Abstract

Objective

United Kingdom guidelines recommend all infants born <30 weeks’ gestation receive neurodevelopmental follow-up at 2 years corrected age. In this study, we describe completeness and results of 2-year neurodevelopmental records in the National Neonatal Research Database (NNRD).

Design

This retrospective cohort study uses data from the NNRD, which holds data on all neonatal admissions in England and Wales, including 2year follow-up status.

Patients

We included all preterm infants born <30 weeks’ gestation between 1 January 2008 and 31 December 2018 in England and Wales, who survived to discharge from neonatal care.

Main outcome measures

Presence of a 2-year neurodevelopmental assessment record in the NNRD, use of standardised assessment tools, results of functional 2-year neurodevelopmental assessments (visual, auditory, neuromotor, communication, overall development).

Results

Of the 41 505 infants included, 24 125 (58%) had a 2-year neurodevelopmental assessment recorded. This improved over time, from 32% to 71% for births in 2008 and 2018, respectively.

Of those with available data: 0.4% were blind; 1% had a hearing impairment not correctable with aids; 13% had <5 meaningful words, vocalisations or signs; 8% could not walk without assistance and 9% had severe (≥12 months) developmental delay.

Conclusions

The proportion of infants admitted to neonatal units in England and Wales with a 2-year neurodevelopmental record has improved over time. Rates of follow-up data from recent years are comparable to those of bespoke observational studies. With continual improvement in data completeness, the potential for use of NNRD as a source of longer-term outcome data can be realised.

Keywords: Infant Development; Neonatology; Paediatrics; Intensive Care Units, Neonatal; Child Development

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC.

The National Neonatal Research Database (NNRD) holds 2-year outcome data for all babies admitted to neonatal units in England and Wales since 2007, but completeness and results over time have not been evaluated previously.

Routine data have previously been used to supplement bespoke collection in interventional trials.

Using routinely recorded outcome data for research has the potential to reduce costs and burden on participating centres and families.

Understanding the completeness of routine data is necessary to assess its suitability as a source of information on neurodevelopmental outcomes.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

Between 2008 and 2018, the proportion of included infants with 2-year neurodevelopmental assessment records in the NNRD increased over time, to over 70% in recent years.

The majority (≥87%) of infants reviewed were assessed using functional (non-validated) neurodevelopmental tools; however, only half had an assessment using a validated, standardised tool.

Rates of impairment were higher for the earlier gestation group across all domains, and there was no improvement seen over time.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY.

This cohort is larger than comparable studies, and the continuous 11-year period covered has afforded us the opportunity to examine functional outcomes longitudinally at population level.

Completeness of 2-year records from routine electronic patient records in England and Wales has improved over time and is comparable to that of outcome data in bespoke observational research studies, demonstrating the potential role and validity of using this routinely recorded data as source of outcome data for research.

We identified factors associated with missing 2-year neurodevelopmental assessment data.

Our findings suggest that there is opportunity for improvements in data completeness by targeting populations and neonatal units with a higher likelihood for missing data: babies born at later gestations, those with lower socioeconomic status, younger mothers and lower-level units.

Background

Very preterm-born infants have increased risk of later life complications including adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes compared with their term-born peers. Two-year outcomes are predictive of long-term functional outcomes.1 2 Providing this high-risk group with enhanced developmental surveillance at 2 years may permit earlier detection of developmental problems and provision of support.

In the UK, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends all infants born before 30+0 weeks’ gestation receive a ‘detailed face-to-face developmental assessment’ at 2 years corrected age.3 The neonatal unit that discharges the baby home is responsible for this.

Data from 2-year follow-up are held in the National Neonatal Research Database (NNRD). Two-year neurodevelopment data in the NNRD is sourced from a clinician-entered electronic patient record, which includes standardised and functional developmental outcomes. ‘Standardised’ outcomes refer to those obtained using validated neurodevelopmental assessment tools. The name of the tool is recorded, and scores can be entered for Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development 3rd edition, the Schedule of Growing Skills, and the Griffiths Mental Development Scales.

‘Functional’ outcomes refer to those derived from a questionnaire on functional abilities, developed through regional group consensus.4 These questions were designed for use by clinicians without additional training or expertise in neurodevelopmental assessment. When compared against assessments using the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, 3rd edition, they were found to identify children with no impairment with high validity, but lack sensitivity in the identification of impairment.5

The NNRD contains quality-assured data from the electronic patient records of infants admitted to UK neonatal units since 2007. In addition to 2-year data, the dataset includes demographic, clinical and organisational data from neonatal inpatient admissions. All units in England and Wales have contributed data since 2012 and 2013, respectively, providing whole population coverage for very preterm-born infants admitted to neonatal units.6 7

There is growing interest in the use of routinely recorded data to provide a more cost-efficient and less burdensome method to obtain outcome data for observational and interventional studies. However, the validity and generalisability of these data are dependent on the population attrition rates and data quality. It is known that infants who are lost to follow-up often differ from those who are not.8 Understanding completeness and quality of routinely recorded data is necessary to assess suitability for its use in research.

In this study, we examine the completeness and results of 2-year neurodevelopmental records in the NNRD and report the applied assessment tools.

Methods

Preterm infants born below 30 weeks’ gestation between 1 January 2008 and 31 December 2018, admitted to National Health Service (NHS) neonatal units in England and Wales and survived to discharge from neonatal care, were included. Babies with missing gestational age or birth year were excluded. For analyses of assessment results, infants known to be deceased post-discharge, prior to assessment, were excluded.

SAS V.9.4 and Stata V.16.0 software were used for data extraction and analysis. The following data were extracted from the NNRD: maternal, pregnancy and infant characteristics, and geographical region of birth responsible for coordinating the care pathway of the baby (known as the Operational Delivery Network (ODN)). We determined the designation of the discharging neonatal unit responsible for 2-year follow-up: special care baby unit being the lowest level, neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) being the highest and local neonatal units sitting between these.9 We derived the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) decile, a socioeconomic measure, using maternal postcode at the time of delivery.

We report the following

Presence of 2-year neurodevelopmental record

We determined the number and proportion of eligible infants with a 2-year neurodevelopmental record, defined as present if any 2-year neurodevelopmental assessment results fields were completed or if death prior to 2-year follow-up was recorded. We report reasons recorded for non-attendance.

Characteristics of the cohort and factors affecting completeness

We report characteristics of all babies eligible for follow-up and of those with and without a 2-year neurodevelopmental record separately. We explored factors associated with having this record using univariate and multiple logistic regression models. The models included the following variables: birth year, gestation, maternal age at birth, IMD decile, the number of different neonatal units to which the baby was admitted and level of unit of discharge. The multiple model adjusted only for these variables; infants with missing data for any of these variables were excluded. Gestational age at birth, birth year, IMD decile and maternal age were treated as continuous variables. The number of neonatal units was grouped into ‘one’ (reference category), ‘two’ and ‘three or more’. The reference category for level of unit of discharge was NICU.

Completeness over time and by geographical region (ODN)

We report the number and proportion of infants with a 2-year neurodevelopmental record across birth epochs (2008–2010, 2011–2014, 2015–2018), by gestation group (<27+0 and 27+0–29+6)10 and by ODN. The Cochran-Armitage test was used to test for a linear association between completeness and birth year.

Completeness of neurodevelopmental assessments at 2 years

We report completeness of functional and standardised neurodevelopmental assessments as a proportion of infants with a 2-year neurodevelopmental record who were not deceased.

Choice of standardised neurodevelopmental assessment tool

We report the name of the standardised neurodevelopmental assessment tool used.

Results of neurodevelopmental assessments at 2 years

We report results of neurodevelopmental assessments. Possible outcomes for functional assessments of visual, auditory, communication and neuromotor neurodevelopmental domains were ‘impairment’ or ‘no impairment’. For overall development, possible outcomes were: ‘normal’ (<3 months delay), ‘mild’ (3–6 months delay), ‘moderate’ (6–12 months delay) and ‘severe’ (>12 months delay).

Results for principal neurodevelopmental outcomes from each domain are reported by gestation in weeks, gestation group (as above) and birth epoch (as above). These principal outcomes are: blindness or light perception only (vision), hearing impairment not correctable with aids (auditory), having fewer than five meaningful words, vocalisations or signs (communication); being unable to walk without assistance (neuromotor); ‘mild’, ‘moderate’ or ‘severe’ developmental delay.

Results

Presence of 2-year neurodevelopmental records

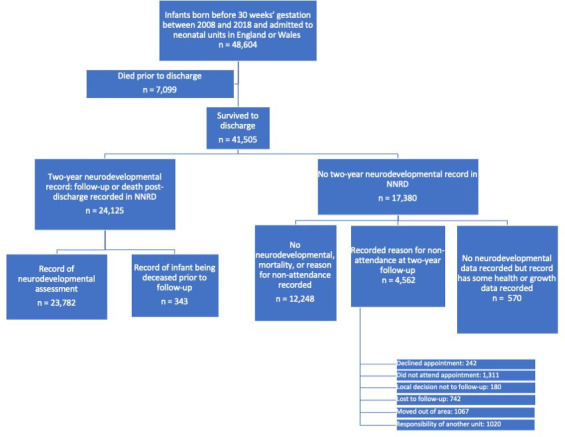

Among 48 604 infants born before 30 weeks’ gestation between 2008 and 2018, admitted to neonatal units in England or Wales, 41 505 survived to neonatal discharge (figure 1). Of these, 58% (24 125/41 505) had a record of 2-year neurodevelopmental assessment or death post-discharge. After discounting 343 records of death post-discharge, the eligible population for 2-year assessment was 41 162, of which 58% (23 782/41 162) had neurodevelopmental data recorded. Of the 17 380 infants without a 2-year neurodevelopmental record, 4562 (26%) had a reason for non-attendance recorded.

Figure 1.

Flow chart for the population eligible for 2-year neurodevelopmental follow-up. NNRD, National Neonatal Research Database

Characteristics of the cohort and factors affecting completeness

Table 1 describes characteristics of infants who survived to neonatal discharge, and those with and without a 2-year neurodevelopmental record.

Table 1.

Characteristics of cohort

| Characteristics | All eligible infants (N=41 505) |

Neurodevelopmental record or death post-discharge in NNRD (N=24 125) |

No neurodevelopmental record in NNRD (N=17 380) |

| Gestational age at birth (weeks) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 28 (26–29) | 27 (26–29) | 28 (26–29) |

| Maternal ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| Asian | 4824 (11.6) | 2935 (12.2) | 1889 (10.9) |

| Black | 4130 (10.0) | 2257 (9.4) | 1873 (10.8) |

| Mixed | 720 (1.7) | 401 (1.7) | 319 (1.8) |

| White | 26 521 (63.9) | 15 402 (63.8) | 11 119 (64.0) |

| Other | 656 (1.6) | 370 (1.5) | 286 (1.7) |

| Missing or unknown | 4654 (11.2) | 2760 (11.4) | 1894 (10.9) |

| IMD decile, n (%) | |||

| 1 | 6776 (16.3) | 3941 (16.3) | 2835 (16.3) |

| 2 | 5703 (13.7) | 3289 (13.6) | 2414 (13.4) |

| 3 | 4877 (11.8) | 2785 (11.5) | 2092 (12.0) |

| 4 | 4160 (10.0) | 2445 (10.1) | 1715 (9.9) |

| 5 | 3638 (8.8) | 2169 (9.0) | 1469 (8.5) |

| 6 | 3172 (7.6) | 1903 (7.8) | 1269 (7.3) |

| 7 | 2957 (7.1) | 1776 (7.4) | 1181 (6.8) |

| 8 | 2681 (6.5) | 1658 (6.9) | 1023 (5.9) |

| 9 | 2393 (5.8) | 1463 (6.1) | 930 (5.4) |

| 10 | 2076 (5.0) | 1317 (5.5) | 759 (4.4) |

| Missing or unknown | 3072 (7.4) | 1379 (5.7) | 1693 (9.7) |

| Maternal age (years) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 30 (26–35) | 31 (26–35) | 30 (25–35) |

| Missing, n (%) | 346 (0.8) | 133 (0.6) | 213 (1.2) |

| Number of different neonatal units that provided care, n (%) | |||

| 1 | 21 800 (52.5) | 12 662 (52.5) | 9138 (52.6) |

| 2 | 15 351 (37.0) | 9054 (37.5) | 6297 (36.2) |

| 3 | 3788 (9.1) | 2104 (8.7) | 1684 (9.7) |

| 4 or more | 566 (1.4) | 305 (1.3) | 261 (1.5) |

| Level of unit of discharge, n (%) | |||

| Special care baby unit (lowest level) | 5711 (13.8) | 2863 (11.9) | 2848 (16.4) |

| Local neonatal unit | 18 301 (44.1) | 10 574 (43.8) | 7727 (44.5) |

| Neonatal intensive care unit (highest level) | 17 493 (42.2) | 10 688 (44.3) | 6805 (39.2) |

NNRD, National Neonatal Research Database.

Results of univariate analyses are given in online supplemental table 1. 38,243 infants were included in the multiple logistic regression model. Following adjustment, later birth year, earlier gestation, greater maternal age, higher IMD decile and higher level of unit at discharge increased the probability of having a 2-year neurodevelopmental record (online supplemental table 2). Compared with receiving care in one unit, receiving care in three or more units increased the probability, but receiving care in two units did not.

fetalneonatal-2023-325746supp001.pdf (267.4KB, pdf)

Completeness over time and by geographical region (ODN)

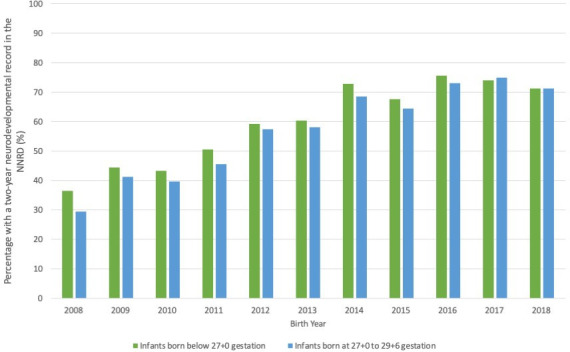

The proportion of patients with a 2 year neurodevelopmental record increased over time from 32% to 71% (births in 2008 and 2018 respectively) (online supplemental figure 1). The Cochran-Armitage test showed an association between birth year and presence of a 2 year neurodevelopmental record (p<0.001). Infants born <27 weeks had higher rates than those born 27+0–29+6 weeks (figure 2). The proportion of infants with a 2-year neurodevelopmental record ranged from 53% to 67% across ODNs (online supplemental table 3).

Figure 2.

Percentage of eligible infants with a 2-year neurodevelopmental record over time. NNRD, National Neonatal Research Database.

Completeness of functional and standardised assessments at 2 years

Of the 23 782 children with a 2-year neurodevelopmental record, individual functional outcomes were ≥87% complete (online supplemental table 4). Half, 11 777/23 782 (50%), had a standardised developmental assessment. The majority (61%) used Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development (online supplemental figure 2).

Results of neurodevelopmental assessments at 2 years

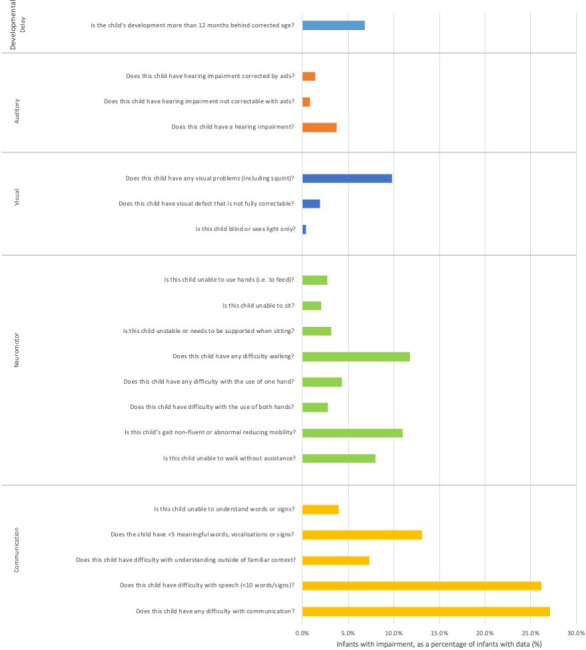

Functional neurodevelopmental outcomes and outcomes by gestation group and birth epoch are shown in figure 3 and table 2, respectively. Rates of impairment were higher for the earlier gestation group across all domains. Blindness or light perception only and hearing impairment not correctable with aids were relatively uncommon (<3%). Impairments in other domains were more common. 7% to 22% had fewer than five meaningful words, vocalisations or signs; 6–13% could not walk without assistance. Mild developmental delay (12–18%) was more common than moderate (8–15%) or severe (4–11%) delay. Rates of impairment do not appear to improve over time. Online supplemental tables 5,6 show functional outcomes by gestation and birth epoch, respectively.

Figure 3.

Impairment rates at 2-year follow-up, as a proportion of infants with available data.

Table 2.

Principal neurodevelopmental outcomes by gestation group and epoch for children with a record of neurodevelopmental assessment at 2 years, excluding those known to have died prior to 2-year follow-up

| Gestation group | Birth epoch | Developmental delay | Neuromotor: is this child unable to walk without assistance? | Communication: does this child have <5 meaningful words, vocalisations or signs? | Vision: is this child blind or sees light only? | Auditory: does this child have hearing impairment not correctable with aids? | |||||||

| Data available, n | Mild*, n (%) |

Moderate*, n (%) |

Severe*, n (%) |

Data available, n | Impairment, n (%) |

Data available, n | Impairment, n (%) |

Data available, n | Impairment, n (%) |

Data available, n | Impairment, n (%) |

||

| <27 | 2008–2010 | 1188 | 190 (16) | 153 (13) | 129 (11) | 1326 | 173 (13) | 1279 | 221 (17) | 1276 | <5 (<0.4) | 1267 | 31 (2.4) |

| 2011–2014 | 2644 | 481 (18) | 363 (14) | 262 (10) | 2902 | 304 (10) | 2816 | 466 (17) | 2765 | 21 (0.8) | 2753 | 34 (1.2) | |

| 2015–2018 | 2996 | 525 (18) | 450 (15) | 331 (11) | 3406 | 353 (10) | 3335 | 722 (22) | 3286 | 26 (0.8) | 3255 | 31 (1.0) | |

| 27+0–29+6 | 2008–2010 | 2346 | 286 (12) | 180 (7.7) | 87 (3.7) | 2613 | 200 (7.7) | 2530 | 173 (6.8) | 2535 | 9 (0.4) | 2506 | 19 (0.8) |

| 2011–2014 | 5170 | 744 (14) | 464 (9.0) | 258 (5.0) | 5818 | 403 (6.9) | 5643 | 561 (9.9) | 5528 | 16 (0.3) | 5500 | 27 (0.5) | |

| 2015–2018 | 6299 | 867 (14) | 551 (8.7) | 335 (5.3) | 7244 | 418 (5.8) | 7076 | 823 (12) | 7019 | 16 (0.2) | 6974 | 44 (0.6) | |

*Definitions for developmental delay: ‘mild’ (3 to 6 months delay), ‘moderate’ (6 to 12 months delay), ‘severe’ (over 12 months delay). Numbers below 5 are masked.

Due to low rates of completeness, and variety in assessment tools used, results from standardised assessments are not reported.

Discussion

In this whole population study, 24 125 of an eligible population of 41 505 had a 2-year record of neurodevelopmental assessment or death. Completeness improved over time to above 70% in recent years. Our regression analysis showed that 2-year records were not missing at random, suggesting opportunity for improving completeness by targeting groups with higher likelihoods for missing data. These include babies born at later gestations, those with lower socioeconomic status, younger mothers and lower-level units. We speculate that the association between gestational age and likelihood of a follow-up record may be due to higher rates of morbidities seen at earlier gestations and increased need for medical care following discharge. Most children had functional assessments. Higher rates of impairment were seen in the earlier gestation group, as expected. We did not find improvement in impairment rates over time. We speculate this may be due to a changing population, with increasing numbers of infants surviving at lower gestations.11 Only half received a standardised assessment, likely due to their being time-consuming and requiring a trained assessor.

Availability of 2-year data in the NNRD in recent years (>70%) exceeds that seen in some large prospective observational cohort studies of very preterm infants that used bespoke outcome data collection. EPICure-2, an English prospective national cohort study, evaluated 576/1031 (55%) of their cohort in face-to-face assessments at 3 years.12 The Effective Perinatal Intensive Care in Europe (EPICE) study, a European population-based prospective cohort study, had 2-year corrected outcome data (obtained by questionnaire) for 4426/6792 (66%).13 Unlike these examples, our study used routine data extracts.

Studies using national registries or databases as their source for outcome data have completeness similar to or exceeding that of the NNRD. The Extremely Preterm Infants-Dutch Analysis on Follow-up (EPI-DAF) Study, a national cohort study using registry data, had 2-year data available for 554/651 (85%) of the eligible cohort.14 A Belgian population-based cohort study using a national database had 2-year data for 1089/1783 (61%) of their eligible cohort.15 In both studies, higher proportions of children followed up were assessed using standardised developmental tools (79–89% and 96%, respectively).14 15

Rates of 2-year data in the NNRD in recent years approach, but remain below, completeness seen in large interventional trials. The Speed of Increasing Milk Feeds Trial (SIFT) had 88% available 2-year outcome data,.16 The Caffeine for Apnoea of Prematurity (CAP) trial had 93% adequate outcome data.17

Our study has key strengths. The NNRD has whole population coverage for neonatal care of very preterm infants. Our study uses only routinely recorded data, reducing costs, workload and the burden imposed on families by duplication of assessments. Our cohort is larger than comparable studies; 6792 infants were eligible for follow-up in the largest aforementioned study (EPICE)13 versus 41 505 in our study. Our cohort covers a longer time-period than comparable studies. EPIPAGE-2 (a French national cohort study) and EPICure-2 both compare cohorts born in two 1-year periods.12 18 The continuous 11-year period covered allowed us to examine functional outcomes longitudinally at population level.

Our study has several limitations. Missing data may not represent non-attendance; an assessment may occur without being entered into the correct system. Possible explanations include lack of awareness or resources to support health professionals. This may in part explain the poorer completeness in lower-level units, which we speculate may have fewer resources. Second, due to low rates of standardised assessments and variety of tools used, we did not report these results. Third, there is variation in follow-up practices between units.19 In exploring factors influencing completeness, we were unable to include important local factors, such as follow-up co-ordinators, as this information was not available. It is likely that unmeasured factors influenced the likelihood of follow-up. Fourth, although practical and easy to use, functional assessments are not gold standard and may underestimate the prevalence of impairment.20

The improvement in completeness over time is likely multifactorial and reflects introduction of formal guidance, incentives and greater data visibility over the period of interest, facilitated by the National Neonatal Audit Programme (NNAP). In 2014, NNAP identified 2-year follow-up as an important quality improvement opportunity.21 Changes to ameliorate data completeness included reporting by hospital versus network level and allocating responsibility for follow-up to discharging units. Some ODNs introduced 2-year follow-up targets in their payment framework.20 In their 2017 guideline for developmental follow-up of preterm infants, NICE recommended assessment at 2-year corrected age for children born before 30 weeks.3

Unit and network-level insights provided by NNAP are crucial to informing quality improvement efforts. Ongoing efforts to improve follow-up rates include the recent introduction of ODN-level discharge coordinators.22

Using routine data for research improves feasibility and reduces costs. Two-year outcomes are commonly reported in research, balancing improved predictive accuracy at older ages with increasing risk of attrition over time.23 The quality of 2-year data in the NNRD, as examined in this study, is crucial to understand its potential for use in research. Routinely recorded 2-year data has previously been used to supplement study-specific collection in interventional studies. Outcome data for 10% of the patients enrolled in the SIFT trial were sourced from the same electronic patient records, which populate the NNRD.16 Using a database to avoid duplicative data collection for interventional studies has been shown to be feasible and acceptable in the UK.24

The low rate of standardised assessments likely reflects the challenge of undertaking time-consuming validated assessments. Improving completeness of standardised assessments in the NNRD would enhance its potential for use in research. The Parent Report of Children’s Abilities-Revised (PARCA-R) is a validated, cost-effective parent-completed questionnaire used for developmental screening25 26 and has been used in interventional trials.27 The increase in ‘other’ standardised assessments used for infants born in 2018 (online supplemental figure 2) may reflect increased use of PARCA-R. A recent revision of the neonatal dataset enables capture of PARCA-R assessments in the NNRD, and systematic capture of an electronic version has been piloted successfully (ePARCA-R).28 Practicality of this tool may improve completeness of 2-year standardised assessments sufficiently for use of this routinely recorded data for research.

Conclusions

In recent years, two-year neurodevelopmental outcomes are available for over two-thirds of survivors born before 30 weeks in England and Wales. Those born to younger mothers, from lower socioeconomic status, at later gestations and discharged from a lower-level unit have a higher chance of missing data and offer opportunity for targeted improvements in 2-year follow-up programmes nationally. Continual improvements in 2-year outcome data will support the use of routinely recorded records as a more cost-efficient and practical source of outcome data.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mohammad Chehrazi, Sena Jawad, Angela Huertas-Ceballos and Anusha Arasu.

Footnotes

Twitter: @docevb, @NeenaModi1, @DrCBattersby

Collaborators: UK Neonatal Collaborative (UKNC) for England and Wales: Dr Matthew Babirecki, Dr Rebecca Kettle, Dr Anand Kamalanathan, Dr Clare Cane, Dr Kavi Aucharaz, Dr Rathod Poorva, Dr Maninder Bal, Dr L M Wong, Dr Anita Mittal, Dr Penny Broggio, Dr Pinki Surana, Dr Matt Nash, Dr Sam Wallis, Dr Ahmed Hassan, Dr Karin Schwarz, Dr Shu-Ling Chuang, Dr Penelope Young, Dr Ramona Onita, Dr Mani Kandasamy, Dr Stephen Brearey, Dr Morris/Dr Siramhatia, Dr Yee Aung, Dr Bharath Gowda, Dr Mehdi Garbash, Dr Alex Allwood, Dr Pauline Adiotomre, Dr Nigel Brooke, Dr Claire Hollinsworh, Dr Toria Klutse, Dr Sonia Spathis, Dr Sathish Krishnan, Dr Samar Sen, Dr Alaa Ghoneem, Dr Jennifer Holman, Dr Daniel Dogar, Dr Girish Gowda, Dr Karen Turnock, Dr Sobia Balal, Dr Cath Seagrave, Dr Tristan Bate, Dr Hilary Dixon, Dr Narendra Aladangady, Dr Hassan Gaili, Dr Matthew James, Dr M Lal, Dr Oluseun Tayo, Dr Abraham Isaac, Dr Carolina Zorro, Dr Dhaval Dave, Dr Jonathan Filkin, Dr Savi Sivashankar, Dr Hannah Shore, Dr Jo Behrsin, Dr Jo Behrsin, Dr Michael Grosdenier, Dr Ruchika Gupta, Dr Ather Ahmed, Dr Nim Subhedar, Dr Jennifer Birch, Dr Surendran Chandrasekaran, Dr Ashok Karupaiah, Dr Ghada Ramadan, Dr I Misra, Dr Chris Knight, Dr Richard Heaver, Dr Mohammad Alam, Dr Prakash Thiagarajan, Dr Muthukumar, Dr Tiziana Fragapane, Dr Bivan Saha, Dr Cheentan Singh, Dr Nick Barnes, Dr Sangeeta Tiwary, Dr Richard Nicholl, Dr Dush Batra, Dr Dush Batra, Dr Victoria Nesbitt, Dr Amit Gupta, Dr Katharine McDevitt, Dr Ruchika Gupta, Dr David Gibson, Dr Peter Mcewan, Dr Sanath Reddy, Dr Mark Johnson, Dr Aesha Mohammedi, Dr Patricia Cowley, Dr Rashmi Gandhi, Dr Charlotte Groves, Dr Lidia Tyszcuzk, Dr Shilpa Ramesh, Dr Salamatu Jalloh, Dr Julia Croft, Dr Bushra Abdul-Malik, Dr Dominic Muogbo, Dr Ambalika Das, Dr Khalid Mannan, Dr Rajiv Chaudhary, Dr Soma Sengupta, Dr Christos Zipitis, Dr Kemy Naidoo, Dr Archana Mishra, Dr Chris Warren, Dr Nigel Ruggins, Dr Chrissie Oliver, Dr Lucinda Winckworth, Dr Joanne Fedee, Dr Anitha Vayalakkad, Dr Richa Gupta, Dr Lee Abbott, Dr Jo MacLeod, Dr Aesha Mohammedi, Dr Rebecca Winterson, Dr Naveen Athiraman, Dr Anjali Pektar, Dr Jim Baird, Dr Adedayo Owoeye, Dr Umapathee Majuran, Dr Richard Lindley, Dr Vineet Gupta, Dr Faith Emery, Dr Donovan Duffy, Dr Salim Yasin, Dr Hannah Shore, Dr Akinsola Ogundiya, Dr Lidia Tyszcuzk, Dr Arin Mukherjee, Dr Pamela Cairns, Dr Vennila Ponnusamy, Dr Victoria Sharp, Dr Carrie Heal, Dr Sanjay Salgia, Dr Imran Ahmed, Dr Helen Purves, Dr Porus Bastani, Dr Eleanor Bond, Dr Divyen Shah, Dr Esther Morris, Dr Se-Yeon Park, Dr Giles Kendall, Dr Puneet Nath, Dr Igor Fierens, Dr Mehdi Garbash, Dr Hari Kumar, Dr Peter Curtis, Dr Delyth Webb, Dr Bird, Dr Sankara Narayanan, Dr Yee Mon Aung, Dr Elizabeth Eyre, Dr Tayyaba Aamir, Dr Angela Yannoulias, Dr Caroline Sullivan, Dr Ros Garr, Dr Wynne Leith, Dr Shaveta Mulla, Dr Anna Gregory, Dr Edward Yates, Dr Abijeet Godhamgaonkar, Dr Megan Eaton, Dr Sundeep Sandhu, Dr Arun Ramachandran, Dr Abby Parish, Dr Anitha James, Dr Ambrose Onibere, Dr Artur Abelian, Dr Shakir Saeed, Dr Nitin Goel, Dr David Deekollu, Dr Prem Pitchaikani.

Contributors: CB, SNU, EvB and TS were involved in the study design. JL and EvB carried out data curation. TS and EvB undertook data analysis. All authors contributed to data interpretation. EvB wrote the first draft of the paper. All authors contributed to subsequent drafts of the paper and agreed for the final version to be submitted. CB is responsible for the overall content as guarantor.

Funding: This work represents independent research funded in part by a personal NIHRThis work represents independent research funded in part by a personal NIHR

Competing interests: EVB is funded through a PhD studentship awarded by the Joint Research Committee (CW+ and Westminster Medical School Research Trust). NM directs the Neonatal Data Analysis Unit at Imperial College London and is the chief investigator for the National Neonatal Research Database. NM is a member of the Board of Trustees of the Academy of Medical Sciences, Action Cerebral Palsy, David Harvey Trust, and TheirWorld. NM is a member of the Nestle Scientific Advisory Board; she accepts no personal remuneration for this role. NM has current research grants from the Medical Research Council, National Institute of Health Research, March of Dimes, Chiesi, Takeda, Bayer and Critical Path Institute. NM is president-elect of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine. CB is funded through an NIHR Advanced Fellowship personal award. TS, JL and SU have no conflicts of interest relevant to the work under submission.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available. Study data are held in the National Neonatal Research Database (NNRD) by the Neonatal Data Analysis Unit (NDAU). Details of how to access the National Neonatal Research Database may be found at: https://www.imperial.ac.uk/neonatal-data-analysis-unit/neonatal-data-analysis-unit/utilising-the-nnrd/

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1. Breeman LD, Jaekel J, Baumann N, et al. Preterm cognitive function into adulthood. Pediatrics 2015;136:415–23. 10.1542/peds.2015-0608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Linsell L, Johnson S, Wolke D, et al. Cognitive Trajectories from infancy to early adulthood following birth before 26 weeks of gestation: a prospective, population-based cohort study. Arch Dis Child 2018;103:363–70. 10.1136/archdischild-2017-313414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. National Institute for Clinical Excellence . Developmental follow-up of children and young people born Preterm [NICE guideline no.NG72]. London: NICE, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. National Neonatal Audit Programme . TPRG/SEND/NNAP 2 year corrected age outcome form Royal college of Paediatrics and child health. 2018. Available: https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2018-03/nnap_two-year_outcome_form.pdf [Accessed 20 Sep 2022].

- 5. Wong HS, Cowan FM, Modi N, et al. Validity of neurodevelopmental outcomes of children born very Preterm assessed during routine clinical follow-up in England. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2018;103:F479–84. 10.1136/archdischild-2016-312535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Neonatal Data Analysis Unit Imperial College London . Utilising the National neonatal research database. 2020. Available: https://www.imperial.ac.uk/neonatal-data-analysis-unit/neonatal-data-analysis-unit/utilising-the-national-neonatal-research-database/ [Accessed 20 Sep 2022].

- 7. Battersby C, Statnikov Y, Santhakumaran S, et al. The United Kingdom national neonatal research database: A validation study. PLoS One 2018;13:e0201815. 10.1371/journal.pone.0201815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Piedvache A, van Buuren S, Barros H, et al. Strategies for assessing the impact of loss to follow-up on estimates of neurodevelopmental impairment in a very Preterm cohort at 2 years of age. BMC Med Res Methodol 2021;21:118. 10.1186/s12874-021-01264-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. National Neonatal Audit Programme . A guide to the 2022 audit measures, v1. London: Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) and the Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mactier H, Bates SE, Johnston T, et al. Perinatal management of extreme Preterm birth before 27 weeks of gestation: a framework for practice. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2020;105:232–9. 10.1136/archdischild-2019-318402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Morgan AS, Mendonça M, Thiele N, et al. Management and outcomes of extreme Preterm birth. BMJ 2022;376:e055924. 10.1136/bmj-2021-055924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Moore T, Hennessy EM, Myles J, et al. Neurological and developmental outcome in extremely Preterm children born in England in 1995 and 2006: the epicure studies. BMJ 2012;345:e7961. 10.1136/bmj.e7961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zeitlin J, Maier RF, Cuttini M, et al. Cohort profile: effective perinatal intensive care in Europe (EPICE) very Preterm birth cohort. Int J Epidemiol 2020;49:372–86. 10.1093/ije/dyz270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. van Beek PE, Rijken M, Broeders L, et al. Two-year neurodevelopmental outcome in children born extremely Preterm: the EPI-DAF study. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2022;107:467–74. 10.1136/archdischild-2021-323124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pascal A, Naulaers G, Ortibus E, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcomes of very Preterm and very-low-birthweight infants in a population-based clinical cohort with a definite perinatal treatment policy. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2020;28:133–41. 10.1016/j.ejpn.2020.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dorling J, Abbott J, Berrington J, et al. Controlled trial of two incremental milk-feeding rates in Preterm infants. N Engl J Med 2019;381:1434–43. 10.1056/NEJMoa1816654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schmidt B, Roberts RS, Davis P, et al. Long-term effects of caffeine therapy for apnea of Prematurity. N Engl J Med 2007;357:1893–902. 10.1056/NEJMoa073679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pierrat V, Marchand-Martin L, Arnaud C, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcome at 2 years for Preterm children born at 22 to 34 weeks' gestation in France in 2011: EPIPAGE-2 cohort study. BMJ 2017;358:j3448. 10.1136/bmj.j3448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chisholm P, Arasu A, Huertas-Ceballos A, et al. Neurodevelopmental follow-up for high-risk neonates: Current practice in great Britain. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2017;102:F558–9. 10.1136/archdischild-2017-312983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Modi N, Ashby D, Battersby C, et al. Developing routinely recorded clinical data from electronic patient records as a national resource to improve neonatal health care: the medicines for neonates research programme. Programme Grants Appl Res 2019;7:1–396. 10.3310/pgfar07060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. National Neonatal Audit Programme . Annual report on 2013. London: RCPCH; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 22. British Association for Neonatal Neurodevelopmental Follow Up . In: British Association for Neonatal Neurodevelopmental Follow-Up (BANNFU) Terms of Reference: British Association of Perinatal Medicine. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Marlow N. Is survival and neurodevelopmental impairment at 2 years of age the gold standard outcome for neonatal studies Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2015;100:F82–4. 10.1136/archdischild-2014-306191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gale C, Modi N, WHEAT trial development group . Neonatal randomised point-of-care trials are feasible and acceptable in the UK: results from two national surveys. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2016;101:F86–7. 10.1136/archdischild-2015-308882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Johnson S, Bountziouka V, Brocklehurst P, et al. Standardisation of the parent report of children's abilities-revised (PARCA-R): a norm-Referenced assessment of cognitive and language development at age 2 years. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2019;3:705–12. 10.1016/S2352-4642(19)30189-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Martin AJ, Darlow BA, Salt A, et al. Performance of the parent report of children’s abilities-revised (PARCA-R) versus the Bayley scales of infant development III. Arch Dis Child 2013;98:955–8. 10.1136/archdischild-2012-303288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. INIS Collaborative Group, Brocklehurst P, Farrell B, et al. Treatment of neonatal sepsis with intravenous immune globulin. N Engl J Med 2011;365:1201–11. 10.1056/NEJMoa1100441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Modi N, Johnson S, Lek E, et al. ePARCA-R: faculty of medicine. Imperial College London; 2022. Available: https://www.imperial.ac.uk/neonatal-data-analysis-unit/service-improvement-studies/eparca-r [Accessed 26 Oct 2022]. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

fetalneonatal-2023-325746supp001.pdf (267.4KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available. Study data are held in the National Neonatal Research Database (NNRD) by the Neonatal Data Analysis Unit (NDAU). Details of how to access the National Neonatal Research Database may be found at: https://www.imperial.ac.uk/neonatal-data-analysis-unit/neonatal-data-analysis-unit/utilising-the-nnrd/