Abstract

Background

Gram-negative bacilli represents an important pathogen in hospital-acquired infections (HAIs) worldwide. The emergence of antibiotic resistance in these pathogens warrants attention for the proper management of infections. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) resistance represents a major therapeutic problem in infections due to Gram-negative bacilli.

The present study aimed to study the extended-spectrum beta-lactamase genes blaTEM, blaSHV, and blaCTX-M by multiplex polymerase reaction in isolated Gram-negative bacilli from HAIs in pediatric patients.

Methods

The study included one hundred-five isolates of Gram-negative bacilli from pediatric patients with different types of HAIs. The isolates were subjected to full microbiological identification, antibiotics susceptibility by disc diffusion method, the phenotypic study of ESBL, and the genetic study of ESBL genes by multiplex PCR.

Results

Fifty isolates of Gram-Negative bacilli showed ESBL activity by a phenotypic study by double disc diffusion method (50/105). All ESBL producers’ isolates were positive by PCR for ESBL genes. The most frequent gene was blaTEM (64%), followed by blaSHV (30%) and CTX-M (22%). Mixed genes were found in 4 isolates (8%) for blaTEM and blaSHV, blaTEM and CTX-M. There was a significant association between PCR for ESBL genes and phenotypic ESBL detection (P = 0.001). There was significant detection of ESBL genes in E. coli (28%), followed by Enterobacter spp. (26%), Klebsiella spp. (24%), Serratia (14%), Pseudomonas spp. (6%) and Proteus (2%), P = 0.01. There Seventy percent of isolates positive for ESBL production had an insignificant association between MDR and PCR for ESBL genes (P = 0.23).

Conclusion

The present study highlights the prevalence of ESBL activity among clinical isolates of Gram-negative bacilli isolated from hospital-acquired infections in pediatric patients. The most common gene responsible for this activity was blaTEM gee followed by blaSHV and blaCTX-M. There was a high prevalence of multiple antibiotic resistance among isolates with ESBL activity. The finding of the present study denotes the importance of screening extended beta-lactamase among Gram-negative bacilli associated with HAIs in pediatric patients.

Keywords: ESBL, Phenotypic, Multiplex PCR, BlaCTX-M, BlaSHV, BlaTEM

Introduction

Hospital-acquired infection is a global health problem with around two and a half million new infections every year in European countries with a fourth of them being due to multidrug-resistant microorganisms (MDR) [1, 2]. Gram-negative bacilli is an important etiology of such infections with species of Enterobacteriaceae family such as E.coli and Klebsiella species representing principle etiology in many geographical regions such as United States of America, Canada, Middle East, Europe, Asia, and Australia [3] Pediatric patients are susceptible to HAIs due to their immature immune systems, presence of multiple comorbidities, and cross-infection from recurrent close contact with health care team members [4].

Gram-negative bacilli had shown resistance to antibiotics with broad-spectrum activity due to extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) those results from the acquiring the gene coding enzymes that increase the efflux pumps leading to the changes in the antibiotic binding sites [5]. The antibiotic of choice to treat these infections is carbapenems [6].

There are many types of ESBL genes with TEM and SHV as the most prevalent resistance genes however, there is a reported increase in the CTX-M gene [7–9]. The CTX-M β-lactamase gene was reported in 1980 with more than 100 variants reported [10].

The prevalence of the ESBL genotypes varied by geographical region and the time of infection. The predominant types of ESBL genes were SHV and TEM in the United States of America and Europe during the period from 1980 up to 1990 [11, 12], while in Asia the most prevalent ESBL genotype was CTX-M [13, 14]. The last two decades have shown an increase in the CTX-M genotype variants CTX-M15 and CTX-M14 [15]. The epidemiology of ESBL genotyping in adult patients is well studied in various reports [16–19] and Egypt [20]. However, fewer studies reported ESBLs in pediatric patients.

Therefore, the present study aimed to study the ESBL genes TEM, SHV, and CTX-M by multiplex polymerase reaction in isolated Gram-negative bacilli from HAIs in pediatric patients.

Material and method

The study was a retrograde cross-sectional study that included one hundred- and five-gram negative isolates from pediatric patients with hospital-acquired infections from January 2019 till January 2020. The children were diagnosed with HAIs as described by criteria of the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) guidelines [21]. Children with community-acquired infections and children with HAIs associated with Gram-positive isolates were the exclusion criteria for this study. The ethical approval of the study was obtained from the ethical committee of Mansoura Faculty of Medicine (R.23.09.2330) and written approval was obtained from the parent of each child.

Bacterial identification

After primary isolation of organisms from the clinical samples, further identification was performed according to standard microbiological methods. Each isolate was cultured onto Trypticase soy agar with 10% sheep blood with incubated at 35 °C in an atmosphere with 5% CO2 for 72 hours. Then identification was performed by Gram stain and an oxidase test, followed by Vitek 2 (bioMérieux-USA) automated identification systems to achieve a species-level identification [22].

Antibiotics sensitivity test by disc diffusion method

The used antibiotics discs were imipenem (10 μg), cefepime (30 μg), amikacin (30 μg), amoxicillin/clavulinic acid (20/10 μg), ampicillin (10 μg), aztreonam (30 μg), cefotaxime (30 μg), cefoxitin (30 μg), ceftazidime (30 μg), ceftriaxone (30 μg) gentamicin (10 μg), piperacillin (100 μg), piperacillin/tazobactam (100/10 μg), cefoperazone (75 μg), ciprofloxacin (5 μg), gatifloxin (5 μg), amoxicillin (5 μg) (Oxoid, United Kingdom). Gram-negative bacilli isolates were suspended in Muller-Hinton broth for preparation of 0.5 McFarland concentrations then spread over Muller-Hinton agar. The discs were applied over the agar then the plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 hours. The measured inhibition zone diameter around the discs was interpreted as sensitive or resistant according to the guidelines of the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) [23]. Multidrug resistance (MDR) was identified as resistance to three or more of antibiotic classes.

Detection of ESBL

Gram-negative bacilli isolate resistant to ceftazidime or/or cefotaxime were further tested for the ESBL phenotype by double discs method [23]. The isolates were diluted in Muller-Hinton broth to prepare o.5 McFarland and plated over a Muller-Hinton agar plate and cefotaxime and ceftazidime discs and ceftazidime compound with clavulanic acid discs were added with incubation at 37 °C for 24 hours. The interpretation of ESBL was reported if there was an increase of the zone of inhibition around combined antibiotics discs with clavulanic acid by ≥5 mm. The used organism as negative control for ESBL was Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 700603 and the used organism as positive control was E. coli ATCC 25922.

Multiplex PCR for detection of TEM, SHV, and CTX-M genes

DNA extraction method

DNA was extracted from isolated pure colonies by heat method [24]. Colonies were obtained from culture over a MacConkey plate and suspended in 40 μm of sterile distilled water. The suspension was incubated at 95 °C for 5 minutes and then centrifuged at 12000 rpm for 10 minutes. Then the supernatant was obtained and stored at − 20 °C till the time of amplification.

Multiplex PCR

Five microns of the extracted DNA was emulsified in the 50 μl reaction mix, containing 10 pmol of the used primers, Table 1, 10 mM dNTPs mix, and 2.5 U of Taq polymerase (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) in 1x Taq polymerase buffer. The used negative control was E. coli ATCC 25922. The sequences of the amplifications were heating at 94 °C for 5 minutes for denaturation, then 35 cycles including heating at 94 °C for 30 seconds, followed by heating at 60 °C for 30 seconds heating at 72 °C for 50 seconds, and finally extension for one cycle at 72 °C for 5 minutes. The PCR product was electrophoresed using 1.5% agarose gel with ethidium bromide to visualize the amplified fragment [25].

Table 1.

Genes and the sequences of the primers and base pair(bp)

| Gene | Sequences of the primers | Bp |

|---|---|---|

| TEM |

TTTCGTGTCGCCCTTATTCC404 ATCGTTGTCAGAAGTAAGTTGG |

404 |

| SHV |

CGCCTGTGTATTATCTCCCT CGAGTAGTCCACCAGATCCT |

294 |

| CTX-M |

CGCTGTTGTTAGGAAGTGTG GGCTGGGTGAAGTAAGTGAC |

754 |

Statistical analysis

The data was analyzed using the SPPS 22.0 package. Quantitative data was interpreted as mean and standard deviation (SD). Qualitative data was interpreted as number and percentage and the comparison was performed by Chi-square test. P was considered significant if < 0.05.

Result

The study included 105 pediatric patients with an age range of 0.2 up to 15.5 years. They were 48.6% males and 51.4% females. The most frequent infections were urinary tract infections 50.5%, followed by respiratory tract infections (22.9%) wound infections (15.2% and sepsis (11.4%), Table 2.

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical data of the studied pediatric patients

| Age (years) | ||

| Minimum | 0.2 years | |

| Maximum | 15.5 | |

| Median | 6.00 | |

| Sex | ||

| Male (No.-%) | 51 | 48.6% |

| Female (No.-%) | 54 | 51.4% |

| Urinary tract infections (No.-%) | 53 | 50.5% |

| Respiratory tract infections (No.-%) | 24 | 22.9% |

| Wound Infections (No.-%) | 16 | 15.2% |

| Sepsis (No.-%) | 12 | 11.4% |

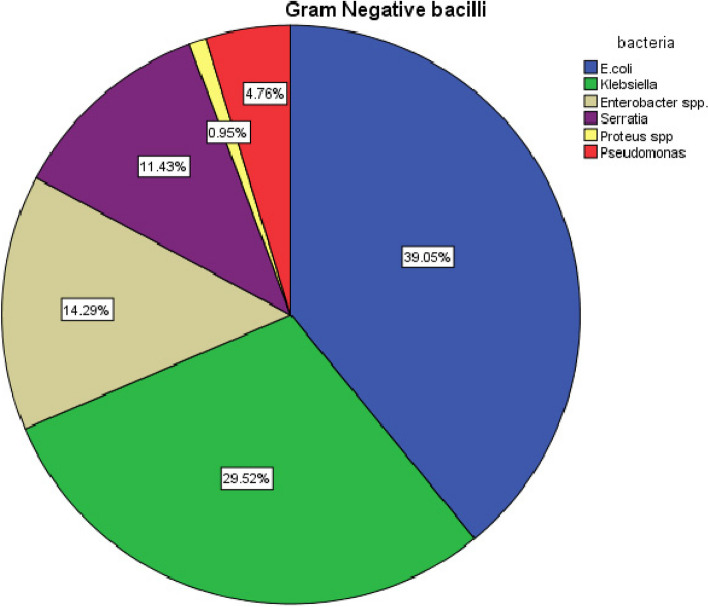

The most prevalent Gram-negative bacilli isolated was E. coli (39%), followed by Klebsiella spp. (29.5%0, Enterobacter spp. (14.3%), and Serratia (11.4%). Pseudomonas spp was isolated from 4.8% of the samples, Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Frequency of the isolated Gram-Negative bacilli

The most antibiotic resistance of the isolated Gram-negative bacilli was for beta-lactam antibiotics, amoxicillin (94.3%), ampicillin (81.9%), ampicillin (81.9%), cefoperazone (81.0%), Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (73.3%), piperacillin (67.6%). The least antibiotic resistance was for amikacin (12.4%), gatifloxacin (33.3%), and garamicin (36.2%). Resistance to imipenem was 44.8%, Table 3.

Table 3.

Antibiotic resistance of isolated Gram-Negative bacilli

| Antibiotics | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| Amoxicillin | 99 | 94.3 |

| Ampicillin | 86 | 81.9 |

| Aztreonam | 58 | 55.2 |

| Cefotaxime | 68 | 64.8 |

| Ceftriaxone | 62 | 59.0 |

| Ceftazidime | 69 | 65.7 |

| Cefoperazone | 85 | 81.0 |

| Imipenem | 47 | 44.8 |

| Piperacillin | 71 | 67.6 |

| Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid | 77 | 73.3 |

| Amikacin | 13 | 12.4 |

| Garamicin | 38 | 36.2 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 46 | 43.8 |

| Gatfloxacin | 35 | 33.3 |

| Cefoxitin | 61 | 58.1 |

| MDR | 67 | 63.8 |

Fifty isolates of Gram-Negative bacilli showed ESBL activity by a phenotypic study by double-disc diffusion method (50/105). All ESBL producers’ isolates were positive by PCR for ESBL genes. The most frequent gene was blaTEM (64%), followed by blaSHV (30%) and CTX-M (22%). Mixed genes were found in 4 isolates (8%) for each of blaTEM and blaSHV, and CTX-M and blaTEM. There was a significant association between PCR for ESBL genes and phenotypic ESBL detection (P = 0.001), Table 4.

Table 4.

Association between phenotypic ESBL detection and multiplex PCR for ESBL genes

| Multiplex-PCR | ESBL | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive (no = 50) | Negative (n = 55) | |||

| N0. | % | N0. | % | |

| Multiplex-PCR | 50 | 100 | 55 | 100% |

| blaTEM | 32 | 64 | 0 | 0% |

| blaSHV | 15 | 30 | 0 | 0% |

| CTX-M | 11 | 22% | 0 | 0% |

| Mixed TEM and SHV | 4 | 8% | ||

| Mixed CTXM and TEM | 4 | 8% | ||

| Mixed SHV and CTX-M | 0 | 0% | ||

Chi-square, P = 0.001.

There was significant detection of ESBL genes in E. coli (28%), followed by Enterobacter spp. (26%), Klebsiella spp. (24%), Serratia spp. (14%), Pseudomonas spp. (6%) and Proteus spp. (2%), P = 0.01, Table 5.

Table 5.

ESBL genes in isolated bacteria

| Organisms | PCR positive for ESBL genes (n = 50) | |

|---|---|---|

| No. | % | |

| E. coli | 14 | 28 |

| Klebsiella spp. | 12 | 24 |

| Enterobacter spp. | 13 | 26 |

| Serratia | 7 | 14 |

| Pseudomonas spp. | 3 | 6 |

| Proteus spp. | 1 | 2 |

Chi-square test, P = 0.01.

There Seventy percent of isolates positive for ESBL production had an insignificant association between MDR and PCR for ESBL genes (P = 0.23), Table 6.

Table 6.

Association between MDR and ESBL genes

| MDR | PCR for ESBL genes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive (n = 50) | Negative (n = 55) | |||

| No. | % | No. | % | |

| MDR | ||||

| Positive | 35 | 70% | 32 | 58.2% |

| Negative | 15 | 30% | 23 | 41.8% |

Chi-square test, P = 0.23.

There was a statistically significant association between the presence of ESBL and stay in hospital for more than 7 days and mortality of the patients (P = 0.001), Table 7.

Table 7.

Association between ESBL and outcome of the patients

| outcome | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Death | less than 7 days | more than 7 | |||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | ||

| ESBL | positive | 8 | 100 | 2 | 3.5 | 40 | 100 |

| negative | 0 | 0 | 55 | 96.5 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 8 | 100 | 57 | 100 | 40 | 100 | |

Chi-square test, P = 0.001.

Discussion

Pediatric patients are vulnerable to hospital-acquired infections attributed to their immature system, the presence of underlying comorbidities, and close contact with healthcare personnel [4].

During the period of the present study, the most frequent infections were urinary tract infections 50.5%, followed by respiratory tract infections (22.9%) wound infections (15.2%), and sepsis (11.4%). This finding was contrary to previous findings reporting that the most prevalent HAIs in pediatric patients were central line–associated bloodstream infection that ranges from 25% up to 30%, ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) with ranges from 20% up to 25%, urinary tract infection associated with catheter 15% [26], and surgical site infection (SSI) 11% [27]. Another study revealed The most common HAI was surgical site infection (40.0%), followed by bloodstream infection (21.5%), and lower respiratory tract infection (14.6%) [28]. The type of HAI differs according to the age of the patients, geographical regions, the practice of preventive measures, and the time of surveillance. The preventive measures for HAIs include the need for adequate isolation measures, proper sterilization of the devices, regular microbiologic audits, appropriate hand hygiene practices, and efficient education and training [29].

In the present study, the most prevalent Gram-negative bacilli isolated was E. coli (39%), followed by Klebsiella spp. (29.5%), Enterobacter spp. (14.3%), and Serratia (11.4%). Pseudomonas spp. Among the previous 19 studies from Egypt reporting the prevalence of Gram-negative bacilli infections among pediatric patients, Klebsiella species/K. pneumoniae and Escherichia coli were typically the most frequently isolated organisms Also, in Saudi Arabia, Klebsiella spp./K. pneumoniae and E. coli were the most frequently associated with infections [30].

The most antibiotic resistance of the isolated Gram-negative bacilli was for beta-lactam antibiotics, amoxicillin, ampicillin, ampicillin, cefoperazone, Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, and piperacillin. The last antibiotic resistances were for amikacin (12.4%), gatifloxacin (33.3%), and garamicin (36.2%). Resistance to imipenem was 44.8% Previous report supported our finding as the resistance was high for multiple classes of beta-lactams (Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators) and lower resistance of E. coli and Klebsiella spp. to amikacin and carbapenem antibiotics [31].

This finding denotes the importance of identifying methods that may reduce antimicrobial resistance in HAIs through the implementation of an antibiotics stewardship program and adequate antibiotics surveillance [32].

The ESBLs are identified as the ability of the organisms to hydrolyze various types of β-lactam antibiotics, including the third generation of cephalosporins such as cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, ceftazidime, and monobactams such as aztreonam. Gram-negative bacteria with ESBL capacity have significant therapeutic difficulties.

In the present study, around half of the isolates (50/105) had ESBL activity. In a previous study from Gaza, (51.6%) of Gram-negative bacilli were ESBL producers [33]. Significant prevalence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase production from isolated Gram-negative bacilli was also reported in different Asian countries with varying ranges according to countries, reported to be 66.7% in India [34], 54.7–61% in Turkey [35, 36], 41% in United Arab Emirates [37], and 72.1% in Iran [38].

In the genetic study of ESBL genes, the most prevalent gene was blaTEM (64%), followed by blaSHV (30%) and blaCTX-M (22%). Mixed genes were found in 4 isolates (8%) for blaTEM and blaSHV, blaTEM and blaCTX-M. In the Previous report detection of these genes by PCR was 85 (59%) had at least one gene with the prevalence rates of blaCTX-M was 60%, blaTEM was 57.6%, and blaSHV was 38.3% [33].

Like our results, the previous report found that the blaTEM gene was the most prevalent (49%) followed by blaSHV (44%) and blaCTX-M (28%), [39]. On the other hand, previous studies revealed that the most prevalent genotypes of ESBL were blaTEM (86%), blaCTX-M (78%), and blaSHV (28%) [40]. The importance of genetic studies of ESBL genes is attributed to the capacity of these genes to spread horizontally to other bacterial species leading to widespread of ESBL activity in the hospital among different pathogens [40].

Seventy percent of isolates positive for ESBL genes detection by PCR were MDR, though this association was statistically insignificant, it is an alarming sign. The trend of multidrug-resistant profile associated with the currently analyzed genes blaTEM, blaHSV, and blaCTX-M to set up a routine screening of ESBL in clinical laboratories to prevent the spread of resistant isolates in health care settings. Previous data supported the association of ESBL and MDR among Gram-negative bacilli as a previous study reported that 53.3% of MDR E. coli were found resistant to > 7 antimicrobial agents and ESBL was detected in 32.7% of them [40, 41].

Clinical Isolates with ESBL activity are responsible for outbreaks in healthcare settings and lead to treatment failure with an increase in hospital cost and increased mortality rate due to treatment failure [42, 43]. In the present study, there was a statistically significant association with increased hospital stay and mortality rate with ESBL activity. The treatment of ESBL-producing isolates depends mainly on the use of Carbapenems. However, the resistance to carbapenem is increasing [44]. Therefore, the introduction of antimicrobial stewardship programs in healthcare is essential to overcome the growing rates of antimicrobial resistance [45].

Conclusion

The present study highlights the prevalence of ESBL activity among clinical isolates of Gram-negative.

Bacilli isolated from hospital-acquired infections in pediatric patients. The most common gene responsible for this activity was blaTEM gee followed by blaSHV and blaCTX-M. There was a high prevalence of multiple antibiotic resistance among isolates with ESBL activity. The finding of the present study denotes the importance of screening extended beta-lactamase among Gram-negative bacilli associated with HAIs in pediatric patients.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ESBL

Extended spectrum beta lactamase

- HAIs

Hospital-acquired infections

- MDR

Multidrug-resistant microorganisms

Authors’ contributions

AGAE shared in the laboratory study, the draft preparation of the article data analysis of the study and revision of the draft of the article. D E F B shared in the laboratory study, the draft preparation of the article data analysis of the study and revision of the draft of the article. NYAE K shared in the laboratory study draft preparation of the article. MESZ shared the laboratory study, the draft preparation of the article, and the data analysis of the study. EMF shared in the laboratory study and draft preparation of the article. AEMM shared in the laboratory study and draft preparation of the article. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB). Self-funded.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available in the Fighshare repository at 10.6084/m9.figshare.24153192.v1

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All methods were performed by the ethical standards as laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The ethical approval of the study was obtained from the ethical committee of Mansoura Faculty of Medicine (R.23.09.2330) and written approval was obtained from the parent of each child.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

There is no conflict of interest for any of the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Tassew S, Alebachew Woldu M, Amogne Degu W, Shibeshi W. Management of hospital-acquired infections among patients hospitalized at Zewditu memorial hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: a prospective cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0231949. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedrich A. Control of hospital-acquired infections and antimicrobial resistance in Europe: the way to go. Wien Med Wochenschr. 2019;169:25–30. doi: 10.1007/s10354-018-0676-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richet H. Seasonality in gram-negative and healthcare-associated infections. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:934–940. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gadallah MA, Aboul Fotouh AM, Habil IS, Imam SS, Wassef G. Surveillance of healthcare-associated infections in a tertiary hospital neonatal intensive care unit in Egypt: 1-year follow-up. Am J Infect Control. 2014;42:1207–1211. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2014.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walsh F. The multiple roles of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance in nature. Front Microbiol. 2013;4:255. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Habte-Gabr E. Antimicrobial resistance: a global public health threat. J Eritrean Med Assoc. 2010;3:36–40. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chong Y, Ito Y, Kamimura T. Genetic evolution and clinical impact in extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Infect Genet Evol. 2011;11:1499–1504. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bevan ER, Jones AM, Hawkey PM. Global epidemiology of CTX-M β-lactamases: temporal and geographical shifts in genotype. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017;72:2145–2155. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daoud Z, Salem-Sokhn E, Dahdouh E, et al. Resistance and clonality in Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp. and relationship with antibiotic consumption in major Lebanese hospitals. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2017;11:45–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2017.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonnet R. Growing group of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases: the CTX-M enzymes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:1–14. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.1.1-14.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karanika S, Karantanos T, Arvantis M, Grigoras C, E. Mylonakis fecal colonization with extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae and risk factors among healthy individuals: a systematic review and metanalysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:310–318. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Canton R, Novais A, Valverde A, Machado E, Peixe L, Baquero F, et al. Prevalence and spread of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Europe. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008;14:144–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bush K. Extended-spectrum β-lactamases in North America, 1987-2006. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008;14:134–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chanawong A, M'Zali FH, Heritage J, Xiong JH, Hawkey PM. Three cefotaxime, CTX-M-9, CTX-M-13, and CTX-M14, among Enterobacteriaceae in the People’s Republic of China. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:630–637. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.3.630-637.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chia JH, Chu C, Su LH, Chiu CH, Kuo AJ, Sun CF, et al. Development of a multiplex PCR and SHV melting-curve mutation detection system for the detection of some SHV and CTX-M β-lactamases of Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Enterobacter cloacae in Taiwan. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:4486–4491. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.9.4486-4491.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pitout JDD, Laupland KB. Extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae: an emerging public-health concern. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:159–166. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70041-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shibata N, Kurokawa H, Doi Y, Yagi T, Yamane K, Wachino J, et al. PCR classification of CTX-M-type β-lactamase gene identified in clinically isolated gram-negative bacilli in Japan. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:791–795. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.2.791-795.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chong Y, Shimoda S, Yakushiji H, Ito Y, Miyamoto T, Kamimura T, et al. Community spread of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Proteus mirabilis: a long-term study in Japan. J Med Microbiol. 2013;62:1038–1043. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.059279-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higa S, Sarassari R, Hamamoto K, Yakabi Y, Higa K, Koja Y, et al. Characterization of CTX-M type ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae isolated from asymptomatic healthy individuals who live in a community of the Okinawa prefecture, Japan. J Infect Chemother. 2019;25:314–317. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2018.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Helmy AK, Sidkey NM, El-Badawy RE, et al. The emergence of microbial infections in some hospitals of Cairo, Egypt: studying their corresponding antimicrobial resistance profiles. BMC Infect Dis. 2023;23:424. doi: 10.1186/s12879-023-08397-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boev C, Kiss E. Hospital-acquired infections: current trends and prevention. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2017;29(1):51–65. doi: 10.1016/j.cnc.2016.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ledeboer NA, Lopansri BK, Dhiman N, Cavagnolo R, Carroll KC, Granato P, Thomson R, Jr, Butler-Wu SM, Berger H, Samuel L, Pancholi P, Swyers L, Hansen GT, Tran NK, Polage CR, Thomson KS, Hanson ND, Winegar R, Buchan BW. Identification of gram-negative Bacteria and genetic resistance determinants from positive blood culture broths by use of the Verigene gram-negative blood culture multiplex microarray-based molecular assay. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53(8):2460–2472. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00581-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.CLSI, editor. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. 28th ed. CLSI supplement M100. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hijazi SM, Fawzi MA, Ali FM, Abd El Galil KH. Prevalence and characterization of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases producing Enterobacteriaceae in healthy children and associated risk factors. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2016;29(15):3. doi: 10.1186/s12941-016-0121-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hassan MI, Alkharsah KR, Alzahrani AJ, Obeid OE, Khamis AH, Diab A. Detection of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases-producing isolates and effect of AmpC overlapping. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2013;7(8):618–629. doi: 10.3855/jidc.2919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lodha R, Natchu UC, Nanda M, Kabra SK. Nosocomial infections in pediatric intensive care units. Indian J Pediatr. 2001;68:1063–1070. doi: 10.1007/BF02722358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zabaglo M, Sharman T. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Postoperative Wound Infection. 2022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saleem Z, Hassali MA, Godman B, Hashmi FK, Saleem F. A multicenter point prevalence survey of healthcare-associated infections in Pakistan: findings and implications. Am J Infect Control. 2019;47(4):421–424. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2018.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kannan A, Pratyusha K, Thakur R, et al. Infections in critically ill children. Indian J Pediatr. 2023;90:289–297. doi: 10.1007/s12098-022-04420-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Al Dabbagh M, Alghounaim M, Almaghrabi RH, Dbaibo G, Ghatasheh G, Ibrahim HM, Aziz MA, Hassanien A, Mohamed N. A narrative review of healthcare-associated gram-negative infections among pediatric patients in middle eastern countries. Infect Dis Ther. 2023;12(5):1217–1235. doi: 10.1007/s40121-023-00799-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van An N, Hoang LH, Le HHL, Thai Son N, Hong LT, Viet TT, Le TD, Thang TB, Vu LH, Nguyen VTH, Xuan NK. Distribution, and antibiotic resistance characteristics of Bacteria isolated from blood culture in a teaching Hospital in Vietnam during 2014-2021. Infect Drug Resist. 2023;23(16):1677–1692. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S402278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2022;399(10325):629–655. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02724-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.El Aila NA, Al Laham NA, Ayesh BM. Prevalence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase and molecular detection of blaTEM, blaSHV, and blaCTX-M genotypes among gram-negative bacilli isolates from the pediatric patient population in Gaza strip. BMC Infect Dis. 2023;23(1):99. doi: 10.1186/s12879-023-08017-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hawkey PM. Prevalence and clonality of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in Asia. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008;14(Suppl 1):159–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gur D, Hascelik G, Aydin N, Telli M, Gültekin M, Ogülnç D, Arikan OA, Uysal S, Yaman A, Kibar F, et al. Antimicrobial resistance in gram-negative hospital isolates: results of the Turkish HITIT-2 surveillance study of 2007. J Chemother. 2009;21(4):383–389. doi: 10.1179/joc.2009.21.4.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perez F, Endimiani A, Hujer KM, Bonomo RA. The continuing challenge of ESBLs. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2007;7(5):459–469. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Al-Zarouni M, Senok A, Rashid F, Al-Jesmi SM, Panigrahi D. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in the United Arab Emirates. Med Princ Pract. 2008;17(1):32–36. doi: 10.1159/000109587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Feizabadi MM, Delfani S, Raji N, Majnooni A, Aligholi M, Shahcheraghi F, Parvin M, Yadegarinia D. Distribution of Bla(TEM), Bla(SHV), Bla(CTX-M) genes among clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae at Labbafinejad hospital, Tehran, Iran. Microb Drug Resist. 2010;16(1):49–53. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2009.0096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rezai MS, Salehifar E, Rafiei A, Langaee T, Rafati M, Shafahi K, Eslami G. Characterization of multidrug-resistant extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli among uropathogens of pediatrics in north of Iran. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:309478. doi: 10.1155/2015/309478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dirar MH, Bilal NE, Ibrahim ME, Hamid ME. Prevalence of extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) and molecular detection of blaTEM, blaSHV, and blaCTX-M genotypes among Enterobacteriaceae isolates from patients in Khartoum, Sudan. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;37:213. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2020.37.213.24988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ibrahim ME, Bilal NE, Hamid ME. Increased multi-drug resistant Escherichia coli from hospitals in Khartoum state. Sudan Afr Health Sci. 2012;12(3):368–375. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v12i3.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Trecarichi EM, Cauda R, Tumbarello M. Detecting risk and predicting patient mortality in patients with extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae bloodstream infections. Future Microbiol. 2012;7(10):1173–1189. doi: 10.2217/fmb.12.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wong-Beringer A. Therapeutic challenges associated with extended-spectrum, beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Pharmacotherapy. 2001;21(5):583–592. doi: 10.1592/phco.21.6.583.34537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kelly AM, Mathema B, Larson EL. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in the community: a scoping review. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2017;50(2):127–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2017.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Majumder MAA, Rahman S, Cohall D, Bharatha A, Singh K, Haque M, Gittens-St HM. Antimicrobial stewardship: fighting antimicrobial resistance and protecting global public health. Infect Drug Resist. 2020;13:4713–4738. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S290835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available in the Fighshare repository at 10.6084/m9.figshare.24153192.v1