 | 2.43±1.32 | - | - | 6.9±1.59 | - | 24.45±11.85 ng/mL | - | VAS | ≥4 | NS |

| Zeynali et al. [26], Iran |

Cross-sectional 372 |

22.4±2.0 13.2±1.44 | 24±3.07 | 2.18±1.04 | - | - | -Severe 24.73% -Moderate 53.22% -Mild 22.04% |

- | -Mild deficiency 37.09% -Moderate deficiency 36.5% -Severe deficiency 26.3% |

- | VAS | ≥1 | S |

| Karacin et al. [22], Turkey |

Case- control 368 |

20.80 12.15 |

22.26 | NM | - | - | 7.3±1.4 | - | 7.1±3.8 ng/mL | - | VAS | 1-10 | S |

| Abdul- Razzak et al. [27], Jordan |

Cross-sectional 56 |

21.9±2.76 13.6±1.4 |

NM | NM | - | - | -Very severe 60.7% -Severe 39.3% |

- | -Deficient 9% -Insufficient 80% -Normal 11% |

- | NRS | 0-10 | NS |

| Kucukceran et al. [23], Turkey |

Quasi experimental 100 |

20.5 13.1 |

21.4 | 2.3 | -Insufficient: 7-8 drops Vit. D3/day. -Deficient: 9-15 drops Vit. D3/day. -Severely deficient: 16–23 drops Vit. D3/day. |

- | 7.0±2.0 | 4.1±1.6 | 13.9±6.1 | 31.1±3.9 | VAS | 0-10 | S |

| Bahrami et al. [28], Iran |

Quasi experimental 897 |

14.7±1.5 12.57±1.19 |

NM | NM | High-dose cholecalciferol (50,000 IU/week), then 1 capsule over 9 weeks | - | -Mild 9.5% -Moderate 20.8% -Severe 18.1% -Very severe 12.3% -Worst 8.1% |

-Mild 11% -Moderate 19% -Severe 16.2% -Very severe 9% -Worst 7.8% |

22.7±22.6 nmol/mL | 89.9±38.3 nmoL | VIPS | 0-5 | S |

| Pakniat et al. [29], Iran |

RCT 200 |

22.44±1.9 12.55±1.0 |

21.62±3.15 | 2.6±0.89 | -Ginger Cap. 500 mg/day + mefenamic 250 mg capsule. -1,000 mg Vit. D + mefenamic 250 mg. -100 IU Vit. E + mefenamic 250 mg for 2 days before and 3 days after menses. |

Placebo + Mefenamic 250 mg |

7.13±0.8 | 4.9±1.48 | - | - | VAS | 0-10 | S |

| Ayşegül et al. [30], Turkey |

RCT 142 |

22.0 23.4±5.6 |

NM | NM | -667 IU of Vit. D/day -200 IU of Vit. E/day for 2 days before and 3 days after the menses. |

400 mg Ibuprofen twice a day |

8.5±1.2 | 4.9±2.4 | - | - | VAS | 0-10 | S for Vit. D |

| Lama et al. [31], Saudi-Arabia |

RCT 22 |

13-40 NM |

NM | NM | -50,000 IU Vit. D/week + the usual analgesics. | The usual analgesics |

7.8 | 3.6 | 30.1±13.4 nmol/L | 80.2±14.3 nmol | VAS | 0-10 | S |

| Zarei et al. [24], Iran |

RCT 85 |

23.66 13.1 |

21.8 | NM | -1,000 mg calcium (Ca) + 5,000 IU Vit. D/day -1,000 mg Ca/day from the 15th cycle day until menstrual pain disappears. |

Placebo | -Ca/Vit. D: 7.7±1.2 -Ca: 7.7±1.3 |

-Ca/Vit. D: 5.0±2.6 -Ca: 3.9±2.5 |

NM | NM | VAS | 0-10 | S for Ca |

| Mehrpooya et al. [32], Iran |

RCT 80 |

25.24 NM |

23.16 | NM | Ibuprofen 400 mg as needed. + 1,000 mg Omega-3 every day in the first cycle and 8 days of 2nd and 3rd cycles. |

Ibuprofen 400 mg. + 1,000 mg Ca |

Omega-3: 6.67±1.8 Ca: 7.5±2.7 |

Omega-3: 2.3±0.63 Ca: 3.2±1.5 |

- | - | VAS | ≥4 | S |

| Charandabi et al. [33], Iran |

RCT 61 |

21.0±2.2 12.6 |

22.3±3.0 | NM | -300 mg Magnesium + 600 mg Ca -600 mg Ca one tab./ day, from the day 15th of their cycle till the day with no menstrual pain. |

Placebo | Ca/Mg: 6.0±2.3 Ca:5.2±2.0 |

Ca/Mg: 3.9±2.1 Ca: 4.2±2.0 |

- | - | VAS | ≥5 | S |

| Fareena et al. [34], India |

RCT 50 |

21.18 62% had early onset menarche. |

-88% Normal -12% Overweight. |

NM | Single oral dose of Vit. D3 3,00,000 for 2-4 months. | Placebo | 8.76±0.97 | 3.56±0.76 | 17.84±10 ng/mL | 34.7±8.1 ng | VAS | 0-10 | S |

| Moini et al. [35], Iran |

RCT 50 |

26.36 12.72 |

22.95 | NM | 50,000 IU oral Vit. D/week | Placebo | 7.8 | 2.8 | 9.69±5.09 ng/mL | 55.4±6.02 ng | VAS | 0-10 | S |

| Ataee et al. [36], Iran |

RCT 54 |

NM | NM | NM | Single oral dose cholecalciferol (300,000 IU) 5 days before the start of menses for 2 cycles. |

Placebo | 7.53±1.85 | 3.77±1.77 | 7.28±3.64 ng/mL | - | VAS | 0-10 | S |

| Zangene et al. [37], Iran |

RCT 54 |

22.43 NM |

21.03 | NM | Single high oral dose Cholecalciferol (300,000 IU) for 5 days before the onset of menses for 3 cycles. | Placebo | 7.53±1.85 | 3.77±1.78 | 7.37 ng/mL | NM | VAS | 0-10 | S |

| Lasco et al. [38], Italy |

RCT 40 |

26.65 NM |

21.56 | NM | Single oral dose cholecalciferol (300,000 IU/mL) for 5 days before the start of menses for 2 cycles. |

Placebo | 5.85±2.0 | 3.50±1.27 | 27.19±7.5 ng/mL | - | VAS | 0-10 | S |

BMI: Body mass index. Ca: Calcium. Mg: Magnesium. IU: International unit. NM: Not mentioned. NRS: numeric rating scale. NS: Non-significant. RCT: Randomized controlled trial. S: Significant. VAS: Visual analogue scale. a: verbal intensity pain scale. Vit. D: Vitamin D. Vit. E: Vitamin E.

Interventions/treatment and duration

The forms of vitamin D used in the clinical studies included in this review were drops or capsules of 100 mg, 667 IU, 50,000 IU, or 300,000 IU. Calcium was used in the form of capsules in clinical studies included in this review. The intervention/treatment duration varied across studies, ranging from 4 to 12 weeks.

The parathyroid hormone (PTH) and other biochemical markers in dysmenorrhea

Serum Ca and PTH were evaluated in four studies [22, 23, 27, 33]. One study reported significantly lower serum Ca levels and higher PTH levels in the primary dysmenorrhea group compared to controls. In another study, serum Ca and PTH levels were measured in three groups categorized by Vit. D status (insufficient Vit. D (21-29 ng/mL), deficient Vit. D (10-20 ng/mL), and severely deficient Vit. D (<10 ng/mL)), and no significant differences were found in serum Ca and phosphorus levels between the groups before or after Vit. D treatment. In addition, PTH significantly decreased from 42.2±17.4 pg/mL before Vit. D treatment to 28.5±11.0 pg/mL after Vit. D treatment (p<0.001) [23].

Another study investigated vitamin D, calcium, and PTH in adolescents with severe/very severe dysmenorrhea and found that 82.1% of the studied participants had normal serum Ca, 80.4% had normal alkaline phosphatase and 48.2% had hyperparathyroidism [27]. Moini et al. [35] measured serum Vit. D, Ca, phosphorus, and alkaline phosphatase in the Vit. D treated group compared to placebo and found that serum Vit. D, phosphorus, and alkaline phosphatase were significantly higher in Vit. D treated group compared to the placebo group.

Dysmenorrhea-related symptoms

The effect of Vit. D and Ca supplements on the dysmenorrhea-related symptoms were mentioned in five of the reviewed studies [22, 25, 27, 28, 30]. Participants with low serum Vit. D were at greater risk of dysmenorrhea-related symptoms, including headache, fatigue, depression, mood swings, breast tenderness, nausea, and vomiting in two studies [22, 27]. Furthermore, Vit. D intake (high doses) decreased the severity of dysmenorrhea and dysmenorrhea-related symptoms (i.e., backache and crying tendency) [28]. In addition, Mehrpooya et al. [32] reported that omega-3 supplementation reduced vomiting and breast tenderness, while calcium intake alleviated bloating symptoms.

Abnormal low serum vitamin D can aggravate the symptoms associated with dysmenorrhea, while Vit. D and Ca intake could improve those symptoms. Low serum vitamin D could increase the severity of primary dysmenorrhea through increased PGD synthesis and decreased intestinal Ca absorption. At the same time, low serum Ca could increase the amplitude of uterine muscle contractility with subsequent uterine muscle ischemia and pain. Consequently, supplementation with Vit. D and Ca may effectively reduce the severity of primary dysmenorrhea and the need for pain-relief medications like NSAIDs.

DISCUSSION

A comprehensive search was conducted across Web of Science, PubMed, Scopus, and ScienceDirect to retrieve articles and studies published between 2010 and 2020. The search criteria included the following keywords: 1) 'primary dysmenorrhea' or 'painful menses', 2) 'vitamin D', 'vitamin D3', '25-OH vitamin D3', or 'cholecalciferol', 3) 'calcium', with the aim of evaluating the role of vitamin D and calcium in reducing the severity of primary dysmenorrhea. Five hundred sixty articles were initially retrieved. Eligible articles were evaluated by two independent authors (AD and IA). After reviewing the titles and abstracts of each article, 535 of them were not eligible for inclusion in this systematic review (because of the above-mentioned exclusion criteria). After a full review (i.e., including the results and discussions) of the remaining 25 articles, another eight were excluded (published before 2010, irrelevant or duplicate), and finally, 17 were eligible and were included in this systematic review.

A significant relationship between dysmenorrhea and serum Ca was reported by Zarei et al. [24]. Impaired Ca regulation is one of the factors contributing to the increased severity of dysmenorrhea [39]. Low serum Ca was also reported in women with premenstrual syndrome (PMS), which supports the role of Ca in neuromuscular regulation [39]. Low serum Ca could increase the amplitude of uterine muscle contraction with subsequent uterine muscle ischemia and pain [40]. The relationship between dysmenorrhea and serum Ca needs further studies.

An inverse relation between the severity of dysmenorrhea and serum Vit. D was reported in Karacin et al. [22] and Abdul-Razzak et al. [27] studies. Thys-Jacobs [39] also reported Vit. D deficiency in women with dysmenorrhea. Low serum Vit. D increases the severity of primary dysmenorrhea through increased PGD synthesis and decreased intestinal Ca absorption. In addition, it plays a crucial role in Ca absorption and metabolism (stages of hydroxylation) [41].

VDR expression in the uterus and ovaries [18] explains the role of Vit. D in inflammatory cytokine regulation [19]. Vit. D metabolites could reduce the level of inflammatory cytokines [20, 21, 42]. Vitamins, minerals absorption, and metabolism could be important in treating menstrual problems [42].

Abdul-Razzak et al. [27] and Anagnostis et al. [43] reported an association between severe dysmenorrhea and serum Vit. D and Ca in adolescents.

In addition, a nutritional balance could improve menstrual disorders and dysmenorrhea. Thys-Jacobs [39] reported a close relationship between Ca supplements and reduced severity of dysmenorrhea.

Calcium intake reduces the severity of menstrual cramps and backaches [44]. One study found that menstrual cramps and back pain were reduced after 1,200 mg of Ca per day for three months [40]. Low serum Ca increases uterine cramps and the severity of primary dysmenorrhea [22], which explains the role of Ca in regulating uterine muscle contractions [45].

This systematic review found that Vit. D intake in any dose could effectively reduce the severity of primary dysmenorrhea, and the intake of 50,000 IU of Vit. D weekly is recommended to treat Vit. D deficiency. Vit. D intake may also reduce the risk of PMS, possibly due to the regulation of Ca absorption and inflammatory cytokines [46, 47].

Vit. D changes were also reported with estradiol changes during different phases of the ovulatory and menstrual cycles [39]. A single oral dose (300,000 U) of cholecalciferol for five days before the menstrual flow reduces the severity of primary dysmenorrhea [35]. Vit. D decreases the severity of dysmenorrhea through decreased expression of cyclooxygenase 2 and inhibition of PGD production [48].

This systematic review found a significant positive relationship between the severity of dysmenorrhea and PTH, explained by the role of PTH in renal reabsorption and intestinal absorption of Ca.

The role of Ca in muscle contraction and relaxation was explained previously [47, 48], and the three hormones, calcitonin, PTH, and 25-hydroxy Vit. D (which regulates serum Ca) may play a physiological role in dysmenorrhea [49]. Low Vit. D is often associated with low serum Ca due to decreased intestinal Ca absorption. Low serum Ca increases PTH secretion with a subsequent increase in the renal reabsorption and intestinal absorption of Ca [48].

No significant relationship between serum phosphorus and primary dysmenorrhea was found in this systematic review, which needs to be confirmed in future studies. However, we found a significant relationship between the severity of dysmenorrhea-related symptoms and both serum Vit. D and Ca. Additionally, this review found that Vit. D and Ca supplements could reduce primary dysmenorrhea and the consumed analgesics.

Bertone-Johnson et al. [46] and Baird et al. [50] reported an inverse relationship between serum Vit. D and the risk of dysmenorrhea and mood changes. Rahnemaie et al. [25], found that serum levels of Vit. D was inversely related to the severity of dysmenorrhea-associated symptoms, including fatigue, headache, nausea, and vomiting.

Research on the impact of fish oil on primary dysmenorrhea is limited [51]. However, a study by Zamani et al. [52] indicated that fish oil intake can reduce the severity of primary dysmenorrhea. This effect is likely due to the ability of fish oil to inhibit the production of PGDs and leukotrienes, which are known to contribute to menstrual pain. Vitamin E and omega-3 intake have been observed to lessen the severity of dysmenorrhea. This reduction in pain severity may be attributed to the stimulating effect of vitamin E on beta-endorphins, which are natural pain-relieving compounds in the body [53].

Daily et al. [54] found that vitamin D, E, and ginger effectively decreased the severity of dysmenorrhea (the effect was more favorable in the ginger group than in the vitamin D and E groups). Rahnama et al. [11] suggested that ginger contents (i.e., gingerol and gingerdione) may have analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects [55]. Further, in-vitro studies support this by showing that ginger can inhibit the production of PGDs and leukotrienes, which are known to exacerbate menstrual pain [29]. The limited number of research investigating the effects of vitamin D and calcium on the severity of dysmenorrhea was the only limitation of this study, and further studies in this area are warranted.

CONCLUSION

This systematic review found an inverse relationship between the severity of dysmenorrhea and low serum levels of vitamin D and calcium. The findings suggest that supplementation with vitamin D and calcium could effectively reduce the severity of primary dysmenorrhea and the reliance on analgesics.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

Grant funding for scientific and/or technical projects for the years 2021-2022 – Republic of Kazakhstan - Features of bone tissue metabolism and mineral density in teenage girls with primary dysmenorrhea - IRN AP09563004 - Supervisor Ainur Amanzholkyzy.

Authorship

AD and AA were responsible for the study concept and design, literature review, data collection, and final revision before submission for publication. IA, AK, and SS were responsible for the literature review, Microsoft editing, and final revision before submission for publication. RN, AZ, GG, and DA were responsible for the literature review, Microsoft editing, updating the references, and final revision before submission for publication. IS is the corresponding author responsible for the literature review, Microsoft editing and drafting, and final revision before submission for publication.

References

- 1.EL-kosery S, Mostafa N, Yosseuf H. Effect of Body Mass Index on Primary Dysmenorrhea and Daily Activities in Adolescents. Med J Cairo Univ. 2020;88(1):79–84. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alsaleem MA. Dysmenorrhea, associated symptoms, and management among students at King Khalid University, Saudi Arabia: An exploratory study. J Family Med Prim Care. 2018;7(4):769–774. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_113_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gebeyehu MB, Mekuria AB, Tefera YG, Andarge DA, et al. Prevalence, Impact, and Management Practice of Dysmenorrhea among University of Gondar Students, Northwestern Ethiopia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Reprod Med. 2017;2017:3208276. doi: 10.1155/2017/3208276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ju H, Jones M, Mishra G. The prevalence and risk factors of dysmenorrhea. Epidemiol Rev. 2014;36:104–13. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxt009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burnett MA, Antao V, Black A, Feldman K, et al. Prevalence of primary dysmenorrhea in Canada. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2005;27(8):765–70. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(16)30728-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burnett M, Lemyre M. No 345-Primary Dysmenorrhea Consensus Guideline. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2017;39(7):585–595. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2016.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bernardi M, Lazzeri L, Perelli F, Reis FM, Petraglia F. Dysmenorrhea, and related disorders. F1000Res. 2017;6:1645. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.11682.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rahnemaei FA, Gholamrezaei A, Afrakhteh M, Zayeri F, et al. Vitamin D supplementation for primary dysmenorrhea: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2021;64(4):353–363. doi: 10.5468/ogs.20316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berek JS. 16th ed. Philadelphia (PA): Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2019. Berek & Novak’s gynecology. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rafique N, Al-Sheikh MH. Prevalence of primary dysmenorrhea and its relationship with body mass index. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2018;44(9):1773–1778. doi: 10.1111/jog.13697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abdi F, Amjadi MA, Zaheri F, Rahnemaei FA. Role of vitamin D and calcium in the relief of primary dysmenorrhea: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2021;64(1):13–26. doi: 10.5468/ogs.20205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agarwal AK, Agarwal A. A study of dysmenorrhea during menstruation in adolescent girls. Indian J Community Med. 2010;35(1):159–64. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.62586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guimarães I, Póvoa AM. Primary Dysmenorrhea: Assessment and Treatment. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2020;42(8):501–507. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1712131. English. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith RP, Kaunitz AM. Dysmenorrhea in adult women: Treatment. Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/dysmenorrhea-in-adult-women-treatment.

- 15.Zahradnik HP, Hanjalic-Beck A, Groth K. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and hormonal contraceptives for pain relief from dysmenorrhea: a review. Contraception. 2010;81(3):185–96. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosales-Alexander JL, Balsalobre Aznar J, Magro-Checa C. Calcium pyrophosphate crystal deposition disease: diagnosis and treatment. Open Access Rheumatol. 2014;6:39–47. doi: 10.2147/OARRR.S39039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown J, Crawford TJ, Datta S, Prentice A. Oral contraceptives for pain associated with endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;5(5):CD001019. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001019.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donayeva A, Amanzholkyzy A, Abdelazim IA, Saparbayev S, et al. The relation between vitamin D and the adolescents’ mid-luteal estradiol and progesterone. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2023;27(14):6792–6799. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202307_33150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Donayeva A, Amanzholkyzy A, Nurgaliyeva R, Gubasheva G, et al. Vitamin D and vitamin D receptor polymorphism in Asian adolescents with primary dysmenorrhea. BMC Womens Health. 2023;23(1):414. doi: 10.1186/s12905-023-02569-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thota C, Laknaur A, Farmer T, Ladson G, et al. Vitamin D regulates contractile profile in human uterine myometrial cells via NF-κB pathway. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210(4):347e1–347.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Donayeva A, Amanzholkyzy A, Nurgaliyeva R, Gubasheva G, et al. The relation between primary dysmenorrhea in adolescents and body mass index. Prz Menopauzalny. 2023;22(3):126–129. doi: 10.5114/pm.2023.13131422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karacin O, Mutlu I, Kose M, Celik F, et al. Serum vitamin D concentrations in young Turkish women with primary dysmenorrhea: A randomized controlled study. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;57(1):58–63. doi: 10.1016/j.tjog.2017.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kucukceran H, Ozdemir O, Kiral S, Berker DS, et al. The impact of circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin and oral cholecalciferol treatment on menstrual pain in dysmenorrheic patients. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2019;35(1):53–57. doi: 10.1080/09513590.2018.1490407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zarei S, Mohammad-Alizadeh-Charandabi S, Mirghafourvand M, Javadzadeh Y, Effati-Daryani F. Effects of Calcium-Vitamin D and Calcium-Alone on Pain Intensity and Menstrual Blood Loss in Women with Primary Dysmenorrhea: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Pain Med. 2017;18(1):3–13. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnw121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rahnemaie FS, Afrakhteh M, Nasiri M, Zayeri F, et al. Relationship between serum vitamin D with severity of primary dysmenorrhea and associated systemic symptoms in dormitories students of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences. Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertil. 2019;22:44–53. doi: 10.22038/ijogi.2019.13444. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zeynali M, Haghighian HK. Is there a relationship between serum vitamin D with dysmenorrhea pain in young women? J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2019;48(9):711–714. doi: 10.1016/j.jogoh.2019.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abdul-Razzak KK, Obeidat BA, Al-Farras MI, Dauod AS. Vitamin D and PTH status among adolescent and young females with severe dysmenorrhea. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2014;27(2):78–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bahrami A, Avan A, Sadeghnia HR, Esmaeili H, et al. High dose vitamin D supplementation can improve menstrual problems, dysmenorrhea, and premenstrual syndrome in adolescents. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2018;34(8):659–663. doi: 10.1080/09513590.2017.1423466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pakniat H, Chegini V, Ranjkesh F, Hosseini MA. Comparison of the effect of vitamin E, vitamin D and ginger on the severity of primary dysmenorrhea: a single-blind clinical trial. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2019;62(6):462–468. doi: 10.5468/ogs.2019.62.6.462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ayşegül Ö Seda A, Şevket O, Özdemir M, et al. A randomized controlled study of vitamin D in the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea. Duzce Med J. 2019;21:32–6. doi: 10.18678/dtfd.480596. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lama A, Najla A, Azah A, Areej A, Alaa E, Salem A. Vitamin D supplements as adjunctive therapy with analgesics for primary dysmenorrhea: a randomized clinical trial. Int J Reprod Med Gynecol. 2019;5(1):4–014. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mehrpooya M, Eshraghi A, Rabiee S, Larki-Harchegani A, Ataei S. Comparison the Effect of Fish-Oil and Calcium Supplementation on Treatment of Primary Dysmenorrhea. Rev Recent Clin Trials. 2017;12(3):148–153. doi: 10.2174/1574887112666170328125529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Charandabi SM, Mirghafourvand M, Chegini S, Javadzadeh Y. Calcium with and without magnesium for primary dysmenorrhea: a double-blind randomizedplacebo controlled trial. Int J Women Health Reprod Sci. 2017;5:332–8. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fareena Begum A. Coimbatore: Coimbatore Medical College; 2017. Study of prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in primary dysmenorrhea and administration of a single oral dose of vitamin D to improve primary dysmenorrhea. Available from: http://repository-tnmgrmu.ac.in/id/eprint/4922. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moini A, Ebrahimi T, Shirzad N, Hosseini R, et al. The effect of vitamin D on primary dysmenorrhea with vitamin D deficiency: a randomized double-blind controlled clinical trial. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2016;32(6):502–5. doi: 10.3109/09513590.2015.1136617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ataee M, Zangeneh M, Mahboubi M. Cholecalciferol for Primary Dysmenorrhea in a College aged Population-A Clinical Trial. J Biol Todays World. 2015;4:54–7. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zangene M, Veisi F, Nankali A, Rezaei M, Ataee M. Evaluation of the effects of oral vitamin-d for pelvic pain reduction in primary dysmenorrhea. Iran J Obstet Gynecol Inferti. 2014;16:14–20. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lasco A, Catalano A, Benvenga S. Improvement of primary dysmenorrhea caused by a single oral dose of vitamin D: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(4):366–7. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thys-Jacobs S. Micronutrients and the premenstrual syndrome: the case for calcium. J Am Coll Nutr. 2000;19(2):220–7. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2000.10718920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thys-Jacobs S, McMahon D, Bilezikian JP. Cyclical changes in calcium metabolism across the menstrual cycle in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(8):2952–9. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.DeLuca HF. Overview of general physiologic features and functions of vitamin D. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80(6 Suppl):1689S–96S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.6.1689S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Proctor ML, Murphy PA. Herbal and dietary therapies for primary and secondary dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;(3):CD002124. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Anagnostis P, Karras S, Goulis DG. Vitamin D in human reproduction: a narrative review. Int J Clin Pract. 2013;67(3):225–35. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Das B, Prasanna Chandra M, Samanta S, Mallick AK, Sowmya MK. Serum inorganic phosphorus, uric acid, calcium, magnesium, and sodium status during uterine changes of menstrual cycle. Int J Biomed Res. 2012;3:209–13. doi: 10.7439/ijbr.v3i4.412. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marshall WJ, Bangert SK. Edinburgh: Mosby; 2008. Clinical chemistry. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bertone-Johnson ER. Vitamin D and the occurrence of depression: causal association or circumstantial evidence? Nutr Rev. 2009;67(8):481–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2009.00220.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Holick MF. Vitamin D: a D-Lightful health perspective. Nutr Rev. 2008;66(10) Suppl 2:S182–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2008.00104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hashemipour S, Larijani B, Adibi H, Javadi E, et al. Vitamin D deficiency and causative factors in the population of Tehran. BMC Public Health. 2004;4:38. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-4-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maïmoun L, Sultan C. Effect of physical activity on calcium homeostasis and calciotropic hormones: a review. Calcif Tissue Int. 2009;85(4):277–86. doi: 10.1007/s00223-009-9277-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baird DD, Hill MC, Schectman JM, Hollis BW. Vitamin D and the risk of uterine fibroids. Epidemiology. 2013;24(3):447–53. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31828acca0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Latthe PM, Champaneria R, Khan KS. Dysmenorrhoea. BMJ Clin Evid. 2011;2011:813. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zamani M, Arab M, Nasrollahi S, Manikashani K. The evaluation of fish oil (Omega-3 fatty acids) efficacy in treatment of primary dysmenorrhea in high school female students in Hamadan. J Gorgan Univ Med Sci. 2005;7:39–42. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sadeghi N, Paknezhad F, Rashidi Nooshabadi M, Kavianpour M, et al. Vitamin E and fish oil, separately or in combination, on treatment of primary dysmenorrhea: a double-blind, randomized clinical trial. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2018;34(9):804–808. doi: 10.1080/09513590.2018.1450377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Daily JW, Zhang X, Kim DS, Park S. Efficacy of Ginger for Alleviating the Symptoms of Primary Dysmenorrhea: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. Pain Med. 2015;16(12):2243–55. doi: 10.1111/pme.12853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rahnama P, Montazeri A, Huseini HF, Kianbakht S, Naseri M. Effect of Zingiber officinale Rrhizomes (ginger) on pain relief in primary dysmenorrhea: a placebo randomized trial. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2012;12:92. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-12-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]