Summary

Background

People released from correctional facilities face multifactorial barriers to continuing HIV treatment. We hypothesised that barriers faced in the first 6 months of community re-entry would be decreased by a multilevel group-based and peer-led intervention, the Transitional Community Adherence Club (TCAC).

Methods

We did a pragmatic, open-label, individually randomised controlled trial in five correctional facilities in Gauteng, South Africa. Participants aged 18 years and older and receiving antiretroviral therapy (ART) in correctional facilities were enrolled before release and randomly assigned (1:2) to either passive referral (usual care) or TCACs. TCACs followed a 12-session curriculum over 6 months and were facilitated by trained peer and social workers. Participants were followed up by telephone and in person to assess the primary outcome: post-release enrolment in HIV treatment services at 6 months from the date of release. We did an intention-to-treat analysis to determine the effectiveness of TCACs compared with usual care. The trial was registered with the South African National Clinical Trials Register (DOH-27–0419–605) and ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03340428). This study is completed and is listed as such on ClinicalTrials.gov.

Findings

From March 1, to Dec 13, 2019, we screened 222 individuals and enrolled 176 participants who were randomly assigned 1:2 to the usual care group (n=59) or TCACs (n=117). 175 participants were included in the final analysis. In the usual care group, 21 (36%) of 59 participants had enrolled in HIV treatment services at 6 months, compared with 71 (61%) of 116 in the TCAC group (risk ratio 1·7, 95% CI 1·2–2·5; p=0·0010). No adverse events were reported.

Interpretation

We found strong evidence that a differentiated service delivery model with curriculum and peer support designed specifically to address the needs of people with HIV returning from incarceration improved the primary outcome of enrolment in HIV treatment services. Our approach is a reasonable model to build further HIV treatment continuity interventions for individuals in the criminal justice system in South Africa and elsewhere.

Introduction

South Africa has the largest number of people with HIV in the world and has the 12th highest population in the criminal justice system.1–4 In 2020, 7·5 million people aged 15 years and older were estimated to have HIV, 79 000 died from AIDS-related illness, and 220 000 were newly infected with HIV.2 At any given time, South Africa has 140 000–200 000 people who are incarcerated.5 About 37 000 (23%) of this population have HIV, and approximately half of those with HIV are released yearly and return to the community.6,7 While incarcerated, most people with HIV who are aware of their HIV status initiate antiretroviral therapy (ART), and most (>90%) achieve viral load suppression.5,8 Unfortunately, these impressive HIV treatment outcomes drop substantially during community re-entry. In South Africa, only 34% of people with HIV have documented HIV clinic visits within 90 days of release.9

Worldwide, people returning from incarceration face complex challenges to continuing HIV treatment.10–13 Among these challenges are the individual and blended effects of diminished social support, lost self-efficacy, multiple intersecting forms of stigma and discrimination arising from incarceration history and HIV status, economic marginalisation, substance use disorders, and logistically burdensome health-care systems. Currently, the standard approach for linking released individuals to HIV treatment services in South Africa does not address known barriers to HIV treatment continuity during community re-entry.14,15 Usual care involves issuing a referral letter, prepared by the correctional health staff, for the released individual to present at a community-based primary health clinic. There is no additional post-release linkage support. Therefore, we sought to improve the continuity of HIV treatment during community re-entry through a multilevel intervention we called the Transitional Community Adherence Club (TCAC).

We developed the TCACs using the principles of community adherence clubs: a differentiated model of HIV care used widely in South Africa in which people with HIV meet every other month as a group to collect their HIV medications outside of the clinic environment.4,16 We adapted the community adherence club model for the TCACs by increasing the frequency of meetings and developing a curriculum specifically for people with HIV returning from incarceration. The curriculum was based on findings from our previous community-engaged research on barriers and facilitators to HIV treatment continuity for people with HIV returning from incarceration.17 Two trained facilitators, a peer (person with HIV who was formerly incarcerated) and a social worker, conducted the TCAC sessions and followed the 12-session curriculum over 6 months, with meetings every 2 weeks. TCACs comprised individual skill development and motivational enhancement strategies (post-release goal setting, stigma mitigation, livelihood strengthening, and HIV management), peer support strategies (facilitation of social support, including functional and emotional support), and provision of pre-packaged ART.

In a randomised controlled trial, we sought to test whether it was feasible to deliver the TCAC intervention and whether the intervention increased the proportion of participants enrolled in HIV treatment services within the first 6 months of community re-entry in South Africa.

Methods

Study design and participants

This study was an individually randomised pragmatic trial done in Gauteng, South Africa, one of six administrative regions of the South African Department of Correctional Services (DCS). Five correctional facilities were selected as study sites from two subregions (also referred to as management areas) in the DCS Gauteng Region. All correctional facilities had on-site ART programmes managed by nurses trained in HIV clinical management. Only one facility housed women. Human participant research approval was obtained from the University of the Witwatersrand Human Research Ethics Committee (M180509), the South African Department of Correctional Services Research Review Committee, and the Johns Hopkins Medicine Institutional Review Board (181117).

People who were incarcerated were eligible to participate if they were receiving ART at one of the study sites; were aged 18 years or older; were capable of providing informed consent; were scheduled for release in the study period; were willing to provide telephone or residential contact details for follow-up, including contact information for next of kin; and were planning to reside in or around the border of Gauteng after release (to reduce the burden of transport costs on participants for TCAC attendance). Study staff at each participating site worked with the correctional facility health staff and trained HIV peer educators from the correctional facility to recruit and identify people who met the eligibility criteria. Those who met eligibility criteria and were interested in participating were provided written and verbal information in Sepedi, isiZulu, isiXhosa, or Sesotho. All participants completed written informed consent before enrolment.

Randomisation and masking

Once consent was obtained, participants were randomly assigned (1:2) with block randomisation to either usual care or the TCAC, stratified by the two DCS management areas. Randomisation sequences were generated in the USA and sent to South Africa. The random allocation was sealed in opaque envelopes with participant identification numbers on the outside. In every block of nine, there were three allocations for usual care and six for TCACs. Field workers sequentially assigned participant identification numbers and opened envelopes in the presence of participants. Study team staff who recruited and implemented the strategy and participants were unmasked to randomisation assignment because of the behavioural nature of the intervention and the need to explain the study procedures to participants. Study assignments were masked to the investigators and staff doing outcome assessments until all outcome data were collected.

Procedures

After randomisation, participants were administered demographic and social–behavioural questionnaires that included duration of incarceration, history of testing for HIV and HIV treatment, perceived strength of relationship networks outside the correctional setting (social capital), HIV stigma, disclosure of HIV status, substance use, and depression. We assessed social capital using a 12-item adapted version of a World Bank bonding social capital assessment.18 HIV-related stigma was assessed using a five-point Likert scale on a 16-item adapted version of the People Living with HIV Stigma Index. Incarceration stigma was assessed by modifying the People Living with HIV Stigma Index. The index captured subscores for anticipated stigma and discrimination arising from from participants’ HIV status or incarceration history. Substance use was assessed by use of the WHO alcohol, smoking, and substance involvement screening tool (ASSIST).19 The ASSIST tool uses an eight-point Likert scale to capture the level of use of alcohol, stimulants, depressants, and opioids. Depression was assessed using a four-point Likert scale from the nine-item PHQ-9 depression screening tool.20

All TCAC sessions had two facilitators: one was a social worker, experienced in working with people on ART returning from incarceration; the other was a peer with a history of incarceration and HIV. Before release from correctional facilities, participants randomly assigned to the TCAC group each had an individual session with the two TCAC facilitators. These first sessions provided an opportunity to build rapport between TCAC facilitators and the participant and to identify participant needs. After release from correctional facilities, TCAC participants were contacted by telephone or in person (ie, through home visits) by a TCAC facilitator with whom they had their initial session within the first 15 days of release for a second one-on-one session. The second one-on-one session continued rapport building and expanded on identifying needs; introduced goal setting, prioritising, and planning; and assigned the participant to a TCAC venue based on their residential location. Four areas were selected for TCAC meeting venues based on post-release residence locations and proximity to a local public sector clinic for prepackaged ART.

The TCAC group meetings were conducted in private spaces in community venues (ie, two community halls, a community church, and the premises of a community-based organisation). All group members met for the first group session and continued to meet twice a month for all subsequent sessions. The TCAC sessions followed a 12-session curriculum (appendix pp 2–3) that covered goal setting, prioritisation, and planning; HIV and incarceration stigma; livelihood strengthening; and ART adherence. Each session had a facilitated group discussion of individual goals, challenges faced, and successes related to the previous session’s curriculum, followed by new curriculum content. New members were allowed to join an existing TCAC at any time before the sixth group session, which marked the completion of the first phase of the curriculum. The facilitators used one-on-one sessions to cover parts of the curriculum that new members missed before joining the TCAC. Participants were provided with a standard reimbursement of 100 South Africa Rands (US$6) equalling typical travel costs to TCAC group sessions. No reimbursements were provided for the time spent participating in the TCAC group sessions. TCAC participants were also referred by facilitators for additional community-based services such as social welfare schemes (eg, food parcels), harm reduction services, or employment recruitment agencies.

The facilitators received a comprehensive 7-day didactic and role-playing training on the underlying theory, the intervention components, and the use of the intervention manual. In addition, the facilitators met once every 2 weeks with study investigators during intervention delivery to discuss successes and challenges and to review content and technique for additional guidance on salient topic areas.

Participants in both groups were scheduled for telephone or in-person follow-up visits on days 30, 90, and 180 after release from the correctional facility. Information on changes in address and reincarceration was provided by the DCS Department of Community Corrections (parole officers) or the next-of-kin listed by the participants. The assessment at these follow-up visits included questions about enrolment in HIV treatment services and follow-up questions on social capital, HIV stigma, incarceration stigma, disclosure of HIV status, substance use, and depression. TCAC facilitators conducted assessments for participants randomly assigned to TCACs, and research assistants conducted them for those assigned to the usual care group.

Regarding harms, at each study follow-up visit, study staff assessed for unmanaged morbidity and involuntary disclosure of HIV status as a result of study-related home visits or participation in the TCACs. Participants were sensitised about these harms and the importance of reporting them during the informed consent process. Intervention facilitators completed a report form after each group session during which they were trained to note any harmful disruptions (including threats or actual violence) during the group session.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes were feasibility of TCAC delivery and participant follow-up, and TCAC effectiveness. The effectiveness outcome was enrolment in HIV treatment services at the 6-month visit measured by the proportion of participants or next-of-kin reporting whether participants had enrolled in HIV treatment services (ie, completed registration for HIV treatment or received HIV treatment) at any medical facility in South Africa. Participants without data on enrolment in HIV treatment were classified as having not enrolled in HIV treatment. As a secondary outcome we sought to assess harms, including reported inadvertent disclosure or safety concerns, by having facilitators ask session participants privately about involuntary disclosure of HIV status or history of incarceration and to document any concerns about safety to participants or themselves before, during, or after TCAC sessions.

Additional secondary outcomes of this study not included in this analysis are verified enrolment in HIV treatment services at the 6-month visit; time to linkage to care within the first 90 days of corrections release; virological suppression at 6 months from release; and changes in employment status, social capital, and stigma index scores. Trying to document or capture some of these outcomes during COVID-19 lockdowns (especially performing phlebotomy for HIV RNA) limited the collection of some of these data for many participants. The dissemination of social capital, stigma, and employment will be conducted through future publications. It should be noted that there were no adverse events.

Statistical analysis

Our feasibility outcome was based on a target of at least 90% of participants assigned to a specific TCAC and physically able to go to the TCAC venue (based on communication with TCAC facilitators) attending at least one TCAC session. We categorised participants who were reincarcerated and relocated outside Gauteng as not being able to physically attend the TCAC sessions. We selected a follow-up feasibility target of at least 75% of participants having an outcome determination using the exact method for 95% CIs.

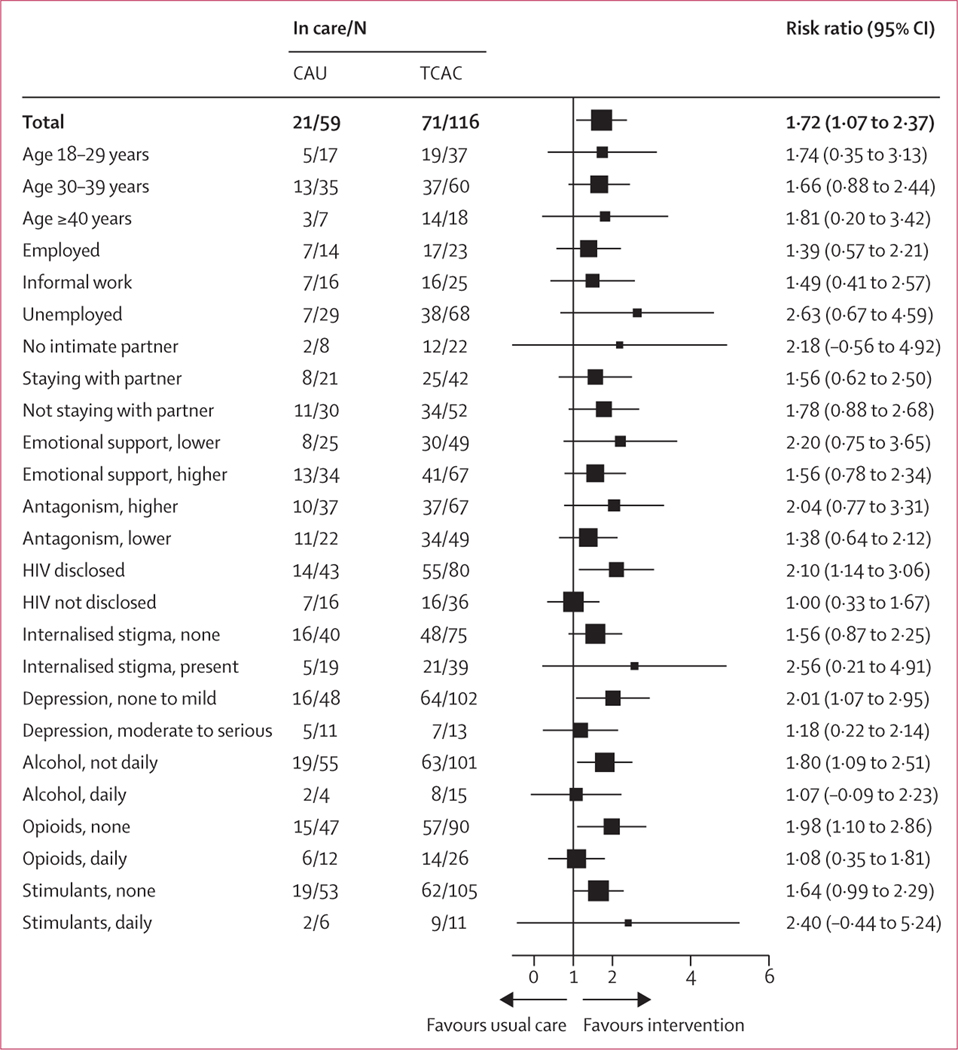

We estimated that a minimum sample size of 180 (60 in the care-as-usual group and 120 in the TCAC group) had 80% power with an α of 0·05 to identify an approximate difference in proportion meeting the primary outcome of 0·24 (eg, 0·25 vs 0·49 meeting the primary outcome). We assumed successful outcome ascertainment for 78% of participants (based on a previous study).9 Our primary analysis was an intention-to-treat analysis, including people who died, left South Africa, or were reincarcerated. We did subgroup analyses of prespecified subgroups that represented demographics of interest (age) and social or behavioural aspects touched on by the intervention: HIV status disclosure, emotional support, depression, substance use, and outgroup antagonism (ie, having negative attitudes towards those from different social, cultural, or demographic groups).21 We used log-binomial regression to calculate risk ratios (RRs) for the effect sizes and plotted effect sizes and CIs on a forest plot. We used χ2 testing to test for differences between proportions in outcomes. Stata 16 was used for all analyses (StataCorp). A data monitoring committee was not established for this trial, because this was a short-term pilot randomised controlled trial involving low risk to study participants. The trial was registered with the South African National Clinical Trials Register (DOH-27–0419–605) and ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03340428).

Role of the funding source

The funder of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Results

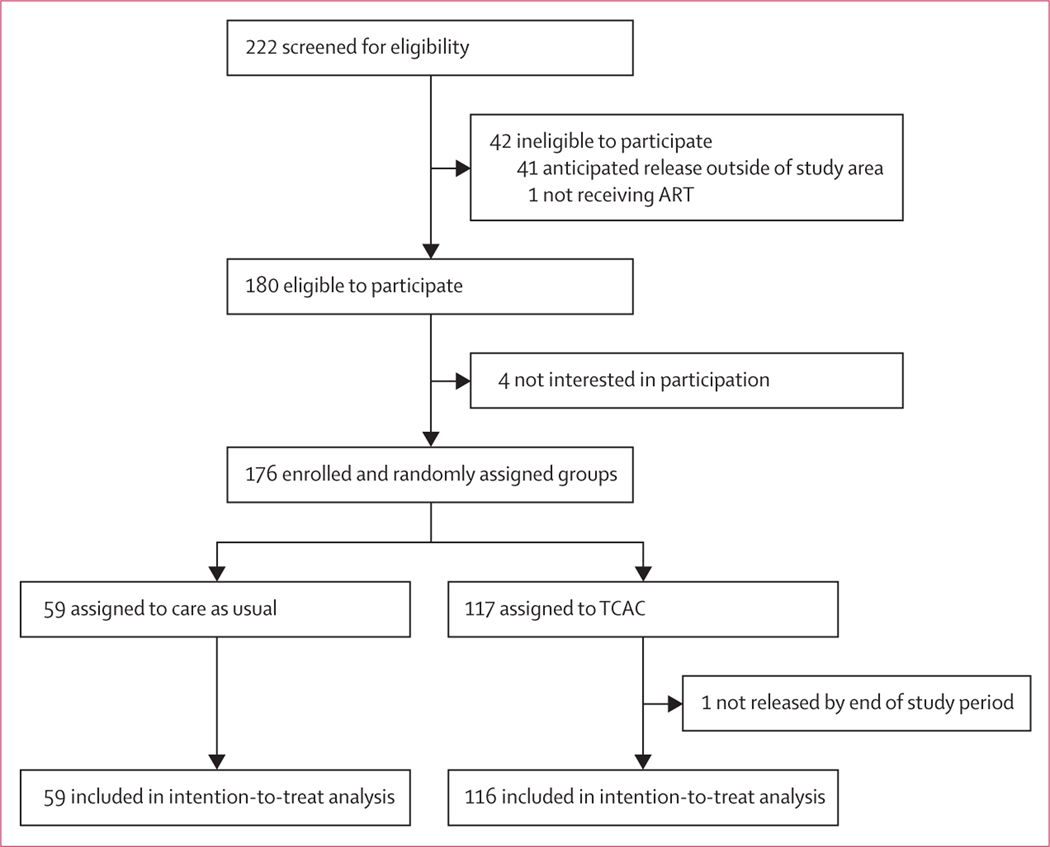

From March 1, 2019, to Dec 13, 2019, we screened 222 individuals; 180 were eligible for participation. The reasons for non-eligibility were not expecting to reside in or around the borders of Gauteng after release (n=41) and not being on ART at the time of screening (n=1; figure 1). Of the 180 eligible individuals, 176 consented to participate; four (2%) declined, stating “not being interested”. We randomly assigned 117 to the TCAC intervention group and 59 to the care-as-usual group. An administrative error led to an underenrolment by four participants (176 total); one participant assigned to the TCAC group was later excluded as a late exclusion because his incarceration was extended beyond the study period. Therefore, we included 175 participants for analysis.

Figure 1: Trial profile.

ART=antiretroviral therapy. TCAC=Transitional Community Adherence Club.

The baseline characteristics were balanced overall by the study group. Of 175 participants, most were men, median age was 33 years (IQR 29–37), and median duration of incarceration was 0·81 years (0·44–2·00). In addition, all participants were on ART at the time of release; 34% had initiated ART at community clinics before current incarceration, and 66% initiated ART during their current or a previous incarceration (table 1).

Table 1:

Participants characteristics at baseline

| Care as usual (n=59) | TCAC (n=116) | Total (N=175) | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Sex | |||

| Men | 56 (95%) | 110 (95%) | 166 (95%) |

| Women | 3 (5%) | 6 (5%) | 9 (5%) |

| Age, years | |||

| 21–29 | 17 (29%) | 37 (32%) | 54 (31%) |

| 30–39 | 35 (59%) | 61 (52%) | 96 (55%) |

| ≥40 | 7 (12%) | 18 (16%) | 25 (14%) |

| Incarceration history | |||

| Duration of current incarceration in years | 0·81 (0·49–1·95) | 0·82 (0·44–1·96) | 0·82 (0·44–1·96) |

| Previously incarcerated | 45 (76%) | 80 (69%) | 125 (71%) |

| Not previously incarcerated | 14 (24%) | 36 (31%) | 50 (29%) |

| Location of HIV diagnosis | |||

| HIV diagnosed in a correctional facility | 39 (66%) | 67 (57%) | 106 (60%) |

| HIV diagnosed elsewhere (not in a correctional facility) | 20 (34%) | 49 (43%) | 69 (40%) |

| Location of ART initiation | |||

| ART first initiated in a correctional facility | 39 (66%) | 76 (65%) | 115 (66%) |

| ART first initiated in the community | 20 (34%) | 40 (35%) | 60 (34%) |

| CD4 count before correctional facility release | |||

| CD4 count | 427 (281–580) | 517 (313–734) | 478 (299–677) |

| Last viral load (copies per mL) before release | |||

| <1000 | 26 (44%) | 52 (45%) | 78 (44%) |

| ≥1000 | 4 (7%) | 9 (8%) | 13 (8%) |

| Missing | 29 (49%) | 55 (47%) | 84 (48%) |

| Relationship status before incarceration | |||

| Not in an intimate relationship | 8 (14%) | 22 (19%) | 30 (17%) |

| In an intimate relationship and staying with a partner | 21 (35%) | 42 (36%) | 63 (36%) |

| In an intimate relationship and not staying with a partner | 30 (51%) | 52 (45%) | 82 (47%) |

| Employment status before incarceration | |||

| Full-time or part-time work | 14 (24%) | 23 (20%) | 37 (21%) |

| Informal work | 16 (27%) | 25 (21%) | 41 (23%) |

| Unemployed | 29 (49%) | 68 (59%) | 97 (56%) |

| Social support | |||

| Emotional support* | 16 (12–16) | 16 (8–16) | 16 (8–16) |

| Outgroup antagonism† | 12 (8–16) | 12 (6–16) | 12 (8–16) |

| Disclosure | |||

| Disclosed HIV status to family or friends | 43 (73%) | 80 (69%) | 123 (70%) |

| No disclosure of HIV status to family or friends | 16 (27%) | 36 (31%) | 52 (30%) |

| Enacted stigma on disclosure (of 123 participants who disclosed) | |||

| Experienced stigmatisation on HIV disclosure | 12 (28%) | 30 (33%) | 42 (32%) |

| No experiences of stigmatisation on HIV disclosure | 31 (72%) | 60 (67%) | 91 (68%) |

| Internalised stigma | |||

| Experiencing internalised HIV stigma | 19 (32%) | 39 (34%) | 58 (33%) |

| No experiences of internalised HIV stigma | 40 (68%) | 77 (66%) | 117 (67%) |

| Depression | |||

| None to mild | 48 (81%) | 102 (88%) | 150 (86%) |

| Moderate to severe | 11 (19%) | 14 (12%) | 25 (14%) |

| Alcohol use in the past three months (including during or before incarceration) | |||

| Alcohol, daily | 4 (7%) | 15 (13%) | 19 (11%) |

| Alcohol, none to less than daily | 55 (93%) | 101 (87%) | 156 (89%) |

| Illicit opioid use in the past three months (including during or before incarceration) | |||

| Opioids, daily | 12 (20%) | 26 (22%) | 38 (22%) |

| Opioids, non to less than daily | 47 (80%) | 90 (78%) | 137 (78%) |

| Stimulant use in the past three months (including during or before incarceration) | |||

| Stimulants, daily | 6 (10%) | 11 (9%) | 17 (10%) |

| Stimulants, none to less than daily | 53 (90%) | 105 (91%) | 158 (90%) |

Data are n (%) or median (IQR). TCAC=Transitional Community Adherence Club. ART=antiretroviral therapy.

Emotional support (range 0–16); a higher score indicates more support.

Outgroup antagonism (range 0–16); a higher score indicates less antagonism.

We successfully contacted the participant or next of kin to ascertain enrolment in HIV treatment services for 161 (92%) of 175 participants (meeting our follow-up feasibility goal of ≥75%). Among the 175 participants, 92 (52%) met the primary outcome of enrolment in HIV treatment services at any medical facility 6 months after release from correctional facility. Among 83 participants categorised as not having enrolled in HIV treatment services at 6 months after release, 41 (23%) were reported by family members to be living on the streets and not engaging with HIV treatment services, 19 (11%) were reincarcerated, three (2%) had died, six (3%) had left South Africa, and 14 (8%) had no outcomes reported by themselves or their next of kin.

In the TCAC group, 71 (61%) participants had enrolled in HIV treatment services at 6 months, compared with 21 (36%) participants in the care-as-usual group (RR 1·7, 95% CI 1·2–2·5; p=0·0010; table 2). In subgroup analyses, there were trends that individuals who had not disclosed HIV status to a friend or family member, had moderate to severe depression, used alcohol daily, or had an opioid use disorder might have had less benefit from the intervention (figure 2).

Table 2:

Primary outcome

| Care as usual | TCAC | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Number in study group | 59 | 116 |

| Relative risk (95% CI) | 1 (ref) | 1·7 (1·2–2·5) |

| p value | ·· | 0·001 |

| Enrolled in HIV treatment at 6 months, n (%) | 21 (36%) | 71 (61%) |

TCAC=Transitional Community Adherence Club.

Figure 2: Forest plot with subgroup analyses and risk ratio.

CAU=care as usual. TCAC=Transitional Community Adherence Club.

We assessed receipt of the intervention components (dose received) and feasibility of TCAC delivery. Of the 116 participants assigned to the intervention group, 59% (n=65) were successfully assigned to a specific TCAC post-release. Reasons for non-assignment to a TCAC were a failure of post-release contact (n=25); loss to follow-up after initial post-release contact (n=5); request not to attend a TCAC (n=2); and release from a correctional facility when group gatherings were prohibited due to COVID-19 related restrictions (n=19). Of the 65 participants assigned to a specific TCAC group post-release, 44 (68%) attended at least one TCAC session. Reasons for not attending were reincarceration (n=4), relocating outside of Gauteng province (n=6), working during TCAC session times (n=1), and lack of interest or ability to get to the session (n=10). Thus, 55 (85%) of 65 participants assigned to a specific TCAC group were considered physically able to attend at least one TCAC session (ie, excluding those reincarcerated and relocated outside Gauteng). Of those assigned to a TCAC group and physically able to attend, 44 (80%) of 55 succeeded in attending one or more sessions, coming close to achieving our TCAC delivery feasibility goal of 90% or more (appendix pp 4–5). Of the individuals assigned to a TCAC, the median number of sessions attended was five (IQR 4–8). From March 26, 2020 onwards, we could no longer hold group sessions because of COVID-19-related restrictions, reducing the possible number of sessions to fewer than 12 for most participants. ART provision within the TCAC sessions was not fully implemented, initially due to logistical factors, and subsequently due to restrictions related to COVID-19.

No adverse events were reported during TCAC sessions, including involuntary disclosure of HIV status disclosure, involuntary disclosure of incarceration history, or violence or threat of violence to study facilitators or participants during, before, or after TCAC sessions.

Discussion

In this randomised controlled trial, we found strong evidence that TCACs improved enrolment in HIV treatment services for a highly marginalised population. TCACs is a multilevel intervention comprising an adapted community adherence club model, with a curriculum and peer support designed specifically for people with HIV returning from incarceration. Our findings also suggest implementation feasibility of TCACs, except for a period when travel and gatherings were restricted because of COVID-19. Our findings highlight the substantial and continued unmet need for HIV treatment transitional services in South Africa: just over a third of participants receiving usual care enrolled in HIV treatment services within the first 6 months of release. Encouragingly, TCACs offer a potential model for treatment continuity interventions for people returning from incarceration.9 This study also extends existing principles of differentiated care that have proved valuable for people with well controlled HIV and consistent follow-up at a given clinic to a vulnerable population without a track record of community-clinic attendance.22

Several reasons exist why participants assigned to TCACs, compared with those who received usual care, might have achieved higher rates of enrolment in HIV treatment services at 6 months from the date of release. First, we believe incorporating peer support components was a key success factor for the TCACs. From previous formative qualitative research, we identified peer support during community re-entry as a highly valued attribute of transitional HIV care support.14 Some participants in this previous work identified community-based peer support structures as a continuation of the emotional support they received while incarcerated.14 Notably, similar preferences for peer support were identified in a discrete choice experiment among people with HIV returning from incarceration in Zambia.23 In further support of the importance of peer intervention components are the findings of a systematic review reporting on post-release HIV treatment engagement interventions. In that review, the only two behavioural intervention trials that showed improvements in outcomes both involved peer support.24 The mechanisms through which peer support interventions could improve desired health-care-seeking behaviour are well documented in literature.25–27 Notably, peer support in HIV care reduces internalised stigma and promote the modelling of positive health-seeking behaviours through mutual understanding, shared experiences, and shared identities.25,26 Participants in the TCAC groups specifically stated that they sought advice from group members and viewed peer facilitators as role models and guides.28 Some participants even found the experience transformative in increasing confidence and self-efficacy.28 The other components of the TCAC curriculum, namely individual skill development and motivational enhancement strategies, might have helped re-entrants prepare to positively adapt or provide the proper resources to remove encountered barriers.29 In turn, this help might have induced behavioural change to increase HIV care continuity.30 Lastly, given the high level of vulnerability of this population, COVID-19 lockdowns and the associated disruption in health services could have exacerbated challenges of community reintegration and navigating health-care services.31 The intervention might have overcome some of these effects, while those in the usual care group might have fared even worse than similar populations before the COVID-19 pandemic. This change could have contributed to the effect size of the intervention.

We believe that further assessments are warranted before the programmatic adoption of the TCAC model, including studies assessing outcomes of virological suppression and comparative assessments (including cost) to identify components of the TCAC that are both most effective and most feasible for programmatic scale-up. Some essential costs that influence attending TCAC sessions include opportunity costs of attending sessions and the travel costs incurred by participants or the TCAC programme.28 Although our findings from exploratory subgroup analyses need to be interpreted cautiously given the small sample size and limited power, they are helpful for hypothesis generation regarding potential areas for improvement. Areas for possible improvement include facilitation of HIV status disclosure and identification and management of mental health and substance use disorders. The integration of these components and evaluation of their effectiveness requires additional study. Despite TCACs being designed to circumvent clinic bureaucracy through the direct provision of ART to members during sessions, logistical barriers interfered with implementation. It is important for future studies to evaluate the additional contribution that ART delivery could have towards improving post-release HIV treatment continuity. In our qualitative acceptability assessment, the scarcity of ART provision was the only common criticism of the TCACs.28

Strengths of this study include achieving high enrolment and thus external validity, testing a multilevel intervention in a pragmatic setting, and using a randomised controlled design to generate strong evidence. However, because our study was conducted in an urban province in South Africa, our findings might not be generalisable to all people with HIV returning from incarceration, particularly those returning to rural communities. Further, COVID-19 restrictions made full intervention delivery impossible during periods when group gatherings were prohibited. Although TCAC facilitators made efforts to have individual sessions with the TCAC participants, the benefits of peer support were not fully realised during this period. The closure of clinics and restrictions on research activities in clinics during this period resulted in the inability of TCAC facilitators to access ART supplies from clinics for distribution at group sessions as planned. Also, due to COVID-19 restrictions preventing our study staff from accessing clinics and making home visits, we could not verify participants’ attendance for HIV treatment services. Coupled with the unmasking of study staff and participants to intervention assignment, this might have resulted in TCAC participants self-reporting more favourable outcomes than those in the care-as-usual group. To minimise the extent of overestimating linkage to HIV treatment, we made participants aware of the plans to verify all self-reported clinic visits (eg, clinic cards and records at health facilities). Although we could not access this documentation for all individuals reporting clinic attendance (due to COVID-19 restrictions on travel, home visits, and file review at clinics), the expectation of verification might have reduced over-reporting. Among participants we were unable to contact, we depended on family reports. Family members often reported that the participant had left home and was living on the streets and was not engaged in health care. It is possible that some of these individuals were receiving HIV treatment; however, we doubt these individuals were taking ART, given our previous experience.

Notably, the proportion of participants receiving usual care who self-reported enrolment in HIV treatment services in this study (36%) was lower than findings from a previous study by our study team in a similar study setting.9 In that study, 65% of people with HIV returning from incarceration self-reported enrolment in HIV treatment services within 3 months of release.9

This study builds on previous work from this group regarding transitions in South Africa and complements work conducted in Zambia regarding barriers to HIV treatment continuity following release from incarceration. The low proportion of participants in the care-as-usual group who enrolled in HIV treatment services within the first 6 months of community re-entry highlights the troubling gap of unmet need for HIV treatment transitional care services in South Africa. The current passive referrals from correctional facilities to community clinics and issuing of ART at the time of release are insufficient to address the complex barriers that impede timely enrolment in HIV treatment services for people with HIV returning from incarceration in South Africa.9,32 To achieve epidemic control in South Africa and other countries with a large population of people with HIV who also have criminal justice involvement, effective and locally feasible approaches to HIV treatment continuity need to be identified and scaled up.23

In this study, we successfully adapted the adherence club model to people with HIV returning to the community from incarceration by increasing the frequency of meetings, including a curriculum specifically for people released from incarceration, and providing peer modelling through facilitation by a peer living with HIV and having had an incarceration experience. Our approach of building skills and self-efficacy through structured group sessions is a reasonable model to build further HIV treatment continuity interventions for criminal justice-involved individuals in South Africa and elsewhere. We believe that further assessments are warranted before the programmatic adoption of a TCAC model, including studies assessing outcomes of virological suppression and comparative assessments (including cost) that identify components of the TCAC that are both most effective and most feasible for programmatic scale-up.

Supplementary Material

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

The first study from sub-Saharan Africa describing the transition from HIV treatment services received in correctional facilities to treatment in community clinics was from 2017. That study identified high attrition during this transition, with only 34% of people enrolling in HIV treatment within 90 days of release from incarceration. A meta-analysis of studies from high-income countries published in 2015 reported similarly low levels of HIV treatment continuity among people returning from incarceration: a median of 28% were engaged in HIV treatment services within 90 days of release. To date, multiple approaches have been tested to increase enrolment in HIV treatment for people returning from incarceration. All such studies have been conducted in high-income countries, with none from sub-Saharan Africa. Our 2020 systematic literature review, using a search strategy with terms related to post-incarceration and HIV, identified 27 studies of post-incarceration treatment retention interventions that were published between Jan 1, 1990, and June 1, 2018. Of these studies, nine were prospective randomised trials, of which four reported a significant improvement in an HIV-continuum outcome; two were within the general incarcerated population and included a peer component in the intervention, the other two focused on the management of substance use disorders among individuals with a substance use disorder. We repeated the search using the same terms as we used in the systematic review for the period between June 1, 2018, and Feb 1, 2023, and identified one additional study. That study, from the USA, used a case management approach and reported a non-significant difference in HIV treatment service engagement during community re-entry. None of these previous studies were from low-income or middle-income settings, highlighting a gap in the evidence.

A second goal of this study was to extend the use of differentiated models of care. We did a literature search for prospective trials of differentiated models of care for higher risk individuals published between Jan 1, 2010, and Feb 1, 2023, with the terms (“differentiated model of care” OR “differentiated care”) AND (“high-risk” OR prison OR incarceration OR “key population”) AND HIV; we did not identify any reports of the use of differentiated models of care for this population (or other vulnerable or marginalised populations), indicating another gap in the evidence.

Added value of this study

To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first from sub-Saharan Africa to test the feasibility or effectiveness of an intervention to increase engagement in HIV treatment for people living with HIV who are returning to the community from incarceration. In addition, this is one of the few studies globally to show superiority of a specific intervention in improving the post-release HIV care continuum. We showed that a differentiated model of care using a peer-based intervention with regular structured group meetings and ART provision increased enrolment in HIV treatment services at 6 months following release from incarceration, with an increase from 36% to 61% (p=0·0010).

Implications of all the available evidence

Our study adds to the evidence base of multilevel interventions to improve HIV treatment engagement overall and specifically among individuals returning from incarceration. We also extended understanding of the role of peers to support HIV treatment continuity for this population. The study findings advance existing principles of differentiated models of care to a vulnerable population facing complex challenges that hamper transition in HIV treatment services.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the study teams that conducted this study, and to all study participants involved. We thank the National Institutes of Health for funding this work (reference NIH R34MH115777).

Funding

National Institute of Mental Health.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

We declare no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Tonderai Mabuto, Department of Implementation Research, The Aurum Institute, Johannesburg, South Africa.

Daniel M Woznica, Society of Critical Care Medicine, Mount Prospect, IL, USA.

Pretty Ndini, Department of Implementation Research, The Aurum Institute, Johannesburg, South Africa.

Derrick Moyo, Department of Implementation Research, The Aurum Institute, Johannesburg, South Africa.

Munazza Abraham, Department of Psychology, University of Maryland, College Park, MD, USA.

Colleen Hanrahan, Department of Epidemiology, Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Salome Charalambous, Department of Implementation Research, The Aurum Institute, Johannesburg, South Africa; The University of the Witwatersrand School of Public Health, Johannesburg,South Africa.

Barry Zack, The Bridging Group, Oakland, CA, USA.

Prof Stefan Baral, Department of Epidemiology, Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Jill Owczarzak, Department of Health, Behavior, and Society, Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Christopher J Hoffmann, The University of the Witwatersrand School of Public Health, Johannesburg,South Africa; Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Data sharing

Given the sensitivity of the data due to the social and legal context in South Africa, deidentified participant data, along with supporting documentation (study protocol, data dictionary), are available upon request from the corresponding author pending appropriate Institutional Review Board and institutional (South Africa Department of Correctional Services, Aurum Institute, and Johns Hopkins University) leadership approval.

References

- 1.Walmsley R, Fair H. World prison population list. Home Office London, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 2.UNAIDS. UNAIDS data 2020. 2020. https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2020_aids-data-book_en.pdf (accessed Aug 5, 2020).

- 3.UNAIDS. UNAIDS data 2021. 2021. https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2021/2021_unaids_data (accessed March 1, 2023).

- 4.South Africa National Department of Health. Adherence guidelines for HIV, TB and NCDs. Pretoria: National Department of Heath, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Department of Correctional Services. Department of Correctional Services annual report 2020/2021 financial year. 2021. https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/202110/dcs-annual-report-2020-21.pdf (accessed April 17, 2022).

- 6.Telisinghe L, Charalambous S, Topp SM, et al. HIV and tuberculosis in prisons in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet 2016; 388: 1215–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Telisinghe L, Hippner P, Churchyard GJ, et al. Outcomes of on-site antiretroviral therapy provision in a South African correctional facility. Int J STD AIDS 2016; 27: 1153–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Topp SM, Chetty-Makkan CM, Smith HJ, et al. “It’s not like taking chocolates”: factors influencing the feasibility and sustainability of universal test and treat in correctional health systems in Zambia and South Africa. Glob Health Sci Pract 2019; 7: 189–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mabuto T, Woznica DM, Lekubu G, et al. Observational study of continuity of HIV care following release from correctional facilities in South Africa. BMC Public Health 2020; 20: 324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baillargeon JG, Giordano TP, Harzke AJ, Baillargeon G, Rich JD, Paar DP. Enrollment in outpatient care among newly released prison inmates with HIV infection. Public Health Rep 2010; 125 (suppl 1): 64–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Binswanger IA, Blatchford PJ, Mueller SR, Stern MF. Mortality after prison release: opioid overdose and other causes of death, risk factors, and time trends from 1999 to 2009. Ann Intern Med 2013; 159: 592–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Springer SA, Pesanti E, Hodges J, Macura T, Doros G, Altice FL. Effectiveness of antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected prisoners: reincarceration and the lack of sustained benefit after release to the community. Clin Infect Dis 2004; 38: 1754–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith HJ, Herce ME, Mwila C, et al. Experiences of justice-involved people transitioning to HIV care in the community after prison release in Lusaka, Zambia: a qualitative study. Glob Health Sci Pract 2023; 11: e2200444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rabinovich R, Owczarzak J, Mabuto T, Ntombela N, Woznica D, Hoffmann CJ. Social support needs of HIV-positive individuals reentering community settings from correctional facilities in Johannesburg, South Africa. AIDS Care 2022; 34: 1347–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woznica DM, Ntombela N, Hoffmann CJ, et al. Intersectional stigma among people transitioning from incarceration to community-based HIV care in Gauteng province, South Africa. AIDS Edu Prev 2021; 33: 202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.South Africa National Department of Health. 2019 ART clinical guidelines for the management of HIV in adults, pregnancy, adolescents, children, infants and neonates. 2019. https://www.nicd.ac.za/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/2019-ART-Clinical-Guidelines-25-Nov.pdf (accessed Jan 21, 2020).

- 17.Mqedlana N, Owczarzak J, Woznica M. Daniel, Mabuto T, Hoffmann CJ. Navigating HIV treatment seeking and access post prison release. 9th SA AIDS Conference; June 13, 2019 (abstr 469). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grootaert C. Measuring social capital: an integrated questionnaire. 2004. 10.1596/0-8213-5661-5 (accessed Oct 14, 2018). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.WHO. The Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST): manual for use in primary care. 2010. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/978924159938-2 (accessed May 1, 2018).

- 20.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001; 16: 606–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sasse J, Spears R, Gordijn EH. When to reveal what you feel: how emotions towards antagonistic out-group and third party audiences are expressed strategically. PLoS One 2018; 13: e0202163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grimsrud A, Bygrave H, Doherty M, et al. Reimagining HIV service delivery: the role of differentiated care from prevention to suppression. J Int AIDS Soc 2016; 19: 21484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ostermann J, Yelverton V, Smith HJ, et al. Preferences for transitional HIV care among people living with HIV recently released from prison in Zambia: a discrete choice experiment. J Int AIDS Soc 2021; 24: e25805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Woznica DM, Fernando NB, Bonomo EJ, Owczarzak J, Zack B, Hoffmann CJ. Interventions to improve HIV care continuum outcomes among individuals released from prison or jail: systematic literature review. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2021; 86: 271–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Øgård-Repål A, Berg RC, Fossum M. Peer support for people living with HIV: a scoping review. Health Promot Pract 2023; 24: 172–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tobin KE, Heidari O, Winiker A, et al. Peer approaches to improve HIV care cascade outcomes: a scoping review focused on peer behavioral mechanisms. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2022; 19: 251–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tobias CR, Rajabiun S, Franks J, et al. Peer knowledge and roles in supporting access to care and treatment. J Community Health 2010; 35: 609–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.An Y, Ntombela N, Hoffmann CJ, Fashina T, Mabuto T, Owczarzak J. “That makes me feel human”: a qualitative evaluation of the acceptability of an HIV differentiated care intervention for formerly incarcerated people re-entering community settings in South Africa. BMC Health Serv Res 2022; 22: 1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action. Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoffmann CJ, Mabuto T, McCarthy K, Maulsby C, Holtgrave DR. A framework to inform strategies to improve the HIV care continuum in low- and middle-income countries. AIDS Edu Prev 2016; 28: 351–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dorward J, Khubone T, Gate K, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 lockdown on HIV care in 65 South African primary care clinics: an interrupted time series analysis. Lancet HIV 2021; 8: e158–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.South Africa National Department of Health. Guidelines for the management of tuberculosis. Human immunodeficiency virus and sexually-transmitted infections in correctional centres. 2013. https://www.tbonline.info/media/uploads/documents/guidelines_for_the_management_of_tuberculosis%2C_human_immunodeficiency_virus_and_sexually-transmitted_infections_in_correctional_facilities_%282013%29.pdf (accessed April 15, 2013).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Given the sensitivity of the data due to the social and legal context in South Africa, deidentified participant data, along with supporting documentation (study protocol, data dictionary), are available upon request from the corresponding author pending appropriate Institutional Review Board and institutional (South Africa Department of Correctional Services, Aurum Institute, and Johns Hopkins University) leadership approval.