Abstract

The transcription factor AP1 has been implicated in the induction of apoptosis in cells in response to stress factors and growth factor withdrawal. We report here that AP1 is necessary for the induction of apoptosis following hormone withdrawal in the erythropoietin (EPO)-dependent erythroid cell line HCD57. AP1 DNA binding activity increased upon withdrawal of HCD57 cells from EPO. A dominant negative AP1 mutant rendered these cells resistant to apoptosis induced by EPO withdrawal and blocked the downregulation of Bcl-XL. JunB is a major binding protein in the AP1 complex observed upon EPO withdrawal; JunB but not c-Jun was present in the AP1 complex 3 h after EPO withdrawal in HCD57 cells, with a concurrent increase in junB message and protein. Furthermore, analysis of AP1 DNA binding activity in an apoptosis-resistant subclone of HCD57 revealed a lack of induction in AP1 DNA binding activity and no change in junB mRNA levels upon EPO withdrawal. In addition, we determined that c-Jun and AP1 activities correlated with EPO-induced proliferation and/or protection from apoptosis. AP1 DNA binding activity increased over the first 3 h following EPO stimulation of HCD57 cells, and suppression of AP1 activity partially inhibited EPO-induced proliferation. c-Jun but not JunB was present in the AP1 complex 3 h after EPO addition. These results implicate AP1 in the regulation of proliferation and survival of erythroid cells and suggest that different AP1 factors may play distinct roles in both triggering apoptosis (JunB) and protecting erythroid cells from apoptosis (c-Jun).

Erythropoietin (EPO) is the glycoprotein hormone which is necessary for the development of immature erythroid cells (41). EPO promotes cell survival, stimulates proliferation, and appears to drive differentiation of immature erythroid cells. Colony-forming units–erythroid cells (CFU-Es), proerythroblasts, and a number of erythroid cell lines are absolutely dependent on EPO for their survival; withdrawal of these cells from EPO results in apoptosis, or programmed cell death (55). It is known that EPO acts on cells by binding to its receptor (EPOR), a member of the cytokine receptor superfamily. The binding of EPO to the EPOR activates the Janus kinase JAK2 (69) and results in phosphorylation and activation of the signal transducer and activator of transcription STAT5 (14, 18, 56, 67). A dominant negative form of JAK2 has been shown to inhibit not only EPO-dependent proliferation but also prevention of apoptosis, suggesting that this signal transduction pathway is essential for these effects (73, 74). In addition to JAK/STAT, EPO activates other signal transduction pathways such as the extracellular signal-related protein kinase pathway (ERK) (21, 46, 65) and other signal transduction molecules such as SHC/GRB-2 (17, 29, 33), CRK-1, Vav (45), phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (19, 30, 40), and the protein phosphatases SHP-1 (60) and SHP-2 (61). The role of these molecules in EPOR signaling is, however, unclear; truncated forms of the EPOR which are mitogenically active no longer activate these molecules (35). Therefore, the roles of other pathways in EPOR-dependent proliferation and prevention of apoptosis remain to be determined.

Recently the transcriptional activation complex activator protein 1 (AP1) has been implicated in the regulation of apoptosis (38). AP1 is comprised of members of the Jun (c-Jun [4], JunB [54], JunD [31]) and Fos (c-Fos [16], Fra-1 [15], Fra-2 [48], FosB [71]) families of phosphoproteins. Jun and Fos proteins dimerize via a series of leucine repeats (a leucine zipper) and bind in a sequence-specific manner to a heptad DNA sequence known as the 12-O-tetradecanoyl-13-phorbol acetate-responsive element (TRE) (5). Irradiation- and stress-induced apoptosis of tumor cells is thought to be triggered by signaling through the mitogen-activated protein kinase Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) (2, 13, 34, 66), which phosphorylates the transactivation domain of c-Jun and increases its transactivation potential. Recent evidence suggests that JNK activation is also involved in the induction of apoptosis observed when growth factors are removed from growth factor-dependent cells. Withdrawal of PC12 neuronal cells from nerve growth factor or epidermal growth factor or treatment of these cells with apoptosis-inducing agents induced JNK and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation within the first 6 h after withdrawal of growth factor (70). There is evidence, however, that JNK kinases may also play a role in mitogenic and growth factor signaling (7, 62) and that isoforms of JNK may protect small-cell lung carcinoma cells from UV-induced apoptosis (11). JNK is also known to be activated by growth factors such as epidermal growth factor (6) and transforming growth factor β (27), as well as a number of hematopoietic growth factors including EPO, thrombopoietin, interleukin-3, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, and stem cell factor (SCF) (24, 47). A definitive role for JNK in the induction of apoptosis, therefore, has yet to be determined.

Whereas the role of c-Jun in the regulation of cellular processes has been studied extensively, the role of other Jun and Fos family members in this process is not as clear. There is a growing amount of evidence that JunB may play a role distinct from that of c-Jun in the regulation of cell growth. junB expression is distinct from c-jun expression in many tissues (57) and during differentiation (25) and is stimulated independently of c-jun expression in response to a number of growth factors (1, 37). c-Jun can homodimerize and heterodimerize with other AP1 factors, whereas JunB can only heterodimerize (20); furthermore, c-Jun strongly transforms rat embryo fibroblasts and transactivates via the TRE from a variety of promoters (58), whereas JunB is weakly transforming and its transactivation potential is more promoter specific (32). These differences may be due to the fact that JunB is insensitive to phosphorylation by JNK (26, 36). Most interestingly, it has been determined that JunB is a potent inhibitor of c-Jun transactivation and cellular transformation, suggesting a unique role for JunB in the regulation of cell growth (20, 26). A clear role for JunB function in these processes, however, has yet to be determined.

In hematopoietic cells, apoptosis may be induced by growth factor withdrawal, treatment with glucocorticoids, viral gene activity, or irradiation (51). Primary erythroid progenitors purified from mice infected with the anemia-inducing strain of Friend virus (FVA cells) undergo apoptosis asynchronously in EPO-deprived cultures within the first 24 h (39). By contrast, the murine erythroleukemia cell line HCD57 first undergoes G1 cell cycle arrest following EPO withdrawal and then undergoes apoptosis within 48 to 72 h (59). Recently, Bcl-XL has been implicated as the primary repressor of apoptosis in HCD57 cells exposed to EPO, while Bcl-2 overexpression is unable to prevent apoptosis in these or in normal CFU-Es (42, 59). The upstream activators of the Bcl-XL gene are, however, unknown. Because HCD57 cells can be more easily manipulated than primary erythroid cells and may be transfected with dominant negative forms of genes, these cells are useful for studying the mechanisms that initiate apoptosis following EPO withdrawal. In addition, HCD57 cells that are arrested in the G1 phase of the cell cycle begin proliferation when exposed to EPO within the first 24 h. Thus, these cells are also models for the study of EPO’s action to stimulate proliferation and protect erythroid cells from apoptosis.

Our laboratory has used HCD57 cells to study the role of AP1 in the regulation of proliferation and apoptosis in erythroid cells. We show here that AP1 DNA binding activity was induced in both the proliferative and growth factor withdrawal states but that different AP1 factors were involved in the two processes. The introduction of a dominant negative AP1 mutant inhibited apoptosis when EPO was withdrawn and limited proliferation in EPO. Additionally, the downregulation of Bcl-XL normally exhibited in HCD57 cells deprived of EPO was inhibited in these dominant negative AP1-transfected cells. We also present evidence that JunB may play a role in the induction of apoptosis in these cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and Western blotting.

HCD57 and HCD57-SREI cells were cultured in Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium (Gibco-BRL)–25% fetal calf serum–10 μg of gentamicin/ml at 37°C in a 5% CO2 environment and maintained in 1 U of EPO/ml of medium. HCD57-TAM-67 cells were cultured as above with the addition of 50 μg of geneticin/ml of medium (Gibco-BRL). For each time point, 107 HCD57 cells were used. For EPO deprivation studies, the cells were washed three times in medium and incubated in the absence of EPO for 0, 1, 3, 6, and 24 h. For EPO-induced proliferation studies, cells were washed three times and incubated for 18 h in the above medium minus EPO. The cells were then treated for 0, 1, 3, 6, and 24 h with 1 U of EPO/ml. Nuclear extracts and total cell extracts were prepared as previously described (52), and 40 μg of protein was subjected to Western blot analysis with either anti-c-Jun (D), anti-JunB (N-17), or anti-Bcl-XL (L-19) antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Western-blotted proteins were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham). For the cell viability studies, cells were washed in medium as indicated above and cultured at 105 cells/ml in the absence of EPO or in the presence of 1 U of EPO/ml. Cell viability was determined by counting cells on a hemocytometer in the presence of 0.2% trypan blue.

Normal human colony-forming cells were purified in the laboratory of Amittha Wickrema, University of Illinois at Chicago. The human erythroid progenitors highly enriched for CFU-E were purified by the modification of a previously published method (68). Briefly, 300 to 400 ml of whole blood was separated over Ficoll-Hypaque (1.077 g/ml) to obtain mononuclear cells. Platelets were depleted by centrifugation over 10% bovine serum albumin followed by adherent cell depletion in polystyrene tissue culture flasks. The cell population was enriched for burst-forming units–erythroid (BFU-E) cells by negative selection with MACS antibody-coated paramagnetic microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Inc., Auburn, Calif.) consisting of CD3, CD11b, CD15, and CD45RA. The day 0 BFU-E cells were cultured for 6 days to obtain highly pure erythroid progenitors at the CFU-E stage of differentiation. The culture medium contained 15% fetal calf serum, 15% human serum, Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium, 500 U of penicillin/ml, 40 μg of streptomycin/ml, 10 ng of interleukin-3/ml, 2 U of EPO/ml, 50 U of insulin-like growth factor 1/ml, and 100 ng of SCF/ml. On day 6, the cells were separated over Ficoll-Hypaque and recultured in serum-free medium with 2 U of EPO/ml and 50 ng of insulin-like growth factor 1/ml until day 7. On day 7, 2 × 107 cells were washed three times to eliminate EPO. The cells were cultured in the same serum-free medium without EPO, and 107 cells were collected at 1 and 3 h after EPO withdrawal for gel shift analysis.

Northern blot analysis.

For RNA isolation, between 5 × 106 and 1 × 107 cells were harvested for each sample. Total RNA was isolated by using an RNeasy miniprep kit (Quiagen). Fifteen micrograms of RNA was separated on a 6.6% formaldehyde–1% agarose gel in 1× morpholinepropane sulfonic acid buffer. Equal loading of samples was determined by staining the gel in 1 μg of ethidium bromide/ml and visualization of rRNA with UV light. The RNA was transferred to PROTRAN nitrocellulose blotting membrane (Schleicher & Schuell) as described by Thomas (64). For Northern blot analysis, a 1.0-kb human junB cDNA fragment was labeled with [α-32P]dCTP by the random priming method (Stratagene). Filters were hybridized to the probes in 1× prehybridization buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate [pH 6.5], 0.1% bovine serum albumin, 0.1% Ficoll, 0.1% polyvinylpyrrolidone, 5× SSC [1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate], 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 250 μg of yeast RNA/ml, 50% formamide, 10% dextran sulfate). The blots were washed under high-stringency conditions and visualized with autoradiography for 3 days at −80°C. The junB message was quantitated with a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics).

Creation of the HCD57-TAM-67 cell line.

The dominant negative c-Jun mutant TAM-67, previously described (3), is comprised of amino acids 123 to 331 of c-Jun. TAM-67 was created as an EcoRI fragment and then cloned into the EcoRI site of the expression vector pMxMthneo. Plasmid DNA was prepared by standard techniques (Maxipreps; Promega). Twenty μg of DNA was transfected into HCD57 cells by using Lipofectamine reagent (Gibco-BRL), and transfected cells were selected by exposure to 400 μg of geneticin (Gibco-BRL)/ml for 3 weeks. Empty vector was also transfected as a negative control. The presence of the TAM-67 message was verified by Northern blot analysis, and protein expression was verified by Western blot analysis using an anti-c-Jun antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

AP1 DNA binding studies.

Nuclear extracts were prepared as indicated above and used in an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) (Stratagene). Ten micrograms of nuclear extract was incubated with a [γ-32P]ATP-labeled double-stranded DNA fragment corresponding to the TRE (sense strand, 5′-CTAGTGATGAGTCAGCCGGATC-3′) at 4°C in the presence or absence of 10× unlabeled TRE and subjected to electrophoresis at 25 mA for 2.5 h at 4°C on a 7% polyacrylamide gel. The gels were dried in vacuo for 1.5 h and exposed to X-ray film overnight at room temperature. Changes in AP1 DNA binding activity were measured with a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics).

Supershift assays.

The antibodies used in the supershift assays with the exception of the c-Jun-specific antibody were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. The c-Fos pan antibody (4-10G) recognizes amino acids 1 to 111 of c-Fos and cross-reacts with all other Fos proteins. All other antibodies (JunB [N-17], JunD [329], c-Fos [K-25], Fra-1 [N-17], Fra-2 [L-15], and FosB [102]) were raised to specific peptides of each AP1 protein and do not cross-react with other AP1 family members. For each sample (except for samples incubated overnight with or without EPO), 5 μg of nuclear extract was preincubated with 2 μg of antibody for 2 h at 4°C prior to incubation with the [γ-32P]ATP-labeled TRE for 5 min at room temperature and electrophoresis at 4°C as described above. Dried gels were exposed to X-ray film for 2 to 3 days at −80°C. The c-Jun-specific antibody (Ab-2; Oncogene Research) recognizes amino acids 73 to 87 of the c-Jun protein. This supershift was conducted as indicated above except that 10 μg of nuclear extract and 2 μg of antibody were used for samples incubated with or without EPO overnight. The dried gels were exposed to X-ray film overnight at −80°C (Fig. 1c) or 7 days at −80°C (Fig. 1d).

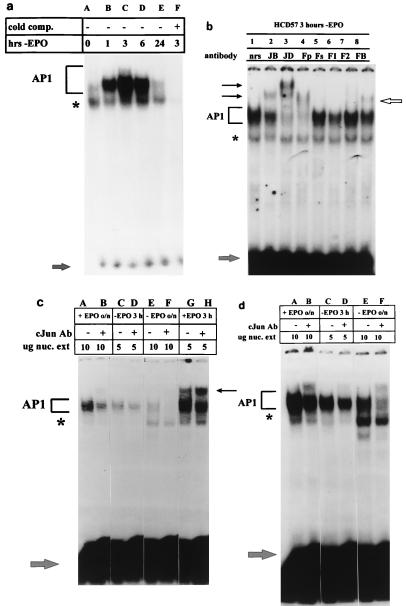

FIG. 1.

Withdrawal of EPO from HCD57 cells induces AP1 activity. For each panel, bracket indicates AP1 complex, lower arrow indicates unbound [γ-32P]ATP-labeled TRE, and asterisk indicates shifted band which is not completely competed by unlabeled TRE. Nuclear extracts were incubated with 106 cpm of labeled TRE in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 10-fold excess of unlabeled TRE (cold comp.). (a) EMSA of nuclear extracts incubated in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP-labeled TRE. Cells were washed three times in serum-free medium and incubated in EPO-free medium containing 25% fetal calf serum; 107 cells were harvested 0, 1, 3, 6, and 24 h after the withdrawal of EPO (hrs-EPO). (b) Supershift analysis of nuclear extracts from HCD57 cells deprived of EPO for 3 h and incubated with specific antibodies to the Fos and Jun family members. Upper arrows indicate the presence of JunB (lane 2), JunD (lane 3), and FosB (lane 8) in the AP1 complex. nrs, normal rabbit serum; JB, JunB; JD, JunD; Fp, Fos pan antibody; F1, Fra-1; F2, Fra-2; FB, FosB. (c and d) Supershift analysis of nuclear extracts (nuc. ext) from HCD57 cells cultured in the presence (+) or absence (−) of EPO overnight (o/n) or for 3 h and incubated with an antibody (Ab) specific for cJun. (c) Overnight exposure of the assay; (d) 10-day exposure of the same experiment. Upper arrow indicates presence of cJun in the AP1 complex 3 h following treatment with EPO (c, lane H) but not when the cells are deprived of EPO for 3 h (d, lane D). c-Jun is still present in the complex after overnight treatment with EPO (d, lane B). All lanes in panels c and d are normalized for approximately equal radioactivities shifted into the AP1 complex. Thus, while the radioactivities in lanes C and D and lanes G and H are comparable, the films for lanes A and B and lanes E and F were exposed seven times longer to compensate for very low AP1 binding.

In vitro kinase assay.

HCD57 cells were cultured in the presence of 0.2 U of EPO/ml. Anti-EPO antibody (R & D Systems) was added to the cells at a concentration of 1 μg/ml, and 107 cells were harvested 0, 1, 3, 6, and 24 h after addition of antibody; 500 μg of cell extracts was subjected to immunoprecipitation as previously described (52) with anti-JNK-1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Anti-JNK-1-immunoprecipitated proteins were concentrated into 25 μl of lysis buffer and subjected to an in vitro kinase assay as previously described (33), using 1 μg of glutathione S-transferase (GST)–Jun fusion protein as a substrate (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The substrate was visualized by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) on a 12% polyacrylamide gel, fixed and dried in vacuo, and visualized by exposure to X-ray film for 18 h at room temperature.

Apoptosis studies.

Cells were cultured at 105 cells/ml in the absence or in the presence of 1 U of EPO/ml. Cells were harvested at 24-h intervals, and genomic DNA was isolated from the cells (44). Ten micrograms of genomic DNA was resolved on a 2.25% agarose–1× Tris-acetate-EDTA–300 ng of ethidium bromide/ml gel. DNA laddering indicative of apoptosis was visualized with UV light.

RESULTS

Because of the growing evidence that AP1 activation may play an important role in the induction of apoptosis in hematopoietic cells, we studied the effects of EPO withdrawal on AP1 DNA binding in HCD57 cells. An EMSA of nuclear extracts prepared from cells deprived of EPO over a 24-h period revealed that AP1 DNA binding activity increased within 1 h following EPO deprivation and peaked at 3 h following treatment (Fig. 1a, lanes B and C, bracket). In all of our EMSAs, we also detected a minor gel shift band which was not fully competed for DNA binding by unlabeled TRE (Fig. 1a, asterisk). DNA binding to the TRE increased sevenfold or more before returning to background levels 24 h after initial treatment. A similar increase in AP1 activity was detected when the cells were treated with an anti-EPO antibody, and washing the cells in the presence of EPO did not result in an increase in AP1 activity, suggesting that the increase in AP1 activity is not an artifact of cell manipulation (data not shown). Supershift analysis using antibodies specific to all known Fos and Jun family members revealed that only select AP1 factors were bound to the TRE DNA under conditions of EPO withdrawal (Fig. 1b to d). When the cells were deprived of EPO for 3 hours, JunB, JunD, and FosB were present in the AP1 complex (Fig. 1b, lanes 2, 3, and 8); c-Jun was not present at this time (Fig. 1c and d, lanes D). Overexposure of the overnight no-EPO supershift showed the presence of c-Jun (Fig. 1c, lane F); this result may reflect the steady-state levels of c-Jun protein in the cells. Further supershifts using nuclear extracts from HCD57 cells incubated overnight in the presence or absence of EPO revealed that JunD and FosB were present in the AP1 complex at all times (data not shown).

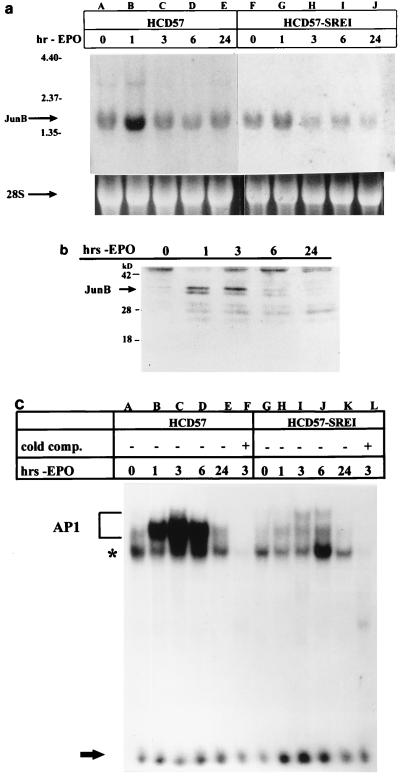

The above result implicated JunB as an important factor in the induction of apoptosis and led us to further examine its expression in these cells during the early events after EPO withdrawal. Northern blot analysis of total RNA isolated from cells deprived of EPO over 24 h revealed that junB mRNA expression increased threefold or more 1 h following EPO withdrawal (Fig. 2a, lane B). Treatment of HCD57 cells with the transcriptional inhibitor actinomycin D prior to EPO withdrawal revealed the same mRNA turnover rate for EPO-deprived cells as for cells cultured in EPO (approximately 60 min) (data not shown). Therefore, the increase in junB mRNA levels following EPO withdrawal was likely due to increased transcription as opposed to an increase in mRNA stability. Western blot analysis of nuclear extracts of HCD57 cells deprived of EPO revealed that JunB protein in the nucleus increased dramatically over the first 3 h after EPO was withdrawn from the cells (Fig. 2b). To investigate whether junB upregulation was necessary for the induction of apoptosis in these cells, we used an EPO-independent subclone of HCD57 cells recently isolated in this laboratory. In the absence of EPO, this subclone can slowly proliferate and does not undergo apoptosis. We have named these cells HCD57-SREI (SCF responsive, EPO independent) because they proliferate at an increased rate in response to SCF or EPO but do not require EPO for survival. HCD57-SREI cells appear to have a mutation responsible for EPO-independent proliferation and survival other than autocrine production of EPO or an autoactivation of the EPOR. HCD57-SREI cells have STAT5 constitutive activity outside of EPOR/JAK2 signaling, which may explain the EPO-independent phenotype (unpublished data). An examination of the junB mRNA levels in HCD57-SREI cells deprived of EPO revealed a lower induction of junB (Fig. 2a, lane G) compared to the same time point in HCD57 cells (Fig. 2a, lane B). This lower level of junB message corresponded to a greatly reduced level of AP1 DNA binding activity in HCD57-SREI cells during the induction of apoptosis (Fig. 2c, lanes H to J) compared to HCD57 cells (Fig. 2c, lanes B to D). A loss of junB upregulation therefore correlated with a loss of the induction of apoptosis in these EPO-independent HCD57-SREI cells.

FIG. 2.

JunB mRNA and protein expression in EPO-deprived cells. (a) Northern blot analysis of junB expression in HCD57 and HCD57-SREI cells upon EPO withdrawal. Upper arrow indicates position of junB message; lower arrow indicates 28S rRNA to show equal loading of samples. Positions of migration of 4.4-, 2.37-, and 1.35-kb molecular size markers are indicated at the left. (b) Western blot analysis of 40 μg of nuclear extracts from HCD57 cells deprived of EPO for 0, 1, 3, 6, and 24 h (hrs-EPO) probed with an anti-JunB antibody. Arrow indicates presence of JunB protein 1 and 3 h after EPO deprivation. (c) EMSA of HCD57 (lanes A to F) and HCD57-SREI (lanes G to L) cells deprived of EPO and incubated in the presence (+) or absence (−) of unlabeled TRE. AP1 complex, noncompeting complex, and unbound [γ-32P]ATP-labeled TRE are labeled as indicated for Fig. 1. Protein isolation and EMSA were conducted as indicated for Fig. 1a. A loss in AP1 activity in HCD57-SREI cells is observed (lanes H to J) compared to that in HCD57 cells (lanes B to D).

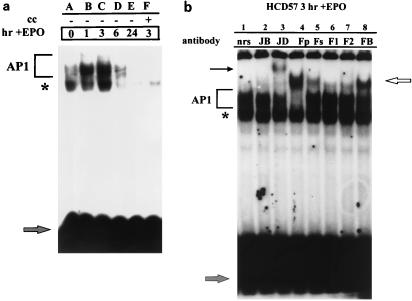

We next addressed the role of AP1 in EPO-induced proliferation and survival. When HCD57 cells were deprived of EPO for 18 h and then stimulated with EPO, an increase in AP1 activity was induced 1 h following EPO stimulation, which peaked at 3 h (Fig. 3a, lanes B and C). No difference in AP1 activity was detected between HCD57 and HCD57-SREI cells stimulated with EPO (data not shown). Supershift analysis of nuclear extracts harvested 3 h following EPO stimulation revealed that c-Jun (Fig. 1c, lane H) and JunD (Fig. 3b, lane 3), as well as all known Fos-related proteins (c-Fos, Fra-1, Fra-2, and FosB) (Fig. 3b, lanes 4 to 8), were detected in the AP1 complex 3 h after EPO addition. Overexposure of the c-Jun supershifts using nuclear extracts from cells incubated overnight in the presence of EPO revealed that c-Jun was still present in the complex 24 h after stimulation with EPO (Fig. 1d, lane B).

FIG. 3.

Stimulation of EPO-induced proliferation of HCD57 cells is accompanied by a rapid increase in AP1 activity. AP1 complex, noncompeting complex, and unbound [γ-32P]ATP-labeled TRE are labeled as indicated for Fig. 1. (a) EMSA of nuclear extracts isolated from HCD57 cells which have been deprived of EPO for 18 h and then stimulated with EPO for 0, 1, 3, 6, and 24 h. An increase in AP1 activity is observed over the first 3 h following treatment with EPO (lanes B to D). cc, cold competitor. (b) Supershift analysis of nuclear extracts isolated from HCD57 cells cultured in EPO for 3 h, using the Jun and Fos antibodies indicated in Fig. 1b. Arrows indicate the presence of all Fos family members (upper right arrow) and JunD (upper left arrow) in the AP1 complex.

If the AP1 DNA binding activity observed in HCD57 cells corresponded to a biological function of AP1 in these cells, inhibition of this activity should effect cell proliferation and the induction of apoptosis. To test this theory, the dominant negative AP1 mutant TAM-67 was stably transfected into HCD57 cells. This deletion mutant, which lacks the sequence encoding the transactivation domain of c-Jun but retains the DNA binding and leucine zipper sequences, has been shown to inhibit both c-jun-induced transactivation and oncogenic transformation when stably transfected into cells (9, 12, 22). TAM-67 inhibits AP1 activity by the formation of inactive heterodimers with Fos and Jun proteins which can bind DNA but cannot activate transcription (10).

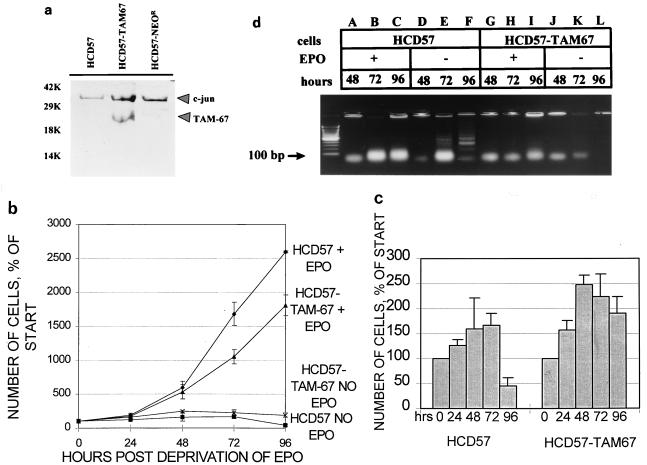

Western blot analysis of cells selected for the presence of the neomycin resistance marker revealed the presence of TAM-67 protein in a pool of neomycin-resistant cells (Fig. 4A, center lane). The AP1 DNA binding activity of these cells, termed HCD57-TAM-67 cells, was tested under EPO stimulation and EPO withdrawal conditions to determine if the DNA binding patterns were different between the transfected and parental cell lines. The DNA binding activity was similar between the parental and transfected cell lines both when the cells were stimulated to proliferate with EPO and when EPO was withdrawn from the cells (data not shown). A TAM-67-specific gel shift was not detected in the transfected cell line; this result was consistent with other stable cell lines containing TAM-67 (22). The presence of TAM-67 also had no effect on the induction of junB mRNA during EPO withdrawal (data not shown). An examination of the growth properties of HCD57-TAM-67 cells in comparison to the parental cell line revealed that the HCD57-TAM-67 cells proliferated more slowly in response to EPO (Fig. 4b) than HCD57 cells. When cultured in the absence of EPO, HCD57 cell viability decreased, whereas the HCD57-TAM-67 cells remained viable at 96 h after EPO withdrawal (Fig. 4c). HCD57-TAM-67 cells are still dependent on EPO for proliferation such that no proliferation is seen in the absence of EPO even though cell viability is maintained. Numerous attempts to obtain high-expressing single-cell clones of this polyclonal cell line resulted in cells with a highly unstable TAM-67 phenotype. These single-cell clones showed inhibited EPO-induced proliferation and increased viability in the absence of EPO, but the TAM-67 phenotype was lost with continuous passage of the cell lines, presumably due to selective pressures against a slowly proliferating cell line.

FIG. 4.

The presence of a dominant negative AP1 mutant blocks apoptosis in HCD57 cells. (A) Western blot analysis of 40 μg of nuclear protein from HCD57, HCD57-TAM-67, and HCD57 cells transfected with vector alone (HCD57-NEOR), using an anti-c-Jun antibody. Upper and lower arrows indicate the presence of the c-Jun and TAM-67 proteins, respectively. (b and c) Growth and survival properties of HCD57 and HCD57-TAM-67 cells exposed to EPO. (b) Proliferative response of HCD57 and HCD57-TAM-67 cells to EPO. Cells were cultured in the absence or presence of 1 U of EPO/ml. Data are indicated as percentages of the starting number of cells. ⧫, HCD57 cells cultured in EPO; ▴, HCD57-TAM-67 cells cultured in EPO; ▪, HCD57 cells cultured in the absence of EPO; ×, HCD57-TAM-67 cells cultured in the absence of EPO for 0, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h. Data are indicated as percentages of the starting number of cells. (d) Prevention of apoptosis by TAM-67 in HCD57 cells. Cells were cultured in the presence of EPO (lanes A to C and G to I) or in the absence of cytokine (lanes D to F and J to L) for the number of hours indicated. Ten micrograms of genomic DNA from HCD57 (lanes A to F) and HCD57-TAM-67 (lanes G to L) cells was resolved on a 2.25% agarose gel. Arrow indicates 100-bp marker.

The maintenance of viable HCD57-TAM-67 cells 96 h after withdrawal of EPO indicated that apoptosis was likely inhibited in these cells. To test this hypothesis, genomic DNA was isolated from HCD57 and HCD57-TAM-67 cells cultured in the presence or absence of EPO over 96 h. Agarose gel electrophoresis of this DNA revealed that whereas HCD57 cells exhibited the characteristic DNA laddering indicative of apoptosis 72 and 96 h following withdrawal of EPO (Fig. 4d, lanes E and F), HCD57-TAM-67 cells show no such DNA degradation, suggesting that apoptosis was inhibited in these cells (Fig. 4d, lanes K and L). To further confirm that the HCD57-TAM-67 cells escaped apoptosis, EPO was readded to cultures of both HCD57 and HCD57-TAM-67 cells which had been deprived of EPO for 96 h. By 120 h, the HCD57-TAM-67 cells doubled and began exponential proliferation whereas the HCD57 cells were incapable of proliferation (data not shown). The dramatic effect of the presence of the AP1 inhibitor on the rate of proliferation and evidence of apoptosis suggests that AP1 may play a central role in the regulation of EPO-dependent growth and survival in these erythroleukemia cells.

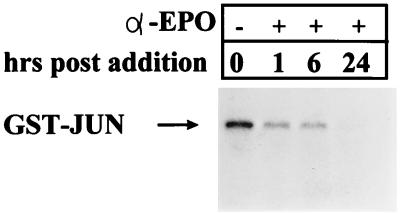

In a number of recent articles, AP1 activation has been linked to the induction of apoptosis via activation by JNK (13, 43, 49, 70). To determine if JNK was activated by EPO withdrawal from HCD57 cells, anti-JNK immunoprecipitates from HCD57 cells deprived of EPO for up to 24 h were tested in an in vitro kinase assay. Autoradiography of GST-JUN proteins incubated with anti-JNK immunoprecipitates showed that JNK activity was detected in the presence of EPO but decreased 1 h following EPO withdrawal and was undetectable 24 h following EPO deprivation (Fig. 5). Washing the cells to deprive them of EPO caused a more rapid decrease in JNK levels; JNK was undetectable 1 h following washout of EPO, and p38 activity was not detected in these cells (data not shown). A shorter time course testing JNK activity within the first hour following anti-EPO treatment showed no transitory increase in JNK activity (data not shown). JNK activation, therefore, does not appear to play a role in the induction of apoptosis in these cells.

FIG. 5.

JNK levels decrease following EPO withdrawal from HCD57 cells. An in vitro kinase assay of JNK activity in HCD57 cells cultured in the presence of an anti-EPO antibody for the hours indicated was done. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with an anti-JNK antibody and tested for the ability to phosphorylate a GST-Jun fusion protein. Phosphorylated proteins were resolved on an SDS–12% polyacrylamide gel. Arrow indicates position of the [γ-32P]ATP-labeled GST-Jun fusion protein.

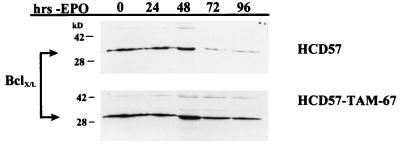

The antiapoptotic protein Bcl-XL has been implicated in the prevention of apoptosis in HCD57 cells (59); expression of this protein decreases 72 h following EPO withdrawal (59) (Fig. 6). However, the upstream activators of this protein are unknown. To determine if inhibition of AP1 activity influences the downregulation of Bcl-XL, the expression of this protein was assessed in HCD57-TAM-67 cells during apoptotic progression. Western blot analysis of cells deprived of EPO revealed that Bcl-XL expression decreased 72 h following EPO withdrawal in HCD57 cells; in contrast, Bcl-XL expression remained stable in HCD57-TAM-67 cells for up to 96 h (Fig. 6). It appears, therefore, that inhibition of AP1 activity may contribute to maintenance of Bcl-XL levels in HCD57 cells.

FIG. 6.

Bcl-XL levels are maintained in EPO-deprived HCD57-TAM-67 cells. Total cellular proteins were isolated from HCD57 and HCD57-TAM-67 cells and were subjected to Western blot analysis with an anti-Bcl-XL antibody. Positions of molecular weight markers are indicated at the left. Arrows indicate the presence of the Bcl-XL protein. Bcl-XL levels decreased 72 h following EPO withdrawal in HCD57 cells (top) but were unchanged in HCD57-TAM-67 cells deprived of EPO for 96 h (bottom).

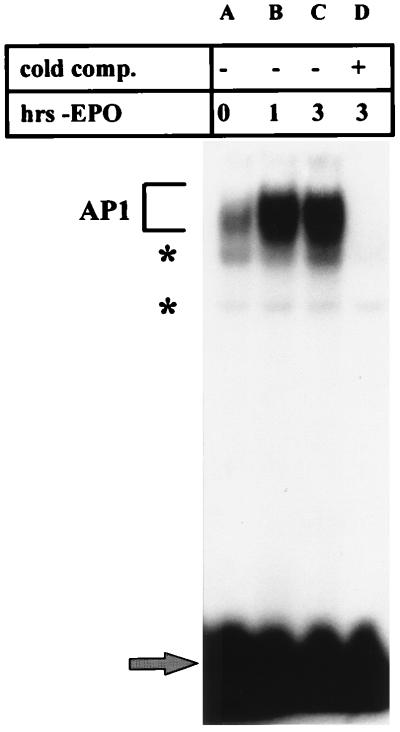

HCD57 cells differ from primary mouse and human immature erythroid cells (CFU-Es) in that primary cells do not undergo cell cycle arrest but exhibit clear DNA degradation within 2 to 6 h after EPO is withdrawn, as indicated by genomic DNA degradation (42). To test if the increase in AP1 binding activity following EPO withdrawal in HCD57 cells was associated with the initiation of apoptosis in cells which did not undergo cell cycle arrest, the AP1 DNA binding activity was tested in normal human colony-forming cells during the early stages of EPO withdrawal. A dramatic increase in AP1 activity was detected during the first 3 h following EPO withdrawal in these cells (Fig. 7, lanes B and C). Therefore, AP1 is strongly induced simultaneously with the first signs of cell death in these normal erythroid cells and seems unrelated to the cell cycle arrest which occurs in HCD57 cells.

FIG. 7.

Normal human erythroid cells demonstrate an increase in AP1 activity when deprived of EPO. AP1 complex, noncompeting complex, and unbound [γ-32P]ATP-labeled TRE are labeled as indicated for Fig. 1. Nuclear extracts from a culture highly enriched for CFU-Es cultured in the presence of EPO (lane A) or deprived of EPO for 1 and 3 h (lanes B and C) were incubated in the presence of a [γ-32P]ATP-labeled TRE as indicated in Fig. 1 and in the presence (+) or absence (−) of unlabeled TRE. An increase in AP1 activity is observed 1 and 3 h after withdrawal of EPO (lanes B and C).

DISCUSSION

AP1 has long been identified as an immediate-early activator of transcription important in proliferation and cellular transformation. Recently, this transcription factor has also been implicated in the induction of apoptosis. The data vary, however, with respect to the importance of the c-Jun and c-Fos proteins in the induction of apoptosis. In a number of studies, c-Jun activation has been detected in cells induced to undergo apoptosis (8, 63, 72). In other studies, c-Jun and c-Fos expression has been shown to be completely unnecessary for apoptotic cell death to occur (28, 53). The conflicting data suggest that while c-Jun may contribute to the initiation of apoptosis in some systems, other AP1 factors may be involved in other systems. Our results indicate a central role for AP1 in the proliferation and survival of HCD57 cells, but we propose a new model for this role involving different Fos and Jun family members. We believe that AP1 is critical for the induction of apoptosis in HCD57 cells and that JunB is important for this induction, based on a number of results. Withdrawal of EPO from HCD57 cells induced at least a sevenfold increase in AP1 DNA binding activity. In all of our EMSAs, we detected a minor gel shift band which was only partially competed for by the unlabeled TRE (Fig. 1a and 3a, asterisks) and was not supershifted by any antibodies (Fig. 1b to d and 3c, asterisks); we do not know the nature of this complex. The introduction of a dominant negative AP1 mutant into these cells to block AP1 activity rendered them resistant to apoptosis induced by EPO withdrawal. Furthermore, this dominant negative mutant also blocked the downregulation of Bcl-XL protein levels following EPO withdrawal. We also observed an increase in AP1 activity upon EPO withdrawal in colony-forming cells derived from normal humans which paralleled the increase in activity observed in HCD57 cells. In testing for the activation of c-Jun, however, we discovered that JNK activation was not detected in these cells upon EPO withdrawal. Supershift analysis of the AP1 complex showed that JunB was present when EPO was withdrawn but c-Jun was not present. The presence of JunB in the AP1 complex following EPO withdrawal is consistent with the appearance of both junB mRNA and protein immediately following EPO deprivation. Furthermore, no junB mRNA upregulation was detected upon EPO withdrawal in the apoptosis-resistant subclone HCD57-SREI, which correlated with a lack of induction of AP1 activity. Based on these results, we believe that JunB and not c-Jun may be the important AP1 factor involved in the induction of apoptosis in HCD57 cells.

We also studied the role of AP1 in EPO-induced proliferation. We determined that stimulation of proliferation by EPO is accompanied by an immediate increase in AP1 activity. This result is consistent with a previously published report which showed an EPO-induced increase in AP1 DNA binding activity in a cell line which did not require EPO for proliferation (50). Inhibition of this activity by the dominant negative mutant partially inhibited proliferation of these cells. Supershift analysis of the AP1 complex revealed that c-Jun, JunD, c-Fos, Fra-1, Fra-2, and FosB were present in the complex. Further supershifts following long-term culture of cells in the presence or absence of EPO revealed that JunD and FosB were present in the AP1 complex at all times (data not shown). HCD57-SREI cells responded to EPO similarly to HCD57 cells. We did not detect any EPO-independent AP1 in HCD57-SREI cells; this observation suggests that while AP1 activity may not be sufficient for EPO-independent proliferation, it may still be required for the full proliferative potential. This hypothesis is supported by the proliferative capability of the HCD57-TAM-67 cell line, in which the presence of the AP1 inhibitor created a viable cell line that proliferated at a lower rate than the parental line. Therefore, c-Jun, c-Fos, Fra-1, and Fra-2 activities correlated with proliferation and/or prevention of apoptosis whereas JunB activity correlated with induction of apoptosis or cell cycle arrest. Moreover, we detected an increase in JNK activity upon EPO stimulation similar to that observed previously in erythroid cells (47) (data not shown). Therefore, activation of c-Jun and the Fos proteins may be the important AP1 factors involved in EPO-induced proliferation.

Our data are consistent with those of other laboratories which observed that blocking AP1 activity with the dominant negative mutant TAM-67 blocked apoptosis in growth factor-deprived PC12 cells or in breast carcinoma MCF-7 cells induced to undergo apoptosis with vitamin E succinate (70, 72). Therefore, there is a common observation that an active process acts through AP1 to initiate apoptosis. In the above-mentioned studies, however, activation of c-Jun and/or JNK appeared to be the pivotal event in initiating apoptosis. In the present study, we observed neither JNK activation nor an increase in c-Jun protein levels in the 24 h following EPO withdrawal (Fig. 5 and data not shown). Instead, we detected the presence of JunB in the AP1 complex. We do not believe that the increase in AP1 activity is an artifact of cellular stress, since the increase was also seen when the cells were deprived of EPO with anti-EPO antibodies but not when the cells were washed in the presence of EPO. The increase in AP1 activity corresponds to an increase in junB mRNA and protein levels. junB mRNA upregulation was not detected in the apoptosis-resistant HCD57-SREI cells deprived of EPO, suggesting that cellular stress from washing was not increasing AP1 activity in these cells. Therefore, it appears that a process involving AP1 is occurring to initiate apoptosis in HCD57 cells which must be distinct from those seen in PC12 or MCF-7 cells. Increases in junB mRNA expression have been detected in thymic cells undergoing radiation-, topoisomerase-, or glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis (63). The upregulation of junB mRNA and protein suggests that increased levels of JunB may contribute to the initiation of apoptosis. This raises some interesting speculation as to the role of JunB in the regulation of apoptosis. JunB, when dimerized with other Jun and Fos proteins, is capable of promoter-specific transactivation and transrepression (32). JunB is also capable of dimerizing with other transcription factors such as members of the ATF family of transcription factors (23). Therefore, JunB may dimerize with FosB or other proteins and activate genes which are required for the induction of apoptosis (or repress genes which prevent apoptosis). It is also possible that JunB functions in these cells to inhibit c-Jun activity; the concurrent upregulation of junB mRNA and protein and the downregulation of JNK activity may function to suppress c-Jun transactivation capacity. This would be the first instance of a biological function for the inhibition of c-Jun activity by JunB. If this were the case, however, one would expect TAM-67, another inhibitor of c-Jun activity, to induce apoptosis. The inhibition of apoptosis by TAM-67 suggests another role for JunB in this process. The biological effect of TAM-67 on JunB function has not yet been determined. However, it is known that TAM-67 inhibits c-jun-induced transactivation and oncogenic transformation by forming inactive heterodimers with c-Jun and c-Fos which can bind DNA but cannot transactivate via the TRE (10). TAM-67 likely inhibits JunB function in a similar fashion. JunB may serve a dual function by inhibiting c-Jun activity and activating apoptotic genes; in this event, TAM-67 would inhibit the induction of apoptosis. Further studies are needed to test these hypotheses.

An important question remains, however, as to how an increase in AP1 activity 3 h after EPO withdrawal may induce apoptotic (or inhibit antiapoptotic) events when the DNA laddering indicative of apoptosis begins 24 to 48 h after EPO withdrawal. The increase in AP1 activity observed in human primary colony-forming cells, which undergo apoptosis asynchronously within 2 to 6 h of EPO withdrawal, suggests that the increase in AP1 activity is related to the induction of apoptosis rather than to the cell cycle arrest which also occurs in HCD57 cells deprived of EPO. Therefore, JunB activation may be an early response to EPO withdrawal which is necessary for the induction of apoptosis regardless of the mitotic state of the cell. Recently, we have discovered that the molecular events triggered by the withdrawal of EPO for 24 h are not totally reversible by EPO. DNA cleavage indicative of apoptosis was observed in HCD57 cells cultured in EPO for 72 h after a 24-h window of EPO withdrawal (unpublished results). Therefore, the induction of junB during the 6 h following EPO removal may trigger events leading to apoptosis many hours later. In this regard, the erythroleukemic HCD57 cells may also differ from primary cells. Further evidence that this initial increase in AP1 activity is necessary for the induction of apoptosis is observed in the EPO-independent subclone HCD57-SREI, which exhibited a dramatic loss of induction of AP1 DNA binding following EPO withdrawal and a loss of junB mRNA upregulation. What changes occur in HCD57-SREI to affect junB transcription are not known.

Inhibition of AP1 activity also inhibited the downregulation of Bcl-XL, which has been shown to be critical for the induction of apoptosis in these cells (59). Overexpression of Bcl-2 does not prevent apoptosis in HCD57 cells or in normal CFU-Es (42, 59). The HCD57-TAM-67 phenotype is similar to that of ectopically expressed Bcl-XL (59); the cells stopped proliferating but remained viable in the absence of EPO (Fig. 4c). In HCD57-SREI cells, where JunB is not upregulated by EPO deprivation, Bcl-XL expression is not downregulated (unpublished data). Therefore, a link may exist between the activation of JunB and the downregulation of Bcl-XL.

Taken together, these data suggest that different AP1 family members may play opposing roles in the regulation of apoptosis. We therefore propose a model in which c-Jun and JunB activities contribute to the destiny of HCD57 cells. When these cells are stimulated with EPO, c-Jun DNA binding activity and JNK activity increase to promote proliferation and/or the prevention of apoptosis. Removal of EPO from the system results in a downregulation of JNK activity and a concurrent upregulation of junB expression, which may activate apoptosis-inducing genes or suppress antiapoptotic genes. Therefore, the expression and activity of different AP1 family members may determine the fate of growth factor-dependent cells.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01DK39781.

We thank Zhenhong Sun for technical assistance in the Western blot experiments. We also thank Amy Lawson and Haifeng Bao for helpful discussion in the interpretation of the data.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adachi K, Saito H. Induction of junB expression, but not c-jun, by granulocyte colony-stimulating factor or macrophage colony-stimulating factor in the proliferative response of human myeloid leukemia cells. J Clin Invest. 1992;89:1657–1661. doi: 10.1172/JCI115763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adler V, Fuchs S Y, Kim J, Kraft A, King M P, Pelling J, Ronai Z. Jun-NH2-terminal kinase activation mediated by UV-induced DNA lesions in melanoma and fibroblast cells. Cell Growth Differ. 1995;6:1437–1446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alani R, Brown P H, Binetruy B, Dosaka H, Rosenberg R K, Angel P, Karin M, Birrer M J. The transactivating function of the c-Jun proto-oncoprotein is required for cotransformation of rat embryo cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:6286–6295. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.12.6286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Angel P, Allegretto E A, Okino S T, Hattori K, Boyle W J, Hunter T, Karin M. Oncogene jun encodes a sequence-specific trans-activator similar to AP-1. Nature. 1988;332:166–171. doi: 10.1038/332166a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Angel P, Imagawa M, Chiu R, Stein B, Imbra R J, Rahmsdorf H J, Jonat C, Herrlich P, Karin M. Phorbolester-inducible genes contain a common cis-element recognized by the TPA-modulated trans-acting factor. Cell. 1987;49:729–739. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90611-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Assefa Z, Garmyn M, Bouillon R, Merlevede W, Vandenheede J R, Agostinis P. Differential stimulation of ERK and JNK activities by ultraviolet B irradiation and epidermal growth factor in human keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 1997;108:886–891. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12292595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Atfi A, Djelloul S, Chastre E, Davis R R, Gespach C. Evidence for a role of Rho-like GTPases and stress-activated protein kinase/c-Jun N-terminal kinase (SAPK/JNK) in transforming growth factor β-mediated signaling. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:1429–1432. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.3.1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bossy-Wetzel E, Bakiri L, Yaniv M. Induction of apoptosis by the transcription factor c-Jun. EMBO J. 1997;16:1695–1709. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.7.1695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown P H, Alani R, Preis L H, Szabo E, Birrer M J. Suppression of oncogene-induced transformation by a deletion mutant of c-jun. Oncogene. 1993;8:877–886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown P H, Chen T K, Birrer M J. Mechanism of action of a dominant-negative mutant of c-Jun. Oncogene. 1994;9:791–799. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Butterfield L, Storey B, Maas L, Heasley L E. c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase regulation of the apoptotic response of small cell lung cancer cells to ultraviolet radiation. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:10110–10116. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.15.10110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen T K, Smith L M, Gebhardt D K, Birrer M J, Brown P H. Activation and inhibition of the AP-1 complex in human breast cancer cells. Mol Carcinog. 1996;15:215–226. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2744(199603)15:3<215::AID-MC7>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen Y R, Meyer C F, Tan T H. Persistent activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase 1 (JNK1) in gamma radiation-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:631–634. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.2.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chin H, Nakamura N, Kamiyama R, Miyasaka N, Ihle J N, Miura O. Physical and functional interactions between Stat5 and the tyrosine-phosphorylated receptors for erythropoietin and interleukin-3. Blood. 1996;88:4415–4425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen D R, Curran T. fra-1: a serum-inducible, cellular immediate-early gene that encodes a Fos-related antigen. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:2063–2069. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.5.2063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Curran T, Teich N M. Candidate product of the FBJ murine osteosarcoma virus oncogene: characterization of a 55,000-dalton phosphoprotein. J Virol. 1982;42:114–122. doi: 10.1128/jvi.42.1.114-122.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Damen J E, Liu L, Cutler R L, Krystal G. Erythropoietin stimulates the tyrosine phosphorylation of Shc and its association with Grb2 and a 145-Kd tyrosine phosphorylated protein. Blood. 1993;82:2296–2303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Damen J E, Mui A L, Puil J L, Pawson T, Krystal G. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase associates, via its Src homology 2 domains, with the activated erythropoietin receptor. Blood. 1993;81:3204–3210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Damen J E, Wakao H, Miyajima A, Krosl J, Humphries R K, Cutler R L, Krystal G. Tyrosine 343 in the erythropoietin receptor positively regulates erythropoietin-induced cell proliferation and Stat5 activation. EMBO J. 1995;14:5557–5568. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00243.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deng T, Karin M. JunB differs from c-Jun in its DNA-binding and dimerization domains, and represses c-Jun by formation of inactive heterodimers. Genes Dev. 1993;7:479–490. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.3.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Devemy E, Billat C, Haye B. Activation of raf-1 and mitogen-activated protein kinases by erythropoietin and inositolphosphate-glycan in normal erythroid progenitor cells: involvement of protein kinase C. Cell Signalling. 1997;9:41–46. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(96)00095-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Domann F E, Levy J P, Birrer M J, Bowden G T. Stable expression of a c-JUN deletion mutant in two malignant mouse epidermal cell lines blocks tumor formation in nude mice. Cell Growth Differ. 1994;5:9–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dorsey M J, Tae H J, Sollenberger K G, Mascarenhas N T, Johansen L M, Taparowsky E J. B-ATF: a novel human bZIP protein that associates with members of the AP-1 transcription factor family. Oncogene. 1995;11:2255–2265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Foltz I N, Schrader J W. Activation of the stress-activated protein kinases by multiple hematopoietic growth factors with the exception of interleukin-4. Blood. 1997;89:3092–3096. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Francastel C, Groisman R, Pfarr C M, Robert-Lezenes J. Antisense c-jun overcomes a differentiation block in a murine erythroleukemia cell line. Oncogene. 1994;9:1957–1964. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Franklin C C, Sanchez V, Wagner F, Woodgett J R, Kraft A S. Phorbol ester-induced amino-terminal phosphorylation of human JUN but not JUNB regulates transcriptional activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:7247–7251. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.15.7247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frey R S, Mulder K M. TGFbeta regulation of mitogen-activated protein kinases in human breast cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 1997;117:41–50. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(97)00211-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gajate C, Alonso M T, Schimmang T, Mollinedo F. C-Fos is not essential for apoptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;218:267–272. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.He T C, Jiang N, Zhuang H, Wojchowski D M. Erythropoietin-induced recruitment of Shc via a receptor phosphotyrosine-independent, Jak2-associated pathway. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:11055–11061. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.19.11055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.He T C, Zhuang H, Quelle D E, Wojchowski D M. Association of the p85 regulatory subunit of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase with an essential erythropoietin receptor subdomain. Blood. 1993;82:3530–3538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hirai S I, Ryseck R P, Mechta F, Bravo R, Yaniv M. Characterization of Jun D: a new member of the jun oncogene family. EMBO J. 1989;8:1433–1439. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03525.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hsu J C, Cressman D E, Taub R. Promoter-specific trans-activation and inhibition mediated by JunB. Cancer Res. 1993;53:3789–3794. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jacobs-Helber S M, Penta K, Sun Z H, Lawson A, Sawyer S T. Distinct signaling from stem cell factor and erythropoietin in HCD57 cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:6850–6853. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.11.6850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson N L, Gardner A M, Diener K M, Lange-Carter C A, Gleavy J, Jarpe M B, Minden A, Karin M, Zon L I, Johnson G L. Signal transduction pathways regulated by mitogen-activated/extracellular response kinase kinase kinase induce cell death. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:3229–3237. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.6.3229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Joneja B, Wojchowski D M. Mitogenic signaling and inhibition of apoptosis via the erythropoietin receptor box-1 domain. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:11176–11184. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.17.11176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kallunki T, Deng T, Hibi M, Karin M. c-Jun can recruit JNK to phosphorylate dimerization partners via specific docking interactions. Cell. 1996;87:929–939. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81999-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kang L Y, Yang Y C. Activation of junB and c-myc primary response genes by interleukin 9 in a human factor-dependent cell line. J Cell Physiol. 1995;163:623–630. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041630324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karin M, Liu Z G, Zandi E. AP-1 function and regulation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:240–246. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80068-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kelley L L, Koury M J, Bondurant M C, Koury S T, Sawyer S T, Wickrema A. Survival or death of individual proerythroblasts results from differing erythropoietin sensitivities: a mechanism for controlled rates of erythrocyte production. Blood. 1993;82:2340–2352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klingmüller U, Wu H, Hsiao J G, Toker A, Duckworth B C, Cantley L C, Lodish H F. Identification of a novel pathway important for proliferation and differentiation of primary erythroid progenitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3016–3021. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koury M J, Bondurant M C. The molecular mechanism of erythropoietin action. Eur J Biochem. 1992;210:649–663. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb17466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lacronique V, Varlet P, Mayeux P, Porteau A, Gisselbrecht S, Kahn A, Lacombe C. Bcl-2 targeted overexpression into the erythroid lineage of transgenic mice delays but does not prevent the apoptosis of erythropoietin-deprived erythroid progenitors. Blood. 1997;90:3050–3056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Latinis K M, Koretzky G A. Fas ligation induces apoptosis and Jun kinase activation independently of CD45 and Lck in human T cells. Blood. 1996;87:871–875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maniatis T, Fritsch E F, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miura O, Miura Y, Nakamura N, Quelle F W, Witthuhn B A, Ihle J N, Aoki N. Induction of tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav and expression of Pim-1 correlates with Jak2-mediated growth signaling from the erythropoietin receptor. Blood. 1994;84:4135–4141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miura Y, Miura O, Ihle J N, Aoki N. Activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway by the erythropoietin receptor. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:29962–29969. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nagata Y, Nishida E, Todokoro K. Activation of JNK signaling pathway by erythropoietin, thrombopoietin, and interleukin-3. Blood. 1997;89:2664–2669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nishina H, Sato H, Suzuki T, Sato M, Iba H. Isolation and characterization of fra-2, an additional member of the fos gene family. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:3619–3623. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.9.3619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Okamoto K, Fujisawa K, Hasunuma T, Kobata T, Sumida T, Nishioka K. Selective activation of the JNK/AP-1 pathway in FAS-mediated apoptosis of rheumatoid arthritis synoviocytes. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:919–926. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Patel H R, Sytkowski A J. Erythropoietin activation of AP1 (Fos/Jun) Exp Hematol. 1995;23:619–625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Payne C M, Bernstein C, Bernstein H. Apoptosis overview emphasizing the role of oxidative stress, DNA damage and signal-transduction pathways. Leuk Lymphoma. 1995;19:43–93. doi: 10.3109/10428199509059662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Penta K, Sawyer S T. Erythropoietin induces the tyrosine phosphorylation, nuclear translocation, and DNA binding of STAT1 and STAT5 in erythroid cells. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:31282–31287. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.52.31282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Roffler-Tarlov S, Brown J J, Tarlov E, Stolarov J, Chapman D L, Alexiou M, Papaioannou V E. Programmed cell death in the absence of c-Fos and c-Jun. Development. 1996;122:1–9. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ryder K, Lanahan A, Perez-Albuerne E, Nathans D. Jun-D: a third member of the Jun family. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;86:1500–1503. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.5.1500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sawyer S T, Penta K. Erythropoietin cell biology. Hematol Oncol Clin N Am. 1994;8:895–911. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sawyer S T, Penta K. Association of JAK2 and STAT5 with erythropoietin receptors—role of receptor phosphorylation in erythropoietin signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:32430–32437. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.50.32430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schlingensiepen R, Terlau H, Brysch W, Schlingensiepen K H. Differential expression of c-jun, junB and junD in rat hippocampal slices. Neuroreport. 1994;6:101–104. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199412300-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schutte J, Minna J D, Birrer M J. Deregulated expression of human c-jun transforms primary rat embryo cells in cooperation with an activated c-Ha-ras gene and transforms Rat-1a cells as a single gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:2257–2261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.7.2257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Silva M, Grillot D, Benito A, Richard C, Nunez G, Fernandez-Luna J L. Erythropoietin can promote erythroid progenitor survival by repressing apoptosis through BclXL and Bcl-2. Blood. 1996;88:1576–1582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tauchi T, Feng G S, Shen R, Hoatlin M, Bagby G, Kabat D, Lu L, Broxmeyer H E. Involvement of SH2-containing phosphotyrosine phosphatase Syp in erythropoietin receptor signal transduction pathways. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:5631–5635. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.10.5631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tauchi T, Toyama K, Feng G S, Broxmeyer H E, Krystal G. Tyrosine 425 within the activated erythropoietin receptor binds Syp, reduces the erythropoietin required for Syp tyrosine phosphorylation, and promotes mitogenesis. Blood. 1996;87:4495–4501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Terada K, Kaziro Y, Satoh T. Ras-dependent activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase/stress-activated protein kinase in response to interleukin-3 stimulation in hematopoietic BaF3 cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:4544–4548. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.7.4544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Testolin L, Carson C, Wang Y Z, Walker P R, Armato U, Sikorska M. Jun and JNK kinase are activated in thymocytes in response to VM26 and radiation but not glucocorticoids. Exp Cell Res. 1997;230:220–232. doi: 10.1006/excr.1996.3419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Thomas P S. Hybridization of denatured RNA and small DNA fragments transferred to nitrocellulose. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:5201–5205. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.9.5201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Todokoro K, Sugiyama M, Nishida E, Nakaya K. Activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade through erythropoietin receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;203:1912–1919. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Verheij M, Bose R, Lin X H, Yao B, Jarvis W D, Grant S, Birrer M J, Szabo E, Zon L I, Kyriakis J M. Requirement for ceramide-initiated SAPK/JNK signalling in stress-induced apoptosis. Nature. 1996;380:75–79. doi: 10.1038/380075a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wakao H, Gouilleux F, Groner B. Mammary gland factor (MGF) is a novel member of the cytokine regulated transcription factor gene family and confers the prolactin response. EMBO J. 1995;14:854–855. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07064.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wickrema A, Krantz S B, Winkelmann J C, Bondurant M C. Differentiation and erythropoietin receptor gene expression in human erythroid progenitor cells. Blood. 1992;80:1940–1949. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Witthuhn B A, Quelle F W, Silvennoinen O, Yi T, Tang B, Miura O, Ihle J N. JAK2 associates with the erythropoietin receptor and is tyrosine phosphorylated and activated following stimulation with erythropoietin. Cell. 1993;74:227–236. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90414-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Xia Z, Dickens M, Raingeaud J, Davis R J, Greenberg M E. Opposing effects of ERK and JNK-p38 MAP kinases on apoptosis. Science. 1995;270:1326–1331. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5240.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zerial M, Toschi L, Ryseck R P, Schuermann M, Muller R, Bravo R. The product of a novel growth factor activated gene, fos-B, interacts with Jun proteins enhancing their DNA binding activity. EMBO J. 1989;8:805–815. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03441.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhao B H, Yu W P, Qian M, Simmons-Menchaca M, Brown P H, Birrer M J, Sanders B G, Kline K. Involvement of activator protein-1 (AP-1) in induction of apoptosis by vitamin E succinate in human breast cancer cells. Mol Carcinog. 1997;19:180–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhuang H, Niu Z, He T-C, Patel S V, Wojchowski D M. Erythropoietin-dependent inhibition of apoptosis is supported by carboxyl-truncated receptor forms and blocked by dominant-negative forms of Jak2. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:14500–14504. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.24.14500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhuang H, Patel S V, He T C, Niu Z, Wojchowski D M. Dominant negative effects of a carboxy-truncated Jak2 mutant on Epo-induced proliferation and Jak2 activation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;204:278–283. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]