Abstract

Objectives:

To summarize evidence-based cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) treatment and propose clinical interventions for adult patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

Methods:

The literature on CBT interventions for adult OCD, including BT and exposure and response prevention, was systematically reviewed to develop updated clinical guidelines for clinicians, providing comprehensive details about the necessary procedures for the CBT protocol. We searched the literature from 2013-2020 in five databases (PubMed, Cochrane, Embase, PsycINFO, and Lilacs) regarding study design, primary outcome measures, publication type, and language. Selected articles were assessed for quality with validated tools. Treatment recommendations were classified according to levels of evidence developed by the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association.

Results:

We examined 44 new studies used to update the 2013 American Psychiatric Association guidelines. High-quality evidence supports CBT with exposure and response prevention techniques as a first-line treatment for OCD. Protocols for Internet-delivered CBT have also proven efficacious for adults with OCD.

Conclusion:

High-quality scientific evidence supports the use of CBT with exposure and response prevention to treat adults with OCD.

Keywords: Obsessive-compulsive disorder, practice guideline, cognitive-behavioral therapy, exposure and response prevention, systematic review

Introduction

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a common mental health condition marked by intrusive and disturbing thoughts (obsessions) and their associated repetitive behaviors (compulsions). OCD is a leading cause of disability worldwide.1-3 According to the National Comorbidity Survey Replication, the lifetime prevalence of OCD is 2.3% and the 12-month prevalence is 0.7%.2 Andrade et al.4 reported that the 1- and 12-month prevalences of OCD were 0.3% in São Paulo (Brazil). If untreated, OCD usually follows a chronic waxing and waning pattern, with only 5 to 10% of patients achieving spontaneous remission.5,6 Some patients with OCD are resistant to conventional treatment.7 OCD is currently recognized as a common, highly disabling, and potentially treatable early-onset brain disorder.8

The first-line treatment for OCD is selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in association with cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT).9,10 The efficacy of CBT for OCD is well recognized.9 However, despite the efficacy of these evidence-based treatments, almost half of patients with OCD do not respond adequately to them.11,12 Thus, clinical guidelines based on high-quality evidence are necessary for clinicians and must be updated regularly.

The most effective treatment for OCD consists of CBT involving exposure and response prevention (ERP) and cognitive therapy.13 During ERP, patients are exposed to their feared stimuli while practicing “not” performing their customary compulsions. CBT is then aimed at training patients to deal with their obsessions in more appropriate ways.

Inspired by Mowrer’s two-factor theory, Meyer14 developed a seminal version of what would later be called ERP. The procedure is characterized by: 1) identifying, in partnership with the patient, elements that promote obsessions and compulsions and organizing them into a hierarchy of discomfort; 2) facing such scenarios; and 3) suppressing responses that reinforce such elements. As summarized by Hezel & Simpson,15 ERP must be tailor-made and can be structured in a variety of ways (e.g., respecting the hierarchy, intensively, in vivo or through imagined exposure, in a health care center or not). Regarding its mechanisms of action, until the 2000s, it was believed that the efficacy of ERP was due to its ability to break historically established conditional relationships (extinction paradigm). However, Craske et al.16 showed that when patients are exposed to feared stimuli and invited to refrain from avoidant tendencies, they learn alternative ways to relate to events that inhibit compulsions (inhibitory learning paradigm). ERP is considered the psychological treatment of choice for OCD.17 Although OCD symptoms are diverse, this technique can be applied to any type of symptom, including different symptom dimensions. Given the heterogeneity of the condition, clinicians would benefit from a systematic set of guidelines derived from the CBT literature that support the delivery of ERP and CT in a wide range of clinical settings.18

This is the second in a series of four articles on the most frequent treatments for adults with OCD (pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, neuromodulation, and neurosurgery). The first provided the most up-to-date clinical guidelines on the pharmacological treatment of adult OCD patients.19 The objective of this study is to present up-to-date clinical guidelines for clinicians that provide comprehensive details on which procedures should be incorporated into the CBT protocol. CBT is considered a first-line treatment for OCD, aiming to reduce severity in adult patients. These guidelines aim to establish the essential components of an evidence-based CBT protocol, equipping clinicians with pertinent information, such as the required number of sessions, specific techniques, and the format, frequency, and duration of sessions. We conducted a systematic review of the literature in five prominent databases. After the search, we thoroughly evaluated the quality of the studies selected to address the questions raised in this review.

Methods

Overview

This review was conducted by psychiatrists and psychologists from a number of Brazilian academic institutions with extensive experience in OCD treatment. Given that the most recent national clinical guidelines for OCD treatment were published in 2011,17 our initial goal was to review the most recent findings to update our clinical guidelines. Our ultimate aim was to provide an improved tool to guide the decision-making processes of psychologists, psychiatrists, and general practitioners who treat patients with OCD.

The Brazilian Ministry of Health’s Methodological Guideline for Developing Clinical Guidelines guided the production of this guideline. In addition, a systematic review of articles published from 1966 to 2013 was conducted to update two previous international treatment guidelines for OCD.20,21

The present guideline was registered in the Practice Guideline Registry Platform (IPGRP-2021CN324).

The definition and construction of the research questions

The psychotherapy workgroup consisted of three cognitive behavior therapists (MAM, RB, and PC) with extensive experience in the psychotherapeutic treatment of OCD. Relevant questions were defined after meeting with other experts in the field, and the questions were formulated according to the PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparator, and Outcome) framework.

Box 1 describes the final research questions after reaching consensus among the experts.

Box 1. Research questions.

| Psychological treatments |

|---|

| Research questions |

| 1. Is CBT superior to control interventions in reducing OCD symptoms in adult patients with OCD? |

| 2. What are the specific techniques and interventions (number of sessions, individual or group sessions) for patients with OCD? |

| 3. Is there an efficacy difference between treatment with SSRIs and CBT? |

| 4. Is there a difference between CBT and an association of CBT and SSRIs in treatment for patients with OCD? |

| 5. Are there any effective augmentation strategies for CBT? Is CBT the best augmentation strategy for pharmacotherapy in OCD? |

| 6. What is the level of adherence to CBT? |

| 7. What is the efficacy of Internet-based CBT for patients with OCD? |

CBT = cognitive-behavioral therapy; OCD = obsessive-compulsive disorder; SRRIs = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

Search strategy

We used the American Psychiatric Association treatment guidelines as a starting point for this study.20 Articles published from 1966 to 2004 were originally included in this guideline, but this was later expanded to those published between 2004 and 2013.20,21 The five databases used in this investigation were PubMed, Cochrane, Embase, PsycINFO, and LILACS. The keywords and MeSH terms used to conduct this search can be found in Table S1 (379KB, pdf) , available as online-only supplementary material.

Inclusion criteria

Our inclusion criteria covered study design, primary outcome measure, publication type, language, and year of publication. Specifically, we selected meta-analyses, systematic reviews, and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) conducted with adult OCD patients that were published between 2013 and 2020. Clinical trials examining pre- and post-treatment OCD severity with the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS)22 as the primary outcome measure were eligible for inclusion in this review. The response criterion in these studies was the difference between the initial and final Y-BOCS score (pre- vs. post-treatment), which reduced between 25% and 35%. We restricted our search to studies published in English. Only articles not previously assessed in other meta-analyses were included in this review. Finally, we included meta-analyses published from 1966 to 2013 that were not used in the American Psychiatric Association guidelines.21

Article selection

Initial article selection was performed independently by the three members of the psychotherapy workgroup. Discrepancies were resolved among workgroup members using a best estimate diagnosis strategy. After initial screening, the authors determined the eligibility of all relevant full-text articles using Rayyan software.23

Quality assessment

The Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) scale was used to evaluate randomized clinical trials.24 PEDro is a tool designed to evaluate the methodological quality of RCTs from physical therapy and other health disciplines. Each of the 11 items on the scale is scored as yes (1) or no (0). The overall score is the sum of the positive answers, i.e., ranging from 0 to 11. Both the questions and the scores for the included trials are presented in Table S2 (379KB, pdf) .

The Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) was used to assess the quality of the included systematic reviews and meta-analyses.25 AMSTAR is a validated tool for determining the methodological quality of systematic reviews. Each item is scored as yes, no, can’t answer, or not applicable. Yes indicates that the systematic review meets the criteria, while any other answer indicates that it does not. The overall quality of the systematic review is then rated according to the number of yes responses. Both the questions and the scores for the included articles are presented in Table S3 (379KB, pdf) .

Recommendations for psychotherapy were hierarchically organized according to the relevance and quality of the evidence. The quality assessment results for RCTs and meta-analyses can be found in Tables S2 and S3 (379KB, pdf) .

Recommendations and levels of evidence

The recommendations were classified according to level of evidence using the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Recommendation System, applying recommendation class and level of evidence to clinical strategies, interventions, treatments, or diagnostic testing26 after answering the PICO questions.

Results

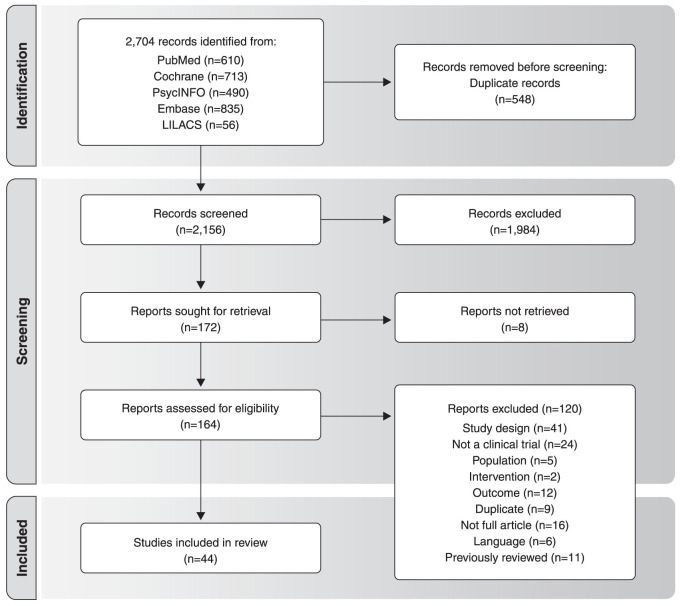

The database search identified 2,704 records. In the second phase, each of the three reviewers carefully analyzed all 2,704 abstracts, of which 2,156 were screened out for not meeting the inclusion criteria. In the third phase, 172 records were read in full and assessed for eligibility. Figure 1 presents the study selection flowchart, designed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement.27 Of the 172 articles assessed for eligibility, 120 did not meet all inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Thus, 44 articles were included in this review after removing articles previously assessed in other meta-analyses. The excluded studies and reasons for their exclusion can be found in Table S4 (379KB, pdf) , available as online-only supplementary material. A summary of the studies can be found in Table 1.

Figure 1. Inclusion flowchart, based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement, for studies on psychotherapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Table 1. Description of the studies (RCTs and meta-analysis).

| Title and journal | First author | (n) intervention and control | Main results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Does the addition of cognitive therapy to exposure and response prevention for obsessive compulsive disorder enhance clinical efficacy? A randomized controlled trial in a community setting British Journal of Clinical Psychology |

Rector et al.28 | N=127 with OCD were randomly assigned to receive individual outpatient ERP or ERP + CT. | ERP + CT led to significantly greater symptom and belief reduction compared to ERP across all main symptom presentations of OCD. |

| 2 | A randomized waitlist-controlled trial comparing detached mindfulness and cognitive restructuring in obsessive-compulsive disorder PloS ONE |

Rupp et al.29 | N=43 participants were randomly assigned to either DM or CR.N=21 participants had been previously assigned to a 2-week waitlist condition. | The results suggest the potential efficacy of DM as a stand-alone intervention for OC. Both CR and DM should be considered as possible alternative treatments for OCD, whereas the working mechanisms of DM have yet to be elucidated. |

| 3 | Effectiveness of Exposure/Response prevention plus eye movement desensitization and reprocessing in reducing anxiety and obsessive-compulsive symptoms associated with stressful life experiences: A randomized controlled trial Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences |

Sarichloo et al.30 | N=60 participants were randomly assigned to the ERP plus EMDR group (n = 30) or the ERP (n=30) group. | Compared to the ERP protocol, the ERP plus EMDR protocol had a higher rate of OCD treatment completion and efficacy. |

| 4 | Unguided Internet-based cognitive-behavioral therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: A randomized controlled trial Depression and Anxiety |

Schröder et al.31 | N=128 individuals with self-reported OCD symptoms were randomly allocated to either an intervention group (unguided iCBT) or to a care-as-usual control group. | Unguided iCBT for OCD may be a viable option for individuals who experience treatment barriers. |

| 5 | Cognitive-behavioral therapy vs risperidone for augmenting serotonin reuptake inhibitors in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a randomized clinical trial JAMA Psychiatry |

Simpson et al.32 | N=100 were randomized (risperidone, n=40; EX/RP, n=40; and placebo, n=20). | Adding EX/RP to SRIs was superior to both risperidone and pill placebo. Patients with OCD receiving SRIs who continue to have clinically significant symptoms should be offered EX/RP before antipsychotics, given its superior efficacy and less negative adverse effect profile. |

| 6 | A randomized clinical trial of cognitive-behavioral group therapy and sertraline in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder Journal of Clinical Psychiatry |

Sousa et al.33 | N=56 participated in the randomized clinical trial: 28 took 100 mg/day of sertraline and 28 underwent CBGT for 12 weeks. | CBGT and sertraline effectively reduced OCD symptoms. The rate of symptom reduction, compulsion intensity reduction, and percentage of patients who obtained full remission were significantly higher among patients treated with CBGT. |

| 7 | Behavior therapy augments response of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder responding to drug treatment Journal of Clinical Psychiatry |

Tenneij et al.34 | N=96 patients who had responded to 3 months of drug treatment were randomly assigned to receive either added BT or drug treatment alone for 6 months. | Adding BT is beneficial for patients who have responded to drug treatment. The data also suggest that the effect is greater when BT is added immediately after attaining a drug response. |

| 8 | A randomized controlled trial of self-directed versus therapist-directed cognitive-behavioral therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder patients with prior medication trials Behavior Therapy |

Tolin et al.35 | N=41 adult outpatients who reported at least one current or previous adequate medication trial were randomly assigned to self-administered or therapist-administered ERP. | Patients in both treatment conditions showed statistically and clinically significant symptom reduction. However, patients receiving therapist-administered ERP showed a superior response in terms of OCD symptoms and self-reported functional impairment. |

| 9 | Adding acceptance and commitment therapy to exposure and response prevention for obsessive-compulsive disorder: A randomized controlled trial Behaviour Research and Therapy |

Twohig et al.36 | N=58 adults engaged in a multisite randomized controlled trial of 16 individual twice-weekly sessions of ERP or ACT + ERP. | CT + ERP and ERP were both highly effective treatments for OCD, and no differences were found in outcomes, processes of change, acceptability, or exposure engagement. |

| 10 | The treatment of obsessive‐compulsive checking: A randomized trial comparing danger ideation reduction therapy with exposure and response prevention Clinical Psychologist |

Vaccaro et al.37 | N=50 OCD patients were randomly allocated to either the DIRT for obsessive‐compulsive checkers DIRT‐C (n=28) or ERP treatment (n=22). | This study provides further evidence of the usefulness of the DIRT‐C package for people with the OCD checking subtype. |

| 11 | Cognitive and behavioral therapies alone versus in combination with fluvoxamine in the treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease |

Van Balkom et al.38 | N=117 patients were randomized to one of the following five conditions: 1) CT for weeks 1 to 16; 2) exposure in vivo with response prevention for weeks 1 to 16; 3) fluvoxamine for weeks 1 to 16 plus CT in weeks 9 to 16; 4) fluvoxamine for weeks 1 to 16 plus exposure in vivo with response prevention in weeks 9 to 16; or 5) WL control condition for weeks 1 to 8 only. | In OCD, a sequential combination of fluvoxamine with CT or exposure in vivo with response prevention was not superior to either cognitive therapy or exposure in vivo alone. |

| 12 | Cognitive therapy versus fluvoxamine as a second-step treatment in obsessive-compulsive disorder nonresponsive to first-step behavior therapy Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics |

Van Balkom et al.39 | N=118 subjects with OCD treated with 12 weeks of ERP, 48 appeared to be nonresponders (Y-BOCS improvement score of less than one third). These nonresponders were randomized to CT (n=22) or fluvoxamine (n=26). | OCD patients who are nonresponsive to ERP may benefit more from a switch to treatment with an antidepressant instead of switching to CT. |

| 13 | Inference-based approach versus cognitive behavioral therapy in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder with poor insight: A 24-session randomized controlled trial Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics |

Visser et al.40 | N=90 patients with OCD and poor insight received either 24 CBT sessions or 24 IBA sessions. | Patients with OCD and poor insight improved significantly after psychological treatment. The results of this study suggest that both CBT and IBA are effective treatments for OCD with poor insight. |

| 14 | Remote treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder: a randomized controlled trial Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders |

Wootton et al.41 | N=56 OCD patients were randomly allocated to the guided bCBT Group (n=20), the guided iCBT (n=17) group, or the control group (n=19). | Results from the control group, after receiving iCBT treatment, indicated that large effect sizes can be obtained with weekly contact. These results provide preliminary support for the use of either bCBT or iCBT in the remote treatment of OCD. |

| 15 | Self-guided Internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy (ICBT) for obsessive-compulsive symptoms: A randomized controlled trial Journal of Anxiety disorders |

Wootton et al.42 | N=190 participants were randomized to either a self-guided iCBT group or a waitlist control group. | The results indicate that self-guided iCBT may be a viable treatment option for some individuals with OCD symptoms. |

| 16 | Long-term efficacy of Internet-based cognitive behavior therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder with or without booster: a randomized controlled trial Psychological Medicine |

Andersson et al.43 | N=101 participants were included in the long-term follow-up analysis of iCBT. Of these, 93 were randomized to a booster program or no booster program. | The results suggest that iCBT has sustained long-term effects and that adding an Internet-based booster program can further improve long-term outcomes and prevent relapse for some OCD patients. |

| 17 | The effect of treatment on quality of life and functioning in OCD Comprehensive Psychiatry |

Asnaani et al.44 | N=100 adults with OCD on SRIs were enrolled in a randomized clinical trial comparing SRI augmentation with EX/RP therapy, risperidone, or pill placebo. | Improvements in quality of life/functioning were associated with reduced OCD symptom severity. |

| 18 | Group cognitive-behavioral therapy versus SSRIs for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a practical clinical trial Journal of Anxiety Disorders |

Belotto-Silva et al.11 | N=158 adults with OCD were sequentially allocated for treatment with GCBT (n=70) or fluoxetine (n=88). | Response rates to both treatments were similar and lower than those reported in the literature, probably due to the broad inclusion criteria and the resulting sample similar to the real world population. |

| 19 | Need for speed: evaluating slopes of OCD recovery in behavior therapy enhanced with d-cycloserine Behavior Research and Therapy |

Chasson et al.45 | N=22 adults with OCD were randomized in controlled trial of ERP + DCS vs. ERP + placebo. | DCS did not amplify the effects of ERP but instead initiated treatment effects sooner in treatment. |

| 20 | A randomized controlled trial of cognitive therapy versus intensive behavior therapy in obsessive compulsive disorder Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics |

Cottraux et al.46 | N=65 outpatients with OCD were randomized into two groups for 16 weeks of individual treatment in three centers. Group 1 received 20 sessions of CT. Group 2 received a BT program of 20 hours in two phases: 4 weeks of intensive treatment (16 hours) and 12 weeks of maintenance sessions (4 hours). | CT and BT were equally effective in OCD but, at post-test, CT had specific effects on depression that were stronger than those of BT. Pathways to improvement may be different in CT and BT. |

| 21 | Cognitive-behavioral therapy versus transcranial direct current stimulation for augmenting SSRIs in obsessive-compulsive disorder patients Basic and Clinical Neuroscience |

Dadashi et al.47 | N=26 OCD patients were randomly assigned to two treatment groups: ERP (n=13) or tDCS (n=13). | Although the present findings revealed no significant difference between the ERP and tDCS groups (except for quality of life), the pharmacotherapy-ERP combination proved more effective than pharmacotherapy-tDCS in treating OCD patients. |

| 22 | D-cycloserine addition to exposure sessions in the treatment of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder European Psychiatry |

De Leeuw et al.48 | N=39 patients with OCD were randomized. Patients received six guided exposure sessions once a week. One hour before each session, 125 mg DCS or placebo was administered. | The results of this study did not support the application of DCS to exposure therapy in OCD. Some specific aspects need further investigation: the efficacy of DCS in a larger ‘cleaning/contamination’ (sub-)group, DCS addition only after successful sessions, and interaction with antidepressants. |

| 23 | Optimal treatment for obsessive compulsive disorder: a randomized controlled feasibility study of the clinical-effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy, SSRIs and their combination in the management of obsessive compulsive disorder Clinical Psychopharmacology |

Fineberg et al.49 | N=49 adults with OCD were randomly assigned to CBT, SSRI, or SSRI + CBT. | Combined treatment appeared the most clinically effective option, especially over CBT, but the advantages over SSRI monotherapy were not sustained beyond 16 weeks. SSRI monotherapy was the most cost-effective treatment. |

| 24 | Six-month outcomes from a randomized trial augmenting serotonin reuptake inhibitors with exposure and response prevention or risperidone in adults with obsessive-compulsive disorder The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry |

Foa et al.50 | N=100 patients on therapeutic SRI dose with at least moderate OCD severity were randomized to 8 weeks of EX/RP, risperidone, or pill placebo. | The finding that 50% of patients randomized to EX/RP had minimal symptoms at 6-month maintenance, a rate double that of prior studies, suggests that EX/RP maintenance helps maximize long-term outcome. |

| 25 | Combination of behavior therapy with fluvoxamine in comparison with behavior. Results of a multicentre study British Journal of Psychiatry |

Hohagen et al.51 | N=30 patients were treated for 9 weeks with BT plus placebo and 30 patients with BT plus fluvoxamine. | The results suggest that BT should be combined with fluvoxamine when obsessions dominate the clinical picture and when secondary depression is present. |

| 26 | Highly efficacious cognitive-coping therapy for overt or covert compulsions Psychiatry Research |

Hu et al.52 | N=215 OCD patients were randomized into pharmacotherapy plus psychological support (n=107) or PCCT (n=108). | The results suggest that PCCT could efficaciously treat OCD with overt or covert compulsions, suggesting that PCCT might be a potential option for adult OCD. |

| 27 | A promising randomized trial of a new therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder Brain and Behavior |

Hu et al.53 | N=108 patients with OCD were randomly allocated into three groups: pharmacotherapy (n=38), pharmacotherapy plus CBT (PCBT, n =34), or pharmacotherapy plus CCT (PCCT, n=36). | The preliminary data suggest that PCCT is a more efficacious psychotherapy for OCD patients than pharmacotherapy or PCBT. |

| 28 | Association splitting versus cognitive remediation in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a randomized controlled trial Journal of Anxiety Disorders |

Jelinek et al.54 | N=109 patients with OCD undergoing CBT were randomly assigned to either AS or cognitive remediation. | Although patient acceptance of AS was good, AS was not better than cognitive remediation for overall symptom severity. |

| 29 | Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and residual symptoms after cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT): a randomized controlled trial European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience |

Külz et al.55 | N=125 patients with OCD and residual symptoms after CBT were randomized to either an MBCT group (n=61) or a psychoeducational group (OCD-EP; n=64) as an active control condition. | The results suggest that, compared to a psychoeducational program, MBCT leads to accelerated improvement of self-reported OC symptoms and secondary outcomes, but not of clinician-rated OC symptoms. |

| 30 | Therapist-Assisted Internet-Based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Versus Progressive Relaxation in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Randomized Controlled Trial Journal of Medical Internet Research |

Kyrios et al.56 | N=179 OCD patients were randomized to iCBT or iPRT. | The results indicate that iCBT has a large effect magnitude for OCD. Interestingly, iPRT was also moderately efficacious, albeit significantly less so than the iCBT intervention. |

| 31 | A randomized controlled trial of concentrated ERP, self-help and waiting list for obsessive-compulsive disorder: The Bergen 4-day treatment Frontiers in Psychology |

Launes et al.57 | N=48 patients with OCD were randomized to B4DT (n=16), SH (n=16), or WL (n=16). | The results indicate that B4DT is an effective treatment for patients suffering from OCD. |

| 32 | Cognitive-coping therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: A randomized controlled trial Journal of Psychiatric Research |

Ma et al.58 | N=145 OCD patients were randomly assigned to pharmacotherapy (n=72) or PCCT (n=73). | The response rates and remission rates were higher in PCCT than the pharmacotherapy group. Therefore, CCT is a potential treatment for OCD. |

| 33 | Improving treatment outcome in obsessive-compulsive disorder: Does motivational interviewing boost efficacy? Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders |

McCabe et al.59 | N=40 OCD patients were randomized to a three-session motivational interviewing intervention or a three-session relaxation intervention prior to 15 sessions of ERP. The groups were compared regarding treatment dropout, homework compliance, and treatment outcome post-ERP and at follow up. | The results show that ERP may confer a small but meaningful benefit for treatment outcome. |

| 34 | Efficacy of cognitive behavioural therapy with medication for patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder: A multicentre randomised controlled trial in China Journal of Affective Disorders |

Meng et al.60 | N=167 OCD patients were randomly allocated to receive either CBT combined with medication (n=92) or medication alone (n=75) for a 24-week treatment period. | CBT plus medication may alleviate the symptoms and social impairment associated with OCD and is more effective than medication alone in China, particularly for treating compulsive behaviors. |

| 35 | Internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a randomized controlled trial Psychological Medicine |

Andersson et al.61 | N=101 patients diagnosed with OCD were randomized to either 10 weeks of iCBT or to an attention control condition, consisting of online supportive therapy. | iCBT is an efficacious treatment for OCD that could substantially increase access to CBT for OCD patients. Replication studies are warranted. |

| 36 | Efficacy of exposure versus cognitive therapy in anxiety disorders: Systematic review and meta-analysis BioMed Central Psychiatry |

Ougrin et al.62 | PsycINFO, Medline, and Embase were searched from the first available year to May 2010. All randomized controlled studies comparing the efficacy of exposure with CT were included. Odds ratios or standardized mean differences (Hedges’ g) for the most clinically relevant primary outcomes were calculated. The study outcomes were grouped according to specific disorders and combined in meta-analyses exploring short-term and long-term outcomes. | Based on the literature, there appears to be no evidence of differential efficacy between CT and exposure in PD, PTSD and OCD, and strong evidence of superior efficacy of CT in social phobia. |

| 37 | Computer-delivered cognitive-behavioral treatments for obsessive compulsive disorder: preliminary meta-analysis of randomized and non-randomized effectiveness trials The Cognitive Behaviour Therapist |

Pozza et al.63 | A meta-analysis was conducted according to PRISMA guidelines. Treatments were classified as CCBTs if they included evidence-based cognitive-behavioral components for OCD (psychoeducation, ERP, cognitive restructuring), delivered through devices like computers, palmtops, telephone-interactive voice-response systems, CD-ROMS, or cell phones. | Findings from this meta-analysis suggest that CCBTs are a valid and promising alternative way of delivering CBT to target OCD. Given the evidence in the literature about the cost-effectiveness of such treatment modalities, CCBTs could be effectively used in the context of public mental health services as a low-intensity treatment and as a main intervention for patients diagnosed with OCD. |

| 38 | Efficacy of group psychotherapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials Journal of Obsessive Compulsive Related Disorders |

Schwartze et al.64 | Twelve studies including 16 comparisons and 832 patients. The majority of studies examined the CBT group. | The findings highlight the value of group therapy as an efficacious treatment for patients suffering from OCD. |

| 39 | Pharmacological and psychotherapeutic interventions for management of obsessive-compulsive disorder in adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis The Lancet Psychiatry |

Skapinakis et al.10 | A total of 1,480 articles were identified, of which 53 were included (54 trials; 6,652 participants) in the network meta-analysis. | A range of interventions is effective for OCD, but there is considerable uncertainty regarding their relative efficacy. Taking all the evidence into account, a combination of psychotherapeutic and psychopharmacological interventions is likely to be more effective than psychotherapeutic interventions alone, at least for severe OCD. |

| 40 | Family and couple integrated cognitive-behavioral therapy for adults with OCD: A meta-analysis Journal of Affective Disorders |

Stewart et al.65 | Fifteen studies were reviewed (16 independent samples). | Family-integrated treatment appears to be effective for adult OCD, related symptoms, and relationship factors. There is preliminary support that family-integrated treatment leads to better outcomes than individual treatment. |

| 41 | A meta-analysis on the treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder: A comparison of antidepressants, behavior, and cognitive therapy Clinical Psychology Review |

Van Balkom et al.66 | 86 studies dealing with the efficacy of treatment for OCD with antidepressants, pill-placebo, BT, CT, attention placebo, or a combination of these treatments were analyzed. | From this meta-analysis on the efficacy of treatment of OCD, it can be concluded that serotonergic antidepressants, BT, CT, and a combination of these treatments are generally associated with large effect sizes for obsessive compulsive symptoms, depression, anxiety, and social adjustment. |

| 42 | Efficacy of technology-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy for OCD versus control conditions, and in comparison with therapist-administered CBT: Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials Cognitive Behavioral Therapy |

Dèttore et al.67 | Eight RCTs were included (n=420). | The efficacy difference for OCD symptoms between T-CBT and therapist-administered CBT was not significant. |

| 43 | A multidimensional meta-analysis of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder Clinical Psychology Review |

Eddy et al.68 | We included 32 clinical trials (six of which had a cross-over design) involving 68 treatment conditions. | Both psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy produce substantial decreases in OCD symptoms, reflected in; i) pre-treatment vs. post-treatment effect sizes; ii) a substantial percentage of patients who improve with treatment; and iii) considerable declines in symptoms from pre- to post-treatment. |

| 44 | Cognitive behavioral treatments of obsessive-compulsive disorder. A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies published 1993-2014 Clinical Psychology Review |

Öst et al.69 | This meta-analysis included 37 RCTs with CBT for OCD using the Y-BOCS. | CBT was significantly better than antidepressant medication, but CBT plus medication was not significantly better than CBT plus placebo. |

ACT = acceptance and commitment therapy; AS = association slitting; B4DT = Bergen 4-day treatment; bCBT = bibliotherapy-administered cognitive behavioral therapy; BT = behavior therapy; CBGT = cognitive-behavioral group therapy; CBT = cognitive behavioral therapy; CCT = cognitive-coping therapy; CR = cognitive restructuring; CT = cognitive therapy; DCS = d-cycloserine; DIRT = danger ideation reduction therapy; DIRT‐C = DIRT for obsessive‐compulsive checkers; DM = detached mindfulness; EMDR = eye movement desensitization and reprocessing; ERP = exposure and response prevention; EX/RP = exposure and response prevention IBA = inference-based approach; iCBT = Internet-based CBT; iPRT = Internet-based progressive relaxation therapy; MBCT = mindfulness-based cognitive therapy; OC = obsessive-compulsive; OCD = obsessive-compulsive disorder; OCD-EP = OCD psychoeducational treatment group; PCBT = pharmacotherapy plus CBT; PCCT = pharmacotherapy plus CCT; PRISMA = Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; RCTs = randomized controlled trials; SH = self-help; SRIs = serotonin reuptake inhibitors; SSRIs = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; T-CBT = technology-delivered CBT; tDCS = transcranial direct current stimulation; WL = waiting list; Y-BOCS = Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale.

1. Is cognitive-behavioral therapy superior to control interventions for reducing symptom severity in adult patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder?

CBT including ERP, with or without cognitive techniques, is the only recommended psychological treatment for OCD. All 13 articles reporting CBT use included RCTs in which patients who received standard CBT had lower Y-BOCS scores post-treatment than pre-treatment compared to control conditions, all of which were psychotherapeutic interventions (35% to 93.8% of responders had significantly improved obsessive compulsive symptoms according to Y-BOCS scores). In these 13 studies, CBT was compared to the following control interventions: supportive therapy58 (PEDro score = 9); self-help57 (CBT Cohen’s d = 3.75; self-help Cohen’s d = 0.77, and waiting list Cohen’s d = -0.11) (PEDro score = 9); eye movement desensitization and reprocessing30 (η2 = 0.296) (PEDro score = 6); acceptance and commitment therapy36 (ERP: Cohen’s d = 2.498, and acceptance and commitment therapy + ERP (Cohen’s d = 0.113) (PEDro score = 10); danger ideation reduction therapy37 (danger ideation reduction therapy pre- and post-treatment comparison: Cohen’s d = 1.811; ERP pre and post-treatment comparison: Cohen’s d = 4.801) (PEDro score = 8); and an inference-based approach40 (Cohen’s d = 0.3) (PEDro score = 9). Two of these studies tested mindfulness (Kulz et al.55: η2p = 0.053; p = 0.036; Rupp et al.29: Cohen’s d = 0.53) (PEDro score = 9; 11) and another tested “association splitting” vs. cognitive remediation54 (η2p = 0.024) (PEDro score = 8) as add-on therapies, although none of the results supported the effectiveness of these treatment options; all tested interventions differed from CBT without significant effect sizes.

Two of these 13 studies46,57 (both with a PEDro score of 9) compared the efficacy of CT vs. ERP for adults with OCD, reporting no significant differences in Y-BOCS score reduction. In the first study,69 65 patients were divided into CT and intensive BT groups. Patients allocated to the CT group received 20 hours of individual therapy divided into 16 weekly sessions, while the BT group received intensive treatment with two 2-hour sessions during the first 4 weeks, followed by an additional 12 weeks of maintenance sessions (totaling 16 weeks). In both groups, OC symptoms significantly reduced (≥ 25% Y-BOCS reduction from baseline). However, the reduction in Y-BOCS scores did not differ significantly between groups and there was no significant within-group effect size (Cohen's d = 0.05). A similar study57 compared a particular form of BT that includes ERP (Bergen 4-day treatment [B4DT]) vs. a self-help intervention vs. a waiting list control group. Patients in the B4DT group received intensive daily ERP-focused treatment for four consecutive days. Mean Y-BOCS scores were reduced in both the B4DT and self-help groups compared to wait-list controls; the B4DT group had significantly lower final Y-BOCS scores (effect size d = 3.75) than the self-help (Cohen’s d = 0.77) and waiting list (Cohen’s d = -0.11) groups, while the mean Y-BOCS scores of self-help group did not differ significantly from the wait-list group.

We found two meta-analyses evaluating CBT as a psychotherapeutic treatment for adult OCD patients: Öst et al.69 (AMSTAR = high quality) and Ougrin et al.39 (AMSTAR = moderate quality). Öst et al.69 reported no differences in the magnitude of effect sizes for CT (Hedge’s g: 1.84, SE: 0.46, 95%CI 0.94-2.74, p < 0.001) or CBT (Hedge’s g: 1.35, SE: 0.20, 95%CI 0.96-1.74, p < 0.001). In four studies, Ougrin et al.62 found no significant differences regarding the relative efficacy of CT and ERP for improving OCD severity (test for overall effect z = 0.01; p = 1.00). Since the CT and CBT protocols all have the ERP element in common, CBT based on ERP is highly recommended for adults with OCD (Hedge’s g = 1.39).

Taken together, CBT delivered either weekly or at an intensive frequency remains the only psychotherapeutic treatment recommended for adults with OCD (class of recommendation [COR] = 1, level of evidence [LOE] A).

2. What techniques and interventions (number of sessions, individual or group sessions) are used for cognitive-behavioral therapy in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder?

We carefully evaluated 13 RCTs and two meta-analyses that addressed this question. Group or individual CBT therapy was proven to be as or more effective than other psychological treatments, such as mindfulness,29 acceptance and commitment therapy,36 or EMDR.30 The number of weekly sessions ranged from 12 to 16, lasting from 60 to 120 minutes each, except intensive treatment (24), in which 4 to 8 hours of treatment were provided on 4 consecutive days.

CBT can be delivered in groups or individually, with sessions lasting from 60 to 120 minutes, in weekly or intensive programs (COR = 1, LOE = A). Schwartze et al.64 (AMSTAR = low quality) suggested that group psychotherapy is far more effective in improving OC symptoms than a wait-list control group (Hedge’s g = 0.97, 95%CI 0.58; 1.37, p < 0.001, k = 4). Compared to active controls (individual psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy), no significant differences were found (Hedge’s g = -0.02, 95%CI -0.27 to 0.23; p = 0.0874; k = 9; Q = 14.91, df = 8; p = 0.061; I2 = 46.3%).

In a meta-analysis of 15 studies (16 independent samples), Stewart et al.65 (AMSTAR = low quality) concluded that integrating family treatment with CBT protocols reduced OCD severity (good effect size: Hedge’s g = 1.39). The authors also suggested that this combination may help reduce the severity of depressive symptoms and functional impairment, in addition to improving satisfaction with personal relationships and the mental health of family members (COR = 2b, LOE = C-LD).

Taken together, both individual and group CBT sessions based on ERP are effective treatment choices for adults with OCD (COR = 1, LOE = A). Family interventions are also recommended (COR = 2b, LOE = C-LD). Treatment can be delivered in weekly or intensive regimens, with 12 to 16 sessions (weekly) lasting an average of 60 minutes (COR = 1, LOE = A).

3. Is there a difference in efficacy between treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and cognitive-behavioral therapy?

The meta-analysis of Öst et al.69 (AMSTAR = high quality) included 37 RCTs of CBT for OCD published between 1993 and 2014. Their findings corroborated the aforementioned argument, finding large effect sizes in comparisons of CBT and waiting list/placebo groups. Comparisons between individual and group treatment (Cohen’s d = 0.17), as well as between EPR and CT (Cohen’s d = 0.07) were small and did not differ significantly. Moreover, for patients who did not respond to ERP as a first-step treatment, fluvoxamine produced better results than treatment with CT alone. Groups treated with therapeutic protocols consisting of behavioral and cognitive interventions tended to benefit more than those treated with sertraline monotherapy (COR = 1, LOE = A).

We reviewed two studies that found no differences between CBT and pharmacotherapy. Van Balkom et al.38 (PEDro score = 7) randomized 117 participants into five experimental conditions: i) CT; ii) ERP; iii) fluvoxamine + CT; iv) fluvoxamine + EPR; and v) wait-list controls. Thirty-one participants dropped out. There were no significant differences in important characteristics of the completer sample across the five conditions. In contrast with the wait-list group, symptom severity significantly decreased in all four treatment groups after 8 weeks. After 16 weeks, all four treatments had effectively reduced OCD symptom severity, although efficacy did not differ among treatments. There was a significant time effect and no significant group x time interaction or group effect among the four treatment conditions. Taken together, these results indicate that all four intervention models were successful, and there were no relevant differences in effectiveness between them. This study did not compare short and long-term responses between groups.

Fineberg et al.49 (PEDro score = 11) randomized 49 participants into three conditions: i) CBT; ii) SSRI; iii) CBT+SSRI. The mean total Y-BOCS score at baseline was 26.7 (SD 7.5), indicating moderately severe OCD. Patients in the SSRI and CBT + SSRI groups received sertraline (dose range: 50-200 mg/day) for 52 weeks. Participants in the CBT and CBT + SSRI groups received 16 hours of psychotherapy over 8 weeks followed by four follow-up sessions. At weeks 8 and 16, there was a greater reduction in Y-BOCS scores among sertraline group than the CBT-only group. At week 16 (the primary end-point), more significant improvement had occurred in the combined treatment group than the CBT group (Cohen’s d = 0.39, 95%CI -0.47 to 1.24), followed by the SSRI group vs. the CBT group (Cohen’s d = 0.27, 95%CI -0.73 to 1.3), although the effect sizes were small. The high attrition rate by week 52 made evaluations unfeasible at this point. The combined arm appeared to offer the most clinically effective treatment (especially compared to CBT) in the acute treatment phase.

The results of one study supported CBT over pharmacotherapy. Skapinakis et al.10 (AMSTAR = low quality) conducted a systematic review and network analysis of 54 trials with a total of 6,652 participants. The analyses, conducted in a Bayesian framework, showed that psychotherapeutic interventions (CBT, BT, and CT) were more effective than SSRI monotherapy. The mean Y-BOCS score reduction ranged from 1.88 (CBT) to 9.87 (CT) to 10.99 (BT). Despite these findings, the authors pointed out serious methodological limitations in a large majority of the trials, since the patients were taking stable doses of antidepressants.

It should be pointed out that different CBT modalities can produce different results. Taken together, the data show that studies dating from the late 1990s do not strongly support CBT over pharmacotherapy. On the other hand, more recent investigations provided some evidence that CBT is superior to SSRI monotherapy for reducing OCD severity according to Y-BOCS scores.10,28

Considering the available studies, no sound evidence indicates the superiority of one treatment over the other. The ideal first-line treatment is a combination of CBT and SSRIs. In clinical practice, the choice of treatment should consider: treatment availability, patient preferences, and the patient’s treatment history.

4. Is there a difference between cognitive-behavioral therapy monotherapy vs. cognitive-behavioral therapy plus SSRIs for adults with obsessive-compulsive disorder?

Fineberg et al.49 (PEDro score = 11) found that although SSRI monotherapy appeared to be the most cost-effective treatment, SSRI + CBT is more effective, especially in the short term (Cohen’s d = 0.39 vs. Cohen’s d = 0.27 for sertraline monotherapy). Öst et al.69 (AMSTAR = high quality) indicated that psychotherapy modalities (e.g., CBT) were significantly better than antidepressants (Cohen’s d = 0.55), but a combination of CBT and medication was not significantly better than CBT plus placebo (Cohen’s d = 0.25).

Tenneij et al.34 (PEDro score = 8) evaluated the effect of adding BT to drug treatment in OCD patients who responded to medication, finding statistically significant effects for combined treatment (mean =11.76 [SD 7.66], p ≤ 0.001) compared to drug treatment alone (mean = 17.56 [SD 8.13], p ≤ 0.001). After 27 weeks, the combination therapy group scored roughly four points lower (in Y-BOCS) than the group that received drug treatment alone. Delayed BT (applied 6 months after drug treatment) did not significantly reduce OCD symptoms. However, the remission rate of this group was similar to that of patients who received immediate combined treatment.

Other studies do not support the superiority of combined therapy to drug monotherapy. A meta-analysis of studies comparing pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy68 (AMSTAR = low quality) found that for both treatment types, moderate levels of OCD symptoms persisted even after an adequate course of treatment, and no replicable data showed that gains were maintained for either treatment type at 1 year or beyond. Most studies to date indicate that combining CBT with an SSRI is more effective than drug monotherapy.

5. Are there any effective augmentation strategies for cognitive-behavioral therapy? Is cognitive-behavioral therapy the best augmentation strategy for pharmacotherapy in obsessive-compulsive disorder?

Chasson et al.45 (PEDro score = 11) analyzed a 10-session randomized controlled trial of ERP plus d-cycloserine (DCS) vs. ERP plus placebo in a sample of 22 adults with OCD. The results indicated that DCS does not boost the effect of ERP (t[4,137] = -1.26, p = 0.21) but seems to accelerate the effects of ERP. The course of ERP was 2.3 times faster over the full 10 sessions in the ERP + DCS group than the ERP + placebo group, and nearly six times faster during the first half of ERP.

Asnaani et al.44 (PEDro score = 11) enrolled 100 adults with OCD in a trial comparing SSRI + ERP, risperidone, or pill placebo. Patients were assessed at baseline, mid-treatment, and post-treatment for OCD symptoms and quality of life, and functioning. OCD symptom severity decreased significantly over time in the ERP group compared to the risperidone group (all p ≤ 0.011), and even more so ERP vs. placebo (p ≤ 0.005). The authors concluded that improved quality of life was associated with reduced OCD symptom severity.

Dadadshi et al.47 (PEDro score = 7) randomly assigned 26 participants with OCD to two treatment groups, comparing ERP and transcranial direct current stimulation as adjunct treatments to pharmacotherapy regarding symptom severity and quality of life. No significant difference was found between ERP and transcranial direct current stimulation regarding OCD and depression symptoms during the post-test stage (p > 0.05) (COR = 1, LOE = A).

The results indicate that adjunct CBT is superior to adjunct antipsychotics and is thus preferable if SSRI treatment fails. DCS may accelerate the therapeutic effects of CBT on OCD severity. It is important to point out that further research is needed, since this is a preliminary study on the subject. Other data are inconclusive about the duration of patient improvement, corroborating the findings of a systematic review66 (AMSTAR = critically low). In the Discussion section, we include comparable data from international guidelines on combined treatment with CBT vs. monotherapy for moderate-to-severe cases.

6. What is the adherence rate to cognitive-behavioral therapy?

The CBT adherence level varied from 59% to 100% in the related studies. In CBT, “adherence level” is a complex term involving several factors: i) therapy refusal (declining treatment despite professional recommendation); ii) therapy dropout (discontinuing health care provider recommended therapy); iii) completing treatment with poor attendance (i.e. not reaching the therapist’s recommended dose of therapy); and iv) poor adherence to between-session homework.70

It is interesting to note that adherence to CBT plus medication (range: 63%-100%)11,32-35,38,39,48-53,60 was similar to adherence to CBT alone (range: 63%-100%).29,30,36,40,44,46,54,55,57,58,62 However, when CBT is conducted via the Internet (with or without a therapist), the level of adherence decreases, with dropout levels ranging from 20%-60%.31,41-43,56,61 The PEDro scores for all relevant RCTs were between 7 and 11, demonstrating high methodological quality.

7. What is the efficacy of Internet-based cognitive-behavioral therapy for patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder?

Six RCTs31,41-43,56,61 and two meta-analyses63,67 assessing the efficacy of Internet-based CBT (iCBT) for OCD treatment were identified and included in this review.

The results of one meta-analysis67 showed that iCBT was superior to control conditions for OCD symptom outcomes at post-treatment. Eight trials were included (n = 420), although two had a high risk of bias. Regarding OCD severity, there was no significant difference in efficacy between iCBT and therapist-administered CBT, despite a trend favoring therapist-administered CBT. Treatments were classified as iCBT if they included “evidence-based, active CBT ingredients for OCD” (e.g., psychoeducation, ERP, or cognitive restructuring) and were delivered through health technologies or remote communication technologies (e.g., the Internet, webcams, telephones, interactive voice response systems, or CD-ROMS). Control groups included either wait-list or active controls. This was a high quality meta-analysis according to AMSTAR 2 criteria. In a previous meta-analysis, Pozza et al.63 found a large effect size in favor of computer-delivered CBT vs. control conditions in improving OCD severity (d = 0.98, SE = 0.14, 99%CI 0.71-1.25, p = 0.001; AMSTAR = high quality) (COR = 1, LOE = A). Although iCBT is a great low-cost alternative, the adherence rate is lower than face-to-face CBT.

In a controlled trial, Wootton et al.41 randomized patients to determine the benefits and acceptability of two remote treatment options for OCD (bibliotherapy-administered CBT and iCBT) compared to a waitlist control group. Participants in the bibliotherapy-administered CBT and iCBT groups read five lessons and received twice-weekly contact from a remote therapist. The control group received no clinical contact during this time. In both remote treatment groups, Y-BOCS scores reduced between pre- and post-treatment and between pre-treatment and the third month of follow-up. Effect sizes for Y-BOCS scores remained large between pre-treatment and follow-up, indicating that remote CBT was superior to no intervention.

Andersson et al.61 randomized 101 participants with OCD to an iCBT group (n = 50) or a control group (n = 51). In the iCBT program, therapists provided feedback on homework assignments, granted consecutive access to the modules and helped participants with ERP. Controls received non-directive supportive therapy online, which consisted of an e-mail-integrated treatment platform through which participants could communicate with a therapist. Both treatments lead to significant improvements in OCD symptoms, but were larger in the iCBT group than the control group according to Y-BOCS scores, with a significant between-group effect size (Cohen’s d) of 1.12 (95%CI 0.69-1.53) at post-treatment. Clinically significant improvement occurred in 60% of the iCBT group (95%CI 46-72) compared to 6% (95%CI 1-17) of controls. The results were sustained in follow-up. In a continuation of this study, Andersson et al.43 randomized 93 OCD patients to either a booster program (consisting of a self-help text with worksheets and an integrated e-mail system on a secured online platform) or no booster program. The patients were assessed at 4, 7, 12, and 24 months after iCBT. OCD symptoms were significantly lower in the booster group at 4 and 7 months after booster baseline, but not at 12 or 24 months. These results suggest that iCBT has long-term effects on OCD and that adding an Internet-based booster program to regular CBT can further improve long-term outcomes and prevent relapse for some patients, with large within-group effect sizes (Cohen’s d = 1.58-2.09) (PEDro score = 9).

Schröder et al.31 evaluated 128 individuals with self-reported OCD symptoms, who were randomly allocated to either an intervention group (unguided iCBT) or a control group. The eight-module intervention consisted of text, video, audio, photos, and illustrations (mean completion time = 45 minutes), focusing on established cognitive-behavioral methods of OCD treatment. Y-BOCS scores were significantly lower in the intervention group than controls, with a medium effect size (η2p = 0.06) after treatment (PEDro scale = 8).

In another study,42 190 participants were randomized to self-guided iCBT or a wait-list control group. The treatment protocol consisted of a five-lesson intervention delivered over 8 weeks. Statistically significant time, group, and group x time interaction effects were found for the primary outcome measure, Y-BOCS self-report version scores, indicating that though both groups had significant changes from baseline, the rate of change was significantly higher in the treatment group. There was a significant post-treatment difference between groups (29% reduction over the wait-list estimate; d = 0.58), with the iCBT group showing significantly lower Y-BOCS self-report version scores (mean = 15.42) than controls (mean = 21.61). There was a significant reduction in Y-BOCS self-report version scores between pre- and post-treatment (32% reduction in symptoms; d = 1.25) and between pre-treatment and 3 months of follow-up in the iCBT group (35% symptom reduction; d = 1.23). In addition, 27% of the iCBT group fulfilled conservative criteria for clinically significant change at post-treatment, which increased to 38% at 3 months of follow-up. Participants rated the program as highly acceptable. The between-group effect size at post-treatment was large for Y-BOCS self-report version scores (d = 1.05; 95%CI 0.89-1.21), indicating that iCBT was highly superior to the control condition (PEDro scale = 7).

Finally, one study56 evaluated the difference between therapist-assisted iCBT vs. therapist-assisted Internet relaxation training in 179 participants. The former included psychoeducation, mood and behavioral management, ERP, CT, and Internet-based progressive relaxation therapy, while the latter included psychoeducation and relaxation techniques to manage OCD-related anxiety but did not incorporate ERP or other elements of CBT. Both treatment types consisted of 12 modules delivered online over a 12-week period. iCBT was superior, producing reliable improvement and clinically significant pre- and post-treatment changes. Relative to Internet-based progressive relaxation therapy, iCBT showed significantly greater improvement in symptom severity (p = 0.001), with a Cohen’s d of 1.05 (95%CI 0.72-1.37). The Cohen’s d of Internet-based progressive relaxation therapy was 0.48 (95%CI 0.22-0.73), indicating that iCBT was superior. Study assessment with the PEDro scale indicated moderate-to-high methodological quality.

Taken together, RCTs evaluating the efficacy of iCBT showed positive results in reducing OCD symptoms, and it is recommended as an alternative to face-to-face CBT. The COR and LOE for psychotherapy in adult OCD patients are summarized in Box 2.

Box 2. Psychotherapy treatments for OCD - recommendation classes and levels of evidence.

| Psychotherapy treatments for OCD | COR | LOE | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive-behavioral therapy | 1 | A | Efficacy well established in multiple RCTs and meta-analyses |

| Internet-delivered CBT | 1 | A | Efficacy well established in multiple RCTs and meta-analyses |

| Cognitive-behavioral therapy + SSRIs | 1 | A | Efficacy well established in multiple RCTs and meta-analyses |

| Family-integrated CBT | 2b | Level C-LD | Evidence derived from one meta-analysis with low overall quality. Can be used. |

CBT = cognitive-behavioral therapy; COR = class (strength) of recommendation; LOE = level (quality) of evidence; OCD = obsessive-compulsive disorder; RCT = randomized clinical trial; SSRIs = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

Discussion

The main objective of this study was to produce an updated clinical guideline for CBT treatment in adult OCD patients. To accomplish this, we began by reviewing the 2013 American Psychiatric Association guidelines.21 A systematic review was performed by a workgroup of three cognitive-behavioral therapists experienced in OCD treatment. We searched for relevant studies published between 2013 and 2020 in five relevant medical literature databases (PubMed, Cochrane, Embase, PsycINFO and LILACS). We used two article quality assessment tools (AMSTAR and PEDro) to rigorously assess the methodological quality of the articles selected to answer the research questions.

SSRI/clomipramine and CBT with ERP are both recognized treatments for OCD.9 According to the most updated clinical guidelines on pharmacological treatment for adults with OCD19 the first-line treatment for OCD is SSRIs given at the highest recommended or tolerable dose for 8-12 weeks. Considering both psychological and pharmacological interventions, the best augmentation strategy for SSRI-resistant OCD is CBT, while the best pharmacological strategy is low doses of risperidone or aripiprazole.19 A summary of the results of our systematic review are discussed below, as are our recommendations.

Our main finding corroborates the current literature, i.e., that ERP-based CBT, with or without cognitive elements, is the recommended psychological treatment for OCD (COR = 1, LOE = A). Regarding therapy format, individual or group sessions are both effective for adults with OCD. The recommended number of weekly CBT sessions ranges from 12 to 16, with each session lasting an average of 60 minutes. The data diverge regarding the efficacy of CBT compared to SSRIs. The most recent studies conclude that CBT is superior to or as effective as SSRIs (COR = 1, LOE = A). Most studies indicate that a combination of CBT and SSRIs is more effective than monotherapy.

Despite CBT’s established efficacy, adherence levels vary from 59 to 100%, which is a potential limitation. It is important to note that treatment non-adherence is a global challenge in psychiatry71 and is not specific to OCD. Treatment non-adherence leads to serious consequences for individuals suffering from mental health disorders, including relapse, rehospitalization, and suicidal behavior. Santana et al.72 found that 46% of patients with OCD refused CBT, 52% refused to take any medication, and 61% took their medications less frequently or at a lower dose than prescribed. Stigma and medication adherence in OCD has not been as extensively studied as in schizophrenia or bipolar affective disorder, for example. Ansari et al.73 found that high levels of internalized stigma were associated with lower treatment adherence in patients with OCD. The lack of treatment adherence among patients with OCD may be related to the fact that they require relatively high doses of medications for a long time, which is costly. In this context, iCBT may be an effective countermeasure. Recently, iCBT has been used for OCD in many countries, showing positive results (COR =1, LOE =A). The greatest advantage of iCBT over conventional treatments is its reach, allowing patients who cannot obtain face-to-face CBT to receive effective treatment. In addition, therapist-assisted iCBT requires one-quarter of the time of face-to-face therapy (about 15 minutes per patient each week), thus reducing the cost of first-line OCD treatment.

Another important strategy in OCD treatment is including a family member in the CBT protocol. Our search found one meta-analysis on this topic.65 Professionals who regularly deal with this disorder know the importance of psychoeducation in OCD treatment. Having a family member collaborate in treatment can help reduce OC symptoms, not only among adults, but in children and adolescents as well. The meta-analysis reinforced this hypothesis, suggesting that integrating family treatment into CBT protocols improves outcomes.

Our data are comparable to important guidelines on OCD treatment: the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence guidance74 offers evidence-based treatment for professionals, patients, and their caregivers to help with decision making about treatment and health care. In adults with OCD, the initial treatment is based on symptom severity and impairment. Low intensity psychological treatments, such as ERP (up to 10 therapist hours per patient), should be offered if the patient’s functional impairment is mild and/or the patient expresses a preference for a low-intensity approach. Adult OCD patients with mild functional impairment who cannot engage in low-intensity CBT (including ERP) should be offered the choice of SSRIs or more intensive CBT (including ERP) (> 10 therapist hours per patient), since these treatments appear to be comparably efficacious. Patients with moderate functional impairment should be offered the choice of SSRIs or more intensive CBT (including ERP) (> 10 therapist hours per patient), because these treatments appear to be comparably efficacious. Patients with severe functional impairment should be offered combined treatment with an SSRI and CBT (including ERP).

Another important guideline75 recommends SSRIs and CBT as the leading evidence-based options for adults with OCD. CBT alone is recommended for mild to moderately ill patients. For more severe cases, a combination of SSRIs and CBT should provide better results. In partial and non-responders to SSRIs, additional CBT is recommended as the first option.

These guidelines involve certain limitations. First, only treatment studies reporting OCD severity according to Y-BOCS scores were included, which reduced the number of eligible studies. Nevertheless, considering that the Y-BOCS is the main scale used to assess OCD severity in treatment studies, we believe that this criterion added consistency to our findings. Second, since our search was based on CBT, the most evidence-based therapy for OCD, other treatment modalities were not included in this review. New systematic reviews of other psychotherapeutic methods are welcome in the literature. Third, most studies included patients who were also taking psychotropic medications, so our conclusions regarding CBT cannot be generalized to the unmedicated population. Fourth, we limited the search to English-language articles only, reducing the number of potential studies. Fifth, some review articles used standardized mean differences to compare treatment interventions, which could have introduced bias in the meta-analyses. The limited reporting of between-group effect sizes in the selected articles should be taken into consideration. Finally, the fact that patients and controls were not blinded to the experimental conditions is inherent to the psychotherapeutic method. However, despite these limitations, we believe we have rigorously summarized the best CBT recommendations for adults with OCD.

The included studies support the use of CBT as a first-line treatment to reduce OCD severity and allow us to recommend that an adequate CBT protocol should include: CBT with ERP, 12 to 16 weekly sessions, and an average session length of 60 minutes. Cognitive techniques can be included or not. This recommendation is supported by high-quality scientific evidence (COR =1, LOE = A). iCBT represents a new opportunity to disseminate the first-line treatment for OCD to a wider range of patients due to its low cost, greater accessibility, and ease of implementation.

Disclosure

EFQV has received honoraria from Aché Laboratórios Farmacêuticos in the past 36 months. DLCC has received honoraria from Janssen, Lundbeck, and Schwabe Pharmaceuticals in the past 36 months. The other authors report no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Instituto Nacional de Psiquiatria do Desenvolvimento para Crianças e Adolescentes, the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP; grants: 2014/50917-0), and the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq; grants: 465550/2014-2).

Footnotes

How to cite this article: Mathis M, Chacon P, Boavista R, de Oliveira MVS, de Barros PMF, Echevarria MAN, et al. Brazilian Research Consortium on Obsessive-Compulsive Spectrum Disorders guidelines for the treatment of adult obsessive-compulsive disorder. Part II: cognitive-behavioral therapy. Braz J Psychiatry. 2023;45:431‐447. http://doi.org/10.47626/1516-4446-2023-3081

References

- 1.Torres AR, Prince MJ, Bebbington PE, Bhugra D, Brugha TS, Farrell M, et al. Obsessive-compulsive disorder: prevalence, comorbidity, impact, and help-seeking in the British National Psychiatric Morbidity Survey of 2000. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1978. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.11.1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruscio AM, Stein DJ, Chiu WT, Kessler RC. The epidemiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15:53–63. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J, Baxter AJ, Ferrari AJ, Erskine HE, et al. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet Lond Engl. 2013;382((9904)):1575–86. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61611-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andrade L, Walters EE, Gentil V, Laurenti R. Prevalence of ICD-10 mental disorders in a catchment area in the city of São Paulo, Brazil. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2002;37:316–25. doi: 10.1007/s00127-002-0551-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rasmussen SA, Eisen JL. The epidemiology and differential diagnosis of obsessive compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1992;53(Suppl:4-10) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eisen JL, Pinto A, Mancebo MC, Dyck IR, Orlando ME, Rasmussen SA. A 2-year prospective follow-up study of the course of obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(8):1033–9. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04806blu. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramos AL, Salgado H. Refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: a challenging treatment. Eur Psychiatry. 2022;65:S295. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fineberg NA, Hollander E, Pallanti S, Walitza S, Grünblatt E, Dell’Osso BM, et al. Clinical advances in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a position statement by the International College of Obsessive-Compulsive Spectrum Disorders. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2020;35:173–93. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0000000000000314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stein DJ, Costa DLC, Lochner C, Miguel EC, Reddy YCJ, Shavitt RG, et al. Obsessive-compulsive disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primer. 2019;5:52. doi: 10.1038/s41572-019-0102-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Skapinakis P, Caldwell DM, Hollingworth W, Bryden P, Fineberg NA, Salkovskis P, et al. Pharmacological and psychotherapeutic interventions for management of obsessive-compulsive disorder in adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3:730–9. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30069-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Belotto-Silva C, Diniz JB, Malavazzi DM, Valério C, Fossaluza V, Borcato S, et al. Group cognitive-behavioral therapy versus selective serotonin reuptake for obsessive-compulsive disorder: A practical clinical trial. J Anxiety Disord. 2012;26:25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Albert U, Marazziti D, Di Salvo G, Solia F, Rosso G, Maina G. A systematic review of evidence-based treatment strategies for obsessive-compulsive disorder resistant to first-line pharmacotherapy. Curr Med Chem. 2018;25:5647–5661. doi: 10.2174/0929867325666171222163645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McKay D, Sookman D, Neziroglu F, Wilhelm S, Stein DJ, Kyrios M, et al. Efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2015;225:236–46. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.11.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meyer V. Modification of expectations in cases with obsessional rituals. Behav Res Ther. 1966;4:273–80. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(66)90023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hezel DM, Simpson HB. Exposure and response prevention for obsessive-compulsive disorder: A review and new directions. Indian J Psychiatry. 2019;61:S85. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_516_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Craske MG, Kircanski K, Zelikowsky M, Mystkowski J, Chowdhury N, Baker A. Optimizing inhibitory learning during exposure therapy. Behav Res Ther. 2008;46:5–27. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Associação Brasileira de Psiquiatria Transtorno obsessivo compulsivo: tratamento. 2011. https://amb.org.br/files/ans/transtorno_obsessivo_compulsivo-tratamento.pdf

- 18.Abramowitz JS. Variants of exposure and response prevention in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder: a meta-analysis. Behav Ther. 1996;27:583–600. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oliveira M, Barros P, Mathis M, Boavista R, Chacon P, Echevarria MAN, et al. Brazilian Psychiatric Association guidelines for the treatment of adult obsessive-compulsive disorder. Part I: Pharmacological treatment. Braz J Psychiatry. 2023;45:146–61. doi: 10.47626/1516-4446-2022-2891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koran LM, Hanna GL, Hollander E, Nestadt G, Simpson HB. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:5–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koran LM, Simpson HB. Guideline watch (2013): Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. 2013. https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/ocd-watch-1410457187510.pdf [PubMed]

- 22.Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, Mazure C, Fleischmann RL, Hill CL, et al. The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. I. Development, use, and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46:1006–11. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810110048007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5:210. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cashin AG, McAuley JH. Clinimetrics: Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) Scale. J Physiother. 2020;66:59. doi: 10.1016/j.jphys.2019.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358:j4008. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jacobs AK, Kushner FG, Ettinger SM, Guyton RA, Anderson JL, Ohman EM, et al. ACCF/AHA clinical practice guideline methodology summit report: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013;127:268–310. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31827e8e5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rector NA, Richter MA, Katz D, Leybman M. Does the addition of cognitive therapy to exposure and response prevention for obsessive compulsive disorder enhance clinical efficacy? A randomized controlled trial in a community setting. Br J Clin Psychol. 2019;58:1–18. doi: 10.1111/bjc.12188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rupp C, Jürgens C, Doebler P, Andor F, Buhlmann U. A randomized waitlist-controlled trial comparing detached mindfulness and cognitive restructuring in obsessive-compulsive disorder. PloS One. 2019;14:e0213895. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0213895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sarichloo ME, Taremian F, Dolatshahee B, Javadi SAHS. Effectiveness of exposure/response prevention plus eye movement desensitization and reprocessing in reducing anxiety and obsessive-compulsive symptoms associated with stressful life experiences: a randomized controlled trial. Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci. 2020;14:e101535. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schröder J, Werkle N, Cludius B, Jelinek L, Moritz S, Westermann S. Unguided Internet-based cognitive-behavioral therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Depress Anxiety. 2020;37:1208–20. doi: 10.1002/da.23105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simpson HB, Foa EB, Liebowitz MR, Huppert JD, Cahill S, Maher MJ, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy vs risperidone for augmenting serotonin reuptake inhibitors in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:1190–9. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sousa MB, Isolan LR, Oliveira RR, Manfro GG, Cordioli AV. A randomized clinical trial of cognitive-behavioral group therapy and sertraline in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67((7)):1133–9. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tenneij NH, van Megen HJGM, Denys DAJP, Westenberg HGM. Behavior therapy augments response of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder responding to drug treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:1169–75. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tolin DF, Hannan S, Maltby N, Diefenbach GJ, Worhunsky P, Brady RE. A randomized controlled trial of self-directed versus therapist-directed cognitive-behavioral therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder patients with prior medication trials. Behav Ther. 2007;38:179–91. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]