Abstract

Purpose

The discontinuation of fertility treatment could decrease the chances of achieving parenthood for infertile patients and often leads to economic loss and medical resource waste. However, the evidence on the factors associated with discontinuation is unclear and inconsistent in the context of fertility treatment. This scoping review aimed to summarize the evidence on factors associated with discontinuation in fertility treatment, identify the current knowledge gap, and generate recommendations for future research.

Methods

We searched PubMed, Embase, The Cochrane Library, Web of Science, CINAHL, American Psychological Association, and http://clinicaltrials.gov from inception to June 2023 without language or time restrictions. We also searched the grey literature in Open Grey and Google Scholar and hand-searched the reference lists of relevant studies to identify potentially eligible studies. Publications that studied factors associated with discontinuation in fertility treatment were included. The identified factors were mapped to the World Health Organization’s treatment adherence model.

Results

Thirty-seven articles involving 41,973 infertile patients from 13 countries were included in this scoping review. All studies identified the factors from the perspective of patients, except for one that described the factors from the healthcare providers’ perspective. A total of 42 factors were identified, with most of them belonging to the patient-related dimension, followed by socio-economic-related, treatment-related, condition-related, and healthcare system-related dimensions. Female education level, social support, and insurance coverage decreased the likelihood of treatment discontinuation, whereas multiparous women, male infertility, depression, higher infertility duration, and treatment duration increased the likelihood of treatment discontinuation. Age, education level, and ethnicity are the commonly nonmodifiable factors for treatment discontinuation, while insurance coverage, depression, and anxiety symptoms are among some of the more commonly reported modifiable factors.

Conclusion

This is the first scoping review examining and synthesizing evidence on the factors influencing of discontinuation in fertility treatment. This review could inform researchers, clinicians, and policymakers to address modifiable barriers and facilitators to develop personalized and multicomponent interventions that could improve the discontinuation in fertility treatment.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10815-023-02982-x.

Keywords: Assisted reproductive technology, Discontinuation, Fertility treatment, Infertility, Scoping review

Introduction

Infertility is a global health issue affecting 48 million couples and 186 million individuals of reproductive age worldwide [1]. The need for and utilization of fertility treatments is increasing [2]. It is reported that 56.1% (range 42–76.3%) of infertile couples in developed countries and 51.2% (range 27–74.1%) of couples in developing countries seek fertility treatments [3]. Fortunately, the chances of achieving parenthood are high for couples undergoing fertility treatment. A recent cohort study involving 14,311 women reported the cumulative live birth rate with assisted reproductive technologies (ART) was 40.54% in the first complete cycle and can be higher in the subsequent cycles [4].

Despite the well-documented benefits of fertility treatments for infertile patients, many choose to discontinue treatment before achieving a live birth, with a reported prevalence of 54.29% on average [5]. A systematic review and meta-analysis identify that early discontinuation of fertility treatment is associated with 15% lower pregnancy or live birth rates [6]. Moreover, patients who discontinued treatment may lead to economic losses since the direct cost of ART treatment is ranged from $2109 to $18,592 per one fresh cycle in different countries [7]. In addition, treatment discontinuation could lead to considerable public health consequences including psychological distress, social stigmatization, and marital discord, particularly in settings where childbearing is highly valued and central to ideas of womanhood [8].

Given the potential adverse outcomes, a number of studies have attempted to examine the factors associated with discontinuation in fertility treatment. However, limited systematic reviews were conducted in this area and those mainly focused on the assessment of whether the factors are effective in relation to treatment discontinuation rather than mapping out the extent of factors in a much broader focus [5, 9]. Moreover, existing reviews examining factors for discontinuation in fertility treatment have been limited by design (e.g., only included quantitative studies) and scope (e.g., only examining patient factors) [5, 9]. A scoping review involves the synthesis and analysis of a range of study designs aiming at providing a broad overview or map of the available evidence on the topic, which could be used to bridge the current research gap [10–12]. Therefore, we performed the scoping review to systematically summarize all published literature examining factors associated with discontinuation in fertility treatment, and it also aims to identify knowledge gaps in the current literature to help inform future research and practice.

Methods

Study design

This scoping review was performed according to Arksey and O’Malley’s five-stage framework (see Supplementary Table SI) [10] and was reported following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analysis extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist [13]. This review was registered on Open Science Framework on 20 March 2023, with the registration doi of 10.17605/OSF.IO/295M8.

A scoping review methodology design was selected in this study for three reasons. First, a scoping review is helpful when characterizing a topic that has not yet been comprehensively studied. Second, a scoping review is appropriate for describing diverse and complex data from a range of study designs [12]. Third, a scoping review is helpful to study what is known and points at which there are gaps in the topic, so as to identify the future directions for research [14].

Stage 1: defining the research question

In the current scoping review, the research question was as follows: what are the factors associated with fertility treatment discontinuation among infertility patients? With respect to the research question, two particular concepts needed some further explanation: “fertility treatment” and “treatment discontinuation.”

In this review, fertility treatment included three main types: medicines, surgical procedures, and ART treatment [15]. The ART treatment was defined as “all treatments or procedures that include the in vitro handling of both human oocytes and sperm or of embryos for the purpose of establishing a pregnancy” according to the International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technology (ICMART) and the World Health Organization (WHO) revised glossary of ART terminology [16]. The definition of treatment discontinuation was not limited since the definitions are varied greatly in the fertility treatment context.

Stage 2: identifying relevant studies

We systematically searched the literature in the seven electronic databases and registers (PubMed, Embase, The Cochrane Library, Web of Science (WOS), CINAHL, American Psychological Association (APA), and clinicaltrials.gov (http://clinicaltrials.gov)) from inception to 21 February 2023. Additionally, we consulted Open Grey and Google Scholar to identify the grey literature (e.g., research reports, thesis and dissertation). We also hand-searched the reference lists of relevant studies, including previous reviews and included studies, to help us pick up potentially eligible studies that were missed by the above search methods.

The search strategy, including two search groups, was developed by two reviewers and further reviewed by an experienced research librarian. One is for fertility treatment (e.g., assisted reproductive treatment) and another for discontinuation (e.g., dropout). Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS) was used in developing the search strategy as its use was found to be beneficial in reducing errors and improving search strategies [17]. The search strategy in the seven databases and registers is presented in Supplementary Table SII. Additionally, the search strategy saved in the platform of these databases and registers was rerun before the final analysis (June 12, 2023), and no eligible study was found. No time and language restrictions were applied in the search stage.

Stage 3: selecting studies

We performed the study selection based on a three-step screening process: literature import, preliminary review, and full-text review. All selected articles were imported into EndNote (version X20, 2020). Subsequently, two reviewers preliminarily filtered the selected articles by reviewing titles and abstracts after identifying duplication. Finally, full texts were retrieved and reviewed following the pre-defined eligibility criteria.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (i) the study population had to consist of patients with diagnosed infertility, (ii) the study population had received fertility treatment, (iii) the study outcome focused on the factors associated with treatment discontinuation, and (iv) the study had to be written in English. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (i) women who intend to but do not really discontinue treatment and (ii) secondary studies, preprint, and conference abstracts where we failed to access the full text despite contacting the authors. The overall kappa on selection between the two reviewers was 0.88, where a kappa of greater than 0.8 is considered to represent a high level of agreement [18]. Any disagreements in selection were resolved through consulting with a third researcher.

Stage 4: charting the data

A standardized data charting sheet in Microsoft Excel was developed to extract the following information from the included studies: first author’s name, year of publication, study location, study design, participants characteristics, treatment characteristics, outcome measurements, potential associated factors, and statistical methods used to examine factors. In the quantitative studies, the potential factors were defined a prior which used formal analysis (e.g., t-test, chi-square test, logistic regression) by referring to other reviews (whether significant or not) [19, 20]. However, only the factor with a significant difference was identified as influencing factors of treatment discontinuation. For qualitative studies, we extracted the themes which were reported by the authors of the studies as influencing factors (e.g., barriers, enablers). The data charting sheet was piloted in five studies before charting the data to keep consistency and accuracy. Two reviewers independently extracted the data from each study included in this review, and any disagreements in extraction were discussed until we reached consensus.

Stage 5: collating, summarizing, and reporting the results

A three-stage analysis approach was adopted to synthesize the extracted evidence. First, the influencing factors were summarized and synthesized together regardless of qualitative or quantitative studies. Second, the factors were subsequently classified according to the World Health Organization Multidimensional Adherence Model (WHO-MAM) by two reviewers based on their content relatedness [21]. The disagreements between reviewers were resolved in a discussion with the third reviewer. The WHO-MAM assumes that the treatment compliance or discontinuation behavior is affected by multiple factors rather than a single factor, which included patient-related factors, treatment-related factors, condition-related factors, socio-economic-related factors, and healthcare system-related factors. The WHO-MAM was selected for this review since it provides a conceptual framework to understand treatment discontinuation behavior comprehensively and presents a succinct overview of the relevant influencing factors in multiple and holistic ways [21], and it has been widely used and validated to examine treatment compliance or discontinuation behavior in the management of wide range of diseases [22–24]. Meanwhile, the most commonly examined factors of the included studies (mentioned by more than five studies) were also elucidated in this review. Third, in order to identify recommendations for intervention development, the influencing factors were further classified as modifiable and non-modifiable factors. The effect direction of the factors (positive or negative) was summarized in the included quantitative studies, and meanwhile, the identified barriers or drivers in the included qualitative studies were also extracted.

Results

Study selection

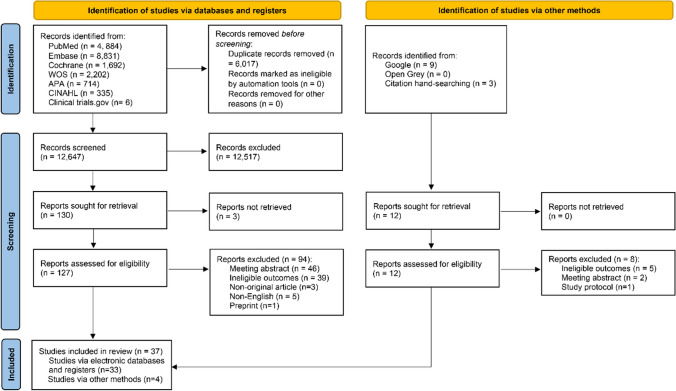

A total of 18,664 studies were identified from the electronic databases and registers, including PubMed (n = 4884), Embase (n = 8831), The Cochrane Library (n = 1692), WOS (n = 2202), APA (n = 714), CINAHL (n = 335), and clinicaltrials.gov (http://clinicaltrials.gov) (n = 6). First, we removed the 6017 duplicate studies, resulting in 12,647 studies screened by title and abstract. Second, we excluded 12,517 studies based on title and abstract screening due to unmet eligibility criteria, and 130 studies were retrieved in full text (three studies not retrieved). Third, we searched and reviewed 127 full-text studies, and 33 studies were included as eligible. Moreover, an additional 12 studies were identified through Google Scholar and hand searching, with four studies meeting the eligibility criteria. Therefore, we finally included 37 studies (33 studies via electronic databases and registers, and four studies via other methods) for this scoping review [25–61]. A PRISMA flowchart is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Characteristics of included articles

The design, sample, and treatment characteristics of the included studies are shown in Table 1. In all, thirty-five studies were quantitative involving retrospective cohort (n = 16, 43.24%) [28, 30–33, 37, 39, 44, 46, 48, 51, 53, 55, 57, 58, 61], prospective cohort (n = 11, 29.73%) [29, 34–36, 40–42, 47, 49, 52, 54], and cross-sectional (n = 8, 21.62%) [25–27, 38, 43, 45, 56, 60] design. One study was a mixed method design (qualitative-quantitative) [50], and the remaining was qualitative design [59]. The included studies sampled 41,973 infertile patients from 13 countries. The mean sample size per study was 1134 participants with a range of 22–11,361 participants. The majority of the studies were conducted in high-income countries: ten in the Netherlands [29, 34–37, 39, 40, 48, 49, 53]; nine in the USA [25, 27, 28, 41, 42, 54, 55, 57, 61]; five in France [31, 33, 44, 46, 51]; two each in Turkey [38, 58] and New Zealand [26, 43]; one each in Belgium [30], UK [32], Denmark [47], Portugal [56], Australia [59], and Japan [60]. The remaining three studies were conducted in low- and middle- income countries, with two in Iran [45, 50] and one in Israel [52]. Samples varied among the studies. Most studies questioned solely woman (n = 17) [27–30, 32, 35, 36, 40, 41, 44, 46, 50, 54, 55, 57, 58, 61] or infertile couples (n = 17) [25, 26, 31, 33, 34, 37–39, 42, 43, 45, 48, 51–53, 56, 59]; two questioned both women and men [47, 60], and only one study involved both women and professionals [49]. The majority of studies (n = 19) included all types of infertility [29, 34, 35, 37, 39–42, 47–51, 53–57, 61], and four studies focused on male infertility solely [25, 26, 31, 33], one focused on female infertility solely [52], and one reported female and male infertility [45] (32.43% not reported). The ART treatment (IVF/ICSI) was the most commonly described in the included studies (n = 26, 70.27%) [29, 30, 32, 34–41, 43–46, 50–53, 55–61]. Twenty-eight (75.68%) studies stated that treatment was subsidized or reimbursed [28, 29, 31, 33–44, 46–49, 51–53, 55–58, 60, 61] while one (2.70%) specifically stated that it was not [45], and one (2.70%) reported high variations in funding [32] (18.92% not reported).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the included studies

| Study | Country | Design | Sample size | Participants (population, infertility type)* | Treatment (type, subsidized) | Outcome measures (failed cycles, definition) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schover et al. (1992) | USA | Cross-sectional | 52 |

Couples Male |

DI NR |

Mean 2.4 Definition #1 |

| Danesh-Meyer et al. (1993) | New Zealand | Cross-sectional | 165 |

Couples Male |

DI NR |

Mean 4.6 Definition #2 |

| Schmidt et al. (1995) | USA | Cross-sectional | 52 |

Women NR |

FT NR |

0 Definition #3 |

| Gleicher et al. (1996) | USA | Retrospective cohort | 128 |

Women NR |

ART Yes |

0 Definition #4 |

| Roest et al. (1998) | The Netherlands | Prospective cohort | 1211 |

Women ALL |

IVF Yes |

1–2 Definition #5 |

| De Vries et al. (1999) | Belgium | Retrospective cohort | 1169 |

Women NR |

IVF/ICSI NR |

1–3 Definition #6 |

| Guerif et al. (2002) | France | Retrospective cohort | 588 |

Couples Male |

DI Yes |

>1 Definition #7 |

| Sharma et al. (2002) | UK | Retrospective cohort | 2056 |

Women NR |

IVF Varied |

1–4 Definition #8 |

| Guerif et al. (2003) | France | Retrospective cohort | 222 |

Couples Male |

DI Yes |

>1 Definition #9 |

| Smeenk et al. (2004) | The Netherlands | Prospective cohort | 380 |

Couples ALL |

IVF/ICSI Yes |

1–2 Definition #8 |

| Pelinck et al. (2007) | The Netherlands | Prospective cohort | 256 |

Women ALL |

IVF Yes |

1–9 Definition #10 |

| Verberg et al. (2008) | The Netherlands | Prospective cohort | 384 |

Women NR |

IVF Yes |

1–3 Definition #11 |

| Verhagen et al. (2008) | The Netherlands | Retrospective cohort | 588 |

Couples ALL |

IVF Yes |

1–3 Definition #12 |

| Akyuz et al. (2009) | Turkey | Cross-sectional | 244 |

Couples NR |

IVF Yes |

>1 Definition #13 |

| Brandes et al. (2009) | The Netherlands | Retrospective cohort | 1391 |

Couples ALL |

IVF/ICSI Yes |

>1 Definition #1 |

| Lintsen et al. (2009) | The Netherlands | Prospective cohort | 1124 |

Women ALL |

IVF/ICSI Yes |

1 Definition #14 |

| Pearson et al. (2009) | USA | Prospective cohort | 2245 |

Women ALL |

IVF Yes |

1–2 Definition #1 |

| Eisenberg et al. (2010) | USA | Prospective cohort | 434 |

Couples ALL |

FT Yes |

0 Definition #3 |

| Mcdowell et al. (2011) | New Zealand | Cross-sectional | 525 |

Couples NR |

IVF Yes |

NR Definition #1 |

| Soullier et al. (2011) | France | Retrospective cohort | 3037 |

Women NR |

IVF Yes |

1–4 Definition #15 |

| Khalili et al. (2012) | Iran/Turkey | Cross-sectional | 553 |

Couples Female/male |

IVF/ICSI No |

Mean 1.78 (Iran) Mean 2.93 (Turkey) Definition #10 |

| Troude et al. (2012) | France | Retrospective cohort | 3002 |

Women NR |

IVF/ICSI Yes |

1–3 Definition #16 |

| Vassard et al. (2012) | Denmark | Prospective cohort | 777 |

Women/men ALL |

FT Yes |

>0 Definition #17 |

| Custers et al. (2013) | The Netherlands | Retrospective cohort | 803 |

Couples ALL |

IUI Yes |

1–6 Mean 2.8 (discontinued) Mean 4.5 (completed) Definition #18 |

| Huppelschoten et al. (2013) | The Netherlands | Prospective cohort | 534 |

Women/professionals ALL |

FT Yes |

>1 Definition #19 |

| Mosalanejad et al. (2013) | Iran | Qualitative- quantitative study | 32 |

Women ALL |

IUI/IVF/drug NR |

NR Definition #20 |

| Troude et al. (2014) | France | Retrospective cohort | 5135 |

Couples ALL |

IVF Yes |

1 Definition #8 |

| Lande et al. (2015) | Israel | Prospective cohort | 134 |

Couples Female |

IVF Yes |

Mean 6.2 Definition #21 |

| Van Dongen et al. (2015) | The Netherlands | Retrospective cohort | 667 |

Couples ALL |

IVF Yes |

0–1 Definition #22 |

| Crawford et al. (2017) | USA | Prospective cohort | 416 |

Women ALL |

FT NR |

0 Definition #23 |

| Dodge et al. (2017) | USA | Retrospective cohort | 11,361 |

Women ALL |

IVF Yes |

1–6 Definition #24 |

| Pedro et al. (2017) | Portugal | Cross-sectional | 139 |

Couples ALL |

ART Yes |

<3 Definition #25 |

| Bedrick et al. (2019) | USA | Retrospective cohort | 669 |

Women ALL |

IVF Yes |

1 Definition #26 |

| Mumusoglu et al. (2019) | Turkey | Retrospective cohort | 401 |

Women NR |

IVF Yes |

1–3 Definition #27 |

| Copp et al. (2020) | Australia | Qualitative interview | 22 |

Couples NR |

IVF NR |

≥ 3 Definition #28 |

| Hirakawa et al. (2021) | Japan | Cross-sectional | 199 |

Women/men NR |

TI/IUI/IVF Yes |

NR Definition #1 |

| Almquist et al. (2022) | USA | Retrospective cohort | 878 |

Women ALL |

IVF Yes |

1 Definition #29 |

IVF in vitro fertilization; IUI intrauterine insemination; ART assisted reproductive treatments; ICSI intracytoplasmic sperm injection; FT fertility treatment including cycle-based (ovarian stimulation, IUI, or IVF), medical, or surgical treatment; DI donor insemination; FET frozen embryo transfer; TI timed intercourse; NR not reported

*ALL present male factors, female factors, unexplained factors

Definition #1: Discontinuation was defined as couples who withdraw from fertility care without achieving pregnancy

Definition #2: Discontinuation was defined as participants who withdraw from the program before treatment started and during treatment

Definition #3: Discontinuation was defined as participants who had not sought infertility treatment

Definition #4: Discontinuation was defined as couple who informed the Center for Human Reproduction staff of their decision to abandon diagnostic work-up or treatment, or they failed to return for follow-up appointments for 3 months

Definition #5: Discontinuation was defined as participants who did not obtain a clinical pregnancy in the first or second cycle but left the program

Definition #6: Discontinuation was defined as patients who did not return for treatment during the study period

Definition #7: Discontinuation was defined as patients who stopped for medical reasons or for personal reasons

Definition #8: Discontinuation was defined as patients who discontinued treatment in the center after the first failed IVF

Definition #9: Discontinuation was defined as patients stopping for medical reasons, stopping for personal reasons, or switching to IVF with donor semen

Definition #10: Discontinuation was defined as patients who discontinued the treatment after failed ART cycles

Definition #11: Discontinuation was defined as patients when they did not return for a further IVF cycle within 1 year after the failure of the previous cycle before they had completed the planned number of treatment cycles

Definition #12: Discontinuation was defined as patients who withdrew from the program before a pregnancy was established or until 3 IVF cycles had been completed

Definition #13: Discontinuation was defined as couples who discontinuing the IVF treatment without achieving pregnancy or without a suggestion by the medical staff to discontinue treatment for medical reasons

Definition #14: Discontinuation was defined as women who cancel treatment with having started stimulation but without reaching oocyte retrieval

Definition #15: Discontinuation was defined as no subsequent attempt in the IVF unit for at least 2 years at the time of data acquisition, whatever the reason for discontinuation (decision to stop IVF treatment, relocation to another area, decision to pursue treatment in another IVF center, etc)

Definition #16: Discontinuation was defined as women who did not receive treatment at least 2 years in the IVF center whatever the reason for discontinuation

Definition #17: Discontinuation was defined as participants who stopped fertility treatment at the 1-year follow-up

Definition #18: Discontinuation was defined as a couple who had not utilized six completed cycles of IUI, which reimbursed by Dutch health care companies and had not achieved an ongoing pregnancy

Definition #19: Discontinuation was defined as patients who discontinued their treatment prematurely (less than three IVF/ICSI cycles or had other treatment options)

Definition #20: Discontinuation was defined as patients who discontinued treatment or lack of treatment and follow-up procedure due to different reasons during the treatment

Definition #21: Discontinuation was defined as couples who discontinued IVF treatments before achieving two children in a completely unlimited cost-free environment

Definition #22: Discontinuation was defined as a patient with a failed cycle who opted not to proceed with further treatment despite a favorable prognosis and ability to pay or cover the costs of treatment

Definition #23: Not defined

Definition #24: Discontinuation was defined as participants who were not receiving care for a period of at least 1 year, or they had not completed six fresh and frozen autologous embryo transfer cycles

Definition #25: Discontinuation was defined as participants who missed one appointment at the fertility center and did not return or ask for a new consultation before December 2013

Definition #26: Discontinuation was defined as participants who discontinued treatment if they did not return to our clinic within 365 days of an unsuccessful first cycle

Definition #27: Discontinuation was defined as patients who was not to commence a new treatment cycle in the 6 months after a failed attempt to achieve an ongoing pregnancy

Definition #28: Discontinuation was defined as patients if they did not return during this period (6 months after unsuccessful ART)

Definition #29: Discontinuation was defined as women who, after a first unsuccessful IVF cycle, failed to return for a subsequent fresh or frozen IVF cycle within 12 months, independent of whether or not they had remaining embryos cryopreserved

Outcome measures of discontinuation in fertility treatment

There is currently no gold standard for the measurements of fertility treatment discontinuation, which varies across the included studies in terms of definitions and treatment cycles of discontinuation. A total of 29 definitions were reported in the included studies (see Table 1), with the most common definition being couples who discontinue fertility care without achieving pregnancy (n = 5, 17.24%) [25, 39, 41, 43, 60]. Discontinuation from fertility treatment can occur at any time between the patient’s first visit to the clinic and the last recorded cycle, especially for the ART regimen. Among the included studies, discontinuation in the first three treatment cycles was the most commonly studied (n = 16, 43.24%) [27–30, 34, 36, 37, 40–42, 46, 51, 53, 54, 56–58, 61]. Additionally, the reporting of discontinuation cycles also varied across the included studies, with the majority of studies reporting the specific number of cycles (n = 21, 56.76%) [27–30, 32, 34–37, 40–42, 44, 46, 51, 53–55, 57, 58, 61] or mean number of cycles (n = 4, 10.81%) [25, 26, 45, 52] or both [48]. Meanwhile, eight studies (21.62%) did not clarify either the range or the mean number of cycles [31, 33, 38, 39, 47, 49, 56, 59], and the remaining three studies (8.11%) did not report the cycles [43, 50, 60].

Factors associated with discontinuation

Supplementary Table SIII provides the potential influencing factors examined in the included studies. Among the included 37 studies, 34 studies mentioned the socio-economic-related factors, followed by condition-related (n = 24), patient-related (n = 19), treatment-related (n = 16), and healthcare system-related dimensions (n = 7) (see Fig. 2). In total, forty-two factors were identified and grouped under the five WHO-MAM dimensions (see Fig. 3), with twelve patient-related factors, eleven socio-economic-related factors, eight treatment-related factors, seven condition-related factors, and four healthcare system-related factors, and a detailed explanation for these factors is presented in Supplementary Table SIV.

Fig. 2.

Number of studies in WHO-MAM dimensions. WHO-MAM, World Health Organization Multidimensional Adherence Model

Fig. 3.

Factor of discontinuation in fertility treatment according to the WHO-MAM model. WHO-MAM, World Health Organization Multidimensional Adherence Model

aWe integrated the themes of “societal influences” into “woman’s social support”

bWe summarized the themes of “hope and difficulty letting go,” “fear of regret,” and “negative thoughts” as the “woman’s negative perception”

cWe summarized the themes of “age-related success rates,” “anecdotal stories of success,” “outcome of previous cycles,” and “perceived likelihood of success” as the “treatment success rates”

dNature of treatment refers to physical complications, low success of the treatments, centralized possibilities, and prolonged treatment procedures

Commonly reported factors in the socio-economic dimension are woman’s and man’s age, woman’s and man’s education level, parity, ethnicity, and household income; patient-related dimension are depression and anxiety symptoms; condition-related dimension are infertility duration, infertility types, infertility categories, number of embryo transfer, and number of oocyte retrievals; treatment-related dimension are number of treatment cycles and treatment success rate; healthcare system-related dimension are insurance coverage for fertility treatment.

Seven factors, including education level, female and male social support, treatment insurance coverage, a higher number of embryos frozen, engagement in IVF treatment (as opposed to IUI or drug treatment), and receiving conventional ovarian stimulation dosage, were reported to be negatively associated with treatment discontinuation; while eight factors were positively associated with discontinuation, including African American women, multiparous women, depression, female and male acceptance of infertility, relational strain, male infertility, longer duration of infertility, and fertility treatment. However, the effect of female age on treatment discontinuation shows inconsistent findings (see Supplementary Table SV). Additionally, the barriers in a mixed method study (only the qualitative part) [50] were reported to be the nature of the treatments, negative thoughts, and social-cultural values. Another qualitative study [59] identified the emotional and cognitive drivers, which included perceptions of success, hope, optimism, and fear of regret.

Regarding modifiable and non-modifiable factors, the patient-related factors, healthcare system factors, and some treatment-related factors (e.g., treatment cycles and ovarian stimulation dosage) were categorized into modifiable factors. Alternatively, non-modifiable factors consisted of socio-economic factors, condition-related factors, and some treatment-related factors (e.g., treatment duration) (see Supplementary Table SVI).

Statistical methods for examining factors

Studies varied considerably on the methodology used to investigate the influencing factors (see Supplementary Table SIII). For qualitative studies, one study used the Collaizzi seven-stage method [50], and another used thematical analysis [59]. Regarding quantitative studies, sixteen studies (43.24%) primarily used t-tests, analysis of variance, the Mann–Whitney U test, χ2 tests, and the Fisher exact test to identify whether single factors differed between discontinuers and continuers [25–33, 35, 38, 39, 43, 45, 48, 55]; eleven studies (29.73%) used the cox or logistic regressions to test the predictive model of discontinuation [36, 40–42, 46, 47, 51, 53, 56, 58, 60]; five studies (13.51%) used both [34, 49, 54, 57, 61]; and one study [37] used Wilson’s method, and the remaining two studies [44, 52] did not report the statistical analysis method.

Discussion

Main findings

This scoping review identified 37 studies and highlighted a broad spectrum of socio-economic, patient-related, condition-related, treatment-related, and healthcare system-related factors associated with discontinuation in fertility treatment. Among these factors, the socio-economic factors were the most studied, while the healthcare system-related factors were the least. Common factors contributing to discontinuation were multiparous women, depression, male infertility, and longer duration of infertility, whereas factors commonly hindering discontinuation were higher education level and adequate treatment insurance coverage. Additionally, common modifiable and non-modifiable factors, such as female age, infertility duration, anxiety, depression, and insurance coverage, relating to treatment discontinuation can be translated into health interventions and policymaking actions.

Interpretation of the findings

Our review presented a comprehensive summary of factors associated with discontinuation in fertility treatment and reinforced the findings in previous systematic reviews. In addition to the socio-demographic, psychosocial, treatment, interpersonal, and financial factors related to treatment discontinuation identified in the previous reviews [5, 9], the current scoping review has brought together the factors identified in the quantitative and qualitative study and further classified it with a theoretical model. Beyond these aforementioned factors, our review also identified some new factors on the socio-economic (marital status, social-cultural values), condition-related (number of motile sperm), patient-related (BMI, FSH, smoking behavior, social support, relational strain, negative perception, acceptance of infertility), treatment-related (time interval between course), and healthcare system-related dimensions (healthcare provider’s type, provider’s guidance, insurance coverage, different centers). Meanwhile, the WHO-MAM aided the analysis of the results of our review and helped to conceptualize and illustrate factors of fertility treatment discontinuation among infertile patients. According to our model-guided analysis, the likelihood of infertile patients discontinuing fertility treatment is not a simple linear process, and the factors in the five dimensions may individually and collectively exert influences on this set of relationships and the likelihood of treatment discontinuation. In all, using the WHO-MAM enhances our findings to generate more in-depth explanations and better describe the landscape of fertility treatment discontinuation compared to previous reviews.

Modifiable and non-modifiable factors that contribute to treatment discontinuation can constitute intervention targets. Certain socio-economic-related and condition-related factors facilitating discontinuation, such as multiparous women, older ages, higher education level, male or severe male infertility, and longer infertility duration, may not be modifiable; however, interventions can differentially target these groups. This review also proposed that discontinuation can be attributed to patients-related factors (e.g., anxiety, depression, social support) and healthcare system-related factors (e.g., healthcare providers’ guidance, healthcare provider’s types, insurance coverage), which are the main modifiable hindering factors of discontinuation that can be targeted for intervention development. Some psychological interventions, including cognitive-behavioral therapy intervention and body-mind intervention targeting anxiety and depression symptoms, are recommended for infertile patients [62]. Meanwhile, to maximize the benefits of an intervention, the social support system of the infertile patients, including family members and healthcare providers, should be assessed and involved if so desired by the infertile patients. Furthermore, in order to engage patients in fertility treatment, healthcare providers are also advised to reassess the treatment therapy after each failure cycle and provide objective and realistic information for patients, especially provide statistics around their chance of success 56, and the healthcare provider guidance should be based on patient-centered care and shared decision-making during fertility treatment [63]. In addition, health insurance policies that address reproductive health and rights are critical, especially in low- and middle-income countries that do not cover the cost of infertility treatment [64].

Knowledge gaps and future directions

This scoping review identifies factors associated with discontinuation in fertility treatment and also addresses some knowledge gaps that have been inadequately studied. First, the vast majority of studies were conducted in high-income countries. It is possible that countries with different policies and socio-cultural environments could have dissimilar factors of treatment discontinuation, and as such urgent attention would be warranted on middle- and low- income countries. Second, only one study [49] examines the potential clinical factors of treatment discontinuation from the professionals’ perspective, which highlights a major omission from the literature: the healthcare providers’ perspective. Third, 94.59% of studies used quantitative study design to collect the potential factors, with only two studies (including one mixed method study) employing qualitative design. There is lacking studies investigating the factors by using qualitative analysis methods. Moreover, in order to obtain the comprehensive factors of fertility treatment discontinuation, using the mixed method design (quantitative-qualitative design) to explore the associated factors in multi-levels, especially at the healthcare system level, should be a research focus in the future. Fourth, 29 definitions of fertility treatment discontinuation were reported in the included studies. This suggests that the definition of treatment discontinuation still lacks a “gold standard” measurement method, and expert consensus on the definition of treatment discontinuation in the fertility context is needed. Fifth, this review also presented the effect direction of some factors and, meanwhile, identified the factors showing inconsistent findings on treatment discontinuation, providing further directions for the researcher. Sixth, the modifiable factors were identified in this review, which could guide clinicians in the development of interventions to prevent early discontinuation in fertility treatment. Future research should focus on determining which factors have the greatest effect on treatment discontinuation, in addition to developing and evaluating interventions targeted at these factors. Seventh, the statistical analysis method of fertility treatment discontinuation factors varied considerably in the included studies, and meanwhile, the current statistical analysis method emphasized measuring whether a variable/factor was associated with fertility treatment discontinuation at a single level. The identification of which factors have the main effects on treatment discontinuation and the mechanism of factors across the five dimensions toward treatment discontinuation is still unclear. More research is required to explain discontinuation, and this could be achieved by conducting theory-led research. Last, many included studies lacked detailed descriptions of their population, treatment discontinuation cycles/stages, and statistical procedures. It is recommended that future publications describe these elements in greater detail, which will allow readers to better assess the quality and improve the ability to make comparisons between studies.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this review are its systematic review of 30 years of research on the discontinuation of all types of fertility treatment, which yielded 37 quantitative and qualitative studies from 13 countries, sampling 41,973 infertile patients and providing more robust and comprehensive findings than previous reviews. We made considerable effort to include all relevant studies, which included contacting authors to clarify the information that needed to be present in the current review, and meanwhile, we also captured some factors, including healthcare system-related factors, some patient-related factors (e.g., woman’s BMI, smoking behavior, social support) and some socio-economic factors (e.g., marital status, socio-cultural values) that were not mentioned previously. This review also mapped the factors into WHO-MAM dimensions, which is a suitable framework to systematically summarize the factors relating to the treatment discontinuation behavior and visualize the factors intuitively and concisely. Moreover, this review lent insight into potentially overlooked or inconsistent factors, providing direction for future research in this field. Furthermore, this review identified several modifiable and non-modifiable factors, which can inform interventions aimed at preventing early treatment discontinuation for infertile couples. Additionally, this review employed an established and multistage process as outlined by Arksey and O’Malley and reported the results in accordance with the PRISMA-ScR checklist, which can enhance the rigor and transparency of this scoping review design and the trustworthiness of our findings.

This scoping review has several limitations. Selection bias may exist in the current review because only articles published in English were included, but the exclusion of non-English language studies has been identified as a necessary tradeoff to enhance feasibility [65]. The generalizability of the findings may be limited because the majority of included studies were conducted in high-income countries. Meanwhile, the findings were concluded based on the 37 studies from 13 countries, and researchers should be cautious about extrapolating the findings to other countries. The lack of structured quality appraisal of the included studies has been recognized as a limitation of scoping review methodology but coincides with the goal of assessing the current scope of literature related to a topic rather than producing a synthesized answer to a particular question [12]. Moreover, though Arksey and O’Malley suggest that consultation is an optional component of the scoping study [10], the lack of consultation with stakeholders also constitutes a limitation of this review. Furthermore, the significant variability in outcome measures of discontinuation, study samples, statistical analysis methods, and reporting quality of the included studies creates difficulty in drawing definitive conclusions with regard to the directions of factors. Additionally, our review also included the quantitative studies which only use the univariate analysis method (e.g., t-test, x2 test) to measure factors. However, this inclusive approach to study selection was necessary because there are scant works published on the specific topic of fertility treatment discontinuation factors, and our aim was not only to collect comprehensive factors, but also to identify research gaps and future directions.

Conclusions

This is the first scoping review bringing together a wide range of factors influencing fertility treatment discontinuation with the use of the WHO-MAM framework and further categorizing them into modifiable and non-modifiable factors, providing recommendations to researchers, clinicians, and policymakers. Stakeholders are called to explore methods overcoming the modifiable factors and developing effective multicomponent interventions that can reduce the fertility treatment discontinuation. Psychological and behavioral modification, such as cognitive behavioral therapy, could also be performed to improve the discontinuation in the context of fertility treatment. Other prevention strategies include prompting insurance coverage for fertility treatment that may also decrease the possibility of discontinuation. However, this review also revealed that the effect direction of some factors remains unclear in the current studies. Future work should enhance a comprehensive understanding of influencing factors, which will help identify women at high risk of treatment discontinuation and develop appropriate interventions and eventually improving the chances of achieving parenthood in infertile patients.

Supplementary information

(DOCX 47.1 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Dr. Xufei Luo (Evidence-Based Medicine Center of Lanzhou University) and Dr. Meng Lv (National Clinical Research Center for Child Health and Disorders) for their methodology support for this manuscript.

Author contribution

SQ, EN, and LJ designed and executed the study. SQ, BL, HT, and SY reviewed the literature and extracted the data. SQ analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors critically commented on and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data availability

All data analyzed in this study are included in this present manuscript.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Infertility. 2023. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/infertility. Accessed 16 July 2023.

- 2.Iba A, Maeda E, Jwa SC, Yanagisawa-Sugita A, Saito K, Kuwahara A, et al. Household income and medical help-seeking for fertility problems among a representative population in Japan. Reprod Health. 2021;18(1):165. doi: 10.1186/s12978-021-01212-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boivin J, Bunting L, Collins JA, Nygren KG. International estimates of infertility prevalence and treatment-seeking: potential need and demand for infertility medical care. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(6):1506–1512. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang L, Lu Q, Du J, Lv H, Tao S, Chen S, et al. Cumulative live birth rates of in vitro fertilization/intracytoplasmic sperm injection after multiple complete cycles in China. J Biomed Res. 2020;34(5):361–368. doi: 10.7555/JBR.34.20200035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghorbani M, Hoseini FS, Yunesian M, Salehin S, Keramat A, Nasiri S. A systematic review and meta-analysis on dropout of infertility treatments and related reasons/factors. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2022;42(6):1642–1652. doi: 10.1080/01443615.2022.2071604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gameiro S, Verhaak CM, Kremer JA, Boivin J. Why we should talk about compliance with assisted reproductive technologies (ART): a systematic review and meta-analysis of ART compliance rates. Hum Reprod Update. 2013;19(2):124–135. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dms045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Njagi P, Groot W, Arsenijevic J, Dyer S, Mburu G, Kiarie J. Financial costs of assisted reproductive technology for patients in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Open. 2023;2:hoad007. doi: 10.1093/hropen/hoad007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun H, Gong TT, Jiang YT, Zhang S, Zhao YH, Wu QJ. Global, regional, and national prevalence and disability-adjusted life-years for infertility in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: results from a global burden of disease study, 2017. Aging (Albany NY) 2019;11(23):10952–10991. doi: 10.18632/aging.102497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gameiro S, Boivin J, Peronace L, Verhaak CM. Why do patients discontinue fertility treatment? A systematic review of reasons and predictors of discontinuation in fertility treatment. Hum Reprod Update. 2012;18(6):652–669. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dms031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arksey H, O"Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Method. 2005;8(1):19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5:69. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):143. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peterson J, Pearce PF, Ferguson LA, Langford CA. Understanding scoping reviews: definition, purpose, and process. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2017;29(1):12–16. doi: 10.1002/2327-6924.12380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Health Services. Infertility treatment. 2023. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/infertility/treatment/. Accessed 16 July 2023.

- 16.Zegers-Hochschild F, Adamson GD, de Mouzon J, Ishihara O, Mansour R, Nygren K, et al. International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technology (ICMART) and the World Health Organization (WHO) revised glossary of ART terminology, 2009. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(5):1520–1524. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, Cogo E, Foerster V, Lefebvre C. PRESS peer review of electronic search strategies: 2015 guideline statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;75:40–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, et al. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version5.3. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ling S, Davies J, Sproule B, Puts M, Cleverley K. Predictors of and reasons for early discharge from inpatient withdrawal management settings: a scoping review. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2022;41(1):62–77. doi: 10.1111/dar.13311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alshaikhmubarak FQ, Keers RN, Lewis PJ. Potential risk factors of drug-related problems in hospital-based mental health units: a systematic review. Drug Saf. 2023;46(1):19–37. doi: 10.1007/s40264-022-01249-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sabate E. Adherence to long-term therapies. Evidence for action. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strike K, Chan A, Iorio A, Maly M, Stratford P, Solomon P. Predictors of treatment adherence in patients with chronic disease using the multidimensional adherence model: unique considerations for patients with haemophilia. J Haemophilia Pract. 2020;7(1):92–101. doi: 10.17225/jhp00152. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alvi Y, Khalique N, Ahmad A, Khan HS, Faizi N. World Health Organization dimensions of adherence to antiretroviral therapy: a study at Antiretroviral Therapy Centre. Aligarh. Indian J Community Med. 2019;44(2):118–124. doi: 10.4103/ijcm.IJCM_164_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Konstantinou P, Kassianos AP, Georgiou G, Panayides A, Papageorgiou A, Almas I, et al. Barriers, facilitators, and interventions for medication adherence across chronic conditions with the highest non-adherence rates: a scoping review with recommendations for intervention development. Transl Behav Med. 2020;10(6):1390–1398. doi: 10.1093/tbm/ibaa118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schover LR, Collins RL, Richards S. Psychological aspects of donor insemination: evaluation and follow-up of recipient couples. Fertil Steril. 1992;57(3):583–590. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)54904-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Danesh-Meyer HV, Gillett WR, Daniels KR. Withdrawal from a donor insemination programme. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1993;33(2):187–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828x.1993.tb02390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmidt L, Münster K, Helm P. Infertility and the seeking of infertility treatment in a representative population. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1995;102(12):978–984. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1995.tb10905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gleicher N, Vanderlaan B, Karande V, Morris R, Nadherney K, Pratt D. Infertility treatment dropout and insurance coverage. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;88(2):289–293. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(96)00172-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roest J, van Heusden AM, Zeilmaker GH, Verhoeff A. Cumulative pregnancy rates and selective drop-out of patients in in-vitro fertilization treatment. Hum Reprod. 1998;13(2):339–341. doi: 10.1093/humrep/13.2.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Vries MJ, De Sutter P, Dhont M. Prognostic factors in patients continuing in vitro fertilization or intracytoplasmic sperm injection treatment and dropouts. Fertil Steril. 1999;72(4):674–678. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(99)00334-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guerif F, Fourquet F, Marret H, Saussereau M-H, Barthelemy C, Lecomte C, et al. Cohort follow-up of couples with primary infertiilty in an ART programme using frozen donor semen. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:1525–1531. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.6.1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sharma V, Allgar V, Rajkhowa M. Factors influencing the cumulative conception rate and discontinuation of in vitro fertilization treatment for infertility. Fertil Steril. 2002;78(1):40–46. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)03160-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guerif F, Saussereau M-H, Barthelemy C, Lanoue M, Lecomte C, Ract V, et al. Achievement of second parenthood in an ART programme using frozen donor semen: cohort follow-up. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:1853–1857. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smeenk JM, Verhaak CM, Stolwijk AM, Kremer JA, Braat DD. Reasons for dropout in an in vitro fertilization/intracytoplasmic sperm injection program. Fertil Steril. 2004;81(2):262–268. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pelinck MJ, Vogel NE, Arts EG, Simons AH, Heineman MJ, Hoek A. Cumulative pregnancy rates after a maximum of nine cycles of modified natural cycle IVF and analysis of patient drop-out: a cohort study. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(9):2463–2470. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Verberg MF, Eijkemans MJ, Heijnen EM, Broekmans FJ, de Klerk C, Fauser BC, et al. Why do couples drop-out from IVF treatment? A prospective cohort study. Hum Reprod. 2008;23(9):2050–2055. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Verhagen TE, Dumoulin JC, Evers JL, Land JA. What is the most accurate estimate of pregnancy rates in IVF dropouts? Hum Reprod. 2008;23(8):1793–1799. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Akyuz A, Sever N. Reasons for infertile couples to discontinue in vitro fertilisation (IVF) treatment. J Reprod Infant Psyc. 2009;27(3):258–268. doi: 10.1080/02646830802409652. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brandes M, van der Steen JO, Bokdam SB, Hamilton CJ, de Bruin JP, Nelen WL, et al. When and why do subfertile couples discontinue their fertility care? A longitudinal cohort study in a secondary care subfertility population. Hum Reprod. 2009;24(12):3127–3135. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lintsen AM, Verhaak CM, Eijkemans MJ, Smeenk JM, Braat DD. Anxiety and depression have no influence on the cancellation and pregnancy rates of a first IVF or ICSI treatment. Hum Reprod. 2009;24(5):1092–1098. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pearson KR, Hauser R, Cramer DW, Missmer SA. Point of failure as a predictor of in vitro fertilization treatment discontinuation. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(4 Suppl):1483–1485. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.07.1732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eisenberg ML, Smith JF, Millstein SG, Nachtigall RD, Adler NE, Pasch LA, et al. Predictors of not pursuing infertility treatment after an infertility diagnosis: examination of a prospective U.S. cohort. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(6):2369–2371. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.03.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McDowell S, Murray A. Barriers to continuing in vitro fertilisation--why do patients exit fertility treatment? Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;51(1):84–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2010.01236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Soullier N, Bouyer J, Pouly JL, Guibert J, de La Rochebrochard E. Effect of the woman’s age on discontinuation of IVF treatment. Reprod Biomed Online. 2011;22(5):496–500. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2011.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khalili MA, Kahraman S, Ugur MG, Agha-Rahimi A, Tabibnejad N. Follow up of infertile patients after failed ART cycles: a preliminary report from Iran and Turkey. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2012;161(1):38–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2011.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Troude P, Ancelet S, Guibert J, Pouly JL, Bouyer J, de La Rochebrochard E. Joint modeling of success and treatment discontinuation in in vitro fertilization programs: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12:77. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-12-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vassard D, Lund R, Pinborg A, Boivin J, Schmidt L. The impact of social relations among men and women in fertility treatment on the decision to terminate treatment. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(12):3502–12. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Custers IM, van Dessel TH, Flierman PA, Steures P, van Wely M, van der Veen F, et al. Couples dropping out of a reimbursed intrauterine insemination program: what is their prognostic profile and why do they drop out? Fertil Steril. 2013;99(5):1294–1298. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huppelschoten AG, van Dongen AJ, Philipse IC, Hamilton CJ, Verhaak CM, Nelen WL, et al. Predicting dropout in fertility care: a longitudinal study on patient-centredness. Hum Reprod. 2013;28(8):2177–2186. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mosalanejad L, Parandavar N, Abdollahifard S. Barriers to infertility treatment: an integrated study. Glob J Health Sci. 2013;6(1):181–191. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v6n1p181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Troude P, Guibert J, Bouyer J, de La Rochebrochard E, DAIFI Group Medical factors associated with early IVF discontinuation. Reprod Biomed Online. 2014;28(3):321–329. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2013.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lande Y, Seidman DS, Maman E, Baum M, Hourvitz A. Why do couples discontinue unlimited free IVF treatments? Gynecol Endocrinol. 2015;31(3):233–236. doi: 10.3109/09513590.2014.982082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Van Dongen A, Huppelschoten AG, Kremer JA, Nelen WL, Verhaak CM. Psychosocial and demographic correlates of the discontinuation of in vitro fertilization. Hum Fertil (Camb). 2015;18(2):100–106. doi: 10.3109/14647273.2014.995240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Crawford NM, Hoff HS, Mersereau JE. Infertile women who screen positive for depression are less likely to initiate fertility treatments. Hum Reprod. 2017;32(3):582–587. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dew351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dodge LE, Sakkas D, Hacker MR, Feuerstein R, Domar AD. The impact of younger age on treatment discontinuation in insured IVF patients. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2017;34(2):209–215. doi: 10.1007/s10815-016-0839-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pedro J, Sobral MP, Mesquita-Guimarães J, Leal C, Costa ME, Martins MV. Couples’ discontinuation of fertility treatments: a longitudinal study on demographic, biomedical, and psychosocial risk factors. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2017;34(2):217–224. doi: 10.1007/s10815-016-0844-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bedrick BS, Anderson K, Broughton DE, Hamilton B, Jungheim ES. Factors associated with early in vitro fertilization treatment discontinuation. Fertil Steril. 2019;112(1):105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mumusoglu S, Ozbek IY, Coskun ZY, Polat M, Sokmensuer LK, Bozdag G, et al. PGT for aneuploidy does not affect three-cycle cumulative IVF discontinuation rate in women of advanced maternal age. Reprod Biomed Online. 2019;39(1):75–83. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2019.03.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Copp T, Kvesic D, Lieberman D, Bateson D, McCaffery KJ. ‘Your hopes can run away with your realistic expectations’: a qualitative study of women and men’s decision-making when undergoing multiple cycles of IVF. Hum Reprod Open. 2020;2020(4):hoaa059. 10.1093/hropen/hoaa059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Hirakawa M, Usui E, Mitsuyama N, Oshio T. Chances of pregnancy after dropping out from infertility treatments: evidence from a social survey in Japan. Reprod Med Biol. 2021;20(2):246–252. doi: 10.1002/rmb2.12377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Almquist RG, Barrera CM, Fried R, Boulet SL, Kawwass JF, Hipp HS. Impact of access to care and race/ethnicity on IVF care discontinuation. Reprod Biomed Online. 2022;44(6):1159–1168. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2021.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Masoumi SZ, Parsa P, Kalhori F, Mohagheghi H, Mohammadi Y. What psychiatric interventions are used for anxiety disorders in infertile couples? A systematic review study. Iran J Psychiatry. 2019;14(2):160–170. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Huppelschoten AG, de Bruin JP, Kremer JA. Independent and web-based advice for infertile patients using fertility consult: pilot study. JMIR Form Res. 2019;3(2):e13916. doi: 10.2196/13916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Morshed-Behbahani B, Lamyian M, Joulaei H, Rashidi BH, Montazeri A. Infertility policy analysis: a comparative study of selected lower middle- middle- and high-income countries. Global Health. 2020;16(1):104. doi: 10.1186/s12992-020-00617-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pham MT, Rajic A, Greig JD, Sargeant JM, Papadopoulos A, McEwen SA. A scoping review of scoping reviews: advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Res Synth Methods. 2014;5:371–385. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 47.1 kb)

Data Availability Statement

All data analyzed in this study are included in this present manuscript.