Abstract

Nitrated fatty acids (NO2-FA) are an endogenous class of signaling mediators formed mainly during digestion and inflammation. The signaling actions of NO2-FA have been extensively studied, but their detection and characterization lagged. Several different nitrated fatty acid species have been reported in animals and humans, but their formation remains controversial, and a systemic approach to define the endogenous pool of NO2-FA is needed. Herein, we screened for endogenous NO2-FA in urine from healthy human volunteers as this is the main excretion route for NO2-FA and its metabolites, and it provides an excellent matrix for evaluation. Only isomers of two fatty acids, conjugated linoleic and linolenic acid were found to be nitrated. Several, previously unknown, nitrated species were identified and confirmed using high-resolution mass spectrometry, fragmentation analysis, and compared to synthetic nitrated standards, the main group corresponding to nitrated conjugated linolenic acid (NO2-CLnA). In contrast, we were unable to confirm the presence of previously reported nitrated omega-3’s, oleic acid, arachidonic acid and α- and γ-linolenic acid, suggesting that their biological formation and presence in humans should be re-evaluated. Metabolite analysis of NO2-CLnA in human urine identified cysteine adducts and β-oxidation products, which were compared to the metabolic products of nitrated standards obtained using primary mouse hepatocytes. Importantly, NO2-CLnA isomers belong to two defined groups, are electrophilic, participate in Michael addition reactions and account for 39% of total urinary NO2-FA, highlighting their relative abundance and possible role in cell signaling.

Keywords: nitrated conjugated linolenic acid, nitro-fatty acid, electrophile, mass spectrometry, nitration, nitrated fatty acid

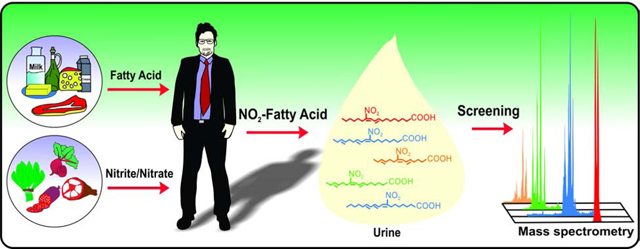

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Nitrated fatty acids (NO2-FA) are electrophilic molecules present in plants, animals, and humans that form during digestion and inflammation and display pleiotropic signaling activities (1). The most robust signaling responses exerted by NO2-FA are the activation of the heat shock response and the Nrf2/KEAP1 antioxidant pathway, and the inhibition of the master modulator of inflammation Nf-kB (2,3). Other signaling activities have been described and are dominant in specific cell/tissue types or related to defined pathological conditions. Among these, the impact of the inhibition of xanthine oxidase, epoxide hydrolase, STAT, Angiotensin receptor II and STING has been demonstrated in biochemical, cellular, and preclinical animal models (4,5).

Nitrite is an important bioactive anion that regulates cell signaling mechanisms through the formation of iron complexes and nitrosation and nitration reactions upon reduction to nitric oxide and nitrogen dioxide, playing a central role in the nitration of fatty acids (6,7). Nitrite is mainly acquired from dietary sources (e.g., leafy vegetables and cured meat) or by nitrate reduction in the oral cavity by orogastric tract commensal bacteria (8). Oxidation of nitrite, catalyzed by acid, heme-containing or molybdenum-cofactor proteins, is a significant source of nitrogen dioxide, the reactive species responsible for fatty acid nitration (6,9). In humans, the salivary and dietary nitrate and nitrite provide the substrate for the gastric formation of NO2-FA, constituting the primary source of these signaling species in the systemic circulation (7). In contrast, products derived from nitric oxide oxidation or heme-dependent nitrite reduction in blood and tissues are responsible for the local formation of NO2-FA, particularly during inflammation (10,11).

Dietary fats are composed of saturated, monounsaturated, and polyunsaturated fatty acids and provide the substrate for nitration reactions in the stomach during digestion. Among polyunsaturated fatty acids, a small group contains conjugated double bonds. Conjugated (9Z,11E)-linoleic acid (CLA), mainly acquired from dairy and meat products, is the most abundant and studied conjugated fatty acid (12). Fatty acids containing a conjugated triene are also dietary components, typically 18 carbons long and plant-derived. These are particularly abundant in pomegranate and bitter guard, where their levels in seeds can reach between 30 to 70 wt% lipid (13,14). In contrast, isomers of linolenic acid with a conjugated diene and a non-conjugated alkene group are mainly present in dairy-derived products. Within this group, rumelenic acid (conjugated (9Z, 11E, 15Z) linolenic acid) is the most abundant conjugated linolenic acid and is found in milk and cheese (15).

In humans, nitrated conjugated linoleic acid (NO2-CLA) is the most abundant endogenous NO2-FA and can be detected in urine unmodified and as cysteine adducts and β-oxidation products (16). Nonetheless, several reports have indicated the presence of different NO2-FA both in humans and animals. In this regard, the endogenous formation of NO2-FA without conjugated double bonds remains controversial, as the nitration reaction yields are significantly lower compared to conjugated fatty acids. Urine provides an excellent matrix for this study, avoiding problems inherent to the analysis of plasma samples. Moreover, pharmacological studies conducted in rats show that about a third of nitrated oleic acid (NO2-OA) is excreted in urine unmodified, as cysteine or N-acetyl cysteine adducts, or as β- and ω-oxidation products and sulfated metabolites (17).

In this study, we found that the urine nitrolipidome in human-healthy volunteers is composed exclusively by isomers of nitrated linoleic and linolenic acid. These results redefine the set of endogenous NO2-FA that are formed in humans and confirms the central role diet plays in providing the necessary substrates for the formation of these products.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials:

(9Z,12Z,15Z)-octadecatrienoic acid (α-Linolenic acid) and (6Z,9Z,12Z)-octadecatrienoic acid (γ-Linolenic acid) were purchased from Nu-Check Prep (Elysian, MN), (8Z,10E,12Z)-octadecatrienoic acid (Jacaric acid) and (9Z,11E,13Z)-octadecatrienoic acid (Punicic acid) were sourced from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor), (9E,11Z,15E)-octadecatrienoic acid (Rumelenic acid) was a gift from Dr. Miguel A. de la Fuente (Instituto del Frío, Madrid, Spain). Na[15N]O2 was purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc. (Andover, MA), 4-phenyl-1,2,4 triazoline-3,5 dione (PTAD) from TCI Chemicals (Portland, Oregon) and NaNO2, mercury (II) chloride (HgCl2) and β-mercaptoethanol (β-ME) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Solvents used for synthetic reactions were of HPLC grade or better from Fisher Scientific (Fairlawn, NJ). Solvents used for extractions and mass spectrometric analyses were MS grade and sourced from Burdick and Jackson (Muskegon, MI). Solid-phase extraction (SPE) columns (C18 reverse phase; 500 mg, 6 ml capacity) were purchased from Thermo Scientific.

Human studies:

Healthy human subjects were recruited and informed consent was obtained. Subjects’ age ranged from 25 to 60 years old. Information, including the subjects’ diet and intake of over the counter supplements was obtained via a questionnaire, and urine samples were collected from all enrolled subjects. This study abides by the Declarations of Helsinki Principles, and the research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Pittsburgh (IRB STUDY18120013).

Synthesis of nitrated fatty acids:

NO2-α-linolenic acid, NO2-γ-linolenic acid, NO2-jacaric acid NO2-rumelenic NO2-arachidonic, NO2-eicosapentaenoic and NO2-docosahexaenoic acid were synthesized by biphasic acid nitration using NaNO2 or Na[15N]O2. Briefly, 1mg of linoleic, α-linolenic acid, γ-linolenic acid, jacaric acid, rumelenic, arachidonic, eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acid was added into a 10 mL glass tube containing 2.0 mL of 1% sulfuric acid in water (v/v) and 3 mL of hexane. The tube was covered with a septum and sparged with nitrogen for 15 min or until 1 mL of the hexane layer had evaporated. A 2 M solution of NaNO2 or Na[15N]O2 in water was sparged with N2 for 10 min. The degassed NaNO2 or Na[15N]O2 solution was added to the biphasic solution, sealed and reacted for 2h at room temperature with agitation. After completion, the organic layer containing the NO2-FA was dried under nitrogen, resuspended in methanol, and purified by UV-HPLC.

Nitro-fatty acid extraction from human urine:

Urine samples (first void of the day) were collected, aliquoted, and stored at −80°C (<1 month). After thawing, 5 ml urine samples were extracted using C18 SPE columns. Columns were conditioned with 100% methanol, followed by 2 column volumes of 5% methanol. Samples were loaded and the SPE columns washed with 2 column volumes of 5% methanol and dried under vacuum for 30 min. Lipids were eluted with 3 ml methanol, the solvent evaporated under a stream of nitrogen and samples reconstituted in 200 μl of methanol for HPLC-MSMS analysis. The concentration of accessible nitroalkene (free acid plus Michael adducts) was obtained by incubating the urine samples with 20 mM mercury (II) chloride (HgCl2) for 30 min at 37°C before extraction. The Hg2+ competes for the nitroalkene-adducted cysteine displacing the equilibrium with the elimination of the nitroalkene and formation of Hg-cysteine adducts.

Chromatographic analysis:

NO2-FA metabolites in urine lipid extracts were analyzed by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS using gradient solvent systems consisting of water containing 0.1% acetic acid (solvent A) and acetonitrile containing 0.1% acetic acid (solvent B). Urine extracts were resolved for quantification and characterization using a reverse phase HPLC column (2 × 100 mm 5 μm Luna C18(2) column; Phenomenex) at a 0.70 ml/min flow rate. Samples were loaded onto the column at 35% B, maintained for 0.3 min and eluted with a linear increase in solvent B from 35–100% of B over 8 min.

Mass spectrometry - Characterization:

Analytes of interest were characterized both in collision-induced dissociation (CID) and high collision energy dissociation (HCD) modes using a Q-Exactive Orbitrap (Thermo Scientific) equipped with a HESI II heated electrospray source. The following parameters were used: source temperature 400°C, capillary temperature 360°C, sheath gas flow 30, auxiliary gas flow 15, sweep gas flow 2, source voltage 3.3 kV, S-lens RF level 62 (%). The instrument FT-mode was calibrated using the manufacturer’s recommended calibration solution.

Quantification:

Analyte quantification was performed in multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode using a QTrap 6500+ triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Sciex, San Jose, CA) equipped with an electrospray ionization source. Internal standard (IS) curves using synthetic NO2-rumelenic acid and [15N]O2-rumelenic were prepared to quantify endogenous NO2-FA. Precursor ion scans following the charged loss of NO2- (m/z 46) upon CID were performed to identify potential new analytes containing a nitro group. NO2-FA levels were normalized to urine creatinine concentrations that were determined using a colorimetric assay kit (Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, Mi) measuring absorbance at 535 nm after dilution in NaOH and reaction with picric acid.

Derivatization of conjugated dienes:

The presence of conjugated dienes was detected upon derivatization of urine lipid extracts with 100 mM PTAD to form their respective Diels-Alder adducts (18). These adducts were specifically detected monitoring the neutral loss of the isocyanatobenzene fragment from PTAD adducts (m/z:119) upon CID on the triple quadrupole mass spectrometers (18).

Detection of cysteine adducts:

Cysteine adducts of NO2-FA were detected in human urine following the characteristic charged loss of cysteine upon CID (m/z:120) in negative ion mode and confirmed in positive ion mode following the neutral loss of HNO2.

Mouse primary hepatocyte isolation:

All animal experiments were performed with the approval of the University of Pittsburgh’s IACUC. Mouse primary hepatocytes were isolated from 8-week-old male C57Bl/6 J mice from Jackson Laboratories. Mice were anesthetized using isoflurane (Piramal Critical Care, India). The abdominal area was cleaned with 70% alcohol followed by a U-shape incision. The portal vein was cannulated with a 24-gauge i.v. catheter (Terumo Medical Corporation, MD) and secured with a surgical knot. The liver was perfused at a rate of 5ml/min with 50ml of pre-warm (40°C) liver perfusion media (Gibco, #17701038) supplemented with 2% penicillin-streptomycin (Sigma Chemical Company). The vena cava was cut and the liver perfused at the same rate with 50ml of pre-warm liver digest media (Gibco, #17703034). Occlusion of the vena cava was repeatedly performed during perfusion. The liver was removed and placed in a 100 mm dish filled with 20ml of cold plating media (William’s E Medium (WEM) supplemented with plating supplements (Gibco, #CM3000)). The digested liver was torn with forceps, filtered through 100 μm nylon cell strainer (Falcon, NC) and centrifuged at 50×g for 3 min at 4°C. The pellet was washed two times with plating media and centrifuged. Hepatocytes were resuspended into 20ml of plating media, mixed with 20ml of 40% cold Percoll (GE Healthcare, Sweden) and centrifuged at 150xg for 7 min at 4°C. The bottom pellet was washed two times and centrifuge at 50xg for 3 min at 4°C. Hepatocytes were resuspended in 10ml of plating media and counted using a hemacytometer (Fisher Scientific). Cell viability (>95%) was assessed using Trypan blue stain (Gibco, NY).

In vitro metabolism of nitrated fatty acids:

Hepatocytes were seeded in collagen-coated plates (Gibco, NY) at 2.2×105 cells/6-well. After a 3-h attachment period in the 37°C incubator with 5% CO2, the medium was removed and hepatocytes were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Gibco, UK). Fresh maintenance medium (WEM supplemented with maintenance supplements (Gibco, #CM4000)) was added. Hepatocytes were cultured for 16-h in 37°C incubator with 5% CO2 before incubation with NO2-rumelenic or NO2-jacaric acid for 1-hour. Hepatocytes were then washed two times with PBS, collected into 1.5ml Eppendorf and centrifuged at 12.000xg for 5 min at 4°C. The pellet was kept at −80°C until mass spectrometry analysis.

RESULTS

Nitrated fatty acids in urine

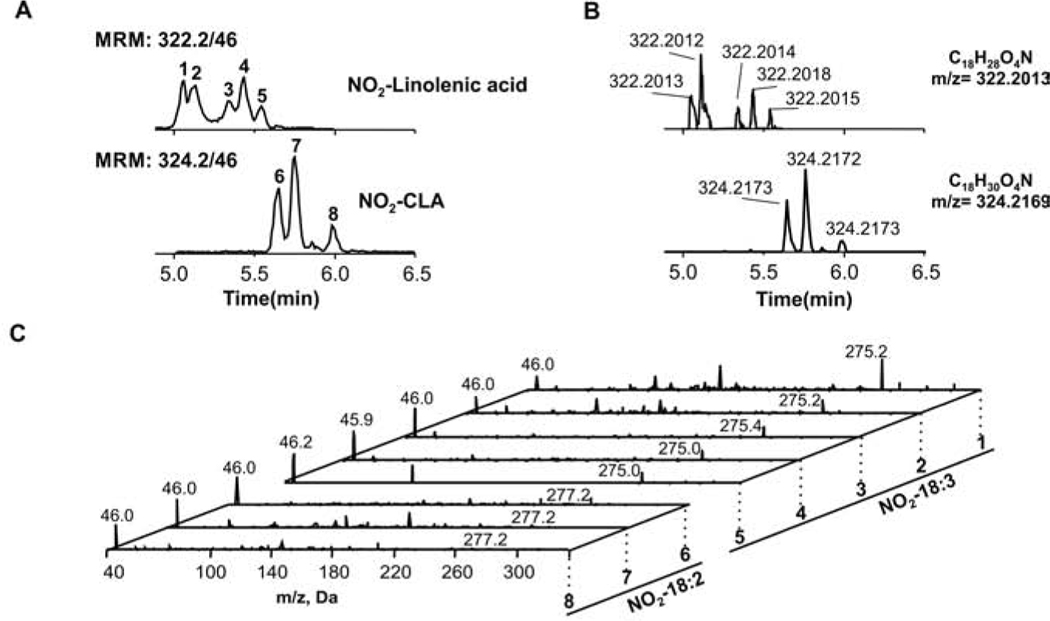

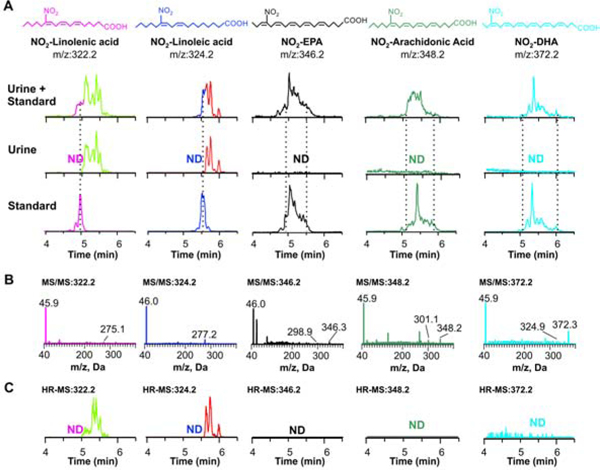

To define the spectrum of NO2-FA present in human urine, we conducted a mass spectrometry-based screen. The triple quad mass spectrometer analysis consisted of following the characteristic charged loss of NO2- (m/z 46) upon CID in negative ion mode from fatty acids with acyl chains ranging from 18 to 24 carbons with up to 6 unsaturations (19). This is a common fragment to all fatty acids containing a nitroalkene or nitroalkane group. We focused the analysis on potential NO2-FA with 18 carbon or longer acyl chains, as shorter fatty acids may correspond to their metabolic products and would be evaluated at a second stage (16). Based on MRM transition, only two groups of analytes were identified with the screen, with m/z values consistent with nitrated linolenic acid (5 peaks, NO2-CLnA, 322.3>46) and NO2-CLA (3 peaks, 324.3>46) (Fig 1A). The mass of these peaks was confirmed by high-resolution mass spectrometry (HR-MS), falling within a 2 ppm range from their theoretical m/z value (Fig 1B). Fragment analysis in a triple quadrupole confirmed the major neutral losses of HNO2 (m/z 275.2 and 277.2 for NO2-CLnA and NO2-CLA respectively) and formation of the NO2- ion (Fig 1C) in all cases. No other NO2-FA were detected with the screen.

Fig. 1.

Profiles of nitrated fatty acids in human urine. A. Profile of NO2-CLnA (upper) and NO2-CLA (bottom) present in urine from healthy human subjects. B. Liquid chromatography-coupled to high-resolution mass spectrometry showing m/z values that confirm the molecular composition for each of the peaks detected in the urine screen. C. MS/MS fragmentation of m/z 322.2 (NO2-CLnA) and 324.2 (NO2-CLA), showing neutral loss of HNO2 and the formation of the NO2- ion.

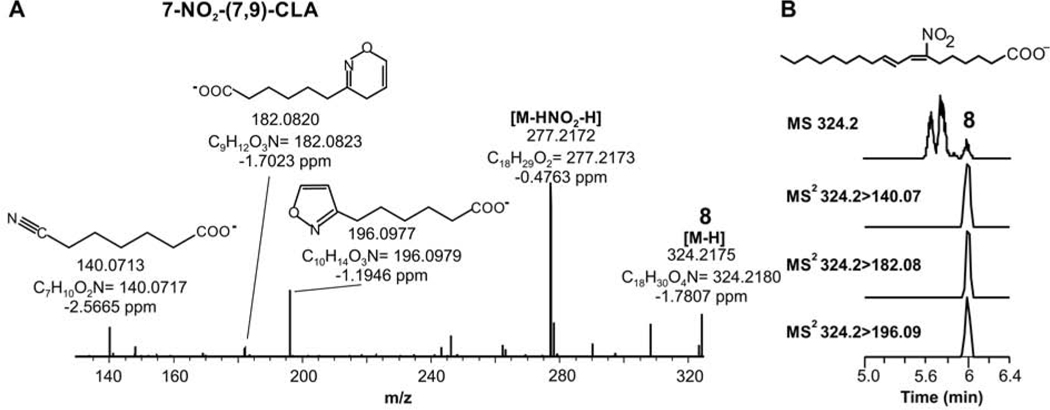

The main two peaks of NO2-CLA corresponded to the already reported 12-NO2-CLA and 9-NO2-CLA (peaks #6 and 7, respectively, Fig 1A) isomers. The third chromatographic peak corresponded to an unknown isomer (peak #8). Further evaluation of peak #8 through fragmentation analysis shows three specific fragment ions corresponding to predicted nitroalkene carbon-chain fragmentation products (Fig 2). These fragments position the NO2 group on carbon 7 with double bonds present at carbons 7 and 9 to form 7-NO2-(7,9)-octadecadienoic acid (7-NO2-(7,9)-CLA). The flanking carbons of the conjugated system are the preferred sites for nitration (18). Thus, we searched for the specific fragment ions corresponding to the 10-NO2-(7,9)-octadecadienoic acid (10-NO2-(7,9)-CLA), (fragments m/z 129.1, 143.1, 185.1 and 167.1) but failed to detect them. Given its structure and the commonly observed lower retention times of nitroalkenes with the NO2 group distal to the carboxylic acid, it is possible that this molecule coelutes with the more abundant 9 and 12-NO2-CLA, impairing its detection.

Fig. 2.

Characterization of 7-NO2-(7,9)-CLA isomer in urine samples. A. High-resolution MS/MS spectrum of peak #8 showing the specific fragments and structural assignment. B. Triple quadrupole MS/MS data showing the specific formation and elution of fragment ions identified in the HR-MSMS studies. Ion fragments indicate that the NO2 group is positioned on carbon 7.

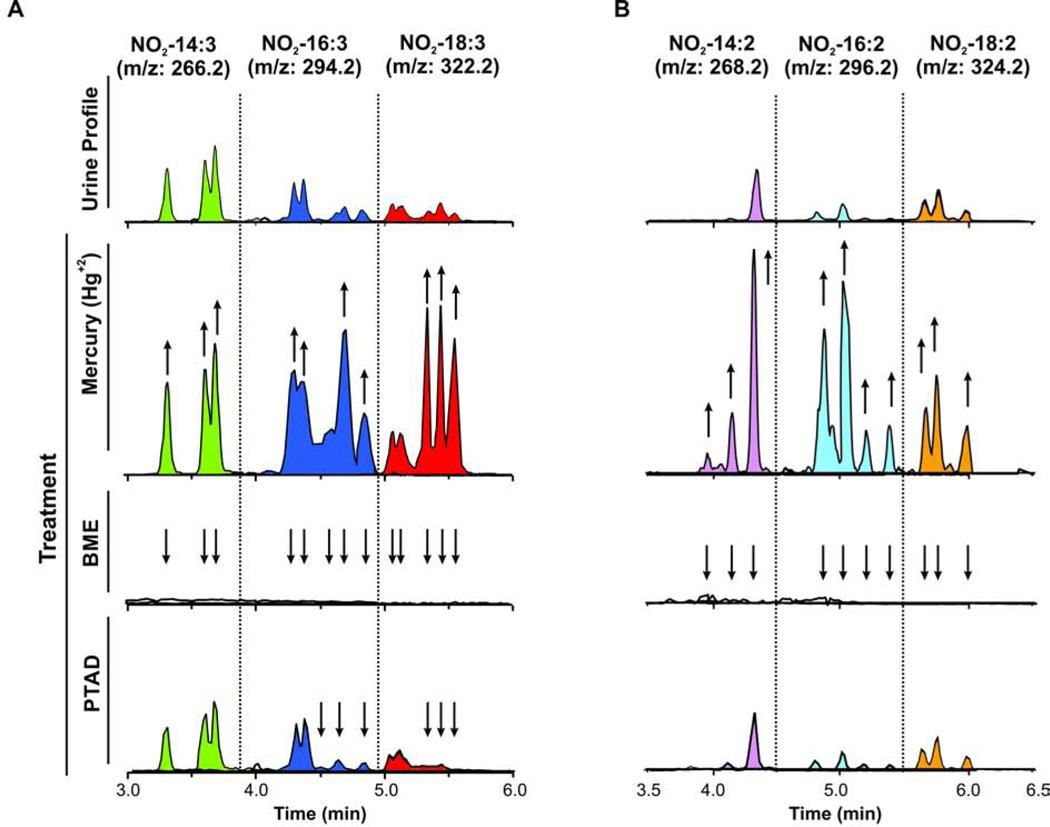

Previously, we reported that NO2-FA are mainly metabolized through β-oxidation, reduction of the nitroalkene to a nitroalkane, and addition to glutathione. Next, we performed a screen for possible β-oxidation metabolites of NO2-CLA and NO2-CLnA in urine samples. A series of peaks corresponding to dinor (-[C2H4], one round of β-oxidation), and tetranor (-[C4H8], two rounds of β-oxidation) NO2-CLA and NO2-CLnA were observed. These species were confirmed by neutral losses of HNO2 (not shown), NO2- fragment formation (upper panels on Fig 3 A,B) and HR-MS at the 2ppm level (not shown).

Fig. 3.

Characterization and reactivity of urinary NO2-FA and their metabolites. A. Chromatographic profile of NO2-CLnA, dinor-NO2-CLnA and tetranor-NO2-CLnA (parent, and products of 1 and 2 cycles of β-oxidation, respectively), before (upper panel) and after treatment with mercury, β-ME or PTAD (lower panels). B. Chromatographic profile of NO2-CLA and its β-oxidation metabolites (dinor-NO2-CLA and tetranor-NO2-CLA) before (upper panel) and after treatment with mercury, β-ME or PTAD (lower panels). The arrows indicate increases or decreases in the signal intensity after the different treatments.

Nitroalkenes detected in urine samples are commonly excreted as cysteine adducts in humans and N-acetylcysteine adducts in rodents (16,17). The treatment of urine samples with the strong electrophile Hg2+ displaces adducted nitroalkenes resulting in free nitroalkenes and Hg-thiol adducts (16,20). We previously reported that urine incubation with Hg2+ increased the pool of free NO2-CLA more than tenfold (16). In the current study, the fold increase was similar for the main NO2-CLA isomers (Fig 3B) showing 12 and 9 fold changes for 9-NO2-CLA, 12-NO2-CLA, respectively, and a smaller 3.5 fold increase for 7-NO2-(7,9)-CLA. In contrast, the increase of NO2-CLnA levels upon Hg2+ treatment was not proportional to the free NO2-CLnA levels across the isomers, with the largest increases occurring with the group of peaks #3 to 5 (10 fold), and peaks #1 and 2 showing only a 2.5 fold increment in concentration after Hg+2 treatment (Fig 3 and Fig Suppl S5). The level of β-oxidation products of NO2-CLA and NO2CLnA also increased following Hg2+ treatment. Again, in this case, later eluting peaks of dinor NO2-CLnA displayed significantly larger responses to Hg2+ treatment while dinor and tetranor NO2-CLA and tetranor NO2-CLnA showed proportional increases for all its peaks. The chromatographic profile of dinor-NO2-CLA shows 4 peaks, with two larger ones corresponding to dinor-12-NO2-CLA and dinor-9-NO2-CLA. The later eluting peaks were not fully characterized but may correspond to dinor-7-NO2-(7,9)-CLA and dinor-10-NO2-(7,9)-CLA.

Endogenous free NO2-FA found in the urine usually contain an electrophilic nitroalkene group and are reactive with thiols (16,20). To confirm the presence of a reactive nitroalkene group in these molecules, urine samples were treated with an excess of the small nucleophile β-mercaptoethanol (β-ME). The treatment eliminated all the NO2-FA peaks, and the corresponding β-ME Michael adducts of NO2-CLA and NO2-CLnA were formed (Fig 3 and Suppl Fig S1B and S2). To gain further structural information on the NO2-CLnA isomers, the samples were treated with PTAD. PTAD reacts specifically with conjugated double bonds, but the reaction is strongly deactivated by the presence of the electron-withdrawing NO2 group on one of the conjugated double bonds (Suppl Fig S1A). As shown in Fig 3B (lower panel), none of the NO2-CLA isomers reacted with PTAD, while only the subset of three later eluting peaks of NO2-CLnA reacted with PTAD to form the corresponding endo- and exo-Diels-Alder products (Fig 3A, lower panel). Similar to the differential responses obtained with Hg2+, only the late eluting peaks of dinor-NO2-CLnA reacted with PTAD. No reactions with PTAD were observed with NO2-CLA or any its metabolites and tetranor NO2-CLnA (Fig 3 and Suppl Fig S2).

The reactivity of PTAD towards a subset of NO2-CLnA suggested the presence of a system containing three double bonds conjugated. Linolenic acid isomers containing all its double bonds conjugated are typically found in some plant-derived oils and have unsaturations in carbons 8,10, and 12 or 9,11, and 13 (21). Some of these fatty acids are major components of seed oils, where they can reach up to 83% of total fatty acids and can include α-eleostearic punicic, jacaric, punicic and calendic acid among others (22).

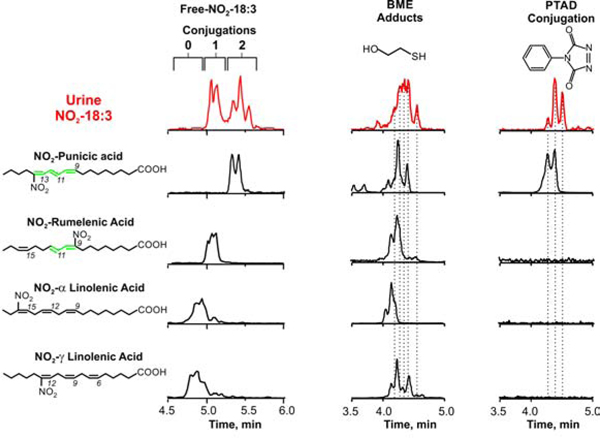

To better characterize the urine NO2-FA, α-linolenic, γ-linolenic, rumelenic and punicic acid standards were nitrated in vitro using acidic conditions in the presence of NO2-, a mechanism similar to the one operative in the gastric compartment during digestion (18). As expected, nitrated α- and γ-linolenic acid standards (NO2-LnA) displayed the shortest retention times (RT), followed by nitrated rumelenic acid (NO2-rumelenic) and punicic acid (NO2-punicic), as the presence of additional conjugated double bonds increases the linearity of the molecule and correlates with longer retention times (Fig 4). Urine samples showed no peaks eluting at RT corresponding to non-conjugated NO2-LnA. In contrast, peaks #1–2 coeluted with NO2-rumelenic acid and peaks #3–5 eluted in the region of NO2-punicic acid (Fig 4) and NO2-jacaric acid (not shown). All these synthetic nitrated species were electrophilic and reacted completely with β-ME and, as expected, only NO2-punicic acid reacted with PTAD (Fig 4, Supp Fig S1A). The reaction products of NO2-punicic with PTAD coeluted with the PTAD-derivatized species obtained from human urine samples.

Fig. 4.

Comparative chromatographic profiles of NO2-CLnA present in human urine and synthetic nitrated octadecatrienoic acids. Left column Urine (red) and standards of NO2-CLnA containing conjugated triene (punicic acid), a conjugated diene (rumelenic acid) and no conjugations (α- andγ-linolenic acid). Center column, profile of corresponding β-ME adducts showing that all NO2-CLnA are electrophilic. Right column, elution profile of PTAD derivatization products showing that only punicic acid reacted with PTAD.

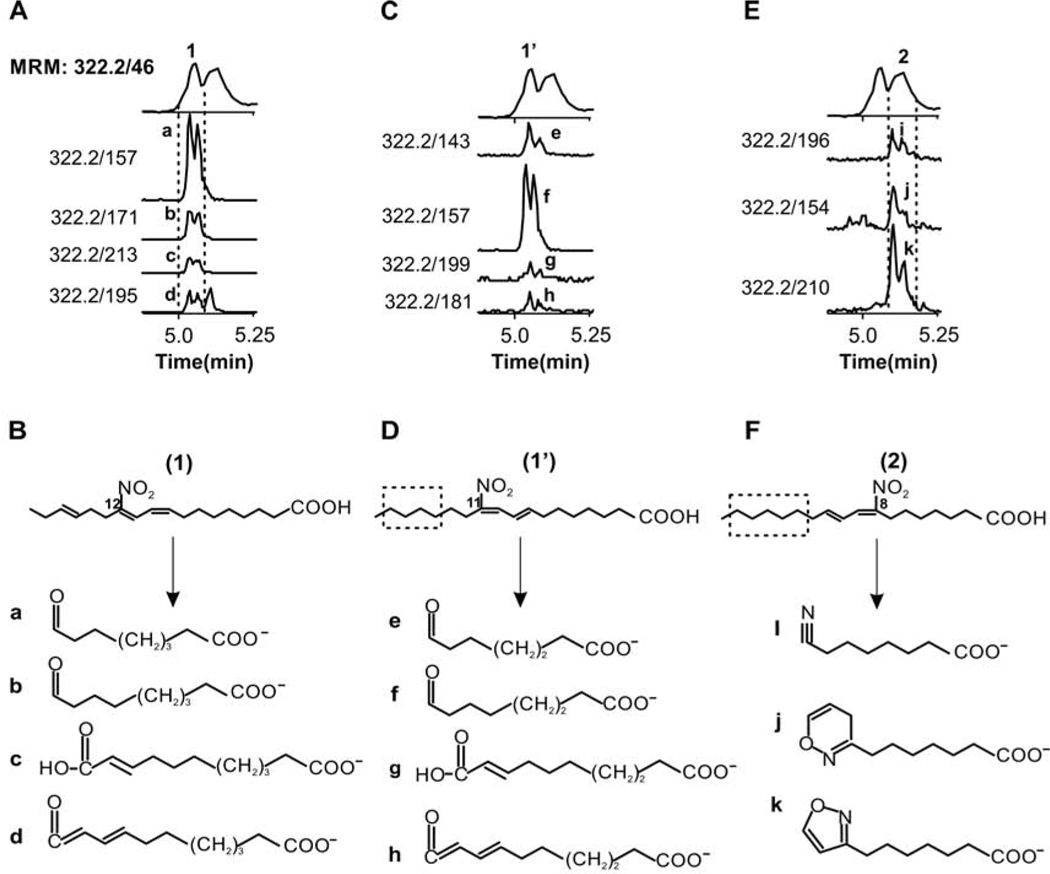

Next, we attempted to structurally characterize the peaks #1 and #2, which, based on PTAD reactivity, contain a conjugated double bond and an isolated double bond. Fragmentation analysis and specific fragment elution profiles provided the structural information to assign the position of the NO2 for some of the metabolites found in urine. Following the elution of specific fragments, peak #1 is composed of two positional isomers of NO2-CLnA, corresponding to 11-NO2-(8,10,X)CLnA (X, the third double position has not been defined and is on or after carbon 13) and 12-NO2-(9,11,15)CLnA (Fig 5). These specific fragments display a split elution, possibly indicating the presence of stereoisomers. Confirming these findings, the fragmentation of synthetic NO2-rumelenic yielded the same fragment ions that characterized 12-NO2-(9,11,15)-CLnA in peak #1 (Suppl Fig S3A). Based on the fragmentation pattern of peak #2, this peak corresponds to 8-NO2-(8,10,Y)-CLnA (Y, the third double position has not been defined and is on or after carbon 13) and also shows a split elution of specific fragments, possibly, as a consequence of the presence of diastereomers.

Fig. 5.

Structural characterization of NO2-CLnA isomers containing a conjugated diene. Fragment m/z values were determined from LC-HRMSMS experiments and used to determine the presence of specific isomers in the different peaks. A, C and E Human urine elution profiles of specifics MRM’s transitions for peaks 1, 1’ and 2 B, D and F Assignment of fragment structures and rearrangement product ions formed upon Collision-induce dissociation (CID). The position for the isolated double bond for 1’ and 2 has not been determined and the dash line indicates the region for a possible position of the third double bond.

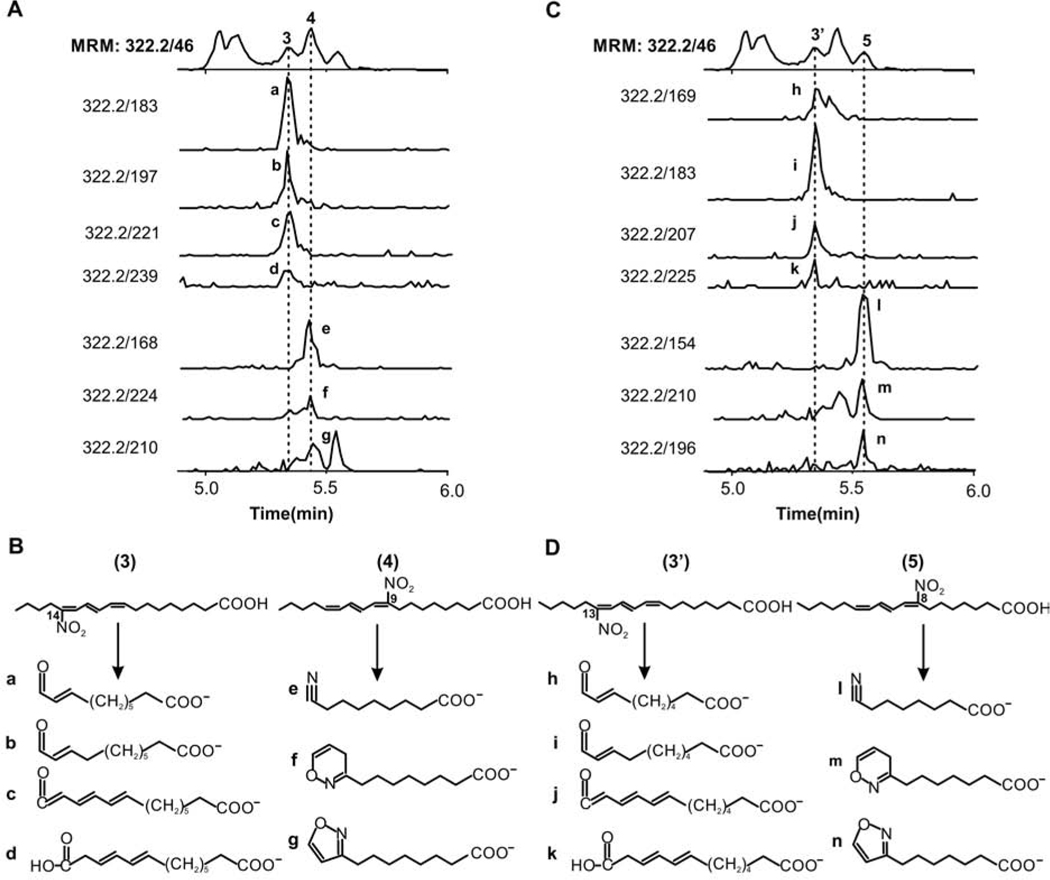

Fragmentation and elution profiles indicate that peaks #3 to 5 include at least four species that were amenable to structural characterization. Peak #3 contains two isomers of NO2-CLnA with all three double bonds conjugated identified as 14-NO2-(9,11,13)-CLnA and 13-NO2-(8,10,12)-CLnA. Fragmentation of 14-NO2-(9,11,13)-CLnA shows the expected fragments resulting from gas-phase cyclization of the nitroalkene during CID (Fig 6), as previously characterized for NO2-OA and NO2-CLA (18,19). Peak #4 corresponds to 9-NO2-(9,11,13)-CLnA, the other nitration product of (9,11,13)-CLnA as the flanking carbons of conjugated systems are preferentially nitrated. Peaks #3’ and 5 correspond to the two expected nitration products of (8,10,12)-CLnA, 13-NO2-(8,10,12)-CLnA, and 8-NO2-(8,10,12)-CLnA, respectively. The CID-induced acyl chain fragmentation products confirmed the presence of nitroalkenes. The identification of these isomers in urine was confirmed through coelution studies and fragmentation comparisons with synthetic NO2-punicic acid, confirming the structural assignments of peaks #3 and 4 (Suppl Fig S3B and S3C).

Fig. 6.

Structural characterization of NO2-CLnA isomers containing conjugated trienes. Fragment m/z values were obtained on LC-HR-MSMS experiments and used to determine the presence of specific isomers in the different peaks. A and C, Human urine elution profiles of specifics MRM’s transitions for peaks 3, 3’, 4 and 5. B and D, Assignment of fragment structures and rearrangement product ions formed upon Collision-induce dissociation (CID).

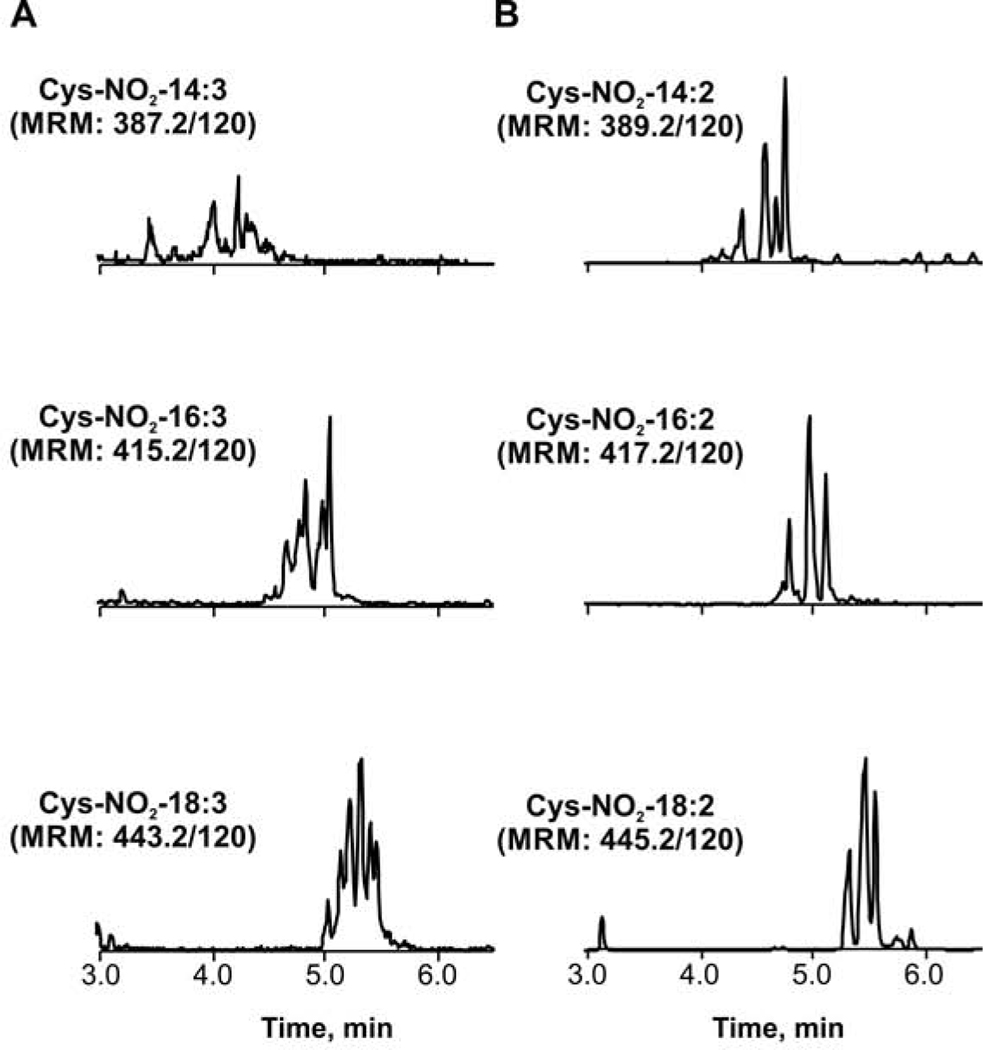

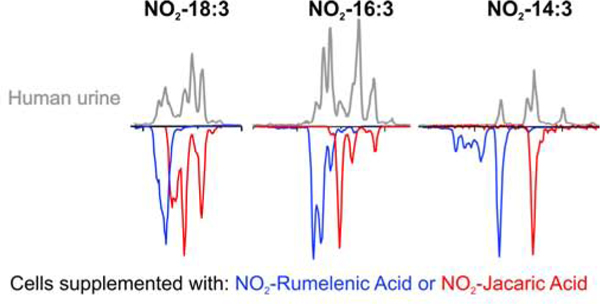

The excretion of NO2-FA occurs principally through renal filtration as cysteine adducts. Thus, we evaluated the presence and profiles of cysteine adducts of NO2-CLA and compared them with those detected for NO2-CLnA isomers. Significant levels of Cys-NO2-CLA and the presence of lower levels of Cys-NO2-CLnA were observed (Fig 7). While we have previously characterized the different isomers of Cys-NO2-CLA, including the β and δ adducts, the Cys-NO2-CLnA adducts resisted our attempts for more in-depth MSMS-based structural characterizations(23). Nonetheless, the Cys adducts of both Cys-NO2-CLA and Cys-NO2-CLnA showed the expected profile and mass spectrometry-based fragmentation in positive ion mode (neutral loss of HNO2, Supp Fig S4), and treatments with β-ME or Hg2+ eliminated the presence of these adducts (data not shown).

Fig 7.

Chromatographic profile of cysteine conjugates of NO2-CLnA and NO2-CLA in human urine. A. Elution profile of Cys-NO2-CLnA (bottom panel) and the cysteine adducts its dinor- and tetranor β-oxidation products (middle and upper panel, respectively). B. Elution profile of Cys-NO2-CLA (bottom panel) and the cysteine adducts its dinor- and tetranor β-oxidation products (middle and upper panel, respectively).

The atomic composition of the dinor and tetranor NO2-CLnA peaks was confirmed at the 2 ppm level, but the intensity of the peaks precluded a fragmentation analysis evaluating the presence of specific isomers. To confirm that the metabolism of the nitrated 18 carbon fatty acid would generate the metabolites observed in urine, we used primary mouse hepatocytes incubated with NO2-rumelenic and NO2-jacaric acid. Dinor and tetranor metabolites obtained from mouse hepatocytes showed elution profiles that closely correlated with the products found in human urine. As expected from their structural geometry, dinor and tetranor of NO2-rumelenic had lower RT than the corresponding metabolites from NO2-jacaric acid (Fig 8).

Fig 8.

Comparison of elution profiles from urine samples with the metabolic β-oxidation products of NO2-CLnA obtained from primary mouse hepatocytes. NO2-CLnA obtained from urine (gray lines) were compared with the metabolites derived after incubation of primary mouse hepatocytes cell culture with NO2-rumelenic acid (blue line) or NO2-jacaric acid (red line).

Our initial screen only showed that fatty acids with conjugated double bonds were present in urine. Nonetheless, mass spectrometry-based detection of endogenous metabolites is known to be impacted by sample processing and analytical approach. Impaired detection could be related to low extraction efficiencies, ionization, or yields of fragments ions used to detect and quantify species. To confirm that the absence of other nitrated polyunsaturated fatty acid in urine was unrelated to analytical problems, standards of nitrated linoleic, linolenic, arachidonic, eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acid were obtained by acidic nitration to mimic the nitration process during digestion. Nitrated arachidonic, eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acids presented complex elution profiles, likely related to the number of positional isomers present in the sample (Fig 9A). Targeted triple quad analysis of urine samples confirmed the absence of these species, and only NO2-CLA and NO2-CLnA were again detected. To confirm that the absence was not related to matrix effects or extraction efficiencies, the nitrated standards were spiked or not into a urine sample and extracted. Spiked urine presented a similar profile for all standards when compared to dilutions in methanol. The recovery yields and matrix effects similarly affected all standards, including NO2-CLA and NO2-CLnA, with a ~30 % decrease in overall sensitivity. As observed in Fig 9A, nitrated non-conjugated standards did not coelute with the NO2-FA detected in urine. We confirmed that all the synthetic standards displayed a major charged loss of nitrite, as indicated by the detection of a fragment ion with m/z=46 (Fig 9B). This further validated the approach used to define the nitrolipidome in human urine. Finally, urine samples were evaluated using high-resolution mass spectrometry, avoiding any artifacts related to losses due to differential fragmentation efficiencies. The theoretical m/z values for the different nitrated fatty acids were used to establish an m/z window to filter the data, and, as shown in Fig 9C, only the m/z corresponding to NO2-CLA and NO2-CLnA were detected.

Fig 9.

Non-conjugated nitrated polyunsaturated fatty acids are absent in human urine. A. Independent chromatographic profiles of nitrated standards (lower panels), urine (middle panels) and urine spiked with standards (upper panels) before extraction. Nitrated fatty acids were followed using the MRM transition [M-H]- to [NO2]- (46). B. Triple quadrupole MSMS spectra confirming nitrite (m/z 46) as the main ion fragment. C. High-resolution chromatographic profiles of urine corresponding to the filtered m/z values of the different nitrated fatty acids (filter range +/− 0.05 amu of theoretical mass).

After the characterization studies performed on different urine samples, we collected 25 human urine samples from a new cohort and quantified the content of the NO2-FA in the absence or presence of Hg2+. The basal levels of NO2-CLnA were 1.3 and increased to 10.8 pmol/mg creatinine after Hg2+ treatment (Table 1). In comparison, the level of NO2-CLA increased from 2.8 to 16.7 pmol/mg creatinine after Hg2+ (data not shown). Thus, the pool of NO2-CLnA represents 39% of total NO2-FA found in urine in these samples. Out of the 25 samples, the level of NO2-CLnA with two conjugated double bonds was only higher in three samples (75 to 87% of total) than the NO2-CLnA species containing all the double bonds conjugated (Table 1). The increase in concentration observed after treatment with Hg2+ was highly variable and ranged from as low as 0.65 to 33.90 fold (Table 1). The profiles for all NO2-CLnA and its β-oxidation metabolites provide a graphic visualization of the large variation and structural diversity observed in our study and shows the relative contribution of different conjugated nitrated species in the individual samples analyzed in our study (Suppl Fig S5).

Table 1:

Quantification of total NO2-CLnA isomers found in 25 human urines, and the relative amount (%) of species containing a conjugated diene or triene.

| Urine Samples (n:25) | Total NO2-Linolenic (pmol/mg creatinine) | NO2-Linolenic # Conjugations (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| -Hg2+ | +Hg2+ | 1 | 2 | |

| 1 | 0.52 | 4.75 | 87.4 | 12.6 |

| 2 | 1.81 | 18.30 | 30.6 | 69.4 |

| 3 | 1.71 | 12.36 | 26.8 | 73.2 |

| 4 | 0.99 | 8.55 | 21.7 | 78.3 |

| 5 | 0.63 | 11.90 | 48.8 | 51.2 |

| 6 | 0.40 | 2.04 | 75.5 | 24.5 |

| 7 | 0.96 | 2.51 | 71.3 | 28.7 |

| 8 | 0.65 | 4.42 | 23.4 | 76.6 |

| 9 | 2.07 | 15.31 | 18.1 | 81.9 |

| 10 | 2.16 | 26.03 | 22.9 | 77.1 |

| 11 | 1.62 | 14.23 | 35.4 | 64.6 |

| 12 | 0.72 | 6.90 | 35.1 | 64.9 |

| 13 | 0.89 | 4.33 | 24.4 | 75.6 |

| 14 | 0.48 | 1.38 | 37.3 | 62.7 |

| 15 | 4.09 | 21.60 | 27.6 | 72.4 |

| 16 | 1.62 | 2.68 | 16.8 | 83.2 |

| 17 | 1.29 | 8.57 | 18.8 | 81.2 |

| 18 | 1.36 | 46.12 | 31.7 | 68.3 |

| 19 | 0.80 | 3.89 | 45.7 | 54.3 |

| 20 | 1.80 | 15.18 | 23.9 | 76.1 |

| 21 | 0.59 | 3.61 | 31.6 | 68.4 |

| 22 | 1.08 | 12.24 | 23.3 | 76.7 |

| 23 | 1.68 | 6.51 | 15.0 | 85.0 |

| 24 | 2.01 | 4.48 | 12.7 | 87.3 |

| 25 | 1.66 | 12.95 | 31.0 | 69.0 |

DISCUSSION

A diverse number of NO2-FA has been reported in biological samples and obtained in vitro using biomimetic nitration systems (24,25). However, the presence of many of these endogenous NO2-FA in humans remains controversial, primarily because of previous conflicting results and the difficulties associated with their analysis (26,27). Furthermore, the evaluation of NO2-FA in plasma has been complicated by the fact that it is a more difficult matrix to study, only a small proportion is found as a free acid, with over 95% being esterified (28). NO2-FA incorporate into different complex lipids but can also form while esterified to phospholipids in lipid bilayers, triglycerides in fat or cholesterol esters and several esterified NO2-FA have been reported in human plasma (18,29–32). Importantly, LC-MSMS-based analysis of these esters has important limitations as it provides limited or no regioisomeric information. This is a consequence of poor isomer chromatographic resolution and a lack of structural information from fragmentation analysis. Moreover, NO2-FA decompose under basic hydrolysis conditions and artefactual fatty acid nitration during acid hydrolysis is always a concern (28,33,34), limiting analytical options of their content in complex lipids found in tissues and plasma. Furthermore, from a panel of over 70 biologically relevant lipid species evaluated in urine, NO2-FA have been shown to be unusually labile to deglucuronidation reactions (70 to 90 % loss), further highlighting the complexities associated with their analysis (26). With regards to unesterified NO2-FA in human plasma or urine, the presence of NO2-OA (31,35,36), NO2-CLA (7,16,18), NO2-LA (29–31), NO2-LnA (26,31), and NO2-arachidonate, NO2-palmitoleic and NO2-eicosapentaenoic acid (31) has been reported. This diversity is further increased when considering animal and plant species (24,37). Importantly, NO2-FA are mainly excreted through urine, making it an ideal matrix to study (17). To define human urinary nitrolipidome, we screened urine samples, identified, characterized endogenous NO2-FA and then quantified their levels in urine from 25 healthy human volunteers. The initial approach was based on an unbiased screen of analytes in urine that presented a loss of the NO2- anion upon CID, followed by a targeted analysis that included acyl chains 18 carbons or longer to increase the sensitivity. Only nitrated isomers of CLA and CLnA and their respective metabolites, including one and two β-oxidation cycle products and cysteine adducts were detected. All free acid nitroalkene-containing acyl chains were electrophilic and readily reacted with β-ME. Primary mouse hepatocytes were used to confirm the metabolic products of NO2-CLnA and we propose that the 14 and 16 carbons NO2-FA are metabolites of NO2-CLA and NO2-CLnA and not direct nitration products of shorter fatty acids.

The pool of endogenous nitrated conjugated fatty acids was, until now, restricted to the 9-NO2-CLA and 12-NO2-CLA. We identified 7-NO2-(7,9)-CLA as a novel nitrated CLA isomer. While we also predicted, based on the mechanisms of nitration involved in the formation of these species, the presence of 10-NO2-CLA, we failed to confirm this isomer in human urine. Based on the chromatographic characteristics of 9-NO2-CLA and 12-NO2-CLA, 10-NO2-CLA is predicted to have RT similar to 9-NO2-CLA. Given the more abundant CLA nitrated products compared to NO2-(7,9)-CLA, it is likely that the 10-NO2-CLA is present in the samples but undetectable under our chromatographic conditions.

The diversity of isomers of nitrated CLnA proved to be complex and many resisted further characterization. Based on our data, NO2-CLnA can be divided into two main groups, containing either a conjugated diene or conjugated triene. We have previously shown for nitrated bis-allylic linoleic acid and NO2-CLA that the conjugation of double bonds increases the retention times (16,18) as the linearity of the molecule allows for stronger absorption to the column C18 beads. Similarly, NO2-CLnA isomers with conjugated dienes show shorter RT than conjugated trienes with the standards of nitrated α and γ linolenic acid displaying the shortest RT.

The set of NO2-CLnA containing a conjugated diene is formed by NO2-rumelenic and a nitrated CLnA product presenting unsaturation at carbons 8 and 10 with a double bond positioned on or after carbon 13 (the position remains to be defined as it resisted further characterization). Considering that ruminal bacteria is responsible for the formation of most, if not all, of these CLnA isomers containing a conjugated diene during biohydrogenation reactions, it is likely that these two NO2-CLnA correspond to 8-NO2-(8,10,14)-CLnA and 11-NO2-(8,10,14)-CLnA (15). Additionally, we have identified and validated 12-NO2-(9,11,15)-CLnA using synthetic standards formed using chemical nitration of rumelenic acid. By analogy, we would predict the presence of 9-NO2-(9,11,15)-CLnA, but we did not find defining evidence to confirm its presence. The group of nitrated CLnA with a conjugated triene presented an even higher complexity, but, since nitration occurs almost exclusively in the flanking carbons of the conjugated system, structural assignments were more straightforward. We were able to confirm the presence of NO2-punicic acid using synthetic standards and defined the presence of 8-NO2-(8,10,12)-CLnA and 13-NO2-(8,10,12)-CLnA. It is important to consider that stereochemical information should not be derived from this work, as both nitration chemistry and reversible additions to thiols induce double-bond isomerizations and the LC-based chromatography used in the present work lacks the resolving power to ensure the separation of stereoisomers, precluding any analysis in this regard. Separation of isomeric species of CLnA, derived from dairy products, have been obtained in the past using highly complex gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) arrangements and analysis has proven to be extremely complex (17). In this regard, the NO2-FA have been shown to be difficult to analyze by GC-MS, as degradation and further isomerization can introduce artifacts. As a consequence, GC-MS based approaches were not attempted in the present work.

NO2-FA can be formed locally during inflammation (11,38) and efforts are underway to assess local nitration by developing methods to detect and quantify esterifed NO2-FA (24,39–41). Nonetheless, we have previously shown that nitration reactions during digestion are the main contributors to urine NO2-FA metabolites (7,42). Thus, it is expected that the NO2-FA identified in urine are closely related to the dietary fatty acids present as substrates for nitration in the stomach. This highlights the role of the diet, as dairy and meat products are sources of not only CLA but also CLnA. The ratios and levels of CLA and CLnA in dairy products are defined by the fatty acid composition of feed sources. In this regard, feed enriched in linoleic acid leads to increased levels of CLA and feed sources rich in linolenic acid, like linseed, result in dairy products rich in CLnA (43,44). The presence of conjugated trienes in fatty acids (e.g. punicic, eleostearic, jacaric, calendic acids) is usually associated with specific plant species from several genera, with levels in seeds reaching up to 83% of total fatty acids (45). A questionnaire of the dietary components ingested in the five days before the urine sampling showed very low to no intake of plant-derived products that would provide significant sources of these fatty acids. Thus, we were not able to establish a direct correlation of dietary sources with these conjugated triene-containing NO2-FA. Nonetheless, the questionnaire revealed a prevalent use and consumption of oil-based products and an association with levels of NO2-CLnA. While we have not sought to establish the statistical significance of this correlation nor we designed the trial to evaluate it, this was an intriguing finding that gains relevance as the processing steps used in industry for plant oils, in particular bleaching, induce the isomerization of the bis-allylic double bonds in polyunsaturated fatty acids present in triglycerides (46). Certainly, the biological sources and the impact on overall NO2-FA formation has to be further evaluated, considering that the highest levels are achieved with the concurrent consumption of foodstuff rich in nitrite and nitrate.

The urinary levels of NO2-CLnA in this study are 10.8 pmol /mg creatinine, with levels of NO2-CLA being 16.8 pmol/mg creatinine. These data also show that the urine content has a significant variability ranging from 1.4 to 46.1pmol/mg creatinine. In this study, the NO2-CLA average level was similar to previously reported values (16). The other interesting aspect is the high variability in the two sets of NO2-CLnA species present in urine, with the unexpected finding of a more significant proportion of NO2-FA containing conjugated trienes. The data also shows a striking difference in levels obtained in the urine samples after Hg2+ treatment. These ratios are influenced by several factors, including Keq of the cysteine adducts, the content of cysteine and other thiols in urine, as well as the concentration of other competing electrophiles. The presence of NO2-CLA and NO2-CLnA in urine is proposed to be exclusively derived from the excretion of Cys-NO2-CLA and Cys-NO2-CLnA, followed by an elimination reaction in urine driven by the low levels of free thiols. Similar to other long-chain fatty acids, NO2-CLA and NO2-CLnA are highly bound to plasma proteins and not expected to be filtrated into urine. In contrast, the excretion of cysteine adducts through specialized transporters constitute an important elimination mechanism of these adducts. Once in urine, which has a very low thiol content, a new equilibrium for Cys-NO2-CLA and Cys-NO2-CLnA is established, with elimination of Cys and the appearance of the free acid nitroalkenes. As this process is thermodynamically and kinetically regulated, the urine content of NO2-CLA and NO2-CLnA is expected to change with time and be affected by the levels of other excreted molecules, causing the observed variability in basal levels and responses to Hg2+.

The reactivity of NO2-FA is an important characteristic that defines the signaling events modulated by these molecules. Based on the different responses to Hg2+ treatment, we expect different Keq and Kon for the different regioisomers on their reaction with thiols, as higher conjugation is expected to increase the nitroalkene reactivity (47). This may have an impact on signaling responses, which will have to be determined for these new endogenous species.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that conjugated linoleic and linolenic acids are the only NO2-FA detected in human urine. Despite previous reports, no evidence of nitrated of omega-3 FA, arachidonic acid, oleic acid, or other FA with acyl chains longer than 18 carbon was observed. This directly relates to the nitration mechanism, which indicates that the stabilized nitrated intermediate is the limiting step in the nitration process, with very low yields for non-conjugated fatty acids. In contrast to NO2-CLA, the NO2-CLnA set of products is highly complex and diversified and represents 39 % of the total pool of NO2-FA detected in urine. It has yet to be determined whether these newly discovered NO2-FA have a particular role in signaling and regulation of physiological processes.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

This human urine nitrolipidome study defines specific fatty acid nitration targets.

Nitro-conjugated linoleic and linolenic acids are the main species in human.

No other nitrated fatty acids were found in human urine samples.

Previously unreported nitro conjugated linolenic acids make up 37 % of total NO2-FA.

Data suggest a central role of diet in the formation of endogenous nitro-fatty acids.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.

This work was supported by NIH grants GM125944 and DK112854 to FJS. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

ABBREVIATIONS:

- CID

collision-induced dissociation

- MRM

multiple reaction monitoring

- HR

high-resolution

- β-ME

β-mercaptoethanol

- Hg2+

mercury chloride

- PTAD

4-phenyl-1,2,4 triazoline-3,5 dione IS, internal standard

- NO2-CLA

equimolar mixture of 9-NO2-CLA (9-nitrooctadeca-9,11-dienoic acid) and 12-NO2-CLA (12-nitro-octadeca-9,11-dienoic acid)

- NO2-CLnA

conjugated linolenic acid

- NO2-FA

nitrated fatty acid

- NO2-OA

nitrated oleic acid

- NO2-punicic

Nitrated punicic acid

- SPE

solid-phase extraction

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST.

FJS acknowledges financial interest in Complexa Inc. and Creegh Inc. No other competing financial interests are noted.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

DATA AVAILABILITY

All data are contained within the manuscript. Chromatographic and mass spectrometry raw data will be shared upon request to Sonia R. Salvatore (srs107@pitt.edu) or Francisco J. Schopfer (fjs2@pitt.edu).

REFERENCES

- 1.Schopfer FJ, Cipollina C, and Freeman BA (2011) Formation and signaling actions of electrophilic lipids. Chem Rev 111, 5997–6021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cui T, Schopfer FJ, Zhang J, Chen K, Ichikawa T, Baker PR, Batthyany C, Chacko BK, Feng X, Patel RP, Agarwal A, Freeman BA, and Chen YE (2006) Nitrated fatty acids: Endogenous anti-inflammatory signaling mediators. J Biol Chem 281, 35686–35698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kansanen E, Jyrkkänen HK, Volger OL, Leinonen H, Kivelä AM, Häkkinen SK, Woodcock SR, Schopfer FJ, Horrevoets AJ, Ylä-Herttuala S, Freeman BA, and Levonen AL (2009) Nrf2-dependent and -independent responses to nitro-fatty acids in human endothelial cells: Identification of heat shock response as the major pathway activated by nitrooleic acid. Journal of Biological Chemistry 284, 33233–33241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schopfer FJ, and Khoo NKH (2019) Nitro-Fatty Acid Logistics: Formation, Biodistribution, Signaling, and Pharmacology. Trends Endocrinol Metab 30, 505–519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hansen AL, Buchan GJ, Ruhl M, Mukai K, Salvatore SR, Ogawa E, Andersen SD, Iversen MB, Thielke AL, Gunderstofte C, Motwani M, Moller CT, Jakobsen AS, Fitzgerald KA, Roos J, Lin R, Maier TJ, Goldbach-Mansky R, Miner CA, Qian W, Miner JJ, Rigby RE, Rehwinkel J, Jakobsen MR, Arai H, Taguchi T, Schopfer FJ, Olagnier D, and Holm CK (2018) Nitro-fatty acids are formed in response to virus infection and are potent inhibitors of STING palmitoylation and signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115, E7768–E7775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeMartino AW, Kim-Shapiro DB, Patel RP, and Gladwin MT (2019) Nitrite and nitrate chemical biology and signalling. Br J Pharmacol 176, 228–245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delmastro-Greenwood M, Hughan KS, Vitturi DA, Salvatore SR, Grimes G, Potti G, Shiva S, Schopfer FJ, Gladwin MT, Freeman BA, and Gelhaus Wendell S (2015) Nitrite and nitrate-dependent generation of anti-inflammatory fatty acid nitroalkenes. Free Radic Biol Med 89, 333–341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koch CD, Gladwin MT, Freeman BA, Lundberg JO, Weitzberg E, and Morris A (2017) Enterosalivary nitrate metabolism and the microbiome: Intersection of microbial metabolism, nitric oxide and diet in cardiac and pulmonary vascular health. Free Radic Biol Med 105, 48–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Basu S, Grubina R, Huang J, Conradie J, Huang Z, Jeffers A, Jiang A, He X, Azarov I, Seibert R, Mehta A, Patel R, King SB, Hogg N, Ghosh A, Gladwin MT, and Kim-Shapiro DB (2007) Catalytic generation of N2O3 by the concerted nitrite reductase and anhydrase activity of hemoglobin. Nat Chem Biol 3, 785–794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Villacorta L, Minarrieta L, Salvatore SR, Khoo NK, Rom O, Gao Z, Berman RC, Jobbagy S, Li L, Woodcock SR, Chen YE, Freeman BA, Ferreira AM, Schopfer FJ, and Vitturi DA (2018) In situ generation, metabolism and immunomodulatory signaling actions of nitro-conjugated linoleic acid in a murine model of inflammation. Redox Biol 15, 522–531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rudolph V, Rudolph TK, Schopfer FJ, Bonacci G, Woodcock SR, Cole MP, Baker PR, Ramani R, and Freeman BA (2010) Endogenous generation and protective effects of nitro-fatty acids in a murine model of focal cardiac ischaemia and reperfusion. Cardiovasc Res 85, 155–166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Belury MA (2002) Dietary conjugated linoleic acid in health: physiological effects and mechanisms of action. Annu Rev Nutr 22, 505–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hennessy AA, Ross PR, Fitzgerald GF, and Stanton C (2016) Sources and Bioactive Properties of Conjugated Dietary Fatty Acids. Lipids 51, 377–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tanaka T, Hosokawa M, Yasui Y, Ishigamori R, and Miyashita K (2011) Cancer chemopreventive ability of conjugated linolenic acids. Int J Mol Sci 12, 7495–7509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gomez-Cortes P, Tyburczy C, Brenna JT, Juarez M, and de la Fuente MA (2009) Characterization of cis-9 trans-11 trans-15 C18:3 in milk fat by GC and covalent adduct chemical ionization tandem MS. J Lipid Res 50, 2412–2420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salvatore SR, Vitturi DA, Baker PRS, Bonacci G, Koenitzer JR, Woodcock SR, Freeman BA, and Schopfer FJ (2013) Characterization and quantification of endogenous fatty acid nitroalkene metabolites in human urine. Journal of Lipid Research 54, 1998–2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salvatore SR, Vitturi DA, Fazzari M, Jorkasky DK, and Schopfer FJ (2017) Evaluation of10-Nitro Oleic Acid Bio-Elimination in Rats and Humans. Scientific Reports 7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bonacci G, Baker PR, Salvatore SR, Shores D, Khoo NK, Koenitzer JR, Vitturi DA, Woodcock SR, Golin-Bisello F, Cole MP, Watkins S, St Croix C, Batthyany CI, Freeman BA, and Schopfer FJ (2012) Conjugated linoleic acid is a preferential substrate for fatty acid nitration. J Biol Chem 287, 44071–44082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonacci G, Asciutto EK, Woodcock SR, Salvatore SR, Freeman BA, and Schopfer FJ (2011) Gas-phase fragmentation analysis of nitro-fatty acids. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom 22, 1534–1551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schopfer FJ, Batthyany C, Baker PRS, Bonacci G, Cole MP, Rudolph V, Groeger AL, Rudolph TK, Nadtochiy S, Brookes PS, and Freeman BA (2009) Detection and quantification of protein adduction by electrophilic fatty acids: mitochondrial generation of fatty acid nitroalkene derivatives. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 46, 1250–1259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iwabuchi M, Kohno-Murase J, and Imamura J (2003) Delta 12-oleate desaturase-related enzymes associated with formation of conjugated trans-delta 11, cis-delta 13 double bonds. J Biol Chem 278, 4603–4610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hennessy AA, Ross RP, Devery R, and Stanton C (2011) The health promoting properties of the conjugated isomers of alpha-linolenic acid. Lipids 46, 105–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Turell L, Vitturi DA, Coitiño EL, Lebrato L, Möller MN, Sagasti C, Salvatore SR, Woodcock SR, Alvarez B, and Schopfer FJ (2017) The chemical basis of thiol addition to nitro-conjugated linoleic acid, a protective cell-signaling lipid. Journal of Biological Chemistry 292, 1145–1159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Melo T, Montero-Bullon JF, Domingues P, and Domingues MR (2019) Discovery of bioactive nitrated lipids and nitro-lipid-protein adducts using mass spectrometry-based approaches. Redox Biol 23, 101106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buchan GJ, Bonacci G, Fazzari M, Salvatore SR, and Gelhaus Wendell S (2018) Nitro-fatty acid formation and metabolism. Nitric Oxide 79, 38–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fu J, Schoeman JC, Harms AC, van Wietmarschen HA, Vreeken RJ, Berger R, Cuppen BV, Lafeber FP, van der Greef J, and Hankemeier T (2016) Metabolomics profiling of the free and total oxidised lipids in urine by LC-MS/MS: application in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Anal Bioanal Chem 408, 6307–6319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Woodcock SR, Bonacci G, Gelhaus SL, and Schopfer FJ (2013) Nitrated fatty acids: synthesis and measurement. Free Radic Biol Med 59, 14–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fazzari M, Vitturi DA, Woodcock SR, Salvatore SR, Freeman BA, and Schopfer FJ (2019) Electrophilic fatty acid nitroalkenes are systemically transported and distributed upon esterification to complex lipids. Journal of Lipid Research 60, 388–399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lima ES, Di Mascio P, and Abdalla DS (2003) Cholesteryl nitrolinoleate, a nitrated lipid present in human blood plasma and lipoproteins. J Lipid Res 44, 1660–1666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lima ES, Di Mascio P, Rubbo H, and Abdalla DS (2002) Characterization of linoleic acid nitration in human blood plasma by mass spectrometry. Biochemistry 41, 10717–10722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baker PR, Lin Y, Schopfer FJ, Woodcock SR, Groeger AL, Batthyany C, Sweeney S, Long MH, Iles KE, Baker LM, Branchaud BP, Chen YE, and Freeman BA (2005) Fatty acid transduction of nitric oxide signaling: multiple nitrated unsaturated fatty acid derivatives exist in human blood and urine and serve as endogenous peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor ligands. J Biol Chem 280, 42464–42475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baker PR, Schopfer FJ, Sweeney S, and Freeman BA (2004) Red cell membrane and plasma linoleic acid nitration products: synthesis, clinical identification, and quantitation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101, 11577–11582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Halliwell B, Zhao K, and Whiteman M (1999) Nitric oxide and peroxynitrite. The ugly, the uglier and the not so good: a personal view of recent controversies. Free Radic Res 31, 651–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsikas D (2017) What we-authors, reviewers and editors of scientific work-can learn from the analytical history of biological 3-nitrotyrosine. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 1058, 68–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsikas D, Zoerner A, Mitschke A, Homsi Y, Gutzki FM, and Jordan J (2009) Specific GC-MS/MS stable-isotope dilution methodology for free 9- and 10-nitro-oleic acid in human plasma challenges previous LC-MS/MS reports. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 877, 2895–2908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsikas D, Zoerner AA, Mitschke A, and Gutzki FM (2009) Nitro-fatty acids occur in human plasma in the picomolar range: a targeted nitro-lipidomics GC-MS/MS study. Lipids 44, 855–865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mata-Perez C, Padilla MN, Sanchez-Calvo B, Begara-Morales JC, Valderrama R, Corpas FJ, and Barroso JB (2018) Nitro-Fatty Acid Detection in Plants by High-Pressure Liquid Chromatography Coupled to Triple Quadrupole Mass Spectrometry. Methods Mol Biol 1747, 231–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mathers AR, Carey CD, Killeen ME, Salvatore SR, Ferris LK, Freeman BA, Schopfer FJ, and Falo LD Jr. (2018) Topical electrophilic nitro-fatty acids potentiate cutaneous inflammation. Free Radic Biol Med 115, 31–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fazzari M, Khoo NK, Woodcock SR, Jorkasky DK, Li L, Schopfer FJ, and Freeman BA (2017) Nitro-fatty acid pharmacokinetics in the adipose tissue compartment. J Lipid Res 58, 375–385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Melo T, Domingues P, Ferreira R, Milic I, Fedorova M, Santos SM, Segundo MA, and Domingues MR (2016) Recent Advances on Mass Spectrometry Analysis of Nitrated Phospholipids. Anal Chem 88, 2622–2629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Montero-Bullon JF, Melo T, Rosario MDM, and Domingues P (2019) Liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry characterization of nitroso, nitrated and nitroxidized cardiolipin products. Free Radic Biol Med 144, 183–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vitturi DA, Minarrieta L, Salvatore SR, Postlethwait EM, Fazzari M, Ferrer-Sueta G, Lancaster JR Jr., Freeman BA, and Schopfer FJ (2015) Convergence of biological nitration and nitrosation via symmetrical nitrous anhydride. Nat Chem Biol 11, 504–510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gomez-Cortes P, Bach A, Luna P, Juarez M, and de la Fuente MA (2009) Effects of extruded linseed supplementation on n-3 fatty acids and conjugated linoleic acid in milk and cheese from ewes. J Dairy Sci 92, 4122–4134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gomez-Cortes P, Civico A, de la Fuente MA, Nunez Sanchez N, Pena Blanco F, and Martinez Marin AL (2018) Effects of dietary concentrate composition and linseed oil supplementation on the milk fatty acid profile of goats. Animal 12, 2310–2317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yuan GF, Chen XE, and Li D (2014) Conjugated linolenic acids and their bioactivities: a review. Food Funct 5, 1360–1368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kinami T, Horii N, Narayan B, Arato S, Hosokawa M, Miyashita K, Negishi H, Ikuina J, Noda R, and Shirasawa S (2007) Occurrence of Conjugated Linolenic Acids in Purified Soybean Oil. Journal of the American Oil Chemists’ Society 84, 23–29 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rodriguez-Duarte J, Dapueto R, Galliussi G, Turell L, Kamaid A, Khoo NKH, Schopfer FJ, Freeman BA, Escande C, Batthyány C, Ferrer-Sueta G, and López GV (2018) Electrophilic nitroalkene-tocopherol derivatives: synthesis, physicochemical characterization and evaluation of anti-inflammatory signaling responses. Scientific Reports 8 (1), 12784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are contained within the manuscript. Chromatographic and mass spectrometry raw data will be shared upon request to Sonia R. Salvatore (srs107@pitt.edu) or Francisco J. Schopfer (fjs2@pitt.edu).